Introduction

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental condition that often persists into adulthood with varying symptom severity, with prevalence rates ranging between 2.58% and 6.76% (Song et al. Reference Song, Zha, Yang, Zhang, Li and Rudan2021). Adult ADHD is linked to academic underachievement, lower occupational status, substance misuse, limited social relationships, accidents, and offending behaviours (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Yang, Chen, Lee, Teng, Lin and Gossop2016; Willcutt et al. Reference Willcutt, Nigg, Pennington, Solanto, Rohde, Tannock, Loo, Carlson, McBurnett and Lahey2012; Graaf et al. Reference de Graaf, Kessler, Fayyad, ten Have, Alonso, Angermeyer, Borges, Demyttenaere, Gasquet, de Girolamo, Haro, Jin, Karam, Ormel and Posada-Villa2008; Altszuler et al. Reference Altszuler, Page, Gnagy, Coxe, Arrieta, Molina and Pelham2016; Narad et al. Reference Narad, Garner, Antonini, Kingery, Tamm, Calhoun and Epstein2018; Young et al. Reference Young, Moss, Sedgwick, Fridman and Hodgkins2015). These issues reduce quality of life and carry social and economic costs (Sciberras et al. Reference Sciberras, Streatfeild, Ceccato, Pezzullo, Scott, Middeldorp, Hutchins, Paterson, Bellgrove and Coghill2022). These associations have been reported across studies using both DSM-IV/ICD-10 and DSM-5 diagnostic frameworks.

The prevalence and impact of ADHD in Irish adults is under-researched. A study conducted in an Irish Community Mental Health Team (CMHT) found adult ADHD prevalence rates of 13.25–16.72%, despite just 0.5% having a prior diagnosis (Adamis et al. Reference Adamis, Fox, de M de Camargo, Saleem, Gavin and McNicholas2022). Other Irish research highlights the effects of late diagnosis: educational struggles, low self-esteem, and stigma around accessing services and diagnosis (Watters et al. Reference Watters, Adamis, McNicholas and Gavin2018). The HSE has previously deemed adult ADHD as a `major public health and social problem’, prompting policy recommendations for specialist assessments and supports (Health Service Executive, 2021, Department of Health, 2020).

Service context

The HSE is Ireland’s public health and social care organisation. Prior to 2021, Ireland had no public services for adults with ADHD (HSE, 2021). The National Clinical Programme for Adult ADHD (NCPAA) began with a working group in 2016 and launched its first demonstration clinic in 2018, with an aim to establish 12 tertiary-level adult ADHD services nationwide. NCPAA teams are resourced with a consultant psychiatrist, senior psychologist, mental health nurse (clinical nurse specialist), senior occupational therapist and an administrator, providing a multi-modal clinical approach. New service-users are referred by GPs to CMHTs for assessment of moderate to severe mental health issues and those screening positive for ADHD are referred to the NCPAA service. Direct referral pathways are available for service users who are already in CMHT services and for service users transitioning from Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). NCPAA teams use the Diagnostic Interview for Adult ADHD (DIVA) to assess symptoms and identify co-occurring conditions. Post-diagnosis ADHD-specific supports include medication, psychology supports, occupational therapy and links to external wellbeing and employability services.

This research aims to evaluate the first three NCPAA teams established in Ireland: CHO1: Sligo/Leitrim/Donegal, CHO3: Limerick/Clare/North Tipperary and CHO6: Dun Laoghaire, Dublin Southeast and Wicklow (North, South and East). Given the recent establishment of the NCPAA, it is essential to evaluate how the programme is functioning in practice, both in terms of clinical outcomes and user experience. Such evaluation provides an evidence base for policy and service planning, helps identify areas of strength and areas requiring development, and contributes to the limited international literature on public adult ADHD services.

Research questions

This study asks the following questions: (1) What are the demographics and clinical presentations (symptoms and daily life challengesFootnote 1 ) of adults with ADHD presenting to the NCPAA services in Ireland? (2) To what extent do service users receive the supports outlined in the NCPAA model? (3) How effective are the NCPAA services in improving symptoms and daily life challenges? (4) How acceptable are the NCPAA services to service users? (5) What could be improved about service delivery?

Methods

Participants

A total of 249 adults (51% women, 42% men, 4% non-binary, 1% other, 2% preferred not to say) were recruited via consecutive case sampling from the three NCPAA services. Inclusion criteria were (a) aged 18 or older, (b) attending one of the three services, and (c) an ability to read and write in English. Of 543 invited participants, 249 (46%) completed the baseline (Time 0) survey; 101 completed the 6-month follow-up (Time 1) survey (n = 91 diagnosed with ADHD; n = 10 not diagnosed); and 42 completed the 12-month follow-up (Time 2) survey.

Measures

Demographics

Participants provided age, ethnicity, employment status, education level, and relationship status.

ADHD symptoms

The 18-item Adult Self Report Scale (ASRS v1.1; Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Adler, Ames, Demler, Faraone, Hiripi, Howes, Jin, Secnik, Spencer, Ustun and Walters2005) was used to assess ADHD symptoms. Part A screens for ADHD with six predictive items, and Part B provides further detail via 12 DSM-IV-aligned questions. Items are rated on a 0–4 Likert scale (‘never’ to ‘very often’). Internal reliability was high (Time 0: α = .85; Time 1: α = .87; Time 2: α = .92).

Daily life challenges

The 69-item Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale – Self Report (WFIRS-S; Weiss et al. Reference Weiss, McBride, Craig and Jensen2018) assesses challenges across seven domains (family, work, school, life skills, self-concept, social, risk-taking). Items are scored from 0 (‘never’) to 3 (‘very often’), or ‘not applicable’. Domains are considered impaired if one item scores 3 or two score 2. Mean scores enable domain-level comparisons. Internal reliability was high (Time 0: α = .94; Time 1: α = .94; Time 2: α = .98).

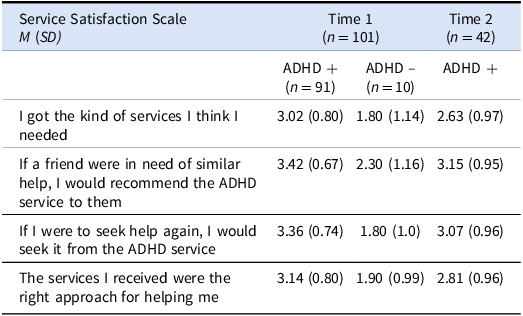

Service satisfaction

The Service Satisfaction Scale (SSS; Athay and Bickman Reference Athay and Bickman2012) includes four Likert-style items (1 = ‘definitely not’ to 4 = ‘definitely yes’) and two open-ended questions. The SSS is a shortened version of the CSQ-8 and showed strong reliability (Time 1: α = .93; Time 2: α = .95) (Attkisson and Greenfield Reference Attkisson, Greenfield and Maruish1994).

Support type and frequency

Participants reported on support received, including number and type of appointments, format (individual or group), missed appointments, use of online services, ADHD medication (type, duration), and any external ADHD supports

Procedure

Data were collected online at three time points. At baseline (Time 0), participants accessed the online survey by scanning a QR code included in a recruitment leaflet, which was sent with their initial appointment letter. After providing consent, they completed demographic items, ASRS and WFIRS-S, and were invited to provide email for follow-up. At six-month follow-up (Time 1), consenting participants were contacted. Those not diagnosed completed the SSS only. Those diagnosed indicated prior diagnosis, medication use, and completed the ASRS, WFIRS-S, SSS and questions on the types of supports received. At twelve-month follow-up (Time 2), participants who confirmed at Time 1 that they had received a diagnosis of ADHD repeated the same measures.

Analyses

Quantitative Data

Data were analysed using SPSS 29.0. Descriptive statistics summarised demographics, satisfaction, and service use. Repeated measures ANOVAs examined changes in ASRS and WFIRS-S scores across timepoints (p < .05).

Qualitative Data

Reflexive thematic analysis was conducted by the lead and senior author using Braun and Clarke’s six-phase framework to address research questions 4 and 5 (Reference Braun and Clarke2021). Codes were generated following immersion and discussed collaboratively to form themes. This study used anonymous online surveys with open-ended questions to collect qualitative data. While such data may lack the depth of face-to-face interviews, online surveys can still generate meaningful and reflective responses, particularly when participants are invited to share their experiences in their own words (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2021). The primary researcher was a PhD student with a particular interest in ADHD and prior awareness of challenges in implementing the model. This positionality may have influenced the analysis; therefore, reflexive practices and supervisory discussions were used to remain attentive to potential biases.

Missing data

Nine participants were excluded at baseline for incomplete measures. At Time 1, 148 participants (59%) did not complete the survey. Attrition was associated with age and symptom severity, indicating data were Missing Not at Random (MNAR) (Supplementary Table 1). At Time 2, 59 of the eligible sample did not respond (54%). Multiple imputation was not used due to the level of missingness; instead, a complete case analysis was conducted, with sensitivity analysis to assess robustness.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics of NCPAA service users

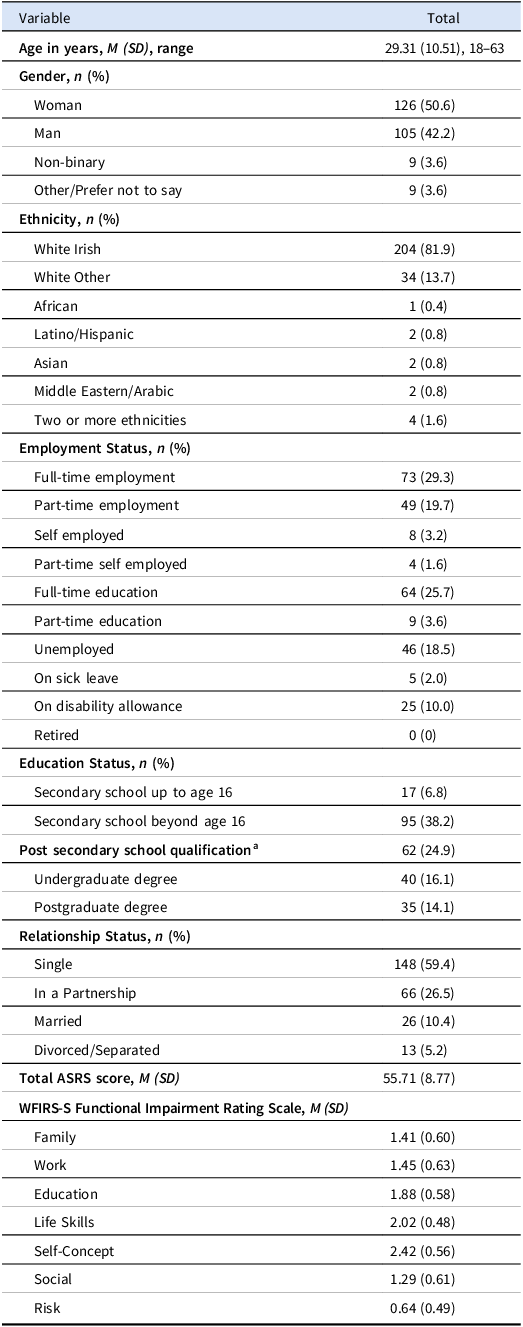

Table 1 summarises the demographic and clinical characteristics (ASRS and WFIRS-S scores) of the 249 participants who attended the NCPAA services for an initial assessment. This includes all service users, regardless of whether they ultimately received an ADHD diagnosis.

Table 1. Demographics and clinical characteristics of NCPAA service-users (N = 249)

a Defined as a level 5 or 6 post-Leaving Certificate qualification on the Irish National Framework of Qualifications (Quality and Qualifications, Ireland 2021).

Regarding daily life challenges measured by the WFIRS-S, a high proportion of participants scored above the clinical threshold indicating challenges across several domains: life skills (92%), self-concept (87%), education (78%), work (76%), social (70%), family (69%), and risk (48%).

Of the 91 diagnosed service users, 35% (n = 32) had a prior ADHD diagnosis, and 9% (n = 8) were on medication before attending the service. At Time 1, 55% (n = 50) of participants were taking ADHD medication (44 stimulant, 6 non-stimulant), and at Time 2, 57% (n = 24) were on medication (23 stimulant, 1 non-stimulant). At Time 2, 38% (n = 16) of respondents had been discharged to their CMHT or GP.

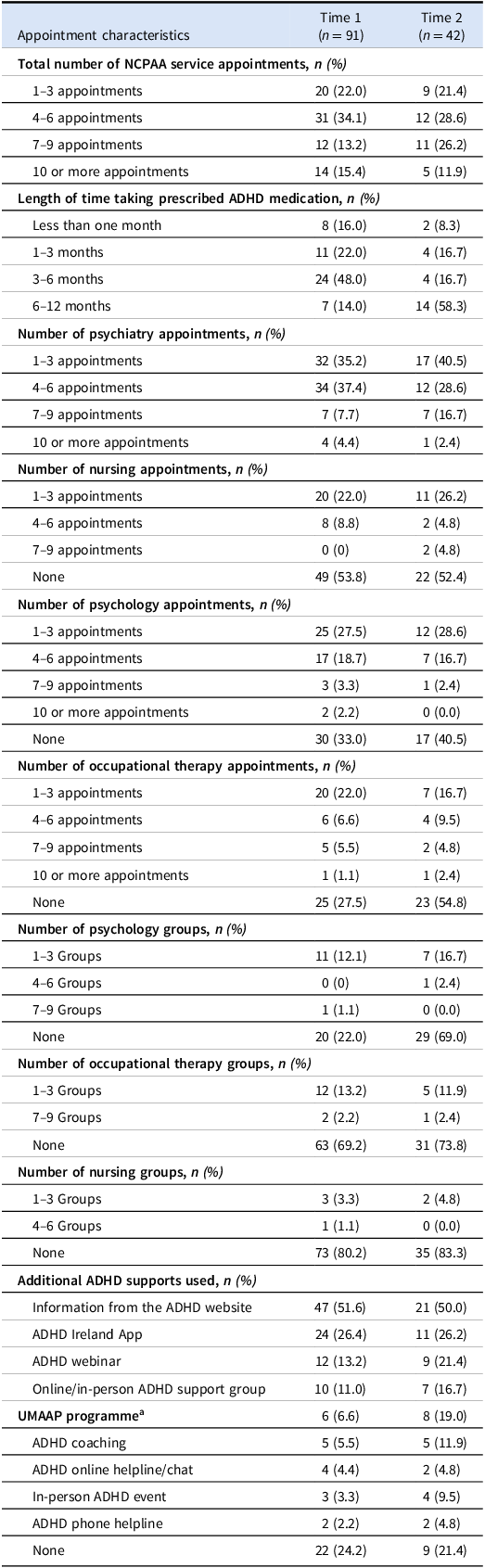

Supports received by NCPAA service users

Table 2 presents service user data from follow-up surveys. Service users primarily engaged with psychiatry and medication management, and a substantial proportion had little or no contact with psychology, occupational therapy, or nursing, and participation in group-based supports was limited. Use of external supports such as ADHD Ireland resources was more common but still not universal.

Table 2. NCPAA service use at time 1 and time 2 Follow-up

a Understanding and Managing Adult ADHD Programme (Seery et al. Reference Seery, Leonard-Curtin, Naismith, King, Kilbride, Wrigley, Boyd, McHugh and Bramham2023).

At Time 1, 33% (n = 30) of participants missed 1–3 appointments due to forgetfulness (67%), personal health issues (27%), work (20%), transport (17%), unsuitable timing (13%), and family commitments (10%). At Time 2, 31% (n = 31) missed appointments, mainly due to forgetfulness (32%) and transport issues (10%). At Time 1, 23% (n = 21) had attended an online appointment with an average satisfaction rating of 7.8 out of 10 (SD = 2.40), while at Time 2, 26% (n = 11) attended online appointments with an average satisfaction rating of 6.6 out of 10 (SD = 3.40). A total of 41% (n = 37) had a preference for online appointments at Time 1.

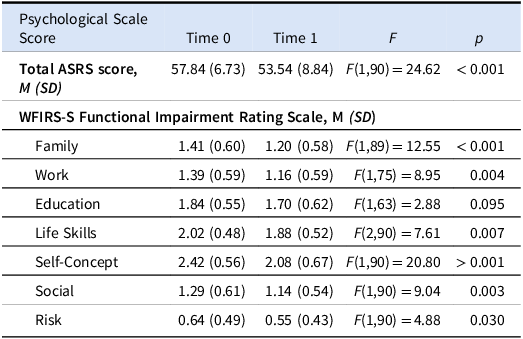

Efficacy of NCPAA services

A repeated measures ANOVA with complete case analysis was conducted on participants diagnosed with ADHD at the six-month follow-up (n = 91) to assess differences between Time 0 and Time 1. Results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Comparing time 0 and time 1 scores for ADHD group only (n = 91)

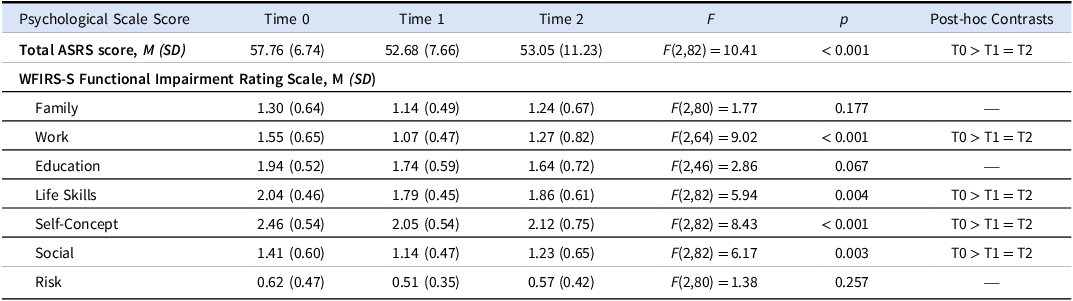

A repeated measures ANOVA was conducted across all three time points at one-year follow-up (n = 42), with results in Table 4. Post hoc contrasts are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 4. Comparing time 0, time 1 and time 2 scores for ADHD group only (n = 42)

An independent t-test found no significant difference in ASRS or WFIRS-S scores between those prescribed medication and those not at either Time 1 or Time 2.

Sensitivity analysis

Due to high attrition rates, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using three methods: mean imputation (preserving data variability but prone to bias if data are missing not at random), last observation carried forward (LOCF, a conservative approach underestimating changes), and Pearson’s correlation (to assess the impact of age on outcomes as attrition was associated with age and symptom severity). The results indicate that even with conservative methods for missing data, scores remained statistically significant, supporting the robustness of the main findings. Full details are available in supplementary tables 3–10

Acceptability of NCPAA services

Table 5 presents the SSS scores at Time 1 and Time 2. The SSS was completed by all Time 1 participants, but only those diagnosed with ADHD at Time 2, as non-diagnosed users had no further contact with the service. At Time 1, the average for those diagnosed with ADHD across the four items was 3.24, indicating high satisfaction overall on a 1–4 scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). At Time 2, the average across the four items dropped to 2.92, indicating a moderate moderate-to-high satisfaction overall.

Table 5. Service satisfaction scale scores at time 1 and time 2

Qualitative data

Following Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2021), quotes are used to illustrate themes and highlight participant experiences. As the survey was anonymous, no pseudonyms are assigned; quotes are simply attributed to “a participant” to protect anonymity while centring their voices. Participants were firstly asked, “What did you like most about the service?” Responses were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis. Consistent codes emerged across both timepoints and among individuals with and without an ADHD diagnosis. Three key themes were identified. The first theme is Feeling Affirmed: Participants described feeling validated and accepted by clinicians who acknowledged their ADHD. One said, “The doctors/psychologists were very compassionate and knowledgeable about ADHD all the way through. It made the experience I was very nervous about easy.” Another shared, “Any concerns or questions I have are taken seriously and I do not feel like I’m being spoken down to.” For some, receiving a diagnosis was transformative: “I’ve known something was wrong all my life. Finally getting diagnosed with ADHD has really helped me to understand myself much better.” The second theme is Benefits of Supports: Participants highlighted the positive impact of both medication and psychological supports. One commented, “My life has improved significantly since being on medication,” while another described it as a “life-changing experience.” CBT [Cognitive Behavioural Therapy], particularly in group settings, was highly valued. Others praised their clinicians: “[My psychologist] significantly improved the quality of my life.” Occupational therapy and group supports also stood out: “I think my experience would have been much less without the occupational therapist and the group.” The final theme is Person-Centred Care: Service-users appreciated the tailored approach. One shared: “It feels focused on my specific needs which is something that I haven’t experienced before.” Another said: “It’s amazing that the HSE has set up a service to look after people with ADHD. I feel like they’ve really thought about what we need and I’m so grateful.” Flexibility in treatment was also praised: “When I said I didn’t want to take medication, they offered CBT and Occupational Therapy instead. They allowed me to be ‘me.’”

Participants were then asked, “What could be improved about the service?” Reflexive thematic analysis again revealed three major themes: Barriers to Access: Many appreciated the free service but highlighted challenges with accessibility and logistics. One said: “The service is a two-hour drive from my home… It’s hard for someone with ADHD to make that trip.” Another added: “Travelling to the centre added a lot of stress… I had to find the money and time to drive 100+km for a conversation that could have been online.” Others wanted more flexible appointment scheduling and consistent reminders: “The text appointment reminders are so useful… It would also be great if there was an online portal to rearrange appointments.” Long wait times were a recurring frustration: “I waited for over a year for a diagnosis and now I’m waiting to see the psychologist for CBT. It’s exhausting.” Some felt the request for collateral evidence was burdensome: “They wanted evidence from my parents, but I have a bad relationship with them. It was hugely stressful.” Lack of Resources: Participants reported long waits and limited access to supports: “They need to hire more people, I had to wait for ages to see the occupational therapist.” Others shared disappointment at cancelled supports: “I was promised CBT, but it was withdrawn due to staffing issues.” Some experienced rushed assessments and unclear processes: “Nobody explained what I should expect… I was thrown into the deep end.” Lack of Ongoing Support: Many expressed a desire for continued care: “There is no monitoring or progression of me. I feel like I’ve been given a diagnosis and now I’m alone.” Another reflected: “When you’re at your appointment you feel seen but afterwards there’s no supplementary support.” One suggested: “It would be hugely beneficial if they had someone I could check in with once a month.” Others proposed follow-ups to group supports: “It would have been great to return after a month or two to go through how things were working in real life.”

Discussion

This research aimed to determine the efficacy and acceptability of NCPAA services, the demographics and clinical presentations of individuals presenting to the NCPAA services, supports received by NCPAA service users, and future service improvement.

NCPAA efficacy and acceptability

The clinical measures indicate that service users presented with substantial ADHD symptomatology, as reflected by a baseline ASRS mean score of 55.71 out of a possible 74 and high proportions exceeding clinical thresholds on all WFIRS-S domains. Statistically significant reductions in ADHD symptoms and improvements across life domains (especially in work, life skills, self-concept, and social domains) were observed at six months. Improvements were retained at the one-year follow-up, although the education domain showed limited change, suggesting that current supports might not be sufficiently tailored to address academic challenges. These findings demonstrate that NCPAA services have a positive impact on core ADHD symptoms and daily life challenges, reinforcing the utility of the service model in the early management of ADHD.

The Service Satisfaction scores and qualitative feedback indicate high levels of satisfaction with the NCPAA services provided, particularly among those diagnosed with ADHD. The themes of feeling affirmed, benefiting from supports, and receiving person-centred care are critical components of this satisfaction. Future efforts should focus on sustaining high satisfaction levels over time and addressing barriers to external service engagement to enhance overall support for individuals with ADHD. Although findings suggest meaningful improvements, the absence of a control group means these results should be interpreted with caution.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of NCPAA service users

The demographic profile of the cohort reveals a balanced gender distribution and a mean age of 29.31 years. The presence of non-binary and other gender identities underline the need for inclusive approaches in ADHD care.

Notably, the higher unemployment rate (19%) and elevated disability allowance uptake (10%) relative to national figures (4 and 3%, respectively) indicate that ADHD is associated with considerable occupational challenges (Central Statistics Office, 2023a). These disparities support earlier research linking ADHD with increased risk for economic and social disadvantages, emphasising the necessity for tailored vocational and psychosocial supports (Helgesson et al. Reference Helgesson, Björkenstam, Rahman, Gustafsson, Taipale, Tanskanen, Ekselius and Mittendorfer-Rutz2023; Adamis et al. Reference Adamis, Fox, de M de Camargo, Saleem, Gavin and McNicholas2022). Educational attainment among the ADHD group was relatively high, with 30% having completed higher-level education and 25% holding post-secondary qualifications. However, this figure is somewhat lower than national benchmarks; 63% of 25–34 year olds in Ireland achieve higher-level education qualifications (Central Statistics Office, 2022). This suggests that, despite the high educational aspirations, this group may face challenges that impede their academic progression. Furthermore, over half of the ADHD group reported being single, and while 5% were divorced or separated (compared to a general divorce rate of 0.06%), this likely reflects the interpersonal challenges often associated with ADHD, though direct comparisons are limited by differing data metrics (Central Statistics Office, 2023b; Wymbs et al. Reference Wymbs, Canu, Sacchetti and Ranson2021).

Supports received by NCPAA service users

The NCPAA Model of Care states that every service user should receive a package of care from a consultant-led MDT (psychiatry, nursing, psychology, OT), including assessment, medication management, psychoeducation, CBT, OT interventions, and group supports, However, service users in this study received some, but not all of these supports and in uneven amounts. Contact with nursing, psychology and OT was limited, and group interventions were rare. This indicates that while core elements of the model are being delivered, access to the full multidisciplinary programme is uneven, likely reflecting resource constraints. During the study period, a recruitment embargo imposed by the Health Service Executive (Health Service Executive, 2023b) likely constrained clinician recruitment. These limitations continue to present challenges for the effective operation of the NCPAA. Insufficient clinician availability may also have contributed to some of the dissatisfaction reported by service users.

Service engagement was multifaceted, as evidenced by consistent appointment attendance, stable medication use, and increasing adoption of online consultations. The persistent rate of missed appointments, predominantly attributed to forgetfulness, points to the need for improved reminder systems or more flexible options such as online appointments. These findings highlight the importance of embedding practical supports to optimise service engagement. The introduction of enhanced reminder systems (e.g., SMS or app-based alerts) and greater flexibility in appointment delivery, particularly through online or hybrid options, may help mitigate the impact of forgetfulness and logistical barriers. Incorporating such adjustments could strengthen continuity of care and maximise the effectiveness of NCPAA services. Finally, there was a notable lack of engagement with external services despite the availability of free supports from organisations like ADHD Ireland indicating that barriers persist in linking users to these valuable resources.

Efforts should be made to identify and overcome the barriers that hinder engagement with external supports, ensuring that users can access the full range of complementary services available from organisations like ADHD Ireland.

Strengths, limitations and directions for further research

A limitation of this study is the high level of attrition, with 59% of participants not completing the six-month survey and a further 54% of the eligible sample not completing the twelve-month survey. This left only 17% of the original cohort completing the twelve-month survey. The reduced sample size reduces representation and limits generalisability. Therefore, conclusions about the longer-term impact of NCPAA services should be interpreted with caution. Another limitation is that data collection coincided with recruitment constraints, likely affecting access, resource availability, and service satisfaction. As a result, the findings may not fully reflect how the services will function once they are more fully staffed and established. It is also possible that those with the greatest difficulties are not accessing NCPAA services due to barriers such as referral pathways, limited awareness of ADHD needed to seek out a referral, or logistical challenges. This raises questions about whether the sample is fully representative of the wider adult ADHD population and whether the findings may overestimate how well the programme functions in practice.

Despite these limitations, the research findings have several important implications for clinical practice. The marked discrepancies in employment outcomes and reliance on disability support highlight the need for integrated vocational rehabilitation and broader psychosocial services as part of ADHD management. Furthermore, the varied improvements across life domains suggest that more targeted supports, especially in educational settings, are needed to bridge specific gaps. Enhancing appointment management through technology-driven solutions (e.g. SMS reminders, online scheduling) may further improve engagement despite systemic constraints.

The strength of these conclusions is underpinned by a substantial initial sample and a twelve-month longitudinal design, with standardised measures (ASRS and WFIRS-S) offering a comprehensive assessment of ADHD symptoms and related challenges. Although attrition was significant (59% at Time 1 and 54% at Time 2), sensitivity analysis indicates that lower attrition might have shown even greater improvements. Another limitation of this research is the study design. Without a control group, the improvements observed cannot be taken as evidence of service efficacy; at best, they represent preliminary associations between service engagement and outcomes.

Future research should adopt strategies to improve follow-up participation and examine the long-term sustainability of clinical improvements. Further investigation into the contributions of tailored family and educational supports, as well as tracking employment outcomes post-intervention, will be essential to refine service delivery and ensure that the initial benefits are maintained over time. Finally, future research could usefully explore common co-occurring conditions, such as autism, to examine whether the needs of neurodivergent adults are being fully met within current service models.

Conclusion

In summary, the NCPAA model demonstrates efficacy and acceptability in managing ADHD symptoms and daily life challenges in the short term. However, these findings also highlight critical areas for enhancement, particularly in relation to academic support, sustained vocational engagement, the need for inclusive practice, and addressing the impacts of under-resourcing on service delivery. By refining support strategies and addressing systemic limitations, there is potential to achieve more robust and enduring outcomes for adults with ADHD.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2025.10151.

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to Fiona O’Riordan for her input and advice.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Heath Service Executive (02/11/2021 – PhD Funding for Evaluation of HSE National Clinical Programme for Adult ADHD).

Competing interests

Authors 1-8 are employed by the Health Service Executive.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of University College Dublin, the Health Service Executive and Saint John of God clg.