Introduction

The political year can be titled ‘From Alpha to Omicron’. The variants of the Covid-19 virus and the waves of infection dominated Irish politics for a second year in a row. The government had to walk a tightrope of demands for reopening, and for caution against further outbreaks. Though it probably managed to maintain a reasonable balance among those competing demands, the government lost popularity, especially as other issues, such as that of housing, re-emerged as battlefields on which the government was again forced to fight. Despite, or perhaps because of, that, the coalition government held together well. Though there were some disputes between the parties of government, its first full calendar year together was characterized more by unity than division.

Election report

There were no elections in Ireland in 2021.

Cabinet report

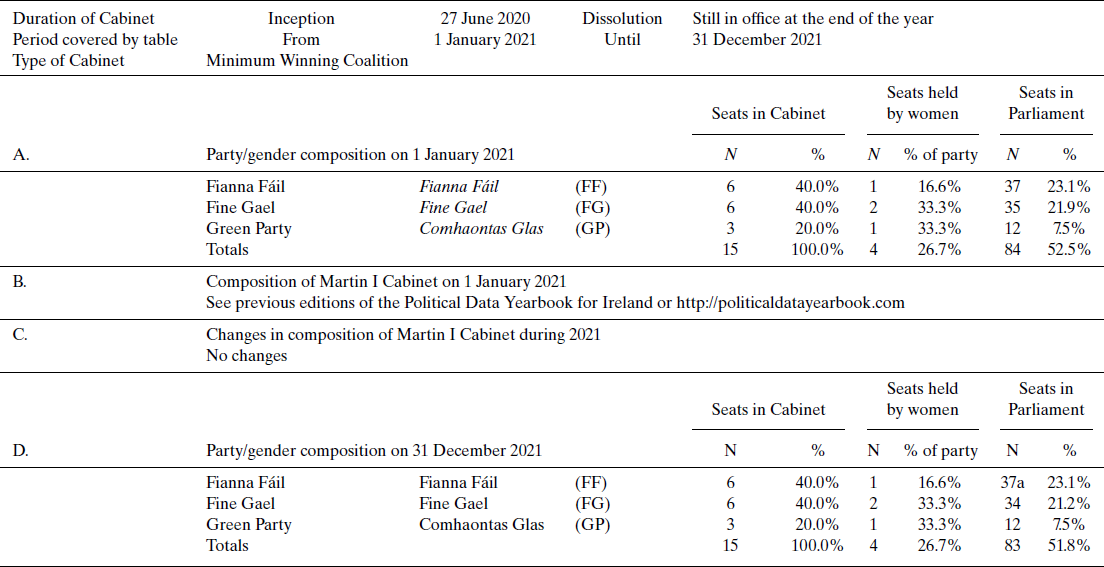

There were no Cabinet changes in 2021 (Table 1).

Table 1. Cabinet composition of Martin I in Ireland in 2021

MacSharry, in report. One Fianna Fáil member of Parliament lost the whip for voting against the government. However, he did not leave the party and is counted as a member of the party also on 31 December 2021.

Sources: Department of the Taoiseach and Oireachtas Éireann websites.

Parliament report

The government's popularity was tested in July in a by-election to replace a resigning Fine Gael (FG) TD (MP) and former minister. Ivana Bacik, a well-known Labour Party activist and senator won that seat for her party, though Fine Gael performed reasonably well. Fianna Fáil's (FF) vote collapsed, however. This reduced the government's slim majority.

The so-called Zappone affair (see Issues in national politics) caused one Fianna Fáil TD, Marc MacSharry, to resign his party's whip to allow him to vote against a confidence motion in the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Simon Coveney. MacSharry was a long-time critic of the party leader and Taoiseach Micheál Martin, but he remained in the party organization and voted with the government in other votes.

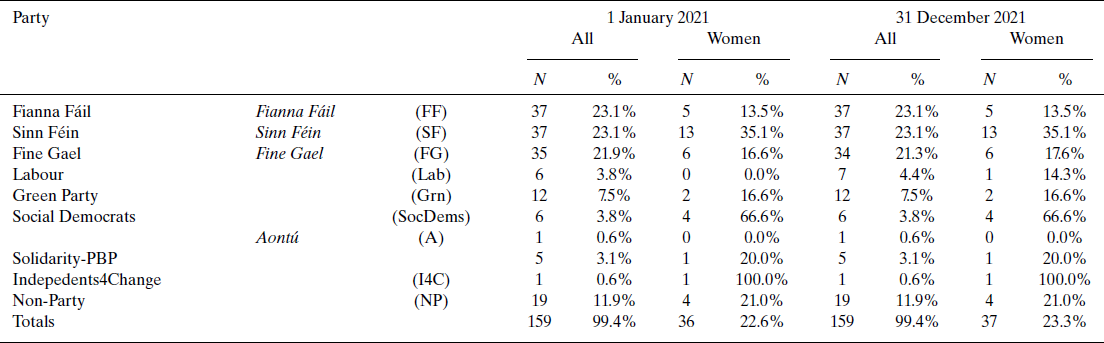

Parliament composition data can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. Party and gender composition of the lower house of the Parliament (Dáil Éireann) in Ireland in 2021

Note: There are 160 TDs (members of Parliament), including the Ceanna Comhairle (speaker) who was elected as a Fianna Fáil TD, but does not sit with the party or attend its meetings. He does, however, remain a member of that party. Except where there is a tie, he does not vote in divisions of the House.

Source: Oireachtas Éireann website, accessed on 5 June 2022.

Institutional change report

There were no institutional changes in 2021.

Issues in national politics

One of the early successes of the new government in September 2020 was that it reopened schools in a manner that was relatively normal given the Covid-19 pandemic. The decision taken late that year to celebrate a ‘meaningful Christmas’ backfired as a surge in cases, in part caused by the new Alpha variant, meant that hospitals quickly filled in January and deaths followed. Chastened, and under pressure from teachers’ unions, the government took the decision not to reopen schools in January.

The disease spread widely through society and maintained pressure on hospital capacity, making the reopening of the economy unlikely despite the significant pressure on the state finances. Because the government had said it would prioritize school reopening, it became beholden to unions that were refusing to countenance in-person education while the disease was still spreading. The government felt it could not open non-essential retail, hospitality or industry, such as construction, until schools were reopened. It took until mid-April for the schools to reopen, and only then other sectors were allowed to reopen, but slowly. It was late summer before indoor dining was permitted.

Any sense of normality was gone as the population grew used to the Taoiseach addressing the nation to announce more or continued closures. The government also found itself obliged to follow the lead of the Chief Medical Officer, Dr Tony Holohan. It had defied him in autumn 2020, but public opinion supported his positions when cases rose. He was always more cautious than politicians wanted, but the structure of the decision-making on the response to the virus meant that he had specific advantages in setting the agenda.

In the first full year of his premiership Micheál Martin addressed the nation directly more times than a Taoiseach might expect to do in 10 years. Despite the pressure of the pandemic the new coalition settled in well, with few political crises or disputes on public view from within the government. This was despite a significant drop in the poll ratings of Fine Gael, which had benefited from a rally-around-the-flag effect when the virus first came to prominence.

A no-confidence motion in Simon Coveney, Minister for Foreign Affairs, was put down late in the year because of his offering a minor role to a former Cabinet colleague, Katherine Zappone. A slew of text messages gave the impression of a cosy elite comfortable with itself, and Coveney's handling of the so-called Zappone affair was cack-handed. It probably ruled him out of the running for future leadership of Fine Gael. As mentioned above (see Parliament report), this prompted Fianna Fáil TD Marc MacSharry to resign his party's whip to allow him to vote against Coveney.

Housing, which had been the major issue of the election in 2020, returned to prominence in 2021 as house prices increased dramatically. The government's solutions, which were often to provide extra funding for home buyers, did not inspire confidence, and housing returned to being the most important issue for potential voters (Leahy Reference Leahy2021). On this Sinn Féin was seen as a more competent.

The other major issue was health. There had been a cross-party agreement to introduce a universal healthcare system called Sláintecare. Despite the consensus to introduce it, there was some resistance among healthcare workers, especially hospital consultants, about how it would be operationalized. The resignation of two officials charged with its implementation, followed by resignations of members of an advisory board, suggested that there was some reluctance within government to see Sláintecare implemented. The government responded by putting more senior officials in charge of Sláintecare, with the purpose of taking closer control of its implementation.

Despite the enormous costs of the pandemic, the Irish economy remained on its healthy trajectory, with the tax returns showing continued growth. Much of this is based on strong foreign direct investment, attracted by, among other things, the low corporate tax rate. Ireland came under pressure to sign an international tax agreement to levy corporate tax rates of at least 15%. Ireland resisted this but in October signed the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's (OECD) International Tax Agreement, which guaranteed that Ireland would levy 15% for multinationals with revenues in excess of €750 million, with no change to the 12.5% rate for businesses with revenues below €750 million. This was a success for the government, although it received very little coverage in Irish media.

What received relatively more coverage was the challenge to the Northern Ireland protocol among unionists. The protocol was an agreement between the UK and the European Union to ensure that there was no hard border on the island of Ireland. This necessitated some regulatory controls between Britain and Northern Ireland, which initially cause some delays. Unionist protests against the protocol were probably more to do with the symbolism of those controls rather than their actual impact, but it seemed that Brexit was still not resolved by the end of 2021 despite the UK having formally left the EU at the start of the year.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by IReL.