Introduction

What are the social consequences of political contestation over territorial sovereignty? While there is a burgeoning literature on the correlates of territorial preferences within contested multinational democracies, relatively little research addresses the attitudinal consequences, broadly defined, of these sovereignty disputes. For example, there is a dearth of studies on how such disputes impact affective polarization, even though public debates over territorial status are often emotionally charged, personally important to at least a large plurality of the sub‐state populations in question, and can define a main cleavage of political competition.

In this article, we present and test several hypotheses on how affective polarization can be related to territorial or self‐determination disputes. We put forth a straightforward theoretical proposition, which is that territorial‐policy differences can be the basis of a social identity, and that negative out‐group (and positive in‐group) evaluations and stereotyping result from it. Following previous research, we categorize these attitudes as social or affective polarization (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019; Mason, Reference Mason2018). To assess such polarization, we employ a survey design that permits a clear measurement of stereotyping, a commonly used indicator of this polarization.

We use evidence from three regionally representative surveys concurrently fielded in autumn 2019 in Scotland, Catalonia and Northern Ireland. Each of these European substate regions has had distinct experiences with territorial contestation. The United Kingdom permitted an independence referendum in Scotland in 2014, which the independence campaign lost, though with a closer vote than expected. Following the Brexit referendum in June 2016, political momentum for a second referendum increased, against the UK government's wishes. The crisis in Spain posed by the Catalan independence movement is arguably the most serious sustained challenge to the central government since the democratic transition in the late 1970s. Unlike the United Kingdom in Scotland, the Spanish state has not permitted an independence referendum in Catalonia, and it repressed the two main referendum attempts by Catalan separatists in 2014 and 2017, imprisoning some of its political and social leadership. In Northern Ireland, a 30‐year armed conflict that resulted in over 3500 deaths had Irish unification as the key territorial issue. Since Brexit and the difficulties with the new customs barriers between Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom, this topic re‐surfaced as a political flashpoint, potentially jeopardizing the social stability that has held since the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

To the best of our knowledge, this paper presents the first comparative study examining the relationship between territorial preferences and affective polarization across different sub‐state regions. We find evidence that across all three regions, territorial preferences are associated with affective polarization in the form of positively stereotyping individuals with similar territorial preferences and negatively stereotyping those who differ. We interpret this as consistent with the notion that such policy preferences can be the basis of a social identity that has attitudinal consequences. We also document that individuals with intermediate territorial preferences stereotype far less than individuals with preferences at either extreme and that the highest magnitude of stereotyping is mostly positive affect for like‐minded individuals, particularly among supporters of territorial change. Finally, we report comparable levels of affective polarization in Scotland, Catalonia and Northern Ireland, despite the very distinct trajectories that the territorial contestation has taken across these regions.

We commence by outlining the related literature, elaborating on the theoretical underpinnings that guide our research design, and highlighting key events from the three cases under examination. Subsequently, we detail the research design, data, method and empirical findings across all three regions. The concluding section synthesizes the comparative evidence presented in the study, delving into its implications for future research.

Motivating literature

Our study is motivated by arguments and findings in two broad research literatures: the politics of self‐determination movements and affective partisan polarization, which have traditionally remained distinct from each other. On the one hand, ample literature in the fields of nationalism and secessionism examines cross‐regional or cross‐national variation in secessionist movements and their outcomes, providing evidence on the correlates of such movements (e.g., Hale, Reference Hale2008; Sorens, Reference Sorens2005). Moreover, a plethora of recent research examines the individual‐level correlates of territorial preferences, with an emphasis on secession, in different parts of the world (e.g., Bond & Rosie, Reference Bond and Rosie2010; Kelmendi & Pedraza, Reference Kelmendi and Pedraza2022; Liñeira & Cetrà, Reference Liñeira and Cetrà2015; Rodón & Guinjoan, Reference Rodón and Guinjoan2018).Footnote 1 Meanwhile, there is much documentation that violent ethnic and nationalist conflict is conducive to negative stereotypes leading to mistrust (e.g., Horowitz, Reference Horowitz1985, pp. 167−170), but there is significantly less research on socially consequential attitudes of non‐violent territorial disputes, in particular, whether and how preferences for territorial change or stability are linked to social division and affective polarization within contested territories. This omission is relevant because if affective polarization based on territorial preferences exists and is resilient; it could make both escalation into violence more likely and resolution of such conflicts more difficult.Footnote 2 Affective polarization could also be a factor in sustaining territorial disputes, since, once it is introduced, it becomes part of the problem to be resolved.

On the other hand, there is a burgeoning newer literature on affective polarization in democracies, which has overwhelmingly focused on affective partisan polarization (the positive or negative affect of co‐partisans for one another vs. members or leaders of various out‐parties).Footnote 3 Much of the evidence dwells on the rise in such affective polarization in the United States over the last 30 years (for reviews, see Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019; Mason, Reference Mason2018).Footnote 4 Beyond the United States, in looking at other cases of affective partisan polarization (Reiljan, Reference Reiljan2020; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018), much of this agenda has been about measuring and explaining its cross‐national variation, with key factors including non‐majoritarian electoral institutions that facilitate co‐governance; economic factors such as unemployment and inequality; elite focus on cultural and immigration issues (see Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, James and Horne2020 for discussion of all these factors); whether political divisions align with non‐political or social cleavages (Mason, Reference Mason2018)Footnote 5; and the role of specific parties such as populist right‐wing (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2021) or more extreme left‐wing parties (Orriols & León, Reference Orriols and León2020).

A corresponding stream of rese has examined how territorial identity is linked to affective polarization. Recent research with evidence from Spain focuses on affect (measured via feeling thermometers and trust) between members of different regions such as Andalusia, Madrid, Catalonia and the Basque Country. These findings indicate that media consumption, but not the emergence of extremist parties (Garmendia & Riera, Reference Garmendia and Riera2022), may affect this type of polarization, and that affect towards various territories correlates with vote choice (Albalate et al., Reference Albalate, Bel and Mazaira‐Font2023; Rodón, Reference Rodón2022). Other related studies use experimental trust games and show increased trust of co‐nationals (within Spanish or Catalan groups) and less trust of non‐co‐nationals, as a result of the conflict over independence in Catalonia (Criado et al., Reference Criado, Herreros, Miller and Ubeda2018; Martini & Torcal, Reference Martini and Torcal2019).

Less attention has been put on whether or how much polarization related to territorial preferences exists within contested regions, which is the focus of this study. One of the assumptions of previous research is that the territorial issue has driven affective polarization between citizens of different sub‐state territories (Albalate et al., Reference Albalate, Bel and Mazaira‐Font2023), which overlooks that there is considerable heterogeneity in territorial views within sub‐state territories. Simply put, while measuring the affect that people in territory A have for people in territory B is instructive, it has limitations if there is a wide distribution of territorial preferences within B.Footnote 6 We are interested in the distinct question of whether territorial preferences of those within territory B condition attitudes towards other citizens of territory B who may have different policy preferences. Understanding this polarization is normatively important as it can influence politics within contested territories and intergroup cooperation. Affective polarization is linked with lower levels of satisfaction with democracy (Wagner, Reference Wagner2021); it can lead to greater self‐sorting, such as in social interactions, employment and economic decisions (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019); and it can correspondingly reduce the policy space for negotiation. Iyengaret al. (Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019) argue, for example, that decreased levels of trust in the opposing party make accepting consensus and governing difficult.

Theoretical expectations

In territories where there is political discussion and open disagreement about potential border changes, individuals are likely to have preferences or views about such disputes; these are politically mobilized and constitute the basis of political cleavages. We argue that support of or opposition to a given territorial policy is a preference that can become a social identity, similar to other identities commonly thought to have strong personal importance and political implications. Following Hobolt et al. (Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021), a policy preference can be the basis of a political identity, akin to the creation of partisan identity, through creating a sense of groupness (Albalate et al., Reference Albalate, Bel and Mazaira‐Font2023; David & Bar‐Tal, Reference David and Bar‐Tal2009).Footnote 7 Such a sense of in‐group belonging comes not from simply sharing a policy preference but is further activated when the salience of an issue gives rise to inter‐group comparisons. This social identity can then become the basis for in‐group identification, differentiation from the out‐group and evaluative bias. Correspondingly, such identities can condition views or beliefs of other citizens. The formation of these identities can thus be the basis of social polarization in terms of positive or negative affect (see Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1974, for the classic account and Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021, for discussion).Footnote 8

We pose two non‐mutually exclusive reasons for these claims, rooted in prominent explications of social‐identity theory. First, territorial issues, which by definition involve a potential change in the sovereign status of a given territory, are frequently linked to ethnic or nationalist identities (e.g., Guinjoan, Reference Guinjoan2022; Loewen et al., Reference Loewen, Héroux‐Legault and Miguel2015; Sorens, Reference Sorens2005).Footnote 9 As a result, individuals on both sides of the cleavage are likely to have strong emotional connections to such preferences. Put otherwise, territorial disputes make salient issues of identity, national status, rights and belonging, which activate emotional identity attachments.Footnote 10

Second, territorial issues are likely to be perceived as more zero‐sum and irreversible than other first‐dimension issues where forms of political compromise are viewed as more realistic due to the possibility of division of a policy good. Compromise over territory is difficult because of the nature of goals such as secession. While there is a potential bargaining space, both secessionist and irredentist claims are prone to be viewed as indivisible as they are associated with notions of homeland (Shelef & Koo, Reference Shelef and Koo2022). Thus, overall, we expect territorial challenges (and the actions by both self‐determination movements and the states reacting to them) to either create or help solidify identities around territorial preferences and increase the salience of such identities. As a result, affective polarization around these social identities is likely to arise.Footnote 11

We present four broad expectations that follow from the above theoretical points. Our first baseline expectation is that territorial preferences themselves can be a basis of an identity and in‐group affect and out‐group animus, which can be theoretically distinct from other demographic‐oriented bases of group attachment. Concretely, pro‐ and anti‐territorial‐change individuals will have negative assessments of those with different territorial positions and positive assessments of those with the same territorial positions. The expectation is that, on average, supporters of a territorial position (whether it is pro‐ or anti‐change) will evaluate co‐supporters most favourably and opposers of their position least favourably.Footnote 12

Second, following from the previous point, our expectation is that, due to the aforementioned charged and perceived zero‐sum nature of territorial change, affective polarization between pro‐ and anti‐territorial‐change individuals will largely be similar regarding both positive and negative affect. That is, pro‐change individuals will have equal positive affect for like‐minded individuals and have similar‐sized negative affect for pro‐status quo individuals. We expect symmetrical effects for individuals who support the status quo.

Third, we expect that this affective polarization is most likely to be linked with individuals who hold positions at the poles of the territorial issue. We expect those with an intermediate territorial preference will be less likely to negatively evaluate others who have different preferences. One possible reason is that such individuals have weaker emotions on this issue.Footnote 13

Fourth, we expect higher levels of affective polarization in regions where there has been more violence historically or negation of territorial autonomy by the centre. Much empirical evidence documents the role of previous violence in hardening territorial views (e.g., Hadzic et al., Reference Hadzic, Carlson and Tavits2020; Rapp et al., Reference Rapp, Kijewski and Freitag2019) and as in many of those situations nationalist or ethnic identity aligns with such preferences, we expect this alignment and views to persist. Thus, our expectation is that levels of affective polarization based on territorial preferences would be lowest in Scotland, intermediate in Catalonia and highest in Northern Ireland. That is given the case of recent histories of these regions, discussed below.

Cases

Our cases are Scotland, Catalonia and Northern Ireland. The comparison is instructive, as the regions are similar in that they are three sub‐state territories within European multinational and democratic states where sub‐state parties compete for governance at the sub‐state level. Cleavages in all three regions are based on associated nationalities that have a longstanding historical basis, and, in each case, territorial issues have been made salient (independence in Scotland and Catalonia, united Ireland in Northern Ireland) and public support for a change in territorial borders has increased in recent years, though views on the issue are heterogeneous.

Yet, these three cases show contrasting treatments of the territorial issue, from legal referendum in Scotland to armed conflict in Northern Ireland, and have had very different recent histories in terms of the resolution of territorial contestations. In Scotland, a centrally permitted referendum on independence was held in 2014 (but failed), while the Brexit referendum in 2016 reopened the debate over Scottish independence. The Scottish National Party (SNP) leadership is currently committed to a second referendum (Hepburn et al., Reference Hepburn, Keating and McEwen2021) and had set a provisional date in 2023, though the United Kingdom Supreme Court ruled that any Scottish‐initiated referendum would have only advisory status. In Catalonia, the Spanish state has rebuffed all demands for an independence referendum in Catalonia, and the 2017 referendum was deemed illegal and repressed, with political and social leaders imprisoned (an attempted referendum in 2014 was also forbidden and its leaders were prosecuted). At the other extreme, Northern Ireland has the legacy of a 30‐year violent conflict over its constitutional status within the United Kingdom, which had been tentatively resolved in 1998 (with the Good Friday Agreement) but has had its territorial status again raised as a key issue by the 2016 Brexit referendum and the United Kingdom's subsequent departure from the EU. Low‐level violence and political brinksmanship over the possible unilateral cancellation of the agreed relations with the EU over Northern Ireland threatened stability; the issue was temporarily resolved with the passage of the ‘Windsor agreement’ but tensions could re‐emerge if the Northern Ireland Assembly vetoes EU legislation. In short, all three regions have experienced salient territorial debates but demonstrate a variety of political processes, ranging from territorial arrangements imposed by the central state (Brexit), authorized and unauthorized self‐determination referenda, to armed conflict.Footnote 14 We now provide more context for each of the three regions.

Scotland

In Scotland, support for independence in much of the late 20th century was low, between 20 per cent and 30 per cent (Keating & McEwen, Reference Keating, McEwen and Keating2017, p. 8). A combination of political factors (the rejection of the movement by the Thatcher government in the 1980s, a new devolved Scottish government in 1998 and the corresponding assumption of powers) and economic reasons (the advent of North Sea oil revenue, reactions to the major economic recession of 2008) led to both rising support for the SNP—which went from a minority government in the Scottish elections of 2007 to a majority government in the elections of 2011—and for Scottish independence. In 2012, the SNP called for a referendum on Scottish independence, even though at this stage support for independence was about 30 per cent (according to Scottish Social Attitudes surveys),Footnote 15 which was authorized by the Conservative UK government for 2014.

The independence referendum failed by 55.3 per cent to 44.7 per cent, on one of the highest turnouts of any British election (84.6 per cent). The SNP continued to argue for a second independence referendum, particularly following the results of the 2016 Brexit referendum, where a majority in Scotland voted to remain within the EU. Subsequently, survey (Scottish Social Attitudes) and experimental (Daniels & Kuo, Reference Daniels and Kuo2021) evidence has shown increases in support for independence.Footnote 16 Following the United Kingdom leaving the EU in 2020, the SNP had set a referendum for October 2023, but following the UK Supreme Court ruling of November 2022, this would need the consent of the UK government to be binding. Scotland illustrates a case of a constitutional or more consensual route to dealing with territorial challenges with a centrally authorized referendum. We view it as a least likely case of strong territory‐based polarization, with the lowest predicted levels of affective polarization.

Catalonia

Since the Spanish transition to democracy, there had been minority support for independence in Catalonia, being below 20 per cent until the 2010s.Footnote 17 A more popular option was for increased powers within Spain, particularly to bring to Catalonia the fiscal privileges enjoyed by the Basque Country and Navarra. While the definite causes of the increase in support for Catalan independence are contested, many argue that support rapidly grew after key events such as the 2008 economic recession, and, more acutely, the 2010 Spanish national court ruling that overturned parts of the new Catalan Statue of Autonomy, which had been approved in 2006 by the Spanish and Catalan Parliaments and voted for in a referendum in Catalonia.Footnote 18 Political parties in Catalonia began to cooperate to push for independence and held a ‘plebiscite’ on this issue in 2014. A coalition of political parties, Junts pel Sí (Together for Yes), unified around the single issue of independence, won the majority of the seats in the Catalan Parliament and later attempted to achieve independence by means of a unilateral referendum. This centrally unauthorized vote was held on 1 October 2017, amid a tense situation that resulted in the Spanish state deploying security forces against non‐violent protesters. The Catalan Parliament declared Catalonia independent of Spain on 27 October although with no operational effect, and the Spanish Senate quickly authorized the temporary suspension of Catalonia's autonomy, activating for the first time a Constitutional clause (Article 155) that allows the state to take control of a region if it ‘fails to fulfil the obligations imposed upon it by the Constitution.’ Through October, there were rallies both for and against the secessionist process, indicating the intense emotional division in Catalan society about this issue.

In the December 2017 regional elections, the plurality winner was Ciudadanos (Citizens), a young party founded (in 2006) in large part to oppose Catalan nationalism. However, the three pro‐independence parties, which obtained a total vote share of 48.5 per cent, secured another parliamentary majority and were able to form a new government. Various pro‐independence leaders and social activists were in exile since October 2017 while others were tried for sedition and/or rebellion by the Spanish Supreme Court and sentenced in October 2019; the latter were pardoned by President Pedro Sánchez in June 2021. Vox, a new far‐right Spanish nationalist party, substantially increased its support in 2018 with national support in the double‐digits; part of its success has been attributed to a backlash to Catalan secessionism.Footnote 19

Like Scotland, Catalonia is a case in which the independence movement has employed non‐violent tactics (Albalate et al., Reference Albalate, Bel and Mazaira‐Font2023). Yet, given this more turbulent recent history, with a unilateral (and unconstitutional) referendum and subsequent repression by the state (Balcells et al., Reference Balcells, Dorsey and Tellez2021), we expect affective polarization around the territorial issue to be higher than in Scotland.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland represents a more extreme case as divided religious and geographic polarization has been a feature of the political landscape, with a violent civil conflict (the ‘Troubles’), for which peaceful resolution remains tenuous. It is also distinct because the territorial claims are about unification with another country rather than independence. The armed conflict, which began in 1969, swiftly became a struggle over the status of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, with conflict between unionists/loyalists and nationalists/republicans. These differing stances over the territorial arrangements largely overlapped with the ethno‐religious cleavage within society (O'Leary, Reference O'Leary2019; O'Malley & Walsh, Reference O'Malley and Walsh2013). In turn, this cleavage was reinforced by the conflict, which increased polarization and solidified residential segregation (Doherty & Poole, Reference Doherty and Poole2002; Guelke, Reference Guelke2000).

The 1998 Good Friday (Belfast) Agreement that ended the conflict established a new relationship between Northern Ireland and both Great Britain and Ireland, along with various measures to establish political and social equality between the two ethno‐religious groups, such as the equal status of language, and provisions for cultural manifestations, such as parades (Blake, Reference Blake2019). However, many voters sought ethnonational parties that they considered to be the best placed to represent their interests, and such parties engaged in ethnic outbidding with more moderate parties, leading to a more extreme and politically polarized political landscape (Gormley‐Heenan & MacGinty, Reference Gormley‐Heenan and MacGinty2008).

In 2016, the vote for Brexit in Northern Ireland reinforced the main ethno‐religious cleavage that had conditioned the territorial dispute. A survey taken at the time indicated Unionists voted 66 per cent to leave the European Union, while the nationalists voted 88 per cent to remain (Garry, Reference Garry2016). To achieve a Brexit deal, the UK government agreed to the Northern Ireland Protocol, which creates a customs union with the rest of Ireland (and thus the EU); this generated a trading border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom, which Unionists consider constitutionally and economically detrimental (Murphy, Reference Murphy2021). Polls show that support for united Ireland has increased, especially recently, for example, from 32 per cent in 2019 to 42 per cent in 2021 (Young, Reference Young2021).Footnote 20 Threats of governmental stalemate and even violence have also increased among Unionists, angry at the loss of their position within the United Kingdom (Hirst, Reference Hirst2021). The territorial issue, therefore, has recovered its salience following Brexit.

Among the three regions, Northern Ireland is the most obvious likely case for contemporary affective polarization based on territorial preferences, given the historical violent conflict (Bryan & Gillespie, Reference Bryan, Gillespie, Fox, Cronin and Conchubhair2020) and that the main ethno‐religious cleavage has a longer history of overlapping with territorial preferences. We thus expect the levels of affective polarization in Northern Ireland to be the highest among the three regions considered in this study.

Empirical approach

Data

To test our expectations regarding affective polarization related to territorial preferences, we fielded concurrently original surveys in Scotland, Catalonia and Northern Ireland from 20 September to 10 October 2019.Footnote 21 The online surveys were administered by the survey firm Respondi (now Bilendi & Respondi) with a regionally representative sample of 1650 individuals in Scotland, 1683 in Catalonia and 796 in Northern Ireland (all stratified by gender and age categories, plus Catholic or Protestant religious background in Northern Ireland).Footnote 22

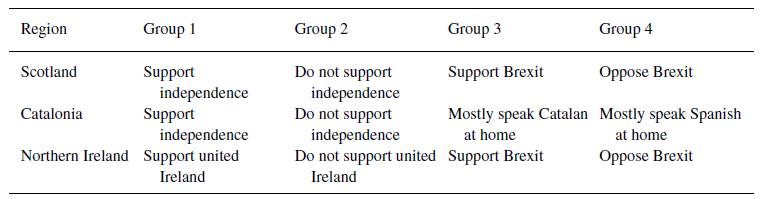

We assess affective polarization by examining how respondents stereotype individuals with specific territorial preferences. We randomly assigned respondents with equal probability to evaluate one of four possible groups: two groups on territorial preferences – either for or against independence (or unification with Ireland, in the case of Northern Ireland) – and two other groups chosen to benchmark our results and permit comparison of stereotyping.Footnote 23 In the UK cases, given the salience of Brexit and building on recent findings about the rapid increase in polarization due to Brexit (Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021), we use evaluations of groups with Brexit preferences as a comparison (i.e., evaluating people who are either pro or anti‐Brexit).Footnote 24 In the Catalan case, we use evaluations of different national/language groups (i.e., Spanish‐speaking or Catalan‐speaking individuals) as a benchmark.Footnote 25 The groups are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Groups to be evaluated in each region

A key aspect of the design is that each respondent was randomly assigned (with 0.25 probability) a different evaluation, yielding four groups of respondents. Each group of respondents was randomly assigned to evaluate one hypothetical group of individuals, for example, ‘pro‐independence people’ or ‘anti‐independence people’. This randomization into different groups to assess, while not a survey experiment in the narrow sense of randomly assigning a treatment, masks the intent of the design, addresses problems of survey acquiescence and possible social desirability bias and prevents potential fatigue from addressing repetitive questions.Footnote 26 The design allows for a precise comparison and assessment of stereotypes associated with different groups.

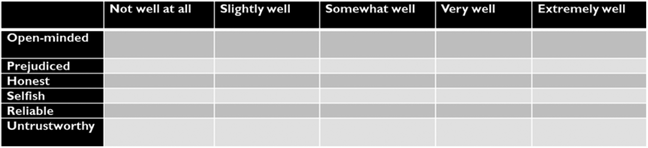

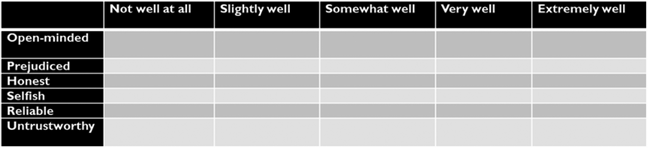

To measure our main dependent variable, we ask respondents to describe how well various positive and negative traits describe people in their allocated group.Footnote 27 Figure 1 shows the list of traits and the response options they had (respondents could choose only one option for each of the traits).

Figure 1. Array response to questions on traits.

We then created a standard index to measure stereotyping. We recoded the responses as binary variables, with the two categories ‘Very well’ and ‘Extremely well’ coded as one and the remaining options coded as zero. The index value subtracts the negative evaluations (Prejudiced, Selfish and Untrustworthy) from the positive evaluations (Open‐minded, Honest and Reliable) and rescales the measure from 0 to 1, such that higher values indicate higher net positive stereotyping scores.Footnote 28 Thus, a 0.5 score means the respondent has a net neutral view of the hypothetical group. In our design, the quantity of interest is simply how much the net positive versus negative stereotyping of others varies according to the group being evaluated.

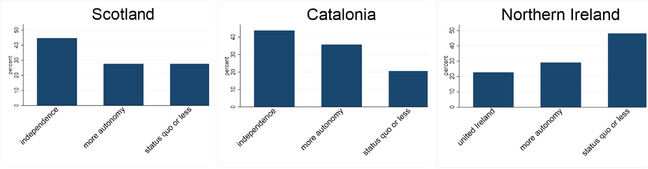

The core expectation is that territorial preferences will condition how respondents evaluate groups. Therefore, in each territory, we asked respondents (prior to the evaluation task) for their actual territorial preferences. Following previous literature, for Catalonia and Scotland, the response options were prefer [region] to be an independent state; that it should have more autonomy within the current state; that the status quo should be kept; or that [region] should have less autonomy. In Northern Ireland, the response options were the same, except the first option was that they prefer unification with Ireland. We recoded to consider three broad categories: (1) ‘Prefer independence’ (‘Prefer united Ireland’ in Northern Ireland), (2) ‘More autonomy (but not independence)’ and (3) ‘Status quo/less autonomy’. This tripartite coding is the most straightforward indicator of territorial preferences, which we use as the key moderator in our subsequent analyses.Footnote 29 Figure 2 displays the distribution of territorial preferences across the regions.

Figure 2. Territorial preferences in each region. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

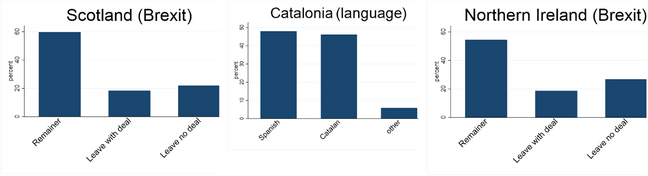

In Scotland and Northern Ireland, we also measure Brexit preferences.Footnote 30 In Catalonia, we measure the native language of the respondent, given the benchmark stereotype question we assess about language groups. The responses are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Respondents’ Brexit preferences in Scotland and Northern Ireland; respondents’ language use in Catalonia. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

We conduct the analyses with sociodemographic controls, which we select based on the aforementioned literature on preferences for secession at the individual level. We measure female gender (coded as 1 for female, 0 otherwise); age (three categories of 18–34, 35–54, 55+), education (lower secondary, upper secondary, vocational training and university studies or more), unemployment status (1 if unemployed, 0 otherwise) and income quartiles. In Catalonia and Scotland, we measure family background with indicators for whether the respondent and/or their parents were born in that region. In Northern Ireland, we also measure religious background into three categories by coding whether respondents consider themselves Protestant, Catholic or another/no religion.

Results

We analyse how individuals who have different territorial views vary in their assessments of the different groups. We present predicted stereotype scores by regressing the net stereotype score (scaled 0–1) on “evaluation assignment” and territorial preference and showing the plotted result of the interaction coefficient of these two variables. This allows us to assess whether individuals with contrasting territorial preferences evaluate the different groups distinctly, and how much they stereotype them. For all regions, our core specification is an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression in which we also control for all demographic control variables as noted above (we also conduct the analyses without controls). We present results for the theoretically relevant trichotomous coding of pro‐maximum territorial change, pro‐status quo and pro‐more autonomy supporters (as noted above, we use a dichotomous sub‐setting in Northern Ireland due to sample size). We proceed by discussing separately the results for Scotland, Catalonia and Northern Ireland. For brevity, we describe the figures and note that additional details from the OLS estimation models are depicted in Supporting Information (SI) Tables C1–C3.Footnote 31

Scotland

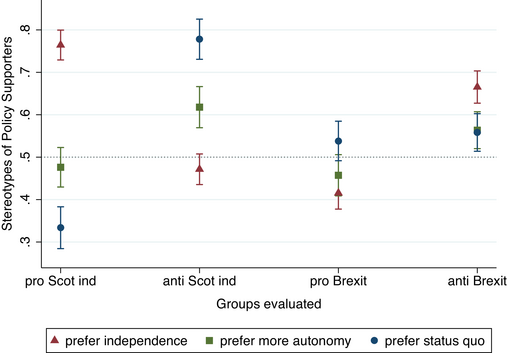

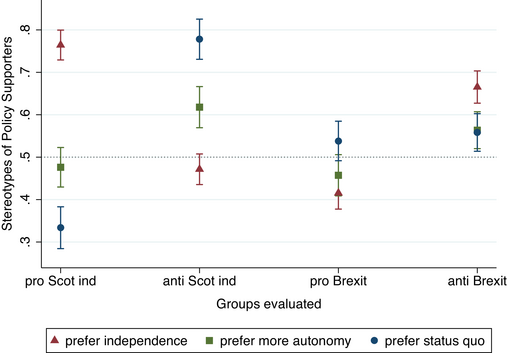

Figure 4 shows the differences in group stereotyping, by trichotomous Scottish territorial preferences.Footnote 32 For all figures, the different columns correspond to the randomly assigned group evaluated, and the different shaped dots correspond to the respondent's territorial preference. For example, the left‐most plot is how respondents evaluated people who are pro‐Scottish independence, and the high triangle is the score given by pro‐Scottish independence respondents.

Figure 4. Stereotyping by trichotomous territorial position, Scotland. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 4 shows considerable polarization (measured by stereotype evaluation) by territorial preference; this is indicated by the differences among markers of the same shape across different columns. First, consider those respondents who support independence and their stereotype evaluations of people with different Scottish territorial views, indicated by the triangles in the two left‐most columns: pro‐independence respondents rate fellow independence supporters very positively (the high 0.76 in the left‐most column), and rate those opposed to independence less positively (0.47, just shy of the neutral mark of 0.50, in the second column). Now, consider individuals who are pro‐status quo, the dots in the two left columns: they rate like‐minded anti‐independence supporters positively at 0.78 (second column), but rate individuals who support independence negatively (0.33, first column). Thus, we find, first, strong evidence that polarization is present, and, second, that the gap in stereotype scores (the relative evaluation of different groups) is similar for both pro‐independence and pro‐status quo individuals. We also note that pro‐independence supporters are somewhat less negative about their out‐group (they evaluate anti‐independence supporters at around 0.48) compared to pro‐status quo supporters (they evaluate pro‐independence supporters at 0.33).

There is a sizeable group of individuals who do not support the territorial status quo but do not prefer independence, but rather, more autonomy; these are so‐called moderates on the territorial dimension, and we hypothesized that they may exhibit distinct affect. Figure 4 shows that moderates are indeed the most reluctant to stereotype others, regardless of territorial position. For all groups evaluated, such moderates (denoted by the squares) have consistently predicted stereotype scores of around the neutral point of 0.50 (though they evaluate anti‐independence individuals at a slightly higher score of 0.62). These results contrast with the more extreme values of the pro‐independence and pro‐status quo individuals. Overall, this suggests that affective polarization is more driven by the ends of the territorial‐preference distribution.

Columns 3 and 4 display the results of the benchmarking analyses, with preferences over Brexit. We note that pro‐Scottish independence individuals are likely to evaluate pro‐Brexit (Leaver) individuals (0.42, third column) more negatively than they do anti‐Brexit (Remainer) individuals (0.67, fourth column). Pro‐territorial status quo individuals also have a similar set of evaluations; they evaluate Leaver individuals a little more negatively than Remainer individuals (0.54 vs. 0.56). Interestingly, then, regardless of Scottish territorial preference, Leavers are evaluated worse.

We note, critically, that the stereotype gap (the gap between the triangles and dots within each column) is far smaller in the Brexit evaluation conditions than in the pro‐ versus anti‐independence evaluation conditions. This suggests that the territorial cleavage does not fully overlap with a Brexit cleavage, at least in terms of stereotyping; this seems to be because pro‐territorial status quo Scottish respondents do not greatly differ in their stereotyping of Leavers versus Remainers. For pro‐independence Scottish respondents, they evaluate like‐minded Scots on independence more positively than they evaluate anti‐independence Scots, but they also evaluate Remainers more positively than Leavers.Footnote 33

Catalonia

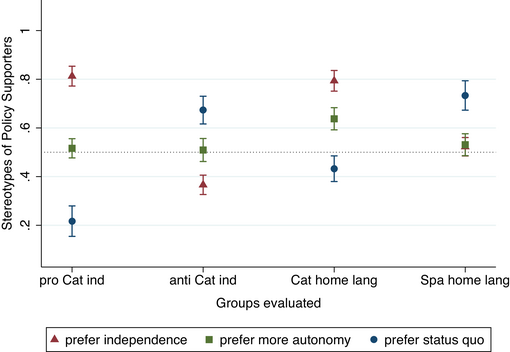

We find remarkably similar levels of territorial‐preference‐based affective polarization in Catalonia, displayed in Figure 5.Footnote 34 The graph shows that sub‐state polarization by territorial preferences is large; again, this is noted in the gaps among the markers of the same shape across the first two columns. As in Scotland, pro‐Catalan independence individuals (triangles) have high positive ratings of pro‐independence supporters (0.81, first column) and low ratings for anti‐independence supporters (0.36, second column). There is a similar stereotyping pattern for pro‐status quo respondents (dots). Their average rating is 0.67 of the like‐minded pro‐status quo group (second column) and a score of 0.22 in evaluating the opposing pro‐independence group (first column). In both regions, thus far, pro‐status quo individuals rate the pro‐independence people the lowest and pro‐independence individuals exhibit consistently very high ratings of like‐minded individuals. As in Scotland, we find that individuals who are territorial moderates (squares) have an intermediate stereotyping score; most scores hover around 0.5, which suggests that they are averse to stereotyping people based on their territorial positions.Footnote 35

Figure 5. Stereotyping by trichotomous territorial position, Catalonia. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

As discussed above, we are interested in the degree to which the stereotyping based on territorial preferences in Catalonia may differ from that of different language/national groups that could serve as natural benchmarks. While language spoken at home is not a deterministic marker of national identity (and there are many multi‐lingual households in Catalonia), much empirical evidence indicates a correlation between language and national identity; Catalan‐speaking people are more likely to identify nationally as Catalans (Guinjoan, Reference Guinjoan2022; Rodón & Guinjoan, Reference Rodón and Guinjoan2018). The latter two columns of Figure 5 present the predicted stereotype scores of pro‐ and anti‐independence individuals evaluating people who speak Spanish or Catalan at home. Pro‐independence individuals evaluate Catalan speakers (0.79, third column) more positively than they evaluate Spanish speakers (0.52, fourth column; this is a near‐neutral score). Those who are pro‐status quo evaluate Spanish speakers highly (0.72, fourth column) and Catalan speakers much lower (0.43, third column; this is a negative score). Overall, then, while both pro‐independence and pro‐status quo individuals seem more likely to positively stereotype Catalan and Spanish speakers, respectively, there is less stereotyping of the ‘opposing’ language groups than of groups with rival territorial views.Footnote 36

Northern Ireland

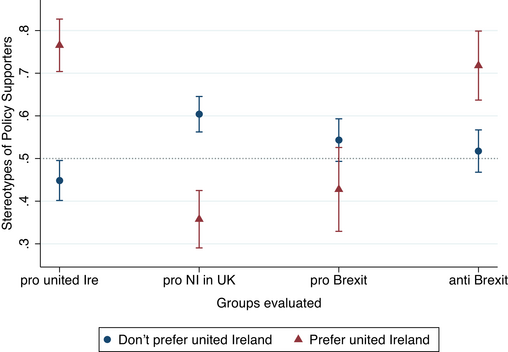

Figure 6 displays the predicted stereotype evaluations in Northern Ireland, where the territorial preference is a dichotomous measure of support or opposition for a united Ireland.Footnote 37 When examining the triangles across the first two columns, those who support a united Ireland positively evaluate those who share those preferences at 0.75 (first column) and those who oppose united Ireland at 0.35 (second column). Those who oppose united Ireland (dots) negatively evaluate those with different territorial preferences at 0.45 (first column) and positively evaluate those with the same territorial preferences at 0.60 (second column); thus this gap in stereotyping among anti‐united Ireland individuals is lower. As with Scotland, given the salience and divides caused by Brexit, we also examine whether territorial preferences condition evaluations of Brexit views. The correlation between supporting Brexit and Britishness is particularly strong in Northern Ireland, where 66 per cent of unionists voted to leave the EU and where the nationalist parties campaigned for remain (McCann & Hainsworth, Reference McCann and Hainsworth2017). The latter two columns of Figure 6 show that those who support a united Ireland exhibit more negative stereotype evaluations of Leavers (third column) than they do of Remainers (fourth column). But as with Scotland, this evaluation gap is smaller than that of their evaluations on the territorial dimension (and the magnitudes are less precisely estimated). We note that those who do not support a united Ireland do not differ much in their stereotype scores of Remainers versus Leavers.Footnote 38

Figure 6. Stereotyping by dichotomous territorial position, Northern Ireland. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

To summarize, across all three regions, we find confirmation of our first expectation that territory preferences are linked to affective polarization. In all cases, a consistent result is very high evaluations by pro‐territorial change respondents of like‐minded individuals, and corresponding low evaluations for individuals with different territorial preferences. We observe a similar pattern for respondents who oppose territorial change, but not among moderates who support more autonomy for the region within the existing country. Moreover, in the UK regions, we find that respondents’ territorial‐change positions also condition stereotype‐based polarization on another key issue, Brexit, although to a lesser degree. In Catalonia, we find some positive language‐based stereotyping. Yet, in all cases, the polarization on the non‐territorial category of comparison is of a smaller magnitude than the evaluations on the basis of territorial views, suggesting that territorial preferences can constitute salient social identities with relevant consequences for social affect.

In Scotland and Catalonia, we have sufficient power to disaggregate the respondents’ territorial positions into a more nuanced set of three options. This allows us to assess that polarization is more associated with individuals who place themselves at the poles of the territorial issue, both for and against territorial change, as per our third expectation. While we expected this polarization to be symmetrical across respondents who are pro‐ or anti‐independence (our second expectation), we find that the effect is more strongly driven by the positive evaluation by the pro‐independence respondents for like‐minded individuals and the negative evaluation that anti‐independence respondents have of the pro‐independence group. In other words, polarization is most driven by both the positive and negative evaluations towards pro‐independence individuals. We speculate that since pro‐independence (unification) individuals are the ones advocating for a challenging and transformative political choice, territorial change, they attract the strongest reactions.

Finally, our fourth expectation was that the different histories of these three sub‐state regions around the territorial issue – ranging from a legal/agreed referendum (in Scotland) to over 30 years of violent conflict (in Northern Ireland) – would condition affective polarization. However, we find that the levels and degree of affective polarization around territorial preferences are similar across the three cases. We discuss this unexpected finding further in the conclusion.

Conclusions

While there has been substantial research on the causes of self‐determination movements and individual territorial preferences, there is little research on the attitudinal or social consequences of such preferences and disputes, particularly when they are not violent. This is surprising given the amount of public discussion on this topic and observations (e.g., in the media) of serious disagreements within families or social networks due to debates about territorial politics. The absence of research on this matter is also somewhat disconcerting given that social polarization can contribute to the entrenchment and escalation of conflicts.

In this article, we examine three cases in Western Europe where sub‐state territorial conflicts are salient and analyse the relationship between such territorial disputes and affective polarization. We argue that territorial preferences can be the basis of group identity, akin to other commonly theorized ethnic or nationalist groups and can be linked to affective polarization. Our analysis is, to our knowledge, the first comparative study of this argument across different sub‐state regions, and we draw on contemporaneous survey data. The results show evidence of positive stereotyping of individuals with similar territorial preferences and negative stereotyping of those with differing preferences. Stronger stereotyping is driven by individuals with more extreme territorial preferences. Contra to one of our expectations, we find a striking similarity in social polarization across these regions, despite very different histories of bargaining and conflict with their states, suggesting that there are diverging channels by which affective polarization can emerge. Of course, such polarization can be at the origin of the territorial disputes or further escalate them, which is why we do not claim causality in our findings. Yet, the fact that social polarization is similar across regions with distinct histories suggests that it can emerge regardless of the strategies that government and non‐governmental actors use to either challenge or defend the territorial status quo. While previous literature has indicated that violence is more likely to crystallize polarized identities, our findings indicate that non‐violent mobilization can also contribute to the formation or endurance of social identities and polarizing dynamics. Using a comparative approach allows for building on this inference, in contrast to relying solely on single‐case studies.

An avenue of further research is to study other territories comparatively, including cases beyond Western Europe. We deliberately chose cases where territorial issues are already salient to allow for comparability across regions, but one could explore affective polarization in situations where the territorial issue is a less pronounced part of public discussion – such as Wales in the United Kingdom, Flanders in Belgium and Galicia in Spain. Moreover, further research could attempt to compare affective polarization around territorial issues (the object of this study) with affective polarization around political parties. Future surveys could include several measures allowing the comparability of these different forms of affective polarization and the assessment of how they relate.

Another potential area for investigation involves delving deeper into the relationship between reasons behind territorial preferences and positive or negative affect, as they may have implications for attitudinal, behavioural, and political aspects of territorial identity. When examining the varying reasons for preferences, individuals who articulate different rationales for a particular territorial outcome may exhibit differences in the intensity or strength of their attachment to this identity. For instance, an individual who favours independence for economic purposes, such as seeking increased regional income, may have a lower level of attachment to the social identity associated with independence compared to someone who supports independence for reasons less tied to economic benefits, such as safeguarding a minority culture. This can have consequences for their in‐group affect and out‐group animus. Similarly, those who defend the territorial status quo for economic reasons might exhibit different levels of affect than those who defend the status quo for purely nationalist motives.

Finally, the formation and ‘hardening' of these identities can have different polarization implications depending on whether territorial‐preference identities amplify existing cleavages or cross‐cut them. For example, Brexit issues have potentially increased support for Scottish independence and a referendum on Irish unification even among those who do not identify strongly as Scottish or Irish. In turn, this could have exacerbated affective polarization around these self‐determination issues. Similarly, for those with strong ethnic or nationalist attachments, the territorial preference identity is likely to overlap and reinforce such identities.

In conclusion, we aspire for this article to stimulate further scholarship in the measurement of the social consequences of territorial debates and disputes in multinational states, with greater attention to the effects of identity activation and the creation and/or solidification of social identities. It is our hope that these findings shed light on certain micro‐level dynamics and enhance our comprehension of the potential escalation or resolution of such political disputes.

Acknowledgements

We thank José Fernández‐Albertos, Francesc Amat, participants in the 28th International Conference of Europeanists, Lisbon 2022, four anonymous reviewers, and attendees at the Center for Global Studies at the University of Illinois and at Urbana‐Champaign at the Hoover Institution at Stanford, for helpful feedback on previous versions and the project. We thank Sergi Martínez and Fernando Hortal for their research assistance. This work was supported by the Institut d'Estudis de l'Autogovern (Institute of Self‐Government Studies) (2017‐IEA5‐00014), the AXA Research Fund (2016‐SOC‐PDOC to L.A.D) and Georgetown University (Competitive Grant‐in‐Aid for ‘Sovereignty Conflicts in Western Europe’ to L.B.).

Data availability statement

The data associated with this study is available at the Harvard Dataverse, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FAWNPY

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supporting Information

Supporting Information