Introduction

Accessible and high-quality public services are vital to citizens’ well-being of citizens. As demands on public services increase, many governments are moving from a top-down approach to a more interactive model of service provision (Sundeen, Reference Sundeen1985; Voorberg et al., Reference Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers2014). Practitioners and academics endorse co-production, which refers to collaboration between public service agents and citizens, to enhance the quality and quantity of public services (Bovaird, Reference Bovaird2007; Osborne & Strokosch, Reference Osborne and Strokosch2013). While prior research has concentrated on developed regions, recent scholarship has shifted attention to developing countries with significant demand to fill public service shortages through co-production (Cepiku & Giordano, Reference Cepiku and Giordano2013).

Despite the advantages of co-production, public organizations and citizens may lack the motivation and capacity to cooperate. Public employees might doubt the value of citizen participation and be unwilling to treat citizens as partners in service delivery (Nederhand & Edelenbos, Reference Nederhand and Edelenbos2023; Yang, Reference Yang2005). Meanwhile, citizens may have cynical views of government initiatives and feel reluctant to give sincere input (Fledderus et al., Reference Fledderus, Brandsen and Honingh2015; Osborne et al., Reference Osborne, Radnor and Strokosch2016). Additionally, they lack the professional skills and knowledge needed to deliver public services and might be burdened by co-production (Thomsen et al., Reference Thomsen, Baekgaard and Jensen2020). These challenges are especially prominent in developing regions, which suffer from a shortage of resources and a lack of civic action.

An emerging group of studies has underscored the role of nonprofit organizations (nonprofits) in co-production (Cepiku & Giordano, Reference Cepiku and Giordano2013; Paarlberg & Gen, Reference Paarlberg and Gen2009). These studies investigate how the government engages nonprofits to deliver public services (Cheng, Reference Cheng2018). However, few have examined the possibility of nonprofits influencing and mediating the relationship between local officials and citizens to foster co-production. This study investigates if and how nonprofit organizations facilitate government–citizen co-production.

This study addresses these gaps using a case study in China. Given the dominant role of the Chinese state, most social organizations rely on the authority and resources of the government to engage in public affairs (Dong & Lu, Reference Dong and Lu2020; Hasmath & Hsu, Reference Hasmath and Hsu2015; Yu et al., Reference Yu, Shen and Li2021). Recently, governments have increasingly partnered with nonprofits in service contracts (Jing & Hu, Reference Jing and Hu2017). Many scholars perceive social organizations as government instruments that mobilize the masses and bolster their legitimacy (Kan & Ku, Reference Kan and Ku2021). There is a lack of research on whether such partnerships can change the interactions between government, nonprofits, and citizens to improve service delivery. Furthermore, most studies on China’s nonprofits concentrated on urban areas, there is insufficient research on how nonprofits are established and operated in rural societies (Zhang & Baum, Reference Zhang and Baum2004).

This study examines Z village in Beijing, which built one of the first rural social work institutes to provide professional social services. We asked two specific questions: What role do nonprofits play in rural service delivery? How do nonprofits activate co-production between rural officials and citizens? This study utilizes in-depth interviews, on-site observations, and secondary materials to answer these questions.

This study contributes to the literature by highlighting the roles and strategies of nonprofits in facilitating rural service delivery co-production. The findings suggest that in a state-dominant context like China, nonprofits can move beyond being an instrument of government and influence local officials to cooperate with citizens. While existing research on co-production has been primarily in the Western context, our findings highlight the challenges and corresponding solutions to enable co-production from a non-Western perspective (Cepiku & Giordano, Reference Cepiku and Giordano2013). Finally, our findings can inform policymakers on how the expertise and resources of nonprofits facilitate government-citizen cooperation and improve social service outcomes.

Public Services Co-production

The academics have not reached a consensus about the definition of co-production. In the early days, Ostrom and her colleagues explored the possibility for citizens to become active service providers. Later, Ostrom defined co-production as individuals from different organizations contributing resources to public goods and services (Reference Ostrom1999). In follow-up discussions, some scholars focus on voluntary participation by citizens and groups (Alford, Reference Alford2014; Verschuere et al., Reference Verschuere, Brandsen and Pestoff2012). For instance, Alford believes that co-production is an active action by someone outside the government cooperating with the government or an independent activity prompted by the government. Other scholars concentrate on the relationship between government and citizens. They stress that government and citizens should be equal partners who contribute resources to service provision for mutual benefits (Brudney, Reference Brudney2020). Most studies consider co-production to be the government’s and citizens’ collaboration to provide public services (Bovaird, Reference Bovaird2007; Voorberg et al., Reference Voorberg, Bekkers and Tummers2014).

Three types of factors influence government and citizen co-production: citizen characteristics, organizational attributes, and contextual factors (Sicilia et al., Reference Sicilia, Sancino, Nabatchi and Guarini2019). First, socioeconomic variables such as sex, race, income, and educational level can somewhat explain citizen behaviors (Van Eijk & Steen, Reference Van Eijk and Steen2015). Moreover, the motivation, issue salience, and self-efficacy affect citizen participation (Neumann & Schott, Reference Neumann and Schott2021). Second, scholars have found that public organizational values, internal arrangements, and professional roles are associated with the government’s adoption of service co-production (Farooqi, Reference Farooqi2016; Tuurnas, Reference Tuurnas2015). Third, contextual factors shape co-production, such as the country’s political and bureaucratic commitments and government initiatives (Jakobsen, Reference Jakobsen2013).

Compared with the government and citizens, the role of other organizations and stakeholders in co-production has been relatively overlooked. In the public administration literature, nonprofits are recognized as a prominent role in service provision, but their role and strategies in co-production have not received much attention. A group of studies has addressed this gap by examining how nonprofits have collaborated with the government to deliver public services (Cheng, Reference Cheng2018; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Yang and Deng2022; Pestoff, Reference Pestoff2018; Trætteberg et al., Reference Trætteberg, Lindén and Eimhjellen2023). For instance, Paarlberg and Gen (Reference Paarlberg and Gen2009) argued that unmet demand for public services and the supply of human and financial resources determine nonprofit involvement in education service delivery. Cheng (Reference Cheng2018) analyzed the contextual and organizational factors influencing nonprofit involvement in co-delivering public services. Some evidence suggests that nonprofit workers can better organize public participation and deliver targeted services (Verschuere et al., Reference Verschuere, Brandsen and Pestoff2012). Trætteberg et al. (Reference Trætteberg, Lindén and Eimhjellen2023) examined collaboration between third-sector organizations and government in local initiatives.

Nevertheless, most of those studies concentrate on the relationship between the government and nonprofits in co-production while neglecting the vital participation of end users. As mentioned, the public sector and citizens may lack willingness, capacity, and trust to co-produce services. The strategies that nonprofits use to overcome these challenges remain poorly understood. In other words, few studies probe the possibility of nonprofits mobilizing public sector officials and citizens to engage in collective decision-making and service delivery. Besides, while existing studies have revealed the determinants of nonprofits’ involvement, the process for nonprofits to initiate and accomplish service co-production requires clarification. Lastly, studies should factor in political, social, economic, and policy contexts influencing how nonprofits enable co-production. For instance, nonprofits in developing regions often struggle with significant resource scarcity and over-dependence on authorities (Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Chen and Cao2021).

Public Services in Rural China

Like many developing countries, China has huge economic and social disparities between rural and urban areas (Shan et al., Reference Shan, Geng, Fu, Yu, Pryce, Wang, Chen, Shan and Wei2021). The rural services suffer from sluggish development, inadequate resources, and insufficient professional manpower.

Traditional rural societies depended on their clans, kinships, and indigenous associations to provide social services collectively (Xu & Yao, Reference Xu and Yao2015). Yet, the mutual support system among villagers has weakened in a marketized and mobile societyFootnote 1 and has become inadequate to meet the growing expectations of villagers (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen and Araral2016). To address this gap, the Chinese government extended its welfare and service programs to rural areas beginning in the 2000s (Hong & Ngok, Reference Hong and Ngok2022).Footnote 2 It has devoted considerable resources to building rural infrastructure and enhancing education and healthcare services. Nevertheless, government financial support remains limited due to the large number of villages. Also, these services are generic and basic, not tailored to specific villages.

Villages are expected to develop public services according to residents’ needs. However, village officials often lack the willingness and capacity to improve rural services. Due to the outmigration of young and educated villagers, positions in VPCs and VCs are often assumed by older and less educated villagers. These village officials lack the professional skills and knowledge to supply the social services not required by the government (Shen & Zou, Reference Shen and Zou2015). Also, they are occupied by the formal responsibilities required by their superiors and rarely have the motive or energy to identify or meet the complex needs of the villagers.

There were two types nonprofits related to rural development and welfare. For one thing, villagers have established indigenous nonprofits to fulfill certain economic and social functions, but most are not specialized in providing social services.Footnote 3 For another thing, since the government reduced social restrictions in the 1980s, non-profit organizations developed and flourished in urban areas and engaged in various policy fields (Dong & Lu, Reference Dong and Lu2020). Some are devoted into alleviating poverty and enhancing rural community development. Although they are professionally trained to provide services, their bases in urban areas often limit their ability to serve the villages sustainably. Additionally, they may meet rural residents who doubt outside social organizations and have varying attitudes toward collaborating with them to manage rural affairs (Liu et al., 2018).

A third type of nonprofits, both indigenous and professional, are expanding in rural areas. Recently, the Chinese government has been cultivating professional nonprofits and volunteers in the countryside to support its rural revitalization strategy.Footnote 4 It plans to establish social work stations in all 38,000 towns to improve rural services.Footnote 5 Due to the lack of funding and personnel, the development of rural-based nonprofits remains nascent. Further studies are needed to examine how they are established and operated to improve rural service provision.

Methods

Research Design

Case Selection

This exploratory case study aims to reveal nonprofits’ strategies to facilitate co-production (Yin, Reference Yin2011). We selected Z village in Beijing as a case study.

Local governments in China have experimented with purchasing services from nonprofits to improve rural social services. Beijing has pioneered a scheme encouraging township governments to establish social workstations. Beijing’s peri-urban villages benefit from abundant human resources that specialize in social work. Suburban villages in Beijing are relatively well-off because they benefit from urban development and policy support from the Beijing government. Villagers who find employment in urban areas more open to new ideas and practices. This makes Beijing a prime location to experiment with recruiting social workers to improve rural services.

We selected Z village in Daxing district as an outstanding example because it established the first social work institute in rural China. Z village has 412 residents with an average annual income of 23,000 yuan. Han, the Z village party secretary, played a leading role in establishing the nonprofit organization to serve villagers. Han was a private entrepreneur and was elected as the village party secretary since 2012. Under his leadership, village organizations significantly improved their public infrastructure and basic social services. In 2016, to meet the increasing demands of villagers, he established a social organization called the YM Rural Social Work Institute (hereafter YM) and recruited professional and well-trained social workers to provide social services for the village.Footnote 6

The social work institute relies primarily on a service contract from the town’s government, which allocates 50,000 yuan annually, and VCs pay another 50,000 yuan to purchase services from the institute. Given its excellent performance in Z village, the institute gradually extended its services to seven villages nearby. By August 2022, the institute hired 12 social workers and several interns. They also bid for projects funded by social enterprises and charitable foundations, although they were shorter with less stable funding.

As the leader of YM, Han respects the social work profession and delegates ample discretion to social workers to design and deliver services and activities. However, due to its dependence on township and village resources, YM incorporates its preferences and requirements into its working plans and daily activities, which can undermine its autonomy. Specifically, YM needs to align their services and activities with the priorities of township government, helping the later to manifest performance in the official evaluation system. Also, when YM extended services to other villages, village officials were slow to accept social work, paying inadequate respect to the autonomy and profession of social workers. Moreover, village officials would shirk some responsibilities to social workers as they believe they have paid for their services. Furthermore, conflicting priorities and interests from township and village officials add a coordination burden to social workers. Like many other nonprofits in China, YM needs to maneuver multiple groups of stakeholders while maintaining their profession and efficacy in social work.

Data Collection and Analysis

The data sources included on-site observations, semi-structured interviews, and secondary materials. We visited the village in July and November 2022 for on-site observations and interviews. We organized online interviews with relevant actors in April, September, and October of that year. We also collected secondary documentation from open sources, such as the summary reports of the social work institute, newspaper reports, and published journal articles about Z village and YM.

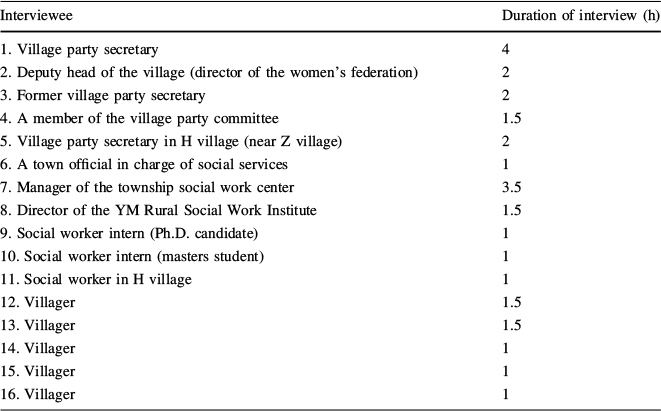

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with six village and town officials, four social workers, and five villagers (see Table 1). Specifically, we asked the Z village party secretary about his motivation for establishing YM and his strategy of engaging social workers to provide services. Furthermore, we asked other village officials how they interacted with the social workers and villagers to address problems. To increase the richness of the data, we conducted several interviews with the village party secretary and social workers from H village near Z village. We also interviewed social workers about their strategies for providing services in the community and their relationships with village officials and ordinary villagers. The social workers frequently shared information about their working methods in other villages. Finally, we interviewed villagers about their experiences, perceptions, and assessments of community services. Moreover, we triangulated and cross-checked data from interviews, documents, and observations (Table 2).

Table 1 List of interviewees

Interviewee |

Duration of interview (h) |

|---|---|

1. Village party secretary |

4 |

2. Deputy head of the village (director of the women’s federation) |

2 |

3. Former village party secretary |

2 |

4. A member of the village party committee |

1.5 |

5. Village party secretary in H village (near Z village) |

2 |

6. A town official in charge of social services |

1 |

7. Manager of the township social work center |

3.5 |

8. Director of the YM Rural Social Work Institute |

1.5 |

9. Social worker intern (Ph.D. candidate) |

1 |

10. Social worker intern (masters student) |

1 |

11. Social worker in H village |

1 |

12. Villager |

1.5 |

13. Villager |

1.5 |

14. Villager |

1 |

15. Villager |

1 |

16. Villager |

1 |

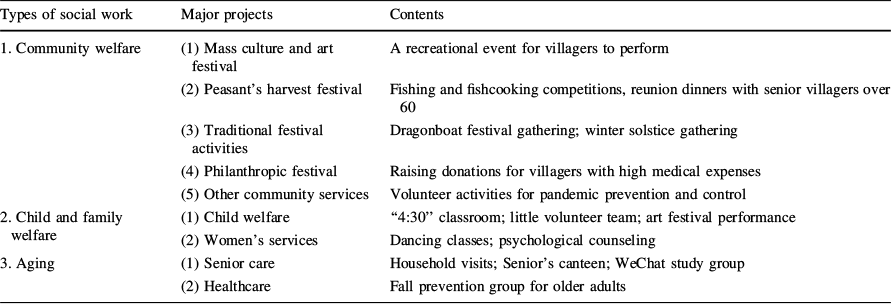

Table 2 Major projects in Z village

Types of social work |

Major projects |

Contents |

|---|---|---|

1. Community welfare |

(1) Mass culture and art festival |

A recreational event for villagers to perform |

(2) Peasant’s harvest festival |

Fishing and fishcooking competitions, reunion dinners with senior villagers over 60 |

|

(3) Traditional festival activities |

Dragonboat festival gathering; winter solstice gathering |

|

(4) Philanthropic festival |

Raising donations for villagers with high medical expenses |

|

(5) Other community services |

Volunteer activities for pandemic prevention and control |

|

2. Child and family welfare |

(1) Child welfare |

“4:30” classroom; little volunteer team; art festival performance |

(2) Women’s services |

Dancing classes; psychological counseling |

|

3. Aging |

(1) Senior care |

Household visits; Senior’s canteen; WeChat study group |

(2) Healthcare |

Fall prevention group for older adults |

We combined multiple sources of data to identify the strategies adopted by social workers without imposing assumptions. Two researchers manually coded the texts independently to avoid bias. Divergent opinions were discussed until a consensus was reached. We used open coding to analyze interviewees’ accounts and identify how social workers enabled service co-production. We then used axial coding to categorize the open codes into specific axes. We identified four strategies adopted by social workers: establishing trustworthy relationships, facilitating effective communication, fostering shared motivations, and building co-productive capacity.

Results

The YM Social Work Institute sends one social worker to serve and assist a village (consisting of hundreds to thousands of villagers) to provide social services. Given their limited manpower and resources, social workers must motivate village officials and villagers to co-produce social services. The rationale of social work is “helping people to help themselves,” that is, cultivating the self-help awareness and capacity of villagers to meet their own needs. We found that social workers adopted four strategies to enable co-production in Z village. These strategies transform village officials and rural residents into proactive providers of welfare and services for their communities.

Establishing Trustworthy Relationships

Mutual trust is a critical precondition for co-production between the government, citizens, and nonprofits (Kang & Van Ryzin, Reference Kang and Van Ryzin2019; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Lin, He and Zhang2023; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Xiao and Yang2021). The government’s distrust of non-governmental actors and citizens and anxiety about losing leadership discouraged authentic partnerships with them. Citizens may not have sufficient information about nonprofits and may be suspicious about the value of participating in co-production (Liu, Reference Liu2022). When nonprofits cooperate with the government to deliver public services to their citizens (Jing & Hu, Reference Jing and Hu2017), they build a reputation for being responsible, thus winning government trust. Mutual trust between nonprofits and citizens can be enhanced when nonprofits use local preferences to provide services. Moreover, nonprofits have gradually incorporated local players to understand and engage in professional social work, preparing them to become service providers.

Social workers are exogenous players and must integrate into village networks and gain the trust of village officials and residents. First, social workers should seek agreement and support from village officials who hold the dominant authority in the village. In Z village, they invited village officials to plan social work activities. As one social worker stated:

Initially, we approached the village party secretary with a brief report of our project. We introduced the policy background and asked for his opinions. Based on the information, we drafted a plan and discussed it with him to reach a consensus about how to carry out social work.

Social workers also encouraged village officials to participate in professional social work so that village officials could understand the professionalism required. For instance, social workers invited village officials to join them in household visits, providing services, organizing voluntary work, etc. The village party secretary recalled that he was impressed by how the social workers conducted their work with great patience and excellent commination skills. Such cooperation deepened mutual understanding and emotional bonds between village officials and social workers. The deputy village leader in Z village said that she treated social workers as her children and enjoyed participating in activities organized by them.

Social workers also assisted village officials in their formal duties to gain trust, for example, providing support at the weekly meetings, assisting with pandemic control, filling in e-government forms, etc. Their assistance is crucial in villages where officials are too old to accomplish these tasks. This echoes a Norwegian study where social organizations partnered with the public sector in co-production (Trætteberg et al., Reference Trætteberg, Lindén and Eimhjellen2023). However, while social workers believed that their engagement in rural affairs made them closer to officials, they complained that some village officials treated them as subordinates and assigned them excessive and irrelevant tasks.Footnote 7

Social workers established trust relationships with villagers through routine service delivery. In China, villages are communities where residents traditionally engaged in reciprocal activities based on lineage and social relations. Social workers lived and worked with rural residents, which gave them deep knowledge and strong connections with the community, allowing them to investigate and solve fundamental needs. As one social work intern stated,

Unlike counterparts in urban areas, social workers in rural areas need to eat, live, and work with villagers. Social workers should gain a deep understanding of villagers’ daily lives and routines to serve the community.

Social workers explained, by settling into villages, they could identify fundamental problems in the community. In contrast, if they perceive themselves as “visitors,” they could only touch the surface of the problem.

Moreover, social workers developed personal relationships with villagers. They found that villagers saw them less as service providers and more as friends who brought them comfort. As one social worker said,

I think villagers consider me to be a close friend before acknowledging me as a professional social worker. We should get acquainted with them before we provide services. It is important to bring people together for whatever purpose. Villagers already share relatively strong emotional connections. What they need is not professional mental consultations but chatting to relieve their stress.

Due to their close relationships, villagers tend to trust social workers more than they trust village officials. The village party secretary offered an example,

During the pandemic period, there was a rumor in our neighborhood that vaccines killed people, making older adults concerned for their safety. Our social workers patiently explained how vaccines worked to relieve their anxiety. Our village accomplished the highest vaccination coverage.

Furthermore, social workers invited senior villagers to share stories of village events to generate deeper links with villagers. They combined social service activities with indigenous resources and traditional events to attract public participation and reinforce collective identity. For example, they used the collectively owned pool to hold a fishing and cooking competition and delivered the finished soup to older adults during the Mid-Autumn Festival.

Facilitating Effective Communications

Communication is vital for facilitating co-production. Information asymmetry between multiple stakeholders is a serious obstacle to co-production (Li, Reference Li2019). As a third party, nonprofits can become intermediaries in government-citizen interactions (Li, Reference Li2020). Nonprofits can exploit their neutral role to pass information between the government and citizens. They can use communicative expertise to collect information and feedback from citizens. Furthermore, they can inform the government about how to devise suitable co-production arrangements and tell citizens about how to become partners in service delivery.

When government, town, and village officials dominated the service delivery process, there was a lack of communication between village officials and villagers regarding what public services were needed and how to provide them. To facilitate communication, social workers conducted a door-to-door survey to understand how villagers perceived community needs. Social workers found that villagers were more likely to share their opinions with them than village officials. One social worker said, “villagers have many concerns with expressing their opinions to village officials because of the complex interpersonal relations.” The survey successfully identified the unmet community needs. For instance, social workers realized that over half the villagers were retired, so they wished to enjoy recreational activities and interact more with other villagers to relieve loneliness.

Afterward, social workers provided the information to village officials and advised them to hold public meetings to communicate directly with the villagers. Social workers presented 20 suggestions collected from the survey at the meeting and asked the villagers to express their opinions and raise questions. Village officials explained how they planned to meet certain demands and why they could not satisfy others. Later, village officials, social workers, and villagers agreed on what services were needed and how to provide them.

Through these activities, village officials realized the value of listening to villagers to identify and provide targeted services. A village official commented:

The arrival of the social workers changed my perspective significantly. In the past, we only knew to provide services without consulting residents. We learned to look at the community from the standpoint of villagers and provide villager-oriented services.

Moreover, social workers mediated misunderstandings between village officials and citizens. One of the social workers shared how they helped resolve the conflict about the distribution of vegetables.

Communication is more effective if we mediate between village officials and villagers. On the one hand, we patiently explained to villagers how we distributed vegetables without discriminating against anyone to dispel their misunderstanding. On the other hand, we helped village officials realize that some of their conduct was inappropriate in villagers’ eyes.

Effective communication laid the foundation for co-production. Because village officials and social workers had more information about the villagers’ preferences, they could design services and activities that interested villagers and attracted public participation.

Fostering Shared Motivation

Shared motivation, defined as common interests, goals, and values, is indispensable for co-production (Neumann & Schott, Reference Neumann and Schott2021; O’Brien et al., Reference O’Brien, Offenhuber, Baldwin-Philippi, Sands and Gordon2016). Co-production relies on the government and citizens to develop a shared understanding of the values and means to accomplish it (Ansell & Gash, Reference Ansell and Gash2008; Fledderus & Honingh, Reference Fledderus and Honingh2016). Social workers can proactively transmit the core values of co-production through their words and deeds. In Z village, we found that with increased interaction, village officials and villagers gradually assimilated the values of service, respect, compassion, and reciprocity, reinforcing partnerships in service provision.

The village party secretary stated that their cooperation with the social workers changed their mindset from commanding to serving people. He proposed a metaphor that village officials are “waiters and waitresses,” and villagers are “clients.” He required other village officials to learn from social workers and prioritize respect.

We found that the social workers were very modest and expressed considerable patience and respect for villagers. Therefore, their activities have a fundamental impact on recipients.

A village official said that he used to only follow the policy mandates from the government. Still, now he prefers the approach practiced by social workers to prioritize the needs of residents. Another official shared how the compassionate spirit of social workers influenced her through cooperation with older adult care services.

Older people usually lived in messy and dirty environments; they did not take showers. Most people cannot stand that. However, social workers never avoid their dirtiness. I admire their compassion for older adults. This transformed me a lot. I can feel that staying with older adults, even just talking to them makes me feel very happy.

Social workers also noticed their influence on the village officials. The manager of YM stated:

I understand that there is tension between village officials and villagers in many villages. Village officials perceive themselves as leaders, and villagers also feel separate from them. Yet, when village officials take us to the households and see how we interact with villagers, village officials learn from our attitude and become more patient with villagers.

Furthermore, influenced by village officials and social workers, villagers have become more committed to public interests and actively participate in voluntary activities. A villager commented that as the leaders put greater effort into serving the villagers, the villagers became more concerned with public affairs. They felt proud of being members of Z village when they compared their community services with those in neighboring villages. A villager provided an example:

One day, the volunteer’s vegetable garden required labor to harvest potatoes. Village officials and social workers notified villagers on the WeChat group at night. The next morning, villagers got up very early to harvest the potatoes. People from other villages were surprised we were willing to do such a tiring job. They required us to arrive at 6 am, but some people arrived at 5 am. At 7 am, they finished and distributed the potatoes to the villagers. That is very fast! Indeed, we have a great leader who makes people united.

Both village officials and villagers realized that building a cohesive and comfortable community requires collective action.

Building Co-productive Capacity

Limited co-production capacity is a fundamental problem, especially in developing countries (Schuttenberg & Guth, Reference Schuttenberg and Guth2015; Tuurnas, Reference Tuurnas2015). Nonprofits can facilitate co-production by building co-productive capacity among public officials and citizens. They can share knowledge and experience with government officials on soliciting citizen opinion, organizing participation, and incorporating citizen assessments into service provision (Jing & Hu, Reference Jing and Hu2017). Also, nonprofits can empower citizens by disseminating relevant information, imparting skills, and organizing training sessions on co-production.

The Z village party secretary realized he needed systematic social work education to lead the social work institute. He invited social work professors as council members of the institute to offer professional guidance and advice. Also, he attended social work courses and conferences to learn about the principles, values, and methods of social work. Other village officials gained more knowledge and capacity for social work while observing and partnering with social workers to provide services. A few officials attempted to acquire certification by taking China’s social work professional-level examination.

Social workers noted that although some villagers have a spirit of volunteerism, they lack the opportunity and capacity to organize themselves to help others. To enhance the co-productive skills of villagers, social workers organized volunteer teams and cultivated professional volunteers among rural residents in 2018. As one social worker remarked:

We held a ceremony to establish the volunteer team. All the volunteers came up with the name of our team and designed the team logo. Through these activities, they learned that this team is a professional organization. Occasionally, we hire professional trainers to hold training sessions for team members.

Village officials also served as examples to the volunteer team by providing voluntary services. They also mobilized other party members to become the first group of volunteers. Their exemplary roles reduced villagers’ doubts about joining the volunteer group. From 2018 to 2021, volunteer team members increased from six to over 20. With the team’s establishment, rural residents became more engaged in rural activities.

Impacts on Public Service

This section illustrates how social workers’ strategies have gradually changed the relationship between village officials and villagers and enhanced their capacity to co-produce community services. YM designed three types of social work to meet villagers’ basic and specialized needs. The community welfare programs aimed to improve community members’ health and mental well-being. For instance, social workers organized the volunteer’s vegetable garden and led villagers to grow vegetables. Besides, social workers designed special programs for children, women, and seniors, who comprise the majority of rural residents.

In the early stages, social workers initiated, designed, and executed services and invited village officials and villagers to participate. Through a household survey, social workers realized that many villagers wished to participate in charity projects. They suggested that the village party secretary hold a philanthropic festival to raise money for households with excessive medical care expenses. In the first year, approximately 200 people participated in the activity, and those who missed the activity even came to the village committee to donate afterward. The funds raised rose from 4,613,644 yuan to 6,13,446 yuan in the first three years. The funds helped 15, 11, and 18 people from 2016 to 2018 respectively.

As a village official admitted, they had little experience designing collective activities. After engaging in several collaborative projects with social workers, they accumulated experience organizing collective activities. The development of mass culture and an art festival is a notable example. Initially, social workers designed the festival as a singing competition among villagers. One year later, village officials joined in planning the activity and diversified the performance by including comedy shows and cross-talk. At the 2022 harvest festival, village officials proposed inviting professional musicians and musical actors to train villagers for their performances. The villagers and village officials performed a musical about their villages’ development and transformation. Social workers stated that they gradually shifted from being initiators and organizers to participating and facilitating social services.

Volunteers have played a proactive role in designing and implementing community services. For instance, because social workers had limited information about villagers’ preferences, the volunteers offered key information to tailor services according to villagers’ needs. A social worker said,

At the Dragonboat Festival, we made rice dumplings with volunteers. Social workers were inexperienced in making rice dumplings. At the initial meetings, we asked the aunts how to prepare ingredients and utensils according to the number of people. The aunts offered valuable advice. The same thing happened for the dumpling dinner at the winter solstice. They told us the number of older people, how much flour and fillings to prepare, and what should be avoided.

Social workers invited village officials and villagers to co-assess community services. Social workers asked all involved parties to participate in a summary meeting. They discussed themes like the performance of different stakeholders and problems. Some members proposed what they wished to do for their next activity. For instance, in an assessment meeting, a few older women stated that arts and crafts were not practical; instead, they wanted to learn skills such as cooking and planting to enrich their lives.

Volunteering changed how villagers perceived and engaged in community affairs. The interviewees expressed their pride in being a community member. They said village leaders and social workers united everyone in collective activities, reinforcing their sense of belonging. Therefore, villagers were more willing to participate in voluntary activities serving community interests. A town official maintained that service co-production contributes to social stability:

In H village, there used to be a veteran who often called the hotline 12345 to complain about his problems. Later, the deputy village leader mobilized him to join the volunteer team and contribute to village life. The veteran said that he would not make complaint calls anymore. The role of a volunteer might have improved his awareness and ability to serve the public. (Interview T1)

Discussion and Conclusion

This study examined how social organizations activate co-production in rural service provision in a peri-urban village in Beijing, China. It illustrates four strategies social workers use to engage village officials and citizens in co-producing social services. First, social workers established trustworthy relationships with village officials and villagers, a precondition for co-production. Next, they used enhanced communication to identify services for co-production and cultivated shared motivation regarding the value of co-production. Besides, they transmitted the values regarding co-production through their words and deeds in service provision. Finally, they used their expertise to build the stakeholders’ capacity to co-produce services. The co-production approach to service provision has improved the quality of services and contributed to social stability based on reciprocity and trust between village officials and villagers.

This study highlights the proactive role of nonprofits in co-production. Although some studies have acknowledged social organizations’ unique resources and expertise in co-production, they have not sufficiently examined how social organizations can transform the interaction between public organizations and citizens in service provision (Cheng, Reference Cheng2018). Our findings reveal the approaches nonprofits use to influence public officials’ and citizens’ values, motives, and capacity, thereby increasing their willingness to co-produce public services.

Nonprofits have several unique advantages in facilitating co-production between the government and citizens. They can act as intermediaries to reduce the information asymmetry between public officials and citizens (Li, Reference Li2020). In Z village, the interests of village officials and residents are interwoven and complicated, requiring a non-interested player to tackle sensitive issues, deliver information, and forge consensus. Nonprofits can cultivate volunteers and plan, design, and assess collective actions. Public officials and citizens can learn these skills to realize service co-production.

Second, while most prior studies concentrate on co-production in developed countries, this study points to an emerging trend of co-production in an underdeveloped rural context (Cepiku & Giordano, Reference Cepiku and Giordano2013). The findings suggest that rural societies require social workers to tailor their skills and approaches to local needs. In many traditional societies, informal institutions shape how residents articulate their interests and organize collective actions (Xu & Yao, Reference Xu and Yao2015). Nonprofits can use social ties and networks to improve their credibility (Casey, Reference Casey2016). Besides, because many village residents hold a collective memory of their village, social workers can acquire local knowledge and utilize indigenous resources to mobilize rural residents into cooperation. These findings imply that social workers need to enrich their knowledge system with indigenous culture and traditions to conduct meaningful work in rural societies.

Third, the political and administrative system shaped nonprofits’ development and operation, which fundamentally impacts their ability to facilitate co-production. Our findings indicate the government’s strategy to improve rural service provision, accompanied by policy support and specific funding, has stimulated the growth of specialized and professional nonprofits in rural China. Nonprofits do not always avoid governments; they collaborate to obtain more resources. As YM shows, nonprofits’ close relationship with authority has endowed them with official recognition and available funding, with which they can exercise their expertise to conduct social work in villages. The semi-official background has helped nonprofits to enable co-production in service provision.

Although government support has helped the smooth development of nonprofits, power asymmetry between the government and nonprofits may influence their long-term development and ability to initiate co-production. As the case of YM shows, receiving government and village funding brought more obligations and pressure to undermine their profession and autonomy, which might erode their ability to influence officials and citizens in the future (Kang & Ku, Reference Kan and Ku2023). Hence, maintaining their profession and autonomy while building good relationships with the government is a major challenge for nonprofits.

Lastly, our findings have crucial implications for policy practitioners to improve service outcomes and bolster public trust. The government should contract services to nonprofits and gradually build mutual trust (Jing & Hu, Reference Jing and Hu2017). Moreover, it should give nonprofits some level of autonomy to design services and mobilize citizens, making them professional partners rather than government instruments. Finally, the government should assimilate the expertise and skills of members of nonprofits and learn how to cooperate with them and the local citizens to provide services.

Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. First, the study mainly draws information from Z village and its proximate villages; therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to other regions of China. Nevertheless, the case of Z village might be an example for other villages in terms of incorporating social workers into rural governance. Additionally, in Z village, service delivery co-production is still early. Our findings suggest that co-production can improve social services, enhance public trust in public agencies (Fledderus et al., Reference Fledderus, Brandsen and Honingh2014; Kang & Van Ryzin, Reference Kang and Van Ryzin2019) and help the government improve public accountability (Tuurnas et al., Reference Tuurnas, Stenvall and Rannisto2015). Future researchers should track the progress of the Z village project to measure the long-term impact of co-production. Furthermore, future studies can adopt a comparative approach to examine how political, social, and economic contexts affect conditions and strategies for government, local citizens, and nonprofits to participate in service delivery co-production (Cheng, Reference Cheng2020). Researchers can use quantitative methods to test the finding’s generalizability.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China, Grant Number 22AZD050, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant Number 71721002, and the Tsinghua University Initiative Scientific Research Program, Grant Number 2021TSG0820, and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, Grant Number 2023M731903. This research was also supported by “Shuimu Tsinghua Scholar” Program in Tsinghua University, China.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

To the authors’ best knowledge there are no conflict of interests.

Ethical Approval

The research was approved by the ethics committee of the School of Public Policy and Management at Tsinghua University.

Informed Consent

It involved human participants and the authors have obtained informed consent of all participants.