Epidemiological research has begun unraveling the risk pathways leading from trauma exposures to pathological stress reactions and beyond to syndromic PTSD, focusing heavily on trauma-related features (e.g., type or severity) and differential reactivity of respondents during and following exposures. However, to date, studies have rarely examined differential liability to trauma exposure, even though this information may be both methodologically and clinically relevant (Jang et al., Reference Jang, Stein, Taylor, Asmundson and Livesley2003; Briggs-Gowan et al., Reference Briggs-Gowan, Carter and Clark2010; Amstadter et al., Reference Amstadter, Aggen, Knudsen, Reichborn-Kjennerud and Kendler2013; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Berenz and Aggen2014; Overstreet et al., Reference Overstreet, Berenz, Kendler, Dick and Amstadter2017).

We saw in Chapter 3 that traumas are highly prevalent, non-randomly distributed, begin early in life, and tend to pile up over time. Socio-demographic predictors of traumas vary substantially across trauma types, but generally include sex, age, economic status, and marital status. Because of variation in both the sign and strength of these predictors – with women having higher risk than men of sexual assault victimization, but men having higher risk of other traumas – no single high-risk trauma vulnerability profile emerged from our descriptive analyses in Chapter 3 apart from an apparently protective effect of being married.

We also showed in Chapter 3 that traumas are correlated over time; that the prior occurrence of one trauma is associated with increased risk of exposure to subsequent traumas. This is an important finding because it suggests that stable individual differences affect the risk of trauma exposure. If identified, the determinants of these individual differences might point to novel cross-cutting prevention targets that could help reduce future exposure (Howlett & Stein, Reference Howlett and Stein2016). Unfortunately, we were unaware of any of these subtle patterns when launching the WMH Initiative. As a result, survey questions were not developed to optimize study of the links across traumas. Many of the significant predictors of such links considered in previous research, most notably those of “event proneness” (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Jang, Taylor, Vernon and Livesley2002b), have involved intrinsic factors such as intelligence (Macklin et al., Reference Macklin, Metzger and Litz1998; Breslau et al., Reference Breslau, Lucia and Alvarado2006) or core personality dimensions such as dispositional negativity (Shackman et al., Reference Shackman, Stockbridge and Tillman2016), negative emotionality (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, Reiser, Pulkkinen and Caspi2002; Wolff & Baglivio, Reference Wolff and Baglivio2016), irritable/fearful temperament (Schmeck & Poustka, Reference Schmeck and Poustka2001; Helzer et al., Reference Helzer, Connor-Smith and Reed2009; Taskesen et al., Reference Taskesen, Demirkale, Taskesen, Okumus and Can2017), neuroticism (Kendler et al., Reference Kendler, Myers and Prescott2002, Reference Kendler, Gardner and Prescott2003; Jaksic et al., Reference Jaksic, Brajkovic, Ivezic, Topic and Jakovljevic2012), and impulsivity/extraversion (Netto et al., Reference Netto, Pereira and Nogueira2016; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Overstreet and Kendler2017). However, despite their considerable explanatory value, such constitutional factors are highly resistant to modification and thus have limited clinical utility at present.

As a result, we conducted post hoc analyses of WMH data to explore two other types of pre-trauma vulnerability that offer promising inroads to behavioral change. First, we investigated the possibility that childhood adversities (CAs) are associated with elevated risk of subsequent adult traumas. In the case of intergenerational transmission of family violence, prior research has shown that childhood physical or sexual abuse predicts greatly enhanced odds of adult intimate partner victimization (IPV) (Ehrensaft et al., Reference Ehrensaft, Cohen and Brown2003; Noll et al., Reference Noll, Horowitz, Bonanno, Trickett and Putnam2003; Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Noll, Putnam and Trickett2009; Black et al., Reference Black, Sussman and Unger2010; Cui et al., Reference Cui, Durtschi, Donnellan, Lorenz and Conger2010) and perpetration (Stith et al., Reference Stith, Smith, Penn, Ward and Tritt2004; Millett et al., Reference Millett, Kohl, Jonson-Reid, Drake and Petra2013). Numerous evidence-based primary interventions for these kinds of CAs have already been developed (McClennen et al., Reference McClennen, Keys and Dugan-Day2016), which employ a rich variety of psychosocial and cognitive-behavioral techniques suitable for ethnically and culturally diverse populations in various settings (Silverman et al., Reference Silverman, Ortiz and Viswesvaran2008; Dorsey et al., Reference Dorsey, McLaughlin and Kerns2017). It is conceivable that these kinds of interventions could be expanded based on evidence we uncover of other kinds of inter-temporal trauma clustering.

Second, we investigated the possibility that temporally primary lifetime mental disorders are associated with elevated risk of exposures to a wide range of subsequent adult traumas. Such associations have been documented in previous studies. Prior research has shown, for example, that bipolar disorder predicts greatly increased odds of both future violence-related traumas – violent crime victimization, crime perpetration (Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Lichtenstein, Grann, Goodwin and Langstrom2010), and sexual assault (Darves-Bornoz et al., Reference Darves-Bornoz, Lempérière, Degiovanni and Gaillard1995) – and accident-related traumas (Hiroeh et al., Reference Hiroeh, Appleby, Mortensen and Dunn2001). The risk reduction programs that already screen for and treat emerging behavioral disorders before they progress to serious criminal or accident-related sequelae of this sort (Lam et al., Reference Lam, Hayward, Watkins, Wright and Sham2005) might accommodate prevention arms for potential downstream traumas. However, a clearer characterization of the extent to which DSM-IV disorders predict subsequent trauma exposure is needed for optimal targeting of pre-trauma risk factors.

Methods

Using the same sample and analytical framework as in Chapter 3, we expanded the models developed in that chapter to include predictors for CAs and temporally prior (to index traumas) lifetime mental disorders. As discussed in detail in Chapter 10, the WMH surveys assessed 12 dichotomously measured CAs. These included three types of interpersonal loss (parent death, parent divorce, and other loss of contact with parents or caregivers), four types of parent maladjustment (psychopathology, substance abuse, criminality, and family violence), three types of respondent maltreatment (physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect), respondent serious physical illness, and family economic adversity. Parent death and divorce were assessed only for biological parents, but other loss of contact with caregivers included any disruption of a caregiving relationship for six months or longer. Respondents born to an unwed mother or who were adopted at birth were not coded as experiencing the loss of their fathers or biological parents, respectively.

Physical abuse of the respondent by caregivers was assessed with a modified version of the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) (Straus, Reference Straus1979) and with an item from the trauma section of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (Kessler & Üstün, Reference Kessler and Üstün2004). Sexual abuse of the respondent by caregivers or other family members was assessed with questions from the CIDI regarding sexual assault, attempted rape, and rape, which asked whether these traumas were one-time vs. recurrent experiences. Neglect was assessed with questions used in studies of child welfare that assessed the frequency of having inadequate food, clothing, medical care, or supervision, and being required to do age-inappropriate chores (Courtney et al., Reference Courtney, Piliavin, Grogan-Kaylor and Nesmith1998).

Parent criminality was assessed with questions about whether a parent engaged in criminal activities or was ever arrested or sent to prison. Parent psychopathology (major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or suicide attempt) and parent substance abuse were assessed with a revised version of the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria Interview (Endicott et al., Reference Endicott, Andreasen and Spitzer1978; Kendler et al., Reference Kendler, Silberg and Neale1991). Family violence was assessed with the modified CTS and a question in the trauma section of the CIDI about parent violence. Economic adversity was assessed with questions about whether the respondent's family received welfare or other government assistance or had insufficient money for necessities. Physical illness was assessed with a standard chronic conditions checklist.

It should be noted that since several of the CAs considered here were either themselves listed among the individual trauma types assessed in Chapter 3 (e.g., childhood physical abuse, witnessing family violence during childhood, childhood physical illness) or included as components of these trauma types (e.g., sexual assault victimization, unexpected death of a loved one), certain of the analyses planned here naturally echoed those in Chapter 3 that traced prior traumas to subsequent ones. In cases of direct overlap, we removed the CA questions from the CA battery, treating them as traumas rather than childhood adversities. Although this resulted in the complete elimination of the CA sexual abuse category and the narrowing of the CA physical abuse category in some cases, most of the study CAs were unaffected.

Consistent with final models generated for Chapter 10, the CA models predicted trauma exposure controlling for socio-demographics and prior trauma measures along with methodological controls for survey and person-year. We began with a series of models examining each CA separately along with these controls and then estimated models that included a separate predictor variable for each of the CAs followed by multivariate models that evaluated the joint predictive effects of all CAs. We distinguished between CAs in a highly inter-correlated set that we referred to in previous reports as indicators of maladaptive family functioning (MFF) CAs (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, McLaughlin and Green2010). The logic of these models is described in Chapter 10. The MFF CAs included parent mental illness, parent substance abuse, parent criminality, family violence, physical and sexual abuse of the respondent, and neglect of the respondent.

The final CA models were then expanded to include information about lifetime occurrence of 14 DSM-IV Axis I disorders that had initial onsets prior to the respondent's history of criminality, family violence, physical and sexual abuse, these disorders were assessed with the CIDI. The disorders included two mood disorders (major depressive disorder/dysthymic disorder and broadly defined bipolar disorder [bipolar I and II and sub-threshold bipolar disorder, defined using criteria described elsewhere]) (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Akiskal and Angst2006), six anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder and/or agoraphobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, separation anxiety disorder, social phobia, and specific phobia), four disruptive behavior disorders (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, and oppositional-defiant disorder), and two substance disorders (alcohol and drug abuse with or without dependence). As noted in Chapter 2, age-of-onset of each disorder was assessed using probing techniques shown experimentally to improve recall accuracy (Knäuper et al., Reference 82Knäuper, Cannell, Schwarz, Bruce and Kessler1999), enabling us to determine whether respondents had a history of each disorder prior to exposure to the index trauma.

Associations of Childhood Adversities with Subsequent Traumas

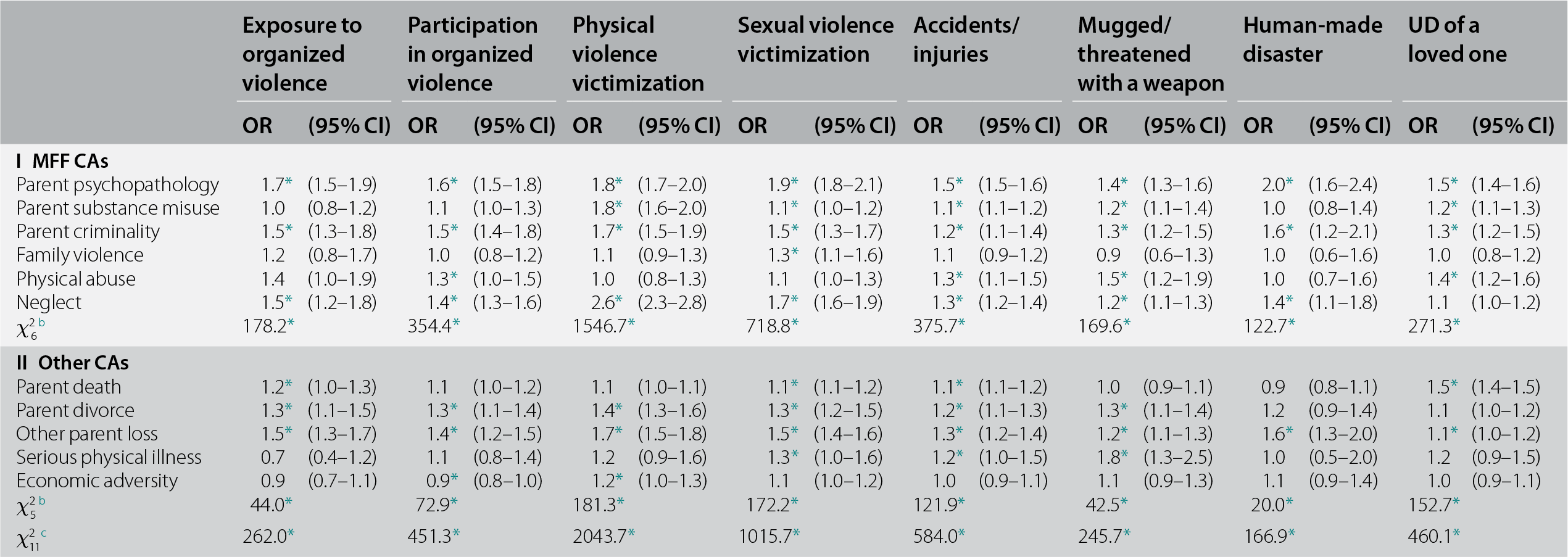

We examined predictors of trauma exposure for each of the 29 trauma types both separately and pooled across the trauma factors described in Chapter 3. As in that chapter, we also focus here primarily on the pooled models as well as on models for each of the three individual cross-loading traumas. However, trauma-specific models are briefly mentioned and are presented in the appendix tables. We began with inspection of bivariate associations in which only one CA was considered at a time to predict the subsequent occurrence of each of the 29 trauma types controlling for respondent sex, person-year, and age at interview along with dummy controls for survey. About two-thirds (68%) of these 319 (11 CAs predicting each of 29 traumas) ORs were greater than 1.0 and significant at the 0.05 level (two-sided tests). However, given that the CAs were strongly inter-correlated, much smaller proportions of ORs remained significant in multivariate models. The 11 CAs were significant as a set in predicting subsequent exposures to traumas in all five broad trauma groups as well as the three cross-loading traumas (χ211 = 166.9–2,043.7, p < 0.001) (see Table 4.1). MFF CAs consistently were stronger predictors (χ26 = 122.7–1,546.7, p < 0.001) than other CAs (χ25 = 20.0–181.3, p = 0.001 to <0.001).

Table 4.1 Multivariate associations of CAs with the subsequent onset of traumas aggregated into categories in 26 WMH surveysa

| Exposure to organized violence | Participation in organized violence | Physical violence victimization | Sexual violence victimization | Accidents/injuries | Mugged/threatened with a weapon | Human-made disaster | UD of a loved one | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| I MFF CAs | ||||||||||||||||

| Parent psychopathology | 1.7* | (1.5–1.9) | 1.6* | (1.5–1.8) | 1.8* | (1.7–2.0) | 1.9* | (1.8–2.1) | 1.5* | (1.5–1.6) | 1.4* | (1.3–1.6) | 2.0* | (1.6–2.4) | 1.5* | (1.4–1.6) |

| Parent substance misuse | 1.0 | (0.8–1.2) | 1.1 | (1.0–1.3) | 1.8* | (1.6–2.0) | 1.1* | (1.0–1.2) | 1.1* | (1.1–1.2) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.4) | 1.0 | (0.8–1.4) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.3) |

| Parent criminality | 1.5* | (1.3–1.8) | 1.5* | (1.4–1.8) | 1.7* | (1.5–1.9) | 1.5* | (1.3–1.7) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.4) | 1.3* | (1.2–1.5) | 1.6* | (1.2–2.1) | 1.3* | (1.2–1.5) |

| Family violence | 1.2 | (0.8–1.7) | 1.0 | (0.8–1.2) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.3) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.6) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.2) | 0.9 | (0.6–1.3) | 1.0 | (0.6–1.6) | 1.0 | (0.8–1.2) |

| Physical abuse | 1.4 | (1.0–1.9) | 1.3* | (1.0–1.5) | 1.0 | (0.8–1.3) | 1.1 | (1.0–1.3) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.5) | 1.5* | (1.2–1.9) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.6) | 1.4* | (1.2–1.6) |

| Neglect | 1.5* | (1.2–1.8) | 1.4* | (1.3–1.6) | 2.6* | (2.3–2.8) | 1.7* | (1.6–1.9) | 1.3* | (1.2–1.4) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.3) | 1.4* | (1.1–1.8) | 1.1 | (1.0–1.2) |

| χ26 b | 178.2* | 354.4* | 1546.7* | 718.8* | 375.7* | 169.6* | 122.7* | 271.3* | ||||||||

| II Other CAs | ||||||||||||||||

| Parent death | 1.2* | (1.0–1.3) | 1.1 | (1.0–1.2) | 1.1 | (1.0–1.1) | 1.1* | (1.1–1.2) | 1.1* | (1.1–1.2) | 1.0 | (0.9–1.1) | 0.9 | (0.8–1.1) | 1.5* | (1.4–1.5) |

| Parent divorce | 1.3* | (1.1–1.5) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.4) | 1.4* | (1.3–1.6) | 1.3* | (1.2–1.5) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.3) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.4) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.4) | 1.1 | (1.0–1.2) |

| Other parent loss | 1.5* | (1.3–1.7) | 1.4* | (1.2–1.5) | 1.7* | (1.5–1.8) | 1.5* | (1.4–1.6) | 1.3* | (1.2–1.4) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.3) | 1.6* | (1.3–2.0) | 1.1* | (1.0–1.2) |

| Serious physical illness | 0.7 | (0.4–1.2) | 1.1 | (0.8–1.4) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.6) | 1.3* | (1.0–1.6) | 1.2* | (1.0–1.5) | 1.8* | (1.3–2.5) | 1.0 | (0.5–2.0) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.5) |

| Economic adversity | 0.9 | (0.7–1.1) | 0.9* | (0.8–1.0) | 1.2* | (1.0–1.3) | 1.1 | (1.0–1.2) | 1.0 | (0.9–1.1) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.3) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.4) | 1.0 | (0.9–1.1) |

| χ25 b | 44.0* | 72.9* | 181.3* | 172.2* | 121.9* | 42.5* | 20.0* | 152.7* | ||||||||

| χ211 c | 262.0* | 451.3* | 2043.7* | 1015.7* | 584.0* | 245.7* | 166.9* | 460.1* | ||||||||

* Significant at the 0.05 level, two-sided test.

a Based on a series of multivariate survival models with person-year the unit of analysis and a logistic link function in which information about prior CAs was used to predict the subsequent first onset of traumas. Controls were included for person-year, sex, age-at-interview, and survey.

b The joint significance of the set of ORs for CAs in the group.

c The joint significance of all CAs in the model.

Inspection of ORs in the aggregated models showed that the most consistent predictors, significant in all models, were parent mental illness (OR = 1.4–2.0), parent criminality (OR = 1.2–1.7), and other parent loss (OR = 1.1–1.6). The extent to which controls for exogenous associations among predictors influenced these estimates is indicated by the fact that the bivariate associations of these three predictors with the outcomes were in the range OR = 1.6–2.7 for parent mental illness, OR = 1.4–3.1 for parent criminality, and OR = 1.2–2.1 for other parent loss. The multivariate ORs were more strongly elevated and consistently significant for MFF CAs (81% of ORs significant, with a median of 1.8 and inter-quartile range [IQR] of 1.5–2.3) than other CAs (52% of ORs significant, with a median of 1.3 and IQR of 1.1–1.5). Similar patterns held in bivariate models, where median (IQR) ORs predicting each of the 29 traumas was highest for parent mental illness [OR = 2.2 (1.6–2.5)] followed by neglect [OR = 2.0 (1.7–2.8)] and parent criminality [OR = 2.0 (1.6–2.5)]. The other MFF CAs and other parent loss had lower bivariate ORs [other MFF CAs OR = 1.5 (1.4–2.1); other parent loss OR = 1.7 (1.4–1.9)], whereas the remaining CAs (parent death, parent divorce, serious physical illness, economic adversity) had much lower bivariate ORs [OR = 1.2 (1.1–1.5)].

As expected, the CAs most strongly predicted trauma exposures in the domains of physical and sexual violence victimization. Parent neglect (OR = 1.7–2.6) and parent mental illness (OR = 1.8–1.9) consistently had the highest ORs in those models followed by parent substance abuse (OR = 1.8 predicting physical violence victimization but only OR = 1.1 predicting sexual violence victimization) and other parent loss (OR = 1.7–1.5). Disaggregation showed that the traumas within the broad groups involving physical and sexual violence victimization most strongly predicted by the above CAs were being raped (OR = 2.4–3.9) and witnessing physical fights between parents at home (OR = 1.8–4.8) in bivariate models. These CAs also strongly predicted subsequently being beaten by a spouse or romantic partner (OR = 1.9–3.2 in bivariate models), beaten up by someone else (OR = 1.9–3.0), mugged (OR = 1.3–1.6), and all other traumas in the sexual assault victimization group (OR = 1.3–2.6). Childhood neglect typically had the highest OR in predicting these outcomes, followed by parent mental illness and parent criminality.

Associations of Temporally Prior DSM-IV/CIDI Disorders with Subsequent Traumas

We next considered associations of temporally primary lifetime mental disorders with subsequent first onset of traumas. We used the same modeling approach as in the analysis of CAs. We began with bivariate models for the association of each temporally primary lifetime mental disorders predicting subsequent first onset of each trauma, controlling for type and number of CAs, respondent sex, person-year, age at interview, and dummy controls for survey. The vast majority (96.3%) of these 406 (14 mental disorders predicting each of 29 traumas) ORs were greater than 1.0% and 78.5% were both greater than 1.0 and statistically significant at the 0.05 level (two-sided tests). This number did not decrease greatly in multivariate models, where 74.1% of ORs were greater than 1.0 and were also statistically significant.

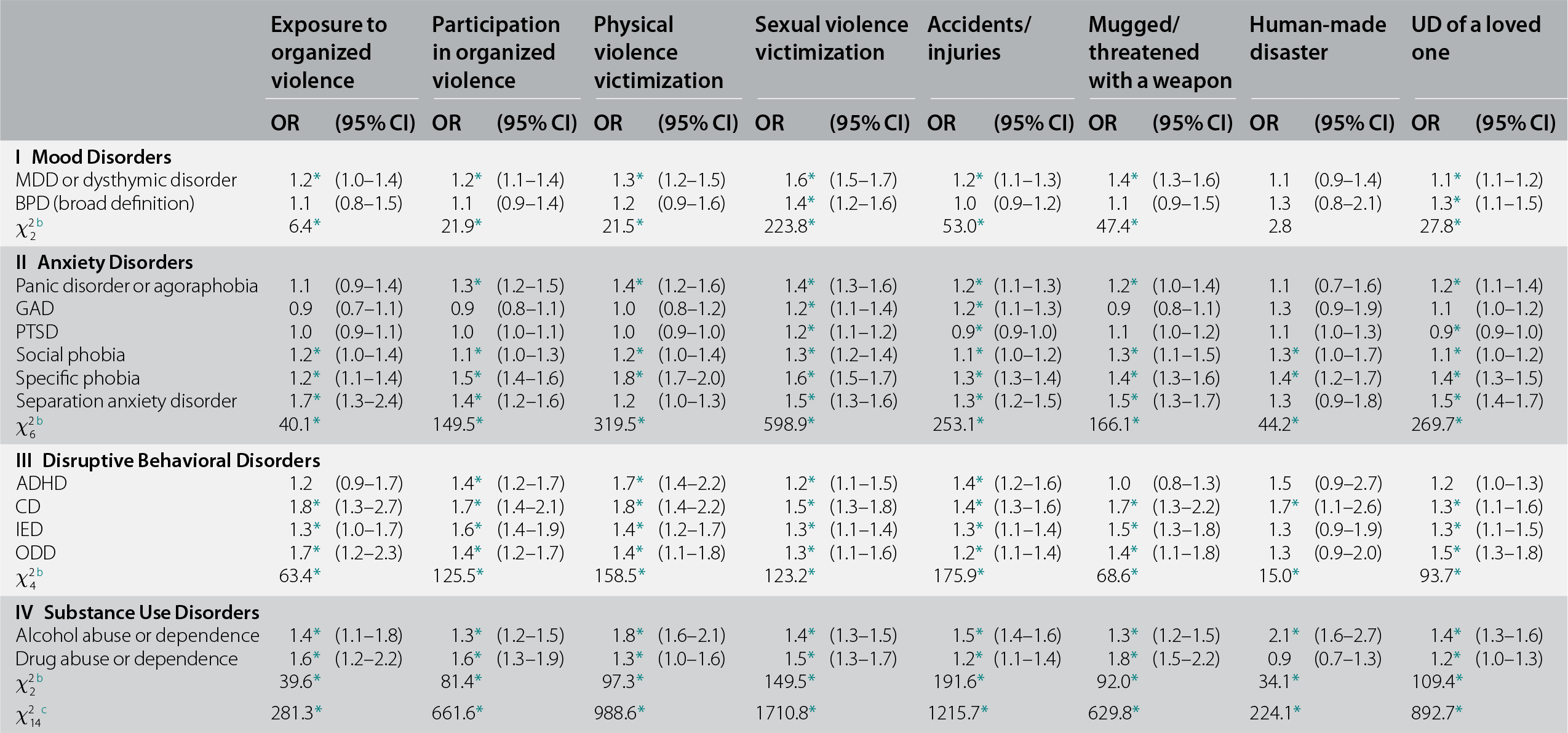

In multivariate models, the 14 disorders were significant as a set in predicting subsequent exposures to traumas in all five broad trauma groups as well as in the three cross-loading traumas (χ214 = 224.1–1,710.8, p < 0.001) (see Table 4.2). Mood disorders were significant in seven of eight models (χ22 = 6.4–223.8, p = 0.040–<0.001), and each other class of disorders was significant in all eight models (anxiety disorders χ26 = 40.1–598.9, p < 0.001; disruptive behavior disorders χ24 =15.0–158.5, p = 0.005–<0.001; substance disorders χ22 = 34.1–191.6, p < 0.001).

Table 4.2 Multivariate associations of lifetime DSM-IV/CIDI disorders with the subsequent onset of traumas aggregated into categories in 26 WMH surveysa

| Exposure to organized violence | Participation in organized violence | Physical violence victimization | Sexual violence victimization | Accidents/injuries | Mugged/threatened with a weapon | Human-made disaster | UD of a loved one | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| I Mood Disorders | ||||||||||||||||

| MDD or dysthymic disorder | 1.2* | (1.0–1.4) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.4) | 1.3* | (1.2–1.5) | 1.6* | (1.5–1.7) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.3) | 1.4* | (1.3–1.6) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.4) | 1.1* | (1.1–1.2) |

| BPD (broad definition) | 1.1 | (0.8–1.5) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.4) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.6) | 1.4* | (1.2–1.6) | 1.0 | (0.9–1.2) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.5) | 1.3 | (0.8–2.1) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.5) |

| χ22 b | 6.4* | 21.9* | 21.5* | 223.8* | 53.0* | 47.4* | 2.8 | 27.8* | ||||||||

| II Anxiety Disorders | ||||||||||||||||

| Panic disorder or agoraphobia | 1.1 | (0.9–1.4) | 1.3* | (1.2–1.5) | 1.4* | (1.2–1.6) | 1.4* | (1.3–1.6) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.3) | 1.2* | (1.0–1.4) | 1.1 | (0.7–1.6) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.4) |

| GAD | 0.9 | (0.7–1.1) | 0.9 | (0.8–1.1) | 1.0 | (0.8–1.2) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.4) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.3) | 0.9 | (0.8–1.1) | 1.3 | (0.9–1.9) | 1.1 | (1.0–1.2) |

| PTSD | 1.0 | (0.9–1.1) | 1.0 | (1.0–1.1) | 1.0 | (0.9–1.0) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.2) | 0.9* | (0.9-1.0) | 1.1 | (1.0–1.2) | 1.1 | (1.0–1.3) | 0.9* | (0.9–1.0) |

| Social phobia | 1.2* | (1.0–1.4) | 1.1* | (1.0–1.3) | 1.2* | (1.0–1.4) | 1.3* | (1.2–1.4) | 1.1* | (1.0–1.2) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.5) | 1.3* | (1.0–1.7) | 1.1* | (1.0–1.2) |

| Specific phobia | 1.2* | (1.1–1.4) | 1.5* | (1.4–1.6) | 1.8* | (1.7–2.0) | 1.6* | (1.5–1.7) | 1.3* | (1.3–1.4) | 1.4* | (1.3–1.6) | 1.4* | (1.2–1.7) | 1.4* | (1.3–1.5) |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 1.7* | (1.3–2.4) | 1.4* | (1.2–1.6) | 1.2 | (1.0–1.3) | 1.5* | (1.3–1.6) | 1.3* | (1.2–1.5) | 1.5* | (1.3–1.7) | 1.3 | (0.9–1.8) | 1.5* | (1.4–1.7) |

| χ26 b | 40.1* | 149.5* | 319.5* | 598.9* | 253.1* | 166.1* | 44.2* | 269.7* | ||||||||

| III Disruptive Behavioral Disorders | ||||||||||||||||

| ADHD | 1.2 | (0.9–1.7) | 1.4* | (1.2–1.7) | 1.7* | (1.4–2.2) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.5) | 1.4* | (1.2–1.6) | 1.0 | (0.8–1.3) | 1.5 | (0.9–2.7) | 1.2 | (1.0–1.3) |

| CD | 1.8* | (1.3–2.7) | 1.7* | (1.4–2.1) | 1.8* | (1.4–2.2) | 1.5* | (1.3–1.8) | 1.4* | (1.3–1.6) | 1.7* | (1.3–2.2) | 1.7* | (1.1–2.6) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.6) |

| IED | 1.3* | (1.0–1.7) | 1.6* | (1.4–1.9) | 1.4* | (1.2–1.7) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.4) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.4) | 1.5* | (1.3–1.8) | 1.3 | (0.9–1.9) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.5) |

| ODD | 1.7* | (1.2–2.3) | 1.4* | (1.2–1.7) | 1.4* | (1.1–1.8) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.6) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.4) | 1.4* | (1.1–1.8) | 1.3 | (0.9–2.0) | 1.5* | (1.3–1.8) |

| χ24 b | 63.4* | 125.5* | 158.5* | 123.2* | 175.9* | 68.6* | 15.0* | 93.7* | ||||||||

| IV Substance Use Disorders | ||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 1.4* | (1.1–1.8) | 1.3* | (1.2–1.5) | 1.8* | (1.6–2.1) | 1.4* | (1.3–1.5) | 1.5* | (1.4–1.6) | 1.3* | (1.2–1.5) | 2.1* | (1.6–2.7) | 1.4* | (1.3–1.6) |

| Drug abuse or dependence | 1.6* | (1.2–2.2) | 1.6* | (1.3–1.9) | 1.3* | (1.0–1.6) | 1.5* | (1.3–1.7) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.4) | 1.8* | (1.5–2.2) | 0.9 | (0.7–1.3) | 1.2* | (1.0–1.3) |

| χ22 b | 39.6* | 81.4* | 97.3* | 149.5* | 191.6* | 92.0* | 34.1* | 109.4* | ||||||||

| χ214 c | 281.3* | 661.6* | 988.6* | 1710.8* | 1215.7* | 629.8* | 224.1* | 892.7* | ||||||||

* Significant at the 0.05 level, two-sided test.

a Based on a series of multivariate survival models with person-year the unit of analysis and a logistic link function in which information about prior lifetime mental disorders was used to predict the subsequent first onset of traumas. Controls were included for person-year, sex, age-at-interview, survey, and CAs.

b The joint significance of the set of ORs for mental disorders in the group.

c The joint significance of all mental disorders in the model.

Within the mood disorders, major depression was more consistently significant than bipolar spectrum disorder (in seven vs. two models, with ORs = 1.1–1.6 vs. in two models with OR = 1.3–1.4). However, this difference reflected the stronger comorbidities of BP spectrum disorder than major depression with the other disorders in the set. This can be seen in the bivariate models wherein we considered only one mental disorder at a time, the median (IQR) ORs across all 29 traumas was higher for BP spectrum disorder [OR = 2.2 (1.6–2.9)] than major depression [OR = 1.7 (1.4–2.6)]. The traumas predicted most strongly by BP spectrum disorder in bivariate models included being kidnapped (OR = 5.1), stalked (OR = 4.6), beaten by a romantic partner (OR = 4.0), and beaten up by someone else (OR = 3.5). ORs for all these outcomes were also elevated but lower for major depression. The only case where major depression had a substantially higher OR than BP spectrum disorders in bivariate models was in predicting purposefully injuring, torturing, or killing someone (OR = 3.9 for major depression, OR = 2.7 for BP spectrum disorder).

Within the anxiety disorders, social phobia and specific phobia were the most consistently significant predictors in multivariate models, as they were significant in all models. They had ORs in the range OR = 1.1–1.3 for specific phobia and OR = 1.2–1.8 for social phobia. As with mood disorders, though, these results reflect differences in comorbidities among the disorders. The bivariate models tell a somewhat different story, showing that separation anxiety disorder (SAD) had the strongest median (IQR) OR across the 29 traumas [OR = 2.1 (2.0–2.9)] followed by panic/agoraphobia [OR = 1.9 (1.6–2.3)], generalized anxiety disorder [OR = 1.8 (1.4–2.4)], social phobia [OR = 1.8 (1.4–2.4)], and specific phobia [OR = 1.8 (1.6–2.2). Interestingly, PTSD had the lowest median OR of all anxiety disorders [OR = 1.2 (1.0–1.4)]. The traumas predicted most strongly by SAD in bivariate models included purposefully injured/killed someone (OR = 7.9), accidentally caused serious injury/death (OR = 3.8), and stalked (OR = 3.8). The traumas predicted most strongly by all anxiety disorders other than PTSD were those involving sexual assault victimization (OR = 2.2–3.3). PTSD, in comparison, consistently had the weakest predictive associations of all anxiety disorders across the traumas [OR = 1.2 (1.0–1.4)].

All disruptive behavior disorders other than ADHD were consistently significant predictors in multivariate models (OR = 1.2–1.8). ADHD, in comparison, was significant in half the multivariate models with significant ORs of 1.2–1.7. Bivariate models show, in comparison, conduct disorder (CD) and oppositional-defiant disorder (ODD) had the highest median (IQR) ORs [CD OR = 3.1 (2.6–4.0); ODD OR = 3.1 (2.5–3.6)] followed by ADHD [OR = 2.7 (2.3–3.2)] and IED [OR = 2.2 (1.7–2.7)]. The traumas most strongly predicted by CD and ODD were in the domains of participation in organized violence (accidentally and purposefully causing serious injury or death OR = 7.2–9.9), physical violence victimization (beaten up by someone else OR = 4.4–6.5), and especially sexual assault victimization (raped OR = 4.5–4.7, stalked OR = 4.1–3.6, beaten up by romantic partner OR = 6.9–4.9). The traumas most strongly predicted by ADHD and IED were similar, but with lower ORs than those for CD and ODD. It is noteworthy, given prominent discussions to the contrary in the clinical ADHD literature (Garner et al., Reference Garner, Gentry and Welburn2014; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Quinn and Hur2017), that the OR of ADHD predicting automobile accidents (OR = 2.3) was in line with ORs for other disruptive behavior disorders (OR = 2.1–2.7). With the exceptions of BP spectrum disorder and substance use disorder (OR = 1.8–2.2), disruptive behavior disorders had higher bivariate ORs predicting automobile accidents than did any other mental disorders (OR = 1.0–1.6).

Both substance use disorders were consistently significant predictors of traumas in multivariate models (OR = 1.2–2.1). Both alcohol and drug use disorders also had significant elevated ORs with 86.2%–82.8% of the 29 individual traumas in bivariate models, with median (IQR) values somewhat higher for drug use disorders [OR = 2.4 (1.8–2.9)] than alcohol use disorders [OR = 1.7 (1.6–2.5)]. The highest bivariate ORs are with accidentally and purposefully injuring or killing someone (OR = 2.9–6.5), being kidnapped (OR = 3.6–4.7), being beaten by a romantic partner (OR = 5.1–7.0), and being stalked (OR = 2.7–4.0), in each case with drug use disorder having a higher OR than alcohol use disorder.

The traumas most strongly predicted by temporally primary mental disorders were those involving sexual assault victimization, both in bivariate models [OR = 2.6 (2.3–2.9)] and in multivariate models (OR = 1.2–1.6). Traumas involving physical violence victimization were next most strongly predicted [OR = 2.3 (1.9–2.7) in bivariate models; OR = 1.2–1.8 in multivariate models]. The traumas least strongly predicted by prior mental disorders were unexpected death of a loved one [OR = 1.7 (1.5–2.9) in bivariate models; OR = 1.1–1.5 in multivariate models] and accidents/injuries [OR = 1.8 (1.7–1.9) in bivariate models; 1.1–1.5 in multivariate models].

Discussion

In this chapter, we evaluated two potentially important classes of predictors of trauma exposure, childhood adversities and prior mental disorders, both of which are highly prevalent, heavily paired with particular trauma trajectories in the clinical literature, and associated with evidence-based treatment protocols that might be leveraged for prevention of subsequent trauma exposure (Howlett & Stein, Reference Howlett and Stein2016). Our finding that CAs most strongly predict traumas in the domains of physical and sexual violence victimization is consistent with a large observational literature linking child maltreatment to heightened risk of subsequent adult relationship violence (Coid et al., Reference Coid, Petruckevitch and Feder2001; Ehrensaft et al., Reference Ehrensaft, Cohen and Brown2003; Noll et al., Reference Noll, Horowitz, Bonanno, Trickett and Putnam2003; Gover et al., Reference Gover, Kaukinen and Fox2008; Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Noll, Putnam and Trickett2009; Black et al., Reference Black, Sussman and Unger2010; Cui et al., Reference Cui, Durtschi, Donnellan, Lorenz and Conger2010; Conley et al., Reference Conley, Overstreet and Hawn2017; Lang & Gartstein, Reference Lang and Gartstein2017) and with similar findings in studies of child maltreatment among representative U.S. samples (Finkelhor et al., Reference Finkelhor, Ormrod and Turner2007; Cuevas et al., Reference 81Cuevas, Finkelhor, Ormrod and Turner2009).

Our finding that childhood neglect is the strongest predictor of trauma risk is surprising, given the strong focus on child maltreatment in contemporary epidemiological research relative to neglect (Kanai et al., Reference Kanai, Takaesu and Nakai2016; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Menon, Shorey, Le and Temple2017; Naughton et al., Reference Naughton, Cowley and Tempest2017). Although we were unable to find other population-based comparators, the notion that early neglect may lead to subsequent trauma is indirectly consistent with strong neurobiological evidence linking deprivation to aberrant neurodevelopment (Calem et al., Reference Calem, Bromis, McGuire, Morgan and Kempton2017) associated with a cascade of persistent cognitive deficits (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2012; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan and Nelson2017) and incident psychopathology (Busso et al., Reference Busso, McLaughlin and Brueck2017; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, McLaughlin, Hamilton and Keyes2017).

Somewhat unexpected as well was the comparatively weak association of childhood physical abuse with overall trauma liability (with only 55.2% of its bivariate associations with traumas significant positives) vs. those for neglect (with 96.6% of bivariate associations with traumas significant positives) and parent maladjustment (with 86.2%–93.1% significant positives). Altogether, such findings hint that trauma proneness is mediated both by early neglect, which may reflect environmental influences on brain hardwiring during sensitive developmental periods and by parent maladjustment, which may reflect heritable influences on self-selection into hazardous situations (Jang et al., Reference Jang, Stein, Taylor, Asmundson and Livesley2003; Ogle et al., Reference Ogle, Rubin and Siegler2014) and/or the durable effects of vicissitudes in early attachment (Ogden, Reference Ogden2016). Our robust finding from Chapter 3 of lower trauma exposure among married respondents perhaps assumes better definition in this context; although we initially attributed the result to marriage-related benefits of an instrumental or material sort (e.g., home during evenings, fewer bar fights, greater income), the more qualitative, relational aspects of marriage may be more pertinent (e.g., caring, companionship, belonging). Conversely, being unmarried may serve less as an index of chronic exposures to situational hazards and more as a potent marker of disturbed early attachment and entrenched psychopathology (Breslau et al., Reference Breslau, Miller and Jin2011).

Psychopathology is generally considered an outcome of trauma exposure instead of a predictor, limiting comparators for our results in the prior literature. Nonetheless, our finding that preexisting behavior disorders are associated with elevated risk of most traumas is consistent with data from several longitudinal cohort studies (Koenen et al., Reference Koenen, Harley and Lyons2002, Reference Koenen, Moffitt, Poulton, Martin and Caspi2007; Breslau et al., Reference Breslau, Lucia and Alvarado2006; Storr et al., Reference 83Storr, Ialongo, Anthony and Breslau2007). Our finding that preexisting conduct disorder in particular confers strongest risk of lifetime traumatic exposure is consistent with previous findings in both U.S. civilian (Afifi et al., Reference Afifi, McMillan, Asmundson, Pietrzak and Sareen2011) and military (Koenen et al., Reference Koenen, Harley and Lyons2002, Reference Koenen, Fu and Lyons2005) samples. Preexisting ADHD, in contrast, confers the least overall trauma liability relative to other disruptive disorders. Its modest relative risk for auto accidents was especially unexpected, given the vast public health literature devoted to ADHD-related road accidents (Barkley et al., Reference Barkley, Guevremont, Anastopoulos, DuPaul and Shelton1993). However, a recent meta-analysis isolated such excess risk to ADHD-related drivers to cases with comorbid ODD, CD, and/or other conduct problems (Vaa, Reference Vaa2014). The modest risk of accidents among drivers with ADHD may also reflect higher treatment rates and/or more effective treatments for ADHD vs. other high-risk psychiatric disorders. A 58% reduction in risk of serious transport accidents was found for male Swedish Registry ADHD drivers under psychostimulants vs. untreated ADHD drivers (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Lichtenstein, D'Onofrio, Sjolander and Larsson2014).

Our finding that preexisting PTSD confers least overall risk for subsequent exposure to trauma seems at odds with the central role that trauma is hypothesized to play in the etiology and maintenance of the disorder. One possible interpretation of this finding is that trauma-exposed individuals become reactively risk averse, systematically selecting themselves out of future hazardous situations and settings. Slight support for this is seen in the minimally decreased but significant odds of accidents and injuries (OR = 0.9) and unexpected death of a loved one (OR = 0.9) among multivariate analyses. However, there is no corresponding decrease in relative risk for highly threatening traumas such as exposure to organized violence, participation in organized violence, or physical violence victimization (all OR = 1.0). Bivariate analyses show insignificantly reduced odds of being a civilian in a war zone and witnessing a physical fight at home, but significantly reduced odds of combat experience (OR = 0.8).

Another possibility is that traumatized individuals might defensively disavow danger as well as actively avoid it. Memory encoding and retrieval deficits are paradigmatic of PTSD phenomenology, and are characterized by overgeneral, fragmented, or biased recall (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Caspi and Gil2003; Brewin, Reference Brewin2011, Reference Brewin2016); and inaccurate self-report of discrete autobiographical memories in particular (Brennen et al., Reference Brennen, Hasanovic and Zotovic2010). A limitation to interpretation here is that history of both prior psychiatric symptoms and traumas was assessed by self-report contemporaneously and retrospectively, after the onset of PTSD, and this may have impacted recall of the traumas. A final noteworthy possibility is that the low relative-risk of trauma exposure following PTSD diagnosis may reflect a beneficial treatment effect (i.e., effective treatment may have reduced the rates of recurrent exposures). However, this seems unlikely given that the survey was conducted in 29 countries across 6 continents, including numerous developing countries with poor access to mental health treatment.

An interesting corollary to PTSD's lowest overall trauma risk is separation anxiety's highest (96.6% significant positives in bivariate analyses). In the case of separation anxiety, however, disproportionately high, significant exposures to “fateful” events, such as toxic chemical exposure (OR = 2.8), human-made disaster (OR = 2.1), and natural disaster (OR = 1.6), suggest that these respondents may have higher “experienced” traumas, but not higher “actual” traumas. Something of this sort was demonstrated in a city-specific, prospective longitudinal survey that coded events with both Criterion A1 and A2 (intense fear response and helplessness) (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Hofler and Perkonigg2002a). Presence of an anxiety disorder at baseline predicted increased reports of high A2 exposures at follow up. If a similar dynamic is at work in the WMH data, then the consistent association of separation anxiety disorder with high trauma exposure might be due to a reporting artifact.

Taken together, the results reported in this chapter show clearly that trauma exposure is far from random. To the extent that the associations documented here are causal, interventions either to prevent CAs or, more realistically, to provide treatment for individuals exposed to CAs might profitably include components designed to reduce the elevated risks of future trauma exposure documented here. The same could be said for psychotherapies provided to patients with the DSM-IV disorders considered here. It is relevant in this regard that the subsequent traumas linked to the CAs and disorders considered here are not only required for subsequent PTSD, but are also known to be powerful predictors of major depression (Dorsey et al., Reference Dorsey, McLaughlin and Kerns2017), behavioral and substance use problems (Kilpatrick et al., Reference Kilpatrick, Ruggiero and Acierno2003), psychosis (Read et al., Reference Read, van Os, Morrison and Ross2005; Mayo et al., Reference Mayo, Corey and Kelly2017), personality disorders (Golier et al., Reference Golier, Yehuda and Bierer2003; Bandelow et al., Reference Bandelow, Krause and Wedekind2005), developmental delays (Briggs-Gowan et al., Reference Briggs-Gowan, Carter and Clark2010) and cognitive deficits (Karstens et al., Reference Karstens, Rubin and Shankman2017). Trauma has also been implicated in the transitions both between psychiatric disorders (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, McLaughlin, Hamilton and Keyes2017) and from psychiatric disorders to serious physical disorders (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Basu and Walsh2016). While an evaluation of the plausibility of developing interventions to reduce trauma exposure is beyond the scope of this chapter, the results reported here make it clear that the associations that might be the targets of such interventions are substantial.