1. Introduction

Group loan contracts are a common tool used by microfinance (MFI) institutions in developing countries to lend to borrowers who lack collateral.Footnote 1 For example, De Quidt et al. Reference De Quidt, Fetzer and Ghatak2018 document that between 2008 and 2014, group loans, in the form of joint liability contracts covered about 30% of the global microcredit market.Footnote 2 Group loans have also made a recent appearance in fintech crowdfunding platforms in developed countries to enhance the financial access of borrowers who lack adequate collateral (Hildebrand et al., Reference Hildebrand, Manju and Rocholl2017). Yet evidence from behavioral experiments indicates that group loan contracts do not necessarily increase repayment rates above what is achieved with individual contracts (e.g.Attanasio et al., Reference Attanasio, Augsburg, De Haas, Fitzsimons and Harmgart2015; Cason et al., Reference Cason, Gangadharan and Maitra2012; Giné & Karlan, Reference Giné and Karlan2014).Footnote 3 This is consistent with the shift that can be observed in microcredit towards individual liability loans (seeDe Quidt et al., Reference De Quidt, Fetzer and Ghatak2018, for empirical evidence).

A crucial question is whether group loan contracts can be designed to guarantee high performance and high repayment rates. As shown in the game-theoretic model of Carli and Uras Reference Carli and Uras(2017), one way to achieve this is to maximize the extent of peer monitoring among the borrowers by introducing asymmetry in the lending contract. In their model a lending institution is faced with two ex ante identical borrowers who make a private investment. The borrowers can choose whether to monitor each other’s investments, and monitoring is not observable to the lending institution and costly.Footnote 4 If a borrower monitors her peer, then the latter behaves diligently, which leads her investment project to have positive net present value. If a borrower does not monitor her peer, however, the latter can behave neglectfully and reduce the profitability of her project. The crux of the model is contained in the borrowers’ monitoring choices. If the terms of repayment are the same for both borrowers, they both have an incentive not to monitor if they believe the other will not monitor. A multiplicity of equilibria then exists, including a low-performance outcome in which none of the two borrowers monitors and a high-performance outcome in which both borrowers monitor. If the lending institution instead sets up the repayment terms such that it is a dominant strategy for one borrower to monitor, then the best response for the other borrower is to monitor as well, making monitoring by both borrowers the unique equilibrium.

It is an open question to which extent introducing asymmetry in the lending contract is behaviorally effective in increasing the extent to which borrowers monitor each other. The current paper investigates this question in a lab experiment. Before bringing asymmetric contracts to the field, it is important to have information about the potential of such policy under tightly controlled conditions. Lab experiments with student subjects are ideal for this purpose because they generate behavioral data at a relatively low cost and allow generalizable inferences about behavior (e.g. Snowberg & Yariv, Reference Snowberg and Yariv2021). If it turns out that there is not much scope for asymmetric contracts to increase the monitoring rate above that achieved with symmetric contracts in lab conditions, then such policy will most likely fail to achieve its purpose in the field. The results of the experiment can thus guide the design of policies that improve the performance of group loan contracts.

In the experiment participants adopt the role of borrower and are matched with another borrower. They choose whether to monitor the other or not. They are randomly allocated to a treatment in which contract terms are symmetric or to a treatment in which contract terms are asymmetric. They make twenty monitoring decisions and after each round of decision-making they are informed about the outcomes and the choice of the matched borrower. In part of the treatments, participants are randomly rematched to another partner-borrower after each round, whereas in the other treatments the partner-borrower is fixed for all twenty rounds.Footnote 5

Asymmetry increases the monitoring rate in our experiment independent of the matching protocol. In the case of random partners, asymmetry increases the monitoring rate by 60 percentage points whereas with fixed partners the increase is equal to 45 percentage points. Overall, a monitoring equilibrium occurs around 60% of the time with asymmetric contracts versus 8% or less with symmetric contracts. Furthermore, asymmetric contracts also increase the expected profit for the lending institution, which turns out positive with asymmetric contracts, while it is negative with symmetric contracts. We conclude that asymmetric contracting induces both improved financial stability and higher profits compared to the symmetric contracts and thus it is likely to provide a new alternative to substantially raise the efficiency of group loan practices.

Our paper relates to the literature that studies the performance of alternative microfinance methods using lab experiments. The findings from this literature reveal that credit-union style microfinance schemes (i.e., rotating saving-and-credit associations) reduce the likelihood of default (El-Gamal et al., Reference El-Gamal, El-Komi, Karlan and Osman2014), while allowing for progressive lending could induce over-borrowing and increase loan defaults (Cecchi et al., Reference Cecchi, Koster and Lensink2021). Also in this literature Barboni Reference Barboni(2017) shows that the flexibility of repayment schedules in microfinance contracts can increase MFI profits by improving the sorting of good and bad borrower types. Our paper complements these studies by showing in an experiment that asymmetry in group lending contracts is yet another mechanism that may improve the performance of microfinance contracts.

Our paper also contributes to the literature that studies using field experiments how the performance of microfinance contracts can be improved.Footnote 6 For instance, Field and Pande Reference Field and Pande(2008) evaluate the effect of repayment frequency on default rates in India, and find no difference between monthly and weekly repayment schedules. Transaction costs for borrowers can thus be decreased without changing the default rate. Giné et al. Reference Giné, Jakiela, Karlan and Morduch(2010) show that installing dynamic incentives can be beneficial for an MFI operating in Peru. They find that cutting off defaulting borrowers from access to future finances reduces the tendency to invest in high-risk projects, and thus increases the likelihood of repayment.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2 we provide the theoretical background. In Section 3 we discuss the experimental design and procedures. In Section 4 we show the results. Section 5 concludes.

2. Theoretical background

The experiment is inspired by the model of Carli and Uras Reference Carli and Uras(2017), in which two borrowers choose between a good and a bad investment project and a lender (an MFI) decides whether to lend.Footnote 7 Both projects generate the same return in the case of success and no return in the case of failure. The good project has a higher success probability than the bad project, and the bad project provides an unpledgeable private benefit to the borrower, which the good project does not provide. Both borrowers need 100% external MFI finance to operate an investment project and the MFI does not observe the project choice of the borrowers.

In the absence of the right incentives, borrowers may prefer the bad project, and a key element in the model is that the MFI can incentivize the borrowers’ investment choices to opt for the good project by stimulating peer monitoring. Peer monitoring refers to borrowers costly monitoring one another. Because peer monitoring is not observable to the MFI, and thus non-contractible, incentivizing borrowers to monitor is not trivial.

The sequence of events is modeled as a dynamic game with two stages. In the first stage, the MFI offers a group lending contract to the borrowers, which consists of a collection of repayments that depend on one’s own and the peer’s project outcomes. If both borrowers accept the group lending contract, they choose the monitoring effort. Monitoring leads to a disutility for the borrower exerting the effort but eliminates the bad project from the set of feasible investments of the peer, thus inducing borrowers to choose the good project. In the second stage, the borrowers privately select a project, either the good or the bad project. Subsequently, the investment outcomes realize and borrowers repay.

As can be shown, under certain restrictionsFootnote 8, the optimal contract has two important features (Proposition 5.4 and Lemmas 5.5 and 5.6 inCarli and Uras, Reference Carli and Uras2017). First, it exhibits joint liability, implying that borrowers are liable for their peer’s low investment return, which is needed to incentivize monitoring. Second, the contract includes an asymmetric treatment of ex ante identical borrowers. In particular, if both borrowers monitor and thus choose the good project, the MFI rewards one borrower with a lower required repayment, making thextent to which the borrowers are attractedis borrower’s expected repayments smaller than those of the other borrower. Asymmetric contracts yield a unique equilibrium in the monitoring subgame in which both borrowers monitor.

If the contracts were symmetric, there would be a second Nash equilibrium in the borrowers’ monitoring subgame because of the strategic complementarities between borrowers’ monitoring decisions (Proposition 6.1 in Carli and Uras, Reference Carli and Uras2017). In this second equilibrium borrowers choose not to monitor and invest in the bad project. Overall, it can be expected that the extent to which borrowers monitor each other, and repay, is (weakly) lower if no asymmetry is included in the contracts. Yet, whether asymmetric contracts should be preferred is ultimately a behavioral question, and the answer depends on the extent to which the borrowers are attracted by the “bad” equilibrium in the case that contracts are symmetric.

Whether contractual asymmetry increases or decreases expected MFI profits, as compared to symmetric contract terms, depends on (i) the repayment schedule that is optimally determined by the group loan contract, and (ii) the borrowers’ monitoring behavior. There are two countervailing effects at work (see Section A.3 in the Appendix). On the one hand, mobilizing monitoring by one borrower by means of an asymmetric contract induces additional costs for the MFI. On the other hand, by using an asymmetric contract the MFI can avoid losses associated with a no-monitoring equilibrium. Which of the two effects dominates—and determines the effect on expected profits—thus depends on the equilibrium achieved when contracts are symmetric. This is another motivation why a controlled experiment is informative.

3. Experiment and hypothesis

3.1 Procedures

The experiment was conducted in May and October, 2019, in CentERlab at Tilburg University, and has been pre-registered.Footnote 9 Participants were recruited by email among students who had indicated a willingness to take part in experiments. Upon arrival in the lab, they were randomly allocated to a computer terminal and were distributed instructions. To ensure incentive-compatibility, the instructions were written in neutral language (see Appendix A). To ensure a sufficient understanding of the instructions, participants had to correctly answer comprehension questions prior to making choices.

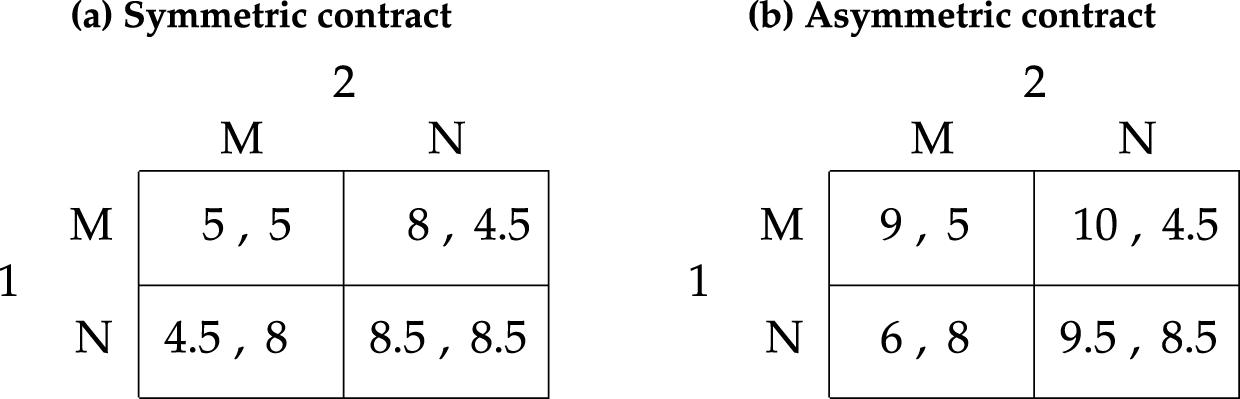

Participants were informed that earnings in Euros would depend on their choices and the choices of others as indicated in the games shown in Figure 1. They were informed that at the end of the experiment one round would be randomly selected for payment.

Fig. 1 Monitoring games in the experiment (a) Symmetric contract b) Asymmetric contract

3.2 Design

In the experiment we focus on the monitoring behavior of the borrowers. We assume that the borrowers have accepted the terms of the loan contract proposed by the MFI at the beginning of the first stage of the (monitoring) game. Moreover, we assume that in the second stage borrowers behave according to the subgame perfect Nash equilibrium; they optimally choose a good or bad investment project conditional on the outcome of the monitoring stage.Footnote 10 Doing so allows us to study the monitoring behavior of the borrowers—which is at the core of the theoretical model—in a clean way, thereby ruling out possible confounds due to non-optimizing behavior in other stages of the game.

This leads to a decision-making setting in which two borrowers choose whether to monitor each other (M) or not (N), and where the contract is either symmetric or asymmetric. Figure 1 shows the payoffs of the borrowers depending on the choices they make. With a symmetric contract there exist two equilibria in pure strategies, namely (M, M) and (N, N), whereas with an asymmetric contract, the game has a unique pure-strategy equilibrium, namely (M, M). The payoffs are based on a parameterization of the Carli-Uras model described above that ensures that none of the two equilibria in the game with symmetric contracts are risk dominant (see Section B of the Appendix for details).Footnote 11

Participants in the experiment played 20 rounds of the symmetric or asymmetric monitoring game. At the end of each round they were informed about the choice of the matched partner and realized payoffs in that round. In all treatments participants kept the same role (borrower 1 or 2) throughout.

We implemented two different matching protocols which varied between treatments. In the Random partners treatments participants were randomly rematched with another participant after each round of play.Footnote 12 The purpose of these treatments was to mimic the one-shot nature of the theoretical model in Carli and Uras Reference Carli and Uras(2017) as closely as possible. In the Same partner treatments, participants were matched to the same partner for all rounds. From these treatments we aim to learn whether the model’s equilibrium predictions are valid if borrowers repeatedly interact, which is likely more representative of interactions in real-world loan markets.

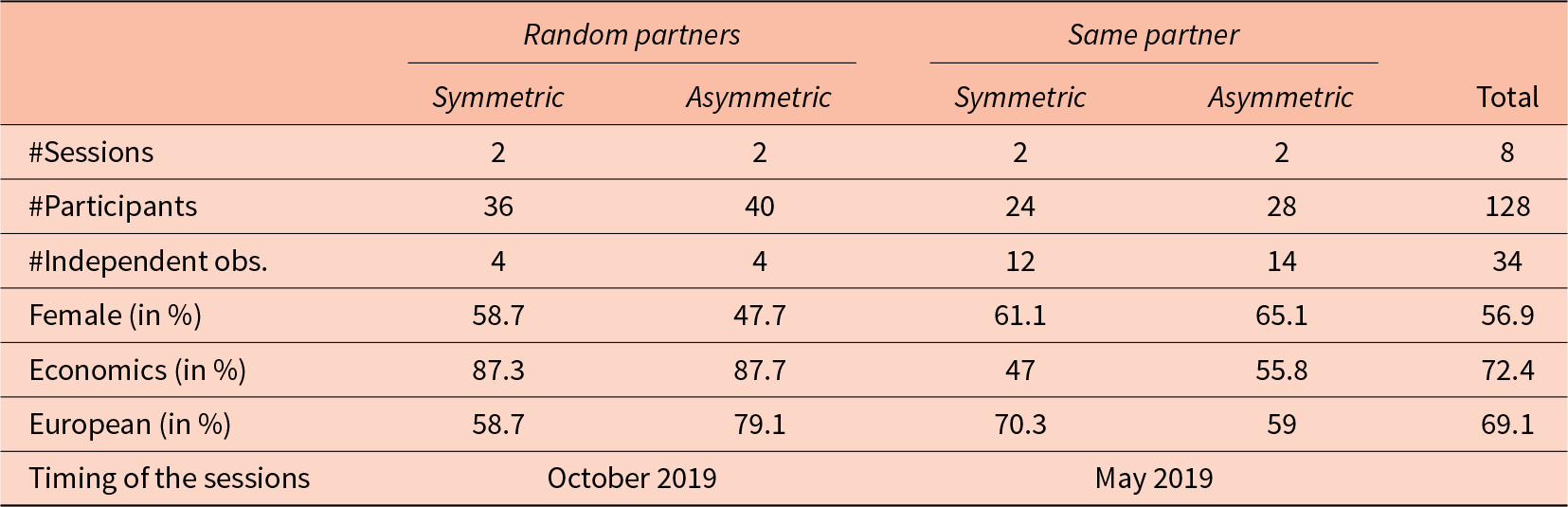

Table 1 gives an overview of the number of sessions, independent observations and participants in each of the treatments, as well as descriptive statistics on the share of female participants, the share of economics students, and the share of European students, which were collected at the session level. As can be seen in the table, within the Random partners or Same partner treatments, the sessions with Symmetric and Asymmetric were balanced in terms of these variables, which implies that we can interpret differences in behavior between Symmetric and Asymmetric treatments as caused by asymmetry in contracts. Yet, the composition of the subject pool in the Random partners and Same partner sessions differs quite substantially, possibly due to the different timing of the two series of sessions, making us reluctant to draw a causal inference about the effect of the matching protocol on behavior.Footnote 13

Table 1 Information on treatments

Notes: Independent observations refer to matching groups (in the case of random partners) or to pairs of matched borrowers (in the case of same partners). Matching groups consisted of 10 participants.

3.3 Research hypothesis

We build our hypothesis upon the model discussed in Section 2, focusing on the effect of asymmetry of contract terms on the extent of monitoring, which is directly connected to the likelihood of ending up in the full monitoring equilibrium (M, M). Specifically, our hypotheses are:

(i) The percentage of monitoring in the case of random-partners is higher in the asymmetric treatments than in the symmetric treatments.

(ii) The percentage of monitoring in the case of same-partners is higher in the asymmetric treatments than in the symmetric treatments.

Our experiment also allows us to infer the effect of asymmetry of contract terms on MFI profits and on profits of borrowers. If the monitoring rate is substantially higher with asymmetric contract terms than with symmetric contract terms, then it can be expected that MFI profits are higher in the former than in the latter case, but it is an open question whether borrowers are also better off.

4. Results

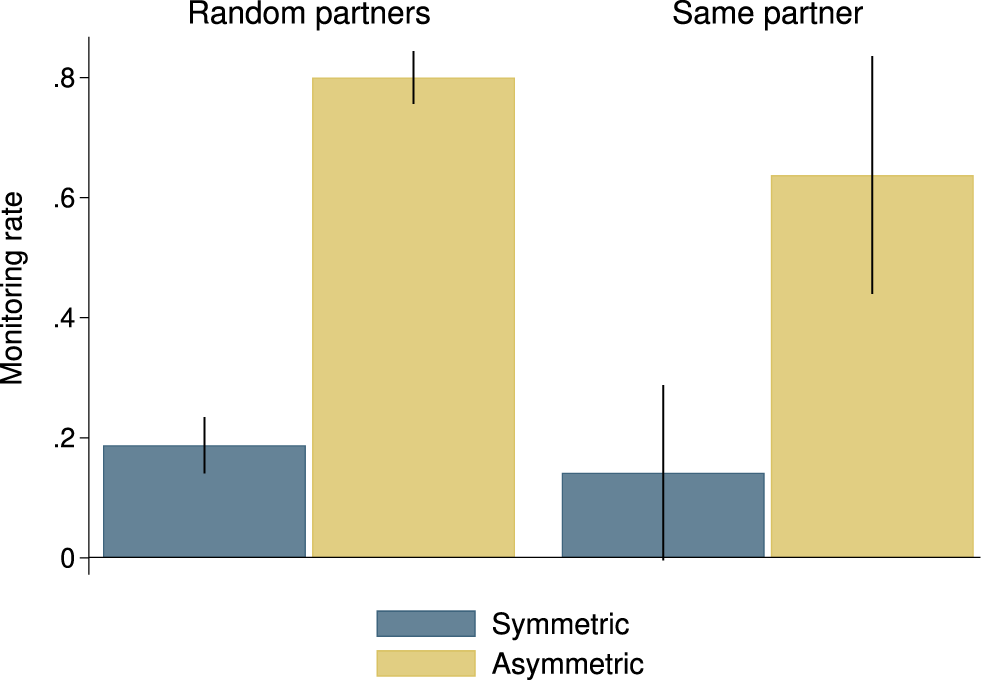

We study the effect of asymmetry in contracts on the rate at which participants in the role of borrower choose to monitor. Figure 2 shows the monitoring rate averaged over all 20 rounds by treatment. As can be seen, asymmetry of contracts has a major effect on the monitoring rate; asymmetry increases the monitoring rate by more than 50 percentage points at the individual participant level. The effect is statistically significant in probit regressions with clustering at the level of independent observations based on all data (![]() $p \lt 0.001$), the Random partners sessions (

$p \lt 0.001$), the Random partners sessions (![]() $p \lt 0.001$), or the Same partner sessions (

$p \lt 0.001$), or the Same partner sessions (![]() $p \lt 0.001$).Footnote 14 Our research hypothesis is thus confirmed.Footnote 15

$p \lt 0.001$).Footnote 14 Our research hypothesis is thus confirmed.Footnote 15

Fig. 2 Monitoring rate by treatment

To give an idea of the power, we calculate the power for the treatment effect that we get when collapsing the data by independent observation. The statistics are an average monitoring rate of 0.163 with standard deviation 0.234 based on 16 observations in the Symmetric treatment and an average monitoring rate of 0.674 with standard deviation 0.345 based on 18 observations in the Asymmetric. If we use ![]() $\alpha=0.05$, then the estimated power of a two-sided t-test with unequal variances is equal to 0.99.Footnote 16

$\alpha=0.05$, then the estimated power of a two-sided t-test with unequal variances is equal to 0.99.Footnote 16

The implication of the observed behavior for outcomes is that random partners end up 66% of the time in the monitoring equilibrium (that is, they mutually monitor) with asymmetric contracts versus 3% of the time with symmetric contracts. A non-monitoring outcome, in which both borrowers choose not to monitor, is observed 6% of the time with asymmetric contracts and 66% of the time with symmetric contracts (recall that only in the latter case did both borrowers not monitoring constitute an equilibrium). In the same partner treatments we find that borrowers with asymmetric contracts are 56% of the time in the monitoring equilibrium and 29% in the non-monitoring equilibrium. Borrowers with symmetric contracts are 8% of the time in a monitoring equilibrium and 80% of the time in a non-monitoring equilibrium.

Next, we answer the question whether the difference in monitoring rates between asymmetric and symmetric treatments is large enough to generate a difference in MFI profits. Calculations show that this is indeed the case: profits are larger with asymmetric contracts than with symmetric contracts. Specifically, computing profits using the parametrized model leads to a positive profit for the MFI with asymmetric contracts of 0.099 and a loss of 0.215 with symmetric contracts (![]() $p \lt 0.001$ in a regression, see Table D.2 in the Appendix).Footnote 17 These results imply that asymmetric contracts lead to financial stability and higher expected MFI profits. The causal effect of asymmetry on monitoring is thus large enough to have the MFI to make a higher profit with asymmetric contracts compared to symmetric contracts. Moreover, the causal effect on monitoring behavior and MFI profits is robust to the matching protocol (random partners versus same partner).Footnote 18

$p \lt 0.001$ in a regression, see Table D.2 in the Appendix).Footnote 17 These results imply that asymmetric contracts lead to financial stability and higher expected MFI profits. The causal effect of asymmetry on monitoring is thus large enough to have the MFI to make a higher profit with asymmetric contracts compared to symmetric contracts. Moreover, the causal effect on monitoring behavior and MFI profits is robust to the matching protocol (random partners versus same partner).Footnote 18

Finally, we investigate whether asymmetric contracts affect the welfare of borrowers. We find that asymmetry in contracts does not make borrowers substantially worse off. Across the Random partners and Same partner treatments, they earn 7.6 Euros with symmetric contracts and 0.4 Euros less with asymmetric contracts, and the difference is marginally significant (see Table D.3 in the Appendix). If we consider the Random partners and Same partner treatments separately, the effect is statistically not significant.Footnote 19

5. Discussion

Understanding the efficiency of group loan contracts with joint liability is essential for the design of optimal financial development policies and for improving financial inclusion. These contracts have been pervasively used by MFIs in developing countries and have received theoretical back-up. Yet a number of empirical and theoretical studies cast doubt on their performance. We show in an experiment inspired by Carli and Uras Reference Carli and Uras(2017) that performance can be increased if the MFI introduces asymmetric, borrower-specific contract terms that make monitoring a dominant strategy for one borrower (the leader). Such asymmetry breaks coordination by borrowers who jointly refuse to monitor each other, and mobilizes peer monitoring, which in turn increases the probability of repayment. Our experiment reveals that the monitoring behavior differs substantially when asymmetric and symmetric contracts are compared and profits are higher with asymmetric contracts — addressing the research questions that motivated the experimental design.

Asymmetric contracts of the type studied may be particularly attractive in cases or circumstances where joint liability contracts have not performed well in the past or are expected to lead to financial instability. Examples include cases in which the borrower groups consist of clients with little interpersonal trust or weak social ties (see e.g.Besley & Coate, Reference Besley and Coate1995; Cassar et al., Reference Cassar, Crowley and Wydick2007; De Quidt et al., Reference De Quidt, Fetzer and Ghatak2018; Hermes et al., Reference Hermes, Lensink and Mehrteab2006; Hermes et al., Reference Hermes, Lensink and Mehrteab2005; Karlan, Reference Karlan2007; Paxton et al., Reference Paxton, Graham and Thraen2000). In such a context Paxton et al. Reference Paxton, Graham and Thraen(2000), Hermes et al. Reference Hermes, Lensink and Mehrteab(2005) and Hermes et al. Reference Hermes, Lensink and Mehrteab(2006) find that the quality of the group leader is positively related to its repayment performance, which could be seen as evidence for the fact that the group leader plays a prominent role in screening, monitoring and enforcing repayment within a group. That said, we find that in the treatment with random partners, which is arguably closest to the case of weak social ties, asymmetric contracts achieve a monitoring rate of 80%. This is almost 17 percentage points higher than that in the treatment where partners remain the same throughout the experiment. Although the difference is statistically not significant (![]() $p=0.118$), the qualitative effect is quite substantial and relates to Paxton et al. Reference Paxton, Graham and Thraen(2000) and Wydick Reference Wydick(1999), who show that strong social ties do not improve loan repayment performance of the group, and may even have a negative effect.Footnote 20

$p=0.118$), the qualitative effect is quite substantial and relates to Paxton et al. Reference Paxton, Graham and Thraen(2000) and Wydick Reference Wydick(1999), who show that strong social ties do not improve loan repayment performance of the group, and may even have a negative effect.Footnote 20

Finally, our results are relevant for forms of group lending in fintech crowdfunding platforms. On crowdfunding platforms borrowers can form groups to develop a reputation and to reduce information asymmetries vis-à-vis a large number of investors. Remarkably, Freedman and Jin Reference Freedman and Jin(2017) find that in the context of crowdfunding social ties could weaken group loan performance due to easing up collusive behavior among borrowers. Moreover, empirical research by Iyer et al. Reference Iyer, Khwaja, Luttmer and Shue(2016) and Hildebrand et al. Reference Hildebrand, Manju and Rocholl(2017) shows that group loan contracts outperform individual contracts in terms of repayment in this context, and highlights that the presence of a leader-borrower is key for the performance of group loans. Interestingly, Hildebrand et al. Reference Hildebrand, Manju and Rocholl(2017) show that the unconditional compensation of group leaders does not raise performance of group loans in crowdfunding. Our results suggest that if compensations were to take the form of conditional rewards, the repayment performance of the group may in fact increase also in the context of crowdfunding group loans.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/esa.2025.10024.

Acknowledgements

The experiment has been pregistered at the AEA RCT Registry under code AEARCTR-0004217. The replication material for the study is available at DOI link. We thank CentERlab for financial support and Lenka Fiala for assistance with experimental sessions. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not reflect those of Rabobank.