1. Introduction

The anatomical ankle-foot complex is a structure capable of adapting its mechanical behavior through neuromuscular control to meet the demands of a given task, such as maintaining stability while standing quietly or enabling efficient progression of the body over the stance limb while walking. During quiet standing, the muscles and ligaments of the foot and ankle work together to increase ankle-foot impedance to maintain upright posture (A. H. Hansen and Wang, Reference Hansen and Wang2010). During gait, the same muscles and ligaments alter foot and ankle stiffness and effective roll-over geometry to meet specific demands of the gait phases and adapt to different terrains (Andrew Howard Hansen, Reference Hansen2002; A. H. Hansen and Childress, Reference Hansen and Childress2005; A. H. Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Childress and Knox2004). This behavior is reflected in the sagittal-plane ankle motion as the ankle joint angle alternates from plantarflexion to dorsiflexion and produces four distinct arcs of motion (Perry and Burnfield, Reference Perry and Burnfield2010), the first three arcs corresponding to the stance phase (transitioning from plantarflexion to dorsiflexion back to plantarflexion) and the fourth arc (dorsiflexion) to the swing phase. During the stance phase, the ankle-foot functions include shock absorption, supporting body weight, enabling forward progression (Pace et al., Reference Pace, Howard, Gard and Major2020), and initiating the swing phase. During the swing phase, the ankle joint dorsiflexes to achieve safe limb progression and prepares for limb touchdown (Kent et al., Reference Kent, Arelekatti, Petelina, Johnson, Brinkmann, Winter and Major2021).

Lower-limb prosthesis users are clinically prescribed and fitted with prosthetic ankle-foot mechanisms that are designed to substitute for missing anatomical behavior. To achieve this aim, ankle-foot prosthesis designs have progressively become more complex, with vast amounts of studies comparing the advantages and disadvantages of each design iteration (van der Linde et al., Reference van der Linde, Hofstad, Geurts, Postema, Geertzen and van Limbeek2004; Highsmith et al., Reference Highsmith, Kahle, Miro, Orendurff, Lewandowski, Orriola, Sutton and Ertl2016; Lathouwers et al., Reference Lathouwers, Díaz, Maricot, Tassignon and De Pauw2023). One example of a simple design is the solid ankle-cushioned heel (SACH) foot, which has a rigid ankle and foot structure that accommodates less-skilled ambulators (Macfarlane et al., Reference Macfarlane, Nielsen and Shurr1997; Paradisi et al., Reference Paradisi, Delussu, Brunelli, Iosa, Pellegrini, Zenardi and Traballesi2015). Beyond the SACH foot, more complex devices have been developed (Matthew J. Major and Stevens, Reference Major, Stevens, Krajbich, Pinzur, Potter and Stevens2024 ) such as single-axis feet with a movable ankle joint that permits sagittal plane motion; multiaxial feet that permit motion in all three planes; dynamic response (DR) feet that are better able to store and return energy through the stance phase and pre-swing, respectively; and foot designs with a hydraulic damper at the ankle joint to modulate ankle impedance and accommodate to different terrains. Moreover, mechatronic components have been incorporated into ankle-foot prostheses to control their mechanical behavior and, in some cases, actuate ankle motion. Different ankle-foot prosthesis designs can have unique characteristics that ultimately affect the standing and walking performance of lower-limb prosthesis users (Wirta et al., Reference Wirta, Mason, Calvo and Golbranson1991). Consequently, research has focused on characterizing stance-phase (i.e., loaded) mechanical characteristics of passive ankle-foot prostheses such as range of motion, damping, stiffness (M. J. Major et al., Reference Major, Twiste, Kenney and Howard2014; Vaca et al., Reference Vaca, Stine, Hammond, Cavanaugh, Major and Gard2022), and roll-over-shape (ROS) (Vaca et al., Reference Vaca, Stine, Hammond, Cavanaugh, Major and Gard2022) to map prosthesis mechanical properties to user outcomes (M. J. Major and Fey, Reference Major and Fey2017).

Transfemoral prosthesis users (TFPUs) and transtibial prosthesis users (TTPUs) are two primary cohorts that utilize prosthetic ankle-foot mechanisms for mobility. Although these devices serve essentially the same purpose for both groups (i.e., stance phase limb stability and progression), their mechanical function must be able to accommodate and support the needs associated with missing anatomical structures and mobility requirements unique to each cohort. Specific to TFPUs, ankle-foot mechanisms must also successfully interact with a prosthetic knee joint that, in most conventional prostheses, lacks volitional control (Matthew J. Major and Stevens, Reference Major, Stevens, Krajbich, Pinzur, Potter and Stevens2024 ). For instance, the geometry and mechanical response of the prosthetic ankle-foot while loaded directs the ground reaction force (GRF) vector position (Pace et al., Reference Pace, Howard, Gard and Major2020) that generates a desired extensor moment to prevent the mechanical knee from flexing (i.e., buckling) until an appropriate time during terminal stance (de Vries, Reference de Vries1995). Therefore, while studies have focused on the effects of the mechanical properties of ankle-foot prostheses on mobility outcomes in TTPUs (M. J. Major and Fey, Reference Major and Fey2017), those relationships may not directly translate to TFPUs due to their interaction with the prosthetic knee. For example, Barnett et al.(Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Hughes, Sullivan, Strutzenberger, Levick, Bisele and De Asha2021) reported an improvement in gait performance (more distance covered during a 2-minute walking test) while using a hydraulic ankle in conjunction with two different prosthetic knee designs, with even better mobility when that ankle-foot design is used in combination with a microprocessor knee. Additionally, Pace et al. (Pace et al., Reference Pace, Howard, Gard and Major2020) simulated the interaction effect of a single-axis knee alignment (center of rotation) and prosthetic ankle-foot stiffness on prosthetic limb stability during stance by analyzing critical prosthetic knee joint moments in the sagittal plane. Furthermore, evidence suggests that TFPUs manage their standing balance differently than TTPUs (Rougier and Bergeau, Reference Rougier and Bergeau2009; Toumi et al., Reference Toumi, Simoneau-Buessinger, Bassement, Barbier, Gillet, Allard and Leteneur2021), which would similarly be affected by ankle-foot prosthesis mechanics (Nederhand et al., Reference Nederhand, Van Asseldonk, van der Kooij and Rietman2012).

The purpose of this review was to characterize the current state of published knowledge about the effects of ankle-foot prosthesis design on standing and walking performance in TFPUs. Results from this work will help establish our current understanding of ankle-foot prosthesis effects on clinically relevant outcomes in TFPUs and increase our knowledge of these relationships for leg prosthesis users by complementing the existing knowledge for TTPUs. Through this study, we also aim to identify gaps in this knowledge to direct research efforts that will ultimately inform clinical practice guidelines for people with lower-limb loss to improve outcomes for users of ankle-foot prostheses.

2. Methods

The protocol was developed by a three-member research team in collaboration with a research librarian and utilized the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) as a guide to standardize reporting of the methods and results (Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O’Brien, Colquhoun, Levac, Moher, Peters, Horsley, Weeks, Hempel, Akl, Chang, McGowan, Stewart, Hartling, Aldcroft, Wilson, Garritty, Lewin, Godfrey, Macdonald, Langlois, Soares-Weiser, Moriarty, Clifford, Tunçalp and Straus2018).

2.1. Search strategy

The search strategy was developed according to the population–intervention–outcome (PIO) structure of global key terms: population – TFPUs; intervention – ankle-foot prosthesis; outcome – gait and standing balance. These PIO key terms were translated into search terms, including synonyms, alterations in spelling, and wildcards, and joined together using Boolean operators. The databases of PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Xplore were searched on January 6, 2025, and selected to retrieve articles from various disciplines, including health and engineering research. The search string was first developed for PubMed and then modified for use in other databases (Table 1). There was no date or language limit assigned on the search engine. A secondary search was performed by reviewing the references of those articles that were ultimately included in the review and relevant literature reviews.

Table 1. Search strings for the different databases

2.2. Selection criteria

The screening and selection processes were performed primarily by a single reviewer. The retrieved records from all databases were uploaded into a central database (EndNote v20.0.1, Philadelphia, PA, USA), and duplicates were removed. The title and abstract of the remaining records were first screened for relevance. If relevant, the full text of those articles was evaluated against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. In cases of uncertainty about the inclusion of a specific article, the primary reviewer and two senior authors reviewed and discussed the article’s contents to arrive at a final decision. The inclusion criteria included: original research studies involving human subject experiments or numerical simulations; studies examining the population of adult TFPUs (18 years or older); interventions comparing different prosthetic ankle-foot mechanisms (either defined by design type or quantified user-independent mechanical properties); outcomes quantifying a dimension of gait and/or balance. The exclusion criteria included: meta-analysis, systematic reviews, group consensus, and individual opinions; studies that compared only prosthetic knees without modifications to the ankle-foot prosthesis; and studies that present combined results for TFPUs and TTPUs that did not allow separate analyses of each group. The articles had to be written in English or translated to the English language for inclusion, and there were no restrictions on amputation etiology, participant experience or activity level, tested prosthetic knee, year of publication, or experimental setting (e.g., clinic, laboratory, in silico, etc.).

2.3. Data extraction

Data to characterize the body of literature and address the research aim were extracted from the included articles and compiled into an electronic spreadsheet (Excel v1206, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). These data elements included authors, publication year, article title, article type, publication journal, study design, setting if human subject experiments, stated aims, protocol, prosthetic device interventions, prosthesis manufacturer(s) as appropriate, primary outcome measures, statistical analysis methods, participant characteristics as appropriate (sample size, amputation level(s), mean or range of age, sex distribution, amputation etiology distribution), and key results and findings.

3. Results

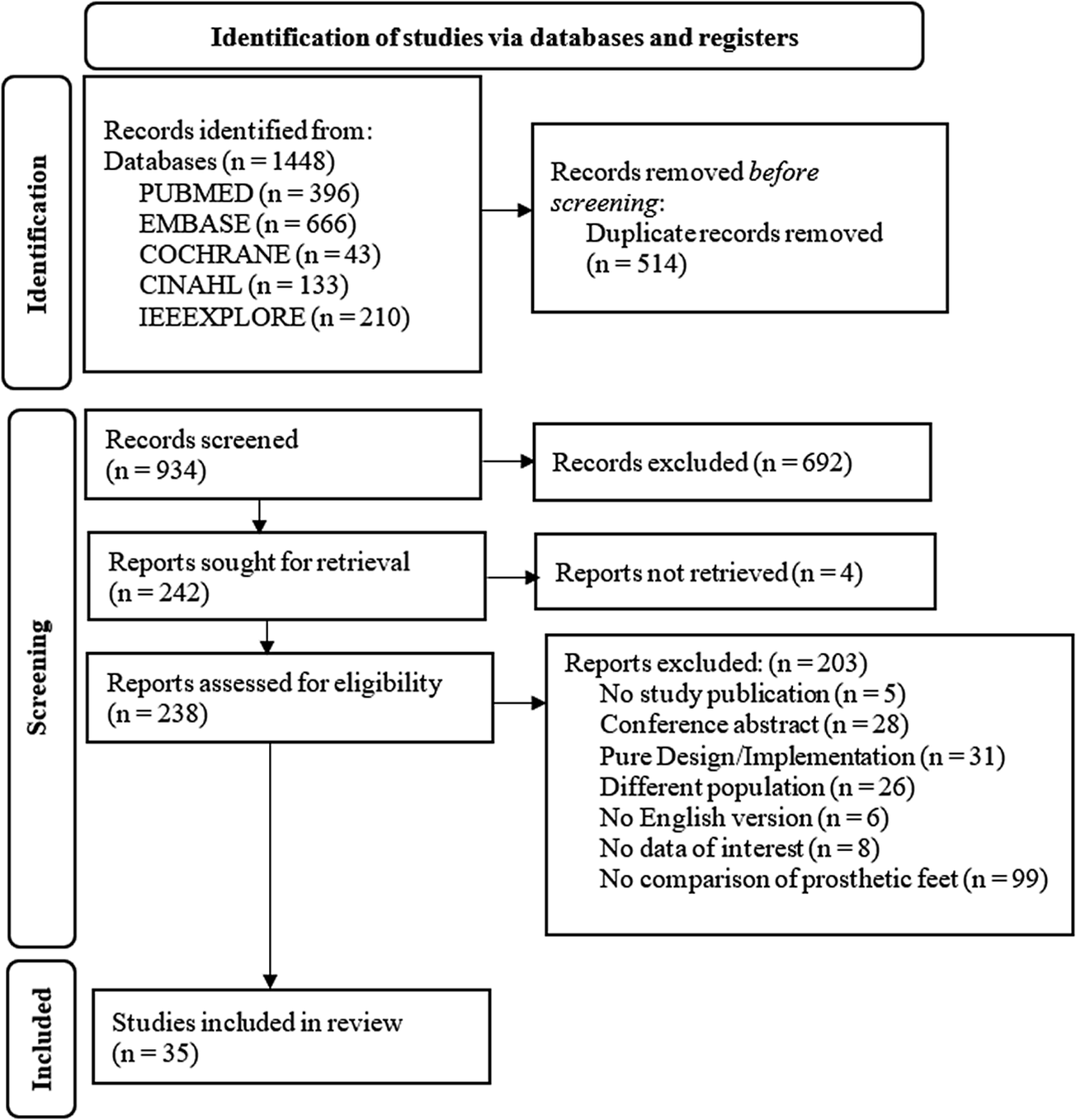

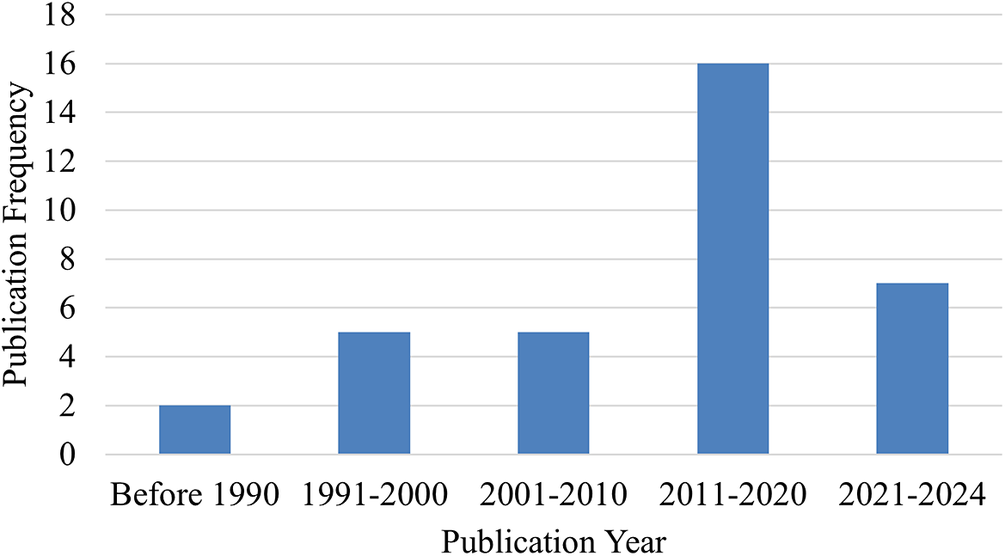

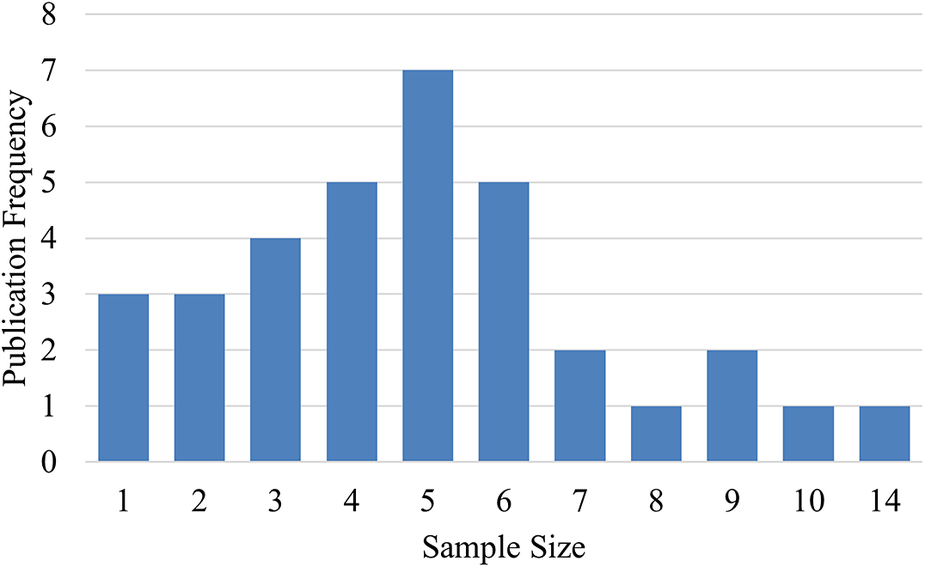

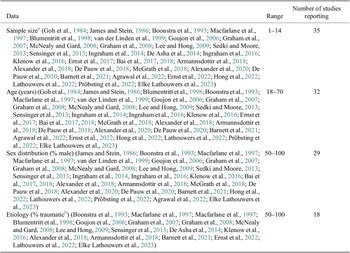

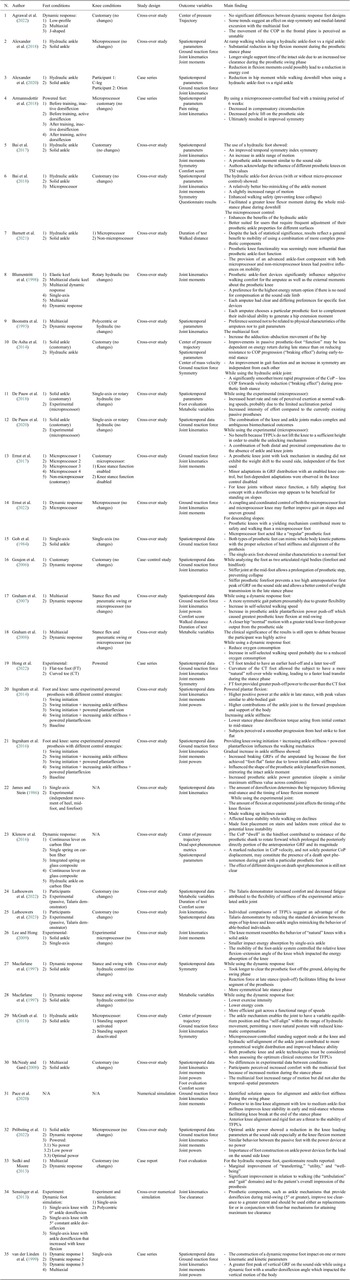

The final search yielded a total of 1448 articles prior to screening. Following screening and evaluation, 35 articles were ultimately included in the review (Figure 1). These 35 articles were published over 39 years (1984 to 2024), with more than half (n = 23) published in the latter 14 years (Figure 2). Two studies included in-silico analysis (Sensinger et al., Reference Sensinger, Intawachirarat and Gard2013; Pace et al., Reference Pace, Howard, Gard and Major2020), and the number of participants for human subject studies ranged from 1 to 14 (Figure 3). The study designs employed were also diverse (Figure 4), with the vast majority (n = 27) utilizing a cross-over repeated-measures approach. A summary of the participant characteristics is presented in Table 2.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of screening and evaluation results.

Figure 2. Publication frequency of year published.

Figure 3. Publication frequency of sample size for in vivo studies.

Figure 4. Proportion of study designs across reviewed literature.

Table 2. Participant characteristics

a For those studies that included transtibial and transfemoral prosthesis users, this number represents only the transfemoral cohort.

b Other etiologies included vascular, sarcoma, infection, arterial occlusion.

For those articles that performed human subject testing with commercially available ankle-foot prostheses, these devices spanned a range of classifications: solid-ankle feet (n = 21) (Goh et al., Reference Goh, Solomonidis, Spence and Paul1984; Macfarlane et al., Reference Macfarlane, Nielsen, Shurr, Meier, Clark, Kerns, Moreno and Ryan1997; Macfarlane et al., Reference Macfarlane, Nielsen and Shurr1997; Blumentritt et al., Reference Blumentritt, Scherer, Michael and Schmalz1998; Goujon et al., Reference Goujon, Bonnet, Sautreuil, Maurisset, Darmon, Fode and Lavaste2006; McNealy and Gard, Reference McNealy and Gard2008; Lee and Hong, Reference Lee and Hong2009; Sedki and Moore, Reference Sedki and Moore2013; Sensinger et al., Reference Sensinger, Intawachirarat and Gard2013; De Asha et al., Reference De Asha, Munjal, Kulkarni and Buckley2014; Klenow et al., Reference Klenow, Kahle and Highsmith2016; Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2017; Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Altenburg, Bellmann and Schmalz2017; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Strutzenberger, Kroell, Barnett and Schwameder2018; Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2018; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Cherelle, Roelands, Lefeber and Meeusen2018; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laszczak, Zahedi and Moser2018; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Strutzenberger and Schwameder2020; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Serrien, Baeyens, Cherelle, De Bock, Ghillebert, Bailey, Lefeber, Roelands, Vanderborght and Meeusen2020; Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Hughes, Sullivan, Strutzenberger, Levick, Bisele and De Asha2021; Pröbsting et al., Reference Pröbsting, Altenburg, Bellmann, Krug and Schmalz2022); single-axis feet (n = 13) (Goh et al., Reference Goh, Solomonidis, Spence and Paul1984; James and Stein, Reference James and Stein1986; Blumentritt et al., Reference Blumentritt, Scherer, Michael and Schmalz1998; Lee and Hong, Reference Lee and Hong2009; Sensinger et al., Reference Sensinger, Intawachirarat and Gard2013; De Asha et al., Reference De Asha, Munjal, Kulkarni and Buckley2014; Klenow et al., Reference Klenow, Kahle and Highsmith2016; Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2017, Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2018; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Strutzenberger, Kroell, Barnett and Schwameder2018; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laszczak, Zahedi and Moser2018; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Strutzenberger and Schwameder2020; Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Hughes, Sullivan, Strutzenberger, Levick, Bisele and De Asha2021); DR feet (n = 23) (Boonstra et al., Reference Boonstra, Fidler, Spits, Tuil and Hof1993; Blumentritt et al., Reference Blumentritt, Scherer, Michael and Schmalz1998; Macfarlane et al., Reference Macfarlane, Nielsen, Shurr, Meier, Clark, Kerns, Moreno and Ryan1997; van der Linden et al., Reference van der Linden, Solomonidis, Spence, Li and Paul1999; Goujon et al., Reference Goujon, Bonnet, Sautreuil, Maurisset, Darmon, Fode and Lavaste2006; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller, Howitt and Pros2007; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller and Howitt2008; McNealy and Gard, Reference McNealy and Gard2008; Sedki and Moore, Reference Sedki and Moore2013; De Asha et al., Reference De Asha, Munjal, Kulkarni and Buckley2014; Klenow et al., Reference Klenow, Kahle and Highsmith2016; Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2017, Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2018; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Strutzenberger, Kroell, Barnett and Schwameder2018; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laszczak, Zahedi and Moser2018; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Strutzenberger and Schwameder2020; Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Hughes, Sullivan, Strutzenberger, Levick, Bisele and De Asha2021; Agrawal et al., Reference Agrawal, Gaunaurd, Kim, Bennett and Gailey2022; Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Altenburg, Schmalz, Kannenberg and Bellmann2022; Lathouwers et al., Reference Lathouwers, Ampe, Díaz, Meeusen and De Pauw2022; Pröbsting et al., Reference Pröbsting, Altenburg, Bellmann, Krug and Schmalz2022; Elke Lathouwers et al., Reference Lathouwers, Baeyens, Tassignon, Gomez, Cherelle, Meeusen, Vanderborght and De Pauw2023); multiaxial feet (n = 6) (Boonstra et al., Reference Boonstra, Fidler, Spits, Tuil and Hof1993; Blumentritt et al., Reference Blumentritt, Scherer, Michael and Schmalz1998; van der Linden et al., Reference van der Linden, Solomonidis, Spence, Li and Paul1999; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller, Howitt and Pros2007; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller and Howitt2008; McNealy and Gard, Reference McNealy and Gard2008); feet with a hydraulic ankle joint (n = 6) (Sedki and Moore, Reference Sedki and Moore2013; De Asha et al., Reference De Asha, Munjal, Kulkarni and Buckley2014; Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2017, Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2018; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laszczak, Zahedi and Moser2018; Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Hughes, Sullivan, Strutzenberger, Levick, Bisele and De Asha2021); microprocessor feet without power generation (n = 5) (Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Altenburg, Bellmann and Schmalz2017; Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2018; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Cherelle, Roelands, Lefeber and Meeusen2018; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Serrien, Baeyens, Cherelle, De Bock, Ghillebert, Bailey, Lefeber, Roelands, Vanderborght and Meeusen2020; Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Altenburg, Schmalz, Kannenberg and Bellmann2022); and powered/actuated feet (n = 2) (Armannsdottir et al., Reference Armannsdottir, Tranberg, Halldorsdottir and Briem2018; Pröbsting et al., Reference Pröbsting, Altenburg, Bellmann, Krug and Schmalz2022). Additionally, nine articles (James and Stein, Reference James and Stein1986; Lee and Hong, Reference Lee and Hong2009; K. A. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2014; K. M. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2016; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Cherelle, Roelands, Lefeber and Meeusen2018; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Serrien, Baeyens, Cherelle, De Bock, Ghillebert, Bailey, Lefeber, Roelands, Vanderborght and Meeusen2020; Hong et al., Reference Hong, Kumar, Patrick, Um, Kim, Kim and Hur2022; Lathouwers et al., Reference Lathouwers, Ampe, Díaz, Meeusen and De Pauw2022; Elke Lathouwers et al., Reference Lathouwers, Baeyens, Tassignon, Gomez, Cherelle, Meeusen, Vanderborght and De Pauw2023) reported comparisons between different foot behaviors using experimental devices that were not commercially available. These experimental devices were used to assess effects of foot curvature (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Kumar, Patrick, Um, Kim, Kim and Hur2022), “ankle” range of motion (Lee and Hong, Reference Lee and Hong2009), keel motion (James and Stein, Reference James and Stein1986), increase in ankle stiffness (K. A. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2014; K. M. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2016; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Cherelle, Roelands, Lefeber and Meeusen2018; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Serrien, Baeyens, Cherelle, De Bock, Ghillebert, Bailey, Lefeber, Roelands, Vanderborght and Meeusen2020; Lathouwers et al., Reference Lathouwers, Ampe, Díaz, Meeusen and De Pauw2022; Elke Lathouwers et al., Reference Lathouwers, Baeyens, Tassignon, Gomez, Cherelle, Meeusen, Vanderborght and De Pauw2023), and powered plantarflexion (K. A. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2014; K. M. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2016). Across all studies (human subject and numerical simulation), 29 studies (Goh et al., Reference Goh, Solomonidis, Spence and Paul1984; James and Stein, Reference James and Stein1986; Boonstra et al., Reference Boonstra, Fidler, Spits, Tuil and Hof1993; Macfarlane et al., Reference Macfarlane, Nielsen and Shurr1997; Blumentritt et al., Reference Blumentritt, Scherer, Michael and Schmalz1998; van der Linden et al., Reference van der Linden, Solomonidis, Spence, Li and Paul1999; McNealy and Gard, Reference McNealy and Gard2008; Lee and Hong, Reference Lee and Hong2009; Goujon et al., Reference Goujon, Bonnet, Sautreuil, Maurisset, Darmon, Fode and Lavaste2006; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller, Howitt and Pros2007; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller and Howitt2008; Sedki and Moore, Reference Sedki and Moore2013; Sensinger et al., Reference Sensinger, Intawachirarat and Gard2013De Asha et al., Reference De Asha, Munjal, Kulkarni and Buckley2014; Klenow et al., Reference Klenow, Kahle and Highsmith2016; Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2017, Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2018; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Cherelle, Roelands, Lefeber and Meeusen2018; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Strutzenberger, Kroell, Barnett and Schwameder2018; Armannsdottir et al., Reference Armannsdottir, Tranberg, Halldorsdottir and Briem2018; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Strutzenberger and Schwameder2020; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Serrien, Baeyens, Cherelle, De Bock, Ghillebert, Bailey, Lefeber, Roelands, Vanderborght and Meeusen2020; Agrawal et al., Reference Agrawal, Gaunaurd, Kim, Bennett and Gailey2022; Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Altenburg, Schmalz, Kannenberg and Bellmann2022; Hong et al., Reference Hong, Kumar, Patrick, Um, Kim, Kim and Hur2022; Pröbsting et al., Reference Pröbsting, Altenburg, Bellmann, Krug and Schmalz2022Lathouwers et al., Reference Lathouwers, Ampe, Díaz, Meeusen and De Pauw2022; Elke Lathouwers et al., Reference Lathouwers, Baeyens, Tassignon, Gomez, Cherelle, Meeusen, Vanderborght and De Pauw2023) observed effects of only changing ankle-foot prosthesis design/function, while six studies (K. A. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2014; K. M. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2016; Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Altenburg, Bellmann and Schmalz2017; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laszczak, Zahedi and Moser2018; Pace et al., Reference Pace, Howard, Gard and Major2020; Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Hughes, Sullivan, Strutzenberger, Levick, Bisele and De Asha2021) observed effects of changing properties of both the prosthetic ankle-foot mechanism and knee.

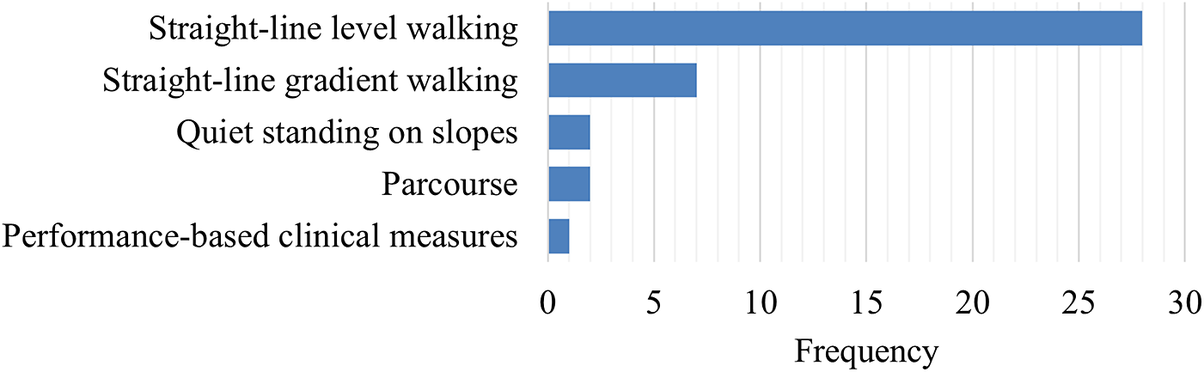

Performance in a range of tasks was assessed, classified into five categories (Figure 5):

-

1. Straight-line level walking (n = 29) (Goh et al., Reference Goh, Solomonidis, Spence and Paul1984; Boonstra et al., Reference Boonstra, Fidler, Spits, Tuil and Hof1993; Macfarlane et al., Reference Macfarlane, Nielsen, Shurr, Meier, Clark, Kerns, Moreno and Ryan1997; Blumentritt et al., Reference Blumentritt, Scherer, Michael and Schmalz1998; van der Linden et al., Reference van der Linden, Solomonidis, Spence, Li and Paul1999; Goujon et al., Reference Goujon, Bonnet, Sautreuil, Maurisset, Darmon, Fode and Lavaste2006; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller, Howitt and Pros2007; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller and Howitt2008; McNealy and Gard, Reference McNealy and Gard2008; Lee and Hong, Reference Lee and Hong2009; Sensinger et al., Reference Sensinger, Intawachirarat and Gard2013; De Asha et al., Reference De Asha, Munjal, Kulkarni and Buckley2014; Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2014; K. M. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2016; Klenow et al., Reference Klenow, Kahle and Highsmith2016; Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2017; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Cherelle, Roelands, Lefeber and Meeusen2018; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Strutzenberger, Kroell, Barnett and Schwameder2018; Armannsdottir et al., Reference Armannsdottir, Tranberg, Halldorsdottir and Briem2018; Pace et al., Reference Pace, Howard, Gard and Major2020; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Strutzenberger and Schwameder2020; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Serrien, Baeyens, Cherelle, De Bock, Ghillebert, Bailey, Lefeber, Roelands, Vanderborght and Meeusen2020; Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Hughes, Sullivan, Strutzenberger, Levick, Bisele and De Asha2021; Agrawal et al., Reference Agrawal, Gaunaurd, Kim, Bennett and Gailey2022; Hong et al., Reference Hong, Kumar, Patrick, Um, Kim, Kim and Hur2022; K. A. Lathouwers et al., Reference Lathouwers, Ampe, Díaz, Meeusen and De Pauw2022; Pröbsting et al., Reference Pröbsting, Altenburg, Bellmann, Krug and Schmalz2022; Elke Lathouwers et al., Reference Lathouwers, Baeyens, Tassignon, Gomez, Cherelle, Meeusen, Vanderborght and De Pauw2023);

-

2. Straight-line gradient walking (n = 7), including sagittal plane (incline/decline) (James and Stein, Reference James and Stein1986; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Strutzenberger, Kroell, Barnett and Schwameder2018; Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2018; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Strutzenberger and Schwameder2020; Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Altenburg, Schmalz, Kannenberg and Bellmann2022; Lathouwers et al., Reference Lathouwers, Ampe, Díaz, Meeusen and De Pauw2022) and frontal plane (camber) (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2017);

-

3. Quiet standing on slopes (n = 2) (Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Altenburg, Bellmann and Schmalz2017; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laszczak, Zahedi and Moser2018);

-

4. Parcourse (circuit of different terrain conditions) walking (n = 2) (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller, Howitt and Pros2007; Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Hughes, Sullivan, Strutzenberger, Levick, Bisele and De Asha2021);

-

5. Performance-based clinical outcome measures (n = 1) (Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Hughes, Sullivan, Strutzenberger, Levick, Bisele and De Asha2021), including the two-minute walk test, timed-up-and-go, and L-test of functional mobility.

Figure 5. Frequency of study tasks across reviewed literature.

While performance-based outcome measures and parcourse conditions could include elements of categories 1–3, these were categorized separately given their specific and unique protocols. The main characteristics of the unique protocols were extracted and classified by task and used medium (i.e., level ground, treadmill, ramp, etc.). These results were summarized and presented in Table 3. Across all the studies, the individual outcome variables were classified into 16 outcome variable groups and quantified, including biomechanical, spatiotemporal, and metabolic metrics (Figure 6), with nine articles (Boonstra et al., Reference Boonstra, Fidler, Spits, Tuil and Hof1993; Blumentritt et al., Reference Blumentritt, Scherer, Michael and Schmalz1998; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller, Howitt and Pros2007; McNealy and Gard, Reference McNealy and Gard2008; Sedki and Moore, Reference Sedki and Moore2013; Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2017, Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2018; Armannsdottir et al., Reference Armannsdottir, Tranberg, Halldorsdottir and Briem2018; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Cherelle, Roelands, Lefeber and Meeusen2018) that utilized patient-reported outcome measures to capture participant’s perception. A table with the list of individual outcome variables reported by each selected study and classified by outcome variable group is included as supplementary material (Supplemental Material 1: individual variables for each study). The frequency of individual outcome variables for the most frequently reported groups is included in Figures 7–10 (joint kinematics – Figure 7, spatiotemporal parameters – Figure 8, joint moments – Figure 9, and ground reaction forces – Figure 10). Key findings from each article are presented in Table 4.

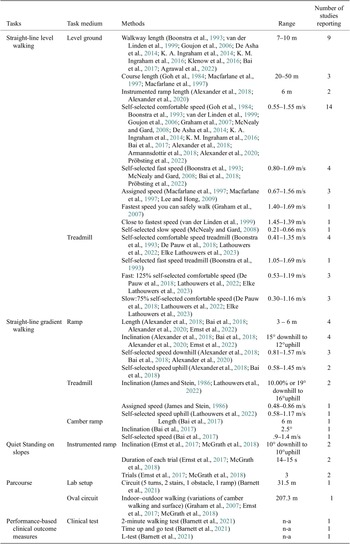

Table 3. Methodology Characteristics

Figure 6. Frequency of outcome variable groups. *Dead spot phenomenon metrics include variables that quantify a disruption in forward progression of plantar center-of-pressure under the prosthetic ankle-foot systems; foot evaluation refers to any questionnaire that intend to evaluate the participant’s perception of each condition such as Seattle Prosthesis Evaluation Questionnaire (PEQ) and custom-designed questionnaires; comfort score refers to questionnaires that evaluate the user’s perceived comfort of the prosthesis; pain rating refers to questionnaires that record the subject’s pain rating; metabolic variables include any variable related to metabolic consumption, that is, oxygen consumption and heart rate.

Figure 7. Frequency of individual outcome variables that are part of joint kinematics.

Figure 8. Frequency of individual outcome variables that are part of spatiotemporal parameters.

Figure 9. Frequency of individual outcome variables that are part of joint moments.

Figure 10. Frequency of individual outcome variables that are part of ground reaction forces.

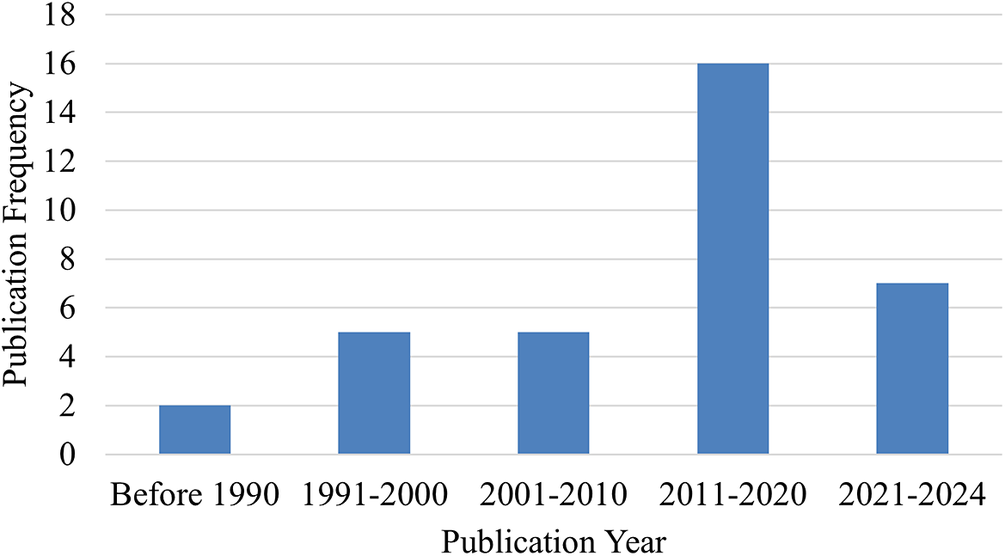

Table 4. Summary of main findings

4. Discussion

The aim of this review was to summarize the current knowledge about the effects of prosthetic ankle-foot mechanism design on gait and standing performance in TFPUs. The 35 articles included in this review covered numerical simulation studies and human performance studies that tested the effects of properties from both commercial and experimental ankle-foot mechanisms. To best summarize effects on performance, this discussion has been divided into sections according to the task for which performance was assessed (Figure 5).

4.1. Straight-line level walking

The majority of investigations included in this review (77%) included assessment for straight-line walking over level ground. Seven studies directly adjusted the loaded prosthesis behavior through: the addition of an articulation at the metatarsophalangeal joint (James and Stein, Reference James and Stein1986) (connecting the forefoot and midfoot through a laminated leaf spring), modifying the sagittal (unloaded) profile of the keel (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Kumar, Patrick, Um, Kim, Kim and Hur2022) (flat-toe shape versus curved-toe shape), or the addition of an ankle articulation (Goh et al., Reference Goh, Solomonidis, Spence and Paul1984; Lathouwers et al., Reference Lathouwers, Ampe, Díaz, Meeusen and De Pauw2022; Elke Lathouwers et al., Reference Lathouwers, Baeyens, Tassignon, Gomez, Cherelle, Meeusen, Vanderborght and De Pauw2023; Lee and Hong, Reference Lee and Hong2009; McNealy and Gard, Reference McNealy and Gard2008). Although different approaches, each technique ultimately affects the prosthetic ankle-foot ROS radius, which effectively provides a spatial mapping of how the leg is guided through stance (A. H. Hansen and Childress, Reference Hansen and Childress2010). The studies that facilitated the motion of the terminal rocker through either a metatarsophalangeal joint or curved toe generally reported improved gait dynamics: a metatarsophalangeal joint promoted forward progression of the plantar center of pressure (COP), hip motion symmetry, and hip control at mid-stance (James and Stein, Reference James and Stein1986), while a curved-toe shape delivered a smoother COP progression in early stance and longer load transfer to the contralateral limb (increased first double support) (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Kumar, Patrick, Um, Kim, Kim and Hur2022). The addition of an ankle articulation increased the ankle dorsiflexion–plantarflexion range of motion (McNealy and Gard, Reference McNealy and Gard2008) and provided a smoother ROS progression (Goh et al., Reference Goh, Solomonidis, Spence and Paul1984), which was considered better at mimicking the behavior of an anatomical ankle-foot complex. These results in TFPUs align with studies on TTPUs (A. H. Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Meier, Sessoms and Childress2006; M. J. Major et al., Reference Major, Twiste, Kenney and Howard2014; Vaca et al., Reference Vaca, Stine, Hammond, Cavanaugh, Major and Gard2022), which observed improvement in step length symmetry and reduction in the first peak of the GRF on the prosthetic limb with a closer-to-biological ROS radius. However, an ankle articulation in TFPUs also reduced prosthetic ankle power peaks (McNealy and Gard, Reference McNealy and Gard2008) compared to non-articulation and produced an external knee flexion moment while using a stance phase-controlled knee prosthesis (Lee and Hong, Reference Lee and Hong2009). Overall, an appropriate ROS radius may aid forward progression of TFPUs, but its effect on knee flexor-extensor moments requires consideration beyond that relevant for TTPUs.

Several studies compared commercial DR ankle-feet to non-DR ankle-feet (i.e., SACH, Multiflex) (Boonstra et al., Reference Boonstra, Fidler, Spits, Tuil and Hof1993; Macfarlane et al., Reference Macfarlane, Nielsen and Shurr1997; Macfarlane et al., Reference Macfarlane, Nielsen, Shurr, Meier, Clark, Kerns, Moreno and Ryan1997; Goujon et al., Reference Goujon, Bonnet, Sautreuil, Maurisset, Darmon, Fode and Lavaste2006; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller, Howitt and Pros2007; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller and Howitt2008; Pröbsting et al., Reference Pröbsting, Altenburg, Bellmann, Krug and Schmalz2022) and/or across different commercial DR ankle-feet designs (Blumentritt et al., Reference Blumentritt, Scherer, Michael and Schmalz1998; van der Linden et al., Reference van der Linden, Solomonidis, Spence, Li and Paul1999; Klenow et al., Reference Klenow, Kahle and Highsmith2016; Agrawal et al., Reference Agrawal, Gaunaurd, Kim, Bennett and Gailey2022) (i.e., varied by geometry, construction, or material). The mechanical benefits of the DR feet were similar between TTPUs and TFPUs (Goujon et al., Reference Goujon, Bonnet, Sautreuil, Maurisset, Darmon, Fode and Lavaste2006; Agrawal et al., Reference Agrawal, Gaunaurd, Kim, Bennett and Gailey2022), which include better energy management during gait and aiding the body’s transition into the swing phase. Compared to non-DR feet, a DR foot was observed to increase walking speed (Macfarlane et al., Reference Macfarlane, Nielsen and Shurr1997; Macfarlane et al., Reference Macfarlane, Nielsen, Shurr, Meier, Clark, Kerns, Moreno and Ryan1997; Goujon et al., Reference Goujon, Bonnet, Sautreuil, Maurisset, Darmon, Fode and Lavaste2006; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller, Howitt and Pros2007; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller and Howitt2008), improve temporal–spatial symmetry (Boonstra et al., Reference Boonstra, Fidler, Spits, Tuil and Hof1993; Goujon et al., Reference Goujon, Bonnet, Sautreuil, Maurisset, Darmon, Fode and Lavaste2006; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller, Howitt and Pros2007) (step length, stance time, and hip joint kinematics), increase prosthetic side hip power generation at pre-swing (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller, Howitt and Pros2007), and reduce metabolic energy consumption (Macfarlane et al., Reference Macfarlane, Nielsen, Shurr, Meier, Clark, Kerns, Moreno and Ryan1997; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller and Howitt2008). Across DR ankle-feet, there were observed differences between designs, such as slower forward COP progression velocity associated with an integrated spring design that would hinder limb advancement during stance (Klenow et al., Reference Klenow, Kahle and Highsmith2016); greater medial-lateral COP excursion during the mid-to-late stance associated with a split keel design to aid controlled body weight transfer to the contralateral limb during double support (Agrawal et al., Reference Agrawal, Gaunaurd, Kim, Bennett and Gailey2022); and a larger sound side first GRF peak associated with the Seattle LightFoot (van der Linden et al., Reference van der Linden, Solomonidis, Spence, Li and Paul1999). In early stance, a carbon fiber DR foot reduced sound side knee compensations when compared with other DR and non-DR designs (Blumentritt et al., Reference Blumentritt, Scherer, Michael and Schmalz1998), suggestive of TFPUs’ ability to generate a hip extensor moment to modulate the prosthetic knee external moment and stabilize the prosthetic leg. Overall, these articles identified several advantages of using DR feet over non-DR feet and how individual DR designs may affect certain gait features.

Uniquely, two studies compared solid DR ankle-feet with and without a hydraulic ankle unit (De Asha et al., Reference De Asha, Munjal, Kulkarni and Buckley2014; Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2017). The use of a hydraulic ankle was associated with a smoother progression of the plantar COP during stance, resulting in less body center-of-mass velocity reduction (De Asha et al., Reference De Asha, Munjal, Kulkarni and Buckley2014). Additionally, similar to the results of adding an ankle articulation (Goh et al., Reference Goh, Solomonidis, Spence and Paul1984; McNealy and Gard, Reference McNealy and Gard2008; Lee and Hong, Reference Lee and Hong2009), and mirroring results in TTPUs (De Asha et al., Reference De Asha, Munjal, Kulkarni and Buckley2013; De Asha et al., Reference De Asha, Munjal, Kulkarni and Buckley2014), the inclusion of a hydraulic ankle increased ankle-foot range of motion, self-selected walking speed, and bilateral symmetry in the ankle dorsiflexion–plantarflexion moment (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2017).

Besides studies comparing across purely passive-elastic components, four studies (Armannsdottir et al., Reference Armannsdottir, Tranberg, Halldorsdottir and Briem2018; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Cherelle, Roelands, Lefeber and Meeusen2018; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Serrien, Baeyens, Cherelle, De Bock, Ghillebert, Bailey, Lefeber, Roelands, Vanderborght and Meeusen2020; Pröbsting et al., Reference Pröbsting, Altenburg, Bellmann, Krug and Schmalz2022) compared walking performance between passive-elastic ankle-foot prostheses and microprocessor ankle-foot prostheses that deliver active plantarflexion (i.e., late stance power generation) (Pröbsting et al., Reference Pröbsting, Altenburg, Bellmann, Krug and Schmalz2022), active dorsiflexion (Armannsdottir et al., Reference Armannsdottir, Tranberg, Halldorsdottir and Briem2018), and variable ankle impedance across the stance phase to generate dorsiflexion–plantarflexion moments that resembled biological ankle dynamics (De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Cherelle, Roelands, Lefeber and Meeusen2018; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Serrien, Baeyens, Cherelle, De Bock, Ghillebert, Bailey, Lefeber, Roelands, Vanderborght and Meeusen2020). Delivery of active late-stance plantarflexion was associated with smaller sound side vertical GRF, external knee adduction moment, and external flexor moment compared to a SACH foot, but only a smaller external flexor moment compared to a DR foot (Pröbsting et al., Reference Pröbsting, Altenburg, Bellmann, Krug and Schmalz2022). Active dorsiflexion during the swing phase increased bilateral hip joint ROM symmetry and reduced prosthetic side hip circumduction, likely due to the increased ground clearance afforded by a dorsiflexed foot (Armannsdottir et al., Reference Armannsdottir, Tranberg, Halldorsdottir and Briem2018). Variable ankle impedance was found to increase perceived exertion compared to using a SACH foot during walking at a self-selected speed but revealed no other differences in gait kinematics and temporal–spatial parameters (De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Cherelle, Roelands, Lefeber and Meeusen2018; De Pauw et al., Reference De Pauw, Serrien, Baeyens, Cherelle, De Bock, Ghillebert, Bailey, Lefeber, Roelands, Vanderborght and Meeusen2020), which authors attributed to the unique walking mechanics of TFPUs that interrupted the active plantarflexion release mechanism of the prosthesis. Accordingly, the mixed results comparing DR to microprocessor-controlled ankle-feet may be related to the gait patterns specific to TFPUs involving the intact hip and prosthetic knee joints that manage ground loading during the transition phases (i.e., early stance phase and pre-swing), which are used as inputs for control schemes.

Finally, three studies (K. A. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2014; K. M. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2016; Pace et al., Reference Pace, Howard, Gard and Major2020) also included prosthetic knee joint adjustments in combination with different ankle-foot mechanisms on TFPU walking performance: comparing in-vivo different control strategies (i.e., swing initiation, increasing ankle stiffness, powered plantarflexion, and no active control) of an experimental combined knee-foot prosthesis (K. A. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2014; K. M. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2016) and analyzing in silico the effect of single-axis prosthetic knee joint center of rotation position and prosthetic ankle-foot stiffness (modeled as ROS curvature) (Pace et al., Reference Pace, Howard, Gard and Major2020). While using the experimental knee-foot prosthesis, active plantarflexion increased ankle power generation, similar to the effect of commercial powered feet on TFPUs (Pröbsting et al., Reference Pröbsting, Altenburg, Bellmann, Krug and Schmalz2022) and TTPUs (Mazzarini et al., Reference Mazzarini, Fantozzi, Papapicco, Fagioli, Lanotte, Baldoni, Dell’Agnello, Ferrara, Ciapetti, Molino Lova, Gruppioni, Trigili, Crea and Vitiello2023), while reducing prosthetic side braking via smaller average posterior GRF (K. M. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2016). Variable ankle impedance to mimic biological stance behavior was shown to increase walking speed (K. A. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2014), While aiding swing initiation through active plantarflexion and increased ankle stiffness not only increased gait speed but also reduced ipsilateral hip joint compensations (K. A. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2014; K. M. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2016). Similarly, the numerical simulation demonstrated that knee flexion–extension moments could be manipulated through combined adjustments of prosthetic knee alignment and ankle-foot mechanics to optimize the total leg design for limb stability during mid-stance and transition from late stance into swing (Pace et al., Reference Pace, Howard, Gard and Major2020). These results illustrate the important interaction effects of prosthetic ankle-foot and knee mechanisms on TFPU gait (K. A. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2014; K. M. Ingraham et al., Reference Ingraham, Fey, Simon and Hargrove2016; Lee and Hong, Reference Lee and Hong2009), which warrants further research to better inform prescription guidelines.

4.2. Straight-line gradient walking

Six studies investigated the effects of different prosthetic foot designs on gradient walking in TFPUs. One study modified elements of the ankle-foot mechanism by adding an articulation at the metatarsophalangeal joint of a single-axis foot and studied gait with and without the additional joint (James and Stein, Reference James and Stein1986). The metatarsophalangeal joint modified the dorsiflexion–plantarflexion motion to better resemble able-bodied dynamics and reduced an excessive second elevation of the hip to yield increased bilateral hip motion symmetry. The increased motion allowed the prosthetic foot to achieve full plantar contact with the surface with less generation of external plantarflexion moments but created an earlier knee flexion due to the anterior progression of the COP due to the increased dorsiflexion, which was perceived as unstable by the participants.

Studies compared the use of a hydraulic ankle DR foot to a solid ankle DR foot, reporting improvement in step length symmetry (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2017, Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2018), differences in ankle moment peaks (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2018), and reduction in the hip extension moment (Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Strutzenberger, Kroell, Barnett and Schwameder2018) during incline and decline walking, with a reduction in hip ROM (Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Strutzenberger, Kroell, Barnett and Schwameder2018; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Strutzenberger and Schwameder2020) during decline walking. The improvement in step length symmetry for TFPUs was associated with increased toe clearance due to the retained dorsiflexion of the hydraulic ankle during the swing phase, which has also been reported for TTPUs (Riveras et al., Reference Riveras, Ravera, Ewins, Shaheen and Catalfamo-Formento2020). Moreover, a hydraulic ankle DR foot achieved full plantar surface contact to the sloped surface, reducing the effect of ankle external moments due to the bending of the DR foot. The reduction in ankle external moments attributed to the GRF vector direction resulted in a smaller lever arm at the hip joint, so a smaller hip extension moment was needed to maintain limb stability. This effect does not appear to be limited only to sagittal plane slopes, since an improvement in step length symmetry was also identified when TFPUs walked on a coronal plane slope (i.e., camber walking) (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2017). Two manuscripts (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2018; Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Altenburg, Schmalz, Kannenberg and Bellmann2022) investigated hydraulic ankles by examining the effect of a microprocessor that controlled stance-phase articulation impedance. Compared to a solid ankle DR foot during incline walking, a microprocessor-controlled ankle-foot resulted in a reduction in the prosthetic knee extension moment (by 26% at vertical shank orientation) (Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Altenburg, Schmalz, Kannenberg and Bellmann2022), less hip joint ROM, and improved ankle moment symmetry (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2018). In summary, the hydraulic ankle-foot independent of the microprocessor control increased toe clearance and improved symmetry on different slopes compared to solid ankle DR feet, and the microprocessor control could further enhance the benefits of the hydraulic ankle (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Ewins, Crocombe and Xu2018) through more controlled management of ankle dorsiflexion–plantarflexion angle adaptation to different slopes.

Finally, as with level walking, an interaction between the prosthetic knee and ankle-foot components was reported across the gradient walking studies: an increase in knee flexor moment due to a solid ankle (Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Altenburg, Schmalz, Kannenberg and Bellmann2022), an increase in ankle-foot ROM due to the timing of the prosthetic knee flexion initiation (James and Stein, Reference James and Stein1986), and the modification of the GRF vector direction and COP progression by a knee with a gradual yielding mechanism (Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Strutzenberger and Schwameder2020). Again, further research is warranted on the interaction effects of different prosthetic knee and ankle-foot mechanisms during gradient walking to inform prescription guidelines for accommodating community ambulators that may traverse terrain beyond level ground walking.

4.3. Quiet standing on slopes

Two studies evaluated quiet standing on slopes by comparing DR feet with and without a hydraulic ankle joint (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Laszczak, Zahedi and Moser2018) and four commercially available microprocessor-controlled ankle-feet to a passive-elastic ankle-foot mechanism (Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Altenburg, Bellmann and Schmalz2017). The first study described how a hydraulic ankle with variable damping enables the ankle joint to adapt to a neutral position during slope standing, resulting in a reduction in compensatory strategies at the hip on the prosthesis side in TFPUs. Meanwhile, the second study determined that the ability of microprocessor feet to lock once fully adapted to the inclination and the increase ankle ROM improved bilateral weight distribution of TFPUs while standing on a decline slope. Both studies included evaluations while using a microprocessor-controlled knee with standing support assistance activated and deactivated. With standing support activated, differences in weight shifting and COP motion between hydraulic, microprocessor-controlled, and passive ankle-foot mechanisms were mitigated, suggesting that the knee mechanisms could affect hip compensations. This evidence suggests that ankle-foot mechanisms capable of adapting to different slopes could achieve better functionality during standing, but the combined effect of both prosthetic knees and ankle-feet should be considered as recommended with walking.

4.4. Parcourse

Evaluations of prosthesis users in scenarios reflecting the lived environment are often desirable to determine how prosthetic components function outside of controlled clinical or research laboratory settings. Two studies (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller, Howitt and Pros2007; Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Hughes, Sullivan, Strutzenberger, Levick, Bisele and De Asha2021) assessed TFPU mobility performance when traversing a parcourse that included level ground, slopes, stairs, obstacles, and turning. The results reported that a hydraulic ankle DR foot performed better than a solid ankle DR foot (Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Hughes, Sullivan, Strutzenberger, Levick, Bisele and De Asha2021), and there were no observed differences between a solid ankle DR foot and a multiaxial foot (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Datta, Heller, Howitt and Pros2007) when comparing completion times of a parcourse circuit. The hydraulic component aided TFPUs’ gait through adaptation to the different terrains, which again supported the other studies in this review that a hydraulic ankle DR foot may be beneficial to overall TFPUs’ ambulation more generally.

4.5. Performance-based clinical measures

Only one study (Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Hughes, Sullivan, Strutzenberger, Levick, Bisele and De Asha2021) compared user performance between a hydraulic ankle DR foot and a solid ankle DR foot in combination with a microprocessor-controlled and non-microprocessor-controlled prosthetic knee using established performance-based clinical outcome measures (two-minute walk test, timed up and go, and L-test). The hydraulic ankle DR foot improved performance across all clinical measures independent of the prosthetic knee, suggesting generally improved mobility capability of TFPUs. Additionally, this result aligns with the previously discussed gait studies where a hydraulic ankle DR foot could have meaningful benefits to TFPU mobility and complement the functionality of an appropriate prosthetic knee design.

5. Limitations

There are limitations to this literature review that should be considered when interpreting its results. Only one author extracted, classified, and summarized the information presented in this review, but resolving issues about the eligibility of articles and analysis of their results were performed in collaboration with three authors. Additionally, the authors did not perform a critical appraisal of research quality involving the selected articles. This review also inherits the limitations from the selected articles. All the human subject testing included in this review included ten participants or fewer. Therefore, as a result, the studies may have been underpowered, and the participant cohort may have limited generalizability. Finally, several studies were excluded because the grouped results included both TTPUs and TFPUs and precluded evaluation based on amputation level.

6. Conclusions

This review aimed to summarize the state of the literature describing the effects of prosthetic ankle-foot design on TFPU walking and standing performance and to serve as a complement to existing knowledge on TTPU effects. The reviewed literature utilized a variety of protocols, device comparisons, and outcome variables, rendering it challenging to summarize results. However, the results generally suggest many parallels with TTPUs, such as improvements in walking performance related to the incorporation of biological ROS features, energy storage and return capability, and especially a hydraulic ankle (active or passive) for adapting to non-level terrain, which also demonstrated benefits during quiet standing on slopes. The literature also emphasized the need to consider the interaction between prosthetic ankle-foot mechanics and the prosthetic knee, particularly how the ankle-foot component directs the GRF vector and plantar COP to affect knee moments, which stands apart from TTPUs who have the advantage of volitional management of intact knee joint moments. The interaction effects of prosthetic ankle-foot and knee mechanisms require additional research to develop a fuller understanding of how to best match an ankle-foot and knee design, so the two components synergistically operate to offer the best performance of both, thereby informing this critical aspect of TFPU clinical practice guidelines.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/wtc.2025.10037.

Data availability statement

Data can be made available to interested researchers upon request by email to the corresponding author.

Authorship contribution

MV, SG, and MM conceived and designed the review. MV, MB, SG, and MM developed the protocol. MV performed the first selection and retrieval of information. MV, SG, and MM addressed the inclusion and exclusion of articles under some uncertainty. MV, SG, and MM analyzed the results. MV, SG, and MM wrote the article.

Funding statement

This study was supported by the US Department of Defense (grant no. W81XWH1910447). The contents do not represent the views of the US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs, or the US Government.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests exist.

Ethical standard

Ethical statement was not applicable.