Introduction

‘Either you're with us, or you're against us.’

Conceptualised as a set of ideas emphasising that society is separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups – the ‘good’ ordinary people versus ‘the evil’ others (Mudde Reference Mudde2004), populist messages can be understood as a social identity frame (cf. Mols Reference Mols2012). In line with social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986), populist rhetoric frames issues as reflecting irreconcilable differences in norms, identities and interests while exaggerating intra‐group homogeneity and intergroup differences. Key to this populist identity frame is the subjective sense of in‐group deprivation it calls upon: while the political elite benefits from having the upper hand, the people are threatened (Elchardus & Spruyt Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2016; Taggart Reference Taggart2000).

Previous research has focused on the structural conditions on which this perceived sense of threat and injustice – manifested in, for instance, economic anxiety or cultural backlash (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017b) – is founded (Rooduijn & Burgoon Reference Rooduijn and Burgoon2018). Specific national (and personal) circumstances condition who feels threathened (Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2018), and also shape the discursive opportunity structure (Aalberg et al. Reference Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Strömbäck and De Vreese2017) and thus the substantive focus of the populist message (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017b; Van Kessel Reference Van Kessel2015) in various contexts. It is within these contexts that it has been shown that voters with stronger populist attitudes are more attracted to populist parties (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Rovira Kaltwasser and Andreadis2018; Oliver & Rahn Reference Oliver and Rahn2016), even when their policy preferences are not completely in line with those of a populist party (Van Hauwaert & Van Kessel Reference Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel2018). Most notably, voters that feel more vulnerable are more likely to be supportive of populism (Rico et al. Reference Rico, Guinjoan and Anduiza2017; Spruyt et al. Reference Spruyt, Keppens and Van Droogenbroeck2016). In fact, Spruyt et al. (Reference Spruyt, Keppens and Van Droogenbroeck2016: 344) argue that it is at this point that ‘psychological coping mechanisms among voters and the politicization of social conditions by parties meet’. In other words, populism not only addresses voters’ grievances, but reaches out to vulnerable voters by fostering a positive social identity, irrespective of the specific social context.

Even though recent research highlights social identity as a core component of populism (e.g., Busby et al. Reference Busby, Gubler and Hawkins2019; Meléndez & Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser2017; Spruyt et al. Reference Spruyt, Keppens and Van Droogenbroeck2016), studies investigating the psychological impact of this central aspect of populist rhetoric on citizens are lacking (but see Schulz et al. Reference Schulz, Wirth and Müller2018). To advance the field, this study provides a theoretical framework for understanding the consequences of populism as a social identity frame and tests this in a 15‐country experiment. Our theoretical framework uses social identity theory (SIT; Tajfel & Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986) and the social identity model of collective action (SIMCA; Van Zomeren et al. Reference Van Zomeren, Postmes and Spears2008) to lay out the observable implications of populist identity frames on the persuasion and mobilisation of citizens. To test our expectations, we draw on an extensive experiment conducted in 15 countries (N = 7,342). Specifically, the study explores the effects of populist identity framing of an economic issue on issue agreement and political engagement and investigates the extent to which these effects are dependent upon subjective vulnerability – that is, feelings of relative deprivation. In each country we conducted an identical online experiment in which we manipulated the presence and absence of two out‐groups – the political elite and immigrants – in contrast to the presence of the national in‐group (heartland), resulting in a 2 × 2 between‐subjects experiment, with a control group. Our results are in line with our expectations for anti‐elitist identity frames, but not for exclusionary cues. While anti‐elitist identity frames are persuasive and mobilising among the highly relatively deprived, exclusionist identify frames backfire, especially among those feeling less relatively deprived.

Theory

Populist communication as an identity frame

The central idea of populist communication emphasises a binary divide in society: The ‘good’ ordinary people are opposed to the ‘evil’ and ‘corrupt’ elites (e.g., Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017a; Jagers & Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007; Taggart Reference Taggart2000). In right‐wing populism, this core idea or ‘thin‐ideology’ (Mudde Reference Mudde2004) is supplemented by nativism, excluding societal out‐groups such as immigrants or refugees (Aalberg et al. Reference Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Strömbäck and De Vreese2017; Jagers & Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017a). This central populist message is not necessarily attached to one actor or communicator, but rather is a frame that can be adopted by different actors, such as politicians, journalists or citizens (Aalberg et al. Reference Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Strömbäck and De Vreese2017; Aslanidis Reference Aslanidis2016). Nor is populism regarded as a binary category, but rather as a matter of degree. Our approach to populist communication thus ties in with both the ideational and discursive approaches to populism (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2010; Laclau Reference Laclau2005; Mudde Reference Mudde2004). Finally, this central idea, or thin‐ideology, of populism is disseminated through different modes of communication, such as politicians’ self‐communication on social media, party manifestos, news media or citizens’ Facebook profiles (Ernst et al. Reference Ernst, Engesser, Büchel, Blassnig and Esser2017; Krämer Reference Krämer2014; Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, De Lange and Van Der Brug2014).

In this research, we specifically distinguish between two elements of populist communication (see Aalberg et al. (Reference Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Strömbäck and De Vreese2017) or Jagers and Walgrave (Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007) for similar approaches): anti‐elitism, anti‐immigration and a combination of the two. In line with recent research on the mechanisms underlying populist communication (e.g., Busby et al. Reference Busby, Gubler and Hawkins2019; Hameleers et al. Reference Hameleers, Bos and De Vreese2017) we can assume that blame‐shifting plays a central role. The in‐group of the ordinary people is described as suffering while at the same time being absolved of responsibility. The out‐groups, in contrast, are blamed for the problems that ordinary people experience.

This Manichaean outlook on society as divided between the ‘good’ people and the ‘evil’ others is reflected in literature on identity framing. In line with the premises of SIT, populist communication invites people to identify with the constructed in‐group and primes a consistent, positive image of the in‐group and of those choosing to identify and thus being a part of it (Tajfel & Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986). To reassure and consolidate this positive self‐identity, negative qualities or situations are attributed to the out‐group. The identification process underlying populist communication can be regarded as populist identity framing by combining the construction of in‐group favouritism and out‐group hostility (Mols Reference Mols2012; Tajfel & Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986).

The effects of populist in‐group cues on issue agreement

As explained above, the programmatic focus of populists is dependent upon the (national) context (Aalberg et al. Reference Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Strömbäck and De Vreese2017; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017b; Van Kessel 2015), and previous research has indicated that it is plausible that, within boundaries, vulnerable voters can be lured into agreement on various issues (Bos et al. Reference Bos, Lefevere, Thijssen and Sheets2017; Van Hauwaert & Van Kessel Reference Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel2018). These two factors combined raise the question whether a message with a populist identity frame persuades voters to side with the slant of the message. The in‐group/out‐group distinction that is fostered by populist communication increases the salience of shared group membership or in‐group identification and fuels out‐group derogation (Mols Reference Mols2012; Aalberg et al. Reference Aalberg, Esser, Reinemann, Strömbäck and De Vreese2017). Extant research shows that communications from reference groups with whom perceivers share group membership affect people's judgments (Asch Reference Asch1955; Sherif Reference Sherif1936). Specifically, when people are uncertain as to whether a given communication is valid, norms from a social group with which one identifies can be an important source of influence (Mackie & Queller Reference Mackie, Queller, Hogg and Terry2000; Tajfel & Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986). The in‐group of ‘the people’ is constructed by applying ‘norm talk’ (cf. Hogg & Giles Reference Hogg, Giles and Giles2012). The communicated group norms facilitate the construction of a shared worldview that is normative for the in‐group. In this sense, in‐group cues in communication have been shown to boost support for policy proposals (Cohen Reference Cohen2003). Additionally, strong in‐group identification and similarity among in‐group members increase the credibility and persuasiveness of in‐group sources of messages (Cohen Reference Cohen2003; Hogg & Reid Reference Hogg and Reid2006; Mackie & Queller Reference Mackie, Queller, Hogg and Terry2000).

In the context of populist communication, Hameleers and Schmuck (Reference Hameleers and Schmuck2017) show that messages blaming political elites are more persuasive among audience members who identify with the source of the message. As a consequence, in‐group recipients of populist messages blaming political elites or immigrants for societal crises may be more likely to agree with these messages, and may be more convinced that action is needed, than when they are exposed to messages depicting societal problems without any blaming of out‐groups (Hogg & Reid Reference Hogg and Reid2006; Mackie & Queller Reference Mackie, Queller, Hogg and Terry2000). Put differently, when populist actors point to societal problems the in‐group has to face and hold immigrants or elites responsible for these problems, then recipients who share the populist source's group‐membership should easily internalise this view and subsequently blame these out‐groups for the distress they experience (Hogg & Reid Reference Hogg and Reid2006). In‐group recipients are then more likely to agree with issue positions populist messages suggest. In this vein, out‐group derogation increases the effect of in‐group serving bias on persuasion.

Taken together, when populist actors bring up a specific problem and present themselves as the advocate of the people as an in‐group that is threatened by out‐groups, then this group categorisation can make in‐group recipients agree that a specific problem is real and needs to be addressed. In line with the premises of social identity framing, populism's cultivation of an in‐group threat combined with credible scapegoating should foster issue agreement (Gamson Reference Gamson1992). More specifically, in the face of threat, populist communication offers blame‐shifting cues that can consolidate a positive self‐concept. In line with the previous reasoning, it is hypothesised that anti‐elite cues in populist communication (the anti‐elitist identity frame H1a) and an anti‐immigrant or exclusionist identity frame (H1b) are more persuasive (i.e., produce more issue agreement) than the depiction of societal problems without any out‐group blame. In addition, the more extensive the threat from out‐groups the more relevant in‐group cohesion should become. Populist communication should accordingly be more persuasive when the threat comes from more than one out‐group as it likely appears to be more credible and eminent. We therefore hypothesise that the combination of anti‐immigrant and anti‐elitist cues (right‐wing populism) will result in the strongest in‐group threat and will produce even more issue agreement compared to single out‐group cues alone (H1c).

The mobilising effects of populist identity framing on readiness for (collective) action

Research in social psychology has not only shown that the internalisation of in‐group norms results in persuasion (e.g., Mackie & Queller Reference Mackie, Queller, Hogg and Terry2000), but social identity additionally serves to mobilise people for social change (e.g., Drury & Reicher Reference Drury and Reicher2000). SIMCA (Van Zomeren et al. Reference Van Zomeren, Postmes and Spears2008) posits that this is most notably the case when there is perceived injustice and when social identity is politicised. The populist identity frame does exactly that. By priming in‐group favourability and out‐group hostility, it constructs a severe threat to the people's in‐group status, which is likely to enhance a subjective sense of injustice among those who identify with this in‐group (e.g., Elchardus & Spruyt Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2016; Van Zomeren et al. Reference Van Zomeren, Postmes and Spears2008). Research in the field of identity framing has indicated that in‐group mobilisation results from priming a severe threat to the well‐being of the group (e.g., Postmes et al. Reference Postmes, Branscombe, Spears and Young1999; Van Zomeren et al. Reference Van Zomeren, Postmes and Spears2008), motivating the in‐group to take action (e.g., Simon & Klandermans Reference Simon and Klandermans2001). It is exactly this injustice that is central to the populist identity frame.

Even more fundamentally, populist political communication is likely to contribute to the formation of a ‘politicised’ identity of the ordinary people, that can then be referred to, activated or primed in future communication. By constructing a positive image of ordinary people, who are victimised by elites and/or immigrants (Jagers & Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007), populist political communication connects people based on their common plight of structural disadvantage (Van Zomeren et al. Reference Van Zomeren, Postmes and Spears2008) thus mobilising people ‘as self‐conscious group members in a power struggle’ (Simon & Klandermans Reference Simon and Klandermans2001: 319) and bringing ‘a subject called “the people” into being’ (Moffitt & Tormey Reference Moffitt and Tormey2014: 389). Being part of the politicised people enhances individuals’ motivation to engage in collective action due to a higher ‘inner obligation’ to participate in collective political activities (Van Zomeren et al. Reference Van Zomeren, Postmes and Spears2008). Prior research underpins this assumption by demonstrating that perceived in‐group threat due to negative media representations or discrimination results in support for affirmative action (e.g., Fujioka Reference Fujioka2005) and a desire for collective action (e.g., Saleem & Ramasubramanian Reference Saleem and Ramasubramanian2017).

Integrating populist communication and social identity framing, it can thus be hypothesised that populist identity framing mobilises the in‐group to engage in collective action. Exposure to populist identity framing may thus motivate people to act on behalf of their deprived in‐group – for example, by sharing information on that threat, or by discussing populist communication with people in their network. More specifically, we expect that collective action in response to a message increases when the people are portrayed as being deprived by the elites (anti‐elitist identity frame; H2a) or by immigrants (anti‐immigrant identity frame; H2b). When an anti‐immigration cue is combined with populism's core anti‐elitist message (right‐wing populism), the threat of in‐group deprivation is strongest because it results from two enemies. Therefore, we expect the strongest mobilising effects on collective action for combined cues (right‐wing populism; H2c).

Perceived relative deprivation as a moderator

Some citizens may be more susceptible to populist identity framing than others (Hameleers et al. Reference Hameleers, Bos and De Vreese2018b). To investigate who is more likely to be persuaded by the populist message we look into a growing body of research that points to different factors driving the success of populism (Elchardus & Spruyt Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2016; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006; Spruyt et al. Reference Spruyt, Keppens and Van Droogenbroeck2016).While populist attitudes and (congruent) issue positions explain why voters support populist parties, (e.g., Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Rovira Kaltwasser and Andreadis2018; Van Hauwaert & Van Kessel Reference Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel2018) to understand who is more attracted to the populist message we have to look at other factors. As noted above, not all populist voters are classic losers of globalisation (Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2018; but see Oesch Reference Oesch2008), but recent research has shown that feelings of economic, social and political vulnerability do play a key role (Gest et al. Reference Gest, Reny and Mayer2018; Rico et al. Reference Rico, Guinjoan and Anduiza2017; Spruyt et al. Reference Spruyt, Keppens and Van Droogenbroeck2016). Those voters that feel threatened, ‘having difficulties in finding a positive social identity’ (Spruyt et al. Reference Spruyt, Keppens and Van Droogenbroeck2016: 344), justified or not, are more likely to feel heard when they are addressed in a populist message.

In this regard, perceptions of relative deprivation can be regarded as one of the most central individual‐level differences that predict susceptibility to populism (Elchardus & Spruyt Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2016; Spruyt et al. Reference Spruyt, Keppens and Van Droogenbroeck2016). Perceptions of relative deprivation can be defined as the belief that the resources available in society are not distributed in a fair way (e.g., Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Meehan and Farquharson2010). Specifically, some groups in society are assumed to benefit more from collective resources than others (Elchardus & Spruyt Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2016). These perceptions of relative deprivation can be connected to the persuasiveness of populist identity framing, which constructs a divide between a favoured in‐group and a threatening out‐group (Mols Reference Mols2012). Relative deprivation specifically taps into sentiments of this out‐group threat. Because some groups are prioritised, the ‘ordinary people’ are left with less than they deserve. Perceived deprivation thus concretises and augments the in‐group threat.

When social groups perceive themselves as being disadvantaged with respect to the distribution of resources compared to out‐groups then inter‐group conflict is highly likely (Tajfel & Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986). The feeling of being disadvantaged or deprived will result in an increase of in‐group liking and out‐group hostility (Pettigrew et al. Reference Pettigrew, Christ, Wagner, Meertens, Van Dick and Zick2008). The derogation of an out‐group is enhanced when out‐group members are explicitly blamed for the alleged harm that the in‐group experiences. This polarisation of in‐group and out‐group is stronger for in‐group members who feel more deprived than others because these individuals psychologically benefit more from the in‐group serving bias of out‐group derogation (Tajfel & Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986). By emphasising that the in‐group is deprived of resources with respect to welfare benefits, housing or culture, populist actors increase the feeling of deprivation (Elchardus & Spruyt Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2016), which is likely to resonate most among those message recipients who really suffer from social deprivation, such as the unemployed and/or welfare recipients (for a similar argument, see Schemer Reference Schemer2012). In addition, people who feel more deprived compared to others are more persuaded if responsibility for a particular situation is placed outside of the individual (Spruyt et al. Reference Spruyt, Keppens and Van Droogenbroeck2016). By shifting blame onto others, populist communication facilitates the individual and in‐group related evasion of responsibility. Therefore, we argue that relative deprivation moderates the impact of anti‐elitist identity frames (H3a), anti‐immigrant identity frames (H3b) and the combined anti‐elitist and anti‐immigrant populist identity frames (H3c) on persuasion, such that this effect is stronger when relative deprivation is higher.

Relative deprivation may not only increase persuasion but can also enhance mobilisation in response to populist identity frames. Previous research suggests that group‐based comparisons most likely result in collective action when people feel deprived on behalf of a relevant reference group due to subjective experiences of unjust disadvantage (Smith & Ortiz Reference Smith, Ortiz, Walker and Smith2002; Van Zomeren et al. Reference Van Zomeren, Postmes and Spears2008). There is a conceptual link between group‐based comparisons and the inter‐group nature of collective action (Postmes et al. Reference Postmes, Branscombe, Spears and Young1999; Van Zomeren et al. Reference Van Zomeren, Postmes and Spears2008). Individuals who perceive group‐based inequality or deprivation may see collective action as the most effective way to ameliorate their situation (Kawakami & Dion Reference Kawakami and Dion1995) and are most likely to confront those responsible in order to redress this (Van Zomeren et al. Reference Van Zomeren, Postmes and Spears2008). More specifically, the subjective sense of injustice inherent to relative deprivation is likely to foster collective action based on the resulting need to improve a negative group identity and to decrease feelings of relative deprivation (Kawakami & Dion Reference Kawakami and Dion1995). People thus engage in collective action in an attempt to restore the perceived power imbalance between their own in‐group and the out‐group. Here, it should be noted that the means by which people engage do not necessarily require a substantial amount of financial or political resources. Social network sites, for example, empower people to engage without the investment of much financial resources (or time, for that matter), as does sharing their dissent with like‐minded others either on social media or face‐to‐face.

Taken together, prior perceptions of relative deprivation should resonate with populist identity frames, as these frames provide individuals with a cause for their deprivation: the elites and/or immigrants. In this context, those people who feel worse off than others should have the highest motivation to take action against those responsible (Kawakami & Dion Reference Kawakami and Dion1995). We therefore expect relative deprivation to moderate the mobilising effects of anti‐elitist identity frames (H4a), anti‐immigrant identity frames (H4b) and combined anti‐elitist and anti‐immigrant populist identity cues (H4c) such that this effect is stronger when relative deprivation is higher.

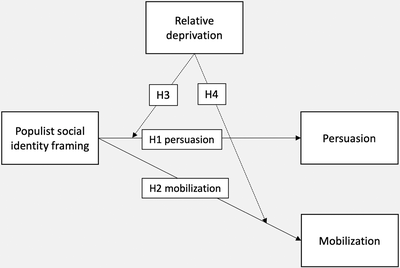

The conceptual model depicting the effect of populist identity framing on issue agreement (H1, persuasion) and collective action (H2, mobilisation) and the moderating role of relative deprivation is included in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual model.

Research design and method

The hypotheses derived above are tested within a multinational experiment. The value of such complex research designs is considerable. However, very few studies to date have offered such analyses (see, for exceptions, Busby et al. Reference Busby, Gubler and Hawkins2019; Hameleers, & Schmuck Reference Hameleers and Schmuck2017). Multi‐country experiments present an opportunity to estimate the stability or replicability of causal effects of a given stimulus against the background of varying political, social or cultural circumstances and in doing so ‘clarify their cross‐national travelling capacity’ (cf. Schmitt‐Beck Reference Schmitt‐Beck, Esser and Hanitzsch2012: 404). Moreover, these type of experiments also help improve our theoretical understanding of political media effects (Schmitt‐Beck Reference Schmitt‐Beck, Esser and Hanitzsch2012). For this study, the selection of countries was guided by the idea that populist movements and parties should be influential to varying degrees. This way, participants in the experiment are at least familiar with populist communication in public debate. The countries included in the research design also varied with respect to their social structure, political and media system, as well as their current economic situation and how they have recovered from the economic crisis in 2008. A replication of the effects of populist communication in different social‐cultural and economic contexts should bolster the generalisability of any populist communication effects we identify.

Experimental design

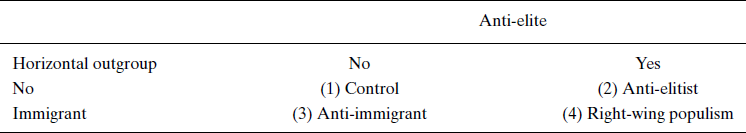

In all 15 countries, the design of the experiment was identical (Hameleers et al. Reference Hameleers2018a).Footnote 1 We vary the presence and absence of two out‐groups – the political elite and immigrants – in contrast to the presence of the national in‐group (heartland), resulting in a 2 × 2 between‐subjects experiment. In a control condition respondents were exposed to a factual story only, with no in‐group or out‐group present. The topic and source was held constant in all conditions and concerned the decreasing purchasing power for the nations’ citizens in the future of the respective country.

The stimuli and questionnaire were extensively pre‐tested using convenience samples in two countries, selected based on the variation of selection criteria. Based on the outcomes of two pilot studies in Germany (N = 264) and Greece (N = 1,565), the stimuli and questionnaire were further improved to increase their credibility irrespective of contextual differences between countries.

Sample

This experiment is based on a diverse sample of citizens in 15 countries: Austria (N = 566), France (N = 595), Germany (N = 501), Greece (N = 555), Ireland (N = 480), Israel (N = 507), Italy (N = 529), the Netherlands (N = 465), Norway (N = 503), Poland (N = 683), Romania (N = 750), Spain (N = 500), Sweden (N = 533), Switzerland (N = 566) and the United Kingdom (N = 553) (N Total = 8,286). The data were collected in the first months of 2017 by several research organisations,Footnote 2 which were instructed to apply the same procedures regarding recruiting, sampling, presentation of the survey and data collection. In each country, research organisations were instructed to employ quota sampling on age, education and gender so as to achieve a representative sample of the population. The complete dataset constitutes a diverse sample of European citizens with regards to age (M = 45.48, SD = 15.39), educationFootnote 3 (M = 2.21, SD = .72), political interestFootnote 4 (M = 4.62, SD = 1.73) and ideologyFootnote 5 (M = 5.12, SD = 2.57); 50.5 per cent of the participants were femaleFootnote 6 (for more information, see Hameleers et al. Reference Hameleers2018a). To clean the dataset we made use of four quality indicators: completion time, straightlining, item nonresponse and manipulation checks, removing 1,000 respondents from the dataset (see Online Appendix A for an extensive discussion of the data quality indicators). The removal of these respondents leads to more precise estimates, yet does not lead to substantively different results and conclusions (see Online Appendix E for the replicated results with the complete sample).

Procedure

All 15 experiments were conducted online. After giving their informed consent, participants filled out a pre‐test consisting of demographics, moderator variables and control variables. In the next step, participants were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions and read an online news item, which was visible for at least 20 seconds. A randomisation check shows that the four conditions do not differ significantly with regards to age (F 3, 8066 = 1.63, p = 0.18), gender (F 3, 8271 = 0.27, p = 0.85), education (F 3, 8245 = 0.12, p = 0.95), political interest (F 3, 8273 = 0.23, p = 0.88) and ideology (F 3, 7370 = 0.91, p = 0.44), indicating successful randomisation. Finally, participants had to complete a post‐test survey measuring the dependent variables and manipulation checks. Once completed, participants were debriefed and thanked for their cooperation. Participants received a financial incentive from the panel agencies.Footnote 7

Stimuli

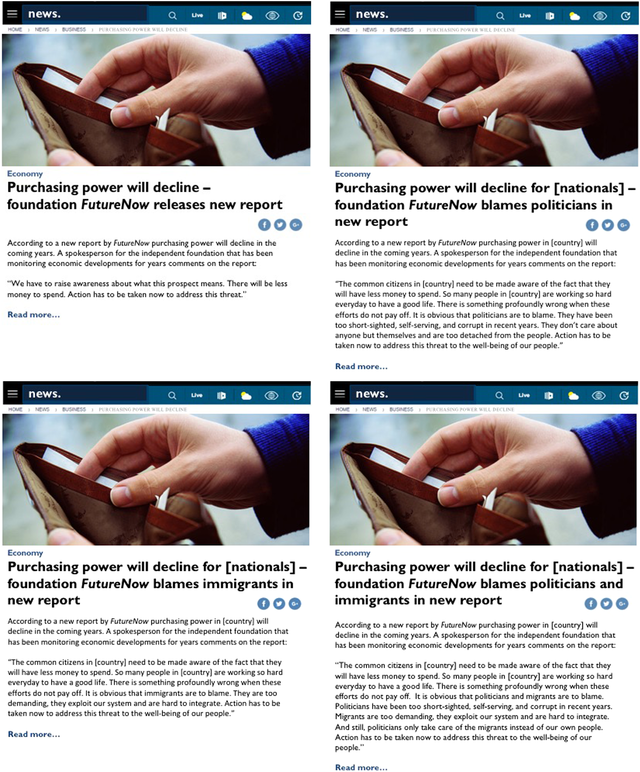

The questionnaire and stimulus materials were first developed in an English mother version. These templates were translated by native speakers in all countries. Inconsistencies and culture‐sensitive translations and meanings were exhaustively discussed with all country members until agreement was achieved. The basic stimulus material in all countries and conditions consisted of a news item on an online fictional news outlet called ‘news’. The layout of the stimuli was based on Euronews, as this is an equally familiar template in all countries. The post consisted of an image with a wallet and a hand, signifying the topic of purchasing power (see Figure 2 for the English mother version of the stimuli). In all conditions, a fictional foundation called ‘FutureNow’ was the source of the message.

Figure 2. Stimulus material (mother version).

Note: From left to right, top to bottom: Control condition, anti‐elite cue, anti‐immigrant cue, anti‐elite and anti‐immigrant cue. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

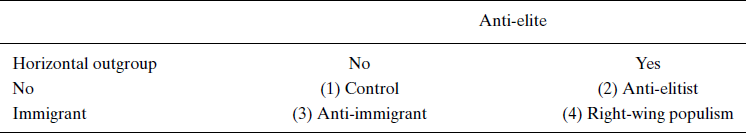

In the three treatment conditions, the typology of populist communication as outlined in the theoretical framework was manipulated. In all these conditions, the national in‐group was framed as a victim of the situation (see Table 1). In the anti‐elitist identity condition, the political elite was blamed for this situation, thus manipulating populism as a thin ideology emphasising that society is ultimately separated between the good people versus the corrupt political elite (Mudde Reference Mudde2004). In the anti‐immigrant identity condition, immigrants were blamed for taking away resources from the hardworking native people. The right‐wing populist condition differentiated the national in‐group from both out‐groups: the immigrants and the political elite were held responsible for the heartlands’ problems, while the latter were also blamed for representing the needs of migrants, instead of ‘their own people’. The treatments were compared to a control condition, which entailed a neutrally framed article on declining purchasing power, focusing on the facts and rational arguments of the story only: no out‐groups were blamed and the in‐group was not presented as a victim.

Table 1. Overview of the conditions

Measures

Persuasion

The first dependent variable – persuasion – was tapped after exposure to the stimulus and measured with two items, asking respondents to what extent they agreed with the following statements – ‘The economy will face a decline in the near future’ and ‘Policy changes need to be implemented in order to prevent the decline of purchasing power’ – on a scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree) (M = 5.11, SD = 1.37, α = 0.65).Footnote 8

Mobilisation

The second dependent variable – mobilisation– was measured afterwards relying on three items, tapping the willingness of the respondent to (1) share the news article on social network sites, (2) talk to a friend about the article and (3) sign an online petition to support the nongovernmental organisation mentioned in the article (seven‐point scale, running from 1 (very unwilling) to 7 (very willing)). A principal component analysis showed that all three items load on the same factor, with loadings varying from 0.827 to 0.888 (α = 0.829, M = 3.81, SD = 1.76).

Relative deprivation

Relative deprivation was measured before exposure to the stimulus using three items. Respondents were asked to what extent they agreed, on a scale from 1 to 7, with the following three statements: ‘If we need anything from the government, people like me always have to wait longer than others’, ‘I never received what I in fact deserved’, ‘It's always the other people who profit from all kinds of benefits’. A principal component analysis showed that all three items loaded on the same factor, with loadings varying from 0.852 to 0.869 (α = 0.827, M = 4.30, SD = 1.61).

Manipulation checks

After being exposed to the stimulus material and the post‐test measures, participants were subject to five manipulation checks. F‐tests indicate that the three manipulated conditions significantly differ from the control group with regard to the extent the story described (1) the people of the country as hardworking (F(1, 7165) = 687.21, p = .000), (2) a situation in which the national citizens will be affected by the economic developments described (F(1, 7184) = 69.05, p = 0.000) and (3) a threat to the well‐being of the people (F(1, 7186) = 151.89, p = 0.000). In addition, the anti‐elitist conditions differ significantly from the other conditions in the extent to which they ascribe responsibility for the purchasing power to politicians (F(1, 7179) = 1276.82, p = 0.000), and the anti‐immigrant conditions differ significantly from the other conditions in the extent to which they ascribe responsibility for the purchasing power to immigrants (F(1, 7173) = 2951.77, p = 0.000). Thus, these findings show that the manipulations were perceived as intended.

Analyses

Even though our dataset has a multilevel structure – holding observations in 15 different countries – the number of countries is too small to obtain unbiased estimates in a multilevel model (Stegmueller Reference Stegmueller2013). To test our hypotheses in all country samples simultaneously and control for the dependency of the observations, we therefore ran regression analyses with robust standard errors clustered by country. In addition, we added country dummies to control for country fixed effects.Footnote 9

Results

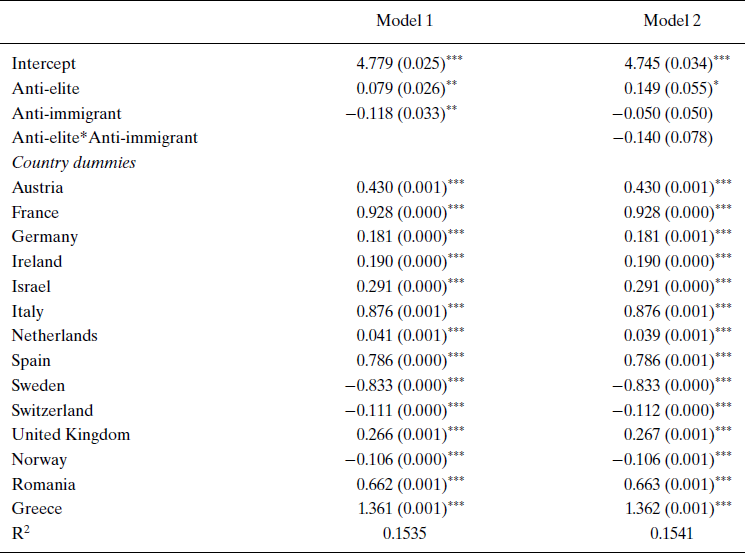

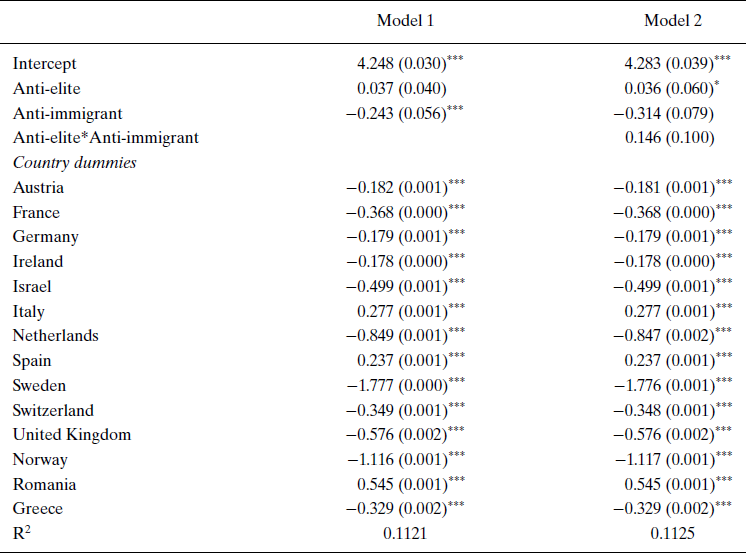

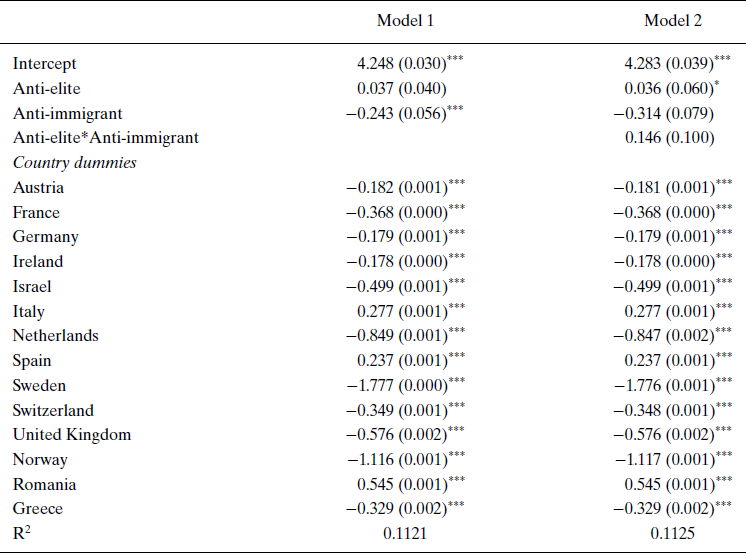

Model 1 in Table 2 tests H1a and H1b. First, the anti‐elitist identity frame indeed has persuasive effects: there is a small positive impact of this frame on agreement with the issue at hand. Exposure to the anti‐elitist identity frame (as opposed to exposure to the control condition) enhances agreement with the issue at hand with 0.079 on a seven‐point scale. The use of populist identity frames in news messages that blame the elite for a future loss in the peoples’ purchase power is more persuasive than news stories that come without these in‐ and outgroup cues. H1a thus finds support in our data. H1b – that the exclusionist identity frame would increase persuasion – is not supported by the present data. Specifically, news stories blaming immigrants for the peoples’ negative economic outlook actually have reverse effects. In other words, blaming immigrants persuades news recipients to side less with the slant of the news story as compared to the control condition: issue agreement decreases with 0.118 on a seven‐point scale. In the third model the combined impact of the populist identity frames is tested resulting in an insignificant negative interaction effect. H1b and H1c are therefore not supported.

Table 2. The impact of identity frames on persuasion

Notes: Linear regression analysis with robust standard errors clustered on the country level. Poland is the reference category. Clustered robust standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. n = 7,271.

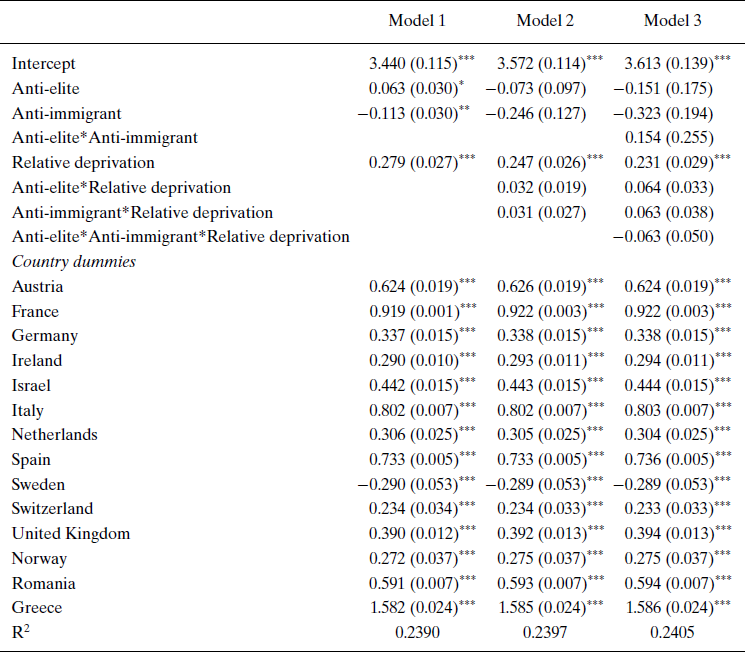

Table 3 runs the same analyses with political engagement as the dependent variable, studying the mobilising effects of both identity cues. Model 1 shows that the anti‐elitist identity frame does not affect mobilisation, contrary to H2a. Contrary to H2b, the findings demonstrate that again the anti‐immigrant identity frame has a negative impact, demobilising the respondents: exposure to the anti‐immigrant identity frame decreases mobilisation with 0.234 on a seven‐point scale. In the second model the combined impact of both frames is estimated, leading to a null result as well. Based on these results, H2a, H2b and H2c must be rejected: the anti‐elitist and the exclusionist identity frames do not have mobilising effects.

Table 3. The impact of identity frames on mobilisation

Notes: Linear regression analysis with robust standard errors clustered on the country level. Poland is the reference category. Clustered robust standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. n = 7,271.

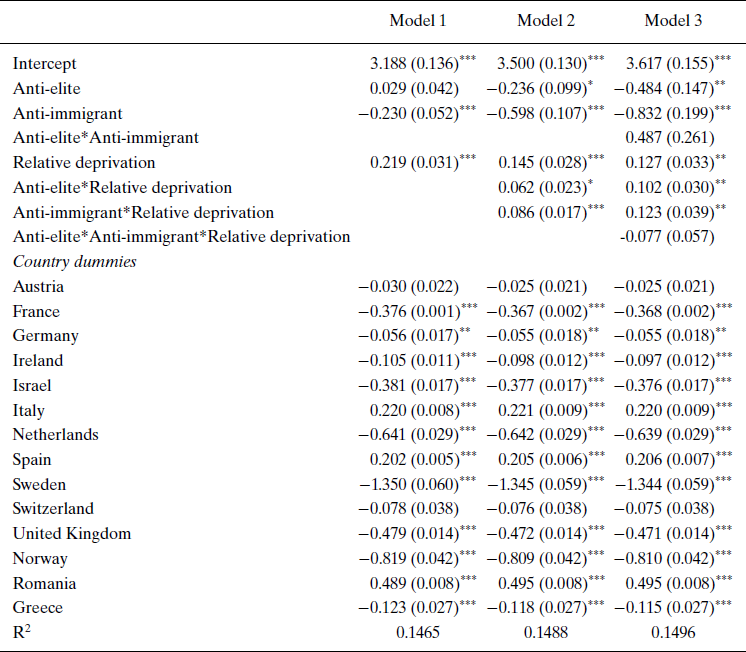

However, our theory not only predicts a direct effect of the identity frames on persuasion and mobilisation but also posits that relative deprivation conditions these effects. Table 4 tests these interactive effects. The coefficients of the interaction terms do not significantly differ from zero, comparing model 2 to the baseline of model 1, indicating that the single identity frames are not moderated by relative deprivation. The third model, finally, tests a possible three‐way interaction effect, estimating the conditional combined effect of both frames. This effect is non‐significant as well, indicating that the combined anti‐elite‐anti‐immigrant identity frame is not dependent on relative deprivation either. H3a, H3b and H3c thus find no support in our data: relative deprivation does not enhance the persuasive impact of populist identity frames.

Table 4. The impact of identity frames on persuasion, moderated by relative deprivation

Notes: Linear regression analysis with robust standard errors clustered on the country level. Poland is the reference category. Clustered robust standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. n = 7,203.

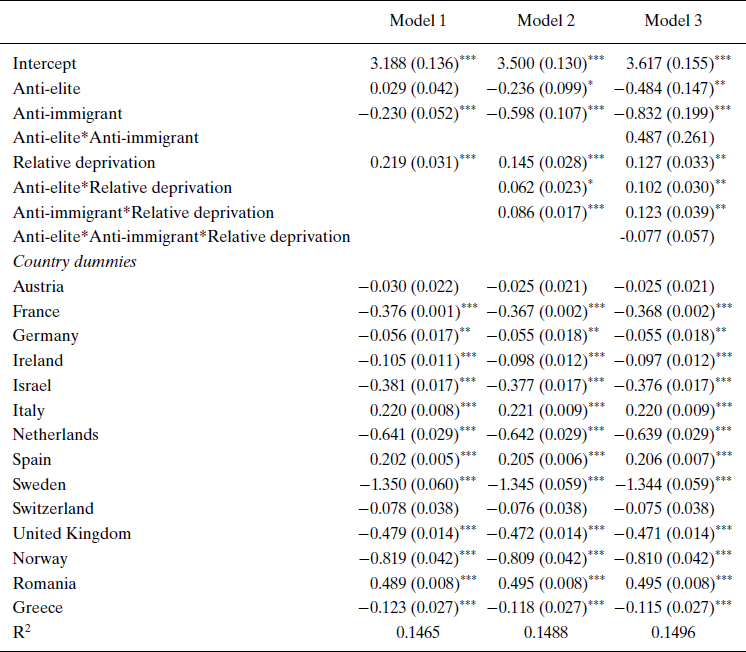

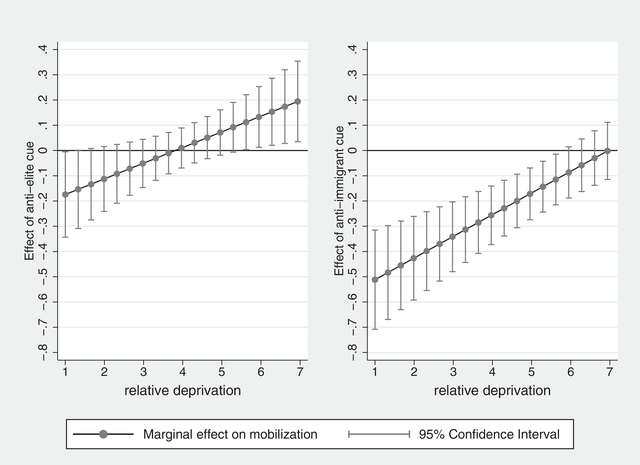

We ran the same analyses for mobilization. Model 2 in Table 5 shows that the impact of both the anti‐elitist frame as well as the anti‐immigrant frame is conditioned by relative deprivation. These effects are plotted in Figure 3. H4a and H4b are confirmed in our data: relative deprivation positively moderates the impact of both cues on political engagement. Only those that score higher on relative deprivation – in this case the 24.24 per cent in our sample scoring 5.67 and higher (on a scale from 1 to 7). These respondents see an increase in mobilisation from 0.112 to 0.194 after exposure to an anti‐elitist identity frame. Moreover, it demobilises the bottom 3.51 per cent: they are 0.174 less mobilised after exposure to the same message. The anti‐immigrant identity frame demobilises most respondents – they show a decrease of 0.115 to 0.512 points – but neither mobilises nor demobilises those 19.24 per cent of respondents who feel most deprived. Model 3 shows that the impact of the combined cues is not conditioned by relative deprivation.

Table 5. The impact of identity frames on mobilisation, moderated by relative deprivation

Notes: Linear regression analysis with robust standard errors clustered on the country level. Poland is the reference category. Clustered robust standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. n = 7,175.

Figure 3. Average marginal effect of populist identity frames on mobilisation for different levels of relative deprivation.

Discussion

The study of populism is, ultimately, the study of social identity. Engaging a rich tradition in social psychology built on social categorisation and identity, we identified a series of testable hypotheses. We test these hypotheses in one of the most extensive experiments on populism ever conducted involving a large collaborative network of researchers and taking into account 15 countries. Specifically, the present study examined the persuasive and mobilising consequences of two different populist identity frames, for more and less relatively deprived citizens. This research endeavour produced three major findings. First, anti‐elitist identity frames that blame the political elite for societal problems are persuasive and mobilising, the latter especially among people who feel more left out. Second, exclusionary cues backfire, especially among those feeling less relatively deprived, producing lower issue agreement and demobilising message recipients. Third, the combination of an anti‐elitist identity cue and an anti‐immigrant cue does not elicit stronger effects.

The findings demonstrate that the use of populist identity frames blaming the political elite for a negative economic outlook results in higher issue agreement as compared to the control condition. This finding is consistent with extant research on populist communication (Hameleers & Schmuck Reference Hameleers and Schmuck2017) and the persuasive impact of in‐group and out‐group cues (Hogg & Reid Reference Hogg and Reid2006; Mackie & Queller Reference Mackie, Queller, Hogg and Terry2000). Populist messages that depict societal problems as a threat to the in‐group caused by the political elite are more persuasive. Whether populists can lure vulnerable voters into agreement on any issue is an important question to be addressed in future research (Bos et al. Reference Bos, Lefevere, Thijssen and Sheets2017), but it has to be noted that recent research shows that this indeed might be the case (Van Hauwaert & Van Kessel Reference Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel2018). However, contextual‐level factors, such as socioeconomic circumstances (Rooduijn & Burgoon Reference Rooduijn and Burgoon2018), may not only provide more or less favourable opportunity structures to credibly assign blame to the elites and to cultivate an identity of ordinary people that are victimised (Hameleers et al. Reference Hameleers2018a), but also moderate the extent to which subjective perceptions of economic well‐being indeed play a role in the support of populism.

When it comes to mobilising individuals the results show that when people are exposed to anti‐elitist populist identity frames in a news story, mobilisation is increased among those who show high relative deprivation. This is in line with recent research (Marx & Nguyen Reference Marx and Nguyen2018) showing that individuals who feel highly deprived benefit more from blaming the elite because they are more vulnerable, given the bad economic situation and, consequently, they depend more on collective action to redress their disadvantage (Van Zomeren et al. Reference Van Zomeren, Postmes and Spears2008).

The quite strong negative impact of the anti‐immigrant populist identity frame on issue agreement and political engagement is inconsistent with our prior assumptions and, therefore, deserves a thorough discussion. We found consistent evidence that the anti‐immigrant cue in the news story reduced issue agreement and engagement (even more than the anti‐elite cue enhanced it). One explanation may be that news readers perceived the blaming of immigrants for a future loss in purchase power as too blatant and far‐off. As a consequence, they may have engaged in counter‐arguing and questioning the credibility of the article (Wegener & Petty Reference Wegener and Petty1997). If this was the case, it is unlikely to observe more persuasion for participants exposed to the anti‐immigrant cue. Another explanation would be socially desirable responding (Biernat & Crandall Reference Biernat, Crandall, Robinson, Shaver and Wrightsman1999): Maybe the presence of anti‐immigrant cues increased the tendency of participants to censor their true judgments. Even if they may have agreed with the slant of the news story, the over‐correction of their true judgments as a consequence of socially desirable responding would have produced less issue agreement when exposed to the anti‐immigrant cue, possibly because they perceive the message as ‘too populist’. Finally, these results raise questions regarding the distribution of findings among more and less tolerant subjects. One explanation could be that especially more tolerant voters are dissuaded and demobilised by exclusionist identity frames. Future research should look into this by testing whether exclusionist identity framing effects differ for respondents with different ideological profiles and immigrant attitudes.Footnote 10

While the use of an experimental design increased internal validity aiding us to assess the causal impact of our stimuli on the participants, we acknowledge the fact that an online survey experiment does not come without its shortcomings. First of all, low quality‐answers given by ‘professional’ respondents can distort the results. By flagging these respondents in the dataset, and running the analyses with and without them we feel confident that we have controlled for this problem. Second, one could argue that while an experiment increases internal validity, external validity is sacrificed by exposing respondents to a one‐shot, artificial, stimulus. In order to meet this problem, we minimised artificiality by conducting the experiment in an online (i.e., non‐laboratory) environment, and exposing respondents to a news item that resembled an online news story that may have appeared on a news site. Moreover, by running the experiment in 15 countries simultaneously, the study of the stability of the experimental effects was included in our design.

One could note that, as a consequence of pooling the experimental data from the 15 countries in our study, we end up with a large n of more than 7,000 cases, increasing power and hence the likelihood of finding significant results. The country results (presented in Online Appendix C) also show that even though individual country results mostly point in the same direction as the pooled results, they are less consistent,Footnote 11 most notably with regard to the pooled effects on persuasion. This indicates that, in general, the effects sizes are not large, as is common in media effects research. However, it must be noted that the results do show that even a marginal manipulation of words leads respondents to change their agreement with the issue under study and especially their likelihood to engage in political action, be it in a minimal way. This suggests that exposure to a multitude of populist messages could lead to much stronger effects, particularly among parts of the electorate that are susceptible to it.

Although the breadth of our multi‐country design is the strength of this article, it raises questions with regard to the contextual factors conditioning populist communication effects. One could postulate that the populist exclusionary frame might resonate more in countries with higher immigration or that the populist identity frame has more impact in countries with more inequality. In addition, some populist identity frames might be less credible in some national contexts, leading to backfire effects (Müller et al. Reference Müller, Schemer, Wettstein, Schulz, Wirz, Engesser and Wirth2017). However, since the 15 countries in our dataset differ in various respects, it is impossible to reliably establish to which contextual factor differential effects can be attributed. We call on future research to pick this up by taking these possible explanations into account in their case selection and pre‐registering their expectations. Related, our study cannot shed light on the reasons why people feel relatively deprived, because these reasons may largely differ in the countries of investigation. However, our results do show that when individuals do feel deprived (for whatever reason) they are more susceptible to populist messages and this applies across different countries.

The actual manipulation of populism may be regarded as an additional potential limitation. Compared to the control condition, the treatment conditions cultivate both in‐group preferences as well as blame attribution, and our design does not enable us to tease out the isolated effects of these levels of the independent variable. However, in line with social identity framing, persuasive and mobilising social identity frames cultivate both an in‐group threat and a credible scapegoat (e.g., Polletta & Jasper Reference Polletta and Jasper2001). We therefore regard our manipulation of populism as a social identity frame as valid. Relatedly, as we did not measure pre‐treatment levels of our dependent variable, our conclusions are based on between‐subjects comparisons. An important implication is that we cannot fully test the mechanisms of SIT. Although pre‐ and post‐treatment measures may allow for a stronger assessment of the influence of isolated independent variables, a downside for online experiments is that the period between pre‐ and post‐measures is very short, and that the item wordings of the pre‐treatment may prime scores on the post‐treatment. However, in light of these limitations in the design of our experiment, we recommend future research to design experiments with a more fine‐grained manipulation of social identity, while including different dependent variables that tease out the effects of social identity framing on different related perceptions.

That being said, this study makes a significant contribution to our understanding of the persuasive and mobilising effects of populist communication. Considering populism's political relevance, it is surprising that our study is one of the first to address these questions. Whereas previous research has shown that populism is present in communication at various levels (e.g., Ernst et al. Reference Ernst, Engesser, Büchel, Blassnig and Esser2017; Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, De Lange and Van Der Brug2014) affecting a plethora of evaluations, perceptions and attitudes (Arendt et al. Reference Arendt, Marquart and Matthes2015; Bos et al. Reference Bos, Van der Brug and De Vreese2011; Hameleers et al. Reference Hameleers, Bos and De Vreese2017, 2018b; Müller et al. Reference Müller, Schemer, Wettstein, Schulz, Wirz, Engesser and Wirth2017; Sheets et al. Reference Sheets, Bos and Boomgaarden2016), the results in this article make clear that it is because of the priming of anti‐elitist identity considerations that voters are more likely to agree with and be engaged by these messages. In addition, our findings improve our understanding of why those citizens that feel disadvantaged (Spruyt et al. Reference Spruyt, Keppens and Van Droogenbroeck2016) are more likely to be persuaded and engaged by populist communication. In the current setting of growing dissent of parts of the European electorate, this study has important ramifications, as various actors may use populist identity cues – which may even partially explain the success of many populist movements around the globe.

Acknowledgement

By providing the funds for setting up an interdisciplinary research network this research was supported by the European Cooperation on Science and Technology (COST) action IS1308 on ‘Populist Political Communication in Europe: Comprehending the Challenge of Mediated Political Populism for Democratic Politics’.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting informationmay be found in theOnlineAppendix section at the end of the article.