Throughout time and space, individuals have manipulated the dimensions of various objects including monuments, vessels, and architecture. In some instances, individuals have scaled up objects, making them larger than their referents. Quirigua Stela E—a 10.6 m tall, 65-ton stone monolith with a larger-than-life image of K’ahk’ Tiliw Chan Yopaat (Looper Reference Looper2003:147)—is a prominent example. In other instances, individuals have scaled down objects, making them smaller than their referents. Maya peoples, for example, carved more than 250 miniature manos and metates—measuring on average 13.5 × 8.8 × 1.5 cm—and deposited them in Balankanche Cave near Chichen Itza (Andrews Reference Andrews1970:32; Vail and Hernandez Reference Vail, Hernandez and Geoffrey2012).

Scaled-up objects are often visible and conspicuous parts of Maya communities, and scholars have historically understood them as demonstrating rulers’ authority. Bruce Trigger (Reference Trigger1990:119, 125), for example, suggests that objects whose “scale and elaboration exceed the requirements of any practical function” were fundamentally “embodiments of large amounts of human energy and hence symbolize the ability of those for whom they were made to control such energy to an unusual degree.” As discussed in the conclusion, some older (e.g., Webb Reference Webb1964:572–584) and several recent considerations of monumentality (e.g., Hutson Reference Hutson2023; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, Vázquez López, Fernandez-Diaz, Omori, Belén Méndez Bauer and Melina García2020; Rosenswig and Burger Reference Rosenswig, Burger, Richard and Robert2012) challenge such assumptions. Scaled-down objects are often less conspicuous and easier to overlook. As detailed later, scholars have interpreted some Maya miniatures as prototypes for larger constructions or, particularly in the early to mid-twentieth century, as evidence for supposed Postclassic (AD 1100–1550) sociopolitical decadence and decay (e.g., Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1955; see also Sabloff Reference Sabloff2007).

How can scholars make sense of the manipulation of dimensions? More specifically, how can archaeologists best interpret Postclassic Maya scaled-down objects? This article argues that some Postclassic artifacts are usefully understood as miniatures—as abstracted and compressed scaled-down versions of referents—and that they speak not to sociopolitical decline but instead to the purposeful Postclassic manipulation of dimensions. To do so, it considers one type of artifact: small, uncarved stelae erected during the Postclassic period. After reviewing documented examples of these monuments in the Maya Lowlands, the article introduces two examples from Punta Laguna, Yucatán, Mexico. To conclude, it considers how interpreting these monuments as miniatures changes conventional understandings of Maya stelae and Postclassic practices.

Manipulating Dimensions

The manipulation of dimensions involves more than merely creating large or small objects. Rather, such objects must be scaled-up or scaled-down versions of a referent (Angé and Pitrou Reference Pitrou2016; Dehouve Reference Dehouve2016; Foxhall Reference Foxhall2015). A miniature, for example, “must be a reduced version of something that was originally bigger . . . and it should be consciously created as such” (Garfield Reference Garfield2019:3–4). Indeed, not all small objects are miniatures. Spindle whorls and ear flares, for example, are small but not miniature. Nor are all miniatures small: the Venetian Hotel in Las Vegas, a microcosm of the city of Venice, sleeps 4,000 (Garfield Reference Garfield2019:3). Archaeologically, Maya civic-ceremonial centers have been understood as microcosms of the universe (e.g., Ashmore Reference Ashmore1991; Ashmore and Sabloff Reference Ashmore and Sabloff2002) and thus as miniatures despite their large size.

The manipulation of dimensions, specifically the creation of miniatures, also differs from the creation of models. As Douglas Bailey (Reference Bailey2005:29) has noted, “Models are attempts at precision” to “reproduce reality in reduced dimensions with the maximum detail retained.” Miniatures, however, are not precise and do not attempt exact replication. Instead, they operate through the dual processes of abstraction and compression (Bailey Reference Bailey2005; Davy Reference Davy2015; Foxhall Reference Foxhall2015). Because miniatures require a reduction in detail, their creators must make active decisions about which features to retain and which to forgo. In the case of figurines, heads may be highly detailed while bodies remain ill-defined. Or the positioning of arms and legs may be crucial, while faces are indistinct (e.g., Johnson Reference Johnson2018). As others have argued, the “series of choices by which detail is reduced are some of the most important in miniaturization” (Davy Reference Davy2015:9).

In addition to abstraction, the creation of scaled-down objects also involves compression (Bailey Reference Bailey2005:32–33; Foxhall Reference Foxhall2015). Miniature objects often concentrate and produce denser expressions of specific ideas and actions (Bailey Reference Bailey2005:32–33). Scale and intensity are not necessarily correlated, and scaled-down objects can be quite potent (Alberti Reference Alberti, Alberti, Jones and Pollard2016). Bailey (Reference Bailey2005:32–33) argues, “At the same time as miniaturism reduces elements and properties it multiplies the weight of the abstracted remainder.”

Archaeologists have recovered scaled-down objects from various times and places, including Iron Age Iberia (López-Bertran and Vives-Ferrándiz Reference López-Bertran and Vives-Ferrándiz2015), Hellenistic Babylonia (Langin-Hooper Reference Langin-Hooper2015), and the prehispanic American Southwest (Fladd and Barker Reference Fladd and Barker2019). Although sometimes described as “distinct and troublesome” (Davy Reference Davy2018:970), these objects are generally understood to “epitomize, echo and reverberate meanings captured in and associated with other objects, while creating new meanings of their own” (Foxhall Reference Foxhall2015:1). Archaeologists have recovered miniature artifacts from ritual contexts such as caches and graves and often in association with sacrificial offerings of food and other substances (Angé and Pitrou Reference Pitrou2016; Dehouve Reference Dehouve2016). Several scholars thus associate miniaturization with processes of communication between human and other-than-human entities (Pitrou Reference Pitrou2016). Some have even suggested that scholars understand miniature objects “not as icons of their prototypes, but indexes of entire modes of communication” (Davy Reference Davy2018:981).

Members of various Mesoamerican groups manipulated dimensions. At Teotihuacan, for instance, “three-temple complexes appear in several different scales,” with the “triadic structures of the apartment compounds represent[ing] the smallest” (Headrick Reference Headrick2007:105). Within the Maya area, archaeologists have recovered scaled-down objects produced during all major time periods; for example, miniature “mushroom stones,” carved during the Preclassic period (1800 BC–AD 250) at Kaminaljuyu (Borhegyi Reference Borhegyi1961) and assemblages of miniature vessels from a variety of contexts, including Classic period (AD 250–1100) deposits in the Main Chasm at Aguateca (Ishihara Reference Ishihara2008). At Mayapan, certain Postclassic “figurines represent smaller (scaled down) versions of important entities portrayed in elaborate effigy censers” (Masson Reference Masson and Scott2023:42–43).

Interpretations of these and other Maya miniatures vary. In some instances, scholars have understood scaled-down objects as prototypes for larger constructions. William Haviland (Reference Haviland1962:2), for example, recorded a 9.5 cm tall ceramic object from a midden behind a Late Classic period domestic structure at Tikal that “appeared to be a likeness, in miniature, of a large stone monument, a stela.” He suggested that this object may have been “an artist’s conception of a stela or a model of an actual stela” (Haviland Reference Haviland1962:3). Pantoja Díaz and colleagues (Reference Díaz, Luis, Coba and Aguilar2022:192), to take a second example, documented as part of Structure 461 at Oxmuul in Yucatán “four architectural miniature replicas,” each standing approximately 50 cm high. Because they exemplified an architectural style prominent in the Peten region of Guatemala, Pantoja Díaz and coauthors (Reference Díaz, Luis, Paredes, Zaldívar Rae, Arroyo, Salinas and Álvarez2018:161) argue that these replicas are “claro ejemplos de esa traslación del sistema constructivo edificatorio en su aspecto formal y técnico del lugar de origen a nuevas tierras de Norte de Yucatán” (clear examples of the transfer of these building construction systems in their formal and technical aspect from their place of origin to the new lands of Northern Yucatán; author’s translation).

In other instances, and particularly in the early to mid-twentieth century, scholars have understood Maya scaled-down objects, especially those produced after AD 1100, as evidence for the traditional though problematic interpretation of the Postclassic as a period of decline (e.g., Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1955; see also Sabloff Reference Sabloff2007). Nineteenth-century explorer John Lloyd Stephens (Reference Stephens1843:406), for example, remarked that the miniature shrines he saw outside Tulum’s city walls were “so slight that they could be pushed over with a foot.” In his 1927 account of his survey of the east coast of the Yucatán Peninsula, Gregory Mason (Reference Mason1927:149) likewise described the miniature shrine he encountered as “a poor thing.” And Tatiana Proskourikoff (Reference Proskouriakoff1955:85, 86, 82) mentioned similar “shoddily-built temples” and “small shrines that crowd the courts of the ceremonial center” at Mayapan as one reason she understood the Postclassic period as a “pale reflection of earlier glories.”

Scholars have long criticized such arguments (e.g., Masson Reference Masson, Hendon, Joyce and Overholtzer2021; Rice Reference Rice, Arnauld and Breton2013; Sabloff Reference Sabloff2007; Sabloff and Rathje Reference Sabloff and Rathje1975), and some have offered alternative interpretations of Postclassic scaled-down objects. Marilyn Masson (Reference Masson and Scott2023:42) for instance, argues that miniatures at Mayapan suggest not decadence but a “continuum of elaboration that often correlated with scalar differences in the contexts of their use.” Nevertheless, and even though some Postclassic structures are quite large—not all Postclassic features are diminutive—the presence of small architecture has been among the primary rationales for negative assessments of the Postclassic period (e.g., Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson and Lope2014:24–25).

This article builds on older and recent efforts to understand Postclassic practices in more theoretically robust ways. Rather than focusing on architecture, this article considers one specific type of Postclassic artifact that has received little scholarly attention—small, uncarved stelae—and suggests they are usefully understood through the concept of miniaturization.

Small, Uncarved Postclassic Stelae

Epigraphers, art historians, archaeologists, and others have long studied Maya freestanding stone monoliths, known as stelae, or lakam tuunoob in Mayan (Stuart Reference Stuart1996:151–154; Reference Stuart, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010:283). Although scholars traditionally understood these monuments—sometimes, though not always, paired with altars—as diagnostic of Classic Maya centers, various Mesoamerican groups erected stelae in different time periods (see Jordan Reference Jordan2014:1–3). Some contemporary Maya rituals may even stem from more ancient practices associated with the setting of these monuments (Christie Reference Christie2005; Frühsorge Reference Frühsorge2015).

Stelae differ considerably in appearance, and their meanings are complex, multilayered, and variable (Jordan Reference Jordan2014; Stuart Reference Stuart1996; Reference Stuart, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010). Carved Maya stelae, often bearing hieroglyphic inscriptions and images of rulers, likely served as extensions and embodiments of royal personages (Stuart Reference Stuart, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010:291). Yet many stelae are uncarved, suggesting “their purpose was not simply to bear images and texts in a permanent way” (Stuart Reference Stuart1996:154). Keith Jordan (Reference Jordan2014:10) writes, “Although photos of these ostensibly non-figural monuments do not make it into the folio volumes or coffee table tomes . . . at some Maya sites they comprise the majority of surviving stelae.” Unfortunately, it is unknown, and perhaps unknowable, whether uncarved stelae were covered in stucco, painted, or otherwise decorated with perishable materials, such as cloth (Guernsey Reference Guernsey, Guernsey and Reilly2006; Jordan Reference Jordan2014:10–11; Stuart Reference Stuart, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010:284–285).

Why erect uncarved and perhaps undecorated stone monuments? David Stuart (Reference Stuart1996:154) argued that “the medium was as essential part of the message.” Put differently, for Maya peoples, stone itself was “an inherently powerful and timeless substance, a permanent material both of the earth and transcendent” (Stuart Reference Stuart, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010:286). Indeed, Maya peoples understood stone, including limestone, as animate, agentive, and as having its own life force and life cycle (e.g., Stuart Reference Stuart, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010:288–289; see Horowitz et al. Reference Horowitz, Brown, Yaeger and Cap2024). It is perhaps for this reason that even uncarved stelae served important roles in calendric ceremonies (Stuart Reference Stuart1996:149). Citing epigraphic data and ethnohistoric accounts (e.g., Tozzer Reference Tozzer1941:38–39), Stuart (Reference Stuart, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010:289) argues that such stelae were “embodiments of abstract time,” specifically of K’atun (approximately 20-year) periods and their subdivisions. Upright stone monuments, regardless of decoration, have also been understood as vertical axes mundi. Following the work of Linda Schele and David Freidel (Reference Schele and Freidel1990:71–72), Jordan (Reference Jordan2014:2) argued that “stelae are linked symbolically to the cosmic trees and pillars of Maya cosmology, which were believed to support the earth and link it to the celestial world above and the underworld of the dead below” (see also Christie Reference Christie2005).

During the Postclassic period, some Maya communities erected carved stelae. At Mayapan, Proskouriakoff (Reference Proskouriakoff, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962:134; see also Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson and Lope2014; Milbrath and Peraza Lope Reference Milbrath and Lope2003; Reference Milbrath and Lope2009) identified at least 13 carved stelae, in addition to at least 25 uncarved ones likely covered in stucco and painted, which suggested the “strong persistence, perhaps even a revival, of the stela complex.” At Tulum, Samuel Lothrop (Reference Lothrop1924:41–46) noted at least three carved stelae, some similar in style to those at Mayapan. Postclassic Maya peoples also reused and reset stelae inscribed during earlier time periods (e.g., Cecil and Pugh Reference Cecil and Pugh2018:159–160). Excavations at La Milpa suggest that its Postclassic inhabitants relocated and reset at least seven stelae initially carved and erected during the Classic period (Hammond and Bobo Reference Hammond and Bobo1994). At Tulum, Stephens and Catherwood found fragments of a stela, which included a Classic period long count date, within a Postclassic structure (Lothrop Reference Lothrop1924:41). And at Cobá, Postclassic peoples moved stelae carved during the Classic period, in some instances placing them within newly built shrines (Con Uribe and Gómez Cobá Reference Con, María and Cobá2008:119; Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Eric, Eric, Thompson, Pollock and Charlot1932:127).

Although discussed less frequently, Postclassic peoples also erected small, uncarved stelae. Such stelae are defined here as monolithic stone slabs approximately the same height or shorter than an ancient Maya person. They are thus defined as stone slabs with heights at or less than 1.75 m, the tallest estimated height for Maya adults in a classic study of stature at Tikal (Haviland Reference Haviland1967; see also Wright and Vásquez Reference Wright, Vásquez, Klaus, Harvey and Mark2017). Several (e.g., Dehouve Reference Dehouve2016) have noted the importance of the human body when analyzing object scale: “Dimensionality implies a relationship between someone who is looking . . . and the object being viewed” (Angé and Pitrou Reference Pitrou2016:408). These stelae are further understood to be Postclassic when found in association with Postclassic architecture, such as East Coast–style miniature masonry shrines (Andrews and Andrews Reference Andrews and Anthony1975:50–54; Lorenzen Reference Lorenzen2003) or Postclassic ceramics, such as Chen Mul modeled incense burners (Robles Castellanos Reference Castellanos and Fernando1990:219–237).

As noted, “The notion of a referent is central” in analyses of miniaturization and distinguishes miniatures from merely small objects (Dehouve Reference Dehouve2016:505). Yet referents themselves vary. Classic period stelae, for example, are far from standardized. Nevertheless, it was common for these monuments to be significantly taller than an ancient Maya person and to bear hieroglyphic inscriptions and figural representations. Although many stelae at Cobá are too fragmented to measure, J. Eric Thompson (Reference Thompson, Eric, Eric, Thompson, Pollock and Charlot1932) reported the measurements of 12 intact carved stelae, each with figural representations of rulers and averaging 2.5 m in height. Stela 4, for example, stands 3.15 m high and includes an image of Lady K’awiil Ajaw holding a double-headed serpent bar and standing atop captives (Guenter Reference Guenter and Travis2014). It is these Classic period monuments that are usefully understood as referents.

Analyzing small, uncarved stelae is challenging, in part, because archaeologists have often ignored them or documented them quickly and incompletely. Despite his exhaustive consideration of each carved stela at Cobá, Thompson (Reference Thompson, Eric, Eric, Thompson, Pollock and Charlot1932:178), for instance, wrote in his description of the uncarved stela C1 that he “omitted to take the measurements of this monument.” Datasets thus remain incomplete. Nevertheless, this article maintains that scholars can usefully understand these stone slabs—which sometimes reach only 60 cm in height—as miniatures that reference, yet are distinct from, their Classic period counterparts.

Previously Documented Examples of Small, Uncarved Postclassic Stelae

Archaeologists have noted small, uncarved Postclassic stelae at several sites along the east coast of the Yucatán Peninsula in Guatemala and at Mayapan (Figure 1; Table 1). In 1955, E. Wyllys Andrews noted a small, uncarved stela at Xcaret and at Paamul, neither of which remain in situ today (Andrews Reference Andrews1972:474; Andrews and Andrews Reference Andrews and Anthony1975:70–71). In 1927, Gregory Mason and Herbert Spinden (Mason Reference Mason1927:169) noted two small, uncarved stelae at Muyil, although Walter Witschey (Reference Witschey1993:22) suggests these objects, also no longer in situ, may have been fallen lintel stones. Even though E. Wyllys Andrews published a photograph of the stela at Paalmul, (Figure 2) neither he nor Mason documented the dimensions of any of these monuments. At Tulum, Lothrop (Reference Lothrop1924:45) briefly described Stelae 4, 5, and 6 as small, worked, uncarved stones with rounded tops. Notably, “when turned over, the unexposed face [of Stela 4] was found to be covered with plaster. . . . The left half was painted blue and the right half was the natural white” (Lothrop Reference Lothrop1924:45). More recently, Christina Halperin (Reference Halperin2014:330) reported two “small, uncarved Late Postclassic style monuments” at Tayasal in the Peten region of Guatemala. Maya peoples erected one in front of a Late Postclassic shrine and the other in front of an adjacent small, natural hill.

Figure 1. Map showing the location of all archaeological sites mentioned in the text.

Figure 2. Photograph of the small, uncarved stela at Paalmul (from Andrews and Andrews Reference Andrews and Anthony1975:Figure 87). Note the machete to the left indicating size (courtesy of the Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University).

Table 1. Uncarved Postclassic Maya Stelae with Heights at or Less than 1.75 m.

References to small, uncarved stelae at Mayapan are also present but are vague. When discussing structure Q-142, a colonnaded hall, Proskouriakoff (Reference Proskouriakoff, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962:111) wrote, “Some distance to the east, in front of the eastern wing, lies a large worked stone that may be a small, plain stela.” When discussing structure Q-155, a shrine, she noted that a “fragment of a small plain stela 72 cm high, 58 cm wide, and 24 cm thick, tapering lightly toward the top, lies at the foot of the stairway” (Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962:115). Tellingly, these monuments are neither numbered nor illustrated. Archaeologists have, however, provided more extensive descriptions of small, uncarved Postclassic stelae at Isla Cilvituk in southwestern Campeche, at Cobá in the Yucatán Peninsula, and at Topoxté in the Peten region of Guatemala.

In a mid-twentieth-century Carnegie Institution of Washington report, E. Wyllys Andrews (Reference Andrews1943:36–45) documented the Cilviltuk region (see Alexander Reference Alexander2000, Reference Alexander, Kepecs and Alexander2005; Alexander et al. Reference Alexander, Hunter, Arata, Martínez Cervantes, Scudder, Götz and Emery2013), describing a Postclassic architectural group he labeled Isla Cilvituk A: a rectangular plaza with buildings on each of its four sides. There were “two small stelae in the plaza, each in front of a low platform. Stela 1 is 12 cm thick, 56 cm wide, and now stands 60 cm above ground. Stela 2 is about the same size. Both are uncarved” (Andrews Reference Andrews1943:42). During an earlier visit to the site, Teobert Maler (Reference Maler1910:143) noted that these same two stelae were “without bas-relief, but one of them displayed distinct traces of smooth stuccoing painted red, and a thin round stone might be regarded as a small circular altar.” Unfortunately, no photos have been published.

The Carnegie Institution of Washington systematically studied Cobá in the 1930s. In the resulting report, Thompson and colleagues (Reference Thompson, Pollock and Charlot1932) documented five small, uncarved stelae likely erected during the Postclassic period. Stela A1 (Figure 3) lies at the center of Sacbe 9, between the Cobá and Macanxoc groups, and Stelae B1, B3, B4, and B5 are located in the Cobá group in various contexts, including in plazas and at the bases of structures (Table 1). Stela B3 was found in association with an unmeasured square altar (Altar B9). Thompson found the dimensions of these small monuments puzzling. After recording the measurements of Stela A1, he noted, “These dimensions are rather small for a stela, and on that ground one feels a little diffident about classifying the stone as such. However, Stela B3, which is undoubtedly a stela, is of even smaller dimensions” (Thompson Reference Thompson, Eric, Eric, Thompson, Pollock and Charlot1932:172).

Figure 3. Stela A1 at Cobá (photograph by author). (Color online).

Archaeologists found Stela B1 inside a Postclassic shrine on top of the Cobá group’s largest structure. Thompson (Reference Thompson, Eric, Eric, Thompson, Pollock and Charlot1932:175) wrote that the “stone had flaked away to a very remarkable extent, and . . . the monument may have originally been carved on the front.” Some (e.g., Benavides Castillo Reference Benavides Castillo1976:69) suggest that this stela is best classified as carved and that it exhibits extensive weathering despite being placed inside a masonry structure. It may also be that Postclassic peoples purposefully removed any existing images or inscriptions from the stone slab before erecting it in the shrine. Such stripping of carved surfaces has been noted elsewhere, including on Stela 21 in Group B at Uaxactun (Ricketson and Ricketson Reference Ricketson and Ricketson1937:156; see also Baker Reference Baker1962:291; Hammond and Bobo Reference Hammond and Bobo1994:25; Just Reference Just2005).

In the 1970s, excavations led by Antonio Benavides (Reference Benavides Castillo1976:19–21) uncovered offerings associated with Stela B1, including two caches deposited beneath the temple floor. The ceramic artifacts from these caches comprise the Postclassic Pizá ceramic subcomplex and include whole Cumtun composite censers with attributes of the central Mexican deity Tlaloc, almost complete Espita applique censers, and whole Colibí incised plates (Robles Castellanos Reference Castellanos and Fernando1990:239–251). Nonceramic artifacts included perforated shell pendants, fragments of specular hematite, and a jade representation of the rain god, Chaak.

Topoxté’s Postclassic inhabitants also erected a series of small, uncarved stelae and associated altars (see Bullard Reference Bullard1960; Chase Reference Chase1976; Johnson Reference Johnson, Arlen and Prudence1985). In the early twentieth century, Maler (Reference Maler1908:58–59) documented nine such monuments in the site’s center, including one with “a circle of six little perforations, probably for the insertion of some kind of adornment.” Since then, others (Hermes and Noriega Reference Hermes, Noriega, Juan and Escobedo1998; Hermes et al. Reference Hermes, Calderón, Pinto, Ugarte, Juan and Escobedo1996; Wurster Reference Wurster2000) have studied these stone slabs, many of which had been broken and moved since Maler’s visit. According to Cyrus Lundell (Reference Lundell1934:9), “The nine small stelae . . . were located. Only three of the stelae remain standing: the others are broken and so scattered that it is difficult to determine their original positions. . . . Fragments of stela-like stones are numerous so there may have been more than the nine small monoliths indicated by Maler.” Lundell (Reference Lundell1934:11) also noted that several of these stones still retained fragments of stucco coatings.

William Bullard (Reference Bullard1970:271–273, Figure 11A) offered the most detailed description of these monoliths and associated altars—renumbering them, noting their locations on a plan drawing, recording the measurements of three, and excavating near the newly designated Stela A1. These excavations produced Postclassic ceramics—unfortunately not described in detail—but no caches or other special deposits. Like Lundell, Bullard noted that these stones had been covered in plaster and that it remained difficult to determine their exact number and original placement. He wrote, for example, that a small monolith associated with Structure F and two small monoliths on the south side of Structure A “may have been additional stelae of the unsculptured type” (Bullard Reference Bullard1970:272).

Existing information about small, uncarved Postclassic stelae is thus sparce. Taken together, these data reveal few patterns and instead suggest that the monuments and the practices associated with them were diverse. These stelae occur both individually and in groups, with and without associated altars, and in a wide variety of nondomestic contexts. Further, many retain traces of perishable surface treatments, including stucco and paint, although it remains unclear whether all or only some of these monuments were decorated. Many questions thus remain. What were the functions of these monuments? How did they relate to broader Postclassic practices? And how did they relate to larger, carved, Classic period stelae so often intimately tied to divine kingship?

Small, Uncarved Postclassic Stelae at Punta Laguna

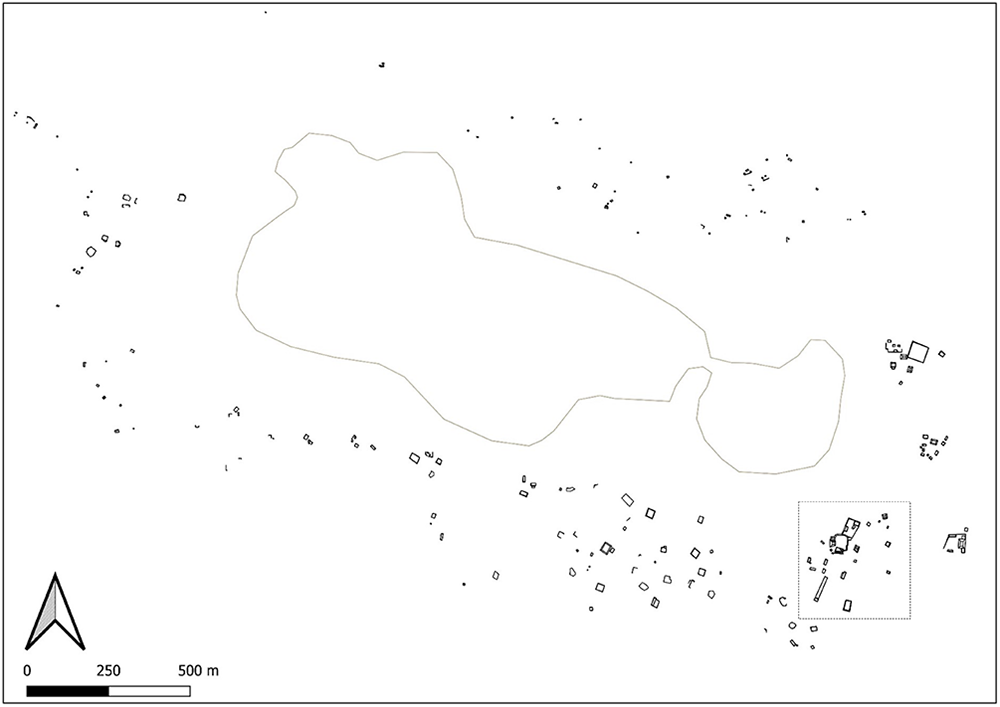

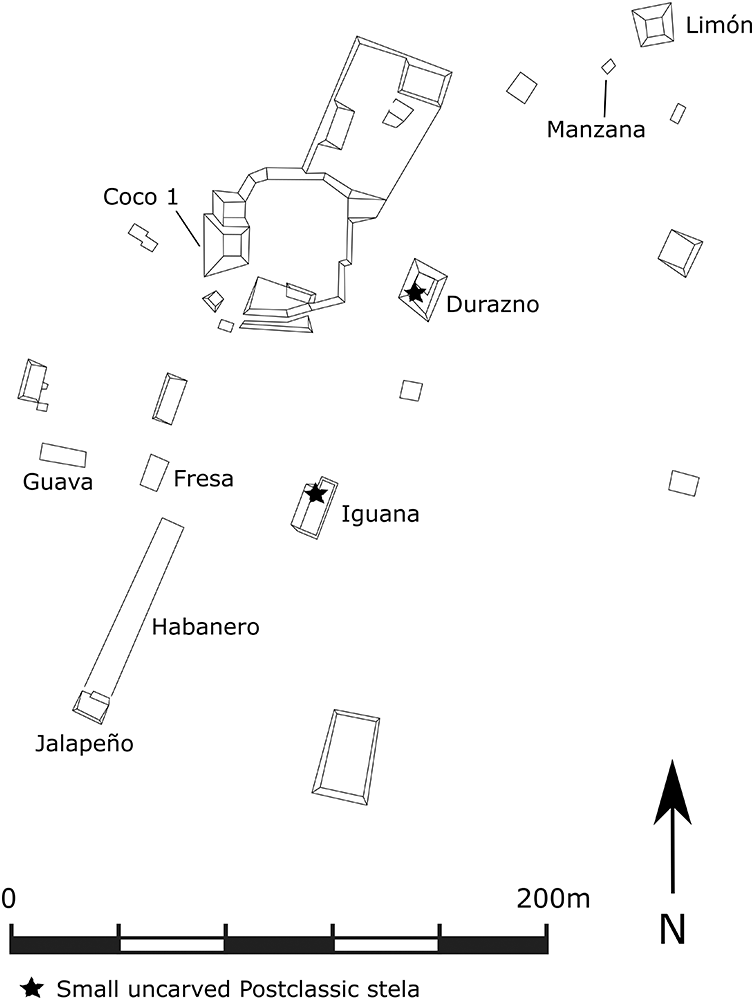

To address these and other questions, the Punta Laguna Archaeology Project (PLAP) documented and conducted excavations in association with two small, uncarved stelae at Punta Laguna in the northeastern interior of the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico (Figure 1). The archaeological site of Punta Laguna covers approximately 200 ha immediately surrounding a three-basin lagoon and includes a cenote containing an ancient mortuary deposit of at least 120 individuals (e.g., Rojas Sandoval Reference Rojas Sandoval2011); a series of caves; and more than 200 mounds, ranging in height from just above ground level to approximately 6 m and including both house mounds and civic-ceremonial structures (Figures 4 and 5; Kurnick and Rogoff Reference Kurnick and Rogoff2020). A type-variety analysis of all excavated ceramics suggests that Maya peoples occupied Punta Laguna continuously or recurringly from 600/300 BC through AD 1500/1550 (Kurnick et al. Reference Kurnick, Rogoff and Aragón2024). Of the 20 mounds so far excavated at Punta Laguna, 9—Coco 1, Durazno, Fresa, Habanero, Guava, Iguana, Jalapeño, Limón, and Manzana—have ceramic, architectural, or both types of evidence of use during the Postclassic period (Figure 5). Of these mounds, only Jalapeño has evidence of residential Postclassic occupation.

Figure 4. The archaeological site of Punta Laguna (map by David Rogoff and Sarah Kurnick). See Figure 7 for an enlarged view of the area within the box.

Figure 5. The southeast portion of the archaeological site of Punta Laguna, showing the location of all mounds and stelae mentioned in the text (map by David Rogoff and Sarah Kurnick).

Project members documented and conducted excavations in association with two small, uncarved Postclassic stelae at the site. The Durazno stela is a limestone slab measuring 125 cm tall × 55 cm wide × 15 cm thick (Figure 6). All sides are significantly eroded, and there is no evidence of inscriptions, paint, or stucco. It is located on top of the approximately 4 m tall Durazno mound, likely constructed during the Late Preclassic period, and forms part of a Postclassic architectural complex that includes a miniature masonry shrine and a low rectangular altar. Decades ago, community members reerected the fallen stela, leaning it against a nearby tree.

Figure 6. The Durazno stela at Punta Laguna (photograph by Conrad Erb). (Color online).

Project members excavated through approximately 20 cm of soil on the summit of the Durazno mound, until reaching the top of the structure’s fill. These excavations did not reveal any caches. Project members did, however, uncover surface deposits likely associated with the use of the stela. Artifacts found within 1 m of the base of the stela included 290 ceramic sherds, all of which were fragments of anthropomorphic Chen Mul modeled incense burners, a chert flake, and a greenstone bead. None of the ceramic fragments could be reassembled into whole or partial censers. Areas more than a meter from the base of the stela did not contain the same density of ceramics or any nonceramic artifacts.

The Iguana stela is a similar limestone slab, measuring 118 cm tall × 54 cm wide × 20 cm thick (Figure 7). All sides are significantly eroded, and there is no evidence of inscriptions, paint, or stucco. This stela is located on the approximately 1.5 m tall Iguana mound, which includes a five-course staircase on its northwest side. There are no obvious Postclassic architectural features, such as shrines or altars. Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) did not permit excavations into the fill of the Iguana mound, but excavations around its perimeter produced a mix of sherds (n = 481) dating to the Late Preclassic (30%), Early Classic (2.3%), Late Classic (57%), and Postclassic (10.7%) periods. Decades ago, community members also re-erected this fallen stela, propping it up with stones.

Figure 7. The Iguana stela at Punta Laguna (photo by Conrad Erb). (Color online).

PLAP project members again excavated through approximately 20 cm of soil on the summit of the mound, until reaching the top of the structure’s fill. These excavations did not reveal any caches but as before, did find uncovered surface deposits likely associated with use of the stela. Artifacts found within a meter of the base of the Iguana stela included 343 ceramic sherds, 326 (95%) of which were produced during the Postclassic period. Of those sherds, 292 (89%) were fragments of anthropomorphic Chen Mul modeled incense burners; fragments of Mama Roja and Navula Unslipped vessels were also present. Again, none of the ceramic fragments could be reassembled into whole or partial censers. Nonceramic artifacts included an obsidian blade, 10 fragments of marine shell, and two pieces of coral. Notably, areas more than a meter from the base of the stela did not contain the same density of ceramics or any nonceramic artifacts.

Such a small sample size allows only preliminary interpretations. Nevertheless, data from Punta Laguna suggest several insights. First, the areas adjacent to small, uncarved, Postclassic stelae were locations for ceremonies conducted by individuals or small groups. Additional excavations revealed no evidence for large-scale feasting or other social gatherings in association with these monuments or the mounds on which they were set. Second, the monuments’ contexts differed. One stela was placed near a miniature masonry shrine and a low rectangular altar; the other was not. One was located on an approximately 4 m tall pyramidal structure and the other on an approximately 1.5 m tall mound with a wide staircase. And one was associated with chert and greenstone, and the other with marine shell, obsidian, and coral.

Perhaps most notably, both stelae were associated with the final deposition of hundreds of mixed fragments of previously broken and now unreconstructable Chen Mul modeled anthropomorphic incense burners. Although such surface censer scatters are common at other Postclassic sites—including Mayapan (Masson et al. Reference Masson, Alvarado, Lope, Milbrath, Travis and Brown2020), Cerros (Walker Reference Walker1990), Champotón (Pugh and Rice Reference Pugh, Rice, Prudence and Don2009), and Lamanai (Howie et al. Reference Howie, Aimers, Graham and Martinón-Torres2014)—their meaning remains uncertain. Nevertheless, their association with stelae is perhaps unsurprising. Karl Taube (Reference Taube and Stephen1998:139) argues that Maya peoples understood censers, likely conceptually linked to three stone hearths, as axes mundi: “conduit[s] between the levels of earth, sky, and underworld.” Surface censer scatters may thus be the deactivation and final deposition of objects that, like stelae, emphasize the connections between the realms of the universe and allow for communication between human and other-than-human entities. Furthermore, some censers, like stelae, were important parts of calendric ceremonies, particularly those associated with K’atun cycles. Diego de Landa (Tozzer Reference Tozzer1941:166–169) described such a use of censers among sixteenth-century Maya peoples in Yucatán, and Diane Chase (Reference Chase, Arlen and Prudence1985:116–125) documented archaeological evidence of similar Postclassic practices at Santa Rita Corozal.

Interpreting Small, Uncarved Postclassic Stelae as Miniatures

Scholars have written extensively about Classic Maya stelae, particularly those bearing inscriptions and figural representations. Several have also considered the erection of uncarved stelae in the Preclassic period (e.g., Guernsey et al. Reference Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010), often emphasizing that “their natural form and lack of decoration suggest a very ancient concern with the intrinsic idea of stone monumentality” (Stuart Reference Stuart, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010:285). Yet, even though some have studied carved Postclassic stelae (e.g., Milbrath and Peraza Lope Reference Milbrath and Lope2009) or the Postclassic reuse of stelae inscribed during the Classic period (e.g., Cecil and Pugh Reference Cecil and Pugh2018), few have examined small, uncarved, Postclassic stelae. Such a lack of scholarly attention may reflect the interests of archaeologists more so than the concerns of ancient Maya peoples. Lars Frühsorge (Reference Frühsorge2015:176) reminds us, “We should take caution not to be misled by the physical size or the visual attraction of an object when we speculate about its . . . importance.” Indeed, scaled-down, often inconspicuous, objects offer significant insights.

Despite uncertainty about the function and meaning of small, uncarved Postclassic stelae, understanding them as miniatures changes conventional interpretations of Maya stelae and of Postclassic practices in meaningful ways. At a basic level, the concept of miniaturization reframes the size of these monuments as a purposeful choice and conscious decision, rather than as a necessity imposed by a lack of skill, lack of resources, or sociopolitical decadence and decay. As noted, scholars have historically described Postclassic peoples as passive respondents to social, political, and environmental change. Understanding small, uncarved stelae as miniatures emphasizes that Postclassic peoples were agentive, rather than merely reacting to events beyond their control. Put differently, the concept of miniaturization stresses that Postclassic people actively produced, and were produced by, their built environment and did not, as Harry Pollock (Reference Pollock, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962:17) suggested, “f[a]ll heir to an impoverished culture.”

Such a reframing, in turn, encourages scholars to take seriously small, uncarved Postclassic stelae, to recognize them as a legitimate category of monument rather than as anomalies, and to include them in broader considerations and definitions of Maya monuments. As Sarah Jackson (Reference Jackson2014:117) argues, archaeological categorization, particularly delineation of object types, not only “conducts the critical work of organizing data and materials” but also “offers powerful results in terms of making named things both real and valued.” Large, carved stelae, such as Quirigua Stela E or Cobá Stela 4, need not be considered standards or paragons of Maya monuments. Stelae critically include but need not be defined as “three-dimensional monuments in the format of carved stone slabs depicting human figures . . . commissioned by the ruling elite to visualize their claims to religious and political power” (Christie Reference Christie2005:277; see also Just Reference Just2005:69). Rather than normalizing these specific types of stelae, scholars should, as Jordan (Reference Jordan2014:7) and others (e.g., Reilly Reference Reilly, Virginia and Reents-Budet2005:34) suggest, adopt more inclusive definitions that allow for significant variations in height, surface treatment, and meaning.

Further, as Diane and Arlen Chase (Reference Chase, Chase, Glenn and John2006:173) note, Postclassic Maya peoples “generally are described in negative terms relative to their Classic counterparts: no stela and altar erection, no long-count dates, no slipped polychrome pottery, and no monumental architecture.” Understanding small, uncarved Postclassic stelae as miniatures, as objects created through the processes of abstraction and compression, encourages scholars to eschew such conventional considerations of what these monuments lack—size, hieroglyphic inscriptions, and carved figural representations—and focus instead on what they retain: the medium of stone, suggesting animacy and permanence; their basic shape and upright nature, suggesting their conceptualization as axes mundi; and their placement in nondomestic contexts and association with nondomestic artifacts.

How then can archaeologists best interpret small, uncarved Postclassic stelae? In her consideration of Maya ancestor veneration, Patricia McAnany (Reference McAnany2013:9) argues that Classic period “royal ancestor veneration is an appropriation of a Formative social practice.” Critically, however, “its ritual expression is not just veneration of lineage heads writ large but rather is structurally different in the manner in which genealogy was encoded in written texts and iconography . . . [and] in that ancestors were invoked to substantiate claims to divinity” (McAnany Reference McAnany2013:9). It may be that larger-than-life Classic period stelae with hieroglyphic inscriptions and figural representations represent a similar royal appropriation of a much older practice of erecting stone slabs—a practice that, like ancestor veneration, began earlier (Stuart Reference Stuart, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010:283) and continued well after the demise of royal dynasties. Royals may thus have co-opted the erection of stone slabs, as they did ancestor veneration, to substantiate claims to divinity. In so doing, they may have used written texts and iconography to position themselves as both axes mundi and as embodiments of time (Schele and Freidel Reference Schele and Freidel1990:90–91; Taube Reference Taube and Stephen1998).

If so, the choice to erect miniature stelae—abstracted and compressed, scaled-down versions of carved Classic period referents—may reveal some Postclassic Maya peoples’ decoupling of stelae and divine kingship and perhaps the reclamation of upright stone slabs as integral, animate, and vital (e.g., Just Reference Just2005) yet nonroyal aspects of their communities. Unfortunately, the scarcity of information about small, uncarved Postclassic stelae, particularly the uncertainty about their surface decoration and lack of associated excavations, makes it difficult to substantiate this idea.

Conclusion

New information about two small, uncarved Postclassic stelae at Punta Laguna offers some insight into these monuments. The areas adjacent to these stelae were likely locations for ceremonies conducted by individuals or small groups. The monuments’ contexts were diverse. Perhaps most notably, both stelae were associated with the final deposition of hundreds of mixed fragments of previously broken and now unreconstructable Chen Mul modeled anthropomorphic incense burners. This association is perhaps not surprising, given that both censers and stelae are understood as axes mundi and as integral aspects of calendric ceremonies.

Understanding small uncarved stelae as miniatures is useful. Doing so reframes their creation as a purposeful choice rather than as an act of necessity, suggests they are a legitimate rather than anomalous type of monument, and encourages scholars to eschew conventional considerations of what these monuments lack and focus instead on what they retain. Further, by offering a more nuanced understanding of small, uncarved Postclassic stelae, this article reinforces and builds on scholarship emphasizing the Postclassic as a time of “cultural reinvention and reorganization” (Ardren Reference Ardren2015:75) and one critical to understanding “political formations that have overcome early statehood preoccupations with divine kings and big monuments” (Masson Reference Masson2000:7; see also Masson Reference Masson, Hendon, Joyce and Overholtzer2021; Rice Reference Rice, Arnauld and Breton2013; Sabloff Reference Sabloff2007; Sabloff and Rathje Reference Sabloff and Rathje1975).

Such reconsiderations of the Postclassic period, in turn, raise broader questions about a long-standing archaeological concern: the relationship between scale and complexity. Joyce Marcus (Reference Marcus, John and Richard2003:115) has articulated and cogently critiqued several enduring archaeological assumptions, including that “monumentality equals power” and that “the bigger the monument, the more powerful the ruler or government that commissioned it.” As noted at the outset of this article, some older work (e.g., Webb Reference Webb1964:572–584) and recent reconsiderations of monumentality (e.g., Hutson Reference Hutson2023; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Triadan, Vázquez López, Fernandez-Diaz, Omori, Belén Méndez Bauer and Melina García2020; Rosenswig and Burger Reference Rosenswig, Burger, Richard and Robert2012) directly challenge such assumptions. Several, for example, note that monumental construction projects can and do occur in the absence of strong political hierarchies, and therefore they caution against equating “monumentality a priori with the presence of political power” (Rosenswig and Burger Reference Rosenswig, Burger, Richard and Robert2012:6; see Hutson Reference Hutson2023:370). Others, particularly Malcolm Webb, question whether the size and state of contemporary ruins speak to their degree of architectural advancement. For Webb (Reference Webb1964:579), “It was the defects of Classic architecture . . . that made them so permanent: thick walls, small chambers, few doors” and the advances of Postclassic architecture, including the increased use of wooden beams, that made subsequent structures more susceptible to eventual collapse and thus less impressive to twentieth-century archaeologists.

Much like these and other considerations of monumentality, consideration of miniaturization also challenges assumptions about the relationship between scale and complexity. Just as monumentality need not imply centralized rulership, miniaturization need not imply sociopolitical decline. Indeed, “poorer ruins do not a poorer civilization make” (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson and Lope2014:25).

Acknowledgments

The Punta Laguna Archaeology Project is codirected by David Rogoff and members of the Punta Laguna community, including Serapio Canul Tep and Mariano Canul Aban. All work has been conducted with the permission of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), and excavations associated with the Durazno and Iguana stelae were carried out under Oficio 401.1S.3-2022/863. I would like to thank Arthur Joyce and Nicholas Puente, as well as three anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and advice.

Funding Statement

The National Science Foundation, the National Geographic Society, the American Philosophical Society, the Gerda Henkel Foundation, and the University of Colorado Boulder have generously funded archaeological fieldwork at Punta Laguna. Fieldwork associated with the small, uncarved stelae at Punta Laguna was supported by a National Science Foundation Senior Archaeological Research Grant (BCS-1725340) and by the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Competing Interests

The author declares none.