Hernandez et al. (Reference Hernandez, Melson-Silimon and Zickar2025) extensively evaluate the definition of the term worker—and by extension, work—and argue to include nonhuman animals as workers. We believe this inclusive approach has merit; however, it raises important conceptual questions regarding whether the field of I-O psychology currently possesses a coherent conceptual definition of a worker to support Hernandez et al.’s theoretical foundation. To fully realize the potential of this inclusive perspective, substantial conceptual work remains. Their arguments prompted the authors of this commentary to reflect on how the term worker should be defined and explore using the Podsakoff et al. (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2016) conceptual construction process to achieve a robust, precise, and theoretically coherent conceptualization.

Questions and considerations in defining work and the worker

Hernandez et al. begin by arguing that animal labor fits within the definition of “work.” They contend that the designation of “worker” should not depend on whether a being is engaged in a “moral and acceptable effort exchange within society” but rather on whether that being’s life experiences can be meaningfully analyzed through the lens of I-O psychology (p. 5). This assertion invites several philosophical questions about the scope of I-O psychology and the boundaries of its domain. For instance, should “work” encompass ethically contested forms of labor such as sex work, surrogacy, sweatshop labor, human trafficking, or slavery?Footnote 1 Hernandez et al. believe so, because these domains are I-O relevant, they have aspects that fulfill some I-O relevant dimension of expertise. Recognizing these activities as “work” also enables I-Os to apply their expertise to advocate for improved labor conditions. However, if the definition of work is expanded, several related questions emerge. Does “work” imply some level of agency or volition, or can it exist under coercion or compulsion?Footnote 2 Should I-O psychologists advocate for revisions to the APA Ethical Guidelines to address non consensual or illegal labor, or work that violates human or animal rights?Footnote 3 Should I-Os engage with these issues independently, or is some of this research redundant with frameworks from other disciplines that are better equipped to address them?Footnote 4

Ultimately, these questions converge on two closely related issues: what is the true domain of “work,” and which attributes fall just beyond its boundaries (Figure 1)? Hernandez et al. indicate that many instances of formal employment (e.g. barista, project manager) are “POSH (professional, office-based, safe from harm, in high income countries) work” that generally maximize all four dimensions of work outlined in Ruiz-Quintanilla and England (Reference Ruiz-Quintanilla and England1996). These forms of employment are fully subsumed in the broad domain of work (Figure 1) and therefore have near universal agreement both within and outside the field of I-O. Hernandez et al. also shows that the domain of what is considered work can get very big.

Figure 1. The domain of work.

However, because of societal shifts and technological innovations, we are constantly pushing the boundaries of what we may or may not consider work. Hernandez et al. showed that activities such as caregiving and leisure time pursuits can be considered forms of work. With the proliferation of informal labor like gig economy tasks and volunteering, scholars may fundamentally disagree on which jobs operate neatly within the domain of work and which jobs operate on the fringes of what we consider “work.” More complex still are cases of non traditional labor, such as non consensual or exploitative work and animal labor. Although we do not deny the importance of studying these forms of labor, we argue that there are critical nuances within these concepts that challenge our existing conceptual boundaries around work that should be robustly explored. Therefore, we call on I-O psychologists to actively engage in these discussions, critically examine both personal and professional definitions of work, and share in the effort to ensure the fairness and inclusivity of our field.

Answering these questions using a systematic four-stage concept definition development framework

Addressing these complex conceptual questions requires a structured and rigorous definitional evaluation process. Clear conceptual boundaries enable researchers to design better measurement items, improve experimental rigor, and implement more robust validation strategies—ultimately resulting in more reliable findings and stronger practical implications. Therefore, the authors issue a call to action for the field of I-O psychology to develop a robust and precise definition of the field’s foundational concept: worker.

To facilitate this process, this commentary will apply the concept development framework outlined by Podsakoff et al. (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2016) (see the first column of Table 1) to the concept of worker. Specifically, it will examine how various sections of the focal article contribute to developing a robust conceptual definition and provide recommendations for completing each stage.

Table 1. Concept Development Framework Applied to “Worker”

Note. “Not explicitly addressed” means that the information was not readily found within the text of the article but may have been executed by the authors.

Framework for the creation of a concept definition

The framework by Podsakoff et al. (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2016) is a four-stage process that creates a robust concept definition. Highly cited (853 citations as of June 2025) from the journal Organizational Research Methods, this framework has been used in various domains where creating rigorous concept definitions are important such as scale-development papers, theory primers and PhD research-methods textbooks. This commentary will walk through each stage and summarize the most important insights in each stage that will help answer important conceptual questions. A comprehensive summary with recommendations in each stage can be found in Table 1.

Evaluating stage 1: Identify potential attributes of the concept and/or collect a representative set of definitions

Stage 1 involves systematically completing eight complementary activities, each using a diverse group of I-Os and non-I-O experts to ensure the definition isn’t limited to one disciplinary lens. First, search dictionaries and use language models (e.g. ChatGPT, Gemini) for lay definitions (Step 1.1). Next, survey the literature (Step 1.2). Hernandez et al.’s deep historical scan can be paired with contemporary readings from labor economics or sociology to expose conceptual gaps. Then, interview experts and run focus groups (Steps 1.3–1.4), including diverse professionals, to explore varied definitions of “worker.” Steps 1.5 and 1.6 offer qualitative insights via structured observation and case studies. To sharpen conceptual boundaries, consider comparisons with an opposite pole (Step 1.7). Defining a clear contrast class—say, leisure or companion animals—forces precision about where the concept starts and ends, and helps stakeholders articulate exclusion criteria. Finally, current operationalizations are examined (Step 1.8). Hernandez et al. used Ruiz-Quintanilla and England (Reference Ruiz-Quintanilla and England1996) 14-item survey’s definition of work, which clusters into four dimensions of work. This can be complimented by mapping widely used I-O instruments such as the Job Diagnostic Survey or the Work Design Questionnaire onto those same dimensions. Doing so shows continuity with established measures while highlighting the need for any new items.

Evaluating stage 2: Organize the potential attributes by theme and identify any necessary and sufficient ones

Stage 2 narrows the broad information from Stage 1 into a clear, actionable definition of “worker.” First, condense attributes into a focused set (Step 2.1); Hernandez et al. illustrate this with four dimensions: burden/control, contextual constraint, responsibility & exchange, and social contribution, organizing attributes into central and peripheral categories. Next, identify necessary and sufficient attributes—or at least shared attribute sets (Step 2.2). Hernandez et al. state that any single dimension is enough to establish I-O relevance. To clarify the internal logic of the concept, researchers should decide if the concept follows a family resemblance, hybrid, or "m-of-n" structure. Finally, researchers should provide an explicit organizing framework and inclusion criteria (Step 2.3). Hernandez et al.’s four-dimension model could function as both a conceptual framework and a practical inclusion rule.

Evaluating stage 3: Develop a preliminary definition of the concept

Based on insights gathered from earlier stages, researchers should develop a more fully articulated, preliminary definition of the concept, including a thoughtful examination of its boundary conditions. This requires clearly specifying both the purpose of the concept and the types of entities to which it applies. Hernandez et al. purposefully cast a wide net; they define a worker as any being whose activities are I-O relevant, with the argument that this is inclusive of nonhuman animals.

Furthermore, Hernandez et al. ground their conceptualization of I-O relevance in the four-dimensional definition of work proposed by Ruiz-Quintanilla and England (Reference Ruiz-Quintanilla and England1996). However, they also note that they do not regard this framework as the sole definition of work (p. 6). If other definitions of work are possible, then there may be additional dimensions that are worker relevant that would be necessary for comprehensively defining workers. Once this definition of work is finalized, it will be critical to consider the construct within a broader nomological network, including aspects of dimensionality, stability, relatability to relevant constructs, and potential antecedents and consequences.

Evaluating stage 4: Refining the conceptual definition of the concept

In the final stage of conceptual definition development, iterative refinement is essential. Researchers must ensure that the definition is clear, free of jargon, and both parsimonious and comprehensive. Equally important is soliciting feedback from peers. When defining a concept as foundational to I-O psychology as what constitutes “work” and who qualifies as a “worker,” it is especially critical to seek input from both within and outside the field to ensure the definition is theoretically sound, practically relevant, and broadly interpretable.

Conceptual definition development: Exemplar

We believe the results of this extensive conceptual development will help create a comprehensive, inclusive, and robust definition of a worker. Systematic implementation of Podsakoff et al. (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2016) ’s framework to develop a concept definition would require time, an extensive survey of the literature, numerous iterations of feedback, and buy-in from other I-Os. To guide the beginning stages of this process, we provide examples of how issues not explicitly discussed in the focal article could be solved with hypothetical outputs from both Stage 1 (Identify Potential Attributes of the Concept and/or Collect a Representative Set of Definitions) and Stage 2 (Organize the Potential Attributes by Theme and Identify Any Necessary and Sufficient Ones) of the framework.

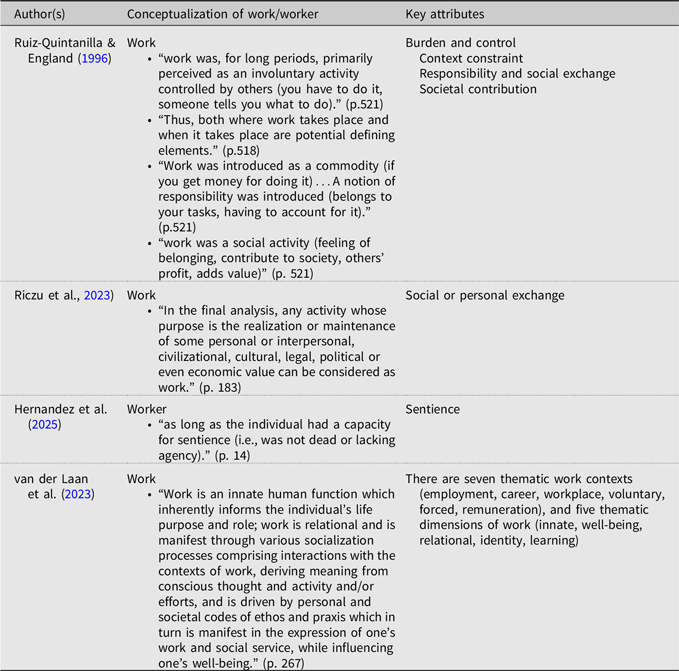

What are all the possible key attributes of a worker? Let’s survey the literature

To organize the literature on what constitutes a worker, we can look to Maynes and Podsakoff’s (2014) rigorous concept definition process. Maynes and Podsakoff (Reference Maynes and Podsakoff2014) had similar goals to Hernandez et al. as they sought to expand the conceptualization of their respective construct (voice behavior). To accomplish this, they summarized existing definitions, key attributes, and limitations of prior conceptualizations of voice behavior. Doing this serves multiple purposes: It aids in the literature review process (Step 1.2), it examines the benefits and limitations of current operationalizations (Step 1.8), and it identifies core attributes of the focal construct (Steps 2.1–2.3). Table 2 modeled after Maynes and Podsakoff (Reference Maynes and Podsakoff2014)’s research can serve as the template for what the conceptual development of the worker definition should look like. This table is not exhaustive of all the attributes and is meant as a starting point.

Table 2. Worker Attributes Summary Template

How do we organize all these key attributes? Proposing a family resemblance concept structure

After all other components of Stage 1 are completed, researchers will be left with an extensive list of attributes and definitions of the focal concept. Many researchers choose to organize these attributes using a “necessary and sufficient” structure, in which objects must contain certain elements to be considered “worker”; objects that lack these elements are decisively not categorized as “worker.”

However, due to the vast range that exists within the domain of work, we recommend the use of a “family resemblance” structure instead, in which each object might have at least one element in common with another object, but it is rare if there are elements that are shared by all objects. We believe this structure also aligns well with Hernandez et al. (Reference Hernandez, Melson-Silimon and Zickar2025) use of the four-dimensional Ruiz-Quintanilla and England (Reference Ruiz-Quintanilla and England1996) framework.

An organized table like Table 3 helps illustrate key aspects of Hernandez et al.’s conceptualization. It shows that certain category members—such as Traditional POSH—that share many attributes with others exhibit a stronger family resemblance to the category and are thus more prototypical. At the same time, it acknowledges that various worker groups may not exhibit all the attributes but still possess enough to be classified as “workers.” The table also clarifies who does not qualify as a worker, emphasizing that having only some or a single attribute is insufficient to meet the conceptual criteria thresholds established by subject matter experts. Such an extensively refined table below will help eliminate confusion and make the definition of worker more exact. This approach may also result in the discovery that animal workers resemble more prototypical examples of workers than other human-centric cases of workers (volunteers, gig workers, caregivers, etc.). In addition, this table can be iteratively refined by future researchers as the field evolves, especially if there is a desire to make the definition more precise. This could involve adopting a hybrid structure that combines necessary and sufficient conditions with a family resemblance model—requiring researchers to specify both the essential attribute(s) and a set of shared attributes, of which at least m out of n must be present to define the concept. For example, a rough preliminary definition template could require that (a) the necessary condition is sentience (Hernandez et al. and (b) at least three out of five key attributes are present.

Table 3. Proposed Family Resemblance Concept Structure

Conclusion

Hernandez et al. highlight essential considerations for a more inclusive perspective to who is considered a worker within I-O psychology. Building on those insights, this commentary offers a structured framework and sample process templates to help future researchers systematically define what work is and who qualifies as a worker. We propose that a family resemblance structure offers a valuable conceptual approach to these questions. This comprehensive process supports the development of a generalizable, widely accepted definition of work. Practically, the framework enables researchers, practitioners, and policymakers to evaluate unique cases using a transparent, replicable structure. Conceptually, it reconciles competing definitions in the literature by:

-

1. compiling a comprehensive list of worker attributes,

-

2. reducing ambiguity through a family resemblance model with quantifiable thresholds, and

-

3. providing a flexible structure for future revisions—accommodating new or necessary attributes as the nature of work evolves.

This clarity will advance the discipline in a direction aligned with its core values and mission.