Introduction

The endurance of informal economic activities has been a global challenge and a longstanding inquiry in sociolegal studies. Informal economy encompasses a range of practices not fully recognized or regulated by formal institutions, such as informal finance (Madestam Reference Madestam2014; Adrian and Ashcraft Reference Adrian and Ashcraft2012), informal labor markets (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Collins, Hunter, Pickford, Barratt and Fearnall-Williams2023; Ulyssea Reference Ulyssea2010), and informal entrepreneurship (Salvi et al. Reference Salvi, Belz and Bacq2023), etc. These activities usually receive certain recognitions from society but are marked by uncertain judicial protections or enforcement (Maloney Reference Maloney2004; Sassen Reference Sassen1994). The informality of economic activities is sometimes used interchangeably with terms such as “extra-legality” (Bernstein Reference Bernstein1992; Soto Reference Soto2003; Qiao Reference Qiao2017), “quasi-legality (Tsai Reference Tsai2002),” and “shadow of law (Mnookin and Kornhauser Reference Mnookin and Kornhauser1979),” which emphasize the ambiguous zone between full compliance and non compliance with the law.

How do informal economic activities manage to endure, despite the fact that they do not fully obey the law? Existing literature, though scattered around different fields and not necessarily using the same terminology, has identified at least three mechanisms: marginalization of law, circumvention of law, and legal collusion. Marginalization of law refers to the mechanism by which informal economic activities within close-knit communities operate based on mutual trust without formal recognition from the law (Winn Reference Winn1994). Examples include the diamond industry that designs contracts in legally unenforceable ways (Bernstein Reference Bernstein1992), the “small property rights” in China, without legal titles, but prevail in the housing market (Qiao Reference Qiao2017), etc. Circumvention of law refers to the circumstance where informal economic activities exploit loopholes within regulatory frameworks to circumvent state scrutiny (Fleischer Reference Fleischer2010). Examples include loan sharks in Russia (Hendley Reference Hendley2004), unlicensed sex workers in England (Klambauer Reference Klambauer2019), etc. Legal collusion refers to the tacit acquiescence or agreement between law enforcers and informal economic activities that would otherwise be sanctioned. Examples include the Chinese giant internet companies writing extralegal contracts to issue international bonds (Qiao Reference Qiao2023), unlicensed migrant workers in Beijing who collude with law enforcement officers out of mutual interests (He Reference He2005), etc. All the above informal economic activities tend to rely on informal ways, either marginalizing, circumventing, or colluding with the law, to receive limited recognition from other social institutions to endure.

This study uses the case of Chinese unlicensed moneylending, a typical industry of informal finance, to explain a counterintuitive mechanism: informal finance can endure through formal litigation. This mechanism is unique in two important ways. First, instead of passively sidestepping or circumventing the law, the informal economy in this case actively interacts with and seeks recognition from the gatekeeper of justice, the courts. Second, while the informal economy typically receives only limited recognition from either a confined community or imperfect law enforcers, the legality conferred by courts is state-backed.

Moneylending is an area where its semilegal practices, notably predatory lending and debt collection, have been heavily documented by studies in many countries (Fleming Reference Fleming2018; He Reference He2011; Hendley Reference Hendley2004). In China, “unlicensed moneylenders (zhiye fangdairen)” refers to those who frequently engage in moneylending business but are unlicensed to issue loans. The industry resides in a grey area of the entry regulation of the Chinese financial market (Li and Shen Reference Li and Shen2020). Previous works have documented how informal financial activities in China, including unlicensed moneylenders, tend to evade judicial enforcement and “marginalize legal institutions” (Winn Reference Winn1994; Upham Reference Upham1994). Instead, they heavily rely on community-imposed sanctions such as reputation and physical harassment to endure.

However, anecdotal evidence in recent years has suggested an opposite trend, that an increasing number of unlicensed moneylenders heavily use litigation to enforce their semilegal debts. In one Beijing grassroots court, a man filed 486 private lending lawsuits in a single year, in 2016. Other than him, the court discovered twenty plaintiffs filing more than fifty lending lawsuits each, with one company filing 1,395 alone (Beijing Evening News 2017). The Associate Chief Justice of Henan reported that 14,968 out of 598,567 private lending cases were suspiciously brought by private moneylenders in 2020 across the province (China News 2021). A grassroots court in Zhejiang reported that among the 11,087 private lending cases it decided between 2015 and 2017, 5,094 were filed by 445 plaintiffs who each initiated more than five cases, including a top-filer that brought 101 cases alone (People’s Court Daily Reference Court Daily2018). One judge in Zhejiang once indicated that nearly 70% of plaintiffs in the private lending cases she decided were private moneylenders (People’s Court Daily Reference Court Daily2018).

Many of these cases involved predatory lending practices. Some moneylenders, including certain fintech platforms, incorporate service or consultation fees to artificially reduce the nominal interest rates. They also file lawsuits in different courts or operate under the guise of other legal activities, making it difficult for judges to detect their true nature of unlicensed lending (China Comment Reference Comment2014). By contrast, most debtors, upon being serviced, do not attend trials due to fears or fail to seek legal help due to a lack of resources. This leaves debtors unable to challenge even predatory lending. Judges frequently make default judgments in favor of moneylenders (People’s Court Daily Reference Court Daily2018).

Assuming these moneylenders are rational market players, the cost of obtaining such judicial enforceability should be lower than fully complying with the law. Yet, despite documentation on the high cost of obtaining a financial license in China (Yuan and Xu Reference Yuan and Xu2020; Xu Reference Xu2023), few empirical studies have examined what actually happens in courts. Why are moneylenders assured to bring lawsuits to enforce semilegal debts? Why don’t debtors attend trials, and how does this impact case outcomes? How do judges—knowingly or unknowingly—allow litigation to become a tool to unjustly legitimize informal finance? These questions are not only concerned with factual uncertainties but also boil down to the long-standing sociolegal inquiries into the sustainability of informal economic activities.

We use mixed methods to study how unlicensed moneylenders sustain themselves in courts. We conducted quantitative analysis on 66,843 judicial decisions on private lending lawsuits in Shanghai, case studies on seven specific top-filers, and in-depth interviews with judges and lawyers. We found that sophisticated moneylenders, inactive debtors, and embedded courts collectively helped sustain unlicensed moneylending before 2020. Specifically, moneylenders can leverage superior legal resources to ensure judicial enforceability even if their debt agreements are semilegal. Debtors facing moneylenders, by contrast, suffer from serious hurdles in accessing justice, especially lacking professional legal help that could potentially change case outcomes. Judges chose to tolerate the unlicensed moneylending industry, despite concerns about debtor protection, because they have stronger incentives to support the pre 2020 political environment that valued the expansion of private financing, notably through Fintech.

To be sure, we do not claim that the semilegal, unlicensed moneylending industry was sustained solely through courts. Extralegal enforcement mechanisms, such as coercion, certainly exist and have been well documented (Tsai Reference Tsai2002). However, the assumption that most such disputes are resolved informally, without resorting to the courts, risks overlooking a significant portion of the picture. As our later case studies show, court-backed decisions provided powerful support for unlicensed moneylenders, enabling scalable contract enforcement and heightening pressure on debtors. Thus, we do not attempt to offer a comprehensive account of the Chinese private lending industry, but instead highlight the often-overlooked role of formal litigation as a possible venue for informal finance to endure.

Beyond China, the use of litigation as an unjust means to bypass regulation has also been a trend in other jurisdictions. In the USA, for example, state courts are facing an “access to justice crisis” in high-volume debt collection lawsuits (Wilf-Townsend Reference Wilf-Townsend2022; Engstrom and Engstrom Reference Engstrom and Freeman Engstrom2024). The crisis is featured by a cluster of institutional debt collectors that develop routinized, assembly-line tactics to exploit unrepresented and inactive defendants. Their claims are often based on “bad paper” with insufficient documentation to sustain the debt owners’ claim to the amount demanded (Halpern Reference Halpern2014). Judges mostly remain passive and lack the capacity to scrutinize illegal or semilegal claims (Wilf-Townsend Reference Wilf-Townsend2022; Khwaja Reference Khwaja2022). The case study on China may offer insights into the unjust use of litigation in broader social contexts, on why it happens, and what we can do about it.

The paper proceeds as follows. Part one reviews the literature on the endurance of the informal economy. Part two explains the informal moneylending industry in China. Part three introduces data and methods. Part four presents empirical results. Part five discusses the results and concludes.

The endurance of the informal economy

The informal economy characterizes the grey market between what is in full compliance with the formal law or regulation and what is not, but still gains certain recognition from other social institutions. Previous studies have generally revealed three mechanisms of its endurance: (1) marginalization of law, (2) circumvention of law, and (3) legal collusion.

First, marginalization of law refers to the mechanism by which informal economic activities, typically within close-knit communities, operate based on mutual trust, relational contracts, or reputation without formal recognition from the law (Macchiavello Reference Macchiavello2022; Winn Reference Winn1994; Macneil Reference Macneil1985). This mechanism is particularly prevalent in close-knit communities or specialized industries, where informal norms provide more adaptive ways of managing disputes and transactions. For instance, in the diamond industry, formal law is systematically rejected in favor of an internal set of rules to handle disputes among industry members (Bernstein Reference Bernstein1992). Reputation plays a crucial role in keeping this mechanism working. People with bad reputations are usually excluded from future transactions, and the cost of losing one’s reputation often exceeds the benefits of breaching community norms (Ambrus et al. Reference Ambrus, Mobius and Szeidl2014).

Second, circumvention of law refers to the situations where informal economic activities exploit loopholes within regulatory frameworks to circumvent state scrutiny (Fleischer Reference Fleischer2010; Pollman Reference Pollman2019). Scholars have used economic models to reveal the inherent “incompleteness” of law that leads to the inevitable legal loopholes by which people are incentivized to take advantage of (Katz and Sandroni Reference Katz and Sandroni2023; Pistor and Xu Reference Pistor and Xu2002). For instance, loan sharks in Russia hesitate to use courts because they don’t want to open up transactions to state scrutiny (Hendley Reference Hendley2004). Unlicensed sex workers in England attempt to avoid state authorities for fear of legal repercussions (Klambauer Reference Klambauer2019). Predatory consumer contracts in the USA thrive by enhancing the non transparency of their unfair clauses through black-box algorithms (Becher and Benoliel Reference Becher and Benoliel2023; Bar-Gill et al. Reference Bar-Gill, Sunstein and Talgam-Cohen2023). Chinese commercial banks use wealth-management-products issuance to avoid regulatory constraints and contribute to the rapid growth of shadow banking (Shah et al. Reference Shah, Li and Fu2020).

Third, legal collusion refers to the tacit acquiescence or agreement between law enforcers and the informal economic activities that would otherwise be sanctioned (Liu Reference Liu2024; He 2005; Reference He2004). Such a “collusion” often takes place when an equilibrium of mutual benefits is reached between different stakeholders. For instance, migrant workers in Beijing used to engage in a semilegal “license-renting” business, which was “sustained institutionally” by the collusion between local businesses, law enforcement officers, and the local authorities (He Reference He2005). Chinese giant internet companies write unenforceable contracts to issue international bonds (Qiao Reference Qiao2023) but receive protection from “the networks of government actors, market intermediaries, and corporations” instead of judicial enforcement (Qiao Reference Qiao2023). In the implementation of China’s one-child policy, families who violated the policy collude with village cadres to be protected from the higher government’s punishment (Liu Reference Liu2024).

For all these three mechanisms, the informal economic activities involved only operate in a limited, temporarily accepted manner, lacking the more general state back-up. The litigation-endured mechanism we present here is unique, as the informal economic activities actively seek and receive state-backed recognition from courts. Unlike marginalization of law, the informal economic activities move from the reliance on internal norms to seeking enforcement from state institutions, the courts. Unlike circumvention of law, the informal economic activities no longer passively count on the inaction of law enforcers but actively seek state-backed recognition. Unlike legal collusion, the informal economic activities obtain a more robust and widely accepted recognition from a favorable judicial decision than mere tacit acquiescence. This type of informal economic activity deserves deeper theoretical and empirical investigation due to the counterintuition of strategically using the formal legal system to cut corners of the law.

Additionally, in the context of China, studies on courts typically perceive the judiciary as a passive and weak branch that functions only secondarily in economic development to other state organs (Clarke 1996; Reference Clarke2003; Su and He Reference Su and He2010; Chen and Li Reference Chen and Li2023). The informal economy, however, is deemed a vital, if not the major driver, of Chinese market growth. A large body of literature on law and development has emphasized that alternative financing channels based on individual reputation and private relationships outweigh the role of formal legal institutions in economic development. (Qiao Reference Qiao2023; Hou Reference Hou2019; Chen Reference Chen2018; Coase and Wang Reference Coase and Wang2012; Allen et al. Reference Allen, Qian and Qian2005; Clarke Reference Clarke2003; Upham Reference Upham1994). Empirically testing this mechanism of “litigation-endured informal economy” bridges the two strands of literature where Chinese courts and the informal economy might overlap.

How, then, might informal economic activities endure through formal litigation? Existing literature offers valuable conceptual scaffolding to help unpack this question. Most notably, Marc Galanter’s seminal work on the “haves” and “have-nots” (Galanter Reference Galanter1974) introduced the foundational idea that disparities in party capabilities—legal resources, litigation experience, and social capital—can systematically shape litigation outcomes. Building on this “party capability theory,” subsequent studies have shown that repeat players with superior capacity tend to secure more favorable results (Eisenberg and Farber Reference Eisenberg and Farber2013; Dunworth and Rogers Reference Dunworth and Rogers1996). Parallel to this, the “judicial preference theory” suggests that court outcomes may also be shaped by judges’ institutional orientations or political and economic incentives (Songer et al. Reference Songer, Sheehan and Brodie Haire1999; Songer and Sheehan Reference Songer and Sheehan1992). In many contexts, it is the interaction between these two forces that structures litigation inequality. (Chen, Huang, and Lin Reference Chen, Huang and Lin2015). Following this strand of literature, we can hypothesize that litigation-endured informal economies are made possible either through the superior litigation capabilities of informal actors, judicial leniency toward them, or both.

In the context of China, conflicting evidence has been reported in support of the party capability theory and the judicial preference theory. On the one hand, it is found that institutional litigants win far more than individual litigants by a large margin in Shanghai courts (He and Su Reference He and Su2013). Likewise, wealthier, resource-oriented prisoners have higher chances of receiving sentence deductions than their counterparts who are normal prisoners (Lin and Shen Reference Lin and Shen2017). On the other hand, it is found that “married-out women,” a group of Chinese women married to husbands living in another rural village or city, could prevail over the institutional government-backed village collectives due to judicial sympathy towards their underprivileged status (Chan Reference Chan2019). Such empirical uncertainty strengthens the necessity to explore the dynamics in unlicensed moneylending lawsuits and how their informal nature is sustained.

In brief, this paper tends to reveal a group of underexplored informal economic activities that tailor their behaviors specifically for judicial protections and strategically litigate to gain state-backed recognition. This mechanism differs from those in existing literature because it achieves that goal through formal litigation, the cornerstone of our legal system. Existing theories suggest that the mechanism could be driven by the litigation capability inequality and/or the judicial preference that strengthens such inequalities, yet more empirical evidence is needed. Such theoretical tensions and empirical uncertainties trigger this study.

Unlicensed moneylending in China

“A murder must be paid with life; a debt must be paid with money (杀人偿命, 欠债还钱).” This has been an axiom since ancient China, where accessing capital from formal financial channels, such as banks, is never easy. State banks strongly favor state-owned enterprises, while individuals and private entrepreneurs usually seek out alternative channels, presumably within informal finance, to raise capital (Tsai Reference Tsai2002; Shen Reference Shen2016). Calculated by Kellee Tsai based on the China Statistical Yearbook, as of year-end 2007, only 1.3% of the loans extended by state banks went to private enterprises (Tsai Reference Tsai, Li and Hsu2009). In 2019, the market volume of private financing stood at ¥5 trillion, making it one of the largest shadow banking systems in the world (Lu Reference Lu2019). A vibrant segment of the Chinese informal finance sector is comprised of “private/unlicensed moneylenders,” who are not licensed to issue loans but lend money frequently to others. Different from occasional lending between friends or families, which is legal, or operating unlicensed banks, which is illegal, unlicensed moneylending that issues loans without taking deposits resides in a grey area and is considered informal finance.

In traditional Chinese society, unlicensed moneylenders operate within close-knit communities, but the advent of financial technologies in the 2010s brought significant changes to the industry. Enabled by peer-to-peer (P2P) lending platforms and digital microfinance tools, unlicensed lenders gained access to broader markets. Some are directly registered as “cash loan” companies without appropriate licenses. Some used P2P platforms—initially designed as mere information intermediaries—to disguise themselves as “available lenders” and issue small loans to random borrowers (Gao Reference Gao2019). Others operate under the guise of legitimate investment or guarantee companies but actually issue loans (Shen Reference Shen2016). In the early 2010s, this grey area was broadly tolerated by financial regulators. China adopted a “wait-and-see” attitude, embracing alternative financing channels, notably Fintech, as a potential vehicle for economic growth and financial inclusion (Xu et al. 2023). Digital micro-lenders and P2P lending expanded rapidly under minimal oversight. In 2016, China accounted for 99.2% of the total Asia Pacific internet finance market and an estimated 85% of the total global market. A total $243.28 billion was raised, with more than half targeting consumer lending for household finance (Garvey et al. Reference Garvey, Chen and Zhang2017, 20–23).

This light-touched regulatory leniency began to shift in late 2016, as concerns about predatory lending and systemic financial risk drew public and political attention. A series of high-profile scandals exposed exploitative practices in both online and offline unlicensed lending. In the widely reported “naked loan” case, many female college students using P2P platforms were coerced into providing explicit images and nude video recordings as loan collateral (Guo Reference Guo2016). Meanwhile, traditional underground lenders relying on face-to-face intimidation also persisted. One abusive model—known as “trap loans (taolu dai)”—gained notoriety for targeting vulnerable borrowers, such as the elderly. These loans were often marketed as low-interest, but in practice, they relied on inflated loan amounts, fabricated breaches of contract, and the deliberate destruction of repayment records. The goal was to create a false appearance of legitimate debt and to coerce repayment through legal threats or actual lawsuits (He Reference He2019).

These cases triggered widespread public outrage at unlicensed “loan sharks,” whether operating through digital platforms or traditional offline networks. Much of the anger stemmed from how these predatory practices were cloaked in the appearance of legal formality with formal contracts, signatures, and litigation filings. The backlash galvanized regulators into action. Scholars have described the state’s response as “campaign-style governance”: a sweeping, bureaucratically coordinated crackdown led by financial regulators across the country (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Tang and Guttman2019).

As the regulatory side moved tighter, the issue landed on judges’ desks: how to assess the validity of a lending contract issued by an unlicensed lender, and how to identify such a lender? As noted earlier, the informal economy differs from pure illegality as it is not explicitly banned by law, but could be interpreted in such an unfavorable way that leads to the lack of judicial protection. Doctrinally, the then-semilegal status of unlicensed moneylending stemmed from two legal ambiguities: (1) whether unlicensed moneylending constitutes the “business of a banking financial institution” that violates the financial market-entry regulation; and (2) if so, whether the financial market-entry regulation constitutes an “imperative provision of administrative regulation,” upon which the violation can lead to a contract being voided. If both answers are “yes,” the lender will not be eligible to receive judicial protections on any interests or fees agreed upon other than the principal itself. The ambiguities of both answers, however, create a grey area where unlicensed moneylenders reside.

First, Article 19 of the Chinese Banking Supervision Law prohibits the operation of “business of a banking financial institution” without a banking license. But it is ambiguous about what constitutes such a business. While an unlicensed entity taking deposits and issuing loans at the same time clearly violates the law and will bear criminal liability,Footnote 1 the legal consequence is fuzzy when it only issues loans without taking deposits.

The second issue is whether a potential violation of the Banking Supervision Law could result in the loan contract being voided. According to Article 153 of the Chinese Civil Code, a contract violating “law or the imperative provision of administrative regulation” shall be voided. But there was no clear criterion for whether lower-level administrative rules—including the normative documents issued by financial regulatory agencies—qualify. The legal consequence of a lending contract being voided is that the moneylender will only be entitled to get the principal back, without any other interests, fees, or penalties, even if contractually stipulated.

Given these ambiguities, courts acquired the discretion. For a long time, the attitude of the Chinese Supreme People’s Court (SPC) towards unlicensed moneylending was subtle and at times ambivalent. In an official media interview in 2015 introducing a new judicial interpretation on private lending, an SPC judge in charge remarked that “[i]f a business enterprise does not engage in production but instead becomes a professional lender…that is unacceptable … such contracts will be voided” (Du Reference Du2015). This restrictive view was later echoed in a widely circulated official publication authored by SPC judges that lower courts often rely on. There, it is again emphasized that businesses engaging in frequent lending should, under the Banking Supervision Law, be deemed to conduct “illegal financial activities” that harmed the public interest, and such contracts should be voided (Du and The SPC First Civil Division Reference Du2015, 221–22). Yet in a separate chapter of the same volume, the tone shifted. SPC judges this time urged judicial restraint, writing that “in the current absence of clear law or administrative regulations, courts should follow the principle that ‘what is not expressly prohibited by law is permissible,’” and advised that lower courts “should not necessarily invalidate lending contracts involving unlicensed moneylenders. (Du and The SPC First Civil Division Reference Du2015, 272–73)”

These contradictory signals are also reflected by case opinions. In a 2015 case where the debtor alleged that the lender was an unlicensed moneylender, the SPC found the evidence insufficient and noted that “even if the lender were unlicensed … the regulatory provisions on financial lending are not mandatory for determining civil contract validity.”Footnote 2 But in a 2017 case, the SPC took a firmer position, holding that Article 19 of the Banking Supervision Law was a mandatory provision related to public financial order and could serve as a basis for invalidating frequent, unauthorized lending.Footnote 3

In short, while the SPC expressed disapproval of “illegal financial activity,” it refrained from articulating clear criteria for when unlicensed moneylending crossed the threshold into such illegality. Sometimes this ambiguity also stemmed from procedural uncertainty on whether a judge should actively gather evidence or passively wait for debtors to raise the issue.Footnote 4 In practice, the courts might be more skeptical of business than individual plaintiffs, but without concrete standards, judges retained wide discretion. These substantive and procedural uncertainties incentivized unlicensed moneylenders to obscure the commercial nature of their operations, often framing themselves as occasional private lenders to secure enforcement.

It was not until November 2019 that the SPC, in a conference summary (jiumin jiyao), ultimately confirmed that “loans issued by unlicensed businesses or individuals who routinely engage in private lending for commercial purposes should be deemed void.”Footnote 5 While the “conference summary” does not have the formal status of law, it functions as authoritative guidance in practice, and local courts generally follow its interpretations closely. In August 2020, the SPC followed up with a more detailed and formal judicial interpretation, confirming that “loans issued by individuals or entities without proper lending qualifications, for profit, and offered to unspecified members of the public should be deemed invalid.Footnote 6 In China, such a “judicial interpretation (sifa jieshi)” is generally treated as binding law by courts.

In both rules, the SPC instructed courts to assess four key factors when determining whether to void a lending contract: whether the lender (1) is unlicensed, (2) frequently issues loans, (3) is profit-driven, and (4) targets unspecified groups. In practice, the frequency of lending has emerged as the most important criterion.Footnote 7 The SPC did not make a unified national standard but authorized provincial courts to develop their own standards based on local conditions to identify moneylenders. Studies have shown that starting from 2020, the courts, nationwide, began voiding debts that met these criteria (Liu Reference Liu2021; Mao Reference Mao2023).

Alongside semilegal licensing status, another major legal issue shaping the boundaries of enforceability in private lending is the application of usury law (Li and Cheng Reference Li and Cheng2020). Over the past decades, China’s usury law has undergone a series of revisions. From 1991 to 2015, the SPC permitted interest rates up to “four times the contemporary bank lending rate”—generally around 20–25% annually. In 2015, the SPC formalized a cap of 24% annually (or 2% monthly). A subsequent judicial interpretation in 2020, however, reduced the ceiling to four times the Loan Prime Rate (LPR), which at the time stood at approximately 15.4% annually. The 2020 amendment formed part of the broader regulatory tightening that accompanied the SPC’s clarification on licensing.

Importantly, violating usury laws does not automatically void an entire lending contract. Instead, courts typically invalidate the excessive portion of the interest agreement, reduce the enforceable interest rate to the legal cap, and then allow recovery of principal plus adjusted interest. This legal consequence stands in contrast to cases where contracts are entirely voided due to licensing violations. In such cases, while courts still enforce the principal repayment, the interest rate applied is typically much lower than the legally permissible cap, often set at the contemporary bank deposit/loan rate (around 3–6% annually). In short, licensing violations tend to trigger more severe legal consequences than usury violations. If a contract is voided due to a licensing infraction, the usury issue becomes practically less important.

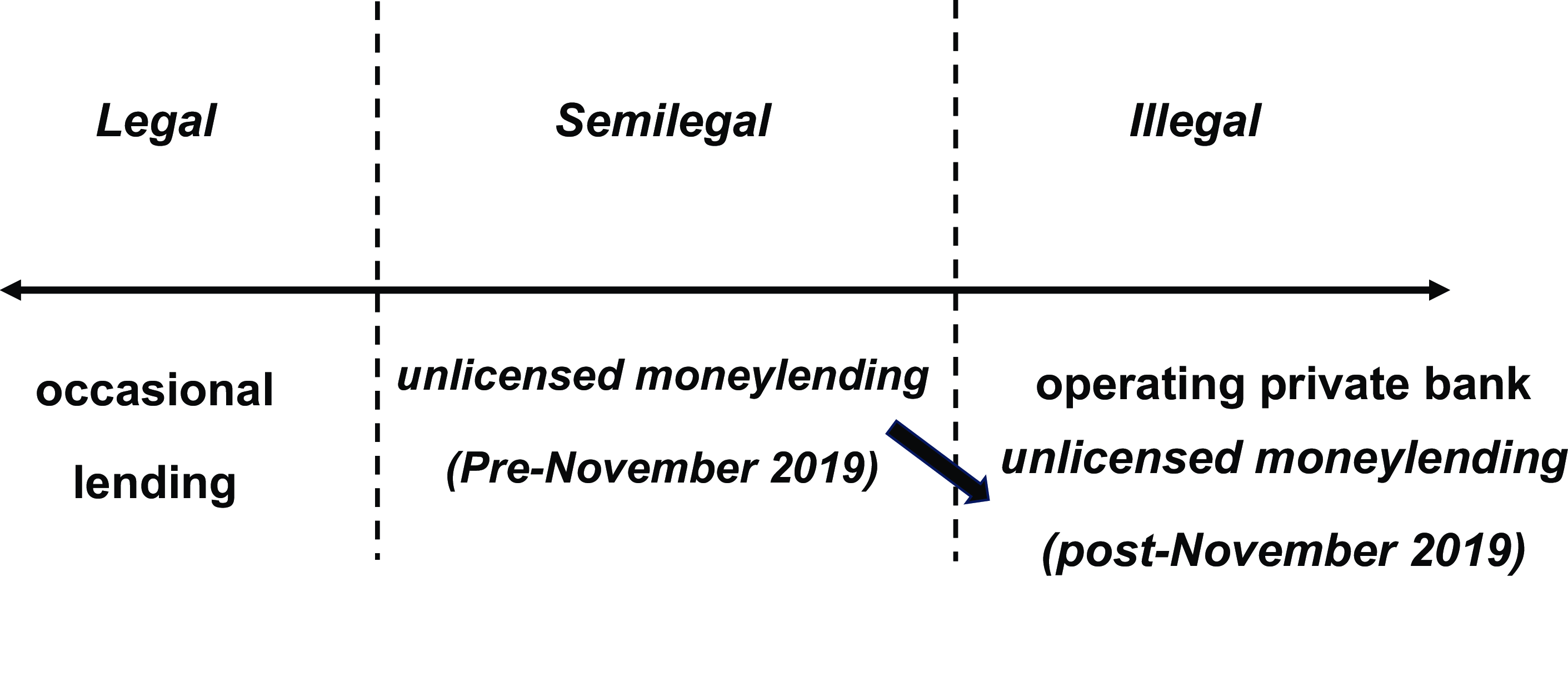

To summarize, Figure 1 depicts the legal status of unlicensed moneylenders in China. Before November 2019, this type of informal finance was semilegal due to the ambiguities in both financial market-entry regulation and contract law. After that, unlicensed moneylending was moved to the illegal zone.

Figure 1. The Legal Status of Unlicensed Moneylending in China

Data and methods

We combine quantitative and qualitative data to show how unlicensed moneylenders interacted with courts. We establish an original dataset compiling 66,843 first-trial judgments on private lending lawsuits in Shanghai from 2014 to 2019. The dataset is built with Fayi, a Chinese legal technology company, and the vendor of SPC’s judicial digitalization project.Footnote 8 In China, a “private lending dispute (minjian jiedai jiufen)” refers to the loan dispute between entities without a loan-issuing license. It differs from a “financial lending dispute (jinrong jiekuan jiufen),” in which the creditor is a licensed financial institution, such as a bank. Accordingly, all plaintiffs in “private lending lawsuits” are unlicensed lenders. They may be individuals or businesses and may appear either once or repeatedly.

China’s judicial system is structured into four levels of courts: the SPC, high people’s courts (provincial level), intermediate people’s courts (municipal level), and grassroots people’s courts (district level). Grassroots courts handle the vast majority of low-value civil disputes, including private lending cases. Appeals are heard by intermediate courts, whose decisions are usually final.

We only analyze judicial judgments (panjue) and exclude verdicts (caiding) because most verdicts are rulings on procedural matters, which do not necessarily reflect case outcomes.Footnote 9 For example, a defendant’s motion to dismiss, aimed at securing more preparation time, does not reflect the merits of the case. A judgment, by contrast, is where judges decide the validity and fulfillment of the debt. We focus on the first-trial judgments in regression analysis to ensure sample comparability that relies on a consistent criterion of measuring case outcomes. Second-trial judgments are included in qualitative case studies to depict the more nuanced facets of judicial decision making.

The dataset starts from 2014, as it was the year when the Chinese Online Judicial Disclosure law became effective.Footnote 10 The dataset ends in 2019 because, as we explained above, the semi-legality of unlicensed moneylending lasted until the end of 2019, after which it totally lost judicial protection and became illegal. We acknowledge that there is a recent backlash on judicial transparency in China, and that many sensitive decisions might be removed from the website (Liebman et al. Reference Liebman, Stern, Wu and Roberts2023). However, its impact on our study should be minimal, as most private lending lawsuits are not politically or socially sensitive.Footnote 11

Primarily due to data availability, the quantitative part focuses on Shanghai, but the patterns identified can largely reflect broader trends nationwide. China operates generally under a unitary legal system, meaning that judicial and regulatory frameworks are designed to be consistent nationwide, as opposed to a federal system where significant provincial variations exist. In the context of moneylending regulation and adjudication, there might be technical variations across provinces about interest rate calculations and liability distribution (for example, the allocation of responsibility between debtors and third-party guarantors). Yet these differences do not fundamentally alter the core principles of how courts adjudicate private lending disputes, such as licensing rules and interest rate caps, which are uniformly applied under the SPC’s guidelines. Acknowledging potential regional nuances, we believe the main findings are representative nationwide.

For each judicial judgment, we extract a number of variables reflecting litigation and contract information. Then we conduct paired t-tests and logistic regressions to explore the correlations between party capabilities and case outcomes, in moneylender lawsuits and occasional lending lawsuits, respectively. We establish the following logistic regression model:

where the dependent variable Win pqc is a dummy variable that equals one when the plaintiff (creditor) fully wins the case, and to zero otherwise. Basically, a judgment can have three types of outcomes: (1) completely support the plaintiff’s claims, (2) partially support the plaintiff’s claims, and (3) completely dismiss the plaintiff’s claims. As introduced, the creditor can get the principal back even if the contract is voided, which means a “partial win” sometimes means a total failure. Consistent with existing literature and industry norms, we code the win rate as a dummy variable that equals one if the creditor completely wins the case. We try alternative coding methods in robustness checks, and the main results remain robust (Table A5).

To our knowledge, Shanghai does not have publicly explicit rules, as some other provinces do, on how to identify unlicensed moneylenders. Based on our interviews with judges and lawyers, we learned that a key rationale for this less clear-cut approach is that a rigid classification could create loopholes to be exploited (JD-05-2023; LY-02-2023). Given this absence of formal guidelines in Shanghai, we rely on identification rules from close provinces as a normative reference to interpret potential moneylenders in the Shanghai dataset.Footnote 12 Specifically, if a plaintiff brings more than ten lawsuits (including) in any calendar year, we identify this creditor as an unlicensed moneylender. In this regard, analyzing Shanghai data actually presents an advantage—since there are no clear-cut local rules, moneylenders in Shanghai are less likely to strategically structure their operations to circumvent the guidelines, and the dataset is likely to be a more neutral representation of real unlicensed moneylending market. In robustness checks, we applied a threshold of “fifteen lawsuits” as an alternative criterion, and the main findings remain robust (Table A6).

We are interested in how party capabilities, measured by legal representation, litigation experience, and trial activeness, impact case outcomes. Creditor_Rep

p

is a dummy variable indicating whether the party is represented. To measure the quality of representation, we include continuous variables

![]() $Creditor\_fir{m_p}$

and

$Creditor\_fir{m_p}$

and

![]() $Debtor\_fir{m_p}$

to measure the number of times the representing law firm has appeared in courts before this lawsuit (included). Creditor_Exp

p

and Debtor_Exp

p

are continuous variables that indicate the party’s own litigation experience, that is, the number of times the party has appeared in courts before this lawsuit (included). For example, a party’s litigation experience equals five if it is the fifth time the party has brought/received a lawsuit. We calculate the natural logs of the four variables measuring litigation experience to avoid multilinearity. In robustness checks, we calculate litigation experience alternatively as a fixed count (the total number of appearance), and the results remain robust (Table A7).

$Debtor\_fir{m_p}$

to measure the number of times the representing law firm has appeared in courts before this lawsuit (included). Creditor_Exp

p

and Debtor_Exp

p

are continuous variables that indicate the party’s own litigation experience, that is, the number of times the party has appeared in courts before this lawsuit (included). For example, a party’s litigation experience equals five if it is the fifth time the party has brought/received a lawsuit. We calculate the natural logs of the four variables measuring litigation experience to avoid multilinearity. In robustness checks, we calculate litigation experience alternatively as a fixed count (the total number of appearance), and the results remain robust (Table A7).

![]() $Creditor\_typ{e_p}$

and

$Creditor\_typ{e_p}$

and

![]() $Debtor\_typ{e_p}$

are dummy variables indicating whether the creditor and the debtor are a business or an individual. We identify a party as a business if its name exceeds four Chinese characters or there is a term in its name that indicates its business nature (for example, “company” or gongsi in Chinese). After the preliminary data cleaning, we manually double-check to confirm all categorizations are correct.Footnote

13

$Debtor\_typ{e_p}$

are dummy variables indicating whether the creditor and the debtor are a business or an individual. We identify a party as a business if its name exceeds four Chinese characters or there is a term in its name that indicates its business nature (for example, “company” or gongsi in Chinese). After the preliminary data cleaning, we manually double-check to confirm all categorizations are correct.Footnote

13

We categorize debtor activeness (measured by Debtor_active p ) into three ordered levels: “low” for neither attending trial nor having representation, “medium” for attending trial without representation, and “high” for obtaining legal representation. S pqc is a set of control variables indicating contract information that might impact win rates, including: (1) the natural log of the court filing fee as a proxy of the case value (amount of controversy); (2) a dummy variable “interest agreement” that indicates whether the party has an agreement on interest rate; (3) a dummy variable “guarantee agreement” that indicates whether the parties have an agreement on guarantee or collateral measures; and (4) a dummy variable “multi-judge” that indicates whether the case is decided by a bench trial with multiple judges (Yu and Sun Reference Yu and Sun2022). α c and γ q are respectively court-specific and quarter-specific fixed effects. Court fixed effects account for jurisdictional differences, capturing adjudication practice variations between grassroots courts in Shanghai. Quarter fixed effects control for time-varying factors that could influence judicial decisions, such as economic fluctuations affecting case filings over time. A complete description of all variables can be found in Table A1.

Qualitative data first includes in-depth interviews with seven judges and six lawyers we conducted between February 2023 to September 2023. Among them, four judges work in grassroots courts in Shanghai, and the other three work at the appellate level. All judges have extensive experience deciding private lending lawsuits. All six lawyers have multiple-year experience representing private moneylenders or debtors. Each interview is semi-structured and lasts between 45 to 60 minutes. More information about the interviewees is listed in Table A2.

Additionally, we conducted case studies on seven “top-filers” (five businesses and two individuals) in our dataset. We closely read the 1,542 court decisions filed by these top-filers, summarized their business models, and gathered their business operation information online. We also provided the fact patterns to our interviewees and inquired about their opinions. This approach helps us to better understand the business and litigation process through both objective and subjective materials.

Illuminated by the party capability theory and judicial preference theory, the mechanism that unlicensed moneylenders endure through litigation is likely to be jointly fostered by moneylenders, debtors, and courts. Accordingly, we establish three specific hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1:

-

(a) Compared with occasional lenders, unlicensed moneylenders possess stronger litigation capabilities and achieve better case outcomes.

-

(b) The win rate of unlicensed moneylenders is positively correlated with their litigation capabilities, such as legal representation and litigation experience. This correlation may be unique as opposed to that of occasional lenders.

Hypothesis 2:

-

(a) Compared to debtors facing occasional lenders, debtors facing unlicensed moneylenders suffer from greater hurdles in accessing justice.

-

(b) The win rate of unlicensed moneylenders is positively correlated with the lack of legal help and trial passivity of the debtors opposing them. This correlation may be unique as opposed to that of debtors facing occasional lenders.

Hypothesis 3: Judges chose to tolerate the informal moneylending industry, despite concerns about debtor protection, because they had stronger incentives to support the pre 2020 policy environment that valued the expansion of private financing, particularly through Fintech.

The first two hypotheses are tested by both quantitative and qualitative data. We first present descriptive statistics and t-tests to show the capability gap between moneylenders, occasional lenders, and their respective opposing debtors. Then, we use panel-data logistic regression to explore the correlation between litigation capabilities and case outcomes. We acknowledge that the statistical inference here only suggests correlations rather than causations, so we further present qualitative data from the interviews and case studies to show the mechanisms of these correlations. The third hypothesis is primarily tested by qualitative data. Through case studies on the top-filers and interviews, we try to understand whether judges are aware of the “tricks” of unlicensed moneylenders and what factors impacted their judicial decision making. The combination of three hypotheses provides an explanation of the counterintuitive phenomenon that informal finance can endure through formal litigation.

Results

Party capabilities and case outcomes

Quantitative evidence

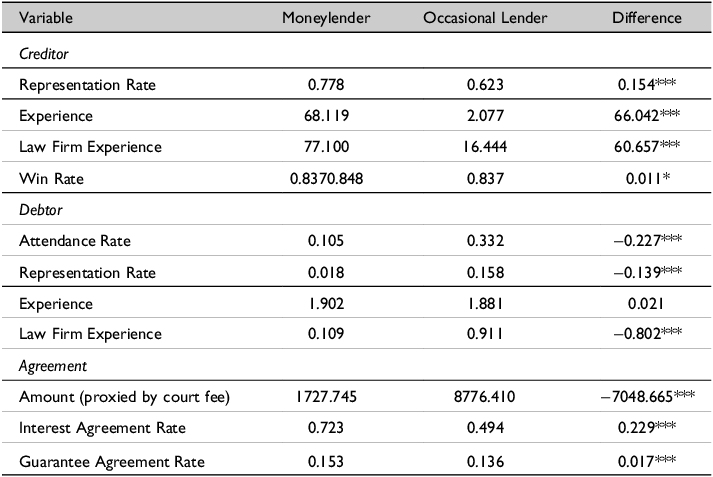

Table 1 presents descriptive data through paired t-test comparisons. Consistent with Hypothesis 1(a), unlicensed moneylenders possess stronger litigation capabilities and achieve better case outcomes compared to occasional lenders. Moneylenders are represented more frequently (77.8% vs. 62.3%), have greater experience in court (68.1 vs. 2.0 times), and employ more experienced law firms (77.1 vs. 16.4 times). They also write more professional contracts that include explicit terms about interest rates and guarantee/collateral measures. Specifically, 72.8% of moneylenders’ agreements specify interest rates and 15.6% outline collateral measures, significantly higher than those of occasional lenders, which are 49.4% and 13.5%.

Table 1. Descriptive Data and Paired t-tests between Moneylender and Occasional-lending

Note: The table presents paired t-tests comparing debts from moneylenders and occasional lenders. In court, moneylenders exhibit superior legal resources and litigation experience. Debtors facing moneylenders have less access to legal resources and show lower activity in trials. Compared to occasional lenders, moneylenders tend to issue smaller loans and more frequently include explicit terms in agreements regarding interest rates and guarantee/collateral measures.

Consistent with Hypothesis 2(a), debtors opposing moneylenders face greater obstacles in accessing justice. Only 1.8% have legal representation, compared to 15.8% of those facing occasional lenders, and a mere 10.5% attend trials, substantially less than the 33.2% facing occasional lenders.

Moneylenders also achieve a higher win rate than occasional lenders (84.8% vs. 83.7%, p<0.05). The difference is relatively modest, partly because most cases are just routine disputes without too many controversial legal issues. But it still shows that moneylenders, albeit semilegal, come out ahead of their occasional-lending counterparts. Later analysis will show that the uniqueness of unlicensed moneylending not only derives from the raw difference in win rates, but also from the unique correlation between the party’s capability and case outcome.

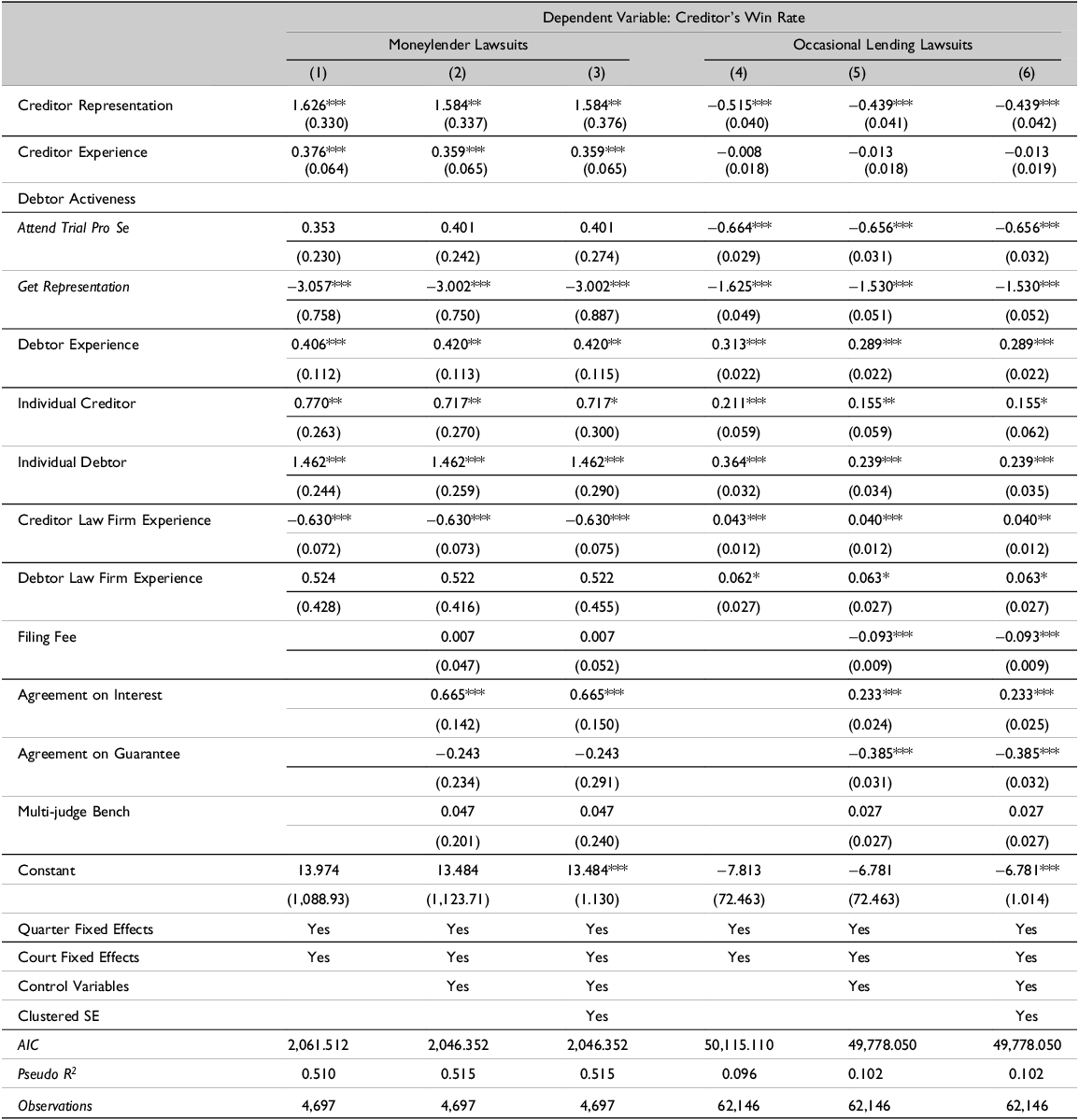

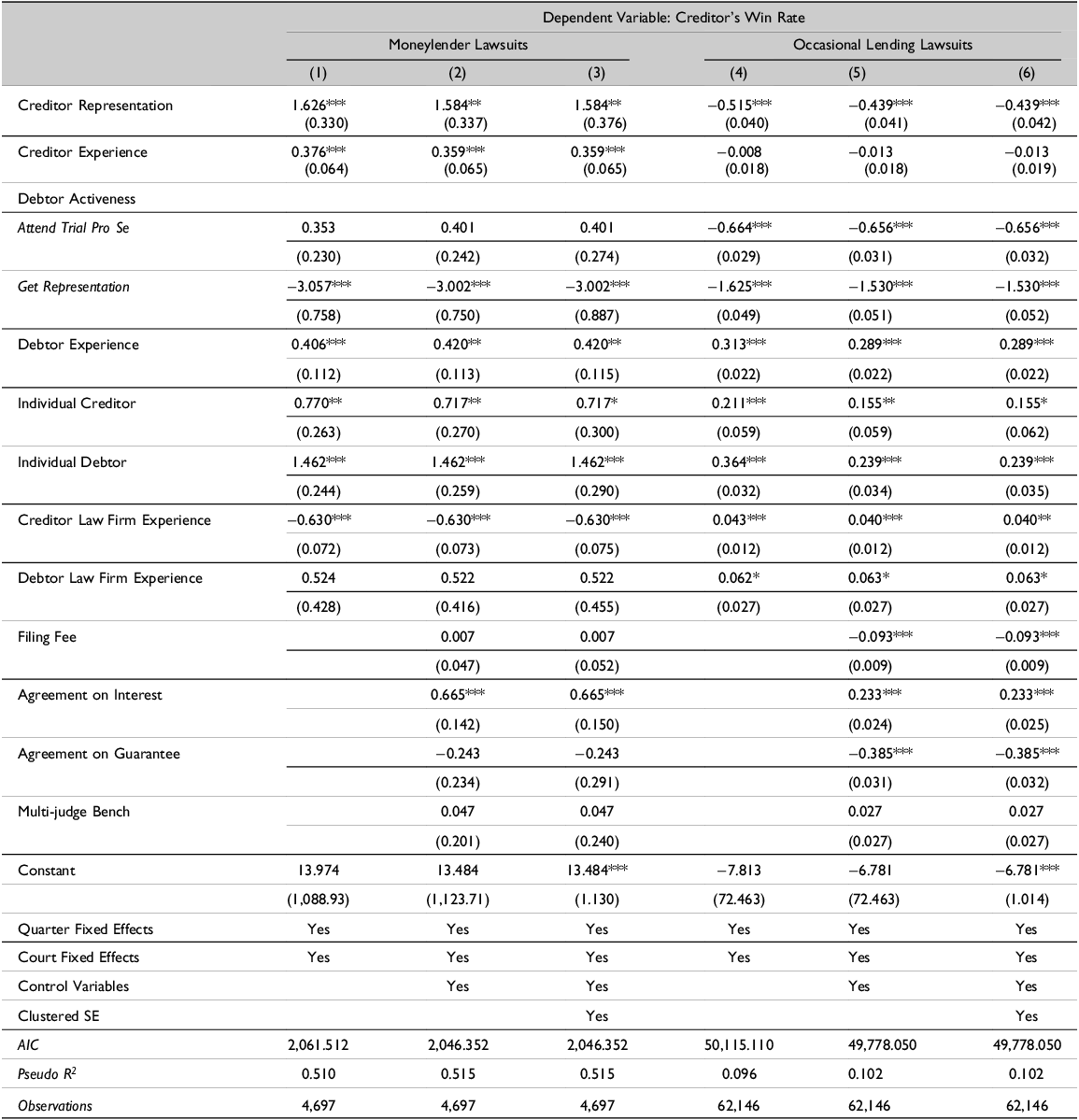

Table 2 reports the regression results of equation 1. Models one to three include lawsuits on unlicensed moneylender lending, and models four to six include lawsuits on occasional lending. For both groups, we first present the estimate with variables measuring party capabilities only, then add control variables in models two and five, and then cluster the standard errors at the court level in models three and six. All six models add court-specific and quarter-specific fixed effects. The marginal effects of each coefficient are reported in Table A3. For robustness checks, Table A4, Figures A1, and A2 report the performance metrics of the models.

Starting with Hypothesis 1(b), the positive correlation between party capability (including both creditor representation and litigation experience) and win rates only stands in unlicensed moneylender lawsuits, but not in occasional lending lawsuits. Given other conditions unchanged, both representation and litigation experience are positively correlated with the win rates of moneylenders. Conversely, win rates of occasional lenders are even negatively associated with representation and show no significant correlation with increased litigation experience. This indicates that compared with occasional lenders, unlicensed moneylenders not only enjoy more but also benefit more from their abundant legal resources and effectively learn from past experiences. For occasional lenders, the negative relationship between representation and win rates might imply their litigation behaviors of selectively hiring lawyers, but only when they perceive the cases to be too weak to defend. In China, winning a case is in no way equivalent to getting the money back. Creditors sometimes take years to win a case, but they can’t get any money back eventually. Thus, occasional lenders are likely to be ultra-prudent in any additional expenditure, while moneylenders bring lawsuits at scale with seasoned legal teams. The result conforms to the party capability thesis that “haves” not only enjoy better legal resources and more experience, but also benefit more from these resources.

More interestingly, the effect of debtor’s activeness is nuanced between the two types of lending, which confirms Hypothesis 2(b). We set the reference level as the debtors with the lowest activeness who neither attend courts nor get representation. Compared with those “least active debtors,” debtors facing occasional lenders benefited incrementally from attending trial alone and getting representation, as evidenced by both coefficients being negatively associated with creditor win rates.

However, for debtors facing unlicensed moneylenders, the effect of attending trials alone is no longer significant. This implies that professional legal help may be vital where the more sophisticated moneylenders with potential predatory practices make it harder for debtors to conduct efficient self-defenses. In robustness checks, we set the reference level to medium activeness (attending trials alone without representation) to confirm that the marginal effect of getting representation is still statistically significant (Table A9).

Additionally, for both types of lawsuits, the win rate of creditors is positively associated with debtor experience. This casts doubt on the traditional notion that “repeat-players” always come out ahead. In lending lawsuits, repeat-player debtors are those who borrow money from various sources and probably face financial hardship. For creditors, similarly, facing individual debtors is positively associated with higher win rates. These findings suggest debtors with lower capabilities are likely to be exploited by creditors, especially unlicensed moneylenders.

Finally, for control variables, a clearer agreement on interest rates is positively associated with a higher win rate for creditors in both types of lawsuits, indicating that clear terms can be helpful to creditors. The amount of the filing fee (in proxy of the amount of debt) and the guarantee agreement are negatively associated with the win rates of occasional lenders, but the effects are not significant in moneylending lawsuits. Neither is the number of judges on the bench significantly associated with case outcomes.

In brief, the regression results reveal that lawsuits brought by unlicensed moneylenders and occasional lenders differ greatly in how case outcomes and party capabilities are correlated. Compared with occasional lenders, unlicensed moneylenders not only enjoy stronger party capabilities but also benefit more from these resources. Debtors opposing these moneylenders not only suffer from severe hurdles in accessing justice, but also face potential exploitation that only professional legal help can address. These quantitative results confirm the first two hypotheses.

Qualitative Evidence

Qualitative evidence, together with our interview data, further explains how moneylenders take advantage of the vulnerable debtors and why legal help for debtors might be effective. In our dataset, there is an individual debtor called Mr. Yue, who appeared 12 times in five different trial courts. He only lost the last case in 2019, before which no debtors attended the trial. But in this last case, the debtor, Mr. Zhao, appeared with a lawyer.Footnote 14

Mr. Yue claimed that Mr. Zhao borrowed ¥200,000 (approximately $30,000) in cash at a 2% monthly interest rate—the legal cap at the time—for a six-month period starting in December 2016. The two had met as taxi drivers earlier that year. According to Mr. Yue, Mr. Zhao needed the funds to pay wages for a construction project.

Mr. Zhao, however, gave a radically different account. He said he first encountered Mr. Yue after receiving a loan offer card at the Shanghai Pudong airport in early 2016. Needing money for a wedding, he borrowed ¥5,000 from two men (including Mr. Yue), agreeing to repay ¥6,800 in two months—a monthly interest rate of 18%, nine times the legal cap. After repaying, he borrowed another ¥20,000 on similar terms. When he struggled to repay on time, he was forcibly taken from his home one day in December, slapped, and coerced into signing a blank agreement in a car. Mr. Zhao said the lenders staged a photo of him receiving cash—which he never actually got—and threatened to harass his family if he refused. According to Mr. Zhao, both his wife and mother-in-law were suffering from schizophrenia, with a son in middle school. Fearing for the family’s safety, he did not contact the police until he received the court subpoena.

At trial, Mr. Zhao’s lawyer argued that the 200,000-RMB debt was fabricated, and that the agreement was a blank document signed under duress. The lawyer also noted it was suspicious that such a large loan was allegedly made in cash, rather than by bank transfer. The lawyer asked the court to dismiss Mr. Yue’s claims and to transfer the case to the police to pursue Mr. Yue’s potential criminal liabilities.

Facing this Rashomon, the court emphasized the necessity to conduct “a particularly detailed review of the facts.” The decision noted that, unlike earlier cases where only the creditor appeared, Mr. Zhao’s presence and legal representation allowed an alternative narrative where “several reasonable doubts have been raised.” The judges questioned Mr. Yue’s financial capacity, found the cash transaction implausible, and noted inconsistencies in the documentation. They ultimately dismissed the claim due to insufficient evidence.

Mr. Yue’s trick was a typical “trap loan (taolu dai),” where fabricated debts are disguised by legal tricks. Note that Mr. Yue had never lost a case until a debtor appeared and contested the facts. Certainly, we cannot conclude that every one of Mr. Yue’s previous claims was fraudulent, but prior court records did hint at concerns. For example, a 2017 ruling noted that the borrower’s name was added after the loan agreement was signed, suggesting the use of a template contract. Lacking contrary evidence, however, the court still ruled in Mr. Yue’s favor.Footnote 15 This case study conforms with the quantitative finding that the debtor’s trial activeness, especially professional legal help, can be vital to case outcomes when an unlicensed moneylender is involved.

During the interview, a judge told us that moneylenders usually “play tricks,” and “the most critical” part of judicial decision making is to decide how well the debtor side makes a defense (JD-05-2023):

Intentionally or not intentionally, they (moneylenders) will hide something. Once we met one who does car-mortgage services. When it filed the lawsuit, it submitted a manipulated bank statement with a much higher interest and penalty fee than the original amount. But we couldn’t find it ourselves because it’s hidden in secret. We need the defendants to come and tell us at least some clues. If the debtor is represented by a lawyer, the lawyer is likely to make these arguments. But without a lawyer, it’s hard for the debtor to come up with these professional defenses and to provide such evidence himself/herself.

Noted by another judge (JD-01-2023),

We of course have concerns about potential fraud or other possibilities that could void the contract, but the defendant needs to at least tell us something and provide preliminary evidence. The court needs preliminary evidence for such arguments to proceed. Generally, without a lawyer, the defendant is unable to provide such evidence.

A lawyer mentioned something similar: “We once filed a lawsuit only because we knew that the defendant would not be able to attend the trial as he/she had been put [in] the jail. If he/she attended that trial and made defense, we were likely to lose.” (LY-02-2023) Such a litigation strategy has also been confirmed by a judge, who noted several trials where lawyers drop the lawsuit only after seeing the defendant attending the trial (JD-02-2023). It seems absurd, but that is how a private lending lawsuit works in reality.

In summary, this section tests the first two hypotheses that make litigation a viable option for unlicensed moneylenders: the moneylenders’ own superior legal resources to navigate the edge of judicial enforceability and the debtor’s lack of legal help. For moneylenders, the positive correlation between their legal resources and win rates distinguishes them from their occasional-lender counterparts. For debtors, the lack of legal help put them into a more vulnerable position where moneylenders could take advantage of. We acknowledge the lack of systematic data on why debtors remain passive, but some second-hand resources suggest potential reasons, including limited legal consciousness and opportunistic avoidance (Workers’ Daily Reference Daily2018). We hope future research can explore these dynamics more systematically.

Top-filers case studies and judicial preference

What are the legal tricks that unlicensed moneylenders most frequently play in courts? What makes judges—knowingly or unknowingly—allow moneylenders to collect semilegal debts? We answer these questions and test the third hypothesis through case studies and interview data. We choose to analyze those “top-filer moneylenders” who filed the highest number of cases in the dataset because their business models can be representative of the entire industry. Interestingly, the top-five individual and top-two business moneylenders are all directly or indirectly related to Fintech platforms. Of them, the two most common business models are the “super-lender model” and the “debt-buyer model.” To be sure, not all unlicensed moneylenders operate through Fintech (such as the case of Mr. Yue above), and not all Fintech creditors fall outside the regulatory perimeter. That said, the empirical overlap between top-filers and Fintech, whether through direct involvement or indirect connections, suggests a strong practical association between Fintech and unlicensed moneylending.

The super-lender model

This model refers to a group of “super moneylenders” who register themselves as random lenders on P2P platforms but, in fact, are personally affiliated with these platforms through ownership or operational control. As explained above, P2P lending aims to make finance more inclusive by connecting those in need of money with those possessing surplus capital. Designed as an information intermediary, a P2P platform is expected to serve as a marketplace inviting “random rich guys” together who would otherwise be scattered around the market.

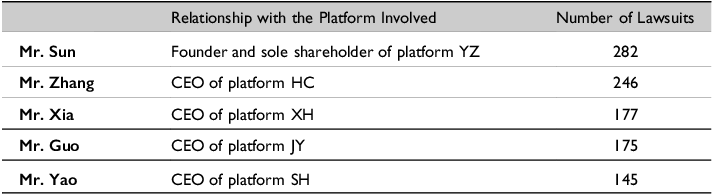

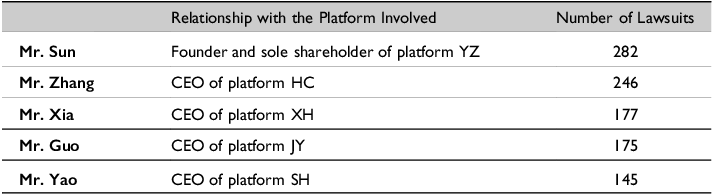

By contrast, the top five individual filers in Shanghai courts exhibited more than random affluence, suggesting that these P2P platforms operated as credit providers rather than information intermediaries. These five top-filers—Mr. Sun, Mr. Zhang, Mr. Xia, Mr. Guo, and Mr. Yao, respectively—brought as many as 282, 246, 177, 175, and 145 lawsuits. Not only are they prolific litigators with unreasonable records of lawsuits for normal people, but they are also personally affiliated with the P2P platform that matches them with the debtor in every single case. Searching their names in the Chinese Business Record Database, we find that all of them are either the legal representative, actual controlling person, or the executive head of a then-popular P2P platform in China, as shown in Table 3.

Table 2. Determinants of Creditor’s Win Rate

Note: The table presents results of logistic regression where the dependent variable is 1 if the creditor fully wins the case. Coefficients are expressed in terms of odds ratios. Models one to three include lawsuits on moneylender lending, and models four to six include lawsuits on occasional lending. We first present the estimate with variables measuring party capabilities, then add control variables in models two and five, and then cluster the standard errors at the court level in models three and six. All six models add court-specific and quarter-specific fixed effects. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

Table 3. Top Five Individual Filers in Shanghai Courts

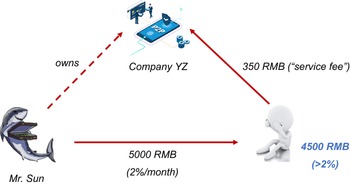

Taking a typical lawsuit brought by Mr. Sun in 2016 as an example,Footnote 16 Mr. Sun claimed that he was matched with a debtor, Mr. Guan, by platform YZ. A “loan agreement” was signed between Mr. Sun, Mr. Guan, and the platform, stipulating that Mr. Sun agreed to lend ¥5000 (approximately $700) to Mr. Guan at a 2% monthly interest rate, the then-cap of the legally protected interest rate. Besides this loan agreement, Mr. Guan signed another “service agreement” to pay ¥350 to the platform for its bridging effort. Then, Mr. Sun transferred ¥5000 to Mr. Guan, after which Mr. Guan transferred ¥350 to the platform. In fact, Mr. Sun was the founder and sole shareholder of platform YZ. Figure 2 sketches this business model.

Figure 2. The Super-lender Model (Mr. Sun)

Figure 3. The Debt-buyer-plus-super-lender Model (Mr. Yan)

The super-lender model is attractive in two aspects. First, the platform (YZ) could circumvent the licensing requirement of financial lending by using the identity of the individual person (Mr. Sun). Such an individual becomes the “nominal lender” and enjoys all the legal rights to collect these debts. Though it is still semilegal for individuals to engage in the lending business, the risk of contract unenforceability is much lower. These super moneylenders can argue that they merely “happen to” own extra money and want to make better use of it through this industry.

Second, by involving the platform in play and charging an additional amount of service fee, the controlling person could receive a larger base of customers and sidestep the usury regulation. In the case above, Mr. Guan only received ¥4650 in total, but he had to pay interest based on the nominal amount of the principal, which was ¥5000. Put differently, the actual monthly interest rate was higher than 2% (5000*2%/4650), exceeding the legally protected cap. This is a typical predatory lending practice by charging excessive up-front fees (kan tou xi). Given that we know the relationship between Mr. Sun and platform YZ, it becomes clear that this tactic was used to circumvent the usury regulation by artificially distinguishing the assets of Mr. Sun and his own company, though they are highly likely to be commingled.

Therefore, it gradually became a common practice for a P2P platform to name an internal person (usually the executive head) to issue loans in the name of the individual. The ultimate goal is to ensure that the lending contract, which does not fully comply with the law, can still be enforced in courts. The designs of the business model further confirm the adept use of legal resources by moneylenders.

Are judges aware of these moneylender tricks? Case studies suggest an answer of yes. Mr. Sun won 281 out of 282 cases. The only case he lost was even appealed and reversed. That was a late-2016 case, very early in his litigation record, decided by the Pudong New District People’s court. The court voided the contract on the ground that this business model “disguised illegal intentions with a legal form.” Noted by the court:

Private lending only refers to lending activities between natural persons and non-financial enterprises outside the national financial regulatory system … as an information intermediary, YZ is not a financial institution and must not take deposits or issue loans by itself … As the legal representative of YZ, Mr. Sun conflated his personal identity with that of the company … He used the platform to charge a service fee to circumvent interest rate restrictions and seek illegal profit. He also circumvented regulations that prohibit unlicensed entities from engaging in [the] lending business. The contract disguised illegal intentions with a legal form and shall therefore be voided. Footnote 17

Reviewing this decision today, the judge was a fortune teller. It was not until the end of 2019 that the SPC announced the illegality of unlicensed moneylender-issued debt. Yet, for this late-2016 case, the appellate court, Shanghai No.1 Intermediary People’s Court, overruled the first-trial decision in early 2017. The second-trial decision noted:

Although the appellant (Mr. Sun) serves as the legal representative of the platform, there is no legal restriction that he cannot be a lender, and there is no sufficient evidence here that the appellant’s assets are commingled with the company’s assets. Therefore, the fact that the appellant, in his personal capacity, signed the loan agreement with the appellee, does not violate [the] law and the validity of the contract shall therefore be held. Footnote 18

With this decision, Mr. Sun’s claim was ultimately supported, and he never lost another case afterwards. This record of ruling demonstrates the nuanced judicial preference that enables the informal moneylending model to endure in courts before 2020. Why do judges prefer moneylenders? As discussed in Section 3, there are two key legal questions: whether issuing loans without taking deposits constitutes “banking business,” and, if so, whether financial regulations are considered “imperative regulation” for contract voidance. In Mr. Sun’s case, the appellate court did not provide a detailed legal analysis, but it clearly did not believe that any mandatory legal provision prohibited Mr. Sun, as an individual, from issuing loans in his own capacity. The court did raise concerns about contract validity if the Fintech platform were deemed the actual lender in case of asset commingling, but it did not pursue this concern further.

This line of reasoning reflects a broader pre 2020 pattern that favored freedom of contract and minimized judicial interference in business arrangements, particularly where regulatory statutes remained ambiguous. Beyond Shanghai, courts also often concluded that issuing loans alone does not constitute “banking business” under Article 19 of the Banking Supervision Law, which they interpreted as requiring deposit-taking practices.Footnote 19 Likewise, courts frequently held that financial regulations, unless explicitly labeled “imperative,” do not qualify as “mandatory provisions of law” sufficient to void a contract.Footnote 20

But is this doctrinal reasoning purely “legal?” As later developments revealed, judicial interpretations of regulatory ambiguity were deeply shaped by the courts’ institutional embeddedness in China’s broader economic and political governance. In the SPC judge-authored publication cited above, it is remarked that “formal financial institutions are still unable to fully meet market demand. In order to maintain business operations, short-term lending by enterprises with idle capital has, to some extent, helped ease the financing pressures on small and micro enterprises. For now, this is necessary” (Du and The SPC First Civil Division Reference Du2015, 271). This suggests that the judiciary viewed private informal lending as a necessary workaround to structural credit constraints, particularly for borrowers excluded from formal banking. Validating such contracts reflected a more efficiency-based approach for contractual freedom, while treating it as illegal would signal a more conservative view of financial regulation (Li and Shen Reference Li and Shen2020). As one judge (JD-04-2023) explained,

The policy environment definitely impacts our decision-making, especially in the field of financial regulation. Before 2019, the regulation was relatively relaxed, so we avoided interpreting the law in a way that [was] unfavorable to these moneylenders. But now the regulatory environment has become conservative again. I have been used to this kind of policy changes, sometimes “left” and sometimes “right.” Policies basically change from one extreme to the other. I don’t know where the root cause is.

We also learned that improving China’s “Doing Business” rank—an annual World Bank index that included contract enforcement metrics—had become a significant political task for courts around 2016 (JD-06-2023). This suggests that the judicial preference was shaped not only by support for Fintech but also by broader economic objectives to improve the business environment through contract enforcement. Further, when we provided the fact pattern to a judge from the appellate court and asked for an opinion, the judge expressed empathy for the second-trial decision (JD-02-2023).

In second trial, we need to ‘stand higher (zhan de geng gao)’ when making decisions. It’s risky if a strong business party reports to the government that our decision hampers [] industry growth if the industry is being encouraged at that time … To void the contract is to void lots of contracts afterwards; to enforce the contract is to show support to the industry, so we need to make sure we have the big policy as back-up when ruling against a new business model.

In summary, the story of Mr. Sun and the contrast between first and second instance decisions offers a vivid example of how political considerations are woven into legal analysis. Backing up the policy environment thus yielded a de facto “judicial preference” towards unlicensed moneylenders even though they resided in a grey area of financial regulation. Nonetheless, the first-trial decision indicates that debtor protection has existed as a conflicting value. Judges constantly face the tension between business hospitality and vulnerable protection, and this dilemma will be further illustrated in the next case study.

The debt-buyer model

The second model identifies another grey area of financial regulation: third-party debt buyers. The model is featured by a third-party debt buyer collecting debts originally from others transferred to them, and filing the lawsuit. In our dataset, the top two business moneylenders are both third-party debt buyers. The top business filer, company CK, has a full win record of 437 cases, making it also the top filer across all private moneylenders. In a typical case it broughtFootnote 21 a debtor borrowed ¥12,000 under a 12-month loan agreement with an annual interest rate of 10.80% from a random lender matched by a P2P platform, company NW. The agreement contained a special clause that if the debtor failed to repay the loan, the original lender could transfer the debt to a third-party debt buyer, company CK. In the dataset, CK enjoys a full win record of 437 cases.

The second-top business filer, company JS, appears to be more interesting as it combines both the debt-buyer and the super-lender models. Company JS enjoys a full-win record of eighty lawsuits. Upon first glance, it is similar to other debt-buyers: purchasing debts from original debtors and bringing lawsuits in its own name. However, a deeper look suggests a more nuanced relationship: for all lawsuits brought by JS, the original creditor was the same person—Mr. Yan—and all debts are matched by the same P2P lending platform called ZF. Not surprisingly, Mr. Yan was the CEO and legal representative of platform ZF.

As Figure 3 shows, Mr. Yan used the super-lender model first and then sold the debts to a third-party buyer, JS. That was why JS became a repeat player in the Shanghai courts. The business record database showed that Mr. Yan was one of the two inaugural investors of JS when the company was established in 2014, suggesting a potential personal affiliation. In other words, it is highly likely (though we don’t have direct evidence) that Mr. Yan first used his own P2P platform to issue loans, then used another closely-related company to buy debts and sue.

Why bother? Why couldn’t Mr. Yan sue the debtors directly, like those super lenders in the first model? Again, all the “tricks” are to ensure contract enforceability in courts. There are three potential benefits for the debt buyer. First, Mr. Yan himself might want to keep a low profile to avoid potential political censorship as a repeat player in courts. After all, it could be suspicious to appear a hundred times in courts as a businessman. Second, Mr. Yan and his legal team might be more prudent about potential legal risks. Starting from 2017, there have been policy winds in several provinces, including Jiangsu, where platforms ZF and JS were registered, to void the contract of individual moneylenders. It was thereby reasonable for Mr. Yan’s legal team to have this concern. Third, it might be expected as well that the potential risks originating from the semilegal factors in original debts would all disappear once the debts have been transferred. By selling the debt to a third party, it is likely that the judge will not pay sufficient attention to the semi-legality of the original debts, such as the unlicensed status of Mr. Yan and the service fees that circumvented the usury regulation. Either way, selling debts to a third-party could serve as a double safety net to ensure judicial enforceability. If the debt buyer is personally associated with the original creditor, the additional costs would be only paperwork.

Despite the full win record of JS, we surprisingly found that judges always asked the company to “voluntarily” change its claims. While JS claimed for all types of semilegal fees when bringing the lawsuits, it “voluntarily” changed the claims to only ask for the principal amount of return in the end. The legal consequence, therefore, would be the same as if the contract were voided, which was a de facto failure.

Why would moneylenders “voluntarily” change their claims to ask for less? During interviews, we were told that voluntarily changing claims by creditors is more often initiated by judges. It happens when judges tend not to support the creditors but are not willing to explicitly rule against them either. According to a judge (JD-07-2023),

Our judges will advise the party to withdraw the lawsuit or reduce claims. We will talk to them, make an implication that they are not likely to win completely because of our concerns, or the regulatory goals to protect financial consumers. Especially in these high-volume dockets (piliang anjian), we are afraid to convey a signal to the market too directly, so we just keep persuading the party to ask for less. It’s similar to a mediation, but often only between the moneylender and us. If they do not agree to do so, then the case would be suspended, sometimes until they agree to withdraw or change the claims.

In the case of JS, the presiding judges might have concerns about fully supporting its claims because there was evidence on Mr. Yan’s asset commingling with that of platform ZF. This issue was not solved, even if Mr. Yan had transferred the debts to Company JS. It was highly likely that the judges saw through the tricks and did not want to encourage the business model, which was predatory in essence. Yet, judges did not rule against it either, potentially because they did not want to convey a negative signal to the market. They might want to avoid being overruled by an appellate court as well, like the case of Mr. Sun, as the reversal rate has been a key evaluation criterion for Chinese judges (Kinkel and Hurst Reference Kinkel and Hurst2015).

A widely circulated news report from early 2018 offers additional support for this discreet judicial intervention. In that case, a grassroots court in Nanning, Guangxi province, handled hundreds of lawsuits filed by a single plaintiff against over 400 college students from across at least five different provinces (The Paper 2018a). The plaintiff was a lending platform marketing a product called “704 School Flower,” which specifically targeted college students with seemingly easy access to small loans—typically around ¥7,000 (about $1,000). Yet the platform imposed high default penalties and obscured repayment schedules through misleading app design. A student who borrowed ¥2,000 ended up owing more than that amount in penalties alone. Strikingly, none of the student defendants appeared in court. It turned out that most of the students were not living in Nanning and claimed that they never received a service notice from the court. Confronted with over 400 absent student defendants, judges in Nanning eventually traveled over 350 miles to Guiyang to meet with some students. They also coordinated with university administrators, education authorities, and social security departments to help mitigate potential legal and credit consequences. Through these efforts, several students who agreed to repay the principal were able to reach settlements with the platform with the penalty fees waived. This story echoes with the pattern in our data that while judges refrain from directly ruling against moneylenders out of deference to the policy environment, they still try to temper the effects of predatory lending through even informal ways, including mediation.

Are these results a success for the moneylenders? Probably not. But they represent a decent exit for moneylenders like Mr. Yan once regulatory winds began to shift. More importantly, they reveal the ambivalence in judicial decision making. Judges often recognized the exploitative nature of certain models but were caught between policy deference and equity concerns. Thus, judicial preference towards unlicensed moneylenders existed but was not absolute. Judges sometimes use informal ways—such as encouraging moneylenders to adjust the claims or mediation—to strike a balance.

Discussion and conclusion