Introduction

People with a cancer diagnosis often experience psychological distress related to feelings of anxiety, depression, fear, or guilt and are often at increased risk of developing mental disorders (Tallman et al. Reference Tallman, Altmaier and Garcia2007; Mols et al. Reference Mols, Vingerhoets and Coebergh2009; Kucukkaya Reference Kucukkaya2010; Singer et al. Reference Singer, Das-Munshi and Brähler2010; Martins da Silva et al. Reference Martins da Silva, Moreira and Canavarro2011; Campos-Ríos Reference Campos-Ríos2013; Costa et al. Reference Costa, Mercieca‐bebber and Rutherford2016; Vrontaras et al. Reference Vrontaras, Koulierakis and Ntourou2023), which impact their quality of life and increase cancer-specific mortality by up to 53% (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Fang and Sjölander2017). However, it is increasingly recognized that cancer can also enable individuals to grow and experience what is known as posttraumatic growth (PTG) (Tedeschi et al. Reference Tedeschi, Shakespeare-Finch and Taku2018; Kou et al. Reference Kou, Wang and Li2021; Almeida et al. Reference Almeida, Ramos and Maciel2022). PTG is defined as the cognitive process by which people who have experienced a traumatic event reinterpret their experience positively and find new meaning in it (Tedeschi and Calhoun Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun2004). Thus, those with a cancer diagnosis may manifest greater appreciation for life, changed priorities, improved interpersonal relationships with empathy and compassion, and greater spirituality and deepening of spiritual beliefs (Tanyi et al. Reference Tanyi, Mirnics and Ferenczi2020; Menger et al. Reference Menger, Mohammed Halim and Rimmer2021).

Several factors have been associated with PTG in people with cancer and terminal cancer; these include spirituality, social support, previous experience in managing illness, life adversity, meaning-making, reconciliation with the finitude of life, acceptance of illness, self-management, determination, positive attitude, dignity, commitment to palliative care, quality of life (Lau et al. Reference Lau, Khoo and Ho2021), hope (Hullmann et al. Reference Hullmann, Fedele and Molzon2014), and coping strategies, as well as gender (Baghjari et al. Reference Baghjari, Esmaeilinasab and Shahriari-Ahmadi2017). A systematic which described the main findings on PTG in cancer, found that PTG was inversely associated with depression and anxiety symptoms and directly related to hope, optimism, spirituality, and meaning (Casellas-Grau et al. Reference Casellas-Grau, Ochoa and Ruini2017).

In a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted between 2005 and 2019 with cancer patients (Marziliano et al. Reference Marziliano, Tuman and Moyer2020), only 2 studies (Mystakidou et al. Reference Mystakidou, Parpa and Tsilika2007, Reference Mystakidou, Tsilika and Parpa2008) included patients in advanced stages and at the end of life. The results indicated that as the perceived threat of an event increases, patients’ interpersonal relationships are strengthened, leading to a greater appreciation of life and thus an increase in PTG.

The concept of PTG is gaining relevance in palliative care. Although the number of studies is limited, early indications suggest that interventions to foster PTG may contribute significantly to improving the psychological well-being of people receiving palliative care (Austin et al. Reference Austin, Siddall and Lovell2024).

A systematic review by Moreno and Stanton (Reference Moreno and Stanton2013) identified that many people with advanced cancer consider it important to find meaning at the end of life. Additionally, they perceive positive consequences of their experience, which may contribute to greater levels of personal growth. Fear of cancer progression reduces PTG; therefore, psychosocial intervention or psychotherapy should focus on counteracting predictors related to the healthcare system and information, patient care and support, and unmet psychological needs (Nik Jaafar et al. Reference Nik Jaafar, Hamdan and Abd Hamid2022). Related interventions should address the various elements of the PTG model, including core beliefs about the world, self, and others; emotional distress management; coping; and rumination, understood as the cognitive process in which repeatedly thinking about the experienced event or its consequences generates conscious thought by identifying the positive part of the traumatic event (Vrontaras et al. Reference Vrontaras, Koulierakis and Ntourou2023). In this regard, Eissensta et al. (Reference Eissensta, Kim and Kim2022) suggest that coping strategies like problem-focused, positive emotion-focused, negative emotion-focused, and unclassified coping contribute to psychological growth after traumatic events, and Gori et al. (Reference Gori, Topino and Sette2021) mention that coping strategies like social support, avoidance, positive attitude, approach coping, and turning to religion are mediators of PTG.

Several instruments have been developed to assess the subjective experience of positive psychological change following traumatic events to determine the existence of PTG and thus guide necessary interventions. Among these instruments are the Secondary Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (Ogińska-Bulik and Juczyński Reference Ogińska-Bulik and Juczyński2022), the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Bagherzadeh et al. Reference Bagherzadeh, Loewe Pujol-Xicoy and Batista Foguet2018), the Benefit Seeking Scale (Antoni et al. Reference Antoni, Lehman and Kilbourn2001), the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index (Steinberg et al. Reference Steinberg, Brymer and Decker2004), and the Impact of Events Scale (Weiss and Marmar Reference Weiss and Marmar1997). However, the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) has been the primary tool for measuring PTG (Tedeschi and Calhoun Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun1996; Marziliano et al. Reference Marziliano, Tuman and Moyer2020).

The PTGI comprises 21 items designed for individuals to report the degree of positive change experienced after a potentially traumatic event. The original version of the PTGI considers 5 dimensions: relationships with others (RO), new possibilities (NP), personal strength (PS), spiritual change (SC), and appreciation of life (AL) (Tedeschi and Calhoun Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun1996).

This instrument has been validated in cancer patients in multiple countries, including France (Cadell et al. Reference Cadell, Suarez and Hemsworth2015; Dubuy et al. Reference Dubuy, Sébille and Bourdon2022), Iran (Mehdi Heidarzadeh et al. Reference Mehdi Heidarzadeh, Farahnaz and Hamid2015), South Korea (Jung and Park Reference Jung and Park2017), Canada (Brunet et al. Reference Brunet, McDonough and Hadd2010), China (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Wang and Hua2015), Portugal (Teixeira and Pereira Reference Teixeira and Pereira2013), the Netherlands (Jaarsma et al. Reference Jaarsma, Pool and Sanderman2006), and Turkey (Aydin and Kabukçuoğlu Reference Aydin and Kabukçuoğlu2020). In the Spanish-speaking context, it has been validated with the Latino population residing in the United States (Weiss and Berger Reference Weiss and Berger2006), as well as in Spain (Costa-Requena and Moncayo Reference Costa-Requena and Moncayo2007), Argentina (Esparza-Baigorri et al. Reference Esparza-Baigorri, Leibovich de Figueroa and Martínez-Terrer2016), Peru (García et al. Reference García, Cova and Melipillan2013; Paz Poblete Reference Paz Poblete2020), and Chile (Leiva-Bianchi and Araneda Reference Leiva-Bianchi and Araneda2015). Two validations have been conducted in Mexico: one after the 2017 earthquake (Penagos-Corzo et al. Reference Penagos-Corzo, Tolamatl and Espinoza2019) and another with people who experienced traumatic situations (Quezada Berumen and González-Ramírez Reference Quezada Berumen and González-Ramírez2021).

The PTGI developers (Tedeschi et al. Reference Tedeschi, Cann and Taku2017) introduced 4 new items related to spiritual and existential change (SEC), resulting in the 25-item PTGI-X. This updated inventory incorporates diverse perspectives on spiritual and existential experiences present in multiple cultures. The new SEC factor, comprising 6 items, shows high internal reliability. The expanded 5-factor structure was also corroborated by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

The PTGI-X version has been validated in various contexts, such as postpartum women, patients with addictions, bereavement, and traumatic events in general, obtaining satisfactory internal reliability values in countries such as the United States, Turkey, Japan (Tedeschi et al. Reference Tedeschi, Cann and Taku2017), China (McBurnie et al. Reference McBurnie, Bell and Hurst2024), Italy (Romeo et al. Reference Romeo, Di Tella and Rutto2023), Georgia (Khechuashvili Reference Khechuashvili2018), and South Korea (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Lee and Lee2023); the short version of the PTGI (PTGI-X-SF-J) has been validated in Japan (Oshiro et al. Reference Oshiro, Soejima and Kita2023). However, in Spanish, in the Latin American context, it has only been validated in Peru, but with adolescents who experienced the loss of a loved one (Ramos-Vera et al. Reference Ramos-Vera, O’Diana and Vallejos-Saldarriaga2023) and COVID-19 (Lazo Cárdenas Reference Lazo Cárdenas2024).

Considering that no Spanish validation of the PTGI-X in patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care was identified in the literature review, a need was established to adapt the PTGI-X for the population in Mexico and confirm its validity and reliability, in addition to confirmatory analyses providing evidence for the theoretical model. Therefore, the objective of this study is to cross-culturally adapt and psychometrically validate the PTGI-X in a sample of people receiving palliative care in Mexico.

Method

A prospective, non-experimental, non-probabilistic convenience sampling study was conducted, divided into 2 phases: the first involved translating the PTGI-X from the original language into Spanish and adapting it cross-culturally to patients with advanced cancer, and the second involved validating it to confirm its psychometric properties.

The study was approved by the Research and Research Ethics Committees of the National Cancer Institute with reference number 018/050/CPI.

Procedure

Phase 1

The translation, adaptation, and validation process began with the authorization to use the instrument by the creators of the PTGI-X (Tedeschi et al. Reference Tedeschi, Cann and Taku2017).

Subsequently, it was translated into Spanish by a certified bilingual (English–Spanish) translator. The translation was compared with previous Spanish versions (Penagos-Corzo et al. Reference Penagos-Corzo, Tolamatl and Espinoza2019; Quezada Berumen and González-Ramírez Reference Quezada Berumen and González-Ramírez2021) and sent to 6 expert judges in palliative medicine, palliative psychology, and medical oncology, who evaluated the content validation format (Lee Reference Lee2017) based on 5 criteria: sufficiency, clarity, coherence, relevance, and pertinence.

Based on the responses obtained, relevant modifications were made, resulting in the PTGIX in Spanish for the Mexican oncology population (PTGI-X-Mx). A pilot study was conducted with 20 applications to evaluate and adjust the relevance, grammatical and semantic equivalence, cultural relevance, and linguistic adequacy of the items, complying with the analytical-rational procedures (Gudmundsson Reference Gudmundsson2009).

Phase 2

For the instrument validation, a minimum of 200 participants was estimated to confirm the model validity (ITC Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests (Second Edition) 2018). The final version of the PTGI-X-Mx was used for this phase. Participant selection was conducted in the outpatient clinic of the palliative care service. The psycho-socio-spiritual screening recorded in the electronic file, performed on all first-time patients as part of the palliative care process – which assesses cognitive functioning, level of emotional distress and associated problems, perceived family functioning, and identification of spiritual needs – was reviewed to identify potential participants, mainly because patients with cognitive impairment or uncontrolled physical symptoms could not participate.

Participants

The total sample was 236 patients diagnosed with advanced-stage cancer who were referred by the oncology treatment teams to receive care in the palliative care service due to the presence of multiple symptoms generated by the progression of the disease, disease-modifying cancer treatments (supportive care), or by being outside oncology management (end-of-life management).

The inclusion criteria were participants aged over 18 who were literate and free of uncontrolled symptoms such as delirium, pain, nausea, vomiting, or dyspnea at the time of evaluation. Patients without mild or severe cognitive impairment or severe psychiatric disorders and with a first-time or subsequent diagnosis of advanced cancer who attended the outpatient clinic of the palliative care service of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico (INCan) were invited to participate. Patients meeting the inclusion criteria were told the study’s objective, asked for their voluntary participation, and informed about their right to participate or not. If they agreed, they were asked to sign an informed consent form authorized by the INCan Research Ethics Committee CEI/1270/18.

Instruments

Sociodemographic and clinical data collection: Categorical variables: age, sex, marital status, education, religious beliefs, type of care, and type of cancer.

PTGI version X (PTGI-X; Tedeschi et al. Reference Tedeschi, Cann and Taku2017). This version was developed from the PTGI version and enriched by considering the specific cultural needs identified in validations conducted in different countries. The result was the final version of the PTGI-X with 25 items, with 4 related to spiritual-existential change. Its factor structure comprises 5 factors: personal strength (4 items), new possibilities (5 items), relationships with others (7 items), appreciation of life (3 items), and existential/spiritual change (6 items). The responses, of the 6-point Likert type, range from 0 (I did not experience this change due to my crisis) to 5 (I experienced this change largely due to my crisis). The internal reliability values of the total PTGI-X scale are 0.97 for the United States, 0.96 for Turkey, and 0.95 for Japan. The fit indices obtained for the 5 factors in the original version (Tedeschi et al. Reference Tedeschi, Cann and Taku2017) were χ2 = 2347.93, DF = 265, RMSEA = 0.086, NFI = 0.868, CFI = 0.890, and TLI = 0.876.

Perception of quality of life (PQOL). Quality of life was subjectively assessed based on each participant’s responses using the Visual Numerical Scale, from 0 (very bad) to 10 (excellent), by asking the following question: What number from 0 to 10 would you assign to your overall QOL in the last month?

Analysis plan

Phase 1. Cross-cultural adaptation.

Descriptive analyses of the demographic variables were performed, including frequencies and percentages for the categorical variables: age, sex, marital status, federal entity, religious belief, type of tenure, and oncological diagnosis.

Phase 2. Validation.

The following analyses were performed to confirm the validation of the PTGI-X-Mx:

1) Item analysis under the classical test theory (CTT), evaluating descriptive statistics, discrimination indices, and internal consistency through Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (Embretson and Reise Reference Embretson and Reise2013), through R with the Psych package and CTT (Revelle Reference Revelle2007; Willse Reference Willse2008).

2) For construct validity, the theoretical model proposed for the PTGI-X-Mx was assumed, and a CFA was performed directly using the lavaan package in R (The R Project for Statistical Computing (n.d.); Rosseel Reference Rosseel2012).

3) The model fit was examined through the CFI (≥ 0.90 acceptable, ≥ 0.95 excellent), TLI (≥ 0.90 acceptable), RMSEA (≤ 0.08 acceptable, ≤ 0.06 excellent), and SRMR (≤ 0.08) indices (Hu and Bentler Reference Hu and Bentler1999).

4) Additionally, convergent and divergent validity analysis was performed using Pearson correlations between factors.

Results

Sample characteristics

Of the 240 participants who agreed to participate in the study, 4 were excluded: 2 due to difficulties in understanding the scale, 1 due to lack of time to complete the instruments, and 1 because he required psychological intervention during the application of the scale, so the final sample comprised 236. Of the participants, 72.5% were women, with a mean age of 52 (SD ± 14.3); 51.2% were married, with 7 to 13 years of schooling (51%); the majority resided in Mexico City (39.4%) and the metropolitan area of the State of Mexico (31.8%); and 79% professed the Catholic religion. In total, 86% received supportive care, and only 14% received end-of-life care. The main types of cancer were breast (25.8%), gynecological (20.3%), and gastrointestinal (18.6%) tumors, and the PQOL was ![]() ${{\bar X}}$ = 6.61, as shown in Table 1.

${{\bar X}}$ = 6.61, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample (N = 236)

SD = Standard deviation

a Income reported in dollars as of June 4, 2025; 1 Mexican peso = 19.19 USD.

Item analysis

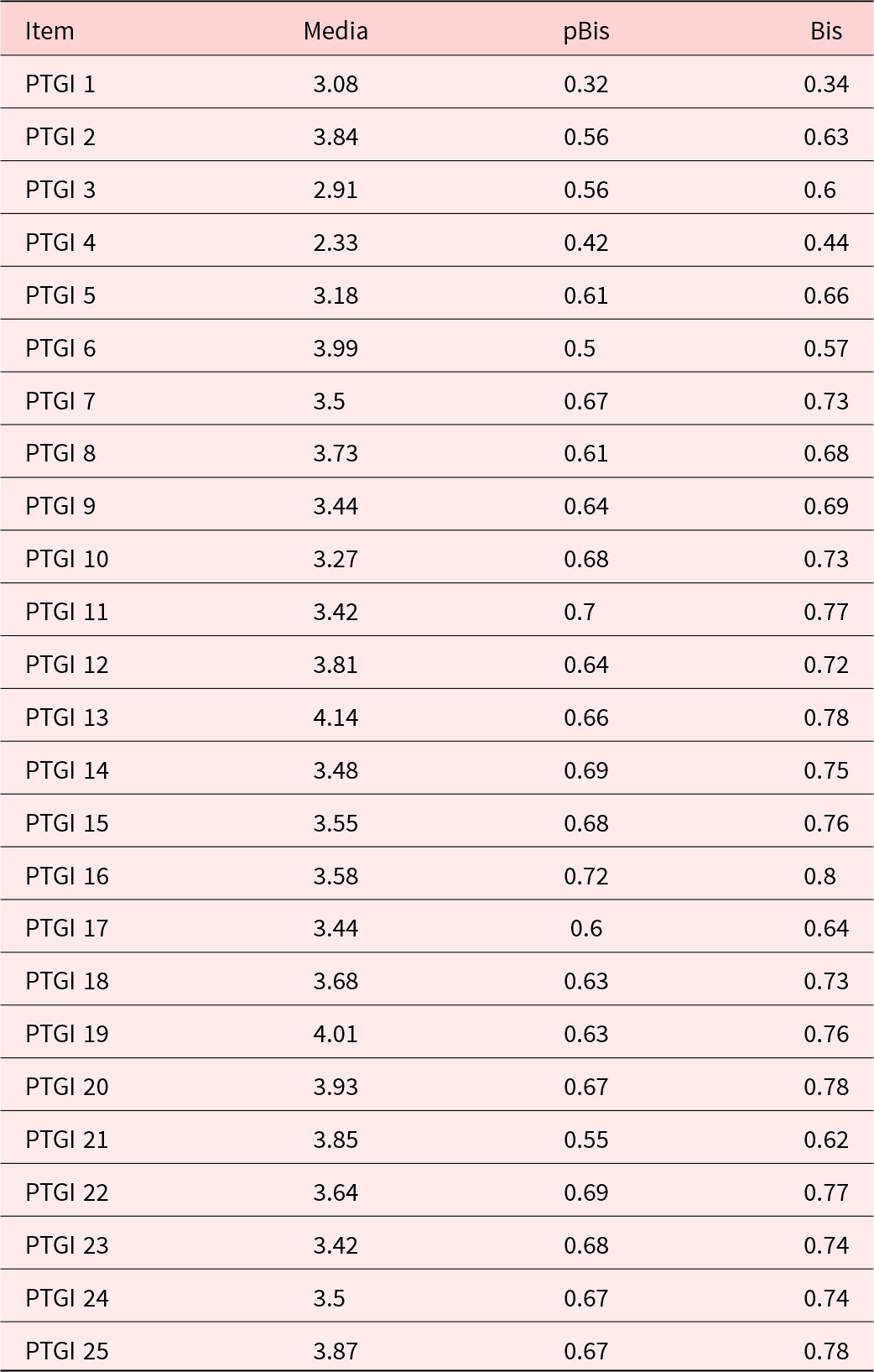

An item discrimination analysis was conducted under the CTT, (See Table 2).The discrimination coefficients (pBis) ranged from 0.32 (item 1) to 0.72 (item 16), exceeding the threshold of 0.30 considered acceptable. In the specific case of item 1 (pBis = 0.32), although this presented the lowest discrimination value, it was retained due to its theoretical relevance in the model proposed by the authors of the scale (Tedeschi et al. Reference Tedeschi, Cann and Taku2017).

Table 2. Item analysis using classical test theory

Internal consistency index

Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale with 25 items was 0.94, indicating excellent internal consistency. Regarding the 5 dimensions of the PTGI-X-Mx, the alpha coefficients were (1) SEC α = 0.856, (2) AL α = 0.630, (3) PS α = 0.749, (4) NP α = 0.799, and (5) RO α = 0.866. Apart from the AL subscale, whose values were considered moderate, the factors showed good or excellent internal consistencies.

CFA

The theoretical 5-factor model (SEC, AL, PS, NP, and RO) for the PTGI-X-Mx was assumed, and its fit was evaluated by CFA. The result indicated a scaled χ2 statistic of 749.01 (df = 265; χ2df = 2.83), with CFI = 0.93 and TLI = 0.93, which exceeded the criterion of 0.90 for an adequate fit. The RMSEA was 0.088 (90% CI: 0.081–0.096), close to the acceptable range (≤ 0.08), and the SRMR was around 0.065, below 0.08. Overall, these indices suggest an acceptable overall model fit.

The standardized factor weights (λ) ranged from 0.44 (item 1 in the AL factor) to 0.89 (item 13 in AL), indicating that most of the items contributed adequately to their respective factors. Although item 1 presented the lowest loading, it was retained due to its theoretical relevance, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Factor loadings of the confirmatory factor analysis

Spiritual and existential change (SEC), appreciation of life (AL), personal strength (PS), new possibilities (NP), and relationships with others (RO).

Convergent and divergent validity

Convergent validity. Bivariate correlations between the factors of the PTGI-X-Mx were used to assess convergent/divergent validity; the results showed moderate positive associations between the scale factors (r = 0.60–0.79).

Divergent validity. The association between the factors of PTG and quality of life perception was examined; as theoretically expected, positive correlations of low magnitude (r = 0.14–0.18) were observed, all statistically significant (p < .05) (See Table 4). These results support the divergent validity of the scale by showing that although a relationship exists between PTG and perceived quality of life, it is modest, indicating that the 2 constructs are related but distinct.

Table 4. Correlation matrix between the PTGI-X-Mx factors and QOL perception

Discussion

The results of this study support the construct validity and reliability of the PTGI-X-Mx translated and adapted for a Mexican context in a sample of advanced cancer patients receiving palliative care. Through a rigorous CFA approach, it was observed that the 5-factor structure originally proposed (Tedeschi et al. Reference Tedeschi, Cann and Taku2017) remained stable and conceptually consistent in this population. The 5 dimensions – SEC, appreciation of life, personal strength, new possibilities, and relationships with others – reflect various forms of positive coping during trauma and emerged empirically as distinguishable but interrelated constructs.

Overall, the model showed a reasonably satisfactory fit, with acceptable standardized factor loadings on most of the items. Although item 1 (“changing my priorities about what is important in life”) had a lower discrimination index and factor loadings, it was retained due to its conceptual importance in PTG theory. One of the key manifestations of PTG is the transformation of life priorities, which justifies its inclusion despite its lower statistical performance (Tedeschi and Calhoun Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun2004).

Regarding reliability, Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was 0.94, indicating excellent internal consistency (Embretson and Reise Reference Embretson and Reise2013). The individual subscales presented coefficients of 0.63–0.86. While most dimensions showed good or excellent values, the Appreciation of Life (α = 0.63) was only moderate. This aligns with previous validations of the PTGI, where this factor often shows lower reliability, partly because it is typically composed of a few items and reflects a more heterogeneous construct (Tedeschi and Calhoun Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun2004). Lower internal consistency in such brief subscales is not unusual, as Cronbach’s alpha is highly sensitive to the number of items. Still, this suggests that the Appreciation of Life dimension might benefit from further refinement, either by revising the wording of existing items or by adding additional items that capture this domain more comprehensively. Importantly, the moderate reliability does not invalidate the subscale but highlights an area for future psychometric improvement in subsequent applications of the PTGI-X-Mx.

The results also evidenced moderate correlations among the factors, indicating that each measures a distinctive aspect of PTG but all are linked under the same transformative experience. This internal consistency across dimensions supports the conception of PTG as a complex and multifaceted construct (Tedeschi et al. Reference Tedeschi, Shakespeare-Finch and Taku2018).

However, the relationship between the factors of the PTGI-X-Mx and a brief measure of perceived quality of life was examined. As theoretically anticipated, the correlations were positive, although low-magnitude (r = 0.14–0.18, p < .05). This modest but significant association supports the divergent validity of the instrument by showing that PTG contributes to, but does not fully define, overall well-being (Revelle Reference Revelle2007). That is, PTG can coexist with adverse physical health conditions or functional limitations but still represents an important psychological resource in adapting to advanced cancer, so it would be worth considering coping strategies.

In summary, the PTGI-X-Mx showed satisfactory psychometric properties in the Mexican population with advanced disease. Its maintenance of the original structure reinforces its usefulness as a valid and culturally appropriate tool for assessing positive coping processes in palliative care patients. The instrument not only enables a better understanding of how some people find meaning, strength, or deeper relational connections after facing a terminal diagnosis but also guides clinical interventions to strengthen these personal resources.

The present study provides solid evidence for the psychometric properties of the PTGI-Expanded version adapted for Mexico (PTGI-X-Mx), confirming its usefulness in assessing PTG in patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care. The 5-dimensional factor structure showed an adequate fit and remained consistent with the theoretical model, reflecting the multidimensional complexity of the positive coping process during trauma. In this regard, Eissensta et al. (Reference Eissensta, Kim and Kim2022) suggest that positive emotion-focused and problem-focused coping strategies contribute to psychological growth after traumatic events.

Analyses supported the instrument’s construct validity and reliability. Additionally, positive but low-magnitude correlations with perceived quality of life provided evidence of divergent validity, underscoring that PTG is a distinct phenomenon, albeit related to general well-being. This finding is particularly relevant in the context of palliative care, where psychological resources may be central to the life experience of people with advanced illness.

Limitations of the study

Despite the positive findings, this study has limitations. Firstly, although the sample size was sufficient for the analyses conducted, a larger sample would enable more precise evaluation of factorial invariance between sociodemographic and clinical subgroups. Second, the use of a convenience sample may limit the representativeness of the findings. Participants were recruited from a single population of individuals with advanced cancer receiving palliative care, which implies that those willing or able to participate could differ systematically from those who did not, potentially introducing self-selection bias. This limits the generalizability of the results not only to other clinical conditions but also to the broader population of patients with cancer in earlier stages or diverse treatment settings. Finally, while the results support the internal validity of the PTGI-X-Mx, future studies should incorporate probabilistic or stratified sampling strategies to enhance external validity and replicate these findings across more diverse clinical and cultural contexts, as well as examine the instrument’s sensitivity to change following interventions designed to strengthen PTG.

However, a tool such as the PTGI-X-Mx will be extremely helpful in clinical and research contexts in palliative care to evaluate positive changes such as appreciation of life and improvement of interpersonal relationships, realization of one’s potential, satisfying relationships, a sense of purpose in life, and resilience during adversity (Izgu et al. Reference Izgu, Metin and Eroglu2024).

Conclusion

Overall, the PTGI-X-Mx is positioned as a valid, reliable, and culturally relevant tool for the Mexican context. Its use can enrich clinical evaluation and psycho-oncological research, in addition to guiding interventions focused on strengthening the meaning of life, resilience, and personal transformation in situations of extreme suffering. Future studies may expand its application in other populations and explore their sensitivity to change after specific therapeutic interventions.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951525101132.

Data availability statement

In accordance with data protection regulations, the data set cannot be made public. However, the data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

Ascencio L and García-Beníetez CA designed the study, adapted the scale to Spanish, and conducted the pilot study in Spanish. Austria F. performed the statistical analyses; Ascencio L, Astudillo CI and Austria F. wrote the final version of the article; and Ascencio L, Austria F, Astudillo, CI, García-Benítez CA and Allende SR approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors indicate no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practices, and Standards established in the General Health Law of Mexico regarding research.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Ximena Flores, Paloma Deveze, and Atalia Alemán for their support in applying the evaluation instruments.