Introduction

Workplace conditions are becoming increasingly important, since those conditions influence workers’ health and well-being, which may ultimately affect absenteeism and job satisfaction (Im, Chung & Yang, Reference Im, Chung and Yang2018). At the workplace, employees can be exposed to several risks, such as carcinogens, air pollution, noise and radiation, and the level of exposure to these risks has a substantial influence on their health and well-being (Ji, Pons & Pearse, Reference Ji, Pons and Pearse2018; WHO, 2012).

To overcome those risks, occupational prevention measures and training are needed, and several international entities, e.g. the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and World Health Organization (WHO), have developed various guidelines, programmes and manuals to be used as examples by organizations. Companies must also comply with legislation regarding occupational safety, employee training, workplace conditions and so on (Aryal, Parish & Rohlman, Reference Aryal, Parish and Rohlman2019; IAEA, 2018; WHO, 2018a). Prior studies concluded on the association between indoor environmental quality in workspaces and employees’ health, well-being, productivity and absenteeism (Ji et al., Reference Ji, Pons and Pearse2018; Singh, Syal, Grady & Korkmaz, Reference Singh, Syal, Grady and Korkmaz2010; Wyon, Reference Wyon2004).

Controlling risks associated with exposure to radiation in the workplace and training workers to be aware of mitigation procedures are of major importance for employees’ health and well-being and consequently job satisfaction (Dos Santos Grecco, Vidal, Cosenza, Dos Santos & de Carvalho, Reference Dos Santos Grecco, Vidal, Cosenza, Dos Santos and de Carvalho2014; Schmidt & Willis, Reference Schmidt and Willis2007). Prevention programmes and measures are therefore crucial to improve health, reduce absenteeism, and foster employees’ knowledge and awareness. Such initiatives can embrace Health and Safety programmes, Worksite Wellness Programmes, safety equipment and measures (Schwatka et al., Reference Schwatka, Smith, Weitzenkamp, Atherly, Dally, Brockbank and Newman2018).

Following this debate, prevention and safety are important to ensure employees’ occupational safety and can be a useful tool to prevent or at least lower the number of accidents and injuries sustained at work. Several initiatives have been described in the literature reinforcing items that are job-related (working time, workload, satisfaction at work, work stress, tasks, and employment type), individual (smoking and drinking habits, working period, education, income, personality, age, gender, and race), workplace-related (physical, musculoskeletal, chemical, and biological risk issues), and organization-related (work group size, management support, and workplace safety status) (Park, Jung & Sung, Reference Park, Jung and Sung2019).

This study contributes to the literature by addressing an empirical gap stemming from the lack of research adopting an integrative approach to workplace conditions while also incorporating the often-overlooked role of gender interactions. It examines the effects of workplace conditions on job satisfaction, paying particular attention to environmental, occupational safety, and social factors, as well as their gender-related dynamics.

Indeed, several factors mentioned above may affect job satisfaction, namely environmental factors (e.g. temperature, humidity, lighting, radiation, and noise), motivational factors (recognition, nature of work and repetitiveness of tasks, sense of achievement from work, opportunities for personal growth and responsibility granted), psychosocial (interpersonal relations, co-workers and supervisors), and economic variables (salary and benefits) (Aziri, Reference Aziri2011; Bakotić & Babić, Reference Bakotić and Babić2013; Hanaysha & Tahir, Reference Hanaysha and Tahir2016; Ijadi Maghsoodi et al., Reference Ijadi Maghsoodi, Azizi-ari, Barzegar-Kasani, Azad, Zavadskas and Antucheviciene2018; Leitão, Pereira & Gonçalves, Reference Leitão, Pereira and Gonçalves2019, Reference Leitão, Pereira and Gonçalves2021; Özsoy, Uslu & Öztürk, Reference Özsoy, Uslu and Öztürk2014; Raziq & Maulabakhsh, Reference Raziq and Maulabakhsh2015).

More satisfied employees are more committed, comply better with safety-related practices, and are more productive (Ayim Gyekye, Reference Ayim Gyekye2005). Accordingly, job satisfaction affects life satisfaction and happiness positively (Lera‐López, Ollo‐López & Sánchez‐Santos, Reference Lera‐López, Ollo‐López and Sánchez‐Santos2018). Job satisfaction influences in a positive or negative way several domains of organizational life, such as employees’ performance, productivity, absenteeism, loyalty, and commitment (Aziri, Reference Aziri2011; Bakotić & Babić, Reference Bakotić and Babić2013; Schaumberg & Flynn, Reference Schaumberg and Flynn2017).

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. A literature review leads to formulating a conceptual model and research hypotheses, followed by presentation of the research methodology. The subsequent section discusses the results, and the paper concludes by considering its main findings, limitations, and practical implications.

Literature review, research hypotheses, and conceptual model proposal

Environmental workplace conditions

In the workplace, employees may be exposed to some health risks, such as air pollution, noise, risk of injuries and hazardous chemicals, as well as biological agents, ergonomic and psychosocial stressors. The level of exposure to these risks has a substantial influence on employees’ health and well-being (Ji et al., Reference Ji, Pons and Pearse2018; WHO, 2012). Several studies show that environmental workplace conditions such as noise, lighting and temperature, influence employee health, attitudes, behaviours, satisfaction, and performance (Bakotić & Babić, Reference Bakotić and Babić2013; Ji et al., Reference Ji, Pons and Pearse2018; Kottwitz, Schade, Burger, Radlinger & Elfering, Reference Kottwitz, Schade, Burger, Radlinger and Elfering2018; Lee & Brand, Reference Lee and Brand2005; Salonen et al., Reference Salonen, Lahtinen, Lappalainen, Nevala, Knibbs, Morawska and Reijula2013). The examination of temperature, relative humidity, and CO2 data in combination offers pertinent insights into the comfort of indoor environments, while tackling concerns regarding ventilation, carbon dioxide concentration, and health (Balvís, Sampedro, Zaragoza, Paredes & Michinel, Reference Balvís, Sampedro, Zaragoza, Paredes and Michinel2016).

Thus, the indoor environment may affect employees’ health and well-being. It must be underlined that air quality has a considerable effect on their health and productivity either positively or negatively. Temperature also has a significant effect on workers’ health, as extreme temperatures may cause fatigue, circulatory system diseases such as altered blood pressure, and productivity (Ji et al., Reference Ji, Pons and Pearse2018; Roelofsen, Reference Roelofsen2002; Soriano, Kozusznik, Peiró & Mateo, Reference Soriano, Kozusznik, Peiró and Mateo2018).

As described in the literature, employees need to feel safe and comfortable in their work environment, since a comfortable working environment has a positive influence on organizational performance (Biron & Bamberger, Reference Biron and Bamberger2012; Ellis & Pompili, Reference Ellis and Pompili2002; Roelofsen, Reference Roelofsen2002).

In industries, merging Internet of Things (IoT) technologies with monitoring systems that measure temperature, sound levels, air quality, and gas leaks provides a noteworthy solution for workers’ health and safety. Suryawanshi et al. (Reference Suryawanshi, Garje, Ghodake, Nadar, Ingle and Shaikh2024) developed a system with multiple sensors which were synchronized to optimize data collection, with notification alerts that allowed management of optimal environmental conditions.

Soto-Castellón, Leal-Costa, Pujalte-Jesús, Soto-Espinosa and Díaz-Agea (Reference Soto-Castellón, Leal-Costa, Pujalte-Jesús, Soto-Espinosa and Díaz-Agea2023) found that environmental workplace conditions such as high noise levels and poor lighting are related to higher levels of mental workload, which may affect workers’ well-being, and consequently, job satisfaction.

Several studies have found that distinct parameters of environmental workplace conditions (temperature, humidity, lighting, radiation, noise, and radiation) and safety climate influence workers’ job satisfaction (Aziri, Reference Aziri2011; Bakotić & Babić, Reference Bakotić and Babić2013; Hanaysha & Tahir, Reference Hanaysha and Tahir2016; Ijadi Maghsoodi et al., Reference Ijadi Maghsoodi, Azizi-ari, Barzegar-Kasani, Azad, Zavadskas and Antucheviciene2018; Özsoy et al., Reference Özsoy, Uslu and Öztürk2014; Raziq & Maulabakhsh, Reference Raziq and Maulabakhsh2015). A good work environment (physical environment, lighting, noise, and workplace design) and pleasant working conditions (safe conditions and safety equipment) may increase employees’ job satisfaction (Parvin & Kabir, Reference Parvin and Kabir2011). Employee training also positively influences job satisfaction and employees’ commitment (Hanaysha & Tahir, Reference Hanaysha and Tahir2016).

Scholars have verified that indoor environmental quality (IEQ) in workspaces affects employees’ health, well-being, productivity and absenteeism. IEQ may also have a negative effect on employees’ health, for example, asthma and respiratory allergies, through poor air quality, extreme temperatures, excessive humidity and insufficient ventilation, and psychological health, such as depression and stress, through inadequate lighting, acoustics and ergonomic design (Ji et al., Reference Ji, Pons and Pearse2018; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Syal, Grady and Korkmaz2010; Wyon, Reference Wyon2004). Thus, the following research hypotheses are considered:

(H1a): Employees who work under favourable workplace environmental conditions, such as proper ventilation, are more satisfied at work.

(H1b): Employees who work under favourable workplace environmental conditions, such as proper noise conditions, are more satisfied at work.

(H1c): Employees who work under favourable workplace environmental conditions, such as proper ergonomic conditions, are more satisfied at work.

Although employees are not consciously aware of it, they are often exposed to several artificial and natural sources of radiation that present a truly silent risk to their health. Radiation utilized in medicine comes from both natural and artificial sources, including cosmic rays, radioactive particles present in the air, soil, water, and nuclear industry emissions (IAEA, 2009; UNSCEAR, 2010; WHO, 2018a).

The biggest sources of radiation are medical applications of radiation. This includes interventional radiology, nuclear medicine, diagnostic radiology, and radiotherapy, with radon and its decay products being the biggest source of exposure to natural radiation (Vimercati et al., Reference Vimercati, Fucilli, Cavone, De Maria, Birtolo, Ferri and Lovreglio2018).

The biological radiation effects, on tissue or organs, depend on the radiation dose, type of radiation and the biological material itself, but the WHO and USEPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency) categorize radon as one of the important causes of lung cancer, second after smoking (WHO, 2018a, 2018b). The excitation and ionization that occur when ionizing radiation is absorbed in biological material are distributed non-randomly along specific pathways. Depending on the radiation quality, the spatial distribution of these ionization/excitation events caused by various particles varies significantly (Burgio et al., Reference Burgio, Piscitelli and Migliore2018; UNSCEAR, 2009).

Several factors influence indoor radon concentration in private buildings and workplaces, not only the type of building and building materials, but also environmental factors such as wind speed, humidity, ventilation, temperature, and pressure (Visnuprasad, Jaikrishnan, Sahoo, Pereira & Jojo, Reference Visnuprasad, Jaikrishnan, Sahoo, Pereira and Jojo2018).

Regarding the workplace, a variety of workplaces, including mines, plants, medical facilities, research and educational institutions, and nuclear fuel facilities, are responsible for occupational exposure to ionizing radiation. The same applies to underground or aboveground work environments that supply or use significant volumes of groundwater, such as spas and facilities for the treatment and distribution of groundwater. Research has shown that exposure to radiation at work and the resulting chromosomal aberrations increase the risk of cancer in nuclear workers (Djoković et al., Reference Djokovic, Jankovic, Milovanovic and Bulat2023). Additionally, compared to non-exposed professionals, healthcare personnel exposed to low doses of ionizing radiation have a higher incidence of chromosomal abnormalities and are more vulnerable to changes in the thyroid’s normal function (Cioffi et al., Reference Cioffi, Fontana, Leso, Dolce, Vitale, Vetrani, Galdi and Iavicoli2020; Djoković et al., Reference Djokovic, Jankovic, Milovanovic and Bulat2023).

It is critical to identify workplaces where worker exposure to ionizing radiation needs to be regulated in order to maintain occupational health and safety. Implementing longer biological rest periods, regular health surveillance appointments, and providing workers with access to adequate protective equipment and training initiatives to help them understand and manage exposure risks are just a few of the mitigation measures that must be taken to ensure safety and security in the workplace (Cioffi et al., 2020; IAEA, 2004, 2018).

Monitoring such risks is therefore vital for employees’ health and well-being, correlated with job satisfaction, through employing best practices and foreseeing vulnerabilities. These need to be capable of promoting procedures and policies that significantly change how well employees perform in terms of safety (Dos Santos Grecco et al., Reference Dos Santos Grecco, Vidal, Cosenza, Dos Santos and de Carvalho2014; Schmidt & Willis, Reference Schmidt and Willis2007).

Other studies find an association between safety culture attributes and measures targeted at safety performance, identifying a set of safety procedures and attitudes in workplaces that deal with high-risk activities and are involved in complex environments, while keeping excellent safety control and performance (Donald & Canter, Reference Donald and Canter1994; INSAG, 1991; Jacobs & Haber, Reference Jacobs and Haber1994; T. Lee, Reference Lee1998; Obadia, Vidal & E Melo, Reference Obadia, Vidal and E Melo2007; Olson, Osborn, Jackson & Shikiar, Reference Olson, Osborn, Jackson and Shikiar1986). Considering the previous literature, the following research hypothesis is formulated:

(H1d): Employees whose employers regularly monitor radiation in the workplace are more satisfied at work.

Occupational safety conditions: Prevention, training and safety

Employers and employees alike must prioritize safety because it is essential to ensure workers’ occupational safety (Dos Santos Grecco et al., Reference Dos Santos Grecco, Vidal, Cosenza, Dos Santos and de Carvalho2014). To safeguard employees against disease and injury, every business must include training in its safety and health programmes, since this type of training programme improves awareness of workplace safety and knowledge. It is important for all employees, but especially young ones, since the latter are more prone to work injuries, because of their inexperience and lack of knowledge about hazards associated with the workplace (Aryal et al., Reference Aryal, Parish and Rohlman2019).

Safety training on workplace hazards and equipment are essential to guarantee employees’ safety in their respective occupations, assisting them in developing their skills so they can be ready to carry out their responsibilities more effectively (Catton, Shaikhi, Fowler & Fraser, Reference Catton, Shaikhi, Fowler and Fraser2018), which will have a beneficial impact on employee behaviour (Hanaysha & Tahir, Reference Hanaysha and Tahir2016).

Concerning ionizing radiation, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), International Labour Organization (ILO) and WHO, have developed several manuals, guidelines, and programmes, namely the Practical Radiation Safety Manuals, the Occupational Radiation Protection Safety Guide, International Radiation Basic Safety Standards (BSS) and the Practical Radiation Technical Manual (IAEA, 2004, 2018; WHO, 2018a). A new international BSS was adopted by the WHO in 2012 and is being implemented in EU member states (WHO, 2018a).

Being well-informed about the risks and safety measures associated with radiation exposure is crucial for employees’ health and well-being (Allam, Algany & Khider, Reference Allam, Algany and Khider2024).

The effect of instructional programmes on improving radiation safety procedures among healthcare personnel has been the subject of numerous articles and studies, with positive findings, including greater knowledge, better adherence to safety protocols and fewer incidents of radiation exposure, emphasizing the advantages of consistent and continuous education in safety compliance (Behzadmehr, Doostkami, Sarchahi, Dinparast Saleh & Behzadmehr, Reference Behzadmehr, Doostkami, Sarchahi, Dinparast Saleh and Behzadmehr2021).

Safety equipment and practices, safety training and safe design, are implemented as preventive measures. Safety shielding equipment, such as lead aprons, lead gloves, eye goggles, and thyroid shields, when used regularly, provides protection to the bone marrow (NG & SA, Reference NG and SA2020).

Safety design promotes safety using an original design to reduce hazards and decrease risks. This reduces the need for safety by trial and error, procedures, or other administrative controls. In the US, this technique was part of an initiative called the ‘Prevention through Design’ programme, which consisted of ‘designing out’ workplace hazards to prevent occupational harm and mortalities (Horberry & Burgess-Limerick, Reference Horberry and Burgess-Limerick2015).

Ergonomic workstation design prioritizes the ability to modify posture and prevent prolonged static posture, as both standing and sitting for long periods can have detrimental effects on health (Dempsey et al., Reference Dempsey, Kocher, Nasarwanji, Pollard and Whitson2018).

Prevention programmes and measures, such as Health and Safety programmes, Worksite Wellness Programmes, safety equipment and measures, are used to improve health benefits, reduce absenteeism, and foster employee knowledge and awareness (Schwatka et al., Reference Schwatka, Smith, Weitzenkamp, Atherly, Dally, Brockbank and Newman2018).

Regarding radon, workplace managers must undertake preventive measures such as increasing under-floor ventilation systems, and in the workplace, sealing floors and walls. Other mitigation processes, for radon detection in basements or on a solid floor, is the installation of a radon sump crock system and avoiding the transfer of radon from those areas to other parts of the building (Olson et al., Reference Olson, Osborn, Jackson and Shikiar1986).

According to Mariani et al. (Reference Mariani, Vignoli, Chiesa, Violante and Guglielmi2019), workplace safety is now characterized as a component of work systems replicating the (low) probability of physical damage to employees, property, or the environment during work performance, whether the damage occurs immediately or over time. Previous research shows that employees’ risky behaviour accounts for more than 80% of all reported accidents (Bayram et al., Reference Bayram, Pokorná, Ličen, Beharková, Saibertová, Wilhelmová, Prosen, Karnjus, Buchtová and Palese2022). Safety is the lack of accidents, which implies that workers are shielded from mishaps (Jaju et al., Reference Jaju, Kurian and Ravikanth2018).

Several issues may be associated with accidents and occupational harm. These can be job-related (working time, workload, job satisfaction, job stress, occupation, and employment type), individual (smoking, drinking, working period, education, income, personality, age, gender, and race), workplace-related (physical, musculoskeletal, chemical, and biological risk issues), and organization-related (work group size, management support, and workplace safety status) (Park et al., Reference Park, Jung and Sung2019).

Adamopoulos and Syrou (Reference Adamopoulos and Syrou2022) highlight the complex interplay between workplace safety, occupational health and job satisfaction. To increase safety and lessen risks, these authors advocate the application of control measures, the use of protective gear, and instructional training, with the ultimate goal of enhancing services and strengthening the workforce.

Safety legislation has been developed continuously, recognizing that employers are mainly responsible for employees’ safety. Safety regulations and organizational status have been established and specific regulations apply to several categories of hazards and activities (Jørgensen, Reference Jørgensen2016). Correctly designed work conditions encourage synergies between safety and ergonomics, health, environment, and quality (SHEQ) for structural self-control (Dirkse van Schalkwyk & Steenkamp, Reference Dirkse van Schalkwyk and Steenkamp2017). A safety culture is also important at the organizational level, this being associated with workers’ awareness of safety practices and procedures (Thurston & Glendon, Reference Thurston and Glendon2018). Considering the previous literature, the following research hypotheses are derived:

(H2a): Employees whose workplaces provide regular training on safety are more satisfied at work.

(H2b): Employees whose workplaces provide safety equipment are more satisfied at work.

(H2c): Employees whose workplaces provide safety conditions for machinery are more satisfied at work.

(H2d): Employees whose workplaces provide regular prevention on radon are more satisfied at work.

Job satisfaction and social conditions

The notion of job satisfaction is not a simple one; rather, it is multidimensional and subject to various interpretations (Aziri, Reference Aziri2011). For Locke (Reference Locke and D1976), higher job satisfaction corresponds to a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experience. There are numerous definitions, and extensive research has been conducted on the topic of job satisfaction (Ijadi Maghsoodi et al., Reference Ijadi Maghsoodi, Azizi-ari, Barzegar-Kasani, Azad, Zavadskas and Antucheviciene2018; Özsoy et al., Reference Özsoy, Uslu and Öztürk2014).

Several factors may influence job satisfaction, such as motivational factors (recognition, the nature of work, the sense of achievement from work, opportunities for personal growth, and the responsibility granted), psycho-social (interpersonal relations, co-workers, and supervisors), work environmental conditions (temperature, humidity, lighting, radiation, and noise) and economic variables (salary and benefits) (Aziri, Reference Aziri2011; Bakotić & Babić, Reference Bakotić and Babić2013; Hanaysha & Tahir, Reference Hanaysha and Tahir2016; Ijadi Maghsoodi et al., Reference Ijadi Maghsoodi, Azizi-ari, Barzegar-Kasani, Azad, Zavadskas and Antucheviciene2018; Leitão et al., Reference Leitão, Pereira and Gonçalves2021, Reference Leitão, Pereira and Gonçalves2019; Naderi & Shams, Reference Naderi and Shams2020; Özsoy et al., Reference Özsoy, Uslu and Öztürk2014; Raziq & Maulabakhsh, Reference Raziq and Maulabakhsh2015). In addition, Kawada and Otsuka (Reference Kawada and Otsuka2011) reported that job satisfaction was negatively associated with mental workload (Kawada & Otsuka, Reference Kawada and Otsuka2011).

Concerning social factors, providing social spaces and social support at work is important in influencing job satisfaction, according to an expanding body of research. Break-out rooms, lounges, and open interaction areas are examples of social spaces viewed as strategic components that encourage the development of supportive organisational cultures and strong interpersonal connections.

Formal and informal social support at work is positively correlated with job satisfaction, according to previous empirical studies, such as Garmendia, Fernández-Salinero, Holgueras González and Topa (Reference Garmendia, Fernández-Salinero, Holgueras González and Topa2023), who state that social support at work, such as chances for co-workers to socialise and unwind, directly boosts job satisfaction and acts as a protective barrier against emotional tiredness. According to the same authors, social interactions and leisure opportunities – which are frequently made possible by thoughtfully planned communal spaces – lead to happier, healthier workers. It is critical to promote such interactions for both employee wellbeing and organisational sustainability.

Research on workspace design also shows a strong correlation between social elements and workplace satisfaction. Lusa, Käpykangas, Ansio, Houni and Uitti (Reference Lusa, Käpykangas, Ansio, Houni and Uitti2019) and Dia (Reference Dia2024) showed that job satisfaction and workplace well-being are substantially correlated with a positive environment among co-workers, which is frequently made possible by easily available social areas. Their results demonstrate that critical factors, such as trust, encouragement, and open communication – collectively known as social capital – are essential in understanding the variance in job satisfaction. Satisfaction with the ease of interacting with co-workers – again, a feature bolstered by social areas – was especially high in multi-space or open-plan workplaces, and was linked to improved mental health, recuperation at work and a lower risk of burnout.

Employees with jobs marked by highly repetitive tasks, routines and monotonous work tend to be less satisfied at work. Accordingly, Ackermann-Liebrich, Martin and Grandjean (Reference Ackermann-Liebrich, Martin and Grandjean1979) found significant correlations between routinized jobs and lack of autonomy, as well as psycho-somatic disturbances, such as pain and stress, and thus lower job satisfaction. In the same direction, Johansson (Reference Johansson1989) found a direct association between job monotony and psychological stress, anxiety and depression, all having a negative effect on wellbeing.

With increased job autonomy and variation in tasks, employees feel less demotivated, as highlighted by Melamed, Ben-Avi, Luz and Green (Reference Melamed, Ben-Avi, Luz and Green1995), who found a direct correlation between objective measures of repetitive work and psychological distress, work dissatisfaction, and subjective monotony. Routinized tasks and repetitiveness proved to be associated with job boredom and abandon.

In this connection, job satisfaction positively influences life satisfaction and happiness (Lera‐López et al., Reference Lera‐López, Ollo‐López and Sánchez‐Santos2018). Job satisfaction influences either positively or negatively several domains of organizational life, such as employees’ performance, productivity, absenteeism, loyalty, and commitment (Aziri, Reference Aziri2011; Bakotić & Babić, Reference Bakotić and Babić2013; Schaumberg & Flynn, Reference Schaumberg and Flynn2017).

Aligned with previous findings, the following research hypotheses are considered:

(H3a): Employees who have access to social areas in their companies are more satisfied at work.

(H3b): Employees with more repetitive work are less satisfied at work.

Conceptual model of analysis

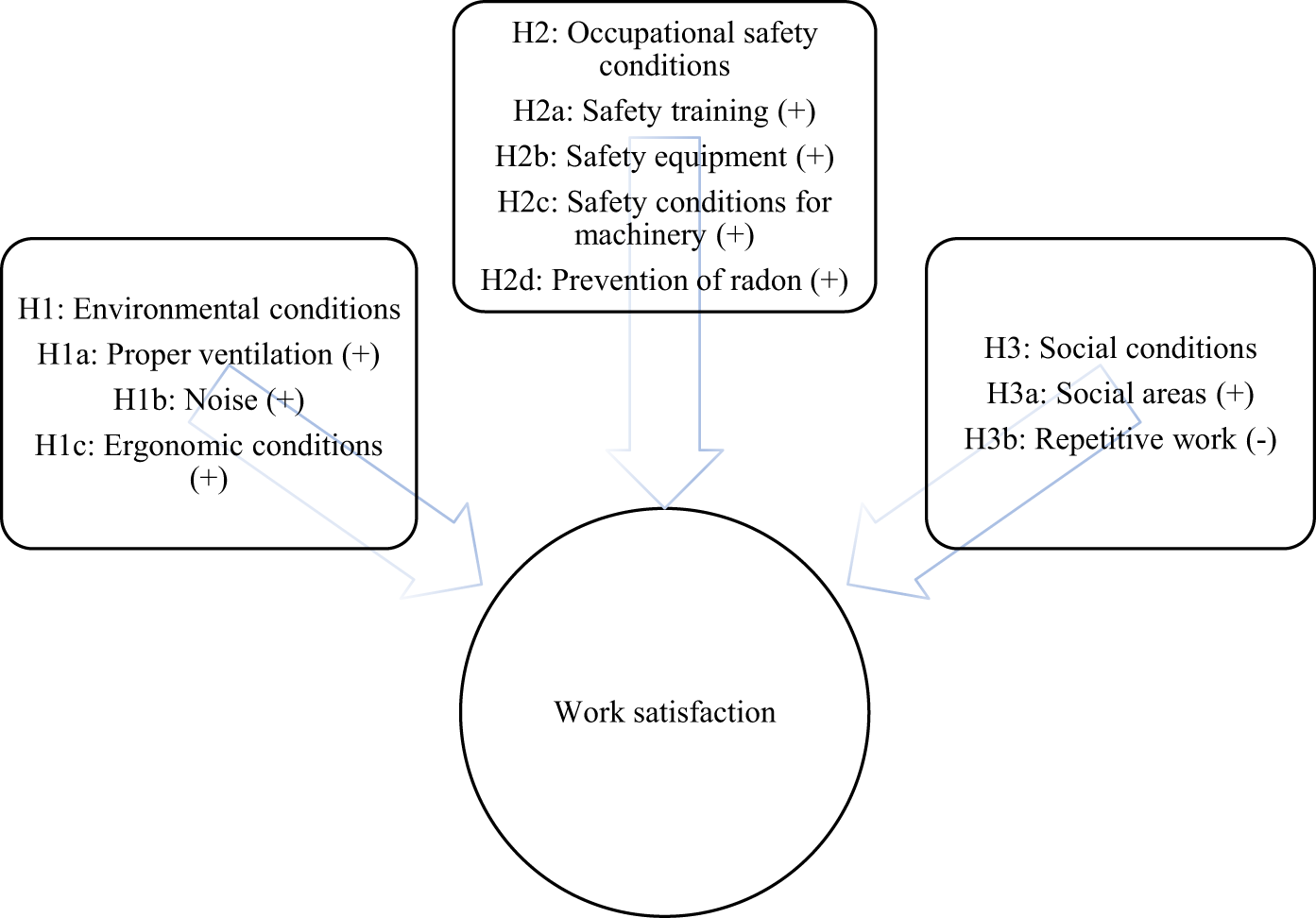

Drawing on the above literature review, Fig. 1 proposes a conceptual analysis model that aims to identify the factors influencing job satisfaction based on a list of factors, specifically environmental, occupational safety, and social conditions, including research hypotheses.

Figure 1. Environmental, occupational safety and social workplace factors and workers’ job satisfaction: Proposed conceptual model of analysis.

Materials and methods

Participants

The data used in the current study were collected during an Erasmus strategic partnership (2017–2019), involving 12 expert organizations from 6 Southern European countries (Italy, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Portugal, and Spain), which carried out a survey to assess workplace Health, Well-being and Quality of work life. The study was conducted between April and July 2018. The sample covers 15 private companies and 5 public entities or large firms per partner, involving 2 employees per organization and totalling 514 questionnaires. It was not intended to interview either company owners or general managers to avoid bias in the responses.

Survey instruments

The research methodology was developed based on different questionnaires used to carry out surveys on health and wellbeing in the workplace, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Survey questionnaires: Benchmarks

Source: Own elaboration.

We applied a convenience sample procedure on an aleatory basis. A contact person was identified in each organization to ensure completion of the questionnaire, which was then validated or not by the research team. The questionnaires were applied by personal interviews to ensure the necessary response rate.

The partners followed the instructions to select the interviewees as presented hereafter: 15 companies among micro, small and medium-sized units (10% of interviewees for each category, according to the EU definition of SME), plus 5 among Large Firms and Public Entities.

Measurement

The questionnaire includes two sections: Health in the workplace (ionizing radiation, radon, workplace environmental conditions and safety) and sample characterization (gender, age, position in the organization, type of employee contract, employee qualifications, and organization’s sector of activity, size, and age). For the first section, workers were asked 12 questions, and all variables were measured on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ which was afterwards converted into binary. For the sample characterization section, we used levels of answer.

Data were analysed using STATA 17 software, and P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Then, discrete choice regression models, namely Probit, Logit and Cloglog regressions, were run on the seven models, to evaluate the set of environmental workplace conditions that may influence workers’ job satisfaction.

Empirical analysis

Sample characterization

Sample as a whole

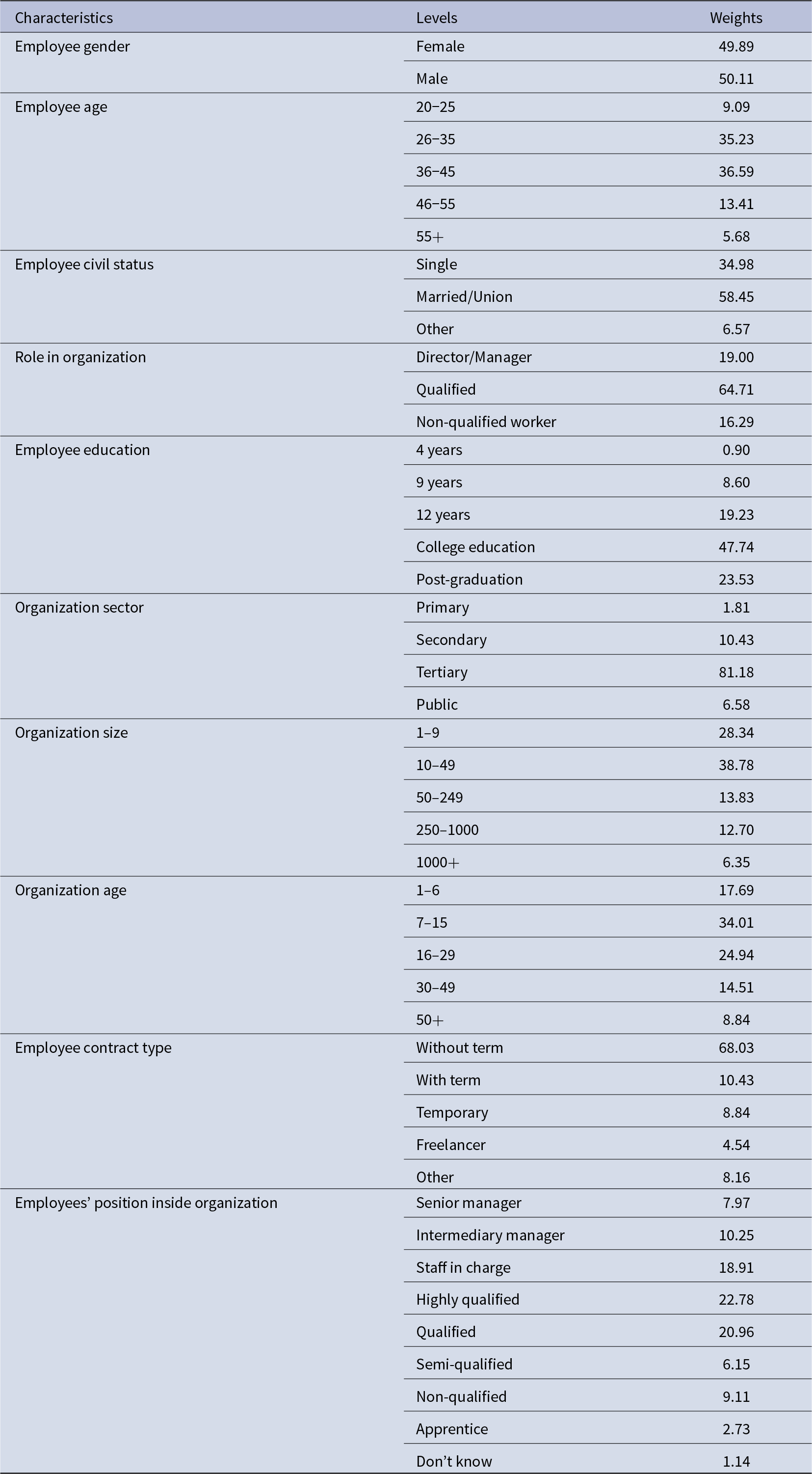

In this study, 514 questionnaires were analysed. Table 2 describes the main characteristics of the sample. 50% of respondents are women, the majority between 26 and 45 years old, 13% between 46 and 55 and only 6% are older than 55. Furthermore, 35% are single, 58% are married and 65% have a qualified role in the organization. Most of the interviewees have a college or post-graduate degree. 81% work for the tertiary sector and most work in small and medium companies, which have existed on average between 7 and 15 years. Almost 68% are permanent staff.

Table 2. Sample characterization

Source: Own elaboration.

Employees’ perceptions of the workplace conditions reported are presented below in Table 3. The most satisfied workers are Italians followed by Spaniards, with Bulgarians being absent most often. Radon monitoring and prevention in companies is more regular in Portugal and Italy. Portuguese and Spanish workers were found to be the most satisfied with ventilation, lighting and noise levels, with the Portuguese and Italians expressing more satisfaction with work temperature and humidity levels. Cypriot and Greek employees were the most satisfied with the existence of resting/eating areas at the workplace. Italian and Portuguese were the most satisfied with safety training practices and the existence of sufficient safety equipment at work. Portuguese and Bulgarians showed great satisfaction with workplace safety maintenance. When questioned about exposure to extreme heat or cold in their workplaces, Greek respondents were the most unsatisfied. Cypriot and Bulgarian workers were most unsatisfied with the repetitiveness of their tasks.

Table 3. Workplace conditions: employees’ perceptions

Source: Own elaboration.

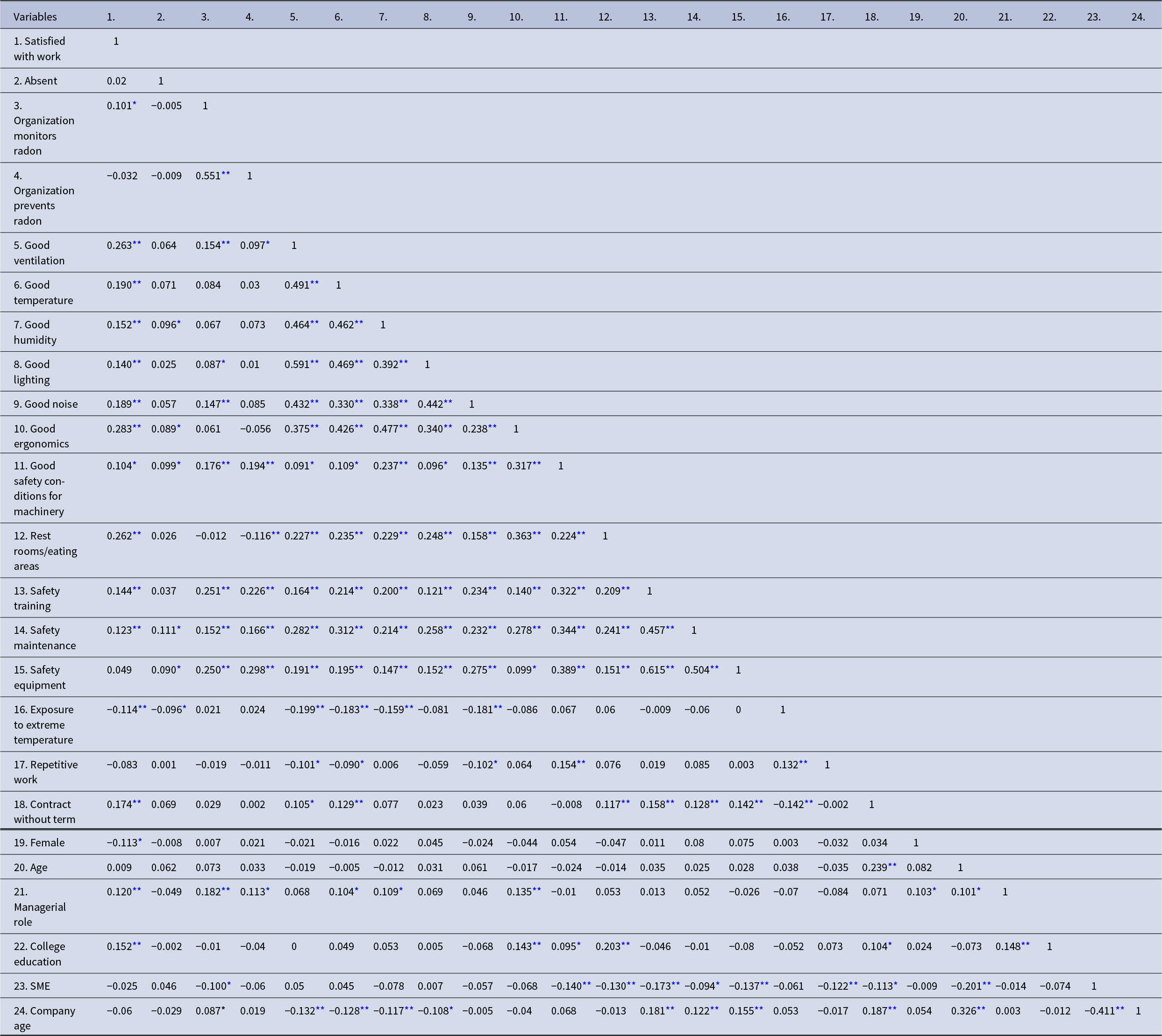

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

In descriptive terms, it is observed that for the employees consulted the items with which they agree most in their workplaces are appropriate ventilation, temperature and lighting. Moreover, having sufficient safety equipment, safety training and rest rooms/eating areas are also of major importance, as seen in Table 4.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics

Source: Own elaboration.

The coefficients presented in Table 5, representing the correlations matrix, reveal that the items that are positively associated with satisfaction at work are the fact that their company regularly monitors the presence of radon, working with acceptable levels of ventilation, temperature, humidity, lighting, noise, ergonomic conditions, safety conditions for machinery, safety training and maintenance, having enough rest rooms/eating areas, being permanent staff, assuming a managerial role and having a college education. Conversely, workers’ exposure to extreme temperatures and being female are negatively associated with satisfaction at work.

Table 5. Correlations matrix

* Source: Own elaboration.* Significant correlations at 0.05 (2 tails);

** Significant correlations at 0.01 (2 tails).

Discrete choice regression models

The variables presented above were used in estimating the discrete choice regression models (i.e. Logit, Probit, and Cloglog), considering seven model specifications, to evaluate the set of environmental workplace factors that may influence workers’ job satisfaction.

There are two justifications for using the model specifications: (i) estimation of each of the seven discrete choice models for the whole sample is justified by using a dependent variable represented in binary terms, which can determine the probability of the influence of a hypothetical set of independent variables arising from the literature review presented above; the dependent variable taking the value of 1 when employees say they are satisfied at work and 0 otherwise; and (ii) estimation of the models: (1–3), which emphasise environmental and working conditions. The primary predictors show a substantial correlation with satisfaction, and are highly significant; models (4–6), which include interaction terms between workplace characteristics and gender to see if women are affected differently. Some gender interactions, such as female and ergonomic conditions, as well as female and safety equipment, reveal subtle complexity and become crucial, primarily in Logit; and in the complete model (7), which incorporates contract type, demographic controls, and all workplace characteristics. The primary determinants are still strong and statistically significant, but additional factors including being female, having a permanent contract, and having a college degree also stand out.

Firstly, concerning the probit model, it takes the following form:

Here, ![]() ${{\chi}_k}$ represents the set of explanatory variables.

${{\chi}_k}$ represents the set of explanatory variables.

Secondly, regarding the logit model, it is represented by the following:

Here, F(z) = e z/(1 + e z) is the cumulative logistic distribution; and ![]() ${{\chi }_k}$ represents the full set of explanatory variables representing environmental work conditions, namely: Organization monitors radon; Organization prevents radon; Good ventilation; Good temperature; Good humidity; Good lighting; Good noise; Good ergonomics; Good safety conditions for machinery; Rest rooms/eating areas; Safety training; Safety maintenance; Safety equipment; Exposure to extreme temperature; Repetitive work; Female; Age; Managerial role; College education; Contract without term; and SME.

${{\chi }_k}$ represents the full set of explanatory variables representing environmental work conditions, namely: Organization monitors radon; Organization prevents radon; Good ventilation; Good temperature; Good humidity; Good lighting; Good noise; Good ergonomics; Good safety conditions for machinery; Rest rooms/eating areas; Safety training; Safety maintenance; Safety equipment; Exposure to extreme temperature; Repetitive work; Female; Age; Managerial role; College education; Contract without term; and SME. ![]() $k$ represents the number of regressors considered in the analysis, using a Probit for estimating

$k$ represents the number of regressors considered in the analysis, using a Probit for estimating ![]() $\beta j$ using maximum likelihood standard methods.

$\beta j$ using maximum likelihood standard methods.

Thirdly, the Cloglog model is expressed by the following:

Here, H(z) = 1 – exp {−exp(z)}; and ![]() ${{\chi }_k}$ represents the set of explanatory variables.

${{\chi }_k}$ represents the set of explanatory variables.

Results and discussion

Based on the proposed conceptual model of analysis (see Fig. 1), which incorporates the research hypotheses to assess environmental, occupational safety, and social workplace factors influencing job satisfaction, a total of 514 valid questionnaires were retained for empirical analysis. The results of the discrete choice regression estimations – namely the probit, logit, and cloglog models – are presented below (see Models 1, 2, and 3 in Table 6).

Table 6. Models 1, 2, and 3 – Job satisfaction determinants: the role of environmental, occupational safety, and social workplace conditions

* Legend: *P < .10.

** P < .05.

*** P < .01. Standard errors in brackets.

Source: Own elaboration.

Concerning model fitness, and as regards the likelihood ratio Chi2 probability, all models are jointly significant at P < 0.01, suggesting strong explanatory power. In addition, the standard errors and significance are reasonable and the achieved statistical significance patterns indicate confident estimates.

Model 1 only considers important environmental aspects of the workplace, such as adequate ventilation and ergonomics. Both variables demonstrate significant positive relationships with job satisfaction across Probit, Logit, and Cloglog assessments, highlighting the fundamental significance of ergonomic office design and decent air quality. This first model emphasises how much fundamental physical surroundings influence employees’ satisfaction, with noise and other environmental elements appearing to have less of an impact.

When including factors related to occupational safety and training, Model 2 expands the study. Employees appreciate having the right information and the ability to remain safe at work, as shown by the fact that safety training is a notably positive and significant predictor of satisfaction. However, in certain circumstances, safety equipment shows a negative or mixed effect, indicating potential discontent with a device or its perceived inconvenience. This approach emphasises the complex function of safety precautions, showing that while training is revealed to be good, equipment quality or implementation may need to be improved.

Through variables like social spaces and repetitive labour, Model 3 incorporates social conditions and task characteristics into the research. The importance of communal spaces for support and engagement is confirmed by research showing that social areas have a strong, highly significant beneficial impact on satisfaction. On the other hand, tedious or routine duties are a consistently negative and substantial predictor of job satisfaction. Crucially, ergonomics and adequate ventilation continue to have a beneficial impact here, demonstrating their resilience as essential workplace conditions.

Models 4, 5, and 6 (see Table 7) examine how gender and workplace variables interact to see if some elements have different effects on men and women. According to these models, women seem to gain more from the availability of safety equipment and ergonomic advancements, which have favourable interaction impacts, especially in Logit specifications. Furthermore, based on notable favourable interactions, the detrimental effects of repetitious employment are substantially mitigated for women. These results demonstrate that although fundamental workplace motivators are the same for both sexes, focused ergonomics and safety interventions can increase employee happiness, especially for female workers.

Table 7. Models 4, 5, and 6 – job satisfaction determinants: the role of interaction between gender and workplace conditions

* Legend: *P < .10.

** P < .05.

*** P < .01. Standard errors in brackets.

Source: Own elaboration.

The most complete specification is Model 7, which includes demographic controls including gender, age, managerial job, education level, and contract type in addition to all workplace characteristics (see Table 8). The findings support the ongoing significance of social and physical aspects, with college education and permanent contracts also showing up as significant positive drivers. When other factors are taken into account, being a woman independently predicts greater levels of job satisfaction, although age and managerial role do not significantly affect this relationship. The strongest explanatory power is provided by this whole model, which presents a comprehensive picture of the factors influencing employee satisfaction, including environment, training, social context, gender, and job security.

Table 8. Model 7 – Job satisfaction determinants: The complete model with demographic controls

* Legend: *P < .10.

** P < .05.

*** P < .01. Standard errors in brackets.

Source: Own elaboration

The effects with a more substantial and favourable impact on job satisfaction are compiled in Table 9.

Table 9. The effects of workplace conditions on job satisfaction: Main findings

Source: Own elaboration.

According to the above, the main determinant of job satisfaction for the workplace environment variables is proper ventilation, showing a consistent positive and statistically significant effect in all models, concluding that good ventilation is strongly connected with higher work satisfaction. Moreover, for ergonomic conditions, we found strong, robust, and positive effects, as attention to workplace ergonomics is clearly associated with more satisfied workers.

Social areas show a strong, highly significant beneficial effect when added (Models 3, 6, and 7), suggesting that these spaces are essential for satisfaction. More repetitive work lowers satisfaction, which is a negative and important finding. Apart from routine radiation monitoring and safety equipment, which occasionally show relevance in certain specifications, the impacts of noise, radiation monitoring, safety equipment, and radon prevention are inconsistent or negligible.

In relation to occupational safety and training, when incorporated, safety training has a favourable and significant impact, supporting training investment as a driver of satisfaction. For safety equipment, the coefficient is more often negative and sporadically significant, which could indicate that users are dissatisfied with the equipment they already have or find it burdensome to operate. Regarding safety requirements for equipment, there is a beneficial impact, but frequently not very pronounced.

When analysing gender interactions (female x workplace factors), the results show that female x ergonomic conditions are occasionally positive and significant, more in Logit models. These findings point out that women may benefit more from improved workplace ergonomics. For female x safety equipment, we found positive, statistically significant effects in some models, suggesting that providing safety equipment can increase satisfaction, especially for women. We did not find any special effects in female x safety training. However, we found a positive association in female x repetitive work, in Model 6, indicating that the negative effect of repetitive work is less important for women. As for the remaining interactions, our results show that the majority are not significant, denoting that gender does not affect the bulk of workplace factor effects.

From analysis of the effects when adding control variables (Model 7), some are noteworthy. Being female is associated with higher work satisfaction, even when controlling for other covariates. Age and managerial role do not show significant associations. Highly educated workers are in general more satisfied, and workers that have job security (permanent contract) are also more satisfied.

Aligned with these results, job satisfaction can be raised by providing appropriate safety training and improving the physical working environment, including social areas, ergonomics, and ventilation. It may be especially beneficial to pay close attention to women’s ergonomic and safety equipment needs. Other significant satisfaction levers are less repetitive work and more job stability (e.g. open-ended contracts). A summary of the most robust effects, taking as reference the complete Model 7, is presented in Table 10.

Table 10. Summary of most robust effects in the complete model 7

*** Note: (P-value); Range of effects: High:***1% significance level;

** Moderate:**5% significance level; Low:

* 10% significance level.

Source: Own elaboration.

With some variations by gender, primarily in the areas of ergonomics and safety, our analysis reveals compelling evidence that job security and observable workplace changes are important for job satisfaction purposes. Physical and social settings are particularly powerful levers for businesses looking to increase employee satisfaction.

Although the emphasis, magnitude, and robustness of specific effects vary, the three models – Probit, Logit, and Complementary Log-Log (Cloglog) – used across seven model parameters all consistently predict work satisfaction.

The outcomes of the three discrete choice regression models, that is, Probit, Logit, and Cloglog, are very consistent. In all model types and specifications, variables such as adequate ventilation, ergonomic conditions, and social areas (if included) are statistically significant and positive predictors. Likewise, there is a continuous and considerable unfavourable correlation with repetitive work.

Every model type exhibits extremely significant likelihood ratio chi-square tests (P < 0.01), suggesting that they all contribute to a good explanation of job satisfaction. These joint significance tests show that the explanatory power of the models in each method is comparable. A summary of the most robust effects with gender interactions, considering Models 4 to 6, is presented in Table 11.

Table 11. Summary of the most robust effects in models 4, 5, and 6, with gender interactions

*** Note: (P-value); Range of effects: High: ***1% significance level;

** Moderate: **5% significance level;

* Low: *10% significance level; n.s. non-significant.

Source: Own elaboration.

The physical work environment (ventilation, ergonomics, and social spaces) is the most consistent set of important aspects when examining the major trends highlighted across all models. In the most comprehensive models, there is also a considerable contribution from education level (college education) and work stability (people with permanent contracts). Another significant drawback is the repetitive nature of work.

As the purpose of the study was to assess the relationship between environmental work conditions and workers’ job satisfaction, considering three main axes, namely work environmental conditions, safety conditions and social conditions, next we will discuss the main results in the lens of the 3-level approach.

Regarding the first axis, workplace environmental conditions, it is important to highlight the level of satisfaction with some parameters presented to the interviewees, such as proper ventilation, acceptable levels of noise, ergonomic conditions, and regular monitoring of radon levels.

The ventilation coefficient is positive and statistically significant at the 5% or 1% levels in all models (Models 1, 3, 4, 6, 7) incorporating adequate ventilation (e.g. in Model 1 Probit: 0.424***; in Model 7 Probit: 0.362**). This result means we cannot reject H1a: increased work satisfaction is regularly and strongly correlated with improved ventilation.

In all models, when including ergonomic conditions, they are a strong, positive, and highly significant predictor of satisfaction (e.g. Model 1 Probit: 0.616***; Model 3 Probit: 0.621***; Model 7 Probit: 0.416***). Thus, H1c is not rejected according to the findings of this research.

However, none of the models (e.g. Model 1 Probit: 0.198, not significant; Model 7 Probit: 0.232, not significant) includes a statistically significant variable regarding noise conditions. Despite having a positive coefficient, the lack of significance suggests there is no strong, discernible correlation between contentment and beneficial noise conditions in this dataset. Therefore, H1b is rejected.

As for the coefficients for regular radiation monitoring, they are positive but only reach statistical significance in the full Model 7 (Probit: 0.435*; Logit: 0.728*; Cloglog: 0.446**). In the remaining models, radiation monitoring is not significant. This suggests some weak evidence in favour, but the effect is not as robust as for ventilation or ergonomics. Overall, H1d is partially supported – the positive association only emerges once controls are included.

These results partially corroborate prior studies that associate workplace environmental conditions such as lighting and temperature with employees’ health, attitudes, behaviours, satisfaction, and performance, apart from noise control (Bakotić & Babić, Reference Bakotić and Babić2013; Ji et al., Reference Ji, Pons and Pearse2018; Kottwitz et al., Reference Kottwitz, Schade, Burger, Radlinger and Elfering2018; Lee & Brand, Reference Lee and Brand2005; Salonen et al., Reference Salonen, Lahtinen, Lappalainen, Nevala, Knibbs, Morawska and Reijula2013). In fact, others had come to similar conclusions, proving that for example certain indoor environments may affect employees’ satisfaction, such as air quality, or temperature impacting on workers’ health, fatigue, or circulatory system diseases (Ji et al., Reference Ji, Pons and Pearse2018; Roelofsen, Reference Roelofsen2002; Soriano et al., Reference Soriano, Kozusznik, Peiró and Mateo2018).

Regarding the safety conditions axis, regular training on safety in the workplace is positive and statistically significant whenever it is included (Models 2, 5, 7; Model 2 Probit: 0.487***; Model 7 Probit: 0.306*). H2a is hence well supported. Concerning the safety equipment coefficients, these are negative and occasionally statistically significant (e.g. Model 7 Probit: −0.282, not significant but negative; Model 5 Logit: −1.215***). This implies that the availability of safety gear is either unrelated to contentment or may even be connected to decreased satisfaction (perhaps because of discontent with the tools or the tasks that call for them). H2b is therefore not supported.

In intermediate models, machine safety conditions exhibit positive coefficients that are significant at the 10% or 5% level (e.g. Model 5 Probit: 0.514***; Model 7 Probit: 0.049, not significant). Nevertheless, when controls are included, the effect loses statistical significance and is not robust in fully controlled models. As a result, H2c has partial support – the relationship exists, although it is not always strong.

This is in line with prior studies (e.g. Parvin & Kabir, Reference Parvin and Kabir2011; Hanaysha & Tahir, Reference Hanaysha and Tahir2016). If the company provides safe conditions and applies preventive measures such as regular job specific safety training, and providing safety equipment, those actions are recognised by employees as motivational factors, i.e. organizations care about their workers’ safety, and as described in the literature, motivational factors may improve job satisfaction and workers’ engagement (Ayim Gyekye, Reference Ayim Gyekye2005; Aziri, Reference Aziri2011; Bakotić & Babić, Reference Bakotić and Babić2013; Hanaysha & Tahir, Reference Hanaysha and Tahir2016; Ijadi Maghsoodi et al., Reference Ijadi Maghsoodi, Azizi-ari, Barzegar-Kasani, Azad, Zavadskas and Antucheviciene2018; Özsoy et al., Reference Özsoy, Uslu and Öztürk2014; Raziq & Maulabakhsh, Reference Raziq and Maulabakhsh2015). It is noted that all statistical models confirm such conclusions, the logit, the probit, and the Cloglog.

Additionally, all models have negative and non-statistically significant radon prevention coefficients (e.g. Model 5 Probit: −0.376, ns; Model 7 Probit: −0.313, ns). This indicates there is no evidence to support the hypothesis – in our sample, regular radon prevention is not associated with increased satisfaction. Our findings are, thus, not in line with prior results suggesting that to maintain good occupational health and thus job well-being and satisfaction, it is important to identify, check and control workplaces where workers’ exposure to ionizing radiation presents a risk. Thus, we did not find support for previous research concluding that providing safe and secure conditions in the workplace through adequate protective equipment and training initiatives for workers to be able to deal with risks of exposure, is a priority (IAEA, 2004, 2018). These findings must be assessed in the light of the population under analysis. Our sample covers companies’ workers, highly qualified and essentially from the tertiary sector, service companies. As our population is not significantly exposed to radiation in the workplace, this may prevent an association between workplaces providing constant radiation monitoring and employees’ satisfaction levels.

Now, moving to social conditions and their associations with work satisfaction, in every model that includes this, access to social places is highly significant and significantly beneficial for employees’ satisfaction (e.g. Model 3 Probit: 0.776***; Model 7 Probit: 0.411***). This means we cannot reject H3a.

Conversely, strong evidence for H3b is provided by repetitive work, as the association is negative and statistically significant throughout (e.g. Model 3 Probit: −0.327**; Model 7 Probit: −0.334**).

Our findings corroborate a growing body of research, denoting that having social spaces and social support at work, along with a positive atmosphere, are significant elements that impact job satisfaction (Dia, Reference Dia2024; Garmendia et al., Reference Garmendia, Fernández-Salinero, Holgueras González and Topa2023; Lusa et al., Reference Lusa, Käpykangas, Ansio, Houni and Uitti2019). Psycho-somatic issues and demotivation are more likely to occur in workers whose professions involve a lot of repeated tasks, routines, and monotonous labour (Ackermann-Liebrich et al., Reference Ackermann-Liebrich, Martin and Grandjean1979; Johansson, Reference Johansson1989; Melamed et al., Reference Melamed, Ben-Avi, Luz and Green1995). Table 12 summarizes the findings concerning the research hypotheses.

Table 12. Research hypotheses: summary table

Source: Own elaboration.

Conclusions, limitations, and implications

Human capital is widely recognized as an organization’s most valuable intangible asset, serving as a key foundation for sustained long-term competitiveness and performance. Consequently, organizations must make deliberate efforts to foster a healthy work culture that prioritizes employees’ well-being and job satisfaction.

Research consistently demonstrates that job satisfaction enhances motivation and engagement while reducing turnover and absenteeism – both of which are critical to organizational efficiency. Sickness-related absenteeism is a significant financial burden, underscoring the importance of proactive strategies to promote workplace health and well-being. For management, prioritizing employee health and satisfaction is not merely a social responsibility but a strategic necessity to safeguard productivity and secure a sustainable competitive advantage.

In the current context, more attention must be paid toward how organizations can provide employees with a healthy working environment that supports well-being and long-term performance. Modern workplaces face critical challenges to workforce health, including demographic shifts such as aging populations, as well as the rising prevalence of chronic diseases and mental health concerns. Work-related stress and high absenteeism rates further exacerbate these issues, undermining both employee well-being and organizational effectiveness. Addressing these threats is therefore not only a matter of social responsibility but also a strategic need, as healthier, more engaged employees contribute to improved productivity, reduced costs, and enhanced organizational sustainability and competitiveness.

This study examined the relationship between workplace conditions and job satisfaction using data from the European Survey on Workplace Health, Wellbeing, and Quality of Work Life. A total of 514 workers from local companies and public organizations across six Southern European countries were interviewed.

The empirical findings reveal that the main environmental workplace determinants of job satisfaction are proper ventilation and ergonomic conditions. Ventilation consistently shows a positive and statistically significant effect across all models, confirming that better air quality is strongly associated with higher job satisfaction. Similarly, ergonomic conditions yield strong, robust, and positive effects, indicating that attention to workplace ergonomics contributes meaningfully to employee well-being.

Regarding occupational safety, we find that safety training consistently improves satisfaction, supporting investment in training as a critical driver. In contrast, the coefficient for safety equipment is frequently negative and only sporadically significant, which may suggest dissatisfaction with the equipment currently available or difficulties in using it. Requirements related to safety equipment tend to have a beneficial, though often only moderately significant, effect.

Social areas also have a strong and highly significant beneficial effect when included, underlining their importance for employee satisfaction. In contrast, repetitive work significantly reduces satisfaction, highlighting its detrimental role. Other factors – such as noise, radiation monitoring, safety equipment, or radon prevention – have largely inconsistent or negligible effects, aside from occasional statistical significance in certain model specifications.

Gender interactions (e.g. female × workplace factors) provide additional insights. The interaction between female and ergonomic conditions is occasionally positive and significant, particularly in Logit models, suggesting that women benefit more from ergonomic improvements. Similarly, female × safety equipment is positive and significant in some cases, implying that the provision of safety equipment enhances satisfaction among women. No significant effects were found for female × safety training. Interestingly, female × repetitive work shows a positive association, indicating that repetitive tasks may have a less negative impact on women than on men. Other gender-related interactions are mostly insignificant, suggesting that gender does not substantially alter the main effects of workplace variables.

Moreover, when control variables are added, being female is independently associated with higher job satisfaction. Age and managerial role do not show significant associations. Highly educated workers report greater satisfaction, while job security in the form of a permanent contract is also strongly linked to higher job satisfaction.

Notably, the findings suggest that job satisfaction can be substantially improved by investing in safety training and enhancing the physical work environment – specifically through better ventilation, ergonomic conditions, and social areas. Particular attention to women’s needs in ergonomics and safety equipment may yield additional gains. Other key levers include reducing repetitive tasks and strengthening job stability (e.g. permanent contracts).

A major limitation of this study is that the empirical findings primarily reflect workplace dynamics prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, they remain relevant in the current post-pandemic context, as the research addresses key environmental factors, including ventilation, ergonomic conditions, occupational safety, and social spaces, which are critical for hybrid organizations facilitating a safe and appealing return to the workplace for employees.

In addition, it should be noted that this is a cross-section analysis, rather than a longitudinal analysis that could detect causality effects between job satisfaction, environmental working conditions and workers’ absenteeism. Another limitation is related to the geographical scope of the survey, which is limited to six Southern European countries with certain cultural and regulatory characteristics and the predominant sectors of activity (i.e. services).

Our findings carry important implications for managers and professionals in facilities management, who should integrate evidence and interventions across multiple domains – environmental, occupational safety, social conditions, facilities design, and gender dynamics – to enhance organizational satisfaction, and consequently, performance. This involves prioritizing improvements in environmental factors, particularly ventilation and ergonomic conditions, while also recognizing and addressing the specific needs of female employees.

Future research will aim to broaden the geographical scope of the survey and include additional sectors of activity, allowing for wider comparisons and the identification of cross-sectoral patterns. Another important direction will be cross-continental analyses of regulatory frameworks and policies addressing gender needs, environmental conditions, occupational safety, social conditions, health, radiation exposure, and facilities management. Connecting these findings to a new labour productivity agenda grounded in job satisfaction, for both the public and private sectors, represents a promising avenue for exploration.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are due to the track chair and participants in the 8th EUTERP workshop|Optimising Radiation Protection Training, Malta, which took place in Malta, between 10 and 12 April 2019, for providing us with constructive feedback and positive incentives to improve presentation of the research result used as the empirical basis of this manuscript. The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT): NECE-UBI, Research Centre for Business Sciences, under project UIDB/04630/2020.

Author contributions

This research article was developed and written with substantial input from both authors. Data collection; Writing; Analysis (DP); Writing Edition; Analysis (JCCL); Data collection; Writing (SS).

Funding

The Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (Grants and NECE- UIDB/04,630/2020) provided financial support for this study. Recipient of the grant: João Leitão (jleitao@ubi.pt).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study in accordance with applicable European legislation and institutional requirements. The study was conducted outside the submitting author’s higher education institution. The research was funded under the R.E.NewAL. SKILLS project (Project No. 591,861-EPP-1-2017-1-IT-EPPKA2-SSA). The project’s governance structure established a quality‐assurance, evaluation and monitoring framework, culminating in the R.E.NewAL. SKILLS Contents Quality Plan (REC-QP), which defined shared content‐production quality standards (including questionnaire design), identified key partner-representative roles and performance targets. Two oversight bodies were constituted: (i) the General Assembly, the ultimate decision‐making and supervisory body of the consortium, chaired by the Lead Partner’s representative; and (ii) the Curriculum Committee (CC), which comprised Contents Quality Managers (CQMs) appointed by partner organisations and was responsible for quality control of project outputs (for example the survey questionnaire). The questionnaire design and data collection methodology received review and approval from the General Assembly, project partners and the CC, ensuring that data‐collection procedures, questionnaire compliance and anonymised data treatment adhered to ethical and quality standards; published results contain no entity‐identifying information. Finally, the outputs of the R.E.NewAL. SKILLS project were approved by the Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA), and the project was formally closed as successfully completed.