Panic disorder affects 1.1–3.7% of the general population,Reference Kessler, Chiu, Jin, Ruscio, Shear and Walters1 and panic symptoms affect around 10% of the patients in primary care.Reference King, Nazareth, Levy, Walker, Morris and Weich2 Panic disorder is characterised by resistance to spontaneous remission, comorbidity with other disorders (e.g. depression, alcohol or substance use disorders) and a debilitating course if not treated.3 In around a quarter of patients, panic disorder is accompanied by agoraphobia, defined as anxiety related to being in places or situations from which escape might be difficult or embarrassing, or in which help may not be available in the event of having a panic attack.Reference Kessler, Chiu, Jin, Ruscio, Shear and Walters1 The prognosis for panic disorder is worsened by the coexistence of agoraphobia.Reference Kessler, Chiu, Jin, Ruscio, Shear and Walters1

In recent decades, a large number of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted to examine the effects of psychotherapies for panic disorder.Reference Cuijpers, Cristea, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Huibers4 A Cochrane systematic review and network meta-analysis (NMA) did not find high-quality unequivocal evidence to support one psychological therapy over the others for the treatment of panic disorder.Reference Pompoli, Furukawa, Imai, Tajika, Efthimiou and Salanti5 It identified cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) as often superior to other therapies in terms of symptom reduction, although the effect size was small and the level of precision was often insufficient or clinically irrelevant. Moreover, the NMA did not include all available types of psychotherapy, did not consider different treatment delivery formats other than face-to-face sessions and did not consider studies comparing psychotherapy with pharmacotherapy. As a result, a substantial proportion of evidence that could have contributed to estimating the relative efficacy of different forms of psychotherapy was missed. Therefore, there is uncertainty about which psychotherapy should be considered first line in people suffering from panic disorder with or without agoraphobia.

Against this background, the present systematic review and NMA assessed the comparative efficacy and acceptability of different types of psychotherapy for the treatment of adults with acute-phase panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia. For each intervention, the probability of being at each possible rank was calculated. Ranking treatments in a hierarchical order is a straightforward and user-friendly way to inform practitioners, policymakers and other stakeholders.

Method

This study was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines specific for NMAReference Hutton, Salanti, Caldwell, Chaimani, Schmid and Cameron6,Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow7 (see also supplementary Appendix A, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.148). The study protocol was published in advance in PROSPERO (CRD42020206258) and in a peer-reviewed journal.Reference Papola, Ostuzzi, Gastaldon, Purgato, Del Giovane and Pompoli8

Study selection and data extraction

We searched the electronic databases MEDLINE, Embase, PsycInfo and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) from database inception to 1 January 2021 (for the full search strategy, see supplementary Appendix B). The electronic database searches were supplemented with manual searches for published, unpublished and ongoing RCTs. Two investigators independently assessed titles, abstracts and full texts of potentially relevant articles following the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.Reference Higgins, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch9 We extracted data from the original reports using standardised data extraction forms.Reference Papola, Ostuzzi, Gastaldon, Purgato, Del Giovane and Pompoli8

We included studies comparing any kind of psychotherapy with any control condition, including another psychotherapy, for the treatment of adults (18 years or older, of both genders) with a primary diagnosis of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia according to any standard operationalised criteria (Research Diagnostic Criteria, DSM-III, DSM-III revised, DSM-IV, DSM-IV text revision, DSM-5 and ICD-10). Participants had to be in the acute phase of their disorder at the time of enrolment in the RCT. We included RCTs enrolling participants with comorbid disorders. Psychotherapies could be delivered by any therapist or as self-help. Different treatment delivery formats were allowed, including individual or group face-to-face, telephone and guided or unguided self-help (supplementary Appendix C). Psychotherapies and comparators were grouped, according to predefined categories, into 16 homogeneous groups that represented the ‘nodes’ of the network analysis (supplementary Appendix C).Reference Papola, Ostuzzi, Gastaldon, Purgato, Del Giovane and Pompoli8 We set no limits in terms of duration of treatment, number of sessions and minimum number of participants. D.Pap., C.G., G.O., E.K., M.S. and A.P. independently extracted data using a structured and piloted form. Data extraction included, in addition to outcomes, information on a vast array of clinical and methodological trial characteristics, as described in the protocol.Reference Papola, Ostuzzi, Gastaldon, Purgato, Del Giovane and Pompoli8 Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus and arbitration by one of the senior authors (T.A.F., P.C. or C.B.).

Risk of bias assessment

We assessed the risk of bias of the included studies using the Cochrane ‘risk of bias’ tool 2nd version for randomised trials (RoB 2).Reference Sterne, Savović, Page, Elbers, Blencowe and Boutron10 D.Pap., D. Pau. and M.P. independently used the RoB 2 signalling questions to form judgements for the five domains of the tool. Since ‘blinding [masking] of participants and personnel to treatment allocation’ (in domain 2) is not possible in psychotherapy trials, we did not assess that item, to avoid all the trials being at high risk of bias by default.Reference Papola, Ostuzzi, Gastaldon, Purgato, Del Giovane and Pompoli8 Thus, domain 2 was limited to the evaluation of the type of statistical analysis that was carried out (‘intention-to-treat’, ‘modified intention-to-treat’, ‘per protocol’, ‘as treated’). Disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus with a third author (T.A.F., P.C. or C.B.).Reference Papola, Ostuzzi, Gastaldon, Purgato, Del Giovane and Pompoli8 To better test the transitivity assumption and to enable an examination of research gaps, we complemented the information coming from the RoB assessment with:Reference Papola, Purgato, Gastaldon, Bovo, van Ommeren and Barbui11,Reference Purgato, Gastaldon, Papola, van Ommeren, Barbui and Tol12 (a) evaluation of therapist qualifications: to check whether the professionals involved in the study were adequately trained and supervised to deliver the interventions; and (b) intervention implementation fidelity: adherence to the intervention's manual. As these two items complemented the information on the risk of systematic errors of the included studies, we described and reported RoB and these additional items together.

Outcomes

Two outcomes were considered: efficacy in reducing panic symptoms (continuous outcome, indicated as ‘efficacy’) and all-cause discontinuation (binary outcome, indicated as ‘acceptability’). For the efficacy outcome, we selected one scale for each study using a pre-planned hierarchical algorithm,Reference Papola, Ostuzzi, Gastaldon, Purgato, Del Giovane and Pompoli8 giving priority to scales specifically developed for panic disorder (supplementary Appendix D, E and F). All-cause discontinuation was measured as the proportion of participants who discontinued treatment for any reason. All outcomes referred to the acute-phase treatment (study end-point). For each outcome, we assessed the confidence in the body of evidence from NMA using the Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis (CINeMA) application (https://cinema.ispm.ch),Reference Nikolakopoulou, Higgins, Papakonstantinou, Chaimani, Del Giovane and Egger13 broadly based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Vist, Kunz, Falck-Ytter and Alonso-Coello14 For both outcomes, we produced a treatment hierarchy by means of surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) and mean ranks, having treatment as usual as reference.Reference Salanti, Ades and Ioannidis15 Treatment as usual is defined in supplementary Appendix C (Table C2).

Statistical analysis

We performed standard pairwise meta-analyses with a random-effects model for every comparison with at least two studies. For each outcome, we performed an NMA with a random-effects model in a frequentist framework, using the Stata mvmeta package. For the continuous outcome (efficacy) we pooled the standardised mean differences (s.m.d.) between treatment arms at end-point. For the dichotomous outcome (acceptability), we calculated relative risks (RR) with a 95% confidence interval for each study. Dichotomous data were calculated on a strict intention-to-treat (ITT) basis, considering the total number of randomised participants as denominator. Where participants had been excluded from the trial before the end-point, we considered this a determination of a negative outcome by the end of the trial. For continuous variables, we applied a loose ITT analysis, whereby all the participants with at least one post-baseline measurement were represented by their last observations carried forward (LOCF). For RCTs that implemented a per-protocol analysis we considered completers data. When a study included different arms of a slightly different version of the same psychotherapy we pooled these arms into a single one (supplementary Appendix E).Reference Higgins, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch9 We asked trial authors to supply missing data or, alternatively, we imputed data using validated statistical methods.Reference Papola, Ostuzzi, Gastaldon, Purgato, Del Giovane and Pompoli8,Reference Higgins, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch9

We evaluated the assumption of transitivity by extracting potential effect modifiers (e.g. age, gender, sample size, follow-up length, number of psychotherapy sessions, training of the therapist, use of a treatment manual to deliver the therapy) and comparing their distribution across comparisons in the network. The variance in the random-effects distribution (heterogeneity variance) was considered to measure the extent of cross-study and within-comparison variability of treatment effects. We assessed the presence of statistical heterogeneity using the I 2 statistic. We statistically evaluated the presence of inconsistency by comparing direct and indirect evidence within each closed loopReference Bucher, Guyatt, Griffith and Walter16 and comparing the goodness of fit for an NMA model. This assumes consistency with a model that allows for inconsistency in a ‘design-by-treatment interaction model’ frameworkReference Higgins, Jackson, Barrett, Lu, Ades and White17 by using the Stata commands mvmeta and ifplot Reference Chaimani, Higgins, Mavridis, Spyridonos and Salanti18 in the Stata network suite. Inconsistency was further investigated using the side-splitting approach between comparisons.Reference Palmer and Sterne19

For each outcome, we conducted pre-planned sensitivity analyses excluding trials with imputed data;Reference Papola, Ostuzzi, Gastaldon, Purgato, Del Giovane and Pompoli8 excluding trials judged to be at high risk of bias in case of high statistical heterogeneity (I 2 > 75%) to explore the putative effects of the study quality assessed using the RoB 2 on heterogeneity; excluding trials in which participants were diagnosed by means of DSM-III and DMS-III-TR; and excluding trials comparing psychotherapy with pharmacotherapies. Being aware that funnel plots are of limited power to detect small-study effects we did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were fewer than ten studies.Reference Sterne, Sutton, Ioannidis, Terrin, Jones and Lau20 The decision to produce pairwise funnel plots instead of comparison-adjusted funnel plots allowed us to focus specifically on comparisons including ten or more studies, thus avoiding the production of unreliable information. If ten or more studies were included in a direct pairwise comparison, we assessed publication bias by visually inspecting the funnel plot, testing for asymmetry using Egger's regression testReference Sterne, Sutton, Ioannidis, Terrin, Jones and Lau20,Reference Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider and Minder21 and investigating possible reasons for the asymmetry.Reference Chaimani, Higgins, Mavridis, Spyridonos and Salanti22 To determine whether the results were affected by study characteristics we performed meta-regression analyses to assess whether the following covariates acted as moderators of treatment effect: mean age, gender, proportion of participants with agoraphobia, year of trial publication, RCT duration, number of sessions, treatment delivery format, country, concomitant pharmacotherapy, utilisation of a treatment manual, provision of psychotherapy by specifically trained therapists, verification of treatment integrity, and implementation of an ITT analysis. In particular, for each potential effect modifier, we first tested the hypothesis of equality of parameters related to interaction terms between the covariate and treatment indicators; then, in case of non-rejection of that hypothesis, we evaluated statistical significance of the common covariate parameter; otherwise, we assessed the global significance of each covariate–treatment interaction. Statistical evaluations and production of network graphs and figures were done using the network and network graphs packages in STATA (Windows version 16.1, SE).Reference Chaimani and Salanti23

Results

Characteristics of included studies

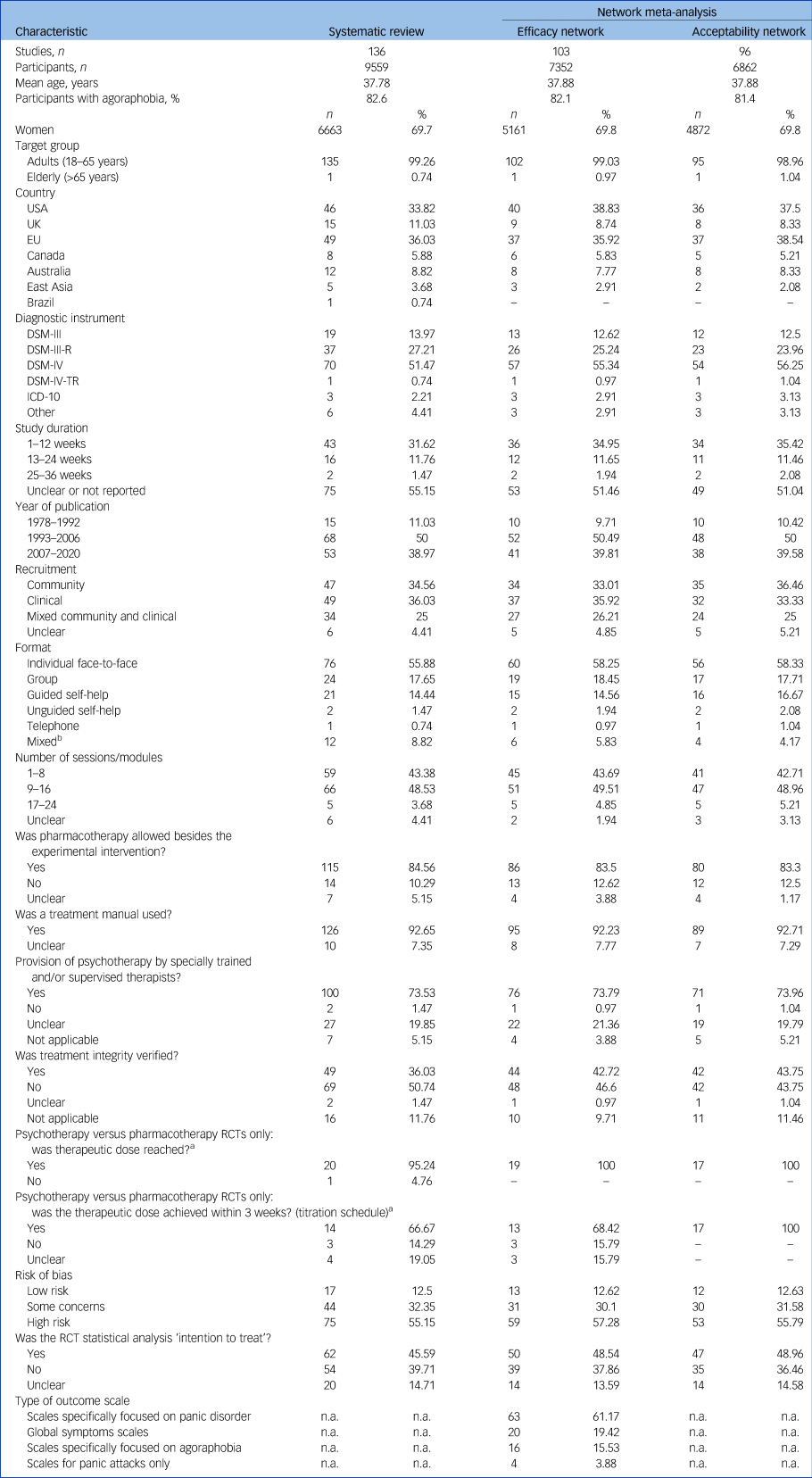

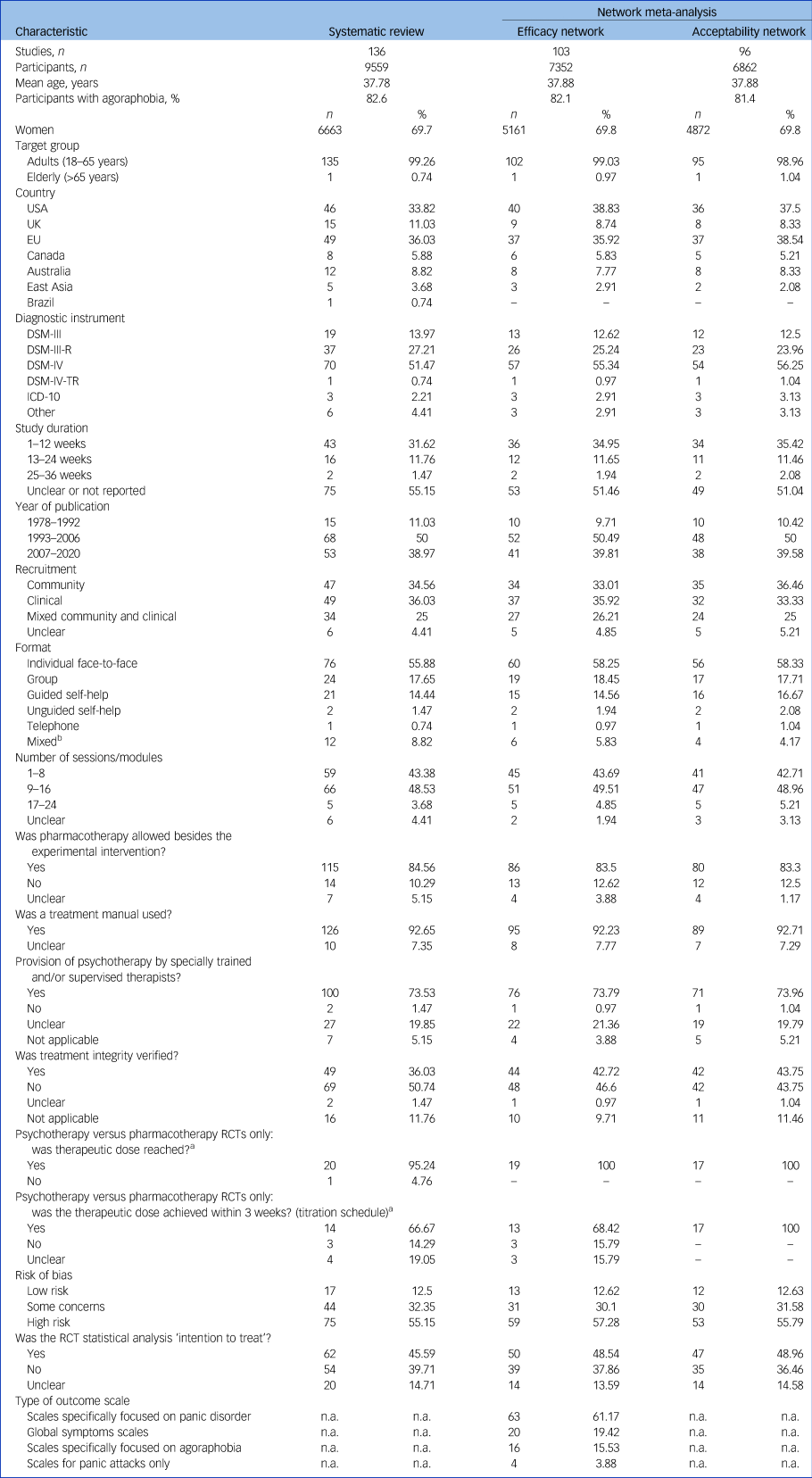

The searches identified 16 396 records. After removing duplicates and examining titles and abstracts we selected 466 records for full-text assessment (supplementary Appendix G and H). A total of 136 studies were eligible for inclusion in the systematic review (Fig. 1; supplementary Appendix G).Reference Addis, Hatgis, Krasnow, Jacob, Bourne and Mansfield24–Reference Zitrin, Klein and Woerner159 Overall, 9559 participants were randomised to 10 different psychotherapies (behavioural therapy, CBT, cognitive therapy, eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR), interpersonal therapy, physiological therapies, psychodynamic therapies, psychoeducation, supportive psychotherapy and third-wave CBT) and six different control conditions (antidepressants, attention or psychological placebo, benzodiazepines, placebo, treatment as usual, waiting list) (supplementary Appendix C, E and G). As shown in Table 1, 82.6% of the participants suffered from panic disorder associated with agoraphobia. The mean age was 37.8 years (range 29–46, with only one studyReference Hendriks, Keijsers, Kampman, Oude Voshaar and Verbraak82 including participants with a mean age of 68.6 years). The mean proportion of included women was 69.7% (range 30.1–83.3%). Only two studies included participants with a comorbid disorder.Reference Feldman, Matte, Interian, Lehrer, Lu and Scheckner71,Reference Martini, Rosso, Chiodelli, de Cori and Maina105 Around 80% of the studies were conducted in the USA, UK or Europe. Included studies were published over 42 years (1978–2020), with the great majority (89%) published after 1993. Studies were generally short (1–12 weeks) and most of the participants were recruited by clinical referral (36.0%). The most commonly used delivery format was individual face-to-face sessions (55.9%). The mean number of therapy sessions was approximately ten per RCT. As the cut-off between long- and short-term psychodynamic therapies is generally considered to be 24 sessions,Reference Gabbard160,Reference Leichsenring and Rabung161 we considered that psychodynamic therapies were ‘short-term’. Most participants were receiving medications during the treatment period: 115 RCTs (84.5% of the total) allowed various psychotropic drugs to be taken on top of the experimental and control interventions. However, the great majority of the RCTs enrolled participants only if they had been on a stable dosage for at least 1–3 months and on agreement to keep the dosages constant throughout the treatment period. Information on how to conduct each of the different psychotherapies was drawn from a total of 111 manuals/reference articles. Among the most frequently used manuals are those written by Barlow et al,Reference Barlow and Craske162 ClarkReference Clark163 and Beck et alReference Beck, Emery and Greenberg164 for the CBT area, Milrod et al's manualReference Milrod, Busch, Cooper and Shapiro165 for short-term psychodynamic therapy, and the manuals written by OstReference Öst166 and Bernstein & BorkovecReference Bernstein and Borkovec167 for physiological therapy. The full set of manual references is reported in supplementary Appendix I and J.

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1 Characteristics of randomised controlled trials included in the systematic review and in each network of primary outcomes

n.a., not applicable; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

a. Only those RCTs that randomised participants to treatment with an antidepressant were considered (n = 21).

b. Includes the following combinations of formats: ‘individual versus guided self-help’, ‘group versus guided self-help’, ‘individual versus group’, ‘guided self-help versus unguided self-help’.

Risk of bias of included studies

Seventy-five studies (55%) were considered to be at high risk of bias. Major issues in the risk of bias evaluation emerged for RoB domain 2 (risk of bias due to deviations from the intended interventions) and domain 5 (risk of bias in selection of the reported result) (supplementary Appendix K). Sixty-two studies (45.6%) implemented an ITT approach. In 54 studies, participants were analysed by means of a per-protocol analysis. Method of analysis was unclear in 20 studies (14.7%). The majority of interventions followed the guidance of a treatment manual (92.6%) and were delivered by licensed or specifically trained and supervised therapists (73.5%) but treatment integrity was verified in only 36% of studies (supplementary Appendix L). In studies comparing psychotherapy with pharmacotherapy, drugs were adequately administered both in terms of dosage and titration schedule (supplementary Appendix L).

Of the 136 studies included in the systematic review, 104 (76.5%, 7375 participants) provided data for at least one outcome (Fig. 1; supplementary Appendix E and G).

Study outcomes

The characteristics of studies included in the two outcome analyses are summarised in Table 1, and the corresponding network plots are shown in Fig. 2. The results of the NMAs for each psychotherapy are shown in Fig. 3 in the form of a net league table. For the two outcomes, all standard pairwise meta-analyses, NMAs and assessments of heterogeneity and inconsistency are reported in supplementary Appendix M and N. The transitivity assumption was carefully checked through informative tables featuring the most important participant, intervention and methodological RCT characteristics, allowing the visual inspection of similarities of factors we considered likely to modify treatment effect (supplementary Appendix E, I, and L).

Fig. 2 Network plots of evidence for (a) efficacy and (b) acceptability.

The thickness of lines is proportional to the precision of each direct estimate and the size of circles is proportional to the number of studies including that treatment; n indicates the number of participants who were randomly assigned to each treatment. Psychotherapies are represented as dark blue circles and controls as light blue circles.

Fig. 3 Net league table of head-to-head comparisons.

In the central diagonal, dark blue cells indicate interventions, white cells indicate controls. Cells below the interventions/controls diagonal show efficacy: s.m.d. and 95% confidence intervals are reported; s.m.d. < 0 favours the column-defining treatment. Cells above the interventions/controls diagonal show acceptability: relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals are reported; RR < 1 favours the column-defining treatment. Statistically significant results are in bold, with the corresponding cells also darker. CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; EMDR, eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing.

In terms of efficacy (103 RCTs, 7352 participants), the top three psychotherapies according to the mean SUCRA were behavioural therapy (s.m.d. = −0.78, 95% CI −1.14 to −0.42; SUCRA = 88%; CINeMA: moderate), CBT (s.m.d. = −0.67, 95% CI −0.95 to −0.39; SUCRA = 78%; CINeMA: moderate), short-term psychodynamic therapy (s.m.d. = −0.61, 95% CI −1.15 to −0.07; SUCRA = 71%; CINeMA: low) (reference: treatment as usual) (Figs 3 and 4; supplementary Appendix M). Cognitive therapy (s.m.d. = −0.47, 95% CI −0.86 to −0.09; SUCRA = 59%; CINeMA: low) was also found to be significantly more efficacious than treatment as usual in terms of panic symptom reduction. All the other psychotherapies (EMDR; interpersonal therapy; psychoeducation; physiological therapy; supportive therapy; third-wave CBT) showed no superiority over treatment as usual. Head-to-head comparisons showed behavioural therapy and CBT to be more effective than physiological therapies and third-wave CBT (Fig. 3).

Fig. 4 Forest plots comparing each psychotherapy with treatment as usual for efficacy and acceptability with the corresponding ranking probability (SUCRA) and certainty of evidence (GRADE), as assessed with the CINeMA appraisal, for each intervention.

SUCRA, surface under the cumulative ranking; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; CINeMA, Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis; BT, behavioural therapy; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; CT, cognitive therapy; EMDR, eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing; IPT, interpersonal therapy; PE, psychoeducation; PT, physiological therapy; SP, supportive therapy; STPD, short-term psychodynamic therapy; 3W, third-wave CBT; TAU, treatment as usual.

In terms of acceptability (96 RCTs, 6862 participants), cognitive therapy (RR = 2.36, 95% CI 1.43–3.87; SUCRA = 5%; CINeMA: high), behavioural therapy (RR = 1.89, 95% CI 1.24–2.88; SUCRA = 12%; CINeMA: high), and physiological therapy (RR = 1.49, 95% CI 1.03–2.16; SUCRA = 26%; CINeMA: high) proved to be significantly less acceptable than treatment as usual (Figs 3 and 4; supplementary Appendix N). All the other psychotherapies (CBT, EMDR; interpersonal therapy; psychoeducation; supportive therapy; short-term psychodynamic therapy; third-wave CBT) were as accepted as treatment as usual. Head-to-head comparisons showed cognitive therapy to be significantly less acceptable than third-wave CBT, supportive psychotherapy, short-term psychodynamic therapy, interpersonal therapy, EMDR and CBT. Behavioural therapy was significantly less accepted than short-term psychodynamic therapies, interpersonal therapies and CBT. Physiological therapy was less accepted than short-term psychodynamic therapy (Fig. 3).

For the efficacy analysis, relevant heterogeneity emerged from pairwise comparisons (i.e. I 2 ≤ 81.7%), and overall, the network showed significant heterogeneity (s.d. = 0.48; P < 0.01), but not inconsistency (P = 0.15). Intraloop inconsistency at the nominal P-value of 0.05 was found for 1 out of the 42 loops, a proportion to be expected empirically.Reference Veroniki, Vasiliadis, Higgins and Salanti168 For the acceptability analysis, no significant heterogeneity was detected for any of the pairwise comparisons and the network did not show significant overall heterogeneity (s.d. = 0.12; P = 0.31) or inconsistency (P = 0.88). The test for intraloop inconsistency reported no inconsistency in any of the 42 analysed loops. We observed only one slightly positive P-value (0.018, for the comparison ‘behavioural therapy versus CBT’) out of the 37 comparisons analysed in the side-splitting analysis of efficacy (supplementary Appendix M) and none among the 39 comparisons analysed in the side-splitting analysis of acceptability (supplementary Appendix N). Thus, for both outcomes there was good statistical agreement between all of the direct and indirect estimates as investigated using the side-splitting approach.

The results of the sensitivity analyses generally confirmed those of the primary analyses, but they suggested that studies at high risk of bias might have been responsible for a general inflation of efficacy effect sizes of psychotherapies and for some of the observed heterogeneity in the efficacy analysis (supplementary Appendix O, P, Q, R and S). After excluding studies that diagnosed participants by means of DSM-III or DSM-III-TR, short-term psychodynamic therapy lost its superiority over treatment as usual in terms of efficacy (supplementary Appendix M). Meta-regression analyses showed no covariate to act as an effect modifier (supplementary Appendix M). Supplementary Appendix T lists the differences between the original protocol and this report.

Discussion

Summary of the evidence

In this NMA, behavioural therapy, CBT, short-term psychodynamic therapy and cognitive therapy were superior to treatment as usual in the treatment of the acute phase of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia. At the same time, some of the most efficacious therapies were the lowest in terms of acceptability. For example, behavioural therapy had the best efficacy point estimate but proved to be poorly accepted, performing better than cognitive therapy only. In terms of efficacy, the psychotherapies that outperformed treatment as usual had medium-to-large effect sizes. Nonetheless, the CINeMA assessment showed very low-to-moderate confidence in the evidence, with no psychotherapy proving to have high quality of evidence. No relevant differences emerged when psychotherapies were compared head to head, except for behavioural therapy and CBT, which performed particularly well against physiological therapies and third-wave CBT. It should be acknowledged that although psychodynamic therapy has its own roots and tradition,Reference Freud169 the distinction between behavioural therapy, cognitive therapy and CBT is not clear-cut. For example, Clark's cognitive therapy for panic disorder emphasises the cognitive aspects, marginalising the role of fear extinction through habituation, but incorporates ‘behavioural experiments’.Reference Clark163,Reference Clark and Salkovskis170 By contrast, Beck's cognitive therapy also makes extensive use of behavioural skills.Reference Beck and Emery171 Finally, CBT is a psychotherapy that combines cognitive and behavioural elements.Reference Barlow172 It is therefore expected that CBT and its behavioural and cognitive components taken separately would have fairly similar effect sizes in terms of efficacy. Furthermore, our results on the efficacy estimates of psychotherapies for panic disorder are similar to those found for generalised anxiety disorderReference Chen, Huang, Hsu, Ouyang and Lin173 and social anxiety disorder,Reference Mayo-Wilson, Dias, Mavranezouli, Kew, Clark and Ades174 suggesting that common therapy factors might play a greater role than specific factors in the treatment of different anxiety disorders.Reference Cuijpers, Reijnders and Huibers175

For acceptability, most psychotherapies had similar effect sizes, but behavioural therapy and CBT were less acceptable than most of the other interventions. Furthermore, the evidence for cognitive therapy, behavioural therapy and physiological therapies was rated as high confidence, strengthening the link between efficacy and poor acceptability for behavioural and cognitive therapy. By principle, a high drop-out rate in psychotherapy trials does not necessarily mean that the intervention is poorly acceptable. In contrast with what happens in psychopharmacology trials, participants may drop out of psychotherapy not because of side-effects but because they get better and do not feel the necessity to be treated anymore. This could explain why some psychotherapies had large effect sizes but also high attrition rates. Nonetheless, among those studies reporting reasons for drop out such a possibility was never mentioned. Instead, the most frequently reported reasons for drop out were lost contact, personal or transportation difficulties and time demands. Regardless, only CBT and short-term psychodynamic therapy performed better than treatment as usual in terms of efficacy, being similar to the same reference comparison in terms of acceptability (although supported by only low-to-moderate confidence of evidence in both outcomes). In general, these results were confirmed by the sensitivity analyses, with the interesting finding that after removing high risk of bias RCTs the overall effect of psychotherapies deflated, and only CBT and behavioural therapy remained significantly more efficacious than treatment as usual. We acknowledge that sensitivity analyses showed a higher degree of incoherence in comparison with primary analyses. Such a finding may be due to the increase in the number of single-study comparisons present in the sensitivity analyses.Reference Veroniki, Vasiliadis, Higgins and Salanti176

The findings of the present systematic review and NMA are consistent with those from the randomised trials comparing psychotherapies head to head, and are also generally aligned with the results of previous pairwise meta-analyses. For example, Mitte et alReference Mitte177 found no differences between CBT and behavioural therapy in terms of anxiety reduction, and Sánchez-Meca et alReference Sánchez-Meca, Rosa-Alcázar, Marín-Martínez and Gómez-Conesa178 showed a general efficacy of psychological therapies for different clusters of symptoms, with the most consistent results in favour of the combination of exposure strategies with relaxation training or breathing retraining techniques, or both. There is also one Cochrane NMA on this topic, which was not able to provide clear-cut suggestions for clinical practice.Reference Pompoli, Furukawa, Imai, Tajika, Efthimiou and Salanti5 In the present review we almost doubled the number of included RCTs, sharpening the precision of the meta-analytic estimates especially for behavioural therapy and short-term psychodynamic therapy. For example, the Cochrane NMA called for new studies comparing CBT with short-term psychodynamic therapy,Reference Pompoli, Furukawa, Imai, Tajika, Efthimiou and Salanti5 and soon after its publication a relatively large RCT comparing short-term psychodynamic therapy with CBT was published.Reference Milrod, Chambless, Gallop, Busch, Schwalberg and McCarthy113 The results of this individual study are consistent with those of the present review, pointing out the slight superiority of CBT over panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy in terms of symptom reduction. We further confirmed these findings with the pairwise meta-analysis confronting CBT and short-term psychodynamic therapies head to head.

Strengths and limitations of this research

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest systematic review on the efficacy and acceptability of psychotherapies for a specific anxiety disorder. It compared psychotherapies for panic disorder using an NMA methodology that included all available psychotherapies, administered in any delivery format, while keeping in the network the contribution of studies that compared psychotherapies with pharmacotherapy to optimise the use of existing evidence. With some negligible exceptions, we were adherent to a protocol that we published in advance.Reference Papola, Ostuzzi, Gastaldon, Purgato, Del Giovane and Pompoli8 We selected one outcome measure for each study using a pre-planned hierarchy of rating scales, giving priority to panic-specific scales, aiming to enhance the clinical applicability of study findings. The inclusion of any type of delivery format is another strength, as focusing on one delivery format only would have excluded a relevant proportion of studies.

Despite these strengths, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the included RCTs were published over a long time span and this has inevitably introduced heterogeneity in terms of design, diagnostic criteria, follow-up periods and outcomes. To investigate this possibility we conducted meta-regression analyses to measure the potential impact of numerous study characteristics on the results, but we did not find significant associations. Heterogeneity could not be explained by the pre-planned sensitivity analyses either. We acknowledge this as the main limitation of the present study. The overall interpretation of the findings should be cautious owing to the presence of statistical heterogeneity in the efficacy analysis. When we removed the studies in which participants were diagnosed by means of outdated diagnostic manuals (i.e. DSM-III and DMS-III-TR), heterogeneity remained significant but short-term psychodynamic therapy lost its significance over treatment as usual. In light of the inconclusive finding of a meta-regression that tested the potential impact of the year of publication on treatment effect, such a result may be due to the loss of statistical power after removing oneReference Wiborg and Dahl155 of the five RCTs on short-term psychodynamic therapy.Reference Beutel, Scheurich, Knebel, Michal, Wiltink and Graf-Morgenstern39,Reference Martini, Rosso, Chiodelli, de Cori and Maina105,Reference Milrod, Chambless, Gallop, Busch, Schwalberg and McCarthy113,Reference Milrod, Leon, Busch, Rudden, Schwalberg and Clarkin114,Reference Wiborg and Dahl155 Despite that, the transitivity assumption appeared to be well preserved. In line with this point, we think the all-encompassing consideration of all the available delivery formats might explain at least part of the statistical heterogeneity detected in the efficacy analysis. Alhough there is evidence that different treatment delivery formats of CBT might have different impacts on depressive symptoms,Reference Cuijpers, Noma, Karyotaki, Cipriani and Furukawa179 no investigation has been conducted on the same matter for panic disorder so far. We highlighted that only 56% of the included RCTs used the individual face-to-face format, while the remaining 44% tested the validity of psychotherapies that used other delivery formats. A meta-regression analysis showed no impact of delivering the psychotherapy in person or remotely on the efficacy of psychotherapies. At any rate, in the second part of the overarching project described in the protocol,Reference Papola, Ostuzzi, Gastaldon, Purgato, Del Giovane and Pompoli8 we plan to deepen the topic by performing an NMA specifically focused on treatment delivery modalities for CBT. Second, more than half of the studies were judged to be at high risk of bias. We reason that this finding should be viewed also in light of meticulous requirements of the second version of the Cochrane risk of bias tool (RoB 2). Some of the key domains needed to grant a low risk of bias status are seldom satisfied in psychotherapy trials, especially those published before 2010. For example, the frequent failure to report details of allocation concealment, and the low rates of studies that analysed data in agreement with a pre-specified protocol, have negatively affected the overall risk of bias rating much more than would have happened applying the first version of the risk of bias tool. To counterweight the heavy impact of the risk of bias evaluation on the CINeMA evaluation we decided to downgrade by half a point for ‘some concerns’ and by one point for ‘major concerns’. This allowed us to produce a clinically informative open range of judgements instead of a less helpful series of very-low-confidence ratings, flattened down by the hypertrophic influence of the risk of bias evaluation. However, a sensitivity analysis showed that outcomes did not change indicatively after removing high risk of bias studies. Third, the imbalance in terms of number of participants between CBT and the other psychotherapies might have affected the reliability of our findings owing to random errors brought into the networks by the nodes with fewer participants (cognitive therapy, behavioural therapy, psychodynamic therapy, physiological therapy) and especially by those with fewer than 100 participants (interpersonal therapy, EMDR, third-wave CBT, psychoeducation, supportive therapy, benzodiazepines). Fourth, only three direct comparisons included ten or more studies, so the risk of publication bias could not be checked for the great majority of the head-to-head comparisons. The only comparison for which a small-study effect was suspected was CBT versus treatment as usual, which was one of the key comparisons in the efficacy analysis. Although there is the possibility that the SUCRA ranking of CBT could be partly explained by a small-study effect, such a suspicion arose from the analysis of 12 RCTs only. This number is just above the threshold suggested for analysing publication bias.Reference Sterne, Sutton, Ioannidis, Terrin, Jones and Lau20 Thus, the output of the Egger's regression test (P < 0.05) should not be considered probative, and a small-study effect may be only suspected. Furthermore, the possibility that the efficacy of CBT over treatment as usual could be influenced by a small-study effect was taken into account in the CINeMa appraisal. Fifth, studies comparing psychotropic drugs head to head or against placebo were not searched, so this review cannot be informative on the efficacy and acceptability of antidepressants and benzodiazepines for panic disorder. We reasoned that studies allocating participants to pharmacotherapy versus placebo, without a psychotherapy arm, might substantially differ from studies with a psychotherapy arm, with a high risk of violating the transitivity assumption required for an NMA.Reference Salanti, Del Giovane, Chaimani, Caldwell and Higgins180,Reference Del Giovane, Cortese and Cipriani181 Sixth, most studies did not include patients with comorbid disorders, which might alter the external validity of the results. Last, the NMA approach is not free from technical and theoretical shortcomings, including risks of multiple statistical assumptions and the challenges in addressing the problem of intransitivity and inconsistency.Reference Cipriani, Higgins, Geddes and Salanti182

Clinical and research implications

Shedding light on the most appropriate psychotherapies in terms of risk/benefit ratio is a priority that could reduce use of pharmacological strategies and discourage recourse to interventions not backed by a sufficient evidence base.Reference Lilienfeld183 The finding that CBT and short-term psychodynamic therapy may be regarded as reasonable first-line psychotherapies in the acute phase of panic disorder has clinical implications. In line with recommendations from current guidelines,184–187 the present review strengthens the evidence base on the efficacy of CBT, as we found moderate quality of evidence pointing out that CBT has nearly 80% probability of being the best treatment available for panic disorder based on the SUCRA ranking convention. CBT ranked second to behavioural therapy, and the credibility of evidence for the efficacy of behavioural therapy was equal to that for CBT. Nonetheless, we found high confidence of evidence of the low acceptability of behavioural therapy compared with treatment as usual. The findings of the present review confirm the growing trend in favour of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapies as reliable first-line interventions for panic disorderReference Pompoli, Furukawa, Imai, Tajika, Efthimiou and Salanti5 and in general for common mental disorders.Reference Abbass, Kisely, Town, Leichsenring, Driessen and De Maat188 Trials on manualised psychodynamic psychotherapy delivered short-term and relatively inexpensive interventions that are easily implemented after an adequate training.

Large, pragmatic and high-quality head-to-head studies comparing psychotherapies other than CBT are needed to overcome the paucity of evidence for some interventions and to test therapy working mechanisms, patient-defined outcomes and cost-effectiveness.Reference Cuijpers189,Reference Cuijpers190 As part of the results of this review, we abstracted information on the main characteristics, delivery modalities and reference manuals for each psychotherapy intervention, thus enhancing the understanding of treatment complexity, mechanism of actions and active ingredients of each therapy. This information will likely be beneficial to developers to inform updates to international and national guidelines from scientific organisations, to researchers planning future investigations and to practising clinicians for the ultimate goal of improving mental healthcare.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.148.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Per Carlbring, David Clark, Anna Lucia Spear King, Diana Koszycki, Alicia Meuret, Katharina Meyerbroeker, Barbara Milrod, John R. Keefe and Peter Roy-Byrne for providing unpublished data from RCTs they conducted that are included in this systematic review and network meta-analysis.

Author contributions

D.Pap., P.C. and C.B. conceived the study. D.Pap., C.G., G.O., E.K., M.S., P.C., A.P., D.Pau. and M.P. assessed the eligibility of the studies for inclusion, extracted data and assessed risk of bias. D.Pap., G.O., F.T., T.A.F., C.D.G. and C.B. designed and performed the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings. D.Pap. drafted the manuscript, to which all authors contributed. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

T.A.F. reports personal fees from Mitsubishi-Tanabe, MSD and Shionogi, and a grant from Mitsubishi-Tanabe, outside the submitted work. E.K. and P.C. are members of BJPsych editorial board and did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this paper.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.