Introduction

Many major challenges facing modern societies – ranging from the prevention of global warming and the sustainability of public finances to the integration of immigrants and the skills upgrading of the labour force – share a common temporal structure. Addressing them requires political actions, such as public investments in physical or human capital, that incur large costs in the present but for which the societal gains may not be immediately visible and may accrue over several years or longer. A growing body of work in public economics, climate politics and welfare state research seeks to better understand how these challenges can be addressed, by investigating various political and institutional factors that may facilitate or impede long term‐oriented governance and policy (e.g., Bernauer, Reference Bernauer2013; Boston, Reference Boston2017; González‐Ricoy & Gosseries, Reference Ricoy and Gosseries2016; Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2016, Reference Jacobs2011; Jacques, Reference Jacques2021; Lindvall, Reference Lindvall2017; Morel et al., Reference Morel, Palier and Palme2011).

In these literatures, factors linked to the ‘human condition’ of voters – including informational poverty and cognitive biases such as time‐inconsistent preferences – figure prominently as an underlying explanation of myopic policy‐making, by providing electoral incentives for politicians to behave opportunistically in favour of the short term at the expense of the long term (Boston, Reference Boston2017; Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2016; Rogoff, Reference Rogoff1990). Whereas some efforts have been put into assessing these human conditions – such as to what extent voters are myopic (Healy et al., Reference Healy, Persson and Snowberg2017) or impatient (Jacobs & Matthews, Reference Jacobs and Matthews2012) – so far little attention has been devoted to how they are perceived by politicians. Notwithstanding, some first‐hand descriptions of presentist bias in policy‐making – by former politicians themselves (Cullen, Reference Cullen2014) and in interviews (Boston, Reference Boston2017) – the assumptions about politicians' perceptions and preferences that underpin the existing literature on inter‐temporal policy‐making thus remain largely unverified. Furthermore, the relative importance of different impediments to long‐term governance has not yet been assessed.

To begin filling these gaps, this study turns to the politicians themselves to assess a number of key assumptions about how voters' biases incentivize incumbent government politicians to trade off the long‐term against the short‐term opportunistically when facing competitive elections or liquidity constraints. These assumptions are assessed in a context where they should be unlikely to hold – among local governments in Sweden – and their perceived importance is subsequently compared to a number of other factors hypothesized to impede long‐term governance.

Our analyses are primarily based on a survey, distributed to the universe of councillors in local governments in Sweden, involving new survey experiments about environmental‐friendly public investments combined with direct questions. Our results can be summarized in five points: First, we find that a small minority of local governing coalition politicians appear prepared to act opportunistically to improve their re‐election prospects when facing a competitive election. Second, such opportunistic behaviour is, however, generally expected to stimulate rather than to impede investments. Third, public investments are, however, less likely to be supported if their costs cannot be financed in the form of gains foregone instead of absolute losses – a finding which demonstrates the relevance of endowment effects in future‐oriented policy‐making. Fourth, these micro‐level results are also reflected in macro‐level policy outcomes, in the sense that local governments' investment expenditures are larger in years when they face high electoral competitiveness and in years that were preceded by a budgetary surplus that allows for financing in the form of gains foregone rather than absolute losses.

Our findings have important implications for research on democracy and future‐oriented policy‐making. First, they challenge the widespread assumption that electoral competition inherently triggers policy myopia, and they instead point towards the relevance of other, less investigated, factors. More generally, they demonstrate that to improve our understanding of long‐term–oriented policy decisions, it is important to both account for politicians' own perceptions about the trade‐offs involved in such decisions and investigate the link between these micro‐level perceptions and the macro‐level policy outcomes.

Voters' biases and myopic policy‐making

Among scholars of long‐term governance, democratic policy‐making is commonly thought of as suffering from an inherent myopic – or ‘presentist' – bias (e.g., Aidt et al., Reference Aidt, Veiga and Veiga2011; Bernauer, Reference Bernauer2013; Boston, Reference Boston2017; Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Liu and Mulas‐Granados2016; Gailmard & Patty, Reference Gailmard and Patty2019; Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2016; Jacques, Reference Jacques2021), which results in policy that prioritizes improved social welfare in the present, over investments that would maximize gains in the long‐term yet would require up‐front costs and have more a delayed benefit stream.

Previous research has pointed to several factors that may help explain such bias. While these factors have been interpreted and categorized in somewhat different ways by different scholars, they are generally seen as deriving from three distinct underlying causes: (1) informational and cognitive biases among voters – what Boston (Reference Boston2017) refers to as their ‘human condition' – that incentivize politicians to prioritize short‐term gains for opportunistic reasons, (2) political uncertainty regarding the realization of the potential future benefits and (3) opposition of organized interests – not least industries – that bear the short‐term costs of future‐oriented policies (Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2016).

We focus the theoretical and evaluative parts of this study on the first category of explanations, but for comparative purposes we briefly return to the latter two in the empirical analysis. In the discussion that follows, we distinguish between two aspects of the human condition of voters that may help explain present‐oriented policy‐making in two different contexts, depending on the electoral competition facing the government and on the financing options that it has at hand when considering a public investment.

Presentist bias linked to electoral competition

A long‐standing literature concerned with future‐oriented policy‐making, or long‐term governance, takes as its point of departure various types of biases among voters – such as time‐inconsistent consumption preferences (Strotz, Reference Strotz1955), a desire to exploit future generations (Bowen et al., Reference Bowen, Davis and Kopf1960), lack of information about long‐term policy outcomes (Rogoff & Sibert, Reference Rogoff and Sibert1988; Rogoff, Reference Rogoff1990) and a tendency to economize on cognitive effort when deciding on whom to cast their votes in an election (Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2011). These biases are understood as providing incentives for incumbent governments to prioritize policies with more immediate payoff structures when seeking to please voters – and they are often seen as particularly problematic when elections are competitive – i.e., when their outcome is uncertain – because this is when the governments have most to gain from imposing myopic policy opportunistically to improve their re‐election prospects (Cronert & Nyman, Reference Cronert and Nyman2022; Schultz, Reference Schultz1995).

In an influential study, Rogoff (Reference Rogoff1990) proposed a model where public investments only become productive and visible after the next election. Because governments seek re‐election and because it can be electorally costly for them to reduce current expenditure (e.g., Bojar et al., Reference Bojar, Bremer, Kriesi and Wang2022; Jacques & Haffert, Reference Jacques and Haffert2021), fiscal policy will be biased away from public investment and towards easily observable current expenditures if the outcome of the election is uncertain (Rogoff, Reference Rogoff1990). In line with this model, Aidt et al. (Reference Aidt, Veiga and Veiga2011), for instance, find that in Portuguese municipalities, investments are reduced in favour of more visible expenditures when an uncertain election is expected.

Yet, for a number of reasons it is not evident that such opportunistic incentives will trigger lower investment levels when a competitive election is approaching. First, Rogoff's model assumes that public investments generate benefit streams that are visible to voters only after the next election. But this is not the case for all types of investments; in fact, for those that involve the creation of local physical capital – such as bridges or parks – some indication of future benefit streams becomes visible as soon as the ground is broken (Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2016; Veiga & Veiga, Reference Veiga and Veiga2007). Moreover, if such public investment projects are labour‐intensive, they are likely to involve the expansion of local employment opportunities that may be highly valued by voters. A different argument, which does not hinge on assumptions about visibility, holds that when re‐election is unlikely, an incumbent can control the policy of their adversary successor by making long‐term investments in infrastructure or sustainable energy (e.g., Aklin & Urpelainen, Reference Aklin and Urpelainen2013; Glazer, Reference Glazer1989).Footnote 1

Both these arguments imply that governments may want to increase rather than decrease investments when they are not certain about being re‐elected into office. Doing so might be an especially attractive option in a context where fiscal policy operates under a so‐called ‘golden rule’, which states that while current expenditures should not exceed current revenues (and thus are difficult to use for opportunistic purposes), investments can be financed by issuing debt. A golden rule of this kind has for long applied to the Swedish municipalities in focus here – although the share of self‐financing remains high – and such rules have also occurred on the national level in Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom and some other countries at various points in recent decades (Lledó et al., Reference Lledó, Yoon, Fang, Mbaye and Kim2017).

It is worth noting here that the potential incentives for governments to make short‐sighted policy decisions in response to high electoral competition may arise not only from voters’ biases but also from their differing opinions. Since voters, and consequently the competing political parties, in many cases have conflicting preferences regarding the allocation of public funds, a government that anticipates a higher risk of losing office may be more motivated to allocate resources towards its favoured policies while issuing debt that will be repaid by the adversarial successor. This strategy effectively limits the flexibility of the next government (Alesina & Tabellini, Reference Alesina and Tabellini1990).Footnote 2 Therefore, to avoid conflating such ideologically motivated behaviour with behaviour triggered by voter's informational and cognitive biases, analyses like ours, that focus on the latter, will be helped by concentrating on policies that engender relatively low levels of ideological conflict.

Presentist bias linked to the conditions of financing

Now, even in contexts where public investments can be debt‐financed, a part of their costs typically needs to be paid by current expenditures or equity. This circumstance makes it relevant to consider another type of cognitive bias associated with the human condition of voters, namely the widely documented tendency for people to be less willing to incur a loss than to forego an equivalent gain – usually referred to as the endowment effect (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1984; Thaler, Reference Thaler1980).

This tendency is likely to matter for future‐oriented policy‐making, by making investments easier for governments to prioritize in contexts where they can be financed by imposing opportunity costs – for instance, by taking funds out of current surpluses – instead of actual costs in the form of tax increases or spending cuts made elsewhere (Boston, Reference Boston2017; Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2016). In such cases, the cost would come in the form of some other gain foregone, rather than as an absolute loss that would be more palpable and salient to the voters.

The endowment effect has been labelled ‘one of the most robust findings in the psychology of decision making’ (Knetsch et al., Reference Knetsch, Tang and Thaler2001, p. 257), but there is still a shortage of evidence outside of the laboratory (Ericson & Fuster, Reference Ericson and Fuster2014). Political scientists have acknowledged that voters’ aversion to losses may inhibit welfare state reform (Pierson, Reference Pierson1996) and may explain why the marginal effect of changes in income or unemployment on incumbents' voter support differs between economic downturns and upturns (e.g., Bloom & Price, Reference Bloom and Price1975; Kappe, Reference Kappe2018) as well as why long‐term investments are less resilient than cash transfers to cutbacks during episodes of fiscal consolidation (Jacques, Reference Jacques2021). Yet, we are aware of no study that experimentally evaluates the role of endowment effects for future‐oriented policy‐making.

Three verifiable assumptions

In concluding this section, we delineate three distinct and testable assumptions about the perceptions of politicians that underpin theories about long‐term governance in democratic policy‐making:

-

1. Politicians believe that engaging in present‐oriented policy‐making may improve their re‐election prospects.

-

2. Politicians are prepared to engage in such policy‐making when anticipating a competitive election.

-

3. Politicians are more willing to make an investment if they can finance it by foregoing an equivalent gain instead of imposing an absolute loss.

Case selection and data

We seek to assess the three assumptions listed above by studying Swedish local politicians using an online survey. Our motivation for this choice of case is partly practical and partly strategical. Practical in the sense that – reflecting Sweden's top ranking in terms of open government (WJP, 2015) – it is likely one of few countries where the e‐mail addresses to almost all local politicians could be easily and affordably collected. Sweden is furthermore known from cross‐national surveys of local politicians to be among the countries where these are most likely to participate in such studies (Bäck et al., Reference Bäck, Magnier, Heinelt, Bäck, Heinelt and Magnier2009). From a strategical perspective, the 290 Swedish local governments allow for observing a very large number of politicians who have large discretion over policy yet operate in a common institutional context. Analogous to the most similar systems design, this should provide for ample variation in both competitiveness and policy, while keeping institutional and socio‐cultural confounders to a minimum. Furthermore, considering Sweden's consensus‐oriented political, cultural and institutional context (Lewin, Reference Lewin1998), we expect Sweden to be a fairly representative case of an advanced economy with parliamentary democracy when it comes to future‐oriented policy‐making.

With regard to electoral institutions, Swedish municipalities are fairly similar to many other proportional representation (PR) systems (Bäck, Reference Bäck2003; Cronert & Nyman, Reference Cronert and Nyman2021). Municipalities are governed by a local council to which members are elected from multi‐member electoral districts in September every fourth year. The local councils typically consist of between five and nine parties, most of which are local‐level branches of the eight dominant national parties.Footnote 3 Municipalities have a ‘quasi‐parliamentary’ system, in which a majority coalition (or party) in the council appoints the mayor and the committee chairs. This governing coalition (or party) is commonly regarded as the equivalent of a national government and tends to exert a particularly strong influence on policy (Bäck, Reference Bäck2003).

Like in most other PR systems, single‐party majority governments are rare and governing coalitions are mostly formed through bargaining among the parties in the parliamentary arena. Also in line with international patterns, Swedish municipalities have seen an increase in the number of parties within the legislature as well as the governing coalitions over recent decades (SKR, 2019). Consequently, the bargaining processes have become more complex and unpredictable. Nonetheless, coalition formation analyses have shown that a strong connection still exists between the election results and the parties that enter the governing coalition (Cronert & Nyman, Reference Cronert and Nyman2021), meaning that incentives remain for governing coalition parties seeking re‐election to implement policies that are attractive to voters. However, it is likely that the link between electoral support and the likelihood of gaining government office has somewhat weakened over the past decades.

As to the local politicians' capacity to make decisions with relevance for future‐oriented policy‐making, it is worth noting that Swedish municipalities are both functionally and politically strong in international comparison (Kuhlmann & Wollmann, Reference Kuhlmann and Wollmann2014). They account for more than 50 per cent of total public employment and 27 per cent of total public expenditure, most of which is financed through a municipal income tax determined by the local council. They are responsible for a large number of policy areas, many of which are at the heart of long‐term governance. With regard to investments in physical capital, municipalities have far‐reaching responsibilities for important infrastructure such as water and sewerage, local road networks, waste and sanitation and energy production. As a result, the local government sector's gross fixed capital investment spending is now larger than that of the central government sector (Andersson Järnberg & Hultkrantz, Reference Andersson Järnberg and Hultkrantz2022). Not least due to local governments' responsibility for development planning, waste management and local roads, they have also been identified as a key actor in Sweden for mitigating climate change (Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, 2022).

Like most other advanced economies, Sweden has implemented a fiscal framework with the aim of combating deficit bias and achieving sustainable public finances. Since 2000, Swedish municipalities are required to plan their budget to achieve balance, and if deficits occur they should be corrected within 3 years. At the same time, the municipalities operate under a ‘golden rule’ stating that whereas current expenditures should not exceed current revenues, investment expenditures can be financed by issuing debt. Nevertheless, municipalities generally self‐finance an oftentimes substantial portion of their investments, and around half of them have adopted a full or partial self‐financing target (Dietrichson & Ellegård, Reference Dietrichson and Ellegård2014). In 2019, the share of investment expenditures funded by current expenditures and equity (as opposed to debt) averaged at 74.7 per cent (Statistics Sweden, 2021).

All in all, considering the stable electoral and fiscal institutions and the municipalities' extensive responsibility for future‐oriented policy‐making, our case should be fairly representative of observing presentist bias among politicians operating in a consensus‐oriented parliamentary democracy.

The survey

We developed an anonymous web‐based survey, which was distributed by e‐mail to all elected members of the local councils in the 290 municipalities for which an e‐mail address could be retrieved either from the municipality's web page or through correspondence with a municipal administrator.Footnote 4 A total of 12,257 local council members were invited, corresponding to 96.7 per cent of the population as defined by the Swedish Election Authority. The data collection period ranged from 10 November 2020 to 1 February 2021.Footnote 5 By that time, 3,925 individuals from 270 municipalities had participated in the survey, resulting in a response rate of 32 per cent.Footnote 6 Because our primary interest in this study lies with the incumbent government politicians, our analyses mostly focus on the politicians who state that their party is part of the incumbent local governing coalition – which constitutes around 55 per cent of total respondents.

An analysis of non‐response rates based on covariates available in the Swedish Election Authority data, reported in the Online Appendix (Table A1) reveals that Sweden Democrats, younger councillors, councillors from certain regions, and those who were placed lower on the party lists are under‐represented among respondents. Reassuringly, if we weigh the observations by the inverse predicted probability of responding – based on a logistic regression of response on these covariates – all our analyses yield almost identical results (not reported here to conserve space).

Results

Electoral competition

We begin our analysis by assessing the assumptions that (1) politicians believe that engaging in opportunistic present‐oriented policy‐making may improve their re‐election prospects and that (2) they are prepared to do so when anticipating a competitive election. We make this assessment by means of two direct questions and one experiment using the item count technique, also known as a list experiment.

Direct questions

The first direct question asked whether respondents ‘believe that the parties in the governing coalition would lose or gain votes’ by taking different policy actions, each of which was rated on a five‐level Likert item ranging from ‘lose many votes’ to ‘win many votes’. Three actions are directly related to long‐term governance, namely (1) reduce climate policy efforts to finance popular spending increases or tax cuts, (2) reduce investments to finance popular spending increases or tax cuts and (3) increase investments as the share of total expenditures. The main reason for phrasing the question this way rather than asking about, for instance, whether politicians perceive that voters have a myopic bias is that, as noted above, short‐sightedness is not the only type of voter bias that may incentivize politicians to engage in myopic policy‐making. What ultimately matters, thus, is whether politicians expect to be rewarded or punished by voters for policies with different inter‐temporal allocations, not what explains voters' responses. Relatedly, the reason for not specifying investments in more detail in the two latter items is to ensure that they do not tap into any ideological conflict but focus on the distinction between the short term and the long term.

The subsequent question read: ‘Suppose that the current governing coalition feels tempted to adapt its policies in order to be re‐elected in the next election. How do you think such an adaptation would be reflected in the municipality's economic policy?’ Here, respondents were asked to rate the likelihood of each policy action on a five‐level Likert item ranging from ‘very unlikely’ to ‘very likely’. Thus, whereas the first question concerns the potential electoral payoff that the local government could expect from engaging in opportunistic policy‐making, the second question concerns the likelihood that it will do so if tempted to increase its re‐election prospects.

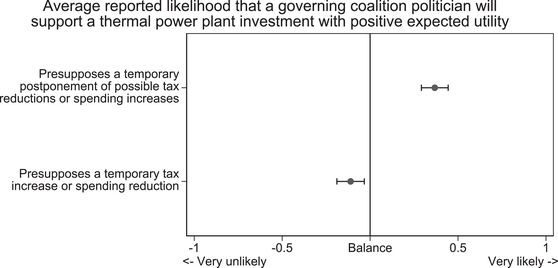

The left panel of Figure 1 reports, for each of the three long‐term governance‐related actions, the percentage of incumbent governing coalition politicians who find it likely (or very likely) and unlikely (or very unlikely), respectively. A balance score for each action represents the difference between the two percentages. The right panel reports the corresponding results for whether the politicians believe that they would gain or lose votes by taking the action in question.

Figure 1. Governing coalition politicians' perceptions of opportunistic policy adjustments with relevance for long‐term governance.

Note: Includes all governing coalition politicians,

![]() $N\hspace*{3.33333pt}$= 1,902–1,932. Respondents indicating the neutral midpoint option are omitted. Balance scores represent the difference between the two bars. Spikes are 95 per cent confidence intervals.

$N\hspace*{3.33333pt}$= 1,902–1,932. Respondents indicating the neutral midpoint option are omitted. Balance scores represent the difference between the two bars. Spikes are 95 per cent confidence intervals.

A first takeaway from this analysis is that neither policy action is regarded highly as an electoral tool by more than a small fraction of governing coalition politicians. On balance, all three actions are perceived as counter‐productive or at best futile (right panel) and as relatively unlikely to occur (left panel). At the same time – as indicated by the substantial differences in balance scores – the average respondent is nevertheless clearly more favourable towards increasing the investment share than towards reducing investments or climate policy when facing a competitive election. This suggests that electoral competitiveness may indeed be more likely to facilitate than to inhibit public investments.

A potential objection to such a conclusion is that respondents may not have had themselves in mind when answering this question but may rather have made assessments about others. Reassuringly, as reported in Figures A2 and A3 in the Online Appendix, very similar – and even slightly stronger – results emerge if we only consider respondents with an executive function or only those ranked in the top tier of their party's ballot,Footnote 7 who would arguably be the ones most likely to participate in such decisions. Furthermore, results are almost identical if we limit the analysis to respondents in the largest of the governing parties, who would reasonably be the most likely to expect their own policy positions to be implemented (Figure A4 in the Online Appendix).

Another potential objection is that politicians may not necessarily admit the full extent to which they would be willing to adjust policy based on electoral considerations. On that note, it is worth mentioning that not even the average respondent in the opposition parties tends to believe that the governing coalition politicians are likely to do so or have much to gain from it. This is indicated in Figure A5 in the Online Appendix, which shows that, for opposition politicians, all six balance points are strikingly close to zero.

A third potential objection is that this analysis does not take into consideration that politicians with different prospects of re‐election into the local government should be expected to have a different propensity to adjust its policy. To account for that factor, we asked respondents about their assessment – at the survey date – of the probability

![]() $p$ that their party will continue to be part of the local governing coalition after the elections in 2022, rated from 0 to 100. In the Online Appendix, Figure A6 shows that the share of governing coalition politicians who find it likely (or very likely) that the local government will increase investments as the share of total expenditure to improve its re‐election prospects is more than 50 per cent higher among those who are highly uncertain about their party being re‐elected into the governing coalition (

$p$ that their party will continue to be part of the local governing coalition after the elections in 2022, rated from 0 to 100. In the Online Appendix, Figure A6 shows that the share of governing coalition politicians who find it likely (or very likely) that the local government will increase investments as the share of total expenditure to improve its re‐election prospects is more than 50 per cent higher among those who are highly uncertain about their party being re‐elected into the governing coalition (

![]() $p\sim 50$ per cent) than among those who are just about certain that it will (

$p\sim 50$ per cent) than among those who are just about certain that it will (

![]() $p\sim 100$ per cent). Thus, even though the re‐election probability question was asked separately from the others, it appears that governing politicians' views about opportunistic policy actions are indeed related to their assessments of the competitiveness of the next election. This is a particularly interesting result considering the high level of uncertainty regarding both election outcomes and bargaining outcomes that goes into these assessments for most politicians.

$p\sim 100$ per cent). Thus, even though the re‐election probability question was asked separately from the others, it appears that governing politicians' views about opportunistic policy actions are indeed related to their assessments of the competitiveness of the next election. This is a particularly interesting result considering the high level of uncertainty regarding both election outcomes and bargaining outcomes that goes into these assessments for most politicians.

List experiment

Next, to take the risk seriously that electoral adjustments might be a sensitive issue, we included a list experiment about investment motivations in our survey. Such experiments have become a popular tool to elicit truthful answers to a sensitive question, by phrasing it in an indirect fashion (Glynn, Reference Glynn2013; Imai, Reference Imai2011). Specifically, we asked the following question:

Imagine that your municipality is considering building a bike trail to a community just outside the municipality's main town, in order for more people to be able to bike between home and work. How many of the following circumstances would make you less likely to support the proposed project? …

We only want to know how many of the circumstances would make you less likely to support the project, not which ones.

Respondents were randomly divided into a control group and a treatment group, the first of which was shown the following four items:Footnote 8

No cost‐benefit analysis of the bike path has been carried out.

The bike path would have to be routed through a protection‐worthy biotope.

The project proposal was not originally raised by your own party.

A petition indicates that many motorists are critical of the project.

The treatment group was shown the same four items, as well as a fifth one:

The first sod will not be turned until after the next election.

Respondents were asked to indicate a number between 1 and 5.Footnote 9 Using the standard difference‐in‐means estimator, we find that the average number of items reported by the treatment group is 0.175 (95 per cent CI: 0.099–0.251) higher than in the control group (

![]() $N$ = 1,831). This result suggests that around 17 per cent of respondents would be more reluctant to invest in a project for which the stream of visible benefits does not begin before the next election. How large is this effect? The four other items included in the experiment may provide a point of comparison. Although we obviously cannot separate between them, it is worth noting that respondents in the control group on average indicated a score of 1.76 out of 4 (44 per cent) pertaining to those four items. Accordingly, not having a visible stream of benefits before the next election is less than half as important an impediment to public investments as the average of the four other items.

$N$ = 1,831). This result suggests that around 17 per cent of respondents would be more reluctant to invest in a project for which the stream of visible benefits does not begin before the next election. How large is this effect? The four other items included in the experiment may provide a point of comparison. Although we obviously cannot separate between them, it is worth noting that respondents in the control group on average indicated a score of 1.76 out of 4 (44 per cent) pertaining to those four items. Accordingly, not having a visible stream of benefits before the next election is less than half as important an impediment to public investments as the average of the four other items.

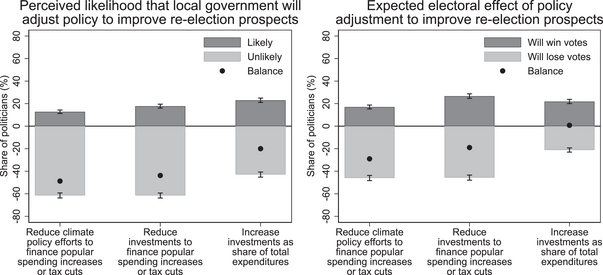

As noted above, it follows from theory that electoral considerations should be less important for politicians who perceive that their party has strong prospects of being re‐elected into the local government. To test this implication, we estimate the results of the list experiment separately for sub‐samples with different re‐election probability assessments in the interval of 51–100 per cent, using a rolling regression technique.Footnote 10 As reported in Figure 2, this analysis suggests that among those whose re‐election prospects are highly uncertain (

![]() $p\sim 50$ per cent), the effect of the experiment is more than three times larger than among those who are certain about being re‐elected (

$p\sim 50$ per cent), the effect of the experiment is more than three times larger than among those who are certain about being re‐elected (

![]() $p\sim 100$ per cent).

$p\sim 100$ per cent).

Figure 2. Results from item count experiment, by respondent's assessed re‐election probability. Note: Rolling regression of item count experiment, estimated once for each value on the x‐axis on a sample ranging from

![]() $p\pm 10$ per cent. Observations are weighted in inverse proportion to their distance from

$p\pm 10$ per cent. Observations are weighted in inverse proportion to their distance from

![]() $p$, with weights ranging from 1 (for

$p$, with weights ranging from 1 (for

![]() $p$) to 0 (for

$p$) to 0 (for

![]() $p-10$ and

$p-10$ and

![]() $p+10$).

$p+10$).

Conditions of financing

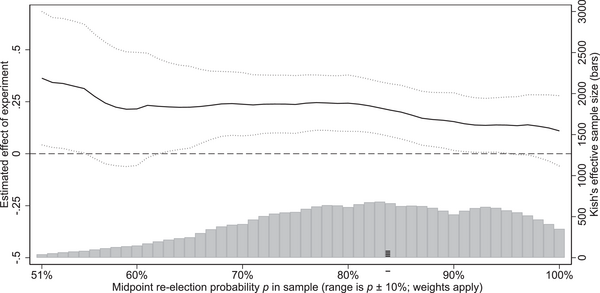

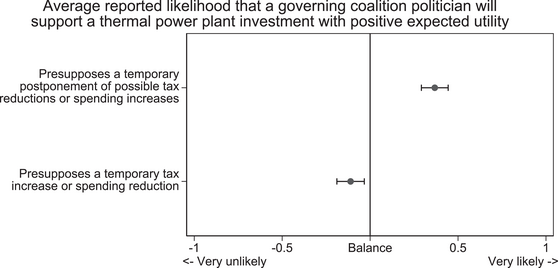

The next analysis serves to gauge how governing coalition politicians' support for public investments is causally impacted by the opportunity to have the short‐term costs imposed in the form of gains foregone rather than absolute losses. This analysis revolves around an experiment tapping politicians' willingness to support a proposal for an, arguably, fairly non‐controversial investment in an environmental‐friendly thermal power plant with positive expected utility. Specifically, we asked the following question, for which we randomly presented one of the two financing conditions included in brackets:

Imagine that your municipality is considering the construction of a new thermal power plant that would produce more electricity and be more environmental‐friendly than the existing one. In an investigation commissioned by the municipality, the value of the investment over its lifetime is estimated to exceed what the investment would cost. According to the municipal officials, however, the construction of the power plant presupposes that the municipality [temporarily raises the tax rate or reduces expenditures]/[temporarily postpones possible tax cuts and expenditure increases]. How likely is it that you would support the construction?

Respondents were asked to rate the likelihood of support on a five‐level Likert item ranging from ‘very unlikely’ (−2) to ‘very likely’ (+2). Figure 3 shows the average reported likelihood of support for the two groups. The results reveal, in line with Jacob's Reference Jacobs2016 hypothesis, that being able to provide finance out of existing surpluses is an important facilitator of public investments: The difference between the two scenarios amounts to almost ‐one half scale‐step (0.48) or 0.4 standard deviations in the likelihood rating. In fact, in the scenario where the investment presupposes a temporary tax increase or spending reduction, the average respondent leans towards not supporting it – despite it being estimated to have a positive expected utility. This finding indicates that unfavourable financing conditions are an important impediment to future‐oriented policy‐making.

Figure 3. Conditions of financing and politicians' investment support. Note: Includes all governing coalition politicians, N = 1,832. The likelihood rating ranges between −2 and 2. Spikes are 95 per cent confidence intervals.

How consistent are these patterns across political contexts?

What has been reported so far are average effects for governing coalition politicians across all municipalities in our sample. While we have chosen to analyse Swedish municipalities because they are similar with regard to most institutional and socio‐cultural factors, the municipalities also differ in terms of their political contexts in theoretically relevant ways. A natural follow‐up question, thus, is how consistently the reported patterns occur across such contexts. We here investigate three contextual factors highlighted in previous research on long‐term governance.

The first factor is the ideological composition of the incumbent local governing coalition. Although we have intentionally designed our survey instruments to be ideologically neutral, it is possible based on previous research that the future‐oriented policies that we focus on are nonetheless more salient for more egalitarian or socially progressive parties (Busemeyer, Reference Busemeyer2023; Jacobs & Matthews, Reference Jacobs and Matthews2012). Accordingly, governing coalitions consisting of such parties might therefore be the least likely to compromise on those policies due to electoral considerations or unfavourable financing conditions.

A second factor concerns the relationship between the parties in the governing coalition and the other parties in the local council. In contexts where the governing parties do not represent a majority in the local council, important policy decisions will require deliberations with the opposition parties. This requirement may prevent presentist bias by reducing the risk of policy reversal, helping to diffuse responsibility for short‐term costs of future‐oriented policy and empowering the opposition to counterbalance the ruling coalition's myopic opportunist tendencies (e.g., Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2016; Lindvall, Reference Lindvall2017). Third, it is possible that politicians' propensity to prioritize the long term is conditional on a favourable financial situation, since governments that face fiscal constraints may be compelled to focus the resources at hand on measures that address more immediate needs (e.g., Jacques, Reference Jacques2021).

Do these factors imply that our results are driven by coalitions that are dominated by right‐wing or conservative parties, enjoy majority status and operate under fiscal pressure – or do similar patterns occur also for other coalitions? To find out, we have re‐run the analyses reported above for three sets of sub‐samples: (1) left‐of‐centre, right‐of‐centre and cross‐cutting coalitions; (2) majority and minority coalitions; and (3) municipalities with a 3‐year budget balance either above or below the median.Footnote 11 These results are reported in Tables A7– A10 in the Online Appendix. There are some indications that left‐of‐centre coalitions are less likely to implement opportunistic policy adjustments and that majority coalitions and coalitions operating under fiscal pressure react more negatively to unfavourable financing conditions. However, the overall takeaway from these analyses is that both electoral competition and conditions of financing seem to matter for future‐oriented policy‐making, across all contexts investigated.

A related consideration concerns the generalizability of our findings beyond the particular cases we have examined – whether to other political systems or other policy instruments. While this is something that we cannot investigate empirically, we revisit the issue of external validity in our concluding discussion.

How important are these factors compared to others?

Having established that both electoral competition and conditions of financing matter, it is relevant to investigate just how important they are compared to other factors widely understood to impact long‐term governance. We did so by asking the following direct question:

Most public investments that are implemented are expected to result in a net profit for the municipality and its inhabitants. But there may also be other reasons why some investments are implemented and others are not. How important do you perceive that the following factors generally are when decisions about major investments are made in your municipality?

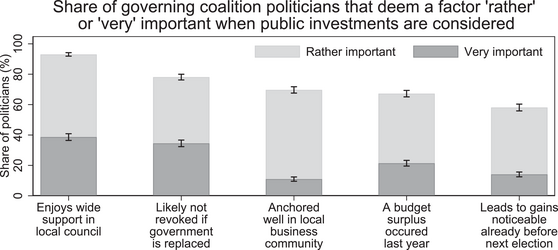

Respondents were asked to rate a number of factors as either very important, rather important, rather unimportant, or entirely unimportant. The importance of electoral competition was represented by an item stating that ‘the investment leads to noticeable gains already before the next election’, whereas the endowment effect was represented by a factor stating that ‘the local council reported a budget surplus last year’. Two items relate to political uncertainty around the realization of the long‐term gains, as stressed by Fiva and Natvik (Reference Fiva and Natvik2013), Jacobs (Reference Jacobs2016), Boston (Reference Boston2017) and others. One of them stated directly that ‘the investment decision will likely not be revoked in case the government is replaced’. A second one stated that ‘the investment enjoys a wide support in the local council' – a factor that should reduce the risks that resources are diverted away from the investment at a later stage. One item was intended to capture the role of organized cost bearers, whose opposition towards an investment is expected to be an important potential obstacle (Hughes & Urpelainen, Reference Hughes and Urpelainen2015; Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2016; Lindvall, Reference Lindvall2017). This item stated that ‘the investment is anchored well in the local business community’. Figure 4 reports the percentage of governing coalition politicians who rated the respective factor as either ‘rather’ or ‘very’ important.

Figure 4. Rated importance of political factors for public investments. Note: Includes all governing coalition politicians,

![]() $N$ = 1,832. The likelihood rating ranges between −2 and 2. Spikes are 95 per cent confidence intervals. Includes all governing coalition politicians,

$N$ = 1,832. The likelihood rating ranges between −2 and 2. Spikes are 95 per cent confidence intervals. Includes all governing coalition politicians,

![]() $N$=1,856–1,870. Spikes are 95 per cent confidence intervals.

$N$=1,856–1,870. Spikes are 95 per cent confidence intervals.

All of the theorized factors are considered ‘rather’ or ‘very’ important by around 60 per cent or more of governing coalition politicians. However, there are also interesting differences. The two highest ranking factors are those that serve to reduce the level of political uncertainty about the realization of long‐term benefits, namely that the investment enjoys wide support in the local council and that it is likely not to be revoked if the government is replaced. Support from the local business community appears less critical, especially considering the low proportion of respondents answering ‘very important’.Footnote 12

The two items representing financing conditions and electoral competition are ranked lower but still considered important by a clear majority of the respondents. The presence of a budget surplus from last year is deemed more important than an anticipation that the investment will lead to gains that are noticeable already before the next election.

Do electoral competition and conditions of financing matter for macro‐level policy outcomes?

From both a validity perspective and a policy relevance perspective, a natural follow‐up question arising from the micro‐level evidence presented so far is whether politicians’ views on electoral competition and conditions of financing are sufficiently important to matter for future‐oriented policy outcomes on the macro‐level. This question connects to the long‐standing scholarly discussion on whether parties, especially so at the local level, are in a position where they have sufficient discretion to implement their preferred policy while in government (Ferreira & Gyourko, Reference Ferreira and Gyourko2009; Rose, Reference Rose1984; Tiebout, Reference Tiebout1956; Tsebelis, Reference Tsebelis2002). Here it is worth mentioning that the party composition of Swedish local governments has indeed been found to matter for both economic and environmental policy (Folke, Reference Folke2014; Pettersson‐Lidbom, Reference Pettersson‐Lidbom2008). Besides, when we asked our survey respondents to rate how large an influence different actors have over policy‐making in their municipality, the influence of the governing coalition was rated on top, considerably higher than that of the municipal civil servants, the central and regional government as well as the opposition in the local council.Footnote 13

With regard to the specific question of how the electoral competition facing the incumbent government matters for long‐term governance, the only study to our knowledge that investigates this question in Swedish municipalities is that by Cronert and Nyman (Reference Cronert and Nyman2022) on the dynamics of public finances between 1998 and 2018. The authors investigated how two types of policy outcomes commonly associated with short‐termism – the budget balance and public investments – were affected by changes in the estimated probability of re‐election of the incumbent local government into office, caused by plausibly exogenous trends in national‐level vote intention polls observed over the election period. The results from that investigation are consistent with the evidence presented above: While it did not observe any effect at all on the budget balance, it found that when electoral competitiveness changed from its minimum value (a 100 per cent probability of re‐electing the incumbent local government) to its maximum (a toss‐up of 50 per cent) investments increased around 0.2–0.25 per cent of local GDP.

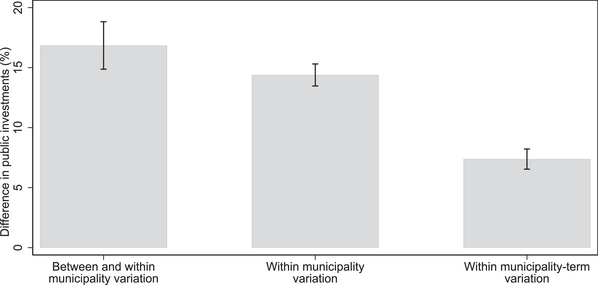

The data used in the said study also allow for analysing the role of financing conditions. Figure 5 reports differences in the predicted level of public investment in a given year, depending on whether or not the municipality reported a surplus in the previous fiscal year. Three models are reported, all of which are based on data from 289 municipalities over approximately 20 years and estimated using OLS regression. The left bar represents a simple bi‐variate regression model, the centre bar adds municipality‐fixed effects and the right bar adds fixed effects for each 4‐year government term in each municipality. In all specifications, the level of investments is substantially and significantly higher in years that were preceded by a surplus, although the difference is reduced from around 17 to around 7 per cent when only within municipality‐term variation is considered.

Figure 5. Public investments following a budget surplus vis‐a‐vis a deficit. Note: The graph shows how much larger public investments are during years following a budget surplus compared to years following a deficit. The estimates are predictive margins from OLS regressions of public investments, estimated on 289 Swedish municipalities during 1998–2018 (

![]() $N$ = 5,478). Left: Bivariate regression. Centre: Adds municipality fixed effects. Right: Adds municipality#election‐term fixed effects.

$N$ = 5,478). Left: Bivariate regression. Centre: Adds municipality fixed effects. Right: Adds municipality#election‐term fixed effects.

To be sure, the surpluses are not strictly exogenous even in the most restricted model. Nevertheless, the data reveal a clear pattern consistent with the experimental evidence that politicians are more willing to prioritize public investments when they are able to fund them in the form of gains forgone rather than absolute losses.

Concluding discussion

Much of the existing literature on future‐oriented policy‐making operates on assumptions about politicians' inter‐temporal preferences and biases that have not yet been verified. This study has sought to help unpack the black box of long‐term governance by conducting survey experiments to investigate to what extent politicians in the incumbent local governments in Sweden face incentives to trade off the long‐term against the short‐term opportunistically when facing competitive elections or liquidity constraints. The main takeaway is that if we are concerned about the effects of voters' biases on long‐term governance in a case like this, the biases that are linked to the conditions of financing appear more important to address than those linked to electoral competition.

Weighing up the findings from the first experiment and the direct questions about the electoral competition, it appears that a small minority of incumbent governing coalition politicians expect that voters would reward electoral adjustments of policy, and a similarly small proportion appear prepared to engage in such opportunistic behaviours. However, on balance, these politicians expect that electoral adjustments that increase investments are more effective with the voters and are more likely to occur than on those that reduce investments or climate policy efforts. In other words, while some politicians do show opportunistic tendencies triggered by electoral competition, our results do not support the popular notion that (their perceptions of) voters' susceptibility to electoral manipulations as such serve as a major impediment to future‐oriented policy‐making – a conclusion further substantiated by recent evidence on local government expenditure patterns.

At the same time, it is clear from the second experiment that, in line with Jacobs (Reference Jacobs2016), the possibility of bearing the costs of a public investment by temporarily postponing possible tax cuts and expenditure increases (i.e., by gains forgone) instead of temporarily raising the tax rate or reducing expenditure (i.e., by absolute losses) has a substantial positive effect on politicians' support of public investments. Whether this large effect is indeed due to perceptions about endowment effects among voters, or to some other political or administrative factor that may make losses difficult to impose emerges as an important follow‐up question for later studies. In any event, given the magnitude of this effect – and the fact that it is reflected in macro‐level investment expenditure data – the conditions of financing are a problem that warrants more attention in future research on long‐term governance.

Having said that, it is also clear that the two aforementioned factors are deemed less critical for investment decisions than factors related to political uncertainty and, to a lesser extent, the possible opposition of business interests. Taken together, these findings have important implications, not least for the voluminous research on inter‐temporal trade‐offs in policy‐making that relies on the assumption of electoral competition as a key driver of policy myopia (e.g., Boston, Reference Boston2017; Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2011; Krznaric, Reference Krznaric2020).

Considering the widespread adoption of fiscal policy frameworks among democracies, and recent evidence of similarities in the cognition and perceptions of politicians and across democracies and at different levels of government (e.g., Pereira, Reference Pereira2021; Sheffer et al., Reference Sheffer, Loewen, Soroka, Walgrave and Sheafer2018), there are reasons to believe that these findings extend beyond Swedish local politics – at least to other consensus‐oriented parliamentary democracies. An important follow‐up question, however, is whether different response patterns will emerge in policy‐making contexts with weaker fiscal institutions or less consensus‐oriented political systems, and, if so, whether there is a corresponding consistency between the micro‐level perceptions and the macro‐level policy outcomes also in those contexts.

As to political systems, we see two reasons why the conventional assumptions that electoral competitiveness triggers myopic policy‐making may be more valid in countries with a majoritarian, or Westminster, model of democracy than in countries with a consensus‐oriented PR model like the Swedish (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012). In the tradition of Lijphart, we might expect that in consensus‐oriented systems, where the link between parties' election results and actual policy‐making influence is weaker, politicians have less incentives to reach the executive office and thus less reasons to behave opportunistically. In addition, the larger number of parties involved in executive and legislative decision‐making as well as the greater involvement of organized cost bearers in these systems may reduce the risk of future policy reversals and facilitate blame diffusion to the benefit of future‐oriented policy (Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2016; Lindvall, Reference Lindvall2017). Furthermore, a more direct effect of the strong proportionality of a PR system like the Swedish is that the median voter – rather than the voters in any particularly contested district – tends to be the pivotal actor in electoral competition (Hobolt & Klemmensen, Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2008). Generally speaking, we might expect that the type of opportunistic policy adjustment needed to appease the median voter needs to be more broadly targeted – and thus more costly – than a pork barrel project aimed at swing voters in a particular district. For these reasons, politicians in majoritarian systems may be more compelled to engage in opportunistic behaviour that favours the short term over the long term.

Short‐sighted policy‐making may also be more pronounced in areas beyond those covered in our study. We chose to focus on relatively uncontested policies to avoid conflating the inter‐temporal conflict – that is our primary interest – with ideological considerations. Climate policy and public investments are key areas for future‐oriented policy‐making. As such, these may also be the areas where the most substantial progress has been made in developing institutions and raising awareness to counter policy short‐sightedness. An important task for future research will thus be to examine whether myopic policy‐making is more common in other policy areas or investments with a stronger ideological content.

Anyhow, a tentative optimistic interpretation of the results reported here is that the factors deemed most important for future‐oriented policy‐making in the present context are those that primarily have to do with the ways in which politicians behave towards each other, such as whether they strive to establish broad agreements in the local council and whether they tend to revoke decisions made by their predecessors. These factors should be easier to address than factors linked to any innate human condition of voters. Arguably, the prospects of long‐term governance would have looked much bleaker had those items been the ones deemed most important by the policymakers.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to seminar participants at the 2021 SASE conference and at Uppsala University, as well as Olivier Jacques, Jonas Larsson Taghizadeh and Marcus Österman for valuable comments on earlier versions of this study. Thanks also go to Vinicius Ribeiro for excellent research assistance.

Conflicts of interest statements

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Information

Financial support from Forte, Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare [2017‐01121] is gratefully acknowledged.

Ethics statement

Approval for this study was granted by the Swedish Ethical Review Agency (2020‐00498).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

N

N

p±10

p±10 p

p p

p p−10

p−10 p+10

p+10

N

N N

N

N

N