Introduction

There is often a public outcry in reaction to images exemplifying male dominance in executive domains. The picture of Donald Trump surrounded by men only as he signs a bill cutting all US funding for abortions abroad is one recent and well‐known example. Another is Angela Merkel in a bright coloured suit accompanied by men in dark suits at a world leader summit. The outcry triggered by such images stems from the view that all‐male leadership is undesired, and that we should take action to achieve gender balance in leadership. There is, however, less agreement on why the imbalance is wrong, or on where gender balance is desirable, that is, should we aim for balance in all levels and areas in social, economic, and political life? Our research contributes to our understanding of what makes people more, or less, in favour of gender quotas.

So far, we know a lot about who tends to support gender quotas. Scholars have shown that, overall, women are more supportive of gender quotas than men (Barnes & Córdova, Reference Barnes and Córdova2016; Keenan & McElroy, Reference Keenan and McElroy2017), though this effect largely coincides with ideological leanings (Beauregard, Reference Beauregard2018; Gidengil, Reference Gidengil1996; Morgan & Buice, Reference Morgan and Buice2013). Attitudes toward government intervention are also important (Barnes & Córdova, Reference Barnes and Córdova2016). We further know that women's equal presence legitimizes decisions (Arnesen & Peters, Reference Arnesen and Peters2018; Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, O'Brien and Piscopo2019).

However, we know less about what type of information may convince someone to support gender quotas. Some studies speak to this question in general terms. Research has, for example shown that facts affect a citizen's position about gender quotas in politics (Coffé & Reiser, Reference Coffé and Reiser2021; Sanbonmatsu, Reference Sanbonmatsu2003; Stauffer, Reference Stauffer2021). Teigen and Karlsen (Reference Teigen and Karlsen2020) further show that elites can be susceptible to pro‐quota framing at corporate boards. In this article, we advance this area of research by examining the extent to which information about the why and where of gender imbalance affects support for one important measure to achieve gender balance, namely gender quotas. More specifically, we consider the effect of social utility and group justice arguments, as well as the effect of proposing gender quotas for political, business and religious leadership, on support among citizens and political representatives.

We use a country, Norway, where there is minimal political polarization on the issue of gender quotas. This would imply that the issue is uncrystallized, as this refers to a situation where a policy cannot be strongly identified on the platforms of the major parties (Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, O'Brien and Piscopo2019; Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge1999). Opinion studies of lawmakers have also found that political parties do not hold coherent attitudes on gender quotas (Bohigues & Piscopo, Reference Bohigues and Piscopo2021). This may imply that party identification affects citizens’ opinions on quotas only minimally. It is worth noting that Norway, even if known for party pluralism and consensus on gender equality, does not have legislative gender quotas, and despite a quota for listed companies the proportion of women on boards in private firms is currently 20 per cent.Footnote 1 In this case, it is plausible that respondents may consider the given information and that it can either encourage or undermine support, depending on the content.

Using a citizen‐elite paired survey experiment, we test 1) whether support for gender quotas is affected by the type of argument that is used to promote the quota, 2) whether support is affected by information about where the quota is applied, and 3) to what extent the two populations – citizens and elected representatives – are similar to each other in their support for gender quotas. By comparing citizens’ and political representatives’ support for gender quotas directly, we aim to gain additional insights into the dynamics of representation and opinion formation when it comes to gender equality. These two groups are directly connected through elections, but we have minimal research so far on whether these two different groups think alike in questions related to gender quotas, considering they have different experiences and may be presented with different perspectives on the issue. Moreover, the support of both citizens and political elites is necessary, forming a larger pool of potential for actual change in regulation. It is thus important to consider both types of respondents when examining support for quotas.

Our study presents compelling evidence for how information on the why and where of gender quotas matter for support. We find that an argument promoting common benefits without challenging men's capabilities is generally effective in promoting support, and that support for gender quotas in religious leadership tends to be relatively high. Moreover, we observe that the information does not have the same effect on all people. It is especially those people less likely to hold fixed opinions on the issue, that is, younger and male citizens, who are more affected by arguments. Support for gender quotas, further, was lower among respondents when the policy would affect them directly. Interestingly, representatives of the Conservative Party and citizens of the Progress Party tend to express higher support for quotas in religious institutions. Digging deeper into these conditional effects, we find that those sceptical of immigration are more supportive of quotas in religious leadership than in other sectors. We theorize that this may be due to a desire to control an ‘out‐group’ using national values such as gender equality.

How support is affected by information exposure

Public opinion research and the field of political psychology has long studied the way that people form their opinions, and how information affects those opinions. At the core, people have some structure of values that may form an underlying ideology which is built over time through, for example, experiences, knowledge and socialization. This structure can be more, or less, coherent and may be the basis for people's opinions on certain political issues (Feldman, Reference Feldman, Huddy, Sears and Levy2013). While some public opinion scholars question whether citizens indeed possess a coherent value‐structure (e.g., Converse, Reference Converse and Apter1964), others proposed that citizens have values but that they are conflicted about many issues. Expressions of opinion may therefore fluctuate due to a probabilistic memory‐search triggered by context (Taber & Young, Reference Taber, Young, Huddy, Sears and Levy2013; Zaller & Feldman, Reference Zaller and Feldman1992).

People can ‘store’ new information in their long‐term memory in an organized way. This, and related information, can be retrieved into the working memory through activation, such as, reading about a specific topic (Taber & Young, Reference Taber, Young, Huddy, Sears and Levy2013). These pieces of information, together with the latent value‐structure, can form the basis for expressed opinions. In particular, information and context may help determine what information is recalled, and attitudes can be constructed from those (Zaller & Feldman, Reference Zaller and Feldman1992). As such, opinions of people are, to some extent, conditional on the information that they are given. For example, Gilens (Reference Gilens, Manza, Cook and Page2002) discusses the wide difference in opinion on cutting spending on ‘welfare’ or on ‘assistance to the poor’ to illustrate how the frame of essentially the same question affects people's opinions. The two terms likely affect which information and associations are retrieved from people's long‐term memory, thus resulting in different opinions. Issue frames can enhance the psychological relevance of an issue, and information can sometimes change people's underlying beliefs (Nelson & Oxley, Reference Nelson and Oxley1999).

Within the scholarship on politics and gender there is an emerging literature looking into how misperceptions affect public opinion on issues related to political representation (Coffé & Reiser, Reference Coffé and Reiser2021; Sanbonmatsu, Reference Sanbonmatsu2003; Stauffer, Reference Stauffer2021). Some studies find that information about descriptive representation – the demographic similarities between representatives and those they represent – affect support for increasing women's representation and introducing gender quotas (Coffé & Reiser, Reference Coffé and Reiser2021; Sanbonmatsu, Reference Sanbonmatsu2003). Particularly those who overestimate women's representation are likely to change their views and support quotas when they learn that the actual share of women is lower than they thought (Coffé & Reiser, Reference Coffé and Reiser2021). A similar finding is found in a study of support for corporate gender quotas: Information about male dominance in businesses made elites more positive to adopt gender measures (Teigen & Karlsen, Reference Teigen and Karlsen2020).

While factual information about unbalanced representation is found to affect opinions, we know less about how, why and if normative arguments change people's beliefs. The spread of gender quotas throughout the world has been in part attributed to carefully developed pro‐quota arguments (see e.g., Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Paxton and Krook2017) and serves as a fruitful area of research to test whether some of the most commonly applied arguments affect attitudes. For example, research has shown that knowledge about hidden structures ‘blocking’ women's access to power has spurred an unprecedented interest in adopting gender quotas to advance women into leadership positions (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Paxton and Krook2017; Krook, Reference Krook2009; Piscopo, Reference Piscopo2015; Schwindt‐Bayer, Reference Schwindt‐Bayer2009; Tripp & Kang, Reference Tripp and Kang2008). Yet, while there is research looking into what type of arguments politicians use to back their opinions in parliamentary debates (Chandler, Reference Chandler2016; Cowell‐Meyers & Younissess, Reference Cowell‐Meyers and Younissess2021; Meier, Reference Meier2014; Piscopo & Muntean, Reference Piscopo and Muntean2018), less is known about how arguments – beyond that of pointing to gaps in numbers – affect opinions.

We investigate the conditionality of people's opinions on gender quotas. In particular, we study whether different pro‐argument frames result in different levels of support for quotas, and whether it matters where they are applied. Through a survey experiment, we test how people react to two different pieces of information, that is, the why and the where. The character of these pieces of information differs in that the why contains issue framing, whereas the where offers the respondent more precise information about the issue. Because information and frames can activate predispositions, such as their internal value structure, and heighten issue salience, we expect that individuals’ support for gender quotas is affected by the issue frames and specifying information.

Furthermore, we expect that the reaction to the information depends on the individual's background. On the one hand, we expect that certain issue frames resonate better with people who have a certain value‐structure, while others may resonate with another value‐structure. This would be similar for the information about the where. On the other hand, we expect that people who are more informed and are likely to have well‐developed attitudes will also be less likely to be affected by our issue frames. This may be similar to information about the where, but depends on the familiarity of the area. Specifically, gender quotas in religious organizations is a not‐much debated issue which may require more ‘on‐the‐spot’ evaluation to form an opinion, even by those who are knowledgeable about gender quotas. Below, we further develop our expectations.

Type of justification (why)

Gender quotas are measures used to change the composition of decision‐making bodies to secure a specified level of gender balance. The key argument for quota adoption is that a measure is needed because changes in women's presence do not happen through organic processes (Kogut et al., Reference Kogut, Colomer and Belinky2016; Piscopo & Muntean, Reference Piscopo and Muntean2018; Terjesen & Sealy, Reference Terjesen and Sealy2016). Many pro‐quota arguments involve explaining why increased inclusion of women is important, and stress its positive impact on various factors, such as policy making (Clayton & Zetterberg, Reference Clayton and Zetterberg2018; Weeks, Reference Weeks2018); legitimacy and democracy (Arnesen & Peters, Reference Arnesen and Peters2018; Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, O'Brien and Piscopo2019), the quality of leadership recruitment (Barnes & Holman, Reference Barnes and Holman2020; Folke & Rickne, Reference Folke and Rickne2016), and symbolic role modelling (Alexander, Reference Alexander2012). Scepticism towards gender quotas is not limited to sexist views regarding women's leadership quality and appropriateness, but also involves the necessity of adoption (e.g., according to the pipeline theory distortions will solve by time) or worries over tokenism (Bjarnegård & Zetterberg, Reference Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2022; Muriaas & Wang, Reference Muriaas and Wang2012; Tripp, Reference Tripp2024). Recent survey research adds to this complexity by pointing to ‘benevolent sexism’ – women need gender quotas because they do not have what it takes to succeed without it (Beauregard & Sheppard, Reference Beauregard and Sheppard2021; Pereira & Porto, Reference Pereira and Porto2020).

Our experimental approach narrows the gaze to a set of moral claims about what gender quotas may achieve if adopted. We distinguish between two types of moral justifications for gender quotas: arguments about social justice and arguments about social utility (Hernes, Reference Hernes1987; Teigen, Reference Teigen2000). These two approaches differ in that justice arguments emphasize fair procedures, while social utility arguments are concerned with outcomes (Mensi‐Klarbach & Seierstad, Reference Mensi‐Klarbach and Seierstad2020). The justice argument has its origin in social liberalism and emphasizes universal and equal citizenship. Due to historical marginalization, women have fewer resources to organize effectively (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge1999; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Muriaas and Wang2023), and need different treatment than men in order to secure equal access to public policy making (Phillips, Reference Phillips1995; Young, Reference Young1990). The emphasis is thus on procedural justice. Giving one group preferential treatment can be seen as unfair for those not getting it, and is often cast as a way to set meritocracy aside. This, in turn, can be negative for the target group as it casts doubt on their competence (Moscoso et al., Reference Moscoso, García‐Izquierdo and Bastida2010). While there are many nuances, the fairness justifications can be seen to have negative consequences for the ‘in‐group’ (i.e., men are challenged), and for the overall outcome (i.e., competence and meritocracy suffer). We include one social justice argument in our design.

Social utility arguments follow a different reasoning (Skjeie & Teigen, Reference Skjeie and Teigen2005), namely that the inclusion of women is crucial for good outcomes. The claim is not that women are given the opportunity to front their interests (substantive representation), but that the whole society will gain from women's presence in leadership because diversified institutions and organizations will take better decisions. We consider here arguments that a) emphasize women's different insights and b) the untapped resources by excluding women. The women's insights perspective argues that there are gender differences in management styles, attitudes, experiences and interests. More women in male‐dominated leadership will promote new perspectives and ways of solving problems, which will result in higher productivity and a better working environment (Teigen, Reference Teigen2000). Women complement men as they offer something distinctively different so that power‐sharing adds value (Sénac‐Slawinski, Reference Sénac‐Slawinski2008). Gender groups will be represented more descriptively, and with that probably also more substantially (e.g., Bratton & Ray, Reference Bratton and Ray2002; Reher, Reference Reher2018). The longer‐term advantage is also that the inclusion of women in leadership will encourage other women to be involved more in politics for instance. While this outcome is true for any of the arguments in favour of gender quotas, it is particularly emphasized under the women's insights perspective. This framing is sometimes criticized for its essentialist underpinnings, however, and the assumption that men and women behave differently in similar roles (Kanter, Reference Kanter1977). It is a way to argue for the feminization of politics rather than the inclusion of feminist perspectives (Celis & Childs, Reference Celis and Childs2020; Childs & Webb, Reference Childs and Webb2011).

The second social utility argument – the loss of talent frame – also emphasizes better outcomes, but here because male‐dominance signals an untapped female potential (Skjeie & Teigen, Reference Skjeie and Teigen2005; Tatli et al., Reference Tatli, Vassilopoulou and Özbilgin2013; Teigen, Reference Teigen2000). If women's potential is underutilized the natural pool of talent is cut in half (Hernes, Reference Hernes1987). The argument is that stereotypes and bias, rather than talent, leads to the recruitment of men over women (Terjesen et al., Reference Terjesen, Aguilera and Lorenz2015), that is, the overrepresentation of men implies an unfair advantage due to their sex (Murray, Reference Murray2014, p. 522). One critique of this perspective is that the main rationale is about the benefits of gender balance (Elomäki, Reference Elomäki2018), that is, the framing reduces women into economic actors and make women's exclusion an economic rather than a democratic problem (Brown, Reference Brown2015). Another interpretation is that an enlarged pool of candidates has symbolic effects beyond that of increased women's inclusion, because it also sends a signal that these institutions are open to a wide array of both people and viewpoints (Schwindt‐Bayer, Reference Schwindt‐Bayer2009).

Because the two social utility arguments for gender quotas emphasize better outcomes and benefits for all, while the fairness argument suggests that equality comes at various costs, we expect that the social utility frames will encourage positive evaluations of gender quotas due to the suggestion of better outcomes in addition to gender equality.

H1. Social utility frames encourage more support for gender quotas than a fairness frame.

We further expect a difference in reaction between the two utility frames. The women's insights frame tends to emphasize a quality that adds to, and is distinct from, existing (male) skills. It does not challenge the male dominance as such, rather that it may be improved by something men cannot offer. Women are additions, not substitutes. The talent frame, however, suggests that male dominance is illegitimate: they do not have more talent but are unfairly benefitted. The talent frame thus suggests a direct competition between men and women which could encourage more negative evaluations of gender quotas, resulting in less support.

H2. The women's insights frame encourages more support for gender quotas than the talent frame.

Area of application (where)

Most research on gender quotas has focused on quotas in politics, with a recent upswing in studies examining corporate board quotas (see e.g., Engeli & Mazur, Reference Engeli and Mazur2022; Latura & Weeks, Reference Latura and Weeks2022; Mensi‐Klarbach & Seierstad, Reference Mensi‐Klarbach and Seierstad2020). Piscopo and Muntean (Reference Piscopo and Muntean2018) discuss how quotas in politics differ from those for corporate boards. Corporations have consumers, not constituents, and discussions regarding electoral competition and public accountability do not easily apply to business. Yet, as both debates revolve around the lack of women in leadership roles – and the broken promise of pipeline theories – there is a common concern about a glass ceiling in both sectors (Piscopo & Muntean, Reference Piscopo and Muntean2018). However, we know little about how people's views on gender quotas vary between different areas. We contrast two established areas of application, that is, the areas of politics and corporate boards, with applying gender quotas in the leadership of religious organizations, that is, an area that is less debated.

On the one hand, one could expect that the area of institutional application does not affect attitudes towards quotas. In a study of parliamentary debates, Meier (Reference Meier2014) concludes that there is a great deal of overlap and parallels between the debates on gender quotas in the various spheres. Moreover, even if legislative quotas regulate parties and relate to fairness and democracy, and corporate quotas address the negative consequences of capitalism and remains outside the state, the two policies reflect similar conceptualizations of equality and democracy (Cowell‐Meyers & Younissess, Reference Cowell‐Meyers and Younissess2021). Respondents would recall and evaluate information from their long‐term memory that is related to gender quotas and women in leadership roles in general, and express their support accordingly. Some people think the use of quotas is good or necessary; others do not.

On the other hand, it is likely that information about the specific area of applying the gender quota matters if we go beyond the two most common types of policies – politics and corporate boards. When a new issue has emerged on the agenda, there is an ‘absence of general agreement about how to construe them, whereas older issues have a defined structure and elicit more routine considerations’ (Chong & Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007, p. 108). Thus, when quotas are proposed in areas previously lacking discussions of gender equality, people may engage in more conscious evaluation of the information and values they have. Support for quotas in religious leadership may therefore be less automated than for the other two areas. Religious leadership likely triggers explicit views of gender inequality compared to the areas of business and politics, even if this is not necessarily the case. Gender quotas may be seen as needed or more justifiable in an area where more inequality is observed. On the contrary, it is also plausible that many think that religious boards are institutions that should not be controlled as they are related to private/intimate life, unlike politics and businesses which are public. Previous studies have found that gender equality reforms affecting private rights are more prone to resistance than those challenging public rights (Benstead et al., Reference Benstead, Muriaas and Wang2022; Htun and Weldon, Reference Htun and Weldon2018). Still, as the questions about gender balance in religious boards do not regulate people's private lives but access to organizational leadership, we expect that people will express more support for gender quotas in religious boards.

H3. Proposing to apply gender quotas to religious structures encourages more support than to the political or business structures.

Whose support is affected by information exposure

We expect that arguments affect the support of some people differently than others. They respond differently to information depending on their own background and observation of the situation (Möhring & Teney, Reference Möhring and Teney2020). Specifically, we expect that ideology, age, gender and citizen – or representative status affects how arguments affect support for quotas. Regarding ideology, studies of representatives and candidates find a partisan effect; those on the left are overall more positive towards quotas than those on the right (Dubrow, Reference Dubrow2011; Keenan & McElroy, Reference Keenan and McElroy2017). More specifically, those on the right may be more supportive of gender quotas when a benefit is pointed out (utility arguments) than by emphasizing fairness. Those on the left may be supportive simply because they want equality regardless of what argument is being used.

Further, previous studies find that people who already hold firm beliefs on an issue are less likely to be influenced by cues (Bullock, Reference Bullock2011, p. 510; Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2010). Justifications may thus affect younger people and males more than older and female people. Following research on crystallization of political views, we assume that the young will still be in the process of developing their political views and that we can expect more fluctuation in opinions (Henry and Sears, Reference Henry and Sears2009). Among older generations, we may expect increased learning resistance that affects the likelihood of listening carefully to information and updating their views; making them more likely to recall the already‐constructed views from their long‐term memory. Consequently, the young would be convinced by some arguments over others, more than older citizens. Similarly, men would have less well‐formed views on the issue than women and may be convinced by some arguments over others. Previous studies have, for instance, found that men's attitudes are more likely to be affected by framing of a gender equality issue (Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, O'Brien and Piscopo2019; Morgan & Buice, Reference Morgan and Buice2013, p. 646). We do not have particular expectations on which argument would boost support most among the young and men.

Extending this argument, people who are heavily engaged in politics have views that are more set than those who are not engaged (Keenan & McElroy, Reference Keenan and McElroy2017). Consequently, elected representatives are unlikely to alter their pre‐set views on quotas in reaction to a pro‐gender argument. Frames may have a stronger impact on ordinary citizens, who tend to engage less in politics. We do not have particular expectations on which argument would encourage most support.

H4a. Utility arguments encourage more support among those on the right‐wing, than fairness.

H4b. Pro‐quota arguments affect young people's support more than that of older people.

H4c. Pro‐quota arguments affect men's support more than that of women.

H4d. The conditional expectations stated in H4a, H4b and H4c are more likely to hold for citizens, than they are for elected representatives.

We extend the rationale of having fixed or more pliable views on gender quotas also to the area of application. However, arguments in favour of gender quotas and where they might apply are different pieces of information. Besides one's (fixed) predisposition on gender quotas and one's general views on state intervention, one's perception of the equality situation within an area (the perceived need) can also affect support for quotas in different areas. This would particularly apply to religious leadership compared to political and business leadership since most people will have unfixed views on this. At the same time, those who have been more exposed to the gender equality debate, that is, older and female people, will differentiate their support according to their perception of the area, and whether it may need quotas to stimulate equality. Especially religion may be seen as more unequal in part due to more traditional gender differentiation in many religions, even if this is not necessarily the case anymore. This implies that female and older citizens, those likely holding fixed views and possibly recalling traditional gender differentiation from long‐term memory, may be more affected by information about quotas in religious leadership than in other areas. Further, right‐wing citizens may oppose quotas in business on the principle of opposing state intervention in the market, though may be rather supportive of quotas in religious leadership as an area viewed as gender unequal. While discussions related to quotas in religious leadership are not widespread, representatives have initiated the budding debate. This, again, would mean that they are overall likely to hold fixed views on gender quotas, meaning that effects of age, gender and ideology would be less prominent than among citizens.

H5a. Proposing to apply gender quotas to religious structures encourages more support among right‐wing people, than applying them to business structures.

H5b. Proposing to apply gender quotas to religious structures encourages more support among older people, than applying them to other areas.

H5c. Proposing to apply gender quotas to religious structures encourages more support among women, than applying them to other areas.

H5d. The conditional expectations stated in H5a, H5b and H5c are more likely to hold for citizens, than they are for elected representatives.

Furthermore, it is likely that people's preferences for gender quotas are influenced by whether they are directly affected by the policy (Meier, Reference Meier2014). Following the logic that some people's views are more weakly held and thus more malleable, we argue that people have more set preferences when it concerns areas in which they themselves operate. Examining Norwegian elites, Skjeie and Teigen (Reference Skjeie and Teigen2005) indeed find that many leaders are more positive towards affirmative action in sectors other than their own. We therefore expect that elected representatives are less supportive of gender quotas in politics than in other areas. Moreover, following Dubrow (Reference Dubrow2011) we may also expect that representatives from religious voters or parties specifically associated with a religion are more sceptical to gender quotas in religious institutions. A similar resistance could be expected for the more business‐friendly parties (the conservative and progress parties) regarding quotas in corporate boards. The Conservative Party has played an important role in the implementation of quotas for corporate boards in Norway, however, shedding some doubt on this expectation.

H6a. Elected representatives are less supportive of gender quotas in politics, than in business or religion.

H6b. Christian Democrats are less supportive of gender quotas in religion, than in politics or business.

H6c. The Conservative and Progress parties are less supportive of gender quotas in business, than in politics or religion.

Gender quotas in Norway

Norway is a case with high levels of gender equality, but when it comes to legislated gender quotas, there is only a gender quota for the board of listed, but not non‐listed, firms. This quota policy for corporate boards was a consensus decision including the Conservative Party. In the early 2000s, the percentage of female corporate board directors was below 7 per cent (Ford & Rohini, Reference Ford and Rohini2011, p. 6). A new regulation on the composition of publicly owned boards set a 40 per cent threshold for both genders in 2003 and was expanded to all publicly traded firms in 2008. Non‐compliance with the regulation is sanctioned by refusal to register boards, dissolution of the company and/or fines until compliance is achieved (Terjesen et al., Reference Terjesen, Aguilera and Lorenz2015, p. 235). These reforms were supported by all major parties except for the Progress Party – a party that won 11.6 per cent of the parliamentary elections in 2021. The portion of women on boards in non‐listed firms remains below 20 per cent.

Beyond this, there are party quotas. Women's shares of seats in the Parliament and in elected local councils have remained at approximately 30 to 40 per cent since the late 1980s (Folkestad et al., Reference Folkestad, Saglie and Segaard2017; IPU, 2019). Most major political parties have internal regulations for the gender composition of party bodies and party electoral lists (Skjeie & Teigen, Reference Skjeie and Teigen2005). The two major parties without party quotas are Høyre (the Conservative Party) and Fremskrittspartiet (the Progress Party). There is no party that ‘owns’ the topic of gender quotas in Norway and respondents are not likely to use party identification as a heuristic shortcut in expressing their support for gender quotas.

The idea of adopting gender quotas for the leadership of religious organizations is a rather new topic. The issue got public exposure through a study of the leadership of Christian churches which showed that women held a majority of seats in boards of the Norwegian Church and the Methodist Church (Norges Kristne Råd, 2018, p. 9), though ‘free churches’ such as the Pentecostals had lower levels of gender balance. The Evangelic‐Lutheran Church Community included even fewer than 10 per cent women. A study conducted by the Norwegian broadcaster (NRK) further showed that 15.6 per cent of ‘free churches’ did not have any women on their board, nor do 70 per cent of Norwegian mosques (Strand & Yusuf, Reference Strand and Yusuf2019). Currently, gender quotas for boards in religious organizations are formally supported only by one of the biggest parties in Norway, the Labor Party (Arbeiderpartiet). This party suggested that the public funding of communities of faith currently provided by the government based on membership numbers (Siim & Skjeie, Reference Siim and Skjeie2008) should be tied to a gender equality target of 40 per cent of each gender in their boards. However, although the topic has featured in some news outlets, the issue is not discussed publicly by any party leaders.

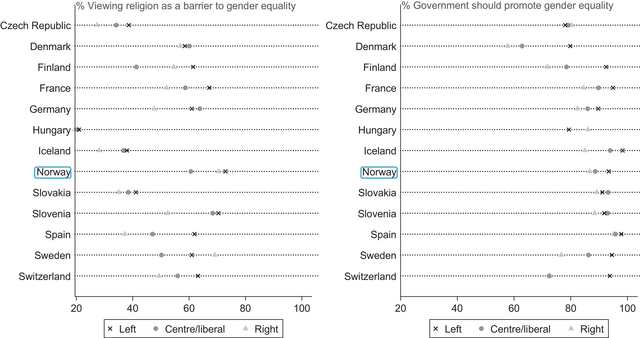

Figure 1 illustrates how typical or special Norway is in terms of people's ideas about gender equality. The left panel in further shows that most Norwegians believe religion is a barrier to gender equality. While this belief is slightly more widespread in Norway than in other countries, other countries show similar patterns. This suggests that Norwegians, both left‐ and right‐wing, may perceive a need for quotas in religious organizations, unlike a case such as Hungary where only 20 per cent of people share the concern. The right panel in Figure 1 shows that most Norwegians believe that the government should promote gender equality, regardless of their political views. Further, while Norway is ranked as one of the most gender equal societies in the world, Norwegians are similar to other Europeans when it comes to the promotion of gender equality.

Figure 1. Gender equality‐related views in European countries

Experimental design

We examine our hypotheses using a citizen‐elite paired survey experiment. This allows us to isolate the effects of gender quota arguments and of the areas of application, as well as the expected conditioning effects on these relations. Moreover, by using a survey experiment, we control for numerous items that may normally affect people's support for gender quotas. With this controlled setting, we can make stronger arguments for the causal nature of our findings.

Our experimental design had two treatments, each with four alternatives including a null treatment. In this between‐subjects design, respondents were asked to indicate their support for, or opposition to, a particular scenario in which the characteristics varied randomly across respondents. Each respondent received one version of the vignette. The treatments were randomized so that all combinations of the experiment were equally likely to be presented to the respondent.Footnote 2 The same design was presented to two different populations, namely, citizens and representatives. The wording of the vignette and treatment alternatives are presented in Box 1.

Treatment 1 addresses the potential effects of pro‐gender quota arguments on support for gender quotas. The dimensions referred to three arguments: the losing insights, the under‐use of talent (both utility arguments) and fairness arguments. In the fourth option, the vignette did not present any arguments to the respondent. Presenting only positive arguments in favour of gender quotas could have affected the respondent in such a way that they might express a more positive view of quotas overall, or in that they are irritated by the suggestion that gender quotas are socially desirable. For this reason, we aimed to balance the presentation of the argument by adding an opposite outlook on gender quotas. While this addition offered no argument, it highlighted that people can both be in favour of or against quotas, thus stripping the argument of a purely favourable expectation. Treatment 2 specified the area in which the quota would be applied. Three dimensions were related to religious institutions, politics and business.

The experiment was included in the 2018 survey wave (spring) of the Panel of Elected Representatives (PER) (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Broderstad and Helliesen2018) and the spring 2018 wave of the Norwegian Citizen Panel (NCP) (Norwegian Citizen Panel wave 12, 2018). Both surveys are web‐based panels for academic purposes. The PER targets the population of elected political representatives in Norway and had over 4,100 respondents in 2018, representing a response rate of approximately 38 per cent. The sample roughly reflects the population of representatives. Respondents include representatives from the national, county and municipal levels as well as representatives from the Sami parliament; the 38 per cent response rate is similar for each group of representatives. The NCP includes Norwegian citizens who were recruited via random sampling of the population. The sample used here is not fully reflective of the population overall, and weights have been applied to correct this bias in our analyses. In total, approximately 1,500 respondents of the NCP received the vignette. The Supporting Information Appendix provides further information about representativeness.

BOX 1 Factorial survey experiment design

In and around Norway, the use of quotas to ensure a gender balance in important boards or institutions is being discussed. |treatment 1

How strongly do you support or oppose gender quotas |treatment 2?

○ Strongly oppose

○ Oppose

○ Oppose somewhat

○ Neither support nor oppose

○ Support somewhat

○ Support

○ Strongly support

Varying treatment dimensions:

We expect that our results are conditional on personal characteristics and political ideology. The PER and NCP include identical questions that allow us to test these conditional effects. We use age, gender and ideology to condition argument effects. Ideology is measured using the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES), indicating the overall ideological stance of a party on an 11‐point index (0–10).Footnote 3

We analyze the data from the experiment using ordinary least squares. We estimate the predicted values for support for gender quotas under each of the treatment conditions. Support for quotas ranges from 0 to 6, where 0 means strong opposition and 6 means strong support; the treatment dimensions indicate whether the specific condition was presented to the respondent. As we are interested in the difference in the level of support under the different conditions, we require a test that identifies whether different point estimates, with each their own confidence intervals, are significantly different from each other. For this reason, we present our results as the predicted level of support with 84 per cent confidence intervals. This allows us to test whether the difference in support estimates is statistically significant at the 95 per cent confidence level (see e.g., Barnes & Beaulieu, Reference Barnes and Beaulieu2019; Julious, Reference Julious2004). Thus, a difference in predicted support for quotas is statistically significant at the 95 per cent confidence level when the 84 per cent confidence intervals do not overlap. We present the results in figures including predicted support and confidence intervals and report the precise estimates in the Supporting Information Appendix.

Results

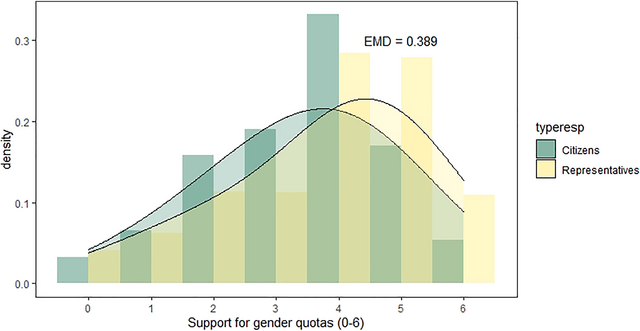

Before delving into the main results, we offer some context by showing an overall comparison of support for gender quotas of citizens and representatives. Figure 2 shows that their support is quite congruent; while representatives express a higher level of support, the Earth Movers Distance (EMD) (Lupu et al., Reference Lupu, Selios and Warner2017)Footnote 4 of 0.389 suggests it would require little effort to make the distributions identical.

Figure 2. Distribution of support for gender quotas for representatives and citizens

Support for gender quotas: Average effects of information exposure

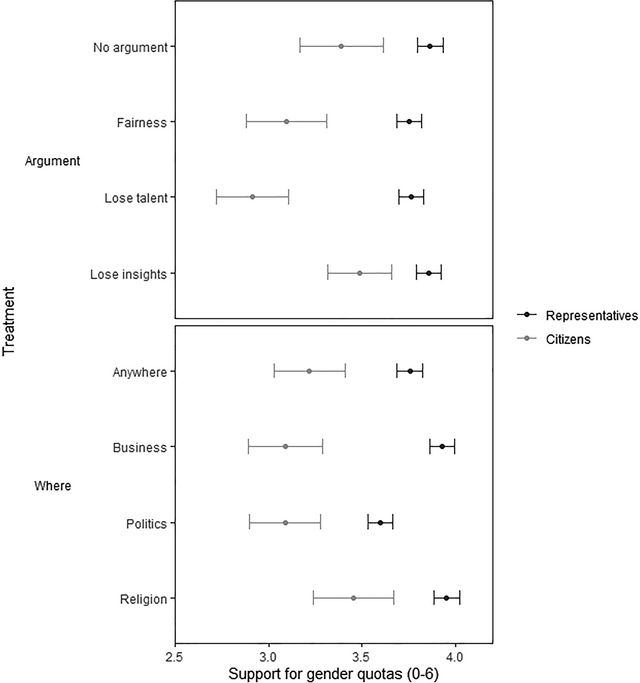

We now turn to the results from the survey experiments and focus initially on the average effects of the why and the where. Figure 3 presents the average effects from our experiment. The expressed support by the control group functions as the reference point.

Figure 3. Support for gender quotas; predicted average effects

We expected that social utility frames would encourage support more than a fairness frame (H1), and that especially the insights frame would be effective (H2). We have kept the two utility frames separate in the analysis so that we can test both hypothesis one and two at the same time. The results in Figure 3 (top panel) offer mixed support for these hypotheses. They show that the type of justification does not have a large effect on the level of support of either citizens or representatives. However, the argument that insights would be lost by not including women appears to generate somewhat more support than the other two justifications. This difference is statistically significant at the 95 per cent level among citizens, but not among representatives, providing some support for hypothesis 2 (H2). On the other hand, the justification pertaining to losing talent (the second utility frame) does not attract more support than the fairness frame. Our first expectation (H1) is therefore not supported. It is not a focus on utility per se, but support depends rather on the specific content of the utility frame. None of the frames differ statistically significantly from the null treatment suggesting that none of the arguments would affect support in and of itself.

The lower panel in Figure 3 gives the results for the effects of area of application. We expected that applying quotas to religious leadership would elicit more support than applying them to politics or business (H3). The results support this expectation only marginally. Among citizens, it does encourage the highest level of support, though confidence intervals overlap with those of all other attributes. Among representatives, the area of religion also elicits high levels of support, also compared to the baseline, though little more than the area of business. Applying gender quotas to the area of religious leadership does not encourage more support across the board.

The results do, however, provide support for the expectation that political representatives would support gender quotas in politics significantly less than in other areas (H6a), including the control. The proposal to apply quotas to politics attracts the least support among representatives, and significantly less than applying them to business or religion. Elected representatives seem more sceptical regarding gender quotas in politics – that is, the area they themselves work in. Citizens do not mirror this pattern.

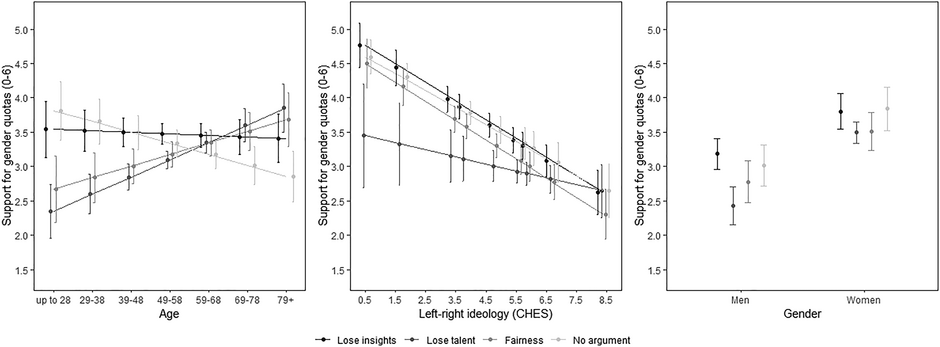

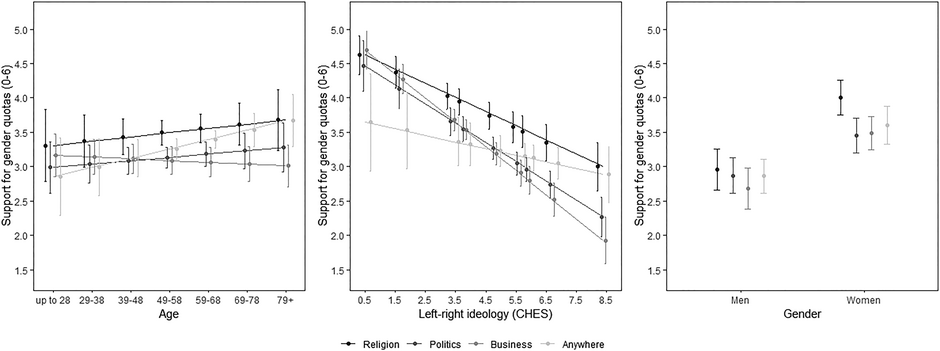

Conditional effects: Support for gender quotas and fixed views

We further expected that some groups in society would have more fixed views while others do not (yet) have such well‐developed opinions. Figure 4 presents the results of the interaction between the argument treatment and 1) age, 2) ideology and 3) gender of citizens. The left panel shows that support between different arguments varies more for younger citizens than for older citizens. In particular, the differences in support under the losing talent and losing insights frames are sizeable among younger citizens, while this difference is not statistically significant among older citizens. The difference is substantial for those under 50, as the losing talent argument appears to trigger opposition to quotas rather than the overall support that the losing insight argument and control encourage. It is further striking that when the older citizens were presented with a (any) pro‐quota argument they were more supportive of quotas than when no argument was presented – especially regarding the fairness and losing talent arguments. In alignment with our expectation (H4b), these results indicate that younger citizens are susceptible to different types of arguments and are more likely to be persuaded by one type of argument over the other. The losing insights argument encourages support across age groups.

Figure 4. Support for gender quotas; predicted effects of arguments among citizens, conditioned on age, ideology and gender

The middle panel, however, does not offer support for hypothesis 4a: Right‐wing citizens are overall less supportive of gender quotas, and arguments do not affect this position. The fairness argument encourages slightly less support than utility arguments as expected, but the difference is not statistically significant. Left‐wing citizens, surprisingly, are specifically less supportive of gender quotas when presented with the losing talent argument than the control. There is, however, wide variation associated with this argument: It seems that for some left‐wing citizens, support is undermined when the talent argument is presented, while others support quotas regardless of the specific argument.

The right panel further shows that men's level of support depends more on the type of argument than that of women. Especially the argument of losing insights can boost overall support somewhat, while the losing talent rather triggers opposition towards quotas, significantly compared to both the control and losing insights. Women seem to support quotas overall, regardless of any argument or whether there is an argument or not. These results provide support for our hypothesis 4c. Overall, Figure 4 lends support for our idea that some groups hold weaker positions on gender quotas, particularly younger and male citizens. We had not anticipated, however, that right‐wing citizens would be unaffected by any argument. Age, ideology, and gender do not seem to affect representatives as expected in hypothesis 4d. Tables A3, A4 and A5 of the Supporting Information Appendix report the full results.

Figure 5 presents the results of the interaction between the area of application and 1) age, 2) ideology and 3) gender of citizens. The left panel shows that there is little variation in support for quotas in different areas according to age. There is somewhat more support for quotas in religious leadership compared to other areas (but not the baseline) among older citizens (over 48), offering support for hypothesis 5b. The middle panel in Figure 5 shows that right‐wing citizens support quotas more in religious organizations than in politics or business. The right panel shows little variation among men regarding the area of application while women are more supportive of quotas in religion, providing support for Hypothesis 5c. People with fixed preferences may have more information on gender inequality and pre‐set beliefs, so that they view religious organizations as unequal and would like to correct this. Representatives are generally less supportive of applying quotas in politics, though age, ideology, and gender do not seem to affect them, aligning with hypothesis 5d. Tables A6, A7 and A8 of the Supporting Information Appendix provide the full results.

Figure 5. Support for gender quotas; predicted effects of area among citizens, conditioned on age, ideology and gender

Conditional effects: Support for gender quotas in ‘my backyard’

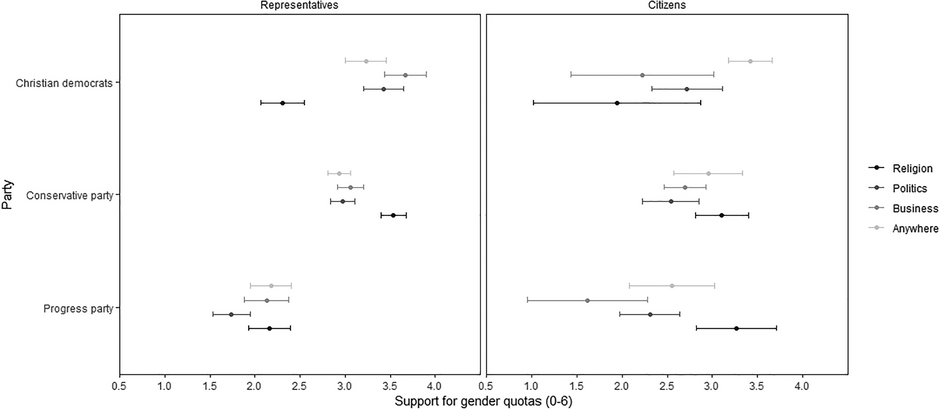

Lastly, we expected that people would be less supportive of gender quotas when they were proposed in the area in which people are active themselves. Specifically, we expected that elected representatives are less supportive of quotas in politics (H6a) for which we found support in Figure 2, that people affiliated with the Christian Democratic Party would express less support for quotas in religious organizations (H6b), and that those associated with the Progress and Conservative parties would be less excited by quotas in business (H6c).

Figure 6 presents the results for the effects of institutional application on support for gender quotas, conditioned on party affiliation. The results including all other parties are presented in Table A9 of the Supporting Information Appendix. Comparing support levels of Christian Democratic representatives across areas, Figure 6 shows that support for gender quotas in religious institutions is significantly lower than when other or no areas were mentioned. This difference is also substantial in that affiliates of the Christian Democratic Party tend to oppose quotas in religious institutions, while they tend to support quotas in other areas. Citizens affiliated with the party also support quotas in religion less, though differences are not statistically significant.Footnote 5 Further, among Christian Democrats, support for quotas in religion is lower than the support expressed by most other parties concerning this area. Overall, the findings largely support our expectation (H6b).

Figure 6. Support for gender quotas; predicted effects of area, conditioned on party

Figure 6 further shows that representatives of the Conservative Party and citizens of the Progress Party do not overall express more support if they were presented with the business area in the experiment. Hypothesis 6c is thus not supported by our findings. However, representatives of the Conservative Party and citizens of the Progress Party tend to express higher support for quotas when presented with the area of religion, which is not the case for all parties. Citizens of the Conservative Party tend to follow the same patterns, but the differences are not statistically significant. This aligns with the findings reported in Figure 5 where more right‐wing citizens support quotas in religious organizations more than in other areas. As the Progress Party supports restrictive migration policies and adopted stronger migration restrictions when the party shared executive power with the Conservative Party, we decided to investigate if support for gender quotas in religious organizations could be driven by a negative sentiment towards immigration or Muslims. After all, while the leadership of ‘mainstream’ churches are fairly gender‐equal in Norway, some smaller and specific churches, including Islam, are particularly exclusive of women in their leadership (as discussed in the case selection section).

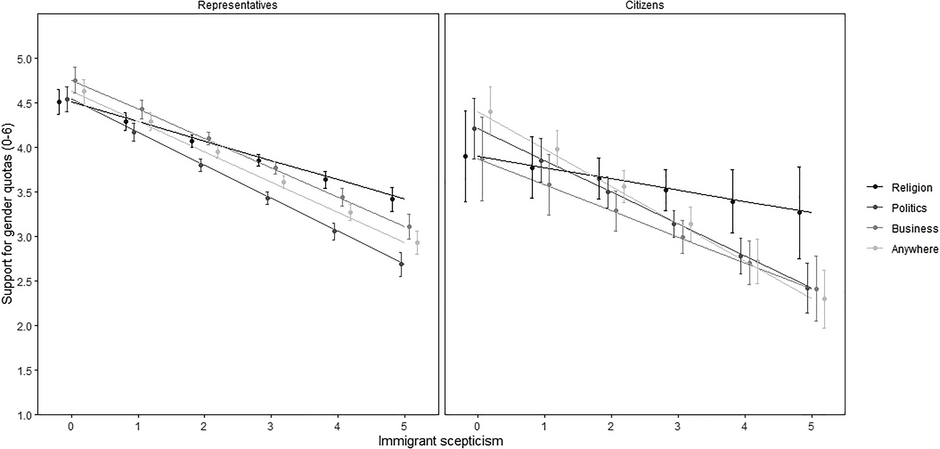

We therefore examine this possibility by interacting the area of application using a combined measure of two relevant attitudinal questions on immigration and Muslims.Footnote 6 Figure 7 shows the results of the interaction of institutional application with immigrant scepticism. The left panel gives the results for elected representatives, the right for citizens. It shows that more sceptical representatives support gender quotas when offered the religious institutions frame compared to other areas and the control group. Notably, the more immigrant‐sceptical representatives express support for quotas in religious organizations, while they tend to be more neutral or even oppose quotas in other areas. Such differences are not apparent among the less sceptical but are already visible from the ‘mid‐sceptical’ (a score of 3) onwards. These results are highly similar among citizens (right panel). Overall, these results indeed suggest that support for gender quotas in religious organizations may be driven by immigrant scepticism; perhaps even suggesting a desire to regulate the other, or outgroup, to conform to in‐group norms – even if these regulations are not necessarily supported in general terms.

Figure 7. Support for gender quotas; predicted effects of area, conditioned on immigrant scepticism

Discussion

This article is, to our knowledge, among the first studies to explore how attitudes are affected by both why and where gender quotas are applied. Governments across the globe have taken an active role in gendering leadership by introducing gender quotas in politics and other sectors of the society. However, while public opinion research has identified typical traits of quota supporters and opposers on a general level, such as gender and political affiliation, research has not fully addressed the diffusion and broadening aspects of current trends. As argued by Franceschet and Piscopo (Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2013) the growing popularity of quotas signals an emerging consensus that state power can be used to engineer equality. Still, more research is needed to understand the conditions under which state intervention is supported, and what the limits of reforms are.

Using a citizen‐elite paired experimental research design, we tested how information affects support for gender quotas. Previous research posits a strong link between gender, ideology and support for gender quotas, but has paid less attention to the effects of signalling that gender quotas may contribute to the achievement of a goal beyond that of fairness towards women. Others have demonstrated how critical actors use both justice and utility framing when advocating for reform (Seierstad, Reference Seierstad2016; Teigen, Reference Teigen2000), and international organizations use utility framing when advocating for gender equality. For instance, the United Nations claims that: ‘Gender equality is not only a fundamental human right, but a necessary foundation for a peaceful, prosperous and sustainable world’ (United Nations, 2015, SDG 5). Yet scholars have warned about the caveats of emphasizing ‘usefulness’ as a strategy to gather support for gender equality policies and platforms, as is implies that gender equality ‘must be defended with something else than its own value’ (Skjeie & Teigen, Reference Skjeie and Teigen2005, p. 192). Our results suggest that people consider the information they receive, and that framing is important, and that fairness arguments may not be sufficient when convincing people to support gender quotas. Moreover, different types of utility arguments can provoke opposite reactions in some sub‐groups.

A lot less studied is the idea that it may matter where gender quotas are applied. Different areas may trigger different reactions, and people are affected by their own background and information and views they possess. Areas viewed as more unequal can draw out more support; and it is easier to advocate to regulate other people's areas (not the respondent's own area). Our research emphasizes that even though some areas are not truly part of the discussion regarding gender quotas, support for them may be quite high. Debates on gender equality should thus be encouraged and developed, so that unexplored areas and possibilities become part of an active public debate.

Our findings indicate that women, overall, may not be convinced by a particular argument but generally favour gender quotas, while men may find the talent argument as unconvincing. They are more convinced by the importance of quotas when supplementary competences are emphasized. Women and older people tend to support quotas whatever the argument, right‐wing citizens tend to be unimpressed by any of them and overall do not support gender quotas very much. However, different arguments have a differential effect on younger citizens (not older citizens), and left‐wing citizens (not right‐wing). Also here, the talent frame receives the least support. One possible explanation for why this frame is less effective is that people do not believe that sufficient talent is lacking if women were not to be considered, that is, among men there is enough talent, even if the talent pool would be bigger when women are included. Our phrasing of the argument may not have sufficiently emphasized the additional talent that comes with promoting gender equality and its utility. At the same time, it is possible that people associate good leadership more with men than women, and so a traditional gender bias could be triggered by this argument. The insights argument emphasizes utility by accepting that men and women are different, offering the benefit of a perspective that men simply do not have, as well as maintaining a gender stereotype. Both utility arguments may thus tap into existing gender biases, but with different outcomes regarding support for gender quotas.

Applying gender quotas in religious leadership, further, seems to draw out higher support for quotas than elsewhere, especially among older, more right‐wing and female citizens. The consideration that this area is yet ‘untouched’ by similar policies and that the area is in some cases very unequal may lead some to support quotas more than they otherwise would. Left‐wing citizens are not particularly affected here. The support among right‐wing citizens, in combination with the finding that immigrant‐sceptic parties support quotas in religious leadership, led us to further look at this relationship. The consequent finding of evidence for a relationship between scepticism towards immigrants and support for quotas in religious leadership is also an important contribution. Pereira and Porto (Reference Pereira and Porto2020) have shown that public support for gender quotas in politics often relies on paternalistic views, and our findings also suggest the need for more nuanced and multilayered understanding of when and how gender equality matters for different types of populations. Most sub‐populations express more support for quotas in religious leadership in the context of Norway, but especially women and people on the right tend to express more support compared to the other areas. It is particularly noteworthy that people on the right are more supportive of quotas in this area even though they tend to be negative towards quotas overall. In line with our findings that people appear to express more support for quota regulation in other people's areas, we may be observing a desire to enforce gender equality norms on a religious out‐group, that is, non‐Western immigrants. This hypothesis would need to be tested more thoroughly, however.

Future research could explore more in‐depth the effects of different utility frames. Both in terms of understanding precisely what may be seen as a benefit or not, and by whom, the effects of different types of arguments could provide us with a better understanding of how people may be convinced by promoting gender equality through quotas. Moreover, scholars should explore how powerful the different arguments are regarding the promotion of (gender) equality through other means than quotas. Another important way forward would be to delve deeper into what aspects of gender equality appeals to those on the right; under what conditions would those that oppose gender quotas support action to achieve gender equality?

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Melody Ellis Valdini, Sveinung Arnesen, Jana Belschner, Joshi Devin, Annelise Fimreite, Elisabeth Ivarsflaten, Cecilia Josefsson, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions on the paper and survey experimental design. The authors would also like to acknowledge support from the “Money Talks” project (Grant nr. 233803), and financial support from the Trond Mohn Foundation and the University of Bergen (UiB) (Grant nr. 811309). The usual disclaimers apply.

Some of the data applied in the analysis in this publication are based on “Norwegian Citizen Panel wave 12, 2018”. The survey was financed by the UiB) and Trond Mohn Foundation. The data are provided by UiB, prepared and made available by Ideas2Evidence, and distributed by Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD). Neither UiB nor NSD are responsible for the analyses/interpretation of the data presented here.

Other data applied in the analysis in this publication are based on the “Panel of Elected Representatives wave 1, 2018”. The survey was financed by the UiB, and Trond Mohn Foundation. The data are provided by UiB, prepared and made available by Ideas2Evidence. UiB is not responsible for the analyses/interpretation of the data presented here.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix

Replication Data