Introduction

Domestic terrorist attacks in places like Las Vegas or San Bernardino have demonstrated the impact of highly skilled first responders on victim survival.Reference Smith, Walters and Reibling1–Reference Melmer, Carlin and Castater2 Both natural and man-made disasters have the potential for becoming incidents that produce more human casualties than health care systems can effectively handle. Through the competent application of field triage and treatment of mass casualty victims, emergency medical services (EMS) personnel prevent hospital systems from becoming overwhelmed, which in turn maximizes lives and limbs saved.

In the prehospital setting, the emergency responder’s triage performance is based upon timely assessment of injury severity and the ability to recognize the most severely injured patients who should be prioritized for transport to the most well-resourced facilities, like a trauma center. Traditionally, errors in field triage performance have been studied through the lens of patient outcomes (morbidity and mortality), patient characteristics (physical characteristics, nature of pathologies), or technical aspects of the patient encounter (skills of the emergency responder, procedures performed, drugs administered, etc.).

The most common approach to studying errors in field triage performance has involved retrospective analyses of whether responders either underestimate or overestimate the severity of the patient’s condition.Reference Bazyar, Farrokhi and Salari3–Reference Kilner6 Over-triage refers to assigning patients to a higher priority category than their conditions warrant, while under-triage occurs when a patient’s conditions are underestimated, resulting in lower priority designations. Both types of field triage errors have significant downstream consequences, including inappropriate resource allocation, delayed treatment of the most seriously injured, and consequently, increased morbidity and mortality.Reference Bazyar, Farrokhi and Salari3–Reference Kilner6 Under-triage errors are particularly dangerous since they result in critically injured patients not receiving timely interventions, such as advanced airway management, hemorrhage control, or rapid transport to a trauma center. In one study of a Dutch trauma registry, more than 20% of patients with severe injuries were not properly transported to level 1 trauma centers.Reference Voskens, van Rein and van der Sluijs5 Over-triage may seem harmless in comparison; however, these errors can strain emergency response systems, especially during mass casualty incidents (MCIs). Over-triaged patients occupy scarce resources such as critical care resources, advanced life support (ALS) units, or hospital trauma teams that would be better allocated to patients with more severe injuries.Reference Newgard, Staudenmayer and Hsia4 A study by Newgard et al. showed that over triage errors resulted in 34% of low-risk patients being transported to major trauma centers, costing the health systems up to $136.7 million in resources annually. Adhering more closely to field triage guidelines that minimize the over-triage of low-risk injured patients would not only save lives but would also save health system costs.Reference Newgard, Staudenmayer and Hsia4

While useful, triage errors cannot be objectively studied through analysis of patient outcomes alone. Nor can they be studied strictly through analysis of patient characteristics. Instead, a more comprehensive approach is needed to investigate the errors associated with the performance of emergency responders in the setting of a mass casualty incident.

Kurt Lewin’s Field Theory provided a theoretical foundation for understanding how human behavior, and therefore human error, results from an individual’s interaction with their environment. Research from the discipline of Human Performance has evolved from Lewin’s Field Theory Model to create more complex yet practical models for understanding errors resulting from human performance. One such model, the Task Demands, Work Environment, Individual Capabilities, and Human Nature, or TWIN Model of Error Precursors (also called the Work Environment, Individual, Task Related, Human Nature [WITH] Model), provided a useful lens for investigating the errors associated with human performance.7–Reference Mullen8 The TWIN model has been adapted by numerous professions and industries such as medicine, surgery, the military, civil aviation, and various fields of engineering (industrial, electronic, etc.).7–11 To date, however, the literature on emergency service professionals (ESPs) is void of a more comprehensive model, like the TWIN model, to explain errors made in the performance of their work.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the types of field triage errors made by experienced EMS professionals and less experienced emergency medicine (EM) trainees. By presenting a mass casualty incident scenario through a virtual reality simulation, errors could be studied within a controlled experimental environment, which presented common victims with the same injuries to a sample of emergency responders with diverse training backgrounds and experiences.

Methods

Population of Interest and Sampling

This was a retrospective investigation designed to analyze performance data of a sample of 99 individual emergency responders as they triaged and treated the scene of a mass casualty incident (MCI). All participants had been recruited to implement SALT Triage on a new, more challenging 14-patient MCI scenario compared to previous evaluations.Reference Kman, Way and Panchal12–Reference Way, Panchal and Price13 Data for this project were extracted from a data registry that contains all the performance data of emergency responders who participated in encounters with the First VResponderTM simulator between 2022 and 2024. These data were transferred from the VR system and stored in a secured data registry, which was established to serve as an active laboratory for research on triage and treatment of mass casualty incidents. To date, the registry holds triage and treatment performance data obtained from over 500 participants who represent individuals who serve as emergency responders or those responsible for working with or training them.Reference Way, Panchal and Price13 These include EMS clinicians (EMTs and paramedics), medical professionals and trainees (EM physicians, residents, and fellows), who volunteered to participate in research on their MCIVR simulation encounters generated during training sessions held at their place of employment or education. More thorough demographic information about the population of emergency responders in the data registry is available elsewhere, but will be summarized briefly here.Reference Way, Panchal and Price13 The proportion of EMS professionals to medical participants in the data registry is estimated to be 6 to 1 (i.e., 83.3% EMS professionals and 16.7% medical professionals and trainees). Most (~75%) EMS clinicians in the repository had completed some form of triage training before their VR encounter, while only ~35% of medical trainees had been previously trained. Only ~17.5% of participants from both groups said that they own a virtual reality system.Reference Way, Panchal and Price13 A small percentage (~14%) of EMS professionals and (~2%) of medical professionals and trainees have participated in some form of disaster drill. All subjects in the repository had received brief, just-in-time training (JITT) prior to their encounter with First VResponder™.Reference Kman, Price and Berezina-Blackburn14–Reference Kman, McGrath and Panchal16

First VResponderTM Simulation

The VR simulation platform used for this study has been described in detail elsewhere but will be summarized here.Reference Kman, Price and Berezina-Blackburn14 First VResponder™ (Tactical Triage Technologies LLC, Powell, OH) is a standardized VR platform that provides the user with a high-fidelity, fully immersive experience in a simulated environment. The VR simulation program was designed with Unity Pro, a software platform for developing video games using 3-dimensional (3-D) graphics.Reference Way, Panchal and Price13, Reference Kman, Price and Berezina-Blackburn14, Reference Kman, McGrath and Panchal16 The program is interactive, fully immersive, and automated. It runs on a commercially available laptop gaming computer with a Meta Quest 2 VR headset (Reality Labs, Meta Platforms, Menlo Park, CA). The simulation can be programmed to deliver encounters with varying degrees of difficulty by increasing: the number of victims, the severity of victim injuries, and the ratio of higher to lower risk victims. Furthermore, the platform can be programmed to be more challenging through methods that intentionally degrade the sensory input humans rely on to interpret their environment. In other words, the system can be programmed to increase the level of environmental stressors in the scenario by reducing visibility with virtual smoke or debris and reducing auditability by raising the volume of background noise such as sirens and virtual patient vocalizations.

Emergency responders are placed in a head-mounted display (HMD) and provided with hand-held controllers to navigate the scene and to grab tools for interacting with the virtual environment.Reference Kman, Price and Berezina-Blackburn14 The system provided a robust environment for exploring common types of field triage errors, potential explanations for their underlying causes, and the implications those errors might have on patient outcomes. By understanding the factors that contribute to these errors, we can begin to develop strategies to improve triage accuracy, which will ultimately lead to improved patient outcomes at reduced costs to the health system.

All performance data currently in the repository has been generated from a scenario involving a subway station that has experienced a bomb blast. (see Figure 1) Most of the performance data in the repository was gathered with a standard introductory scenario that presents 11 patients who suffered life-threatening injuries (e.g., acute arterial bleeding, penetrating trauma, tension pneumothorax, amputations, burns) or injuries that are non-life-threatening (e.g., superficial lacerations, hysteria, confusion, ruptured eardrum) injuries, (see Appendix B for a description of each patient). The environmental settings for the original introductory scenario can be described as a low level of stressors involving relatively good visibility (moderate lighting, halfway between bright and dark, with some debris and smoke in the air), accompanied by relatively good audibility (low levels of background noise).

Figure 1. Virtual reality image of a patient being treated in a subway that has experienced a bomb blast.

For this study, we sampled the recorded performances of a subset of 99 participants from the registry, all of whom had been recruited to implement SALT Triage on a new, more challenging 14-patient MCI scenario. The more challenging encounters were conducted between October 2023 and February 2024. Difficulty of the VR encounter was created through the addition of more critically injured patients, such as those requiring treatment of life-threatening bleeding injuries and those whose presenting conditions were not easily categorized into a triage classification tag. Examples include unconscious patients with no visible trauma, handicapped patients, or patients whose presenting conditions were not related to the mass casualty incident (like medical asthma) (see Appendix B for a description of all patients and the required life-saving interventions). The environmental intensity of the scene was further heightened through amplification of the background noise, including sirens and patient vocalizations. Responder visibility was reduced through dimmed lighting and increased levels of debris and smoke. This data set was used to assess whether a slightly more challenging MCI scenario (as compared to scenarios used previously) would increase the number of errors made, and whether it would impact fundamental triage metrics including time to hemorrhage control, triage accuracy, and triage efficiency (Appendix A). This study was approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board (Columbus, OH, USA IRB Protocol # 2020B0128).

Study Procedure

SALT Triage training took the form of a 15-minute just-in-time training (JITT) didactic session that explained how the protocol worked and how it was different from other triage protocols.Reference Kman17 The training was delivered to participants just prior to their individual encounter with the First VResponderTM system (Figure 1). Participants then completed a four-patient practice tutorial using the system, before encountering a VR scenario involving a subway station explosion resulting in 14 virtual patients with various states of injury. During their encounter, each participant’s performance data was recorded and saved.Reference Way, Panchal and Price13, Reference Kman, Price and Berezina-Blackburn14 After completion of the encounter, subjects were debriefed on their performance with an experienced EMS educator, who used a system-generated report of participant performance to provide feedback. Participants took an average of 45 minutes to complete all aspects of the session.

Performance Metrics

The First VResponderTM simulation system recorded emergency responders’ performances in a detailed time-stamped data log. From this log, metrics were extracted to evaluate performance, including triage efficiency and accuracy. Key efficiency metrics, as defined as critical measures by others, included time to triage scene, hemorrhage control for all life-threatening bleeding, and hemorrhage control time per patientReference Way, Panchal and Price13 (Appendix A). Performance metrics from each encounter were stripped of all identifiers and demographic information (except date of encounter) prior to being uploaded into the data registry.

We developed our own model of error precursors for analyzing the performance of emergency responders during their triage and treatment of a mass casualty incident by adapting various features of models from other professions. The result, the Triage Responder Intervention and Performance Error Model (TRIP EM) (Figure 1), was used by the authors to catalogue performance errors made by participants during their simulated MCI encounter.11, Reference Kman, Price and Berezina-Blackburn14, Reference McGaghie18

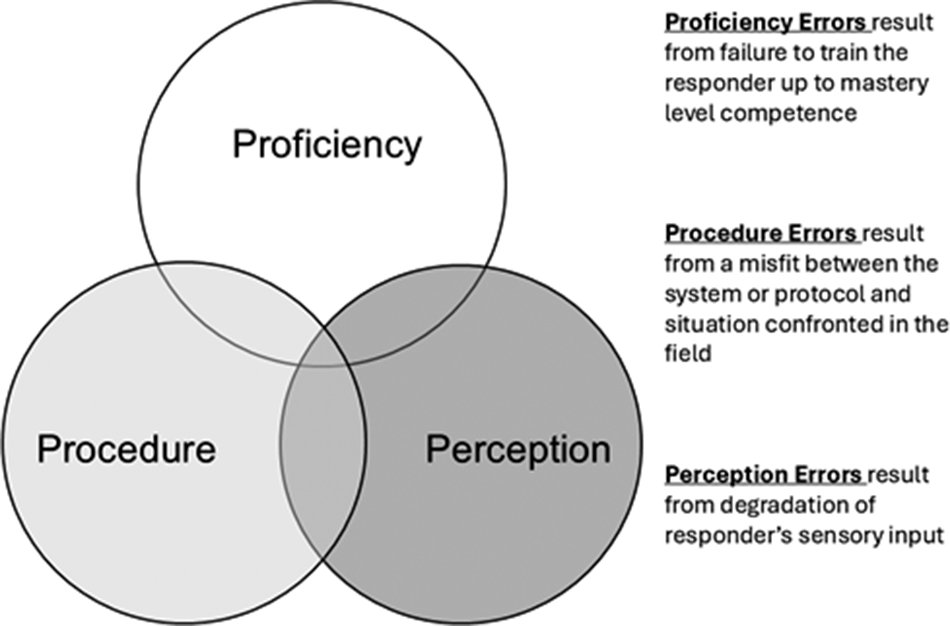

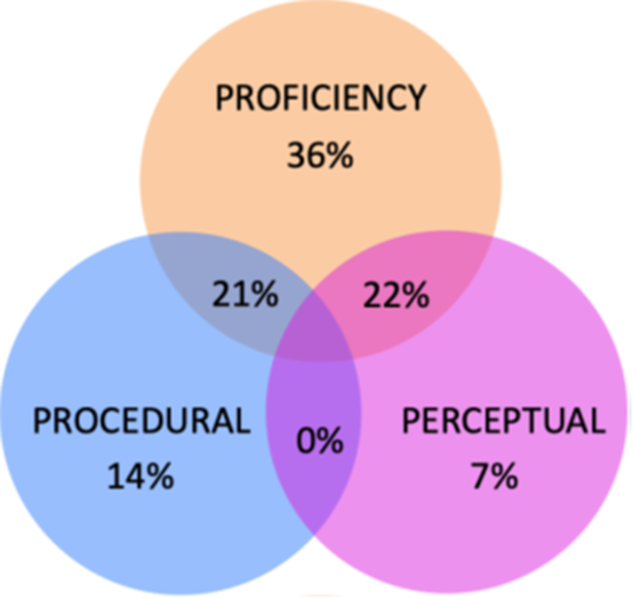

Consequently, errors observed in this study were categorized by their hypothesized source: proficiency, procedure, or perception (Figure 2). Proficiency errors were believed to originate from inadequate or incomplete training, which failed to help responders attain a mastery level of competence.Reference McGaghie18 Procedure errors are those that occurred due to a misfit between the situation confronted by the responder and the protocol or algorithm that guides what they must do to comply with performance norms.11 Finally, perception errors were those attributable to degradation of the responder’s sensory input, causing them to miss information needed to comply with performance norms.11, Reference Kman, Price and Berezina-Blackburn14 All three sources of error can overlap to varying degrees. For instance, a responder may be proficient under pristine conditions but lack proficiency when put under duress that disrupts their perception. Our model further corresponds to the widely used human performance model of skills (perception), rules (procedure), and knowledge (proficiency).Reference Rasmussen19

Figure 2. The Triage Responder Intervention and Performance Error Model (TRIP EM) used in our VR environment of a mass casualty incident.

Additionally, triage errors were catalogued using traditional classifications (over-triage, under-triage, and critical triage errors) adapted from a previous study.Reference Lee, McLeod and Van Aarsen20 Specifically, over-triage errors occurred when patients were placed into a higher priority triage category than required. Under-triage errors occurred when patients were placed into a lower priority triage category than required. Critical triage errors occurred when errors were likely to lead to patient morbidity or mortality (e.g., placed erroneously into dead or expectant category).Reference Lee, McLeod and Van Aarsen20

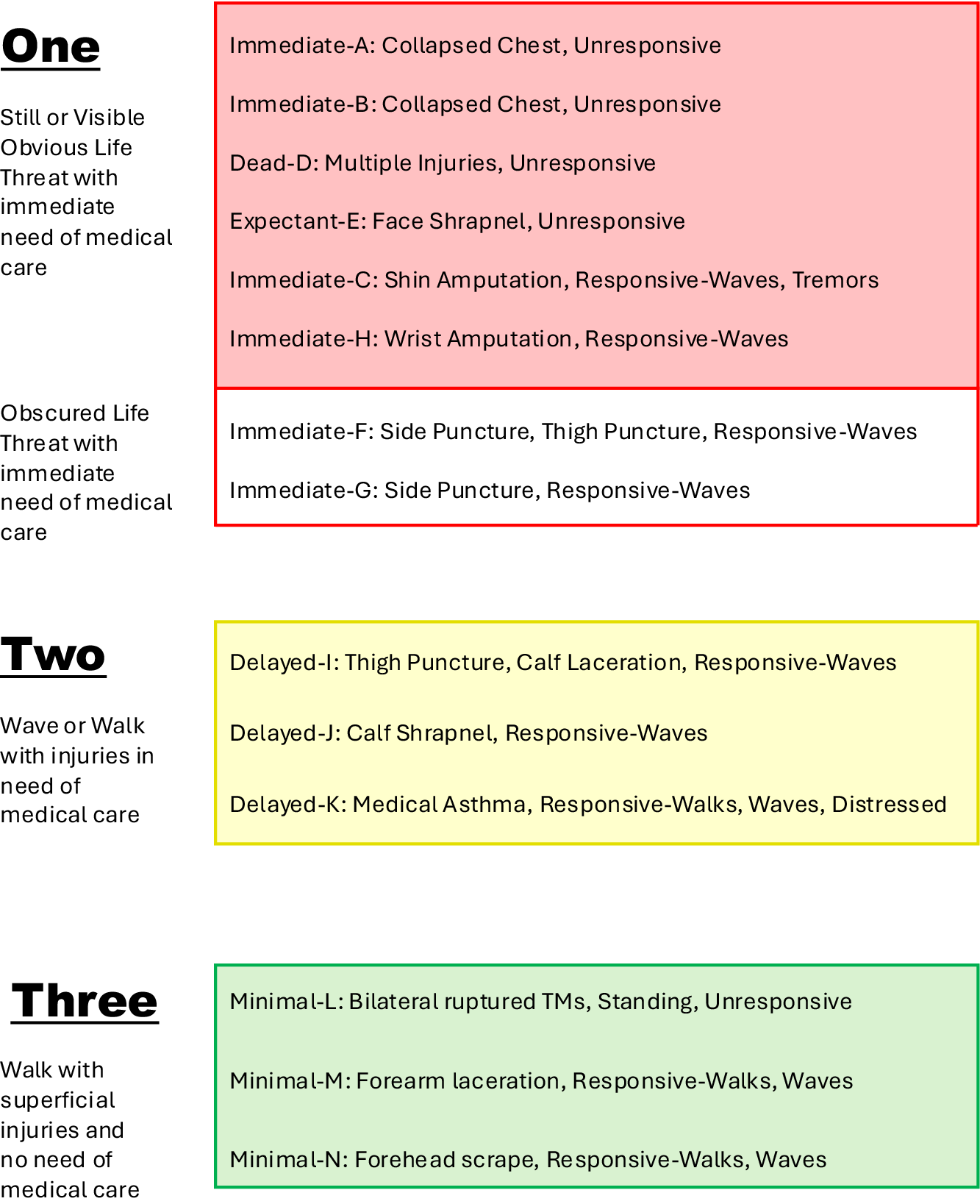

When effectively adhered to, the SALT protocol strives to minimize loss of life or limb. Overall triage performance was evaluated using a measure of SALT triage protocol compliance or execution, derived through a panel of emergency medicine faculty with disaster medicine or EMS experience (NEK, ARP, JM). Using the SALT algorithm as a guide, the panel sorted the fourteen patients in this scenario into three “priority” or sequence groups. For perfect performance, responders should first have assessed and triaged all of the patients in category 1 (patients who were still or had an obvious life-threat), then all of the patients in category 2 (patients who could follow commands, but could not walk), and finally the patients in category 3 (patients who could follow commands and could walk) (Appendix B and Figure 3). For every instance a responder failed to triage all of the patients in the first category before triaging patients in the second or third category, an error was counted. The metric only counts errors if patient members from a lower priority group were treated before a higher priority group. A score of zero is a perfect score with no patients treated out of order. We believe this metric, herein titled “SALT Adherence Performance,” serves as an accurate indicator of first responders’ efficiency during their performance encounter.

Figure 3. Sequence categories for scoring the SALT Adherence Performance metric. Group 1 includes unresponsive patients OR those with an obvious life-threatening injury; Group 2 includes patients who can respond to the “wave” command but cannot walk; Group 3 includes patients who are ambulatory. Responders can see patients in any order within a group as long as they see all patients in Group 1 before seeing any patients in Group 2 or Group 3. They must then see all patients in Group 2 and finally all patients in Group 3.

Data Analysis

Data for this study was obtained from the registry by filtering, parsing, and extracting time-stamped, individual performance logs into a de-identified database formatted for analysis. All triage efficiency measures were originally extracted in milliseconds and converted to seconds for analysis. Descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range, were calculated for all the triage efficiency measures. Percentages were also calculated for the triage performance metrics. Median boxplots and simple planned comparisons were used to contrast differences in participant performance across the 14 virtual patients in the mass casualty incident simulation. Since triage experience was unavailable specifically for the subjects of this study, triage experience was estimated from another data set outside the registry.

Results

Of the 99 emergency responder participants sampled for this study, 92% (91 of 99) were EMS clinicians and 8% (8 of 99) were emergency medicine residents. Most subjects (84%; 83 of 99) were from agencies located in suburban settings, while 16% (16 of 99) were from rural settings. All but the emergency medicine residents were from EMS agencies located in the State of Ohio. Performance data sampled from the data registry has been stripped of identifiers and demographic information; however, characteristics about this sample can be assumed to resemble the demographic profile of the subjects in the data registry outlined in Way et al. (2024) and detailed earlier in the methods section.Reference Way, Panchal and Price13

Triage Tagging Errors by Patient Difficulty

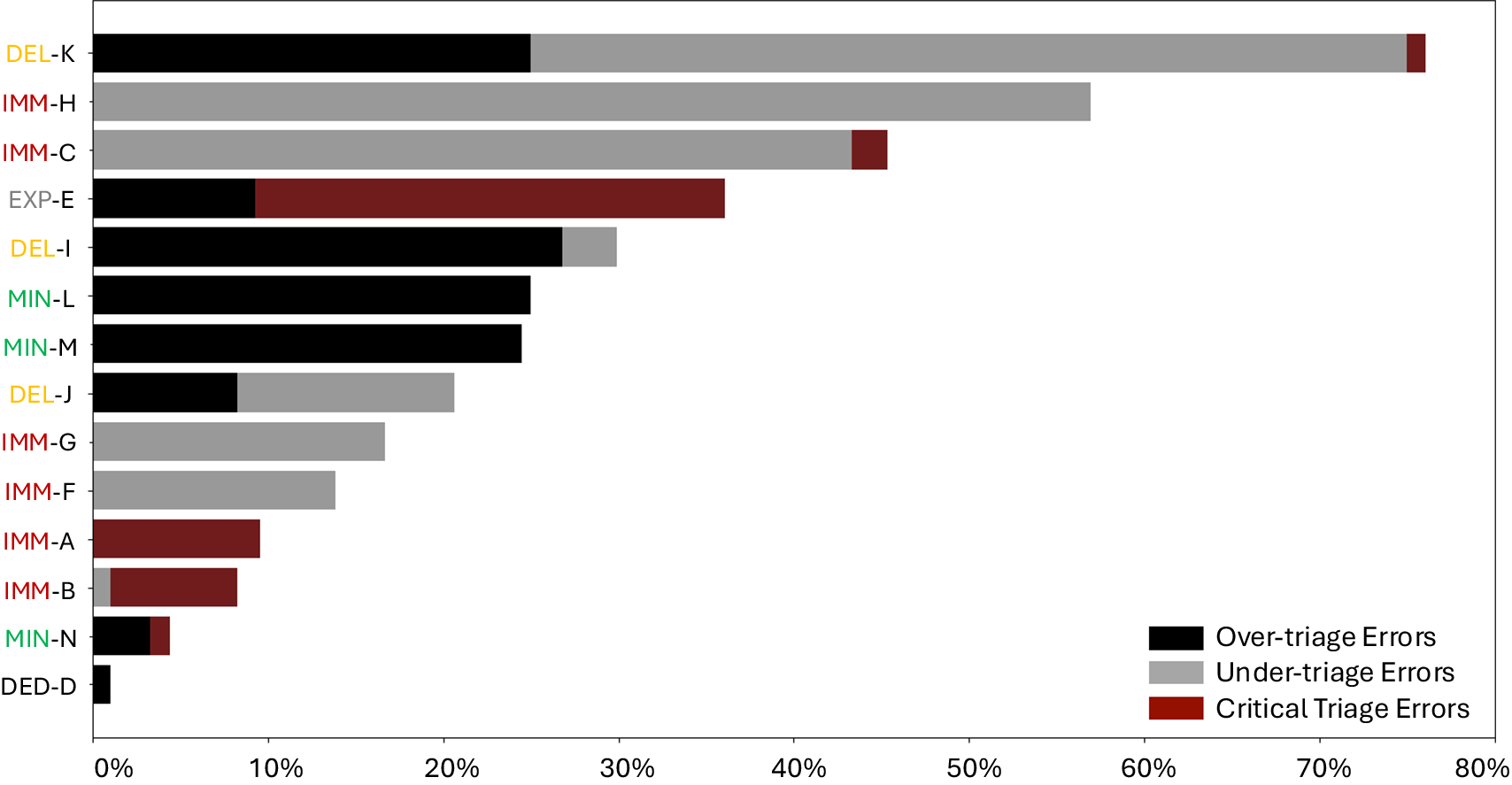

Average triage tag accuracy for each patient ranged from 22% to 97% (M = 70%, SD = 20%). Responders were most accurate (had the lowest percentage of triage errors) when patients had no signs of life, superficial wounds, or presented with unambiguous injuries that suggested the need for immediate life-saving care. Patient Dead-D was a deceased male with injuries inconsistent with life. Responders had little difficulty recognizing Patient Dead-D as deceased, and 99% (98 of 99) applied the correct black tag (Figure 4, Appendix B). Most responders (95%; 94 of 99) also correctly tagged Patient Minimal-N, who suffered a minor forehead scrape, and if asked, says “I’m OK.” More than 90% (89 of 99) of responders also correctly tagged the 2 collapsed chest (tension pneumothorax) victims, Immediate-A and Immediate-B, with an immediate tag; while roughly 85% (84 of 99) applied the same tag to patients who had puncture wounds of the abdomen, Immediate-F and Immediate-G.

Figure 4. Percentage of tagging errors for each of 14 patients in a virtual reality simulation of a mass casualty incident: over, under, or critical triage errorsReference Rasmussen19 (see Appendix A for definitions). Triage tagging categories indicated include minimal (MIN), delayed (DEL), immediate (IMM), expectant (EXP), and dead (DED).

Despite good performance on easier patients, there were also challenging patients that resulted in triage errors. Patients who presented with conditions that did not fit neatly into dichotomous “categories” according to the SALT protocol assessment: (Follows commands [Yes or No]; Respiratory distress [Yes or No]; Uncontrolled arterial bleeding [Yes or No]; Peripheral pulses [Yes or No]) were all under-triaged, suggesting that their conditions were more serious than represented by their tags (Figure 4, Appendix B).

The most challenging patient to triage was Delayed-K, with 75% (74 of 99) of responders erroneously tagging this patient. Delayed-K presented with wheezing and respiratory insufficiency but a normal respiratory rate (Figure 4, Appendix B).

Another virtual patient, Expectant-E, suffered embedded shrapnel just above the right eye socket and had no pulse but also presented with chest rise and slight movements of the hands. He was unlikely to survive, however, making the correct tag an expectant one. About 26% (26 of 99) responders tagged this patient with a dead tag.

First VResponder TM VR system mimics reality through the use of dynamic virtual patients. Consequently, once participants properly placed a tourniquet to stabilize Patient Delayed-I, who suffered major arterial hemorrhage of an extremity, he should have been tagged delayed, rather than immediate. Over a quarter of participants (26 of 99) over-triaged this patient once his bleeding was controlled after treatment (Figure 4, Appendix B).

Responders must be cognizant of other patient parameters when applying a triage tag after major arterial hemorrhage of an extremity is controlled. Two victims of limb amputation (Immediate-C [shin] and Immediate-H [wrist]) had already lost significant amounts of blood before the start of the scenario. Both victims displayed symptoms related to stage 3 hemorrhagic shock, elevated heart and respiratory rates. Consequently, both patients needed an immediate tag but were frequently tagged with delayed.

Some responders over-triaged Minimal-M, a patient who presented with a slowly bleeding forearm laceration, by tagging her delayed or immediate, instead of minimal.

Finally, patient presentations that were not neatly specified by the SALT triage protocol might be considered ambiguous patients. These could be patients, such as Delayed-K, who suffered from a pre-existing medical condition of asthma that was exacerbated by the mass casualty incident and were unable to be treated by the responder. Minimal-L, a newly hearing-impaired male who suffered tympanic membrane rupture, also fell into this ambiguous patient category since there was no available field treatment. Thirty percent (29 of 99) of participants who interpreted Minimal-L’s response as cognitive impairment or post-traumatic stress disorder, over-triaged this patient due to his inability to follow commands.

SALT Triage Adherence

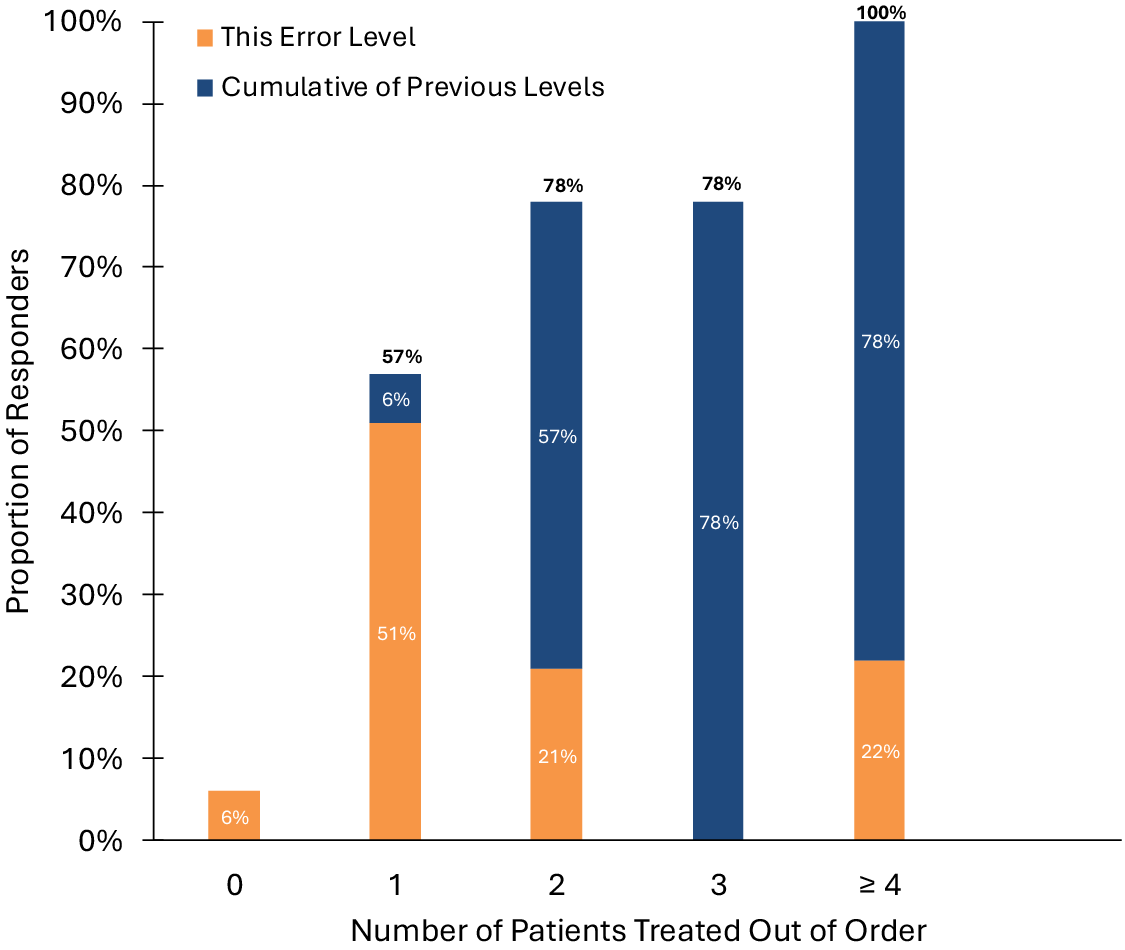

We used the SALT Adherence Performance metric to assess participants’ proficiency in triaging and treating the 14-patient scenario. A first responder might be considered to demonstrate proficiency errors when they deviated from the SALT prescribed sequence for assessing patient categories. Most participants (78%; 77 of 99) were able to complete the triage and treatment with only 2 or 3 deviations from the prescribed sequence for evaluating patients (Figure 5). Perfect adherence to the prescribed patient assessment order was accomplished by only 6% (6 of 99), while a single patient was treated out of order by another 57% (56 of 99).

Figure 5. The SALT Adherence Performance metric: Adherence to prescribed sequence for assessing patients according to SALT Triage protocol, represented by the number of patients treated out of order. Orange indicates the percentage of patients treated out of order for each level. Blue indicates the total percentage of patients treated out of order for previous levels. The percentage outside the bar indicates the total percentage of patients treated out of order up to and including that level (i.e., 57% of responders made 0 or 1 errors, with 6% making 0 errors and 51% making 1 error).

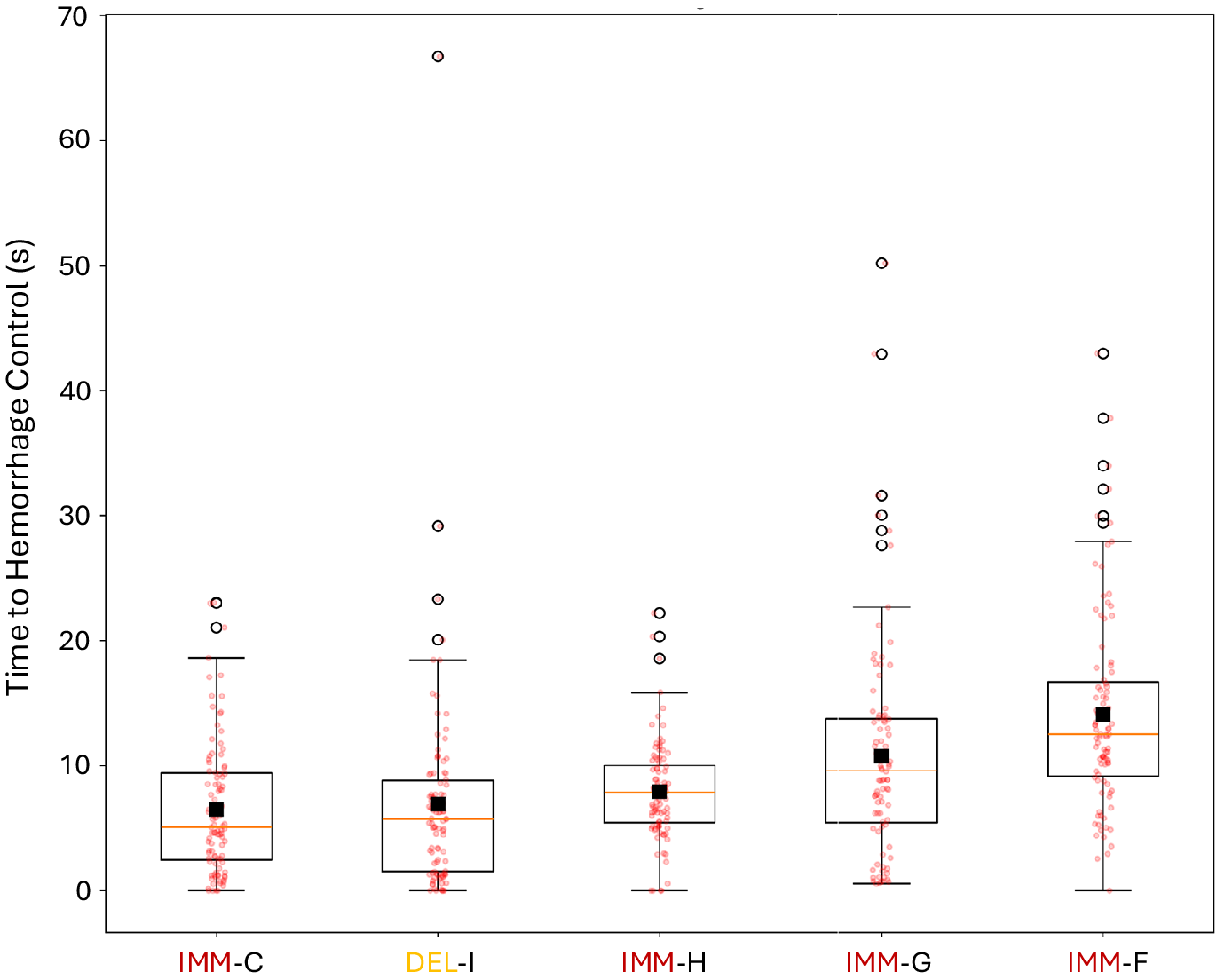

Hemorrhage Control

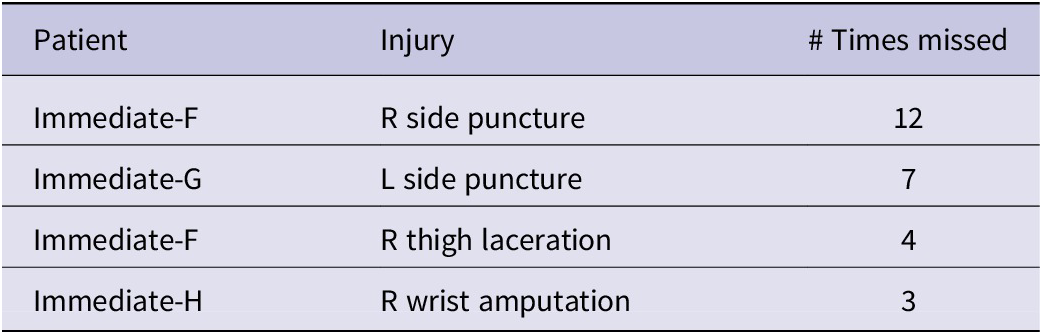

Eighty participants out of 99 (81%) completed hemorrhage control for all life-threatening bleeding injuries (represented by 5 of the 14 patients) across the entire scene in an average time of 6.1 minutes (SD = 2.4 minutes). Bleeding injuries that were most frequently missed are listed in Table 1. Times to control hemorrhage in patients with life-threatening bleeding injuries are shown in Figure 6.

Table 1. Bleeding injuries most frequently missed

Figure 6. Hemorrhage control times per virtual patient. Triage tagging categories indicated include delayed (DEL) and immediate (IMM).

A repeated measures ANOVA (Greenhouse-Geisser corrected) revealed significant differences in hemorrhage control times for different virtual patients, F (3.5,323.2) = 23.5, P < 0.001, n 2 = .19. Post hoc tests suggested that participants took significantly longer to control bleeding in Immediate-F compared to all other patients, P < 0.05. Immediate-G required the second longest hemorrhage control time which was significantly longer compared to Immediate-C (t (98) = 4.8, P < 0.001), Immediate-H (t(98) = 3.1, P < 0.05) and Delayed-I (t (98) = 3.4, P < 0.05).

Immediate-F had two injuries that required hemorrhage control. While 12 responders missed treating his side puncture wound, 4 responders missed treating both the side puncture wound and the right thigh laceration. Seven participants missed treating the side puncture wounds suffered by both Immediate-G and Immediate-F. Three responders never assessed nor treated Immediate-H, who suffered from a wrist amputation.

Errors in treating bleeding injuries would be considered perceptual if the wound was obscured so that the responder could not see it (wounds hidden by extremities or low visibility due to darkness). These errors would be classified as proficiency if the responder had not been trained to perform an effective bleeding assessment of each patient encountered. Finally, the errors in treating bleeding injuries could be considered procedural if responders expected the simulation to involve only one injury per patient or the simulation failed to cue them effectively about such conditions as extreme blood loss or signs of hemorrhagic shock. Each arterial bleeding injury missed had the potential to result in morbidity or mortality, leading to a concern that participants needed more guidance and training in how to search and detect bleeding injuries at the scene of a mass casualty.

Interaction Time per Patient

Besides triage error, average interaction times per patient also contributed to our understanding of which patients were most challenging to our participants. Average interaction times ranged from 10 seconds to 29 seconds (M = 20.3, SD = 7.1) (Figure 7). Participants spent significantly less time (t (98) = 5.75, P < 0.05) assessing patient Dead-D, who was relatively easy to assess visually, and Minimal-N, who suffered only a mild contusion and told participants that she was “OK.” Participants spent the longest amount of time interacting with Delayed-J, who presented with an impaled foreign body (calf shrapnel) without hemorrhage. Since the wound was not bleeding, emergency responders may have had difficulty in determining what treatment to apply. Participants also spent longer amounts of time (23 seconds or more) with Expectant-E, Immediate-A, and Delayed-K. Expectant-E and Delayed-K may have required time because responders were not equipped with treatments for either the embedded shrapnel above the eye or the medical asthma. Immediate-A was a female tension-pneumothorax case who was perhaps more challenging to diagnose through observing chest rise.

Figure 7. Average participant interaction times per virtual patient. Triage tagging categories indicated include minimal (MIN), delayed (DEL), immediate (IMM), expectant (EXP), and dead (DED).

Error Classifications by Source

We applied our error classification model to the 14 patients in our scenario and classified each patient and error into this model for each measure (Appendix C). Figure 8 shows the percentages for each error source, including perceptual, procedure, and proficiency, and their overlapping categories. Results show that 79% of errors can be traced to issues of proficiency.

Figure 8. Proportions of error sources for perceptual, procedural, and proficiency sources.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate performance errors of emergency responders while triaging a mass casualty incident VR simulation. Results showed a predominance of proficiency errors, followed by procedure and perception errors. Detailed explanations for why these errors may have occurred and recommendations for their remedies are provided in this discussion.

Proficiency Errors

Despite efforts to ensure that study participants had a cursory command of the SALT triage protocol prior to their encounter, responder performance varied widely. Some of this variability was attributable to experience and training, which has been observed in other studies.Reference Deeb, Phelos and Peitzman21 Recognizing respiratory distress or insufficiency, for example, was a common source of error and is related to the experience and training of the individual participant. Clinical judgment, a product of training and experience, is required for estimating injury severity. The over-triage of Minimal-M (a patient with a minor forearm laceration) was most likely due to the over-estimation of injury severity and the protocol’s poor guidance for discriminating between delayed and minimal triage categories.

When examining the 6 virtual patients with injuries related to the respiratory system, we discovered that they had been mis-triaged at least 30% of the time. Errors in triage categorization in these cases were most likely due to errors related to the responder’s ability to assess the patient’s respiratory or airway status. This finding has been witnessed in other studies and suggests that detection of physical findings related to the diagnosis of respiratory injuries, such as asymmetric chest rise, paradoxical rise and fall, tachypnea, and agonal breathing, are more challenging than injuries related to hemorrhage; and that experience and education play a role in the emergency responder’s performance in properly triaging patients with respiratory injuries.Reference Lovett, Buchwald and Sturmann22

The level of experience and training of first responders also played a significant role in triage accuracy and adherence to an expected standard. Inadequate training or lack of familiarity with triage protocols can contribute to both over-triage and under-triage errors. One study of EMS provider decision making consistently stated that the choice of whether or not to enter a patient into the trauma system was driven primarily by the field provider’s gut feeling, rather than by explicit triage criteria.Reference Newgard, Staudenmayer and Hsia4 This is especially concerning when EMS providers are inexperienced and lack the clinical gestalt that comes from mastery of triage and treatment skills. Regarding the potential for lack of adherence to be serious enough to be considered a threat to patient safety, we might be concerned about the 22% of participants who committed four or more errors in the prescribed sequence. These were individuals who most likely did not learn the proper sequence prescribed by SALT Triage, which is to first assess the still, unresponsive patients, or those with obvious life-threatening injuries, followed by the patients who could follow commands but could not walk, and finally, the ambulatory patients who walked to the safe or cold zone. These types of proficiency errors need to be diagnosed and corrected as quickly as possible.

Another source of triage error was the responder’s tendency to select a tag based on the patient’s initial presentation rather than on their condition after treatment. Emergency responders are typically taught that patients are dynamic and their triage status can change when properly treated. Consequently, the triage category of patients who suffer bleeding injuries to extremities can change from immediate to delayed when properly treated with a tourniquet. In the event, however, if a patient displayed symptoms consistent with hemorrhagic shock from significant blood loss, they would remain triaged as an immediate due to the presence of hemorrhagic shock.

The triage errors related to patients with bleeding injuries in this study were most likely made by individuals with little field experience and only cursory triage training. Participants who missed detection of bleeding injuries or the visual cues associated with hemorrhagic shock (blood loss, tremors, elevated heart and respiratory rates) were most likely never taught the principles of “stop the bleed” hemorrhage recognition or never had direct experience with patients suffering from bleeding injuries during a mass casualty response.

The triage and treatment errors related to hemorrhage control also bring to light the need for effective training of new and inexperienced emergency responders. Regular, effective scenario-based training that closely simulates the conditions of real-life emergencies can contribute to improving the accuracy of triage decisions.Reference Rodgers23 Training should focus on both cognitive and technical skills and include debriefings to discuss errors and improvements. Furthermore, implementing feedback mechanisms where first responders can learn from their triage decisions, either through post-incident analysis or real-time feedback, can enhance their skills and reduce future errors. Simulation-based mastery learning methods paired with immersive simulations of mass casualty incidents could contribute to improving first responder competence in the complex skills of triage and treatment of mass casualty incidents.Reference Sawyer, White and Zaveri24–Reference Kman, Price and Berezina-Blackburn26

Perception Errors

Factors associated with the general chaos of a mass casualty incident also contributed to triage errors. When reflecting upon the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attack (India) and the shooting in San Bernardino (U.S.A.), medical responders reported that sensory overload from noise and smell complicated their effective systematic implementation of emergency medical treatment and led to deficiencies in triage adherence in the prehospital setting.Reference Smith, Walters and Reibling1, Reference Roy, Kapil and Subbarao27, Reference Reay, Rankin and Smith-MacDonald28 Training first responders up to mastery level performance can increase their ability to perform in adverse conditions in which their sensory input is compromised. Stress management training, including stress exposure training with biofeedback, may further prepare responders in those conditions.Reference de Visser, Dorfman and Chartrand29

The 14-patient scenario was developed for this study with the intention of making it a more challenging and stressful environment when compared to other scenarios that have been developed for mass casualty response training. Performance in this study was generally lower compared to a previous evaluation with a similar but less difficult scenario.Reference Kman, Way and Panchal12 The more challenging encounter in this study led responders to make errors like overlooking the second bleeding injury on the Immediate-F patient or overlooking the chest rise on the patient Expectant-E. Prior studies have attempted to examine first responder effectiveness under stress, but were unsuccessful at recreating a stressful environment.Reference Cone, Serra and Kurland30 This study demonstrated that to induce perception-based medical triage errors required a completely immersive virtual environment that resembled the chaotic environment of a real MCI.

The availability of medical resources, such as personnel, equipment, and transportation, can also influence triage decisions. In resource-scarce environments, responders may be forced to make difficult choices that increase the likelihood of errors. In this scenario, the triage kit was equipped with unlimited supplies; however, this is a setting in the program that can be altered to increase the challenge of the encounter. Individuals who have participated in encounters with First VResponder TM often request additional tools, like chest seals, that they would have wanted during their encounter.

Ineffective communication between responders, or between responders and patients, can result in incomplete or inaccurate patient information, leading to improper triage decisions. In Lewiston, Maine, an initial call to 911 by a hearing-intact survivor relayed that he was with an injured person who appeared to be deaf. The after-action report of that event concluded that deaf victims of mass casualties were an area of opportunity for reducing medical errors.Reference Wathen31 Subjects in this study were challenged by Minimal-L, the patient who had ruptured tympanic membranes from the blast. The inability to communicate with this patient frustrated our emergency responders, who typically spent extra time with him and often over-triaged him.

Procedure Errors

The final contributor to triage error may be the triage system itself. Triage protocols are, by their nature, designed to be comprehensive yet simple to execute. Consequently, responders to MCIs may encounter patients that do not neatly fit into the triage categories established by the protocol. Protocols that are too complex or not well-suited to the specific incident will lead to errors. Gaps in ongoing training and scenario-based simulations can also leave first responders ill-prepared for real-life emergencies, increasing the risk of triage errors. During the simulation for this study, patients with multiple injuries such as Delayed-I were over-triaged, and those presenting with difficult-to-interpret symptoms such as Minimal-L who suffered ruptured tympanic membranes were both over- and under-triaged by our participants. These types of complex patients did not fit neatly into the SALT triage protocol, which typically led to delays or missed triage categories. Another example was patient Delayed-K, who represented an individual with agonal breathing from medical asthma exacerbated by the smoke and debris of the bomb blast. Participants under-triaged him if they failed to account for his respiratory insufficiency and lack of access to a rescue inhaler; and over-triaged him if they overestimated his wheezing as respiratory distress.

Suggested strategies to mitigate systems-related under-triage error involve the use of decision-support tools, such as triage algorithms, mobile apps, or Large Language Models (LLMs).Reference Preiksaitis, Ashenburg and Bunney32 LLMs have already been trained to make triage decisionsReference Molineaux, Weber and Floyd33–Reference McVay, De Visser and Pippin36 with varying degrees of success,Reference Kaboudi, Firouzbakht and Eftekhar37–Reference Arslan, Nuhoglu and Satici39 and recent work has further demonstrated that the type of simulator data from medical professionals collected in this study can enhance LLM performance above and beyond merely training the LLMs on the triage protocols.Reference Mani, Kman and Way40 Continuously updating triage protocols through analysis of triage errors could also contribute to helping first responders make more accurate assessments. Prehospital provider education focused on protocol adherence while emphasizing the downstream effects of under-triage errors can also help to improve field performance.

Protocols that require responders to perform difficult tasks under duress also lead to triage errors. Responders to the San Bernardino shooting had trained many times on the use of the START triage protocol for adults and JumpSTART pediatric algorithm,41, Reference Kohn, de Visser and Weltman42 yet no responder to this MCI implemented these systems.Reference Smith, Walters and Reibling1, Reference Gebhart and Pence43, Reference Stefani, de Melo and Zardeto44 Post-incident analysis revealed that responders universally relied on clinical judgment and did not use physiological numbers or number ranges for triage decisions.Reference Smith, Walters and Reibling1 This has implications for protocol choice, given that several triage algorithms require responders to perform tasks like counting respirations or checking capillary refill, which are challenging assessments to perform under duress or in dark or high-stress environments. Furthermore, MCI assessments may be improved by using protocols that use yes-or-no criteria to support decisions.

Limitations

The findings in this study must be considered in the context of emergency responder performance in both the mass casualty and virtual reality settings. Disaster medicine in general, and mass casualty response in particular, is different from most medical literature, which evaluates the interaction of the practitioner with each patient in isolation. Mass casualty encounters must be evaluated through the lens of the practitioner with the entire scene. The time and treatment applied to each patient in the scenario are not independent of all the other patients. Therefore, the metrics included in this study were an attempt to capture the execution of those dependencies to identify the potential sources of error, which have implications for improved training methods.Reference Keebler, Lazzara and Misasi45

While VR mimics much of what an individual would experience in real life, the use of controllers in VR for navigating space and implementing medical implements was not a perfect proxy for physical, hands-on experience. Consequently, estimated error rates could be higher in a real-life setting. Additionally, the “time-to-task-completion” required for treating bleeding injuries in this virtual reality environment does not directly translate to the time it would take to complete actual treatments of bleeding injuries. In this VR environment, “the time to task completion” more accurately reflects the time to assess the patient, decide on which treatment to apply, and then demonstrate the application of the chosen treatment by moving the treatment tool to the site of the injury using the hand controllers. Training and evaluation of the actual application of treatments on patients is typically performed using task trainers or manikins.

Additionally, this study was limited to a single VR scenario (subway bombing) and a single emergency responder performing independently. This subway scenario consisted of virtual patients who were relatively homogeneous and void of individuals from pediatric populations. These conditions might limit the generalizability of the study findings to other types of mass casualty incidents and situations that include two or more responders. Further research should assess the performance of emergency responders in other types of MCIs, while staffed in teams, and with more variability among patient demographics. Human performance with protocol refinement and decision support tools also remains an opportunity.

Conclusion

Field triage is a vital yet challenging aspect of emergency medical response. While triage errors are an inherent risk due to the complex and unpredictable nature of emergency scenes, understanding the factors that contribute to these errors can help develop strategies to mitigate them. This VR-based study identified key contributors to field triage errors, including errors related to proficiency, perception, or procedure. Based on this diagnosis, we suggest protocol enhancements, training improvements, the use of decision support tools, and stress management techniques to enhance responder performance and patient outcomes in MCIs.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2025.10288.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Kellen Maicher, Alan Price, Vita Berezina-Blackburn, and Jeremy Patterson for their contributions to the development and continued improvement of First VResponder TM. [First VResponder TM, Tactical Triage Technologies LLC, 4301 Home Rd., Powell, OH 43065, USA]

Author contribution

Study concept and design (EDV, JM, NEK, JNH, JMc), acquisition of the data (NEK, DPW, DD, JM), analysis and interpretation of the data (EDV, KC, JA, BP, NEK, JMc, JNH, DPW), drafting of the manuscript (EDV, JM, NEK, DPW, ARP), critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (EDV, JM, NEK, DPW, ARP), statistical expertise (EDV, DPW, KC, BP), and acquisition of funding (NEK, DD, JMc). All authors contributed to final review and revision of the final version and approved it for submission.

Funding statement

This project was funded under grant number R18HS025915 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The authors are solely responsible for this document’s contents, findings, and conclusions, which do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. Readers should not interpret any statement in this report as an official position of AHRQ or of HHS. None of the authors has any affiliation or financial involvement that conflicts with the material presented in this report.

Competing interests

EDV, JM, DPW, KC, JA, BP, ARP, and JM report no other conflicts of interest. DD, JNH, and NEK are founding members of Tactical Triage Technologies LLC, which was created in 2025 to commercialize this Virtual Reality Technology.