Educators are increasingly involved in schoolwide reforms to improve student support and outcomes (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Hirsch, Rodgers, Bruce and Lloyd2017). Consequently, professional development offerings have expanded significantly internationally in recent decades, including in the United States, where this study occurred (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2019). The mounting number of training sessions and tasks that educators handle can leave them with little time for their core responsibilities (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Hirsch, Rodgers, Bruce and Lloyd2017). This study’s premise is that educators and administrators should consider schoolwide leadership team member time allocations to implement schoolwide reforms and interventions effectively. The researchers developed a time-use study process for multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) leadership teams. Researchers conducted two focus groups to explore elements of an MTSS time-use protocol for PK-12 educators, including codes, categories, timing, and data collection approaches. At a school level, data from such a study may help staff and administrators adjust roles and responsibilities to implement strategies more efficiently.

Context

PK-12 students face academic, behavioural, and emotional challenges. For instance, one in three high school students reported persistent hopelessness and sadness, a 40% rise from 2009 to 2019 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). COVID-19 exacerbated these issues, impacting over 55.1 million students globally, including 7.5 million students with disability (Educating All Learners Alliance, 2020). Following the pandemic, 84% of teachers surveyed believed that students were behind in self-regulation and relationship building. Further, 68% indicated that student problem behaviours had increased since 2019–2020 (EAB Global, 2023). Research also highlights the disproportionately reactive discipline responses for students of colour (Tefera et al., Reference Tefera, Siegel-Hawley, Sjogren and Naff2024) and students with disability (Sears et al., Reference Sears, Xu and Simonsen2025), such as suspensions and expulsions. These concerns have intensified calls for schoolwide reforms (Office of the Surgeon General, 2021). As a whole-school approach, MTSS may offer a way to address this call.

MTSS is a framework involving team-based decision-making, data-driven needs identification, aligned interventions, and an effective core curriculum (Goodman & Bohanon, Reference Goodman and Bohanon2018; Michigan’s MTSS Technical Assistance Center, n.d.). Data include universal screening to identify student needs and potential adaptations to the curriculum. Teams use data to monitor student progress and evaluate intervention effectiveness (CEEDAR Center, n.d.).

MTSS provides an umbrella for the implementation of critical components of school improvement. The components include a continuum of support, ranging from whole-school (i.e., Tier 1), group-level (i.e., Tier 2), and individual interventions (i.e., Tier 3). Further, community and family involvement are cornerstones of MTSS implementation. MTSS also involves staff professional development, including curriculum design and effective collaboration (CEEDAR Center, n.d.). The focus of this research is on helping schoolwide leadership teams find time for implementing professional learning. When staff have the time to implement, MTSS can have a positive impact on students.

MTSS applications have also increased internationally in the wake of school staff moving from a wait-to-fail model to early identification and prevention approaches (de Bruin et al., Reference de Bruin, Killingly, Graham and Graham2023). Previous research demonstrates the positive impact of MTSS implementation on academic, behavioural, and social-emotional outcomes across a range of student populations, including students with disability (Choi et al., Reference Choi, McCart and Sailor2020; Fuchs & Fuchs, Reference Fuchs and Fuchs2017), students in high-poverty schools (Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Mitchell and Leaf2010; Gage et al., Reference Gage, Lee, Grasley-Boy and Peshak George2018), and schoolwide populations receiving social-emotional learning supports (Durlak et al., Reference Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor and Schellinger2011; Hart et al., Reference Hart, DiPerna, Lei and Cheng2020). MTSS implementation has also shown benefits in secondary school settings with diverse student needs (Swain-Bradway et al., Reference Swain-Bradway, Lindstrom Johnson, Bradshaw and McIntosh2017; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Oberle, Durlak and Weissberg2017). Some research indicates that schools implementing MTSS with higher levels of fidelity also demonstrated enhanced school improvement and factors related to school dropout (Bohanon et al., Reference Bohanon, Wu, Kushki and LeVesseur2024; Bohanon et al., Reference Bohanon, Wu, Kushki, LeVesseur, Harms, Vera, Carlson-Sanei and Shriberg2021).

Despite increased professional development, time constraints continue to hinder meaningful staff engagement with MTSS components (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2019). Demands on educators’ time increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic and have continued since, with veteran and female teachers reporting particularly high workloads and stress (Gicheva, Reference Gicheva2022). These challenges manifest in limited time for planning interventions, analysing data, and participating in problem-solving meetings — core practices essential for effective MTSS implementation.

Further, decontextualised training exacerbates these time-related barriers by requiring educators to interpret and adapt general frameworks without support (Collins & Liang, Reference Collins and Liang2015; Hammond & Moore, Reference Hammond and Moore2018). In many cases, professional learning sessions are delivered in a one-size-fits-all format that lacks relevance to specific school contexts, resulting in additional time spent modifying materials or reworking implementation strategies. This mismatch between training content and on-the-ground needs not only reduces efficiency but also contributes to staff fatigue and diminished engagement.

Across the globe, workload imbalances limit staff’s ability to carry out MTSS effectively (Leslie & Oberg, Reference Leslie and Oberg2025). Many educators feel pressure to help students catch up academically, behaviourally, and socially post-COVID-19 (EAB Global, 2023). Without aligning implementation efforts to actual time availability, MTSS leadership team members may lack sufficient bandwidth for essential activities such as training, coaching, and collaborative planning (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Camburn, Kelcey and Quintero2021; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2005, Reference Kennedy2016). These teams often operate without dedicated time for data review and decision-making (Avant & Swerdlik, Reference Avant and Swerdlik2016). Attempting to redesign workflows without first understanding existing time demands is unlikely to result in sustainable solutions (Covey, Reference Covey2020; Killion, Reference Killion2023).

Time-Use Studies

Time-use studies involve individuals tracking their time allocations using analog (Vannest & Hagan-Burke, Reference Vannest and Hagan-Burke2010) or digital recording tools (Dmytryshyn & Goran, Reference Dmytryshyn and Goran2022). Implementers collect data in vivo or retrospectively at the end of the day. The duration of these studies varies depending on the study’s purpose, from one day to several weeks. Some studies focus on a broader understanding of how educators use their time in general (OECD, 2014). Other studies, and the purpose of this current research, focus on helping staff improve their efficacy through tracking and reflecting on their professional responsibilities across time (Dmytryshyn & Goran, Reference Dmytryshyn and Goran2022; Kelly & Whitmore, Reference Kelly and Whitmore2019). Teams also use these data to evaluate the cost-benefit of their time and effort allocations (Pas et al., Reference Pas, Lindstrom Johnson, Alfonso and Bradshaw2020) and supporting staff advocacy for workflow changes (Cooc, Reference Cooc2019; Kelly & Whitmore, Reference Kelly and Whitmore2019; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Creagh, Stacey, Hogan and Mockler2024).

For example, educators have used time-use data to adjust schedules and reduce competing demands, ensuring adequate time and preparation for implementing interventions (Grima-Farrell, Reference Grima-Farrell2018). In another instance, social workers from multiple schools used time tracking to identify non-essential tasks, such as proctoring exams. After sharing these findings with administrators, those duties were reassigned, allowing staff to redirect time to more relevant schoolwide tasks, such as developing behaviour lesson plans (Kelly & Whitmore, Reference Kelly and Whitmore2019).

Previous education-related time-use studies have examined partial or full school days (Cooc, Reference Cooc2019; Vannest & Hagan-Burke, Reference Vannest and Hagan-Burke2010). However, many of these studies are profession-specific (e.g., focused on social workers or administrators), prioritise in-person activities, and often exclude tasks performed outside traditional school hours (Cooc, Reference Cooc2019; Grissom et al., Reference Grissom, Loeb and Master2013). These limitations may overlook the broader workload educators face related to MTSS, including planning, communication, and documentation completed before or after the school day. While promising, time-use studies have yet to be developed for professionally diverse MTSS teams.

In addition to research gaps, there are practical challenges in implementing time-use studies with MTSS leadership teams. Staff may be hesitant to participate due to concerns about surveillance, increased workload, or uncertainty about how time data will be used — particularly in contexts where time constraints already hinder MTSS engagement (Gicheva, Reference Gicheva2022; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2019). Technical barriers, such as limited device access, unfamiliarity with digital tools, or inconsistent data entry, may further complicate implementation. These concerns echo broader critiques of professional development that lack contextual relevance or practical utility (Collins & Liang, Reference Collins and Liang2015; Hammond & Moore, Reference Hammond and Moore2018). To address these challenges, schools may consider strategies such as offering training to clarify purpose and process, providing modest incentives, using user-friendly digital platforms, and securing leadership support to legitimise and protect the effort (Grima-Farrell, Reference Grima-Farrell2018; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Camburn, Kelcey and Quintero2021; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2005, Reference Kennedy2016).

A focused time-use study for MTSS leadership team members could identify patterns of time allocation across professional roles (e.g., subject matter experts, administrators; OECD, 2014) and inform workflow adjustments. MTSS leadership team members’ time use, in particular, should be studied due to their critical role in guiding implementation (Michigan’s MTSS Technical Assistance Center, n.d.). Focusing on this group’s use of time may benefit future MTSS research by providing a process for teams to increase their implementation capacity (Pas et al., Reference Pas, Lindstrom Johnson, Alfonso and Bradshaw2020). Embedding this work within a theory-of-change framework would clarify the connections between MTSS and educators’ time pressures.

Framework

The researchers drew on activity theory (AT) as a conceptual lens to inform the study’s design and understanding of participants’ activities (Engeström, Reference Engeström2008, Reference Engeström2015). AT is a sociocultural framework for analysing how people collectively organise and carry out tasks within a system, emphasising the interplay between individuals, their tools, the rules governing their work, and the broader community. By using activity as the primary lens for analysis, AT enables researchers to examine the complex interactions among MTSS team members, the tools and data they use, and the policies and cultural norms that shape their work. This approach supports identifying patterns and inefficiencies, such as role overload, redundant processes, or unnecessary procedural complexity, that may not be visible in day-to-day operations. Importantly, AT helps staff evaluate where time use aligns with, or diverges from, the team’s goals, offering insight into both strengths and bottlenecks.

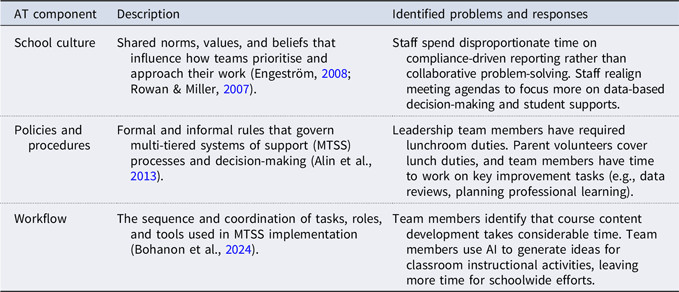

For this study, AT was applied to three interconnected categories — school culture (i.e., school mission and vision), policies and procedures (i.e., formal and informal operational guidelines), and workflow (i.e., tasks carried out by staff) — to better understand MTSS and schoolwide improvement strategies (Alin et al., Reference Alin, Maunula, Taylor and Smeds2013; Bohanon et al., Reference Bohanon, Wu, Kushki and LeVesseur2024; Rowan & Miller, Reference Rowan and Miller2007). These categories shape MTSS team activities and ultimately affect student outcomes. Studying time use informed by AT provides a structured way to diagnose system-level factors influencing staff efforts, making it a valuable tool for optimising team functioning. Table 1 illustrates how AT components relate to MTSS contexts and provides examples of how time-use studies can help identify and address challenges.

Table 1. Mapping Activity Theory (AT) and Time-Use Study Applications

Current Study

Although prior researchers have examined profession-specific or more general applications, the current study focuses on developing a process to help MTSS leadership teams reflect on their use of time. Time involved staff’s hours and minutes spent on MTSS and other school responsibilities. This information guides the current time-use study procedures. Despite significant shifts in education due to COVID-19, research on teachers’ and staff’s time use remains limited (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Camburn, Kelcey and Quintero2021). This study also aimed to develop tools to communicate insights into MTSS team members’ time to administrators. The findings may reveal how MTSS teams can adapt to post-pandemic realities. The results may also prompt further research on training, implementation, and professional development to support student outcomes. The following section outlines this study’s methods.

Methods

The researchers used a qualitative, focus group methodology to answer the study’s research questions (RQs):

RQ1: What are the specific variables to include in a time study of schoolwide leadership team members that can lead to valid and reliable data for self-reflection and sharing with administrators?

RQ2: What are the most effective methods for data collection for a time-study process for schoolwide team members?

The focus group methodology for this study included the participants, procedures, and analysis plan.

Participants

The unit of analysis consisted of individuals with perspectives relevant to the study’s aims. Two purposive sampling approaches were used. First, key informant sampling helped identify individuals with knowledge related to the RQs (Patton, Reference Patton2014). Second, elite sampling narrowed the pool of potential participants (Marshall & Rossman, Reference Marshall and Rossman1989), targeting those whose roles offered insights aligned with the RQs. Participants represented experiences with schoolwide interventions, professional development, time-use studies, technology, and districts with active MTSS teams.

The study included four participants (N = 4) from different regions of the United States, with an average of 10 years of educational experience. Two participants with expertise in content and professional development supported state-level MTSS implementation. A third conducted time-use research. This participant was a researcher who studied time use among special education classroom teachers. The fourth participant had experience with district-level MTSS and time-use studies. Specifically, the participant previously implemented time-use studies to support funding for district-level implementation of MTSS-related initiatives. All participants had experience working directly with classroom teachers on MTSS strategies. The researchers did not provide participants with professional development on time-use studies. Instead, the participants shared their experiences and perceptions of time-use studies based on the examples provided in the focus groups.

Procedures

Study procedures included focus groups to review and develop potential time-use codes and effective data collection methods or protocols. The focus groups’ purpose was to identify specific time-use processes to support MTSS leadership members in implementing schoolwide interventions. Specifically, the researchers sought to connect MTSS implementation barriers and staff workflow and to develop time-use data collection, analysis, and reporting processes. The study’s findings would support future MTSS time-use implementation research. Loyola University of Chicago’s institutional review board approved the project (approval #3430). Participants provided verbal consent to participate in the study, in accordance with the approved procedures.

Focus groups

The research involved two 1.5-hour Zoom-based focus group interviews (Archibald et al., Reference Archibald, Ambagtsheer, Casey and Lawless2019; Krueger & Casey, Reference Krueger and Casey2014). Two researchers led the focus groups. One served as the moderator, guiding the questioning route. The second served as a facilitator, recording notes and keeping track of time. A literature review informed the session questions on time-use study challenges and strategies. The first group focused on potential time-study categories for MTSS leadership teams. Specifically, the questions involved barriers to MTSS implementation (Avant & Swerdlik, Reference Avant and Swerdlik2016; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Camburn, Kelcey and Quintero2021), experiences and potential concerns related to time-use studies (Vannest & Hagan-Burke, Reference Vannest and Hagan-Burke2010), and a review of draft time-use codes for data collection (Kelly & Whitmore, Reference Kelly and Whitmore2019; OECD, 2014). Sample questions included, ‘When you think about members of schoolwide leadership teams, what are some of their time barriers related to the development and implementation of schoolwide plans?’ and ‘What would be some of the possible barriers for conducting a time study with schoolwide leadership team members?’

The second focus group involved a review of updated time-use codes (based on focus group one) and potential data collection methods (e.g., Excel, apps; Kelly & Whitmore, Reference Kelly and Whitmore2019; OECD, 2014), timeframes for time-use data collection, recommendations for analysis (Vannest & Hagan-Burke, Reference Vannest and Hagan-Burke2010), and procedures for sharing data with administrators (Carchedi, Reference Carchedi2020). Sample questions included, ‘What data collection methods (e.g., online, IOS/Android app, hard copy, Excel, Google Drive) would be most helpful in collecting time-use data?’, ‘When would be the optimal time of year for data collection?’, and ‘What is a preferable timeframe for time-study data collection (e.g., how many days should the data be collected and how often)?’ Participants received the questions in advance and could offer additional input via email. Each participant received a $200 gift card for their involvement.

Development of codes for time study

Participants reviewed potential time-study codes during both focus groups. The researchers adapted sample time-use categories from the literature (Carchedi, Reference Carchedi2020; Kelly & Whitmore, Reference Kelly and Whitmore2019; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2005; Killion, Reference Killion2023; Pas et al., Reference Pas, Lindstrom Johnson, Alfonso and Bradshaw2020). Codes included instructional tasks (e.g., curriculum planning, data collection, instruction delivery) and non-instructional tasks (e.g., paperwork, field trips, extracurricular activities). These descriptions reflected various professional roles (e.g., teachers, administrators, social workers, psychologists). Participants refined each code’s definition throughout the study.

Analysis

The researchers conducted a comprehensive analysis of transcripts using a multistage process (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994). They first developed descriptive codes based on time-study research and their initial review of focus group data. They used NVivo 14 to code the data and construct themes. Applying a constant comparative model, the researchers organised the theme structure (Bogdan & Biklen, Reference Bogdan and Biklen2007). They developed a case study report based on the analysis (Skrtic, Reference Skrtic and Lincoln1985). To ensure data trustworthiness, they employed triangulation, conducted a member check, and performed an external audit of the case report (Skrtic, Reference Skrtic and Lincoln1985). To ensure triangulation, each theme involved at least two pieces of data to qualify as a standalone construct. Each participant received a copy of the case report, along with instructions, to verify its accuracy and raise any concerns about groupthink or data interpretation (i.e., member check).

The researchers also submitted the case report and supporting data to an external researcher for a confirmability audit. The auditor examined whether the case report accurately reflected the data and whether the interpretations were free from undue bias. Because the study included a small sample (N = 4) and involved a qualitative design, readers should interpret the findings based on their transferability rather than generalisability (Skrtic, Reference Skrtic and Lincoln1985). With transferability, readers assess how closely the participants’ contexts align with their own to decide whether the results might apply to their setting.

Findings

This section includes the study’s outcomes based on the research questions. RQ1 involved identifying codes relevant to MTSS and time use. RQ2 centred on data collection procedures for developing an efficient time-use study process for leadership teams. The data came from two focus groups (N = 4) and document analysis of participants’ electronic communications.

All participants received a copy of the case study for member checking. Only one participant provided feedback, confirming that the case study reflected their perspectives. The member check results supported the accuracy of the participants’ data. The confirmability auditor agreed that the case study was grounded in the data and free from undue researcher bias.

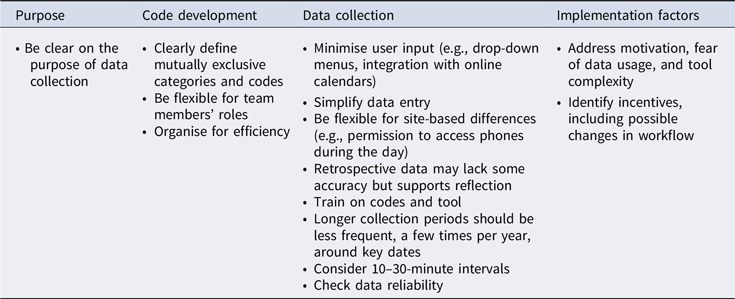

Four overall themes emerged from the data: (a) purpose-driven development (RQ1), (b) code development recommendations (RQ1), (c) data collection procedures (RQ2), and (d) implementation factors (RQ2). Table 2 includes a visual display of the study’s four major themes and their associated subthemes. The following section provides a description of each theme.

Table 2. Considerations for Conducting Time-Use Studies for Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) in Schools

Purpose-Driven Development and Code Recommendations

Study participants emphasised the need to clarify the purpose of data collection to inform time-use study processes. For instance, professional development coaches and district-level personnel may have different purposes for conducting a time-use study, necessitating different time-tracking variables. These findings align with previous research indicating that staff need to be clear about the potential applications of time-use data (Gicheva, Reference Gicheva2022). Participants also recommended that time-use codes be clear, mutually exclusive, and organised for efficiency. The codes should be inclusive and reflect the unique roles of schoolwide team members (e.g., general education teachers, school psychologists, social workers). Previous time-use studies have focused primarily on one specific professional role (i.e., social workers; Cooc, Reference Cooc2019; Grissom et al., Reference Grissom, Loeb and Master2013; Kelly & Whitmore, Reference Kelly and Whitmore2019; Vannest & Hagan-Burke, Reference Vannest and Hagan-Burke2010). In this study, the need for codes that encompass the unique roles of leadership team members was identified (OECD, 2014).

Data Collection Processes

Participant recommendations for data collection processes included ensuring user-friendly data entry and minimal user input. For example, data collection systems might synchronise with school and district calendars to reduce data entry. Additionally, participants reminded developers to consider the differences between schools when developing the interface. One participant shared, ‘… in some schools … everybody’s on their phone … in other schools … teachers aren’t allowed to use their phone … during instructional time’. The purpose of the time-use study for MTSS is to improve staff workflow rather than increase their workload with another inefficient process. These findings support previous research suggesting that time-use applications should employ user-friendly data collection platforms to reduce the burden on leadership team members (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Camburn, Kelcey and Quintero2021).

Participants also recommended that time-use participants receive training on time-use protocols. The protocol may include descriptive time codes, data collection forms, data graphs, and suggestions for analysis and reporting. This finding aligns with research that staff require training to implement new strategies effectively (Grima-Farrell, Reference Grima-Farrell2018). Participants reminded the researchers that MTSS leadership tasks change throughout the school year. Therefore, data collection must occur at critical times (e.g., quarterly benchmarking, beginning of the school year) depending on the study’s goal. These recommendations reflect the various tasks typically required of MTSS leadership team members (CEEDAR Center, n.d.; Goodman & Bohanon, Reference Goodman and Bohanon2018; Michigan’s MTSS Technical Assistance Center, n.d.). Furthermore, although staff recording their data retrospectively may be less reliable, it might allow for more effective reflection on their roles. The participants also emphasised the importance of data reliability checks, which might involve looking for patterns and noting where a staff member performed the same activity throughout the day.

Implementation Factors

Implementation factors emerged as both disincentives and incentives for time-study participation. Study participants identified disincentives, such as the complexity of the data collection process. As previously mentioned, providing user-friendly data collection tools (Grima-Farrell, Reference Grima-Farrell2018; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Camburn, Kelcey and Quintero2021) that align with the specific roles of leadership members in context may address this concern (Collins & Liang, Reference Collins and Liang2015; Hammond & Moore, Reference Hammond and Moore2018; OECD, 2014). Another disincentive involved the staff’s fear that administrators might use the data to add additional responsibilities to staff’s workload. One participant stated that some staff already feel they cannot fulfil their assigned duties due to insufficient work time. Resistance to time-use applications due to existing workflow demands aligns with current research on staff’s existing burdens (Gicheva, Reference Gicheva2022). These individuals may also be less likely to participate if they believe administrators would also use the acquired data to document their lack of effectiveness. Uncertainty regarding administrators’ intended use of the time-based data could detract from staff’s willingness to participate in the process (Gicheva, Reference Gicheva2022; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2019).

Recommendations for incentives included offering stipends or gift cards to time-study implementers. Additional incentive recommendations were more intrinsic. Participants suggested that leadership team members might view the opportunity to reflect on their time use and improve their workflow as an incentive. This reflection could lead to changes to workflow within staff’s control (Carchedi, Reference Carchedi2020) or those based on advocating with administrators (Kelly & Whitmore, Reference Kelly and Whitmore2019). However, one participant cautioned that some staff may be unwilling to release tasks from their workflow. This participant shared an example of a special education teacher who ‘didn’t like all the paperwork related to IEPs [individualised education plans], but … didn’t want to turn over extended school year reporting and work determinations to somebody else’. Therefore, researchers should not assume that reducing workflow will reinforce staff’s data collection behaviour.

Time-Study Applications

These findings reflect previous research in several ways. When developing time-use codes and tools, the nuances of school settings should be considered (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2016; OECD, 2014). Additionally, staff exhaustion may serve as both a deterrent and an incentive to implement time-use studies. Staff might view time-use studies as another burden on their busy schedules (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2005, Reference Kennedy2019). Conversely, educators may perceive time-use studies as worthwhile if they help clarify and strengthen connections between their work and the various goals of improvement plans (Collins & Liang, Reference Collins and Liang2015). Furthermore, the results of a time-use study may incentivise staff if changes in workflow could decrease exhaustion and enhance workplace satisfaction (Cooc, Reference Cooc2019; Kelly & Whitmore, Reference Kelly and Whitmore2019).

Time-use studies and activity theory

Finally, AT provided a conceptual lens for considering time as a function of interaction among individuals, the school context, and the goals and priorities of the setting (Bohanon et al., Reference Bohanon, Wu, Kushki and LeVesseur2024; Engeström, Reference Engeström2008, Reference Engeström2015). The purpose-driven design theme from this study aligns with school culture as described in AT (see Table 1). The school’s mission, vision, and goals guide the development of the time-study’s purpose. The data collection procedure theme relates to school improvement processes and MTSS. Staff require documented, efficient, and effective methods to support their school-based data collection. Lastly, the theme for implementation factors connects to workflow in AT. Leaders may need to enhance the reinforcing qualities of staff tasks while removing aversive components. Administrators may be able to guide their teams’ workflows more effectively and maximise student outcomes by considering barriers, rewards, and task efficiency. Further, time-use studies may help staff identify workflow patterns related to responding to decontextualised training. Time-use information could help teams share data and offer recommendations for identifying supports to improve the application of professional learning in their setting (Collins & Liang, Reference Collins and Liang2015; Hammond & Moore, Reference Hammond and Moore2018). Adapting time-use studies for MTSS through an AT lens may help leadership team members understand and potentially adjust their roles and professional duties (Alin et al., Reference Alin, Maunula, Taylor and Smeds2013).

The researchers’ interpretation of this study’s data and the literature review formed the basis for the following potential model of time-study application for MTSS leadership teams. These steps include identifying the purpose of the time study, developing codes, determining data collection and reporting processes, and considering implementation factors (Carchedi, Reference Carchedi2020; Kelly & Whitmore, Reference Kelly and Whitmore2019; Press & Bohanon, Reference Press and Bohanon2023). Given that the following model is based on focus group and interview data, researchers and practitioners should consider these suggestions as tentative as they approach implementing time-use studies in their setting.

Step 1. Clarify your purpose

The first step in conducting an MTSS team time-use study may be to clarify the purpose of data collection to prevent misalignment between the leadership team and administrators’ purposes for the analysis (Press & Bohanon, Reference Press and Bohanon2023). For example, team members and administrators could agree that data collection is for planning to reduce barriers to MTSS implementation rather than accountability (Gicheva, Reference Gicheva2022). They may also consider what data, if any, to share with their administrators. In their review, staff might reflect on changes they can make within their control. For instance, staff members could shorten written classroom assignments for their students, thereby reducing the time required to grade. These reflections are based on the types of tasks included in the data codes.

Step 2. Select or develop your codes

Time-use studies can require staff to efficiently differentiate among daily professional tasks (Carchedi, Reference Carchedi2020; OECD, 2014). Based on the researchers’ interpretation of the data, at least two primary time-use categories may be helpful to teams. One category involves system-centred tasks directly connected to MTSS schoolwide systems. For example, these codes may include planning, providing professional development, reviewing schoolwide data, or preparing for meetings. A second category focuses on student-centred tasks that involve direct support to students. These tasks may involve preparing for and delivering instruction, documenting compliance or accountability, tutoring, and supervising students in non-classroom areas. Staff may also include options for self-defined tasks as they arise (e.g., home visits, community events). Time-use categories should be piloted before implementing the process on a larger scale. Once the codes are developed, the next step in the time-use process may be to develop your data process.

Step 3. Develop your data collection process

Data collection processes can range from paper-and-pencil methods to dedicated online time-tracking software (Carchedi, Reference Carchedi2020; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Camburn, Kelcey and Quintero2021). Tool selection and development may depend on the staff’s comfort with technology and their professional context (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Creagh, Stacey, Hogan and Mockler2024). For example, a Google Sheet tracking form might provide a simplified way to track their data over time. However, it may be impossible for staff to always have access to an electronic device to record their time use. Leadership team members may need online and paper versions of data collection tools to record their time use. Staff could use a hard copy of a code-tracking sheet during the day and record their data in an online system at the end of the day (Vannest & Hagan-Burke, Reference Vannest and Hagan-Burke2010).

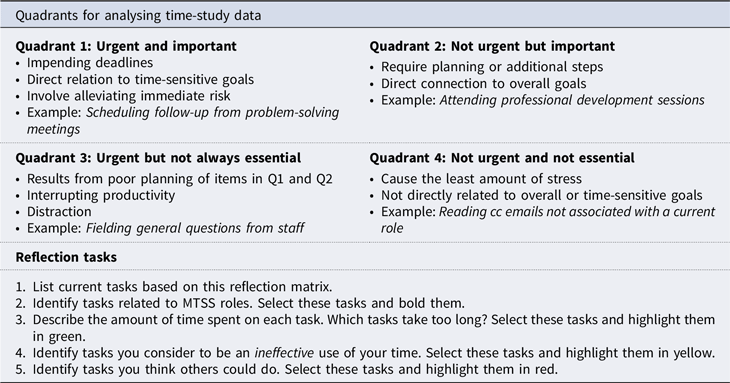

Step 4. Implementation of the time study

Implementing time-use studies requires staff motivation to enter, organise, analyse, and potentially review data with stakeholders. Recommendations for incentivising participation include offering stipends or gift cards, and improving workflows based on data insights. The changes that result from time-use analysis alone could be rewarding for some staff. However, educators need strategies to identify time-use patterns to pinpoint and recommend changes. As an example, leadership team members may benefit from completing a time-use matrix, such as the one found in Table 3. This review may help staff identify patterns for data tracking and potential adjustments to their workflow (Dmytryshyn & Goran, Reference Dmytryshyn and Goran2022). A time-use matrix helps staff organise current workflow using four quadrants (Covey, Reference Covey2020): (a) urgent and important, (b) not urgent but important, (c) urgent but not essential, and (d) not urgent and not essential to their work. Table 3 provides example responses for each quadrant. Staff can reflect on which tasks take too much time, which are least effective, and which others they could handle (Carchedi, Reference Carchedi2020). They can also identify tasks for specific time-use data tracking.

Table 3. Tool for Analysing Time Allocations for Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) School Leadership Team Members

Note. The researchers adapted this table from Carchedi (Reference Carchedi2020) and Covey (Reference Covey2020). The schoolwide team members may use this table to reflect on their time-study data.

Step 5. Organising time-use data

Depending on the data collection process, generating reports for administrators may involve tools such as Excel, Google Sheets, or built-in features of online applications. These reports might include graphs highlighting areas of concern (Carchedi, Reference Carchedi2020). As staff develop their graphs, they can focus on the number of minutes spent on a given task for the week and the average number of minutes per day. For instance, a staff member might spend 180 minutes over a given week preparing student activities (e.g., field trips, photocopying), with an average of 60 minutes per day. Additionally, each week may have a different rhythm of activities. To address this concern, staff could create a separate graph for each week of data collection. Regardless of the way the staff organise their data, they need to consider how, if at all, to share their results with their administrators.

Step 6. Sharing time-use data (optional)

Once staff identify areas for improvement, they can prepare to meet with administrators to discuss potential workflow changes (Cooc, Reference Cooc2019; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Creagh, Stacey, Hogan and Mockler2024). This preparation could increase the chances of a productive meeting and reduce the risk that administrators will use the data for punitive purposes. Carchedi (Reference Carchedi2020) outlined steps for addressing data-revealed issues. Staff can clarify the meeting’s purpose — whether they will adjust their workflow independently or seek administrative support. Next, they could bring relevant data to guide the discussion. Team members can also identify potential workflow solutions before the meeting with administrators, to prevent the perception that they are simply complaining. For instance, a recommendation might include asking volunteers to assist with logistical duties for organising a school dance. While staff may hesitate to give up meaningful tasks, handling them more efficiently can improve wellbeing and productivity.

Leadership team members may want to align suggested workflow changes with administrator priorities. For example, a discipline dean may identify that they are spending considerable time addressing low-level behaviour (e.g., students not having classroom materials). They could develop a plan to clearly differentiate between classroom management and administratively managed problem behaviours. This policy could free up time for the dean to respond to more problematic behaviours and focus on schoolwide prevention strategies (Pas et al., Reference Pas, Lindstrom Johnson, Alfonso and Bradshaw2020; Sears et al., Reference Sears, Xu and Simonsen2025; Tefera et al., Reference Tefera, Siegel-Hawley, Sjogren and Naff2024). Each step in the time-use process could enhance team operations, improving job satisfaction. However, these recommendations must be considered in light of the study’s limitations.

Limitations

This study includes several limitations. One limitation of this study was the small sample size, which decreased the generalisability of the findings. Qualitative research focuses on transferability, relying on the reader’s ability to apply the conclusions to their context (Patton, Reference Patton2014). The researchers provided a thick description of the study participants’ backgrounds to support the reader’s ability to transfer the findings. Future studies should include larger sample sizes for more comprehensive data analysis to improve transferability. Additionally, this study focuses on the perspectives of MTSS staff based in the United States. While countries around the world implement MTSS (de Bruin et al., Reference de Bruin, Killingly, Graham and Graham2023), the specific pressures on leadership team members’ time use may vary by country. Therefore, future studies should incorporate the perspectives of MTSS leadership teams from a broader international array.

Given the small sample size and the focus group methodology, it is possible that biases arose from groupthink. This type of bias could limit the credibility of the data in representing each participant’s viewpoint. The researchers attempted to strengthen the case report’s credibility through triangulation, member checking, and a confirmability audit, enhancing the trustworthiness and transferability of the data (Skrtic, Reference Skrtic and Lincoln1985). In particular, participants had the opportunity to review the case report independently and provide feedback to address any concerns about the data summary. Each of these steps potentially enhanced the overall credibility of the report and its findings. Future research should incorporate mixed methods to assess the feasibility and acceptability of time-use studies for MTSS teams. Researchers could use interviews, survey data, and permanent products such as time-use logs to enhance the analysis’s utility, credibility, and rigour. Relatedly, participants described their recommendations rather than implementing time-use protocols. Therefore, claims about improved workflow or wellbeing reflect participants’ perceptions and remain hypothetical. Researchers of future studies should test these claims through time-use study applications and longitudinal implementation data.

Conclusion

Even before the pandemic, school staff faced more tasks than they could complete each day. In this study, researchers analysed data collection codes and tools through focus groups with education and MTSS leadership experts to create a time-study protocol. School leaders might use MTSS-related time-use studies to help staff reduce non-essential tasks and improve workflow. This research is an early attempt to adapt time-use methods to schoolwide MTSS leadership needs. If successful, time-use studies could help close the research-to-practice gap (Grima-Farrell, Reference Grima-Farrell2018) in MTSS. The time-study process can also support other schoolwide teams, such as groups focused on school improvement, to identify methods to improve time margins for their work and wellbeing. By saving time, leadership teams could focus more on achieving meaningful student outcomes (Choi et al., Reference Choi, McCart and Sailor2020; Swain-Bradway et al., Reference Swain-Bradway, Lindstrom Johnson, Bradshaw and McIntosh2017; Tefera et al., Reference Tefera, Siegel-Hawley, Sjogren and Naff2024). More research is needed to identify time-use codes and data collection procedures to best support MTSS leadership.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Sarah Weaver from Charlevoix-Emmit ISD and Sam Patton from Michigan’s MTSS Network for reviewing this paper.

Funding statement

This research was supported by a Research Stimulation Grant (#1130) from Loyola University of Chicago.

Competing interests

The lead author of this paper is a member of the AJSIE Editorial Board.