Few periods have received greater attention in American political history than Reconstruction and its downfall.Footnote 1 Scholars have variously attributed the end of Reconstruction to the Compromise of 1877, the growing indifference of northern Republicans, congressional repeal of most of the enforcement acts, and the violence of white paramilitaries.Footnote 2 While most of the historiography uses the familiar temporal endpoint of 1877, some thoughtful works have extended the Reconstruction era through and beyond the 1890s.Footnote 3 This article joins these scholars in questioning the traditional abandonment narrative in two novel ways. Firstly, by critically examining the material support for the enforcement of Black voting and civil rights in the South, I argue the Republican commitment to equal protection extended through the mid-1880s, when Democrats won back the White House for the first time since the Civil War. In support of this claim, this article draws on financial and personnel data from the Department of Justice (DOJ) which have been overlooked by previous scholarship.Footnote 4 Second, despite the continued material support for enforcement, federal attorneys proved dramatically less successful in securing convictions by the mid-1870s. I argue the Supreme Court’s interventions were responsible for changing the jurisprudential landscape and eroding the capacity of the federal government to protect Black Republicans from insurgent violence. Judicial decisions also facilitated a large divergence between Republican electoral fortunes at state and federal elections by excluding state elections from federal protection, thereby prompting a wave of fraud and intimidation that furthered the consolidation of reactionary southern state governments. This article estimates the Court initiated an 8-percentage-point drop in Republican vote-share in southern state elections, potentially changing outcomes in 30% of gubernatorial races between 1876 and 1890.

In addition to historiographic contributions, this article contributes to the regime literature in American Political Development (APD). Responding to the legal model of judicial behavior embedded in American law schools, political scientists have developed an array of sophisticated theories to explain the actions of judges beyond legal-logics.Footnote 5 Contrary to the legal model, which views “law as more or less autonomous in relation to the larger society,” theories in APD have stressed the political and social entanglements of the judiciary.Footnote 6 These accounts have paid particular attention to the “political construct[ion]” of judicial action, explaining legal decisions as the outcome of broader coordination with the president, Congress, or political parties.Footnote 7 Political scientists have ably demonstrated moments when judicial actors “take on those powers, responsibilities, and agendas that are assigned to them by other power-holders.”Footnote 8 As a subfield, however, APD has paid less attention to moments when judges act in contravention of the agendas and powers purportedly assigned to them. One implication of this underspecification is that regime theories have given the Court a democratic imprimatur, owing largely to their concentration on moments of cooperation.Footnote 9 In arguing against scholars who consider the Reconstruction Court to have largely accommodated the dominant Republican regime, this article poses a challenge to the democratic implications common in the regime literature.Footnote 10

This article considers the effects of four landmark Supreme Court decisions that narrowed or invalidated laws passed by Reconstruction Republicans: U.S. v. Cruikshank, U.S. v. Reese, U.S. v. Harris, and the Civil Rights Cases. Footnote 11 In discussing the repercussion of each, I argue the Court was not simply mediating intraparty conflict but forging its own path toward a postbellum political settlement. Central to this jurisprudential vision was Justice Joseph Bradley, who was in the majority in each decision. While he is the primary author of only the Civil Rights Cases, Bradley’s circuit court decision formed the basis of the full Court’s holding in Cruikshank. Furthermore, as will be discussed, there is strong evidence that Bradley’s draft in Reese formed the basis of the Court’s ultimate opinion. In addition to demonstrating the full Court’s deviation from central tenets of Republican Reconstruction, I pay particular attention to the constitutional vision of Justice Bradley.

Using original archival research in the Bradley Papers, this article suggests the constitutional architecture Bradley enacted was a product of his long-standing political vision and fear of Black equality.Footnote 12 When his benefactor, Senator Frederick Frelinghuysen—responsible for securing Bradley’s appointment—presented Bradley with an alternative path, Bradley split with Frelinghuysen, President Grant, and the Republican Party. Rather than inheriting an agenda from those who appointed them, Bradley and the Court implemented their own vision.

Entrepreneurship is a slippery concept. An early political science application came from Robert Dahl who defined the concept minimally as someone who “uses [their] resources to the maximum,” is not the “agent of others,” and “would make [themself] felt.”Footnote 13 A more systematic definition came from Daniel Carpenter who conceptualized entrepreneurs as those who “introduce innovations” and “convince diverse coalitions … of the value of their ideas.”Footnote 14 Adam Sheingate further refined the concept as “creative, resourceful, and opportunistic leaders whose skillful manipulation of politics somehow … creates a new institution or transforms an existing one.”Footnote 15 This article takes Sheingate’s definition as a starting point and then explores the unique constraints and opportunities available to judicial entrepreneurs. Justin Crowe has applied Carpenter and Sheingate’s definition to explain judicial autonomy focusing on reputations, networks, and measured action as three elements of successful entrepreneurship that resulted in institutional change.Footnote 16 Although he uses the concept of political entrepreneurship to explain judicial autonomy, Crowe does not actually theorize what is unique about judicial entrepreneurship, a term that is absent in his writing. Carpenter and Sheingate’s framework and Crowe’s application thereof are good jumping-off places for theorizing judicial entrepreneurship. Judges operate in unique institutional environments and have separate normative mandates from actors in the executive and legislative branches.

Joseph Bradley succeeded because he was able to leverage his politic network, establish a sterling reputation among the other justices, and construct an issue-area monopoly. His political network served to downplay the scope of his incursion and included emissaries like Martin Ryerson (former New Jersey Supreme Court judge), George Harding (a lawyer whose brother edited the influential Philadelphia Inquirer), John W. Wallace (the reporter for the Supreme Court and a Philadelphia lawyer), and John Stockton (senator and powerful New Jersey Democrat who worked for railroads with Bradley).Footnote 17 The bipartisan group supporting Bradley had less ideological cohesion than professional interests—most had known Bradley through their work with New Jersey and Pennsylvania railroad businesses. Bradley’s network ingratiated him with prominent legal writers like Issac Redfield, who would later extol Bradley as “among the ablest and best of men and judges,” and ensure readers that “[t]here can be no question … that the grounds upon which Mr. Justice Bradley holds the provisions of the law [the Enforcement Act] … to be unconstitutional and a usurpation of the field of exclusive state legislation, are most unquestionable.”Footnote 18

As a polymath who frequently sketched arithmetic drawings and proofs in the margins of his law notes and diaries, Bradley was internally regarded as the intellectual center of the Reconstruction Court.Footnote 19 Owing to his “ingenuity, craftsmanship, lucidity, and eloquence,” Bradley was the go-to justice for many on the Court and was one of the few “near-great” justices “provid[ing] the intellectual leadership on the high bench in the latter decades of the nineteenth century.”Footnote 20 His main antagonist on the Court, Justice Miller, had to concede that “Bradley himself had both the learning in and out of his profession, and the native ability which justified his ambition [to be chief justice].”Footnote 21 Bradley routinely provided Chief Justice Waite with draft opinions that became, with minimal changes, the opinions of the full Court. After one such draft, Waite sent a letter to Bradley saying, “[w]ith many thanks. Had it not been for the within [draft opinion], I could have never won your approbation on my own.”Footnote 22 In addition to using Bradley’s drafts, Waite frequently used Bradley as a sounding board for opinions that the chief originated. He would send notes such as, “please examine and criticize” attached with his draft opinions that Waite sent to Bradley prior to circulating to the whole bench.Footnote 23 Bradley worked hard to distinguish himself on the Court, becoming “the Court’s expert in many technical areas.”Footnote 24 In one of Waite’s many notes soliciting Bradley’s legal advice, he wrote, “there is no help in such matters that I value more than yours.”Footnote 25 While Bradley was known as “a strong judge in any field from patents to the law of nations,” he distinguished himself in the area of civil rights and federalism.Footnote 26 This was partially due to the fortuity of becoming the circuit justice for the Fifth Judicial Circuit, covering six southern states ranging from Texas to Louisiana to Florida. When Bradley rode circuit, he was inevitably confronted with cases involving violations of federal civil rights law, although this trend diminished after Cruikshank took the wind out of such prosecutions. Likewise, Bradley would see firsthand―at least one term every two years in each of the districts of the Fifth Circuit―the progress of Reconstruction in the South.

Bradley’s network helped minimize the northern public response to his legal efforts to undermine Reconstruction. His reputation cultivated on the Court bought him the goodwill and adherence of the justices, especially during the time of “consensual norms” that heavily favored acquiescence rather than dissent from the opinions of the other justices.Footnote 27 Bradley’s issue-area monopoly furthered the degree of deference the other justices showed him on matters of race and federalism arising out of the Fifth Circuit. Jointly, these resources enabled Bradley to refashion postbellum constitutionalism and bring a pliant Court along with him, even when legal constraints might have otherwise deterred such action.

As will be shown, the Court deviated not because legal constraints required it but in spite of those constraints. Furthermore, by imposing a highly formalistic interpretation of the Reconstruction Amendments and statutes, the Court was drifting far from their Republican authors, “most [of whom] believed Congress already had the power under the Thirteenth Amendment, the Guarantee Clause, and other constitutional provisions to pass the rights legislation they believed necessary to protect persons of color.”Footnote 28 As Mark Graber has observed, save Representative John Bingham, none of the framers of Reconstruction could imagine courts would invalidate acts of congress meant to protect freedpeople and loyal whites in the South.Footnote 29 In reinterpreting the Court’s role in Reconstruction and documenting continued material support for civil and voting rights enforcement, this article challenges standard historiographic temporalities, adds to an underspecification in the regime literature, and asks judicial scholars to consider how and why legal constraints can cease to constrain at pivotal junctures.

The Court and Reconstruction

The Supreme Court precipitated a restoration of conservative, white southern governments and the consolidation of one-party rule between the years 1874 and 1883. Starting with Justice Bradley’s circuit decision in Cruikshank, in June of 1874, and culminating with Bradley’s decision for the full Court in the Civil Rights Cases, in October of 1883, the justices’ opinions directly encouraged extrajudicial violence by releasing notorious white-supremacist prisoners, invalidating key Reconstruction statutes, and signaling the Court would not sanction the constitutional revolution intended by the Reconstruction Amendments. While much scholarship has examined the differences between liberal and stalwart Republicans during Reconstruction through the statements of congressmen and elite newspaper editors, roll calls and election returns suggest the Republican Party’s enduring commitment to protecting civil and political rights for African Americans.Footnote 30 Civil rights were a fluid set of legal privileges that expanded as Reconstruction progressed. As expressed in the Civil Rights Act of 1866, they were thought to be the essentials of citizenship, including the rights to make and enforce contracts, to sue and be sued, to testify, to convey real and personal property, and to “full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property,” all on the terms “enjoyed by white citizens.”Footnote 31 This vision of civil rights―meant to repudiate southern Black Codes and incorporate freedmen into the Republican vision of free labor―commanded wide majorities in each legislative chamber, enabling Republicans to enact it over President Johnson’s veto.Footnote 32 While excluding suffrage, this vision of civil rights was capacious. The Civil Rights Act extended federal jurisdiction to an unprecedented extent, granting, “exclusively of the courts of the several States, [federal court] cognizance of all crimes and offences committed against the provisions of this act,” thereby making the federal government the guarantor of the essentials of the free labor system and the physical protection of African Americans.Footnote 33

The Fourteenth Amendment, passed by Congress and sent for ratification within months of the Civil Rights Act, was meant to provide a stronger constitutional foundation for this vision of civil rights. Far from an invitation to the judiciary to use the amendment to police legislative power, it was intended as a broad articulation of “the general principles of equality, individual rights, and [simultaneously] local self-rule.”Footnote 34 With the Amendment out for ratification, the fall election turned into a popular referendum on the Republican vision, resulting in an “emphatic victory in all the northern states.”Footnote 35 Southern legislatures followed suit by passing their own equivalent civil rights laws, including South Carolina (1869), Texas (1871), and Mississippi, Louisiana, and Florida (1873).Footnote 36 Congress reenacted the text of the Civil Rights Act in 1870 as part of the First Enforcement Act with only three Republicans across both chambers voting no.Footnote 37 As judged by voting records in state and federal legislatures, overwhelming majorities of Republicans repeatedly sanctioned federal guarantees of civil rights, particularly the protection of African American safety and equal market participation under the vision of free labor.

Political rights, which encompassed the right to vote and corresponding rights of office-holding and jury service, were guaranteed to Americans irrespective of race through the Fifteenth Amendment.Footnote 38 First instantiated in the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, which required southern states to readopt constitutions guaranteeing Black male suffrage as a precondition to reenter the union, Republicans widely embraced federal protection for Black male suffrage in the First Enforcement Act.Footnote 39 The act ensured voters in the several states were “entitled and allowed to vote at all such elections, without distinction of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”Footnote 40 As with the Third Enforcement Act (KKK Act), passed a year later, a supermajority of Republicans supported expansive voting protections, with only two Republican senators and one Republican congressman voting in opposition.Footnote 41 The enforcement acts, particularly the KKK Act, were strongly associated with President Grant who urged congress to pass legislation giving the federal government authority to protect freedpeople.Footnote 42 With southern conditions salient for voters in 1872, the Republican Reconstruction plan won an overwhelming victory in the presidential election. Receiving the party’s largest popular majority in the nineteenth century, Grant carried every northern and western state, as well as eight southern states, for a total of 286 electoral votes to Horace Greeley’s 66.Footnote 43 While historians have made much of the Liberal Republican breakaway in 1872, the faction died as a coherent movement with its resounding defeat at the hands of the stalwarts. Furthermore, Black voters overwhelmingly supported Grant. The party ran on a platform of “[c]omplete liberty and exact equality in the enjoyment of all civil, political, and public rights … effectually maintained … by efficient and appropriate State and Federal legislation.”Footnote 44 Clearly, the party’s commitment to Black suffrage remained alive and well.Footnote 45

Social rights were contested—encompassing a range of privileges from public accommodations to integrated schools to interracial marriage.Footnote 46 Thus, a full embrace of the concept of “social equality” was beyond the pale for all but the most radical of Republicans. In antebellum America, there was intense conceptual debate over the boundaries of social rights. Conservatives used “social equality” derisively as a “shorthand for interracial sex.”Footnote 47 Abolitionists, in response to accusations of promoting interracial reproduction, tried to narrow the definition of social equality and “restrict[] [it] to the most intimate settings.”Footnote 48 The work of Radical Republicans during Reconstruction was to shift many entitlements like equal treatment on common carriers and in public theaters to the realm of “civil rights” rather than the more controversial “social rights.” The 1875 Civil Rights Act contained public accommodations provisions that conservatives derided with the tired pejorative of social rights. However, by the mid-1870s, many Republicans were persuaded that public accommodations were not simply social privileges but rather essentials to freedom and therefore civil. Legal historian Michael Klarman has called the bill the “zenith” in Republican conceptions of racial equality.Footnote 49 Amy Dru Stanley has written that the bill was the culmination of “a revolutionary transformation of Enlightenment understandings of human rights and humanity.”Footnote 50 The revolutionary transformation of the act was in its redefinition of public accommodations as civil rights, shorn of any disparaging association with so-called miscegenation. Eric Foner has written that the bill “represented a dramatic expansion of the meaning of civil rights.”Footnote 51 African Americans, in particular, defined social entitlements as civil rights. The “Colored Citizens of Kentucky” deliberated on the difference between civil and social rights:

What is ‘civil rights?’… It means to protect the citizens in the full enjoyment of every public place opened by license, protected by police and privileged by pay … the whole public should be admitted for the same price demanded to that same class of accommodations and to the same general treatment.

The convention distinguished civil rights from social rights, which they considered things like “extra meals” and the “parlor car.”Footnote 52 This strategic definition was countered by conservative attempts to lump public accommodations with miscegenation to thwart both. Kate Masur has written that “white Americans regularly ‘stretched’ and ‘shifted’ the blurry boundary between public and private, usually enlarging the private realm, to justify race-based exclusion and to stymie African Americans’ demands for dignity, access, and justice.”Footnote 53

While the Republican embrace of a broader conception of civil rights through the 1875 act is sometimes dismissed as simply the work of “a handful of radical Republicans” to honor the passing of Charles Sumner, it is more plausible the bill represented the true position of the congressmen who voted for it.Footnote 54 Ever since Charles Sumner introduced the original act in 1870, it garnered increasing congressional support with each of his subsequent attempts. The party platform called for equality in “public rights” in both 1872 and 1876, and President Grant called for the bill’s passage in his second inaugural, before Sumner’s death.Footnote 55 The bill was enacted after Democrats regained the House and after the controversial equal access to common schools provision was dropped.Footnote 56 President Grant signed the law. After Bradley partially invalidated it in 1883, discussed below, most Republican-controlled northern legislatures responded by passing parallel state laws.Footnote 57 Illinois’ civil rights law is exemplary. Introduced in 1885 by the state’s first African American legislator, Republican John W. E. Thomas, the bill provided for the “equal enjoyment for the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges … regardless of color or race,” under penalty of fine.Footnote 58 The bill was primarily a Republican effort but gained a fair amount of Democratic support as well, suggesting the success of redefining public accommodations as civil rights, at least in the north. In fact, Black activists launched a campaign in every northern state to pass civil rights legislation. Eighteen states did so, some with Democratic support. These state civil rights acts “provided more protection for African American’s rights” than the federal bill because of their surer constitutional footing.Footnote 59 The raft of state legislation reinstating what the Supreme Court struck down is strong evidence the Court was out of step with the Republican base. As other scholars have noted, “the Supreme Court was not merely reacting to political developments or public sentiment; it played an active role in destroying the rule of law.”Footnote 60 Minisha Sinha has gone so far as to say that “time and time again, the court’s majority followed Democratic critics of Reconstruction laws and amendments, rather than their Republican authors.”Footnote 61 This article, instead, suggests that Bradley and the Court forged their own path following Bradley’s longstanding constitutional vision.

Cruikshank and Civil Rights Enforcement

Cruikshank was first heard by Justice Bradley in the Fifth Circuit (1874), before reaching the full Court (1876). Bradley, keenly aware of the case’s importance, widely disseminated his opinion. According to his diary, Bradley printed 42 copies and sent one to each justice; members of the Senate and House Judiciary Committees; Attorney General Williams; all Fifth Circuit judges; five unnamed newspapers in Washington, New Orleans, and New York; and three legal periodicals; among others.Footnote 62 Additionally, Bradley traveled from Louisiana to Washington before releasing his decision to consult with the justices, leading some to believe it represented the “authentic exposition” of the law.Footnote 63 In coordinating with conservative legal periodicals, which lent their “intellectual capital,” Bradley attempted to legitimate the opinion as both neutral and necessary.Footnote 64 The American Law Register published the opinion in full and appended a commendation letter from editor Isaac Redfield.Footnote 65 Redfield assured readers Bradley did not “usurp authority or power, or attempt to extend his lawful jurisdiction beyond its just limits,” but acted, “within the legitimate range of his proper function.”Footnote 66 The Central Law Journal called Bradley’s decision “a very able and elaborate opinion” and referred Redfield’s commendation.Footnote 67

Despite this sympathetic reporting from a “judicial audience,”Footnote 68 Cruikshank was an earthquake to the broader public. It stemmed from a motion in arrest of judgement for three defendants found guilty of violating Section 6 of the First Enforcement Act by interfering with the rights of two Black Republicans to assemble peaceably, bear arms, and enjoy equal protection of the laws, including voting.Footnote 69 The case arose from the Colfax (Grant Parish) Massacre. After Louisiana’s contested gubernatorial election of 1872 yielded competing state governments, a group of largely Black Republicans occupied the Grant Parish courthouse claiming appointments to offices including sheriff and judge. Hundreds of white Democrats sieged the courthouse claiming the appointments and murdered the Republicans en masse.Footnote 70 Estimates of the number massacred range from fifty to one hundred and fifty.Footnote 71 The State of Louisiana brought 140 indictments but dropped charges after the prosecutor and a judge were fired upon by a crowd of vigilantes.Footnote 72 With no state prosecution forthcoming, federal prosecutors succeeded in convincing a grand jury to indict 98 defendants.

Prosecutors eventually convicted three men of sixteen counts under Section 6. Already resigned to let hundreds of perpetrators free, the federal government and Louisiana’s Republican government—which held tenuously to power after an attempted coup—put their hope for peace in these prosecutions. Bradley split with judge William Woods, invalidating Section 6, dismissing the remaining charges, releasing the prisoners, and sending the case to the Supreme Court. Bradley threw out the remaining charges for punishing individuals directly for depriving citizens of rights in the Bill of Rights, failing to allege a racial motive, and for “vagueness and generality.”Footnote 73 He tried to reassure the country that “the war of race, whether it assumes the dimensions of civil strife or domestic violence … is subject to the jurisdiction of the government of the United States.”Footnote 74 However, this was cold comfort. If the Colfax Massacre did not constitute the “war of race,” it is not clear anything would.

Cruikshank touched off a wave of extra-legal violence that had been theretofore held in abeyance.Footnote 75 Louisiana governor William Pitt Kellogg testified before a House select committee that before the circuit decision, “the constituted authorities were respected and obeyed” and “no disorders occurred.” Kellogg continued, “[t]he opinion of Judge Bradley was … regarded as establishing the principle that hereafter no white man could be punished for killing a negro, and as virtually wiping the Ku-Klux laws off the statute-books.”Footnote 76 Southern “redeemers” capitalized on Bradley’s decision with a “counterrevolutionary offensive against Republican officials” throughout Louisiana, including Franklin Parish where an organized Democratic militia seized power, setting a standard for violence that was keenly noted by reactionaries in Alabama, Mississippi, and South Carolina.Footnote 77

U.S. attorney James Beckwith blamed Bradley for an upsurge in violence following the circuit decision. “The armed White league in the South … received their only vitality from the action of Justice Bradley.”Footnote 78 He contended the decision would “cost five hundred lives between this time and November.”Footnote 79 White Democrats in Colfax “celebrated” by wantonly killing Black Louisianans.Footnote 80 Christopher Columbus Nash, a defendant at the heart of the Colfax Massacre, responded by leading armed vigilantes to oust five Republicans from office in Natchitoches and later to nearby Coushatta, where the crowd murdered three prominent Black leaders.Footnote 81 A local white supremacist newspaper responded, “All hail to the judge [Bradley] … free and unfettered, we felt that their release [the Cruikshank prisoners] was our release.”Footnote 82 Democratic newspapers, in turn, threatened Republicans with mass lynching.Footnote 83

The violence that followed Bradley’s decision was explicitly coordinated to regain political power. While some southern states were already redeemed by white-supremacist governments before Cruikshank, many were not. Republican governors still controlled well over half the states in the former Confederacy, including Alabama, Arkansas, North Carolina, Mississippi, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida. By Eric Foner’s count of the end of Reconstruction in each state, only Georgia, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia were redeemed before Cruikshank (1874), leaving the remaining South still under Reconstruction.Footnote 84 Moreover, states under Democratic control could have been won back by Republicans. The most recent elections in Virginia and Tennessee, for example, were won by Democratic governors with small margins (56% and 54%, respectively). The violence that followed Cruikshank furthered “redemption” and consolidated Democratic power in redeemed states.

Justice Bradley ultimately quibbled with an indictment that was entirely conventional.Footnote 85 Of the sixteen counts dismissed, most quoted sections of the First Enforcement Act verbatim.Footnote 86 Scholars like Charles Fairman and Pamela Brandwein have mostly echoed Bradley that the indictment was unusually inadequate. Fairman describes it as “a jungle of a document.”Footnote 87 However, attorney Beckwith’s indictment was within the norm of indictments drawn under the enforcement acts. Like other such indictments, the handwritten particularities of the indictment were inserted in a form that prefilled text quoting from the laws directly.Footnote 88

Half-written, half-typed indictments were common and suggestive of their rote nature. Every count in the Cruikshank indictment began by identifying the victims as “citizens of the United States of America, of African descent, and persons of color.” A strict hewing to the statute without much elaboration of context was a frequent feature in other indictments upheld under the enforcement acts. For example, Judge Bond upheld important parts of an indictment charging that defendants, “unlawfully did conspire together with intent to violate [the First Enforcement Act] … by unlawfully hindering, preventing and restraining divers[e] male citizens of the United States of African descent … from exercising the right and privilege of voting.”Footnote 89 The defense filed a motion to quash arguing, “the conspiracy charged … defines no crime or offence, and forbids nothing.”Footnote 90 Judge Bond dismissed this motion holding that simply identifying the statute was sufficient to sustain charges. Judge Hill upheld a similar indictment.Footnote 91 U.S. attorney Starbuck was able to secure 49 convictions in North Carolina by “merely charg[ing] the defendants with being Klan members to make them liable to prosecutions.”Footnote 92 The standards of indictments were still very much in flux by the time Bradley heard Cruikshank and certainly did not demand Bradley dismiss the counts where other federal judges had upheld remarkably similar charges.

The Cruikshank indictment is also notably similar to the indictment in U.S. v. Hall, to which Bradley was sympathetic three years prior.Footnote 93 Furthermore, Bradley divided from future justice William Woods, who ruled to uphold the Cruikshank indictments. No less an authority than Justice Joseph Story, whom Bradley deeply admired, repeatedly held that the quality of indictments should not preclude prosecution. Story wrote, “in respect to the averment, it is certainly wanting in technical accuracy and precision, and departs from the settled forms of pleading. But if it have certainty to a proper intent, and can be sustained by the rules of law, we are bound to sustain it.”Footnote 94 Story conceded that indictments could be upheld that merely repeated the language of a statute, as had the Cruikshank indictment. He wrote, “even on indictments at the common law, it is sufficient to state the offence in the very terms of the prohibitory statute.”Footnote 95 Thus, scholars should be cautious not to assess the quality of the indictments by modern standards and instead recognize they were squarely within practices of the time. This perhaps explains why attorney Beckwith complained, “if the demolished indictment is not good, I am incompetent to frame a good one.”Footnote 96

Beckwith was apoplectic. “It is clear from the printed copy of [Bradley’s] opinion, that he never had read the indictment … but has taken some person’s statement of its substance.”Footnote 97 The upshot was to severely limit the 14th Amendment only to acts of “racially discriminatory state action,” stripping the federal government’s ability to reach private individuals. Bradley went further than necessary in deciding the case, propounding in dicta on all of the Reconstruction Amendments.Footnote 98 Additionally, Bradley attached a racial motivation requirement that precluded charging political violence, something Republicans broadly intended to include.Footnote 99 Without the ability to prosecute politically motivated violence, particularly when highly correlated with race, the federal government’s efforts to enforce civil rights could easily be thwarted by defendants claiming rights denials were political, not racial.

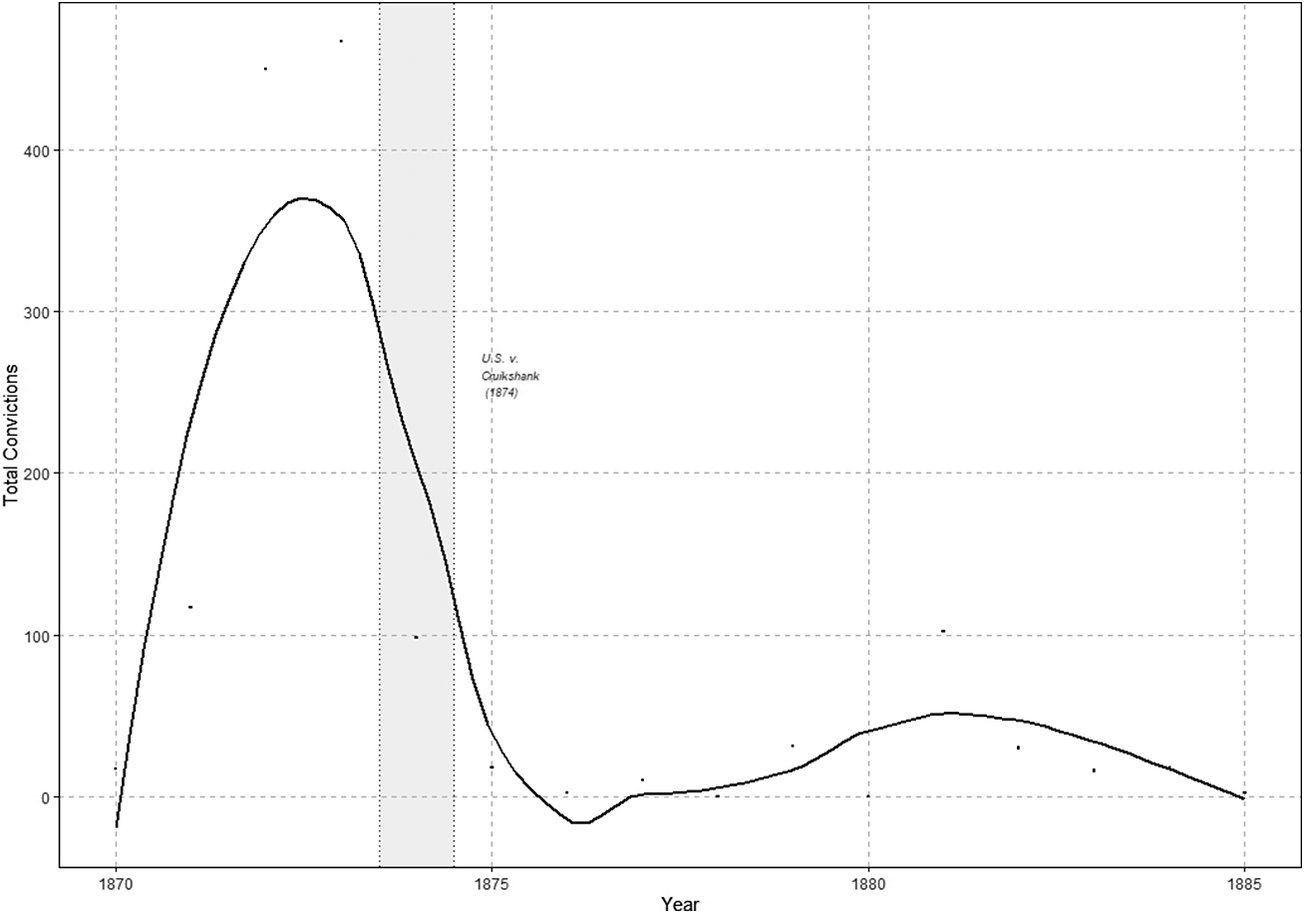

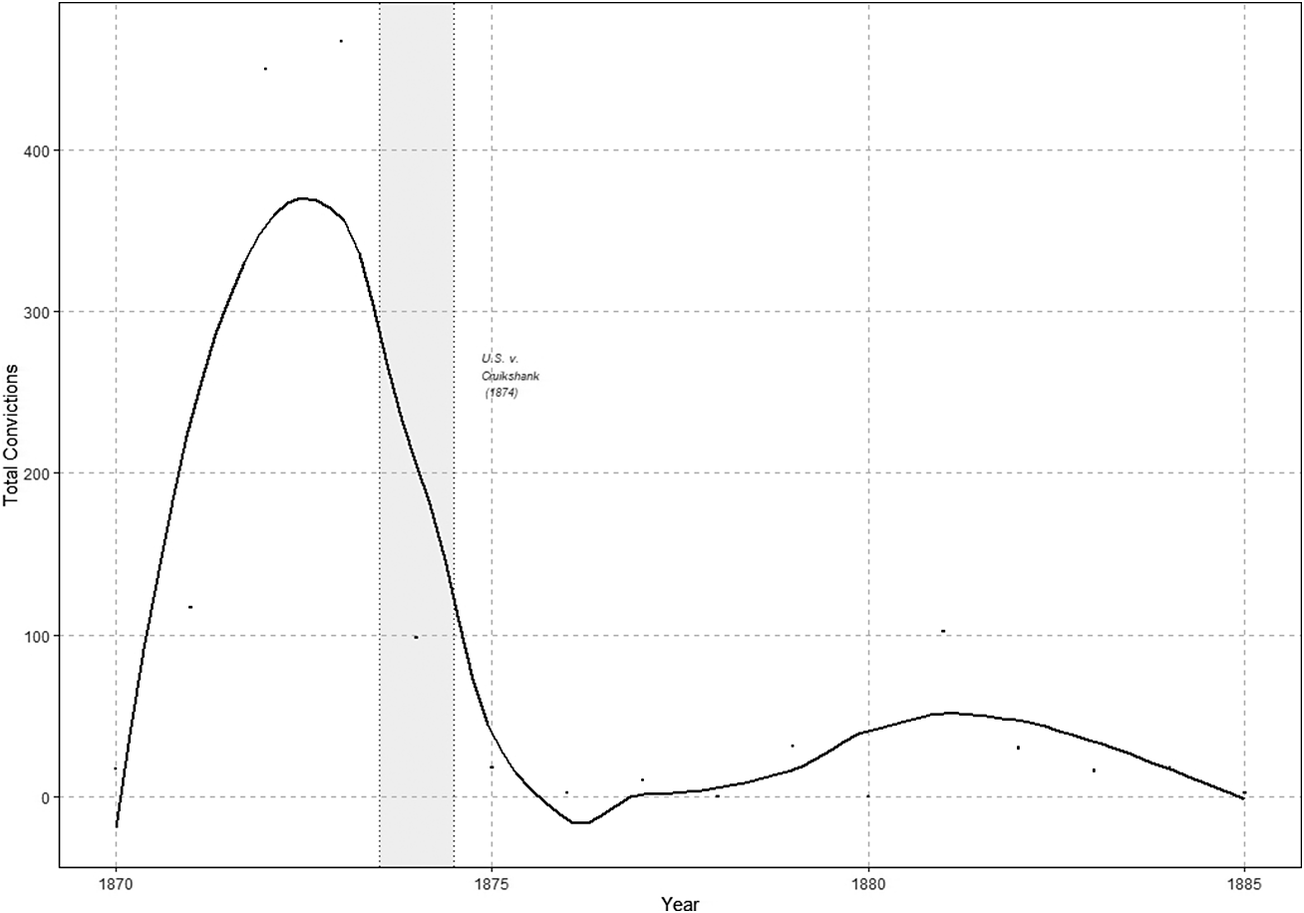

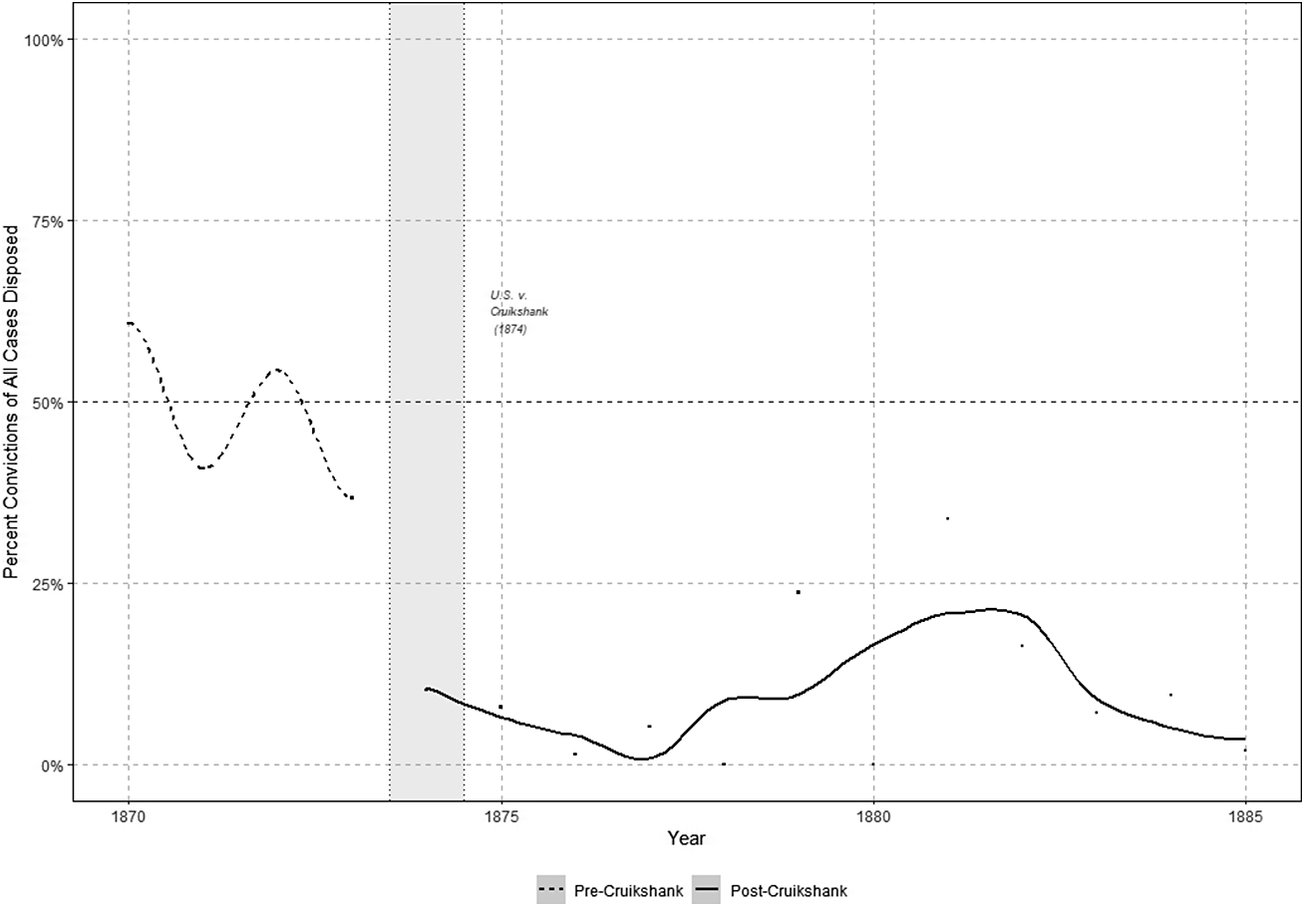

Michael Klarman has called the prospect of convictions by this time “almost impossible.”Footnote 100 Bradley dangled hope that prosecutions could continue if it could be proven that civil rights were violated on account of race. Proving racial intent, however, was elusive. Attorney General Devens wrote in 1878, “the great difficulty since the recent decision… [is establishing] the proof that the outrage was committed on account of race, color, or previous condition.”Footnote 101 A South Carolina attorney likewise wrote Devens, “there is no remedy, unless it can be proved to have been done on account of race and color, which can’t be proved.”Footnote 102 This new interpretation, largely vindicated by the full Court in 1876, was incredibly novel.Footnote 103 The justices went out of their way to decide issues not formally before them. Bradley, against the design and political interest of his party, “virtually emasculat[ed] the Civil War amendments in restoring antebellum constitutionalism.”Footnote 104 The contradictory handling of the Amendments and legislation was “not clearly understood by contemporaries, but the end result certainly was.”Footnote 105 The machinery of enforcement seized up (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Southern Convictions under Enforcement Acts (1870-1885).

Source: Annual Report[s] of the Attorney General [hereinafter, Annual Report].

Notes: Southern States include former-Confederacy and Border States (MO, KY, MD, DE, and WV) [Hereinafter, “southern states”]. Points represent annual convictions. Line represents localized moving average. Results are compatible with Wang, Trial of Democracy, which categorizes the South differently. See Appendix F.

Attorney General Williams admitted, “prosecutions under the enforcement acts at this time will amount to very little so long as the questions before the Supreme Court remain undecided.”Footnote 106 William Woods wrote anxiously to Bradley after the circuit decision, “I shall try no cases under the inforcement act … until the Court lets us have its opinion.”Footnote 107 President Grant lamented, “a great number of such murders have been committed, and no one has been punished … it is a lamentable fact that insuperable obstructions were thrown in the way of punishing these [Colfax Massacre] murderers.”Footnote 108

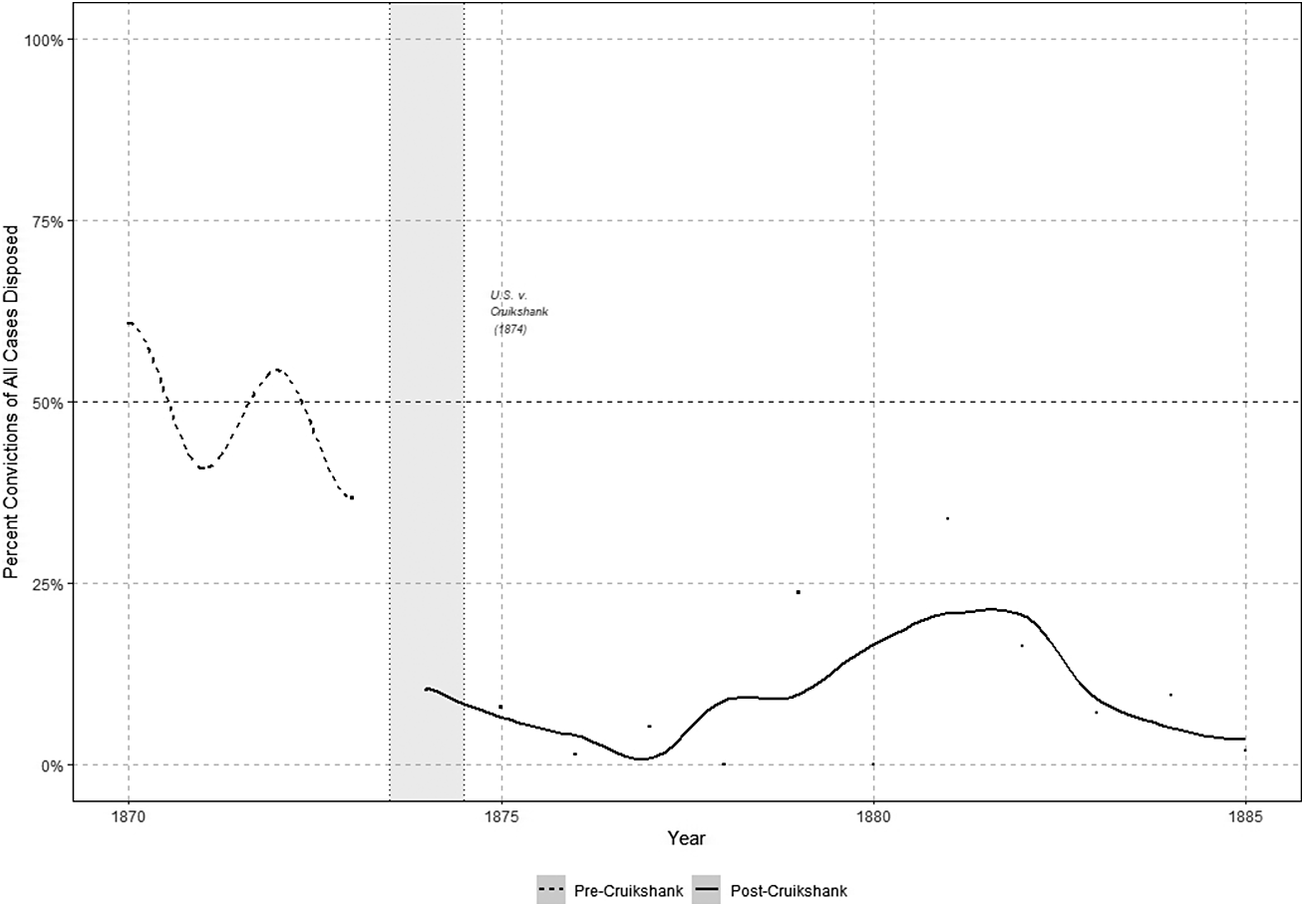

With new, tougher standards for prosecution, and lacking Section 6, obtaining successful prosecutions became formidable. Some U.S. attorneys won convictions, but the bulk of federal enforcement power expired.Footnote 109 Beyond the aggregate conviction figures, the effect of Bradley’s opinion can be seen in the percentage of cases disposed that ended in convictions (Figure 2). In the four years prior to Bradley’ Cruikshank decision, 49.0% of southern cases disposed resulted in a conviction. In the four years after, only 3.6% did. The restriction of civil rights enforcement in the South also contributed to difficulties in enforcing voting rights. Premeditated campaigns of intimidation in the months leading up to elections rendered federal enforcement at the polls ineffectual.

Figure 2. Percentage of Southern Convictions per Cases-Disposed (1870-1885).

Source: Annual Report[s].

Note: Points represent annual percentage of convictions per disposed-case. Lines represent localized moving averages.

Reese and State Elections

Chief Justice Waite, who often relied heavily on Bradley to form his opinions, dealt a serious blow to voting rights in Reese. While not the official author, Bradley no doubt played a significant role. Waite had a long-standing habit of letting Bradley write his opinions. In one note, Waite plainly stated, “I will take the credit… and you will do the work as usual.”Footnote 110 Waite’s notes indicate that he was “not … perfectly familiar with criminal law,” so he originally assigned Justice Clifford Reese. Footnote 111 When Clifford failed to convince the justices to take his modest off-ramp, Waite took the opinion back and wrote a decision largely resembling a draft Bradley circulated.Footnote 112 It is not clear whether Bradley ghost-wrote Reese, but Waite did let Bradley draft some of his most important decisions, including Munn v. Illinois the next term. Bradley joined the majority in Reese, which closely followed his draft and vision from Cruikshank.

This article is the first to systematically track the disparate fate of state and federal elections. The Court undermined Republicans by invalidating Sections 3 and 4 of the First Enforcement Act in Reese. Congress reenacted these sections in the Revised Statutes of 1874 (after the circuit decisions) and in the Revised Statutes of 1878 (after the full Court decisions), further showing that the Court was at odds with the party.Footnote 113 Republicans used these reenacted protections to continue enforcement at federal elections. Footnote 114 Reese rendered state elections unprotected, however, facilitating the collapse of the Republican state parties. While Republicans still competed in federal races, their hopes for southern state government were dashed.

Reese was decided on circuit in Kentucky during December 1873. The government agreed to “abide the result” in roughly 40 similar voting rights cases, meaning the outcome would reverberate.Footnote 115 Attorney General Williams argued Reese before the Court and provided two special prosecutors, suggesting its importance. He insisted the federal government could prosecute denials of voting rights under the 15th Amendment at both state and federal elections, and furthermore, Sections 3 and 4 were appropriate legislation to enforce the amendment.Footnote 116 These provisions jointly provided penalties for conspiring to prevent qualified voters from registering or voting “at any election.”Footnote 117

The Court invalidated these provisions because they referred to rights conferred in Section 1 using the language “as aforesaid” rather than repeating “without distinction of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”Footnote 118 On the majority’s telling, because the sections did not explicitly confine their effect to race-based denials, they were beyond congressional authority. “As aforesaid,” which plainly referred to race-based limitations in the first two sections, was not specific enough, and therefore the provisions were eliminated entirely. This highly formalistic decision—especially in so salient a case—was a radical departure from previous exercises of judicial review.

Reese was the first time the Court invalidated part of a statute because it might be applied too broadly to some plaintiff not before the Court.Footnote 119 The mode of judicial review prior involved “disallowing a certain class of applications of the statute, requiring implicit exceptions to its application, or effectively rewriting the statute to accomplish constitutional objectives while excluding the unconstitutional ones.”Footnote 120 Judge Thomas Cooley’s renowned treatise Constitutional Limitations explicated this contemporaneously: “A legislative act may be entirely valid as to some classes of cases, and clearly void as to others… . [T]he unconstitutional law must operate as far as it can, and it will not be held invalid on the objection of a party whose interests are not affected by it.”Footnote 121 Chief Justice Marshall had likewise thought, “when the words of a statute, in their most obvious sense, comprehend an offence, which offence is apparently placed by the legislature in the highest class of crimes, it furnishes an additional motive for rejecting a construction, narrowing the plain meaning of the words, that such construction would leave the crime entirely unpunished.”Footnote 122

Justice Hunt embraced that “aforesaid” meant “on account of race” writing, “the intention of Congress on this subject is too plain to be discussed.” He continued, “I cannot but think that in some cases good sense is sacrificed to technical nicety, and a sound principle carried to an extravagant extent.”Footnote 123 Throughout Reconstruction (and extending until the 1930s), unanimity was a strong norm at the Court. Typically, well above 90% of cases were unanimous, although earlier in Chief Justice Waite’s tenure, that figure was in the mid- to high-80% range.Footnote 124 In 1886, the American Law Review even wrote an editorial defending dissents, attempting to preempt a movement to legislatively prohibit the practice.Footnote 125 Therefore, even a single dissenter was rare and signified a case’s importance in an era where justices often acquiesced to the primary author. Hunt’s reading of sections in context with each other was the overwhelming disposition in lower courts. Judge Bond, for example, allowed crimes defined later in the act to be “applicable to all the antecedent sections.”Footnote 126 Contemporaries connected the subsequent violence to Reese and Cruikshank: “The late massacre at Hamburgh is unmistakably the first fruits of the Supreme Court decision, declaring the enforcement act unconstitutional, and which will be repeated again and again in almost every state in the South during the next three months.”Footnote 127

Scholars like Robert Goldman and Pamela Brandwein have argued the Court did not technically rule all efforts by Congress to protect voting rights unconstitutional. There was room for a new Congress—now partly in Democratic hands—to reenact legislation within the Court’s imposed limitations or under alternative constitutional powers.Footnote 128 Indeed, Congress did reenact essentially the same language in the Revised Statutes of 1878.Footnote 129 On the ground, however, there was great confusion about whether federal indictments would be upheld. Prior to Reese, President Grant believed the 15th Amendment authorized federal protection of state elections and cited the unanimous acquiescence of lower courts as proof. Grant unequivocally announced a position opposite of what the Court did a year later in Reese:Footnote 130

[B]y the fifteenth amendment … the political equality of colored citizens is secured … it has been held by all the Federal judges before whom the question has arisen … that the protection afforded by this amendment and these acts [the Enforcement Acts] extends to State as well as other elections. That it is the duty of the Federal courts to enforce the provisions of the Constitution of the United States and the laws passed in pursuance thereof is too clear for controversy.

What the Court did in Reese was against the expressed will of the president who appointed four of the nine justices. It was also a considerable deviation from lower courts, which largely upheld Republican Reconstruction. As Manisha Sinha has said of the federal courts’ response to Reconstruction, “the Supreme Court was the outlier.”Footnote 131 After Reese, lower courts and attorneys general took the decision to mean Congress could not interfere with state elections.Footnote 132 Judge William Woods understood the holding to apply “solely to voters at an election for state office.”Footnote 133 Judge Bond wrote, “The Court in the Reese Case decided that Sect. 5506 was not appropriate legislation to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment… . It was at a municipal election, and therefore was not within the power of Congress.”Footnote 134 Attorney General Brewster lamented attorneys’ inability “to connect their allegations specifically with the elections for members of congress.”Footnote 135 When congressional and state elections coincided, lower courts insisted that prosecutions could only be sustained for federal elections.Footnote 136 The Court’s intervention facilitated the consolidation of Democratic rule in southern states, which had started, but by no means concluded. Florida, Louisiana, North Carolina, Mississippi, and South Carolina all still had Republican governors.Footnote 137 Furthermore, state elections were close enough that Republicans could, with federal protection, contest for control.Footnote 138

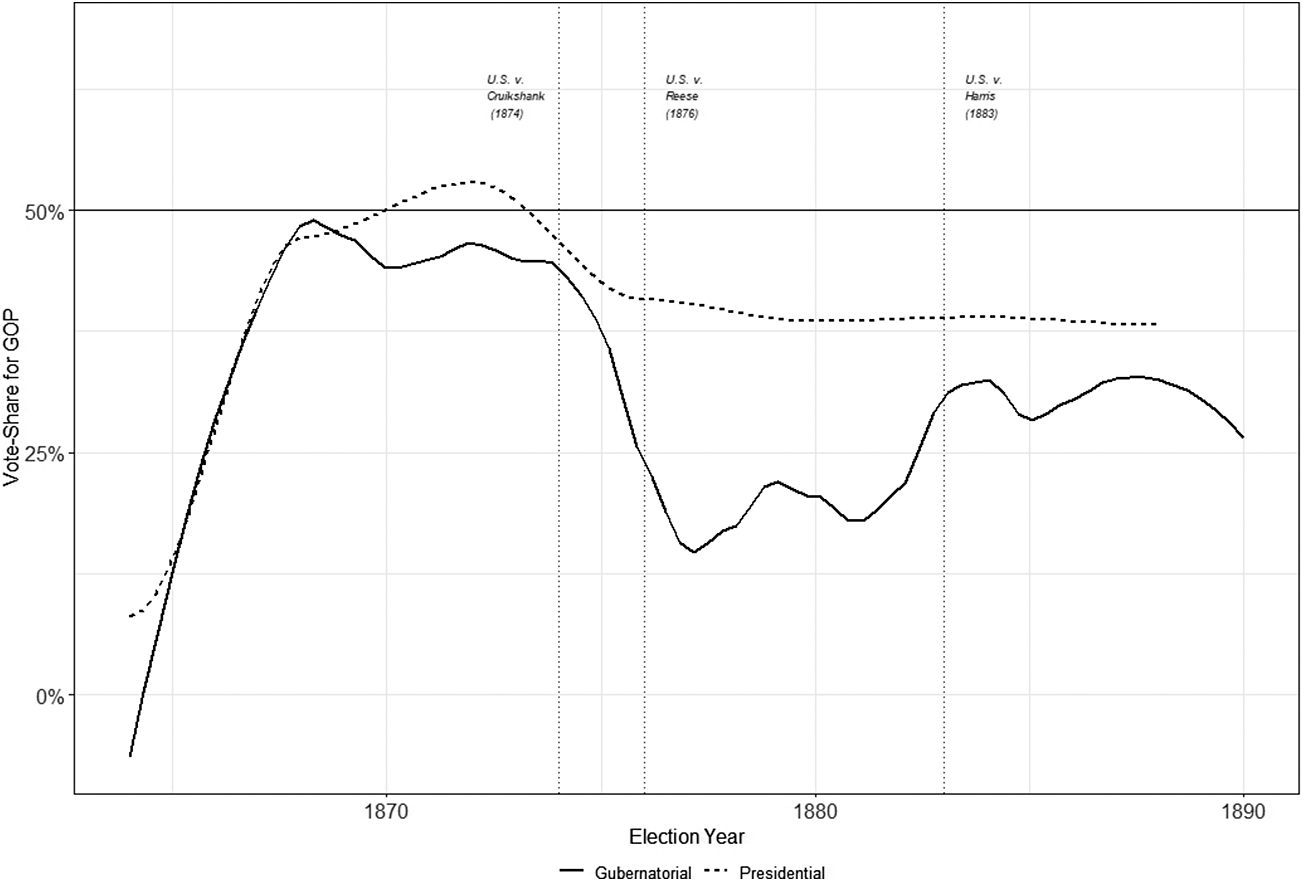

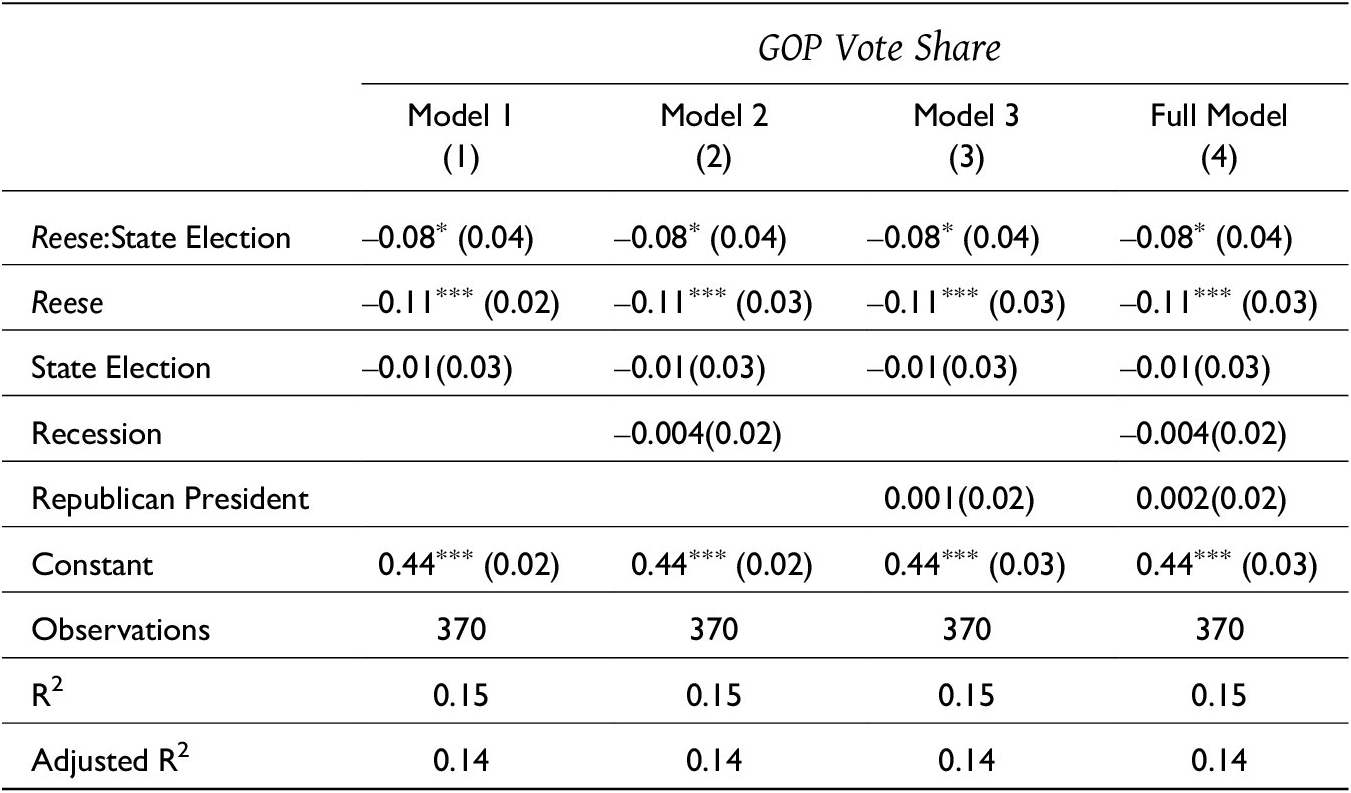

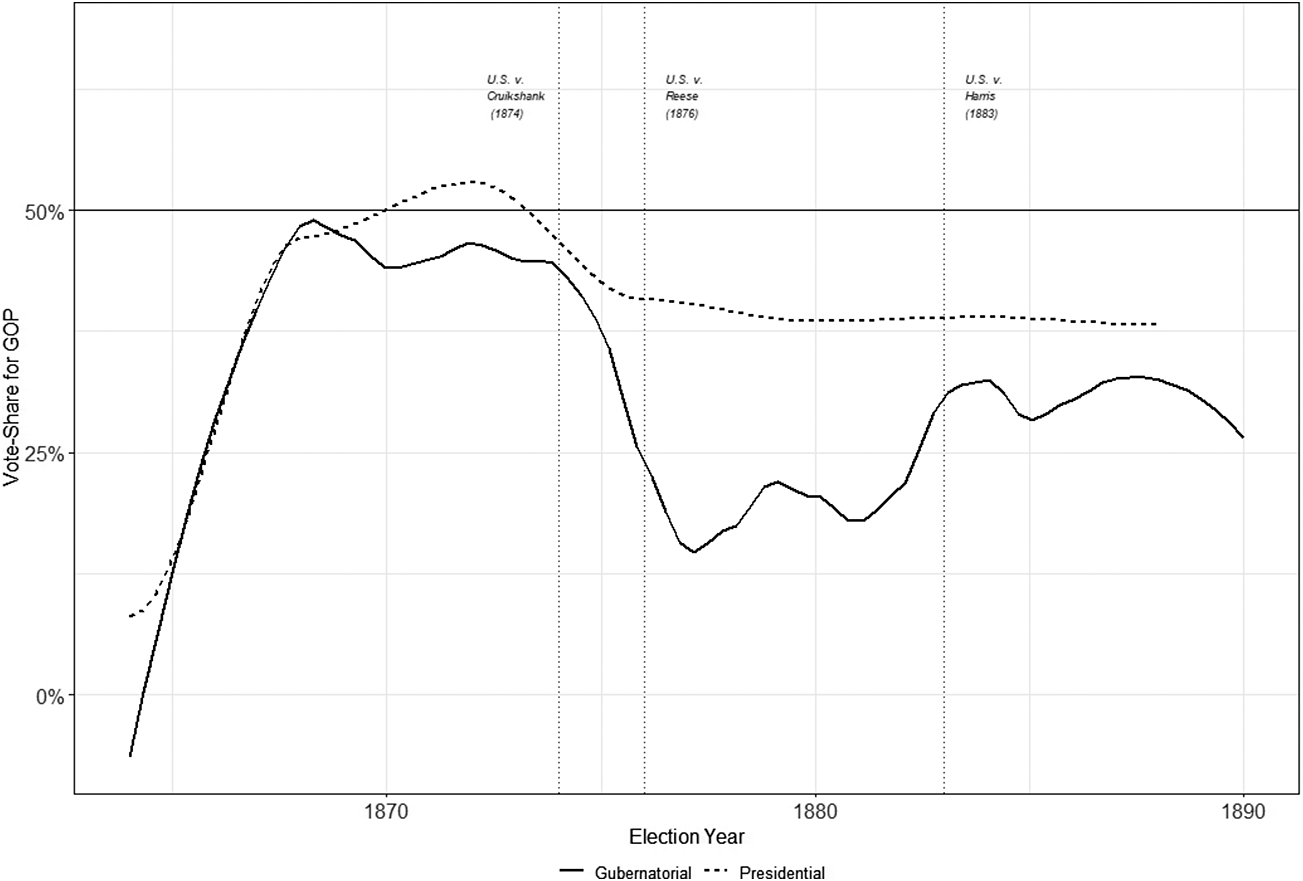

Prior to Reese (1870–1875), the average difference between Republican vote share in state versus federal elections was 0.6 percentage points. This changed dramatically in 1876 (Figure 3). Using a difference-in-differences design, this article estimates the effect of Reese was an 8-percentage-point decrease in Republican vote share at state elections (Table 1). These results are robust to alternative hypotheses including economic recessions and partisan control of the presidency. Applying an 8-percentage-point estimate to the universe of all southern gubernatorial elections between 1876 and 1890,Footnote 139 I estimate the Court cost Republicans approximately 25 out of 84 gubernatorial races—a staggering 29.8%.

Figure 3. Average GOP Vote Share in Southern Elections (1870–1890).

Source: Inter-university Consortium for Political & Social Research. Candidate Name & Constituency Totals (Vers. 5) [Hereinafter ICPSR, Candidate Totals].

Note: Federal elections are presidential while state elections are gubernatorial. Lines represent localized moving averages. Final presidential election year is 1888. Trends robust to alternative coding (Appendix B).

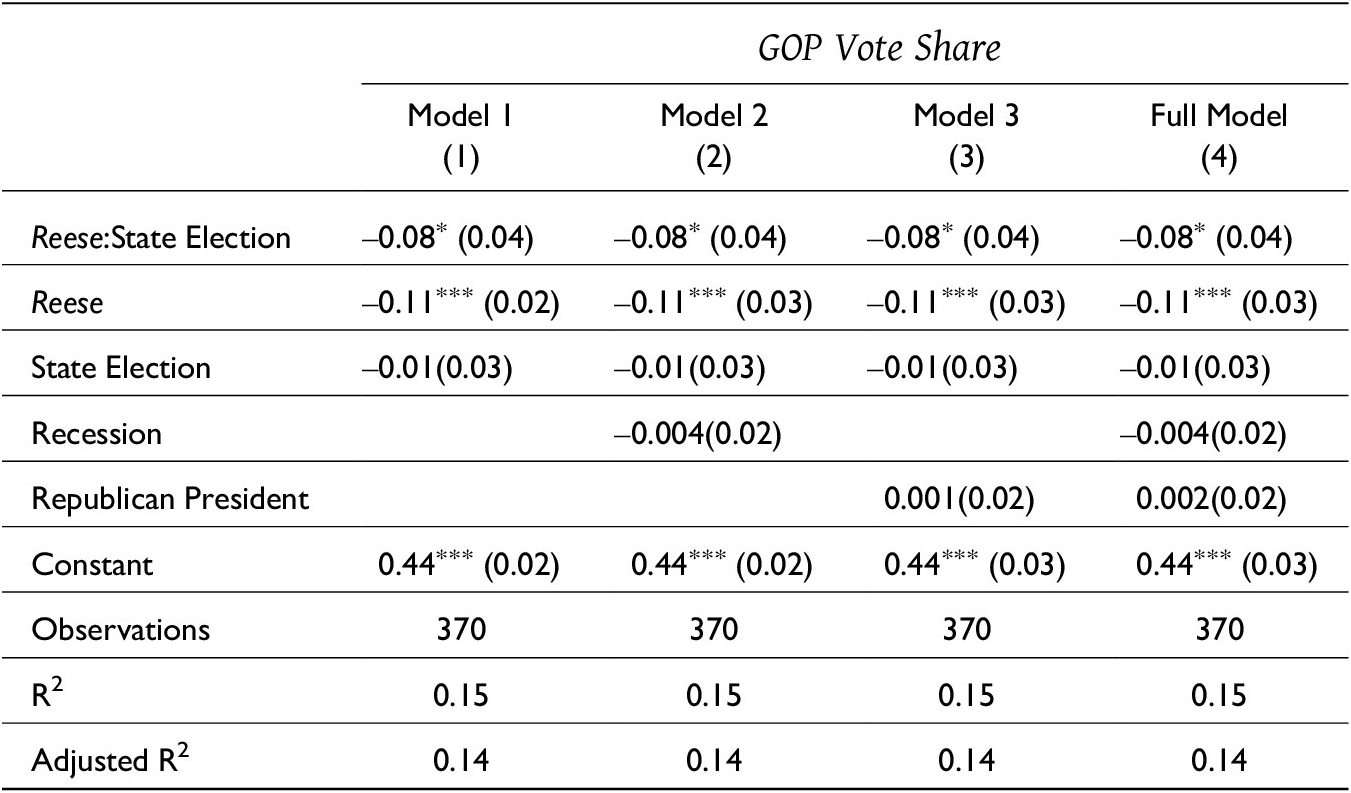

Table 1. Effect of Reese on GOP Vote-Share in Southern Elections (1870–1890)

Source: ICPSR, Candidate Totals.

Note: All southern general elections. Federal elections include congressional and presidential races. State races include governor. Two-way fixed effects and robust standard errors. Findings robust to multiple specifications (Appendix A).

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

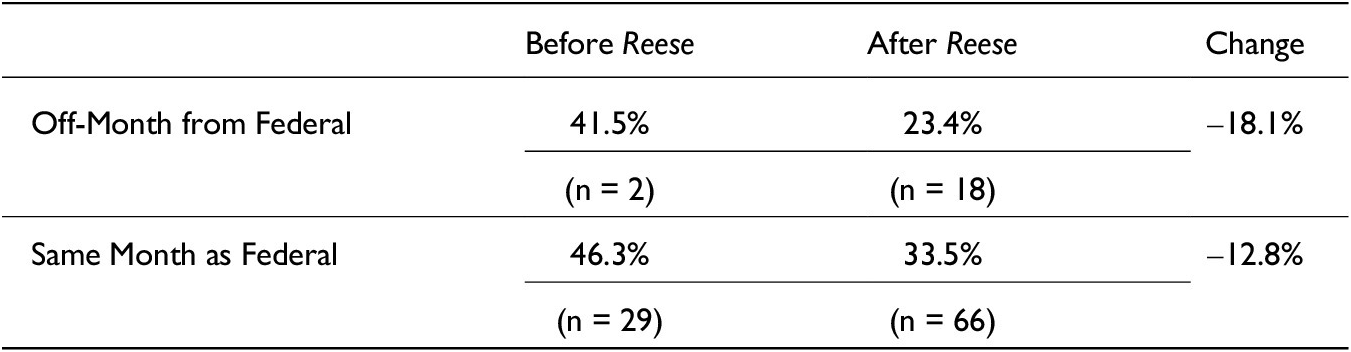

The effect can be seen in turnout rates, which “dropped off more precipitously” at gubernatorial relative to presidential races in the 1880s.Footnote 140 One mechanism by which state/federal bifurcation occurred was the advent of two-box systems, which used separated ballot boxes to “keep federal election supervisors who were observing congressional elections from discovering frauds in state contests.”Footnote 141 South Carolina, for example, passed a law separating the ballot boxes the year after Reese. “The two boxes were kept in different places, effectively eliminating federal supervision of the state election.”Footnote 142 Another mechanism was excluding Black voters from primary elections, pioneered in 1878, shortly after Reese. Footnote 143 By shifting the contest to primaries, Democrats skirted the limited federal enforcement permitted in general congressional elections. Some states simply held local elections on different days from federal races. Table 2 provides evidence of the effectiveness of this strategy. Although only Kentucky held off-month state elections before Reese, several states like Alabama, Arkansas, and Georgia moved to holding their states elections in a different month after Reese. As would be expected, Republican vote-share decreased more markedly in states that held off-month elections.Footnote 144

Table 2. Median GOP-Vote Share in Southern Elections (1870-1890)

Source: ICPSR, Candidate Totals.

Note: Where available, non-November is categorized as off-month. States with off-month election include: KY, AL, AR, and GA. Only KY held off-month elections prior. AL, AR, and GA instituted off-month elections later.

Harris and the Civil Rights Cases

Even if prosecutions in 1881 can be viewed as outlier evidence that Cruikshank did not permanently destroy federal enforcement capacity, the Court’s decision in 1883 to further invalidate portions of the enforcement acts ensured that only a handful of prosecutions continued. Two district judges, in northern Mississippi and eastern Texas, were jointly responsible for over 75% of convictions in the South in 1881.Footnote 145 After Harris, no judge upheld more than a few one-off convictions, including all district judges who had permitted large trials prior. In Harris, the Supreme Court invalidated Section 2 of the KKK Act that criminalized “depriving any person or any class of persons of the equal protection of the laws … [or] preventing or hindering the constituted authorities of any State from giving or securing to all persons within such State the equal protection of the laws.”Footnote 146 Tennessee Sheriff R.G. Harris and nineteen others, including deputy sheriffs, were charged with assaulting four men in state custody and killing one.Footnote 147 Citing Reese and Bradley’s opinion in Cruikshank, Justice William Woods invalidated Section 2 because “it applies no matter how well the state may have performed its duty.”Footnote 148 The Court continued expanding its novel nonseverability approach from Reese and invalidated a section being applied appropriately—government officials were in the lynch mob and failed to prevent a murder of someone in state custody.

Pamela Brandwein has suggested that Harris is an anomaly because the Court might have not known about the state officials in the mob.Footnote 149 Even if the participation of two state actors was unknown, the lack of protection provided in state custody should itself satisfy state action. Brandwein also suggests that a race-based theory of state neglect was unavailable because of Cruikshank. Her historical work has suggested the victims in Harris might have been white rather than Black as assumed by both the justices and contemporaneous newspapers.Footnote 150 Given that contemporaries assumed the victims were African American, it is unclear why a race-based theory of state neglect was unavailable to uphold the prosecutions. Furthermore, even if a race-based state neglect theory was unavailing, legal constraints dictated that the Court decide the case on those narrower grounds (holding Section 2 did not apply because there was no state action). Instead, the justices invalidated another pillar of enforcement, allowing more murderers to walk free. Constitutional avoidance, although not yet so named, was a clearly established legal principle. At least since the Marshall Court, justices routinely found ways to avoid major constitutional decisions as a way to restrain their political influence.Footnote 151 Thomas Cooley’s influential legal treatise on judicial review articulated this standard just years prior:Footnote 152

[Y]et if the record also presents some other and clear ground upon which the court may rest its judgement, and thereby render the constitutional question immaterial to the case, the court will take that course.

As with Reese, the Court circumvented conventional restraints to invalidate enforcement efforts. The same term, Justice Bradley would announce his most infamous opinion in the Civil Rights Cases. The Court struck down the first two sections (public accommodations provisions) of the Civil Rights Act of 1875. In doing so, Bradley held the Fourteenth Amendment allowed Congress only “to adopt appropriate legislation for correcting the effects of such prohibited State laws and State acts.”Footnote 153 This cramped view was antithetical to his closest political benefactor: Senator Frelinghuysen.

After drafting his circuit opinion in Cruikshank but before the matter came before the full Court, Bradley sent his draft to Frelinghuysen. Frelinghuysen, Bradley’s law school classmate, was more than anyone responsible for Bradley’s appointment.Footnote 154 Even though Frelinghuysen was a radical, he was Bradley’s trusted confidant. If any political actor was able to convince Bradley to toe the party line in upholding the acts, it was Frelinghuysen. Frelinghuysen responded to Bradley’s Cruikshank opinion in early July, 1874, arguing Section 6 of the First Enforcement Act was compatible with the 14th Amendment.Footnote 155 Bradley disagreed:Footnote 156

[H]as it not always been the fact that the constitution of the United States conferred citizenship of the United States upon such as were citizens? And if so, has not congress always had the same power to protect its own citizens which it now has? And has any such power as that now claimed ever been operative… . I am hardly prepared to regard the express power of legislation given in the fourteenth amendment as such an answer.

In personal correspondence with his political benefactor, Bradley refused to allow the 14th Amendment to update antebellum constitutionalism. He may have been guided in this opinion by his fear of Black equality. In his personal writings on the Civil Rights Act, Bradley wondered “does freedom of the blacks require the slavery of the whites?”Footnote 157

Bradley rebuked Frelinghuysen again in the Civil Rights Cases. Senator Frelinghuysen reported the Civil Rights Act out from the Committee on the Judiciary.Footnote 158 While Frelinghuysen was leading the effort for enactment, Bradley clipped negative newspaper reports of the bill from southern editors to send Frelinghuysen.Footnote 159 It is not clear if this was an effort to dissuade Frelinghuysen from supporting the measure. President Grant, who appointed Bradley to the Court, signed the Civil Rights Act in the final days of his presidency. Both the senator and president who put Bradley on the Court had been closely associated with the bill. Furthermore, the justice penned a notorious sentence summarizing his rejection of the Republican Reconstruction project:Footnote 160

[T]here must be some stage in the progress of his [Black men] elevation when he takes the rank of a mere citizen and ceases to be the special favorite of the laws.

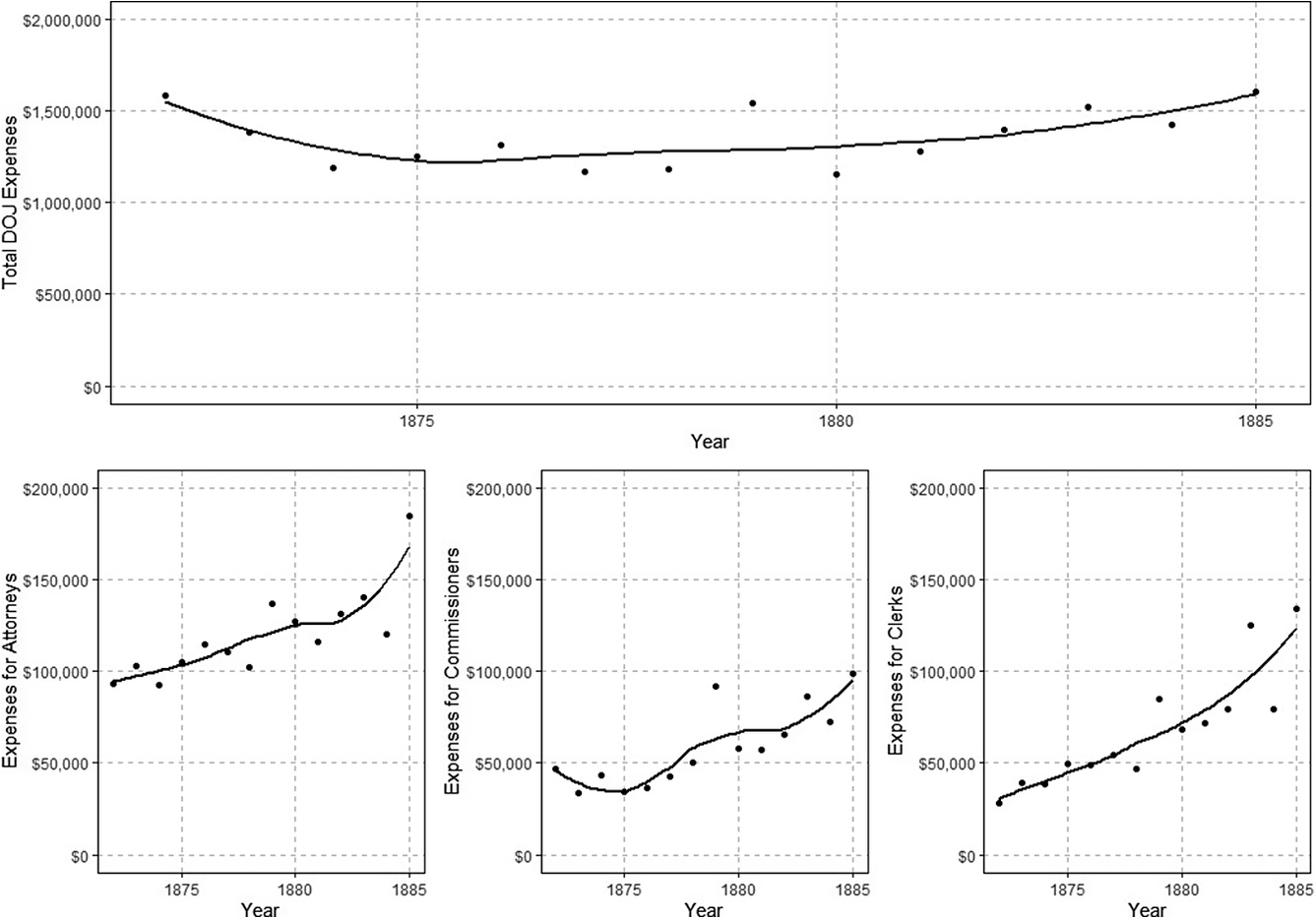

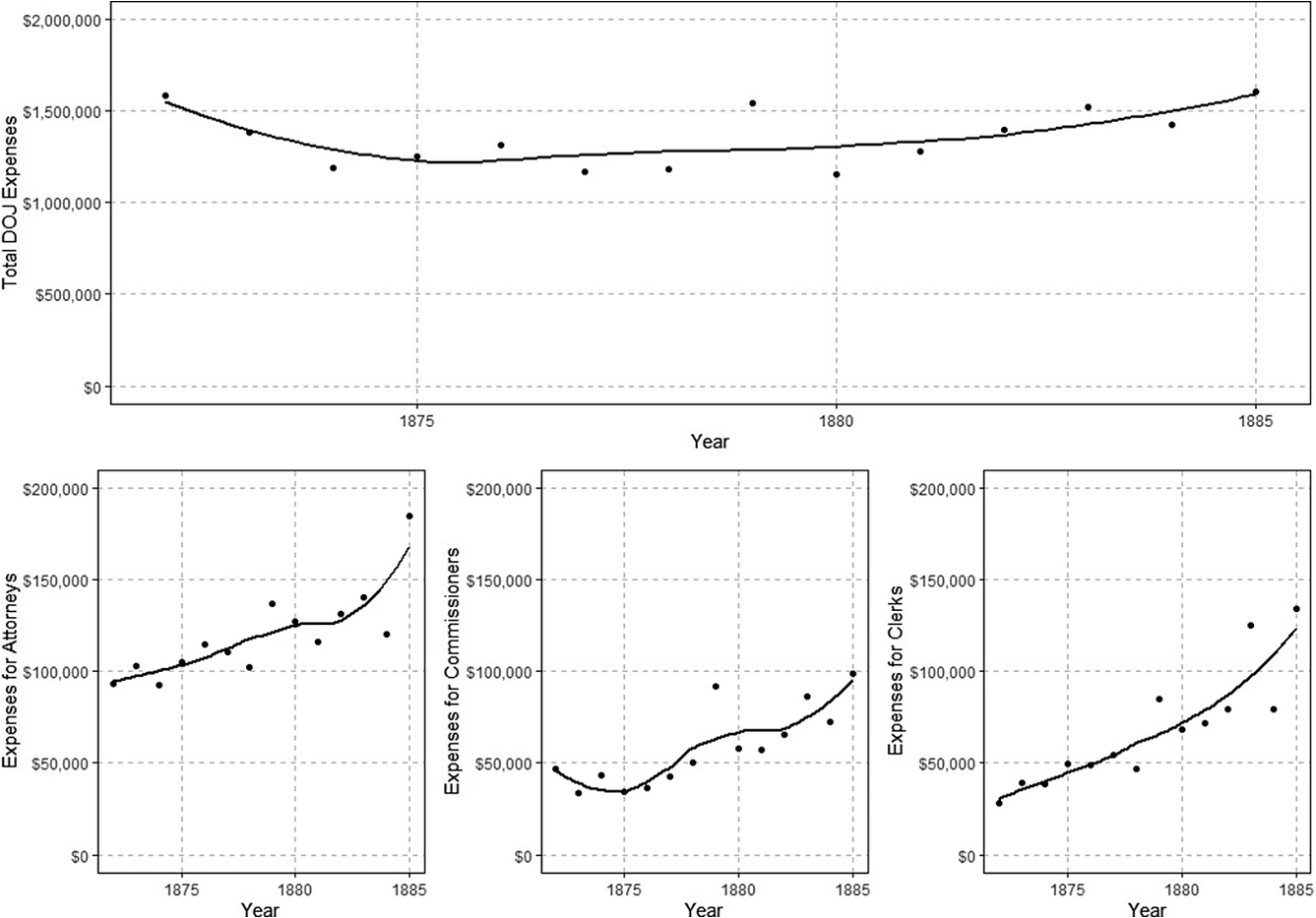

As can be seen in Figure 1, prosecutions under the enforcement acts came to a standstill. Over the decade following Harris, less than forty successful prosecutions were had in the entire South, with most years yielding no convictions.Footnote 161 The stalling of federal prosecutions occurred at a time when material investment in the enforcement apparatus was expanding (Figure 4). Even as Republicans turned their attention toward building constituencies in the West,Footnote 162 the party continued to support enforcement in southern states. Part of the explanation for the enduring Republican commitment to racial equality in the South came from their theory of political change. Despite southern intransigence, many Republicans shared the belief that racial animus flowed from the southern planter oligarchy “perverting public opinion.”Footnote 163 If Reconstruction could “neuter the antebellum slaveholding elite,” ordinary southern whites would “discard their antebellum racial prejudices.”Footnote 164 Before the South became ‘solid,’ Republicans continued to believe their party-building efforts could unmoor racial antipathy and permit Republican state governments a competitive foothold.

Figure 4. DOJ Total, Attorney, Commissioner, & Clerk Expenses. US South (1872-1885).

Source: Annual Report[s].

Note: Additional DOJ expenses available in Appendix D.

Material Commitment to Reconstruction

The analyses have demonstrated 1874 and 1883 as pivotal years for the decline in enforcement act prosecutions. Furthermore, in 1876 a large separation between Republican fortunes at state and federal elections emerged. These years conform to crucial decisions by the justices in Cruikshank, Harris and the Civil Rights Cases, and Reese, respectively. However, it is possible the cases aligned with other events that were actually determinative. To confidently say the Court facilitated these outcomes, one must rule out alternative hypotheses. This article considers the three most persuasive alternative explanations and provides evidence incompatible with each: (1) The Panic of 1873 drained resources, (2) Republicans lost party unity, and (3) Republican presidents abandoned enforcement. While the literature considering the end of Reconstruction is vast, this article is the first to look at material outlays supporting enforcement.Footnote 165 Based on continued appropriations, Reconstruction’s end is hard to reconcile with any explanation besides the changed jurisprudential landscape.

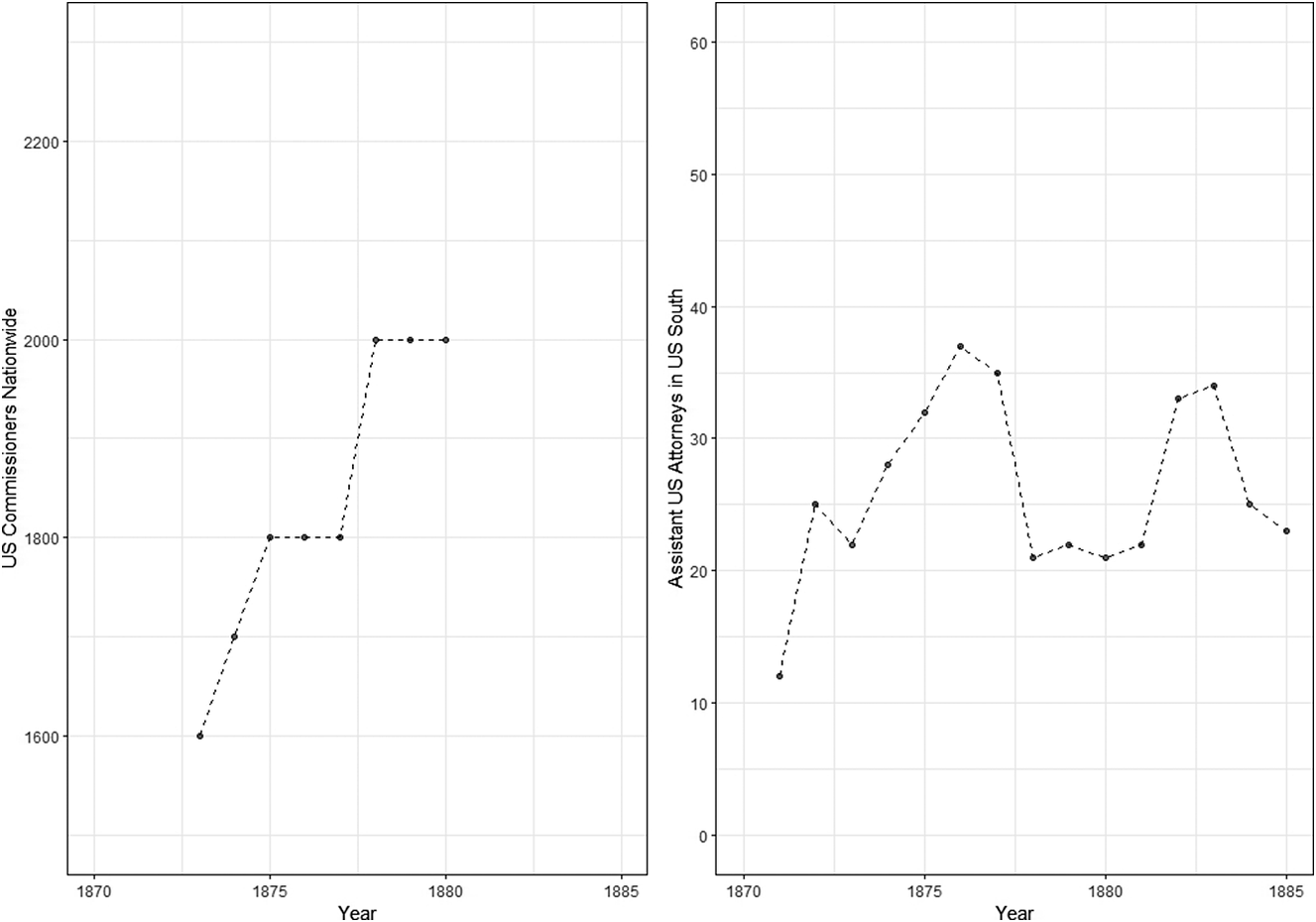

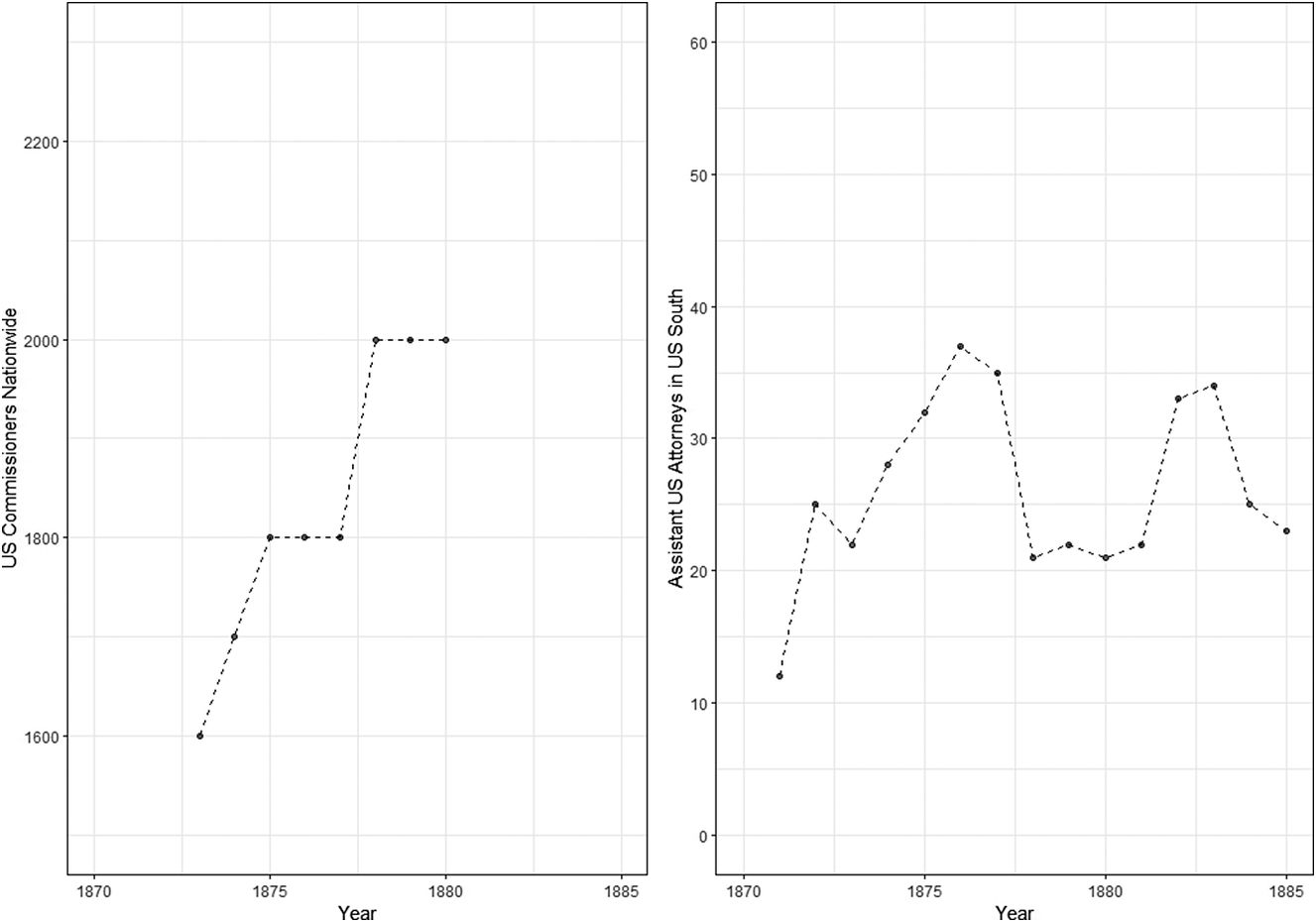

The Panic of 1873 is often invoked for the precipitous decline in convictions.Footnote 166 The theory holds that due to a long enduring recession, Republicans lacked resources to continue enforcement and diverted energy elsewhere. However, annual expenses for enforcement held constant following the Panic of 1873 (Figure 4). Using overlooked data in DOJ Archives, this article has compiled the annual expenses on enforcement for key categories, often spread over multiple disparate appropriations measures. When aggregated, and owing to a fee system that enabled local officials a degree of autonomy, it becomes evident the enforcement apparatus expanded through the mid-1880s. This is also apparent in the number of assistant attorneys and commissioners provided. While the data on commissioners relies on sporadic reporting by the attorney general, there is a clear upward trend through the 1870s. Attorneys, meanwhile, had yearly fluctuations but saw no prolonged retrenchment over this time (Figure 5). If the drop in prosecutions was a response to the Panic of 1873, we would expect the mechanism (diverted resources) to drop correspondingly. Instead, the apparatus of enforcement actually expanded over this period.

Figure 5. Southern AUSAs and Total Commissioner Count (1870–1885).

Source: Annual Report[s] & DOJ Register (1871).

Note: National commissioner data. Annual Reports have missingness. Data linearly interpolated. Noninterpolated graphs in Appendix C. AUSAs include “regular” and “special” assistants with enforcement roles.

Another theory centers Congress in abandoning Reconstruction.Footnote 167 This account holds congressional Republicans lost the will to sustain enforcement. It is bolstered by Democrats winning back the House in 1875. Although the Court struck down key provisions, a motivated Congress could have passed new laws to enforce Black rights while hewing the Court’s constitutional line. The lack of response was indicative of congressional apathy, ultimately ending Reconstruction. Missing, however, is the fact that Congress did reenact portions of the enforcement acts invalidated or made impracticable in Reese and Cruikshank. Footnote 168 Furthermore, at Grant’s urging, Congress took up another enforcement act (H.R. 4745) in the outgoing days of the 43rd Congress to expand the power of election supervisors and the president, and reenact much of the enforcement acts, after they were upended by circuit decisions in Reese and Cruikshank. Racing against the clock, the bill passed the House 135 to 114, after Benjamin Butler proposed limiting the provision extending the president’s ability to suspend habeas corpus, the primary sticking point for reluctant Republicans. The Senate never voted on it, lacking time in the legislative session.Footnote 169 Near passage of another enforcement act, supported by Grant and a House majority, is suggestive of the ongoing Republican commitment and is evidence the Court was not implementing the regime’s agenda. Furthermore, an outgoing Republican Congress enacted their boldest defense yet of Black rights—the 1875 Civil Rights Act.Footnote 170

A final theory holds that Grant or Hayes abandoned enforcement.Footnote 171 Two pieces of evidence are usually adduced to suggest Grant “abandoned civil rights enforcement.”Footnote 172 First, scholars point to directions by Attorney General Williams in spring and summer of 1873, advising only necessary prosecutions. In one letter Williams wrote, “these prosecutions… are carried on to … protect the rights of citizens; but when those ends are accomplished, it is not desirable to multiply suits of this description as they tend to keep up an excited state of feelings.”Footnote 173 This came when federal prosecutors were successfully winning cases against vigilante violence and Grant’s DOJ had successfully constrained the Klan. Even so, prosecutions after Williams’ letter continued as discretion was vested in federal officers to decide which cases were required to maintain peace. Indeed, 1873 saw both the highest level of cases pending (1,960) and successful prosecutions (469) during Reconstruction.Footnote 174 Such high prosecution and conviction rates would be impossible if the administration abandoned enforcement. Additionally, the federal troop presence in the South remained relatively constant through the years of decreased convictions.Footnote 175 Second, scholars point to Grant not sending troops to Mississippi in late summer of 1875 to quell violence.Footnote 176 Grant, however, had his message on the preconditions of deploying troops altered by Attorney General Pierrepont, a conservative Democrat Grant selected in a bid to forestall inquiries from House Democrats into the DOJ.Footnote 177 Pierrepont “struck out a line saying that Grant had agreed to an intervention proclamation.”Footnote 178 Grant remained committed to civil and political rights enforcement through the end of his term, as evident by his recommendation of another enforcement act, endorsement of the Civil Rights Act, and sending of more than a thousand troops to South Carolina to suppress violence in late 1876.Footnote 179 The president always expressly believed federal courts could apply the enforcement acts at state elections and against the states: “That the courts of the United States have the right to interfere in various ways with State elections so as to maintain political equality and rights therein, irrespective of race or color, is comparatively a new, and to some seems to be a startling idea, but it results as clearly from the fifteenth amendment to the Constitution and the acts that have been passed to enforce that amendment.”Footnote 180 This is plainly at odds with the Court’s later ruling in Reese and against the spirit of Cruikshank, suggesting the Court was deviating considerably.

The thesis of Hayes’ abandonment is beset by timing. The machinery of enforcement foundered in 1874. Hayes’ withdrawal of federal troops from Louisiana and South Carolina statehouses played a symbolic role, but enforcement was already hobbled. Furthermore, Attorney General Devens used his remaining authority under the enforcement acts, instructing officers, “prosecute all persons charged according with the forms of law with criminal violations.”Footnote 181 Hayes, originally more concerned with reconciliation than enforcement, changed his mind early in his tenure. Witnessing southern violence during the 1878 midterm, Hayes felt southerners had betrayed his policy of home rule in exchange for peace. He was “reluctantly forced to admit that the experiment was a failure.”Footnote 182 Hayes vetoed seven Democratic efforts at repealing enforcement laws.Footnote 183 In response, he recommitted the administration to robust enforcement, instructing his cabinet to take “the most determined and vigorous action.”Footnote 184 However, this effort amounted to little due to overwhelming jurisprudential obstacles.

The Entrepreneurship of Justice Bradley

The question remains, why was the Court, and Justice Bradley in particular, out of step with the Republican regime responsible for judicial appointments? As will be shown, Bradley was largely ambivalent to the conditions of freedpeople and very concerned with their productive labor. Reconstruction was a process of negotiating the end of slavery and the ideal of a free-labor society. As historian Amy Dru Stanley has shown, Republican congressmen believed “the labor question [was] the logical sequence of the slavery question.”Footnote 185 Bradley was deeply concerned with the latter. Careful not to upset what he regarded as the “normal condition” of southern labor, Bradley was anxious to ensure Black laborers returned to agricultural production.Footnote 186 Bradley, who self-described as “a conservative of the conservatives,” did not align himself with emancipation or resistance to slavery, unlike other antebellum Republican lawyers.Footnote 187 On the contrary, Bradley defended continued enslavement in New Jersey, and the prerogative of southern states to continue slavery.Footnote 188 Even after opposition to Dred Scott became the sine qua non of his party, Bradley wrote, “justice also requires that the citizens of the South, as well as the North, should have a fair opportunity to emigrate, with their property, to the territories which have been purchased with the common treasure.”Footnote 189

In 1862, Bradley lost a race for Congress, campaigning on saving the union with “all things remain[ing] as they were.”Footnote 190 In October of 1866, after Congress passed the civil rights bill and the 13th and 14th Amendments, Bradley was solicited and declined to argue a case forwarding the view Black Americans were entitled to privileges of citizenship including enfranchisement.Footnote 191 Bradley reasoned it was “too late now to question that,” because suffrage denials had previously been compatible with republican government.Footnote 192 This was a remarkably similar argument to the one he made to Frelinghuysen, demonstrating a deep resistance to change following the Civil War.Footnote 193 While the Republican Party was shifting towards unprecedented federal intervention in state affairs, Bradley fretted about plantations being “broken up.” He came to believe the Freedmen’s Bureau was “an engine of mischief,” which taught Black southerners to be “utterly uncapacitated from labor.” Bradley complained of Black freedpeople, “their vagrancy [is] only limited by their means of locomotion. How shall the planter keep them on the plantation? ” Looking around at the beginnings of Reconstruction, he wondered “whether things will right themselves.”Footnote 194 Bradley similarly expressed disapprobation of Reconstruction governments writing, “some of the Southern States have, within the past few years, been so deplorably oppressed and impoverished.”Footnote 195 These writings express Bradley’s “dual objectives of solving the planters’ problem of labor control and preserving the national Republican Party’s opportunity to reap black votes.”Footnote 196 In short, Bradley was indifferent to slavery and Black civil and political rights and all the while concerned about the productivity of the plantation economy.Footnote 197

In personal writings, Bradley explained his view of civil, political, and social rights. Bradley asked what the “equality alluded to in the Declaration” meant. He first dispatched with the idea it meant economic equality stating, “there are many species of luxury … which the great mass of mankind are incapable of enjoying.” He further concluded that social equality “would be to introduce another kind of slavery.” He continued, “surely a white per- son (∧)lady (sic) cannot be enforced by Congressional enactments to admit colored persons to her ball.” In an argument presaging separate but equal, Bradley wrote, “what are essential to the enjoyment of citizenship? Is the white man’s theater such an essential, if the colored person is free to have his own theater?” Bradley concluded equality meant, “each man [has] an equal voice in the civil government of this country.”Footnote 198

Bradley’s winnowing of civil rights, repudiation of social rights, and acceptance of limited political rights, is thoroughly explicable as his own legal-political preference. In striking down protections for civil and social rights, while maintaining some room for federal voting rights enforcement, Bradley bucked the senator, president, and party who secured his appointment. In doing so, Bradley changed the politics around him, arrogated power for the Court, and enacted his own vision.

Conclusion

Regime theories have offered sophisticated analyses of the Supreme Court’s political-legal actions and successfully rebutted the strictly legal model. However, they risk going too far by asserting that when the Court coordinates with other branches, it gains something approaching democratic legitimacy. This article uses the example of Joseph Bradley during Reconstruction to argue against both the disembedded and entirely politically constructed Court. By in large, the Supreme Court acts within legal-political constraints. However, these constraints do not always bind. When motivated, politically savvy and externally supported justices can assert novel theories of law. Shrewd justices use the ambiguity surrounding high-profile political cases to accrete power and intervene in political streams.

To demonstrate Bradley’s divergence with the Republican Party, this article has disagreed with a common conclusion of recent Reconstruction scholarship that the Court followed the party’s retreat. To show the Court actually led abandonment, this article has pushed scholarship forward on three fronts. First, it prioritizes the outcomes of state parties. Reese advanced the redemption of southern state governments that resulted in generational control for Democrats. Second, by using overlooked data in DOJ archives, this article unsettles narratives of political abandonment. Long after the Court retreated from Reconstruction, Congress was still providing the executive branch with resources to prosecute violations. Presidents from Grant through Arthur continued to bring prosecutions under the enforcement acts.Footnote 199 Despite these investments and continued commitment, the force of prosecutions never recovered, as evidenced by the plummeting conviction rates. Last, it argues the Court’s path was more determined by the long-standing vision of a crucial justice than the political agenda of the party that confirmed the Court’s majority. Assessing when the preferences of justices run counter to the political regime is an analytical strategy applicable to other moments in American political development. The Court has accrued power against the wishes of the regime in other contexts and at the expense of other institutions throughout history including juries, state courts, and the administrative state.Footnote 200 Scholars of APD should take stock of these power transfers and might usefully employ the methods of this article to do so. As a recent critique of the regime literature holds, “history has pushed past [a] Dahlian view … such that it now offers an unrealistic conception of the Court … and the dominant alliances actually driving our politics.”Footnote 201 Political science will need to develop new theories and update the regime literature to better explain moments of judicial aggrandizement, past and present. This article has attempted to contribute one small step in that project.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0898030625100511.