The parable of the blind men describing an elephant exists in numerous versions. The poet Rumi (1207–73) gives the following:

Some Hindus have an elephant to show.

No one here has ever seen an elephant.

They bring it at night to a dark room.

One by one, we go in the dark and come out

saying how we experience the animal.

One of us happens to touch the trunk.

‘A water-pipe kind of creature.’

Another, the ear. ‘A very strong, always moving

back and forth fan-animal.’

Another, the leg. ‘I find it still,

like a column in a temple.’

Another touches the curved back.

‘A leathery throne.’

Another, the cleverest, feels the tusk.

‘A rounded sword made of porcelain.’

He’s proud of his description.

Each of us touches one place

and understands the whole in that way.

The palm and the fingers feeling in the dark are

how the senses explore the reality of the elephant.

While the point of Rumi’s poem is the candle – the divine light that would grant view of the ‘reality of the elephant’ – one can read the parable also in light of Roman Jakobson’s distinction between metaphor and metonymy. According to Jakobson, metaphor is based on a ‘metalanguage’ that constitutes clear meaning, while metonymy is based on contiguity and therefore highlights the partial, fragmented and specific material quality.Footnote 2 The describers in the dark have no metalanguage available to them in this parable; they must describe the elephant through metonymy, or ‘synecdochic details’ that never grow into a coherent comprehensiveness.Footnote 3

Homi Bhabha, who has discussed the political implications of Jakobson’s theory, adds that metaphor foregrounds a totalizing, unifying perspective, while metonymy allows for ‘political subversion’ through ambivalence and ambiguity.Footnote 4 In this sense, the distinction can be helpfully applied to theatre/performance historiography: like the describers in the parable, we lack a wholistic view of our object, remaining instead bound to bits and pieces for our analysis. Max Herrmann (1865–1942), one of the founding fathers of German Theaterwissenschaft (theatre studies), offered as early as 1914 an interesting insight in this regard: ‘If theatre history shall become a discipline in its own right, it must have its particular methods. The talk of methods – which has gained some traction among younger scholars, for example in literary history – has gotten on the nerves of some senior companions.’Footnote 5 Notwithstanding that ‘talk of methods’ has gained little popularity in the last 110 years, Herrmann’s observation that Theaterwissenschaft can be constituted as a field only through methods and methodology – and not through reference to an overarching set of traits – is still apropos. In Jakobsonian terms, the mercurial quality of theatre/performance does not allow for a fixed ‘metalanguage’, but rather calls for metonymic efforts to describe the fragmented specificities we are dealing with.

The concept of critical media history, as suggested by Tracy C. Davis and myself, tries to address this question from the opposite end: neither theatre nor performance is historically and trans-culturally a given; rather, they both develop in constant interrelation to neighbouring practices and cultural contexts.Footnote 6 This perspective does not lead to infinite arbitrariness as has been suggested, but rather helps us understand how performance is utilized by societies to organize various forms of presentation and reception. Theatre and performance history entails, then, not merely excellent achievements but also the cultural process of negotiating different forms.

This approach highlights processes of formation and transformation, with performance being a mode of perception whose profile is defined vis-à-vis that of other comparable forms, allowing us to describe these phenomena and gain an understanding of the historical semantics as well as the practices of a larger media ecology.Footnote 7 The idea of critical media history is thus founded not on a metalanguage but on a dynamic triangulation of modes of perception (aisthesis), material conditions and their composition (apparatus), and practices.Footnote 8 The focus of critical media history is thus less on the single artistic achievement or on aesthetic processes per se, and more on the collective imagination and its ability to inform the actions and thoughts of a society.

It is in this sense that I will offer a metonymic reading of the elephants in the room of early modern Europe, following the scattered, fragmented, accidental traces of these beasts in the material reality but also in the collective imagination.

A fragmentary start

Browsing through the extensive diaries of the Cologne magistrate Hermann von Weinsberg (1518–97), I stumbled across the entry of 10 October 1563. On this day,

An elephant, an enormous beast, was in Cologne and laid at the Torenmart in the ‘Wild Man’ Tavern with his attendance. King Philip of Spain is said to have sent it to the Emperor Ferdinand. They have let it go back and forth through Cologne. A small boy, vested in yellow clothes, sat on it and directed it with an iron instrument – it obeyed him. It went as fast as a human being might run – and people say that for more than seventy years no elephant has been in Cologne … Later, it went away by ship, I have seen twice or thrice.Footnote 9

The strange beast – clearly alien to the early modern Rhineland – turns Weinsberg into one of the blind describers, testing different registers to grasp the unusual sight. The most immediate way of measuring it is by comparison to familiar beings: its height (‘as a man could stretch’), breadth (‘as two horses’), and speed (‘as a human being might run’). But this scale turns the elephant into merely an overpowering presence: too high, too fast, too strong.

The second level of comparison is cross-cultural, with a focus on the ‘alien’ qualities of the animal and its appearance: the small, yellow-vested boy invokes the stereotype of saffron clothing associated with the Indo-Asian context. The detail of the small iron instrument (iseren instrumentgin) – an ankus – by which the boy directs the elephant completes the image of the mahout that Weinsberg references here.Footnote 10 Clearly, the elephant is extraordinary not only ontologically (far exceeding the human scale, in the literal sense of the word), but culturally as well. Also of note here is that the elephant lodges near the Wild Man Tavern, whose name invokes precivilized, mythical beings that populated the collective imagination and carnivalesque traditions all over Europe.Footnote 11 That Weinsberg’s description puts the beast and its entourage in proximity to these mythical creatures gains a symbolic dimension if we read his scene as placing the experience in his town – that is, in his cultural context. Two ciphers of liminality are combined here in one image.

On a third level, Weinsberg explains the pragmatic or political implication of the beast in the strange environment: it is a gift of King Philip II of Spain (1527–98) to Emperor Ferdinand I (1503–64), his uncle. The two men represented different branches of the House of Habsburg. Philip’s choice of an elephant as a diplomatic gift is in line with global practices in these days, but more than that, it also represents his claim to be a global power. The transport of such an enormous animal, across the seas and across the landmass of northern Europe all the way to Vienna, is an impressive demonstration of his claim to a power unbounded by geographic or political borders, a claim that is buttressed by his motto, Non sufficit orbis (the world is not enough). And yet Weinsberg’s entry makes clear that for him the elephant is not merely another metaphor for the Habsburgs’ claim to power: it is a spectacle that cannot be reduced to such a single meaning.

Weinsberg relates his immediate experience to historical knowledge of the Cologne community: ‘people say that for more than seventy years no elephant has been in Cologne’. Indeed, the Koelhoffsche Chronik notes for the year 1482 – eighty-one years before Weinsberg’s account – that an elephant was on display in Cologne. This animal was on its way to England but drowned during the passage in the North Sea, and it never reached the British Isles.Footnote 12 Weinsberg’s reference to earlier elephant sightings is revealing: while the beast evades simple classification or recognition, it holds a firm position in his world view. It represents the familiar unknown – a paradoxical position that is only possible because of the intrinsic theatrical and performative character of the elephant in this environment. The literal ‘elephant in the room’ is a challenge to categories of perception and description.

Weinsberg’s anecdotal description is complemented by a 1563 broadside from Antwerp that depicts the very same elephant and its marches through the city (Fig. 1). In the centre of the multicoloured broadside is the massive grey animal, covered with a white, yellow and red checkered blanket, and wearing a collar with small bells that probably added an attention-grabbing sound to each step. On its back sits a man with a dark complexion – described as a ‘moor’ in the accompanying text. The mahout is holding up a large stick that lacks the characteristic hook of the iconic ankus, and while he wears the yellow clothes described by Weinsberg, he is also outfitted in a red cloak and hat, in the European fashion. In its physical size and appearance, the impressive animal dominates the sheet and the depicted human beings. And yet there is no doubt that it is tame and under control.

Fig. 1 Broadside from Antwerp, 1563, depicting the landing and march through the city of the elephant described by Weinsberg. With permission of the British Museum, London, UK.

The scene of its march through Antwerp is less controlled than the animal. While two women are depicted as simply observing the animal from their window, the crowd around the animal is less disciplined. Some touch it or seem to hit it on the rump; others pull its tail. The artist tried to capture the action by depicting only legs and feet beyond the elephant, hinting at the unruly behaviour of a man who has toppled over and seems to have landed dangerously close to the elephant’s foreleg. We can easily imagine that the scenes in Cologne were similar to what is depicted here.

The broadside focuses almost entirely on the spectacular dimension of the event, although the political framing is indicated in the text: ‘So ben ic te Land na den Keyser ghegaen’ (‘Thus, I went onto the land to march to the emperor’). The anonymous elephant’s itinerary marks the outlines of the Habsburg empire – coming from India or Sri Lanka through Lisbon to Antwerp and marching on to Vienna. Colonial ambitions are present here, and could potentially be felt by the amazed audiences in the European cities the elephant passed through. The image of the broadside allows us to recognize the intrinsic theatrical quality of these animal appearances in early modern Europe.

Making sense of the performing elephant

But the spectacle of elephants in early modern Europe differed significantly from the presentation of other wild beasts in the menageries of the day. Elephants were not merely ‘new to the eye’, or creatures whose wildness caused fear and lust as lions, tigers and panthers did (we might think of Bottom’s wish to ‘play the lion too’).Footnote 13 The fascination of the elephant and its ‘nature’, or rather its ontological status, ran deeper. In the recent context of animal studies, scholars have discussed the status of the performing animal. Lourdes Orozco, for example, argues that animals in a theatrical context raise questions about both ontological status and theatrical framing:

In performance, animals raise questions about the status of both the human and the animal and about the relationship between the two. They transform theatre’s relationship with representation by appearing as a real presence onstage; they challenge its meaning-making process and invite reassessment of the ways in which theatre is produced, received and disseminated.Footnote 14

Una Chaudhuri has introduced the term ‘zooësis’ to describe the specificity of this constellation:

My own term for this phenomenon is zooësis, intended to refer broadly and comprehensively to the discourse of species in art, media, and culture. The term echoes both Platonic poesis and Aristotelian mimesis – both commonly used in literary and dramatic theory to designate modes of construction and representation … Zooësis (from the Greek zoion = animal) refers to the ways the animal is put into discourse: constructed, represented, understood, and misunderstood.Footnote 15

Orozco and Chaudhuri emphasize that the performance act itself is not merely an assertive repetition of a previously fixed meaning but rather the opening of a field to negotiate these meanings. Although their theory is rooted in the post-deconstructivist twenty-first century, it might be even more relevant in the early modern period, a time when the presentation of elephants and other animals was considered part of the theatrical spectrum.

A hint to elephants’ place in the broader theatrical realm can be found in a 1652 image from Nuremberg by Peter Troschel (1615–80), depicting the Fechthaus (fencing house). This building was opened in 1628, providing a space for all sorts of performative and spectacular activities, as Troschel notes under his sketch: ‘Palestra ubj ludi gladiatorij et scenici celebrantur’ (‘Gymnasium where gladiatorial and scenic games can be performed’). This multifunctional space hosted tightrope walkers (whom we see in Troschel’s sketch), acrobats, jugglers and animal baiting, but also the performances of the English comedians who had regularly visited Nuremberg since the sixteenth century. Offering space for about 3,000 spectators in its galleries, it was very similar to London’s public playhouses.Footnote 16 This empty space embodies the diversity and complexity of early modern media ecology. Thus it is even more significant that this space – deliberately devoid of any decor – showed on one side of the ground floor a mural of two elephants, complemented with the dates 1520 and 1629, commemorating the public spectacle of elephants in NurembergFootnote 17 (Figs. 2, 3).

Fig. 2 View of the Nuremberg Fechthaus by Peter Troschel after Johann Andreas Graff (c.1652). With permission of the Theaterwissenschaftliche Sammlung, University of Cologne, Germany.

Fig. 3 Detail of the Fechthaus by Troschel, showing life-size images of elephants, remembering earlier presentations in Nuremberg. With permission of the Theaterwissenschaftliche Sammlung, University of Cologne, Germany.

But if the painted wall reveals the presence of elephants, it is silent about the process of zooësis itself, the ‘making sense’ of the performative appearance. For this, we must turn to the printed material that accompanied the presentation of elephants. Many of these broadsides and booklets not only offer visual representations and descriptions of the elephants’ physical appearance, but also highlight their skills and their resonances with the human.Footnote 18 Apart from typical acts of dressage such as kneeling and turning around,Footnote 19 they show acts that were human or even part of courtly life, such as fencing, pistol shooting and dancing (Fig. 4). Ogier Ghislain de Busbecq (1522–92), ambassador of Karl V to the Sublime Port, for example, marvels at a dancing elephant:

I saw also a young elephant which could dance and play ball most cleverly … Is it more wonderful than the elephant which, Seneca tells us, walked on the tight rope, or that one which Pliny describes as a Greek scholar? … When the elephant was told to dance, it hopped and shuffled, swaying itself to and fro, as if it fain would dance a jig.Footnote 20

Fig. 4 Broadside of an elephant, 1630, by Jeremias Glaser. In the background, one can see the various acts of the elephant, such as fencing, waving a flag and firing a pistol. With permission of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, Germany.

Clearly, perceptions of the elephant were not only based on sight and visual observations but also rooted in the symptomatic, early modern way of ‘making sense’. A juxtaposition of empirical observations and detours into philosophy, theology and scriptures from antiquity onwards can also be found in the pamphlets of performing elephants. Alongside detailed descriptions, we find references to the Western intellectual tradition.Footnote 21

This tradition foregrounds what we might call the paradox of the performing elephant: while its gestalt surpasses all human measurements, as Weinsberg also noted in his diary, the elephant does not become the dreadful, monstrous other but is rather considered to be the animal that is closest to human beings. Pliny the Elder, the long-referenced and rarely disputed authority on the natural world, writes at the beginning of his chapter on elephants in the Naturalis historia,

The elephant is the largest of them all, and in intelligence approaches the nearest to man. It understands the language of its country, it obeys commands, and it remembers all the duties which it has been taught. It is sensible alike of the pleasures of love and glory, and, to a degree that is rare among men even, possesses notions of honesty, prudence, and equity; it has a religious respect also for the stars, and a veneration for the sun and the moon.Footnote 22

Pliny sets the tone for a discourse that reads the elephant as a human being – despite or maybe because of its outward appearance, which seems to be far remote from human features. Thus, interior qualities such as humour, intelligence and generosity become the hallmark of the Western zooësis of the elephant.

In the early modern period, this line of interpretation resonated with more general questions about subjectivity, the nature of human beings and religious interpretations of the world. Within Western discourse, the Reformation had led to a shift in the conceptualization of subjectivity, but an increasing number of encounters across Africa, Asia and the Americas had disturbed the assumptions of the Western Weltbild.

The French writer Michel de Montaigne (1533–92), hailed for his programmatic scepticism in his Essais (1572–92), picks up an anecdote from Pliny about elephants praying by holding their trunks towards the sun. For Montaigne, this scene becomes a moment to reflect on the ontological distinction between human beings and animals:

By which we may judge, and conclude, that Elephants have some apprehension of religion, forsomuch as after diverse washings and purifications, they are seene to lift up their truncke, as we doe our armes, and at certaine hours of the day, without instruction, of their owne accorde, holding their eies fixed towardes the Sunne-riding, fall into a long meditating contemplation: yet, because we see no such apparance in other beasts, may wee rightly conclude, that theay are altogether voyde of religion, and may not take that in payment, which is hidden from-us.Footnote 23

The uncanny proximity of elephants and human beings gives way to rather obscure legends as well: Caspar Schott SJ (1608–66) refers to tales of a young boy born with an elephant head; he even includes a picture of the boy in his Physica Curiosa (1662).Footnote 24 But Schott does not simply come late to the discourse; his depiction of the Chimera (which might have resonated with travelogues describing the Indian god Ganesh) is rather indicative of an emerging divide brought about by modern science and its practice of classification. This modern biological classification draws new lines between the species, establishing new relationships while sharpening other distinctions.

Show of force: elephants, war and violence

In contrast to the ambivalent ontological status of elephants, their potential as weapons has been vividly captured in the Western imagination since the time of antiquity, from the story of Semiramis and her war against the king of India to that of the Carthaginian king Hannibal and his war against Rome (218–201 BCE).Footnote 25 Marching his elephants over the Alps, Hannibal was met with the cry ‘Hannibal ante portas!’ (‘Hannibal at the gates!’) – expressing horror not only at the physical stature and strength of the elephants, but also at the invasion of the ‘Other’ into European territory.

A sort of antidote to this traumatic narrative is the episode of Alexander the Great defeating (and then sparing) the Indian king Porus (326 BCE), despite his mighty war elephants. This episode became a popular motif in opera libretti and beyond, inspiring, for example, a scene designed by Lodovico Burnacini (1636–1707), set designer and stage engineer at the Imperial Court in Vienna (Fig. 5). This scene, which also circulated as a coloured etching, depicted Porus marching out to fight Alexander. The design deployed the full arsenal of the baroque stage, including flying allegorical figures (Hatred, Wrath and Confusion), with three (artificial) war elephants appearing centre stage, marking the power and cultural alterity of Porus. This scene, which was staged in Vienna in 1678, was not part of an opera; it was created to celebrate the birth of the heir apparent to the emperor Leopold I (1640–1705). It was titled La Monarchia Latina Trionfante (The Triumphant Roman Monarchy).Footnote 26

Fig. 5 Scene design by L. Burnacini, for the allegorical play La Monarchia Latina Trionfante, Vienna, 1678. The war elephants march prominently in the centre of the picture. With permission of the Theaterwissenschaftliche Sammlung, University of Cologne, Germany.

In the scene, Porus – along with his army of elephants, camels, Amazons and warriors in fancy costumes – is led by winged allegorical figures representing Error and Irrationalism, only to be brought to heel by the superior forces of Alexander, here representing the House of Habsburg and the imperial court. Librettist Antonio Draghi (1634–1700) and Burnacini turned the plot into an allegorical scene intended to celebrate the House of Habsburg and to claim Western supremacy. Even as the emperor is celebrated as ‘La Monarchia Latina’, the elephants conjure the horror of Hannibal and the defeat of Rome. Thanks to the amalgamated plots – Alexander and Hannibal – the Carthaginian trauma becomes a glorious and heroic triumph.

This act of self-aggrandizing happened at a rather precarious moment historically; only five years after this scene premiered, the Ottoman army would besiege Vienna. While the Ottomans did not come with elephants, the fictious, orientalized Indian army in Burnacini’s sketch represents a more general type of threatening cultural alterity, one that certainly included the phantasma of a Muslim army standing at the gates of Vienna.

Such theatrical fantasies resonate with the numerous travelogues from India that bristled with reports of the riches of the Mughal court. Elephants became the epitome of this overabundance. Niccolò Manucci (1638–1717), the notorious chronicler of Mughal India for European audiences, gives an interesting description of the elephants at the Mughal court of Shah Jahan (1592–1666):

The stables of the Emperor [Shah Jahan] are suitable to the number of his cavalry, and are filled with a prodigious multitude of horses and elephants. His horses, it is said, are in number nearly twelve thousand … The elephants of the Emperor form also a considerable accession of strength to his army, and an ornament to his palace. As many as five hundred are fed and lodged under large porches, built expressly for them. The Mogul bestows upon them very majestic appellations, and such as are appropriate to such prodigious animals … These elephants are trained equally for hunting, and for war. They will attack lions, and tigers; and it is by such exercises that they are familiarised to carnage. The manoeuvres, especially, by which they are taught to force the gates of cities, has something in it extremely military.Footnote 27

It was not only the sheer number and extravagant equipment of these animals that appealed to Western audiences, but also the implication of them as a kind of superweapon. Training these animals – which in the European imagination were most humanlike in their nature for combat and ‘carnage’ – meant having a unique command over them. Western illustrations depict the magnificence of the Mughal court, with the usage of elephants portrayed as intrinsic to this greatness (Figs. 6–8).Footnote 28

Fig. 6 Engraving depicting a courtly procession of the Great Mughal of India, Henri Chatelain, c.1720. Private collection of Peter W. Marx.

Fig. 7 Engraving depicting an elephant fight, Pieter van der Aa, c.1720. Private collection of Peter W. Marx.

Fig. 8 Engraving depicting the pompous entrance of the governor of Surat, Pieter van der Aa, c.1720. Private collection of Peter W. Marx.

Moreover, the numerous descriptions of staged elephant fights – a favourite of the Indian emperor, despite the real risk of injury or death to spectators – made Indian court life a spectacle for the readers of these travelogues, who could relate these accounts to similar practices of bear- and bull-baiting as well as spectacular hunts.Footnote 29 Andreas Höfele has argued, with an eye on Elizabethan England, that there is a complex, intertwined relation of stage, stake and scaffold – or theatrical performance, bear-baiting and public execution. Höfele makes clear that experiences of cruelty, violence and suffering – and not just noble pursuits like philosophy and the arts – have long shaped the concept of what it means to be human.Footnote 30

The descriptions of the Indian court and the appearance of the elephant there complicate this matter because, once again, in contrast with bear, bull or cock, elephants share a closer relationship with human beings. It is this complication – the inexplicable interrelation of the Indian court and its elephants, which oscillate between being prized objects of admiration, heralds of the Indian emperor’s magnificence and potential weapons – that fascinated and puzzled Western spectators and readers.

Here, we can see an elementary difference between premodern/early modern discourse and modern discourse: in the former, the use of the elephant as a sign of force is attributed to the cultural other and draws both fear and fascination. The rare appearances of elephants in the West are always marked as exceptional, as challenging to their audiences on various levels.

The modern, occidental mindset, on the other hand, was determined to prove and stage its superiority over the entire world.Footnote 31 In 1903, Topsy, an Asian elephant that had worked in the circus and at Luna Park on Coney Island for the better part of her life, was electrocuted – with the help of the Thomas Edison Company. The fact that Edison Studios turned this event into a film (the 1903 documentary Electrocuting an Elephant), which it then circulated, can be read as a manifestation of the modernist drive to subjugate nature to industrialized, technological force.Footnote 32

De-animating the elephant: automata and puppets

The word ‘animation’ bears the echo of its Latin origin, anima (the soul). Thus animation means to give a soul to an object that lacks one.Footnote 33 But it is in the opposite process, Entseelung (de-animation), that we find another trace of early modern elephants and an influential tradition of staging elephants in this period.

In a series of illuminated manuscripts, the so-called Schembart-Books from Nuremberg, we find several sketches of massive elephant floats (Fig. 9).Footnote 34 These floats were part of spectacular carnival pageants, the Schembart-Lauf. These artificial elephants, which were set atop wooden sleds, resemble the Western imaginary of Indian war elephants, carrying small fortresses on their backs, often equipped with cannons or warriors, and throwing little fireballs. But as spectacular as these creations were, they eventually perished in fire and fireworks.

Fig. 9 Illustration of a carnival float with an elephant on a wooden sled, Schembart-Buch, Nuremberg, c.1590. With permission of the Theaterwissenschaftliche Sammlung, University of Cologne, Germany.

Notably, the creation of such large, artificial elephants was a practice found both in the East and in the West. They appeared in 1650 as part of a mock battle – with some combatants in ‘African attire’ – at the entry of Christina of Sweden (1626–89) to Stockholm, but were also a key element in the legendary 1582 celebrations arranged by Sultan Murad III (1546–95) in Constantinople for the circumcision of his son.Footnote 35 Obviously, the extravagant gestalt of the elephant marked it as a special object for spectacular destruction.

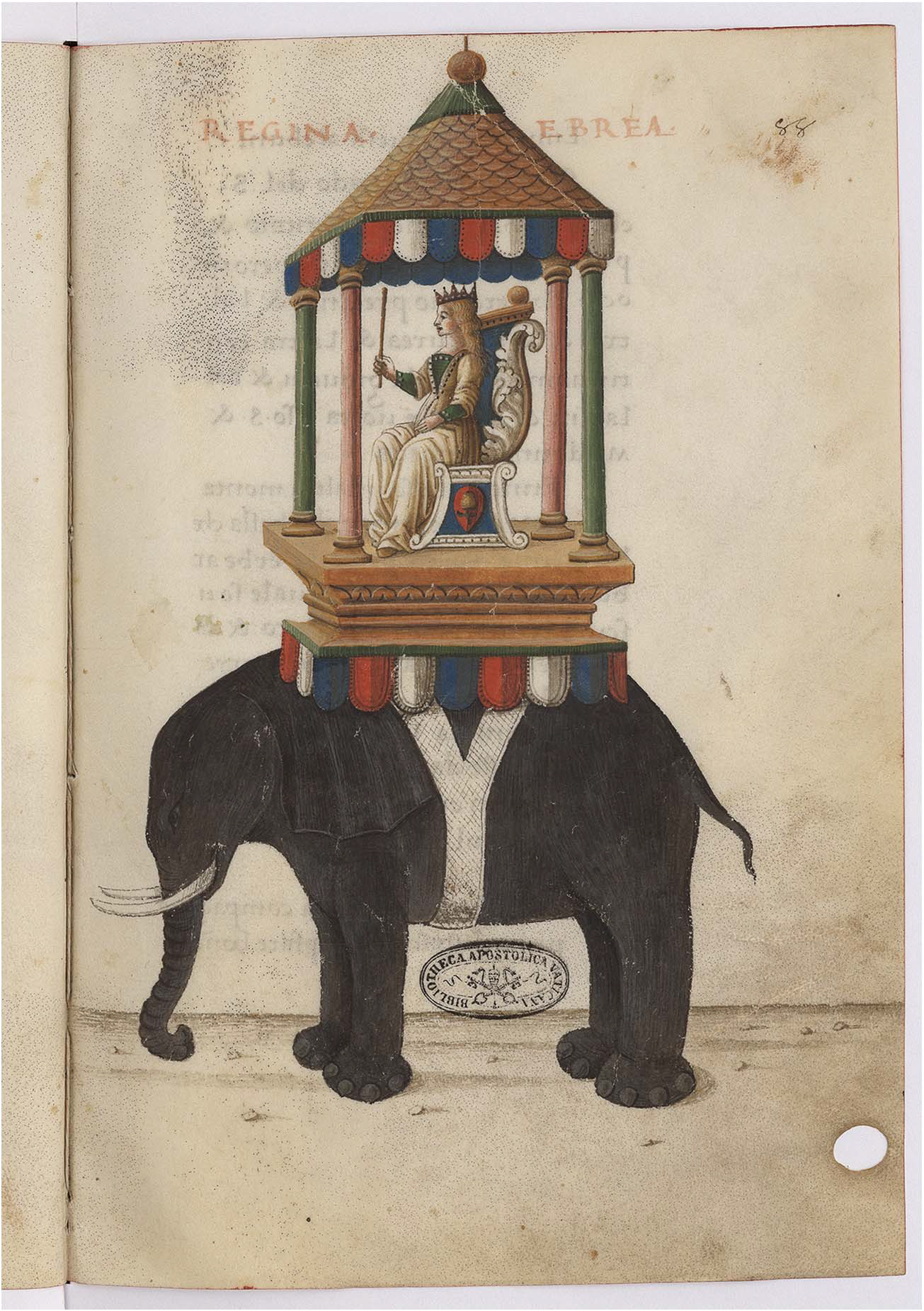

Erith Jaffe-Berg gives a different example of the usage of artificial elephants: the 1475 carnival in Pesaro (Fig. 10). As an illustrated page in the Vatican Library shows, Jewish performers had built an impressive elephant, carrying on its back a female figure described as ‘Regina Ebrea’ (Hebrew Queen) but representing the Queen of Sheba, the consort of King Solomon. As Jaffe-Berg points out, the Jewish contribution to the general festivities negotiated the tension of alterity and distance. Putting the Queen of Sheba on the elephant, the Jewish performers enhanced not just the spectacular effect of her entrance, but also the sense of alterity that infuses the biblical reference (1 Kings 10:1–2). Through the performance, a remarkable travesty occurred: while the Christian majority implicitly claimed for themselves the position of Solomon and his court, the Jewish performers were cast in the role of the Queen of Sheba (or ‘Regina Ebrea’), and marked as foreign to the festivities. Jaffe-Berg writes,

Rather than constituting an embrace of Jewish culture, these late fifteenth-century representations of Jews articulated a cultural ambivalence on the part of the Christian rulers. Included but designated as ‘other’, the Jews performed themselves as biblical objects for view rather than contemporary subjects.Footnote 36

Fig. 10 Illustration from a manuscript depicting festivities in Pesaro, 1475. The artificial elephant holds the throne of the Queen of Sheba on its back. The title reads ‘Regina Ebrea’. Manuscript Urb.lat. 899, f. 88r.; With permission of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

This effect is not without a sour irony. The biblical text names camels, not elephants, as the queen’s riding animals; in creating an elephant to enhance the spectacular effect of the scene, the Jewish performers probably also increased the sense of cultural distance.

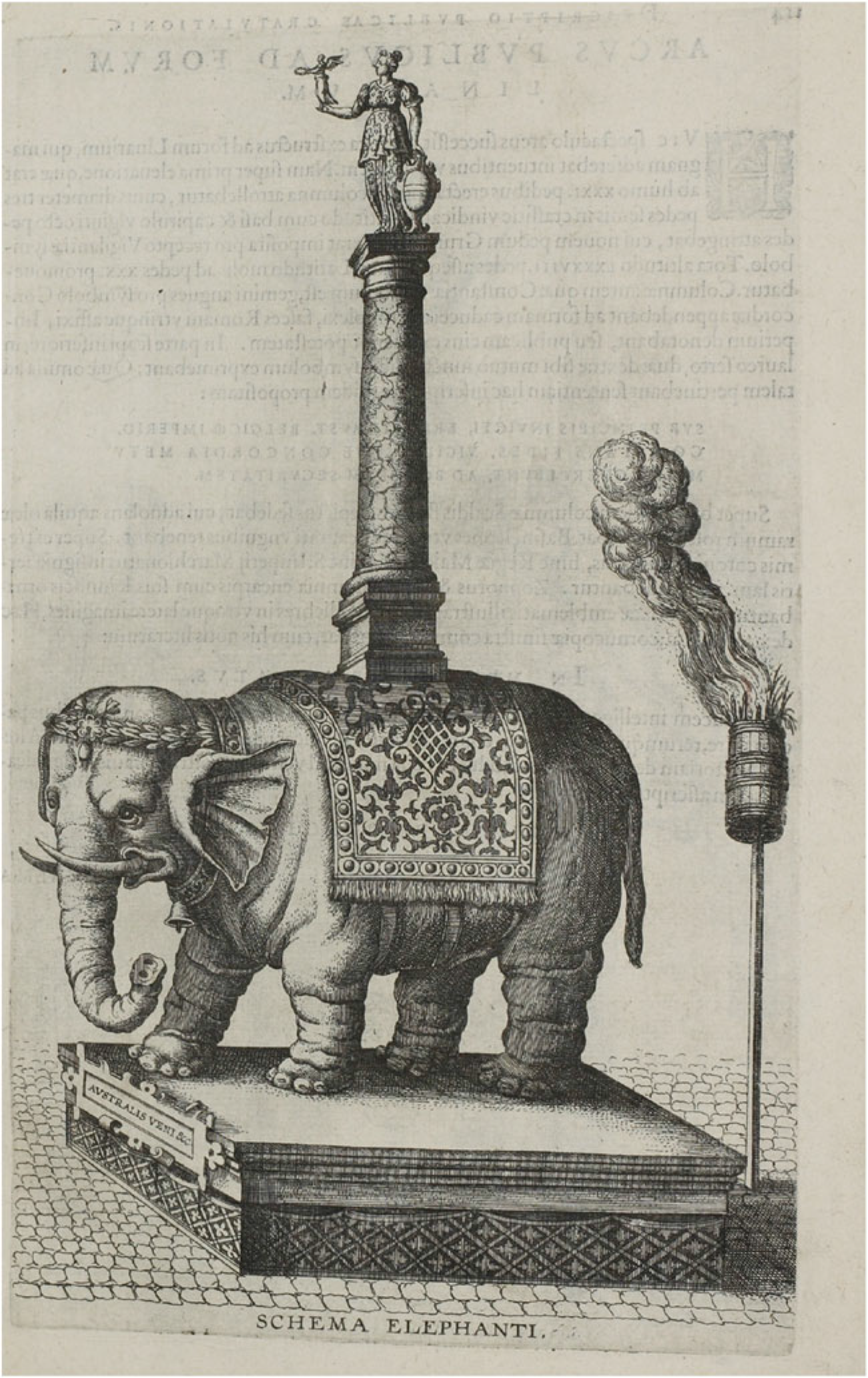

Elephants were also common in the entries of princes amid the Eighty Years’ War in Flanders and the Netherlands. These entries were elaborate pageants that acted out the political tensions between the House of Habsburg and the various communities and regions that called for political and religious freedom. A particularly prominent example is the 1594 entrance of Archduke Ernst of Austria in Antwerp, richly documented in a Festbuch that is full of illustrations and interpretive descriptions (Fig. 11). Here, we see a new level of the de-animation of the elephant: while the de-animated elephants discussed so far reduced the animal to its outward appearance, here the elephant is reduced to the level of allegory.

Fig. 11 Engraving showing the mechanical elephant presented in Antwerp for the entrance of Ernst of Austria, 1594. Here, the elephant is a mere cipher to carry the goddess of victory, Nike, symbolizing the triumph of the House of Habsburg. With permission of the Theaterwissenschaftliche Sammlung, University of Cologne, Germany.

The image shows a large elephant on a wagon that could be drawn through the city. The Festbuch gives an allegorical reading of the elephant, making it part of the Habsburgian claim to power: the message is not the animal itself, but the festive column on its back, which presents Nike, the Greek goddess of victory. As Ivo Raband has shown, this ommegangen wagon had been used thirty years earlier, at the 1585 entrance of Alessandro Farnese.Footnote 37 The mechanical beast, which could move its trunk, also conjured the memory of the elephant seen by Weinsberg in Cologne in 1563, but only to emphasize that it had become an all too ready cipher for the Habsburgian claims to power.Footnote 38

In line with this interpretation, we might also understand the appearance of a small elephant on gold coins minted in London in 1663, the year the English took over the Portuguese forts on the African Gold Coast (Fig. 12).Footnote 39 While the coins manifest their claim to African territory through their name – guinea – the miniaturized elephant hidden under the portrait of Charles II is just another performance of power. Here, the hallowed gestalt of the elephant represents the subjugation of Africa, which would soon be ruthlessly exploited for gold and slave labour.

Fig. 12 Golden guinea, 1663, depicting the head of Charles II, towering over a miniaturized elephant. With permission of the British Museum, London, UK.

For the modern world view, conquering the elephant and turning it into a mechanical device became significant proof of superiority. This, of course, also influenced its theatrical representation. The tenor, composer and theatrical manager Michael Kelly (1762–1826) recalls the following incident in his memoirs:

The second act of Blue Beard opened with a view of the Spahi’s horses, at a distance; these horses were admirably made of pasteboard, and answered every purpose for which they were wanted. One morning, Mr. Sheridan, John Kemble, and myself, went to the property room of Drury Lane Theatre, and there found Johnston, the able and ingenious machinist, at work upon the horses, and on the point of beginning the elephant, which was to carry Blue Beard. Mr. Sheridan said to Johnston, – ‘Don’t you think, Johnston, you had better go to Pidock’s, at Exeter’ Change, and hire an elephant for a number of nights?’ – ‘Not I, Sir,’ answered the enthusiastic machinist; ‘if I cannot make a better elephant than that at Exeter’ Change, I deserve to be hanged.’Footnote 40

The ‘able and ingenious machinist’ Johnston has reached the highest peak in subjugating the elephant, betting his life on his capacity to build a better elephant than Nature has created.

Performing remains: a double epilogue

What remains of the performing elephant? For the eighteenth century, the remains of elephants became a serious and puzzling issue. When, by chance, elephant remains appeared north of the Alps, they raised questions about their origin and meaning. A particularly interesting example is the discovery of elephant bones by fishermen close to Gartrop, a small village in the lower Rhine region. They collected the enigmatic bones and handed them over to their landlord, who offered them for scientific and scholarly inspection.

Johann Gottlob Leidenfrost (1715–94), a man of science, examined the bones and gave, in three short articles, his interpretation. While these were without doubt the remains of an elephant, he rebutted the popular opinion that they had been washed ashore during the Noachian deluge (that is, Noah’s flood). Their state and traces of decay made clear that they were younger. For Leidenfrost, these bones were without doubt the remains of Abu Abas, the legendary elephant of Charlemagne (747–814). Abu Abas had been a gift from the legendary caliph of Baghdad, Hārūn ar-Rāshīd (763–809), brought over the Alps by a Jewish tradesman called Isaac in 802. Charlemagne decided to take the animal along for his campaigns against the Frisians in 810. After traversing the river Lippe, Abu Abas fell ill and died.Footnote 41 According to Leidenfrost, the bones were proof of this written record: they not only proved the accuracy of the legends of Charlemagne and his elephant, but also placed the region where they were found in the historical landscape and gave it a symbolic depth.Footnote 42

While we cannot verify Leidenfrost’s interpretation – the relics of Abu Abas have been lost to time – it is still remarkable in its specific amalgamation of the biblical tradition (he is sure that these bones are not the product of the Noachian deluge, but he does not doubt the deluge itself), historical legends and transmission (Charlemagne and the elephant), and scientific examination (his careful examination of the material objects). The bones become a performing object that creates multiple connections: across epistemologies, historical epochs and, not least, cultures, reminding readers that the cultural spheres of Occident and Orient were much more intertwined than the dominant reading of Charlemagne might suggest.Footnote 43

A very different account of elephant remains is offered by an anonymous pamphlet, published in London in 1675, titled The Elephant’s Speech to the Citizens and Countrymen of England. In this semi-dramatic fiction, an elephant reports to Londoners at the Bartholomew Fair about himself, giving a full description of his physical appearance and abilities. At the end of his monologue, he turns to the audience with a personal note:

One thing more I beg of you, that you would desire my Master to send word by the next East-India ship, that my Sire, and my Dam may understand my condition, and not shorten their days for my absence. Or if I die before that, that for the good service I have and may do um, they would re-convey my Bones into my native Country, seeing the Expense of that will be nothing so much as their bringing hither.Footnote 44

While there are other examples of speaking elephants,Footnote 45 this text is remarkable in the way it ventriloquizes the elephant for the sake of naming the cruelties it has suffered and the protagonists responsible (the East India Company). The elephant even describes the mechanisms of colonial subjugation:

I was taken young from my Parents, being sold to satisfie the Covetousness of my Keepers of which there are many such in the Courts of Great Princes, pretending me to be a Bastard, and none of the right Race; though I have been told that my Sire and Dam were as honest Elephants as any in our Country.Footnote 46

The elephant names all the symptoms of rising capitalism, colonialism, racism and slavery: covetousness, a sense of superiority, the degradation of others. The elephant’s soliloquy turns into a manifesto for universal rights – long before the French Revolution. This act of prosopopoeia transforms the elephant from an object, or even a prop, into a puppet that ‘claims its own personhood’.Footnote 47 But of course we know that this act of resistance was in vain, because no tradesman or showman would have taken the effort to return the remains of a deceased elephant to its home country. On the contrary, these beasts had become a commodity mit Haut und Haaren, as the German idiom has it: with skin and hairs. And yet the elephant’s soliloquy at least creates a crack in the closed Weltbild of rising Western supremacy.

But what are the historiographic implications of these scattered traces? Well, none of the documents, anecdotes or images of elephants provide the interpreter with a holistic or even universal perspective. On the contrary, they appear as discarded, shattered fragments that will not grow into a larger narrative. For sure, there is no ‘metalanguage’ that could assemble these elements into a grand récit.Footnote 48 They are, rather, threads of a larger fabric that we cannot grasp as an entirety but are only able to describe in smaller pieces.

Reading these fragments as metonymies allows us to describe a multiplicity of contexts and constellations, whether in a political, anthropological–theological or even technological or economic sense. Elephants are of particular interest because they point towards the horizon of occidental thinking and its limitations. Through their ambivalent position as the known unknown, elephants mark a point of commensurability; that is, according to Sanjay Subrahmanyam, the precondition for any connected history.Footnote 49 Reading these singular broadsides, images, anecdotes and reports as more than merely a ‘quirky history’ widens the gaze to a larger fabric of cultural negotiations and transcultural interactions, regardless of the absence of a single, homogeneous narrative.Footnote 50

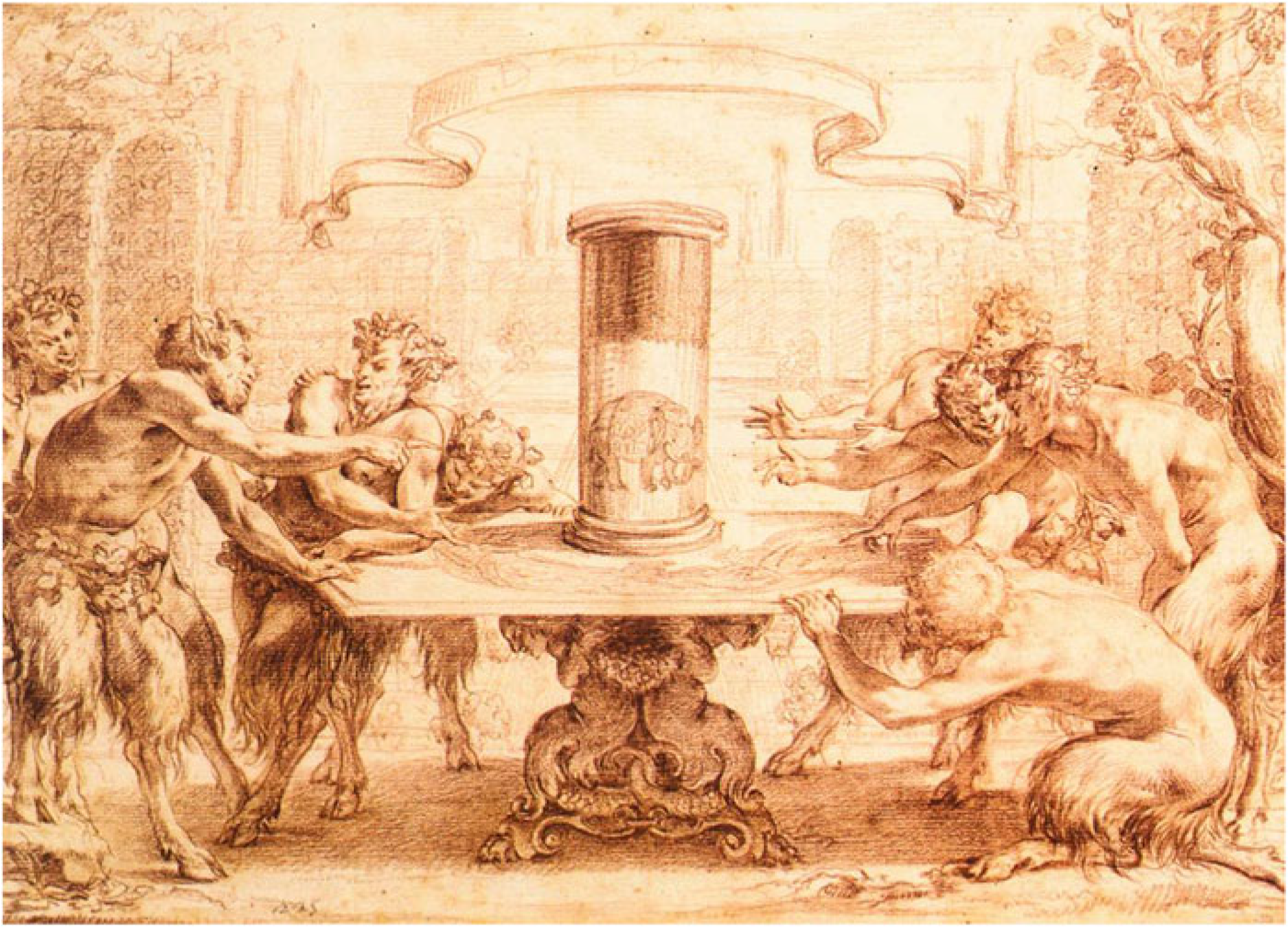

The French painter Simon Vouet (1590–1649) sketched a small scene that helps us understand this constellation (Fig. 13). On a table we see a distorted sketch, while in the middle of the table is a cylindrical mirror on which appears the figure of an elephant. Around the table stand several satyrs, clearly recognizable through their horns and goat legs. They seem to be puzzled by the form of representation and the appearance of the elephant. While satyrs represent the Dionysian aspect of Greek culture, here these ciphers of performativity are confronted with a new visual technology: the anamorphosis.

Fig. 13 Sketch of satyrs standing around a table presenting an anamorphic image of an elephant. Simon Vouet, c.1625. With permission of the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt, Germany.

Even an elephant – the largest land mammal on earth – becomes visible only through the device of the cylindrical mirror.Footnote 51 While Rumi’s version of the parable of the description of the elephant still allows for the possibility of seeing the elephant (the creature is just in a dark room; the describers are not blind), Vouet’s image could be seen as a cipher for the project of critical media history: the fragmented and distorted image appearing on the cylindrical mirror is metonymic in its form. The image shows not the candlelit ‘essence’ of the elephant itself but its cultural reflection, because it is this reflection to which the satyric spectators respond.

Critical media history as a form of writing cultural history focuses on this ever-fragile and -volatile constellation of forms, technologies and practices of presenting and seeing. Without it, we might be tempted to overlook the elephant in the room – and that would be a pity.