Many “social problems” follow the trajectory of a life history. They seize the attention of intellectuals and the public at a historical moment, hold interest for a time, and then fade – whether “resolved” or not. Attention moves on. But the belief that the “family” presents social problems has been more durable, historically speaking. For as long as writers, whether religious or secular, have taken pen to paper, they have raised alarm about some aspect of family life: witness – to look no further – the jeremiads of religious leaders since antiquity, or the programs for a new social order advocated by conservative, liberal, and radical social thinkers ever since the Age of the Enlightenment. In America in our own day – again, to look no further – there is no religious sect, no political party, no rising generation of women and men that is wholly content with the contemporary family and regards it as an oasis cleansed of all social problems.

How historical actors have defined and interpreted those problems has varied greatly, even when one restricts the focus to a single location, a short span of time, and (for the purposes of this volume) a fairly small group of knowledge-makers: namely, American social scientists in the period after World War II, who considered the contemporary family as rife with social problems. Chapters 4–7 in this volume touch on aspects of the subject, inasmuch as the subject of family has spilled over onto the social scientific study of other problems, such as poverty, crime, urban life, and discrimination.

In this chapter, we trace how the family per se has been problematized differently at different moments in twentieth-century American intellectual history. For this purpose, we begin with a background section that sketches the prevailing approach to the family before 1945, an era when many social scientists, their eyes trained primarily on the United States, saw the modern family as an institution in the throes of social disorganization and decline. We then turn to developments in the half-century after World War II, dividing this era into two overlapping periods: the period from 1945 to the mid-1960s, when the global issue of family size gained priority as the major problem of the family; and the period from the mid-1960s to the 1990s, when those priorities shifted to the role of the family in the transmission of social inequality in American society.

The words we have just italicized encapsulate what constituted, in our assessment of the historical evidence, the overarching problem of concern among leading social scientists actively engaged, during these periods, in discussing the phenomenon of the contemporary family; and it is from this angle alone that we examine pre- and postwar writings on the family. We want to stress this qualifier to warn readers not to expect an exhaustive coverage of social scientific work on the family in any of these periods. At every point, scholarship on the family was extensive, diffuse, and marked by crosscurrents; conversely, occasionally social scientists showed little interest in picturing the family as a major problem at all. This literature defies the intellectual historian's impulse to characterize it as a totality, or to boil it all down to this or that theory or empirical claim – however significant that theory or claim becomes in retrospect (whereas, when viewed in context, it was often just another eddy in a vast intellectual sea). Following the example of other chapters in this book, we will concentrate on the ideas of sociologists and, to a lesser degree, on those of economists, with no more than a few side-glances into other academic disciplines. At the same time, our narrative will consider the research of an overlapping, multidisciplinary group of experts, namely, demographers, who played a pivotal part in conceptualizing the problems of the contemporary family in the postwar period.

Across these time periods, there was a tendency among the social scientists whose ideas we consider to regard the family as a conduit that channels certain broad (or macro-level) social forces to small kinship groups comprised of interacting individuals whose (micro-level) behaviors combine to reproduce (or change) those broader forces. Where does this circular process start or end? what weights attach to particular moments of it? and what drives it? On these questions social scientists have disagreed.Footnote 1 Likewise, they have disagreed over whether social conditions or problems external to the family “cause” its internal problems, or whether ameliorating the latter furnishes a “solution” for larger social maladies.Footnote 2 In either case, social scientists have generally held to the convention of using the word “family” (at least when affixed to Western societies in the twentieth century) to refer to a nuclear family consisting of a heterosexual couple and small number of children.Footnote 3 Indeed, for most of the authors mentioned in this chapter, the standard practice was to regard contemporary societies in which a large number of households depart from this norm as prima facie evidence that something had gone wrong: that the family was a social problem of one kind or another.

2.1 Historical Background: The Problem of Family Disorganization and Decline

Writing in 1926, Ernest Burgess, a leading figure at the venerable Department of Sociology at the University of Chicago and one of the nation's premier sociologists of the family, looked back on his speciality area as it stood at the time America entered World War I.Footnote 4

Nine years ago I gave for the first time a course on the family. There was even then an enormous literature in this field. But among all the volumes upon the family, ethnological, historical, psychological, ethical, social, economic, [and] statistical … there was to be found not a single work that even pretended to study the modern family as a behavior or as a social phenomenon.Footnote 5

The comment shows the myopia of the young academic (Burgess was barely 30 in 1917): He conceded that, “yes,” other writers – economists included – had dealt with the family, but complained that they had all failed at the job, coming up short with regard to the concepts suitable for understanding the contemporary family. The historical part of the claim was inaccurate. Since the start of the American university in the 1880s, social scientists had been analyzing the phenomenon of the family – and its attendant problems – with concepts akin to those Burgess would use. This was true, for example, of Albion Small and George Vincent in An Introduction to the Study of Society Reference Sawhill(1894) – the urtext of the Chicago School of sociology – as well as W. E. B. Du Bois in The Philadelphia Negro Reference Du Bois(1899), Charles Ellwood in Sociology and Modern Social Problems Reference Ellwood(1910), and James Dealey in The Family in Its Sociological Aspects Reference Dealey(1912).

Even so, Burgess saw older works like these as amateur efforts when compared with an alternative opened up by the encompassing theory of social change that he and his senior colleague Robert Park had set forth in their Introduction to the Science of Sociology Reference Notestein(1921). This theory centered on social “institutions” – economic organizations, the state, the legal system, churches, and so forth – and on how they function when buffeted by major transformations of the time: viz., industrialization, internal migration, foreign immigration, and urbanization. To make sense of these changes, Park and Burgess proposed a three-stage model of organization–disorganization–reorganization. Citing observational studies and descriptive statistical data, they asserted that macro-level changes undermined the well-integrated institutions of the past, destabilizing them up to the point where they reorganized in order to function effectively under modern conditions.Footnote 6

Extending this grand theory specifically to the family, the Chicagoans maintained that here too was a social institution in the midst of social change. As such, it was experiencing a concatenation of dislocations that went with the stage of social disorganization.Footnote 7 Topping the list of these dislocations was the nation's rising divorce rate, but other problems drew extensive notice by sociologists: declining marriage and fertility rates, rising numbers of out-of-wedlock births, marital discord and dissatisfaction, the breakdown of parental oversight of children's development, desertion of the household by husbands/fathers, and employment outside of the household by wives/mothers.Footnote 8 By the later 1920s, these problems were the subject not only of dozens of articles in sociological journals, but also of such classic books as Social Problems of the Family (Reference Greenhalgh1927) by Ernest Groves and Family Disorganization (Reference McLanahan and Percheski1927) by Ernest Mowrer (a student of Burgess).Footnote 9

To some sociologists, however, there was an important difference between the family and many of the other social institutions embraced within Park and Burgess's model. Whereas institutions such as the state and the economy moved over time from the stage of disorganization to the stage of reorganization, the family showed little movement toward reorganization, because the social role of the family was shrinking. That, at any rate, was the assessment of social scientists like Burgess's Chicago colleague William F. Ogburn, who proposed that “there had been a decline in the institutional functions of the family.” He elaborated:

In colonial times in America the family was a very important economic organization …. The home was … a factory. Civilization was based on a domestic system of production of which the family was the center.… But changes set in as manufacturing technique evolved, as economic division of labor progressed and as trade developed.… This loss of economic functions has been a factor in many social questions, including the position of women in society, the stability of the family and the birth rate. [Furthermore,] the family has been losing other functions as well. The government is assuming a larger protective role with its policing forces, its enormously expanded schools, its courts and its social legislation. Religious observances within the home are said to be declining. [As well,] it has been said that some homes are merely ‘parking places’ for parents and children who spent their active hours elsewhere.Footnote 10

Rather than question any of these what “has been said” statements, moreover, Ogburn plied on, attributing these problems – along with “increased divorce,” “broken homes,” and “defective personality development” – to “the weakening of the functions which served to hold the family together.” In his view, although these maladies especially beset “poorer families,” no income group was immune; rather, all could benefit from publicly supported “efforts to deal with family problems,” through (for instance) social work services and family clinics.Footnote 11

In these proposals to strengthen the family, we see the activist spirit of the New Deal, which was then taking form, drawing on the advice of academic economists, political scientists, sociologists, and legal experts.Footnote 12 To be sure, repairing the American family was not among the principal objectives of the New Deal. Nevertheless, the adverse effects of the Great Depression on families were plain to everyone, and government interventions into the family life – via unemployment insurance, housing assistance, aid for children in fatherless households, and job creation programs – were parts of the New Deal mix.Footnote 13 Behind these policies, furthermore, lay the research of experts from the Bureau of Agricultural Economics (a research branch of the US Department of Agriculture from the 1920s to the 1950s). These experts included rural sociologists and farm economists who studied the “family-farm institution,” and researchers in the emerging speciality area of “home economics,” who grappled with topics such as “the economics of household consumption” and the “economic choices” made by “family units.”Footnote 14 The Bureau produced major monographs such as sociologist Conrad Taeuber and Rachel Rowe's Five Hundred Families Rehabilitate Themselves Reference Smelser and Bates(1941).

None of this work called into dispute the Chicago School's “social disorganization” template, which was nothing if not adaptable. During the Depression and the New Deal, studies of the topic continued at a brisk pace, with “economic disintegration” included prominently among the sources of family disorganization – as, for example, in monographs like Robert Angell's The Family Encounters the Depression Reference Angell(1936), Ruth Shonle Cavan and Katherine Howland Ranck's The Family and the Depression Reference Cavan and Ranck(1938), and Winona Louise Morgan's The Family Meets the Depression Reference McLanahan, Casper and Farley(1939). The looming entry of the United States into World War II furnished another occasion to extend the concept, with family researchers, such as sociologist Willard Waller and his collaborators sending up alerts about the “disorganizing effect of the war,” especially its “disintegrating influence” on the family, where it “leaves a heritage of damaged family solidarity, mounting divorce and increased delinquency.”Footnote 15 This way of thinking pervaded the well-noticed publications of the National Council on Family Relations (NCFR), a multidisciplinary nonprofit organization, which Burgess cofounded in 1938 to promote academic research and social policies to remediate family disorganization.Footnote 16

Nevertheless, perhaps the most influential application of “social disorganization” appeared in studies of the African-American family. Here, the seminal work was The Negro Family in the United States Reference Frazier(1939), authored by another Burgess student, E. Franklin Frazier, who sought to make sense of the “tide of family disorganization [which] followed as a natural consequence of the impact of modern civilization upon … Negro families,” and which registered in problems such as “immorality, delinquency, desertions, and broken homes.”Footnote 17 Drawing on the analysis Frazier provided, the Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal, visiting the United States in the late 1930s, painted an identical picture of family problems in his 1,500-page best seller An American Dilemma Reference Morgan(1944). Going forward, similar accounts of the African-American family appeared as well in works like Black Metropolis Reference Drake and Cayton(1945) by St. Clair Drake and Horace Cayton – young scholars trained at the University of Chicago – who plumbed the “social disorganization in the Black Ghetto.”Footnote 18

While the Chicago School's practice of viewing family problems through the lens of “disorganization” remained strong into the late 1930s and throughout the war, two other perspectives were, by that time, also attracting growing attention among social scientists. Neither of these contradicted the approach of Park and Burgess and their students, and it was not unusual to find the different approaches comingling. All the same, these perspectives threw into relief phenomena that were less visible from the angle of “social disorganization.”

One of these was social stratification: the hierarchical arrangement of the members of a society into different social strata. At certain points in modern intellectual history, social scientists have equated social strata with “classes” in a Marxist sense (of ownership of the means of production). But during the interwar and wartime period, most American sociologists – along with anthropologists and economists interested in social structures – treated social strata, or “classes,” in a colloquial sense, as groups constituted on the basis of some combination of occupation, income, inherited wealth, social prestige, and education. Matters of definition aside, this period was the era of community network studies in an ethnographic vein mined by Robert and Helen Lynd in Middletown Reference Levy(1929) and Middletown in Transition Reference Lewis(1937) and excavated further by W. Lloyd Warner, a Harvard social anthropologist turned University of Chicago sociologist. Intentionally centering his research on midsize American towns that were “better integrated” than the disorganized urban areas that inspired Park and Burgess, Warner and his collaborators produced a series of books that described the family lifestyle differences of the upper classes, middle classes, and lower classes, and then analyzed the consequences of these differences. They also examined the incidence (by social class) of problems such as divorce, illegitimacy, and female labor force participation, and they brought into the foreground the problem of social mobility, which they conceptualized in terms of the differential chances that individuals had of moving up or down the socioeconomic status (SES) hierarchy – thereby gaining or losing economic, political, and social advantages.Footnote 19

The second perspective that gained salience during this period bore the strong impress of World War II. A joint production of sociologists, cultural anthropologists, and social psychologists, this perspective repurposed research on the relationship of family structure, child-rearing methods, and personality formation in order to plumb the roots of democracy and authoritarianism – political systems that scholars regarded as underpinned by different learned sets of cultural values and patterns of conduct.Footnote 20 Galvanized most immediately by the Frankfurt School's Studien über Authorität und Familie (Horkheimer, Reference Hodgson1936), but drawing intellectual support from the multidisciplinary field of “culture and personality,” this literature on family political socialization (as we would now call it) grew rapidly. Issues of the American Sociological Review from the late 1930s, for instance, contained articles on the problems associated with the German family, the Chinese family, and the Soviet family (as contrasted with the democratically organized American family); and the wartime years unleashed a flood of “national character” studies, often funded by the federal government, in which researchers examined the family origins of the attitudes and behaviors of the modal – highly stereotyped – personalities of peoples of foreign nations. Continuing in this tradition, this era also launched the research project that eventuated in The Authoritarian Personality Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Nevitt Sanford(1950), where émigré Theodor W. Adorno (and his multidisciplinary team of collaborators) elaborated and empirically tested the thesis that authoritarian personalities arose from families that used punitive child-rearing practices.

In different ways, these modes of thinking about the family – in terms of social organization, social mobility, and political personality formation – drew increasingly on information contemporaries usually referred to as “demographic.” In the early years of the Chicago School, this information generally amounted to little more than raw figures that untutored researchers in various subfields culled from local government records by counting and percentaging the number of people in this or that demographic category (age, employment status, and so on). During the Great Depression, however, experts in the subject began to appear on the American intellectual landscape in conjunction with the development of the field of demography. This speciality traced its origins as a profession to the founding in 1931 of the Population Association of America (PAA), which consisted initially of a tiny, loose-knit, and heterogeneous assortment of researchers from sociology, economics, biology, and statistics, as well as officials at insurance companies and other private organizations interested in the size, composition, and distribution of the nation's population and, by extension, in statistical projections of birth and death rates. Funded by the Milbank Memorial Fund (MMF), a foundation seeking to develop a national population policy, the membership of PAA was often split in its views about basic population trends, with some researchers worried, for example, about the rapid growth of the American population, others by its shrinking size.Footnote 21

As important as demographers’ debates over matters of substance was the emerging infrastructure of demographic research. Here again the MMF took the lead, establishing at Princeton University in 1935 the Office of Population Research (OPR), which launched and thereafter maintained a successful program of research on fertility and mortality rates and population movements, which by the 1940s turned “primarily toward international demography.”Footnote 22 Office of Population Research's success occurred even though it was little more than a poorly attached institutional satellite, partly because neither at Princeton nor anywhere elsewhere was there a separate “Department of Demography” (an institutional constraint that remains true even now, in the 2020s). As a result, OPR subsisted mainly on funding from extramural sources, in particular private foundations. Also, as many of the lead researchers at OPR had faculty appointments in sociology departments (at Princeton or elsewhere), it was with sociology that demography tended to be affiliated organizationally. Even when these affiliations with sociology were the strongest, however, demography functioned more as an “interdiscipline” than as a freestanding discipline in its own right.Footnote 23 (Due to this organizational peculiarity, individual demographers have typically had one foot in their “home” department and another in its adjacent demography unit. To convey this fact, we will use hyphenated neologisms, such as “sociologist-demographer” or “economist-demographer,” except in passages where “demographer” suffices.)

Significantly, the early years of OPR coincided also with a heavy stream of demographic research issuing from various agencies of the federal government in response, first, to the New Deal demand for data on the US population and, subsequently, to the wartime need for projections of population trends in allied and enemy nations. These agencies included the Census Bureau, as well as the Bureau of Agricultural Economics, the Works Progress Administration, the National Housing Agency, and the War Production Board.Footnote 24 Working with seemingly limitless resources, the staff members at these agencies – researchers trained mainly in sociology, though also in economics, public administration, and statistics – mounted national and regional surveys that grafted additional questions onto familiar Census-type questions, designed to improve projections of birth rates, population makeup, internal migration patterns, and so on: questions that elicited more and more information about the problems of the American family. The move toward seeking such data was a natural one; for, from demographers’ concerns about the size and composition of populations, there soon arose a strong interest in the primary site for population reproduction, viz., the family – and, therefore, in reliable data on birth rates, marriage rates, the age distribution of women and men at marriage, divorce rates, rates of illegitimacy, and so forth. These data proved relatively easy to collect and analyze by increasingly sophisticated statistical methods. Out of the 1930 decennial Census, for example, came a large volume entitled Families. When Paul Glick (a new PhD in sociology from the University of Wisconsin) joined the Census Bureau in 1939 as a “family analyst,” one of his first assignments was to augment the research in Families with “ten book-size reports from the 1940 census that dealt with family composition, age at marriage, fertility, employment of women, family income, and housing characteristics of families.” Immediately afterward, wartime conditions stimulated a demand for an even broader range of “marriage and family statistics,” as sociologist-demographer Philip Hauser (a freshly minted University of Chicago PhD, then working at the Census Bureau) described.Footnote 25

Around the same time, Hauser also predicted that “population problems will be among the major problems of postwar adjustment,” and that “in the troubled days which lie ahead” demographers will play an increasingly central role.Footnote 26 Not surprisingly, Hauser's predictions were borne out. Owned exclusively by no single academic discipline, these data would become the lifeblood for social scientists concerned with the family as a social problem.

2.2 Postwar Period I, 1945–1965: The Problem of Family Size

During the two decades that followed World War II, all of these approaches continued forward, some changing in the number of adherents they attracted, some changing in their substantive character. For its part, the idea that family problems were part of a larger process of social disorganization slowly waned, as the model itself faded throughout sociology in tandem with the dwindling influence of the Chicago School. Yet many of the family maladies that earlier writers had included under the header of “disorganization” remained subjects of active investigation among researchers who identified with the speciality area of “the sociology of the family” – or “family studies,” as scholars outside of sociology often called it. As represented in the area's flagship journal, the Journal of Marriage and Family (a publication of the NCFR), this list of topics continually expanded, with more articles on premarital sexuality, birth control, the mental and physical health of the family members, the family life cycle, and (perhaps above all) the strains between the “sex roles” of husbands and wives inside and outside the household.Footnote 27

To social scientists within and outside the sociology of the family, this work sometimes felt lightweight and insignificant, leading to calls to rethink its agenda. This was the view of leading family sociologist Leonard Cottrell, who wrote of his subfield in 1948: “there is little or no concerted attack on a carefully selected series of problems which are agreed upon as fundamental; … for the most part, research is being conducted by scattered and isolated investigators who are frequently working on relatively trivial problems.”Footnote 28 Even so, new conceptual winds blew through the area now and then, as in 1947 when family sociologist Reuben Hill interjected the factor of individual economic choice into a discussion of the social problems of the family, asserting that

A man can get his meals cooked and his clothes mended more cheaply without a wife than with one. Most able-bodied women can provide themselves with better clothes through their own efforts than with the pay envelope of a husband. Economically, marriage has become a luxury and parenthood a positive expense. Most couples actually live more frugally together than they did separately; they economize to marry.Footnote 29

Looking beyond the subfield of the sociology of the family per se, one finds, too, expanding bodies of research on most of the other problems we flagged in the previous section. We see this in the honor roll of classic ethnographic accounts, by anthropologists and sociologists, of underprivileged urban communities – with some of these studies emphasizing the role of cultural beliefs (the so-called culture of poverty), others the role of social-structural factors (racial and ethnic discrimination, residential segregation, and limited employment opportunities) in perpetuating the collateral problems of family life. These classics included Hylan Lewis's Blackways of Kent Reference Latham(1955), Elliot Liebow's Tally's Corner Reference Lazear(1967), and Ulf Hannerz's Soulside Reference Halfon(1969).Footnote 30 In different ways, these case studies descended from Frazier and Warner, whose influence also lay behind the advances made throughout this period in theories of social stratification and in the refinement of statistical techniques for analyzing intergenerational mobility.Footnote 31

On top of all of this, there was an explosion of research on the relationship between family socialization and troublesome kinds of personality development. Some of this work took the form of wide-angled books, mixing sociology with anthropology, such as C. K. Yang's The Chinese Family in the Communist Revolution Reference Warner and Lunt(1954), Ezra Vogel's Japan's New Middle Class Reference Taeuber and Rowe(1963), and H. Kent Geiger's The Family in Soviet Russia Reference Geiger(1968). More typical were smaller-scale studies, often by social psychologists, of the effects of different culture-based and/or class-based child-rearing styles on children's attitudes and behaviors, political and otherwise.Footnote 32

Dwarfing all these problems, however, was the problem of family size, which had stayed for decades on the periphery of social scientific research, but now moved to the forefront. Here, the geopolitics of the Cold War era provided the backdrop. For no American social scientist of the postwar period was unaware that she or he was living in a world overshadowed by the military, economic, and ideological rivalry between the Soviet and American powers, as each bloc fought to control the “new nations” of the “Third World.” Under this new order, American foreign policy interests centered on containing the threat of communism and spreading Western-style capitalism, Western-tinted democracy, and Western-flavored values to nonaligned and decolonizing countries. The American federal government – particularly the Department of State and the Department of Defense – often looked to the nation's social scientific experts to illuminate how to achieve these new developmental objectives, all of which the Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy administrations took deadly seriously. Vice versa, American social scientists eagerly latched onto these objectives as compelling rationales for their scholarship, holding fast to “economic growth” as the sine qua non of national development and to “democracy” as its prima facie mode. From these grand notions, scholars were led to assign priority to the problem of family size, endowing it with nothing short of world-historical significance.Footnote 33

We see this, in the first instance, in writings coming from the theoretical side of the social sciences – writings intellectual historians have subsequently lumped together under the loose (and sometimes misleading) rubric of “modernization theory.” Expressed in different forms in different disciplines, modernization theory's most vigorous spokespersons were sociologist Talcott Parsons and many of his leading students, along with economists Walt W. Rostow and Alexander Gerschenkron, communications scholar Daniel Lerner, political scientist Edward Banfield, and psychologist David McClelland, all of whom posited an evolutionary distinction between backward-facing societies (call them “underdeveloped,” “peasant,” “agrarian,” “nonindustrial,” or “traditional”) and forward-facing societies (“advanced,” “developed,” “urbanized,” “industrial,” or “modern”), the latter resting on capitalist institutions, democratic practices, and a commitment to values such as individualism and personal achievement. Few hesitated to apply the distinction to the contemporary Cold War situation by locating the world's “new nations” in the traditional category and worrying that, inasmuch as these nations failed to modernize, they would be highly susceptible to Soviet influence and capture.

Preventing this catastrophic possibility required removing barriers to modernization, not least the problem of high birth rates and large family size. “If western civilization is to survive at all,” wrote Parsons, non-Western nations needed to adopt the form of “a modern urbanized industrial society,” a change dependent in part on declining birth rates. Traditional familial societies, however, hampered the speed of this decline, posing “a profounder population crisis very closely connected with the major problems of [the] whole society.”Footnote 34

This modernization perspective dovetailed with the views of a number of contemporary American macroeconomists. In terms of the United States, economists of varying stripes and convictions, including Arthur F. Burns, Paul A. Samuelson, James Tobin, and Milton Friedman, voiced the idea that economic growth should be a primary aim of national policymaking and a principal standard to which political leaders’ competence should be held.Footnote 35 Looking abroad, Rostow applied a similar outlook to the situation in low-income countries, stylizing the process of modernization into separate “stages,” which together ensured the conditions for “traditional societies” to experience what he termed the “takeoff” to rapid economic growth and increased development.Footnote 36

Initially, family size per se was a problem in the margins of these writings, though Parsons’ postwar essays already assigned it a greater role in the modernization process. According to his work, and that of Rostow and Lerner, for example, nuclear families that saw the usefulness of fewer children and investing resources that would otherwise be set aside for basic survival into capital formation, consumption, and familial economic “achievement” were the functional bedrocks of modernity.Footnote 37 Although other modernization theorists rarely formulated the point so crisply, most implicitly linked increased production outside the family to controlled reproduction within the family. Among those sociologists who held this view, Marion Levy and Wilbert Moore (both students of Parsons) and William Goode (Moore's student) were some of the most insistent. In his oft-cited treatise World Revolution and Family Patterns, Goode argued that the “Western” conjugal model of male-headed, small nuclear family would eventually spread globally, accompanying “revolutionary” social and economic transformations toward industrialization and urbanization.Footnote 38 The effects would include shrinking population growth rates, transitions to democratic capitalism, and increases in national economic growth in non-Western and decolonizing countries. Insofar as modernization theorists conceptualized “tradition” and social “backwardness” as global social problems, they likewise characterized nonnuclear family and kinship structures, as well as families that exhibited high fertility, as related social problems.Footnote 39

In advancing these arguments, social theorists of the period converged with researchers at the more heavily empirical end of the social sciences, demographers in particular.Footnote 40 Postwar demographers’ focus on overpopulation further shifted social scientists’ locus of concern away from the social disorganization of the American family to the “fecund family” in the “developing world” as a global social problem in need of speedy intervention.Footnote 41 Intertwined with these research developments was a far-reaching shift in the way demographers theorized demographic change itself – a theoretical shift that pushed the family into even greater prominence within their field.Footnote 42 During the prewar period, demographers’ prevailing theoretical explanation for changes in population dynamics was “demographic transition theory.” First elucidated in its classical form by sociologist-demographer Warren Thompson in 1929, this theory posited that historical declines in national fertility in Western European countries and the United States operated as ex post facto evidence of industrialization and urbanization. This classical view changed, however, in the immediate aftermath of World War II, shifting demography's geographic focus from Western countries to the developing world. The crucible for this shift was the OPR at Princeton. Whereas classical transition theory asserted that lowered fertility was a response to industrialization and urbanization, after the war OPR demographers began to assert that proactive fertility control was a necessary antecedent to the promise of modernization in these regions.

Much of this rethinking was the result of demographers’ anxieties about the global fate of capitalist democracy after the “fall of China” in 1949, when they began to wonder whether the pressures of high fertility rates in countries that had yet to experience high levels of industrialization and urbanization would breed conditions ripe for the establishment of communism.Footnote 43 Skeptical that industrialization and urbanization would proceed apace in these regions – and convinced that their high fertility rates and low mortality rates were likely impeding those processes to begin with – OPR sociologist-demographers Frank Notestein, Kingsley Davis, and Dudley Kirk, and economist-demographer Ansley Coale, became concerned that the “problem [was] too urgent to permit [them] to await the results of gradual processes of urbanization, such as took place in the Western world.” If left unchecked, overpopulation would not only stymie economic development but would also set the stage for the rise of totalitarian governments and communist rebellion.Footnote 44 Davis, by then an associate professor of sociology at Columbia University, averred that global population growth was a “Frankenstein” that would set the stage for the rise of “completely planned economies.”Footnote 45

This specter led to an enormous expansion of the infrastructure for demographic research, which had previously consisted mainly of OPR and a handful of federal government agencies. Supporting this expansion was an infusion of resources by philanthropists and government agencies, such as Frederick Osborn of the Carnegie Corporation and John D. Rockefeller III of the Rockefeller Foundation, and federal officials in the Department of State and US Agency for International Development (USAID), who were collectively concerned about stitching global population control into the fabric of American foreign policy.Footnote 46 The Ford Foundation was responsible for the creation of sixteen new interdisciplinary university centers for demographic and population research between 1951 and 1967, and foundation and federal government monies supported many of these centers’ activities.Footnote 47 Simultaneously, a number of prominent postwar demographers assumed positions of power in independent organizations that funded population research, most significantly the Population Council. From their new organizational perches, leading demographers promoted research agendas that foregrounded problems of family size, fertility decision-making, and reproductive and sexual behaviors.Footnote 48

What was more, demographic researchers did not stop with “causes and consequences,” as we have already mentioned. Instead, proponents of modernization theory and economic growthism, working in collaboration, fueled the expansion of international family planning research. One of the most influential of these collaborations was between Ansley Coale and the University of Pittsburgh economist Edgar M. Hoover.Footnote 49 Published in 1958, their study of population dynamics in newly independent India projected population growth rates in two hypothetical scenarios: one in which the Indian government promoted fertility control through programmatic policy over the next twenty-five years and another in which it made no such “special efforts.”Footnote 50 Coale and Hoover modeled rates of increase in India's population on the country's GDP per capita, thereby explicitly articulating transition theory in macroeconomic terms. Arguing that the former scenario would alleviate population pressures on national economic growth if executed appropriately, they concluded that a direct program of fertility control would free up capital to be funneled into economic growth, rather than consumption for basic survival.

For demographers, this was an opportunity to legitimize the place of lowering family size in the US government's international development endeavors. Davis reiterated his new faith in government-led family planning programs and the distribution of effective contraceptive technologies among citizens. Notestein and Kirk elaborated this line of reasoning; they appealed to American agricultural (development) economists and to political leaders alike to take the promotion of smaller family size seriously as a determinant of economic growth and political stability.Footnote 51 Set in this light, the family appeared not only as a social problem, but also as a compelling solution to a complex of related social problems. Not only this, but the revision of demographic transition theory enabled sociologist-demographers and economists to promote medical and biomedical contraceptives as “direct” technological antidotes to postcolonial underdevelopment.Footnote 52 Worth noting, too, is that in the course of fielding local family planning programs, the study of family size also opened itself up to social-psychological approaches for understanding how to change people's attitudes and behaviors at the family level, approaches that grew out of the broader behavioral sciences “revolution” of the 1950s. These included survey research to ascertain “knowledge, attitudes, and practices” regarding birth control, as well as experiments on the effectiveness of various mass communications strategies at promoting contraception and favorable attitudes toward smaller families.Footnote 53

Considering these intellectual and institutional developments together, what the period between 1945 and 1965 reveals, then, is that when it came to research on family size and international family planning, American social scientists across the major disciplines did not seek to wrest professional jurisdiction from each other. On the contrary, against the backdrop of an escalating Cold War and rapid decolonization, they collaborated to present measures for limiting family size and restraining global population growth as fruitful development aid initiatives in the service of urgent foreign policy objectives. Whereas during the prewar period, the sociological concept of “disorganization” dominated discussions of the family as a social problem, it could no longer do so after 1945. In this period, the intersecting politics of overpopulation, economic growth, and international development placed the problem of family size at the forefront of the social sciences, with demographers standing at the cutting edge.

2.3 Postwar Period II, Mid-1960s–1990s: Problem of Family Transmission of Social Inequality

The start of our first period is easy to date – this volume concerns the historical era that begins in 1945. However, there is no equivalent date – no exact calendar year – that marks the beginning of the second postwar period. Many social scientists who were active scholars in the first period remained so for decades afterward, carrying out research that was scarcely different from the work they had been doing previously – or, for that matter, from what their teachers had been doing before the war. In 1966, nearly a half-century after members of the Chicago School began framing family problems as expressions of social disorganization and institutional decline, the Journal of Marriage and Family still ran as its lead an article on “Family Disorganization: Toward a Conceptual Clarification,” while a 1989 issue of the American Journal of Sociology featured a “test of the social disorganization theory,” which dealt with “family disruption” in terms Chicagoans of the 1920s would have immediately recognized.Footnote 54 Likewise, deep into this second period, studies of family political socialization and other research on the disruptive effects of certain child-rearing practices continued to appear, even as the “culture and personality” school closed shop in cultural anthropology and social psychology.Footnote 55 Most importantly, demographic research on pressing international issues of family size, population growth, and family planning remained a tall presence in the social sciences, securely anchored in journals such as Studies in Family Planning, Demography, and Family Planning Perspectives, founded in 1963, 1964, and 1969, respectively.

For all this, however, family size and family disorganization gradually ceased to command their previous centrality among scholars in the United States. As we have seen, interest in the family went together with broad theories of social change, in particular from modernization theory. However, the death of modernization theory during this period dissolved this linkage, allowing a great deal of family scholarship to drift loose as a differentiated speciality area, with few connections to the mainland. In the previous subsection (p. 78), we quoted Reference CottrellCottrell's (1948) remark that research on the family was “being conducted by scattered and isolated investigators who are frequently working on relatively trivial problems.” By the 1980s, well-placed commentators were repeating this criticism, averring that the study of marriage and the family had become “an intellectual backwater in sociology.”Footnote 56

At this date, the list of specific family problems under active investigation was longer than ever, having grown to include newer problems associated with cohabitation, abortion, intergroup marriage, post-divorce adjustment, remarriage, job pressures on parents, and life-course changes. Notwithstanding this constantly expanding list, research on specific family problems no longer constituted a hotspot in sociology or neighboring disciplines – except inasmuch as these problems also fell within the bounds of family demography (see below). This was true despite the publication of well-respected books such as Christopher Lasch's Haven in a Heartless World Reference Kyrk(1977), Jessie Bernard's The Future of Marriage Reference Bernard(1982), Lenore Weitzman's The Divorce Revolution Reference Vogel(1985), and Arlie Russell Hochschild's The Second Shift Reference Hill(1989).

To be sure, scholarly concern over certain aspects of the family exhibited itself in other subfields. In the intellectual space vacated by the demise of modernization theory, the second period saw the dramatic growth, spearheaded by sociologists and political scientists, of comparative-historical research. In large part, these new specialties focused on the historical study of the world's resource-poor nations, usually with an eye on their economic and political struggles, but in doing so researchers often considered topics like family property holdings and kinship networks.Footnote 57 Still further, comparative-historical scholarship on wealthier nations frequently called forth analyses of household organization and domestic relations, particularly as these intersected with changing practices of gender and sexuality – and with the development of state social policies to address family problems. Then too, this second period brought a sharp uptick of ethnographic research on socially and economically disadvantaged urban areas; this research concentrated especially on African-American communities and on the “problems” of family life in these communities (see Chapter 6: The Black Ghetto).Footnote 58

These diverse lines of research drew inspiration and sustenance from real-time developments outside the academy, most visibly the Civil Rights Movement, the Women's Liberation Movement, and the protest movement against the Vietnam War, which themselves bore the influence of neo-Marxist class analytics, radical feminist thought, and theories of racial oppression and colonialism.Footnote 59 Their combined effect was to reshape American thinking about one social problem after another by inviting knowledge-makers to reckon with some of the fault lines of their own society – in other words, the overarching problem of social inequality. In the process, many more specific family-associated problems were set in a fresh, panoptic light through the research of another multidisciplinary ensemble, one in which sociologists (in their capacity as demographers) played a leading role once again, though sharing the stage with other social scientists, economists among them.

In this new era, research funding, from both federal agencies and private foundations, was of decisive importance once more. In her chapter, Alice O'Connor describes the historical context, tracing the path from the Kennedy administration's investment in programs to overcome conditions of economic deprivation in resource-poor nations to the Johnson administration's commitment to ameliorating equivalent conditions in the United States itself (see Chapter 4: Poverty). This commitment was embodied in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the simultaneous launch of the War on Poverty. Designed and operated with guidance from social scientists, these initiatives signaled growing attention to the income gap between rich and poor Americans, to questions about causes of socioeconomic inequality, and to government measures for addressing poverty and inequality. Almost immediately, these concerns turned the national and academic spotlight onto the American family.

We see this turn as early as 1965, when political scientist Daniel Moynihan, Assistant Secretary in the US Department of Labor, issued his instantly controversial report, The Negro Family: The Case for National Action. In this, Moynihan wove together the old family disorganization theory with postwar arguments about the dangers of large family size to diagnose urban poverty as the result of the “highly unstable … family structure of lower class Negroes.” Moynihan saw this condition reflected in demographic trends like rising rates of illegitimacy and divorce in African-American communities, as well as in the growing prevalence of large households headed by single mothers.Footnote 60 This strong emphasis on the family reappeared the following year in a Department of Health, Education, and Welfare report, Equality of Educational Opportunity. Written by sociologist James S. Coleman on the basis of research carried out under a contract from the Department, the report purported to show that students’ academic performance was more strongly influenced by their family backgrounds than by the resources of their schools. For most social scientists and policymakers, the immediate takeaway was that families created inequalities of educational opportunity that public spending on schooling could not of itself eradicate.Footnote 61

Influential though they were, government reports like these relied on cross-sectional data, which did not allow researchers to nail down causal relationships between factors (e.g., family characteristics, community conditions, and family SES). Better data and data-analytic techniques were in the pipeline, however. In 1968, for example, Office of Economic Opportunity officials invited economist James N. Morgan (of the University of Michigan's Survey Research Center) to conduct a multiyear survey of 2,000 low-income households – an invitation Morgan accepted provided the study would also include, for the purposes of a broader study of social inequality, 3,000 nonpoor households. Eventually, this survey evolved into the multidisciplinary Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), which has run continuously to the present day, generating troves of information on American families and their members, considered intra- and intergenerationally. This information has included data on race, fertility, family size, marriage and divorce, out-of-wedlock births, childcare arrangements, schooling, labor force participation, earnings, occupational mobility, wealth, health, and the use of government services. By the year 2000, these data yielded literally hundreds of articles, appearing in leading journals of economics, sociology, and demography, on the interface between socioeconomic inequalities and other family problems. The PSID data also resulted in a ten-volume series – Five Thousand American Families – where economists sympathetic to government assistance policies argued that poverty is not a permanent condition, but one that many families cycle through, pulled out with the aid of government safety net programs.Footnote 62

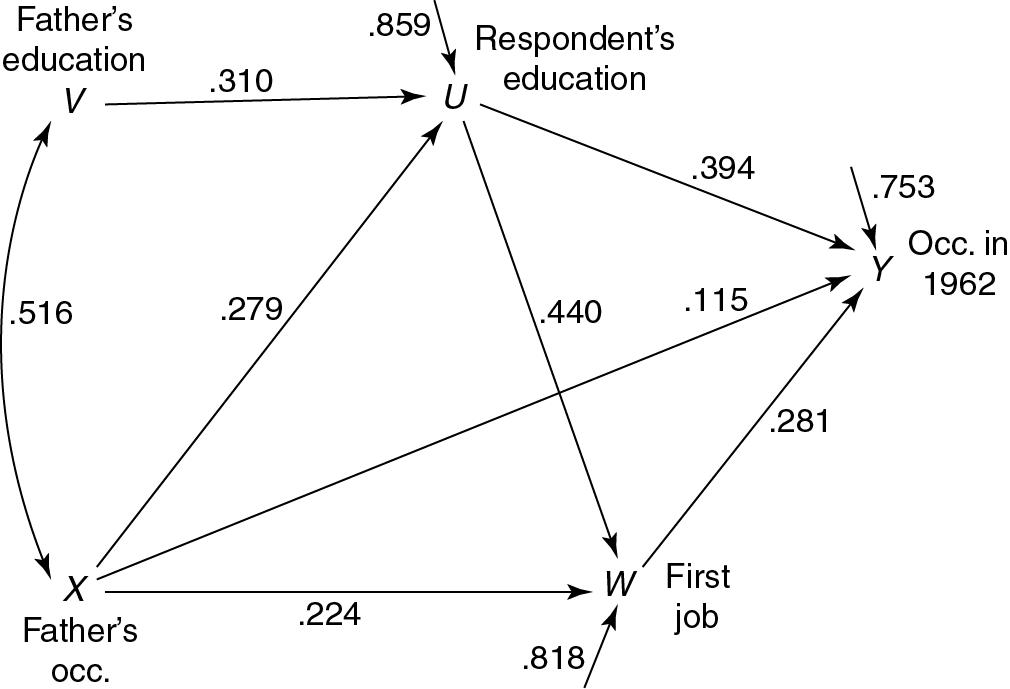

Nearly simultaneous with the launch of the PSID was the publication in 1967 of a landmark study of social inequality, The American Occupational Structure, by sociological theorist Peter Blau and sociologist-demographer Otis Dudley Duncan, who followed the tradition of social mobility research that went back to Warner and Frazier. Using a 1962 survey of over 20,000 men, which was carried out by the Census Bureau and funded by grants from the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, Blau and Duncan examined the intergenerational transmission of social inequality through the prism of the jobs that survey respondents held in the nation's “stratified hierarchy of occupations.” The authors’ central thesis was the dual argument that, “for the large majority of men” the “primary determinant” of social class position was their occupational position and that occupational position was “affected,” in turn, by the social background factors they brought with them when they entered the labor market. Blau and Duncan illustrated the latter contention by means of a “path diagram” – a mode of multivariable statistical analysis their book made famous. In its “basic” form, their model of occupational “attainment” took the shape depicted in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 Path diagram from Peter Blau and Otis Dudley Duncan's The American Occupational Structure (Reference Blau and Duncan1967), 170.

The upshot of this social mobility model was that a man's occupation in 1962 – the “dependent,” or outcome, variable on the right side of the diagram – was determined by a set of “independent” variables (here, the respondent's father's education and occupation), as well as by mediating, or “intervening variables” (here, the respondent's education and first job).Footnote 63 Blau and Duncan then elaborated the model by incorporating other variables, including the respondent's race, level of educational attainment, and, significantly, “the structure of [his] family relations” (size of his parental family, marital status, number of children fathered, and so on). In this way, they made the phenomenon of “family” into a nexus of variables that served to transmit the inequalities existing in one generation into inequalities in the next generation.Footnote 64 In the spirit of the War on Poverty, Blau and Duncan saw this evidence as promoting the cause of equality of opportunity. For, what their data suggested was that “helping children from large families to obtain a better education would suffice to remove the occupational disadvantages they now tend to experience, [whereas] the compounded handicaps of Negroes … would have to be attacked on many different levels.”Footnote 65 (Blau and Duncan did not spell out what this multilevel attack would look like.)

The American Occupational Structure provided a flexible template for literally hundreds of subsequent studies of social inequality.Footnote 66 In some of these, researchers zeroed in on particular variables (say, family structure) in Blau and Duncan's model and on their determinants. In other cases, investigators focused on other outcome variables, substituting educational attainment or income (for example) for occupational position. And in still other instances, researchers examined the direct and indirect effects of additional variables: school characteristics, religious affiliations, measured intelligence, age, mental health and health conditions, subjective aspirations and attitudes, and numerous spousal attributes. Up until the mid-1970s, many of these studies stuck to path-analytic statistical approaches, although these methods were gradually replaced by log-linear regression and survival analysis, which were better suited to the testing of causal hypotheses and the treatment of longitudinal data.Footnote 67

In Blau and Duncan's book and later studies, family-related factors, while ordinarily included at some stage in the statistical analysis, were typically only part of the story of the transmission of social inequalities from one generation to the next – and, in the years ahead, this usually remained their role. That said, many researchers assigned particular importance to family factors, agreeing with sociologist Richard Curtis’s view that “households organized as families are essential units in theory on inequality.”Footnote 68 However, like many other factors in the basic Blau-Duncan model, family-related factors continually gave rise to additional questions that called out for more detailed research to measure the strength and directionality of the relationship between different family attributes and dimensions of social inequality. This research formed a substantial piece of the core of what was then crystalizing as the speciality area of “family demography.”Footnote 69

From its outset, this speciality found its academic home base in the cluster of population or demography centers that had been established in our first period. This was so because research of the sort pioneered by Blau and Duncan was “big science”; it made heavy logistical demands that were beyond the capacity of solo family researchers. These demands included managing giant data sets purchased from the Census Bureau and other agencies; conducting large, PSID-like panel studies; maintaining state-of-the-art computational facilities; and preparing multi-million dollar grant applications to the federal government and private foundations to cover the expenses of all these things, as well as the salaries of support staff of professionals in nontenured academic positions.Footnote 70

By and large, grants of this type were project grants, attracting the interest of external funders, though only so long as funders’ attention held firm. While precarious, this funding situation had the upside of continually enlarging the bounds of family demography, bringing within its jurisdiction one social problem after another, most of which researchers conceptualized as fitting into the larger study of social inequality. Sociologist-demographer Samuel Preston has described the situation:

Research directions in demography are more sensitive to demand for demographic products and less dependent on internally generated pressures than those in other social sciences…. The sensitivity of demography to external priorities [causes the field to be] associated closely with a series of perceived national and international problems. The funding generated by the search for solutions to these problems has attracted many people to the field in ‘soft-money’ positions.… When funding priorities shift, their own priorities can change.Footnote 71

This is not to say that monies to study certain older topics entirely dried up; throughout this second period, family researchers continued to find support for work on subjects that had interested academics and policymakers during previous periods, including marriage rates, divorce rates, fertility and family planning, family size, husbands’ and wives’ employment status, and so on. But now sharing the limelight were studies of the causes and effects of problems having to do, too, with new household forms (cohabiting couples, same-sex couples, female-headed households, households with aging relatives), patterns of residential and educational segregation, household financial and social resources (government benefits, child custody payments, savings, inheritances, and the availability of affordable childcare), and racial, ethnic, and generational disparities in these patterns.Footnote 72

By the end of the twentieth century, family demographers broadened their reach still further, as illustrated by a major project titled the “Fragile Families & Child Wellbeing Study,” which tracked (so far up to the age of 15) 5,000 children, most of them born to unmarried parents between 1998 and 2000. Under the direction of sociologist-demographer Sara McLanahan (from Princeton's OPR) and economist-demographer Irwin Garfinkel (of the Columbia Population Research Center), and supported with grants from the National Science Foundation, the Department of Health and Human Services, the Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and over twenty private foundations, the study asked how children born into these “fragile” families fare as they grow up, and how they are affected by government policies. To address these questions, investigators interviewed mothers and fathers (from different socioeconomic backgrounds) to collect data on their demographic characteristics, their employment, educational, health, and incarceration histories, the characteristics of their neighborhoods, their participation in government programs, and their relationships, parenting behaviors, and subjective attitudes. In addition, researchers conducted in-home interviews in order to gather information on children's cognitive and emotional development, mental and physical health, and home environments.Footnote 73

Entering the twenty-first century, family demographers’ expansionism continued. Thus, to take one example, the Center for Demography at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, with funding from the Shriver Institute and the National Institute of Aging, designated “family and households” as its top research project, clarifying that label to mean “the study of family and intergenerational factors critical to understanding population health; sociodemographic variation in formation and dissolution of family relationships, social changes contributing to these patterns (e.g., growing socioeconomic inequality); and the role of families in shaping and mitigating social and health inequalities.”Footnote 74 The chasm between, on the one hand, the multifunctional view of the family represented here, and on the other hand, the dominant prewar view of the family as an institution on the decline – a mere “parking place” – can hardly be overstated. To quote Preston's takeaway from recent work in family demography: “even in counties with the best-developed economies and state bureaucracies, the large majority of adults continue to live in intimate relations with a member of the opposite sex and to bear and raise children,” constituting family-like units that still perform “an enormous array of socially vital functions, from socializing children to caring for the elderly to transferring income.”Footnote 75

To investigate the ever-expanding list of subjects that family demographers claimed during our second period, demography centers also expanded their faculty rolls to include scholars from more and more academic disciplines.Footnote 76 Within the ranks of its researchers in family demography, an American demography center by century's end contained sociologists, economists, psychologists, anthropologists, and statisticians, plus scholars from departments of human development, public administration and public policy, social work, educational policy, nursing and other health sciences, gerontology, and environmental studies.Footnote 77 This multidisciplinary confluence facilitated the transfer of substantive and methodological knowledge across fields. In the typical case, sociologist-demographers constituted a plurality, though rarely a majority, of a demography center's faculty, and in their research on the family they proved receptive to inputs from a variety of disciplines, including economics, from which they drew advanced econometric methods of data analysis.Footnote 78

In this context, family demographers solidified their position as the leading voices in the study of the problems of the family, even in the face of criticisms of their work from scholars outside of demography.Footnote 79 Surveying social scientific research on the family in 1988, sociologist Bert Adams observed that “family demography represents the upper end of the status continuum for the family field” and that it was overshadowing – in quantity as well as in standing in the academy and beyond – other studies of the family.Footnote 80 By the 1980s, social problem-focused articles by family demographers appeared frequently in top general-interest journals like the American Journal of Sociology and the American Sociological Review. Likewise, in the period between 1987 and 1992, the leading demography journal, Demography, saw a 14 percent rise in articles in the area (the largest increase for any area), at the same time as articles on fertility and contraception dropped 12 percent.Footnote 81 When the multidisciplinary International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavior Sciences appeared in 2001, summarizing scholarship during the previous quarter century, ten of its thirteen entries on the family – including those on “Family Theory” and “Family as Institution” – were written by researchers in demography concerned with aspects of the problem of social inequality.Footnote 82

So entrenched was the approach of family demographers, in fact, that it was barely affected by the appearance of what future intellectual historians are likely to regard as the most intellectually innovative contribution to the study of the family during this second period. This was the development of what is now usually referred to as the “economics of the family,” an approach that emerged in the mid-1970s in the work of two future Nobelists in economics from the University of Chicago, Theodore W. Schultz and Gary S. Becker – the guiding lights of what proponents of the approach initially called the “new home economics.”Footnote 83 (The label later gave way to variants of the “Chicago School of family economics.”) As formulated particularly in Becker's A Treatise on the Family (Reference Becker1981), the approach stretched the tenets of mainstream economics beyond the marketplace by theorizing family behaviors as “active choices by maximizing agents” – i.e., preference-bearing individuals engaged in rational decision-making in the face of “incentives” and given “constraints.”Footnote 84 Becker mostly carried out this theorizing in abstract terms (often using mathematical formulas); his primary focus was not on empirical data, but on recasting neoclassical principles formally and then systematically deriving from them corollaries that pertained to the family – and that might, going forward, be tested empirically.

The antecedents of this approach went back to our first period, when Schultz and Becker were both focused on questions of international economic growth and family size. In a 1960 volume Demographic and Economic Change in Developed Countries, for instance, Becker argued that “student[s] of consumption economics need to pay more attention to the determinants of family size than they have in the past.” Following his own advice, he then laid out an “economic analysis of fertility” that described the problem of “family size” in terms of cost-benefit decisions having to do with prospective parents’ “demand for children” in relation to the cost of children as a “consumer durables.”Footnote 85 In the course of the next decade, partly in connection with his book Human Capital (Reference Becker1964), Becker elaborated this theory until it included decisions not only about family size, but also about marriage, divorce, the household division of labor, women's participation in the labor force, and parents’ “altruistic” investment of their resources in the human capital of their children.Footnote 86

Embracing Becker's work as a successful exercise of “economic imperialism” – a triumphant move to capture “areas traditionally deemed to be outside the realm of economic theory” – many economists followed its example, publishing dozens of rational-choice studies of the family-associated topics like those Becker wrote about.Footnote 87 Amplifying this development was the fact that, in accord with the neoliberal policy orientation of the Reagan–Bush presidencies, economists took hold of more academic bases and became even more of a force than previously in shaping national economic policy. Still further, economists’ policy attitudes at this point trended strongly in a free market direction and away from the state-interventionist programs of family researchers going back to beginnings of the social sciences in the United States.Footnote 88 Becker's views were part of this newer trend, as he made explicit: “A progressive system of government redistribution is usually said to narrow the inequality in disposable income” across families, but such a system “may well widen the inequality … because parents are discouraged from investing in their children by lower after-tax rates of return.” Indeed, for Becker and his disciples, many of the family issues on the nation's agenda were less “social problems” – as they had been throughout the twentieth century – than results of individual choices. But we should be careful of overstatement here; for even at the height of Beckerism during this second period, there were still plenty of economists (and economist-demographers) who rejected, in part or all, this conservative policy stance and its accompanying conception of the family.Footnote 89

The same was true outside of economics, where reactions to Becker's theory of the family were even more mixed. (Imperialism tends to be unpopular among peoples threatened with subjugation.) To cite a single example: The Reference Sweet2014 Wiley Blackwell Companion to the Sociology of Families, a multi-authored 27-chapter, 560-page digest of family research from recent decades, contained only two citations to Becker.Footnote 90 Elsewhere, Becker's theories fared better, in the sense that they appeared, with modest frequency, in research on subjects such as divorce and women's labor force participation. These appearances were especially visible in studies by family demographers, who could scarcely neglect the microeconomics of the family as they worked side-by-side with economists at population centers. Of the approximately 700 articles published in Demography in the 20 years after the Treatise was published, 56 (roughly 8 percent) cited the book, decoratively in some cases, more substantively in others.Footnote 91 In many of the latter instances, authors used Becker's theory to derive specific hypotheses that they then juxtaposed with alternative hypotheses in order to conduct empirical tests of competing explanations for family-related phenomena, tests that sometimes confirmed Becker's views, but most times did not.Footnote 92 And it was in this manner, too, that social scientists, in and out of family demography, generally responded to all of Becker's work: welcoming it as a go-to source of testable hypotheses that were easier to specify than those drawn from the less formal scholarship of other social scientists, but greeting his economic imperialism otherwise with deep skepticism.Footnote 93

Be this as it may, there is little evidence that the new microeconomics of the family prompted much social scientific rethinking, either during our second period or since, of the conviction that the overarching problem of the family lay in perpetuating social inequalities. For his part, Becker, aware of Blau and Duncan's work, retorted with a short chapter in his Treatise on “Inequality and Intergenerational Mobility,” which minimized the role of the family in the reproduction of inequality – consistent with his claim in Human Capital that “although earnings of parents and children are positively related, the relation is not strong.”Footnote 94 Few scholars concerned with the family were satisfied with this view. Sociologist Michael Hannan described Becker's analysis of “the heritability of parental advantage … the least convincing of the theories in the treatise,” while the eminent economist Arthur Goldberger deemed Becker's account as inferior to that of family demographers, who formed “the main line of sociological research on family background and socioeconomic achievement.” In Goldberger's assessment, Becker's microeconomic approach risked seriously “understat[ing] the influence of family background on inequality.”Footnote 95 With that overhanging problem, however, social scientists were not about to quit and move on, as they had at earlier points in the twentieth century. As our second period ended, there was yet on the horizon no family problem so pervasive, or so consuming of social scientific attention, as the family's role in transmitting social inequalities from generation to generation.