Introduction

Broadly defined, empathy refers to an individual's reaction to observing another person's experiences (Davis, Reference Davis1983). For some authors the term ‘empathy’ exclusively describes the ability to share the feelings of others; the ability to understand the mental states (including emotional states) on a cognitive level is then referred to as the theory of mind (de Vignemont and Singer, Reference de Vignemont and Singer2006; Preckel et al., Reference Preckel, Kanske and Singer2018). The general consensus exists that when describing social functioning in reaction to interpersonal situations one should distinguish between a more cognitive reaction, including reasoning about other people's mental states, and a more affective reaction, including the sharing of affective states and feeling of concern for others (Davis, Reference Davis1983; Preckel et al., Reference Preckel, Kanske and Singer2018). Taking into account the multi-dimensionality of the concept, Davis (Reference Davis1983) developed the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) that assesses four different dimensions of trait empathy or social functioning. Briefly, personal distress describes uncomfortable feelings when confronted with another's suffering and empathic concern describes compassion and concern for others. Both are considered rather affective empathic responses. Perspective-taking, a measure of cognitive empathy, touches on the understanding of other people's emotional states and fantasy, the tendency to imaginatively transpose oneself into fictitious characters. Impaired empathy has been found in certain mental disorders including major depressive disorder (MDD) (Schreiter et al., Reference Schreiter, Pijnenborg and Aan Het Rot2013) and borderline personality disorder (BPD) (Dziobek et al., Reference Dziobek, Preißler, Grozdanovic, Heuser, Heekeren and Roepke2011), and in individuals with an experience of early life maltreatment (ELM) (Parlar et al., Reference Parlar, Frewen, Nazarov, Oremus, MacQueen, Lanius and McKinnon2014).

A number of studies have already addressed the effects of MDD on trait empathy (review by Schreiter et al., Reference Schreiter, Pijnenborg and Aan Het Rot2013). Investigations in which trait empathy is measured with the IRI in BPD, are scarcer and the findings are more inconsistent (review by Roepke et al., Reference Roepke, Vater, Preißler, Heekeren and Dziobek2012). For individuals with ELM, the number of investigations is still limited and characterized by the use of diverse instruments. In general, the most consistent findings have been reported on the affective dimensions, in that the majority of studies found higher levels of personal distress in patients with MDD and BPD (Guttman and Laporte, Reference Guttman and Laporte2000; O'Connor et al., Reference O'Connor, Berry, Weiss and Gilbert2002; Wilbertz et al., Reference Wilbertz, Brakemeier, Zobel, Haerter and Schramm2010; Dziobek et al., Reference Dziobek, Preißler, Grozdanovic, Heuser, Heekeren and Roepke2011; Thoma et al., Reference Thoma, Zalewski, von Reventlow, Norra, Juckel and Daum2011; Derntl et al., Reference Derntl, Seidel, Schneider and Habel2012; New et al., Reference New, aan het Rot, Ripoll, Perez-Rodriguez, Lazarus, Zipursky, Weinstein, Koenigsberg, Hazlett, Goodman and Siever2012; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Regenbogen, Kellermann, Finkelmeyer, Kohn, Derntl, Schneider and Habel2012; Schreiter et al., Reference Schreiter, Pijnenborg and Aan Het Rot2013), but no effects on empathic concern (Guttman and Laporte, Reference Guttman and Laporte2000; O'Connor et al., Reference O'Connor, Berry, Weiss and Gilbert2002; Wilbertz et al., Reference Wilbertz, Brakemeier, Zobel, Haerter and Schramm2010; Thoma et al., Reference Thoma, Zalewski, von Reventlow, Norra, Juckel and Daum2011; Derntl et al., Reference Derntl, Seidel, Schneider and Habel2012; New et al., Reference New, aan het Rot, Ripoll, Perez-Rodriguez, Lazarus, Zipursky, Weinstein, Koenigsberg, Hazlett, Goodman and Siever2012; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Regenbogen, Kellermann, Finkelmeyer, Kohn, Derntl, Schneider and Habel2012; Schreiter et al., Reference Schreiter, Pijnenborg and Aan Het Rot2013). Similarly, Parlar et al. (Reference Parlar, Frewen, Nazarov, Oremus, MacQueen, Lanius and McKinnon2014) found higher levels of personal distress, but also lower levels of empathic concern in individuals with ELM who also suffered from PTSD. Results for cognitive empathy in MDD and BPD have been mixed (Guttman and Laporte, Reference Guttman and Laporte2000; Dziobek et al., Reference Dziobek, Preißler, Grozdanovic, Heuser, Heekeren and Roepke2011), but a number of studies which applied the IRI, found lower levels of perspective-taking in depressed patients (Wilbertz et al., Reference Wilbertz, Brakemeier, Zobel, Haerter and Schramm2010; Cusi et al., Reference Cusi, MacQueen, Spreng and McKinnon2011; Schreiter et al., Reference Schreiter, Pijnenborg and Aan Het Rot2013), BPD patients (Harari et al., Reference Harari, Shamay-Tsoory, Ravid and Levkovitz2010; New et al., Reference New, aan het Rot, Ripoll, Perez-Rodriguez, Lazarus, Zipursky, Weinstein, Koenigsberg, Hazlett, Goodman and Siever2012) and individuals with ELM-related PTSD (2014). While there seems to be a lack of studies addressing the isolated effects of an ELM on empathy assessed with the IRI, other investigations which used different measures, found similar impairments in cognitive (Locher et al., Reference Locher, Barenblatt, Fourie, Stein and Gobodo-Madikizela2014; Nazarov et al., Reference Nazarov, Frewen, Parlar, Oremus, Macqueen, Mckinnon and Lanius2014), and affective empathy (Locher et al., Reference Locher, Barenblatt, Fourie, Stein and Gobodo-Madikizela2014; Parlar et al., Reference Parlar, Frewen, Nazarov, Oremus, MacQueen, Lanius and McKinnon2014). It should be noted that none of the studies mentioned above found significant effects on the fantasy dimension.

MDD and BPD show high comorbidity (Zanarini et al., Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg, Dubo, Sickel, Trikha, Levin and Reynolds1998) and are common sequelae of ELM (Liotti et al., Reference Liotti, Pasquini and Cirrincione2001; Plant et al., Reference Plant, Barker, Waters, Pawlby and Pariante2013; Li et al., Reference Li, D'Arcy and Meng2016). Thus, the separate investigation of one of these three factors carries the risk of being confounded by one of the other two factors. While the mentioned studies investigated the effects of MDD and BPD separately and while the effects of ELM have not been investigated independently of PTSD so far, our study aims to extend this research by including all three risk factors in one study in order to identify their specific contribution to empathy. We included all four dimensions of empathy to gain a comprehensive picture of alterations when considering the co-occurrence of all three risk factors.

As deficits in maternal empathy have been related to child psychopathology and attachment problems (Grienenberger et al., Reference Grienenberger, Kelly and Slade2005; Psychogiou et al., Reference Psychogiou, Daley, Thompson and Sonuga-Barke2008), it might also be of interest to investigate indirect effects, via empathy, on the next generation. Psychogiou et al. (Reference Psychogiou, Daley, Thompson and Sonuga-Barke2008) used a modified version of the IRI to specifically assess maternal empathy toward her own child. They found positive associations between personal distress and child hyperactivity, conduct problems, and emotional problems. Maternal empathy (collapsed score of perspective-taking and empathic concern) was negatively associated with higher child conduct problems.

As impaired empathy has been reported in individuals with ELM, MDD, and BPD, it might be an important aspect for explaining elevated levels of psychopathology in children of mothers with these conditions (Goodman and Rouse, Reference Goodman and Rouse2011; Eyden et al., Reference Eyden, Winsper, Wolke, Broome and MacCallum2016; Plant et al., Reference Plant, Pawlby, Pariante and Jones2017). So far, however, alterations in trait empathy have not specifically been addressed as a potential mechanism leading to child psychopathology in mothers with MDD, BPD, and ELM. It appears desirable to investigate the mediating role of different dimensions of trait empathy, to promote a deeper understanding of the potential role of maternal empathy in the intergenerational transmission of abuse and psychopathology.

Aims of the study

The first aim of this study was to disentangle the effects of MDD, BPD, and ELM on empathy, by including all three factors in one study. Our second aim was to investigate whether alterations in maternal empathy would mediate the effects of maternal ELM, MDD, and BPD on child psychopathology.

Method

Participants and procedure

This study was performed within the framework of the UBICA (Understanding and Breaking the Intergenerational Cycle of Abuse, http://www.ubica.de) multicenter project in Berlin and Heidelberg (Dittrich et al., Reference Dittrich, Bödeker, Kluczniok, Jaite, Hindi Attar, Führer, Herpertz, Brunner, Winter, Heinz, Roepke, Heim and Bermpohl2018a; Reference Dittrich, Fuchs, Bermpohl, Meyer, Führer, Reichl, Reck, Kluczniok, Kaess, Hindi Attar, Möhler, Bierbaum, Zietlow, Jaite, Winter, Herpertz, Brunner, Bödeker and Resch2018b; Kluczniok et al., Reference Kluczniok, Boedeker, Hindi Attar, Jaite, Bierbaum, Fuehrer, Paetz, Dittrich, Herpertz, Brunner, Winter, Heinz, Roepke, Heim and Bermpohl2018). The present study included 251 mothers and their children aged between 5 and 12 years. BPD was diagnosed in 33 mothers and MDD in remission (rMDD) in 131 mothers. One hundred and forty-two mothers had experienced ELM before the age of 17 of at least moderate severity. However, in our analyses, we used a dimensional score for ELM composed of the main scales (sexual, physical, and emotional abuse, neglect, and parental antipathy) of the Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse Interview (CECA, Bifulco et al., Reference Bifulco, Brown and Harris1994). There was an intentional co-occurrence of two or all three risk factors in parts of our sample, consisting of mothers with/without ELM and/or rMDD and/or BPD (see Table 1 for detailed information).

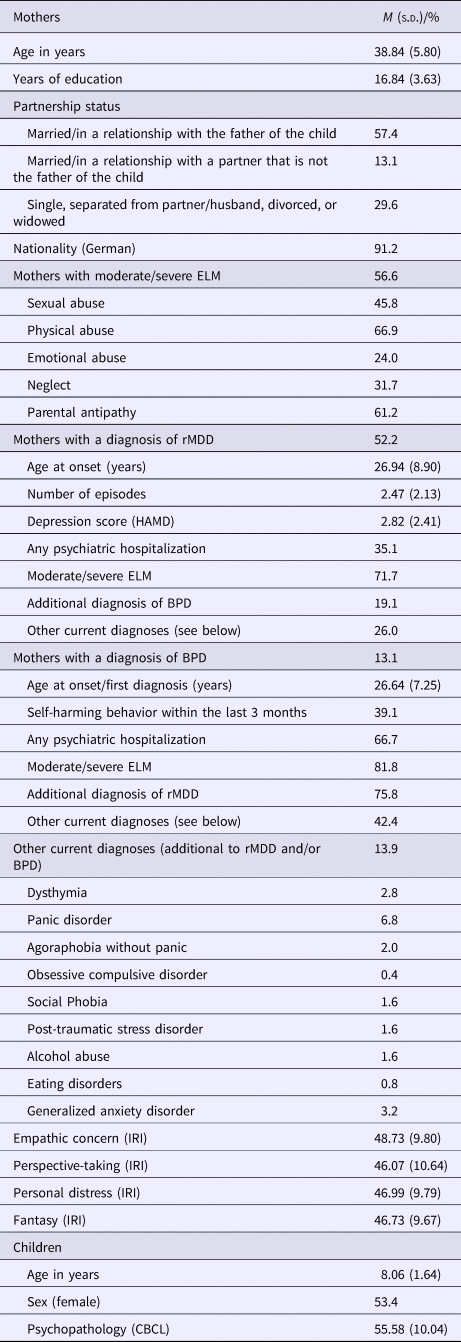

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

M, mean; s.d., standard deviation; ELM, early life maltreatment; rMDD, major depressive disorder in remission; BPD, Borderline Personality Disorder; HAMD, Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression; IRI, Interpersonal Reactivity Index (norm scores); CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist (norm scores)

N = 251.

Mothers with ELM, rMDD, and BPD, as well as healthy mothers and their children were recruited by advertisement (poster and flyer) in psychotherapeutic, psychiatric, gynecological, and pediatric outpatient clinics. Mothers with MDD had to be in a remitted state to exclude the risk that the effects of acute depression would override the effects of BPD and ELM. Acute MDD symptoms might have caused bias in response behavior (Gartstein et al., Reference Gartstein, Bridgett, Dishion and Kaufman2009) and interfered with participation in the study. Thus, we chose to investigate mothers with MDD in remission, with depressive symptoms at a sub-clinical level rather than acute MDD, and only mothers with a Hamilton Depression Scale (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1960) score of seven or less were included. Mothers with BPD had to be non-suicidal and sufficiently stable (i.e. not hospitalized) to participate in the study.

The exclusion criteria for the mothers included a lifetime history of schizophrenia, neurological diseases, manic episodes, an acute depressive episode, and anxious-avoidant, or antisocial personality disorder as these conditions could potentially impair their participation in the study. Mothers with BPD or rMDD were allowed to have a comorbid current or lifetime DSM-IV axis I diagnosis (other than acute MDD); this was controlled for in our analyses. A further exclusion criterion was the taking of benzodiazepines within the last 6 months. Medication with other psychotropic drugs did not represent an exclusion criterion, as long as the dosage had been stable for at least 2 weeks prior to entering the study. The exclusion criteria for the child participants included a previous diagnosis of autistic disorder or intellectual disability. Because the aim of our project was to investigate the effect of maternal factors on child behavior, the mothers and children had to live together. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants after the procedure had been fully explained.

Measures

Empathy

We administered the German version (Paulus, Reference Paulus2009) of the IRI (Davis, Reference Davis1980; Reference Davis1983), a self-rating questionnaire which differentiates four dimensions of empathy (seven items each): Perspective-taking refers to the cognitive aspect of empathy, measuring the ability to spontaneously adopt another's point of view. Fantasy assesses a person's tendency to imaginatively transpose themselves into the actions and feelings of fictitious characters in movies, books, or plays. Empathic concern and personal distress both touch on emotional reactions to interpersonal situations. Personal distress assesses more ‘self-oriented’ feelings such as discomfort, anxiety, unease in emotional and tense interpersonal situations while empathic concern measures more ‘other-oriented’ reactions to others' misfortune, such as concern or sympathy. The German version of the IRI has shown good values in reliability, factorial validity and item analyses (Paulus, Reference Paulus2009). German sex- and age-adjusted T-norm scores for each of the four dimensions were entered in our analyses.

Maternal ELM, rMDD, and BPD

The maternal history of depression (and other diagnoses of DSM-IV axis I disorders) was assessed using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.; Lecrubier et al., Reference Lecrubier, Sheehan, Weiller, Amorim, Bonora, Sheehan, Janavs and Dunbar1997) which is a fully structured, diagnostic interview which has been reported to achieve good inter-rater reliability (Sheehan et al., Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Janavs, Weiller, Keskiner, Schinka, Knapp, Sheehan and Dunbar1997, Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller, Hergueta, Baker and Dunbar1998). The International Personality Disorder Examination (Mombour et al., Reference Mombour, Zaudig, Berger, Gutierrez, Berner, Berger, von Cranach, Giglhuber and von Bose1996; Loranger et al., Reference Loranger, Janca and Sartorius1997), a structured clinical interview with an established reliability and validity, was administered to assess BPD and other personality disorders (antisocial and anxious-avoidant). The interviews were conducted by clinical psychologists (holding bachelor or master's degrees), following training by experienced users. For rMDD and BPD, a binary variable (yes/no) was entered in our analyses.

Maternal experiences of ELM were assessed using the CECA (Bifulco et al., Reference Bifulco, Brown and Harris1994; Kaess et al., Reference Kaess, Parzer, Mattern, Resch, Bifulco and Brunner2011). This is a semi-structured, clinical interview which uses investigator-based ratings to collect retrospective accounts of adverse childhood experiences (up to an age of 17 years), such as sexual, physical, and emotional abuse, neglect, and parental antipathy. The data were rated according to manualized threshold examples and predetermined criteria, using a four-point scale of severity. We entered the sum score of the five main CECA dimensions into the analyses, with higher scores indicating higher severity.

Child psychopathology

To assess child psychopathology, we used the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991; Arbeitsgruppe Deutsche Child Behavior Checklist, 1998) which is a parental questionnaire about children's emotional and behavior problems. The German version of the instrument has shown good reliability and validity (Döpfner et al., Reference Döpfner, Schmeck, Berner, Lehmkuhl and Poustka1994). The T-value norms of the total problem score were entered in our analyses. The total problem score including 118 items showed excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.95). It has been demonstrated to correlate well with child psychiatric diagnoses in children, and thus to provide a valid indicator for mental health problems in children (Kasius et al., Reference Kasius, Ferdinand, Van den Berg and Verhulst1997; Jensen and Watanabe, Reference Jensen and Watanabe1999). The high correlation between the internalizing and the externalizing scales on the CBCL in the present study (r = 0.62, p < 0.001) indicates that the use of the total problem score did not result in undue aggregation of divergent information (Burt et al., Reference Burt, Van Dulmen, Carlivati, Egeland, Sroufe, Forman, Appleyard and Carlson2005; Bödeker et al., Reference Bödeker, Fuchs, Führer, Kluczniok, Dittrich, Reichl, Reck, Kaess, Hindi Attar, Möhler, Neukel, Bierbaum, Zietlow, Jaite, Lehmkuhl, Winter, Herpertz, Brunner, Bermpohl and Resch2018). However, to provide a more comprehensive picture of different aspects of child psychopathology, details on the results for the two main subscales (internalizing and externalizing behavior) and the more differentiated subscales (e.g. withdrawn, somatic complaint, anxious/depressed) are reported in the online supplementary material.

Data analyses

We first explored correlation coefficients between maternal characteristics (age, years of education, current relationship status, current DSM-IV axis I disorders) and the four IRI dimensions in order to identify possible confounding variables. If the correlation was significant (p < 0.05), the respective variable was used as a covariate in regression analyses. Significant associations only emerged for the presence of current axis I disorders and empathy (dimensions personal distress and empathic concern), which was therefore included as a covariate in all the regression analyses. The same procedure was applied for mediation analyses: any maternal (mentioned above) and child demographic characteristics (age, sex) which showed significant correlations with child psychopathology, were entered as covariates. Significant associations emerged for the child's age, maternal relationship status, and current axis I disorder. Thus, all mediation analyses were controlled for maternal axis I disorder, relationship status, child age, and the two maternal risk factors not included as the predictor in the respective analysis.

Using the severity of ELM, presence of rMDD, and BPD as predictors, we conducted four linear regression analyses for the four different empathy dimensions as an outcome. We used mediation analyses based on ordinary least squares regression according to Hayes (Reference Hayes2013) to investigate the indirect effects of these maternal factors, via empathy, on child psychopathology. Percentile bootstrap confidence intervals (95%) for the indirect effects (based on 10 000 bootstrap samples) entirely above or below zero were considered significant. The regression diagnostics did not reveal any signs of multicollinearity, violation of assumptions, or influential outliers. Information on the mother's years of education was missing in two cases, as well as the CBCL in two cases and information on perspective-taking in three cases. All analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 24 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) with the process macro also being used for the mediation analyses (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013).

Results

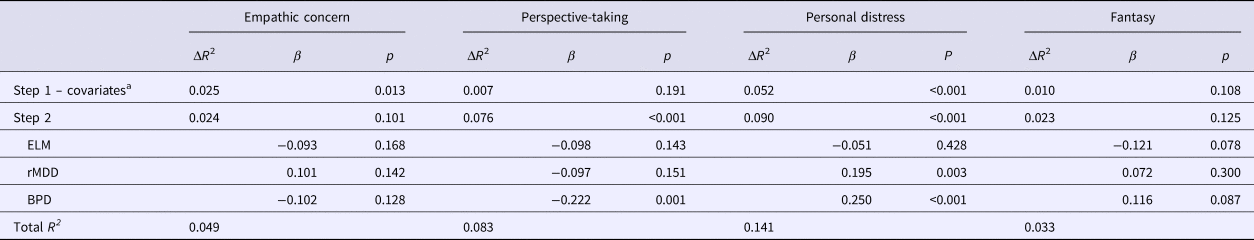

To estimate the effects of the severity of ELM, the presence of rMDD, and the presence of BPD on empathy, we conducted linear regression analyses with all three predictors in one model (Table 2). All the regression analyses were controlled for maternal current axis I disorder. The results showed that both BPD and rMDD were significantly associated with higher personal distress and BPD was significantly associated with lower perspective-taking. Other regression analyses were not statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2. Effects of early life maltreatment, depression and borderline personality disorder on dimensions of empathy

ELM, early life maltreatment (CECA sum score); rMDD, major depressive disorder in remission; BPD, borderline personality disorder.

N = 251 (perspective-taking N = 248).

a Only presence of any current DSM IV axis I disorders was included as a covariate (no other demographic characteristics showed significant association with the outcome variables).

Mediation analyses were only conducted for those dimensions of empathy which had shown significant associations with maternal ELM, rMDD, or BPD. In each analysis, we controlled for the two maternal risk factors that were not the predictors in the respective analysis (e.g. when estimating the indirect effect of BDP on child psychopathology, we controlled for ELM and rMDD) and for child's age, maternal relationship status, and the presence of maternal current axis I disorder.

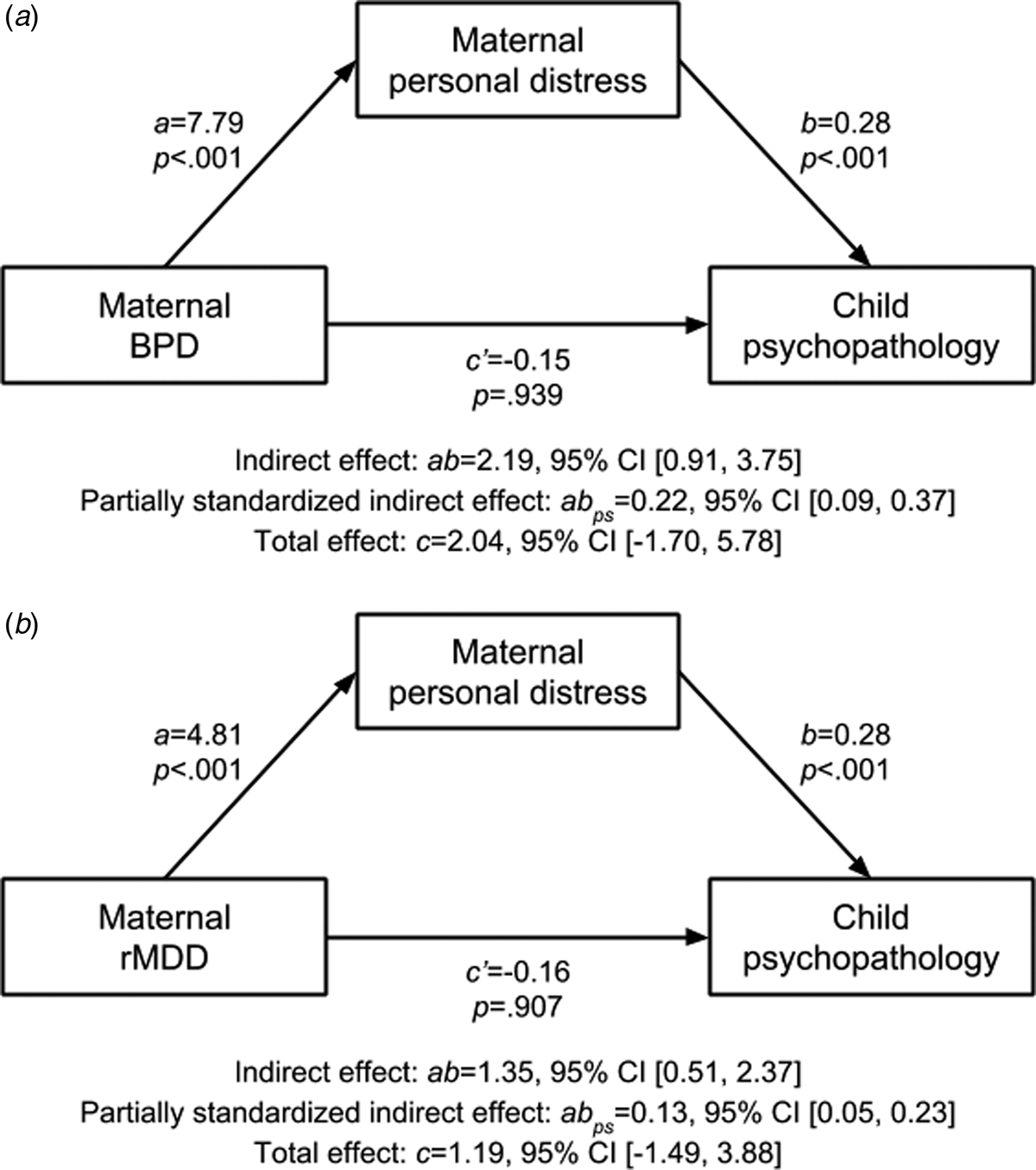

The indirect effect of maternal BPD on child psychopathology through maternal personal distress was significant (Fig. 1a). Similarly, a significant, indirect effect from maternal rMDD on child psychopathology through maternal personal distress was found (Fig. 1b). The indirect effect of maternal BPD on child psychopathology through maternal perspective-taking was not significant [ab = 0.15, 95% CI (−0.73 to 1.27)]. In the mediation model (as in the regression analysis), BPD predicted perspective-taking (a = −7.33, p < 0.001) but perspective-taking was not associated with child psychopathology (b = −0.02, p = 0.729).

Fig. 1. Mediation analyses with maternal personal distress as a mediator and (a) maternal borderline personality disorder (BPD) and (b) maternal depression in remission (rMDD) as predictors and child psychopathology as an outcome. Both indirect effects are significant as confidence intervals (CI) exclude zero. N = 249.

All analyses were conducted with the CBCL total problem score as an outcome. Similar findings were obtained when the two subscales (internalizing and externalizing behavior) and the more differentiated subscales (e.g. withdrawn, somatic complaint, anxious/depressed) were considered separately (see online supplementary material).

Discussion

We examined the effects of rMDD, BPD, and the severity of ELM on different facets of empathy and the indirect effects of maternal rMDD, BPD, and severity of ELM on child psychopathology through maternal empathy. By including all three risk factors in one analysis, we disentangled their specific effects on empathy. Having investigated the psychological mechanism underlying the effects of ELM, MDD, and BPD on child psychopathology by addressing the mediating role of empathy, the main findings of our study are: BPD and rMDD predicted higher personal distress and BPD also predicted lower perspective-taking. The severity of ELM did not have an effect on empathy when rMDD and BPD were controlled for. We found a significant indirect effect of maternal BPD on child psychopathology via maternal personal distress while controlling for rMDD and ELM. Similarly, a significant indirect effect from rMDD was found on child psychopathology via personal distress while controlling for BPD and ELM. While the majority of studies to date have focused solely on acute depression or acute depressive symptoms, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate empathy in individuals with depression in remission. Our results for elevated personal distress in women with rMDD, are in line with previous research on acute depression (O'Connor et al., Reference O'Connor, Berry, Weiss and Gilbert2002; Wilbertz et al., Reference Wilbertz, Brakemeier, Zobel, Haerter and Schramm2010; Thoma et al., Reference Thoma, Zalewski, von Reventlow, Norra, Juckel and Daum2011; Derntl et al., Reference Derntl, Seidel, Schneider and Habel2012; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Regenbogen, Kellermann, Finkelmeyer, Kohn, Derntl, Schneider and Habel2012; Schreiter et al., Reference Schreiter, Pijnenborg and Aan Het Rot2013), but extend these findings by showing that these disturbances could possibly persist even after remission. Our findings of BPD as a predictor of higher personal distress and lower perspective-taking are also in accordance with previous results (Guttman and Laporte, Reference Guttman and Laporte2000; Dziobek et al., Reference Dziobek, Preißler, Grozdanovic, Heuser, Heekeren and Roepke2011; New et al., Reference New, aan het Rot, Ripoll, Perez-Rodriguez, Lazarus, Zipursky, Weinstein, Koenigsberg, Hazlett, Goodman and Siever2012). However, we combined all three conditions, ELM, BPD, and MDD, in one study in order to take into account the close association between these conditions.

MDD is often characterized by an attentional focus on the self as part of a dysfunctional, self-regulatory cycle in which patients ruminate and lack the ability to disengage from unattainable goals (Mor et al., Reference Mor, Doane, Adam, Mineka, Zinbarg, Griffith, Craske, Waters and Nazarian2010). During empathic processes, such as when watching someone in a stressful situation, this attentional self-focus may cause depressed individuals to imagine how they would react themselves in such a situation, rather than focusing on the other's reaction (Schreiter et al., Reference Schreiter, Pijnenborg and Aan Het Rot2013). It is also conceivable that depressed patients show a blurred self-other distinction, which in certain situations may lead to emotional contagion, so that the other person's emotion, with which one resonates, might even be mistaken for one's own emotion (Singer and Klimecki, Reference Singer and Klimecki2014). Individuals with BPD show a different pattern of difficulties in controlling their attention: they show a focus on current distress and signals of threat and anger (Baer et al., Reference Baer, Peters, Eisenlohr-Moul, Geiger and Sauer2012), as well as emotional hyper-reactivity with respect to interpersonal situations (Sauer et al., Reference Sauer, Arens, Stopsack, Spitzer and Barnow2014). In the unfortunate combination with difficulties in emotional regulation which is often shown by patients with BPD in particular but also those with rMDD (Dittrich et al., Reference Dittrich, Bödeker, Kluczniok, Jaite, Hindi Attar, Führer, Herpertz, Brunner, Winter, Heinz, Roepke, Heim and Bermpohl2018a), personal distress levels may rise. This is relevant because personal distress may lead to social impairments and interpersonal problems due to unfavorable reactions, such as stress, withdrawal, and non-social behavior, to these emotional situations (Schreiter et al., Reference Schreiter, Pijnenborg and Aan Het Rot2013; Singer and Klimecki, Reference Singer and Klimecki2014).

These social impairments might be especially important in the close relationship between mother and child. Our study indicates that elevated personal distress seems to mediate the effects of BPD and rMDD on child psychopathology. A link between maternal personal distress (measured using the IRI) and child emotional and behavioral problems has been reported before (Psychogiou et al., Reference Psychogiou, Daley, Thompson and Sonuga-Barke2008). However, we provide first indications for an intergenerational, indirect effect leading from maternal BPD and rMDD via maternal personal distress to child psychopathology. Mothers with high personal distress might perceive their child's negative emotions as aversive and stressful, which might limit their flexibility for reacting to the child's distress and even lead to withdrawal and non-comforting, or aggressive reactions. Another explanation could lie in children's emotional development, which is normally facilitated by a maternal scaffolding of emotional expressions and modulation (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Michel and Teti2018). When mothers show intense emotional reactions to their child's emotional expressions, the child may experience less dyadic co-regulation of emotions which might impair the acquisition of valuable emotional regulation strategies.

While personal distress relates to a more ‘self-oriented’ aspect of affective empathy, empathic concern describes the ‘other-oriented’ reaction to others' misfortune, sometimes also referred to as compassion (Singer and Klimecki, Reference Singer and Klimecki2014). In accordance with previous research (Thoma et al., Reference Thoma, Zalewski, von Reventlow, Norra, Juckel and Daum2011; Derntl et al., Reference Derntl, Seidel, Schneider and Habel2012; New et al., Reference New, aan het Rot, Ripoll, Perez-Rodriguez, Lazarus, Zipursky, Weinstein, Koenigsberg, Hazlett, Goodman and Siever2012), no effects from rMDD and BPD on empathic concern emerged in our study. It is conceivable that individuals with rMDD and BPD can feel compassion toward others while experiencing high personal distress at the same time. However, future studies might explore whether high personal distress could cause people to refrain from actual helping behavior, as self-report instruments on empathy only measure compassionate feelings toward others but not the capacity to act upon them (Schreiter et al., Reference Schreiter, Pijnenborg and Aan Het Rot2013). Of interest, Wingenfeld et al. (Reference Wingenfeld, Duesenberg, Fleischer, Roepke, Dziobek, Otte and Wolf2018) found that only after psychosocial stress induction borderline patients showed significantly lower empathic concern, measured in a behavioral task, than the control group.

Interestingly, lower levels of perspective-taking emerged for women with BPD but not rMDD. Impaired capacity to reflect upon the mental states of others has been argued to be a key feature of BPD and the main cause of interpersonal problems in these patients (Fonagy and Bateman, Reference Fonagy and Bateman2008). Accordingly, most previous studies on cognitive empathy or perspective-taking in BPD found lower scores for these patients in trait and state (behavioral) measures (Harari et al., Reference Harari, Shamay-Tsoory, Ravid and Levkovitz2010; Dziobek et al., Reference Dziobek, Preißler, Grozdanovic, Heuser, Heekeren and Roepke2011; New et al., Reference New, aan het Rot, Ripoll, Perez-Rodriguez, Lazarus, Zipursky, Weinstein, Koenigsberg, Hazlett, Goodman and Siever2012). While other authors have reported lower levels of perspective-taking in acutely depressed patients (Wilbertz et al., Reference Wilbertz, Brakemeier, Zobel, Haerter and Schramm2010; Cusi et al., Reference Cusi, MacQueen, Spreng and McKinnon2011; Schreiter et al., Reference Schreiter, Pijnenborg and Aan Het Rot2013), no significant effects emerged in our study of patients with MDD in remission. Perspective-taking describes the cognitive ability to draw inferences about other people's intentions, thoughts, and beliefs, also referred to as the theory of mind (Singer and Klimecki, Reference Singer and Klimecki2014). Longitudinal studies have shown significant improvements in the theory of mind tasks for MDD patients after remission (review by Berecz et al., Reference Berecz, Tényi and Herold2016). However, mild forms of social cognitive deficits still appear to persist, even in a remitted state (Ladegaard et al., Reference Ladegaard, Videbech, Lysaker and Larsen2015). While these studies assessed state (behavioral) theory of mind measures, we applied a trait measure of cognitive empathy, which also reflects a subjective impression of the participant. It seems conceivable that patients with MDD in remission estimate their own current performance similarly to healthy controls, given their experience of former periods of acute depression that may have implied more severe, social-cognitive impairments.

In contrast to our findings on personal distress, we did not find that lower perspective-taking mediated the effects of BPD on child psychopathology. This result contradicts the findings of Psychogiou et al. (Reference Psychogiou, Daley, Thompson and Sonuga-Barke2008), who reported negative associations between maternal empathy and child conduct problems. However, as Psychogiou et al. assessed a community sample and collapsed two scales into one, the results are hardly comparable. Notably, in their study, personal distress similarly seemed to play a more important role for child psychopathology than perspective-taking, as personal distress showed significant correlations with more child behavior scales. One might question why the two aspects of empathy show different impacts on child psychopathology: while both scales have been related to deficits in social competence, heightened personal distress has also been related to emotional vulnerability and fearfulness (Davis, Reference Davis1983). Thus, as low perspective-taking represents a lack of certain cognitive skills which might otherwise be compensated, personal distress can lead to stressful emotional states followed by aversive reactions or withdrawal from the child, which in turn may negatively affect the close emotional bond between mother and child.

Finally, when controlling for BPD and MDD, we did not find effects from ELM on any of the empathy dimensions studied here. Other studies investigated specific effects of PTSD related to childhood trauma and reported effects on cognitive and affective empathy (Nazarov et al., Reference Nazarov, Frewen, Parlar, Oremus, Macqueen, Mckinnon and Lanius2014; Parlar et al., Reference Parlar, Frewen, Nazarov, Oremus, MacQueen, Lanius and McKinnon2014). Parlar et al. (Reference Parlar, Frewen, Nazarov, Oremus, MacQueen, Lanius and McKinnon2014) for example, reported lower levels of empathic concern and perspective-taking and higher levels of personal distress, using the IRI, in individuals with PTSD related to ELM. However, as they did not study the effects of ELM on empathy independently of PTSD, results are hard to compare. We controlled for mental disorders to estimate the isolated effect of ELM and have concluded that trait empathy deficits in adults with ELM seem to be provoked mainly by common sequelae such as MDD or BPD. Further research replicating this finding with state empathy tasks would be desirable.

Limitations

Several limitations of the present study may be considered. First, we used self-report measures of empathy, which require some level of self-reflection from the participants, instead of behavioral tasks. The two approaches might produce different results. For example, Schreiter et al. (Reference Schreiter, Pijnenborg and Aan Het Rot2013) in their review showed that impairments in cognitive empathy in MDD were more often observed when using objective rather than subjective measures. However, behavioral tasks are usually a state measure while the IRI instead captures the trait aspects of empathy, which might also explain the divergent results. Future studies would ideally incorporate both. Also, other factors than a psychiatric disorder that have not been considered in this study could contribute to empathy in mothers. Second, we only focused on mothers; it would appear desirable to investigate this issue also in fathers as they could be an equally important attachment figure for the child. Third, the total effects of our mediation model were not significant. While this was considered a prerequisite of mediation analyses in traditional approaches, more contemporary and more statistically powerful methods of mediation testing have disproven this assumption (Hayes, Reference Hayes2009). Fourth, in our study, the proportion of mothers with BPD was lower than the proportion of mothers with depression or a history of maltreatment. Fifth, Banzhaf et al. (Reference Banzhaf, Hoffmann, Kanske, Fan, Walter, Spengler, Schreiter, Singer and Bermpohl2018) found that perspective-taking deficits in MDD could be attributed to comorbid alexithymia, which we did not assess in our study. Sixth, recruitment by advertisement might have caused a selection bias of participants in our study. Seventh, we included children at elementary school age. It would be interesting to investigate whether the observed effects can already be found in younger children. Finally, as this is a cross-sectional study, no conclusions can be drawn about causal direction. Although the onset of the maternal risk factors lay in the past, the assessment of maternal empathy and child psychopathology was carried out at the same time-point. Therefore, the causal direction underlying the association between empathy and offspring psychopathology could not be established unambiguously. Also, a disposition toward high personal distress could function as a vulnerability factor for certain mental disorders and severe child behavioral problems could possibly impact on maternal well-being. Longitudinal research designs would be needed to identify causal directions or reveal possible, bi-directional relationships in this context.

We conclude that empathy impairments in mothers with rMDD and BPD may pose a risk for child psychopathology. Elevated personal distress in mothers with BPD and MDD but not lower perspective-taking in BPD was found to lead to higher levels of psychopathology in their children and may thus be an important aspect for explaining intergenerational effects in maternal psychopathology. In our study, ELM did not affect empathy when potentially co-occurring sequelae like MDD and BPD were taken into account. Intervention programs which address the attentional focus in empathic processes and promote emotion regulation, in order to lower personal distress in mothers diagnosed with BPD or MDD, may have a positive influence on the next generation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719001107

Author ORCIDs

Katja Dittrich, 0000-0001-6301-7035.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (Grant number: 01KR1207C) and the German Research Foundation (DFG) (Grant numbers: BE2611/2-1; LE560/5-1; RO3935/1-1; HE2426/5-1). We would like to thank all the women and children who participated in our study.

Conflict of interest

None.