Introduction

Politics in many societies are increasingly shaped by the strong affective responses of citizens to those who do not share their political beliefs. Scholars have studied this phenomenon as affective polarization (Huddy & Bankert, Reference Huddy and Bankert2017; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012), an identity‐based positive bias towards elites and supporters of one's own party coupled with a dislike for rival parties and their supporters (Abramowitz & Webster, Reference Abramowitz and Webster2018).

While many negative outcomes have been ascribed to affective polarization (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019), one key concern is that partisan affect may increase tolerance for undemocratic behaviour by governments (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Stolle and Bergeron‐Boutin2022; Kingzette et al., Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021; McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Rahman and Somer2018; Orhan, Reference Orhan2022). According to this literature, affective polarization contributes to democratic erosion by increasing partisan loyalty and decreasing the importance citizens give to democratic procedures. More specifically, the strength of partisanship has also been found to be associated with ‘partisan double standard’ (Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020) or ‘democratic hypocrisy’ (Simonovits et al., Reference Simonovits, McCoy and Littvay2022), that is, the willingness to overlook democratic violations by one's own party. Affective polarization and partisanship have thus been posited as a key explanation for citizens' tolerance for democratic backsliding based on cross‐sectional evidence pointing to a relationship between the two processes (Orhan, Reference Orhan2022).

We question the unidirectionality of this argument and posit that in countries that have experienced significant democratic backsliding, partisan affect may also be shaped by a regime divide over democracy itself. Rather than focusing on the detrimental impact of the affective divide on citizens' willingness to resist democratic violations, we thus theorize the reverse perspective to argue that democratic backsliding may also forge a new regime divide that polarizes party evaluations around the very issue of liberal democracy itself. This perspective underscores the potentially positive role of political polarization for democracy.

In her work on coalition formation in new democracies, Grzymala‐Busse (Reference Grzymala‐Busse2001) contends that a regime divide between Communist successor parties and those that emerged from the Communist‐era opposition precludes cooperation across this divide, instead pushing parties to form coalitions within each camp despite ideological differences to avoid punishment by voters. We adapt this argument to the context of democratic backsliding. Instead of emphasizing how parties' historical legacies may drive coalition formation, we suggest that for citizens who prioritize liberal democratic values, a governing party that violates democratic norms and its supporters may become unacceptable. In turn, they may find other opposition parties and their supporters more acceptable, even when they disagree on policy grounds. Ultimately, an affective divide around democratic backsliding may thus drive opposition supporters to come together in defence of democracy with a view to removing the ruling party from office.

Our argument looks beyond the role of government supporters in sustaining democratic backsliding to address the role of the opposition in responding to democratic violations by the incumbent party. Previous studies have tended to adopt a critical perspective that highlights how affective polarization inhibits behaviours desirable for democracy and contributes to voters on either side of the affective divide tolerating backsliding by an in‐group incumbent (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Stolle and Bergeron‐Boutin2022, Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019; Pierson & Schickler, Reference Pierson and Schickler2020). In contrast, our perspective suggests that support for democracy need not necessarily systematically be undermined by affective polarization. Instead, democratic backsliding may effectively reinforce the commitment to democratic norms on one side of the affective divide, eventually favouring a joint mobilization by opposition groups. Hence, we suppose attitudes towards democracy to act as a potential transmission belt, with democracy becoming the very issue around which the affective divide is organized.

To explore this argument empirically, our pre‐registered study addresses two central questions: first, to what extent does a given party's government participation – rather than its ideology – determine citizens’ evaluations of it? Second, do divergent party evaluations among citizens signal a divide over democracy itself? We trace the three stages of our theoretical argument in the case of Hungary, a particularly flagrant instance of democratic backsliding. We draw on original survey data combining individual‐level measures of partisan affect with information on respondents' vote choice and views of democracy. Using regression models, we assess the emergence of a regime divide structured along a distinct salience of democracy for opposition and government supporters. We complement these quantitative measures with insights on the case study context to further plausibilize our argument.

Our findings lend support to our main assumption that the erosion of democratic standards by the elected government may reinforce affective polarization among the electorate over the very issue of democracy itself. We demonstrate the existence of a government–opposition divide when it comes to voters' evaluations of other parties and show that liberal democratic attitudes form the main dividing line between government and opposition supporters. We also confirm our expectation that vote intention moderates the effect of democratic attitudes. We further unpack the observed patterns by placing them into the context of the evolving party competition in Hungary and social mobilization around divergent views of democracy. Overall, our findings point to a potential positive role for partisan affect in contexts of democratic backsliding, with a ‘democratic divide’ allowing opposition groups to unite around their support for democratic norms against the ruling party. We provide a first exploration of the generalizability of our findings beyond the Hungarian case in a separate analysis of the Polish case in the online appendix.

The remainder of this article begins by situating our argument within existing scholarship on affective polarization and specifically its presumed role in democratic backsliding. Next, we set out the stages of our theoretical argument and the hypotheses that guide our empirical analysis. The following section outlines our research design and introduces our case, data, and operationalization. We then present empirical findings from our case study in Hungary. We contextualize our survey‐based results with specific developments on the ground that indicate how deepening partisan affect between the government and the opposition is indeed driven by ongoing democratic backsliding by the ruling party. The final section summarizes our main insights and sketches future research avenues to probe the interactive relationship between democratic backsliding and affective polarization.

Affective polarization, partisan dynamics and democratic backsliding

Affective polarization has attracted growing scholarly attention in recent years. Unlike ideological polarization that describes a growing distance between voters on substantive issues (McCarty, Reference McCarty2019), affective polarization revolves around social identity and the emotional attachment to one's own party along with the simultaneous dislike for out‐parties and their sympathizers (Bernaerts et al., Reference Bernaerts, Blanckaert and Caluwaerts2022; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012). It has been defined as ‘the increasing effect of partisanship on interpersonal affect’ (Dias & Lelkes, Reference Dias and Lelkes2021, p. 2). The bulk of research in this area has studied how deepening partisan identity among voters – and a corresponding dislike for supporters of other parties – divides society into distinct camps (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019; Mason, Reference Mason2015, Reference Mason2016). While the term affective polarization is relational and refers to the gap between in‐ and out‐party feelings, we focus on partisan affect as the dimension that defines the level of affective polarization.

In the face of widespread concern over democratic backsliding, scholars have focused overwhelmingly on establishing how affective divides in the population may facilitate or deepen the erosion of democracy. For one, affective polarization has been associated with partisan bias in evaluations, with voters more willing to accept transgressions by politicians of their own party (Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020; McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Rahman and Somer2018) or rationalizing democratic violations as being in accordance with democratic standards where such behaviour aligns with their political preferences (Krishnarajan, Reference Krishnarajan2023). Moreover, previous studies mention the politicization of democratic norms, such as checks and balances or opposition rights (Kingzette et al., Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021), which may decrease voters' willingness to punish extreme behaviour by politicians of a party they identify with (Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Pierson & Schickler, Reference Pierson and Schickler2020). Finally, affective polarization makes extreme institutional reforms electorally viable, thereby potentially favouring the emergence of ‘closet autocrats’ while leaving citizens uncertain over an incumbent's true intentions (Chiopris et al., Reference Chiopris, Nalepa and Vanberg2024). All these studies tend to take affective polarization as a starting point to examine its effects on various downstream political outcomes, generally expecting a broadly negative impact on democratic quality.

Regarding its specific relationship to democratic backsliding, affective polarization is held to represent a risk to the democratic system (Reiljan, Reference Reiljan2020), as intense inter‐party animosity may favour democratic violations by the incumbent party or coalition and tolerance for such behaviour on the part of its supporters. McCoy et al. describe this process as one of ‘pernicious polarization,’ whereby the division of societies into mutually distrustful ‘us versus them’ camps can ultimately result in ‘democratic erosion and collapse' (McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Rahman and Somer2018, p. 35). Examining the macro‐level relationship between affective polarization and democratic backsliding empirically, Orhan (Reference Orhan2022) argues that affective polarization is key to driving support for undemocratic politicians by promoting cynicism, intolerance and blind partisan loyalty. Drawing on cross‐sectional data from the V‐Dem liberal democracy index, he shows that an increase in affective polarization is associated with the likelihood of democratic backsliding in the form of decreasing accountability, individual liberties and deliberation. At the same time, he acknowledges that his demonstration is based on aggregate rather than individual‐level data and the causal direction of the relationship thus remains open to interpretation (Orhan, Reference Orhan2022, p. 724).

We adopt the reverse perspective, suggesting that affective polarization may not only foster democratic backsliding but could also, inversely, be the outcome of an extended episode of democratic backsliding that drives a growing divide among citizens over democracy itself. In the following, we spell out the theoretical rationale for viewing the relationship as running also in this opposite direction, from democratic backsliding towards a deepening of partisan affect among citizens.

Theorizing an emergent regime divide around democracy

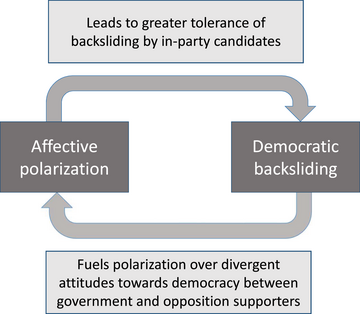

We propose a novel perspective on the relationship between affective polarization and democratic backsliding. Importantly, we do not contest previous studies that view affective polarization as contributing to democratic backsliding. Instead, we suggest that the relationship may be a two‐way one, whereby affective polarization may promote tolerance for backsliding just as backsliding may foster affective polarization. Specifically, we suggest that for citizens who prioritize liberal democratic values, a governing party that violates democratic norms and its supporters may become unacceptable. In turn, they may find other opposition parties and their supporters more acceptable, even when they disagree on policy or ideological grounds. In a nutshell, we submit that democratic backsliding may foster deepening partisan affect among citizens that eventually amounts to what we term a ‘democracy divide’. Figure 1 provides an overview of the circular relationship we expect between democratic backsliding and affective polarization.

Figure 1. Theoretical relationship between affective polarization and democratic backsliding.

Given the ample literature addressing the linkage from affective polarization to democratic backsliding that we discuss above, we focus our theoretical discussion on the reverse direction. We develop our argument in three stages. To begin with, we theorize the emergence of an affective divide between government and opposition parties and their supporters. We then address how we expect the role of liberal democratic values to mediate this relationship. Finally, we explain how partisan preference may moderate the effect of democratic values on affective dislike towards the governing party and its supporters. Ultimately, we argue that democratic backsliding, by increasing the salience of voters’ democratic preferences, can lead to affective polarization around democratic values themselves, uniting opposition supporters in defence of democracy despite their ideological differences.

A new regime divide

Theoretically, our argument holds that undemocratic forms of government can structure political competition and foster a divide grounded in citizens' attitudes towards democracy. Such divergent democratic preferences have been shown to represent an important electoral divide, particularly in new democracies, where ‘mass electorates are polarized according to their views on democracy and their support for pro‐democratic and antidemocratic parties’ (Menéndez Moreno, Reference Menéndez Moreno2019, p. 3). This ‘democracy divide’ echoes Grzymala‐Busse's (Reference Grzymala‐Busse2001) ‘regime divide’ in the context of post‐communist democratization. Discussing the ideologically incongruous party coalitions often found in the new post‐communist democracies, Grzymala‐Busse points to ‘the persisting conflict between the successors of the pre‐1989 Communist parties and the parties emerging from the Communist‐era opposition’ as the main predictor of coalition formation (Grzymala‐Busse, Reference Grzymala‐Busse2001, p. 85). Concerns over developing a consistent identity and fear of electoral punishment prevented parties from forming policy‐convergent coalitions that would have implied crossing this post‐communist ‘regime divide’.

Adapting this argument to the context of democratic backsliding, we expect a comparable divide to emerge where democratic values as well as divergent evaluations of the state of democracy in the country become highly salient. Accordingly, we suggest that the ongoing erosion of democracy can shape a new regime divide that polarizes evaluations of parties and their supporters around attitudes towards democratic backsliding. Those who feel the government violates democratic norms will be unwilling to cross the government–opposition divide, while government supporters may seek to distance themselves from parties criticizing the government they support as undemocratic.

We focus our argument as well as our empirical analysis primarily on partisan affect among opposition supporters: while governments engaging in democratic backsliding have in many cases consisted of or at least been dominated by a single party, the opposition is often more heterogeneous. In fact, failure to coalesce among the opposition has frequently been identified as a central stumbling block for the defence of democracy (Ong, Reference Ong2022; Selçuk & Hekimci, Reference Selçuk and Hekimci2020) and ideological divides within the opposition may further exacerbate the difficulty of mobilizing jointly against the incumbent. However, we argue that the increased salience of democracy in contexts of democratic backsliding may transcend different ideological dimensions in such a way as to allow opposition supporters to unite against the ruling party, thus restructuring political competition along a new regime divide that concerns democracy itself.

As a first step, we expect to observe a government–opposition divide in feelings towards supporters of other parties: citizens who vote for opposition parties should evaluate supporters of other opposition parties more positively than supporters of the government. Our argument here goes beyond merely establishing negative partisanship (Abramowitz & Webster, Reference Abramowitz and Webster2016, Reference Abramowitz and Webster2018), whereby opposition supporters evaluate the governing party critically. Instead, it is only when we also see positive evaluations of the supporters of (other) opposition parties that we observe the emergence of the expected regime divide. Our first hypothesis thus concerns the formation of a government–opposition divide:

Government–opposition hypothesis

H1: Evaluations of party supporters follow a government–opposition divide.

Our argument echoes research on the role of coalition signals for affective polarization (Wagner & Praprotnik, Reference Wagner and Praprotnik2024) showing that news reports about parties' willingness to enter a coalition decrease affective polarization by reducing the perceived ideological distance between parties. Similarly, Bantel (Reference Bantel2023) and Harteveld (Reference Harteveld2021) enlarge the typical focus on party‐based affective polarization to the notion of broader camps around which partisan affect may be structured. They focus on ideological orientations when distinguishing such distinct camps, for instance, examining respondents' feelings towards the larger group of ‘leftists’ rather than more specifically ‘social democrats’. Adapting this approach to our argument, we contend that camps may correspond to different levels of liberal democratic commitment that distinguish supporters of the ruling party in a backsliding regime from supporters of a range of opposition parties.

Democracy and the regime divide

In principle, an affective divide along government–opposition lines may simply reflect incumbency and resentment among opposition supporters towards those in power. In a second step, we therefore, propose to examine to what extent partisan affect relates substantively to respondents' democratic attitudes. If this is the case, as we suppose, those who value liberal democracy and strongly reject democratic backsliding should exhibit a stronger affective reaction towards the supporters of governing parties that violate democratic norms. Especially when opposition parties jointly object to such violations, we expect this to strengthen affective polarization between a government and opposition block, enabling opposition parties to overcome ideological divisions and to mobilize jointly against the ruling party. We thus theorize the emergence of a new regime divide, whereby issue‐based polarization around democracy fuels an affective divide between government supporters and government opponents.

We expect this dynamic to play out in contexts where democratic backsliding is ongoing and carried out by a dominant ruling party or coalition. The resulting increased salience of democratic attitudes among voters is likely to affect their evaluation of different parties and their supporters, with democratic preferences overriding potential ideological differences among the opposition. We are specifically interested in whether respondents who hold a more liberal understanding of democracy evaluate supporters of the governing party more negatively and, in turn, opposition party supporters more positively, compared to those who care less about liberal democracy. Our second set of hypotheses thus expects respondents' democratic views to shape their evaluations of parties and their supporters.

Democracy hypotheses

H2a: Respondents who have a liberal understanding of democracy feel more negatively towards ruling party supporters.

H2b: Respondents who have a liberal understanding of democracy feel more positively towards supporters of opposition parties.

Overall, we thus examine the interplay between democratic attitudes and partisan affect, exploring how the strength of liberal democratic commitment shapes voters' perceptions of different parties and their supporters. By formulating separate hypotheses for feelings towards the ruling party and the opposition parties, we also once again probe whether the hypothesized polarizing effect of democratic backsliding mostly occurs by creating an out‐group that is loathed or can also occur by uniting an in‐group of otherwise possibly disparate opposition parties.

Partisan dynamics and democratic views

In the final step of our argument, we examine whether vote intentions moderate the effect of a liberal understanding of democracy upon partisan effect. Previous research has shown that partisanship and polarization are often tightly connected, with processes of democratic backsliding increasing both polarization and the strength of partisanship (Laebens & Öztürk, Reference Laebens and Öztürk2021). It therefore makes sense to bring partisanship in as a variable that moderates the relationship we posit between democratic backsliding and affective polarization. Concretely, irrespective of voters' stated commitment to liberal democracy, we do not necessarily expect the effect of a liberal understanding of democracy to be universal. Indeed, a host of studies has provided evidence of partisan‐motivated reasoning (Leeper & Slothuus, Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014; Ward & Tavits, Reference Ward and Tavits2019), including when it comes to evaluations of democracy (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Blais & Gélineau, Reference Blais and Gélineau2007) and democratic violations (Ahlquist et al., Reference Ahlquist, Ichino, Wittenberg and Ziblatt2018; Mochtak et al., Reference Mochtak, Lesschaeve and Glaurdić2021). Hence, an identification with a governing party may bias citizens' perspective, overriding the effect of our democracy hypotheses and leading to continued support for the ruling party.

In turn, we know that perceived intergroup threat tends to enhance partisan affect (Renström et al., Reference Renström, Bäck and Carroll2021, p. 555). Since opposition supporters are more likely to perceive the government and its supporters as a direct threat to their (democratic) interests, we expect the hypothesized effect of liberal democratic commitment upon partisan affect to concern primarily opposition supporters. To capture the differential impact of democratic attitudes on partisan affect for government versus opposition supporters, our last hypothesis thus concerns the moderating effect of vote intention on this relationship.

Partisan hypothesis

H3: Vote intention moderates the effect of a liberal understanding of democracy on feelings towards party supporters.

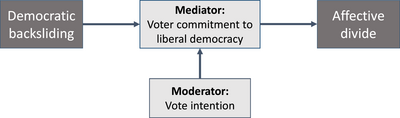

In sum, we theorize a linkage from democratic backsliding towards the emergence of partisan affect along a government–opposition divide that is mediated by respondents' democratic attitudes. We expect this relationship to be primarily driven by opposition supporters, whose commitment to liberal democracy leads them to develop negative feelings towards the ruling party and positive ones towards supporters of opposition parties, ultimately uniting the opposition camp in a joint defence of democracy. Figure 2 provides a visualization of our argument.

Figure 2. Relationship between affective polarization and democratic backsliding.

Research design and data

We deliberately do not put forward a causal argument, but instead seek to develop an alternative theoretical narrative that highlights the two‐way relationship between democratic backsliding and affective polarization. To explore the plausibility of the different stages of our purported reverse link from democratic backsliding towards deepening partisan affect around a democracy divide, we conduct a case study of Hungary as one of the most prominent instances of democratic backsliding that is simultaneously characterized by a high level of societal polarization (Solska, Reference Solska2020; Vegetti, Reference Vegetti2019). To probe our hypotheses, we leverage data from an original survey with a total sample of N = 2000 respondents in Hungary conducted online among a representative sample of the population (based on age, gender, size of town or region and vote choice in the last national election). The survey was fielded by YouGov's partner in Central‐Eastern Europe, the Warsaw‐based market research company Inquiry, between December 2021 and January 2022, a few months ahead of the parliamentary elections held in April 2022 that confirmed a two‐thirds majority for Fidesz in its fourth consecutive mandate. Our survey was thus carried out in the context of long‐standing democratic backsliding that we expect to shape the salience of democratic norms as a core concern for opposition voters.

We pre‐registered the Hungarian study before fielding the survey. We later amended the pre‐registration with a plan for an additional study in Poland based on secondary data collected previously by one of the authors. Due to space constraints and some differences regarding how our variables were measured in the second case, we present the findings from the Polish study in the online appendix.Footnote 1

Empirical strategy

As a dependent variable, we draw on evaluations of party supporters based on a feeling thermometer. Feeling thermometer scores are frequently used to operationalize affective polarization. However, we focus on partisan affect measured as the evaluation of the supporters of individual parties. We choose this approach to avoid the complications measuring affective polarization in multi‐party systems implies compared to bipartisan contexts (Reiljan, Reference Reiljan2020; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021). Besides, certain particularities of our case studies make classical measures of affective polarization less meaningful.Footnote 2

To test the government–opposition hypothesis (H1), we descriptively compare the distribution of feeling thermometer scores for each party among opposition supporters, excluding the party for which a respondent voted. Footnote 3

To test the democracy hypotheses (H2a and H2b), we estimate regression models predicting the support for each party. Here, we implement the following models for each of the dependent variables:

![]()

where

-

•

is a factor measuring democratic attitudes from a battery of questions. We use a factor constructed from four questions from the European Social Survey which we preregistered and that capture liberal democracy as the combination of electoral democracy with a liberal component (Ferrín & Kriesi, Reference Ferrín and Kriesi2016) (see Table A3 in the online Appendix).

is a factor measuring democratic attitudes from a battery of questions. We use a factor constructed from four questions from the European Social Survey which we preregistered and that capture liberal democracy as the combination of electoral democracy with a liberal component (Ferrín & Kriesi, Reference Ferrín and Kriesi2016) (see Table A3 in the online Appendix). -

•

is respondents' vote intention in the next election, simplified into government, opposition and non‐voters.

is respondents' vote intention in the next election, simplified into government, opposition and non‐voters. -

• A range of control variables is included: respondents' gender, age, economic situation, left‐right position and political interest. Detailed descriptions are included in Table A5 in the online Appendix.

To test our partisan hypothesis (H3), we add an interaction term between the liberal democracy item and the ![]() variable.

variable.

Robustness checks

We pre‐registered several alternative specifications: given left and right are used differently in Central‐Eastern Europe, we test a measure differentiating economic and cultural left‐right positions. Similarly, we also include a more complex party variable, including vote intention in the next election instead of the simplified government–opposition measure. Finally, we replicate the main models excluding respondents who stated that they voted for the party that is used as a dependent variable. This provides a more conservative estimate of the evaluation of in‐ and out‐group evaluations for a coalition beyond the party which respondents favour.

Results

Before delving into the specific survey results on partisan affect and democratic attitudes in Hungary, we explore attitudes towards democracy over time. Our argument holds that democratic backsliding may lead to a deepening of affective polarization around democratic attitudes. By examining the evolution of democratic attitudes over a longer period, we seek to contextualize the snapshot insight provided by our survey data collected at a single time point.

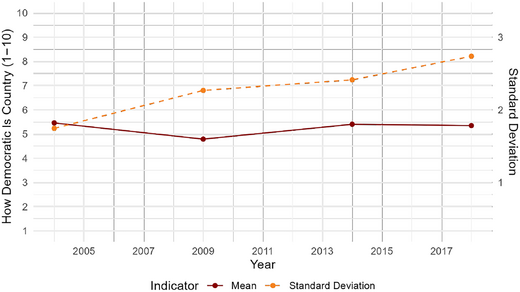

To this effect, Figure 3 shows the over‐time development of responses to the question of how democratic citizens think their country is. At first sight, change is limited with a largely stable average hovering around the middle of the scale. This aggregate perspective, however, masks an underlying polarization of attitudes: The dashed line in Figure 3 shows the standard deviation of these responses, which speaks to the widening gap in citizens' assessments: the standard deviation increases from a rather low level in the early 2000s to a much higher level at the latest available data point in 2018. These patterns indicate an increasing divergence in citizens' evaluations of their country's democratic performance and are in line with our assumption that democratic backsliding eventually contributes to a growing divide between citizens that is organized around views of democracy. Against this backdrop, we further explore the shape and depth of this divide in Hungary drawing on original survey data. We begin by providing a brief overview of the electoral and party systems to discuss how these contextual factors may affect the shape of party competition and partisan affect, and then move on to evaluating the three stages of our theoretical argument in light of our empirical data.

Figure 3. Time series of ‘How democratic is your country?’ question in Hungary, drawing from the World Values Survey, European Values Survey and International Social Survey Programme surveys. Rescaled to a 10‐point scale where the original scale was 11 points. Left scale: mean (red, solid line), right scale: standard deviation (orange, dashed line).

Hungary and the democratic divide

Democratic backsliding in Hungary began with the return to power of Fidesz in 2010. Meanwhile in its fourth consecutive mandate, Fidesz has used its two‐thirds majority to systematically reshape Hungarian politics, undermining judicial independence, media, and academic freedom, and ultimately the electoral process itself (Ágh, Reference Ágh2016; Krekó & Enyedi, Reference Krekó and Enyedi2018). The duration and depth of democratic backsliding in Hungary make it an ideal context to explore the reverse relationship between democratic backsliding and affective polarization that we posit as our theoretical argument.

The Hungarian electoral system – which allocates the majority of seats in single‐member districts – has strong majoritarian tendencies that the Fidesz government further increased via an electoral reform in 2012 (Tóka, Reference Tóka2014). This creates structural incentives for parties to cooperate. At the same time, in light of the considerable fragmentation and ideological diversity of the opposition, Hungary represents a rather hard case for such a regime divide to emerge. For one, despite their ideological proximity the opposition groups on the left are fragmented into different smaller parties (Várnagy & Ilonszki, Reference Várnagy and Ilonszki2018), which represents a hurdle to their joint mobilization. Following Fidesz' victory at the 2009 elections to the European Parliament, the traditional left saw a critical drop in popular support (Ágh, Reference Ágh2015) that translated into significant divides within the left opposition (Gessler & Kyriazi, Reference Gessler and Kyriazi2019; Tóka & Popa, Reference Tóka and Popa2013) and the creation of several new leftist parties in subsequent years, resulting in a fragmentation of the left. Most notably, there are differences between left‐wing parties whose representatives have previously held government office (Hungarian Socialist Party MSZP, Democratic Coalition DK) and those who were never in power.

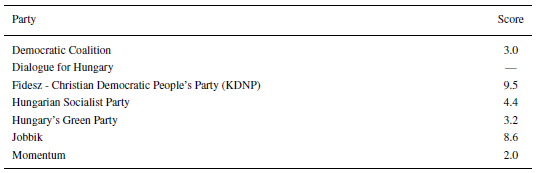

Besides, in addition to its ideological distance from the remaining opposition parties on the left‐right scale, the far‐right Jobbik scores considerably lower than the left parties on democratic commitment. Table 1 shows the democracy scores for the different Hungarian parties, indicating a clear split between Fidesz and Jobbik on the one hand, and leftist parties on the other.

Table 1. Hungary democracy scores (Chapel Hill Expert Survey ‐ 2019)

Note: Average expert rating of party preference for civil liberties (0) versus law and order (10) (CIVLIB_LAWORDER).

Although Jobbik has undergone a process of moderation in the past years (Borbáth & Gessler, Reference Borbáth and Gessler2023), the party's radical right orientation may lead its evaluations by voters to be subject to unique dynamics (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2022). Specifically, its critical stance towards democracy and liberal institutions (Kyriazi, Reference Kyriazi2016; Pirro, Reference Pirro2016; Krekó & Juhász, Reference Krekó and Juhász2018; Pytlas, Reference Pytlas2017) may override potential in‐group feelings for citizens who value liberal democracy. Despite the hypothesized in‐group effect, the fragmentation and ideological breadth of the opposition thus lead us to expect to find considerable divisions among the opposition parties. Hence, in line with our pre‐registration, when interpreting the results we evaluate our hypothesis both including and excluding Jobbik.

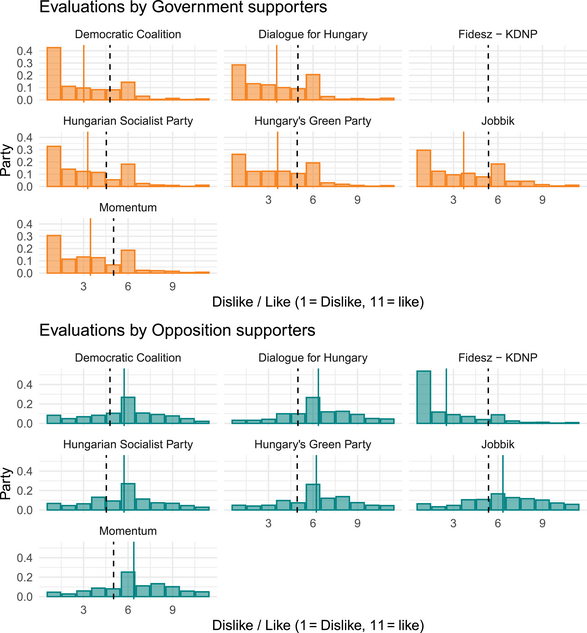

A new regime divide

We begin by examining the support for specific parties by government and opposition supporters. Here, we expect to see an affective divide separating the government from opposition supporters. As shown in Figure 4, this is indeed the case: government and opposition supporters in Hungary differ starkly in their evaluations, clearly highlighting the entrenchment of the government and opposition camps in Hungary: government supporters in the upper panel rate all opposition parties decidedly more negatively than the population mean (dashed line) does. Judging the supporters of each opposition party, between just above a quarter (Green Party) and 42 per cent (Democratic Coalition) of all prospective Fidesz voters select the most extreme dislike score for opposition supporters. This is mirrored by opposition supporters' dislike of Fidesz: here, the gap between the opposition supporters' mean evaluation of Fidesz and the population average (including opposition supporters) amounts to almost 3 points on an 11‐point scale. More than half the opposition supporters select the most extreme dislike category for Fidesz, while this share is around or below 6 per cent for any of the opposition parties.

Figure 4. Evaluations of parties by vote intention (excluding intended vote).

Given that the literature suggests voters tend to voice more moderate opinions when asked about the supporters of other parties (Druckman & Levendusky, Reference Druckman and Levendusky2019), this amount of dislike is momentous. It provides clear support for our government–opposition hypothesis: opposition voters evaluate Fidesz significantly more negatively but all opposition parties significantly more positively. The opposite is true for Fidesz voters, who evaluate their own group very positively but supporters of all opposition parties negatively.

While these results are descriptive, they also receive support from regression models predicting the evaluation of supporters of different parties by vote intention, compared to a baseline of undecided and non‐voters. We include these results in the online appendix (Table A6). These regression results also hold when we consider our preregistered robustness checks of alternative left‐right measures (Table A9 in the online appendix), a complex party measure (Table A12 in the online appendix) and when we exclude evaluations of the party each respondent intends to vote for (Table A15 in the online appendix). A specification without non‐voters and undecided voters is included in Table A20 in the online appendix. Although there is heterogeneity between the supporters of different opposition parties, the clear government–opposition divide remains visible in all these specifications.

Democracy and the regime divide

Having established the size of the regime divide, we now turn to its content. According to our theoretical argument, voters' relative commitment to liberal democracy should shape their attitudes towards different groups of party supporters. Specifically, we expect respondents who show greater support for liberal democracy to feel more negatively towards ruling party supporters and more positively towards supporters of opposition parties. Table 2 presents regression models that predict the evaluation of the supporters of different parties. The independent variables are support for Fidesz and the opposition compared to a baseline of undecided voters. To assess whether the divide we study is substantively about democracy, we include support for liberal democracy, measured as described in the Research Design section. Given the difficulty of accurately capturing support for democracy via traditional survey items, our measure of liberal democratic commitment is heavily skewed with supporters of all parties mostly considering all items as important (Figure A5 in the online appendix). This is also visible from the distribution of the raw variable (see Figure A4 in the online appendix). The results are mostly robust to an alternative measure that considers the number of items from the democracy scale that respondents score with the highest value (see Table A18 in the online appendix, all statistically significant coefficients remain in the same direction, although the coefficients for DK and the Hungarian Green Party LMP lose significance).

Table 2. Regression results democracy model Hungary (baseline: undecided voters)

Note: Controls included for gender, age (categorical), political interest, economic status and left‐right position.

By including support for liberal democracy in the models, we seek to estimate how liberal democratic commitment affects the evaluation of different party supporter groups (democracy hypotheses). Again, the models mostly confirm our expectations: democratic attitudes have a sizeable and significant negative effect on evaluations of Fidesz voters, whereas they have a positive effect on the evaluations of supporters of most opposition parties. Evaluations of Jobbik and MSZP supporters are notable exceptions: the effect of democratic attitudes on the evaluation of Jobbik supporters is not significant and slightly negative, compared to a slightly positive but insignificant effect on MSZP supporters. Moreover, the effect on supporters of the Democratic Coalition (DK) is only significant at the p < 0.05 level and loses significance in some of our alternative specifications in the online appendix (see Tables A10 and A16, but not A13 and A21). These caveats are, however, in line with our pre‐registered expectations: given its political programme and right‐wing ideology, we suggested Jobbik may be excluded from the ‘democratic divide’. Similarly, we assumed that the former governing parties MSZP and DK may be more divisive.

Partisanship and democratic views

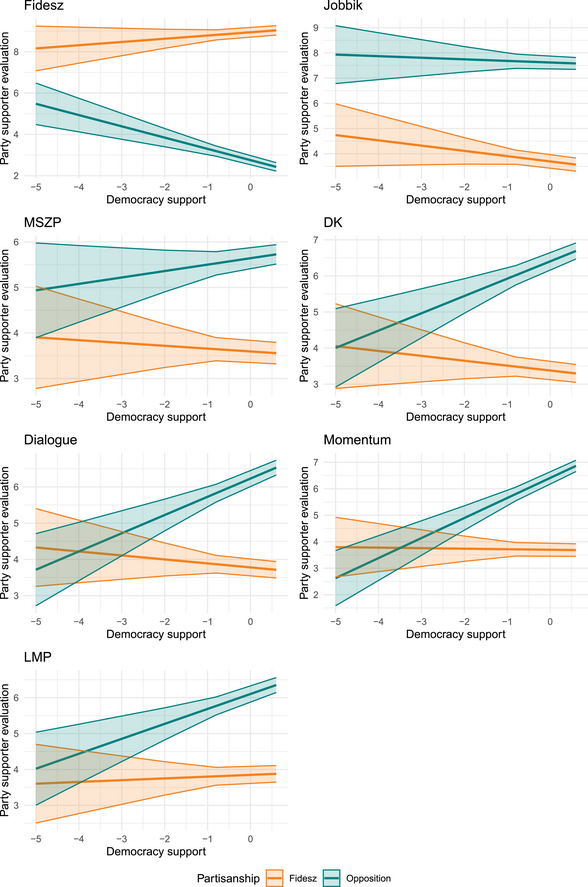

In a third step, we evaluate to what extent vote intention moderates the effect of democratic attitudes upon partisan affect. We expected the effects of liberal democratic attitudes to be restricted to in‐camp evaluations by opposition supporters and did not expect the same effect of democratic attitudes for Fidesz voters, since the incumbency of their preferred party is likely to weaken any concerns around democratic violations. To probe this third stage of our argument, we interacted the liberal democracy scale with the indicator for government/opposition support. As the raw coefficients of interaction models with factor variables are difficult to interpret, we report the full model in the online appendix (Table A8)Footnote 4 and plot the interaction effects for each party in Figure 5. Here, the y‐axis plots the feeling thermometer scores for each party with the x‐axis showing the variation in democratic attitudes. The two lines represent the different partisan groups included in our previous models (prospective opposition voters and Fidesz voters).

Figure 5. Interaction effect of party choice and democracy attitudes in Hungary.

We focus first on how prospective opposition voters evaluate the supporters of different parties, dependent on their level of support for liberal democracy. We find a negative effect of liberal democracy on evaluations of Fidesz supporters that contrasts with a positive effect of liberal democracy on the evaluations of most opposition party supporters among prospective opposition voters. This effect is sizeable and significant for DK, Dialogue, Momentum and LMP. In contrast, the effect is very weak and – in the case of Jobbik – slightly negative for evaluations of Jobbik and MSZP voters. This pattern is again broadly confirmed by our robustness checks included in the online Appendix and is in line with our assumptions since we expected the in‐party bonus of democracy‐affirming opposition voters not necessarily to extend to the right‐wing Jobbik party.

For Fidesz voters, we do not find a positive effect of support for democracy on evaluations of opposition party supporters. Specifically, we find a very small positive effect on evaluations of Fidesz supporters and small negative effects on the evaluation of most opposition parties with the exception of LMP. Given the very small effect sizes, this leads us to conclude that, as expected, how Fidesz voters evaluate the supporters of (other) parties is largely unaffected by their support for liberal democracy.

The sequencing of democratic backsliding and affective polarization in Hungary

Our findings in Hungary are in line with our expectations regarding the emergence of a ‘democracy divide’ between government and opposition supporters against the backdrop of deepening democratic backsliding. We find a clear affective divide between Fidesz supporters and those supporting the opposition, a significant effect for democratic attitudes shaping respondents' attitudes towards different parties, and an interaction between such attitudes and vote intention in the expected direction.

At the same time, the snapshot nature of our survey data does not allow us to address the temporal sequencing between democratic backsliding and affective polarization. In contrast to earlier studies that tend to focus on the impact of affective polarization on democratic backsliding, we posit a two‐way relationship between the two phenomena, whereby a deepening of democratic backsliding can foster the emergence of partisan affect articulated around the very threat to democracy that leads otherwise ideologically divergent opposition parties to band together against the ruling party. We draw on case study literature to illustrate the plausibility of this reverse relationship.

After the first period of government from 2002 to 2006, Fidesz and its party leader Viktor Orbán used the intervening mandate of socialist rule to mobilize voters via the Civic Circles Movement that connected right‐wing grassroots networks to hierarchical organisations in ways that enabled the party Fidesz to forge close ties with civil society and consolidate its core electorate (Greskovits, Reference Greskovits2020). This deep anchoring within civil society enabled Fidesz to build the social and political capital that has been key to ensuring the party's resilience in power.

Already shortly after his re‐election in 2010, Viktor Orbán used his two‐thirds majority in parliament to initiate sweeping constitutional changes that severely undermined judicial independence. Yet opposition parties initially proved largely incapable of preventing further landslide victories by Fidesz in subsequent local, national, and European Parliament elections due to their pervasive fragmentation in terms of both ideology and strategy (Greskovits, Reference Greskovits2015, p. 34). The opposition's approach began to shift only following Fidesz' third successive victory in national elections, which represented a tipping point. In the October 2019 local elections, Gergely Karácsony, the candidate of the left‐wing party Dialogue, won the Budapest mayoralty and candidates fielded jointly by united opposition parties secured majorities in 10 out of 23 urban centres in Hungary (Kazai & Mécs, Reference Kazai and Mécs2019; Solska, Reference Solska2020).

Despite the swift nature of democratic backsliding in Hungary, the emergence of a ‘democracy divide’ that enables the joint mobilization of the opposition across ideological divides thus appears to be shaped both by the degree but also the duration of democratic backsliding. Joint mobilization by the opposition culminated in the latest parliamentary elections in April 2022, which saw all opposition parties eventually rally behind a single candidate (Tóka & Popescu, Reference Tóka and Popescu2021). Although electoral coalitions had existed in previous elections (Kovarek & Littvay, Reference Kovarek and Littvay2022), the 2022 coalition was broader than any before and included closer cooperation, with joint opposition candidates fielded across all 106 electoral districts. Most importantly, it was articulated explicitly around a common desire to defend democratic values against the ongoing deepening of democratic backsliding under the Fidesz government.Footnote 5

Our survey findings map neatly onto the emergence of this joint electoral coalition in Hungary, thus providing support to our contention that the deepening of democratic backsliding under a ruling party may contribute to the emergence of an affective divide that enables otherwise ideologically heterogeneous opposition parties to come together in a joint defence of democracy. Eventually, the coalition candidate failed to secure a majority against Fidesz against the backdrop of Russia's aggression on Ukraine that saw the incumbent appeal to stability resonate with the electorate. Still, we maintain that the ability of a highly heterogeneous opposition to mobilize jointly with a view to overturning on autocratising ruling party lends credence to our intuition that democratic backsliding may fuel affective polarization around a ‘democratic divide’.

Discussion

Our paper set out to assess whether, besides being a contributing factor to democratic backsliding, affective polarization may also be a consequence of a protracted episode of backsliding. Specifically, we expected to find growing partisan affect related to citizens' divergent evaluations of democracy in contexts of backsliding, whereby government and opposition supporters would become increasingly divided – and the opposition internally united – over their distinct appreciation of democratic quality. Positing three complementary dimensions of such an emerging ‘regime divide’ around democracy itself, we suggested that the strength of liberal democratic commitment may drive growing partisan affect between supporters of the government and the opposition ‘camp’. Besides, we expected the effect of democratic attitudes to be conditional upon partisan camp membership, with the democracy effect primarily present for opposition supporters.

To probe the empirical plausibility of our assumptions, we examined the three dimensions of our theoretical argument in a context in which initial democratization was already characterized by a ‘regime divide’ related to the communist past of certain parties, whereby association with or opposition to the former communist system was key to shaping party coalitions as well as electoral punishment (Grzymala‐Busse, Reference Grzymala‐Busse2001). Similar to this post‐communist ‘regime divide,’ we argued that democratic backsliding may shape a new regime divide that polarizes evaluations of parties and their supporters around attitudes towards democracy and democratic backsliding.

Our findings in Hungary lend support to the theorized reverse relationship between democratic backsliding and affective polarization. We find a strong affective dislike of the ruling party among opposition supporters as well as signs of the emergence of a more united group of opposition parties in spite of the prevalent party fragmentation and ideological divisions within the opposition itself. We complement the quantitative findings from our main case study with additional qualitative evidence that supports our temporal argument, which holds that democratic backsliding may also function as a driver, rather than merely the result of, affective polarization. We are cautious in interpreting our findings since the observed patterns may also be shaped by the majoritarian nature of the Hungarian electoral system having forced opposition parties to band together. At the same time, our findings on the relevance of support for liberal democracy indicate that opposition parties band together not merely out of opportunistic motives but because their supporters view each other as allies against an undemocratic government. This interpretation is also supported by the dynamics of mobilization employed by the ruling party and the opposition alike. Ultimately, this process appears to have shifted the Hungarian multi‐party system towards an increasingly bipolar structure, with opposition supporters uniting around their opposition to the government and its democratic violations across ideological divides.

This effect is not visible to the same extent in Poland, as we show in the online appendix. Here, democratic attitudes only seem to shape the condemnation of anti‐democratic actors, without forging a coherent in‐group among supporters of opposition parties. Instead, our findings indicate a more classical divide between the two main parties that have alternated in power over the past years. Opposition supporters seem to be united in their dislike of the government, but less clearly united across opposition party lines. We explain this pattern by the different depth and duration of the backsliding process in contrast to Hungary: since Poland finds itself at a comparatively earlier stage in the backsliding process, group identities appear less strongly structured by democratic attitudes and distinct partisan preferences persist among opposition supporters. This difference indicates that the very duration of the backsliding process may be instrumental in forging links between opposition parties across ideological divides in order to jointly confront a government that is dismantling democratic standards.

Overall, our empirical analysis thus suggests that besides affective polarization driving processes of democratic backsliding, the deepening of such processes may in turn forge affective polarization in a way that allows opposition supporters to overcome ideological barriers to join forces in defence of liberal democracy itself. We show that citizens – or, more specifically, opposition supporters – who value democracy tend to evaluate their in‐group more favourably but out‐groups more negatively. As expected, we find some partial exceptions to this pattern, particularly concerning the populist right‐wing Jobbik party in Hungary and the Confederation party in Poland, which are less integrated into the opposition block. We view these divergent outcomes as the result of these parties' distinct stances on democracy itself, rather than the more general left‐right ideological differences that characterize the opposition camp.

Since our data can only offer a snapshot insight into the state of democracy‐related partisan affect, we are unable to draw any definitive conclusions about the causal directionality of the relationship. Besides the short case study narrative we provide to contextualize our survey findings in Hungary, two additional observations support the plausibility of a reverse relationship between democratic backsliding and affective polarization. First, our descriptive findings of the polarization of democratic evaluations over time indicate that the process of backsliding itself contributes to a deepening partisan affect related to opposing views of the quality of democracy. We see that views of the state of democracy effectively diverge over time, with a growing share of deeply dissatisfied citizens matched by a comparable increase of respondents indicating high levels of satisfaction with the state of democracy in their country (see Figure 3).

Second, the fact that the affective divide between government and opposition supporters is clearer in Hungary, where backsliding is more long‐standing and entrenched than in Poland and democracy therefore more salient in the eyes of the voters, lends further lends credence to our interpretation of a reverse relationship between democratic backsliding and affective polarization. Previous research on the emergence of new cleavages suggests that these undergo different stages, shifting from being ‘embryonic’ and of concern to only a limited number of voters, to becoming a more general theme of mobilization right up to reaching maturity, when a new cleavage mobilizes a relevant portion of the electorate and remains stable across elections (Emanuele et al., Reference Emanuele, Marino and Angelucci2020). Arguably, whereas the democratic divide is a clear mobilizing issue in Poland, it has reached full maturity in the Hungarian context with Fidesz in its fourth consecutive mandate.

Conclusion

Our paper theorizes and empirically explores a positive linkage between democratic backsliding and deepening partisan affect that restructures the political landscape along a ‘regime divide’ over democracy itself. Our research speaks to several ongoing debates around the nature and drivers of affective polarization and its relationship to democratic backsliding.

First and foremost, we complement existing accounts of the negative effect of affective polarization upon democratic backsliding with a more positive reading, whereby democratic backsliding may drive an affective divide around democracy that helps unite an ideologically diverse opposition camp in defence of democracy. By highlighting the unifying effect of joint concern for democracy for the opposition in backsliding regimes, we thus propose a different lens through which researchers can analyse the macro‐level relationship between both processes. We hasten to reaffirm that we do not contest potential effects of affective polarization on tolerance for democratic backsliding. Instead, we argue that we may also interpret affective polarization as a consequence of a government's undemocratic behaviour. Specifically, we posit a mutually reinforcing relationship between affective polarization and democratic backsliding, whereby affect‐based tolerance of democratic violations by government supporters leads to a polarization of party evaluations around views of liberal democracy, eventually producing a regime divide that unites an otherwise disparate group of opposition parties in their rejection of the incumbent and their supporters due to concerns over democracy. In this sense, our findings speak to the relevance of ‘camp‐based’ affective polarization (Bantel, Reference Bantel2023; Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2021) that shifts in response to political outcomes and can unite broader groups of party supporters in opposition to a common out‐group.

The presence of such a two‐way dynamic between democratic backsliding and affective polarization may alter our evaluation of the role affectively polarized electorates play in contexts of democratic backsliding. By offering a positive view of partisan affect as a consequence of democratic backsliding, we challenge the perspective that polarization generally has a pernicious effect on democratic quality (Somer et al., Reference Somer, McCoy and Luke2021, p. 16). Instead, we contend that when affective polarization is a response to the degradation of democracy, it may actually favor the exclusion of anti‐democratic actors and increase voters' and party elites' willingness to bridge ideological differences in defence of democracy. Opposition coalitions – which may successfully compete with incumbents engaged in democratic backsliding – may thus become more likely to emerge when citizens are united by a ‘democratic divide.’ This kind of dynamic also appears to be present in the Turkish case (Selçuk & Hekimci, Reference Selçuk and Hekimci2020; Somer & Enyedi, Reference Somer and Enyedi2023).

Our empirical discussion focused on case studies from the post‐communist region, where the existence of a ‘regime divide’ related to parties' status during the democratic transition has previously been demonstrated (Grzymala‐Busse, Reference Grzymala‐Busse2001). This common historical legacy may be thought to limit the generalizability of our argument to other contexts. Several reasons lead us to consider our findings to be relevant beyond the post‐communist region. Most crucially, we argue that multi‐party settings with high levels of fragmentation and ideological heterogeneity among opposition parties more generally represent a significant hurdle for a joint mobilization of opposition parties around the defence of democracy. The fact that we find clear signs of this dynamic in Hungary and, more tentatively, Poland, makes us confident that our findings hold wider significance for our understanding of the societal dynamics resulting from democratic backsliding. Most notably, societal polarization represents a trend that extends well beyond the specific post‐communist region (Carothers & O'Donohue, Reference Carothers and O'Donohue2019; McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Rahman and Somer2018; Somer et al., Reference Somer, McCoy and Luke2021), with a democracy‐authoritarian divide also shown to exist in Tunisia (Farag, Reference Farag2020) and Chile (Bonilla et al., Reference Bonilla, Carlin, Love and Méndez2011). In light of the spread of democratic backsliding across different world regions, it seems plausible to expect similar dynamics of affective polarization around democratic attitudes to emerge in different geographic contexts. We are, therefore, confident that our argument regarding the two‐way relationship between affective polarization and democratic backsliding holds insights that are relevant well beyond our cases. The extensive debates around the attack on the US Capitol on 6 January 2021 are a case in point: partisan polarization in the United States increasingly mirrors a divide over democratic attitudes.

An important limitation of our analysis concerns its cross‐sectional nature that is able to address temporal dynamics only in a contextualizing fashion. This is true also for most existing studies that focus on the impact of affective polarization upon democratic backsliding (Orhan, Reference Orhan2022; Somer & McCoy, Reference Somer and McCoy2018). In the future, researchers should further probe the relationship between democratic backsliding and affective polarization by adopting experimental or panel approaches that allow them to tease out the causal relationship between these two processes. Such evidence would be key to a comprehensive and dynamic understanding of affective polarization in contexts of democratic backsliding. Our study provides a first indication of the mechanisms that may underpin such processes.

Finally, our findings highlight the importance of studying the interplay between mass‐level affective polarization and elite‐level dynamics. While we point to elite‐level ideological polarization as an initial obstacle preventing parties from coming together to challenge an authoritarian‐leaning incumbent, a lack of mass support for such an ideologically heterogeneous coalition may similarly prevent joint mobilization by the opposition. In addition, our findings raise the question of the effect of political elites and media on affective polarization: although we have not investigated why attitudes towards democracy matter for affective polarization, the strength and character of the long‐standing political conflict around the issue of democracy in Hungary (Gessler & Kyriazi, Reference Gessler and Kyriazi2019; Gessler, Reference Gessler2024) as well as in Poland is a potential explanation. Anti‐pluralism has been shown to represent a key predictor of democratic backsliding (Medzihorsky & Lindberg, Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024), and such discourse has been part and parcel of elite appeals throughout the democratic backsliding processes in Hungary and Poland (Kim, Reference Kim2021; Wunsch forthcoming: Ch. 5). That is, when parties mobilize voters' democratic attitudes in election campaigns, these attitudes can shape how voters evaluate – and eventually choose among –parties. Future studies would do well to further probe the interplay between elite discourses on democracy and voter attitudes towards democracy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback. We are grateful for input on previous versions of the paper by audiences at the ECPR Joint Sessions 2022, EPSA 2022, APSA 2022, ECPR 2023 the pre‐publication workshops at University of Zurich and Sciences Po CEE, the Affective Polarization and Democracy workshop, members of the EUP group, as well as by Dan Kelemen, Markus Wagner, Sarah Engler, Eelco Harteveld, Laurence Brandenberger, and Jan Rovny.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A1: Poland Democracy Scores (CHES ‐ 2019).

Figure A1: Time Series of “How Democratic is your Country?” question in Poland, drawing from the WVS, EVS and ISSP surveys.

Figure A2: Evaluations of parties by vote intention (excluding intended vote)

Table A2: Regression results democracy model Poland (baseline: undecided voters)

Figure A3: Interaction effect of party choice and democracy attitudes in Poland

Table A3: Factor loadings for items on a single liberal democracy factor

Table A4: Factor loadings for items on two democracy factors

Table A5: Definition of variables

Figure A5: Factor distribution of democracy conceptions by party, ESS (HU)

Figure A6: Distribution of democracy conception items, WVS adapted (PL)

Figure A7: Factor distribution of democracy conceptions by party, WVS adapted (PL)

Table A6: Statistical Models H1

Table A7: Statistical Models H2

Table A8: Statistical Models H3

Table A9: Statistical Models H1

Table A10: Statistical Models H2

Table A11: Statistical Models H3

Table A12: Statistical Models H1

Table A13: Statistical Models H2

Table A14: Statistical Models H3

Table A15: Statistical Models H1

Table A16: Statistical Models H2

Table A17: Statistical Models H3

Table A18: Statistical Models H2

Table A19: Statistical Models H3

Table A20: Statistical Models H1

Table A21: Statistical Models H2

Table A22: Statistical Models H3

Table A23: Regression results baseline model Poland (baseline: undecided voters)

Table A24: Regression results democracy model Poland (baseline: undecided voters)

Table A25: Regression results model H3 Poland (baseline: undecided voters)

Table A26: Statistical Models H1

Table A27: Statistical Models H2

Table A28: Statistical Models H3

Table A29: Statistical Models H1

Table A30: Statistical Models H2

Table A31: Statistical Models H3

Table A32: Statistical Models H1

Table A33: Statistical Models H2

Table A34: Statistical Models H3

Table A35: Statistical Models H1

Table A36: Statistical Models H2

Table A37: Statistical Models H3