Introduction

Access to housing that is both affordable and adequate – offering safety, sufficient space, essential services, and manageable costs – is important for wellbeing, health, and financial and family stability (Rolfe et al., Reference Rolfe, Garnham, Godwin, Anderson, Seaman and Donaldson2020). However, both buying and renting such housing have become increasingly out of reach for lower-income households and are now also hardly affordable for many middle-class families, with homelessness on the rise, even in economically advanced countries (Preece et al., Reference Preece, Hickman and Pattison2020; Galster and Ok Lee, Reference Galster and Ok Lee2021; United Nations, 2021; Hilber and Schöni, Reference Hilber and Schöni2022; Housing Europe, 2023; Nasrabadi et al., Reference Nasrabadi, Larimian, Timmis and Yigitcanlar2024). According to the Eurostat (2024), housing expenses often make up the largest share of household expenditure, accounting for nearly one-fifth of disposable income. During periods of housing crisis, this burden can force households to delay or reduce essential spending on food, healthcare, and education (Coupe, Reference Coupe2021; Galster and Ok Lee, Reference Galster and Ok Lee2021). Thus, housing issues not only impact individuals’ living conditions but also intersect with other domains safeguarded by welfare policies, such as healthcare, education, and unemployment support (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2019). The recent report “The State of Housing in Europe” (Housing Europe, 2023) highlights rising costs of living, shortages in social and affordable housing, economic and energy crises, and limited public investment as the greatest drivers contributing to the housing crisis and increasing unaffordability across Europe. Additionally, the rising trend of financialization in the housing market – where properties are increasingly treated as investment assets rather than homes – further intensifies price pressures, reduces housing availability for residents, and exacerbates market instability, particularly affecting low- and middle-income households (Aalbers, Reference Aalbers2017; Çelik, Reference Çelik2024; Köppe and Byrne, Reference Köppe, Byrne, Greve, Moreira and Van Gerven2024). Not surprisingly, affordable and adequate housing is an important issue on the EU’s Urban and Social Policy Agenda (European Commission, 2018; Housing Europe, 2023).

Despite the EU’s expanding role in coordinating housing policies, housing markets across member states continue to face significant pressure. This raises the question: can EU-level policy coordination effectively address the complex and multifaceted challenges reshaping housing markets, including economic factors like rising housing costs, inflation, and recession, as well as demands for sustainable housing, demographic shifts (e.g., ageing and social segregation), and increasing regional inequalities? The complexity of these issues, combined with each country’s unique economic, social, and regulatory context, makes it challenging to objectively assess and compare housing policies and systems across countries. Nevertheless, a comprehensive understanding gained from general overviews and international comparisons could provide valuable insights into the diverse housing pathways and common patterns in housing provision models across the EU, potentially guiding more effective and tailored solutions. In other words, comparing housing-related challenges across Europe not only reveal shared and divergent patterns, but may also inform the design of housing policies tailored to national needs yet informed by the international context.

The aim of this study is to provide an overview and comparison of housing provisionFootnote 1 across EU member states. The study focuses on three key domains: availability, affordability, and adequacy, as well as the government efforts to improve housing provision. Using OECD and Eurostat data from 2010 to 2021, we examine governments’ roles in housing provision and assess availability, affordability, and adequacy, while also exploring their interrelationships. Using hierarchical cluster analysis, we identify groups of countries with similar housing sector characteristics and visualize the results with cartographic techniques. This study provides a comparative overview of housing provision across the EU, highlighting the relative scale of these issues in each country. It also uncovers that welfare models – liberal, social-democratic, conservative-corporatist, Mediterranean/Southern European and post-socialist/hybrid/transition – are closely linked to the provision of housing.

Literature review

Comparative housing research in Europe

As EU housing markets face complex challenges affecting millions of people, scholarly literature on the housing issues is expanding, with comparative European studies also increasing but still limited.Footnote 2 For example, among these comparative studies, a handful focus on affordability (e.g., Frayne et al., Reference Frayne, Szczypińska, Vašíček and Zeugner2022; Eurofund, 2023; Valderrama et al., Reference Valderrama, Gorse, Marinkov and Topalova2023; Hick et al., Reference Hick, Pomati and Stephens2024), where all emphasize the persistent challenges of housing affordability across Europe, particularly in large metropolitan regions (Reichle et al., Reference Reichle, Fidrmuc and Reck2023). Studies often relate housing affordability challenges to housing market financialization (e.g., Aalbers, Reference Aalbers2017; Hick and Stephens, Reference Hick and Stephens2023; Çelik, Reference Çelik2024; Köppe and Byrne, Reference Köppe, Byrne, Greve, Moreira and Van Gerven2024), and they find that this process exacerbates affordability issues by prioritizing profit-driven investments, inflating property prices, and reducing access to affordable housing stock throughout the EU. Housing shortages, driven by factors like population growth, urbanization, urban planning, and housing market dynamics, remain a pressing issue in many European countries, impacting affordability, accessibility, and quality of life (Hallett and Hallett, Reference Hallett, Hallett and Hallett2021; OECD, 2021). This gap between supply and demand is contributing to rising property prices, worsened affordability, and heightened competition in both rental and homeownership markets, particularly in major cities (European Parliament, 2025). In light of these challenges, large housing estates have attracted attention in both earlier research (e.g., Dekker and Van Kempen, Reference Dekker and Van Kempen2004; Musterd and Ronald, Reference Musterd and Ronald2007) and more recent studies (e.g., Hess et al., Reference Hess, Tammaru and Van Ham2018; Hess and Tammaru, Reference Hess and Tammaru2019). These studies examine evidence on the changing conditions of large housing estates, showing that many mid-20th-century estates in Europe – once seen as solutions to urban issues – have become disadvantaged areas, particularly for low-income households and ethnic minorities. Although large housing estates offer affordable housing, they now face challenges such as physical decay, safety concerns, high unemployment, peripheral locations, and increasing stigmatization, undermining the goal of ensuring adequate housing provision. This issue is closely linked to increasing housing inequality, as shown by Nasrabadi et al. (Reference Nasrabadi, Larimian, Timmis and Yigitcanlar2024), whose comprehensive literature review from around the world spanning four decades, highlights that interconnected factors – such as race, ethnicity, income, and education – strongly affect housing inequality. Income inequality is a primary driver of housing inequality, as financial resources play a crucial role in the housing market, offering greater choice in selecting a home and neighbourhood. As a result, higher income inequality leads to greater residential segregation between affluent and disadvantaged groups (Musterd and Ostendorf, Reference Musterd and Ostendorf1998). Comparative research on residential segregation (e.g., Tammaru et al., Reference Tammaru, Marcińczak, Van Ham and Musterd2016; Haandrikman et al., Reference Haandrikman, Costa, Malmberg, Rogne and Sleutjes2021) concludes that the widening spatial divide between the rich and poor in European capital cities poses a threat to social stability. These studies and many other researchers in the field agree that residential segregation is influenced by factors such as income inequality, welfare regimes, labour market structures, housing systems, migration patterns, and residential mobility.

Although housing studies, as reviewed above, provide valuable knowledge from different perspectives and across geographical contexts, it is difficult to integrate this information into a comprehensive understanding of housing issues. For example, Erdogdu (Reference Erdogdu2011) highlights that housing is a complex, difficult-to-theorize topic, interconnected with economic, social, demographic, and cultural contexts, requiring both macro and micro considerations along with diverse methodologies, including historical, descriptive, empirical, and qualitative analyses. Similarly, Nasrabadi et al. (Reference Nasrabadi, Larimian, Timmis and Yigitcanlar2024) argue that existing literature tends to isolate issues like affordability and access, ignoring their broader socio-cultural and economic context. Furthermore, the debate in housing studies is enriched by research that critically examines key concepts and methodologies in the field. For example, Stephen Ezennia and Hoskara (Reference Stephen Ezennia and Hoskara2019) review the literature on housing affordability and its measurement, highlighting methodological weaknesses. Haffner and Hulse (Reference Haffner and Hulse2021) build on this by offering a fresh perspective on the concept of “housing affordability” and emphasizing the need for improved measurement approaches. Meanwhile, James et al. (Reference James, Daniel, Bentley and Baker2022) identify four key uses of “housing inequality” in the literature – an outcome, an experience, a product, and a construct, offering a framework to understand housing’s multifaceted roles, distribution, and societal impacts. Moreover, the book by Stephens and Norris (Reference Stephens and Norris2014) tackles the challenges faced by comparative housing research, emphasizing the main barriers that hinder it from reaching the same methodological and theoretical depth as other areas of comparative social science. Finally, housing studies (e.g., Kucharska-Stasiak et al., Reference Kucharska-Stasiak, Źróbek and Żelazowski2021; Hilber and Schöni, Reference Hilber and Schöni2022; Nasrabadi et al., Reference Nasrabadi, Larimian, Timmis and Yigitcanlar2024) criticize an attempt to adopt a one-size-fits-all approach, arguing that a uniform EU housing policy is neither feasible nor effective. Instead, policymakers should implement localized strategies tailored to groups of countries with similar conditions.

This study contributes a comparative, data-driven analysis of housing provision across EU member states, highlighting patterns in availability, affordability, and adequacy, and providing insights to inform targeted housing policies. By integrating multiple domains of housing provision and using harmonized data from OECD and Eurostat (2010–2021), the study overcomes some of the challenges identified in previous research, such as the fragmentation of issues and the difficulty of cross-country comparisons. The use of hierarchical cluster analysis and cartographic visualization allows for systematic grouping of countries with similar housing characteristics, addressing the need for comprehensive, comparable, and interpretable analysis. Furthermore, by examining the interrelationships between availability, affordability, and adequacy, this study captures the broader socio-economic context of housing, moving beyond isolated measures such as price or shortage.

European Union’s role in housing policy

Across the EU, housing policy is primarily managed by national governments; however, growing challenges across various spheres, such as immigration, war-related instability, economic recession, inflation, regional inequalities, ageing populations, and increasing social segregation, are placing significant pressure on housing markets. In response to growing housing-related challenges, the EU has increasingly acknowledged the need for coordinated action, leveraging its influence through funding, regulatory frameworks, and policy coordination to support housing initiatives across member states.

Housing policy has been increasingly incorporated into the EU’s policy agenda through various measures (see Kucharska-Stasiak et al., Reference Kucharska-Stasiak, Źróbek and Żelazowski2021). For example, the EU addresses housing through the European Pillar of Social Rights, promoting social housing, housing assistance, and services for the homeless (Housing Europe, 2023; European Commission, 2023). Housing rights are also addressed in the Charter of Fundamental Rights, emphasizing housing assistance as vital to reducing poverty and social exclusion (European Union, 2012). In 2021, the European Parliament called for an integrated housing strategy to improve housing availability and affordability across Member States (European Parliament, 2021). During her 2024 re-election campaign, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen highlighted housing as a key priority for the next Commission (Eunews, 2024; Politico, 2024). Following her victory, she appointed the EU’s first-ever Commissioner for Housing to develop a comprehensive housing strategy (European Commission, 2024). These efforts reflect the EU’s increasing commitment to making housing one of the core pillars of its social agenda, recognizing the urgency of coordinated action to address disparities and affordability challenges across Member States.

With global housing challenges intensifying due to housing affordability issues, sustainability demands, and demographic shifts, the EU’s unique collaborative framework serves as a unique platform for developing shared solutions. Yet, coordinated EU efforts appear to have little impact on reducing housing market tensions or disparities across Member States, likely due to the wide variation in housing systems, which reflect each country’s unique demographic, economic, and environmental conditions (Kucharska-Stasiak et al., Reference Kucharska-Stasiak, Źróbek and Żelazowski2021).

Welfare models and housing provision

Housing provision is closely intertwined with broader welfare systems, as social policies play a role in shaping the availability, affordability, and adequacy of housing (Flynn and Montalbano, Reference Flynn and Montalbano2024). Through the lens of welfare regime theory (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990), which classifies regimes into liberal, conservative-corporatist, and social-democratic types – later extended to include Southern European/Mediterranean model (Ferrera, Reference Ferrera1996) to capture the distinctive features of Southern Europe, and the post-socialist/hybrid regime (Aidukaitė, Reference Aidukaitė2004; Fenger, Reference Fenger2007), highlighting the specific trajectories of Central and Eastern European countries – these welfare models differ in how they balance state intervention, market forces, and family support, profoundly influencing national housing outcomes (van Kersbergen and Vis, Reference van Kersbergen and Vis2013) and social inclusion (Brown and Brik, Reference Brown and Brik2024).

Different welfare regimes give rise to distinct housing regimes – shaping whether housing policy leans more toward social allocation, market liberalization, or hybrid forms. The value of regime typologies has been a frequent topic of discussion in housing research, a field where cross-country classifications have proven especially useful for comparative analysis. The study of Flynn and Montalbano (Reference Flynn and Montalbano2024) systematically reviews housing regime typologies, showing that while their explanatory power is debated, they remain relevant in comparative housing research when understood from a historically grounded perspective. Similarly, Blackwell and Kohl (Reference Blackwell and Kohl2019) criticize static welfare-housing typologies as cross-sectional snapshots that ignore historical contingencies, arguing that links between welfare regimes, homeownership rates, and mortgage debt are often temporary and shaped by path-dependent factors like evolving housing finance systems. They advocate historicized typologies incorporating regional variations and pre-welfare trajectories (e.g., bond-based financing favouring rentals in eastern and northern Europe versus deposit-based models promoting ownership in Anglo-Saxon contexts) to better capture lasting patterns. This perspective encourages a more dynamic understanding of housing diversity in Europe.

Furthermore, one of the major focuses of housing research is the ongoing debate over the relationship between housing provision and broader welfare systems (see Clapham, Reference Clapham2020). This discourse (Kemeny, Reference Kemeny2001, Reference Kemeny2005; Hick and Stephens, Reference Hick and Stephens2023; Grander and Stephens, Reference Grander and Stephens2024) emphasizes the integration of housing into the welfare policy framework, alongside healthcare, education, and unemployment support. While the critical role of housing within this broader framework is widely acknowledged, its exact contribution remains unclear. Despite numerous forms of housing support, it is rarely regarded as a universal form of public provision (Kemeny, Reference Kemeny2001). The key to the issue lies in the housing sector’s deep entanglement with market interests, which complicates its integration into welfare systems. Housing policy aims to mitigate these market forces, with Lund (Reference Lund2011) asserting it as the state’s efforts to modify housing markets. Thus, on one hand, housing is treated as a market commodity, subject to buying, selling, and investment. On the other hand, it is also recognized as a fundamental social right, ensuring shelter and security for individuals and families (Bengtsson, Reference Bengtsson2001).

Regardless of welfare models or housing regimes, housing-related tensions are evident across all European countries, each struggling to balance market dynamics with social rights. This study does not aim to challenge housing regime typologies or establish clear links between welfare state models and housing provision. Instead, it examines housing challenges in each EU country, focusing on the interplay between availability, affordability, and adequacy.

Methodological approach

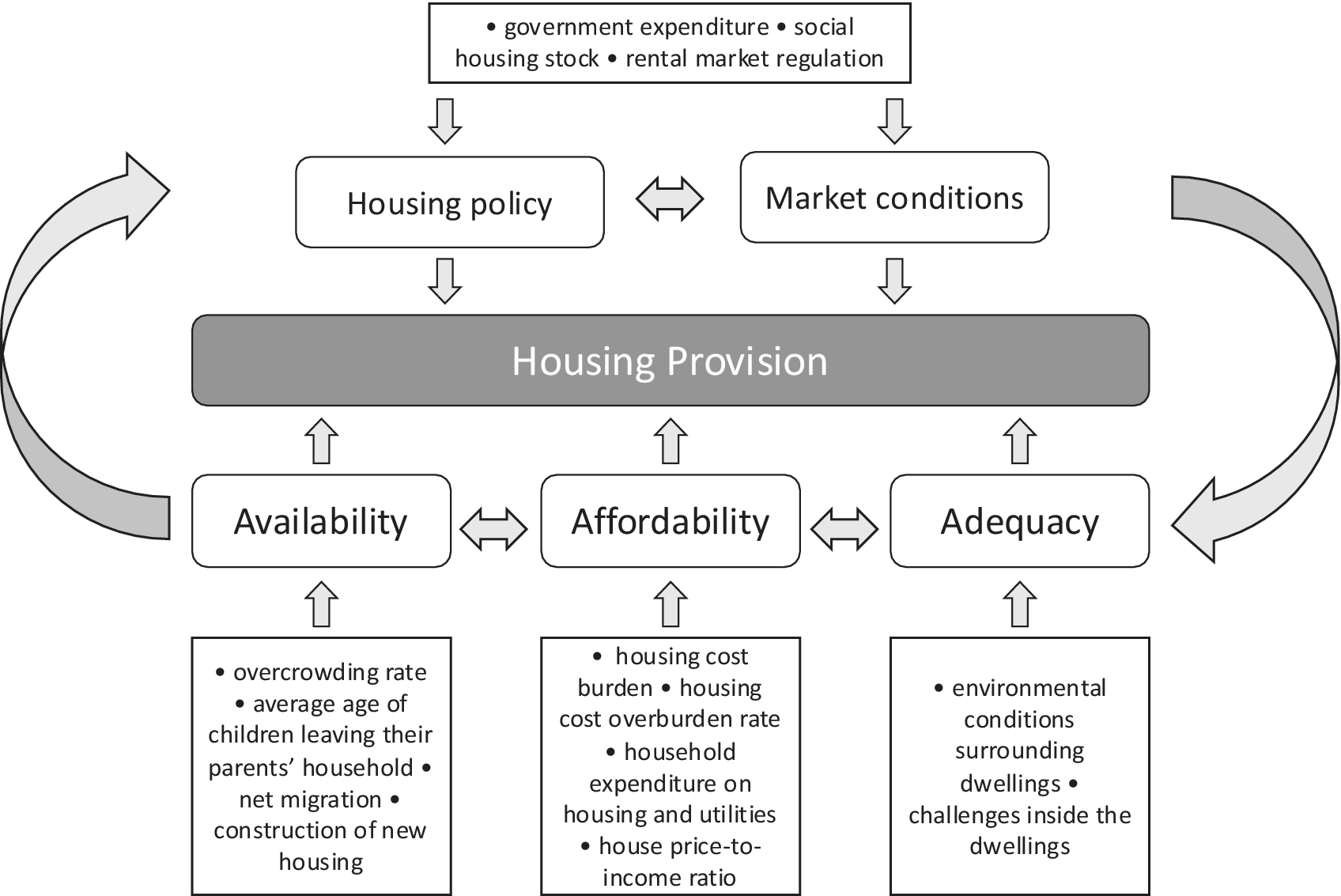

Figure 1 visually represents the conceptual framework of this study. The housing provision – understood as the process of supplying, allocating, and maintaining housing to ensure access to safe, affordable, and suitable homes – largely depends on the interplay between housing policy and market conditions, where housing policy plays an important role in regulating market forces and influencing household choices (Doherty, Reference Doherty2004; Clapham, Reference Clapham2006; Lund, Reference Lund2011). Meantime, the state of the housing provision can be accessed by considering the key aspects of the housing domain: availability, affordability, and adequacy, where

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for the housing provision and selected indicators (authors’ elaboration).

Availability shows whether there is enough or a lack of (a specific type of) housing. In the context of housing studies, it is often associated with the shortage of housing. The availability of housing is influenced by factors such as urbanization, immigration, and the construction of new housing.

Affordability assesses whether households, especially low-income ones, can access housing at a reasonable cost. When a large portion of the population cannot afford market-priced housing and lacks alternatives like social housing, affordability becomes a critical issue.

Adequacy refers to housing quality, meaning the physical and functional features that ensure security, stability, and dignity, such as sufficient space, proper lighting, temperature, structural safety, and access to clean water and sanitation. Adequacy also extends to access to essential services (e.g., healthcare, education, and infrastructure), which together support residents’ well-being (United Nations, 2009).Footnote 3

These three domains are interrelated, and all are essential for assessing housing provision. For example, housing may be available but unaffordable or affordable but inadequate. Such scenarios indicate gaps in effective housing provision.

In this study, we assess housing provision in EU countries using various indicators, with data sourced from international housing databases (OECD and Eurostat). As no single indicator directly measures housing provision, we conducted a detailed overview of available data and then selected and grouped multiple indicatorsFootnote 4 to capture the domains of availability, affordability, adequacy, and the government’s role in the housing sector (resulting from the interplay between housing policy and market conditions). We analyse country-level data from 2010 to 2021 using a consistent, comparative approach across the selected indicators. Hierarchical cluster analysis is applied to identify groups of countries with similar housing characteristics within the defined domains. For each domain, we deliberately construct three distinct clusters – a methodological decision guided by the need to balance granularity and interpretability. This number of clusters effectively captures core geographical and socio-economic divisions (Northern/Western, Southern, and Eastern Europe) and allows for avoiding the excessive fragmentation or overcomplication that could arise from higher cluster counts (e.g., four or more, which preliminary tests showed led to less coherent or interpretable groupings). The clusters are subsequently visualized using cartographic techniques, which provide a clear overview of how housing characteristics vary across Europe. Overall, this study presents a comparative analysis of EU countries, providing a relative assessment in which each indicator reflects variation among countries. By comparing the indicator values across countries, we aim to identify key differences and reveal general patterns in housing provision.

This study faces some challenges that may impact the reliability of the research findings. First, the diversity of housing policies, forms of housing support, and varying definitions – such as social housing or affordable housing – complicates comparisons across EU countries. Second, data availability and quality differ across countries (Housing Europe, 2023), limiting comparative studies at lower spatial levels. As a result, this study uses national-level data, which presents challenges due to substantial regional differences, especially between urban and rural areas. Urban areas often experience housing shortages driven by population growth and economic migration, while rural areas face high vacancy rates and underinvestment. These areas differ significantly, and distinct policies are applied to address the unique challenges of each. Third, the clusters are based on average values over the entire period, which smooths year-to-year anomalies to highlight long-term trends; however, this approach obscures short-term changes and subtle shifts in housing characteristics. Fourth, there is a time-lag between policy interventions – such as recent EU efforts to promote green housing or tackle inequality – and their measurable outcomes, a critical issue in today’s fast-evolving housing debate (Frayne et al., Reference Frayne, Szczypińska, Vašíček and Zeugner2022). Although we acknowledge that our methodological approach has limitations, the primary goal of this paper is to provide a comparative overview of the housing provision in the EU countries. While more granular territorial or individual-level data could deepen insights into specific issues, it might compromise the broad perspective essential to understanding the multifaceted nature of Europe’s current housing challenges.

Results

This section compares housing issues across EU countries, focusing on availability, affordability, and adequacy. The analysis provides insights into housing provision and the effectiveness of government efforts. It also provides insights into how different welfare models affect the interplay between these domains, highlighting the factors shaping housing outcomes and the differences in housing provision among EU member states. The paper presents generalized results, with detailed statistics on individual indicators, their changes over time, and additional results available in the Supplementary Material, along with definitions and data sources.

The role of governments in housing provision

All European countries have housing policies that aim to improve the living conditions of those in need through various state-provided benefits and services. In many cases, governments play a crucial role in ensuring adequate and affordable housing, particularly for low-income households (European Parliament, 2021). One way to assess the government’s role in housing provision is by examining the share of GDP allocated to housing-related developments.Footnote 5 Over the past two decades, government spending on housing has fluctuated, averaging between 1% and 0.5% of GDP across EU member states. While expenditure was around 0.9% in the 2000s, it steadily declined to a low of 0.5% in 2017. However, this trend has recently reversed, with spending rebounding to 1.0% in 2022 (Eurostat, 2025; see Supplementary Material). Previous studies (Aidukaitė, Reference Aidukaitė2004; Doherty, Reference Doherty2004; Clapham, Reference Clapham2006; Arbaci, Reference Arbaci2007; Tsenkova and Polanska, Reference Tsenkova and Polanska2014) have observed a trend of gradual withdrawal by the state from the housing sector across many EU countries. However, as this process is uneven in scale and speed, and housing policy still differs remarkably between countries (Doherty, Reference Doherty2004; Kettunen and Ruonavaara, Reference Kettunen and Ruonavaara2021; Dewilde, Reference Dewilde2022), the evidence of the state’s withdrawal from the housing sector is not conclusive. Moreover, there is a growing consensus that improving housing affordability necessitates policies aimed at increasing housing supply (Frayne et al., Reference Frayne, Szczypińska, Vašíček and Zeugner2022). The positive effects of redistributive housing allowance and rent regulations on the living and housing conditions of low-income households and renters in the EU have been demonstrated in a recent study by Dewilde (Reference Dewilde2022). Furthermore, Kettunen and Ruonavaara (Reference Kettunen and Ruonavaara2021) studied rent regulations and concluded that the housing provision systems in Europe are not entirely neoliberalized, emphasizing the significance of rent regulation policies. Therefore, an essential factor to consider when assessing the government’s role in housing provision is the extent of regulation within the rental market.

Lastly, in many countries, a key component of the government’s role in housing provision is social housing,Footnote 6 which is essential for supporting the most vulnerable populations. In countries where social housing is limited, additional measures are often implemented to assist lower-income individuals in accessing affordable housing. This is evidenced by our finding that the correlation between government expenditure on the housing sector and the share of social rental housing stock is statistically insignificant (r = −.286, p = .149). The absence of a relationship may be attributed to two underlaying reasons. First, government expenditure includes financial support for homebuyers, such as subsidized mortgages and housing allowances, which may be prioritized in countries where social housing is scarce. Therefore, countries with a higher share of social housing may spend less on homebuyer support or housing allowances, whereas those with less social housing need to invest more in increasing its share or providing alternative housing support. Second, different types of social rental housing providers exist, with varying levels of state funding.

In this study, we quantitatively assess the extent of government commitment to housing support across EU countries using three key indicators: government spending on housing-related developments as a percentage of GDP, the proportion of social rental housing within the total housing stock, and the regulation of the rental market. Figure 2 presents maps illustrating each of these indicators individually, along with an aggregated assessment derived from the hierarchical clustering method. The blue cluster, which includes Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Austria, is characterized by relatively low government expenditure on housing, but a large social rental housing stock and a highly regulated rental market. The red cluster, which includes Latvia, Croatia, Romania, and Bulgaria, exhibits the opposite characteristics: higher government expenditure on housing, but a smaller social housing stock and low regulation in the rental market. The largest group of countries falls into the remaining yellowish cluster, which shows intermediate characteristics across all assessed indicators. Thus, the clustering analysis reveals three distinct groups of EU countries based on their government strategies in housing provision.

Figure 2. Government spending on housing-related developments, social rental housing share, and rental market regulation (grayscale), and an aggregated assessment (in colour) using the hierarchical clustering method to classify countries based on the government’s role in housing provision (2010–2021) (authors’ elaboration based on OECD and Eurostat data).

It is important to acknowledge that other factors also play a role in shaping housing policies. One key factor is the housing ownership structure, which is shaped by a country’s historical development. Our findings show that countries with higher homeownership rates tend to have higher government spending on housing, likely through mortgage subsidies, reflecting a policy focus on promoting homeownership. This is supported by a positive and significant correlation between government expenditure and homeownership (r = .308, p = .118), while the correlation with tenancy is negative and weaker (r = −.265, p = .181). Conversely, a higher share of social housing reduces the need for homeownership. This highlights the interplay between housing tenure structures and government intervention. Additionally, housing outcomes are shaped by a variety of nuanced factors, including state tax policies, access to credit, labour market conditions (such as gendered effects stemming from women’s typically lower wages), regional planning regulations, and inheritance policies. Collectively, these factors can either reinforce or alleviate disparities in housing accessibility, affordability, and quality.

Housing availability

Housing provision relies on multiple domains, one of which – housing availability – depends on the supply of housing that meets the diverse needs of the population. Now, we will assess housing availability in EU countries using selected indicators: overcrowding rate, average age of children leaving their parents’ household, net migration, and construction of new housing (Figure 3; see Supplementary Material for indicator details).

Figure 3. Housing availability: overcrowding rate, average age of children leaving their parents’ household, construction of new housing, and net migration (in greyscale), and an aggregated assessment (in colour) using the hierarchical clustering method (2010–2021) (authors’ elaboration based on Eurostat data and EU-SILC survey).

Overcrowding rate varies significantly across Europe, with a clear contrast between Eastern and Western countries (Figure 3), although there is a general trend towards decline and convergence (see Supplementary Material). The overcrowding rate in Central and Eastern (CEE) countries was previously much higher but declined significantly over the last decade due to declining populations and demographic ageing (see e.g., Szafrańska et al., Reference Szafrańska, Coudroy de Lille and Kazimierczak2019) as well as due to growing economies and large-scale residential construction. In Western Europe, the overcrowding rate had traditionally been lower due to intense urbanization, industrialization, and mass housing construction after World War II. However, in the last decade, these rates have slightly increased, especially in large cities experiencing steady population growth due to immigration, presenting a growing challenge of housing shortages (Eurofund, 2023).

Our analysis revealed notable relationships. For example, overcrowding positively correlates with homeownership rates – the higher the homeownership, the greater the overcrowding (r = .458, p = .016), while a larger rental sector, public or private, is negatively associated with overcrowding (r = −.597, p = .001). Thus, high homeownership in CEE and Mediterranean countries contributes to greater overcrowding, whereas larger rental sectors in Nordic and Continental Europe alleviate it. Overcrowding also appears tied to the age children leave their parental home, with later departures associated with higher overcrowding rates (r = .345, p = .078). In Northern and Western Europe, children leave home earlier, while in other regions, they stay with parents longer. In CEE and Mediterranean countries, a limited rental sector restricts housing availability and affordability, steering young people toward homeownership – a costlier, slower option than renting – while prolonged stays with parents, due to these constraints, exacerbate overcrowding when neither moving out nor owning is feasible (see Simón-Moreno et al., Reference Simón-Moreno, Heitkamp, Pereira and Siatitsa2024 on Southern Europe). Housing availability, particularly shortage, is directly influenced by supply and demand dynamics, and can be assessed through indicators like construction volumes and net migration. Our analysis incorporates these metrics to provide a better overview of housing availability. Yet, the complex relationship between construction volumes and net migration, and their impact on housing shortages, requires more extensive research, beyond the scope of this study.

Based on all four indicators, EU countries can be classified into three clusters according to relative housing availability (Figure 3). Notably, individual indicators vary greatly and may contradict each other, making this aggregated outcome a relative measure rather than an absolute ranking of housing availability. Having said that, the aggregated results indicate that housing availability is highest in Finland, Denmark, Ireland, Luxembourg, and Cyprus (blue cluster). In contrast, CEE countries, Italy, and Sweden exhibit the lowest housing availability (red cluster). The remaining countries fall into an intermediate category.

Housing affordability

Housing affordability is another important feature needed to ensure broad accessibility and reduce financial strain across EU households. After examining available indicators – capturing different dimensions of housing affordability – we selected four that best reflect the situation in EU countries: housing cost burden, housing cost overburden rate, household expenditure on housing and utilities, and house price-to-income ratio (Figure 4; see Supplementary Material for indicator details).

Figure 4. Housing affordability: housing cost burden, housing cost overburden rate, household expenditure on housing and utilities, and house price-to-income ratio (in greyscale), and an aggregated assessment (in colour) using the hierarchical clustering method (2010–2021) (authors’ elaboration based on Eurostat and OECD data).

Housing cost burden refers to the share of disposable income spent on housing expenses like mortgages, rent, utilities, and property taxes. Western and Northern European countries have considerably higher housing cost burdens compared to CEE countries, largely due to tenure composition differences – higher home ownership rates are associated with lower housing cost burdens. The greatest burden falls on households in countries with a high proportion of market-priced rentals, while the lowest burden is in countries with a high share of owners without outstanding mortgages (see Supplementary Material; Pittini et al., Reference Pittini, Koessl, Lakatos and Ghekiere2017; Dewilde, Reference Dewilde2022; Hilber and Schöni, Reference Hilber and Schöni2022). Generally, renters face higher housing costs compared to mortgage holders in most countries, and this gap is particularly pronounced in Sweden, Finland, and the Netherlands, whereas the opposite is true in Croatia, Malta, and Latvia. In Luxembourg, France, Ireland, Slovenia, and Czechia, there is almost no difference in affordability between renting and owning. As documented in the literature (Scanlon et al., Reference Scanlon, Whitehead and Fernández Arrigoitia2014; Pittini et al., Reference Pittini, Koessl, Lakatos and Ghekiere2017), low-income residents are more likely to be tenants, creating a vicious circle from which it is difficult for the low-income population to escape (Tammaru et al., Reference Tammaru, Knapp, Silm, Van Ham and Witlox2021). Between 2010 and 2021, there have been significant changes in the housing cost burden, with some countries experiencing a decrease (e.g., Sweden, Lithuania, Croatia) while others have seen an increase (e.g., Malta, Luxembourg, Poland). As there is no clear geographical pattern, these changes may be related to economic factors such as increasing wages, rising housing prices, economic restructuring, etc.

Another indicator – housing cost overburden rate – shows the percentage of households spending over 40% of their income on housing. In 2021, the EU average was around 7%, with Greece having an exceptionally high overburden rate, where nearly one-third of households spent at least 40% of their disposable income on housing. Over the past decade, while housing affordability pressures eased in most countries, they intensified in Greece and Bulgaria, highlighting increasing barriers to securing adequate housing.

In the EU, household spending on housing costs and utilities, like water and electricity, averages a quarter of household income, with relatively small variation across countries and over time. It is interesting to find that prolonged living with parents is associated with significantly lower housing expenditures (r = −.444, p = .020), most likely due to shared costs. However, this may also lead to overcrowding in the household. Additionally, higher household expenditure is linked to a greater proportion of social rental housing (r = .437, p = .023), which is typically occupied by low-income individuals. Thus, although low-income pay relatively little for housing, the cost of maintaining housing still requires a large portion of their income. This implies that despite considerable housing assistance, affordability remains a significant challenge.

Our last indicator – the house price-to-income ratio – reveals a clear geographic divide: Western European countries are in a more favourable position than Eastern European countries. Higher ratios, typical in Eastern and Southern European countries, indicate that house prices are relatively high compared to incomes, requiring more years of earnings to purchase a home. In contrast, lower ratios in Western European countries suggest that people can save for a home more quickly. Over the decade, the differences between countries have narrowed. The gap between the highest and lowest ratios in 2021 was smaller than it was in 2010. In 2010, less economically strong countries faced higher ratios (indicating lower affordability), but by 2021, this trend had shifted. It is important to note that the price-to-income ratio contrasts with other affordability measures, highlighting that overall housing affordability depends not only on purchase costs but also on ongoing expenses such as maintenance, taxes, and utilities. Additional factors – such as mortgage availability and household savings rates – can also influence affordability.

Figure 4 summarizes housing affordability using cluster analysis. The red cluster, indicating lower affordability, includes countries in Northern and Continental Europe, which are among the EU’s strongest economies and have more developed housing policies with greater state intervention. In contrast, the blue cluster represents countries with higher affordability, and includes the Baltic states, Poland, Slovenia, Croatia, Ireland, and Portugal. These countries generally have weaker economies and more liberalized housing policies with less state intervention than the red cluster countries. The yellowish cluster represents countries with moderate housing affordability, and such countries are spread across different geographic regions. It is worth noting that, although saving for a home remains more difficult in Eastern and Southern Europe, overall housing affordability poses greater challenges in the Nordic and Western countries.

Housing adequacy

Housing adequacy is another important factor to examine when assessing housing provision. It refers to housing that meets acceptable quality standards, ensuring residents have safe, comfortable, and healthy living conditions. In this study, we take into account environmental conditions surrounding dwellings (such as noise, pollution, grime, crime, etc.) as well as challenges inside the dwellings themselves (including leaking roof, damp walls, inadequate heating, and the absence of a bath, shower, or indoor toilet). Figure 5 presents maps depicting both individual indicators (highlighting disparities more clearly) and an aggregated assessment.

Figure 5. Housing adequacy: environment-related indicators, dwelling-related indicators, and an aggregated assessment using the hierarchical clustering method (2010–2021) (authors’ elaboration based on Eurostat data).

The results in the maps show that housing adequacy varies across countries, with no clear geographical pattern, and each country faces a unique combination of challenges. Our findings indicate that residents in countries with higher population densities, as well as some southern European countries, express greater levels of concern regarding environmental issues. In contrast, Eastern and to some extent Southern European countries experience higher rates of dwelling deprivation compared to other EU regions. When combining all indicators, housing adequacy appears relatively highest in Scandinavian countries, parts of Central European, and a handful of other countries, while Eastern Europe and Portugal rank lowest. Notably, across the EU, the conditions of the surrounding environment and the quality of the dwelling itself often do not align, i.e., residents may live in a well-maintained dwelling in a poor environmental setting (France and the Netherlands) or vice versa (Bulgaria). Overall, these findings highlight the need for nuanced, country-specific housing policies that address both dwelling quality and environmental conditions simultaneously.

How is everything related?

To better understand the overall state of housing provision across the EU, we summarized the results and presented them in Figure 6. On the left side, we combined aggregated assessments of housing availability and affordability. This cross-country and cross-variable comparison helps identify patterns, reveal interconnections between housing domains, and highlight underlying structural causes. The resulting map shows that these housing domains interact differently across contexts. For example, Sweden, along with Germany, the Benelux countries, Italy, and much of Central and Eastern Europe, faces greater tensions in both availability and affordability, pointing to structural issues that demand stronger policy interventions beyond current measures. Meanwhile, Ireland, Finland, and Luxembourg exhibit better housing availability and affordability, suggesting their policies may be more effective and could serve as valuable examples to learn from. Notably, some countries show a mismatch between affordability and availability, as seen in Poland and Croatia, where housing is affordable but scarce, and Denmark, where availability is higher despite affordability issues. These findings highlight the complexity of housing market dynamics and the need for targeted policies to address imbalances, echoing the conclusions of other recent studies Kucharska-Stasiak et al., Reference Kucharska-Stasiak, Źróbek and Żelazowski2021; Hilber and Schöni, Reference Hilber and Schöni2022; Nasrabadi et al., Reference Nasrabadi, Larimian, Timmis and Yigitcanlar2024).

Figure 6. On the left: countries according to housing affordability and availability; on the right: countries according to combination of all measured indicators, 2010–2021 (authors’ elaboration based on OECD and Eurostat data).

On the right side of Figure 6, clusters derived from all measured housing indicators, including government contributions, are shown. A clear division between Western, Eastern, and Southern Europe is evident. Notably, these clusters also closely align with traditional welfare state regimes. Group 1, shown in blue, can be associated with the Mediterranean housing regime and is characterized by high homeownership rates, largely driven by family support and intergenerational transfers. These countries have moderate social housing stocks and limited government spending on housing, focusing more on homeownership incentives than on rental market development. The rental sector remains small and weakly regulated, creating affordability challenges. Meanwhile, Group 2, shown in red, can be associated with social-democratic and conservative-corporatist regimes. It features larger social housing stocks, well-developed rental markets, and strong tenant protections. While direct government spending is lower, policies emphasize market regulation, housing allowances, and indirect subsidies to support affordability. Lastly, Group 3, shown in yellow, comprises geographically more peripheral EU countries – post-socialist states together with Ireland and Portugal. These countries are characterized by low social housing stock, moderate government intervention, and an underdeveloped rental sector. In post-socialist states, rapid transition-era privatization boosted homeownership, while in Ireland and Portugal, gradual tenant purchase schemes and pro-ownership policies reduced public housing. Despite these different paths, all face persistent affordability and adequacy challenges.

Discussion and conclusions

Housing markets across the European Union face a complex set of challenges, encouraging the EU to strengthen its role in coordinating housing policies among member states. However, the effectiveness of these efforts remains debated, as diverse housing systems, national priorities, and regulatory frameworks make it difficult to apply uniform solutions (Dekker and Van Kempen, Reference Dekker and Van Kempen2004; Hilber and Schöni, Reference Hilber and Schöni2022; Nasrabadi et al., Reference Nasrabadi, Larimian, Timmis and Yigitcanlar2024). The EU presents an interesting case study in this regard, as it brings together countries with distinct historical backgrounds that have shaped their housing systems and policies. Despite these national differences, EU member states are also connected through shared regulations and overarching policy frameworks. Assessing and comparing different housing policies and systems across these countries is equally challenging, yet understanding this diversity is important. A broader perspective gained through international comparisons may offer insights into housing strategies, reveal common patterns, and guide the development of more effective policy solutions. The comparative approach is essential for identifying best practices, assessing policy transferability, and deepening the understanding of EU housing challenges. For instance, the financialization of housing – treating properties as investments rather than homes – exacerbates price pressures, reduces availability, and destabilizes markets across the EU (Çelik, Reference Çelik2024; Köppe and Byrne, Reference Köppe, Byrne, Greve, Moreira and Van Gerven2024). Similarly, while home-sharing platforms like Airbnb have driven up housing costs, particularly in city centres, recent regulations have had minimal impact on affordability (Reichle et al., Reference Reichle, Fidrmuc and Reck2023). Building on this perspective, this study aimed to provide an overview and comparison of housing provision across EU member states. It examined key domains – availability, affordability, and adequacy – while also exploring government efforts to enhance housing provision. The study explored how these issues differ between countries and how they correlate with each other and with the extent of government interventions, aiming to uncover the links between housing challenges and policy responses.

The findings of this study reveal significant variation in housing provision across EU countries when analyzed through the lens of availability, affordability, and adequacy. Each country faces distinct challenges: while some struggle with housing availability, others grapple with affordability or adequacy issues. Notably, when all housing indicators are combined to assess and compare overall housing provision, a clear geographical division emerges between Eastern and Western as well as Southern and Northern parts of Europe. Interestingly, these clusters largely align with welfare state regimes – merging social-democratic and conservative-corporatist types into coordinated market economies (CMEs) as per the Varieties of Capitalism framework (Hall and Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001), while assigning Mediterranean and Central and East European countries to mixed market or hybrid models (Hancké et al., Reference Hancké, Rhodes and Thatcher2007; Bohle and Greskovits, Reference Bohle and Greskovits2012), and cross-cutting traditional unitary/dualist housing regime typologies where the former aligns with unitary and the latter with dualist models (Kemeny, Reference Kemeny2001) – suggesting that housing provision is deeply influenced by path dependency (Bengtsson, Reference Bengtsson2001), as well as differences in economic development and political preferences (Ansell, Reference Ansell2014). Although many studies (e.g., Brown and Brik, Reference Brown and Brik2024; Flynn and Montalbano, Reference Flynn and Montalbano2024) argue that welfare models are limited in scope, our results show that these regimes – by highlighting the influence of broader structural factors – still play an important role in shaping housing provision patterns across the EU. Furthermore, there is no straightforward correlation between the overall state of housing provision and government intervention – a higher level of state involvement does not necessarily equate to better housing outcomes. These results emphasize that housing policies effective in one country may not yield the same results elsewhere, reinforcing the need for tailored, context-specific solutions (Coupe, Reference Coupe2021). Moreover, despite increasing EU involvement, the persistent pressure on housing markets suggests that policy coordination alone may not be sufficient to address the deep-rooted structural challenges, as economic, social, and regulatory differences across member states continue to shape housing provision. Therefore, more targeted, context-specific interventions are needed to effectively tackle these complex issues.

Although the results of this study provide important insights, they are subject to inherent limitations. For each domain, we intentionally construct three clusters – a methodological decision guided by the need to balance granularity and interpretability. Although alternative cluster counts could reveal additional nuances (for instance, four clusters might distinguish Central and Eastern Europe from Southern Europe more sharply), they would do so at the expense of clarity and comparability across the housing domains we analyse. Three clusters, therefore, provide the most coherent and interpretable structure for our analysis. Additionally, a major constraint is that broad generalizations primarily yield descriptive findings, limiting explanatory depth. Research incorporating different data types and focused case studies can offer deeper insights into specific aspects of housing provision and stronger analytical power; however, their narrower scope makes cross-country comparisons impossible. More granular territorial or individual-level data could further refine understanding of particular issues, while public opinion surveys could shed light on people’s perceptions of housing rights and policy effectiveness, helping to identify areas for improvement. Yet these approaches often sacrifice the broader perspective needed to capture and compare Europe’s complex housing landscape.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/ics.2025.10087.

Funding statement

This study has received funding from the Lithuanian Research Council (S-MIP-23-37 “Ensuring Housing Needs: Challenges and Prospects in Lithuania”).

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.