Impact statement

This study documents a rare and consequential sediment transport event following a sequence of climate-related disturbances on the Great Barrier Reef. In the early months (Austral summer) of 2024, the reef experienced the ninth global bleaching event, with catastrophic impacts at One Tree Reef, a site of long-standing significance in Geoscience. One year later, in March 2025, Tropical Cyclone Alfred remobilised the resulting rubble and transported it onto the reef flat. While grooves (the channels of spur and groove systems) have long been suspected to play a role in sediment dynamics, the prevailing view has been that it is “impossible” for rubble to move upslope through them to the reef flat. Our study shows the first evidence that large volumes of coral rubble are delivered to the reef flat through these grooves. We present qualitative and quantitative drone surveys and field measurements of topography and bathymetry to document this process. These findings carry implications for sediment budgets, interpretations of past reef-building processes and forecasts of reef and shingle island evolution under climate change. These insights are especially timely given their relevance to increasingly used restoration strategies (e.g., rubble stabilisation) and to global sustainability efforts, particularly United Nations Sustainable Development Goals related to Small Island Developing States, such as SDG13 (Climate action), SDG14 (Life below water) and SDG 11 (Sustainable cities and communities). These insights are important given the relevance to millions of people globally whose livelihoods are inextricably linked to coral reef ecosystems.

Introduction

Coral reef islands are dynamic environments that, by adjusting to the environmental conditions (Masselink et al., Reference Masselink, Beetham and Kench2020), remain among the most climate-vulnerable ecosystems on Earth. Physical modelling of gravel islands has demonstrated that islands could build up and adapt to sea level rise (Tuck et al., Reference Tuck, Kench, Ford and Masselink2019; Masselink et al., Reference Masselink, Beetham and Kench2020). However, the pathways and rates of sediment supply, without which build-up cannot happen, are event-driven and remain poorly constrained (de Bakker et al., Reference de Bakker, Perry and Webb2025). Islands composed of biogenic carbonate materials are built from sediments derived from the surrounding forereefs and reef flats. Consequently, the sediment supply is threatened by climate change disruptions such as increased marine heatwaves and intense tropical cyclones, which reduce overall reef productivity (de Bakker et al., Reference de Bakker, Perry and Webb2025). Here, we present new evidence of the pathways of sediment delivery from a bleached coral reef during a tropical storm.

Spurs and grooves (SAGs) act as living breakwaters (Munk and Sargent, Reference Munk and Sargent1948) on the forereef of coral reefs. Spurs are parallel ridges of living carbonate material (coral and algae) separated by regularly spaced channels (grooves) (Duce et al., Reference Duce, Vila-Concejo, Hamylton, Webster, Bruce and Beaman2016). SAGs are usually oriented perpendicular to the reef crest and/or the incoming waves. They form a “comb-tooth” pattern (6–8 m wide) extending from the reef crest to depths of 20 m (Gischler, Reference Gischler2010). SAGs show considerable variations in morphology predominantly driven by the prevailing hydrodynamic energy (Duce et al., Reference Duce, Dechnik, Webster, Hua, Sadler, Webb, Nothdurft, Salas-Saavedra and Vila-Concejo2020). SAG morphology has been documented across different reef morphologies, including fringing reefs, barrier reefs and atolls through coral-rich seas (Duce et al., Reference Duce, Vila-Concejo, Hamylton, Webster, Bruce and Beaman2016). While they have been studied since the mid twentieth century (Munk and Sargent, Reference Munk and Sargent1948), recent years have seen an increased focus on SAG research, including remote sensing (Duce et al., Reference Duce, Vila-Concejo, Hamylton, Webster, Bruce and Beaman2016), numerical modelling (Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Monismith, Feddersen and Storlazzi2013; da Silva et al., Reference da Silva, Storlazzi, Rogers, Reyns and McCall2020; Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, Kan, Toguchi, Nakashima, Roeber and Arikawa2023; Perris et al., Reference Perris, Salles, Fellowes, Duce, Webster and Vila-Concejo2024) and field measurements (Storlazzi et al., Reference Storlazzi, Ogston, Bothner, Field and Presto2004; Monismith et al., Reference Monismith, Herdman, Ahmerkamp and Hench2013; Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Monismith, Dunbar and Koweek2015; Duce et al., Reference Duce, Dechnik, Webster, Hua, Sadler, Webb, Nothdurft, Salas-Saavedra and Vila-Concejo2020, Reference Duce, Vila-Concejo, McCarroll, Yiu, Perris and Webster2022; Acevedo-Ramirez et al., Reference Acevedo-Ramirez, Stephenson, Wakes and Mariño-Tapia2021; Sartori et al., Reference Sartori, Boles, Monismith, Mumby, Dunbar, Khrizman, Tatebe and Capozzi2025). These studies have confirmed that SAG morphology and hydrodynamics are linked to wave climate, from incident short waves to infragravity. They are important wave dissipaters protecting the areas behind reefs (Monismith et al., Reference Monismith, Herdman, Ahmerkamp and Hench2013; Duce et al., Reference Duce, Vila-Concejo, McCarroll, Yiu, Perris and Webster2022; Watanabe et al., Reference Watanabe, Kan, Toguchi, Nakashima, Roeber and Arikawa2023; Perris et al., Reference Perris, Salles, Fellowes, Duce, Webster and Vila-Concejo2024).

SAGs exist under a broad range of wave energy settings and associated water flows (Duce et al., Reference Duce, Vila-Concejo, Hamylton, Webster, Bruce and Beaman2016, Reference Duce, Dechnik, Webster, Hua, Sadler, Webb, Nothdurft, Salas-Saavedra and Vila-Concejo2020). It is mostly through modelling that water flows in the SAG zone have been investigated, with research indicating the existence of counter-rotating Lagrangian circulation cells in the grooves (Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Monismith, Feddersen and Storlazzi2013; da Silva et al., Reference da Silva, Storlazzi, Rogers, Reyns and McCall2020). However, it is unclear whether the flows that occur in the grooves drive sediment transport onshore (towards the reef flat) or offshore. While numerical modelling studies (Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Monismith, Feddersen and Storlazzi2013) mostly found gentle offshore flow over the shallow part of the grooves, others (da Silva et al., Reference da Silva, Storlazzi, Rogers, Reyns and McCall2020) showed a gentle onshore current in most of their simulations. More recently, field measurements have shown offshore flow in shallow grooves under low wave energy conditions (Perris et al., Reference Perris, Lindhart, Salles, da Silva, Fellowes and Vila-Concejo2025; Sartori et al., Reference Sartori, Boles, Monismith, Mumby, Dunbar, Khrizman, Tatebe and Capozzi2025). While Rogers (Reference Rogers, Monismith, Feddersen and Storlazzi2013) posits that under strong wave forcing, the offshore transport on the grooves would be reduced or potentially reversed, such conditions have never been measured or observed. A study using tracers of the effects of Category 4 Typhoon Robyn in 1993 in Kume Island (Ryukyus, Southern Japan) showed that coral clasts could be transported from the forereef (up to 12 m depth) onto the reef flat, but those clasts were not located on the grooves (Kan, Reference Kan and Bellwood1995). Other indications of onshore transport result from personal observations by the authors of the current manuscript of onshore imbrication of coral clasts witnessed while deploying instruments in the Maldives and the Great Barrier Reef.

One Tree Reef (OTR) is a wave-exposed mesotidal platform reef located on the southern Great Barrier Reef (GBR, Figure 1). Its eastern margin comprises a rubble-dominated reef flat containing an estimated 14 million tons of rubble derived from the reef front (Thornborough and Davies, Reference Thornborough, Davies and Hopley2011). It is one of the few reefs in the GBR containing a shingle island on its exposed margin. Coral rubble is the generic term used to denote sediments resulting from the fragmentation of calcifying organisms, including coral and molluscs. It refers to sediment larger than sand (>2 mm) and typically up to boulder size in the Udden-Wentworth scale (>256 mm), with a variety of morphologies ranging from branching to tabular (Rasser and Riegl, Reference Rasser and Riegl2002). The coral rubble is dumped on the reef flat during a large, high-energy event and is then reworked (Thornborough and Davies, Reference Thornborough, Davies and Hopley2011) with some of it forming rubble spits or tracts (Shannon et al., Reference Shannon, Power, Webster and Vila-Concejo2013) that deliver rubble to the shingle island (Talavera et al., Reference Talavera, Vila-Concejo, Webster, Smith, Duce, Fellowes, Salles, Harris, Hill, Figueira and Hacker2021). The SAGs on the eastern forereef of OTR (Figure 2) have spurs with ~90% coral cover and grooves with a “U”-shaped cross-section, and at the base have a variable amount of large rubble clasts with occasional pockets of coarse sand (Duce et al., Reference Duce, Vila-Concejo, Hamylton, Webster, Bruce and Beaman2016). Rubble environments are ubiquitous in coral reefs (Blanchon et al., Reference Blanchon, Jones and Kalbfleisch1997; Thornborough and Davies, Reference Thornborough, Davies and Hopley2011), and previous ecosystem restoration studies have highlighted that rubble mobility hinders coral growth (Ceccarelli et al., Reference Ceccarelli, McLeod, Boström-Einarsson, Bryan, Chartrand, Emslie, Gibbs, Rivero, Hein, Heyward, Kenyon, Lewis, Mattocks, Newlands, Schläppy, Suggett and Bay2020). On the other hand, recent studies suggest that rubble fields are important ecosystems that serve as potential targets for coral settlement (Heyward et al., Reference Heyward, Giuliano, Page and Randall2024).

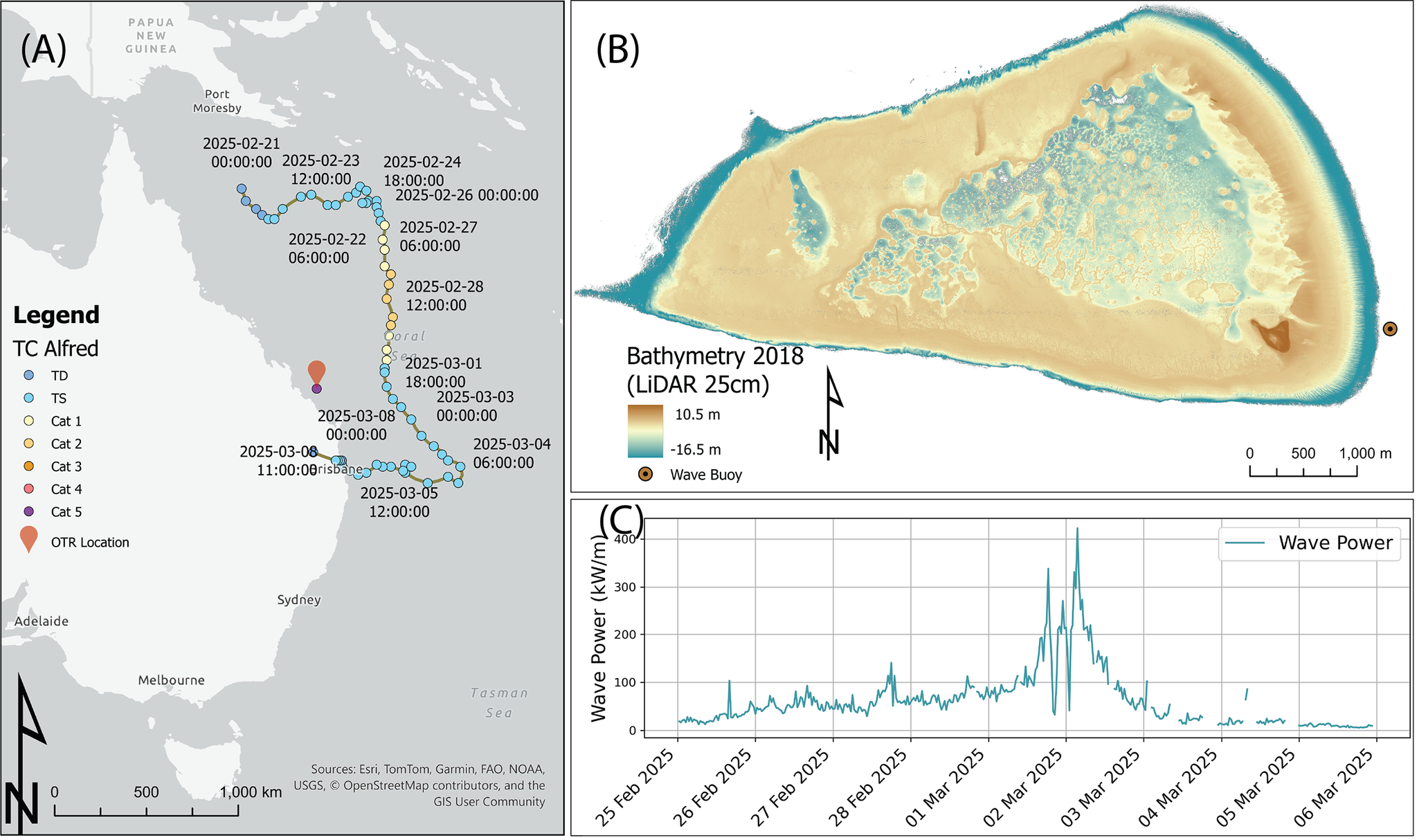

Figure 1. (A) Location of One Tree Island on the southern Great Barrier Reef off the coast of NE Australia and track and Saffir-Simpson category for Tropical Cyclone Alfred in March 2025, note in the legend, TD= Tropical Depression and TS= Tropical Storm (Source IBTrACS (Knapp et al. Reference Knapp, Kruk, Levinson, Diamond and Neumann2010)); (B) LiDAR Digital Elevation Model (Vertical datum is mean sea level, MSL) with 25 cm resolution of One Tree Reef (OTR) measured in 2018 (Harris et al. Reference Harris, Webster, Vila-Concejo, Duce, Leon and Hacker2023) showing the location of the Spotter wave buoy; (C) Wave power from the southern One Tree Island Research Station (OTIRS) wave buoy on the east flank of One Tree Reef (see B for location) during TC Alfred.

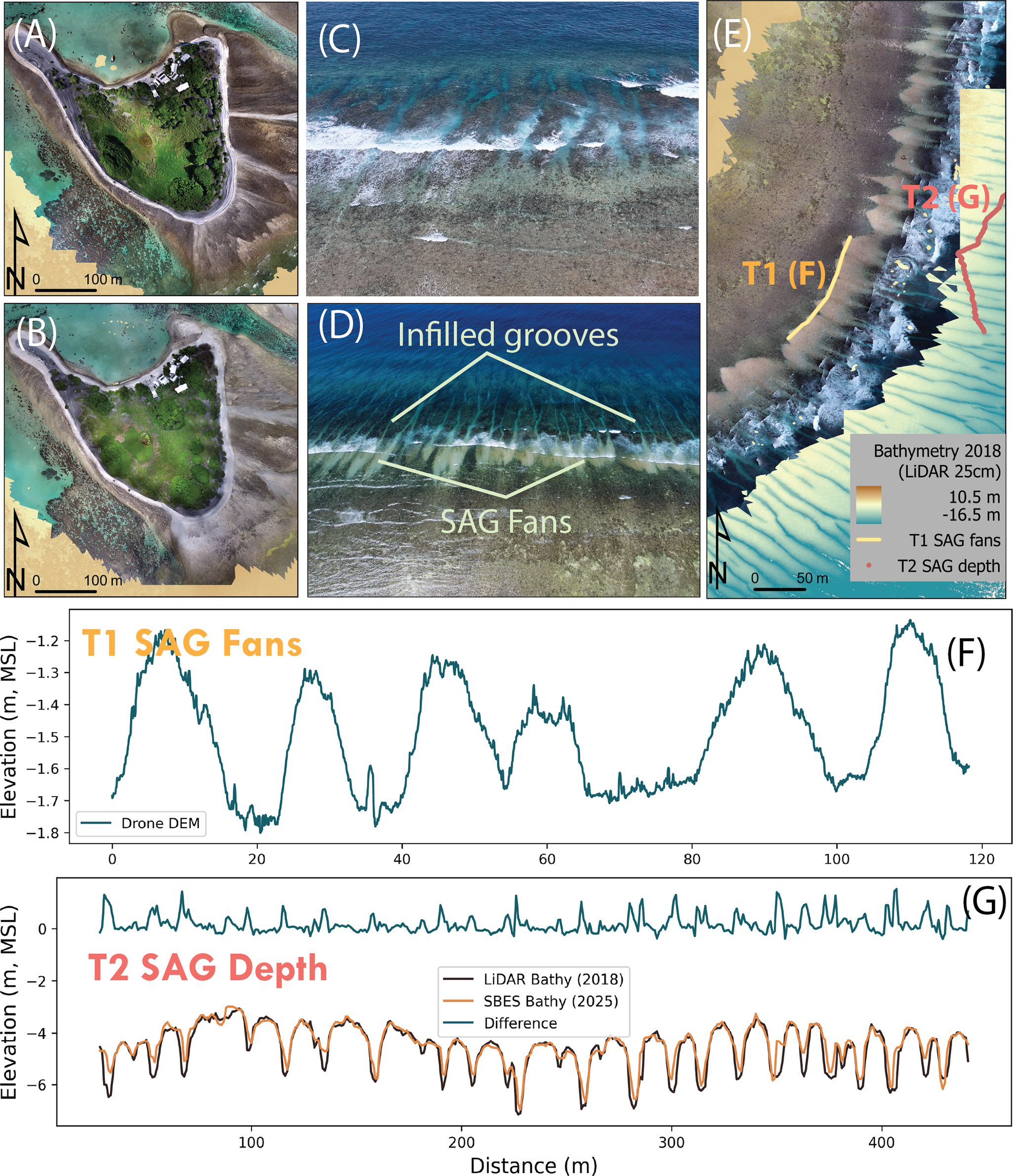

Figure 2. Orthomosaics of One Tree Island with adjacent rubble reef flat in November 2022 (A) and post TC Alfred in March 2025 (B); the grooves off the SE of One Tree Reef are clear of sediment in November 2024 (photo by Lachlan Perris, C) and infilled with coral rubble fans spilling sediment as SAG Fans onto the reef flat post TC Alfred in March 2025 (photo by One Tree Island Research Station, OTIRS, D); Orthomosaic of the SAG at One Tree Reef post TC Alfred (March 2025), showing the sediment fans delivered through the groove channels, and the locations of T1 and T2, the SAG bathymetry corresponds to data obtained with LiDAR in 2018(E); T1 shows a cross-section of the edges of the rubble fans extracted from the drone data (F); and, T2 demonstrates infilling of the grooves by comparing a LiDAR bathymetry from 2018 with a single beam bathymetry (T2) measured in 2025 post TC Alfred (G).

In February–March 2024, OTR underwent the worst bleaching in its history, causing up to 53% coral mortality (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Waller, Clements, Kelly, Kingsford, Liu, Reymond, Vila-Concejo, Webb, Whitton and Foo2025), more acute in areas of low hydrodynamic energy (Meoded-Stern et al., Reference Meoded-Stern, Silva, Foo, Waller, Byrne and Vila-Concejo2025). This event generated large amounts of coral rubble resulting from the dead coral collapse. One year after the bleaching, on 1 March 2025, Tropical Cyclone (TC) Alfred passed 340 km east of One Tree Island (Figure 1A). It was a slow-moving Category 1–2 cyclone (Saffir-Simpson Scale) that downgraded to Tropical Storm later that day, still sustaining strong winds. Our wave Spotter Buoy located on the SE off the reef (Figure 1B) recorded Significant Wave Heights (H s) up to 7 m with associated Peak Periods (T p) of 12 s. This led to wave power exceeding 250 kW/m sustained over nearly 12 h (Figure 1C). Fortunately, for One Tree Island Research Station, the largest waves occurred during the astronomical low tides.

As expected, TC Alfred delivered large volumes of rubble to the reef flat, modifying the overall morphology of the island (Figure 2A,B; see white rubble in 2B over the reef flat and on the northern tip). The mechanisms acting during these event-driven stochastic occurrences are not well established/studied, and scientists have debated for years whether SAGs could act as channels to deliver sediments to the reef flat under high-energy conditions. In March 2025, immediately after the passage of TC Alfred, we captured a photo showing grooves that are normally relatively empty of sediment (Figure 2C) were completely infilled with sediment and had newly formed sedimentary fans of rubble extending out from each groove on the eastern margin of OTR (Figure 2D). This is the first evidence showing the grooves acting as channels for rubble delivery onto the reef flat from decades of SAG research worldwide. Measurements from drone surveys post-Alfred show the distinct one-to-one spatial alignment between the rubble fans and the grooves, with each groove producing a single fan (Figure 2E). Bathymetric measurements show over 1 m of rubble infilling on the previously mostly bare grooves (Figure 2F).

Our observations and measurements establish, for the first time, grooves as channels transporting coral rubble onto the reef flat during high-energy conditions. This contrasts with the commonly accepted paradigm that rubble on the reef flats is transported from the spurs during high-energy conditions, and that rubble in the grooves remains trapped there or, under the right conditions, moves down the groove (Kan et al., Reference Kan, Hori, Kawana, Kaigara and Ichikawa1997; Hubbard and Dullo, Reference Hubbard, Dullo, Hubbard, Rogers, Lipps and Stanley2016; Duce et al., Reference Duce, Dechnik, Webster, Hua, Sadler, Webb, Nothdurft, Salas-Saavedra and Vila-Concejo2020; Sartori et al., Reference Sartori, Boles, Monismith, Mumby, Dunbar, Khrizman, Tatebe and Capozzi2025). The observed groove onshore transport occurred during extreme high-energy conditions, with TC Alfred being in the top 99th percentile of TC-generated waves for the study area. The threshold at which this onshore transport initiates is likely location dependent and deserves further investigation, as onshore rubble transport is crucial for the persistence of rubble islands, and TCs are expected to become more intense and less frequent in the Southern Hemisphere (Knutson et al., Reference Knutson, Camargo, Chan, Emanuel, Ho, Kossin, Mohapatra, Satoh, Sugi, Walsh and Wu2020). Finally, our observations highlight that the function of SAGs is not limited to the dissipation of wave energy but enables onshore rubble transport and contributes to coral environment dynamics essential for reef ecosystem health. While we have shown that rubble delivery plays an important role in the island stability of shingle islands, it has also been shown to influence sandy islands such as the Maldives (Gea-Neuhaus et al., Reference Gea-Neuhaus, Scott, Masselink, Lindhart, Vila-Concejo and Kench2025). Reef building is more than coral growth; it is a complex interplay of carbonate production, destruction and transport, as well as the reincorporation of sediment into the reef framework (Hubbard and Dullo, Reference Hubbard, Dullo, Hubbard, Rogers, Lipps and Stanley2016). In the face of a changing climate, there is an urgent need to understand natural coral reef systems (Streit et al., Reference Streit, Morrison and Bellwood2024). Understanding rubble dynamics must precede rubble restoration as a management tool in natural systems.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/cft.2025.10019.

Data availability statement

The data will be made available once processed and published in its entirety. In the meantime, colleagues can address data requests to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the First Nation peoples on whose land the One Tree Island Research Station stands, the Bailai, Gurang, Gooreng and Taribelang Bunda (FNBGGGTB) People. The authors would also like to acknowledge the Gadigal People from the Eora Nation, where the University of Sydney stands. This research has been partially funded by the Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Project DP220101125 and the Marine Resource Initiative (MRI) project with Geoscience Australia and the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Wave data from the spotter buoy was processed by the Coastal and Marine Science team, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW), NSW Government, Australia. This work represents a contribution to the ARISE project (UKRI grant EP/X029506/1). We thank Jody Webster and the MARS5007 2025 cohort for supporting some of the measurements. Claudia Le Quesne and Lara Talavera contributed to the data processing for the November 2022 dataset.

Author contribution

AV-C led the research, processed data and wrote the manuscript. LAP, KW, W-YS-L, RH and HB obtained and processed field data. BDM processed the Spotter Buoy wave data. APdS, LM-S, MB, TEF, TS and EB contributed to data analysis. All authors contributed to writing and editing the manuscript.

Financial support

This research has been partially funded by the Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Project DP220101125 and the Marine Resource Initiative (MRI) project with Geoscience Australia and the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. LAP was supported by an RTP scholarship. KW and APdS were supported by DP220101125.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Comments

Dear Professor Tom Spencer,

I am pleased to submit our manuscript, titled “Grooves in forereefs act as transport channels to deliver coral rubble during tropical cyclones”, for consideration as a Rapid Communication in Coastal Futures.

This study documents a rare and consequential sediment transport event following a sequence of climate-related disturbances on the Great Barrier Reef. In the early months (Austral summer) of 2024, the reef experienced the 9th global bleaching event, with catastrophic impacts at One Tree Reef, a site of longstanding significance in Geoscience. One year later, in March 2025, Tropical Cyclone Alfred remobilised the resulting rubble and transported it onto the reef flat.

While grooves (the channels of Spur and Groove systems) have long been suspected to play a role in sediment dynamics, the prevailing view has been that it is “impossible” for rubble to move upslope through them to the reef flat. Our manuscript shows the first evidence that large volumes of coral rubble are delivered to the reef flat through these grooves. We present qualitative and quantitative drone surveys and field measurements of topography and bathymetry to document this process.

These findings challenge long-standing assumptions about sediment delivery mechanisms on coral reefs. They carry immediate implications for coral island sediment budgets, interpretations of past reef-building processes, and forecasts of reef and island evolution under climate change. These insights are specially timely given their relevance to increasingly used restoration strategies (e.g., rubble stabilization) and to global sustainability efforts, particularly United Nations Sustainable Development Goals related to Small Island Developing States (SIDS) such as SDG13 (Climate action), SDG14 (Life below water), and SDG 11 (Sustainable cities and communities). These insights are especially timely given the relevance to millions of people globally whose livelihoods and sovereign marine resources are inextricably linked to coral island stability.

This Rapid Communication is well suited to Coastal Futures and will be of broad interest, to researchers studying climate impacts, island dynamics, and Earth system evolution. We did not submit to the special collection on Extreme Events at the Coast because the deadline was two months ago and in their advertisement, they did not mention Rapid Communication as one of the accepted article types. We would be happy to contribute to that collection if the editorial team think it is appropriate, and we are still on time.

Thank you for considering our submission. We believe it will make a timely and significant contribution to the journal’s readership.