1. Background

Health technology assessment (HTA) agencies play a role in the governance of certain health technologies, their scope varying by country and organisational mandate (Loblova, Reference Loblova2016; Sorenson and Chalkidou, Reference Sorenson and Chalkidou2012). When it comes to the governance of medical technologies (MedTech), different HTA agencies have different levels of involvement (Basu et al., Reference Basu, Eggington, Hallas and Strachan2024; Segur-Ferrer et al., Reference Segur-Ferrer, Molto-Puigmarti, Pastells-Peiro and Vivanco-Hidalgo2024; Fuchs et al., Reference Fuchs, Olberg, Panteli, Perleth and Busse2017). MedTech is defined inconsistently in the academic literature, but typically includes medical devices, digital health, and diagnostics (Europe, 2022). In most countries, HTA agencies’ role in MedTech governance is less established than their role in governing pharmaceuticals (Fuchs et al., Reference Fuchs, Olberg, Perleth, Busse and Panteli2019; Olberg et al., Reference Olberg, Fuchs, Panteli, Perleth and Busse2017). However, the role of HTA agencies in MedTech governance seems to be expanding, evidenced, for example, by the rapidly growing number of published HTA reports for medical devices (Ming et al., Reference Ming, He, Yang, Hu, Zhao, Liu, Xie, Wei and Chen2022). This highlights how the role of HTA agencies also evolves over time.

Some of the reasons why the role of HTA agencies may change over time is in response to technological innovation or political and institutional developments. At the European level, several institutional developments are currently influencing this role. With the introduction of the HTA Regulation (HTAR) (Parliament, 2021a), HTA agencies in the European Union (EU) are expected to carry out joint clinical assessments (JCA) of certain high-risk medical devices (Tarricone et al., Reference Tarricone, Ciani, Torbica, Brouwer, Chaloutsos, Drummond, Martelli, Persson, Leidl, Levin, Sampietro-Colom and Taylor2020). Other relevant regulations include the Medical Devices Regulation (MDR), the In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices Regulation (IVDR), and the Artificial Intelligence (AI) Act (Parliament, 2017a,b, 2021b). It is expected that these regulations will increase the focus on the safety and quality of (certain) MedTech prior to market entry (Wilkinson and van Boxtel, Reference Wilkinson and van Boxtel2019). Although initial reflections seem somewhat disappointed (Shatrov and Blankart, Reference Shatrov and Blankart2022; Hulstaert et al., Reference Hulstaert, Pouppez, Primus-de Jong, Harkin and Neyt2023; Jarman et al., Reference Jarman, Rozenblum and Huang2021), these developments could increase the amount of evidence available for the assessment of MedTech, which could in turn further amplify EuropeanFootnote 1 HTA agencies’ role in MedTech governance.

Despite this apparent amplifying role for HTA agencies in the governance of (high-risk) MedTech, there is still debate in the academic literature about the applicability of existing HTA approaches to MedTech (Bluher et al., Reference Bluher, Saunders, Mittard, Torrejon Torres, Davis and Saunders2019; Enzing et al., Reference Enzing, Knies, Boer and Brouwer2021). Scholars note that HTA of MedTech is challenging for a number of reasons. Relevant literature reflects for example on the different characteristics of MedTech compared to pharmaceuticals, including scarce evidence, incremental or iterative development, and MedTech user learning curves (Fuchs et al., Reference Fuchs, Olberg, Panteli, Perleth and Busse2017; Cangelosi et al., Reference Cangelosi, Chahar and Eggington2023; Fuchs et al., Reference Fuchs, Olberg, Perleth, Busse and Panteli2019; Drummond et al., Reference Drummond, Griffin and Tarricone2009; Tarricone et al., Reference Tarricone, Torbica and Drummond2017). Scholars discuss how MedTech are often adopted and disseminated before their value has been demonstrated in a standardised manner (Abrishami et al., Reference Abrishami, Boer and Horstman2014), partly as a result of their fragmented regulatory system (Fuchs et al., Reference Fuchs, Olberg, Panteli, Perleth and Busse2017; Olberg et al., Reference Olberg, Fuchs, Panteli, Perleth and Busse2017). This complicates the role of HTA agencies, for example because it is more difficult to remove products from reimbursement once they are embedded, than to deny reimbursement at market access (Calabro et al., Reference Calabro, La Torre, de Waure, Villari, Federici, Ricciardi and Specchia2018; Haas et al., Reference Haas, Hall, Viney and Gallego2012; Kamaruzaman et al., Reference Kamaruzaman, Grieve and Wu2022). These academic discussions give the impression that it may be difficult for HTA agencies to govern (some) MedTech.

Recently, the definition of HTA has been updated (O’Rourke et al., Reference O’Rourke, Oortwijn and Schuller2020). Although this updated definition has also been met with some criticism (e.g., Culyer and Husereau, Reference Culyer and Husereau2022; Charlton et al., Reference Charlton, DiStefano, Mitchell, Morrell, Rand, Badano, Baker, Calnan, Chalkidou, Culyer, Howdon, Hughes, Lomas, Max, McCabe, O’Mahony, Paulden, Pemberton-Whiteley, Rid, Scuffham, Sculpher, Shah, Weale and Wester2024), it remains widely cited and serves as a common point of reference in much of the contemporary HTA literature. In addition to simplifying the language used in the definition, one of the guiding principles for updating the definition was to include explicit reference to the multidisciplinary nature of HTA. Although earlier definitions already referred to HTA being performed by interdisciplinary groups, interdisciplinarity was not part of the definition’s core sentence. The 2020 update purposefully foregrounded this aspect, starting the definition with ‘HTA is a multidisciplinary process’, to underline this interdisciplinary nature of HTA, partly as a response to HTA often being defined more narrowly in practice (O’Rourke et al., Reference O’Rourke, Oortwijn and Schuller2020). Given the expectation of an increasing role for European HTA agencies in the governance of MedTech, the contested nature of the applicability of HTA approaches to MedTech, and the explicit focus on multidisciplinarity in the updated definition of HTA, it would be relevant to understand how the role of European HTA agencies in relation to MedTech is discussed across academic disciplines. The way this role is framed both reflects and influences the governance of technologies, shaping perceptions, legitimising decisions, and guiding action (Blume, Reference Blume2009; Ciani et al., Reference Ciani, Armeni, Boscolo, Cavazza, Jommi and Tarricone2016; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Selin and Scott2021; Burau et al., Reference Burau, Nissen, Terkildsen and Vaeggemose2021; Charlton and DiStefano, Reference Charlton and DiStefano2024). Literature on the role of HTA agencies tends to focus on pharmaceuticals, as the role of HTA agencies is more established in this context (Oortwijn et al., Reference Oortwijn, Mathijssen and Banta2010; Shah et al., Reference Shah, Barron, Klinger and Wright2014; Ciani and Jommi, Reference Ciani and Jommi2014).

An analysis of the framing regarding MedTech could thus be instructive for further understanding and developing the policy framework for MedTech in Europe, by clarifying underlying assumptions that shape assessment practices and regulatory decisions. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to examine how the role of European HTA agencies in relation to MedTech has been framed in academic discourse over time. Taking a historical-discursive perspective allows us to trace shifts in how HTA agencies responsibilities, methods, and institutional positioning are conceptualised. This analysis serves three key audiences: (i) HTA agencies and regulators, who can use the typology as a reflexive tool for rethinking their evolving role in a changing technological and regulatory landscape; (ii) policy-makers, who require a deeper understanding of why methodological debates surrounding MedTech persist and how they relate to competing visions of HTA agencies purpose; and (iii) researchers, who can use the identified discourses to trace conceptual and normative developments and to better situate their own work within ongoing debates. This is the first time that discourse on the role of HTA agencies in relation to MedTech has been reviewed in the academic literature. We answer the following research question: What are the different academic discourses on the role of European HTA agencies in relation to MedTech? To answer this question, we combine a comprehensive literature search and discourse analysis, going beyond a summary of findings to provide an interpretation of the material. We conclude with policy implications and research recommendations.

2. Methods

2.1. Data collection

We conducted a comprehensive search to identify relevant literature. A search string was developed by an experienced information specialist (WB) together with the first author (RM). The search combined terms for medical technology innovations and the name of national and regional HTA agencies in Europe (Box A in Supplementary Materials). The search was limited to articles published in English, and conference abstracts were excluded. No publication date limits were applied, as we aimed to capture the full breadth of relevant literature, including both recent work and the historical development of relevant ideas regarding the role of early HTA agencies. Initially, drug therapies, medicine, and pharmaceuticals were excluded by the search string. However, because of the risk of losing articles that described both innovative MedTech and innovative pharmaceuticals, this part of the search string was removed, and it was decided to manually eliminate those articles that focused solely on pharmaceuticals during the literature selection process. Articles that focused on both pharmaceuticals and MedTech were included. We conducted a search on May 2, 2024, on Embase.com, Medline Ovid, Web of Science, Scopus, CINAHL (EBSCOhost), and One Business (ProQuest) (Bramer et al., Reference Bramer, de Jonge, Rethlefsen, Mast and Kleijnen2018; Bramer et al., Reference Bramer, Rethlefsen, Kleijnen and Franco2017). We used referencing software (Endnote version X9) to manage the retrieved documents and to remove duplicates (Bramer et al., Reference Bramer, Giustini, de Jonge, Holland and Bekhuis2016).

2.2. Data analysis

We used a discourse-analytic approach to analyse the selected articles (Hajer and Versteeg, Reference Hajer and Versteeg2005). We followed Hajer and Versteeg’s (Reference Hajer and Versteeg2005) definition of a discourse as ‘an ensemble of ideas, concepts, and categories through which meaning is given to social and physical phenomena, and which is produced and reproduced through an identifiable set of practices’ (p.300). In our case, we identified the ways in which meaning is given to key concepts including HTA, MedTech, the role of HTA agencies, and evidence. In our case, the set of practices through which meaning is produced and reproduced consisted of writing an academic article, conceptualising the terms in that article and choosing a journal in which to publish. Although articles could theoretically reflect more than one discourse, we coded at the article level, meaning that each article was assigned to the most dominant discourse in the article. Importantly, inclusion in a discourse does not necessarily imply that an article explicitly endorses that position, but that its framing, assumptions, and interpretive direction are consistent with that discourse.

A central assumption of discourse analysis is that language shapes worldviews. Therefore, metaphors constituted an important part of our analysis. Describing HTA as a ‘piecemeal approach’ (Campbell and Knox, Reference Campbell and Knox2016) or a ‘general toolkit’ (Quentin et al., Reference Quentin, Carbonneil, Moty-Monnereau, Berti, Goettsch and Lee-Robin2009), or describing the role of HTA agencies as ‘forming a bridge between stakeholders’ (Gauvin et al., Reference Gauvin, Abelson, Giacomini, Eyles and Lavis2010) or ‘starting an assault on Mount Olympus’ (Smith, Reference Smith1999), are important clues to understand how HTA and the role of HTA agencies is interpreted. What’s more, dominant discourses can lead to the exclusion of other, less dominant, discourses (Bröer, Reference Bröer2008), so understanding different discourses and their degree of dominance can be elucidating in understanding policy decisions and how they play out in practice. Notably, an academic discourse differs from an academic theory. Discourses concern shared language to describe phenomena, whereas academic theories concern concepts to explain phenomena. Members of a discourse become trained in the language of a specific set of theories, for example, utilitarianism is a theory on the maximisation of health benefits given a limited budget (e.g., (Marseille and Kahn, Reference Marseille and Kahn2019; Goetghebeur et al., Reference Goetghebeur, Wagner, Bond and Hofmann2015), which could be part of a discourse on health budget distribution.

Our analysis was conducted in phases. First, articles were reviewed for eligibility by the first author (RM). Articles were included according to the criteria listed in Box 1. In cases of doubt, articles were discussed with authors BG and DD. In addition, a subset of 20 articles were blindly co-assessed for eligibility by authors BG and DD, a process that confirmed consistency in inclusion. Snowballing was not part of data collection, however, some articles found in the reference list of included articles were used for further reflection in the discussion section. Then, the first author coded a sample of 20 articles inductively using qualitative analysis software (Atlas. Ti 9.0) (coding list in Box B in Supplementary Materials). After discussing these articles with BG and DD, we drafted a list of coding questions, coding for (1) the interpretation of the role of HTA agencies; (2) the definition and framing of MedTech; (3) narratives around evidence; (4) the responsibilities of and relationships between stakeholders, and (5) relevant metaphors (Box C in the Supplementary Materials). These were used for a full round of coding, in MS Excel. The authors critically interrogated the analytical themes that emerged from our data until consensus was reached on the characteristics of the discourses. Finally, the number of articles per discourse were counted, as well as the countries discussed within the articles in each discourse and the distribution of the articles across time.

Box 1. Eligibility criteria

An article will be included in the pool of selected articles if its title/abstract meets the following criteria:

-

a. Title and/or abstract include information on (innovative) medical technologies either in general or one or more than one specific product used in preventive, curative, or rehabilitative care;

-

b. Title and/or abstract include information on the role, mandate, function, policy, or positioning of national or regional HTA agencies with regards to these technologies. The HTA agencies include those that are part of a national or regional/county government or otherwise legislatively designated independent (non-governmental) agencies in Europe;

Exclusion criteria:

-

a. Focus on specific HTA methodologies and not on the role of HTA agencies;

-

b. Focus solely on (innovative) medicinal products/pharmaceutical industry;

-

a. If an article focuses on innovative medical technology AND (innovative) drugs/pharmaceutical industry, it will be included;

-

c. Focus on technologies that are not medical-related (e.g., solely lifestyle, food, or veterinary technologies);

-

d. Focus on the role of HTA agencies outside of Europe;

-

e. Focus on hospital based HTAs rather than national HTA agencies.

Whenever the first reviewer is unsure about whether an article qualifies for inclusion, article will also be checked by a second and a third reviewer, and the article’s inclusion will be jointly discussed.

3. Results

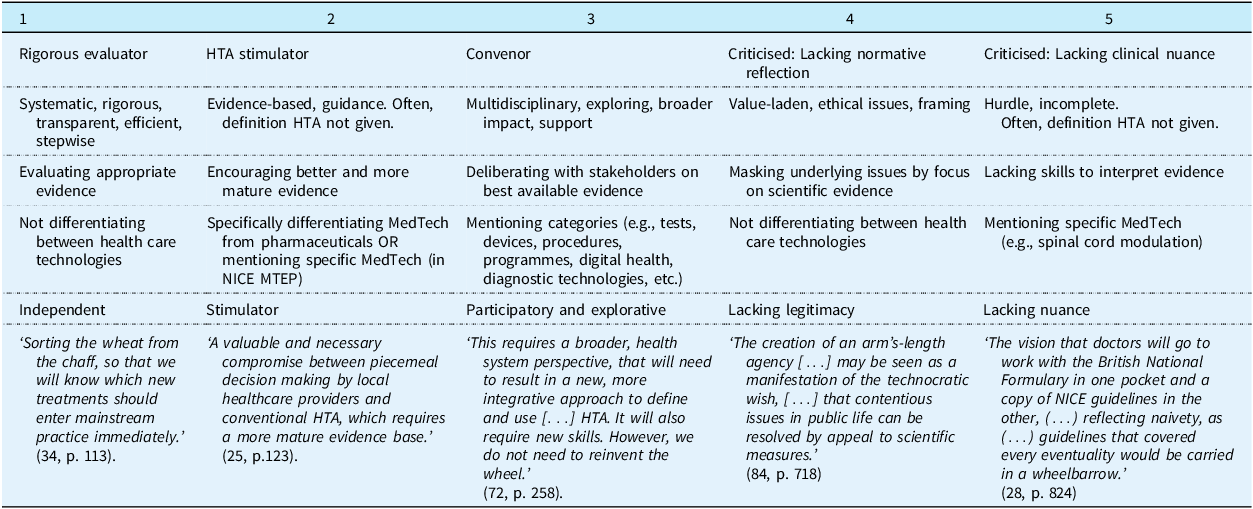

In total, 119 articles were included (see Figure 1), from which we constructed 5 discourses. Table 1 shows the distribution of the included articles across discourses. Figure 2 shows the count of articles per discourse over time. We describe each discourse below, elaborating on the conceptualisation of HTA, MedTech and evidence, the role of HTA agencies and their relation to other stakeholders. We highlight key journals and describe which countries or regions are discussed within the academic articles belonging to the discourse. Table 1 includes a key metaphor for each discourse. Notably, a large percentage of included articles are about NICE in the United Kingdom (UK) (50%). This is not surprising as NICE is a leading institution in HTA (Sculpher and Palmer, Reference Sculpher and Palmer2020) and articles were restricted to English. We reflect on this finding in our discussion.

Figure 1. Flowchart detailing the selection of articles.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 5 discourses about the role of European HTA agencies in governing medical technology

HTA: Health Technology Assessment, MedTech: Medical Technology, NICE MTEP: The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Medical Technologies Evaluation Programme (UK).

Figure 2. Count of articles per discourse over time.

3.1. Discourse 1: the HTA agency as an independent evaluator of all health technologies – sorting the wheat from the chaff

The first, most dominant discourse gives meaning to the role of the HTA agency as a systematic, independent evaluator (Specchia et al., Reference Specchia, Favale, Di Nardo, Rotundo, Favaretti, Ricciardi and de Waure2015; Ritrovato et al., Reference Ritrovato, Faggiano, Tedesco and Derrico2015; Rawlins, Reference Rawlins2000), that develops and publishes frameworks and guidelines (Gafni and Birch, Reference Gafni and Birch2003). This discourse emphasises technical expertise (Imaz-Iglesia and Wild, Reference Imaz-Iglesia and Wild2022; Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Ganz, Hsu, Strandberg-Larsen, Gonzalez and Lund2016) and scientific evidence, often called appropriate evidence (Ciani et al., Reference Ciani, Grigore and Taylor2022; Sculpher and Palmer, Reference Sculpher and Palmer2020), robust evidence (Quentin et al., Reference Quentin, Carbonneil, Moty-Monnereau, Berti, Goettsch and Lee-Robin2009; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Drummond, Taylor, McGuire, Carter and Mossialos2022), or proper evidence (Sculpher and Claxton, Reference Sculpher and Claxton2010), and contrasted to weak evidence (Ciani et al., Reference Ciani, Grigore and Taylor2022). As Table 1 shows, 36% of included articles were categorised into this discourse. Most articles were published in HTA and health economic journals, such as the International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care (IJTAHC) (37%), the Journal of Health Economics (9%), Pharmacoeconomics (9%), or Value in Health (7%). Most articles are about Europe (44%, either only discussing Europe or also referencing to institutions outside of Europe within the article) or about the UK, NICE specifically (40%) (see Supplementary Materials). This discourse started the earliest out of all discourses, with the first article we identified as fitting this discourse published in 1998.

HTA is defined as a systematic approach that is rigorous (Ritrovato et al., Reference Ritrovato, Faggiano, Tedesco and Derrico2015; Stevens and Milne, Reference Stevens and Milne2004) and transparent (Herrmann et al., Reference Herrmann, Wolff, Scheibler, Waffenschmidt, Hemkens, Sauerland and Antes2013; Hutton et al., Reference Hutton, Trueman and Facey2008), with the goal of efficient resource allocation (Birch and Gafni, Reference Birch and Gafni2002). It is often described in a stepwise manner, referring to routes (Stevens and Milne, Reference Stevens and Milne2004) and steps (Ciani et al., Reference Ciani, Grigore and Taylor2022), using specific tools (Neikter et al., Reference Neikter, Rehnqvist, Rosén and Dahlgren2009; Imaz-Iglesia and Wild, Reference Imaz-Iglesia and Wild2022). To continue systematically evaluating innovative technologies, HTA methods are seen as ever expanding, by adding new factors, e.g., environmental factors (Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Ganz, Hsu, Strandberg-Larsen, Gonzalez and Lund2016; Toolan et al., Reference Toolan, Walpole, Shah, Kenny, Jónsson, Crabb and Greaves2023), or developing new frameworks, e.g., for surrogate endpoints (Ciani et al., Reference Ciani, Grigore and Taylor2022), equity weighting (Paulden and McCabe, Reference Paulden and McCabe2021), or joint assessment (Lo Scalzo et al., Reference Lo Scalzo, Vicari, Corio, Perrini, Jefferson, Gillespie and Cerbo2015). It is assumed that HTA can be applied regardless of the type of health technology, as this discourse makes no or minimal distinction between different health technologies. Health technologies are often defined within brackets to include pharmaceuticals, devices, diagnostics, procedures, and other interventions. In case authors do give a specific example, these are almost always pharmaceuticals.

In terms of the relationships drawn with other stakeholders, this discourse focused most on HTA agencies alone. When other stakeholders are mentioned, the main ones mentioned are industry and other HTA agencies. Regarding the former, HTA agencies need to ensure that industry bias is removed in order to arrive at neutral evidence (Toolan et al., Reference Toolan, Walpole, Shah, Kenny, Jónsson, Crabb and Greaves2023; Birch and Gafni, Reference Birch and Gafni2002). Regarding the latter, this discourse is concerned with harmonisation among HTA agencies in Europe (Hutton et al., Reference Hutton, Trueman and Facey2008): Although different healthcare systems mean that the assessment of technologies may lead to different conclusions in different countries, the harmonisation and development of identical assessment methods on which decisions are based is seen as achievable, and part of the role of HTA agencies (Hutton et al., Reference Hutton, Trueman and Facey2008).

3.2. Discourse 2: the HTA agency as evidence stimulator – evidence as a thorny issue

The second discourse is similar to the first discourse in that the role of the HTA agency is seen as an evaluator of scientific evidence, however, this role is broadened to include a role for stimulating evidence generation’. This seems to be in relation to the fact that this discourse distinguishes more explicitly between pharmaceuticals and MedTech. It adheres to ideas about routes (Crispi et al., Reference Crispi, Naci, Barkauskaite, Osipenko and Mossialos2019; Willits et al., Reference Willits, Keltie, Craig and Sims2014) and robust evidence (Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Dillon, Collinson, Powell, Salmon, Oladapo, Ayiku, Shield, Holden, Patel, Campbell, Greaves, Joshi, Powell and Tonnel2021; Willits et al., Reference Willits, Cole, Jones, Carter, Arber, Jenks, Craig and Sims2017), but in applying them more exclusively to MedTech, the framing of the role shifts from a more distanced role of independently evaluating technologies to a more involved and proactive role of guiding industry, by encouraging adoption (Campbell and Campbell, Reference Campbell and Campbell2012; Crispi et al., Reference Crispi, Naci, Barkauskaite, Osipenko and Mossialos2019) or promoting uptake of HTA approaches (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Taylor and Girling2014; Campbell, Reference Campbell2011a), often by recommending further research (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Dobson, Higgins, Dillon, Marlow and Pomfrett2017; Blankart et al., Reference Blankart, Dams, Penton, Kaló, Zemplényi, Shatrov, Iskandar and Federici2021; Tarricone et al., Reference Tarricone, Ciani, Torbica, Brouwer, Chaloutsos, Drummond, Martelli, Persson, Leidl, Levin, Sampietro-Colom and Taylor2020). HTA agencies are seen as not only independently evaluating evidence, but as having a role in ensuring that the evidence is there to begin with. In more recent publications, the focus is on earlier involvement with industry, e.g., through early dialogues (Blankart et al., Reference Blankart, Dams, Penton, Kaló, Zemplényi, Shatrov, Iskandar and Federici2021; Hulstaert et al., Reference Hulstaert, Pouppez, Primus-de Jong, Harkin and Neyt2023), to ensure appropriate evidence further down the line. This was the second most dominant discourse, with 34% of included articles belonging to this discourse (Table 1). Most articles were published in more applied journals as well as HTA journals, including Applied Health Economics and Health Policy (35%), IJTAHC (18%), and Heart (8%). Most articles are about the UK (75%) (See Supplementary Materials), often about NICE’s ‘Medical Technologies Evaluation Programme’ (MTEP), which was launched in 2009.

Compared to discourse 1, many articles do not provide a definition of HTA, with one article instead referring to ‘medical technology assessment’ (Radhakrishnan et al., Reference Radhakrishnan, Peacock, Rua, Clough, Ofuya, Wang, Morris, Lewis and Keevil2014). MedTech is broadly defined, including medical devices, diagnostics, genetic tests, software, healthcare procedures, and health promotion activities. The focus of most articles is on ‘high-risk’ medical devices. The relation to pharmaceuticals is often explicitly mentioned, often MedTech are even defined as non-pharmaceuticals (Green and Hutton, Reference Green and Hutton2014; Varela-Lema et al., Reference Varela-Lema, Ruano-Ravina, Mota, Ibargoyen-Roteta, Gutiérrez-Ibarluzea, Blasco-Amaro, Soto-Pedre and Sampietro-Colom2012). Commonly, a list of differences is given between MedTech and pharmaceuticals, focusing on differences in evidence and including as reasons less stringent regulatory requirements and an iterative development of MedTech (Kovács et al., Reference Kovács, Kaló, Daubner-Bendes, Kolasa, Hren, Tesar, Reckers-Droog, Brouwer, Federici, Drummond and Zemplényi2022; Crispi et al., Reference Crispi, Naci, Barkauskaite, Osipenko and Mossialos2019; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Campbell, Dobson, Higgins, Dillon, Marlow and Pomfrett2018; Tarricone et al., Reference Tarricone, Ciani, Torbica, Brouwer, Chaloutsos, Drummond, Martelli, Persson, Leidl, Levin, Sampietro-Colom and Taylor2020). With regards to evidence, real-world data (RWD) also becomes important, as articles make the point that feasibility issues or problems with patient recruitment limit the availability of Randomized Controlled Trial (RCTs) for some MedTech (Leng and Partridge, Reference Leng and Partridge2018; Varela-Lema et al., Reference Varela-Lema, Ruano-Ravina, Mota, Ibargoyen-Roteta, Gutiérrez-Ibarluzea, Blasco-Amaro, Soto-Pedre and Sampietro-Colom2012; Srivastava et al., Reference Srivastava, Henschke, Virtanen, Lotman, Friebel, Ardito and Petracca2023).

In relation to other stakeholders, HTA agencies should influence industry and clinical experts to focus more on evidence generation and usage, respectively. Both stakeholders are sometimes portrayed as reluctant (Green and Hutton, Reference Green and Hutton2014; Campbell, Reference Campbell2011b). Because the HTA agency has limited mandate to impose on either, it should focus on encouragement. Regarding industry, HTA agencies need to encourage industry to conduct better studies (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Dobson, Higgins, Dillon, Marlow and Pomfrett2017). It is argued that device manufacturers are not accustomed to producing the type of evidence needed for HTA as they are inexperienced or lack resources (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Dobson, Higgins, Dillon, Marlow and Pomfrett2017; Campbell, Reference Campbell2013; Blankart et al., Reference Blankart, Dams, Penton, Kaló, Zemplényi, Shatrov, Iskandar and Federici2021). It is the role of HTA agencies to encourage MedTech industry to generate ‘better’ or ‘more mature’ evidence (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Dobson, Higgins, Dillon, Marlow and Pomfrett2017; Alshreef et al., Reference Alshreef, Jenks, Green and Dixon2016; Green and Hutton, Reference Green and Hutton2014; Campbell, Reference Campbell2013; Campbell and Knox, Reference Campbell and Knox2016). In addition, HTA agencies need regulators to set better evidence requirements for market entry (Green and Hutton, Reference Green and Hutton2014; Vinck et al., Reference Vinck, Neyt, Thiry, Louagie and Ramaekers2007; Tarricone et al., Reference Tarricone, Ciani, Torbica, Brouwer, Chaloutsos, Drummond, Martelli, Persson, Leidl, Levin, Sampietro-Colom and Taylor2020). Regarding clinicians, HTA agencies need to encourage clinicians to update their practice in response to new evidence (Campbell, Reference Campbell2011b).

3.3. Discourse 3: the HTA agency as convenor – Sandboxing, living labs, and testbeds

The third discourse gives meaning to the HTA agency as a process manager or convenor. The role of HTA agencies in relation to MedTech is to be a bridge between stakeholders (Andradas et al., Reference Andradas, Blasco, Valentín, López-Pedraza and Gracia2008) or a ‘boundary organization’ (Wehrens and de Graaff, Reference Wehrens and de Graaff2024). This discourse emerged around the same time as discourse 2 but is less dominant (Figure 2). Articles argue that HTA agencies need to broaden their scope to deal with technological developments. As HTA agencies do not have the resources to govern the vast number of MedTech alone, they increasingly need to collaborate with others. In doing so, they need to be pragmatic and balance different perspectives. In contrast to discourse 1 and 2, where robustness was highlighted, flexibility is emphasised (Dutot et al., Reference Dutot, Mercier, Borget, De Sauvebeuf and Martelli2017; Wehrens and de Graaff, Reference Wehrens and de Graaff2024). 16% of included articles represent this discourse (Table 1). Most articles were published in HTA and public health journals, such as the IJTAHC (45%), the Journal of comparative effectiveness research (10%), and the International Journal of environment research and public health (10%). Most articles are about Europe in general (78%), often mentioning the recent EU regulations (see Supplementary Materials). This discourse includes no articles about the UK.

MedTech are described either very broadly, e.g., ‘tests, devices, vaccines, procedures, programs, or systems’ (Greenwood Dufour et al., Reference Greenwood Dufour, Weeks, De Angelis, Marchand, Kaunelis, Severn, Walter and Mittmann2022) or more specifically, e.g., digital health (Oortwijn et al., Reference Oortwijn, Sampietro-Colom, Habens and Trowman2018; Facey et al. Reference Facey, Rannanheimo, Batchelor, Borchardt and De Cock2020) or diagnostic technologies (Cacciatore et al., Reference Cacciatore, Specchia, Solinas, Ricciardi and Damiani2020). They are not described as non-pharmaceuticals, as was more common in discourse 2. When HTA is defined, articles often refer to the broader, updated definition of HTA (O’Rourke et al., Reference O’Rourke, Oortwijn and Schuller2020). Reference to the multidisciplinary nature of HTA is also already made before this updated definition (Dutot et al., Reference Dutot, Mercier, Borget, De Sauvebeuf and Martelli2017). Evidence is understood in a broad sense, including social, ethical, and legal factors next to clinical and economic ones, and warrants interpretation (Oortwijn, Husereau, Abelson, Barasa, Bayani, Canuto Santos, et al., Reference Oortwijn, Husereau, Abelson, Barasa, Bayani, Canuto Santos, Culyer, Facey, Grainger, Kieslich, Ollendorf, Pichon-Riviere, Sandman, Strammiello and Teerawattananon2022; Oortwijn, Husereau, Abelson, Barasa, Bayani, Santos, et al., Reference Oortwijn, Husereau, Abelson, Barasa, Bayani, Santos, Culyer, Facey, Grainger, Kieslich, Ollendorf, Pichon-Riviere, Sandman, Strammiello and Teerawattananon2022; Greenwood Dufour et al., Reference Greenwood Dufour, Weeks, De Angelis, Marchand, Kaunelis, Severn, Walter and Mittmann2022; Bloemen and Oortwijn, Reference Bloemen and Oortwijn2024). It is frequently referred to as ‘best available evidence’ (Furman et al., Reference Furman, Gałązka-Sobotka, Marciniak and Kowalska-Bobko2022). Whereas in discourse 2, the lack of evidence for MedTech is something HTA agencies must actively improve, in this discourse it seems to be interpreted more as a given. To deal with this lack of evidence, participatory (Oortwijn, Husereau, Abelson, Barasa, Bayani, Canuto Santos, et al., Reference Oortwijn, Husereau, Abelson, Barasa, Bayani, Canuto Santos, Culyer, Facey, Grainger, Kieslich, Ollendorf, Pichon-Riviere, Sandman, Strammiello and Teerawattananon2022; Oortwijn, Husereau, Abelson, Barasa, Bayani, Santos, et al., Reference Oortwijn, Husereau, Abelson, Barasa, Bayani, Santos, Culyer, Facey, Grainger, Kieslich, Ollendorf, Pichon-Riviere, Sandman, Strammiello and Teerawattananon2022), exploratory (Greenwood Dufour et al., Reference Greenwood Dufour, Weeks, De Angelis, Marchand, Kaunelis, Severn, Walter and Mittmann2022; Leckenby et al., Reference Leckenby, Dawoud, Bouvy and Jónsson2021; Tummers et al., Reference Tummers, Kværner, Sampietro-Colom, Siebert, Krahn, Melien, Hamerlijnck, Abrishami and Grutters2020) and pragmatic (Rochaix and Xerri, Reference Rochaix and Xerri2009) approaches to MedTech governance are preferred, including sandboxes, living labs and testbeds. At the same time, it is questioned whether the historical commitment to neutral evidence may conflict with these new approaches for MedTech (Bloemen and Oortwijn, Reference Bloemen and Oortwijn2024).

Emphasis is placed on collaborations, including between international HTA agencies (Simpson and Ramagopalan, Reference Simpson and Ramagopalan2022), between local and national HTA agencies (Dutot et al., Reference Dutot, Mercier, Borget, De Sauvebeuf and Martelli2017), between HTA agencies and industry (Leader, Reference Leader2008), and between all relevant stakeholders (Facey et al., Reference Facey, Rannanheimo, Batchelor, Borchardt and De Cock2020, Oortwijn et al., Reference Oortwijn, Sampietro-Colom, Habens and Trowman2018). This discourse mentions the widest variety of stakeholders, including clinicians, hospitals, industry, regulators, patients, policy-makers, and citizens. The assessment should be developed in consultation with these stakeholders, to increase transparency, deliberate on RWD, and address context dependence and user experience (Bloemen and Oortwijn, Reference Bloemen and Oortwijn2024; Rochaix and Xerri, Reference Rochaix and Xerri2009, Facey et al., Reference Facey, Rannanheimo, Batchelor, Borchardt and De Cock2020). Similarly to discourse 2, there seems to be a focus on earlier involvement, e.g., early HTA as a joint effort between different stakeholders to inform investment decisions (Tummers et al., Reference Tummers, Kværner, Sampietro-Colom, Siebert, Krahn, Melien, Hamerlijnck, Abrishami and Grutters2020; Leckenby et al., Reference Leckenby, Dawoud, Bouvy and Jónsson2021). The epistemological problems that such (early) involvement may introduce are emphasised and reflected on (Leckenby et al., Reference Leckenby, Dawoud, Bouvy and Jónsson2021; Wehrens and de Graaff, Reference Wehrens and de Graaff2024; Oortwijn et al., Reference Oortwijn, Sampietro-Colom, Habens and Trowman2018; Oortwijn, Husereau, Abelson, Barasa, Bayani, Canuto Santos, et al., Reference Oortwijn, Husereau, Abelson, Barasa, Bayani, Canuto Santos, Culyer, Facey, Grainger, Kieslich, Ollendorf, Pichon-Riviere, Sandman, Strammiello and Teerawattananon2022; Tummers et al., Reference Tummers, Kværner, Sampietro-Colom, Siebert, Krahn, Melien, Hamerlijnck, Abrishami and Grutters2020; Bloemen and Oortwijn, Reference Bloemen and Oortwijn2024).

3.4. Discourse 4: critical reflection on the level of normative reflection of HTA agencies – the technocratic hope of a value-free arm’s length agency

In the fourth discourse, the level of reflection on normative aspects of the role of the HTA agency is critically questioned. For example, it is argued that the language of evidence may obscure underlying political disputes, ‘pushing issues of income, policy, and turf below the surface’ (Syrett, Reference Syrett2003). Lack of transparency about such issues may affect the legitimacy of HTA agencies (Syrett, Reference Syrett2003). Articles argue that while some legitimacy issues may be repaired through increased participation from clinicians, patients, or the public, this also introduces new legitimacy problems (Burls et al., Reference Burls, Caron, Cleret De Langavant, Dondorp, Harstall, Pathak-Sen and Hofmann2011). 6% of included articles belonged to this discourse (Table 1). Articles are distributed across journals like Health Policy, Health Economics, and Health Ethics, as well as several clinical journals. About half of articles are about the UK (57%) and half about Europe (43%).

MedTech are defined very broadly, with articles mentioning examples of MedTech, pharmaceuticals, and health care systems. In other towards, this discourse of critical reflection on the role of HTA agencies and their level of normative reflection includes yet extends beyond MedTech. HTA is described as necessarily value-laden, with ethical issues arising when deciding on which technologies to prioritise, which methods to use, how issues are framed, and which stakeholders’ values are considered (Burls et al., Reference Burls, Caron, Cleret De Langavant, Dondorp, Harstall, Pathak-Sen and Hofmann2011). One article mentions how many factors impact decision making, e.g., ‘uncertainty, budget impact, clinical need, innovation, rarity, age, cause of disease, wider societal impacts, stakeholder influence and process factors’, and that the interaction of these factors should be better understood (Charlton, Reference Charlton2022). Other articles explore whether HTA agencies are gender – (Panteli et al., Reference Panteli, Zentner, Storz-Pfennig and Busse2011) or age sensitive (Douglas, Reference Douglas2012). Lastly, this discourse reflects on the distinction between a value-free assessment phase and a value-laden appraisal phase, arguing that while this may be helpful for defining roles, it should not exclude explicit value considerations in the assessment phase (Burls et al., Reference Burls, Caron, Cleret De Langavant, Dondorp, Harstall, Pathak-Sen and Hofmann2011).

3.5. Discourse 5: critical reflection on the level of nuanced clinical expertise of HTA agencies – overriding clinical responsibility

The last discourse critically reflects on the role of the HTA agency in terms of their level of nuanced, clinical expertise. The HTA agency is said to not always understand how a lack of nuance, clinical expertise impacts patients and their families (Gala et al., Reference Gala, Pope, Leo, Lobban and Betts2022). Articles argue that HTA agencies can only provide guidance to clinicians regarding MedTech, and their responsibility to be transparent and avoid data redaction in published guidance is emphasised (Osipenko, Reference Osipenko2021). 7% of included articles belonged to this discourse (Table 1). Most articles were published in clinical journals, such as BMJ (or BMJ open) (50%) or Heart (20%). All articles in this discourse were about the UK, with criticism often directed at NICE’s role in developing guidelines.

A description of HTA is often not given, except in one article where it is explicitly placed in the order of ‘hurdles’, i.e., after demonstration that a technology is ‘pure, efficacious, and safe’ it also needs to be ‘better in some way than what is currently available’ (Smith, Reference Smith1999). This discourse urges the HTA agency to closely collaborate with clinicians (Leng and Partridge, Reference Leng and Partridge2018; Vyawahare et al., Reference Vyawahare, Hallas, Brookes, Taylor and Eldabe2014; Chisholm, Reference Chisholm2014). This discourse differentiates explicitly between different technologies and includes the most references to specific MedTech, describing their unique clinical contextual relevance. It argues that HTA would be more fitting if it were either done for all technologies, or for none at all. Because HTA agencies currently often focus on certain types of technologies, it is considered difficult for clinicians to weigh decisions about treatments, beds, nurses, diagnostic equipment, etc. (Smith, Reference Smith1999) Regarding evidence, it is argued that research literature often does not represent real-life practice, with clinicians sometimes needing to include other factors, including peer support (Chisholm, Reference Chisholm2014) and patient needs (Gala et al., Reference Gala, Pope, Leo, Lobban and Betts2022).

4. Discussion

Based on a comprehensive literature review and discourse analysis, we constructed 5 discourses. Each discourse frames HTA, MedTech, and evidence in a different way and presents a different story of the role of HTA agencies in the governance of MedTech. The first discourse describes the HTA agency as an independent evaluator of appropriate evidence for all health technologies. The second discourse explicitly distinguishes MedTech as separate from pharmaceuticals and expands the role to include stimulating evidence generation for MedTech. The third discourse describes the HTA agency as a convenor of stakeholder perspectives, emphasising flexibility and experimental approaches. The fourth discourse critically reflects on the level of normative reflection and how lack of reflection could undermine the legitimacy of HTA agencies. The fifth discourse critically reflects on the level of nuanced, clinical expertise of HTA agencies and urges more collaboration more closely with clinicians.

Most importantly, our study explores how the role of HTA agencies in relation to MedTech is interpreted differently across the academic literature. This is important to keep in mind in light of institutional developments at the EU level. In addition to the procedural and legal discussions surrounding the introduction of regulations such as the HTAR, it is equally important for policymakers to reflect on the broader, more ideological questions of what these developments mean – or should mean – for the role of HTA agencies in MedTech. It appears that, at least in the academic literature, discourses on this role differ in terms of their degree of distance from and dependence on other stakeholders. Further reflection on the position of HTA agencies in relation to other stakeholders in MedTech governance is therefore warranted. To the best of our knowledge such a review has not been done before.

Furthermore, all discourses refer to some extent to how a lack of evidence for innovative MedTech complicates the role of HTA agencies. We particularly wish to underline a normative friction between the scarcity of evidence and the traditionally dominant discourse of the HTA agency as an independent evaluator of appropriate evidence. In the scarcity of evidence surround MedTech, the normative complexity of what HTA agencies should and should not do seems to be increasing (Bloemen et al., Reference Bloemen, Oortwijn and van der Wilt2024). With the JCA of certain high-risk medical devices from 2030 onwards, this normative complexity of the work of HTA agencies regarding MedTech may further amplify, bringing these discussions ‘above the surface’ (Syrett, Reference Syrett2003). We therefore recommend further reflection on this matter by policy-makers and believe the identified discourses can be of use in such discussions. The goal here would not be to categorise HTA agencies into a specific discourse, as the discourses are ideal-typical and multiple discourses can co-exist within an institution. However, reflection on where the HTA agency stands, or wishes to stand, in terms of its role in MedTech governance and what different ways of framing MedTech and evidence do for this role, can be elusive in further developing the MedTech policy framework.

In particular, two opposing framings around this lack of evidence for MedTech appear from our analysis. Discourse 2 focuses on the role of HTA agencies in prompting better evidence generation for MedTech. This discourse has become increasingly dominant over the last 15 years. Discourse 3 has intensified more recently, starting around 2020, and reflects a more facilitative and experimental role to MedTech governance. In addition, both discourses 2 and 3 discuss earlier involvement by HTA agencies. However, in discourse 2, the aim of such early engagement is mainly to ‘set the right incentives for manufacturers to initiate change’ (Blankart et al., Reference Blankart, Dams, Penton, Kaló, Zemplényi, Shatrov, Iskandar and Federici2021), and in discourse 3, such early engagement is discussed in terms of the ‘the aim of mutual learning and adaptation’ (Leckenby et al., Reference Leckenby, Dawoud, Bouvy and Jónsson2021). Whereas in Discourse 2, the lack of evidence for MedTech seems to be described as something that HTA agencies must actively change, in Discourse 3 it seems to be interpreted as more of a given for MedTech, and HTA agencies must work around this lack of evidence by engaging in flexible, experimental approaches.

Building on the findings of this study, we recommend several directions for future research. In general, we recommend research on how the role of HTA agencies in MedTech governance plays out in practice, to understand what the identified conflicting discourses mean for the day-to-day level of MedTech policymaking. It would be interesting to see whether, in practice, HTA agencies do indeed take the more dominant, independent approach to MedTech governance, or whether they adopt more instigative or more participatory approaches, and what this means for the other stakeholders involved. It is likely that strategies for MedTech governance will require different approaches for different circumstances, but as our review and in particular Discourse 4 highlights, a lack of reflection on the normative aspects of different roles can undermine the legitimacy of HTA agencies (Burls et al., Reference Burls, Caron, Cleret De Langavant, Dondorp, Harstall, Pathak-Sen and Hofmann2011; Syrett, Reference Syrett2003). In particular, in light of the opposing framings of the role of HTA agencies in relation to a lack of evidence for MedTech, we believe it would be interesting to follow how this discrepancy plays out in practice, as it would be interesting to see how HTA agencies navigate more acute issues of scarcity of MedTech evidence. In general, we note that the more critical Discourses 4 and 5 were relatively underrepresented in the literature. This suggests a need for more explicit and sustained reflection in future research on the normative foundations of HTA’s role in MedTech governance.

Finally, we would like to reflect on the strengths and limitations of our study. By combining a systematic search with a discourse-analytic approach, we provided a comprehensive overview of how the role of HTA agencies in relation to MedTech is interpreted across the academic literature. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review specifically addressing how this role is framed differently across scholarly discourse. Such a review is a critical step towards enhancing our understanding of the governance of MedTech. However, our reliance on academic literature introduces certain limitations. For instance, our review may reflect a skewed perspective, as scholars from some countries, such as the UK, publish more extensively on this topic than others. This is evident in the overrepresentation of NICE in our analysis, which can be attributed to their frequent publication of processes in the academic domain and their explicit MedTech Evaluation Programme (MTEP). Nonetheless, given NICE’s prominent international profile (Sculpher and Palmer, Reference Sculpher and Palmer2020), their significant representation in our review is both expected and reflective of their leadership in the field. Additionally, because specific language is an integral part of discourse analysis, we restricted our review to English-language publications to avoid having to translate texts and potentially miss metaphors or nuances. This decision, while pragmatic, further limits the scope of our analysis, potentially excluding discourses from non-English-speaking countries. A further limitation of this study concerns the challenge of fully distinguishing framings of HTA in relation to MedTech from those concerning pharmaceuticals. As mentioned, several of the included articles addressed both types of technologies. Although the way authors differentiated between the two types of technologies was assessed as an important part of categorisation into a discourse, it nevertheless remains difficult to completely disentangle MedTech-specific framings from the wider HTA discourse shaped by pharmaceutical contexts, especially as assessment practices and regulatory decisions in relation to MedTech seem influenced by the discourse surrounding pharmaceuticals. A final limitation concerns the interpretation of discourse prevalence. While the number of publications associated with each discourse reflects their relative presence in the literature, this measure cannot be directly equated with influence or significance, which depend on a range of other factors. Future research could further explore the relative prominence or policy impact of these discourses through alternative forms of analysis. These limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings.

5. Conclusion

Overall, our results provide an interpretive framework on how the role of HTA agencies in relation to MedTech is interpreted differently across the academic literature and over time. Although the newly updated definition of HTA foregrounds its multidisciplinary nature, and new European regulations increase the role of HTA agencies in relation to the governance of MedTech, our study signifies that there are discrepancies in the interpretation of this role in the academic literature. Some of the constructed discourses are more dominant in earlier years, while others appear to be emerging or gaining prominence more recently. Importantly, our study does not make claims about the current prevalence of each discourse at a specific time point. To evaluate that, additional empirical work (e.g., using grey literature, policy documents, or interviews) would be needed. We do highlight in particular how all discourses seem to refer to some extent to how a lack of evidence for innovative MedTech complicates the role of HTA agencies, and two opposing framings around this lack of evidence for MedTech appear from our analysis. Based on our more explorative findings, we recommend that more empirical research be conducted on how different framings of the role play out in practice, and what this means for the governance of MedTech by HTA agencies. The way in which the role of HTA agencies in relation to MedTech is framed in the academic literature can influence governance by shaping perceptions, legitimising decisions, and guiding action (Blume, Reference Blume2009; Ciani et al., Reference Ciani, Armeni, Boscolo, Cavazza, Jommi and Tarricone2016; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Selin and Scott2021; Burau et al., Reference Burau, Nissen, Terkildsen and Vaeggemose2021). Understanding and reflecting on the different academic discourses is therefore crucial, for furthering the academic debate, increasing our understanding and advancing MedTech governance.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744133125100339.

Competing interests

None.

Funding Statement

Open access funding provided by Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Dutch National Health Care Institute in the context of the Research Network HTA. The execution and publication of the study results is not contingent on the sponsor’s approval or censorship in any way. Researcher independence is guaranteed in a written legal partnership agreement between the Institute and our research faculty.