1.1 Premise

Pre-Islamic Arabia is a rarely explored subject. Yet first-millennium Arabia is a particularly fertile ground for a historical enquiry into ethnicity, human conflict and the transition from polytheism to monotheism. This book, based on my dissertation submitted for the degree of doctor of philosophy at the University of Cambridge in early April 2021,Footnote 1 is the first extended study by a single author on the late antique history of the Arabian Peninsula and its northern extension (the Syrian Desert). A particular focus is on religious attitudes, with a view to shedding light on cultural developments and events between the end of the third and the beginning of the seventh centuries. This was a period of significant change culminating in the rise of Islam. Accordingly, the temporal boundaries of this enquiry are roughly delineated by the epitaph of Imru’ al-Qays, one of the earliest and most famous kings ‘of the Arabs’, dated to 328, and by the death of Muḥammad, prophet of the new Muslim community (Ummah), in 632.Footnote 2 However, establishing the geographical limits of a region that was never unified by a single political entity is a complex task. Arabia was either fragmented as it is today or incorporated into a broader entity as in Muslim times. The absence of a unified political structure in this region allows for writing the ‘history of Arabia’ without falling into the anachronistic fallacy of referring to a modern concept such as the ‘nation’.Footnote 3 On the other hand, it becomes necessary to clarify where exactly the Arabian Peninsula ‘ends’. Moreover, if Arabia is understood as the ‘land of the Arabs’, it is also imperative to clearly define this group.

Recent enquiries into the history of pre-Islamic Arabia have adopted the 200 mm/year isohyet (rainfall line) as the northernmost border of the Arabian Peninsula,Footnote 4 corresponding to the ‘absolute limit of rain-fed agriculture’.Footnote 5 Yet this approach is problematic because it does not consider social mobility and dynamic cultural interactions between nomads (dependent on cities for bare subsistence and utensils) and sedentary groups (who relied on nomads for tasks ranging from simple warfare to the escorting of trading goods). Sedentary Arabians supported themselves through agriculture and pastoralism. Yet they were also active traders, as testified by a wide array of inscriptions pointing to a symbiosis between settled populations and nomads in the Ḥawrān in the first four centuries of the first millennium.Footnote 6 Michael Macdonald, one of the foremost scholars to adopt the 200 mm/year isohyet as a border,Footnote 7 has recently pointed out that ‘the traditional antithesis of the “Desert and the Sown” hinders, rather than helps, our understanding’.Footnote 8

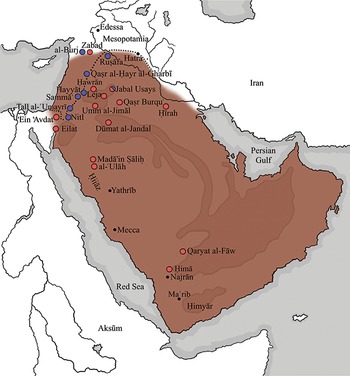

Moreover, while it is common to delineate geographical boundaries on the basis of scripts and/or languages, the use of one language to define one space is also inherently problematic for pre-Islamic Arabia. Scholars have claimed that language provided both a sense of cultural cohesion for Arabs and, at the same time, a feeling of distinction from non-Arabs,Footnote 9 and that the pre-Islamic ‘rb were ‘people of Arabic language’.Footnote 10 There is, however, much uncertainty regarding the extent to which language was a bonding force for the inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula before the appearance of the Qurʼān, the first Arabic document on parchment. While fewer than twenty inscriptions are universally accepted to be in ‘Old Arabic’, several languages and scripts were recorded in the peninsula during pre-Islamic times. Alongside the Ancient North and South Arabian corpora, the ‘Nabateo-Arabic’ (or ‘Transitional’) and ‘Old Arabic’ inscriptions constitute a valuable tool to uncover the history of pre-Islamic Arabia (see Figure 1.1).Footnote 11 Although the Nabatean Kingdom, established between Negev and Ḥijāz (the geographical location of modern-day Medina and Mecca), was incorporated into Rome’s Arabian Province by Trajan in 106,Footnote 12 the evolving Nabatean script continued the Nabateans’ legacy, as it spread throughout Arabia and eventually replaced the Ancient North Arabian script.Footnote 13

1.1 Map of the Arabian Peninsula.

Grasso and D’Amico (2021). The map was adapted from Hoyland (2001), p. 4 (who adapted his map from Macdonald (2000), p. 39). The dotted line corresponds to the 200 mm (8 inches) of rainfall per year (Hoyland and Macdonald). The red dots mark where Nabateo-Arabic, and Old Arabic inscriptions have been found (Grasso). In contrast, the blue dots correspond to the sites where Jafnid inscriptions have been discovered (Grasso). Several new inscriptions were discovered in the summer of 2021 by the Ṭāʾif-Mecca Epigraphic Survey Project, funded by the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies. The inscriptions are not featured in this map as they are unpublished at the time of writing this book.

Whereas recreating the history of the Arabs before the formation of an Arab consciousness and an Arabian unified collectivity has generated anachronistic approaches in the past, the spread throughout the peninsula of Old Arabic lends weight to the notion of the existence of a certain degree of cultural uniformity in the region. The epigraphic fusion of southern and northern Arabian local features (e.g., theonyms) further supports a global vision of pre-Islamic Arabia. The geographical boundaries of this book are thus defined as being both linguistic and political. While we can consider the most southern ‘border’ to be the Arabian Sea, we can define the northern border as being a linguistic barrier, passing through Zabad (Syria), where the northernmost Old Arabic inscription was found. This area includes the Syrian Desert, as most of the graffiti in Ancient North Arabian was found there. Finally, the western and eastern boundaries correspond to the Arabian borders of the Roman and Sasanian empires and, more precisely, to the limites of their Arabian allies’ federations, that is, the Tanūkh, Salīḥids and Jafnids for the Roman Empire, and the Naṣrids for the Sasanian Empire.Footnote 14 Thus, the western limit of this enquiry is a line stretching from ʿAqaba to Zabad (roughly corresponding to the 200 mm/year isohyet), where all the inscriptions of the Jafnids, the main sixth-century Arabian partners of Rome, were discovered. Likewise, the eastern boundary corresponds to the borders of the Arabian Naṣrids.

At the dawn of Islam, the Arabian Peninsula was fringed with great empires (Iran, Rome and Aksūm) and was at the centre of a lucrative network of trade routes. Therefore, this book aims to pull together all the strands of the composite cultural and political milieu of the region, placing its history in the context of the broader environment of Late Antiquity. Although the kingdoms of South Arabia and Aksūm were transterritorial and multiethnic (or at least composed of one ethnic group dominating over people perceived as ‘other’), I use the word ‘kingdom’ to define these polities as they were made up of several territories and peoples only for a short period during Late Antiquity (i.e., Aksūm’s invasion of South Arabia and the following establishment of a satellite polity ca. 530–5, and South Arabia’s conquests in Central Arabia ca. 535–65). The use of the word ‘empire’ requires that ‘different peoples within the polity will be governed differently’,Footnote 15 but we have minimal information to assess how South Arabia and Aksūm dealt with the people they conquered. Moreover, I use the word ‘Iran’ or ‘Sasanian’ to refer to the empire of the Sasanians (224–651) and the term ‘Rome’ to refer to the Roman Empire (both Western and Eastern). The rationale behind this motivation is simple. The lexeme ērān is attested as a political entity on the first Sasanian ruler Ardashīr I’s investiture relief at Naqsh-e Rostam in Fārs and on his coins.Footnote 16 Ardashīr’s ‘idea of Ērānšahr, ‘the kingdom of Iran’, persisted through time by Shāpūr I (who expanded the rulers’ title to ‘King of Kings of Iran and Non-Iran’), Narseh and Shāpūr III, who adopted the lexeme.Footnote 17 The use of this endonym is preferable to the name of the south-western province of ‘Persia’ or to the exonym ‘Persian’, used by Greek historians from the fifth century bce, while the Achaemenid Empire (550–330 bce) referred to itself as ‘The Empire’ (Khshassa).Footnote 18 The same considerations apply to the use of the word ‘Rome’. Anthony Kaldellis has recently demonstrated that the so-called ‘Byzantines’ considered themselves Roman and called their polity Romanía.Footnote 19 Scholars have condemned Kaldellis’ label of this entity as a ‘nation state’ instead of an empire, but it remains undeniable that the ‘Byzantines’ of Late Antiquity defined themselves as Romans.Footnote 20 To avoid privileging an (often ‘external’) perspective over another, I use endonyms to refer to the political entities mentioned in this work. The use of ‘Aksūm/Aksūmite Empire’ is preferred to ‘Ethiopia/Ethiopian Empire’, as a large portion of ancient Aksūm included Eritrean territories.

As recently highlighted, ‘it is an incontestable fact that the suffocating majority of attention falls on the same small part of the world’.Footnote 21 The study of geographical areas such as Arabia is still vastly underrepresented in any academic debate concerning medieval history. Any such debate has often become synonymous with the sole study of western Europe. It is imperative to widen the geographic focus of contemporary enquiries in Late Antiquity to understand this period better, counterbalancing the Eurocentric views of the past that have long dominated and shaped our comprehension of the broader medieval world. Such a shift in direction and focus may well be considered challenging and slightly intimidating because of historical reasons and the need for knowledge of somewhat ‘obscure’ languages from the regions which are the focus of this neglected (geographical) area of study. However, the few steps taken so far in this direction to expand the academic ‘common’ geographical area of enquiry have dramatically contributed to our understanding of this world. Reflecting on the past of regions that have been pushed into the historical shadows and the interactions of these regions with what was the oikumene of past Western scholarship (notoriously centred around Rome) will deepen our understanding of the fluid relations of past and contemporary societies. As stated by Robert Hoyland in his discussion of early Islam, the problem ‘is not so much lack of the right materials, but of the right perspective’.Footnote 22 By exploiting an eclectic array of archaeological sources and literary accounts, primarily composed in Greek, Syriac and Arabic, I hope to offer an original perspective on the cultural milieu of late antique Arabia. The structure of contemporary universities usually compels scholars to look at these disciplines in a compartmentalized way. This approach has led Semitic philologists to work on Qur’ānic lexicon and rhetoric, while classicists focus on the Jafnids and archaeologists study the testimonies of South Arabia. Interactions between these disciplines are sporadic and often superficial. My attempt is to pull the interactions of cultures in pre-Islamic Arabia together, investigating the cultural milieu where the inhabitants of the peninsula lived and connecting the neglected sociopolitical, religious and economic history of Arabia with its surroundings to construct a coherent historical narrative out of our fragmentary sources and fill a gap in the studies of Late Antiquity.

This first chapter is divided into three sections. First, I present a brief survey of previous scholarship concerning the history of late antique Arabia, the genesis of the Qurʾān and early Islam. I then discuss the sources available for historical research into pre-Islamic Arabia and explore the meaning of the lexemes ‘Arabia’ and ‘Arabians/Arabs’ from Antiquity to the rise of Islam, examining what these terms meant in various periods. In Chapter 2, I move on to an analysis of the political context of North Arabia (from the Syrian Desert to the Najd) between the third and the fifth centuries and the religious attitudes of the inhabitants of this region after Constantine’s conversion to Christianity. The Arabians allied with Iran will receive less space than their Roman counterparts for two reasons. First, there are fewer Iranian sources than Roman sources, so any description of these groups remains highly speculative. Second, Iran had no claims of cultural monopoly. Zoroastrians did not proselytize as much as Christians, and they were not crucial actors in an inquiry into the history of pre-Islamic Arabia. Moreover, while ‘Christian culture’ was largely heterogenous, I am going to use ‘Christianity’ over ‘Christianities’ for the sake of clarity. Chapter 3 focuses on the rise of Judaism in the South Arabian kingdom of Ḥimyar during the same period, offering an interpretative late antique framework for the monotheism of fourth- and fifth-century Ḥimyar and contextualizing the choice made by South Arabian elites to become Jewish sympathizers. Chapter 4 is a chronological continuation of Chapter 3, shifting in focus to the arrival of Christianity in the region and positing economic factors as the leading cause for the massacre of Najrān and the shaping of sixth-century South Arabia while comparing this region with Aksūm. Chapter 5 mirrors Chapter 4, shedding light on the two federations of North Arabia – the kingdoms of Jafnids and Naṣrids – focusing on the impact of Christianity and providing a sociopolitical framework for the relationship between these kingdoms and Rome and Iran through a comparison with the Germans and the Türks.

The history of pre-Islamic Arabia needs to be analysed by taking into account the entire Arabian Peninsula, not only parts of it. Similarly, Islam cannot be understood in isolation from the political and cultural milieux of the surrounding regions. At the same time, this book aims to write the history of pre-Islamic Arabia rather than the origins of Islam. Therefore, only Chapter 6 addresses the Ḥijāz directly, looking at the religious communities in the region at the time of Muḥammad. After evaluating the decline of polytheism in pre-Islamic Arabia and making a case for the existence of henotheistic beliefs, I compare and contrast Muḥammad’s prophetic career with that of the other Arabian prophets, offering some reflections on the Qur’ān itself. My analysis focuses on the sociopolitical exploitation of cults as a mechanism for establishing identities from the end of the third to the beginning of the seventh century. This is not to say that every conversion and religious attitude were subordinated to economic interests and political power in the period, but rather that elites’ conversion and their religious rhetorics had a profound impact on the shaping of the world of Late Antiquity and that the rhetoric of faith became a valuable weapon to be used in economic warfare in the period. Chapter 7 concludes by pulling these various strands together and answers one final question: what made the Arabian milieu capable of producing Scripture of such universal appeal as the Qur’ān? As highlighted by Michael Schmauder in an analysis of the interactions between Rome and the steppe empires in south-eastern Europe, ‘the model of marginal cultures striving for integration into the cultural and political structure of the dominant civilisation’ needs to be revised.Footnote 23

In summary, this book delves into the political and cultural developments of pre-Islamic late antique Arabia. It offers an interpretative framework that contextualizes the choice of Arabian elites to become Jewish sympathizers and/or convert to Christianity and Islam by pursuing a line of enquiry probing a sociopolitical exploitation of cults in the shaping of Arabian identities. I argue that the Arabian rulers’ cautious conversion follows a broad late antique trend which aimed to ease the transition for their subjects and/or to assume a neutral position towards the developments of the surrounding empires. While adopting and internalizing the culture of their powerful trading partners, the Arabians retained a degree of cultural autonomy as testified by the widespread adoption of Judaism, Miaphysitism,Footnote 24 East Syrian ChristianityFootnote 25 and local henotheistic cults. Late antique political entities operating in Arabia exploited these systems of belief as the casus belli of expeditions pursuing trade monopolies. The conjunction of faith and commerce (exemplified by the emergence of ‘pilgrimage nodes’) shaped Arabia’s urban landscape and paved the way for the rise of Islam.

Throughout the first millennium, rulers’ importation of foreign ‘religions’ was often aimed at overcoming internal divisions in a wide array of places such as Rome, South Arabia and Central Asia. Nonetheless, the systems of belief that local Arabian dynasties sponsored by exhibiting monumental inscriptions and funding the construction of religious buildings probably failed to take hold among the lower classes and the more geographically isolated peoples of the region. The political fragmentation of Arabia was further exacerbated by the Christological controversies seeping through Arabia’s social strata due to the preaching of exiled monks. It was only after the fall of local political entities such as that of Ḥimyar and the kingdoms of North Arabia that the conditions for the political and religious unification of Arabia materialized, and a prophet from inner Arabia succeeded in vanquishing factional segregation and converging political, economic and religious interests and attitudes (e.g., scriptural with pagan and henotheist) through the founding of an autochthonous and universalistic (and thus easily exportable in sharp contrast to Zoroastrianism) belief system articulated in the newly formed local lingua franca and script. Islam leveraged the dissatisfaction with current political rule and emerged in its Arabian milieu to gain economic advantages, eliminate Iran’s hegemony over the region and settle tribal divisions. At the same time, it provided a faith-based process for establishing identities and overcoming competing tendencies characteristic of the broader late antique world. In the second half of the seventh century, the adoption of kingly conduct by the Umayyad caliphs, more akin to that of Roman and Iranian rulers and of the Arabian Ḥimyarites and Jafnids than that of Muḥammad, signalled the completion of a process based on the belief in an extramundane dimension.Footnote 26

Muslim accounts emphasize the barbarism of Romans and pre-Islamic Arabians in similar terms. However, while Islam inherited the ideological portrayal of pre-Islamic Arabians as barbarians and in antithesis to ‘ilm (‘knowledge’), the ‘rupture’ between ‘pre-Islamic’ and ‘Islamic’ ought to be reconceptualized as a process of transformation. No historical framing of the emergence of Islam can be traced without pre-Islamic Arabia. Hence, by focusing on the different degrees of participation and mediation as well as on buffer zone policies, this book aims to be the first extended study on this subject which positions the Arabians and the ‘peripheries’ of the late antique empires at the centre. My goal is to liberate and grant autonomy to the Arabians from marginalizing (mostly Western-produced) narratives framing the Arabians as ‘barbarians’ inhabiting the fringes of Rome and Iran and/or deterministic analyses in which they are similarly depicted retrospectively as exemplified by the Muslims’ definition of the period as Jāhilīyah, ‘ignorance’.Footnote 27 The recent exhibition Roads of Arabia, organized by the Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities, showcased artefacts dated from the early lower Palaeolithic to the Ottoman period. The exhibition aimed to tell the story of the region’s development over millennia but failed to cover the centuries before the emergence of Islam, partly corresponding to the period of Late Antiquity (just a few steps divided a series of frescoes datable to the first centuries ce from the first Islamic inscriptions, but these steps are supposed to cover half a millennium).Footnote 28

While the Sasanians were Rome’s greatest enemy in this period, the negative counterparts of the Romans in the literary sources were the ‘barbarians’. This Roman label produces a misleading sense of a collective entity conceding with ‘an inferior state of human evolution’.Footnote 29 Although the Romans perceived a binary division between their ‘human and civilized category’ and the ‘barbarians’, the relationship between these two categories was dynamic, and it was possible to cross boundaries by process of ‘acculturation’. Unlike other empires’ ‘labels of otherness’, shared blood was not a funding criterion to determine foreign peoples in late antique Rome. In China, for example, unfamiliar people were addressed by using ethnonyms that had no relation to cultural behaviour, as exemplified by Ban Gu’s (d. 92) description of the Xiongnu.Footnote 30 In both regions of Eurasia, the rise of Buddhism and Christianity slowly caused the disintegration of the ‘barbarians’ collective identity’, as people inhabiting the borders of the Roman and Chinese oecumene embraced monotheism. In the second half of the first millennium, the rise of the third ‘universal’ monotheistic religion, Islam, reinforced fears of otherness and led to new mental frontiers based on faith. The emergence of Islam, the fast Muslim conquests and the consequent creation of the Muslim Commonwealth smashed physical borders. Still, it created new mental challenges, exacerbating existing cultural divisions and creating new sine qua non to mark otherness.Footnote 31

1.2 A Brief Survey of Previous Research

The modern debate on the genesis of Islam started in 1833. In that year, the father of Reform Judaism, Abraham Geiger, published a book titled Was hat Mohammed aus dem Judenthume aufgenommen?, making an early contribution to the formation of Qurʾānic studies by analysing all Islamic references to biblical figures and underlining the rabbinic influences on the Qurʾānic material.Footnote 32 This publication rapidly encouraged scholars to evaluate the development of early Islam through a comparative analysis of the Old and/or New Testaments and the Qurʾān. The discrepancy between these preliminary results was striking. On the one hand, scholars such as Hartwig Hirschfeld,Footnote 33 Josef Horovitz,Footnote 34 Heinrich SpeyerFootnote 35 and Charles TorreyFootnote 36 strongly emphasized the intertextuality between the Jewish corpus and the Qurʾān. On the contrary, others, such as Richard BellFootnote 37 and Tor AndræFootnote 38 repeatedly highlighted the Qurʾān’s Christian background. In 1860, another seminal book was published, namely Geschichte des Qorans by Theodor Nöldeke.Footnote 39 The latter did not get involved in the contentious debate about Judeo-Christian influences on the Qurʾān but instead offered a deep analysis of the Qurʾānic suwar (chapters), proposing an authoritative chronology of the internal structure of the Muslim Holy Book. This work was shortly followed by Julius Wellhausen’s enquiry into the pagan cults of Arabia (upholding Christian influence on the Qurʾān),Footnote 40 and by Ignác Goldziher’s studies on the aḥādīth (accounts about Muḥammad)Footnote 41 and tafāsīr (Qurʾānic exegesis).Footnote 42

In 1936, an original article by Johann Fück outstripped much of the preceding scholarship grounded in biblical studies, marking a change of interest in Qurʾānic research away from the comparative approach focused on the biblical tradition.Footnote 43 Instead, it foregrounded the study of Muḥammad’s biography, as did the famous books by William Montgomery Watt, published in the mid-1950s.Footnote 44 Gonzague Ryckmans’ work on pre-Islamic idolatry also appeared during the same years.Footnote 45 A renewed interest in the composite milieu on the eve of Islam was later shown in the 1970s by the provocative works of the so-called ‘revisionist school of Islamic studies’. John Wansbrough, one of its significant exponents, argued that the Qur’ān went through a long period of oral transmission within various independent sectarian communities familiar with Judaic-Christian preaching. He also claimed that the Qur’ān had been redacted in Mesopotamia during the eighth century.Footnote 46 The same year, Patricia Crone and Michael Cook published a controversial thesis claiming that Islam emerged from the preaching of a Jewish messianic movement called ‘Hagarism’.Footnote 47 While Wansbrough and Crone vastly overstated these cases, Gerald Hawting confirmed that the emergence of Islam owed more to debates and disputes among monotheists than to arguments with idolaters.Footnote 48 Crone also published a groundbreaking reassessment of the Meccan trade, which had the merit of engaging many scholars in further debates,Footnote 49 as exemplified by her verbal crossfire with Robert Serjeant.Footnote 50 While the works of the revisionist school had considerable value, many of them are now considered outdated. The discovery of the Ṣanʿāʾ palimpsest and, more recently, that of the Qurʾānic manuscript in Birmingham, carbon-dated with 95.4 per cent accuracy to between 568 and 645 ce, rendered many of their theories obsolete.Footnote 51

At the end of the twentieth century, an interest in pre-Islamic Arabia was reignited, mainly thanks to Toufic Fahd’s enquiry.Footnote 52 The beginning of the new century also saw the creation of the Encyclopaedia of the QurʾānFootnote 53 and Andrew Rippin’s work on the tafāsīr (Qur’ānic exegesis),Footnote 54 composed on the lines of Goldziher’s previous studies. At the same time, the revolutionary research of Christoph Luxenberg was released, which proposed an eccentric Syro-Aramaic reading of the Qurʾān as if it were a Christian oeuvre.Footnote 55 The book sparked a resurgence of research focused on interactions between the scriptural communities and their impact on the formation of Islam, particularly for those inclined to read Judeo-Christian influence in the Qurʾān. In the same period, a surge of interest among classicists in Rome’s neighbours led to numerous attempts to include the Arabian Peninsula in studies on the Eastern Roman Empire. However, the focus of these enquiries remained steadily centred on Rome.

From 1984 to 1995, Irfan Shahid published a series of volumes titled Byzantium and the Arabs, which aimed to explore the relations between the Roman Empire and the ‘Arabs’ from the fourth to the sixth centuries and, in so doing, provide ‘a background for answering the largest question in Arab–Roman relations, namely, why the Arabs were able in the seventh century to bring about the annihilation of the Roman imperial army at the decisive battle of the Yarmūk on 20 August, A.D.636’.Footnote 56 Although bogged down by tangential excursuses and repetitions,Footnote 57 Shahid’s publication had many merits, especially in regard to its exhaustive bibliography. Literary sources in Syriac, Arabic, Latin and Greek were extensively explored. However, Shahid’s works had two major methodological problems. First, he used the term ‘Arab’ as an ethnicon, though there was a lack of clarity regarding the meaning of this lexeme. The volumes’ title is misleading as Shahid dealt only with ‘the groups that are termed foederati, the allies of Byzantium’.Footnote 58 Second, he portrayed the ‘Arabs’ as a pious Christian group, overstating the importance of Christianity to define the late antique Roman–‘Arab’ relationship.Footnote 59 Maximal interpretations of biased and fragmentary material serve this agenda.Footnote 60 The result is a series very much focused on Rome and Christianity and only secondary to (one group of) the ‘Arabs’, even if Roman sources such as Procopius are accused of employing ‘the technique of suppressio veri and suggestio falsi’.Footnote 61

Shahid’s monumental series was preceded by The Roman Empire and Its Neighbours (1967) by Fergus Millar, who returned to ‘Rome’s Arab Allies’ multiple times before passing away in 2019.Footnote 62 Shahid’s and Millar’s works converge on various points, as testified by Shahid’s glowing review of Millar’s The Roman Near East, 31 bc–ad 337 (1993). Shahid concurs on the fact that ‘their [the “Arabs”] Arabness was much diluted by the forces of Hellenization and Romanization’, though he complains against Millar’s portrayal ‘of the Arabs as those nomads of the steppe who appear as a threat to the Roman-controlled Near East’.Footnote 63 Millar had argued for the existence of a Near Eastern public culture dominated by Greco-Roman culture under the effect of ‘Romanization’, discussing whether to place the Roman Near East as part of the ‘Orient’ or the Greco-Roman world.Footnote 64 Millar focused on what he defines as ‘distinctive pockets of “Romanness”’, giving large space to the role played by the Greek language.Footnote 65 As shown in Chapter 5, Greek is documented in a few monumental inscriptions written by elites in Arabia. The thousands of examples of Safaitic graffiti, which can potentially shed light on the ‘common people’, are entirely omitted from the narrative. As Shahid, Millar reserved in recent times large space to the ‘Arab or Saracen allies (foederati)’, arguing that they constituted the only case in which ‘local territorial political formations’ were ‘other than Greek cities’.Footnote 66 This Romano-centric vision is what I would like to counterbalance with this work.Footnote 67

Another prolific scholar addressing the relationship between Rome and Arabia in the 1980s was Glen W. Bowersock in Roman Arabia (1983).Footnote 68 Millar defined the book as an ‘intelligible narrative and administrative framework for more ambitious future studies’.Footnote 69 Roman Arabia was followed by Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World, edited by Bowersock, Peter Brown and Oleg Grabar (1999),Footnote 70 a pioneering collaborative work that succeeded Peter Brown’s seminal book The World of Late Antiquity, today considered as a sort of manifesto of late antique studies.Footnote 71 In 1936, the thought-provoking thesis of the then twenty-year-old Santo Mazzarino had anticipated Brown’s attempt to grant autonomy to the ‘history of the later Roman Empire’ after being uniquely conceived as an ‘imperial “storia della decadenza”’.Footnote 72 Although the concept of Late Antiquity was also identifiable in the preceding works of the art historians Alois Riegl (who coined the term Spätantike) and Josef Strzygowski,Footnote 73 Brown is today considered the ‘inventor of late antiquity’ in popular culture.Footnote 74 As he advocated in its pages, The World of Late Antiquity brought ‘the average reader a sense of the richness and excitement of a once-neglected period’.Footnote 75 However, a widely accepted interpretation of Late Antiquity is impossible to find.Footnote 76

At least from Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, historians have often turned to the wide Eurasian world for their studies (frequently to contextualize European history).Footnote 77 In the first publication in the series Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam, appearing in 1992, Lawrence Conrad and Averil Cameron argued for the joint study of Late Antiquity and Early Islam (potentially into the ‘Abbasid revolution’).Footnote 78 A recent advocate for what we could name the ‘elongation’ and ‘enlargement’ of Late Antiquity has also been Garth Fowden, first in his Empire to Commonwealth: Consequences of Monotheism in Late Antiquity, and later in his study of the first-millennium world titled Before and after Muḥammad.Footnote 79 Other works have recently explored the Roman frontier and the rise of Islam within the broader framework of Late Antiquity by integrating it into the philosophical, artistic and legislative framework of the period, for example, Bowersock’s latest publication, The Crucible of Islam.Footnote 80 A series of significant collaborative volumes on the period have also appeared.Footnote 81 Hence, this is not the first attempt to expand Late Antiquity, either temporally or geographically. This is also not the first time Arabia has been studied in relation to surrounding empires.Footnote 82 However, this is the first time pre-Islamic Arabia in its entirety is the protagonist of a monograph that is dedicated to the study of the late antique world in its political and cultural kaleidoscopic facets. Here I aim to situate the history of pre-Islamic Arabia in this wide interconnected world, which was not the direct product of a declining classical world, but an actor of new developments, changes and ideas in its rights. A long and a (though still less familiar) ‘large’ Late Antiquity have been often advanced. Arabia is crucial to the narrative of this enlarged geographical and temporal space not only for its role in Islam’s Mutterland but for its strategic position between belligerent empires and its central role in what we could define as the Arabian ‘Silk Roads’, given that silk was only one of the good of any trade route of the time and that there was no single east–west ‘road’.Footnote 83 Arabia’s dramatic landscape also encouraged the ascetic practices of itinerant holy men and fleeing ‘heretics’, making it a perfect intersection of scriptural traditions. Late Antiquity is not a period of decay but active creation and new developments. For one thing, it is when Christianity spread and Islam rose. The rise of the latter, largely indebted to the spread of the first, took place in inner Arabia, and it is thus mandatory to look at this region for understanding the following shaping of the medieval world. Indeed, the Qur’ān is a product of the world of Late Antiquity but needs to be approached as a monument of ancient Arabia too.

Similarly to works dealing with Central Asia that have characterized the region as a ‘crossroads’ (i.e., as ‘a junction between real cultural entities’),Footnote 84 historians of the ancient world often have brought Arabia into the picture mostly in relation to Rome and Iran. On the other side, in recent years, scholars of Islam have undertaken investigations of the Qurʾānic material and the origin of Islam through the study of the Judeo-Christian Kutub (books), especially of the Christian tradition composed in Syriac. The Qurʾān has been accordingly interpreted as a composite text extensively rewriting the Ṣuḥuf Mūsā (‘the Scrolls of Moses’).Footnote 85 However, this approach tends to neglect the religious attitudes of the different communities who lived at the time of Muḥammad and specifically the Arabian milieu. Although discussion of Qurʾānic origins is nowadays seen within a broader context, the contemporary debate often still focuses on whether the Qurʾān should be seen as entirely dependent on the Judeo-Christian Scriptures in the line of Geiger,Footnote 86 or as an original and autochthonous product of Arabia. The latter is the view of Angelika Neuwirth, director of the Corpus Coranicum, a German project working towards a critical edition of the Qurʾān.Footnote 87 Neuwirth has proposed to read the Qurʾān as the final product of a complex dialogue that engages with its composite late antique context.Footnote 88 In the last few years, Jacqueline Chabbi,Footnote 89 Reinhard Schulze,Footnote 90 and Aziz Al-Azmeh have also offered excellent in-depth analysis on the origins of Islam.Footnote 91 From these initiatives, we have realized the full benefits of ‘studying early Christianity and Islam comparatively but not a-historically, in other words within a firm sociohistorical framework’, by joining together all the sources and disciplines which concern the pre-Islamic and early Islamic milieu.Footnote 92 Assuming this remark as a postulate, I now illustrate the different sources that can be used to draw a timeline of the history of pre-Islamic Arabia.Footnote 93

1.3 Reflections on the Sources

In a recently published paper on the pre-Islamic talbiyāt (invocations of Allāh made during the pilgrimage to Mecca), Tilman Seidensticker claimed that ‘our knowledge of the religious history of [pre-Islamic Arabia] is considerably poorer than it appeared to be as recently as a generation ago’.Footnote 94 In the same article, he argued that the most relevant testimonies for a study of the period are the Islamic sources. However, both statements are factual only if we isolate the Ḥijāz from its surroundings. Although ‘it is impossible to transfer information from other regions and centuries’ to the area where Muḥammad lived, it is equally impossible to imagine this area as isolated from the remaining parts of the Arabian Peninsula. With this section, I offer some reflections on the sources for the religious history of Arabia between the fourth and the sixth centuries ce. In contrast with Seidensticker, I demonstrate that evidence for pre-Islamic Arabia has never been so abundant, illustrating how this material can expand our knowledge of this region in the late antique period.

There is virtually no independent historical information for the Ḥijāz during Late Antiquity. The Qur’ān imparts little information regarding its immediate religious context. In addition to biblical figures (e.g., Abraham and Jesus), the only names that appear are those of three Arab prophets (Hūd, Ṣāliḥ and Shuʿayb), Muḥammad and a certain Abū Lahab. Four religious communities (Jews, Christians, Magians and the Sabians) and only two peoples (the Romans and the Arab Quraysh) are mentioned. Overall, we should hardly consider Scriptures as historical sources, and we should treat the Qur’ān, with its self-presentation as the speech of God, in a similar fashion. The remaining Muslim sources, which date to at least 200 years after the events they describe, are similarly unreliable. Gustav WeilFootnote 95 and Goldziher asserted that the aḥādīth (sing. ḥadīth) were later fabrications by the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote 96 The works of these scholars also led to a widespread scepticism towards the historical use of the first Islamic tawārīkh (histories), the tafāsīr (sing. tafsīr) and the Sīrat Rasūl Allāh (biography of the Messenger of God). The prejudice towards the Muslim sources grew even further with the works of Crone, who labelled the whole Islamic tradition ‘tendentious’ as composed in a later cultural environment,Footnote 97 and chose to give prominence instead to non-Muslim literary accounts. Although this approach was not universally accepted and the types of sources Crone used were defined as ‘a discrete collection of literary stereotypes composed by alien and mostly hostile observers’,Footnote 98 others adopted an approach similar to Crone’s though in a more measured way,Footnote 99 recognizing that the Muslim tradition had at least some merit for the period after the Muslim conquests.Footnote 100

The scholarly consensus up to that point was that the traditional Muslim sources were not contemporary to the events they portray but were instead the result of a literary process carried out by the early Islamic community. As such, they were likely inspired by exegetical impulses and/or composed under the influence of later debates, emphasizing the supremacy of Muḥammad’s revelation at a time when the querelle among the scriptural communities was vivid. Nevertheless, some literary sources, such as the traditions on the life of the Prophet, have been demonstrated to be consistent and ‘have an authentic kernel’.Footnote 101 Traces of early discussions about the trustworthiness of these testimonies can still be found. Some recently published works have attempted to verify the historicity of the Muslim sources. This has been done by analysing the accounts that negatively portray Muḥammad and are unlikely to have been invented later and by examining their asānīd (lists of authorities who transmitted a report). These publications have successfully shed some light on the redactional process of this material. Indeed, like the non-Muslim literary accounts, which, despite their evident apologetic intents, have the merit of being contemporary to the events narrated, the Muslim literary sources constitute a valuable instrument of enquiry. Even if not considered historical documents, these works reflect some of the tendencies of the early Islamic community. Hence, although there are still some attempts to contextualize the Qurʾān using only non-Muslim literature while denying the trustworthiness of Muslim literary sources, other scholars at least esteem the latter’s usefulness as ‘evidence for the [Islamic] history of ideas’.Footnote 102 Collaborative works uniting contributions by specialists in Muslim and non-Muslim materials aim to produce a more balanced perspective, but they are still in their infancy.Footnote 103

The use of pre-Islamic poetry for reconstructing the history of Arabia is also controversial. In 2001, Hoyland labelled this corpus an ‘insider’ source since it was composed by the inhabitants of Arabia when the events therein were depicted.Footnote 104 Nevertheless, many scholars believe that a large portion of the so-called pre-Islamic poems is not pre-Islamic but instead represent a group of later elaborations produced to support the idea which sees the Qurʾān as born in a savage polytheistic milieu. Two of the most provocative texts published in this regard were written in the 1920s,Footnote 105 largely inspired by the preceding works of NöldekeFootnote 106 and Wilhelm Ahlwardt.Footnote 107 After the publication of Milman Parry’s work on the Homeric poems,Footnote 108 James Monroe convincingly demonstrated that pre-Islamic poetry originated orally and was written down only some centuries after its composition.Footnote 109 The use of writing was then no more than auxiliary, and it was only during the Umayyad period (661–750) that the corpus was systematically written down. This view was rejected by Gregor Schoeler, who claimed that ‘poets and ruwāt (transmitters) possessed written notes and even substantial collections’.Footnote 110 If we accept that pre-Islamic poetry was written down after a long period of oral transmission, many problems regarding the authenticity of this corpus become negligible.Footnote 111 Muḥammad himself was sometimes mistaken for a poet,Footnote 112 and an inscription found in the Negev, containing two lines of poetic Arabic, suggests the existence of poetry in pre-Islamic times.Footnote 113 However, although a later reshaping of the texts can explain the standardized Arabic koinè of the poems, it does not alter the striking contrast between the libertine context of pre-Islamic poetry and the inspired preaching of the Qurʾān, a text that also teems with literary motifs and strands of narratives, but of a very different nature.Footnote 114 Although libertinism and piety could have coexisted (as they did in later Abbasid times), some scepticism towards using this material is reasonable. Because of its controversial dating and irrelevant subject matter, which rarely sheds light on the issues investigated in this work, pre-Islamic poetry will be only marginally examined in this monograph.

Nowadays, we are often lucky enough to integrate the study of literary materials with a range of archaeological finds, rapidly expanding our understanding of the pre-Islamic milieu and the political structures of the Middle East. Although the archaeology of the Roman Near East has received consideration from early times, studies on the religion of pre-Islamic Arabia are still in their infancy.Footnote 115 The digital archives CSAI (Corpus of South Arabian Inscriptions) and OCIANA (Online Corpus of the Inscriptions of Ancient North Arabia) now help scholars to uncover the material culture of ancient civilizations and deliver emerging insights into the history of this much neglected geographical area. The present work is a first attempt to interpret these inscriptions and the available literary sources as a unitary data set. This material offers a corrective reading to the literary accounts and has made obsolete the scanty literature on the cults of Arabia before Islam which was produced in the last century. Indeed, works such as those of Jacques RyckmansFootnote 116 and Joseph Chelhod,Footnote 117 produced between the 1940 and the 1960s, are nowadays outdated in many aspects. Studies on literacy in pre-Islamic times and the medieval Middle East are also still in their infancy.Footnote 118 It is unclear to what extent Arabians participated consciously in ‘acts of authorship’, as in the case of other ancient peoples.Footnote 119 Nonetheless, the high number of Arabian graffiti appears to offer some information on the ‘common people’ of Arabia who had only limited connections with the southern Syrian urban centres.Footnote 120

The Arabian origin of this material and its direct witness to the events it attests makes it a more valuable testimony to pre-Islamic Arabian developments than literary sources composed in another time and/or space. Nonetheless, writing the history of Arabia exclusively through studying its epigraphic documents is as dangerous as attempting to do so only using literary sources.Footnote 121 Material culture must be integrated aliorsum from literary sources. Archaeology is just one of the tools we possess to confirm or disprove the historical accuracy of the Qurʾān, itself a monument, and to illuminate its complex genesis. Similarly, an uncritical reliance on Classical Arabic sources is as problematic as its complete dismissal favouring sources composed in the Eastern Roman milieu. These latter consist of various genres (e.g., church histories, hagiographies, hymns) with multiple purposes and agendas. Seeking to present the available data on pre-Islamic Arabia objectively, I give more space to the sources with good reliability and representativeness. For this reason, archaeological material will have priority over literary accounts. Moreover, I adopt a comparative approach that seeks parallelisms and direct correlations while comparing and contrasting empires, societies and cultural developments and milieux.

1.4 Which Arabia and Which Arabs? A Lexicographic Journey from Antiquity to the Rise of Islam

From a geographic perspective, the Arabian Peninsula is broadly divided into four areas: (1) the western highlands between the Red Sea and the basaltic desert known as Ḥarrat al-Shām; (2) the deserts of the central al-Rubʿ al-Khālī (Empty Quarter) and Syria; (3) the eastern coast by the Persian Gulf; and (4) the mild southern highlands. In the Oxford English Dictionary, an ‘Arab’ is defined as: ‘A member of a Semitic people, originally from the Arabian Peninsula and neighbouring territories, inhabiting much of the Middle East and North Africa.’Footnote 122 The definition thus takes into account: (1) in-group identification and belonging to the ‘Semitic people’; and (2) the geographical boundaries of the Arabian Peninsula.Footnote 123 On the grounds that we cannot use current definitions to interpret the past, I now address the problem of identifying Arabia and the ‘Arabs’ from Antiquity to the rise of Islam by analysing primary sources dated between the first millennium bce and the sixth century ce. Were there any Arabs in pre-Islamic Arabia? Modern scholarship has recursively translated the Semitic root ‘-r-b as ‘nomads’ from the publication of a pioneering work by Theodor Nöldeke onwards,Footnote 124 and/or has used the term ‘Arabs’ to refer to the inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula in pre-Islamic times.Footnote 125 Because of recent archaeological discoveries, we now know that these interpretations must be revised.

1.4.1 Neo-Assyrians

From Shalmanasser III (858–24 bce) onwards, mentions of Arabia and the Aribbi frequently appear in the Neo-Assyrian annals.Footnote 126 The following text can be found in the annals of Sargon (722–705 bce): ‘The tribes of Thamūd, Ibadidi, Marsimani and ‘Ephah, the distant Ar-ba-a-a who inhabit the desert (rūqūti āshibūt mad-ba-ri), who know neither high nor low official (governors nor superintendents), and who had not brought their tribute to any king.’Footnote 127 The text also mentions ‘Pharaoh, king of Egypt, Shamsi, queen of the A-rib-bi, Ita’amra, the Sabean’.Footnote 128 While it is unclear whether ‘the distant Ar-ba-a-a who inhabit the desert’ was an epithet of the four aforementioned Arabian groups, it is plausible that these people inhabited the same geographic area. Although only the North Arabian Thamūd are mentioned in many different sources, including the Qur’ān,Footnote 129 we can place the Ar-ba-a-a geographically, almost certainly between Palestine and North Arabia.

Conversely, it is uncertain if there was a distinction between Ar-ba-a-a and A-rib-bi. Although the second lexeme may point to populations with a well-established central government,Footnote 130 the phrase āshibūt mad-ba-ri (and not just the lexeme Ar-ba-a-a/A-rib-bi) means that the Ar-ba-a-a inhabited the desert. This questions previous etymological explanations (based on Neo-Assyrian texts) that the word ‘Arab’ was synonymous with ‘nomad’.Footnote 131 In addition, the term ‘Arabia’ is entirely missing from Neo-Assyrian records. Hence, the Pharaoh is the king of Egypt, but Shamsi is the queen of the A-rib-bi, a clear indicator of the lack of a common Arabian identity. The root ‘-r-b merely hints at different groups living broadly in the same geographical area between the Syrian Desert and the Ḥijāz and indicates both the scattered tribes of the desert and the kings allied with Assur. Nonetheless, there might also have been a differentiation between Ar-ba-a-a and A-rib-bi based on these groups’ relationship with Assyria.

1.4.2 Old Testament

The most interesting mentions of the Arabian Peninsula and its inhabitants in the Tanakh are found in the book of Jeremiah, datable to the sixth century bce.Footnote 132 The excerpt from Jeremiah names the nations to whom God sent the ‘Weeping Prophet’: ‘and the kings of the isles which are beyond the sea, Dedan, and Tema, and Buz, and all that are in the utmost corners, and all the kings of ʿrb, and all the kings of h-ʿrb who dwell in the desert (hshkym b-mdbr)’.Footnote 133 The words used to indicate the desert are mdbr and ʿrb, respectively translated as ‘wilderness’ and ‘desert’, in the King James version of Isaiah 35.Footnote 134 Thus, there is a connection between the ʿrb and North Arabia, where Dedan, Tayma and Buz are found.Footnote 135 Even though the ʿrb ‘dwell in the desert’ both in the annals of Sargon and the book of Jeremiah, dateable to two centuries later, nothing points to a particular ‘Arab’ ethnicity or lifestyle. Elsewhere in the Bible, the ʿrb are mentioned with different people such as the Ethiopians,Footnote 136 as well as in connection with unknown places.Footnote 137 Nonetheless, there is general agreement that they were found in North Arabia and ‘dwelling in the desert’ two centuries after the Neo-Assyrian rulers.

1.4.3 Classical Sources

In the fifth century bce, Herodotus defined Arabia as ‘the furthest of inhabited lands (oikumene) in the direction of midday’ delimited in the south by the ‘Erythraean Sea’, in the north by Assyria and Palestine, in the west by mountains bordering Egypt and the Arabian Gulf and in the east by Iran.Footnote 138 Shortly after, Xenophon identified Arabia as the land on the left of the Euphrates where Cyrus’ army passed through.Footnote 139 Four centuries later, Diodorus Siculus (d. ca. 20 bce) situated Arabia between Syria and Egypt, specifying that the ‘part of Arabia which borders upon the waterless and desert country’ is called Arabia Eudaimon (‘Happy Arabia’, Felix in Latin).Footnote 140 After Trajan’s annexation of Nabataea to the Roman Empire in 106 ce,Footnote 141 and the following creation of the Provincia Arabia (or Arabia Petraea), Ptolemy (d. ca. 170) delimited Arabia Felix on the north by Arabia Petraea and Arabia Deserta, on the east by the Persian Gulf, on the west by the Arabian Gulf and on the south by the Red Sea.Footnote 142

While Arabia included the entire Arabian Peninsula in the classical sources, the Arabioi are, according to Herodotus, only the inhabitants of the seaboard of Arabia, known for respecting pledges, wearing girded up mantles, having ridden on camels in the army of Xerxes and venerating Dionysus and Aphrodite (called Alilat).Footnote 143 Diodorus Siculus claimed that the ‘Arabioi, who bear the name of Nabateans’ inhabited the deserted eastern parts of the peninsula, while the central part is ‘ranged over by a multitude of nomadic Arabioi’ and ‘a multitude of farmers and merchants’ was found in the northern part lying towards Syria.Footnote 144 Strabo (d. ca. 23),Footnote 145 Pliny (d. 79)Footnote 146 and Ptolemy (d. ca. 170) described a group named Scenitae among the various Arabian peoples,Footnote 147 and Ammianus Marcellinus (d. ca. 395) claimed that the Scenitae Arabs became known as ‘Saracens’.Footnote 148 The Saracens are mentioned together with the Thamudians in the Notitia Dignitatum,Footnote 149 and in the work of the first known Syriac author Bardaiṣān (d. 222), who distinguished them from the Ṭayyāyē,Footnote 150 a common Syriac term denoting the inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula.Footnote 151 A bilingual inscription (Greek and Nabatean) found in a temple Ruwāfa,Footnote 152 roughly dated to 166–9 ce, further attests to an early epigraphic appearance of the lexeme ‘Saracens’ (Nabatean shrkt, from the Semitic root sh-r-k, ‘to associate’; Greek ethnos).Footnote 153 Ethnos also appears in a southern Syrian inscription to a Roman governor by a group defining themselves as oi apo ethnous nomadōn, the ethnos of the nomads, perhaps soldiers chosen among the nomads.Footnote 154

In conclusion, after Trajan created Provincia Arabia, there were three ‘Arabias’: Felix, Petraea and Deserta. In a similar fashion to Neo-Assyrians and the Jewish, the classical authors did not consider the inhabitants of South Arabia to be Arabioi. Lexemes such as Scenitae and Saraceni were later used to indicate different peoples inhabiting the Arabian Peninsula, thus distinguishing between unconquerable Bedouins and the first Roman allies. The Romans identified their neighbours based on ethnographic classifications that rarely correspond to late antique self-identification.Footnote 155 Hence, the Arabians were, like the Scythians, ‘literary constructions of a Greek cultural other, a mirror into which the Greeks might look to perceive more sharply their own civilization’.Footnote 156 Similarly, the Huns (a syncretistic entity merging the world of the steppe and the Chinese Empire)Footnote 157 were as unlikely to consider themselves Scythians,Footnote 158 as the Franks were to consider themselves Germans or the people inhabiting the Arabian Peninsula to think themselves to be Arabs. There is no direct attestation of a group describing themselves as ‘Arabs’ in ancient times. Nonetheless, ethnic identities were not without meaning, and it is unlikely that perceptions of identity were utterly absent.Footnote 159 The separate mentions of Arabs/Arabians in Neo-Assyrian, Jewish and Graeco-Roman texts, which were highly unlikely to have been derived from each other, make it plausible that a group, probably inhabiting the north, were already calling themselves as such. Thus, in Sections 1.4.4 and 1.4.5, I investigate the Arabian inscriptions written by men who called themselves ‘king of the ‘rb’.

1.4.4 Late Antiquity and the Case of Imru’ al-Qays

During Late Antiquity, the Eastern Roman Empire became the most flourishing centre of the Mediterranean world, including parts of Italy and southern Spain at the height of its expansion, as well as the Balkans, the north coast of Africa, the Anatolian plateau and the Levant. The rest of the Middle East was dominated by the Sasanian Empire (224–651), which boasted of ruling over a series of shahr (lands), including Arabia.Footnote 160 As Christianity gained ground with the Roman emperors, renewed hostilities broke out between Rome and Iran. The outbreak of these hostilities had important repercussions on the Arabian Peninsula, as demonstrated by an inscription dated 328 found at the Roman outpost of Namārah, a semi-permanent water reservoir in southern Syria. Written in Arabic using the ‘transitional’ script, this inscription is the epitaph of Imru’ al-Qays ibn ʿAmr, king of the Iran-allied Naṣrids, who flourished between the fourth century and the beginning of the seventh century in southern Iraq. The epitaph defines Imru’ al-Qays as ‘king of ʿrb’ (mlk al-ʿrb) but also as leader of the ʾAsd and Madhḥij tribes whom he conquered during a military campaign to Najrān. Both groups inhabited the southern fringes of Central Arabia, roughly corresponding to the territory between the Najd and the South Arabian kingdoms (Saudi Arabia-Yemen border). While the ʾAsd occupied the ʿAsīr region,Footnote 161 the Madhḥij were located further south.Footnote 162 Both groups were independent until Imru’ al-Qays’ expedition, as proven by a Sabean inscription providing a political map of third-century Arabia.Footnote 163 These people were probably threatening the surrounding empires after perfecting the use of the saddle in the third century.Footnote 164

Although it is curious that the epitaph of a Naṣrid king was found not far from the Limes Arabicus of the Roman Provincia Arabia, the fourth line of the inscription states that Imru’ al-Qays was appointed phylarch by the Romans,Footnote 165 hinting at the possibility that Imru’ worked for both powers. Contemporarily, the Roman Emperor Constantine ‘extended his Empire in the extreme south as far as the Blemmyes [in Nubia] and the Aethiopians’,Footnote 166 intending to counterbalance the Iranians’ swift expansion in Arabia by strengthening Rome’s position in the Red Sea.Footnote 167 The recruitment of Imru’ al-Qays complimented Constantine’s expansionist policy, the Roman emperor being fascinated by and desiring to emulate the ‘great giants’ of the classical period.Footnote 168 As suggested by his biographer Eusebius, he also wished to promote Christianity in ‘pagan remote lands’ (d. ca. 339).Footnote 169

Although Imru’s epitaph is an important historical document and a clear testimony of an increasing interest in Arabia on the part of the Roman Empire, it is not the first epigraphic evidence written by a ‘king of the ʿrb’. Rulers of ‘rb are mentioned in a group of inscriptions from Edessa (Urfa, Turkey) dated to around 165,Footnote 170 and in another dated ca. 180 from Hatra (Iraq),Footnote 171 possibly reflecting a hegemonic role gained in the Roman–Iranian wars of 163–6. In this corpus, ‘rb here probably refers to a territory and not a community.Footnote 172 Accordingly, as the ‘rb were not the main people these kings ruled over but only subsidiary populations, Imru’ al-Qays’ inscription appears even more significant. Based on the references in Hatran and Old Syriac inscriptions and some linguistic considerations, Michael Macdonald has proposed that ʿrb in Imru’ al-Qays’ epitaph refers to ‘one or more of the areas in the Jazīra and other parts of northern Mesopotamia’.Footnote 173 Considering that Imru’ al-Qays’ inscription was found in southern Syria and that he conquered the ʾAsd and Madhḥij tribes (the former found in the Ḥijāz and the latter on the southern fringes of Central Arabia), it is more likely that the ʿrb inhabited the area between modern southern Syria and Yemen.

Other inscriptions, written in Greek and Latin, have been found in Namārah.Footnote 174 Imru’ al-Qays’ epitaph, written on a beautifully carved tabula ansata, showed his strong connection with Rome, which gave him prominence in the Arabian political milieu. Before Imru’s epitaph, no inscription of this kind had been found in the north and central regions of the Arabian Peninsula. Rome’s cultural influence played an important role in shaping the modalities of power in the area, as later shown by the case of the Jafnids (see Chapter 5). Although other ʿrb kings preceded Imru’ al-Qays, it was only under Rome’s cultural wing that Arabians started framing their historical memory in such a grand fashion. At the same time, the existence of independent millennial civilizations in the south of the peninsula significantly contributed to the acceleration of the Arabians’ process of self-identification.

1.4.5 The Epigraphic Evidence from South Arabia

Several South Arabian inscriptions mention the ʾʿrb and the ʿrb/ʿrbn before and after the unification of South Arabia at the end of the third century under the kingdom of Ḥimyar (Tables A.1 and A.2). One century after the region’s unification, a conspicuous group of monumental inscriptions attest to the new Ḥimyarite title ‘king of ʾʿrb’.Footnote 175 The most ancient of these inscriptions are attributed to Abīkarib Asʿad (ca 400–45), ‘king of Sabaʾ, dhu-Raydān, Ḥaḍramawt, Yamanat and his/the ʾʿrb of Ṭwdm and Thmt’.Footnote 176 Thmt probably indicates the coast of western Arabia between Mecca and Medina (ancient Yathrib), while Ṭwdm indicates the Najd.Footnote 177 One of Abīkarib Asʿad’s royal inscriptions written with his son celebrates the possession of the land of Maʿadd in Central Arabia with the agreement of ‘their ʾʿrb of Kindah, Saʿd, ʿUlah and H[…]’, all inhabiting the southern fringes of Central Arabia.Footnote 178 At the same time, a ‘Ḥujrid son of ʿAmr’ styled himself ‘mlk (king) of Kiddat’, though Kindah was part of Ḥimyar.Footnote 179 A century later, king Maʿdīkarib Yaʿfur (r. 519–22) identified as ‘their ʾʿrb’ both the tribes of Kindah and Madhḥig in the southern fringes of Central Arabia and the Banū Thaʿlabat and Muḍar, found in the northern edges.Footnote 180 After a ten year gap, King Abraha (ca 535–65) readopted the royal title following his return from the land of Maʿadd,Footnote 181 where he took possession of regions in North and Central Arabia (Table A.3).Footnote 182 In another monumental inscription, Kindah, ‘Ulah and Saʿd are described as allies of the Ḥimyarite king.Footnote 183

Overall, the twelve groups identified as ʾʿrb in the corpus inhabited different areas of the Arabian Peninsula, from Palestine to Yemen. An inscription written under ruler Yūsuf mentions ‘the tribe of Hamdān and their hgr and their ʿrb, and the ʾʿrb of Kindah, Muḍar and Madhḥig’ found in Central Arabia.Footnote 184 As Hgr means ‘city’,Footnote 185 hgr and ʿrb seem to be in contrast, meaning ‘citizens’ and ‘nomads’.Footnote 186 Furthermore, the lexemes ʾʿrb and ʿrb appear together only in a few South Arabian inscriptions (Table A.4).Footnote 187 Jan Retsö has suggested that ʾʿrb refers to a South Arabian group dependent on the Ḥimyarite Kingdom while framing the collective ʿrb(n) as independent political entities living between Najrān and Jawf.Footnote 188 In other words, ʿrb(n) indicate outsiders who were never conquered by South Arabia, while the ʾʿrb are Ḥimyar’s allies. Much like the Neo-Assyrian Ar-ba-a-a and A-rib-bi there could be a semantic distinction between ʿrb(n) and ʾʿrb. As the lexeme ʿrb(n) is in contrast to hgr, ‘citizens’ or ‘sedentary’,Footnote 189 ʿrb(n) might have been nomads/Bedouins. And indeed, it is possible that the ʿrb(n) were independent entities associated with larger communities.Footnote 190 The lexeme indicated people with nomadic ways of life, in contrast with the ʾʿrb allies.Footnote 191 Significantly, as previously suggested by the classical sources, the South Arabians of Arabia Felix, with their millennial civilization, did not view themselves as Arabs/Arabians. At the same time, those who were labelled ʾʿrb did not consider themselves to be Arabs either.Footnote 192

Table 1.1 ʿrb(n) and ʾʿrb in South Arabian inscriptions

Lexeme | Relation with Ḥimyar | Possible meaning | E.g., South Arabian mentions |

|---|---|---|---|

ʿrb(n) | Independent | Nomads ≠ hgr(n) ‘sedentary’ (lit. ‘inhabiting cities’) | FB-al-ʿAdān 1: ‘the wars and the razzias of the ʿrbn of the region of the East’ |

ʾʿrb | Dependent | Allies, appearing in the royal tituli | MAFRAY-al-Miʿsāl 4: ‘ʾʿrb who were in the town of Shabwa’ |

1.4.6 Qur’ān

In the Qur’ān, the root ‘-r-b is used to indicate either the language of the Muslim Holy BookFootnote 193 or a group of people.Footnote 194 The authors of the classical Tafsīr al-Jalālayn and Tanwīr al-Miqbās min Tafsīr Ibn ‘Abbās interpret the a‘rāb of Q. 9.99 (‘among the al-a‘rāb, there are some who believe in Allāh and the Last Day’) as the Medinan tribes of Juhayna and Muzayna.Footnote 195 In contrast, with regards to Q. 9.101, the al-a‘rāb are referred to as munāfiqūn (‘hypocrites’), that is, according to the first tafsīr, the tribes of Ashja’, from the Najd tribe Ghaṭafān, and the Ḥijāzī Banū Ghifār and the Ghaṭafān, while they are referred to the Banū Asad in the second tafsīr). All these groups inhabited North and Central Arabia during Late Antiquity. While Juhayna and Muzayna quickly embraced Islam, the other groups were hostile towards Muḥammad at the beginning of his career as a prophet. Therefore, the Qur’ānic root ‘-r-b did not point to a homogeneous community but to different peoples who shared the geographical boundaries of Medina, where the suwar were first revealed to the prophet.

1.4.7 Notes on Ethnicity and Conclusion

The root ‘-r-b indicates groups of people but also means ‘offering a sacrifice’ and ‘squared stones’.Footnote 196 These meanings are attested in all Semitic languages,Footnote 197 and Gəʿəz.Footnote 198 West, steppe and ‘mixed people’ are also possible semantic explanations of the lexemes Arabia and Arabs/Arabians, thus suggesting that the word did not originate as self-identification. This is especially evident in the case of ‘west’ as it implies its use by someone ‘at the east’ (e.g., Sargon, whose seat was in Dur-Sharrukin in Iraq). I will now offer some brief reflections on the concept of ethnicity before drawing a conclusion on the identification of the ‘Arabians’ of pre-Islamic Arabia.

In a recently published paper, Ahmad al-Jallad introduced two new Safaitic inscriptions (part of the Ancient North Arabian corpus) containing the lexeme ʿrb, claiming that the term was an endonym ethnicon broadly referring to the tribes inhabiting the desert region in the Ḥarrah.Footnote 199 Nonetheless, as the same author acknowledges, the production of Safaitic inscriptions is the only tangible cultural thread connecting the people of the Ḥarrah.Footnote 200 The amount of evidence needed to claim that the lexeme ʿrb is an ethnicon is arguably insufficient, so the hypothesis is not entirely convincing. Moreover, the presence of ʿrb in various regions in Arabia, and not just in the circumscribed area where these two inscriptions were found, further weakens al-Jallad’s position. Certainly, if ʿrb were indeed an endonym ethnicon, it is more probable that it referred only to some and not all ʿrb.

There are apparent impediments to applying modern categories, such as ethnicity, to Antiquity. Today, ethnicity usually refers to group identity based on shared culture, traditions and customs. As pointed out by Walter Pohl, ethnic identity ‘is not an inherent quality’ but the consequence of ‘acts of identification and distinction’.Footnote 201 Consequently, an ethnic group and its symbols must be ‘recognized from the outside’.Footnote 202 For Herodotus, ethnos indicated a group viewed as a geographical, political or cultural entity, while genos, from the verb ‘to be born’, was used to define groups whose members were related by birth.Footnote 203 In the Hellenistic Egyptian usage, Hellenes, Persians and Arabs were described as ethnē, but so were groups such as beekeepers and prostitutes.Footnote 204 During Late Antiquity, identities ‘only existed through efforts to make them meaningful’.Footnote 205 In this particular historical period, identities needed to become less defined, more blurred and increasingly adaptive to accommodate necessarily fluid loyalties caused by the rapidly changing fortunes of the kings of the time, as exemplified by the case of the Frankish of Visigothic kings.Footnote 206 ‘Essential religious values’ thus linked subjects and rulers, as well as individuals and society.Footnote 207

Although Roman literary sources often tend to frame the pre-Islamic inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula as one group, the Arabians differed in traditions, languages and customs. Indeed, there is not one easily distinguishable feature that ‘held’ the Arabians together and allows us to use the term ‘Arabs’ when referring to pre-Islamic times. This is, of course, not to say that an ethnic group cannot have a mixed background or that ethnicities are biologically transmitted or immutable, rather that, if ethnicity is a social construct, the ‘sociality’ of the Arabs only emerged following the rise of Islam, as the various polities of Arabia perceived each other as ‘foreign’ and ‘other’ based on lineage and culture, in particular of language and faith. As Rachel Mairs puts it in her recent book on what she defines as the ‘Hellenist Far East’, ‘what is important in the construction of an ethnic group and the maintenance of its boundaries is not that a group have any objective common culture but that groups take aspects of their cultural toolkit and invest these with ethnic significance’.Footnote 208 Accordingly, they were simply ‘Arabians’, bounded by shared geographical space, namely, the Arabian Peninsula. Among these Arabians, multiple ‘ethnicities’ are distinguishable. As already suggested in 1896,Footnote 209 Arabness is a notion that became distinguishable only after the establishment of the Muslim community, when a cultural identity was shared by the fragmented tribal societies of the future world conquerors.Footnote 210

At the end of the last century, Michel Gawlikowski suggested reading the Assyrian Aribi as indicating ‘un mode de vie’, namely that of the nomads.Footnote 211 In more recent years, Macdonald has suggested that the term ‘Arabs’ originated as a ‘self-designation based on recognizing an ill-defined complex of linguistic and cultural characteristics’.Footnote 212 However, this view does not explain why the Assyrians did not use the existing Assyrian terms meaning ‘nomads’.Footnote 213 At the same time, it is questionable to claim that shared cultural characteristics existed among all the various groups labelled as ‘Arabs’. Jan Retsö has instead suggested that ‘Arab’ ‘designates a community of people with war-like properties, standing under the command of a divine hero, being intimately connected with the use of the domesticated camel’,Footnote 214 but evidence to support this claim is also scant.

Intending to define more precisely the scope and the horizons of this book, the present section has shown how pre-Islamic sources mention the ‘Arabs’ as the inhabitants of the northern and central parts of the Arabian Peninsula. A distinction between the ‘rb allied with the southern kingdom of Ḥimyar and the independent Bedouins in the same region demonstrates the difficulty of generically classifying the communities living between the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf as ‘Arabs’. These people did not possess a distinguishable culture; they did not share a common lifestyle and did not have a common religious creed until the rise of Islam. Even if they did speak one common language, their ‘linguistic label would not determine their ethnic identity’, as studies have highlighted in the similar possibly shared linguistic case of the Huns and the Avars.Footnote 215

Although shared ethnicity is arguably apparent in a community characterized by (some degree of) homogeneity of culture and shared territory, ethnicity is a ‘system of distinctions that allows defining social groups in relation to each other’.Footnote 216 Therefore, ethnic identities can change through time and space as ethnicity, from the ancient Greek ethnos ‘nation’, is mostly a practice in process. Thus, I have argued that the connection between the ‘Arabs’ found in the sources mentioned earlier is purely geographical. These people dwelled in Central and North Arabia but belonged to different tribes, each of which more than likely had different and distinguishable cultural heritages. Hence, it is preferable to use the geographic term ‘Arabians’ to the ethnic term ‘Arabs’ when discussing the inhabitants of pre-Islamic Arabia.Footnote 217 Use of words such as ‘Saracens’, instinctively used by students of Rome and Iran,Footnote 218 suggests an approach based on an ‘external standpoint’ and should be similarly disregarded.

While the multicultural Huns and the Xiongnu established their identities on political rather than ethnic grounds, the Arabians forged their own identity after Muḥammad’s prophetic career on the grounds of one faith and the one language of its sacred text. However, as Islam had universalist claims just like Christianity, the term ‘Muslim’ soon became an ethnicon used as a term of self-identification, while ‘Arab’ was rarely self-applied and emerged only after the military success of the ‘Muslims’. According to Amartya Sen, ‘religion is not, and cannot be, a person’s all-encompassing identity’.Footnote 219 Nonetheless, it is a fact that ‘Arabness’ became closely connected to ideas in the Qur’ān and, in particular, to its ‘Arabic language’ (lisānan ʿarabīyan).Footnote 220 After the rise of Islam and the creation of the Caliphate, Arabic became the tool to record pre-existing oral poetry and historical narratives, laying the foundations for the ‘Arab’ and ‘Muslim’ genealogy. Building on George Ostrogorsky’s description of the ‘Byzantines’,Footnote 221 the ‘Arabians’ became Arab, Arabic-speakers and Muslims simultaneously due to the first Muslim conquests. Yet, as Islam expanded outside of Arabia, the ‘Arab’ (and ‘Arabic-speaker’) and ‘Muslim’ identities became increasingly independent of one another, with the progressive detachment of the Arab ethnicon from its religious component. Similarly to the disjunction of the Roman and Christian identities after the ninth century,Footnote 222 the label ‘Arab’ was gradually abandoned to include the ‘other’ people of the Caliphate. Indeed, although Muḥammad’s movement originated in the Arabian Peninsula, the empire which emerged from it became increasingly defined as ‘Muslim’ and much less commonly as ‘Arab’.Footnote 223 This empire, with its several capitals, soon located outside the peninsula and forged its identity by imbibing the eclectic cultures of its subjects, especially the Iranian culture, bestowing ‘in exchange’ Islamic patronage and citizenship. As ethnicities are not biological entities, in the heyday of the Muslim Commonwealth, one could become an ‘Arab’ through a process of integration and acculturation by converting to Islam, learning Arabic and adhering to the customs and laws of the Caliphate.

In the early twentieth century, Ostrogorsky defined the ‘Byzantines’ as simultaneously Roman, Greek and Christian.Footnote 224 More recently, Anthony Kaldellis has argued that the Romans of Byzantium were an ethnic group and that the ‘core national state’ of Romanía was not an empire but had an empire.Footnote 225 Disputing the ‘monstrously inverted riddle’ which saw the Roman Empire as the only empire in history ‘about which it was possible to identify ethnic minorities but not the majority’,Footnote 226 Kaldellis also suggested that before the ninth century, ‘Roman’ and ‘Christian’ referred to ‘complementary identities of the same group of people’.Footnote 227 It could be argued that as Islam ‘created the Arabs’ through the spread of the language of the Qur’ān, it also ‘overcame the Arabs’ after the fall of the Caliphate. Thus, we would never refer to contemporary Malaysian Muslims as ‘Arabs’ (Islam became the majority religion for the Malays in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries after the fall of the Caliphate, but Arabic never substituted Malayan as an official language). Of the twenty-two countries which are today part of the Arab League and constitute the ‘Arab world’, only six are found in the Arabian Peninsula (three more, namely Bahrain, Jordan and Syria, are found in its northern extension). These countries share one official language, Arabic, but much like the tribes of pre-Islamic Arabia, they possess different cultural heritages. The history of Arabia is not the history of Islam or vice versa. Similarly, the history of the Arabs is neither the history of the Arabians nor that of the Muslims. Since the end of the first millennium, when Islam attained ‘intellectual and institutional maturation’,Footnote 228 the great majority of the Arabs viewed themselves as belonging to one community, built around one faith, Islam, and with one language, Arabic. However, this was certainly not the case in pre-Islamic Arabia.