Introduction

Against the continuing backdrop of the economic crisis, 2013 had been dominated by President François Hollande's declining popularity (see Startin Reference Startin2014: 124). The year 2014 would prove to be another challenging year for the French President. It began with damaging allegations surrounding an ‘affair’ with actress Julie Gayet and was followed by heavy defeats for his ruling Socialist Party in the March municipal and May European elections. In the latter contest, the Front National (FN) added salt to the wound by topping the poll – the first time the party had been victorious in a national election. Hollande reacted to the municipal election defeat by replacing Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault with Minister for the Interior Manuel Valls. The change of government appeared to have no immediate effect on the President's personal rating. With his principal electoral promise of reducing France's stubbornly high unemployment showing no sign of fruition, and with the French economy remaining sluggish, his 12 per cent approval rating in the monthly YouGov survey represented an all-time low for a French President in the history of modern-day polling.

Election report

Municipal and communal elections, March 2014

The municipal and communal elections took place over two rounds on the last two Sundays of March – the former in the 36,681 French communes with more than 1,000 inhabitants and the latter in the communes of less than 1,000. Turnout in the first round was just under 64 per cent, a slight improvement on the two previous contests in 2008 and 2001. In the second round, the level of abstention was up slightly compared to the two previous contests with 62 per cent of registered electors casting their vote (Ministère de l'Intérieur 2014a). The most significant outcome of the election was that the mainstream right were the clear victors (Kuhn Reference Kuhn2014: 408). The Socialist Party suffered its biggest defeat in this electoral context since 1983 (Evans & Ivaldi Reference Evans and Ivaldi2014). The left bloc as a whole lost control of more than 150 towns with over 10,000 inhabitants, including Amiens, Angers, Caen, Chambery, Reims, Saint-Etienne, Toulouse, Tours and Limoges (the latter having been run by the left since 1912).

For the mainstream right, the result was a resounding victory with the centre-right Gaullist Union pour un Mouvement Populaire (UMP) the major beneficiary. Over 155 towns of over 9,000 inhabitants changed hands from left to right, including former left-wing bastions such as the southwestern city of Toulouse (Evans & Ivaldi Reference Evans and Ivaldi2014). UMP alliances with old allies in the centre-ground also bore fruit with François Bayrou's MODEM and Jean-Louis Borloo's Union des démocrates et indépendants (UDI) also contributing significantly to the right's share of municipal victories, notably in cities such as Bordeaux and Pau (Evans & Ivaldi Reference Evans and Ivaldi2014). In terms of France's two rival second cities, the left retained Lyons and the UMP held on to Marseilles (Kuhn Reference Kuhn2014: 410). In Paris, a bastion of the right between 1977 and 2001, Anne Hildago, the previous Socialist deputy mayor, defeated her UMP rival Nathalie Kosciusko in a contest where the parties contested seats in the 20 different Parisian arrondissements.

For the FN, Paris was one of the few areas of France where the party made no discernible progress, failing to win representation in any of the capital's arrondissements. Nationally though, the municipal election represented its best ever performance in this electoral setting, with the party winning 12 councils and returning over 1,500 councillors. The result consolidated the party's position as a significant player in its existing regional strongholds, notably winning the former mining town of Hénin Beaumont in the north and retaining Orange in the south. Despite these notable performances, the FN polled only 7 per cent nationally in the first round, which did not necessarily merit the extensive media coverage the party's result received both in France and internationally (Mondon Reference Mondon2014). The fact that the French Green party EELV list won majority control from the Socialists of the Alpine capital Grenoble, an urban agglomeration of far greater significance than the towns where the FN were victorious, received rather scant media coverage in contrast. Significantly, with regard to the government's ailing credibility, six of the 17 ministers standing for election locally were defeated.

In terms of gender parity, in no small part due to the parity legislation in place for the municipal elections, approximately 40 per cent of those elected were women. Following the elections, the major cities of Aix-en-Provence, Amiens, Lille, Nantes, Rennes as well as the capital all had female mayors. (Kuhn Reference Kuhn2014: 411).

The overwhelming conclusion to be drawn from the result of the municipal elections was that the President's unpopularity and the national political context had impacted heavily on the Socialist Party in terms of local politics. The President responded with a change of Prime Minister, a government re-shuffle and a change of Socialist Party secretary. The result would also have a direct impact on electoral developments later in the year given that ‘mayors and councillors are responsible for electing representatives’ to the French upper house (Kuhn Reference Kuhn2014: 411). This did not bode well for the Socialists’ prospects for the elections scheduled for September.

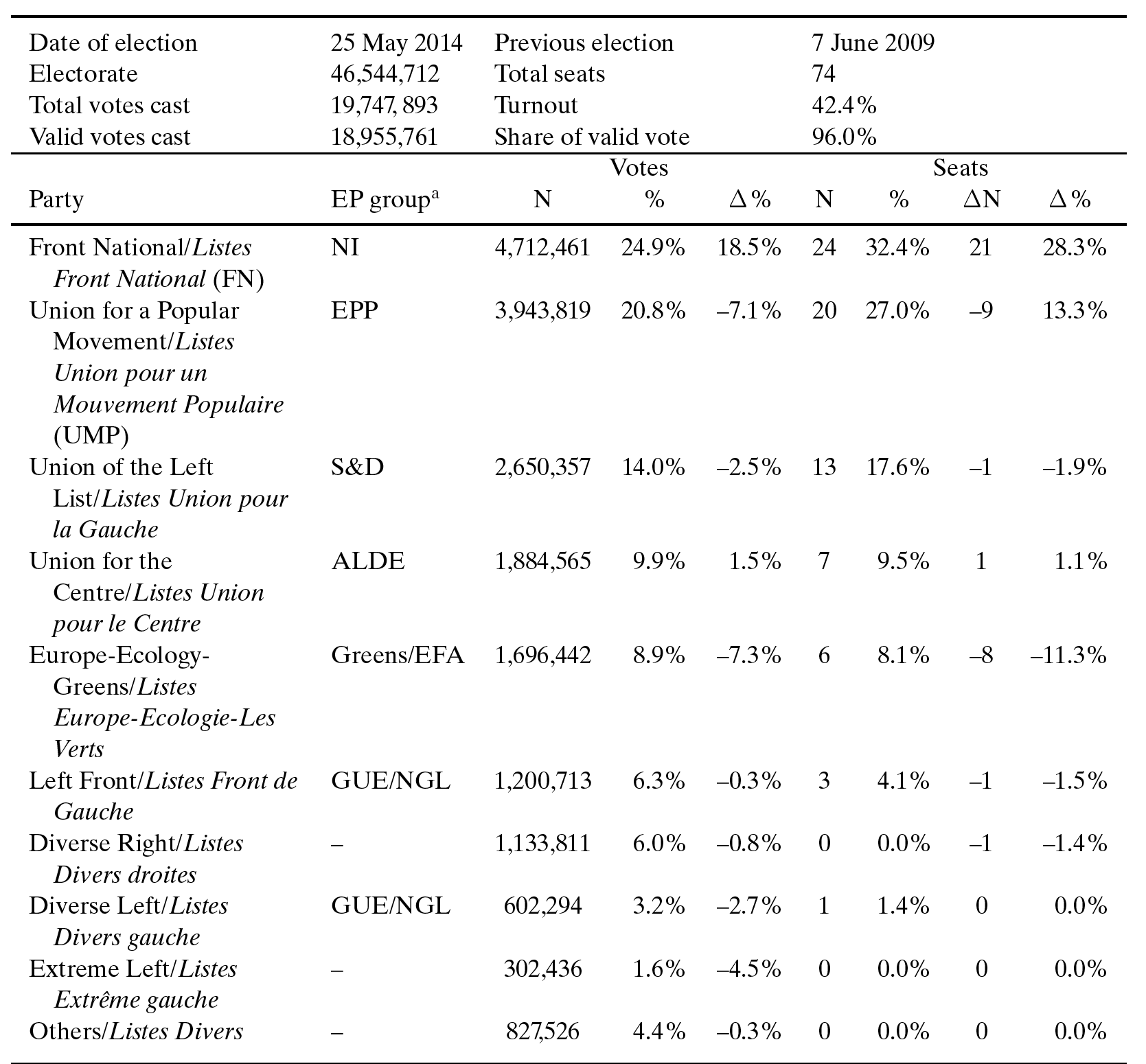

European Parliament elections, May 2014

The second major mid-term test for the Socialist Party, scheduled just a couple of months after the municipal elections, were the European elections on 25 May. A total of 74 seats were contested at what was the eighth set of European elections in France. This was two more than in the previous contest in 2009. Turnout was up on 2009 with just over 42 per cent of registered voters casting their vote, compared to 41 per cent in 2009 (Ministère de l'Intérieur 2014b). Both the proportional nature of the electoral system and the ‘second-order’ nature of the contest played into the hands of the FN, who profited from the strong anti-EU sentiment prevalent in a campaign inevitably caught up in the ensuing eurozone economic crisis. It emerged as the leading French party, polling 25 per cent of the vote and winning 24 seats – a vast improvement on its showing in 2009 when the FN polled just 6 per cent as the party split and had to combat the rival, breakaway Parti de la France list led by Carl Lang. The result was a highly significant development not only because it was the first time that the party had been victorious in a national-level election, but also because it was the first time that a party other than the Socialist Party or the UMP had not been victorious in a European electoral context. With the FN coming first in 16 of France's 22 metropolitan regions, party leader Marine Le Pen was able to proclaim her party as the ‘premier parti de France’ (Le Pen Reference Le Pen2014).

For the Socialist Party and for President Hollande, the result was another major setback following the municipal elections. Polling 14 per cent of the vote, it was third behind the FN and the UMP, which represented its lowest ever score in the eight European elections in France since 1979. For the other main French party – the centre-right UMP – although it succeeded in finishing comfortably ahead of its Socialist rival, not beating the FN was nevertheless a setback. The party's 21 per cent vote resulted in the loss of nine of its 29 seats. The poor showing contributed to the resignation of UMP leader Jean-Marc Copé, whose position within the party had been greatly weakened following the disputed leadership contest with former Prime Minister François Fillon (see Startin Reference Startin2013: 78). During the campaign, the party appeared somewhat divided in terms of its position over Europe, with Fillon's more conciliatory stance towards the EU in contrast to Copé’s more Eurosceptic discourse.

For the Greens, their EELV list polled 9 per cent, down more than 7 percentage points compared to 2009, resulting in the loss of eight of its 14 seats. The two other main blocs in the French party system, François Bayrou's Union du Centre and Jean-Luc Mélenchon's Front de Gauche performed similarly to 2009 (see Table 1).

Table 1. Elections to the European Parliament in France in 2014

Note

a For acronyms, see the introductory chapter ‘Political data in 2014’.

Source: Ministère de l'Intérieur (2014b).

Senatorial elections, September 2014

The third set of elections in the congested French electoral calendar in 2014 was the senatorial elections to the French upper house, which took place on Sunday, 28 September. As with the two previous contests in 2014, the result was a resounding defeat for the Socialist Party. Half of the 348 seats in the French Senate were up for election, with the voting undertaken by an electoral college of 87,000 ‘grands électeurs’ made up of city councillors and local officials (Penkerth Reference Penkerth2014).

The centre right UMP was successful in winning back the majority obtained by the left in 2011. The shift to the right led to the resignation of the Socialist President of the Senate Jean-Pierre Bel, although he had previously announced in March in an article in Le Monde that he would not seek re-election in his seat in the Ariège (Bonnefous & Lemarié Reference Bonnefous and Lemarié2014). The UMP's Gérard Larcher became the new President of the Senate, as the UMP's presidential majority jumped from 167 to 187 seats, while the Socialists went from 177 to 152 seats (Ministère de l'Intérieur 2014c).

Notably, the FN won its first two seats in the Senate both in the south in Marseille and Fréjus, in spite of an electoral system which historically had squeezed it from office. This was another significant development in the continued entrenchment of the FN, with the party having representation at all levels of French office barring the Presidency itself – a sobering thought for the UMP as it continued to attempt to assert itself as a viable alternative to the Socialists.

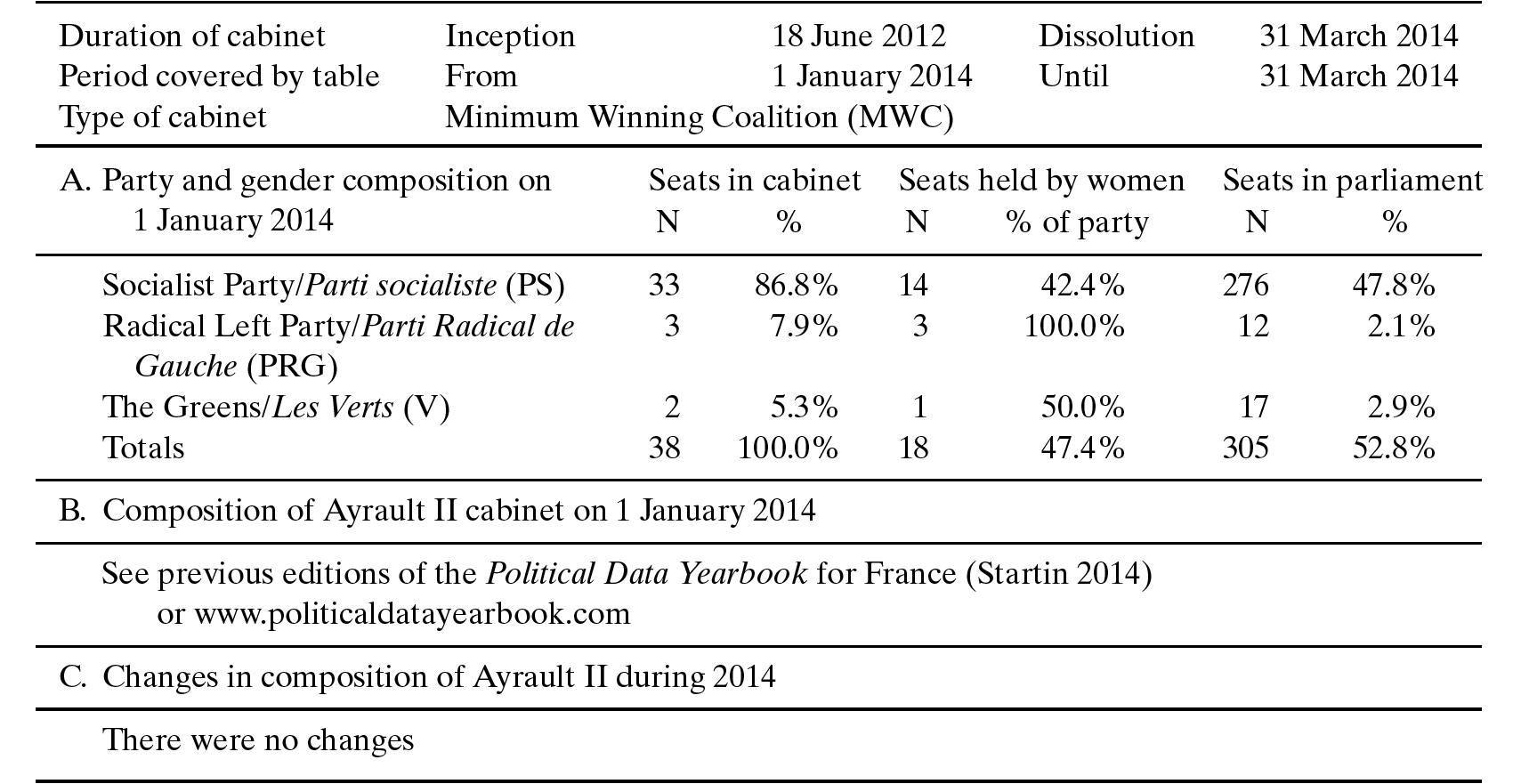

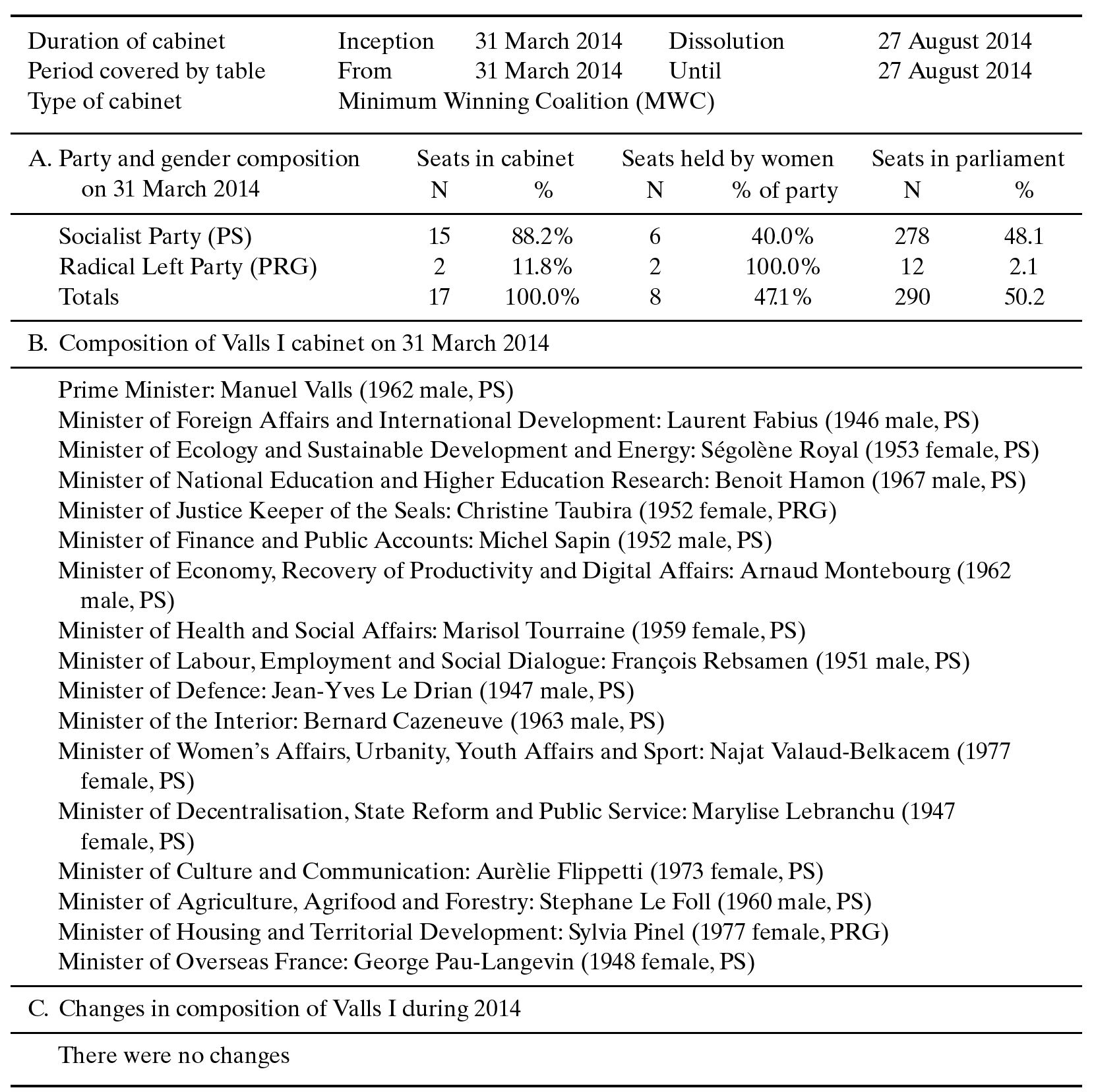

Cabinet report

On the back of the aforementioned municipal election result and the resounding defeat of the Socialist Party, Manuel Valls, the Minister for the Interior, was appointed Prime Minister on 31 March following the resignation of Jean-Marc Ayrault. Valls’ new cabinet – in effect Hollande's third after Ayrault I and Ayrault II (see Startin Reference Startin2013, Reference Startin2014) – which lasted until late August, was in numerical terms one of the smallest in the history of the French Fifth Republic, with just 16 full members. The French Greens (EELV), who had been members of the previous Ayrault cabinets, chose not to participate in the new government and were unrepresented in a cabinet which comprised 15 members of the Socialist Party and two of the Radical Left Party. All but two members of the new cabinet had either been ministers or junior ministers in the previous Ayrault cabinet, and nine ministers kept the same portfolio. President Hollande's former partner and former Socialist Presidential candidate Ségolène Royal was recalled to the cabinet for the first time since 1993. Moreover, 14 junior ministers were appointed on 9 April in a cabinet with gender parity in terms of its composition.

Table 2. Cabinet composition of Ayrault II in France in 2014

Source

Startin (Reference Startin2014).

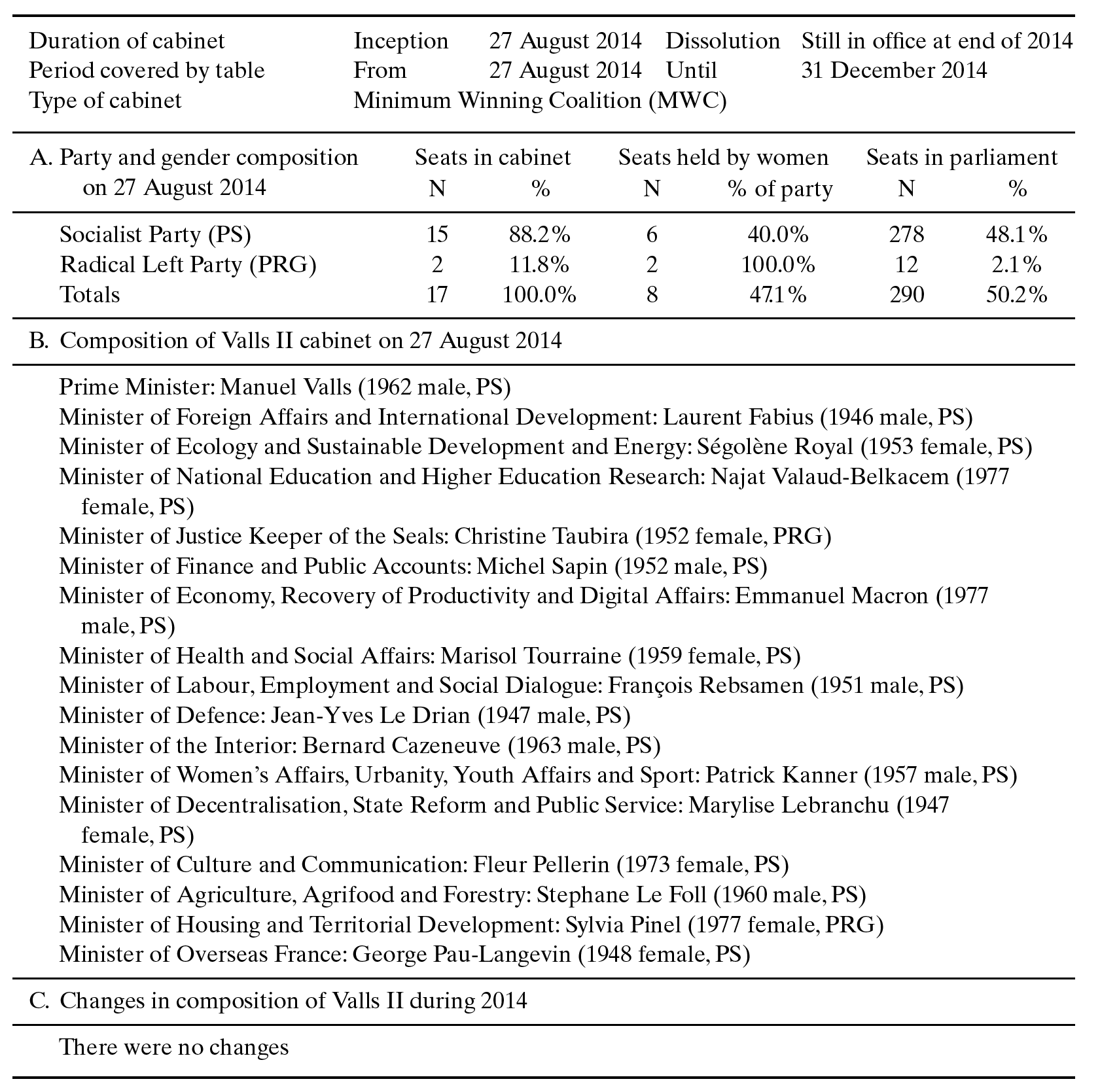

On 27 August, Valls I was dissolved and a new government was appointed with Valls remaining Prime Minister. This development appeared as something of a bolt out of the blue. Valls’ motivation for a new government as opposed to a simple reshuffle was to draw a line in the sand with regard to criticisms from a number of dissenting voices on the left of the party. These were primarily related to the government's budgetary restrictions designed to reduce France's eurozone deficit, with criticism coming chiefly from Minister for the Economy Arnaud Montebourg and Minister for Education Benoit Hannon.

Issues in national politics

Following the damaging Cahuzac Affair for the President and the government in 2013 (see Startin Reference Startin2014: 127), political scandal continued to dominate the political agenda in 2014. This time the scandal was of a more personal nature for the French President. The disclosure of his ‘affair’ with Julie Gayet in January led to the end of the relationship with his partner, the journalist Valérie Trierweiler. Later that year she published a book entitled Merci pour ce moment, wherein she accused Hollande of calling poor people ‘toothless’ (L'année Canard 2014: 6). Despite this political gift for the mainstream right, the UMP were unable to make political capital from this development. In June, their leader Jean-Francois Copé was forced to resign following a police search of UMP headquarters, with claims that in 2012 the party ordered fake invoices to cover the costs of Nicolas Sarkozy's failed re-election presidential campaign – a campaign run by Copé himself (Euronews 2014). A month later, Nicolas Sarkozy was placed under formal investigation on suspicion of trying to influence senior judges with regard to his 2012 campaign finances. This development did not appear to damage Sarkozy, who suggested a potential return to party politics in September and two months later was elected as the UMP party secretary with 65 per cent of members backing his candidacy (BBC 2014). This only served to fuel speculation that he would seek to run for the 2017 presidential nomination in what would be a remarkable political comeback. However, with former Prime Minister François Fillon accusing President Hollande's chief of staff Jean-Pierre Jouyet of lying about a media report in Le Monde that accused the former Prime Minister of pressuring Jean-Pierre Jouyet to speed up the legal case against his rival Nicolas Sarkozy, the UMP appeared divided (Hopquin Reference Hopquin2014).

Table 4. Cabinet composition of Valls II in France in 2014

Source

Présidence de la République (2014).

By the end of the year, on the back of a wave of industrial action which affected both the trains and airlines, with the French economy still very sluggish, the cost of living still high, unemployment showing no signs of abating, Hollande remaining the most unpopular President in the history of the Fifth Republic and both the two main parties’ poll ratings remaining stubbornly low, it was Marine Le Pen who appeared to be in the ascendancy with one poll suggesting that she could theoretically beat Hollande in the second round of the 2017 contest (Penkarth Reference Penkerth2014). With Hollande stating that he would not stand for the Presidency for a second time if unemployment did not start to fall, the year came to a conclusion with continued speculation that he might have the dubious honour of being the first incumbent French President not to stand for a second term of office.

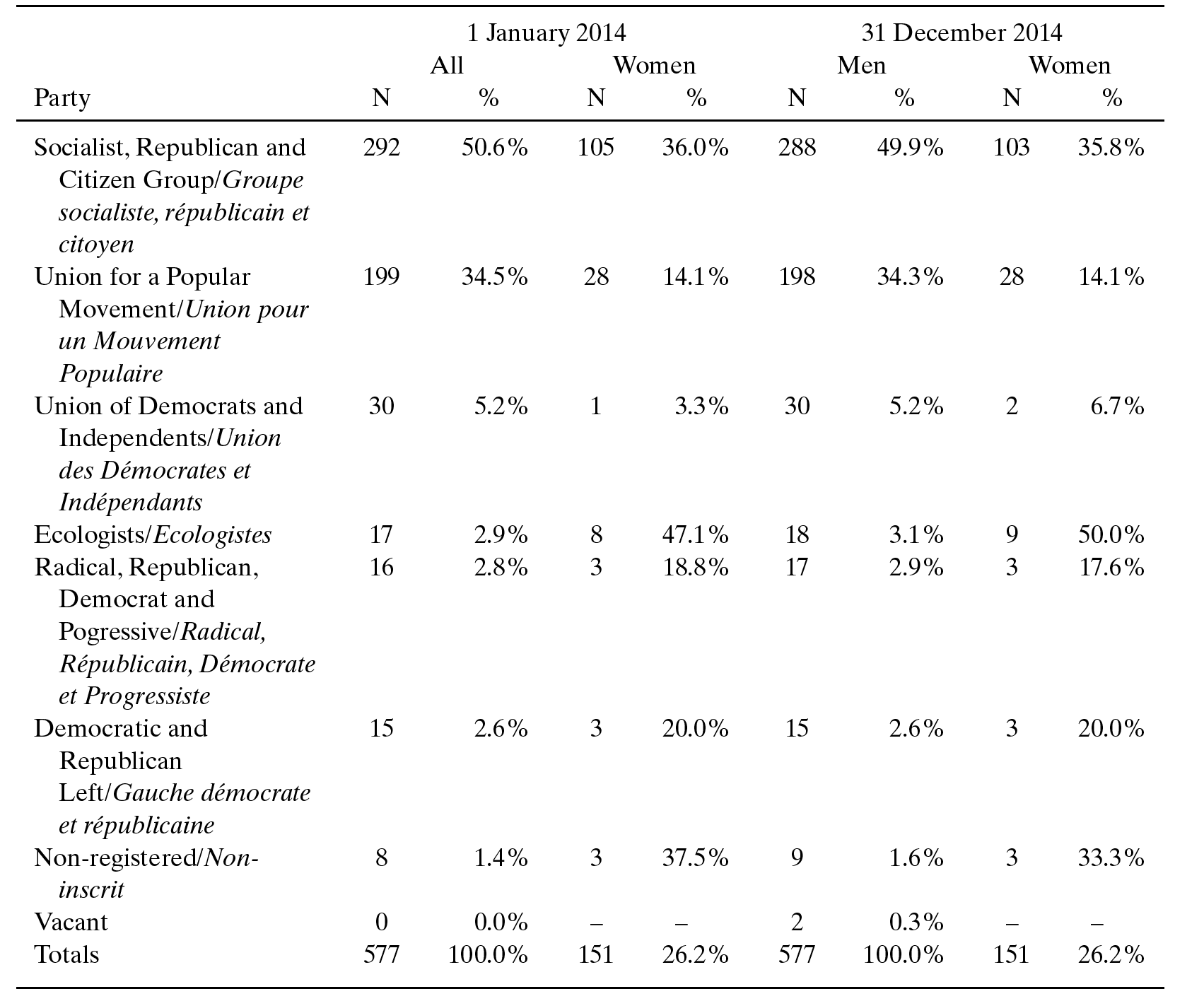

Table 5. Party and gender composition of the lower house (Assemblée Nationale) by parliamentary group in France in 2014

Source

Assemblée Nationale (2014).