Introduction

When a country experiences multiple mass mobilisations in close succession, what accounts for variation in the geospatial scope of protest? When a new protest wave sees mobilisation occur in different localities than the preceding one, what factors are at play? Proponents of political opportunity structure theory might argue that the expansion or contraction of political opportunities underpin changes in the extent to which protest occurs throughout a country (Tarrow Reference Tarrow2011; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1986). Other research might suggest that the availability of resources at different moments in time helps to explain changes in the geospatial scope of protests (Edwards and McCarthy Reference Edwards, McCarthy, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2007; McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977). Another area of scholarship would highlight the role of grievances and frames in mobilising populations across a greater or lesser geographic area (Benford and Snow Reference Benford, Snow, Morris and Mueller1992, Reference Benford and Snow2000). Other scholars centre the role of mobilising structures in facilitating these various collective action processes (Gerhards and Rucht Reference Gerhards and Rucht1992; Boekkooi and Klandermans Reference Boekkooi and Klandermans2022; McAdam Reference McAdam, Klandermans, Kriesi and Tarrow1988), suggesting that activist social networks will be crucial in shaping the geospatial scope of mobilisation (Gould Reference Gould1991, Reference Gould1993). This article examines the case of mass protests in Ukraine 1990-2004, exploring how the emergence and development of activist networks may align with changes in the geospatial dispersion of protest over time. The aim of this article is not to prove the dominance of one theory over another, but rather to improve our understanding of how activist social networks can shape changes in protest dispersion over time.

There have been three key moments of mass mobilisation between the beginning of Ukraine’s departure from the Soviet Union, and the advent of the Euromaidan protests in 2013: the 1990 ‘Revolution on Granite’, the 2000-2001 ‘Ukraine Without Kuchma’ protests, and the 2004 ‘Orange Revolution’. Examining the geospatial shifts in protest over these three mass mobilisations allows us to unpick some of the ways in which activist networks facilitate the expansion of protest across space, contributing to the sociological literature. This article also enhances scholarship on these Ukrainian protests specifically. Whilst scholars such as Onuch (Reference Onuch2014a, Reference Onuch2017, Reference Onuch, Kowal, Hrytsenko, Mink, Reichardt, Umland, Balcer, Codogni, Dymyd, Gretskiy and Hnatiuk2019), Beissinger (Reference Beissinger2007, Reference Beissinger2011, Reference Beissinger2013), Kuzio (Reference Kuzio2007, Reference Kuzio2005), Nikolayenko (Reference Nikolayenko2021, Reference Nikolayenko2017), Wilson (Reference Wilson2005) and Zelinska (Reference Zelinska2020), amongst others, have done much to further our understanding of these mass mobilisations, there is still no detailed, systematic, city-level analysis of events across Ukraine during these protestsFootnote 1.

This article seeks to build on this research by investigating where protest took place beyond Kyiv from 1990-2004, and exploring the role played by activist networks during these mobilisations. It draws on archives and interviews with activists made available by The Three Revolutions (3R) Project (Kisly Reference Kisly2016; The 3R Project 2020), and newspaper reports from Ukrainska Pravda, Korrespondent.net and Radio Svoboda, utilising protest event analysis, along with QGIS software to visually represent findings. This article does not aspire to conduct comprehensive protest event analysis for the three mass mobilisations, but rather seeks to enhance our understanding of the regional dimensions of these protests, and the role played by activist networks. Thus, this article serves three aims: first, to identify regional, city-level patterns of protest during moments of mass mobilisation in Ukraine; second, to examine how activist networks may contribute to geospatial shifts in protest across space over time; and third, to provide valuable context for studies of more recent mass mobilisations in Ukraine, including the 2013-14 Euromaidan and resistance to Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion, ongoing at the time of writing. It presents novel empirical findings on the geospatial scope of events across the country from 1990 onwards, and demonstrates some of the ways in which regional activist networks expanded, developed, and sought cross-cleavage collaboration, aiming to facilitate increasing nationwide mobilisation.

However, it is important to acknowledge two ways in which these findings are limited. First, my findings on the geospatial scope of the protest waves may be constrained by my data sources. The arrival of the internet and development of the Ukrainian media landscape mean that protest events were better reported over time. Hence, my claims about the geospatial extent of these protests should be interpreted with caution, and ideally expanded upon in the future. Second, this article does not make definitive causal claims about the relationship between activist networks and geographically diffuse protest. Many other factors may also have influenced protest over time, such as increased internet and mobile phone usage, and demographic changes. Nevertheless, this article contributes to the literature on mass mobilisation by highlighting the role of activist networks over time, and enhancing our knowledge on the history of protest in Ukraine.

In the sections that follow, I first outline the case of Ukraine and the three mass mobilisations to be compared, and then develop a theoretical framework for my study, drawing on the contentious politics literature. I briefly outline my methodological approach, and then present my findings.

The case of Ukraine: a protesting nation

Ukraine provides a country context in which there have been multiple waves of mass mobilisation over a 30-year period. Scholars such as Onuch (Reference Onuch, Stoltzfus and Osmar2021) and those participating in the Three Revolutions Project (The 3R Project 2020; Kowal et al. Reference Kowal, Hrytsenko, Mink, Reichardt, Umland, Balcer, Codogni, Dymyd, Gretskiy and Hnatiuk2019; Kowal Reference Kowal2019) have highlighted key moments of mass mobilisation that represented nationwide protest engagement by ordinary citizens. These include the 1990 Revolution on Granite, the 2000-2001 Ukraine Without Kuchma protests, and the 2004 Orange Revolution. All of these moments of mass mobilisation predominately featured mass protests in the capital. However, large regional centres were also reported to have experienced mass protest events. In fact, as I will show in what follows, the geospatial scope of protest was much larger than generally reported. I will also demonstrate that the geospatial distribution of protest varied between the mass mobilisations, providing adequate leverage to examine what shapes spatial variation in protest over time. Whilst some localities protested repeatedly, others only mobilised in later protest waves. Below I will outline each of the mobilisations in turn. Let us begin by looking to the Revolution on Granite of 1990.

The Revolution on Granite (late September - 17 October 1990)

The first of these mass protests, the Revolution on Granite (RoG) of September to October 1990, was one of a wave of pro-independence protest movements from 1989-1991 in the wider Soviet Union (Onuch Reference Onuch2017). Amongst Soviet republics, Ukrainian dissidents had experienced the harshest repression and many were only released from Gulags, prisons, and psychiatric hospitals from 1987 onwards (Onuch Reference Onuch, Kowal, Hrytsenko, Mink, Reichardt, Umland, Balcer, Codogni, Dymyd, Gretskiy and Hnatiuk2019; Bilocerkowycz Reference Bilocerkowycz1988). Following these releases, old dissident organisations resumed their activities and new ones formed, agitating on issues ranging from human rights and economic reform to Ukrainian independence (Marples Reference Marples2019). Dozens of these dissident and informal organisations worked together to challenge the Communist party in Spring 1990, presenting as the ‘Democratic Bloc’ and winning 108 out of 450 seats in parliament (Marples Reference Marples2019). In July 1990, the newly-elected parliament declared Ukrainian sovereignty, giving the Ukrainian Soviet Republic’s laws precedence over USSR laws, and Ukraine control over its army, national bank, and currency (Verhovna Rada 1990; The Ukrainian Weekly 1990). This set the stage for the RoG: in the months that followed, dissidents, activists and students began to call for the declaration of sovereignty to be enshrined in law, alongside steps to secure Ukraine’s full independence – including an end to military service outside Ukraine, the de-politicisation of the police, armed, and security forces, and particularly the non-signing of a new Union Treaty with the USSRFootnote 2 (Onuch Reference Onuch2017; Mykhelson Reference Mykhelson2011).

Protests against a new Union Treaty began to build through September 1990, largely co-ordinated or inspired by the work of Rukh (Kisly Reference Kisly2016). Originally founded in 1989 as Narodnyi Rukh Ukraini za Perebudovu (the People’s Movement of Ukraine for Reconstruction), the civic and political organisation aimed to secure an independent and democratic Ukraine (Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group 2006). It later registered as a political party in 1993. The September events culminated in a massive march in Kyiv on 30 September 1990, followed by the beginning of student hunger strikes on 2 October on Kyiv’s central square, now known as Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Onuch Reference Onuch2017). These protests became known as the Revolution on Granite, named after the granite of the square. For 16 days, hunger strikes continued in Kyiv alongside protests of solidarity in other parts of Ukraine (Kisly Reference Kisly2016). On 17 October the government agreed to the students’ key demands, bringing the RoG to an end (Onuch Reference Onuch2017). The protests played an important role in helping Ukraine move along the path to full independence, declared in 1991.

The next wave of protests to occur in Ukraine were the miners’ strikes of the early nineties, a continuation of strikes which began in the late eighties (Marples Reference Marples1991). Whilst some of the largest strikes occurred during the Soviet period, the nineties’ strikes peaked in 1993 as over 1 million workers, primarily miners from the Donbas region, went on strike over wide-ranging grievances, including hyperinflation, unpaid wages, and unmet expectations about Ukrainian independence (Makarenko Reference Makarenko2016; Crowley Reference Crowley2010). The miners sought cooperation with Rukh, and the protests were significant in size, successfully securing early elections (Crowley Reference Crowley2010; Ahapov Reference Ahapov2011). There was also a nationwide component as miners from eastern and western Ukrainian coal basins sought to coordinate their protests (Kravchenko Reference Kravchenko2015). However, the miners’ protests differed from other large mobilisations before and after as they mostly comprised of a specific group of actors (industrial workers), relied on strikes, and were primarily concentrated in eastern Ukraine. As such, although they are an important episode in Ukraine’s protest history, they will not be studied in this article.

Ukraine Without Kuchma (15 December 2000 – late March 2001)

The subsequent wave of mass mobilisation, the 2000-2001 ‘Ukraine Without Kuchma’ (Ukrayina bez Kuchmy or UBK) protests, were more all-national in character. President Kuchma had just won a second term in the 1999 Presidential elections (Central Election Committee 2000), but his return to office did not enjoy an auspicious start. Leaks implicating Kuchma in the persecution of his opposition – including the murder of journalist Georgiy Gongadze – election falsification, and high-level corruption led to protests calling for his resignation (Wilson Reference Wilson2005; Melkozerova Reference Melkozerova2019; Kuzio Reference Kuzio2007). Tents were set up in Kyiv on 15 December 2000, marking the beginning of a wave of ‘Ukraine Without Kuchma’ protests across the country which lasted until the following spring (Mykhelson Reference Mykhelson2011). Actors from across the political spectrum mobilised, united by a desire to unseat Kuchma (Onuch Reference Onuch, Marples and Mills2015, Reference Onuch, Stoltzfus and Osmar2021). The protests did not succeed in removing Kuchma, but they laid important groundwork for mass protests several years later, in response to the election of his successor.

The Orange Revolution (22 November 2004 – 27 December 2004)

Dissatisfaction with Kuchma’s regime only grew following UBK, accompanied by the sense that politicians were growing wealthy at ordinary Ukrainians’ expense (Onuch Reference Onuch2014a). Kuchma’s chosen successor, his Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych, was also implicated in corruption, and tied to the Donetsk oligarchic group (Kuzio Reference Kuzio2005). When, in the run up to the elections, it became clear that Yanukovych was unlikely to defeat his main rival – the charismatic and pro-European Yushchenko – the Kuchma regime committed election fraud on a massive scale (Kuzio Reference Kuzio2005; Way Reference Way2005). Activists and the opposition had anticipated that Kuchma would use fraud to secure his successor’s victory, and they began planning, training, and preparing for protests months in advance (Onuch Reference Onuch2014a). When the election results declared a victory for Yanukovych on 22 November 2004, these opposition networks mobilised up to 2 million citizens in support of Yushchenko, in what became known as the Orange Revolution (Onuch Reference Onuch2014a; White and McAllister Reference White and McAllister2009). Protesters decried the fraudulent victory of Yanukovych, and successfully demanded fresh, fair elections, securing the challenger Yushchenko’s victory in new elections on 27 December 2004 (Wilson Reference Wilson2005).

Regional dimension of the protest waves

Many accounts of all three of these mass mobilisations focus on events in Ukraine’s capital. Studies of the Revolution on Granite are few, and focus mainly on the hunger strikes in Kyiv (Onuch Reference Onuch2017, Reference Onuch, Kowal, Hrytsenko, Mink, Reichardt, Umland, Balcer, Codogni, Dymyd, Gretskiy and Hnatiuk2019). Nikolayenko (Reference Nikolayenko2021) offers a fascinating study of nationwide support for the hunger strikes, but still focuses on events in the capital. Research on Ukraine Without Kuchma also concentrates on Kyiv, where the largest protest events and the greatest repression took place (Kuzio Reference Kuzio2007; Mykhelson Reference Mykhelson2011). Similarly, many popular accounts of the Orange Revolution such as Wilson (Reference Wilson2005) focus on the capital, and as a result, the casual observer could be forgiven for thinking that mobilisation only took place in Kyiv. Nevertheless, various sources have hinted at the regional dimensions of all these protests: telegrams from across Ukraine sent to participants of the RoG (used by Nikolayenko in her 2021 study) demonstrate nationwide support (MAPA 2022); media reports of UBK suggest that when protests halted in Kyiv, mobilisation continued elsewhere (Ukrainska Pravda 2001i, 2001j, 2001k); and we know that half of the Orange Revolution protesters originated from east, central and southern Ukraine (ESS 2004; Beissinger Reference Beissinger2011). This article seeks to conduct preliminary mapping of cities where protests took place across Ukraine during these three mass mobilisations, and explore what may explain any changes in their geographic scope. Below I turn to the contentious politics literature to examine precisely what factors may account for shifts in the geography of protests over time.

Theoretical Framework: From opportunities, resources, and frames, to networks

What might account for geospatial shifts in mobilisation over subsequent protest waves in a country? This question addresses not processes of protest diffusion precisely, but rather the continuities across and differences between waves of protests in the same country.

Political opportunities

Scholars of political opportunity structures would argue that differences in the available political opportunities of the three mobilisations may account for differences in the geospatial scope of protest. Favourable political opportunities – such as the emergence of elite divisions and allies, and the opening up of a political regime – are thought to facilitate mobilisation by reducing the costs and increasing the possible benefits associated with collective action (Tarrow Reference Tarrow2011; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1986). For example, falsified elections such as those which triggered the Orange Revolution have been identified as an important catalyst of mass protest, capable of empowering individuals to overcome the collective action problem (Tucker Reference Tucker2007). Therefore, we might expect mobilisation to be more widespread in the Orange Revolution than other protest waves.

Frames and grievances

Nevertheless, other scholars would argue that the grievances and frames of a protest are key in facilitating the expansion of dissent across space (Benford and Snow Reference Benford, Snow, Morris and Mueller1992). In order to mobilise, people in a locality need to feel discontented about something – a grievance – and also feel that by engaging in collective action they can improve the situation (McAdam, McCarthy, and Zald Reference McAdam, McCarthy and Zald1996). Frames are used to help create consensus around these grievances, and guide action (Benford and Snow Reference Benford and Snow2000). These grievances and frames are an important factor in supporting widespread mobilisation, as, particularly when they have cross-cleavage appeal, they can motivate citizens to mobilise across a country. Thus, if the grievances and frames of the different Ukrainian mass mobilisations vary in the extent of their nationwide appeal, this may help explain shifts in the extent of nationwide mobilisation over time.

Resources

Other researchers would acknowledge that grievances, frames, and political opportunities are important in motivating individuals to mobilise across multiple localities, but highlight that mobilisation in itself is not possible without available resources. In order to stage a nationwide mobilisation, various forms of resources are needed: moral, cultural, social-organisational, human, and material (Edwards and McCarthy Reference Edwards, McCarthy, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2007). Without some configuration of these resources – including but not limited to legitimacy, organisational experience, equipment and funds, and labour – no matter how motivating a grievance, or how favourable the political opportunities, nationwide protest is impossible.

Networks

Whilst these resources, political opportunities, and grievances and frames are undoubtedly vital elements which contribute to shifts in the geospatial scope of mobilisation over time, I propose that the development and activity of activist networks across a country are above all crucial. Mobilising structures such as SMOs (social movement organisations) and activist networks are central to all these collective action processes outlined above (Gerhards and Rucht Reference Gerhards and Rucht1992; Boekkooi and Klandermans Reference Boekkooi and Klandermans2022; McAdam Reference McAdam, Klandermans, Kriesi and Tarrow1988).

SMOs and activist networks are required to mobilise resources (Edwards and McCarthy Reference Edwards, McCarthy, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2007; McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977), with broader networks providing access to resources, including information, from across a wider population (Granovetter Reference Granovetter1983). Activist networks also do the important work of identifying and seizing upon favourable political opportunities, disseminating information about them, and organising campaigns around them, such as the Ukrainian activists who prepared in advance of the 2004 elections (McAdam, McCarthy, and Zald Reference McAdam, McCarthy and Zald1996, 7). Similarly, mass mobilisations do not simply emerge when groups share claims or grievances – rather activists and SMOs must work to mobilise potential constituents by framing grievances so that they will have wide appeal, and disseminating them across a population (Benford and Snow Reference Benford, Snow, Morris and Mueller1992, Reference Benford and Snow2000; Gerhards and Rucht Reference Gerhards and Rucht1992). And so, activist networks and SMOs are a fundamental part of key processes which can influence the spatial scope of protest.

Moreover, activist networks also play an important role in shaping the spatial extent of protest themselves, as a meso-level structure with the potential to coordinate organisation and local micro mobilisation (protester recruitment) across a country (Gerhards and Rucht Reference Gerhards and Rucht1992; Boekkooi and Klandermans Reference Boekkooi and Klandermans2022). Groups of activists and social movement organisations are located in different towns and cities, and connections between them form networks which span across countries (Newman Reference Newman2006; Porter, Onnela, and Mucha Reference Porter, Onnela and Mucha2009; Diani and McAdam Reference Diani and McAdam2003). Via these networks, protest participants can be mobilised simultaneously across different localities.

These activist networks are not static structures, but rather can expand and contract over time (Diani and McAdam Reference Diani and McAdam2003; van Duijn, van Busschbach, and Snijders Reference van Duijn, van Busschbach and Snijders1999). At the micro level, individual activists will come and go as their lives, availability and priorities alter (Beyerlein and Bergstrand Reference Beyerlein and Bergstrand2022). This can change the shape of networks, as arrivals may offer bridges to new groups and locations, and departures can cause a network to lose a connection to another group, and so shrink (Granovetter Reference Granovetter1983). However, even as individuals come and go over time, SMOs and networks can endure (Gerhards and Rucht Reference Gerhards and Rucht1992), as long as member turnover is not so rapid that the network is unable to retain the skills, knowledge, resources and connections necessary for mobilisation. Moreover, by reaching out to local SMOs and activist groups in new locations, activist networks can expand, share resources and framing, and encourage local activists to mobilise protesters. In particular, efforts to connect to diverse groups/SMOs can increase the potential of a network to facilitate widespread protest mobilisation, as the constituent groups have the potential to appeal to a wider segment of the population (Gerhards and Rucht Reference Gerhards and Rucht1992). Moments of mass mobilisation in turn can also play an important role in bolstering networks, bringing in new members and developing existing skills and access to resources.

All the above therefore leads me to anticipate that, in the case of Ukraine, as the engagement and activity of activist networks changes over time, this may shape shifts in the geospatial extent of mobilisation across subsequent protest waves. As activist networks in Ukraine develop over the years, via repeated mobilisation and cooperation across different groups, this may make subsequent mobilisation more successful (Gerhards and Rucht Reference Gerhards and Rucht1992), and thus more widespread. Deliberate attempts by activist networks to expand, reaching out to new groups and SMOs, may also facilitate more widespread protest. However, diverse, cross-cleavage cooperation may also bring challenges in coordination and decision-making that could hinder successful mobilisation (Boekkooi and Klandermans Reference Boekkooi and Klandermans2022; Clemens and Minkoff Reference Clemens and Minkoff2004).

Methodology

In order to test the above expectations, I employ a within-case, qualitative comparison of three mass mobilisations in Ukraine: the 1990 Revolution on Granite, the 2000-2001 Ukraine Without Kuchma protests, and the 2004 Orange Revolution. I use protest event analysis (PEA) to identify where and when protest events took place throughout Ukraine during each of these mobilisations, and I present my results in map form, using QGIS software.

PEA is an established method for generating data on discrete protest events using selected sources, traditionally news articles (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Lorenzini, Wüest and Hausermann2020; Hutter Reference Hutter and Porta2014). However, it has its shortcomings, with one of the primary criticisms being that the quality of the data is highly dependent on source selection and quality, and vulnerable to inconsistencies and biases in media reporting (Weidmann Reference Weidmann2016; Earl et al. Reference Earl, Martin, McCarthy and Soule2004). This difficulty is compounded when conducting protest event analysis for mobilisation at the regional level, as such events tend to be under-reported (Hutter Reference Hutter and Porta2014). For the purposes of this study, I worked with carefully selected Ukrainian and Russian language sources, which represent the best available data on these three protest waves for systematic data collection. I take a pragmatic approach, working with multiple sources, as advised by scholars such as Beissinger (Reference Beissinger2002) and Hutter (Reference Hutter and Porta2014). I discuss these sources, my approach, and the limitations of my PEA data below.

The RoG took place in 1990 in Soviet Ukraine, and was not accurately covered by Soviet news outlets at the time due to censorship. Therefore, I eschew media reports and primarily rely on newswires from the civic organisation Rukh, supplemented by KGB reports and interviews from the 3R Project archives (Kisly Reference Kisly2016; The 3R Project 2020). Such activist and police sources can be a valuable data source for protests which are affected by reporting biases in traditional media (Hutter Reference Hutter and Porta2014; Foltin Reference Foltin2004). I analysed all Rukh newswires and KGB reports for the period of the protest that have been made available by the 3R online archives. Archival interviews with key activists collected by the 3R project provided additional, valuable information about protest organisers and key participants.

For Ukraine Without Kuchma and the Orange Revolution, I was able to rely on more conventional, journalistic sources due to the development of the Ukrainian media landscape. News reports from Ukrainska Pravda are the primary source for these protest events. This online newspaper, one of the most trusted news sources in Ukraine, was founded in April 2000 by dissident journalist, Georgiy Gongadze, with an explicit focus on Ukrainian politics (Baysha and Hallahan Reference Baysha and Hallahan2004). Revelations about President Kuchma’s involvement in Gongadze’s murder were one of the triggers for the UBK protests, and so the outlet had a keen interest in closely covering UBK and the subsequent Orange Revolution, which sought to prevent the election of Kuchma’s hand-picked successor. I manually parsed through all Ukrainska Pravda articles published online for the time period of the protests, and coded all which referenced protest events. During the Orange Revolution, two additional online outlets, Korrespondent.net Footnote 3 and Radio Svoboda Footnote 4 also published extremely useful news roundups of protests taking place across Ukraine, and so I coded these. As US-owned outlets seeking to promote freedom of the press and democracy in Ukraine, these websites, like Ukrainska Pravda, had a keen interest in covering the protests. Their collated reports proved invaluable as journalists struggled to keep up with the sheer number of protests taking place across Ukraine at the peak of the Orange Revolution.

In order to generate protest event data from my selected sources, I carefully read them through and imputed any data about a discrete protest event as an observation in my database. The minimum data required to record a protest event was location (town, city or village), date, and type of event (e.g. demonstration, march, picket, strike). These variables are the most crucial as my theoretical focus is protest location. However, where any additional data was available, this was also coded, including protest address, time, size, identity of organisers or participants (whether groups or individuals), protest repertoires, law enforcement presence or intervention (including arrest or injury of protesters), and specific grievances, claims, symbols or slogans. Essentially, I recorded as much information as possible for each protest event observation, in case it would prove useful for the mapping of activist networks. However, the challenges of PEA and nature of my sources mean that these additional variables involve a lot of missing data. Given that this study is most interested in protest location, I do not attempt to visualise protest size or other variables in my results below, although in the discussion I will mention available protest size and other variables where relevant.

Ideally, protest event data should be triangulated via evidence from multiple sources (Della Porta et al. Reference Porta, Donatella, Hutter and Lavizzari2024). However, due to the scarcity of media reporting on regional protests during these mass mobilisations, if I required multiple reports to verify each protest event, much of my protest data would be lost, making this study unviable. In the case of these Ukrainian protests, underreporting is a much more pressing concern than overreporting or misreporting. As such, I retain protest event data in my dataset even when it is not triangulated by multiple sources.

Due to the small number of sources and limited data available, there will be protest events missing from my dataset. Still, this article represents, to the best of my knowledge, the most systematic analysis of nationwide protest during these three mass mobilisations. Nevertheless, I must highlight that my findings on the geospatial scope of the protests are constrained by my data sources. Coverage of the protests is likely to have improved over time, with reporting on the RoG in particular restricted by Soviet media censorship and the absence of the internet. I have attempted to overcome these limitations by relying on activist news wires, activist interviews, and KGB reportsFootnote 5, for my RoG data. However, my findings on regional protests should be interpreted with caution, as earlier events in particular may be under-represented. Future analysis of additional data sources can build upon the contribution made by this study.

In addition to collecting data on where and when protest takes place, I also identify activist networks involved in the mobilisations. To do this, I construct a timeline of events based on my PEA data, and systematically note all actors (individuals or groups) who are listed in my sources as participating in or organising protests in different localities. I also pay particular attention to any reported incidents of separate groups collaborating to jointly organise protest events. I then utilise qualitative analysis, drawing on process tracing techniques (Beach Reference Beach2019), to examine in greater detail the changes and continuities in the activist networks involved in mobilisation across the three protests.

It is important to note that, due to the nature of these research methods and sources, this article does not attempt to capture the ways in which factors other than activist networks may have influenced changes in the geospatial dispersion of protest between the three protest waves. And, whilst I identify possible mechanisms of effect, the findings presented below demonstrate a correlation between the development of activist networks and changes in the geospatial scope of protests, not evidence of a definitive causal relationship in this case. Other factors changing over time may have also influenced these shifts – for example, the arrival of mobile phones and the internet, which can be powerful tools for protesters (Bennett and Segerberg Reference Bennett and Segerberg2013; Neumayer and Stald Reference Neumayer and Stald2014), or demographic changes, such as a growing middle class and declining industrial sector (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006). This article focuses specifically on activist networks, and as such does not aim to assess the influence of these other factors. My findings are presented below.

Results

The changing scope of mobilisation

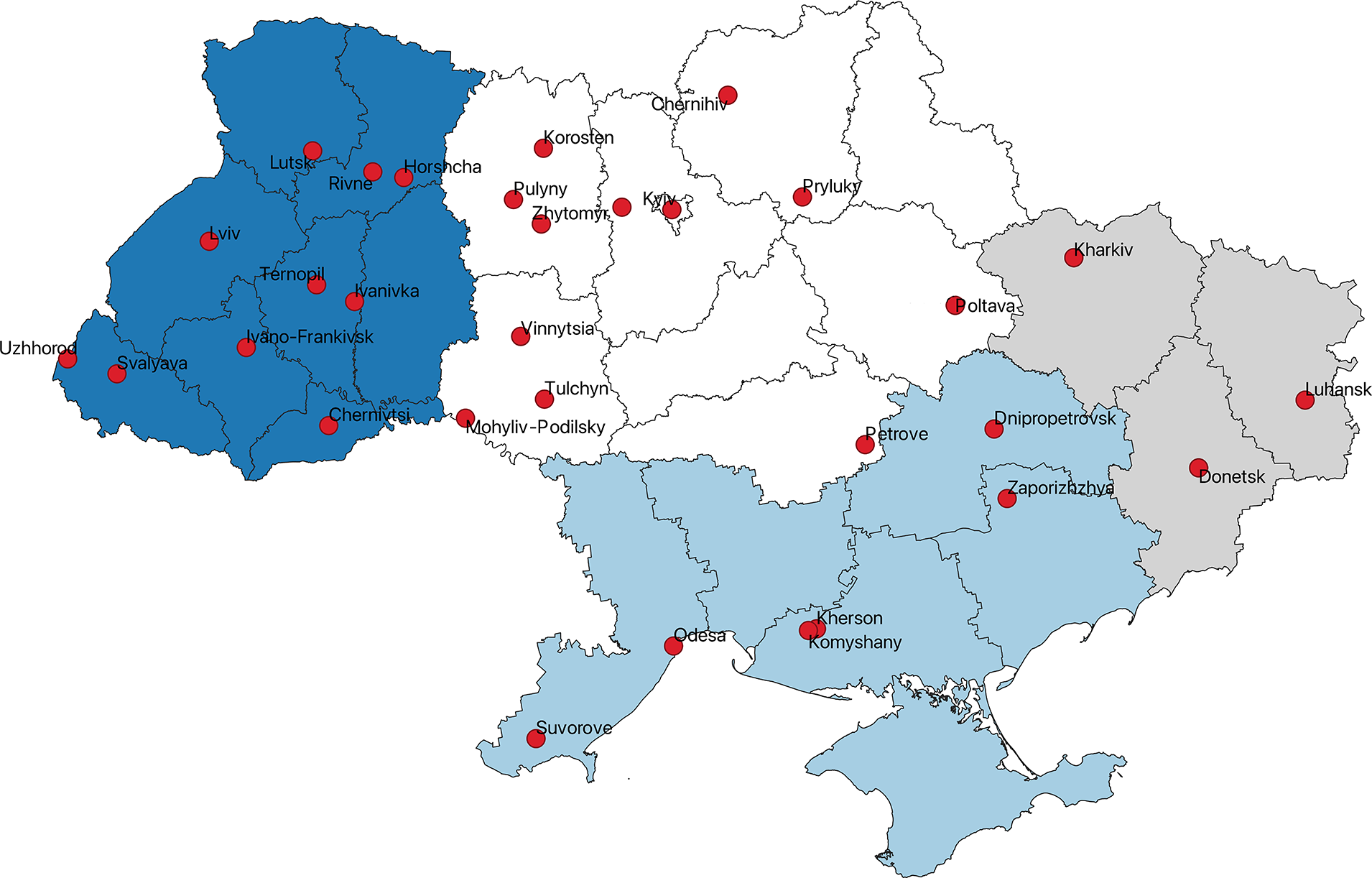

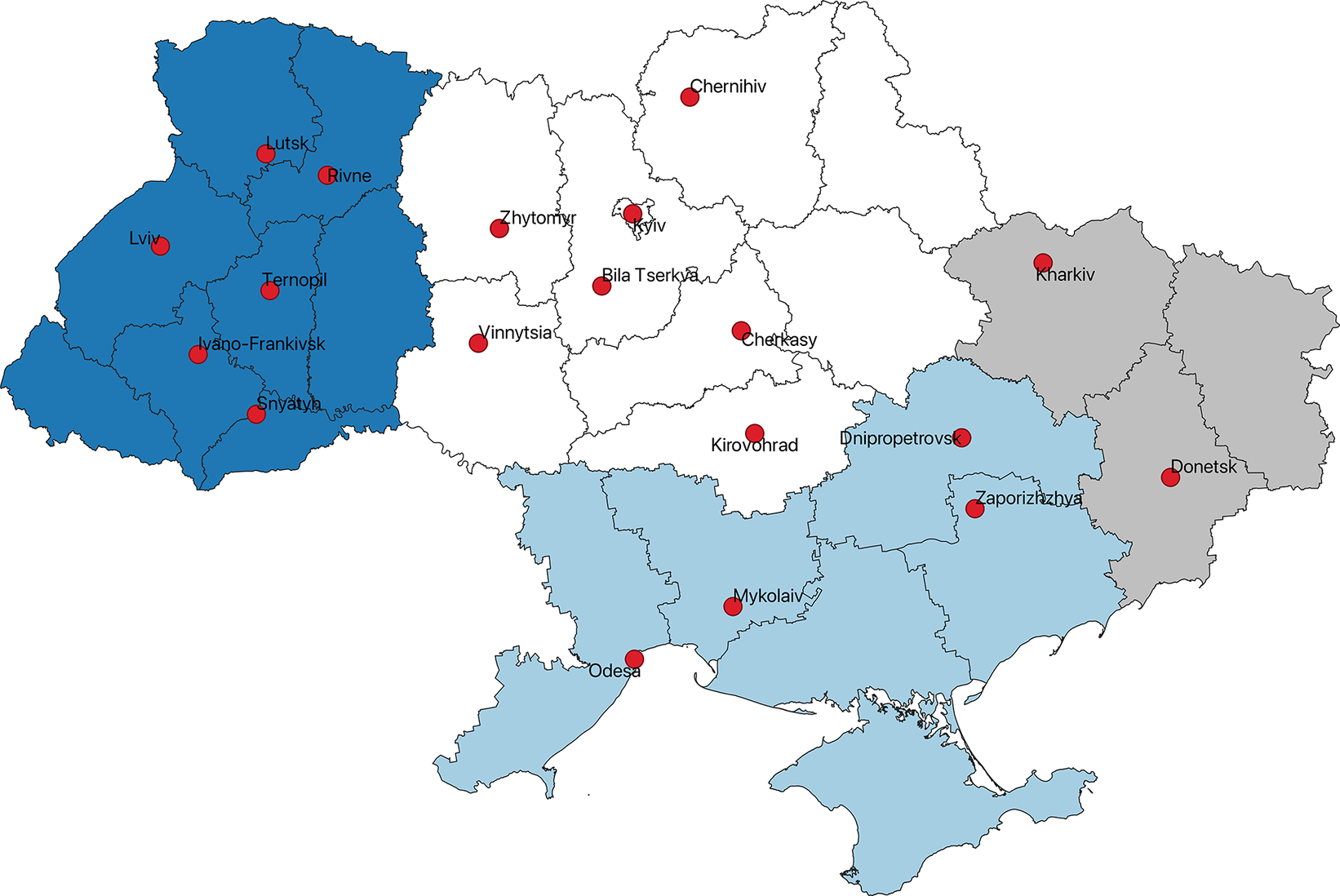

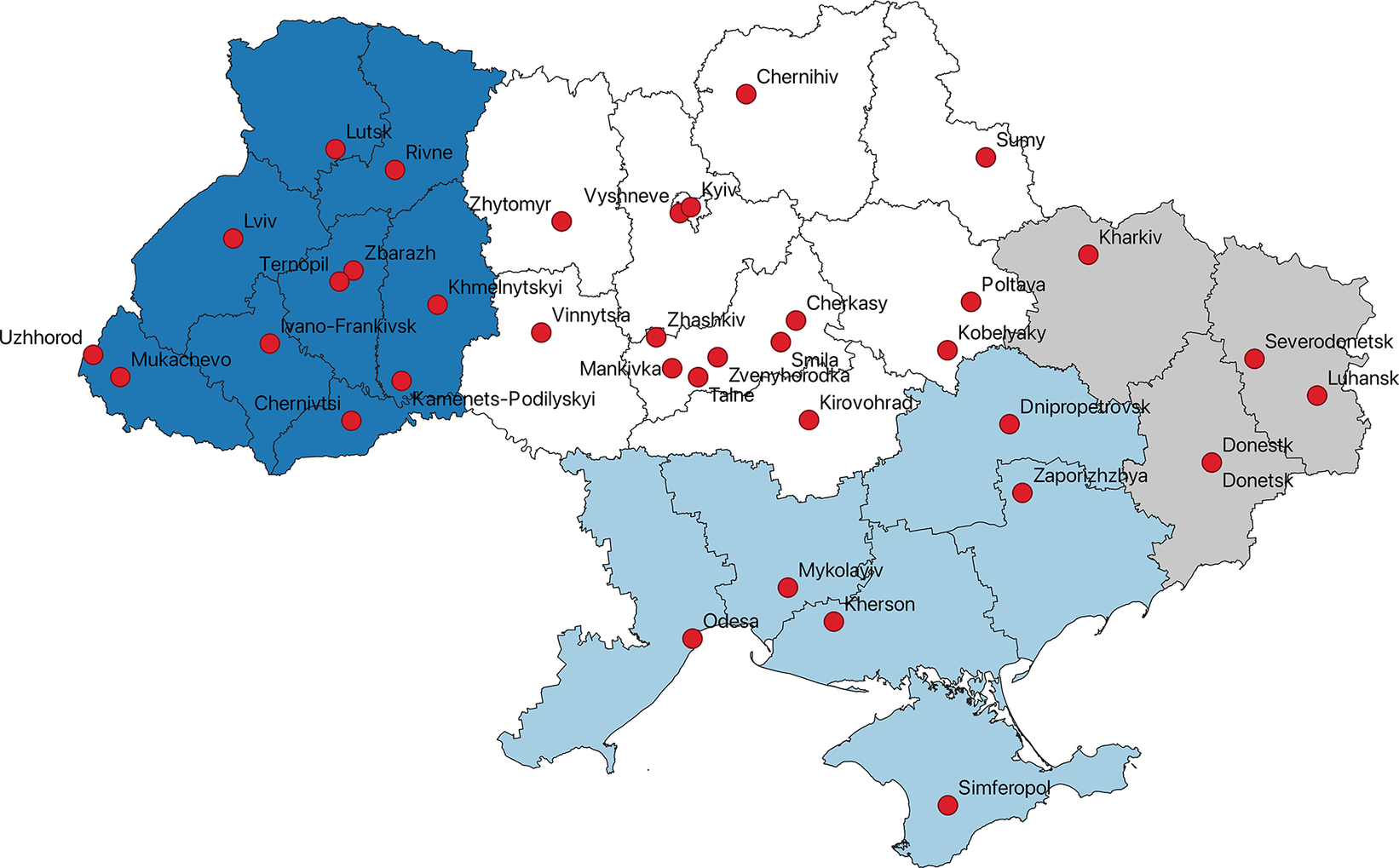

My findings suggest that over the course of the three mass mobilisations, the geospatial extent of mobilisation shifted. As visible in Figure 1, during the Revolution on Granite, although protests took place in 31 localities across the country, most mobilisation appears to have occurred in west Ukraine, and the westernmost oblasts of central Ukraine. During UBK (see Figure 2), protests were still nationwide but took place in fewer localities overall (19). However, protests were held in more oblast (regional) capitals in central Ukraine, such as Cherkasy and Kirovohrad (now Kropyvnytskyi). Figure 3 shows that during the Orange Revolution there was more widespread mobilisation across all macro-regions and oblasts compared to the previous two protests, with reports of protest events in 36 localities. The protests were also larger in general. Across all the mass mobilisations, oblast capitals in the west and central macro-regions tended to mobilise more frequently and on a larger scale than those in the south and east – even though, aside from Lviv, the ten most populous cities were situated in the latter regions (City Population 2020). Nevertheless, over time we see Kharkiv, Odesa and Dnipro in particular emerging as key sites of contention in the south and east, amidst comparatively low mobilisation in other cities in these macro-regions. Future research is needed to test the robustness of these findings, because as discussed above, the reporting of protests may have improved over time. Nevertheless, these results represent the first scholarly attempt to map these protests, represented visually in the maps below (the mapping of protest events via type are presented in Appendix 1 of this article). The colour coding of the regions represents Ukraine’s four macro-regions (east, centre, west and south) according to the widely used regional classification by Kyiv International Institute of Sociology.Footnote 6 Given the notorious unreliability of data on protest size (Biggs Reference Biggs2018), and this article’s focus on protest location, these maps do not distinguish between protests of different sizes.

Figure 1. Locations of protest events during the Revolution on Granite, late September – 17 October 1990 (Source: author).

Figure 2. Location of protest events during the Ukraine without Kuchma protests, 15 December 2000 – late March 2001 (Source: author).

Figure 3. Locations of protest events during the Orange Revolution, 22 November 2004 – 27 December 2004 (Source: author).

But what explains the apparent geographic shifts in the scope of these protests over time? My analysis of the actors and networks involves suggests that as anticipated, the engagement and activity of activist networks over time may align with changes in the dispersion of protest across space.

The Revolution on Granite: National-democratic networks and developing student collaboration

During the Revolution on Granite, there was a deliberate effort by student and activist networks to mobilise support across Ukraine’s regions. National-liberation and pro-democracy civic and dissident organisations played a key role in organising protest events in late September 1990, using their networks to mobilise and prime the regions for later, large-scale protest. Meetings and rallies against the Union Treaty, overseas military service, and the politicisation of the security services were held throughout Ukraine. The extent and size of protest events varied: protests were widespread in west Ukraine, extending to smaller towns and villages; in central Ukraine, most regional capitals mobilisedFootnote 7; in the south, smaller protests took place in Odesa, Mykolaiv, Kherson and DniproFootnote 8; and in the east a rally was held in Kharkiv and a picket in Donetsk (Rukh 1990e, 1990o). My analysis reveals that most of these events were organised by groups such as Rukh, the Society of Ukrainian Language, or the Ukrainian Republican partyFootnote 9. Although some of these organisations had networks of local branches across the country, many of them originated from and had a stronger presence in western and central Ukraine (Marples Reference Marples2019; Berezin Reference Berezin2018). This may in part account for the lower levels of mobilisation in southern and eastern Ukraine. Where protests did take place in these regions, workers and unions may have played more of a role, raising grievances over wages or workplace closures alongside those against the Union Treaty (Rukh 1990k, 1990o). These regional events laid the groundwork for an All-Ukrainian rally in Kyiv on 30 September 1990 attended by 100,000 protesters who had travelled from across the country (Rukh 1990p).

As protests moved into their second phase, in October, student networks became crucially important. The Lviv and Kyiv Student Brotherhood associations led the organisation of student hunger strikesFootnote 10 (Petrenko Reference Petrenko2017). On 2 October 1990, three hundred students from across Ukraine took to the central square in Kyiv to pitch tents, and one hundred began a hunger strike (Rukh 1990b)Footnote 11. Youth in cities across Ukraine had been actively collaborating and preparing in the preceding weeks and months: student activists had visited each other in Lviv, Odesa, Donetsk, and Kyiv (Kovalyk Reference Kovalyk2017). This activity built on student organisation emerging nationwide in the late eighties, which united under umbrella organisations such as the Ukrainian Student Union, founded in 1989 (Kovalyk Reference Kovalyk2017; Petrenko Reference Petrenko2017; Studway 2020). These student networks mobilised in early October and numbers in Kyiv swelled as students from across Ukraine travelled to the capital to join the hunger strike or show support (Burmaka Reference Burmaka2018; Berezin Reference Berezin2018). Into the second week of October, students began to send representatives to towns in the south and east, to disseminate information and rally greater support (Khymych and Chayka Reference Khymych and Chayka2010). Meanwhile, following rumours about the destruction of the tent camp, on 8 October, ten thousand Kyivites turned out to protect the students (Rukh 1990c). These two factors corresponded with and potentially contributed to an expansion in the geography of the protests; subsequent rallies proliferated in other localities, particularly in cities both large and small in central and western Ukraine.Footnote 12 Mobilisation was not entirely absent in the east either, with young people in Donetsk forming a human chain and hunger strike on Lenin square (Rukh 1990h). Overall, 100,000 students mobilised, an estimated twenty percent of Ukraine’s student population (Ostrovskyi and Chernenko Reference Ostrovskyi and Chernenko2000), demonstrating the power of these student networks.

The student and dissident leaders believed in the importance of promoting cross-cleavage collaboration. They made a concerted effort to mobilise workers and miners in south and east Ukraine, demonstrating nationwide support for the cause and increasing pressure on the government (Khmara Reference Khmara2018; Volynko Reference Volynko2017; Kanafotskyi Reference Kanafotskyi2018). Miners had engaged in mass strikes in summer 1989 and 1990,Footnote 13 and represented an organised and powerful force for political influence. Student activists reached out to Trade Unions (Kanafotskyi Reference Kanafotskyi2018) and travelled to Donetsk to make contact with Miners’ Unions (Volynko Reference Volynko2017). Well-known dissidents such as Stepan Khmara also travelled to eastern and southern citiesFootnote 14 to encourage businesses, workers and miners to support the student action (Khmara Reference Khmara2018). However, these attempts to collaborate with miners and other workers were not entirely successful, with interference by the authorities preventing a formal association between RoG activists and the Donetsk Strike Committee (Volynko Reference Volynko2017). During the 1 October national strike against the Union Treaty, strikes and rallies took place across the country, but west Ukrainian workers and businesses showed the strongest support, with over 90% of businesses in Ternopil and 65-70% in Lviv reported on strike (Rukh 1990a, 1990b). In contrast, there was no widespread mobilisation of workers or miners in the south or east. Nevertheless, there were some expressions of support – the leaders of the Donetsk miners’ strikes sent a telegram to Kyiv expressing their solidarity with the students (Kowal et al. Reference Kowal2019). And, a RoG student leader, Oles Doniy, claims that the mounting threat of factory and transport workers mobilising in mid-October contributed to the government giving in to the students’ demands (Khymych and Chayka Reference Khymych and Chayka2010). While cross-cleavage collaboration was limited, it may have borne some fruit.

On 17 October 1990, as the student hunger strikers weakened, and widespread mobilisation was occurring, particularly in western Ukraine,Footnote 15 student protesters in Kyiv reached a compromise with the government and ended their hunger strike, claiming victory and ending the RoG (Rukh 1990l). Student activists and dissident networks had sought to facilitate mobilisation in multiple locations throughout Ukraine, with their networks strongest in western regions. This may help explain why protest was more widespread there, despite the fact that there were more students in south and eastern Ukraine (Bilenky Reference Bilenky2021). Aware of their limitations, these networks actively sought out cross-cleavage and cross-national collaboration, with limited success. While the protests did get the government to agree to some key demands, the extent of this nationwide mobilisation was nevertheless limited. For more widespread protest, greater cross-cleavage and cross-national collaboration would be needed.

Ukraine Without Kuchma: A broad spectrum of party networks collaborate

During the Ukraine Without Kuchma protests, western Ukraine remained the region with the largest and most frequent protest eventsFootnote 16. Mobilisation occurred throughout Ukraine once again, this time with new oblast capitals mobilising in the centre of the country – although overall protests took places in fewer localities than during the RoG. A broad spectrum of political parties and civic and social movement organisations, united by a desire to unseat Kuchma, collaborated to mobilise their supporters (Ukrainska Pravda 2001k, 2001i, 2001j). These included Communist and Socialist parties; national democratic and centre-right parties such as the Ukraine Republican party, Ukraine Conservative Republican party, Rukh Footnote 17, Ukrainian Christian-Democratic Party, Sobor, and Batkivshchyna; and far-right groups such as Tryzub and the UNA-UNSO (Ukrainska Pravda 2001k, 2001i, 2001j). Thus, across Ukraine, an unlikely combination of students, pensioners, liberals, intelligentsia, communists, socialists, and nationalists all participated under the same umbrella of UBK, united perhaps only by their desire to see Kuchma resign.

This extensive network of organisations involved in UBK may have contributed to the diffusion of protest events beyond Kyiv, as there was no single party or organisation which enjoyed widespread support across all Ukraine’s regions. Cross-cleavage collaboration worked to mobilise support across the country: left-wing parties and their supporters appear to be more involved in organising and participating in protest events in south, central and east Ukraine compared to west Ukraine, where national democratic parties and right-wing groups dominated (Ukrainska Pravda 2000b, 2001b, 2001j). However, this variation must not be overstated, as cross-cleavage collaboration also occurred within individual cities as a mix of parties and their supporters collaborated. Notable examples include Kharkiv, where socialists, UNA-UNSO (right wing) party members, and independent activists went on hunger strike together (Ukrainska Pravda 2001j), and Odesa, where activists from the Communist and Socialist Parties, the Union of Soviet Officers, the Green Party, and national-democratic parties and civic organisations jointly participated in a rally and picket on 6 February 2001 (Ukrainska Pravda 2001n). However, whilst potentially contributing to the dissemination of protest across Ukraine, this broad cross-cleavage coalition also had its disadvantages.

Onuch (Reference Onuch, Stoltzfus and Osmar2021) has noted that different groups organising the protests did not collaborate as well as in 1990, and were divided by ideology and personality clashes amongst the various leaders. UBK began on 15 December 2000, and initially protest events outside of Kyiv were few, and small in sizeFootnote 18. The Kyiv tent camp was dismantled after a court ruling on 23 December (Ukrainska Pravda 2000b). From 14 January, the different groups attempted to better coordinate the ‘second wave’ of protests, pooling their resources (Onuch Reference Onuch, Stoltzfus and Osmar2021), and protest events in the regions started attracting larger numbers, and taking place in new locations. Before mid-January, the majority of tent camps and rallies beyond Kyiv were small, largely comprising of opposition party members and dedicated activists. Mobilisation primarily took place in central Ukraine, where opposition to Kuchma during the elections had been strongestFootnote 19. From mid-January, when coordination improved, protest events in the regions started attracting larger numbers, and occurring in more locations. The largest rallies were in central and west Ukraine, with meetings of around 4000 protesters in Cherkasy and Ternopil (Ukrainska Pravda 2001j).Footnote 20 Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that repression may have also played a part in this expansion of protest – the violent dispersal of Kharkiv’s tent camp on 11 January also appeared to spur the mobilisation of tent camps in more cities in west and southern Ukraine (Ukrainska Pravda 2001c)Footnote 21. Into February, we can also see that a complex combination of cooperation, repression, and challenges in collaborating across diverse groups corresponded with shifts in the geospatial extent of protest.

In February 2001, the protest coordinators in Kyiv launched a conscious effort to unite activists from across the country in large protests in the capital (Ukrainska Pravda 2001f, 2001h), similar to the 30 September RoG march. Tent camps from across Ukraine relocated to Khreshchatyk street in central Kyiv, where rallies of activists began numbering in the thousands (Ukrainska Pravda 2001n, 2001h). In one striking incident, protesters from Zhytomyr, 140 kilometres west of Kyiv, hiked en masse to the capital, led by a ram wearing an ‘I voted for Kuchma’ sign (Ukrainska Pravda 2001f). Protests were concentrated in Kyiv, but rallies in the low hundreds continued elsewhere, including in Dnipro, Kharkiv and Odesa (Ukrainska Pravda 2001n, 2001h, 2001e). Perhaps it was hoped that uniting protesters in Kyiv would maximise the impact of the protests and increase pressure on Kuchma to resign.

However, the different networks struggled to maintain their cooperation after repression in Kyiv on 1 March (Onuch Reference Onuch, Stoltzfus and Osmar2021), when the Kyiv tent camp was attacked by police. Right-wing groups such as Tryzub, although in the minority of protesters, caused trouble in Kyiv and the various groups were divided over how to react (Kuzio Reference Kuzio2007; Onuch Reference Onuch, Stoltzfus and Osmar2021). Violence between police and protesters broke out during a subsequent march on 9 March. The use of repression provoked a backlash, and demonstrations condemning the use of police violence took place in a number of other cities (Ukrainska Pravda 2001p, 2001d, 2001g). Notably in Lviv, over five thousand students participated in a strike and demonstrations between 13–15 March (Ukrainska Pravda 2001o, 2001q). Nevertheless, hit by the arrests of over two hundred activists in Kyiv, and struggling to reach a consensus between different groups on how to proceed, UBK faded away, its goals unachieved.

In studying UBK, we can see that the collaboration of different networks is associated with protest taking place across Ukraine. Activist groups and parties from across the political spectrum engaged in mobilisation throughout the country. However, challenges in coordinating across these diverse groups may have contributed to mobilisation being less widespread than during the RoG. We might have expected protest in 2000-2001 to be significantly more diffused than in 1990: by 2000, activist organisers and protesters could utilise mobile phones and internet to communicate and share information about their campaigns. The protests were also more widely covered in the media, spreading information about UBK throughout Ukraine. And yet, fewer locations mobilised in 1990, as the various political parties organising the protests encountered challenges in co-ordination and agreeing on tactics. Still, it is crucial to note that I cannot definitively confirm whether difficulties in managing cross-cleavage collaboration shaped a reduction in the geospatial scope of protest. A number of other intervening factors changed between 1990 and 2000, such as the grievances of the protests themselves, which focused on the ousting of one political figure, rather than reforms which would secure greater democracy and independence for the entire country. Nevertheless, these findings about nationwide protest and diverse activist networks are still important: they highlight the ways in which mass mobilisation was evolving in independent Ukraine, and the role diverse activist groups were playing in leading protest movements, despite the challenges they faced.

The Orange Revolution: Primed and prepared nationwide networks

Several years after UBK, mobilisation expanded much further into regional localities during the Orange Revolution. This expansion corresponds with efforts by a network of youth activists across Ukraine to organise and prepare in advance of the 2004 Presidential elections. Much effort had gone into priming these youth networks throughout the country. The key youth organisation, Pora (meaning ‘It’s time’), was all-national from its launch: on 28 March 2004, a sticker campaign ‘What is Kuchmism?’ was launched simultaneously in 17 regions (Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group 2004; Ukrainska Pravda 2009)Footnote 22. The broader civic campaign aimed to cover the entire territory of Ukraine, and activists and local branches were established in all oblasts (Pora 2004). Trainings for youth activists, and civic campaigns, were conducted throughout the country: by the beginning of November, Pora had organised over 170 street actions in 53 settlements, including some campaigns with simultaneous events across multiple regions (Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group 2004). These primed networks then mobilised following the election results. Students were significant participants in many of the regional rallies supporting Yushchenko (Ukrainska Pravda 2004h, 2004i). They were also responsible for setting up tent camps in cities such as Rivne and Kharkiv (Ukrainska Pravda 2004h), and an attempt to set up a tent camp in DonetskFootnote 23. Nikolayenko (Reference Nikolayenko2017, 172) suggests that over 17% of Ukrainian youth participated in protest events in the regions, demonstrating the efficacy of Pora’s work. All this suggests that youth activist networks sought to play a role in facilitating mobilisation throughout Ukraine.

These youth and student networks worked in cooperation with a cross-cleavage coalition of opposition party networks and other groups. In regional cities, ‘coordinating councils’ for the opposition were created, which bought together diverse parties ranging from the Socialist Party to the centre-right Batkivshchyna (Ukrainska Pravda 2004h). Coalitions of activists also worked together to mobilise citizens beyond Kyiv and western Ukraine. In December, the ‘Train of Friendship’ tour saw a motorcade of activists, journalists, artists, filmmakers and musicians touring throughout fourteen central, southern and eastern oblasts (Ukrainska Pravda 2004g). This ‘informational tour’ sought to promote contact between Ukraine’s regions, overcome local media censorship, and support territorial unity, freedom of speech and democratic values. Workers also mobilised on a greater scale than before, particularly in central and western Ukraine. Large manufacturing plants staged strikes in support of Yushchenko, including Chernivtsi Car Factory, Ivano-Frankivsk ‘Lukor’ chemical plant, and Vinnytsia factory ‘Keramik’ (Ukrainska Pravda 2004h). As during UBK, together these different networks of workers, students, political parties, and activists spanned the country. Moreover, Onuch (Reference Onuch, Stoltzfus and Osmar2021) argues that these networks had learnt from the failures of UBK and worked to better coordinate their efforts and unite behind a single message and candidate. The nature of the available data means that it is not possible to definitively claim that these diverse networks and enhanced cooperation helped to spread more protest events throughout Ukraine’s regions. However, these networks certainly sought collaboration and worked to mobilise protesters in more locations.

Whether or not precisely due to these activist networks, both in terms of the number of locations and the sizes of regional protests, the Orange Revolution represented a clear expansion in mobilisation compared to the previous mass protests. Mobilisations took place in every regional capital of Ukraine. West Ukraine was still the site of the most frequent and largest protests outside Kyiv, with six of the eight western capitals witnessing rallies of over 10,000.Footnote 24 Central Ukraine also mobilised extensively: rallies of 5,000-10,000 took place in every regional capital (Korrespondent 2004; Radio Svoboda 2004; Ukrainska Pravda 2004h, 2004f, 2004d, 2004c, 2004j) Nevertheless, rallies of over 10,000 were also held in southern and eastern cities including Dnipro, Mykolaiv, Kharkiv and Odesa, with smaller protests elsewhereFootnote 25 (Ukrainska Pravda 2004h). The size and breadth of these protests in the east and south is particularly significant given that they were occurring in cities where the majority would not have voted for Yushchenko, and where protesters faced intimidation, threats, and even violence.Footnote 26

Whilst it is important to acknowledge that Ukraine’s evolving media landscape means that coverage of the Orange Revolution’s regional protests was likely better than the previous two mass mobilisations, I remain confident that the overall patterns identified in my data hold true. The Ukrainska Pravda and Rukh newswires used for PEA sources for UBK and the RoG respectively were effectively activist media, due to their close ties to the protests, and thus had a keen interest in reporting events throughout the country as closely as possible. KGB reports for the RoG would also have sought to gather comprehensive information on the protests, and were not subject to the censorship or reporting biases of the media. The usage of activist interviews supplemented the information provided by these sources.

In the same way, data limitations mean that I remain cautious about claiming that the activity and cross-cleavage collaboration of activist networks was the key factor driving the geospatial spread of protest between 1990 and 2004. A variety of other factors were also at play, such as the increased usage of mobile phones and the internet, as discussed above, as well as differences in grievances across the protests. For example, we know that falsified elections can be a particularly motivating trigger to mobilise protesters on a massive scale (Tucker Reference Tucker2007). Nevertheless, what this article has done is note that a variety of activist networks, including students, political parties, and civic groups certainly played a role in Orange Revolution protests in Ukraine’s regions. There were deliberate attempts by these student and activist networks to encourage mobilisation in regional localities, particularly those in the east and south of Ukraine which were less active in past mass mobilisations. Definitively proving whether these efforts were crucial in driving the geospatial expansion of protest remains a task for future research.

Conclusion

The aims of this article were to identify regional patterns of protest during three moments of mass mobilisation in Ukraine, to examine how activist networks contributed to geospatial shifts in protest across space over time, and to provide context for research into more recent and future mass mobilisation in Ukraine. I anticipated that as the engagement and activity of activist networks changed over time, this may have shaped shifts in the geospatial extent of protest, across subsequent protest waves.

Presenting novel empirical findings on regional mobilisation during the RoG, UBK, and the Orange Revolution, I have suggested that whilst protest took place throughout Ukraine during all three mass mobilisations, between the RoG and the Orange Revolution it expanded to more locations, from 31 to 36. In the intervening period, protests were held in fewer locations during UBK (19), although new locations in central Ukrainian oblast capitals mobilised. With each subsequent protest wave, more frequent and larger protest events occurred in west Ukraine, and over time mobilisation increased in frequency and size in central, south, and east Ukraine. These results should be interpreted with care, as the nature of the changing Ukrainian media from 1990-2004 means that the accuracy of reporting protest events may have improved over time. Nevertheless, the usage of activist and KGB sources for earlier events means that I am confident that the broad patterns identified are accurate. The identification of these key patterns makes a valuable contribution to our knowledge about the regional dimensions of these protest waves. Future studies can build on this work, including systematic analyses of additional sources to capture more details about these protest events, as well as additional events that may have been missed. In future, I plan to develop and publish such a comprehensive dataset for these three mass mobilisations.

My analysis has shown that these geospatial patterns of protest align with the changing dynamics in activist networks and cross-cleavage coalitions over subsequent protest waves. I have demonstrated that student and national-democratic dissident organisations worked to mobilise Ukrainian cities during the Revolution on Granite, but with limited success in engaging with miners’ and workers’ networks in southern and eastern Ukraine. Then, during UBK, a broad coalition of political parties worked together to try and unseat Kuchma, including those with greater popularity in the south and east; however, the sheer diversity of these groups made coordination and collaboration challenging. Come the Orange Revolution, youth groups such as Pora worked hard to organise and mobilise across all Ukraine’s regions in the run up to the elections, priming mobilising structures. Opposition parties and SMOs also sought to learn from UBK and unite more cohesively behind one candidate, in order to bring the Orange Revolution to as much of Ukraine as possible. Nevertheless, whilst I have identified these activist networks’ undertakings, it remains the task of future research to investigate whether these activities were the primary cause of the geospatial variation of protest over time which I have uncovered. More systematic tracing of key SMOs would help to further clarify the role of activist networks. Studies are also needed to investigate the role of other factors, such as how the usage of technology and new forms of media may have facilitated more widespread protest. Social media were still in their infancy by the time of the Orange Revolution, but future works could examine how mobile phones, the internet, and email were utilised by protesters and activists, and whether this helped facilitate increased geospatial protest. Repression is another factor that may have played a complex role in shaping protest – in some instances it appeared to provoke a backlash during UBK and the RoG, but in the case of UBK it may have brought protests to an end. Nevertheless, although unable to make definitive causal claims, this article has made an important contribution in identifying the work of domestic, activist actors in attempting to bring protest to locations across Ukraine.

As such, these findings provide valuable context for the Euromaidan protests of 2013-14, as well as ongoing anti-war mobilisation in Ukraine. This article makes clear that although it has previously received limited attention in scholarly research, Ukraine has a history of nationwide mobilisation. This nationwide mobilisation has been supported by wide-reaching, cross-cleavage coalitions of activists; and it is these kinds of networks which may help facilitate widespread protest across the country. Some work on the Euromaidan protests such as that by Channell-Justice (Reference Channell-Justice2019, Reference Channell-Justice2022), Onuch (Reference Onuch2014b), Onuch and Hale (Reference Onuch and Hale2022), Lokot (Reference Lokot2021) and Zelinska (Reference Zelinska2015, Reference Zelinska2016, Reference Zelinska2023) analyses or discusses protest events beyond Kyiv, acknowledging the role of local activist networks and the diversity of Euromaidan participants. It is hoped that this study will provide context for similar, future endeavours. Future studies of Ukrainian mobilisation should not neglect the regional dimensions of protest in the country, including those prior to the Euromaidan, nor the role played by Ukrainian activist networks.

At the time of writing this article, I was witnessing video footage emerging from southern and eastern Ukrainian cities in the spring of 2022, showing local residents bravely mobilising against armed, Russian invading forces. Some observers were surprised by such sights, that citizens in these regions would mobilise. This article has shown that on the contrary, those in Ukraine’s regions protesting against Russian invasion are the latest to mobilise in over thirty years of resistance in independent Ukraine. Ukrainian regional activist networks will have an important role to play in fighting back against Russian invasion, and rebuilding a better future for their country.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Olga Onuch, Stephen Fisher, and Paul D’Anieri for valuable feedback on this paper, and others who commented on an earlier draft at APSA in 2020. Whilst revising this paper, the author was supported by a Petro Jacyk Postdoctoral Fellowship in Ukrainian Studies at the Harriman Institute, Columbia University, and a Postdoctoral Research Fellowship at the Jordan Center, New York University. The author is also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for very helpful comments.

Financial support

The majority of this work was completed during a DPhil at the University of Oxford, which was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council [grant number ES/P000649/1] and a Balliol College Devorguilla Scholarship

Disclosure

None