Introduction

The last decade has witnessed a significant increase in academic and journalistic interest in the United States Supreme Court’s “shadow docket.” This docket comprises all the decisions the Court makes other than through the “full” cases it hears via the merits docket (we return to a more precise definition shortly). The increased interest can be seen both in many legal academics’ criticism of the way the court has employed the shadow docketFootnote 1 and empirical researchers’ studies of various components of the shadow docket.Footnote 2 The debates over the use of the shadow docket have spilled over to the justices themselves; for example, dissenting from a 2021 decision denying injunctive relief from a Texas abortion statute, Justice Kagan wrote that “the majority’s decision is emblematic of too much of this Court’s shadow-docket decisionmaking—which every day becomes more unreasoned, inconsistent, and impossible to defend.”Footnote 3 Yet despite this explosion in interest, there exists no systematic database of the shadow docket.Footnote 4 In this paper we describe the creation of the first such database, which we hope will aid empirical researchers who are interested in studying the various components of the shadow docket. Specifically, we collect the complete set of the Court’s orders from the Journal of the Supreme Court and parse those orders to categorize every shadow docket decision the Court made between the 1993 and 2024 terms, including cert denials, injunctions, summary reversals, mandamus petitions, and grant, vacate, and remands (GVRs). As we explain below, both defining the shadow docket itself and categorizing individual actions involve some degree of subjectivity. With this in mind, we have made the complete code and data we used to create the database—as well as the final database itself—available at www.shadowdocketdata.com.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 discusses possible definitions of the shadow docket, as well as how we define it for the purposes of creating the dataset. Section 3 provides details on how we created the dataset. Section 4 discusses a few research agendas in judicial politics where the shadow docket dataset might shed some light on important existing questions; we also provide some basic preliminary descriptive statistics on some of these questions. Section 5 concludes.

Defining the shadow docket

The shadow docket is not a term that is officially used by the Supreme Court. Instead, the term was coined by the legal scholar William Baude in his 2015 article, “Foreword: The Supreme Court’s Shadow Docket.” More recently, the 2023 publication of Steven Vladeck’s book The Shadow Docket has helped push the importance of the shadow docket into wider journalistic and public attention.

Because the shadow docket is an unofficial concept, defining its precise boundaries is not a black-and-white exercise. It is perhaps easiest to start with what everyone agrees is not part of the shadow docket: the Court’s “merits” docket, which comprises the select set of cases in which the Court gives its full consideration, including oral arguments and signed opinions, often accompanied by separate opinions (both concurrences and dissents). By definition, such cases do not operate in the shadows, as they are accompanied by the maximum transparency that the Court operates under. Because the cases decided via the merits dockets are generally the vehicle the Court uses to make legal policy, those decisions have typically received the vast bulk of attention from politicians, legal practitioners, scholars, and the media. For example, the Supreme Court Database (i.e., the “Spaeth database”), which has been the workhorse dataset for empirical studies of the Court for several decades, primarily contains information on merits case (Spaeth et al. Reference Spaeth, Epstein, Nelson, Martin, Segal, Ruger and Benesh2024).

What then is in the shadow docket? In his 2015 paper, Baude defined it as a “range of orders and summary decisions that defy its normal procedural regularity” (Baude Reference Baude2015, 1). This is a rather narrow definition. It certainly includes things like summary reversals and cases on the Court’s “emergency docket,” such as when a president asks the Court to quickly intervene in an ongoing legal dispute.Footnote 5 But it would exclude more routine actions the Court takes in non-merits cases, including cert denials, inviting the solicitor general to file a brief, and grant, vacate, and remands (GVRs). By contrast, Vladeck views the shadow docket as comprising “the entire body of decisions the Supreme Court hands down through “orders”—which includes not just rulings on applications, but also rulings (1) granting or denying certiorari/leave to file an “original” suit; and (2) respecting motions (like motions to recuse).”Footnote 6

In the interests of erring on the side of over-inclusivity, we adopt the broadest possible definition of the shadow docket and define it as encompassing any order or decision the Court makes except the opinions in full merits cases.Footnote 7 Our logic for this choice is as follows. The way the database is set up (as we describe below), any interested user can choose their own shadow docket adventure—as described below, each action by the Court is labeled by action type to allow users to filter out particular types of shadow docket procedures they are interested in studying. If, for example, one does not think that certiorari decisions fall under the definition of the shadow docket, those orders can be quite easily dropped.Footnote 8 Finally, for each shadow docket action in the database, where applicable we connect (via docket numbers) every shadow docket action to the lower court that heard the case before it reached the Supreme Court, which should help researchers interested in studying how the shadow docket operates with respect to the judicial hierarchy.

Creating the dataset

To create the shadow docket database, we rely on the Journal of the Supreme Court of the United States. As described by the Court, the Journal contains “the disposition of each case, names the court whose judgment is under review, lists the cases argued that day and the attorneys who presented oral argument, contains miscellaneous announcements by the Chief Justice from the Bench, and sets forth the names of attorneys admitted to the Bar of the Supreme Court.” An entry appears in the journal for every day that the Court heard oral arguments or issued orders on pending cases. Importantly, the Journal only captures actions taken by the full court and not decisions made by individual justices, such as administrative stays; the latter are hence not included in our data collection.Footnote 9 Starting with the 1993 term, the Journal is posted in a text-based PDF format, which allows us to use text-processing tools to capture and classify the actions that comprise the shadow docket. Figure 1 depicts an example of what an order looks like in the journal—this particular order is a denial of a request for a stay in a death penalty case, along with a denial of cert.

Figure 1. An Example of a Shadow Docket Order.

We began by first separating each term into days. For each day, the Journal is divided into sections based on the following broad categories: Summary Disposition, Orders in Pending Cases, Certiorari Denied, Per Curiam, Habeas Corpus, Mandamus Denied, Prohibition Denied, Rehearings Denied, Attorney Discipline, Admission, Oral Argument, Opinion, Certiorari Granted, Motion Denied, and Jurisdiction Postponed.Footnote 10 We parsed each section into individual “docket-day” entries.Footnote 11 Each docket-day is accompanied by text describing which action(s) were taken with respect to that docket that day.

Sometimes, the court addresses multiple dockets at once. Specifically, the court will list multiple dockets and then describe the action that applies to all of them. For these dockets, we relied on the text of the “last” docket in the sequence, which contains the substance of the Court’s action. We then separated each order into individual actions. For example, a single docket-day entry might both grant a motion to proceed in forma pauperis and grant certiorari. This single entry contains two actions—the grant of the motion and the grant of certiorari. To capture each action, we divided the text into segments using phrases such as “the motion” or “the application.”Footnote 12 If the text contains multiple instances of one pattern or multiple patterns, each accompanying block of text is counted as a separate action. This process gives us a large set of docket-day actions. Figure 2 presents an example of such a multiple-docket order. In this instance, the Court denies several stay requests simultaneously, but only the last order notes explicitly what action the Court is taking across the set of connected orders.

Figure 2. Example of Multiple Dockets Being Implicated in the Same Order.

We assigned each action to one of 59 different categories using string searching. Note that these categories are not mutually exclusive; in some instances a single docket will fall into multiple categories. For example, an order that involves a GVR will be coded as both the “GVR” and “Certiorari,” since the “grant” component of the GVR is technically a cert grant. We looked for informative words and phrases and used the presence of these features to assign actions. Each action was assigned to only one action class using a decision tree. For each action, we then determined what decision the Court made using the same process. For example, if the action is “Certiorari,” we classify whether it is granted, denied, or dismissed. This approach categorizes over 99% of actions. The remaining actions were hand coded. The majority of hand-coded docket-day actions were either typos or did not contain one of the phrases needed to split the text into actions by the preprocessing code. The remaining actions belonged to classes that occurred relatively infrequently and thus were not picked up by the decision tree. The resulting dataset consists of more than 265,000 actions on 220,000 unique dockets and more than 100,000 admissions to the Supreme Court Bar. The total size of the dataset thus exceeds 370,000 orders, an average of more than 10,000 orders per term.

Table 1 provides a brief description of each of the categories (the codebook for the database contains more detailed descriptions), along with a count of how often each category appears in the data. Perhaps not surprisingly, cert petitions are easily the modal category, comprising about 56% of all shadow docket actions. The second most frequent activity is admissions to the bar, followed by requests for rehearings. On the other end of the spectrum, the Court very rarely does things like rule on requests to add materials to the record and to release a defendant from custody pending appeals.

Table 1. A Summary of the Action Classes in the Dataset. The last column depicts the total number of times each class appears in the data.

Research questions and descriptive results

How best to use the Shadow Docket Database will depend on one’s particular research needs. But in the interest of demonstrating how the database could enhance our broader understanding of judicial politics, in this section we sketch out a few areas where we think the dataset could provide answers to some existing puzzles or questions. Where relevant and available, we also present a few descriptive results that emerge immediately from the data that are tied to these questions.

The size of the Court’s docket

Perhaps the most widely known statistic about the Supreme Court is that its merits docket has decreased dramatically over the past half-century or so, to the point where the Court gives full consideration to fewer than 60 cases per term. It is also well appreciated that the Court now grants cert to a small fraction of all the cert petitions it receives (see, e.g., Liu and Kastellec (Reference Liu and Kastellec2023, 3) and Lane (Reference Lane2022)).

The empirical focus on the merits docket has led many scholars to seek to explain the steep drop in such cases over the past half-century (Hellman Reference Hellman1996; Stras Reference Stras2010; Owens and Simon Reference Owens and Simon2011; Heise, Wells, and Chutkow Reference Heise, Wells and Chutkow2019, see e.g.). But focusing only on merits cases is metaphorically studying the tip of the iceberg, given how few cases the Court gives full consideration to each term. Indeed, perhaps less well known is that after increasing steadily between around 1900 and 2000, the size of the Court’s overall docket has actually declined somewhat from its peak around 2005.Footnote 13

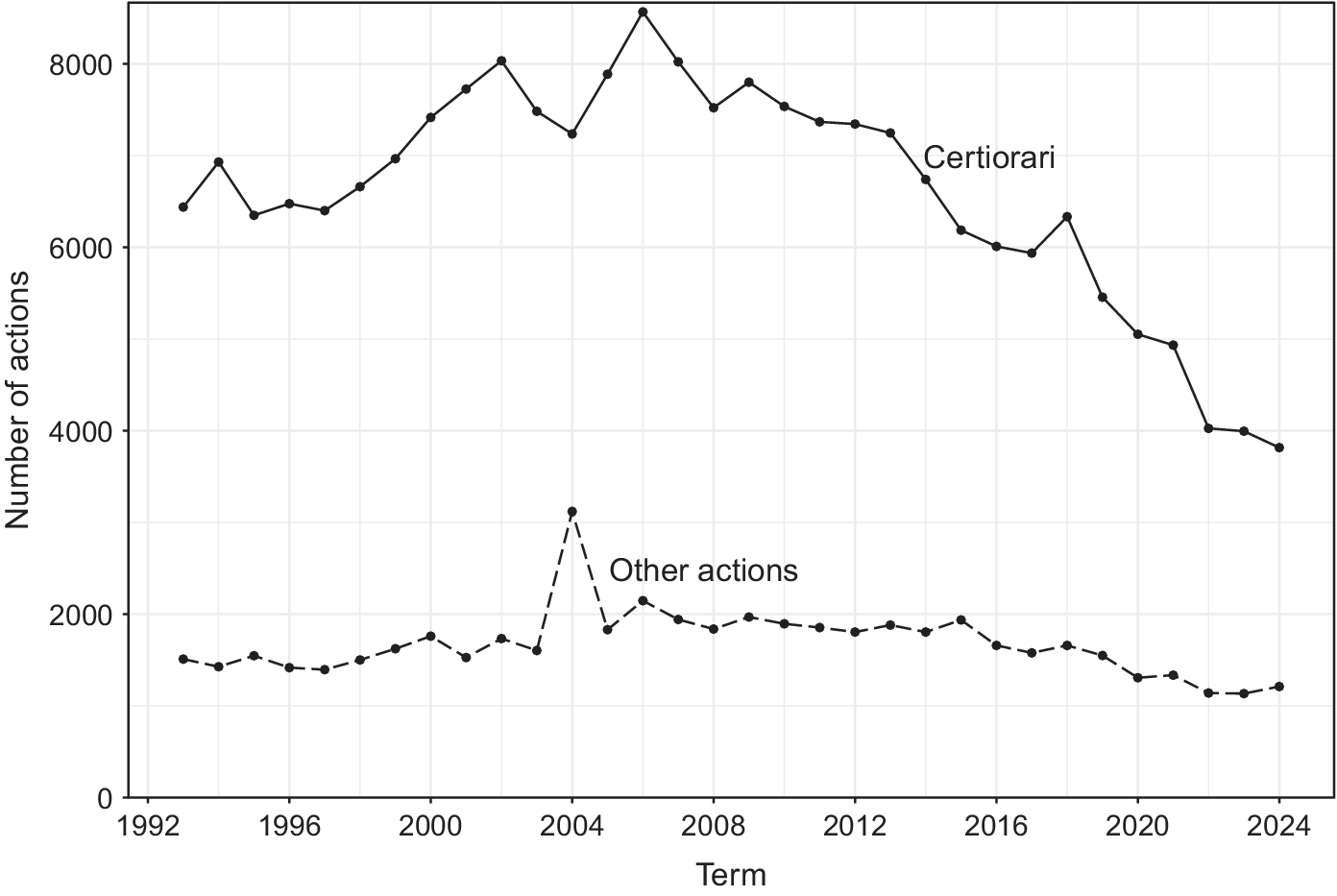

Parsing the shadow docket with respect to cert sheds further light on the composition of the Court’s overall docket and how it has changed over time. Drawing from the Shadow Docket Database, Figure 3 depicts the number of case-related actions taken by the Court per term, between 1993 and 2024—that is, all actions excluding attorney discipline-related orders and admissions to the bar. We differentiate between decisions on petitions for cert and all other actions. As noted above, the majority of the Court’s docket involves petitions for certiorari. When we subset to case-related actions, the prominence of cert petitions becomes even more apparent, as they comprise 80% of such actions. Both sets of actions have decreased since a peak in the mid-2000s—dropping from more than 10,000 actions in the 2006 term to just over 5,000 in the 2024 term.

Figure 3. Shadow Docket Actions 1993–2025, Broken Down by Cert Grants/Denials Versus Other Actions.

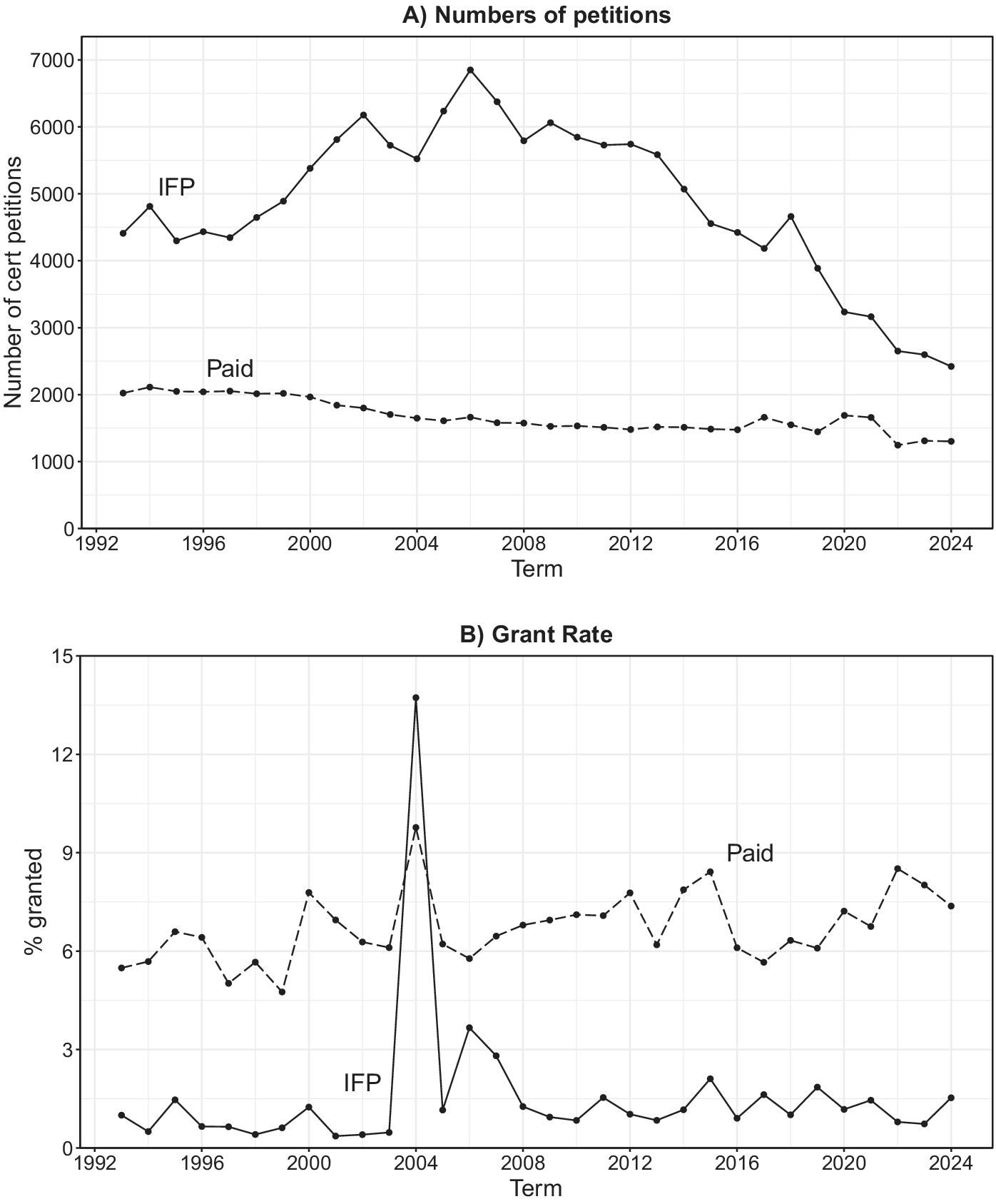

Turning specifically to the decline in cert petitions, Figure 4A depicts the number of cert petitions per term. We break down cert petitions into their two main types. “Paid” petitions are those in which the litigants bear the full cost of filing a cert petition, whereas in forma pauperis (IFP) petitions are those in which fees are waived, usually due to the indigency of criminal defendants. Because the latter are generally frivolous petitions, the Court has always been much more likely to grant cert to paid petitions. Intriguingly, Figure 4 shows that while the number of paid petitions has trended somewhat downwards since around 2000, the drop in IFP petitions since 2005 has been much starker, going from 6,850 in 2006 to about 2,400 in 2024. Thus, the decline in IFP petitions is primarily driving the overall decrease in the Court’s docket size since the turn of the century.

Figure 4. Cert Petitions 1993–2025, Broken Down by Paid Versus in forma pauperis (IFP) Petitions. A) The number of petitions over time; B) The rate at which petitions are granted, by type. (The spikes in percentage granted in the 2004 term are the result of U.S. v. Booker, 543 U.S. 220 (2005), which made the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines advisory, thereby forcing many lower courts to re-evaluate sentences in numerous cases.)

How has the steep decline in IFP petitions affected the composition of the Court’s actions? On average, only

![]() $ 1.6\% $

of IFP petitions are granted per term.Footnote 14 Despite the decrease in IFP petitions filed, the grant rate has remained relatively stable. By contrast, the smaller decline in the number of paid petitions has been accompanied by an increase in their grant rate, as seen in Figure 4B. The combination of these trends has led IFP petitions to become an even smaller share of petitions granted certiorari. Excluding petitions associated with a GVR, between the 2020 and 2024 terms, less than

$ 1.6\% $

of IFP petitions are granted per term.Footnote 14 Despite the decrease in IFP petitions filed, the grant rate has remained relatively stable. By contrast, the smaller decline in the number of paid petitions has been accompanied by an increase in their grant rate, as seen in Figure 4B. The combination of these trends has led IFP petitions to become an even smaller share of petitions granted certiorari. Excluding petitions associated with a GVR, between the 2020 and 2024 terms, less than

![]() $ 6\% $

of all petitions granted certiorari were filed IFP. Thus, paid petitions have become even more central to the Court’s merits docket.

$ 6\% $

of all petitions granted certiorari were filed IFP. Thus, paid petitions have become even more central to the Court’s merits docket.

Returning to the puzzle of the Court’s shrinking merits docket, of course, aggregate statistics like this can only tell us so much. But it does appear that variation in IFPs is what is driving the “denominator” in the Court’s cert equation. At the same time, the grant rate for IFP and Paid petitions has remained fairly constant over time, suggesting that the Court’s overall taste for hearing cases has not changed as dramatically as the raw numerator of merits cases would suggest. Further parsing the Court’s cert decisions by petition type might shed more light on these questions.

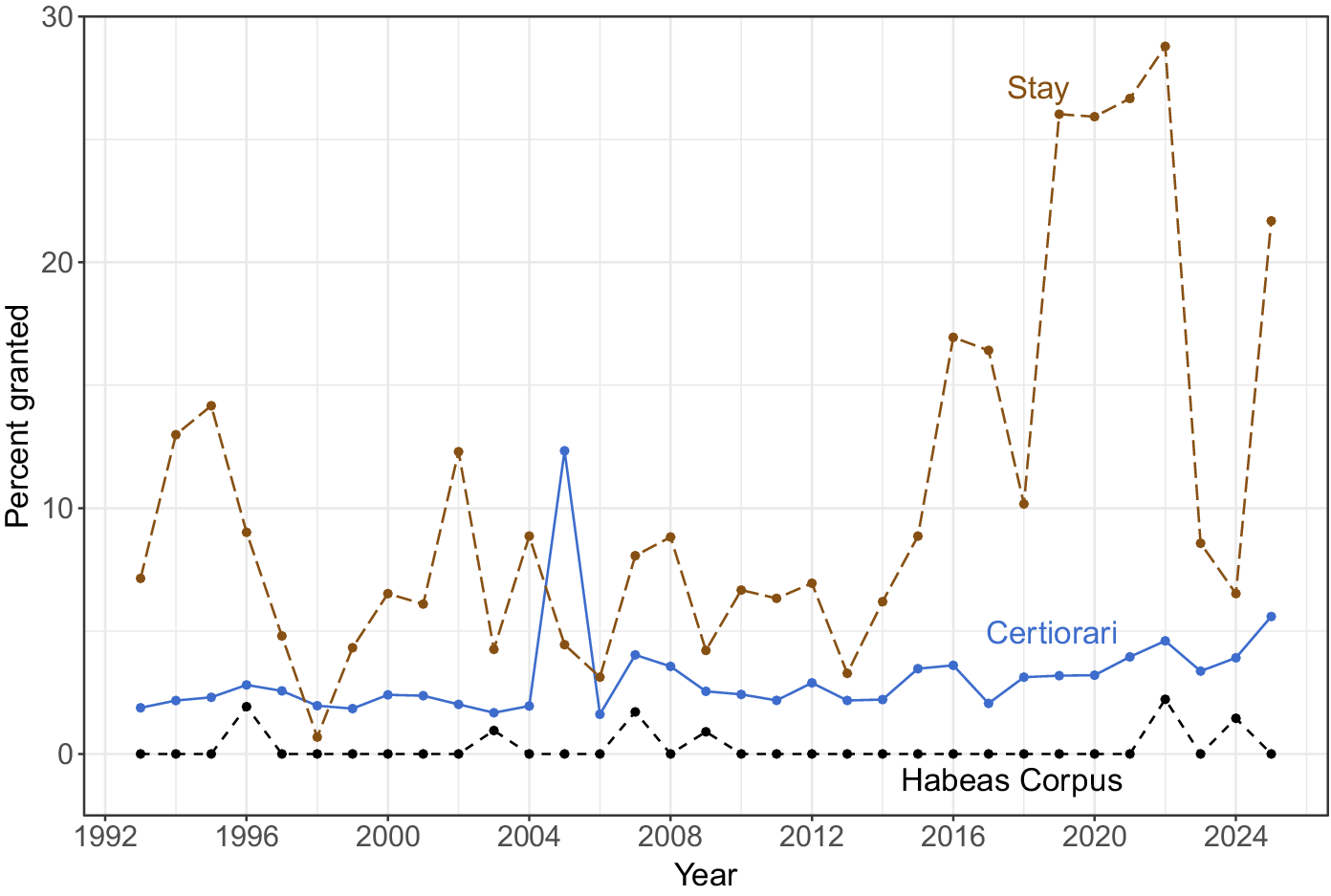

Finally, in addition to the type of action taken by the Court, the data set provides information on how grant rates vary by the type of relief requested by a litigant. Figure 5 depicts the rate at which the Court grants petitions for three of the most common action classes: certiorari, habeas corpus, and stays. Grants of writs of habeas corpus are even less common than writs of certiorari. In only six out of the past 32 years has the Court even granted a single habeas corpus petition. In contrast, the Court is much more willing to grant a stay. The percentage of granted stays varies significantly over this period—peaking during the first two years of the Biden administration before dropping precipitously during the last two.

Figure 5. Petition Grant Rate, 1993–2024.

Emergency applications

Perhaps the most pressing substantive question surrounding the Court’s use of the shadow docket is its ruling in so-called “emergency applications”—that is, requests for the justices to act in a very expedited fashion due to some time-sensitive issue. Indeed, the popular website SCOTUSblog essentially equates the shadow docket with the Court’s emergency docket:

The Supreme Court’s emergency docket, also known as the shadow docket, consists of applications seeking immediate action from the Court. Unlike the merits docket, these cases are handled on an expedited basis with limited briefing and typically no oral argument, and the Court often resolves them in unsigned orders with little or no explanation.Footnote 15

The Court’s handling of emergency applications came under scrutiny in the first year of the second Trump administration, due to the administration frequently turning to the Court for relief in the face of lower courts blocking several of its actions and policies (see, e.g., Sherman Reference Sherman2025, Vladeck Reference Vladeck2025a).

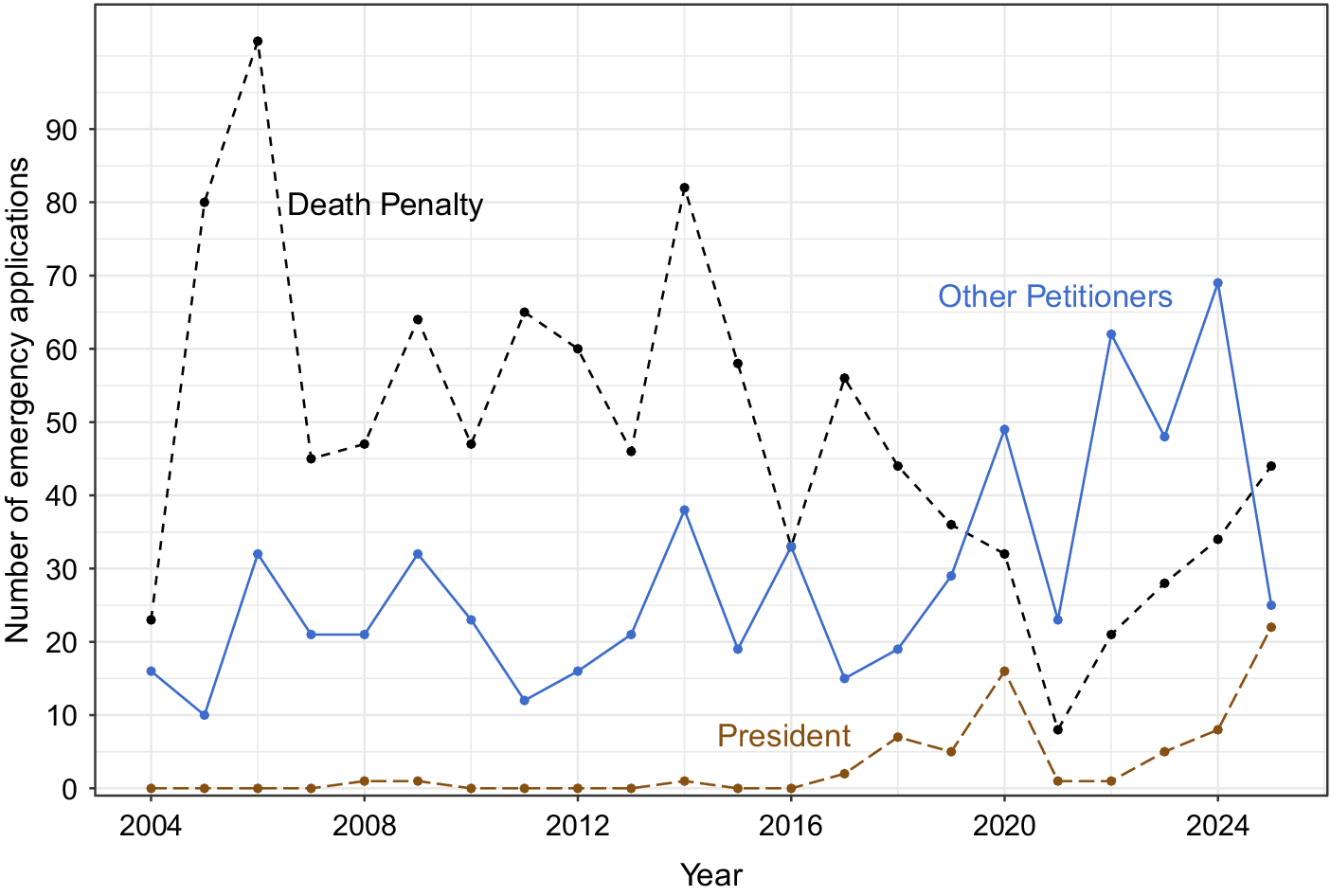

Of course, the Supreme Court makes important rulings each term on the scope of presidential authority via its merits docket; for example, in July 2024, the Court effectively gave presidents absolute immunity for official acts (Trump v. United States, 603 U.S. 593). But in terms of specific requests to either block executive actions or to reassess lower court determinations that a particular action by the government is unlawful, the shadow docket is where much of the action lies. Figure 6 depicts the trend in emergency applications between the years of 2004 and 2025; we define emergency applications as those with dockets of the form “yyAxxx” that request a stay, an injunction, or for the Court to vacate a lower court’s order—see the database’s coding protocols for further details. (We begin with 2004 because the way the Court classifies such applications was not consistent before the 2003 term; we use years here as the unit of analysis instead of term in order to make the relevant presidential administration in power clearer.) We break down the applications into three categories: death penalty-related applications, applications filed directly on behalf of the president/executive branch, and a miscellaneous category (e.g., individuals filing actions against states or civil actions). To account for actions taken at the end of a presidential administration, we adjust each year so that it starts on January 20 and ends on January 19 of the following year.

Figure 6. Emergency Applications, 2004–2025. Note that to account for actions taken at the end of a presidential administration, we adjust each year so that it starts on January 20 and ends on January 19 of the following year.

Two interesting trends emerge from the figure. First, death penalty applications have declined in the past two decades, in line with overall decline in the number of executions in the United States (Gramlich Reference Gramlich2016); however, there has been an uptick in these applications in recent years. Second, the Trump administration’s use of emergency applications in the first nine months of 2025 represents an all-time high (22 as of October 3, 2025), exceeding the former peak of 16 in 2020 during the last year of the first Trump administration.

Moving forward, researchers could conduct individual-level analyses of these applications to determine what predicts when the justices are likely to side with or against the government. For example, do the straightforward predictions of the attitudinal model—which Segal and Spaeth (Reference Segal and Spaeth2002) cabined to merit decisions—apply to emergency decisions on the shadow docket? It seems quite likely that they would, but testing this proposition would further our understanding of the extent to which ideology and/or partisanship structures voting patterns on the modern court.Footnote 16

Ideal point estimates and dissents

One of the core contributions of empirical judicial politics has been the development of ideal point estimates, which are useful both for tracing the historical trajectory of justices and the Court over time and for use in individual-level models of justices’ voting.Footnote 17 However, almost without exception, all such estimates rely solely on merits votes, ignoring the potential information from shadow docket decisions.Footnote 18 Given how few merits decisions the Court hears these days, shadow docket votes could provide valuable information for ideal point models of the justices. On this point, as Vladeck (Reference Vladeck2025b) has noted, ignoring decisions the Court makes on the shadow docket can lead to overestimates of the overall unanimity that the Court operates under; the justices, for example, have divided neatly along ideological lines in several high-profile cases in 2025 involving emergency applications from the Trump administration.

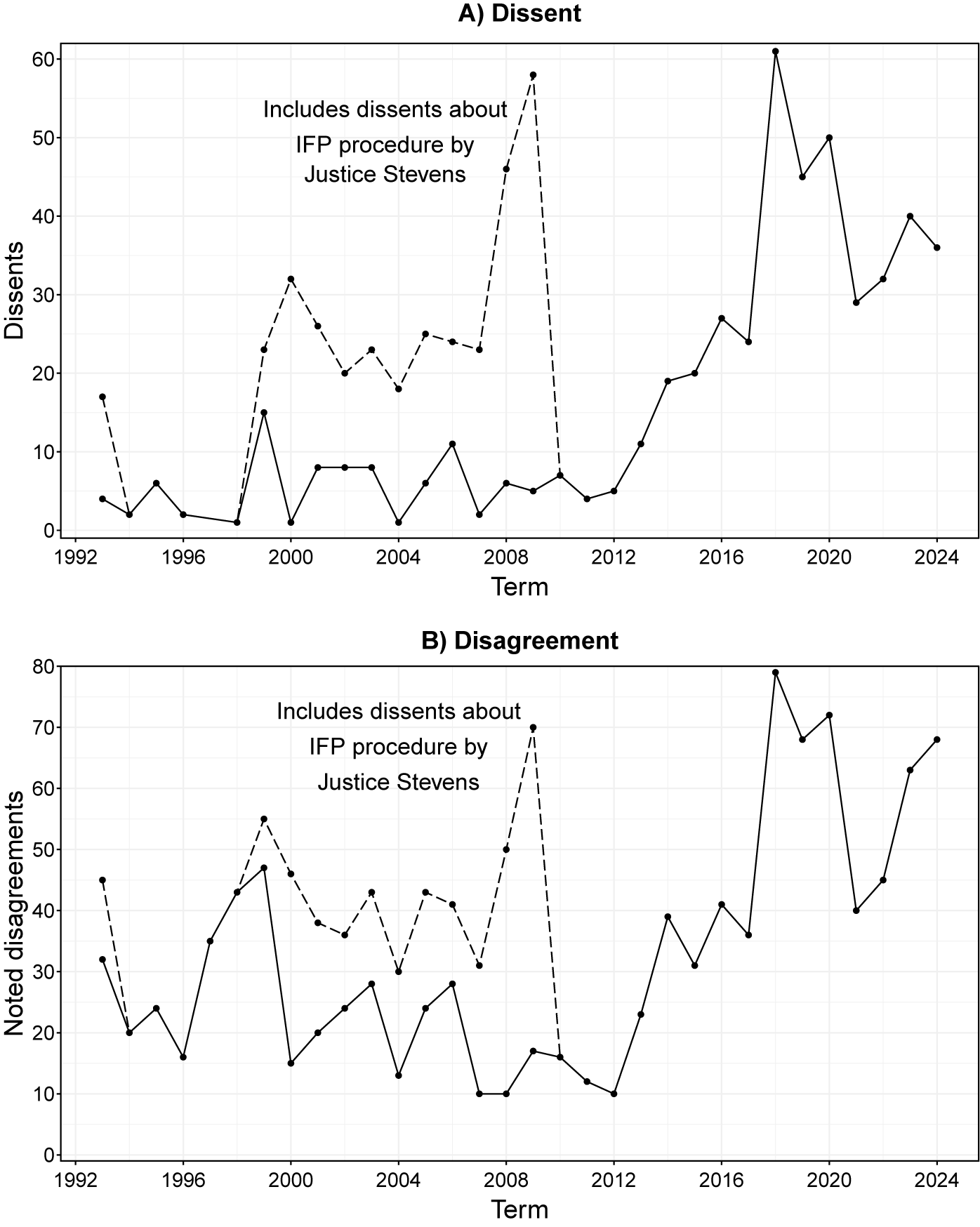

How contentious are shadow docket actions among the justices? While shadow docket orders are themselves unsigned, sometimes one or more of the justices will publicly dissent from the Court’s action. Figure 7A plots the number of docket-days accompanied by a written dissent over time. In the 1990s and 2000s, written dissent was relatively rare.Footnote 19 Starting in 2013, the number of written dissents steadily increased, before peaking with 61 written dissents in the 2018 term.

Figure 7. Disagreement and Dissent. A) The number of docket-days accompanied by a written dissent over time. B) The number of docket-days featuring disagreement or dissent over time. (The dashed line includes dissents by Justice Stevens concerning the practice of denying IFP petitions.)

A written dissent is not the only way that a justice can indicate opposition to an order. Instead, they can simply express that they would grant or would deny an order—without a written explanation. Figure 7B combines these disagreements with written dissents (so dissents are a subset of disagreements). Overall, the pattern is similar to what we observe if we focus exclusively on written dissents; however, we observe slightly higher levels of disagreement in the late 1990s.

As these statistics suggest, the Shadow Docket dataset is organized around actions, and not justice votes. But it is straightforward to code judicial votes for Shadow Docket cases featuring at least one dissent. The existence of disagreement in these non-merits decisions allows us to explore whether the justice’s behavior on the shadow docket mirrors their actions on merits cases.

Using the same method as Martin and Quinn (Reference Martin and Quinn2002), we estimate the ideal point of the Rehnquist Court from 1994 to 2004—using only non-merits decisions.Footnote 20 To be sure, this should be seen as preliminary and suggestive enterprise, for the following reason. Standard item-response models such as those employed by Martin and Quinn (Reference Martin and Quinn2002) assume “sincere voting,” which is reasonable for merits votes. Shadow Docket cases, by contrast, are much more likely to feature insincere voting by justices in the form of suppressed dissents, which makes estimating standard ideal point models more difficult.Footnote 21

With this caveat in mind, Figure 8 compares our estimates to Martin-Quinn scores derived from merits decisions. First, Figure 8A depicts the estimated Martin-Quinn score between 1994 and 2004 (higher scores mean more conservative voting) for each justice, using their initials; not surprisingly, Clarence Thomas is estimated to be most conservative justice in this period and John Paul Stevens the most liberal. Figure 8B does the same using shadow docket votes with dissents; interestingly, William Rehnquist and Anthony Scalia are estimated as more conservative in these votes than Thomas. Figure 8C depicts the correlation between the two measures, using justice-year as the unit of analysis; we can see the measures move together quite closely, with a correlation of .89. Finally, Figure 8D compares the rank orderings of three justices over time (Scalia, O’Connor, and Ginsburg), which are also quite closely correlated. All told then, voting patterns on the shadow docket yield similar estimates of conservatism to justices’ votes on the merits docket.

Figure 8. Comparison between Martin-Quinn Estimates and Ideal Points Estimated Using Shadow Docket Votes, Based on the Natural Court That Served between the 1994 and 2004 Terms. A) MQ estimates. B) Shadow docket estimates. C) The correlation between the two estimates. D) Comparison of the rank order of ideology for justices over time.

The shadow docket and the judicial hierarchy

There exists a rich theoretical and empirical literature on the role of the Supreme Court in the federal judicial hierarchy.Footnote 22 This includes a large literature on explaining cert votes, which implicitly implicates the shadow docket (under our broader definition of the term). Yet because the shadow docket is now used quite frequently by the justices to either affirm or reverse important lower court decisions, there is still much to learn about the interplay of the shadow docket and the Court’s overseeing of the judicial hierarchy. In this subsection we suggest two ways in which the Shadow Docket Database could be used to further our understanding of the hierarchy.

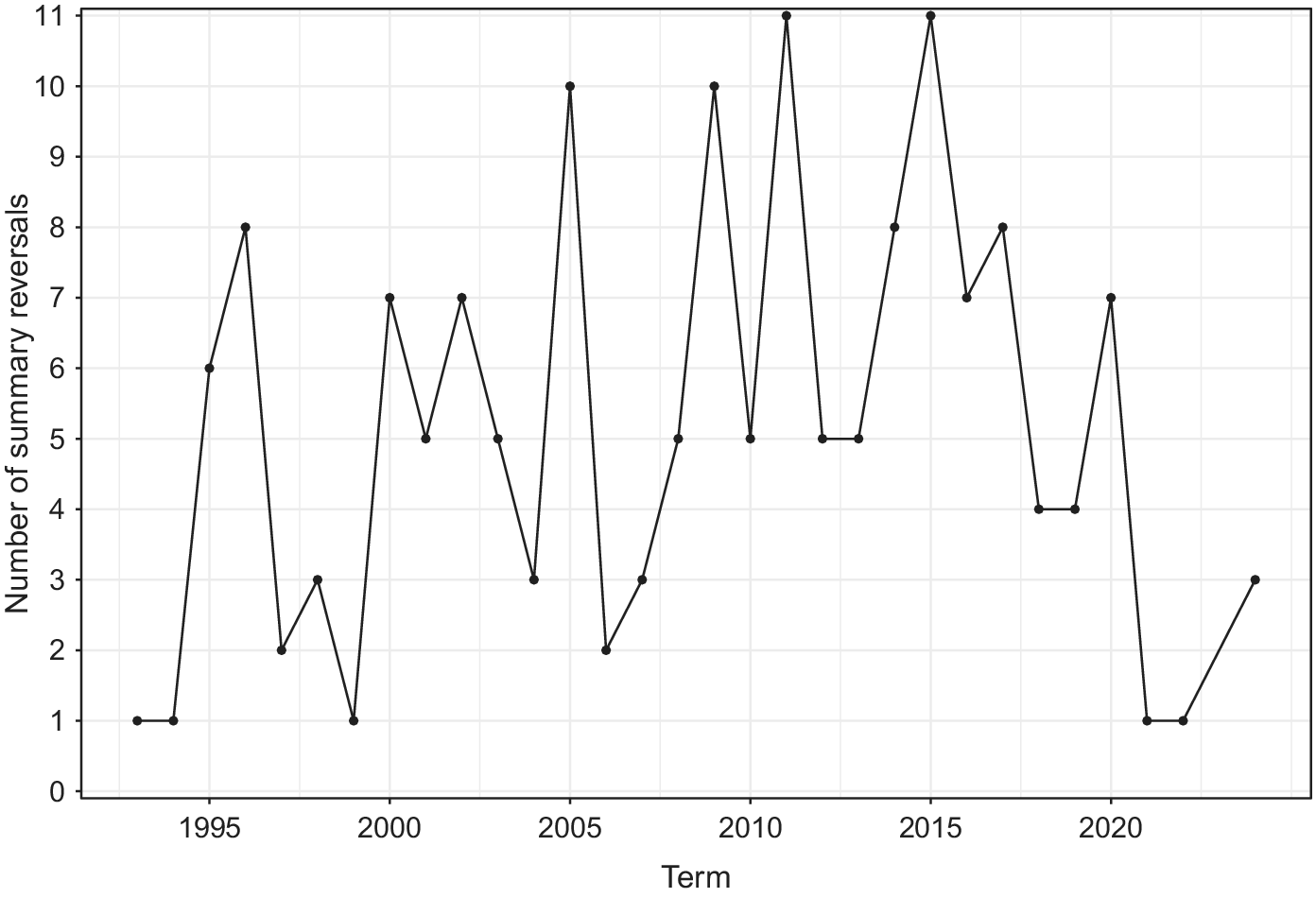

First, consider the Court’s use of summary reversals, in which the Court reverses a lower court’s decision immediately after granting cert, without requesting full briefs from the parties or holding oral arguments. This component of the shadow docket has received a significant amount of qualitative attention from legal scholars. Opinions in summary reversal decisions are much shorter than merits opinions, and are usually issued as a “per curiam” opinion (meaning it is issued in the name of the Court overall), rather than as a signed opinion by an individual justice. Because of this, the Court’s use of summary reversals has been criticized by many legal academics. Summary reversals, for example, were one of the main focuses of Baude’s (Reference Baude2015) original shadow docket article; there he argued that the selection of cases for summary reversal “remains a mystery, [which] makes it difficult to tell whether the Court’s selections are fair” (p. 2). Similarly, Vladeck (Reference Vladeck2023, 89) argues that summary reversals “short-circuit the Court’s normal process; parties have no advance notice that a specific case is under consideration for summary treatment, and so briefs that were focused on why the Court should (or should not) grant certiorari become the basis for the justices’ rulings on the merits.”Footnote 23

Figure 9 depicts the number of summary reversals per term from 1993 to 2024. As it turns out, the Court has not summarily reversed many decisions over this time period—though it has always issued at least one per term.Footnote 24 Interestingly, the Court’s use of summary reversals in this period peaked in 2015 (along with 2010), the year in which Baude coined the shadow docket. Summary reversals have declined significantly since then, a puzzle explored in some detail by Golde (Reference Golde2025). Beyond these aggregate statistics, a more fine-grained analysis of the conditions under which the Court uses summary reversal would increase our understanding of how the Court wields this tool to attempt to increase its control over the lower courts.Footnote 25

Figure 9. Summary Reversals, 1993–2024.

Additionally, with respect to appeals, the Shadow Docket database includes docket numbers identifying both the lower court from which a case emerged and the specific lower court dispute. For appeals from federal courts, these lower court docket numbers allow our data to be merged with the Federal Judicial Center’s Integrated Database, which can allow scholars to ask questions such as the types of issues being appealed and the volume of appeals coming from the federal government. Similarly, merits decisions captured by the Supreme Court Database can be merged with our dataset through docket numbers.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s shadow docket now comprises some of the Court’s most important work, yet systematic data on the shadow docket has remained scant. In this paper we have summarized the United States Shadow Docket Database. We hope the creation of the database will allow researchers to more systematically study this crucial part of the Supreme Court’s work.