Duda's new charter pledges no support for gay marriage or adoption by gay couples, with Duda describing the latter as part of ‘a foreign ideology’. It also seeks to ‘ban the propagation of LGBT ideology’ in schools and public institutions – language reminiscent of a notorious Russian law targeting so‐called ‘gay propaganda’

– Walker (Reference Walker2020)

Introduction

What are the electoral consequences of linking a socially conservative political party's domestic anti‐LGBTIQ messaging to that of hostile outside actors? We take up the case of the 2023 Polish parliamentary election that ousted the Law & Justice Party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość or PiS) after 8 years in power. In PiS's campaigns, its leadership (also closely linked to Polish President Andrzej Duda) has propounded homo‐ and transphobia as part of a mission to protect ‘traditional’ Polish values from the threat of so‐called ‘LGBT ideology’ (Ayoub, Reference Ayoub2014; Stenberg & O'Dwyer, Reference Stenberg and O'Dwyer2023). For many years, this strategy brought the PiS electoral success in socially conservative Poland (Bogatyrev & Bogusz, Reference Bogatyrev and Bogusz2025; Haas et al., Reference Haas, Bogatyrev, Abou‐Chadi, Klüver and Stoetzer2025). However, as it often has in Polish politics,Footnote 1 in this election, international politics intersected with domestic homo‐ and transphobia (O'Dwyer, Reference O'Dwyer2018). Russia's full‐scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 complicated that tried‐and‐tested threat narrative because Russian President Vladimir Putin—the most visible proponent of the traditional values frame around homo‐ and transphobia—used a similar frame to justify the war, while simultaneously threatening the security of Ukraine's ally and neighbour, Poland (Edenborg, Reference Edenborg2017, Reference Edenborg, Mulholland, Montagna and Sanders‐McDonagh2018; Grabowska‐Moroz & Wojcik, Reference Grabowska‐Moroz and Wójcik2021).

Hence, there is a paradox: PiS and Putin align on anti‐LGBTIQ values, weaponized to win elections, but they clash in the geopolitics of war. How did this paradox impact electoral strategy in Poland given the salient context of the war in Ukraine? How did the PiS strategy of political homo‐ and transphobia influence their electoral fortunes? PiS's conundrum showed an emergent division between core values ahead of the 2023 elections. We argue that the past potency of this PiS strategy (Haas et al., Reference Haas, Bogatyrev, Abou‐Chadi, Klüver and Stoetzer2025) has been tainted by the war and Putin's norm entrepreneurship on the issue. While there were other polarizing issues in this election—like related concerns around PiS's highly restrictive positions on abortion (Gwiazda, Reference Gwiazda2021)—that surely also impacted voting behaviour, we find negative electoral consequences when a domestic political party's anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric is linked to a hostile outside actor.Footnote 2

In a survey experiment conducted with a nationally representative sample of Poles in July 2023, we tested whether referring to Duda's commonly deployed anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric still boosts electoral support for PiS—a party he is closely associated with—and whether it undermines support for his opposition led by Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska or PO) and Donald Tusk.Footnote 3 We then juxtapose Duda's rhetoric to Putin's related homo/transphobic justifications for the Russo‐Ukrainian War, to test a ‘guilt by association’ mechanism that links anti‐LGBTIQ political positions with unfavourable external actors and policies—events that make this rhetoric salient and untrustworthy. We find that references to Duda's politicized homo‐ and transphobia alone have a null effect on support for his party as well as that of his opposition in 2023. Hence, homo‐ and transphobic rhetoric may now have a more limited effect in Poland than in the past. On the other hand, linking Duda's rhetoric with Putin's related justification for his invasion boosted support for Tusk and his party, as we might expect if Putin's war has tainted the message's appeal. Paradoxically, the association of Putin's ‘traditional values’ promotion combined with the invasion of Ukraine may have elevated pro‐LGBTIQ political forces there, marking a consequential turning point in PiS's political fortunes. Indeed, many saw PiS as unbeatable not long ago, and the effects we isolate amplify the relevance of LGBTIQ issues in electoral politics. This study's contribution illustrates how there are saturation points for ‘going negative’ on LGBTIQ‐issue positions as a successful campaign strategy and that cross‐national issue linkages can counteract homo/transphobic campaign narratives.

War and anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric: The electoral connection

A growing body of scholarly research debates the influence of wars on election outcomes (Arena, Reference Arena2008; Chaisty & Whitefield, Reference Chaisty and Whitefield2018; Getmansky & Weiss, Reference Getmansky and Weiss2023; Herron et al, Reference Herron, Thunberg and Boyko2015). War and the threat of war may lead citizens to rally around their leaders or to punish them for the costs of conflict (Baker & Oneal, Reference Baker and Oneal2001; Berinsky, Reference Berinsky2007; Boettcher & Cobb, Reference Boettcher and Cobb2009; Getmansky & Weiss, Reference Getmansky and Weiss2023). War also may represent a critical juncture in a country's politics, driving societal divisions that shift electoral coalitions and salient ideologies (Chaisty & Whitefield, Reference Chaisty and Whitefield2018).

While existing research on war and elections has focused on conflict's impact on vote share, less attention has been paid to the ideological divisions that may be triggered by war (Chaisty & Whitefield, Reference Chaisty and Whitefield2018). In particular, the research identifies a relationship between homo‐ and transphobia and conflict (Bosia, Reference Bosia, Weiss and Bosia2013; Corriveau, Reference Corriveau2013; Hagenet al., Reference Hagen, Ritzholtz and Delatolla2024; Page & Whitt, Reference Page and Whitt2020), but its intersection with wartime election outcomes is unclear. We build on work that emphasizes the role of political homo‐ and transphobia as a tool of statecraft during wartime, including the political authorities that weaponize LGBTIQ people to legitimize their nation‐building projects along gendered and sexualized lines—often for electoral gain (Ayoub & Stoeckl, Reference Ayoub and Stoeckl2024; Bosia, Reference Bosia, Weiss and Bosia2013; Bosia & Weiss, Reference Bosia, Weiss, Weiss and Bosia2013; Page & Whitt, Reference Page and Whitt2020). The electoral connection between war and anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric illustrates how politicians attempt to mobilize voters against perceived threats to the state and society with calls to action and allusions to violence towards enemies both internally and abroad. These dynamics are common to the electoral politics of present‐day Poland. What is often missed, however, are the linkages between perceived threats posed by outside actors (such as Putin and his war in neighbouring Ukraine) and conservative rhetorical ‘threats’ posed by LGBTIQ identities to societal norms.

Homo/transphobia: From the Cold War to culture wars and the invasion of Ukraine

Throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries, states at war have weaponized homo‐ and transphobia against each other across the ideological divides of communism, fascism and liberal democracy (on Nazi, Soviet and other state propaganda; see Corriveau, Reference Corriveau2013; Ritholtz, Reference Ritholtz2022; Stites, Reference Stites1978). All the while, modernization and global inequality have led to greater gaps in social values between Western and non‐Western countries, especially regarding LGBTIQ tolerance. Moreover, research on international norms shows that LGBTIQ tolerance has simultaneously (and problematically) been constructed as a marker of Western values and has become a target of non‐Western political elites (Ayoub & Paternotte, Reference Ayoub, Paternotte, Mendez and Naples2014; Velasco, Reference Velasco2023). Homo‐ and transphobia often serve as a cudgel of nationalistic governments to portray their cultures as threatened by ‘foreign’ values and forces (Ayoub, Reference Ayoub2014; Bob, Reference Bob2019; Velasco, Reference Velasco2023). This is true of the Russian government in the last 15 years, for example, where homo‐ and transphobia are deployed to demonize ‘the West’ and fortify Putin's traditional values paradigm (Edenborg, Reference Edenborg, Mulholland, Montagna and Sanders‐McDonagh2018; Shevtsova, Reference Shevtsova2022; Stoeckl, Reference Stoeckl2016; Stoeckl & Uzlaner, Reference Stoeckl and Uzlaner2022; Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson2014).

More specifically, Putin presents Russia as a civilization model with heteronormativity/family values as central features distinguishable from a decadent West (Buyantueva, Reference Buyantueva2018). This model emerged through a revived relationship between the Kremlin and the Russian Orthodox Church and has had tangible effects ever since (Stoeckl, Reference Stoeckl2016; Stoeckl & Uzlaner, Reference Stoeckl and Uzlaner2022). The Kremlin's full‐fledged anti‐LGBTIQ campaign is waged domestically (via a series of so‐called anti‐LGBTIQ propaganda and foreign agent/extremist laws) and internationally (via United Nations resolutions and transnational anti‐gender advocacy), including in the justifications for the invasions of Ukraine and antagonism of European Union and NATO members (Feder, Reference Feder2024; Tyushka, Reference Tyushka2022; Van Herpen, Reference Van Herpen2015). For example, Putin has made a variety of problematic associations defending his policies, like ‘We have a ban on the propaganda of homosexuality and paedophilia’ (Walker, Reference Walker2014). Further, Russian Orthodox patriarch Kirill's sermon justifying the full‐scale invasion of Ukraine asserted that ‘Pride parades [in the West] are designed to demonstrate that sin is one variation of human behavior. That's why in order to join the club of those countries, you have to have a gay Pride parade’ (Kirill, cited in Cooper, Reference Cooper2022). All the while, Putin's campaign dovetails with the rhetoric of right‐wing nationalist forces outside of Russia who have used similar anti‐LGBTIQ arguments domestically; for example, the Trump Campaign's intensive deployment of constructed threats around transphobia in the 2024 election (Romano, Reference Romano2024).

We theorize that Putin's aggression in Ukraine may undermine some of his goals. Most directly, in Ukraine itself, the Kremlin's deployment of LGBTIQ‐phobic rhetoric has engendered a significant improvement in societal attitudes towards LGBTIQ people as well as specific LGBTIQ‐inclusive legislative action by the Ukrainian government (Shevtsova, Reference Shevtsova2022; Shmatko & Rachok, Reference Shmatko, Rachok and Shvetsova2024). Previously, during the 2014 Ukrainian parliamentary election, D'Anieri (Reference D'Anieri2022) found that Putin's invasion of Crimea negatively influenced support for pro‐Russian political forces, while Chaisty and Whitefield (Reference Chaisty and Whitefield2018) suggest that the same election left Ukraine's political cleavages largely intact, but that the Kremlin was unlikely to expand its geopolitical influence at the ballot box in Ukraine.

Beyond Ukraine, questions remain about the anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric commonly used by illiberal forces in elections and whether the social divisions between the West and Russia, intensified by Putin's war, altered the rhetoric's appeal among those opposed to the war. For the Kremlin, LGBTIQ people and their rights are presented as problems of Western culture that require a Russian response. We argue that Putin's justifications for the war should undermine anti‐LGBTIQ incumbents elsewhere, at least ones whose own anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric aligns with that of the Kremlin, but where public sentiment runs strongly against Russia's invasion of Ukraine. We consider one example in the case of Poland, where both homo/transphobia and the war in Ukraine were salient political issues in recent parliamentary elections.

The Polish elections: Anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric in the shadow of the Ukraine War

Poland held its parliamentary elections in October 2023—1.5 years after Russia's full‐scale invasion of neighbouring Ukraine. While the Russo‐Ukrainian war and the issues it impacted—like refugee migration and the economy—figured prominently in the election, the PiS‐ and PO‐led coalitions (again) rhetorically clashed over LGBTIQ rights (Dunin‐Wąsowicz, Reference Dunin‐Wąsowicz2023; Walker, Reference Walker2023).Footnote 4 Past PiS campaigns against ‘LGBT ideology,’ like in 2020, are symbolic of this, with President Duda saying ‘[my parents] didn't fight [to eliminate Communism] so that a new [LGBT] ideology would appear that is even more destructive for people’ (campaign rally in Brzeg, Poland on 13 June 2020; Hume, Reference Hume2020). Like Jarosław Kaczyński, PiS's leader, Duda paints same‐sex unions as ‘foreign’, and his campaign proposed bans of so‐called ‘LGBT ideological’ propaganda—legislation borrowed directly from Russia (Walker, Reference Walker2020). Duda has claimed multiple times that ‘LGBT is not people, it's an ideology.’ PiS vice‐president Joachim Brudziński amplified the party's anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric during the election month in 2020 by declaring on Twitter, ‘Poland is most beautiful without LGBT’ (Brudziński, Reference Brudziński2020).

Meanwhile, the PO and Tusk pledged to introduce legislation for same‐sex civil partnerships and simplify gender recognition for trans people ahead of the 2023 election (Krzysztoszek, Reference Krzysztoszek2024). As a justification, he said, ‘The most important thing is to rebuild the language of respect… Love deserves our respect’ (Tusk, Reference Tusk2023). This rhetoric is markedly different from the political homo‐ and transphobia that PiS and Duda openly espouse, which is emblematic of Putin and the Kremlin—even if voters did not always know of this association. This rhetorical similarity might resonate with voters differently in 2023, given the salient divergence between Russian and Polish positions towards the war. As noted above, since the full‐scale invasion began, the Ukrainian government has become inspired to pass more LGBTIQ‐friendly policies (Chisholm, Reference Chisholm2023). We expect a similar ‘guilt by association’ shift in Poland for voters made aware of the rhetorical linkage between the Polish political right and Russia—something that PiS would never acknowledge, but that PO could have potentially capitalized on more effectively during the election. We ask whether Putin's political homo‐ and transphobic rhetoric can affect the electoral support of political parties in a country threatened by his war.

While pundits struggled to make predictions leading into the 2023 election, it would produce a larger‐than‐expected shift in favour of a pro‐EU, centrist Civic Coalition (KO) led by the PO and ousting PiS (Ptak, Reference Ptak2023; NDI, 2023). While PiS remained the most popular party, with 35.4 per cent of voters in its coalition, the KO won 30.7 per cent of the vote (and its coalition partners Third Way and New Left won 14 per cent and 9 per cent of the vote, respectively).Footnote 5 These results were partly driven by the biggest turnout – 73 per cent of eligible voters—since Poland's democratization in 1989 (Ptak, Reference Ptak2023; Szczerbiak, Reference Szczerbiak2023). In particular, educated urbanites turned out in record numbers to oust the on‐average rural, older and less educated PiS bloc (Ptak, Reference Ptak2023). We argue that the factors we study here hold symbolic weight and contributed in part to PiS's opposition and ousting.

Theory and preregistered predictions

In our preregistered design, we theorize how a domestic leader's anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric could impact their domestic support. Previous research has shown that appealing to anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric could improve a leader's support by boosting their moral authority among social conservatives (Bosia & Weiss, Reference Bosia, Weiss, Weiss and Bosia2013), which has likely helped PiS in past elections (Haas et al., Reference Haas, Bogatyrev, Abou‐Chadi, Klüver and Stoetzer2025). Such appeals have two goals: a policy goal to undermine public support for LGBTIQ rights and a personalist goal to boost one's own domestic support base. While such rhetoric has galvanized public support, we theorize its potential to backfire depending on the international geopolitical context and whom the rhetoric can be associated with. This is illustrated in Figure 1, which maps pathways for how a leader's anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric might resonate with different segments of the society and importantly when that resonance might be lost. The path we later examine empirically is highlighted in grey. We argue that a leader's domestic support is likely to suffer if anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric somehow undermines their moral credibility. Among social liberals and moderates, anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric could potentially backfire, increasing LGBTIQ support as well as stimulating opposition to the domestic leader. While the extent to which leaders who espouse anti‐LGBTIQ agendas thrive or struggle electorally likely depends on the embeddedness of social conservatism and support or opposition to LGBTIQ rights, it may also be impacted by how those leaders’ agendas are framed in moral contexts, including political oppression and war‐related violence.

Figure 1. Conceptual pathway diagram for domestic leader messaging effects.

In light of our theory, we consider the effect of Duda's anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric on PiS support in Poland. Duda campaigned for PiS ahead of the 2023 election, and the fortunes of PiS and Duda are closely linked such that a referendum on PiS continuity is also a referendum on Duda's political agenda and vice versa.Footnote 6 To the extent to which Duda is seen as a moral authority among socially conservative Poles, priming on his anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric could boost PiS support but could also countermobilize liberal supporters of the PO. In principle, such mobilization and counter‐mobilization could balance one another, producing perhaps greater electoral turnout but not necessarily giving either party an electoral edge.

However, we also consider whether international linkages between Duda's rhetoric and that of Russian President Putin reinforce or counter the effectiveness of the anti‐LGBTIQ narrative as an electoral strategy. Our preregistered prediction is that linking Duda to Putin on the theme of anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric could elevate PiS's support among social conservatives but only if they view Putin favourably as a moral authority. However, while social conservatives in Poland potentially share Putin's anti‐LGBTIQ biases, very few would consider Putin as a moral authority. Putin is deeply unpopular among Poles. Hence, linking Duda's views to Putin could have negative consequences for PiS support, especially in light of his devastating full‐scale invasion of neighbouring Ukraine. A key theoretical mechanism here is that of ‘guilt by association’ with the intensely disliked. We anticipate a countermobilizing effect on social liberals and moderates such that Putin–Duda linkages would also shift support towards the PO.

That said, we are aware that Putin's homo‐ and transphobia alone has not always been generally visible to voters in other countries, and it might not register with them emotionally or be interpreted as problematic on its own. There are common policy positions taken by socially conservative politicians that might seem acceptable to domestic audiences and would not naturally trigger any ‘guilt by association’ mechanism. When that politically motivated rhetoric is put into action in the context of justifying violence (as in a war), however, people may begin to question its moral foundations. Such linkages expose the rhetoric's more sinister usage as a political tool, undermining its credibility, trustworthiness and supposed ‘morality’. Thus, as depicted in Figure 1, we are particularly interested in the impact of this rhetoric in relation to the Russo‐Ukrainian War. We anticipate that receptivity to Duda–Putin's linkages to anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric could be conditional to both views of Putin's moral authority and support for the War, which Putin has justified in part based on anti‐LGBTIQ motives, and thus puts that rhetoric into action. We anticipate that linking Duda's anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric to Putin and the Russo‐Ukrainian War would mobilize social liberals and moderates against the PiS in favour of PO. I could also hurt Duda's credibility as an international anti‐LGBTIQ messenger among socially conservative Poles, who, like liberals and moderates, have been strongly opposed to Russia's invasion. Even if social conservatives are otherwise supportive of Duda's anti‐LGBTIQ issue positions, many may balk at linkages between their views and Putin's justifications for the Russo‐Ukrainian war (their views in action). Thus, linking Duda to both Putin and Ukraine could have broadly negative consequences for PiS support. We test the following hypothesis:

H1. Linking Duda's anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric to Vladimir Putin and his justification for the Russo‐Ukraine War will increase PO support relative to PiS.

Research design

To test our hypothesis, we conducted an original survey experiment with 1000 respondents in Poland in July 2023. We commissioned the firm Ipsos to collect a nationally representative online sample of 1000 Poles aged 18–65 with demographic quotas for gender, age, size of residence, region and education. The survey assesses the influence of Duda's anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric, Putin's influence as an international moral authority and the Russo‐Ukrainian War with four randomized experimental groups (about 250 responses per group) that manipulate whether respondents receive (1) a message about Duda's anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric, (2) a message about Duda's anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric and its similarity to Putin's, (3) a message about Duda's homophobic rhetoric and its alignment with Putin along with Putin's anti‐LGBTIQ justification of the Russo‐Ukrainian War and (4) a control group with no additional information for the respondents (see Table 1). We provide pre‐registration and pre‐analysis plans in the online Appendix.

Table 1. Experimental groups

We then measure the likelihood of voting for candidates who share values with the two main political parties competing in the parliamentary elections, the incumbent Law & Justice Party (PiS) and the main opposition Civic Platform (PO). In the Polish parliamentary elections, voters choose their preferred candidate (giving them priority to become an MP) from their preferred party's list. First, we asked: How likely would you be to vote for a candidate with the same views as PiS and Duda? Second, we asked: How likely would you be to vote for a candidate with the same views as PO and Tusk? Response options to both items range from 1 (Not at all likely), 2 (Not very likely), 3 (Somewhat likely) and 4 (Highly likely).

Other variables, discussed in detail in the online Appendix, include pre‐treatment ideological distinctions between social liberals, moderates and conservatives, support for Russia or Ukraine, support for LGBTIQ rights and socioeconomic indicators. Post‐treatment variables consist of views of Duda as a moral authority, LGBTIQ rights support and PiS and PO support.

Results

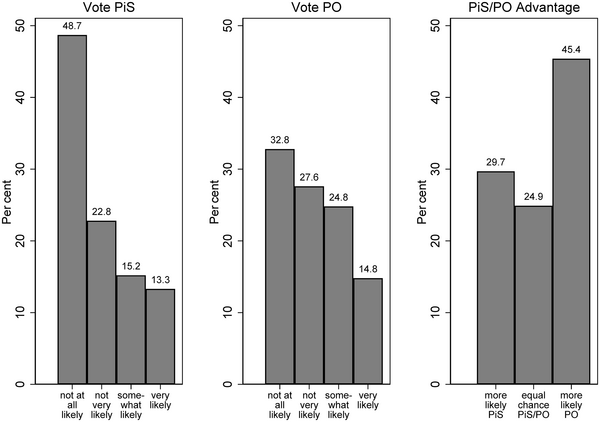

We begin with response distributions on our key outcome variable in Figure 2: support for PiS and PO. We observe greater hard opposition to PiS than PO (49 per cent vs. 33 per cent). Overall opposition to PiS is also greater than PO when combining hard and weak opposition response categories (72 per cent for PiS compared to 60 per cent for PO). In contrast, both PiS and PO received similar levels of strong support (13 per cent for PiS and 15 per cent for PO), but the PO had the advantage among less committed voters (25 per cent to 15 per cent) whose support might be reflecting movement going into the late stages of the October election. Similarly, when we take the difference in likelihood for PO versus PiS voting, 45.4 per cent of our sample indicated that they were more likely to vote for PO than PiS, while only 29.7 per cent were more likely to vote for PiS over PO. We refer to this difference as the PiS/PO Advantage.

Figure 2. Vote likelihood for PiS/PO.

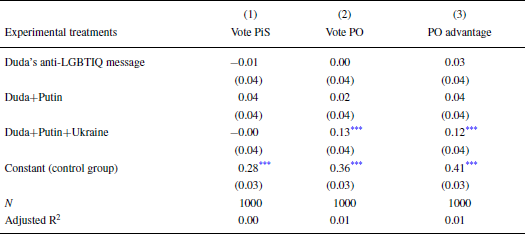

For ease of interpretation, we used binary‐dependent variables with 1 representing respondents who are likely to support a party (very and somewhat likely) and 0 representing those that were unlikely to support a party (not very and not at all likely) and then estimated average treatment effects using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression in Table 2.Footnote 7 We fail to find significant treatment effects on support for Duda/PiS in Model 1. It is likely that showing the anti‐LGBTIQ message in action, and for what it is – a political tool—does not resonate with people. However, in Model 2 we observe that linking anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric to the war in Ukraine resulted in a 13 per cent increase in support for PO/Tusk (unpaired t‐test = 3.02, p < 0.002). Model 3 shows comparable effects taking the difference in vote likelihood for PO versus PiS and coding 1 for those more likely to vote PO over PiS and 0 if otherwise—that is, the PO advantage.

Table 2. Likelihood of voting for PiS and PO (OLS regression)

Note: Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

Abbreviations: PiS, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość; PO, Platforma Obywatelska.

Table 2. p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.01

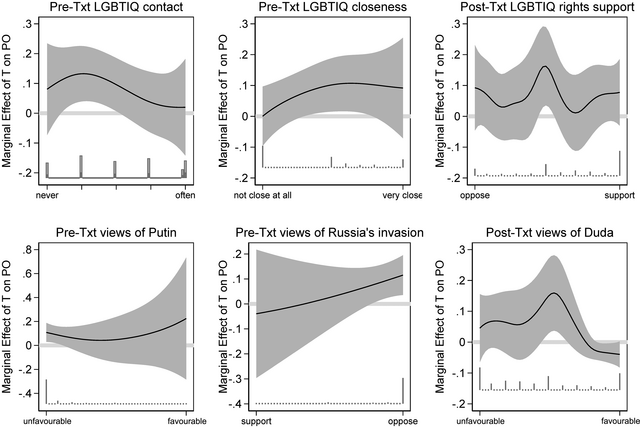

Next, we consider how increases in the PO advantage in voter support in the Duda+Putin+Ukraine treatment might be conditional to items embedded in the treatment: LGBTIQ rights support, attitudes towards Duda or Putin's moral authority and attitudes towards the Russo‐Ukrainian war as outlined in our conceptual pathways in Figure 1. We assess conditional marginal effects using OLS regression with interaction terms between the treatment at different values of the moderator variables discussed above (see the online Appendix for full models).Footnote 8 In Figure 3, we report conditional marginal effects of the Duda+Putin+Ukraine treatment on PO advantage compared to other treatments (represented by the baseline y = 0 axis). Following Hainmueller et al. (Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu2019), we utilize a kernel estimator to evaluate potential nonlinear effects at different levels of the moderator and visualize the response distribution at the bottom of each graph.

Figure 3. Conditional marginal effects of the Duda+Putin+Ukraine treatment (T) on PO advantage (PO).

First, LGBTIQ support as measured by contact with and feelings of closeness to LGBTIQ people, as well as support for LGBTIQ rights, is strongly correlated with PO support (see the online Appendix for item descriptions and coding details). However, the Duda+Putin+Ukraine treatment was more effective at shifting support to PO over PiS among moderates (those in the middle categories of LGBTIQ support) than among strong supporters (who were already voting PO) or opponents (who were unfazed by the treatments in the PiS support). Next, the treatment was also successful at directing support to PO among those with strong unfavourable views of Putin's moral authority and who wish to see Russia defeated in the war in Ukraine, underscoring the deep disapproval of the Polish electorate for Putin and his invasion of Ukraine. Finally, we consider the effect of the treatment on Duda's moral authority. While favourable views of Duda are negatively correlated with PO support. Figure 3 shows that the Duda+Putin+Ukraine treatment was successful in generating PO support among those with moderate views of Duda. In the online Appendix, we employ structural equation modelling to show how reductions in Duda's moral authority following the treatment partially mediate rises in PO support, indicating how linkages between Duda and anti‐LGBTIQ messaging (alongside Putin and the Russo‐Ukrainian War) enhance PO support through a ‘guilt by association’ mechanism. We also provide an additional array of robustness checks to include additional extended controls and covariate balance tests.Footnote 9

In summary, the analysis supports pathways discussed in Figure 1 where domestic homo/transphobic electoral narratives can be countered by discrediting the moral authority of a domestic messenger (Duda) by linking their anti‐LGBTIQ messaging to unfavourable international actors (Putin) and political violence (the war in Ukraine) (cf. Ayoub et al., Reference Ayoub, Page and Whitt2025). These also illustrate how ‘guilt by association’ between the war and Duda's anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric influences electoral outcomes. Priming homo‐ and transphobic rhetoric failed to increase support for PiS in 2023 (already a notable finding) and this same rhetoric, when framed in the context of the war in Ukraine, actually boosted support for the PO opposition instead. This may be good news for LGBTIQ rights in Poland. The way anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric has been used to justify war violence undermines anti‐LGBTIQ momentum at the polls, making the association between anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric and war salient and undercutting the authority of both message and messenger. Specifically, war‐related messaging increased PO support among those with greater pretreatment tolerance of LGBTIQ people and those sceptical of Duda's moral authority.

Conclusions

This study examines the intersection between war, homo/transphobia and elections. We contribute to existing research with an early test of political anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric's effect on voters’ party choices including commonly used domestic and internationally circulating anti‐LGBTIQ messages. In our study ahead of the 2023 Polish parliamentary election, we found that homo‐ and transphobic rhetoric alone no longer influenced opinions regarding the major parties—an important finding given that PiS confidently relied on this strategy in the past. Additionally, we found that priming on the Russo‐Ukrainian war alongside anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric boosts support for the Civic Platform party, the opposition to the incumbent nationalists (PiS). Again, this result may be important for LGBTIQ politics in Poland, given that PiS has used anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric in an attempt to move electoral dials in elections since 2005 (Ayoub, Reference Ayoub2016; O'Dwyer, Reference O'Dwyer2018). We have theorized that this shift may be related to the geopolitics of the war in Ukraine and anticipate that these findings may play out similarly in democracies threatened by the Kremlin. Indeed, when anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric is associated with Putin's invasion, it may have helped the more tolerant opposition party gain support. A ‘guilt by association’ mechanism, where LGBTIQ rights are connected to Russia's invasion, could be tested in a variety of countries that take issue with the war (like the United KingdomFootnote 10). Further, our design could be repeated with respect to a variety of polarizing issues, like Muslim migration or abortion rights in Poland (Gwiazda, Reference Gwiazda2021), that might be linked to disliked messengers or events.

These findings also yield an overarching practical contribution. We show that while homo‐ and transphobia are commonly weaponized by nationalist politicians the world over, public opinion in Poland (a challenging case for LGBTIQ rights) was less susceptible to this once‐reliable strategy when associated with the Russo‐Ukrainian War and likely reflects the changed geopolitical conditions in the international sphere. This may be useful for LGBTIQ advocates in some conservative contexts. While anti‐LGBTIQ messages tend to be emulated and proliferated by political leaders, the full‐scale invasion of Ukraine may be damaging these messages’ potency—especially when linkages become apparent. Indeed, transnational conservative networks and traditional‐values norm entrepreneur states (like Russia) have inserted anti‐LGBTIQ rhetoric into electoral campaigns around the world (Ayoub & Stoeckl, Reference Ayoub and Stoeckl2024). Yet, the centrality of the Russian state in that network, and the brutality of its war, may temper the anti‐LGBTIQ‐rhetorical blueprint in contexts with little support for the war. Activists have noted that the tragic geopolitical situation in Europe might also be creating openings for LGBTIQ tolerance, and our research suggests their intuition may be justified. We hope the findings are informative as they seek to challenge leaders who vilify LGBTIQ people during elections. Reminding the public that such hostile words parallel those of the atrocious and disliked (whose words and actions have deadly consequences) may further the cause of tolerance.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the last two editorial teams of the European Journal of Political Research and the three anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and constructive feedback. Their engagement and suggestions greatly improved the article. We also wish to thank several friends and colleagues at the Against the TIDE: Resisting Illiberal Politics and Anti‐LGBTQI Measures workshop, held by the Háttár Society at Central European University in Budapest on 25 May 2023, for the rich conversations that helped inform parts of this work. Any errors are our own. We had support from our research funds at Gettysburg College, High Point University, and UCL.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest; we did not use AI in the preparation of this manuscript.

Data availability statement

The data are publicly available at Ayoub et al. (Reference Ayoub, Page and Whitt2025), ‘Replication Data for: Anti‐LGBT Messaging and Electoral Outcomes under the Shadow of War: Evidence from the 2023 Polish Parliamentary Election’, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QQ7HBY, Harvard Dataverse.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: