Introduction

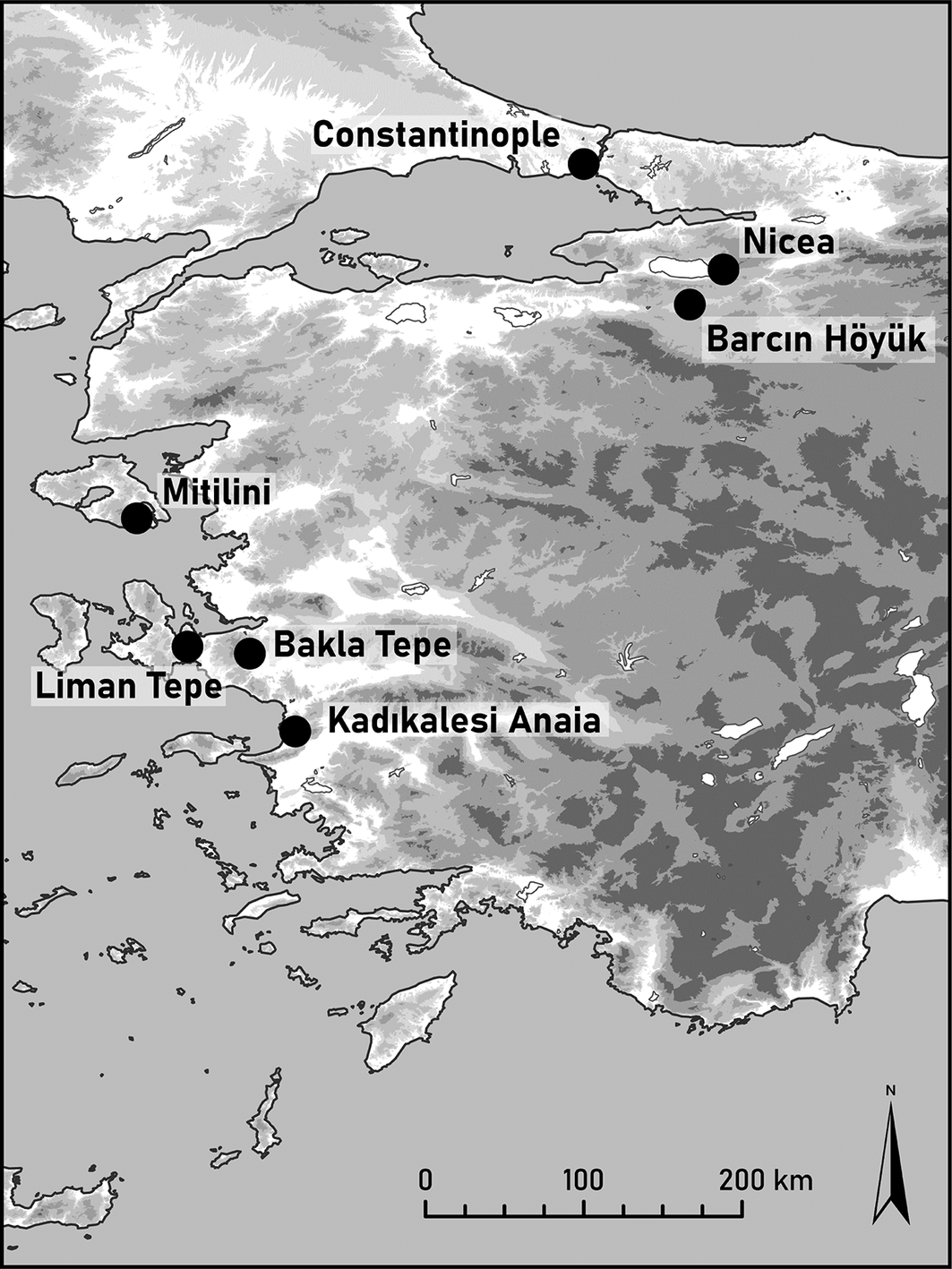

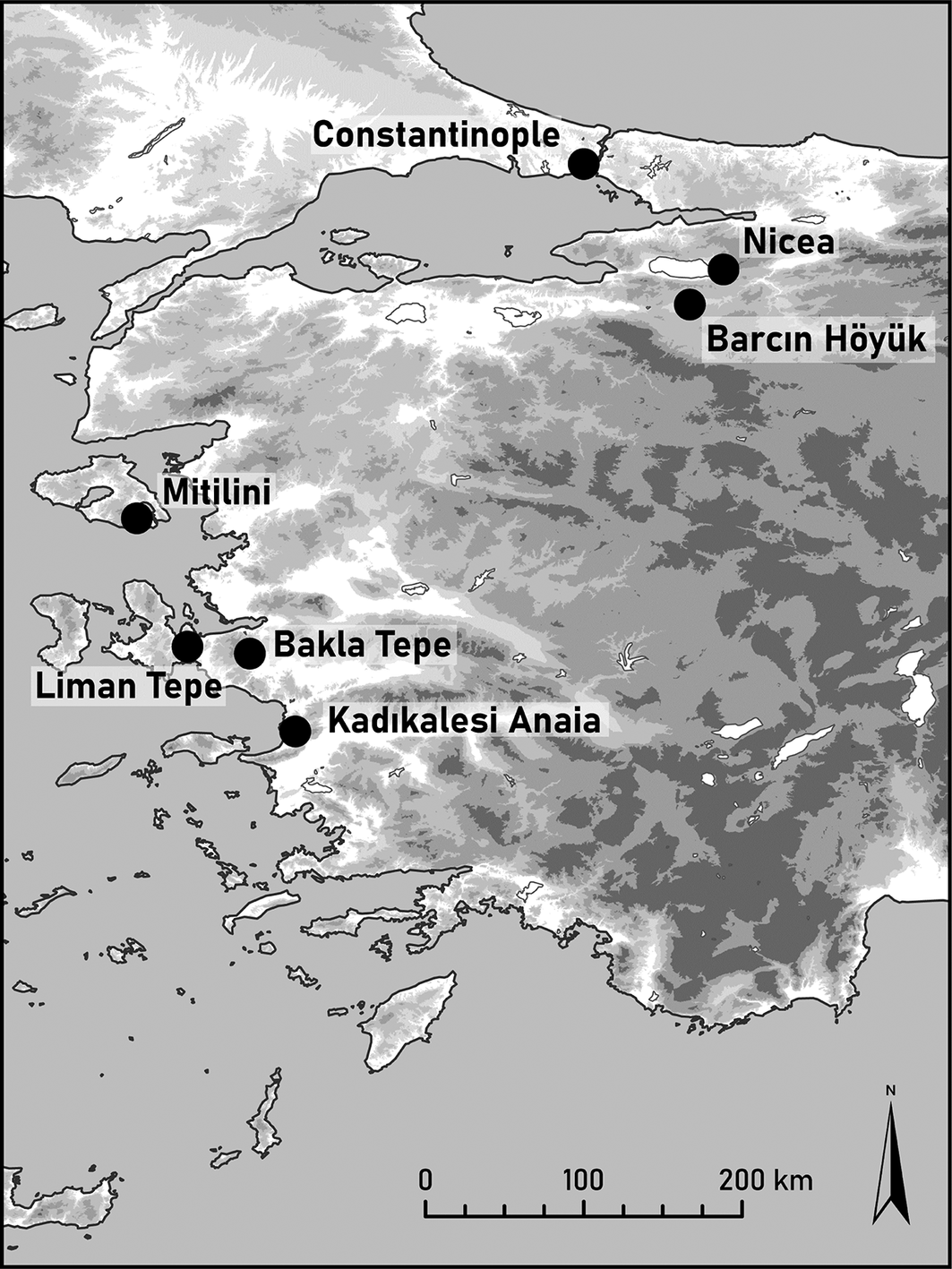

Byzantine-period communities in Anatolia occupied diverse environmental settings, from inland agricultural plains to coastal centres engaged in maritime exchange. This study examines two such contexts dating to the Byzantine period. Diet related questions for Barcın Höyük, located in the Yenişehir Plain of Bursa in north-western Turkey, and Kadıkalesi Anaia, on the Aegean coast (Figure 1), are addressed through stable isotope ratio analysis of human remains. This is complemented by ancient DNA (aDNA) data from Byzantine-period Barcın Höyük, which indicates a predominant local genetic continuity but also mobility in the region. No aDNA data are available for Kadıkalesi.

Figure 1. Map showing the location of sites discussed in the text.

For the Byzantine period, our knowledge of what people ate is largely derived from textual sources and iconographic representations (Teall, Reference Teall1959; Vroom, Reference Vroom2000; Kokoszko, Reference Kokoszko and Pires2015; Laurioux, Reference Laurioux, Wilkins and Nadeau2015; Linardou & Brubaker, Reference Linardou and Brubaker2016; Koder, Reference Koder and Mango2017), along with insights from zooarchaeological and archaeobotanical studies (Gorham, Reference Gorham2000; van Zeist et al., Reference van Zeist, Bottema and Van der Veen2001; Kroll, Reference Kroll2012; McKinnon, Reference McKinnon2019; Baron & Marković, Reference Baron, Marković, Bergerbrant and Hansen2020; Ulaş, Reference Ulaş2020). Iconography, ancient written documents including tax records and recipes, and faunal and botanical remains provide general information on Byzantine dietary habits. For nearly two decades, stable isotope analyses have been commonly used to gain further insights on this issue. These analyses have yielded data related to individual and demographic traits such as age and sex, enabling direct connections between individuals and their isotopic values. This approach reveals specific dietary patterns and offers insights into phenomena such as the potential roles of fasting and asceticism in Byzantine communities (McGowan, Reference McGowan1999; Grimm, Reference Grimm2002; Bourbou & Richards, Reference Bourbou and Richards2007; Bourbou et al., Reference Bourbou, Fuller, Garvie-Lok and Richards2011; Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, De Cupere, Marinova, Van Neer, Waelkens and Richards2012a; Gregoricka & Sheridan, Reference Gregoricka and Sheridan2013; Özdemir, Reference Özdemir2018; Özdemir et al., Reference Özdemir, Itahashi, Yoneda and Erdal2025). While several Byzantine cemeteries in Greece, Crete, and the Balkans have been studied isotopically, few analyses have focused on Asia Minor. One recent example is the Kovuklukaya cemetery in northern Anatolia, which revealed a mixed terrestrial and marine-based diet (Özdemir et al., Reference Özdemir, Itahashi, Yoneda and Erdal2025).

Here we combine isotopic evidence with aDNA analysis to explore not only dietary variation, but also how ancestry and mobility may have shaped access to foods. This integrated approach provides a fuller picture of Byzantine lifeways, highlighting both dietary habits and population movement in the region.

The Settlements and the Region

Kadıkalesi Anaia, located on the Aegean coast of Turkey south of Izmir, dates to the Late Byzantine period, i.e. the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries ad. It was a fortified commercial port city engaged in manufacturing and transport (Mercangöz, Reference Mercangöz2005). After the Crusaders’ conquest of Constantinople in 1204, the Nicene State controlled much of western Anatolia. Italian city-states increased maritime trade during this time. Anaia, described in a 1278 Pisan trade manual, served as a seaport along the route connecting Constantinople to Alexandria, providing silk and local supplies such as grain (Jacoby, Reference Jacoby, Berger, Mariev, Prinzing and Riehle2016: 56). The fortified city included a monumental church and a palace, possibly for the ruling Laskaris family (Mercangöz, Reference Mercangöz2005: 212; see also Foss, Reference Foss1979: 124). By the early fourteenth century, Pisa had established a notary in Anaia, making this a well-connected and international city that attracted Italian traders (İnanan, Reference İnanan2015: 153; Jacoby, Reference Jacoby, Berger, Mariev, Prinzing and Riehle2016: 56). Excavations since 2001 have yielded ceramics, ivory, metal objects, glass, and coins, highlighting Anaia’s role within broader Byzantine economic networks (Ünal & Toy, Reference Ünal and Toy2020: 80–81). Most graves, some of which may belong to members of the clergy, are associated with the city’s main monumental church (Ünal & Toy, Reference Ünal and Toy2020: 83).

Barcın Höyük, in Yenişehir, Bursa, is notable for its Neolithic levels dated to the seventh millennium bc (Gerritsen & Özbal, Reference Gerritsen and Özbal2019; Özbal & Gerritsen, Reference Özbal, Gerritsen and Hore2019). The site consists of a double mound, with excavations from 2005 to 2015 focused only on the eastern high mound. The most recent remains include a Middle Byzantine cemetery dating from the eighth to eleventh centuries. While no Byzantine settlement was discovered on the excavated mound, it may be present on the unexcavated western mound, with the eastern mound serving as a cemetery (Gerritsen, Reference Gerritsen2009; Roodenberg, Reference Roodenberg, Vorderstrasse and Roodenberg2009).

Barcın Höyük, unlike the cosmopolitan Kadıkalesi Anaia, was probably a rural community near Nicaea (Lefort, Reference Lefort and Laiou2002). The Barcın cemetery must have been associated with a chapel, as is typical for the period (Gerstel, Reference Gerstel2015), but excavations yielded little evidence for architecture, save a few fragments of marble and plaster. Among finds from this cemetery, artefacts such as a tenth-century seal, likely to have belonged to a local landowner, and an eleventh-century reliquary cross are noteworthy and may indicate connections with larger centres, which is not unusual for Byzantine rural contexts (Roodenberg, Reference Roodenberg, Vorderstrasse and Roodenberg2009; Androshchuk, Reference Androshchuk, Garipzanov and Tolochko2011; Vorderstrasse, Reference Vorderstrasse2016). Altogether, the data suggest that Barcın Höyük lacked the prominence of larger settlements; Kadıkalesi Anaia and Barcın Höyük had different inter-regional connections, which shaped their economies, subsistence strategies, networks, and social diversity, reflected in their residents’ diets.

The Byzantine Barcın Höyük cemetery contained only human remains and few grave goods; it yielded no animal bone for comparative study. At Kadıkalesi, zooarchaeological remains have been analysed but none has undergone isotopic sampling, and archaeobotanical results are yet to be published. These gaps complicate the reconstruction of reliable isotopic baselines.

Stable isotope ratio analysis relies on the fact that the isotopic composition of human tissues reflects the consumption of foods, which in turn are structured by the isotopic baselines of their environments (DeNiro & Epstein, Reference DeNiro and Epstein1978; Schoeninger & Moore, Reference Schoeninger and Moore1992). Carbon (δ 13C) and nitrogen (δ 15N) values from bulk bone collagen provide insights into dietary habits: δ 13C values help distinguish between plant types based on their photosynthetic pathways (C₃ vs C₄), as well as between terrestrial and marine resources (van der Merwe & Vogel, Reference van der Merwe and Vogel1978; O’Leary, Reference O’Leary1988). Nitrogen (δ 15N) values reflect an individual’s position in the food web, typically increasing with each step up the trophic level (which typically reflects an increase of 3‰), providing a proxy for the contribution of animal versus plant protein over an average of several years (Ambrose & Norr, Reference Ambrose, Norr, Lambert and Grupe1993; Bocherens & Drucker, Reference Bocherens and Drucker2003). Elevated δ 15N values can also identify infants breastfed at the time of their death, offering insights into infant feeding and weaning practices (Beaumont et al., Reference Beaumont, Montgomery, Buckberry and Jay2015; Chinique de Armas et al., Reference Chinique de Armas, Mavridou, Garcell Domínguez, Hanson and Laffoon2022).

Materials and Methods

In the δ 13C and δ 15N analyses, thirty-eight human rib samples (twenty-one from Kadıkalesi and seventeen from Barcın), primarily representing adults, were examined. The isotopic analysis here emphasizes the range of human values and focuses on the spread between the highest and lowest measurements. Domesticated herbivores from prehistoric levels were used for comparison at both sites, with the caveat that environmental and climatic conditions may have changed and that animal diets may have been affected by human practices such as foddering or manuring. In addition, aDNA analyses were conducted for sixteen individuals from Barcın Höyük to assess the degree of genetic relatedness and familial connections within this Byzantine village (see Table S2 for a breakdown by site, sex, age, and Table S4 for aDNA-related data). Based on the proportion of authentic human DNA recovered (median = 15 per cent) and preliminary contamination assessments, seven samples were selected for deeper sequencing and subsequent downstream analyses. No aDNA analysis has been conducted to determine genetic relationships at Kadıkalesi.

The Supplementary Material provides explanations of the methods employed in this study, including bioarchaeological and anthropological measurement procedures, sexing criteria, and protocols for collagen and aDNA extraction. Briefly, the collagen extracted from rib samples used a modified Longin (Reference Longin1971) protocol, while the aDNA extraction adhered to a modified Dabney et al. (Reference Dabney, Knapp, Glocke, Gansauge, Weihmann and Nickel2013) protocol.

Results

The isotopic study followed the quality criteria set by DeNiro (Reference DeNiro1985), Ambrose (Reference Ambrose1990), Guiry and Szpak (Reference Guiry and Szpak2021), and Vaiglova et al. (Reference Vaiglova, Lazar, Stroud, Loftus and Makarewicz2023). At Kadıkalesi twenty-one of the twenty-three analysed samples (91 per cent), met the quality criteria; at Barcın Höyük, this was 74 per cent (seventeen out of twenty-three samples). Barcın Höyük’s successful samples included males, females, children, and infants as well as adults of undetermined sex, whereas at Kadıkalesi the dataset primarily comprised adult males and females, with two children buried alongside adult females. The Barcın Höyük sample reflects seventeen of the sixty-two individuals excavated there (27 per cent), which represents an unknown percentage of the total graves present at the site. The Kadıkalesi sample is likely to represent only a small part of the overall population.

Budd et al. (Reference Budd, Galik, Alpaslan Roodenberg, Schulting and Lillie2020) report a δ 13C mean value of –19.8‰±1.3 (standard deviation, SD hereafter) for the domesticated herbivores at Neolithic Barcın, with a mean δ 13C value of –19.5‰±0.4 (SD) for Neolithic human adults. The mean δ 13C value for Byzantine non-infants (i.e. older than 2.5 years) was –19.0‰ (±0.3 SD; 95 per cent CI―confidence interval, CI hereafter—= [–19.2‰, –18.8‰]), slightly less negative than Neolithic values. This aligns with the broader trend towards more positive δ 13C values in Byzantine populations (Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, De Cupere, Marinova, Van Neer, Waelkens and Richards2012a; Xoplaki et al., Reference Xoplaki, Fleitmann, Luterbacher, Wagner, Haldon and Zorita2016; Sołtysiak & Schutkowski, Reference Sołtysiak and Schutkowski2018; Irvine, Reference Irvine2022: 69). Kadıkalesi yielded a mean δ 13C value of –19.1‰ (±0.4 SD; 95 per cent CI = [–19.3‰, –18.9‰]). Herbivore δ 13C values for nearby Bronze Age Baklatepe were –19.3‰±1.1 (SD) and the human δ 13C values for the same site were 19.7‰±0.3 (SD) (Irvine & Erdal, Reference Irvine and Erdal2020). At Barcın Höyük, Neolithic adults had a mean δ 15N value of 10.0‰±1.3 (SD) and Neolithic herbivores averaged 6.8‰±1.2 (SD) (Budd et al., Reference Budd, Galik, Alpaslan Roodenberg, Schulting and Lillie2020). In the present study, the non-infant Byzantine individuals (i.e. individuals older than 2.5 years) had a mean value of 11.1‰ (±0.4 SD; 95 per cent CI= [10.9‰, 11.3‰]).

At Kadıkalesi, comparative baselines were drawn from regional sites such as Liman Tepe’s (Izmir) Bronze Age charred seeds with a mean δ 15N value of 2.6‰ (Maltas et al., Reference Maltas, Şahoğlu, Erkanal and Tuncel2022; SI) and Byzantine Mitilini’s (Lesvos) domesticated animals remains with a mean δ 15N value of 5.3‰ (Garvie-Lok, Reference Garvie-Lok2001). Kadıkalesi showed a mean δ 15N value of 9.1‰ (±1 SD; 95 per cent CI = [8.70‰, 9.58‰]).

In summary, the δ 13C baseline human values for prehistoric groups are similar, averaging around –20.0‰ in the Kadıkalesi region and –19.5‰ for earlier phases at Barcın Höyük. In contrast, the δ 15N values for the sampled prehistoric herbivores show greater regional variation, with those from Barcın Höyük averaging approximately 6.8‰, and those near Kadıkalesi yielding values about half a trophic level lower, at around 5.3‰. However, the results may not capture the dietary diversity of the two communities.

The seven samples selected for deeper aDNA sequencing at Barcın Höyük exhibited a median average read length of seventy-two base pairs (bp), and all showed characteristic postmortem damage patterns with terminal nucleotide misincorporation rates exceeding ten per cent, confirming aDNA authenticity (see Table S4). Mitochondrial DNA-based analyses further confirmed the authenticity of the data, with no evidence of contamination detected. These results indicate that the selected individuals provide a reliable basis for genome-wide and uniparental marker analyses.

Barcın Höyük results

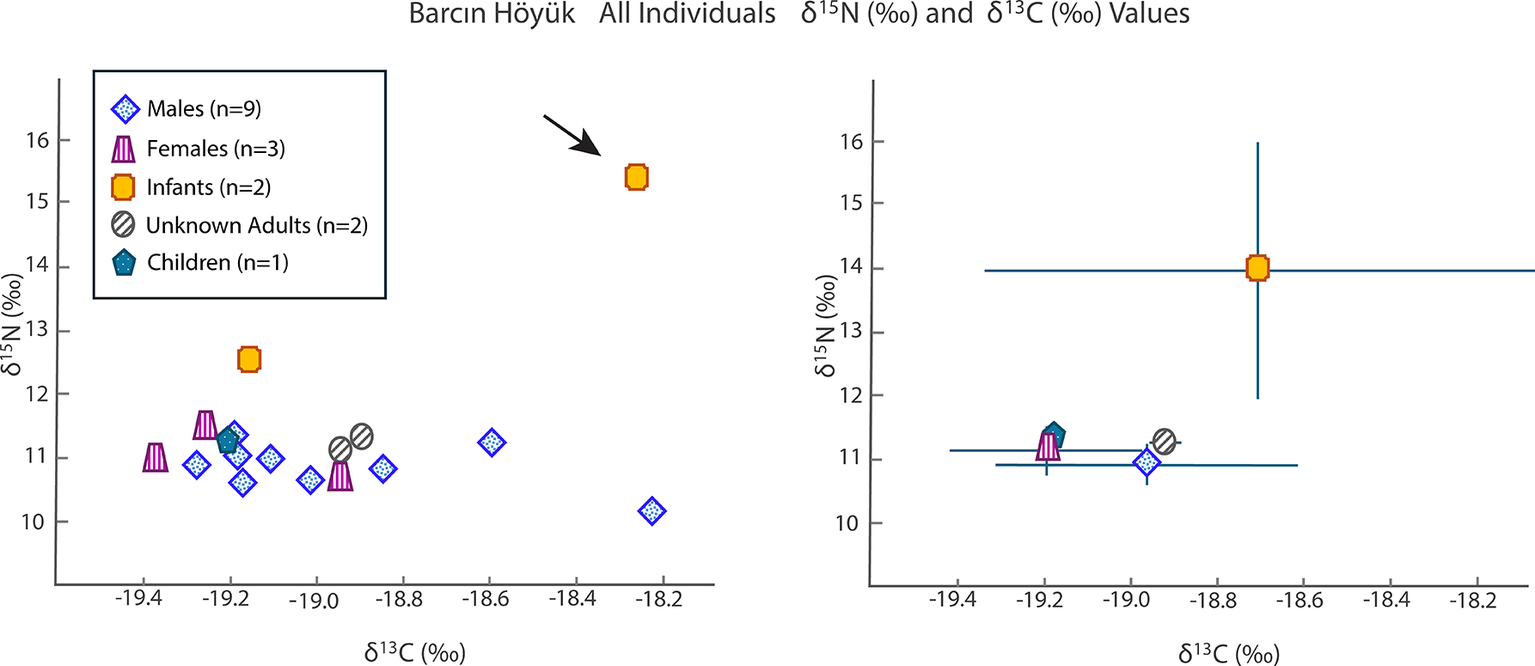

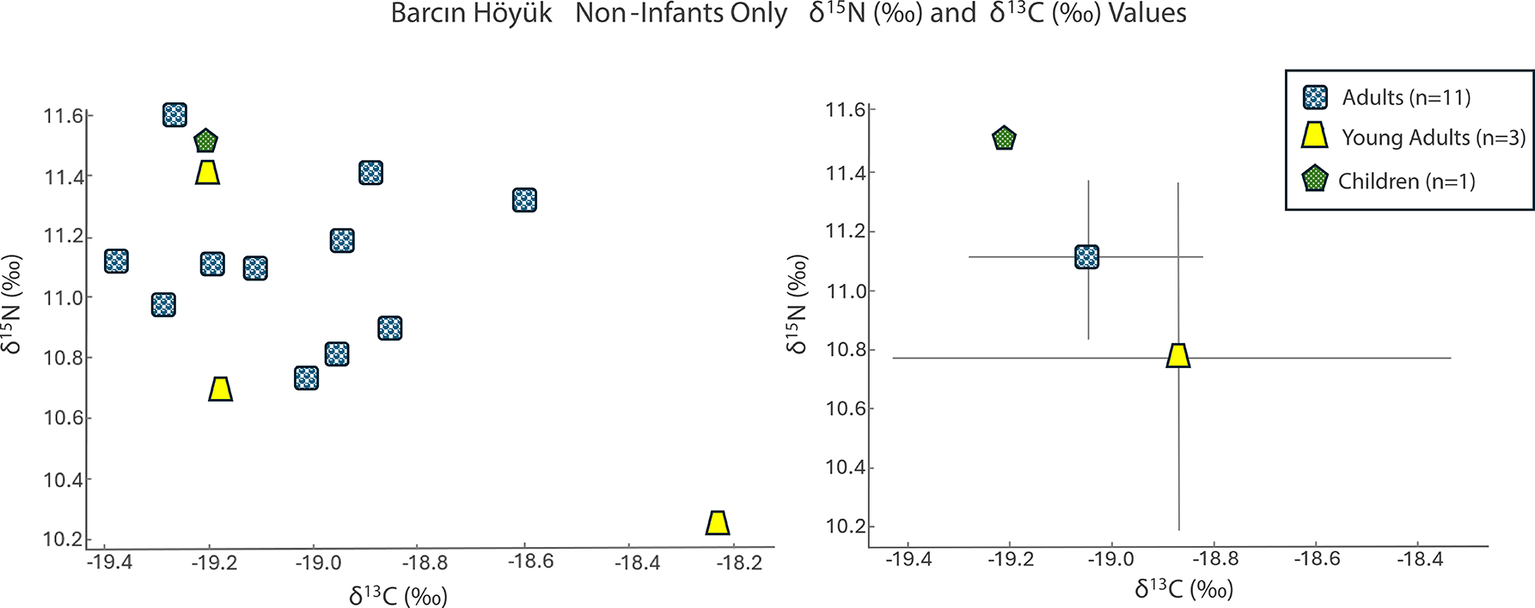

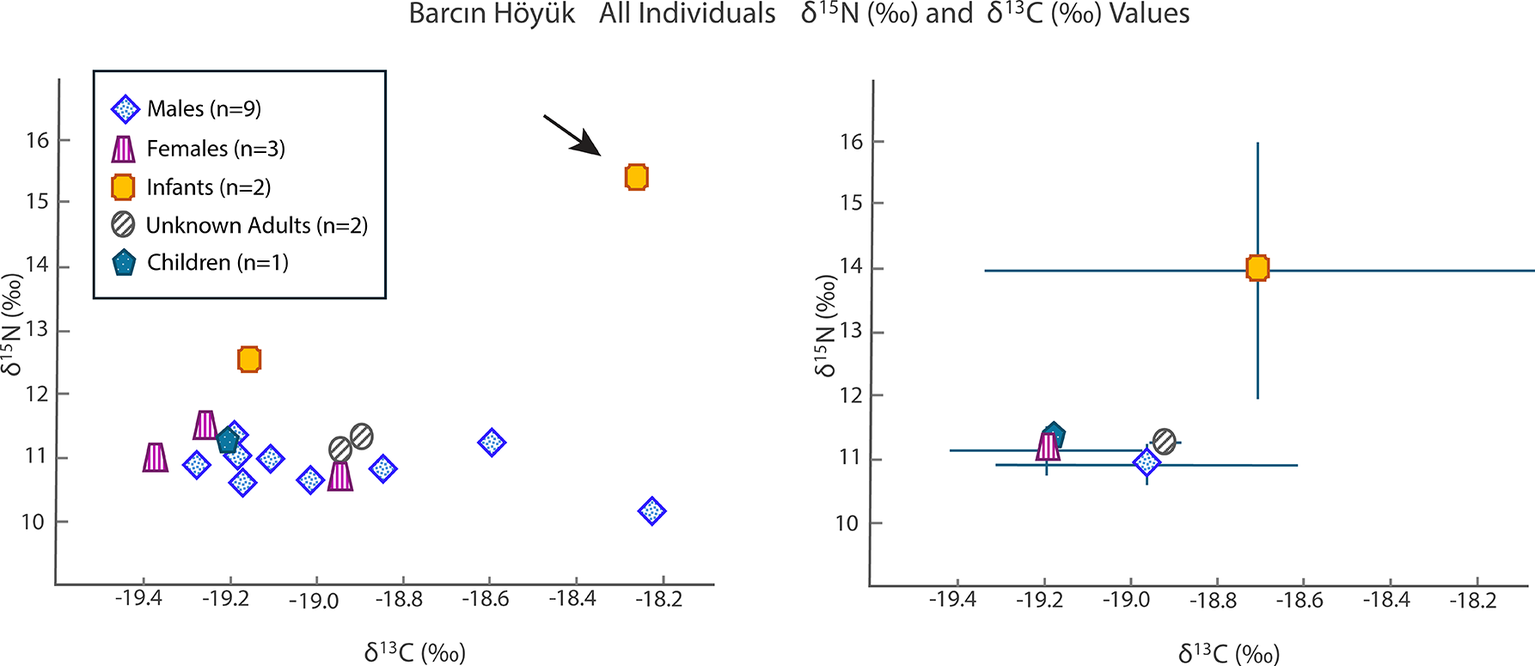

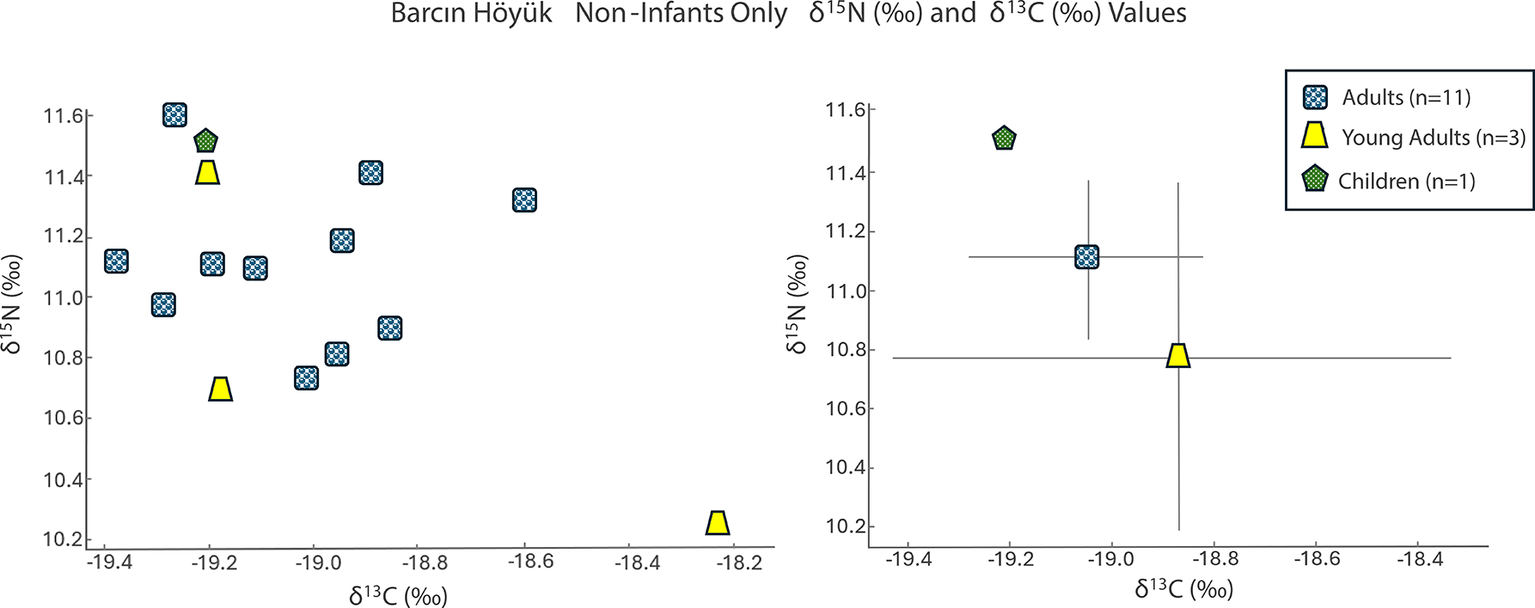

The Barcın Höyük adults and one child (age 3.5–4.5 years) had δ 15N values averaging 11.1‰ (95 per cent CI = [10.9‰, 11.3‰]) and δ 13C values of –19.0‰ (95 per cent CI = [–19.2‰, 18.9‰]) (Figure 2; Table S2). Two infants (i.e. younger than 2.5 years old based on dental development) display higher δ 15N values (15.6‰ and 12.6‰) and δ 13C values (–18.3‰ and –19.2‰). Notably, the child aged 3.5–4.5 years had δ 13C and δ 15N values (–19.3‰ and 11.0‰) indistinguishable from those of the adults.

Figure 2. Values of δ15N (‰) and δ13C (‰) for Barcın Höyük grouped by category as a scatter plot (left) and an error bar graph using a ±1 standard deviation value (right).

The sex determination of the adult individuals was complicated by preservation issues. One individual (BH_L12_22) initially identified as male based on skeletal analyses was found to be genetically female. Overall, the non-infant isotopic values were tightly clustered.

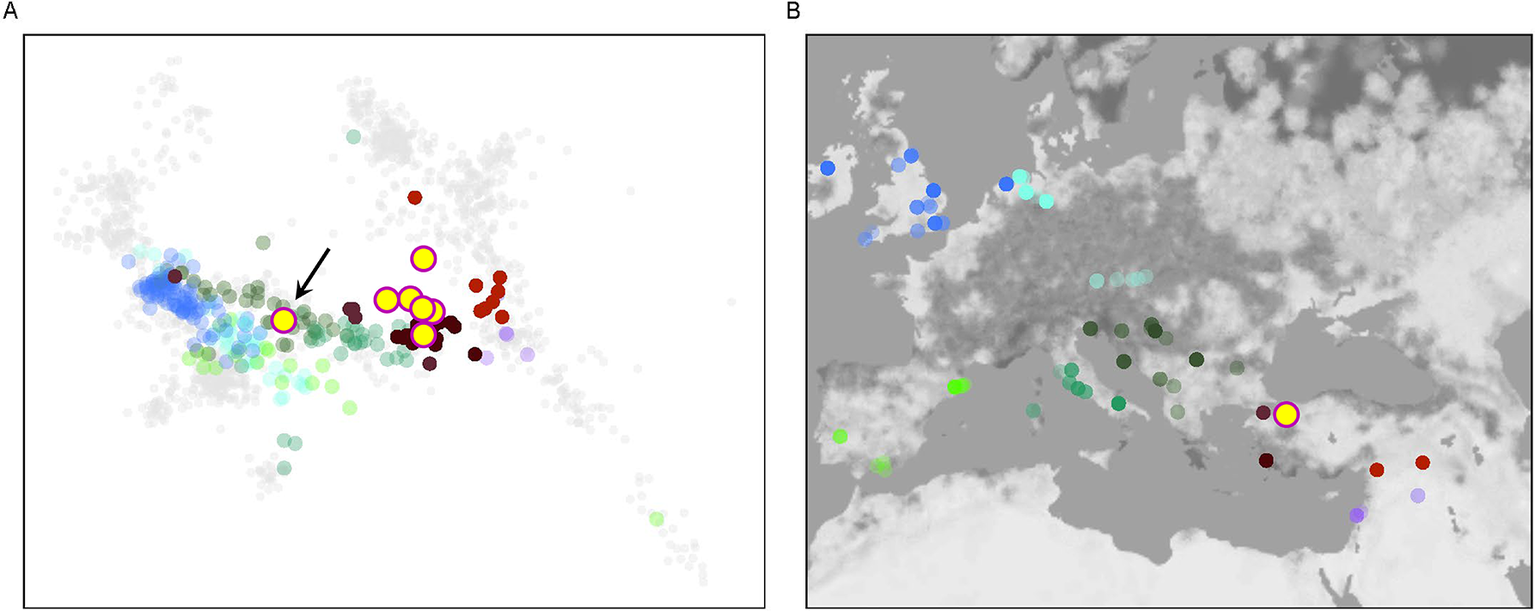

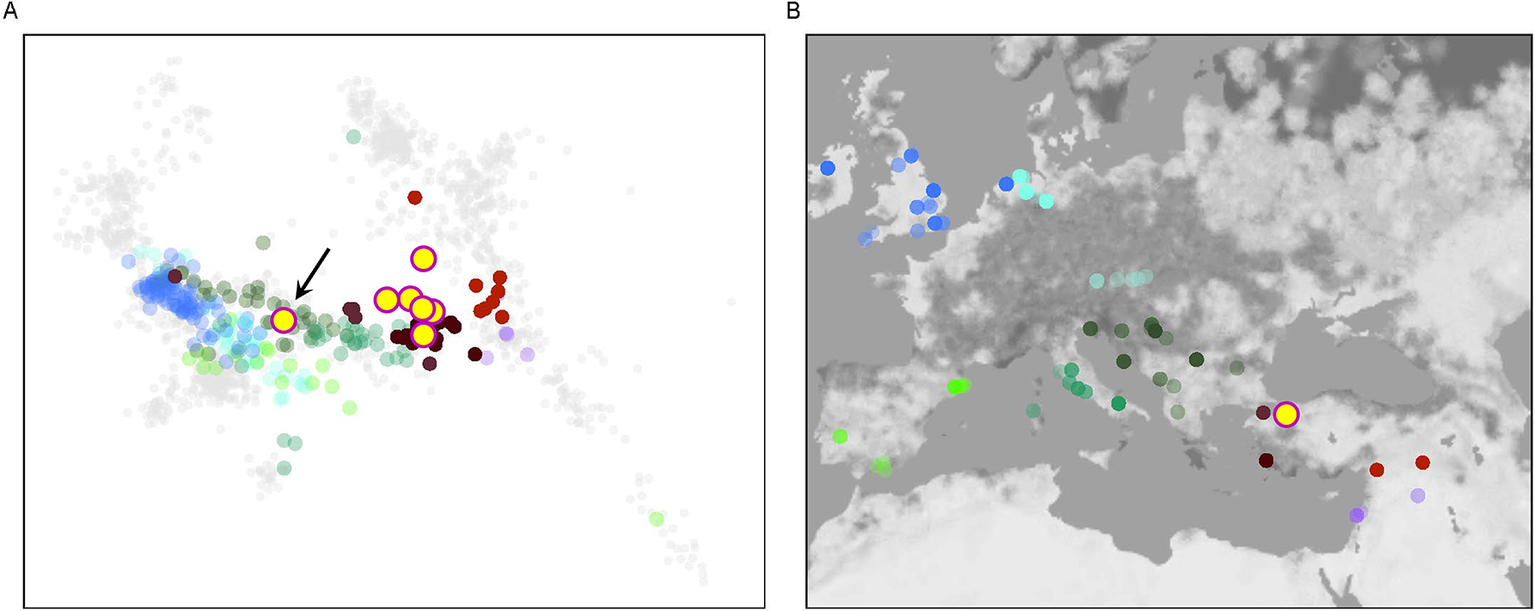

A principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that six out of seven Barcın Höyük individuals showed genome-wide similarity with published genomes from north-western and western Anatolia, including those from Ilıpınar and İznik (Lazaridis et al., Reference Lazaridis, Alpaslan Roodenberg, Acar, Açıkkol, Agelarakis and Aghikyan2022) (Figure 3). The exception was the male individual L10_025, whose genomic profile aligned with published profiles from south-eastern European populations of the late first millennium bc and the first millennium ad, particularly from Hellenistic Macedonia and Late Antique Bulgaria. His uniparental markers further support this profile: he carried Y-DNA haplogroup T1a1a1a1a and mtDNA haplogroup U5a1b1c1. The authenticity of the data is well supported, with zero mitochondrial contamination (Schmutzi estimate = 0.00) and high genome coverage (1.18× nuclear; 92× mitochondrial). This individual (BH_L10_025) has been directly radiocarbon dated to the eighth/ninth century bc (Lab-code: TÜBİTAK-1416; 1217±24 bp: ad 706–736 (9.1 per cent probability) or ad 772–885 (86.3 per cent probability), calibrated in IntCal20).

Figure 3. A: PCA plot placing Barcın Höyük individuals within a broader dataset of previously published ancient genomes. B: The location of these individuals with ancient DNA data. The PCA, based on genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism data, indicates that the Barcın individuals mostly cluster with Anatolian populations. One individual (indicated with black arrow in A), however, plots closer to Balkan populations.

Despite this individual’s genetic distinctiveness, his δ 13C value of –18.6‰ and δ 15N value of 11.3‰ were both within the range observed for the broader Barcın community (δ 13C: –19.4 to –18.6‰; δ 15N: 10.2 to 11.6‰). The remaining six individuals from the Barcın Höyük Byzantine-period cemetery form a homogeneous genetic group. They cluster tightly with other north-western and western Anatolian genomes of the same period and show no genetic affinity to northern or western Europe, the Caucasus, or the Levant (Lazaridis et al., Reference Lazaridis, Alpaslan Roodenberg, Acar, Açıkkol, Agelarakis and Aghikyan2022).

Kadıkalesi results

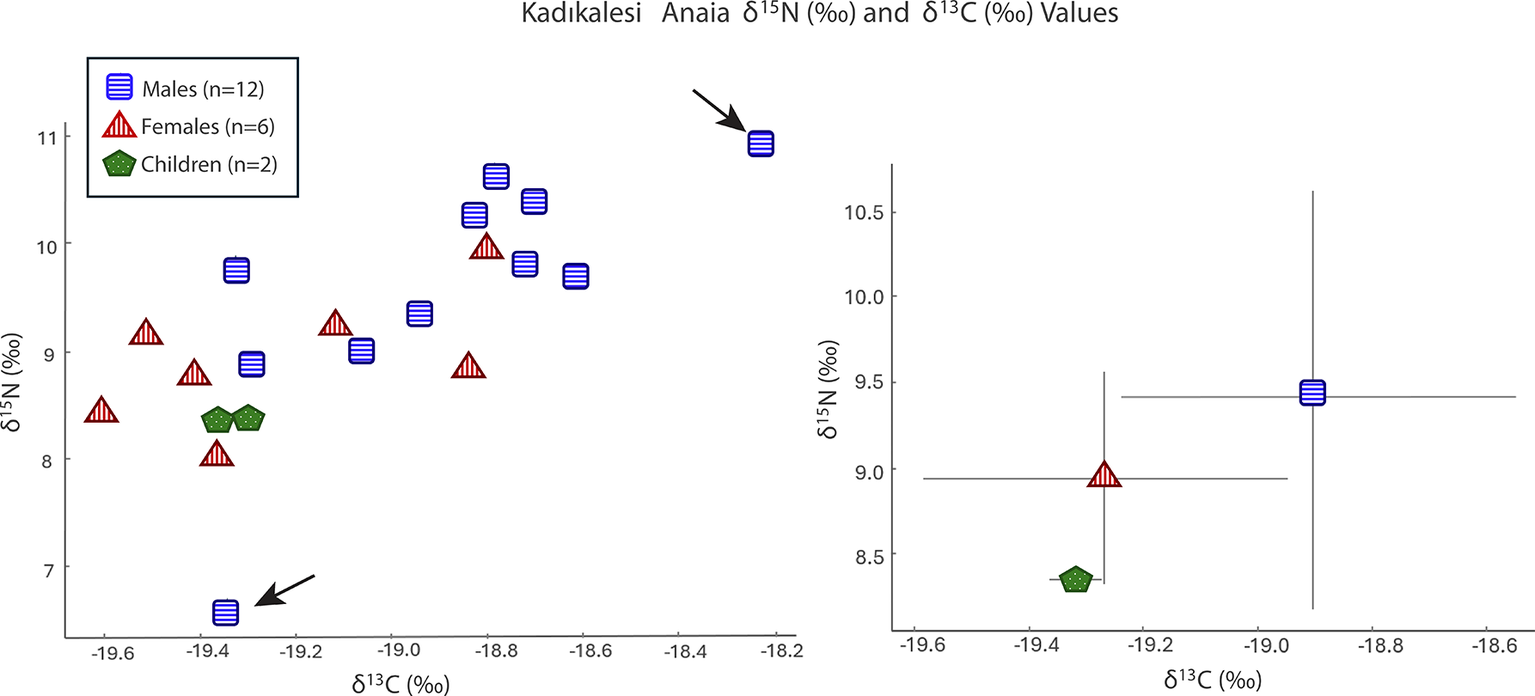

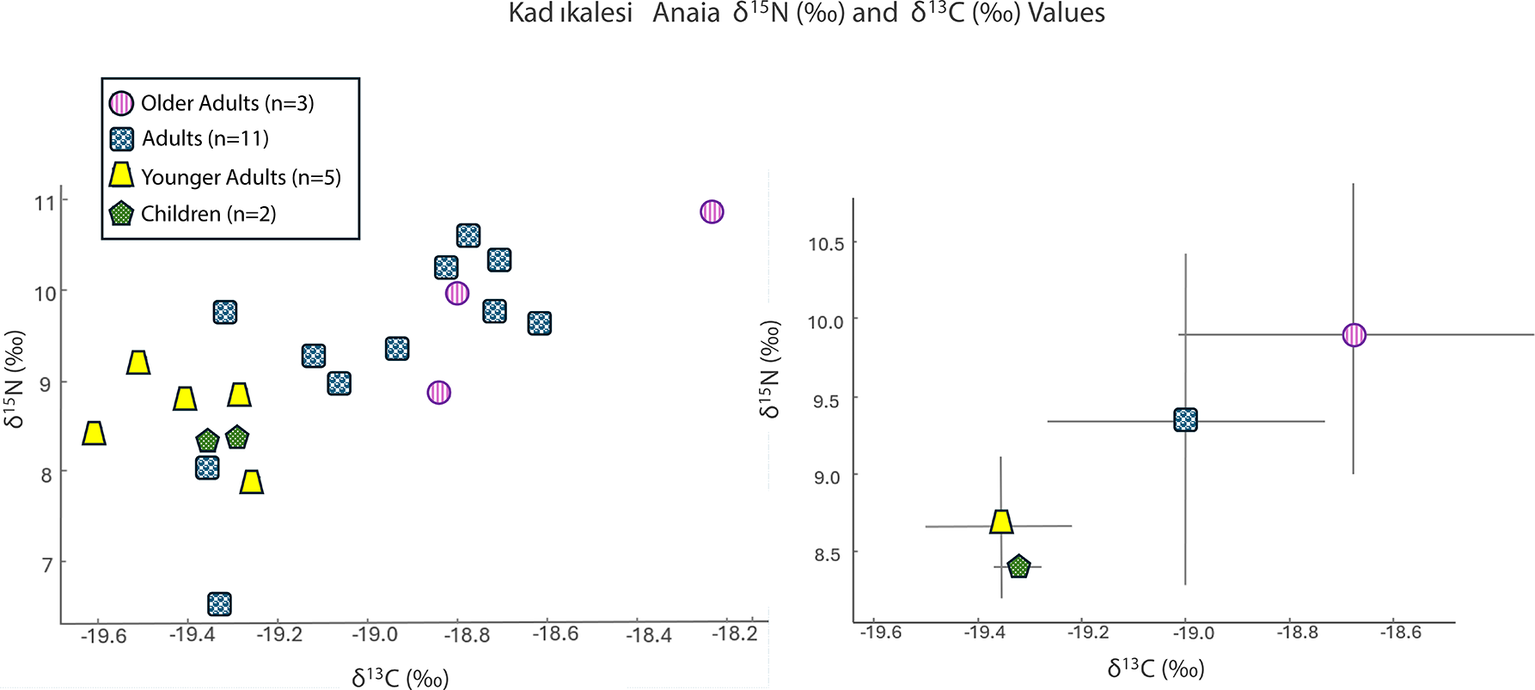

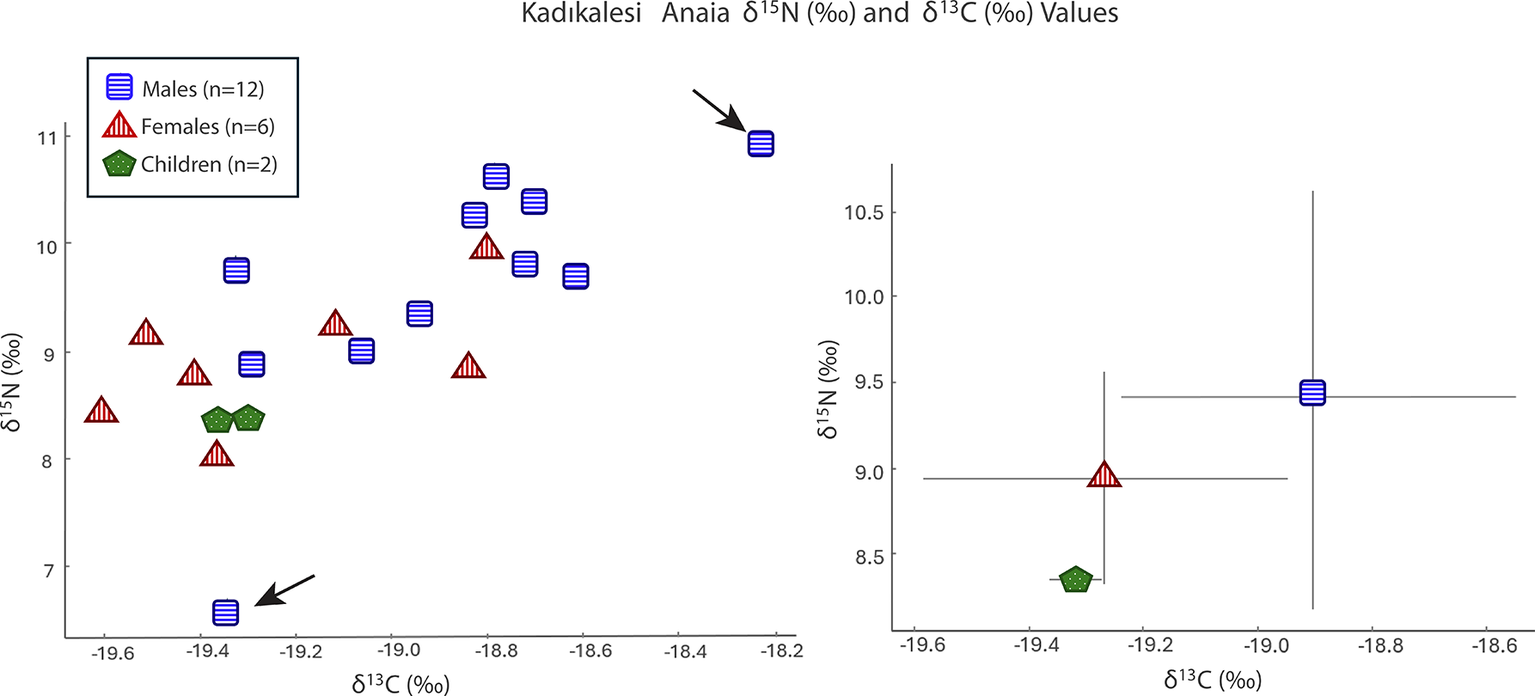

Stable δ 15N and δ 13C isotope ratio analysis for Kadıkalesi shows dietary variability and nutrition insights for the city’s residents including children, females, and males, but not infants. The mean δ 15N value for all Twenty-one individuals was 9.1‰ ± (95 per cent CI = [8.7‰, 9.6‰]), and the mean δ 13C value was –19.1‰ (95 per cent CI = [–19.2‰, –18.9‰]) (Figure 4; Table S2). The δ 15N values range from 6.6‰ to 10.9‰, covering over one trophic level in their difference (Minagawa & Wada, Reference Minagawa and Wada1984), while the δ 13C values vary between –19.6‰ and –18.2‰, with no significant variation in plant resource type.

Figure 4. Values of δ15N (‰) and δ13C (‰) for Kadıkalesi grouped by category as a scatter plot (left) and an error bar graph using a ±1 standard deviation value (right).

The variability in δ 15N stems from two male individuals with distinct isotopic values. One has a δ 15N value of 10.9‰, slightly higher than the settlement mean, and the other shows a δ 15N value of 6.6‰, at the lower end of the observed distribution. The isotopic values of the two children (mean values: δ 13C = –19.4‰±0.07 and δ 15N = 8.4‰±0.07), aged approximately nine and twelve to thirteen years, were tightly clustered at the lower end of the adult δ 15N range, but still fully within the general population profile.

Discussion

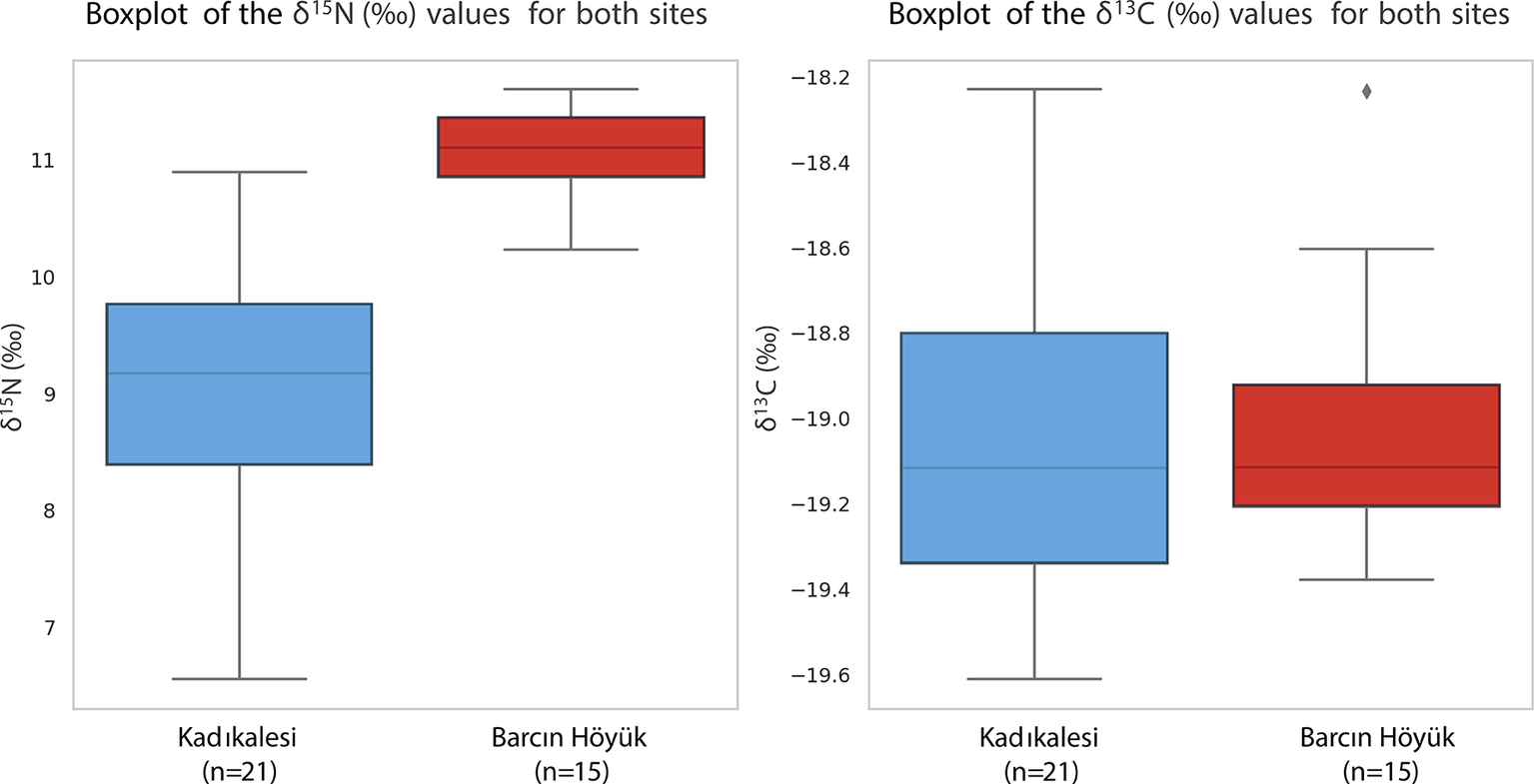

A comparison of δ 15N and δ 13C values for Kadıkalesi and Barcın Höyük reveals several points of contrast as well as areas of similarity. At both sites, the δ 13C values are consistent with a diet dominated by C3 plants, despite the sites being more than 400 km apart and located in distinct environmental zones, one in a coastal and one in an inland agricultural valley. Slightly less negative Byzantine δ 13C values compared to Neolithic levels may indicate reduced water availability for crops or some contribution from C4 plants (Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, De Cupere, Marinova, Van Neer, Waelkens and Richards2012a; Xoplaki et al., Reference Xoplaki, Fleitmann, Luterbacher, Wagner, Haldon and Zorita2016; Sołtysiak & Schutkowski, Reference Sołtysiak and Schutkowski2018; Irvine, Reference Irvine2022: 69).

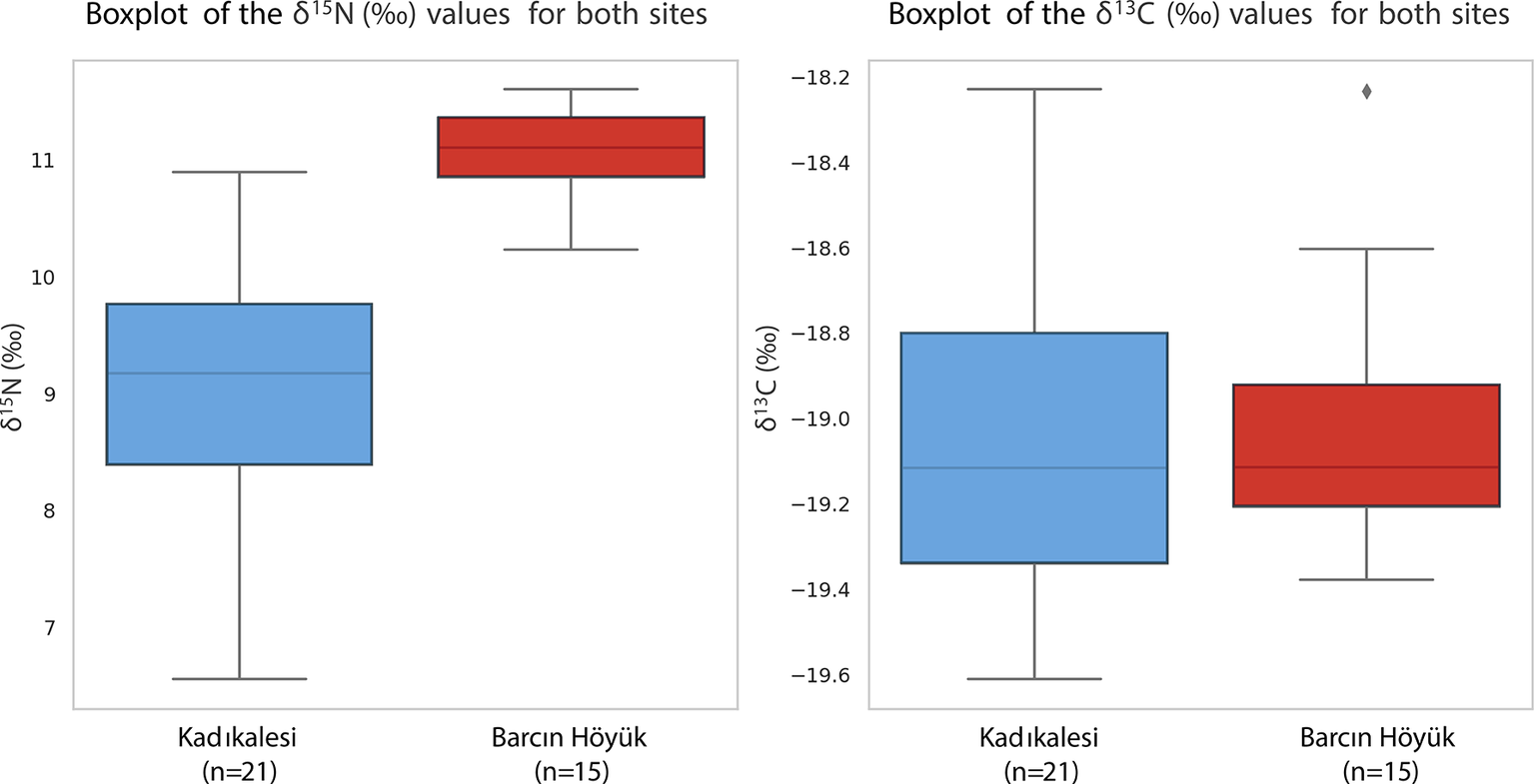

The δ 15N values at Kadıkalesi are more dispersed than those at Barcın Höyük, as illustrated in the boxplot comparison (Figure 5). While the Barcın non-infant data shows isotopic homogeneity with tightly clustered values (SD = 0.36‰), the broader Kadıkalesi spread (SD = 1.03‰) suggests greater dietary variability, possibly reflecting more diverse protein sources in a coastal setting. This is consistent with the δ 15N range at Kadıkalesi spanning over one trophic level, with some individuals showing higher values that could indicate greater reliance on animal or marine protein, and others showing lower values suggestive of minimal animal protein consumption. Barcın’s restricted range of δ 15N values suggests uniform dietary habits in a small cohesive rural community with shared subsistence strategies, with people eating similar amounts and types of terrestrial protein and plant products. At Kadıkalesi, involvement in regional exchange networks is likely to have led to varied dietary habits, indicating social or economic differences, with some individuals having better access to high-trophic-level foods such as fish, animal proteins, or perhaps other elite-controlled resources.

Figure 5. Boxplot comparing δ15N (left) and δ13C (right) values for non-infants at Barcın Höyük (BH) and all individuals at Kadıkalesi (KK). Error boxes show dispersion, not ninety-five per cent CI.

Beyond addressing dispersed patterns, the analysis of δ 13C values by sex at Barcın Höyük indicates only subtle dietary differences. As the data did not meet the required parameters, a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test for small, unevenly distributed groups was used to assess differences in δ 13C values by sex and age. The comparison by sex did not yield statistically significant results (p = 0.229; 95 per cent CI for the mean difference = [–0.20‰, +0.66‰]). The actual difference in group means is modest for δ 13C values: females averaged –19.2‰ (±0.2 SD; 95 per cent CI = [–19.4, –19.1]) and males –19.0‰ (±0.4 SD; 95 per cent CI = [–19.3, –18.7]), with a mean difference of only 0.2 per cent and overlapping confidence intervals. This small effect size suggests broadly similar dietary habits between the sexes. Such homogeneity in non-infant δ 13C and δ 15N values is likely to reflect shared access to food resources and protein intake, with no isotopically visible evidence for sex-based dietary inequality in this rural Byzantine community.

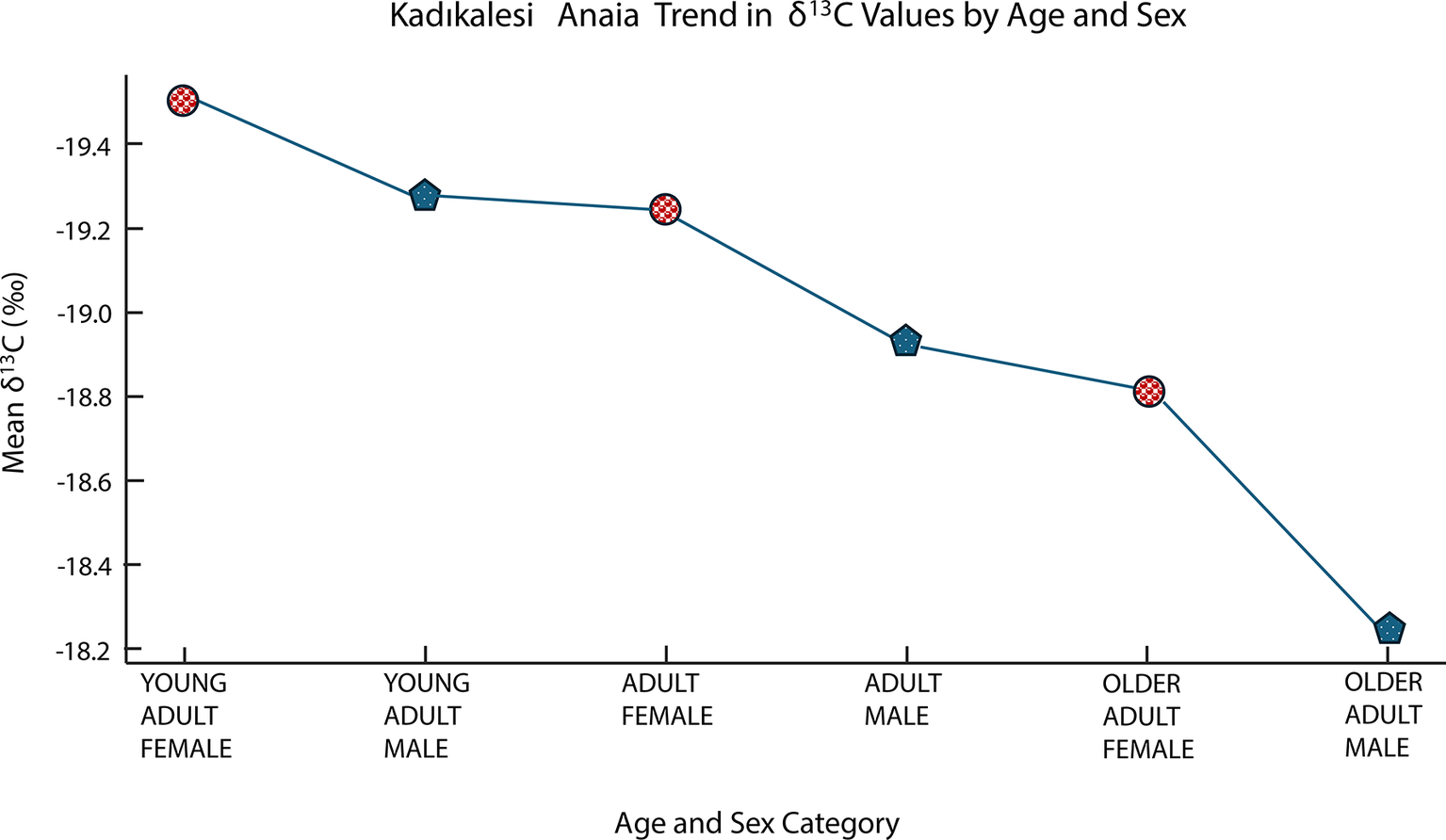

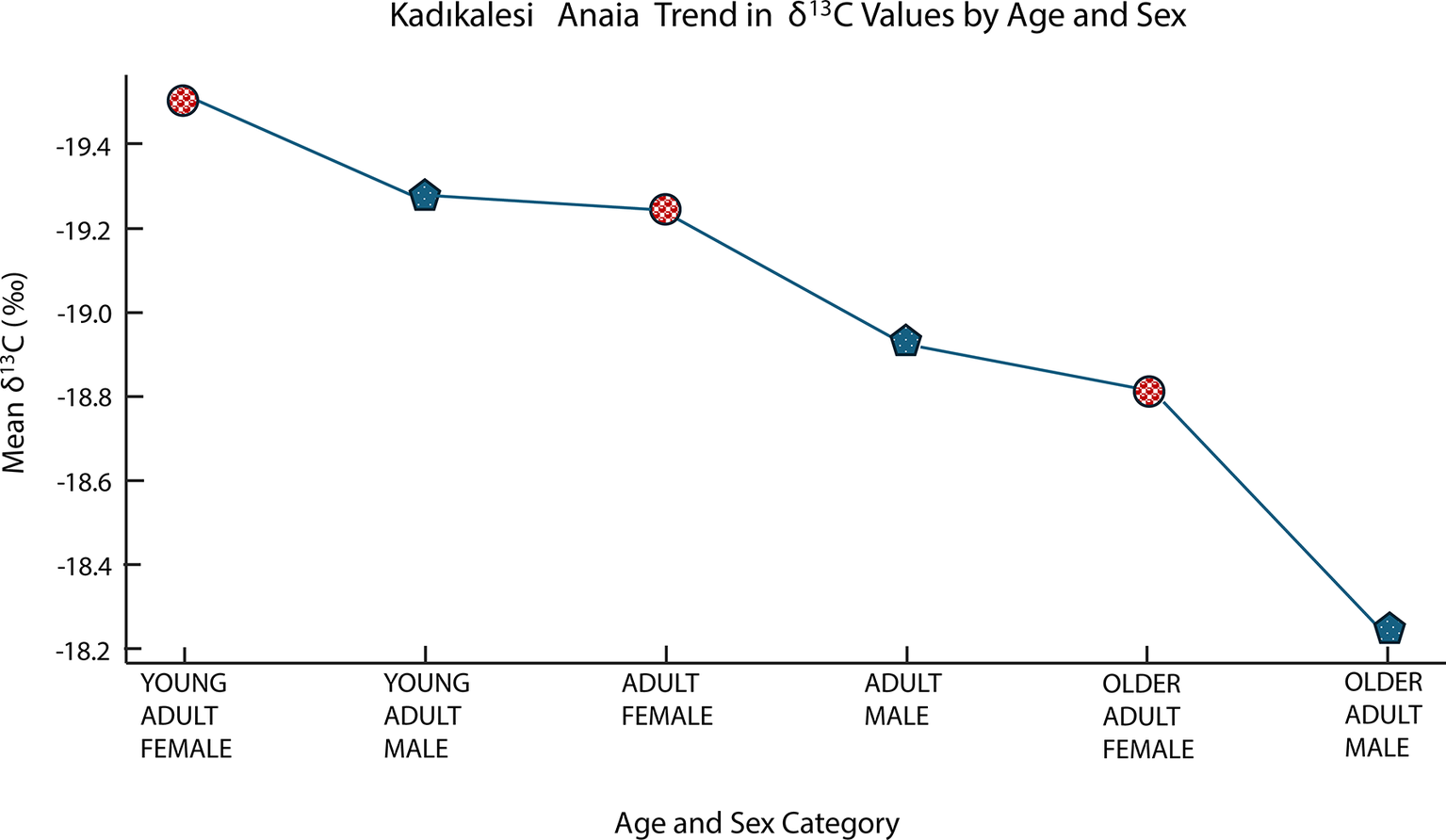

For Kadıkalesi, males have a mean δ 13C value of –18.9‰ and females –19.2‰, a difference of just over 0.3‰. This is a small offset within the range of expected dietary variation alone. A Kruskal–Wallis test indicates that the difference is unlikely to be entirely due to random variation (p = 0.035; 95 per cent CI = [0.003, 0.62]) although the effect size is modest. When adults from both sites are considered together, the male–female difference is 0.28‰; ninety-five per cent CI = [0.06, 0.51], with a Kruskal–Wallis p-value of 0.022. Given the substantial overlap in confidence interval values between groups, with a mean difference for males vs females of +0.47‰ (95 per cent CI = –0.56‰ to +1.49‰), this pattern should be viewed as a slight tendency rather than a strong separation. It may reflect minor differences in food access or preparation rather than any pronounced divergence in dietary resources. When taken together with anthropological data, as discussed for the general period by Tritsaroli (Reference Tritsaroli and Germanidou2022), this slight difference may suggest varied dietary habits over the life course for men and women for some sites. Children at both sites have intermediate δ 13C values, with male values being consistently more positive.

These slight differences between the two sites might be explained by their urban and rural contexts. Dietary differences between men and women in Byzantine urban society were influenced by social conventions that often restricted access to food (Garnsey, Reference Garnsey1999; Tritsaroli, Reference Tritsaroli and Germanidou2022). Donahue (Reference Donahue2015: 242) emphasizes ‘female moderation in eating’, and Tritsaroli (Reference Tritsaroli and Germanidou2022: 138) reports greater physiological stress in women through linear enamel hypoplasia. Tritsaroli (Reference Tritsaroli and Germanidou2022: 145) alsoreports that these differences are likely to be more marked in urban than in rural contexts, which reflects the patterns seen here.

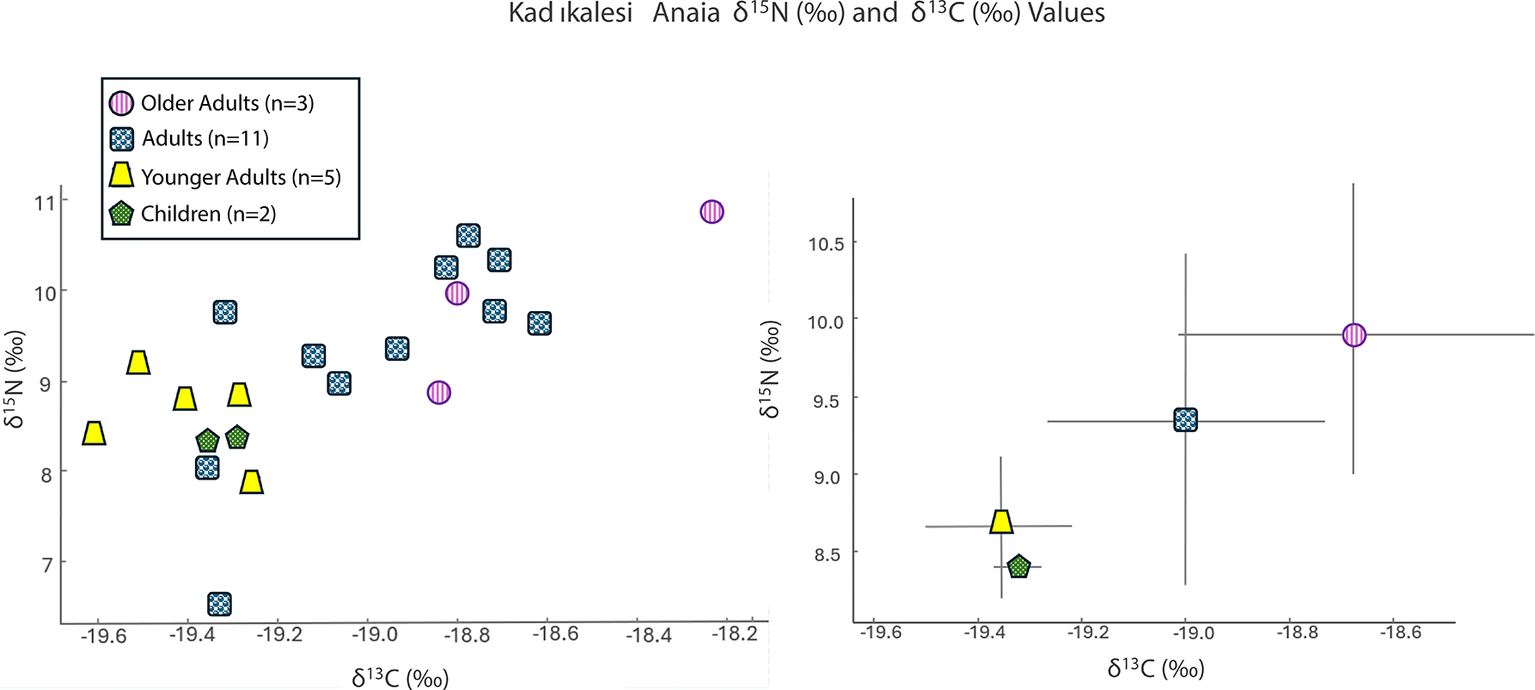

Examining age differences gave worthwhile results in relation to children. The Kruskal–Wallis test to compare age groups at Kadıkalesi (children: 2.5–15 years; young adults: 15–30 years; adults: 30–45 years; and older adults: 45+ years) shows a slight statistically significant difference in mean δ 13C values (p = 0.023), indicating varied dietary habits over the life course (Figure 6). Pairwise comparisons using Welch’s t-based confidence intervals showed that adults (n = 11) had significantly higher δ 13C values than children (n = 2; mean difference = 0.4‰, 95 per cent CI = [0.1, 0.5]) and young adults (n = 5; mean difference = 0.4‰, 95 per cent CI = [0.2, 0.7]).

Figure 6. Values of δ15N (‰) and δ13C (‰) for Kadıkalesi grouped by age as a scatter plot (left) and an error bar graph using standard deviation (right).

When it comes to δ 15N, on the other hand, with the exception of two Barcın Höyük infants with elevated values consistent with breastfeeding (Schurr, Reference Schurr1998; Beaumont et al., Reference Beaumont, Montgomery, Buckberry and Jay2015), or physiological stress (Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, Fuller, Sage, Harris, O’Connell and Hedges2005), the Barcın child aged 3.5–4.5 years yielded values indistinguishable from those of the adults, indicating post-weaning convergence in diet. At Kadıkalesi too, the two children analysed aged 9 and 12–13 years likewise have adult-like δ 15N values, suggesting dietary convergence by late childhood, although the small sample sizes limit broader inference. Other comparisons yielded no statistically significant differences, with substantial overlap in confidence intervals across groups.

When adults are considered, the δ 13C values exhibited a gradual increase across age and sex categories, ranging from –19.51‰ in young adult females (n = 3) to –18.23‰ in the one older adult male (Figure 7). This pattern may suggest incremental shifts in dietary carbon sources over the life course and between sexes, although further data are required to confirm the robustness of this trend. It may be surmised that different age groups had access to different food resources. Conversely, Barcın Höyük shows no significant difference by age (p = 0.620), suggesting more homogeneous rural dietary habits across all ages (Figure 8) perhaps because of stricter dietary and food provisioning practices than in urban contexts, as a result of differences in social organization and age-related cultural norms.

Figure 7. Mean δ13C values across age and sex categories at Kadıkalesi showing variation by age and sex (Young Adult Female n = 3; Young Adult Male n = 2; Medium Adult Female n = 2; Medium Adult Male n = 9; Older Adult Female n = 2; Older Adult Male n = 1).

Figure 8. Values of δ15N (‰) and δ13C (‰) for Barcın Höyük grouped by age as a scatter plot (left) and an error bar graph using a ±1 standard deviation value (right).

The δ 15N values show notable differences between Barcın Höyük and Kadıkalesi. The mean δ 15N value for non-infants at Barcın Höyük is 11.1‰±0.4, while the Kadıkalesi mean is 9.1‰±1.0, revealing a 2‰ difference. This disparity, as discussed, may be due to the divergence seen in local isoscape baselines in each area (Barcın: 6.8‰ and Kadıkalesi: 5.3‰, based on prehistoric herbivores; Garvie-Lok, Reference Garvie-Lok2001; Budd et al., Reference Budd, Galik, Alpaslan Roodenberg, Schulting and Lillie2020). Higher δ 15N in Barcın relative to its faunal baseline suggests a notable shift in protein sources compared to earlier periods, paralleling broader Eastern Mediterranean trends toward elevated δ 15N in the Byzantine era (Irvine, Reference Irvine2022).

The combined data from our two sites yielded two significant anomalies. First, there is a notable difference in δ 15N values compared to the stable δ 13C values across the sites. Kadıkalesi Anaia displayed higher variation, while the non-infant inhabitants of Barcın Höyük showed tightly clustered δ 15N values. This suggests limited dietary choices in rural Barcın Höyük versus diverse options in coastal/cosmopolitan Kadıkalesi Anaia.

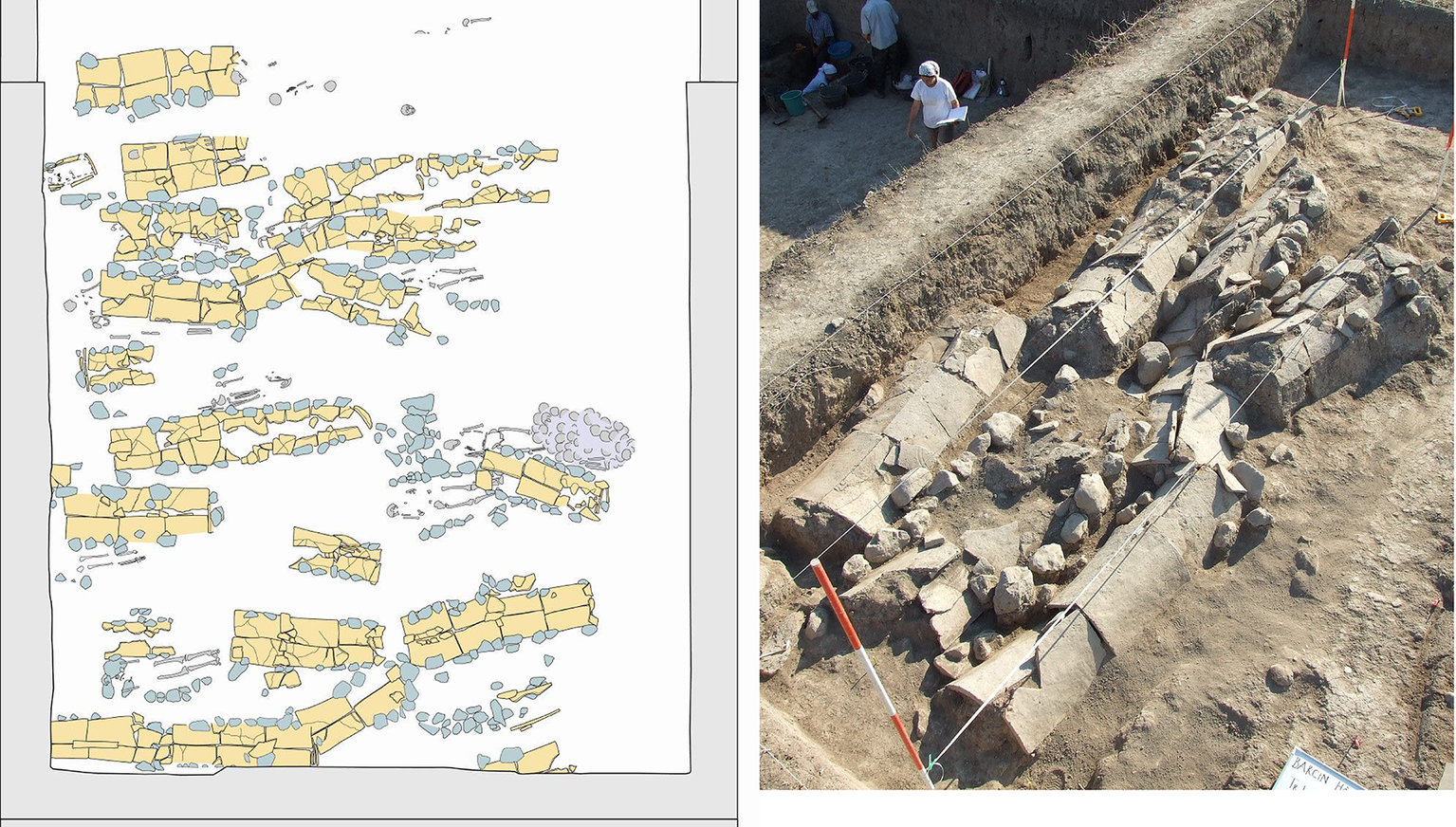

Although a village with presumably less varied food options, Barcın Höyük had one adult male (BH_L10_19) aged 20–25 with the highest δ 13C value at –18.2‰ (z = 2.75) and the lowest δ 15N value at 10.2‰ (z = –2.39). The tight clustering of the other individuals contributes to a small standard deviation. No high-coverage genome-wide sequencing data is available for this person, who, when compared with the non-infant Barcın population, lies two standard deviations above the mean, potentially suggesting a separate role within society (see Figure 3). Despite his unusual isotopic values suggestive of different dietary habits, his burial had no special characteristics or grave goods, as is the norm, although burial gifts are not completely absent in the cemetery. As is typical, three pairs of rooftiles were placed to form a gabled roof over his grave (a type known as kalyvitis) (Figure 9). The findings indicate he either came from a region with slightly different dietary stable isotope values or that he followed a different dietary regime than others at Barcın. This may contradict Tritsaroli’s (Reference Tritsaroli and Germanidou2022) argument that rural areas have fewer intra-settlement asymmetries. It would be interesting to determine if he were of non-local origin using strontium isotope analysis or genetics.

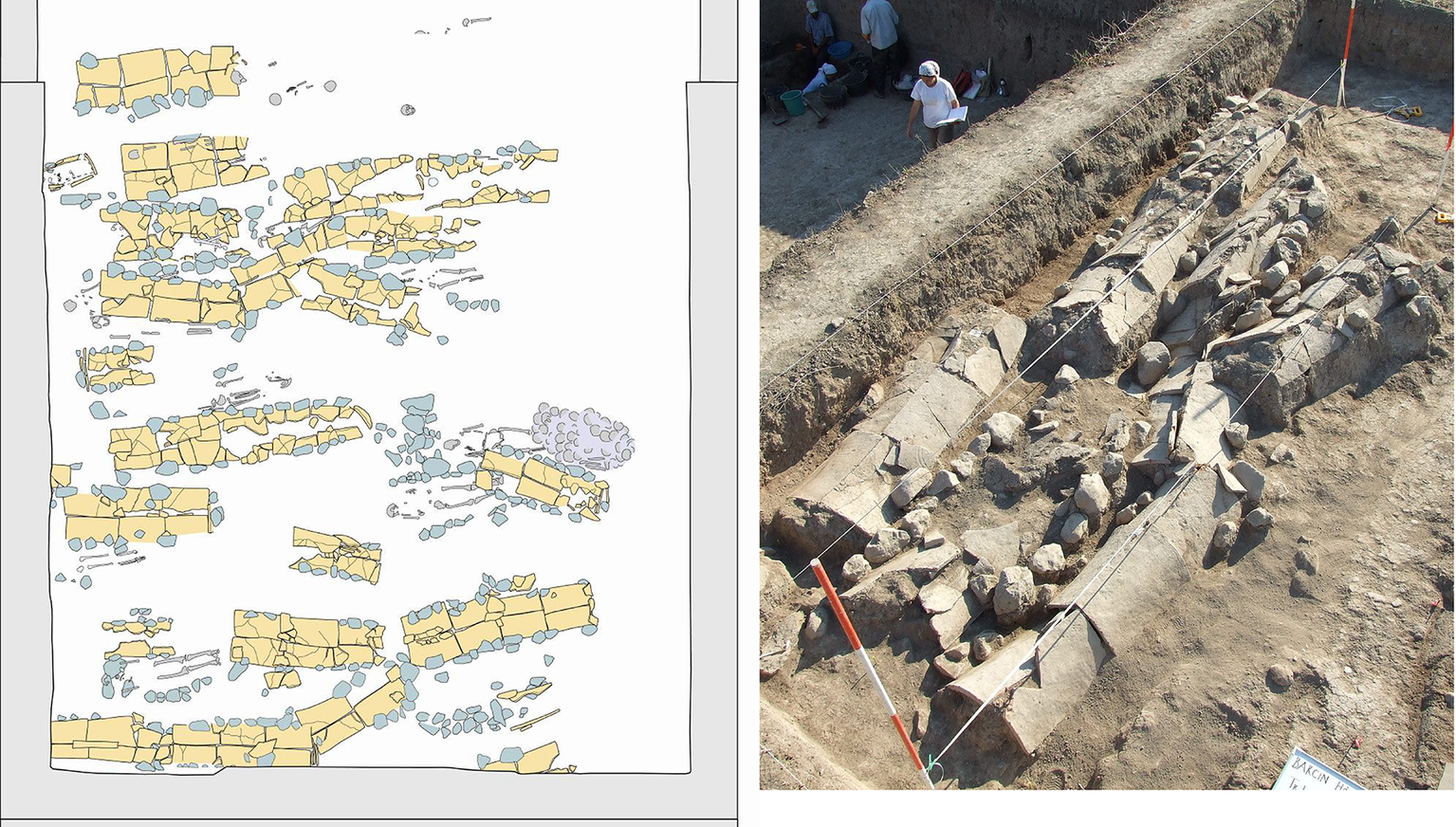

Figure 9. Plan and photograph of part of the Barcın cemetery (Barcın Höyük excavation archives).

The individual at Barcın Höyük (c. 40 years old), with a genetic ancestry related to south-eastern Europe (BH_L10_025), has a δ 13C value of 18.6‰ (z = 1.46) and a δ 15N value of 11.3‰ (z = 0.72), which fall within the expected range for the site. Although not an outlier, he has higher δ 13C and δ 15N values, suggesting slight differences in dietary habits possibly due to age and sex. Nonetheless, this individual appears to have had similar access to local food resources as other local inhabitants. This is consistent with the idea that incomers to the region could be fully integrated into local provisioning systems and may reflect the uniformity of food source availability within the Byzantine agrarian system (Haldon, Reference Haldon1979).

Kadıkalesi’s cosmopolitan port town included international residents such as Italian traders (Jacoby, Reference Jacoby, Berger, Mariev, Prinzing and Riehle2016: 56), members of the nobility (Mercangöz, Reference Mercangöz2005: 212), and clergymen, such as monks, adhering to strict Byzantine fasting regimes (Talbot, Reference Talbot and Talbot1987: 231). This diversity may have influenced the variation in δ 15N values, reflecting different dietary practices. One male individual (2015V33M6-1) had a δ 15N value of 6.6‰ (z = –2.56), more than two standard deviations below the mean, indicating either stringent fasting as part of an ascetic lifestyle, or limited access to animal proteins due to social, religious, or economic factors.

Another male from Kadıkalesi (2016E14M3-1) lies more than a full standard deviation above the mean with a z score of +1.74 and a δ 15N value of 10.9‰, and the highest δ 13C value at –18.2‰, at least two standard deviations above the mean with a z score of +2.43. A high δ 13C value in combination with a high δ 15N value is often linked to marine resource consumption (Schoeninger & DeNiro, Reference Schoeninger and DeNiro1984; Richards & Hedges, Reference Richards and Hedges1999; Milner et al., Reference Milner, Craig, Bailey, Pedersen and Andersen2004), although C4 plants or drier climatic conditions could also produce this pattern. In the Aegean, isotopic values of fish overlap with terrestrial fauna (Vika & Theodoropoulou, Reference Vika and Theodoropoulou2012), complicating interpretations, but the presence of fish remains among the zooarchaeological data from Kadıkalesi supports possible marine input (Onar et al., Reference Onar, Mercangöz, Kutbay and Tok2013: 84).

Integrated genetic and isotopic evidence

At Barcın Höyük, the single genetic outlier with affinities to populations in the Balkans exhibited δ13C (–18.6‰) and δ15N (11.3‰) values within the local range for adults (δ13C: –19.9‰ to –18.2‰; δ15N: 10.9–11.1‰), indicating dietary integration into local patterns despite differing ancestry, indicating rapid dietary assimilation. Thus, ancestry—potentially reflecting Byzantine military resettlement (stratiotika ktemata) and population movement under imperial policy—is likely to have had little impact on diet among our samples. The data can be compared to cases such as Worth Matravers in early medieval Britain, where δ 13C and δ 15N isotope values showed that one individual with West African ancestry had the same diet as the rest of the community (Foody et al., Reference Foody, Dulias, Justeau, Ditchfield, Ladle and Gretzinger2025). This observed pattern of adopting local dietary practices appears to contrast with Roman and Late Antique cases such as in Southwark, London (Redfern et al., Reference Redfern, Gröcke, Millard, Ridgeway, Johnson and Hefner2016), and San Martino in Trento, Italy (Tafuri et al., Reference Tafuri, Goude and Manzi2018). In both cases migrant populations continued to yield distinctive isotopic signatures for at least one generation, suggesting slower dietary convergence and the persistence of original foodways.

The absence of dietary differences by ancestry in the one case documented at Barcın is likely to reflect both social incorporation into existing provisioning systems and the realities of a small rural settlement. With a restricted agricultural base focused on C₃ cereals, pulses, and locally raised livestock and minimal market access, residents had little opportunity to maintain distinct dietary traditions. Instead, cultural norms and local economic structures probably determined their diet.

Conclusion

The integration of the bulk bone collagen stable isotope data from thirty-eight individuals with the aDNA data evidence here offer a valuable multiproxy view into dietary practices, food access, social organization, economic structure, mobility, and social organization in two contrasting Byzantine communities. Despite differences in scale, environmental setting, and connectivity, both sites show diets dominated by terrestrial C3 plants and animals, yet the degree of dietary variation differs sharply. Kadıkalesi, a cosmopolitan port embedded in larger trade networks, shows greater isotopic variability in δ 13C and δ 15N values, consistent with a more diverse dietary base, and evidence for social differentiation, both between sexes and across age groups. Conversely, Barcın Höyük, located in a rural agricultural zone, exhibits low variability in both δ 13C and δ 15N, indicating equal food access in a tight-knit or cohesive community. Byzantine records show a grain and dairy-heavy dietary repertoire with infrequent meat consumption and regional variation in marine resources (Van Neer & Waelkens, Reference Van Neer, Waelkens, Postgate and Thomas1998; Vroom, Reference Vroom2000; Bourbou et al., Reference Bourbou, Fuller, Garvie-Lok and Richards2011: 577; Gregoricka & Sheridan, Reference Gregoricka and Sheridan2013). Fish became more integral to the Byzantine menu due to advancements in fishing techniques and stricter fasting protocols, yet seafood remained a relatively scarce, though valued, resource (Bourbou et al., Reference Bourbou, Fuller, Garvie-Lok and Richards2011; Garvie-Lok, Reference Garvie-Lok2001: 2). At Kadıkalesi, the isotopic values do not provide strong evidence for regular fish consumption. The only possible exception is one male individual with high δ 13C and δ 15N values. This apparent absence of a clear signal may also reflect regional isotopic baselines, as values from the warm Aegean Sea may differ from those documented for cold-water fish (Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, Müldner, Van Neer, Ervynck and Richards2012b; Vika & Theodoropoulou, Reference Vika and Theodoropoulou2012; Guiry, Reference Guiry2019).

The aDNA evidence from Barcın Höyük complements these isotopic patterns, showing most individuals had genome-wide links to north-western Anatolian Byzantine populations, reflecting long-term demographic stability (Lazaridis et al., Reference Lazaridis, Alpaslan Roodenberg, Acar, Açıkkol, Agelarakis and Aghikyan2022). In contrast, the one male individual with affinities to south-eastern European populations presented δ 13C and δ 15N values within the local range, indicating dietary assimilation despite non-local ancestry. Thus mobility (which may also have occurred in previous generations) did not necessarily correspond with distinct dietary habits, with newcomers likely to have adopted local foodways. Therefore, it can be argued that mobility left little recognizable dietary trace. Meanwhile, at Kadıkalesi (where we lack aDNA results) isotopic signatures are compatible with a mixed and socially stratified population. Non-parametric tests such as the Kruskal–Wallis test confirmed significant differences in δ 13C values between males and females, as well as between age groups at Kadıkalesi, reinforcing the view that diet was stratified within a cosmopolitan setting. The broader δ 15N ranges observed, including individuals with unusually high or low values, are likely to reflect differential access to animal or marine protein, fasting regimes, or perhaps variations in social status. Such variability is consistent with the interpretation of the site as a cosmopolitan and multi-ethnic community. By contrast, no statistically significant isotopic differences were observed within the Barcın population, suggesting a more uniform rural diet. As Garnsey argues, dietary divergence in urban versus rural settings is not expected, given the ‘patriarchal system that governed society’ (Garnsey, Reference Garnsey1999: 108; see also Garvie-Lok, Reference Garvie-Lok2001: 2; Garland, Reference Garland2006). This situation underscores how scale, connectivity, and population composition may have had an effect on the variability of the foods consumed within Byzantine Anatolian settlements.

Intra-settlement variability between an urban centre and a rural community in western Anatolia during the Byzantine period can be assessed using δ 15N values. Aside from the fact that the difference in δ 15N values between the two sites becomes clearer when local isoscape baselines are considered, cosmopolitan communities, such as Kadıkalesi Anaia, exhibit a broader interquartile range, demonstrating a more widely dispersed pattern and a greater spread. This can be explained by a mixed population of multi-ethnic character of Kadıkalesi, a much-visited port city. Conversely, the smaller coefficient of variation among adults at Barcın Höyük is due to it being a small rural settlement where dietary choices were similar and opportunities for varied food options were limited. Comparing Barcın Höyük and Kadıkalesi Anaia highlights the contrast between a cosmopolitan city and a hinterland settlement regarding diverse dietary differences within western Anatolia in the Byzantine period.

By uniting isotopic and genetic datasets, this study shows that modest shifts in isotopic values when viewed in combination with archaeological contextual information and aDNA data can reveal complex relationships between mobility, ancestry, and subsistence. The findings highlight the differences between rural and urban communities and enrich our understanding of interactions between environment, economy, and identity in Byzantine Anatolia.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2025.10027.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Nikos Kontogiannis for their suggestions on the text, and Emma Baysal and Holly Miller for their invitation to include Rana Özbal in the NAFR1180204 Newton Advanced Fellowship Grant dedicated to isotopic analyses. We also thank Angela Lamb of the British Geological Survey for her help and advice with establishing protocols and standards for conducting the analyses in Turkey. Finally, we are grateful to the Turkish Energy, Nuclear and Mineral Research Agency Element Analyzer Isotope-Ratio Mass Spectrometry team, especially Yüksel Mert.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding

The funding for the isotopic and DNA analyses conducted in this project generously comes from a Koç University’s Center for Late Antique and Byzantine Studies (GABAM) Research Grant awarded to the corresponding author. The Barcın Höyük excavations were funded by the Dutch Research Council (380-62-005).