The Middle East comprises 15 countries: Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Yemen. Currently, there is a population of more than 500 million (2025) in the region, which faces a mounting burden of mental illness that increasingly demands robust legal and policy responses. 1 The region’s complex sociopolitical landscape, marked by conflict, displacement and widespread trauma, exacerbates vulnerabilities to mental illness and substance use. At the same time, cultural stigma and religious norms often impede help-seeking behaviour.

Mental disorders are among the leading causes of disability globally, accounting for over 14% of the global burden of disease and disproportionately affecting low- and middle-income countries. Reference Vigo, Thornicroft and Atun2 In the Middle East, the prevalence of mental illness is compounded by protracted conflict, displacement, economic hardship and weak health systems. Recent data indicate that the Middle East is facing a significant mental health crisis, with rates of mental illness ranging from 15.6 to 35.5%. Reference Ibrahim and Laher3

Mental health law is crucial for safeguarding the human rights of individuals with mental disorders. Its objectives include preventing human rights violations and discrimination, promoting autonomy and personal freedom, and establishing minimum standards for mental health services. Despite growing recognition of mental health as a public health priority, legal frameworks in the Middle East remain underdeveloped and poorly aligned with international norms. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities advocates for a shift towards individual autonomy, community-based care and protection from coercion, principles that are still lacking in much of the region. Reference Althani, Alabdulla, Latoo and Wadoo4 Additionally, the implementation of rights-based mental health legislation across the Middle East has been slow and inconsistent. Although some countries, such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Qatar, Kuwait and the UAE, have enacted national mental health laws in the past two decades, others either rely on outdated legal frameworks or lack comprehensive legislation altogether. Reference Althani, Alabdulla, Latoo and Wadoo4 Where legal frameworks exist, enforcement remains a significant challenge owing to inadequate oversight, limited resource allocation and a lack of community-based alternatives to institutional care.

This paper aims to addresses these gaps by critically analysing the development and implementation of mental health legislation in Middle Eastern countries. It provides an insight into the current state and challenges of reform, identifies the structural and contextual obstacles to enforcement, and showcases best practices for rights-based mental health reform in the region.

Method

This review offers an overview of mental health legislation across Middle Eastern countries. Data collection occurred between February and April 2025. Sources were identified through a search of PubMed, Google Scholar, Google and official government or legal websites. In instances where peer-reviewed publications were scarce, supplementary sources such as official Ministry of Health portals, World Health Organization (WHO) reports and grey literature were utilised to ensure the inclusion of the most current legal frameworks. Only information available in English was considered.

For each country, the following variables were extracted: the existence of mental health legislation, the year of enactment, the year of the most recent revision and any additional relevant legal or policy information. To ensure accuracy, two authors independently reviewed all data, resolving any discrepancies through discussion and verification against the original source documents.

Current status of mental health legislation

In the Middle East, mental health legislation varies significantly: some countries have robust, recently enacted statutes, whereas others lack dedicated legal frameworks entirely. The WHO Mental Health Atlas 2020 reports that only 8 out of 15 Middle Eastern countries (53%), namely Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, the UAE, Israel, Lebanon and Iraq, have mental health legislation that aligns with international human rights standards. The other countries (Bahrain, Palestine, Syria, Iran, Oman, Jordan and Yemen) do not have a dedicated mental health act. 5 This gap between legislative intent and practical application reveals broader structural and political challenges in mental health governance. Reference Althani, Alabdulla, Latoo and Wadoo4 The following sections examine the status in selected Middle Eastern countries, highlighting key legislative features, gaps and emerging trends.

Countries with recent legislative reforms

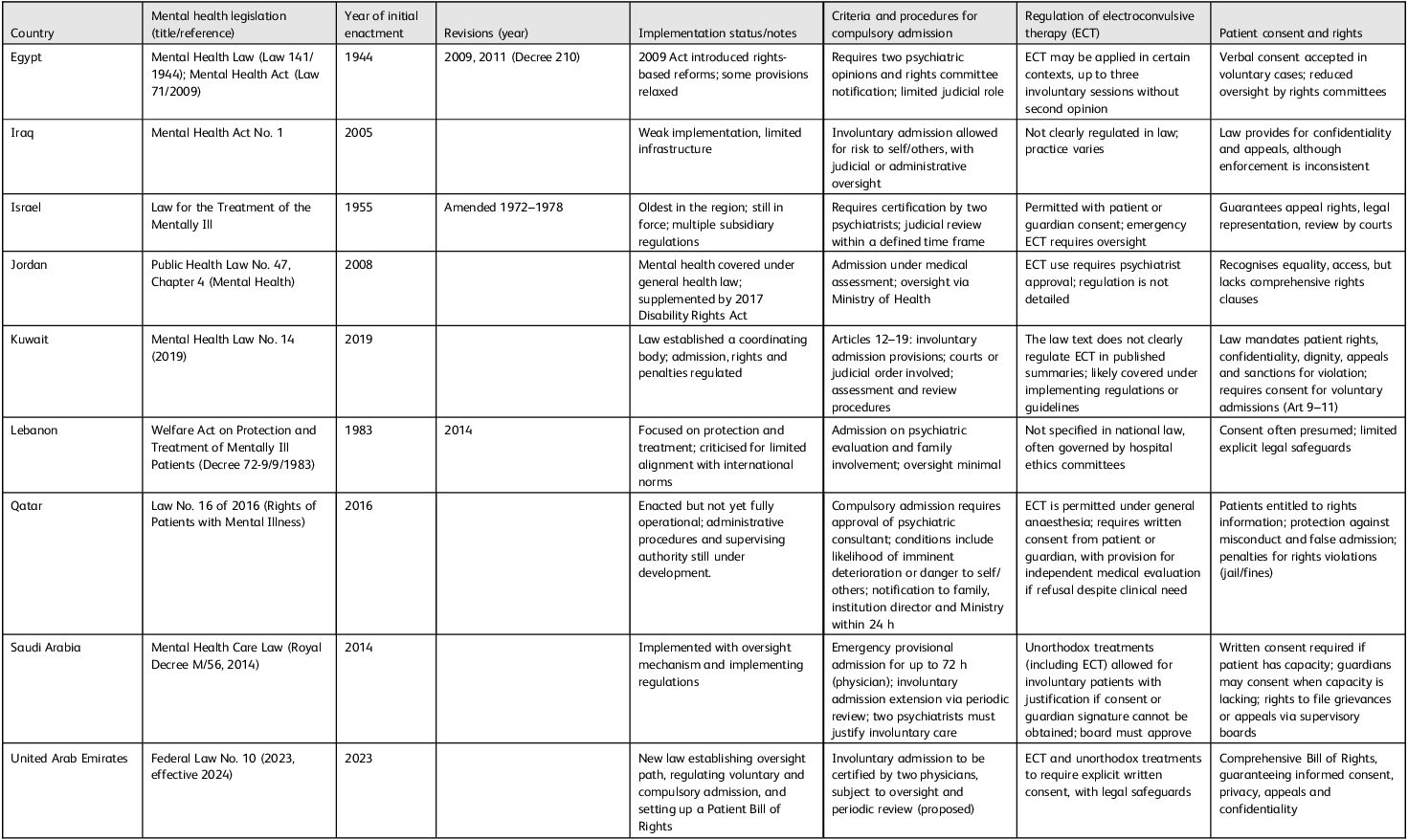

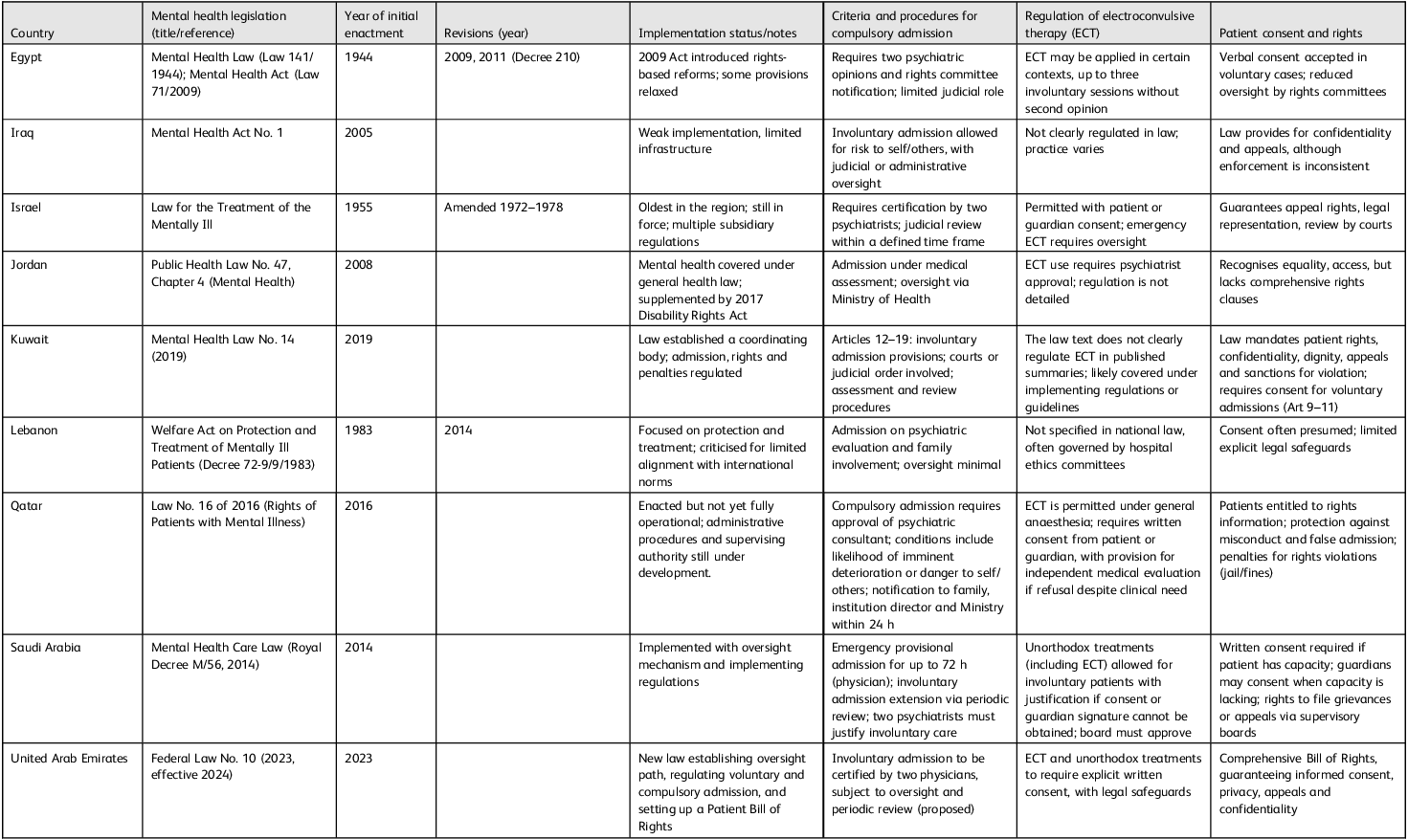

Several Middle Eastern countries have progressively reformed their mental health legislation (Table 1). Israel enacted its foundational law in 1958, which remains in effect today. Reference Levav and Grinshpoon6 Lebanon followed with Legislative Decree No. 72 in 1983, which focuses on care and protection, but has been criticised for not meeting international standards. Reference Levav and Grinshpoon6 Iraq’s Mental Health Act No. 1, implemented in 2005, remains poorly enforced. 7 Egypt’s first formal Mental Health Act, enacted in 1944 (Law 141/1944), was a groundbreaking piece of legislation approved by the Egyptian Parliament. It regulated the involuntary detention of psychotic patients and introduced essential safeguards, including second medical opinions, consent to treatment and appeal mechanisms. Reference Okasha and Karam8 This Act was one of the earliest codified mental health laws in the Arab and African regions, laying the groundwork for future reforms. Subsequently, the Mental Health Act of 2009 (Law 71) modernised the framework to align with international human rights standards; however, its broadening of powers for involuntary treatment has raised ongoing concerns about patient autonomy. Reference Loza and El Nawawi9 Saudi Arabia introduced a rights-based law in 2014. Reference Carlisle10 Qatar’s Law No. 16, established in 2016 and influenced by the WHO Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS), emphasises patient rights and procedural safeguards. Reference Wadoo, Althani, Latoo and Alabdulla11 Kuwait’s 2019 law introduced community treatment orders, and the UAE’s Federal Law No. 10, which took effect in May 2024, establishes a comprehensive legal framework. Reference Alhassani and Osman12

Table 1 Mental health legislation in Middle Eastern countries

Countries lacking dedicated mental health laws

Several Middle Eastern countries still lack dedicated mental health legislation. Yemen exemplifies this legislative void, where ongoing conflict, institutional collapse and economic instability hinder both legal reform and service delivery. Palestine faces similar issues; mental healthcare is regulated by the 2004 Public Health Law and general disability legislation, which offer limited provisions for compulsory treatment and weak protections for patient rights. In Syria, despite more than a decade of efforts to draft new legislation, no new mental health law has been ratified, leaving the country dependent on outdated 1981 regulations that lack modern rights-based safeguards. Oman and Bahrain are in the process of developing mental health legislation as part of broader health governance initiatives, yet services still operate under provisional or outdated frameworks. Jordan presents a partial model: although it lacks a stand-alone mental health act, psychiatric admissions are governed by Chapter 4 of Public Health Law No. 47/2008. The 2017 Disabilities Rights Act supplements the existing legislation. Iran lacks a stand-alone mental health law. The limited provisions from 1997 address rights, competency and guardianship, but protections are dispersed throughout civil, penal and family laws.

Gaps in existing frameworks

Despite legislative advancements in several Middle Eastern countries, significant gaps remain in the structure, implementation and oversight of mental health laws. First, many legal frameworks prioritise institutional care while inadequately regulating community-based services, which undermines continuity of care.

Second, oversight mechanisms (for example review boards, judicial panels and human rights commissions) aim to monitor involuntary admissions, compulsory treatment and interventions such as electroconvulsive therapy. However, many of these bodies lack statutory independence, have limited professional expertise and operate with inadequate funding. This undermines their ability to review cases rigorously, enforce compliance and hold institutions accountable. Reference Althani, Alabdulla, Latoo and Wadoo4 When functioning effectively, these mechanisms can safeguard against arbitrary detention, ensure due process and strengthen patient rights. Unfortunately, across much of the region, their role tends to be more symbolic than substantive.

Furthermore, forensic psychiatry remains underdeveloped, despite the increasing overlap between mental health and criminal justice systems. This leaves standards for diversion, treatment in custodial settings and post-release supervision unclear.13 The mental health needs of children and adolescents are often overlooked, with few jurisdictions implementing provisions that consider minors’ developmental and consent capacities. Procedural safeguards in involuntary treatment, such as the right to appeal, automatic periodic reviews and statutory limits on detention, are applied inconsistently, leaving patients vulnerable to prolonged confinement and violations of their rights.

Finally, in fragile and conflict-affected states, the enactment of legislation has not led to the development of effective operational systems, rendering legal protections largely ineffective. These shortcomings underscore the urgent need for coordinated rights-based reforms that align statutory provisions with real-world practices. Without such alignment, mental health legislation risks perpetuating rather than alleviating systemic inequities in psychiatric care.

Challenges and opportunities for mental health reform

Challenges

Mental health legislation in the Middle East region must be viewed within the broader sociopolitical, cultural and legal contexts that shape it. In many countries, ongoing conflict, political instability and weak governance hinder the implementation of legal protections, even where such legislation exists. For instance, Syria, Yemen and Palestine face systemic enforcement barriers due to fragile state capacity, disrupted health systems and competing national priorities.13 This situation underscores the gap between legislative intent and practical application, where laws often become more symbolic than operational.

Cultural and social factors also influence the adoption and enforcement of mental health legislation. Stigma surrounding mental illness, reliance on family-based decision-making, and religious interpretations can all affect the realisation of legal protections in practice. Reference Althani, Alabdulla, Latoo and Wadoo4 These dynamics may deter individuals from seeking help, limit the assertion of patient rights and perpetuate paternalistic approaches to psychiatric treatment. The legal traditions in the Middle East region are diverse, encompassing civil law, Sharia-based frameworks and hybrid systems. This legal heterogeneity affects how mental health legislation is drafted, interpreted and enforced.

Opportunities

Despite these challenges, there are emerging opportunities for reform. Legislative updates in Egypt (2009) and Saudi Arabia (2014) illustrate the potential for developing regionally adapted frameworks that balance clinical care with rights-based protections. 7,Reference Alhassani and Osman12 Future reforms could align with broader initiatives to strengthen health systems, such as integrating mental health into primary care and promoting universal health coverage. Technological innovations like telepsychiatry also offer promise for enhancing access, facilitating oversight and ensuring compliance with legal standards. Additionally, regional bodies such as the WHO Eastern Mediterranean region and national psychiatric associations are well positioned to provide technical support, advocacy and policy guidance.

In conclusion

The legal landscape for governing mental healthcare in the Middle East is highly uneven, ranging from progressive reforms to a complete lack of legislation. Although some states have enacted recent laws that demonstrate a commitment to rights-based care, challenges such as poor implementation, weak oversight and insufficient community services hinder their effectiveness. In conflict-affected and resource-limited areas, legal protections often remain more aspirational than practical. To promote equitable and effective mental healthcare, regional frameworks must evolve from mere formal enactment to enforceable, culturally relevant and system-integrated legislation. It is crucial to align legal standards with international human rights instruments and ensure their practical application to protect the dignity, autonomy and clinical needs of individuals with mental illness.

Author contributions

S.A.-H.: conceptualisation; investigation; writing – original draft, review and editing; supervision; project administration. S.M.Y.A.: writing – review and editing.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.