11.1 Introduction: What’s the Problem?

What is the purpose of education? It is a question that remains unanswered and asked perpetually by governments, educators and parents. It is a question related to another – what is the purpose of life? The two are interrelated – one will answer the other. Carl Jung (Reference Jung1962, p. 326) said that ‘as far as we can discern, the sole purpose of human existence is to kindle a light of meaning in the darkness of mere being’. And Viktor Frankl (Reference Frankl1966) talks of grasping the meaningfulness of life in rational terms. So, my manifesto for education attempts to suggest ways in which we philosophise the experience for children and young people; to grapple with big questions and to consider the very point of life. I argue for the need to equip young people with the philosophical tools and critical thinking skills necessary to grapple with the complexities of existence and create meaningful lives for themselves within a rapidly changing world. This involves moving away from traditional, discipline-specific models of education and embracing a more holistic approach that encourages open-ended exploration of fundamental questions, fostering intellectual curiosity, self-awareness and a sense of purpose in life.

Life as a teenager has probably never been easy in any epoch or civilisation. It’s a time of bodily transition, raging hormones and new emotions. It’s also a time for making up one’s mind on what we think of the world and how we fit into it. We question ideas we’ve been fed, rebel against the norm or endeavour to fit in – seeking self-expression or conformity. There’s much to consider, especially as our minds contemplate the big questions of existence that humans have posed – argued and fought over – since time immemorial:

Who am I?

What is life?

Is there something more?

These may seem abstract and peripheral to the immediate matters of domestic life, family disruption, social interactions, exams, dating and so on, but I contend that a teenager’s ability to navigate the challenges of adolescence is affected by the concepts and beliefs one holds about oneself and one’s purpose in life.

In the UK, the Health Foundation suggests that the number of children aged between six and sixteen who have a ‘probable mental health condition’ rose from one in nine in 2017 to one in six in 2021 (Peytrignet et al., Reference Peytrignet2022). Of particular concern is that this included one in four adolescent girls. These are worrying statistics. And it is therefore imperative that we deepen our understanding of, and approach to, the complex underlying causes at work in, what we euphemistically term ‘teen angst’.

In both education and care, we are getting better at delivering appropriate forms of support, therapy and counselling, despite the huge challenges on public finances that is resulting in reduced access to such support. However, if we could identify common contributing factors to the mental illness, perhaps we could do more in the healing? Chapter 10 in this volume refers to the biology of stress, but I am referring to the ways in which we define who we are, how we want to engage in the world and the meaning of both. Could there be preventative mental healthcare? What would it look like? Could an educational experience that has philosophy at the heart of it bring about more articulate – socially, emotionally and intellectually – young people? This manifesto cannot provide answers to all these questions. However, it will endeavour to explore issues that might enable young people to find a deeper sense of purpose and meaning for their lives; to sustain – even inspire – them through the opportunities and challenges that lie ahead.

According to Hill et al. (Reference Hill2010), purpose and meaning are related but are not synonymous. They identify four main types of purpose as follows:

- Prosocial:

Propensity to help others and influence the societal structure

- Creative:

Artistic and creative goals and propensity for originality

- Financial:

Financial well-being, security and worldly attainment

- Recognition:

Desire for recognition and respect

Meaning is generally thought of as a mix of factors, such as proposed by Morgan and Farsides (Reference Morgan and Farsides2009):

- Valuing life:

Seeing life’s inherent value

- Living by principles:

Having a personal philosophy that guides your life

- Purpose:

Having clear goals and intentions

- Accomplishment:

Setting and reaching personal goals

- Excitement in life:

A sense that life is exciting, interesting or engaging

It is almost impossible to capture meaning without considering the broader context of one’s life – and thus also, what happens to us at death. Existential questions about life are intrinsic to the quest for meaning. In The Search for Meaning in Life and the Existential Fundamental Motivations, Alfried Längle (Reference Längle1999) explains that individuals are fundamentally looking for a greater context and values for which they want to live for. Along with the issue of our personal existence is the question of the larger reality in which we find ourselves. Does the universe have a purpose for us? Is there anything beyond to which I am or could be connected that might also bestow direction and meaning to my life?

Furthermore, a major factor in deriving meaning from work, creativity, altruism and service to others is the hope that we leave a legacy, to perpetuate something of ourselves after our demise, something that made a difference. Prosocial purposes not only offer greater happiness in life; they also offer more opportunities for legacy, to pass on wisdom, wealth, opportunity, monuments, projects and so on to the next generation. Extending the impact of one’s actions beyond death – and being appreciated and remembered for them – bestows a greater sense of meaning to them in the present. The question is, What might a prosocial focus look like in schools? How would children manifest this in their daily life as learners, friends, siblings and sons and daughters? and How do teachers make sense of this in their practice, beyond the substantive things they teach?

In this manifesto, I argue that modern education must provide a forum for all young people, at appropriate ages, to engage with such existential questions. If you have ever been in an early years classroom, you will know that children are curious to know what happens when we die. This is not morbid. Instead, could it be that the human condition is in the constant state of seeking and sense-making? Could it be that instead of sanitising and ordering life into easily accepted compartments, we keep the spaces of uncertainty open and alive for rich questioning and deep discussion?

11.2 What to Do about It?

If we accept that finding meaning for one’s life contributes positively to mental well-being and other social aims, we should integrate and develop this endeavour within school life. Marcel Proust is paraphrased to explain that the movement through life and in seeking new landscapes must also include the vital practice of seeing – of having eyes.Footnote 1 I argue that there should be a distinct philosophical project, beyond what we currently offer in the UK in religious education (RE) and personal, social, health and economic education (PSHE). And the subjects and topics for discussion should be objective and neutral. It is not required nor desirable to tell young people what to believe, nor to suggest that they must have something to believe in to find meaning. When it comes to notions of the self, life and reality, the questions and answers must be open. But by helping young people to determine answers for themselves, they may find clarity, enrichment and optimism. My hope, therefore, is that addressing such existential questions will reduce the prevalence and intensity of mental health issues for our younger generation.

11.3 The Philosophical Forum

It is possible to address the question of meaning through the lens of personal and social identity, and their attendant obligations and responsibilities, without considering wider existential contexts. We can discuss prosocial purposes, principles and values in PSHE and RE. And in the UK, the Department for Education says PSHE should cover health, well-being, relationships and how to work and live in society. This is relatively safe and familiar ground for school education. But it is not sufficient for tackling underlying issues of young person isolation, disillusionment and pessimism.

Are the big questions of existence and meaning best left to RE? Certainly, young people may derive benefits and inspiration from exposure to a wide range of religious views and insights. But, RE tends to frame discussions on universal themes within the compartmentalised beliefs and practices of various faith communities. However, considering the diversity of beliefs within the school population, as well as those in the ‘none’ (no religion), or ‘SBNR’ (spiritual but not religious) cohorts, it may be better to brand philosophical exploration of the nature of existence as universal, rather than associated with religion. Hence, my preference is that there should be independent classroom time (without being onerous on the timetable) dedicated to philosophy. Sure, some people (mis)characterise philosophy as a plethora of unsubstantiated ideas that are more confusing than enlightening. But the ability to think philosophically is a powerful tool that can clarify how one regards oneself, one’s life and one’s value.

To think about the meaning of one’s life, one must try to understand what it means to be in the world, to have life and to have an individual identity (Frankl, Reference Frankl1966). These questions then require us to consider if there is a larger picture that, in some way, defines purpose for me. There are two essential topics in this regard: (1) personal existence and (2) reality beyond the here and now. What follows is my thinking about addressing these two topics.

11.4 Personal Existence

What’s the starting point for this exploration? What can I know for certain? Let’s take a step-by-step approach. We start with the statement, and this is followed by the question to problematise the statement.

‘I exist.’

How do I know this?

‘I experience things.’ I see, hear, taste, smell or touch. I feel sensations: sometimes a happy feeling, or hunger, or fear or pain.

‘I think thoughts.’ I am aware of them as they float through my mind when I’m awake, or at night, in my dreams.

My thoughts and dreams may be correct or foolish, but the fact of my having these experiences and feelings is certainly real to me. So real, that I can be convinced that I do exist in the world I see around me; and that I have the privilege of knowing that I do.

This line of thinking in itself can be challenged. For example, strictly speaking, Descartes had to take a number of additional steps and make a number of additional arguments to get to the ‘the world is as I perceive it’ position, namely that God exists, that God is good and that a good God wouldn’t condemn people to live with systematic misapprehensions about the world. The process of philosophical challenge is the process of making better sense of our positionality and purpose in the world. Moreover, an objection might be raised that certain eastern wisdom traditions assert the ultimate non-existence of a personal self. However, within those traditions, the starting point is the same: that, for now, a person believes themselves to be an existent self. Persons suffering Cotard’s syndrome report they believe they may be dead, or not exist. This subjective expression of their detachment from any sense of self still entails the principle that they are the person experiencing a particular delusion of non-existence.

In the West, we credit Descartes for this insight – that I exist as a thinking thing: cogito ergo sum. But the idea is also evident in various meditative traditions going back into antiquity. This conviction that ‘I exist’ can be referred to as a ‘pre-philosophical insight’ or ‘intuition’. It is axiomatic knowledge we possess without having validated it through the epistemologies of philosophy, science or religion. Although in English we use two separate words: ‘I’ and ‘am’, some languages combine them as one unified concept: ‘I-am’ as in Latin, ‘sum’. I cannot separate the truth that I am from the fact that it is I who is doing the being. This leads us to a further realised axiom: that I am the subject of my experiences – it is I who feels, I who sees, I who loves and so on.

These intuitions regarding my personal existence and my capacity to experience life in a feeling way are key components of what we mean by the term consciousness. The phenomenon of consciousness is not easy to explain. However, we know what it is to us. It is what makes us sentient, aware of life around us and of our own existence. My awareness or consciousness belongs to me. It is what makes me, the ‘I’ who experiences my life. It is the ‘me’ who really, really cares about what I do during my life. It is fascinating to contemplate the wonder of our existence, the amazing phenomenon of being alive and sentient. For as long as I can remember it has only been ‘me’, the conscious self, living in this body, watching it grow and morph from a child to an adolescent to an adult. And despite how my thoughts, outlook and personality have evolved over all these years, it has always felt like the same ‘me’ – the prime self as the possessor of sentience – doing the experiencing.

Of course, selfhood can sometimes feel, or be perceived as, impermanent; that one’s ‘future self’ is not really the same as one’s ‘current self’. Perhaps, then, one’s ‘current self’ should not worry about one’s ‘future self?’ – in fact, why do anything other than gratify one’s ‘current self’ in this moment? However, this line of inquiry is unproductive. And a more pressing and more common question arrives from the opposite direction, namely how does the subjective aspect of consciousness remain so permanent in the ever-changing biological environment of our body and brain?

The following is a short summary of current thinking within science and philosophy that explores the question of what gives rise to this sense of being, of life and of sentience that we call consciousness. A question that arises is, Is consciousness a physical phenomenon or something extra-physical? Perhaps, twenty years ago, the matter seemed settled. Neuroscience had made considerable advances over the preceding decades. Nobel laureates like Francis Crick (Reference Crick1994) announced the ‘Astonishing Hypothesis’ that consciousness may be the effect of certain sets of neural activity, the neural correlates of consciousness (NCCs). Yet, even then, he acknowledged that NCCs cannot explain the qualitative or subjective experience of consciousness. He thus failed to meet John Searle’s (Reference Searle2000) challenge that ‘the most important aspects of consciousness that must be accounted for in any explanation are: unified qualitative subjectivity’.

Consider a person observing a woman and her dog out on a walk (as in Koch, Reference Koch2004). In the scene, light is reflected off the pair and enters the observer’s eyes, where it activates the cones and rods located in the retina, sending a set of tiny electrical pulses down the optic nerve. This signal forms a flash of neural connectivity in the visual processing areas of the brain. It is processed by the brain through electrical activity – a flash of charged ions jumping between neurons. So why do we experience such electrical activity as a picture? Where in the brain does image exist? The same question can be raised for other types of sensory experiences. Why does electrical activity in my brain stimulated by movements within my ear produce qualities of sounds in speech or melody? Why do other electrical impulses feel like ‘Oww’? The brain runs on chemical electricity, but we experience life as felt qualities of imagery, sounds, sensations, tastes, smells, pains, pleasures and so on.

We call these felt sensory qualities of our conscious experience by a special term, qualia, to distinguish them from the purely physical properties of the external world. These internal and subjective qualities of our mental perception (qualia) are considered highly problematic for a neural interpretation of consciousness. If everything that occurs within the biological processes of our body and brain can be attributed to our understanding of physics – specifically quantum field theory – then why is it that the specific properties of physics cannot yet account for the properties of our phenomenal experience (such as the qualia of forms and colours)? Is this present-day ignorance due to be solved by subsequent discoveries? Or is it an intractable issue, because mental states are a category of functions and properties distinct from those of physics?

An additional question about this process might be, Why the need to produce such a qualitative image? To function as a stimulus/response system, the brain does not require its data to be formatted as an image. Why do we need to make sense of the image that is presented via the optical nerve? So, who are qualia for? And, who or what is the ‘I’ who is the subjective experiencer of these images? What gives rise to the sense of my being the observer of this image?

In addition to the initial process of the external world stimulating brain activity to create a qualitative image, we might add the question, Who is the observer? Our everyday perception involving the subjective experience of mental states and their qualities cannot be accounted for by anything we have yet discovered in neuroscience, biology or physics. In 1994, philosopher David Chalmers highlighted the challenge of qualia to a physicalist neural-based account of consciousness. He coined a term, now commonly used: the hard problem of consciousness. To this day, it remains hard – so much so that many researchers are forgoing neural theories of consciousness to explore more ‘exotic’ sources, such as quantum physics, information integration and even panpsychism.

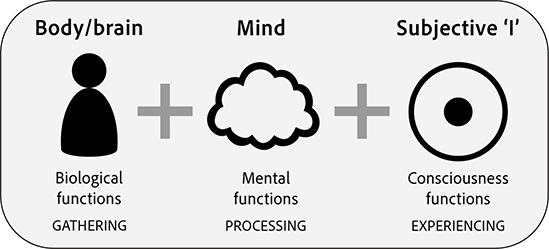

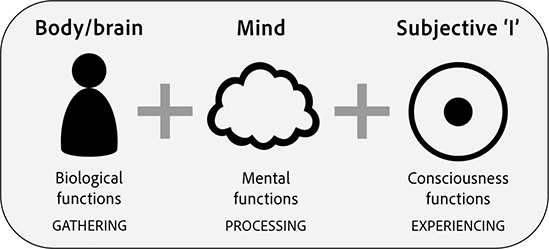

Although the complex question of consciousness has been debated for millennia, there are three essential functions that enable us to, respectively, gather, process and experience information about the world and collectively contribute to our capacity for awareness and sense of identity:

The biological and neural systems of our bodies and brains

The minds that contain our thoughts and qualitative mental states which represent the world to us

Consciousness – the capacity as the subjective ‘I’ experiencing those mental states

Each of us contains these discrete functions that together account for our awareness and interaction with the external world: firstly there is the body and its central processing unit, the brain, which fulfil our requirements as a functional biological organism. Within this, there is the mind, which possesses sensory information as qualia and generates our thoughts and volitional responses. And finally, both functions are distinct from the ‘I’, the conscious being who observes and experiences and expresses its will. To make sense of Figure 11.1, the reader could ask the following: When looking at a view or image, what does one’s body/brain do, what does one’s mind do and what does one’s conscience do? And why is this relevant? When a child engages in a class activity, what does their body/brain do? And what of their mind and conscience? And for teachers, how far do we take into consideration these three aspects?

Figure 11.1 The three functions which compose human awareness and identity.

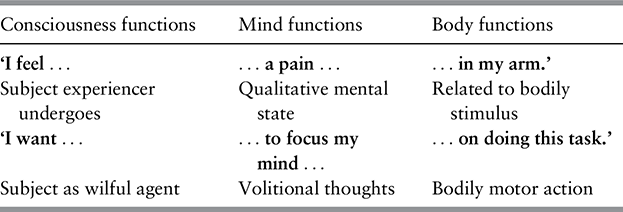

The three-function model maps onto conventional ways of referring to perception and agency. For example let us consider the functions of speech. Table 11.1 demonstrates three functions at work in speech.

| Consciousness functions | Mind functions | Body functions |

|---|---|---|

| ‘I feel … | … a pain … | … in my arm.’ |

| Subject experiencer undergoes | Qualitative mental state | Related to bodily stimulus |

| ‘I want … | … to focus my mind … | … on doing this task.’ |

| Subject as wilful agent | Volitional thoughts | Bodily motor action |

The model is compatible with both physicalist and extra-physical frameworks. It is both scientifically consistent as well as theologically open. It does not adjudicate between the claim that consciousness is a product of the brain, and the claim that consciousness is a property beyond the physical. Advocates on either side may never agree, but there is opportunity to think of new ways to engage young people when both are respected and the opinions and inclinations of the other, knowing that neither has certainty on their side. This, I argue, would provide a much healthier intellectual climate for young people to determine what underpins their belief in life.

11.5 Reality beyond the Here and Now

In considering an education that is fit for the twenty-first century, and the economic, ecological and social challenges we will face, exploring the meaning of our lives within time gets us thinking about the future. Contemplating the status of consciousness in time raises the delicate issue of our future. Is this world all there is? Is our existence and awareness extinguished like a candle at the moment we call death? Or does some aspect of the self persist in a meaningful fashion beyond our body’s physical demise? Are these questions we can ever answer? It seems impossible for humans not to ponder these questions. They matter because our concept of what life is will influence our evaluation of its meaning, value and purpose. This is not an issue of morality, belief or being spiritual. My hope is that we can dissect this question – does conscious life end or continue after death – as an open philosophical proposition keeping aside religious connotations.

To do so, we must establish a neutral forum, clarifying that both the question and its possible answers are open and undecided. Nothing has been determined by any discipline to tell us categorically what consciousness is, where it comes from or what its future may be. So, at school, we should not convey a bias towards one conclusion or another. Many young people are affected by pronouncements from people like Richard Dawkins (Reference Dawkins2007) that religion is naive or sentimental, and that entertaining the idea of life after death, of God or of non-physical realms is equivalent to believing in fairies and unicorns. Such polemical oversimplifications may cause young people to hide or deny intuitions that might otherwise positively ground their perspective on life.

Though there might seem to be a tension between science and religion, there need not be. Even though the slightest hint that consciousness may be ‘extra-physical’ may be anathema to the physicalist cohort, the proposition does not contravene anything in science. Nor does it require textbooks to be rewritten. One definition of science is ‘a system of knowledge concerned with the physical world and its phenomena’ (Merriam-Webster, Reference Merriam-Webster2023). Science engages with the manifestation of physical reality, but it cannot address the metaphysical question of whether there is anything beyond the physical. These are not grounds to disparage science. One of its great contributions is to reveal the wonder of the world and to be inspired to think bigger. As Sir Francis Bacon (Reference Bacon and Montague1854), credited for the experimental method, said, ‘The world is not to be narrowed till it will go into the understanding … , but the understanding (is) to be expanded and opened till it can take in the image of the world as it is in fact.’ Human epistemologies (i.e. theories of knowledge), including science, do not set ontological categories (i.e. the boundaries of reality).

What does theology offer the discussion? ‘Spirituality offers a worldview that suggests there is more to life than just what people experience on a sensory and physical level’ (Scott, Reference Scott2022). This view is not necessarily incompatible with a scientific outlook or worldview. However, I argue that both share an aspiration to elucidate the ultimate source of everything, and each, in its own way, tends to suppose that there must be a single absolute source that unites and accounts for all that is. However, since we have an unresolved conundrum regarding our own consciousness, it becomes reasonable to ask, Is that ultimate source sentient or non-sentient? Either answer is intellectually feasible.

If the ultimate source is itself sentient, it is possible we could commune with that sentient entity. Such a possibility provides a rationale for a religious worldview that could be philosophically sound and scientifically consistent. It supports various forms of spirituality including non-dual monism (which proposes that ultimate reality is one undifferentiated energy or substance) and devotional theism. It also undermines any stigma attached to those who posit the principle of divine revelation as a source of human knowledge.

Science and spirituality mediated by philosophy could enable young people to address foundational questions of life with greater openness and alacrity. The question is how we support children to grapple with these existential questions in the classroom. Sorting out issues of identity and selfhood are challenges that all young people face as they grow, develop and move through new social environments at home and at school, as well as online. Whatever conclusion an individual comes to, the exploration of existence might challenge and help clarify their concepts of selfhood and their relationship with the world and reality. It might also lead to other facets of meaning and purpose. For example, rather than focusing on morality and good behaviour as something defined by others, having a clearer concept of personal selfhood and its concomitant responsibilities could cause an individual to commit to values, moral behaviour and altruistic activities in keeping with that self-identity and its obligations. Thus, the impetus for morality is turned around. It becomes a self-defined effort to remain authentic to one’s true moral self and what this means for one’s relationships, interactions and service to others.

This project of philosophical exploration can illuminate meaning, value and purpose for the individual, and can therefore be foundational for tackling the existential emptiness that nurtures negativity, isolation, pessimism and despair.

11.6 Summary

My manifesto presents the need for philosophy at the heart of educational experience. It suggests that the silos of science and spirituality need not be so. I suggest that together, mediated by philosophical practices, they could support young people in leading choice rich lives. I end the manifesto with five reasons why this approach is needed, more so than ever.

1) Lack of Meaning Is One Underlying Factor in Mental Health Issues

Depression and mental health disorders, along with feelings of alienation, despair and a lack of purpose or vision, are major issues among schoolchildren, particularly adolescents. The pressure and expectations they face from home, school and society compound underlying vulnerabilities that may stem from feeling they cannot find meaning, purpose and value in their lives.

2) Need to Address the Questions of Existence and Reality

Such meaning and its attendant purposes arise from a clear sense of self and one’s relationship with the world. Both PSHE and RE classes address this topic to a degree, but I contend that the curriculum requires an additional neutral forum of objective philosophical analysis, one that explores the foundational questions that underpin what we believe about ourselves and the greater reality of which we are a part:

Who are we?

What is life?

Where did the world come from?

Is there anything beyond?

Is death the end?

3) The Nature of Existence Remains an Open Question

The wonder of being alive and the worry of our demise is fundamental to human thought. Throughout history, it has fascinated humans engaged in religion, philosophy and science. But, to date, the nature and source of our own existence and awareness of existence remain without certain explanation. A philosophical analysis of the evidence regarding subjective awareness reveals a chasm referred to as the hard problem of consciousness. Science cannot confidently pronounce that human consciousness is a product of physical nature, and religion cannot claim with certainty that it is something transcendent. The question persists open and undetermined. Hence, the messaging, presentations and discussions within education regarding the nature of consciousness, life and reality should be unbiased, neutral and balanced.

4) Employ Objective Philosophical Thinking and Discourse

One role of education should be to explore questions and issues of existence, consciousness and life, on a level playing field. If we have advanced in knowledge in the twenty-first century, let it manifest in our ability to say ‘We do not know.’

5) Exploration and Clarification

Because the nature of existence is unresolved, each of us must clarify what we believe in order to determine our choices, goals and aspirations in life. We must enable pupils to think about the issues for themselves, to grasp the foundational issues and to hear and consider a variety of opinions. Hopefully, whatever their conclusion, the exercise itself will help them discover what matters to them and what defines their selfhood, personal and social identities, responsibilities, relationships and life’s purpose. Through all this, may they find what we would all wish for them: meaningful happiness, purpose, belonging and the ability to share love.