1. Introduction

Improving knowledge can be a valuable strategy for improving people’s financial outcomes. Prior work has identified two key knowledge areas: Personal finance and math (Hastings et al. Reference Hastings, Madrian and Skimmyhorn2013; Lusardi and Mitchell Reference Lusardi and Mitchell2023). Though higher levels of financial knowledge and math knowledge have each been independently associated with better financial behaviors, their combined role in improving financial outcomes remains unclear.

In this brief, we examined preliminary empirical data related to the combined role of financial and math knowledge. Using survey data from a nationally representative, probability-based panel which assesses respondents’ financial knowledge, math knowledge, and financial behaviors, we examined the extent to which financial and math knowledge, both separately and combined, are associated with beneficial financial behaviors.

We found that higher levels of financial and math knowledge are associated with better financial behaviors. For some behaviors, notably owning taxable investments outside of retirement accounts, the benefits associated with possessing both financial and math knowledge are greater than those associated with possessing either type of knowledge alone. This suggests that higher levels of both financial and math knowledge may be useful for sound financial decision-making, but more research is needed to study these effects.

1.2. Background

Many US adults experience financial difficulties, such as a lack of adequate emergency savings and a failure to save for retirement. Further, a large number do not engage in strategies that can provide some relief, such as implementing a plan for saving or avoiding costly financial products and fees (Lusardi and Mitchell Reference Lusardi and Mitchell2023). While financial difficulties can often stem from multiple sources – such as limited access to capital and financial services, sub-optimal decision-making may also be responsible (Angrisani et al. Reference Angrisani, Burke, Lusardi and Mottola2023).

Improving financial knowledge is often used as a vehicle for bolstering financial capability. Indeed, many studies show that financial knowledge predicts better financial outcomes (see Angrisani et al. Reference Angrisani, Burke, Lusardi and Mottola2023 and the reviews in Lusardi and Messy (Reference Lusardi and Messy2023) and Lusardi and Mitchell (Reference Lusardi and Mitchell2023)). Math is another knowledge area connected to better financial capability, with a well-documented relationship between numeracy and improved financial outcomes (Hastings et al. Reference Hastings, Madrian and Skimmyhorn2013; Lusardi and Wallace Reference Lusardi and Wallace2013), and evidence that individuals with greater math abilities tend to have higher levels of financial literacy (Moreno-Herrero et al. Reference Moreno-Herrero, Salas-Velasco and Sánchez-Campillo2018).

However, few studies have investigated the combined effects of financial and math knowledge on financial outcomes. Further, financial education skeptics have argued that bolstering math knowledge is a superior alternative (Ogden, Reference Ogden2019), while financial education proponents often focus on improving financial knowledge. One possibility though is that math and financial knowledge are two components of an effective strategy for improving financial outcomes rather than mutually exclusive alternatives.

A small number of studies have examined the joint roles of math and financial literacy on outcomes, with mixed results (Cole et al. Reference Cole, Paulson and Shastry2016; Marley-Payne et al. Reference Marley-Payne, Dituri and Davidson2022). The present brief conducts an exploratory analysis of the combined roles of financial and math knowledge on financial outcomes using new data.

1.3. Data

This study used survey data collected in April and May 2021 from the National Opinion Research Center’s (NORC) AmeriSpeak® Panel, a probability-based panel designed to be representative of the US household population. A total of 1,680 US adults aged 18 years and older participated in the study. For the purposes of our study, we restricted the dataset to those aged 22 to 75 years (N = 1,588) to include age groups that are typically in or recently retired from the workforce.

The study was fielded in English only and was administered online. Respondents were considered eligible for the study if they were either the primary decision-maker or shared in the decision-making related to finances in the household. The sample included oversamples of Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino respondents. AmeriSpeak participants self-identified their age, sex, education, and race/ethnicity.Footnote 1 Statistical weights were used to make the sample representative of the US adult population (18+) in terms of age, sex, education, race/Hispanic ethnicity, and Census Division. Weights were used in all descriptive statistics and regression analyses.

1.4. Variables

Financial Knowledge. Financial knowledge was assessed via the Big Three, a widely used financial literacy scale consisting of three questions that measure adults’ knowledge on fundamental financial topics, including interest rates, inflation, and risk diversification (Lusardi and Mitchell Reference Lusardi, Mitchell, Lusardi and Mitchell2011). The median score was two out of three correct (mean = 2.16; SD = 0.97). Respondents were classified as having a “high” score if they answered at least two of three questions correctly and a “low” score if they answered fewer than two questions correctly.

Math Knowledge. Math knowledge was assessed via three questions gauging respondents’ ability to calculate probabilities, percentages, and inputs into an algebraic equation. The median score was two out of three correct (mean = 1.84; SD = 1.03). As with financial knowledge, we classified a “high” score as correctly answering at least two of three questions correctly and a “low” score as answering fewer than two questions correctly (the exact wording for these questions is provided in Appendix A).

To perform the empirical analyses, we divided participants into four categories: (1) those with low math and financial knowledge (Low Scorers), (2) those with low math knowledge but high financial knowledge (Finance Savvy), (3) those with high math knowledge but low financial knowledge (Math Savvy), and (4) those with both high math and financial knowledge (High Scorers).

If financial and math knowledge are competing alternatives, we would expect to see similar financial behaviors associated with either Finance Savvy or Math Savvy respondents as for High Scorers. If, instead, the two forms of knowledge are both useful, we might see different and better behaviors for High Scorers.

Financial Outcomes. We identified four financial behaviors that knowledge and education may be well suited to influence, such as ownership of various types of assets that serve as a proxy for financial decision-making (Marley-Payne et al. Reference Marley-Payne, Dituri and Davidson2022). Given that most participants are in wealth accumulation years, we classified these behaviors as “positive.” These behaviors are generally in line with tasks and behaviors identified by Grable et al. (Reference Grable, Kruger and Fallaw2017) as those that could help wealth accumulation. We also identified three negative behaviors that could harm wealth accumulation.

The positive behaviors included the following: (1) having a savings account, (2) having a plan for saving, (3) having a retirement account, and (4) owning taxable investments outside of retirement accounts. We consider each of these behaviors in the empirical analyses. The negative behaviors included the following: (1) having ever used a check cashing service, (2) having ever taken out a payday loan, and (3) being unbanked – that is, no one in the household possessing a bank or financial account.Footnote 2 Due to the low prevalence rates of the individual negative behaviors assessed, we could not run separate regressions for each negative behavior. Instead, we created a composite binary variable where “1” indicated that the respondent engaged in at least one of the three negative behaviors studied and “0” indicated otherwise.

Control Variables. The following demographic controls are included in each regression: gender, race/ethnicity, age, income, education level, marital status, and geographic location. These controls resemble those used by Marley-Payne et al. (Reference Marley-Payne, Dituri and Davidson2022) and serve as proxies for preferences and economic circumstances, which are expected to affect behavior. In addition, because this study analyzed data collected for a separate research project that examined the role of “don’t know” responses in knowledge assessments, half of the participants had been randomly assigned to be provided a “don’t know” response option for financial and math knowledge questions (DK), while the other half were not given this response option (NDK). To account for this difference, all models include a control identifying whether a respondent was placed into the DK or NDK group.

2. Empirical findings

Five Linear Probability Model regression analyses (four for the positive behaviors and one for the composite negative behavior) examined the independent and the joint roles of financial and math knowledge on financial outcomes. Knowledge group was included as an independent variable with four classifications: Low Scorer, Finance Savvy, Math Savvy, and High Scorer. Given our primary aim to better understand the combined effects of financial and math knowledge on financial behaviors, we chose High Scorer as the reference group. We also performed a least squares linear regression, which used the total number of positive behaviors respondents engaged in (out of four) as the outcome variable. As robustness check, we also ran separate regressions using the total number of correct responses to the math knowledge questions and the total number of correct responses to the financial knowledge questions as independent variables to compare to the results obtained when using the four financial knowledge/math knowledge categories we created.

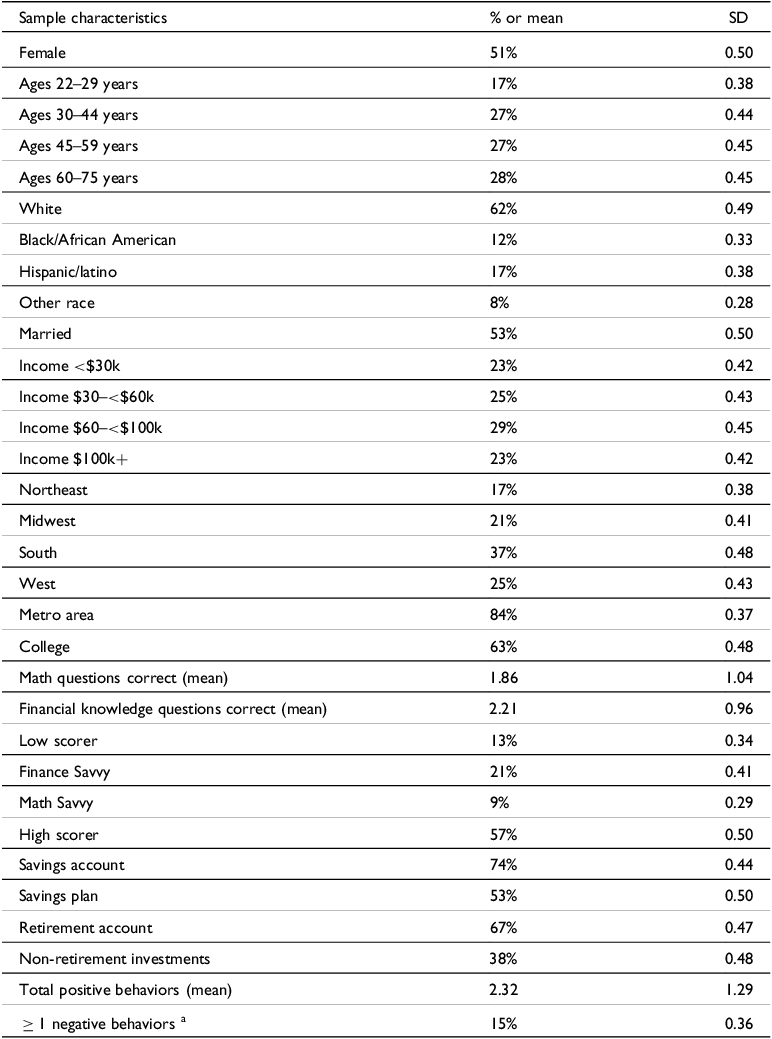

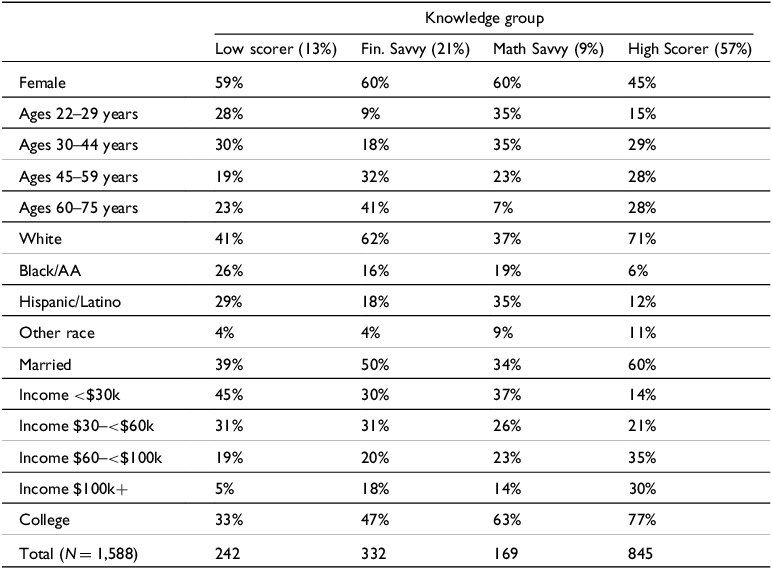

Table 1 presents the weighted descriptive statistics for the full sample, while Table 2 displays these statistics across each knowledge group. These figures broadly resemble the demographic characteristics of the US population. Over half of respondents were categorized as High Scorers, with high levels of both math and financial knowledge, while 10–20% were classified into each of the other three knowledge categories.Footnote 3 Prevalence rates for the behaviors studied varied substantially. Over 70% of respondents reported possessing a savings account, while only about 40% reported owning a taxable non-retirement investment account.

Table 1. Overall sample characteristics

Notes. N = 1,588. All statistics are weighted to be representative of the US population.

a Sample size was reduced to 1,472 observations due to missing data.

Table 2. Demographics by financial knowledge/math knowledge group

2.1. Regression analyses

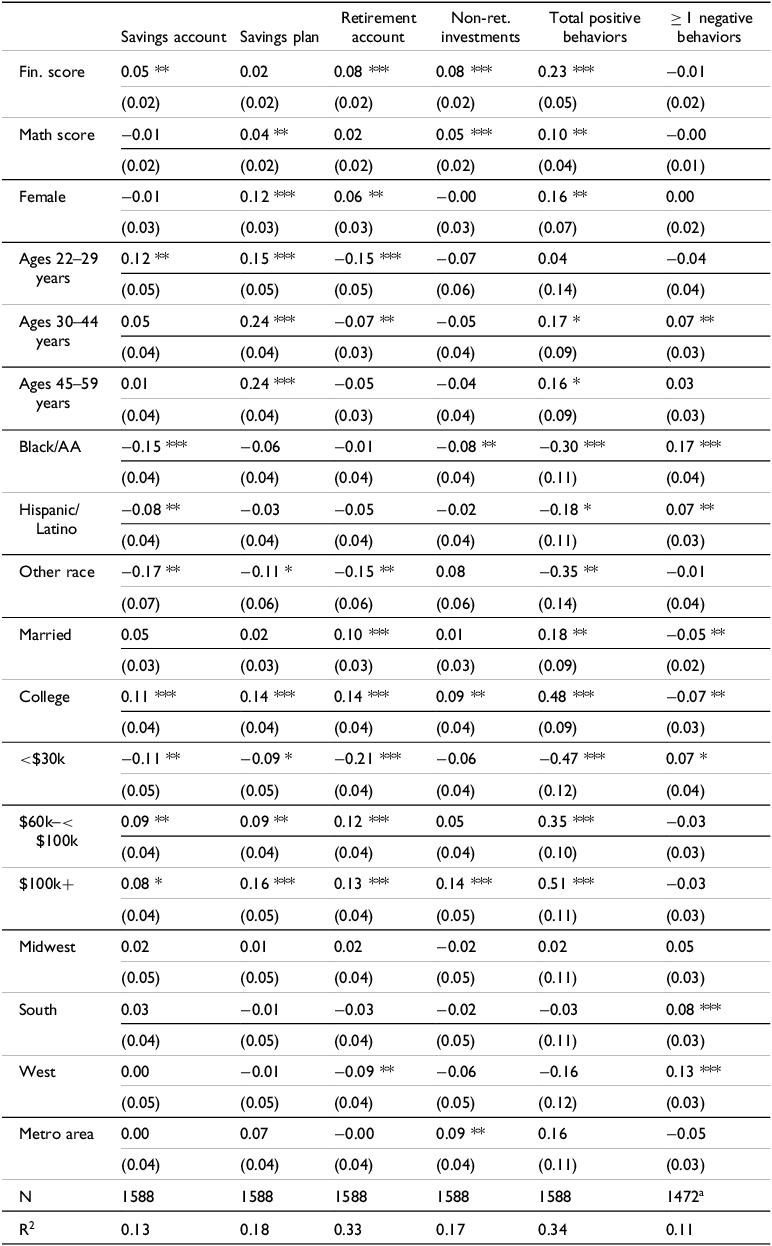

Table 3 displays the regression results using the total number of correct financial knowledge and math knowledge questions as independent variables. After accounting for relevant demographic characteristics, higher financial knowledge scores were associated with a greater likelihood of having a saving account, owning a retirement account, and owning non-retirement investments. In addition, higher financial knowledge scores were also associated with engaging in a greater number of the studied positive behaviors. Higher math knowledge scores, in turn, were associated with a greater likelihood of having a plan for saving and owning non-retirement investments. Further, higher math knowledge scores were also associated with engaging in a greater number of positive behaviors. However, neither financial nor math knowledge scores were associated with engaging in at least one of the negative financial behaviors studied.

Table 3. Regression results for financial and math knowledge scores on financial behaviors

Note. Ref. groups: gender, male; age, 60–75 years; race/ethnicity, White; income, $30k–$60k; region, Northeast.

While not shown, all regressions control for experimental condition (DK vs. NDK) where respondents were or were not provided a “don’t know” response option.

a Sample size was reduced to 1,472 observations due to missing data.

*** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.1

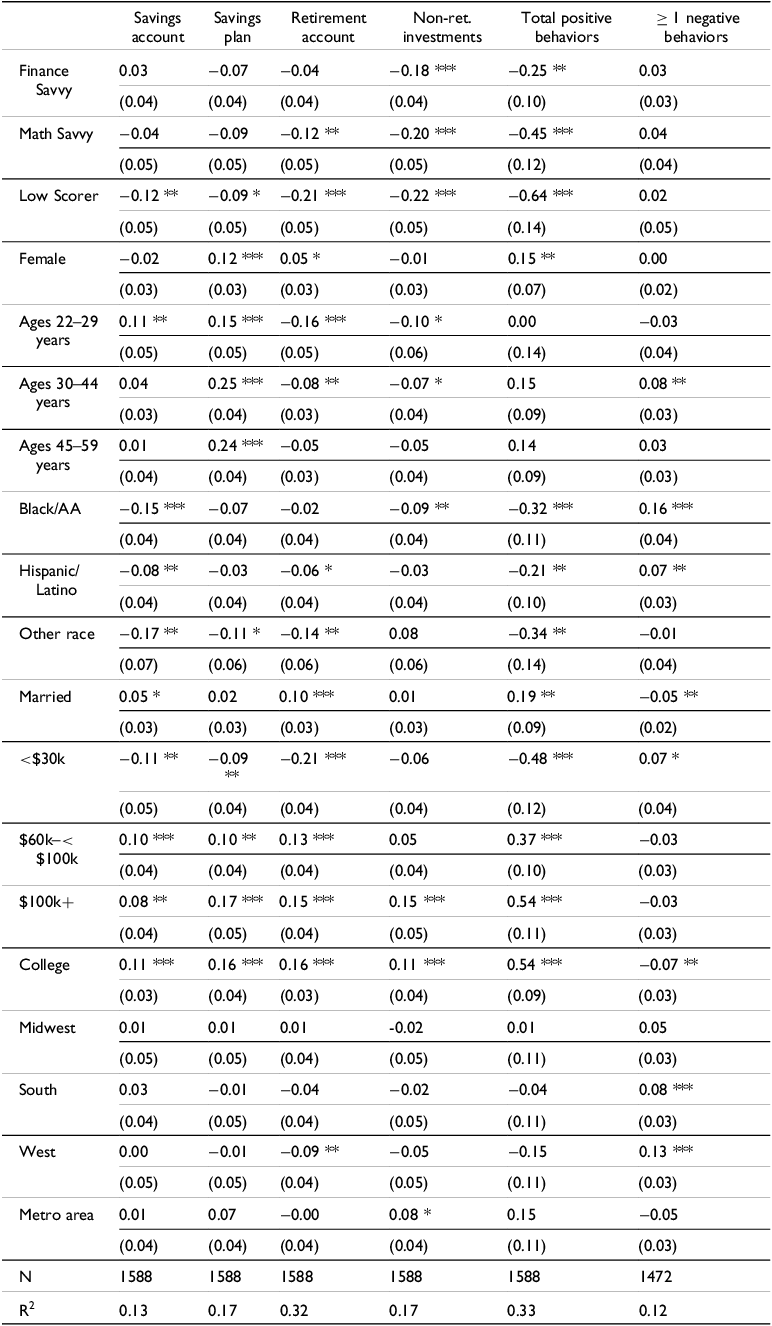

Table 4 shows the results of the regression analyses that used the financial knowledge and math knowledge categorical variables. These results align with and complement the regressions that used the financial knowledge score and math knowledge score. After accounting for relevant demographic characteristics, our estimates suggest that relative to High Scorers, Low Scorers were significantly less likely to report three of the four positive financial behaviors examined (12 pp less likely to report a savings account, 21 pp less likely to have a retirement account, and 22 pp less likely to have non-retirement investments). Overall, Low Scorers engaged in 0.64 fewer positive behaviors than High Scorers.

Table 4. Regression results for knowledge groups on financial behaviorsa

Note. Ref. groups: gender, male; age, 60–75 years; race/ethnicity, White; income, $30k–$60k; region, Northeast. While not shown, all regressions control for experimental condition (DK vs. NDK) where respondents were or were not provided a “don’t know” response option.

a Sample size was reduced to 1,472 observations due to missing data.

*** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.1.

Differences between High Scorers and those with high scores in only financial (Finance Savvy) or math knowledge (Math Savvy) are less consistent. Compared to High Scorers, Finance Savvy respondents were 18 pp less likely to own non-retirement investments and reported engaging in 0.25 fewer positive behaviors than High Scorers. Math Savvy respondents, in turn, were 12 pp less likely to own a retirement account, 20 pp less likely to own non-retirement investments, and reported engaging in 0.45 fewer positive behaviors than High Scorers.

Classification in any of the knowledge groups was unrelated to the likelihood of engaging in one or more of the negative behaviors studied.

3. Discussion

This brief examined the relationship between financial and math knowledge and a range of financial behaviors. Our results suggest that those reporting high levels of both types of knowledge tended to report a greater likelihood of engaging in at least one beneficial financial behavior and an overall greater quantity of such behaviors than those with high financial or math knowledge alone. However, high levels of both forms of knowledge were not associated with the probability of engaging in potentially harmful financial behaviors.

Given the cross-sectional nature of the data, we cannot draw causal implications about the influence of financial and math knowledge on downstream financial behaviors. Though higher knowledge levels may lead to beneficial behaviors through improved decision-making, it is also possible that engaging in certain financial behaviors can influence knowledge levels. In addition, while we control for income, education, and other demographic variables, unobserved variables such as wealth and risk preferences (which are unavailable in the current dataset) may have also played a role.

Future studies could leverage an instrumental variables (IV) approach to alleviate endogeneity concerns and allow for causal conclusions. Past research provides reassurance on this front, as IV approaches have not only confirmed causal effects from financial knowledge to behavior but suggested that OLS approaches may actually underestimate the existing link between the two (Lusardi and Mitchell Reference Lusardi and Mitchell2014).

While more remains to be learned about the interaction between financial and math knowledge in relation to financial behaviors, these findings provide initial evidence that both financial and math knowledge may work as complementary components in preparing students for financial success. We hope this brief motivates further exploration of this important research topic.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/flw.2025.10004.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the FINRA Investor Education Foundation, FINRA, or any of its affiliated companies.