Introduction

Voters are frustrated by the influence of money in politics (Klašnja, Tucker, and Deegan-Krause Reference Klašnja, Tucker and Deegan-Krause2016) and disapprove of corrupt politicians (Agerberg Reference Agerberg2020). They are afraid that politicians do not act in their interest (Kaina Reference Kaina2008; Newton, Stolle and Zmerli Reference Newton, Stolle and Zmerli2018) but in the interest of actors who provide them with an additional income. Hence, it is not surprising that members of parliament (MPs) who accumulate personal financial benefits while in office – even legally – face reduced levels of trust from voters (Cohen, Noh and Zechmeister Reference Cohen, Noh and Zechmeister2025; Rose and Wessels Reference Rose and Wessels2018) (however, for a contrasting finding, see Kelly and Tilley Reference Kelly and Tilley2024). In the aggregate, this may also pose a challenge to the legitimacy of representative democracy. One possibility to counteract the growing mistrust and discontent toward politicians is the disclosure of side income. Since trust in politicians and political institutions has been found to change with the availability of additional information (Alessandro et al. Reference Alessandro, Lagomarsino, Scartascini, Streb and Torrealday2021; Morisi and Wagner Reference Morisi and Wagner2020; Porumbescu Reference Porumbescu2015), disclosure of MPs’ income from side jobs has been portrayed as a key trust-building measure vis-à-vis the electorate (Geys and Mause Reference Geys and Mause2012). Trust toward politicians, in turn, fosters political legitimacy – a cornerstone of functioning democracies.

Transparency has been heralded as a mechanism to increase accountability, improve decision-making quality, and curb corruption (Bauhr and Grimes Reference Bauhr and Grimes2014), also for members of national parliaments. In almost all European countries, for example, citizens nowadays have at least access to information about the existence of MPs’ remunerated extra-parliamentary activities, e.g., the names of MPs’ employers (Huwyler Reference Huwyler2024). Only some of those, however, have extended transparency to (exact) incomes per side job. It is, therefore, still crucial to address the question of whether parliamentary side income transparency induces trust in politicians.

In fact, previous studies have shown that transparency may also fall short of its intended goals (Grimmelikhuijsen Reference Grimmelikhuijsen2012; Pedersen, Dahlgaard and Pedersen Reference Pedersen, Dahlgaard and Pedersen2019) and even exert a negative effect on trust (Grimmelikhuijsen et al. Reference Grimmelikhuijsen, Porumbescu, Hong and Im2013); possibly because voters are generally suspicious toward politicians’ salaries and raises thereof (Pedersen, Hansen and Pedersen Reference Pedersen, Hansen and Pedersen2022). Our knowledge so far has remained limited to how voters perceive different types of moonlighting behavior in scenarios where MPs’ side income is known to them (Campbell and Cowley Reference Campbell and Cowley2015). In this study, we therefore take a step back to analyze whether income transparency improves voters’ perceptions of their representatives. Moreover, we distinguish between different interest groups to understand whether undisclosed payments by companies lower trust more than those by public interest groups. This enables us to gain a deeper understanding of citizens’ views on transparency but also on the different sources of parliamentarians’ incomes.

Based on a pre-registeredFootnote 1 large-scale survey experiment conducted in seven European countries, we find that parliamentarians can enhance their trustworthiness and electability by choosing to disclose their side income rather than objecting based on privacy concerns. Even if disclosure reveals a particularly high amount of additional income (150 percent of the parliamentary salary), respondents still consider those MPs more trustworthy and electable than nontransparent ones. Furthermore, the results suggest that voters infer side income levels of nontransparent parliamentarians based on the number and type of side jobs, penalizing those with a high number of ties to companies the most. In sum, our robust empirical findings across all seven countries suggest a clear trust-building effect: transparency on financial ties to other actors pays off for politicians.

Perceptions of MPs’ side income and its sources

Voters are meant to be the ultimate principals of parliamentarians, and MPs are their agents who represent their interests (Strøm Reference Strøm2000). For the principal-agent relationship to work, voters must be assured that MPs act and react in accordance with their promises and pledges. However, as we know, voters may suffer from agency losses when legislators act in their own interest or adhere to other audiences, including interest groups whose preferences may not always be congruent with voters’ (Giger and Klüver Reference Giger and Klüver2016). Interest groups and MPs often maintain transactional relationships where parliamentarians have paid roles in interest group bodies. The former’s financial investment in MPs can be perceived as an expression of the strength of these formal ties.

Citizens care about linkages between interest groups and their representatives since they fear competition with additional principals who also seek representation of their interests but can, in contrast to voters, offer monetary incentives. Previous research indeed shows that interest groups affect MPs’ parliamentary behavior in accordance with interest groups’ preferences (Giger and Klüver Reference Giger and Klüver2016; Huwyler, Turner-Zwinkels and Bailer Reference Huwyler, Turner-Zwinkels and Bailer2023; Weschle Reference Weschle2024). Accordingly, it matters how strongly – with what financial resources – interest groups affect parliamentarians’ behavior and possibly distract them from representing voters (see Carey Reference Carey2007). Thus, concealing such information entails potential pitfalls: if financing of politicians is nontransparent, citizens are weakened in their ability to assess the legitimacy of their income (Geys and Mause Reference Geys, Mause, Karsten and Andreas2023). They become dissatisfied with political processes and lose trust (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002). This, in turn, erodes their belief in the political system (Anderson and Tverdova Reference Anderson and Tverdova2003; Seligson Reference Seligson2002).

The effect of income (non-)transparency

There is a broad scientific consensus that voters view secrecy about money in politics critically as a whole. This holds, unsurprisingly, when flows of money are not only clandestine but also illegal. Several studies have corroborated that voters care about corruption (Palau and Davesa Reference Palau and Davesa2013) and punish corrupt politicians (Costas-Pérez, Solé-Ollé and Sorribas-Navarro Reference Costas-Pérez, Solé-Ollé and Sorribas-Navarro2012; Ferraz and Finan Reference Ferraz and Finan2008), notably when voters are more sophisticated (Weitz-Shapiro and Winters Reference Weitz-Shapiro and Winters2017). Importantly, though, the public is also critical of legal forms of secret money flows. Research on campaign financing demonstrates that donations to campaign accounts without source disclosure erode voters’ trust in institutions (Sances Reference Sances2013, 65). Candidates, in turn, are electorally punished for their lack of campaign finance transparency (Wood Reference Wood2023). Voters have also been found to care about the income of political candidates (Campbell and Cowley Reference Campbell and Cowley2014) and react to the amount of side income that incumbent parliamentarians earn (Campbell and Cowley Reference Campbell and Cowley2015).

In parallel to the scientific attention, concern has also grown among political decision-makers. During the 2010s, law-makers introduced more diverse conflict of interest regimes for MPs in many democracies (Bolleyer et al. Reference Bolleyer, Smirnova, Mascio and Natalini2020). A prominent element among these regulations is transparency as a means of reducing corruption and strengthening political accountability (Holman and Luneburg Reference Holman and Luneburg2012). Disclosure of MPs’ side income is a key element in the transparency architecture. Governments hope that financial disclosure rules for politicians and parties increase trust and decrease voters’ frustration with politics (Weschle Reference Weschle2016). Several studies have grappled with the expectations that transparency has raised in the eyes of the public. They could show that more transparency positively affects the public’s perception of political decision-making processes and outcomes (Fine Licht Reference Fine Licht2014), policy-makers’ perceived responsiveness (Cicatiello, De Simone and Gaeta Reference Cicatiello, Simone and Lucio Gaeta2016), and their perceived truthfulness and care for voters (Grimmelikhuijsen Reference Grimmelikhuijsen2009).

Based on these considerations, we posit that disclosure of MPs’ extra-parliamentary income strengthens the representative link between the electorate and the elected. We expect voters to react positively when MPs show willingness to disclose their income, as the availability of side income information permits them to develop a better picture of MPs’ interests and foci.

Hypothesis 1 Voters will assess transparent parliamentarians, i.e., those whose side income is disclosed more positively (trustworthy and electable) than nontransparent ones.

The effect of income-related cues

Voters will not always know MPs’ (exact) side income, as this can be exempt from disclosure. However, in many cases, they will have access to information on MPs’ affiliations to interest groups – not least when the media and civil society take an interest in the topic. Relevant information is often published by parliaments or government ministries under transparency regimes, or is available in other public sources such as commercial registers. MPs and interest groups may also advertise information on their collaboration themselves. While parliamentarians emphasize their interest group affiliations for electoral purposes (Lutz, Mach, and Primavesi Reference Lutz, Mach and Primavesi2018), some interest groups exploit MPs working for them as a signal of their political connectedness to members, donors, investors, partners, and the public (Niessen and Ruenzi Reference Niessen and Ruenzi2010).

Thus, voters will often know about their representatives’ ties to interest groups but lack knowledge about the strength of these linkages – for which income would provide some indication. In the absence of side income disclosure, we posit that the type of extra-parliamentary activity – for whom MPs work next to their mandate – offers voters a cue as to the expected amount of income. This is similar to professions that serve as a cue for politicians’ qualifications (McDermott Reference McDermott2005). In our study, we focus on ties to public interest groups with charitable and humanitarian missionsFootnote 2 – they are archetypal signals of low or no sideline income, and ties to companies as cues for high sideline income, respectively.

When MPs are affiliated with public interest groups, they are typically seen as advocating for public goods that benefit the broader population or championing the interests of marginalized societal groups. Such ties can function as a strong signal to voters, as they convey a commitment based on moral principles and ideational motivation, rather than material self-interest (e.g., Huwyler and Turner-Zwinkels Reference Huwyler and Turner-Zwinkels2020). Consequently, public expectations exert a downward pressure on wages paid by these organizations (see Hirsch et al., Reference Hirsch, Macpherson and Preston2018). Public interest groups have little incentive to foster the notion that their funds are being used for the personal gain of politicians rather than to advance the charitable and humanitarian missions of their organizations – an impression that could undermine the credibility of both the politician and the interest group. In line with this logic, we expect that voters generally associate MPs’ ties to public interest groups with minimal or no supplementary income in the absence of income disclosure.

By contrast, we expect voters to infer higher undisclosed side income when MPs work for companies. Parliamentarians’ affiliations to narrow, sector-specific business interests, especially companies, are likely to be interpreted as moonlighting driven by personal financial – not electoral – motives (Huwyler and Turner-Zwinkels Reference Huwyler and Turner-Zwinkels2020). Accordingly, we argue that voters assume a higher undisclosed income from sideline jobs with companies than with public interest groups, and evaluate MPs accordingly when they are unwilling to reveal income information.

Hypothesis 2 Voters will assess nontransparent parliamentarians working for public interest groups more positively (trustworthy and electable) than those working for companies.

The second type of cue to voters is the number of side jobs MPs have. A higher number of interest group jobs can be interpreted as a proxy for more side income. Voters fear that MPs who are engaged in more interest group work are less capable of representing their interests than those parliamentarians who do not moonlight. This may be justified since there is, for one, the danger of slacking when MPs do not work as expected for their voters. Previous research on moonlighting behavior has shown that higher outside earnings of parliamentarians – a crude measure for activities spent not on matters related to the elected office – translates to less legislative output (fewer oral contributions, interpellations, initiatives, and reports) (Arnold, Kauder and Potrafke Reference Arnold, Kauder and Potrafke2014; Staat and Kuehnhanss Reference Staat and Kuehnhanss2017). At the same time, there is the threat of MPs shirking, as they spend less effort on representing voters’ interests. More interest group affiliations in a certain policy area have been linked to MPs focusing their parliamentary activity more strongly on said area (Huwyler, Turner-Zwinkels and Bailer Reference Huwyler, Turner-Zwinkels and Bailer2023). Accordingly, we expect voters to be skeptical of nontransparent MPs with more interest group jobs.

Hypothesis 2b Voters will assess nontransparent parliamentarians working for fewer interest groups more positively (trustworthy and electable) than those working for more.

The core of our argument is that both the type and the number of interest groups serve as heuristics for voters to infer nontransparent MPs’ sideline income. However, as mentioned earlier, these cues may also convey additional information. Specifically, the type of interest group – public interest group or company – can signal whether an MP’s sideline activities are motivated by a commitment to serving the public good or by personal financial gain. Prior research suggests that voters view public interest groups as more representative of society than narrow business interests (Rasmussen and Reher Reference Rasmussen and Reher2023). If interest group type solely functions as a cue for the amount of side income, its effect on voter perceptions should disappear once income is disclosed. Similarly, when income transparency is present, the number of interest group ties should no longer serve as a cue for extra-parliamentary earnings. If voters interpret the number of ties purely as an indicator of side income and not as a signal of divided attention or reduced commitment to parliamentary work, we should observe no effect of this cue once side earnings are made explicit.

To assess whether these income-related cues convey meaning to voters beyond side earnings, we examine their effects under conditions of income transparency, as specified in H2a and H2b. This allows us to evaluate whether such cues are merely interpreted as indicators of additional earnings, or if they function as independent signals that shape voter perceptions in their own right.

Hypothesis 3a: Voters will assess transparent politicians working for public interest groups more positively (trustworthy and electable) than those working for companies.

Hypothesis 3b: Voters will assess transparent politicians working for fewer interest groups more positively (trustworthy and electable) than those working for more.

Experimental design and data

We test our theoretical expectations with data from a large-scale citizen survey conducted in 2021 in seven European countries (Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom). Figure 1 illustrates the state of income disclosure regimes for MPs as of 2023. With the exception of France, which prohibits MPs from engaging in paid work for interest groups, the selected cases reflect broader European patterns of transparency in the regulation of parliamentarians’ collaboration with interest groups. Across the seven selected countries, disclosure requirements range from reporting paid interest group affiliations without income information in Switzerland, to reporting income in pre-defined categories per position in Belgium and Germany (at the time of the survey), to full disclosure of exact income amounts per position in the Netherlands, Poland, and the United Kingdom. At the same time, the selected cases also reflect the fact that almost all European countries require MPs to disclose their unpaid affiliations with interest groups.Footnote 3

Figure 1. Disclosure rules for MPs’ interest group work in 35 European countries in 2023.

Notes: The figure reflects regulations specifically targeting MPs (from the lower parliamentary chamber, if bicameral) as of early 2023. It does not reflect that tax returns are generally public in Sweden and Norway. At the time of the survey in 2021, Germany required only disclosure of income per position in categories. Source: Huwyler Reference Huwyler2024.

Voters’ attitudes toward parliamentarians’ income transparency were gauged with a module incorporated in an omnibus survey.Footnote 4 The number of respondents per country was set to around 2,000, giving us more than 14,100 complete observations. The sample uses quotas on age, gender, and education.

In our module, we use a single-vignette experiment that focuses on the side income transparency of (fictitious) parliamentarians in (real) national parliaments. We measure respondents’ reaction to a Tweet that entails a politician commenting on the latest release by the Transparency Observatory, a fictitious advocacy group that lists politicians’ interest group affiliations and provides a rating on their income transparency regarding these affiliations. In doing so, we present a realistic treatment, as in the majority of our countries (as well as in the EU), NGOs monitor MPs’ lobbying activities.Footnote 5 Our setup comes with the advantage that unrealistic or uncommon configurations in which, for example, nontransparent MPs advertise their non-disclosure on their own initiative are avoided. It also alleviates ethical concerns, as using real people and organizations would be problematic, especially if we portrayed them in a critical light.

Twelve different vignettes are used, with each being randomly displayed to one twelfth of the respondents. Each respondent is shown only one vignette. All vignettes consist of a single fictitious Tweet posted by a fictitious parliamentarian. In those Tweets, a national MP (lower house, if bicameral) from the respondent’s country posts a screenshot from the website of the Transparency Observatory. In the Tweet text that accompanies the screenshot, the parliamentarian reacts to the fact that the Transparency Observatory has created a profile of them on its website. This profile contains information on the MP’s board seats in fictitious interest groups.Footnote 6 The information that the Transparency Observatory reveals on the MP differs between Tweets: parliamentarians are shown to react either favorably (when their side income is known and they receive an A rating) or unfavorably in their post (when they object to income disclosure and receive an E rating).Footnote 7 Figure 2 depicts two examples.

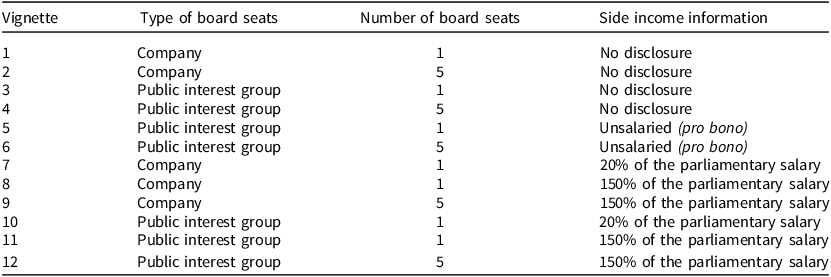

The Tweets vary on three key dimensions. First, the parliamentarian is affiliated with either companies or public interest groups. This distinction represents ideational or financial goals that MPs pursue with side jobs. Second, the parliamentarian has either one or five seats in organizations, which aims to suggest, at least by proxy, that the MP does either little or a lot of extra-parliamentary work. Third, remuneration from these roles is either zero (pro bono work), remunerated at 20 percent of the parliamentary salary, remunerated at 150 percent of the parliamentary salary, or not disclosed (nontransparent). This dimension encapsulates the key distinction between income disclosure and non-disclosure. For transparent MPs, there are three different levels of income. Pro bono work represents, again, ideational motivation. Side income in the amount of 20 percent of the parliamentary salary was chosen as a comparatively modest supplement to the parliamentary salary. In contrast, 150 percent of the parliamentary salary as additional income represents moonlighting for financial motives. It indicates exceptionally high side income, where it is unclear whether transparency or non-transparency serves MPs better. For example, only 2.6 percent of all German MPs have side income that comes close to or surpasses their parliamentary salary (Mai Reference Mai2022). Our high-income category is therefore representative of a very small group of exceptionally successful moonlighters and constitutes thus a hard test for finding positive effects of transparency. By way of comparison, a pioneering survey experiment on moonlighting British MPs fielded in spring 2013 used £10,000 (15 percent of the parliamentary salary at the time) and £50,000 (75 percent of the parliamentary salary at the time) as treatments (Campbell and Cowley Reference Campbell and Cowley2015). In addition, our vignettes also differ as to the gender of the fictitious parliamentarian. Importantly, though, in line with the approach of Campbell and Cowley (Reference Campbell and Cowley2015), we opted not to include any party cues to avoid additional complexity. Table 1 provides an overview of the theoretically relevant variation in the vignettes.

Table 1. Vignette composition

Notes: There is a female and male version of each vignette.

Information from the vignettes is complemented by respondents’ evaluations of the politician. After being shown one of the vignettes at random, they were asked how they assess the MP’s trustworthiness on a scale from 0 to 10 and whether they can imagine voting for them on a scale from 0 to 10 (electability). These two concepts represent a more diffuse and a more concrete form of respondents’ approval of the parliamentarian. In the last step, respondents were subject to a manipulation check. They had to remember whether the parliamentarian was transparent regarding their additional income (yes, no), and how many board seats the MP had (1, 2–3, 4–5, 6, or more).Footnote 8 Further data on sociodemographics (gender, age, education, income, ideology, and country) were collected in other parts of the survey. Table A3 in the online appendix shows a descriptive overview of the variables used in this study.

The chosen experimental design has several advantages. Presenting information in a visually appealing way reflects recent debates in the discipline that surveys should be more pleasant to answer (Druckman Reference Druckman2022; Salganik Reference Salganik2019). The social media scenario realistically resembles how citizens encounter information about politicians nowadays and thus speaks for the external validity of the experiment. Previous studies have repeatedly shown that citizens react to different social media styles of politicians, e.g., when they interact with citizens’ posts (Bright et al. Reference Bright, Hale, Ganesh, Bulovsky, Margetts and Howard2020; Lee and Shin Reference Lee and Yun Shin2012), tweet more positively (Gerbaudo, Marogna and Alzetta Reference Gerbaudo, Marogna and Alzetta2019), or include policy rather than private content (Giger et al. Reference Giger, Bailer, Sutter and Turner-Zwinkels2021).

The fact that the parliamentarian in the vignette reacts to the rating strengthens the link between them and the information about their interest group affiliations. It enables us to present the information on sideline jobs and income transparency in an easy, realistic, yet personalized frame. The MP either presents their positive transparency rating or objects to the disclosure of income information on grounds of privacy, an argument that MPs have invoked in actuality to oppose income disclosure. We consider it realistic that politicians nowadays come forward with such information themselves, so as not to cede control of it to political opponents or critical journalists. Privacy is a well-known counterargument to the disclosure of MPs’ sideline income. For instance, on 28 May 2024, Swiss MP Daniel Jositsch invoked the privacy argument during the parliamentary debate on Bill 22.485, which aimed to make income disclosure for side jobs mandatory. He said that:

‘I shouldn’t have to strip down to my underwear, so to speak, just because I’m a member of this parliament. As an MP, I also have the right to do what I want outside of my parliamentary activities – within the law, of course – without having to show everything’. Footnote 9

Importantly, our approach entails a caveat. Because we combine income disclosure status with the MP’s justification for (non-)disclosure, we cannot rule out a potential confounding effect. Specifically, the MP’s transparency status (0/1) is perfectly correlated with their appeal to the right to privacy (0/1). As a result, the effects of these two treatments cannot be disentangled. However, previous research leads us to assume that including a reason for non-disclosure – in our case, the MP’s privacy concerns – will positively influence citizens’ view of the nontransparent politician. Principled justifications improve citizens’ evaluations of politicians who make controversial decisions (McGraw, Timpone and Bruck Reference McGraw, Timpone and Bruck1993). In contrast, the vignettes with the transparent MP do not include any reason in favor of transparency. The justification of non-disclosure should make it more difficult to detect differences between nontransparent and transparent vignettes.Footnote 10

Moreover, income disclosure regimes vary between different institutional venues within the same country. In our experiment, respondents’ evaluations of the vignette are tethered to a clearly defined real-life political context. Importantly, attitudes toward transparency can be affected by contextual factors such as cultural values (Grimmelikhuijsen et al. Reference Grimmelikhuijsen, Porumbescu, Hong and Im2013). By conducting our survey experiment in seven different countries, we aim to provide a high degree of external validity to our findings.

Lastly, single-vignette experiments are comparatively unlikely to overestimate the expected effects. In contrast to designs that use paired and/or multiple vignettes, there is a lower risk for social desirability driven by anchoring (Krzyzowski and Nowicka Reference Krzyzowski and Nowicka2021). At the same time, though, our between-subject design does not allow us to determine whether an individual respondent’s assessment was biased by certain aspects of the vignette (Walzenbach Reference Walzenbach2019, 106), as each respondent evaluated only one scenario. Nonetheless, statistical evidence suggests that single-vignette experiments rather underestimate effect magnitudes in comparison to citizens’ real-world behavior (Hainmueller, Hangartner and Yamamoto Reference Hainmueller, Hangartner and Yamamoto2015).

Analytical strategy

To address our research questions and hypotheses, we first analyze average marginal effects to investigate how (non-)disclosure of side income shapes voters’ perceptions of MPs, and what role different cues play. The underlying models include socio-demographics and left-right self-placement of respondents, as well as country fixed effects. This allows us to go beyond the key effects of our vignette attributes and control for respondents’ characteristics to obtain more precise estimates of our treatment effects (Druckman, Greene and Kuklinski Reference Druckman, Greene and Kuklinski2011). Second, we inspect whether our key patterns hold across different groups of respondents or whether broad trends mask more nuanced attitudes. To that end, we explore interaction effects between the transparency treatment and respondents’ income, education level, and ideology.

Our analyses are complemented by a series of robustness tests that we report in the online appendix. We first address design imbalances in the experiment that stem from the exclusion of vignettes featuring implausible combinations of attribute levels. Out of 16 theoretically possible vignette combinations, 12 were included in the study. The four excluded combinations raised concerns about realism, i.e., an MP working pro bono for companies or holding five board seats while earning only 20 percent of their parliamentary salary as side income. Based on models that include individual vignettes as predictors (Table A4) and an inspection of marginal effects (Figure A16), we demonstrate that excluding these vignettes does not drive our main results. Crucially, across all eight combinations of interest group types (public interest group vs. company) and number of board seats (1 vs. 5), we find that nontransparent MPs are rated significantly lower in trustworthiness and electability compared to their transparent counterparts with the same number and type of interest groups who earn 150 percent of their parliamentary salary in side income. Moreover, Table A5 demonstrates that respondents’ assignment to the key treatment condition (transparency status) is independent of their characteristics.

Another potential concern involves confounding effects from unmeasured latent treatments in our vignettes (Fong and Grimmer Reference Fong and Grimmer2023). Specifically, the interest groups presented in the vignettes may have acted as cues in unintended ways. First, respondents were not informed about the politician’s party affiliation. However, since parliamentarians’ sideline jobs in interest groups follow ideological lines (e.g., Huwyler and Turner-Zwinkels Reference Huwyler and Turner-Zwinkels2020), it is plausible that respondents inferred left-wing affiliation from involvement in public interest groups and center-right affiliation from seats on company boards. However, Figure A23 and Table A29 show that respondents’ reactions to public interest group versus company board cues are not conditioned by their own ideological orientation. This suggests that the type of interest groups does not serve as a proxy for ideology. Second, we assess whether different types of interest groups function as signals of issue prioritization – specifically, humanitarian versus economic concerns. To do so, we examine whether respondents’ evaluations are shaped by the perceived importance of two issues: climate change as a proxy for alignment with public interest groups and unemployment as a proxy for alignment with companies. In Figure A24 and Table A30, we find no evidence to support this assumption.

As a robustness test, we show in Figure A21, Table A16, and Tables A18 through A24 that our overall patterns replicate across countries and separately for each country, regardless of their different electoral contexts and transparency regimes. In particular, our established patterns also hold for France (Tables A17 and A19). The French parliament is the only one in our sample where paid sideline jobs are banned – and our experimental scenario is thus counterfactual to respondents in France. As our overview of income disclosure regimes in Table 1 indicates, parliamentary side job disclosure ranges from no income disclosure to exact amounts in the six remaining countries. Beyond country variation, we also inspected additional differences at the respondent level. Figure A22 and Table A26 indicate that respondents’ Twitter use does not drive our overall patterns. Figure A20 and Table A15 suggest that citizens’ views of income transparency do not depend on whether MPs are affiliated with companies or public interest groups.

Furthermore, we also explore patterned effects based on more basic sociodemographics: MPs’ gender (Figure A17 and Table A12), respondents’ gender (Figure A18 and Table A13), and respondents’ age (Figure A19 and Table A14). We additionally investigate the patterns of respondents not picking up on our transparency treatment in Table A27 and demonstrate that keeping only attentive respondents in the sample increases the effect sizes of the vignette characteristics in the expected direction (Table A28).

Results

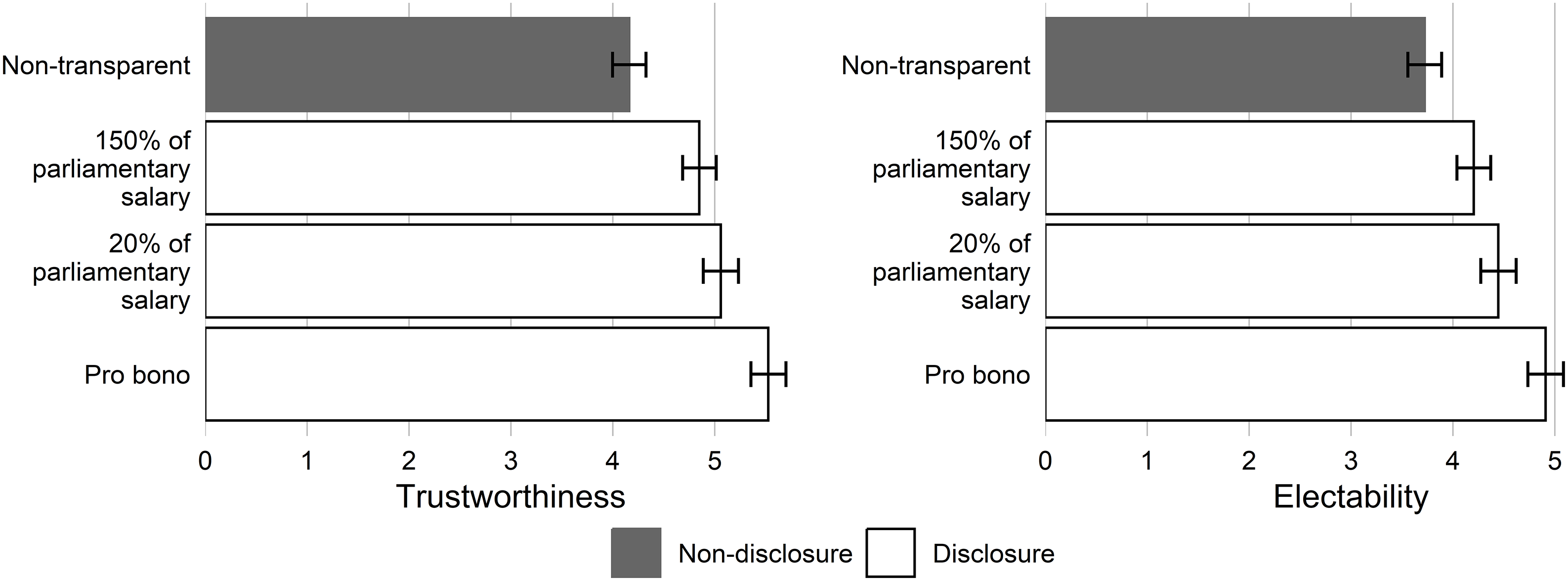

Citizens value transparency: our results reveal a pronounced divide in how respondents evaluate MPs based on whether they provide information on their side income. Figure 3 displays the average marginal effects of side income (non-)disclosure on voters’ perceptions of MPs’ trustworthiness and electability, measured on a 0 to 10 scale. The patterns indicate that transparency consistently improves voters’ perceptions. Even when MPs disclose that their side income amounts to 150 percent of their parliamentary salary, their trustworthiness increases by 0.69 units, and their electability by 0.48 units, compared to MPs who do not disclose any side income information.

Figure 3. Perceptions of MPs’ side income transparency.

Notes: Bars denote the predicted values, and error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals. The underlying models are reported in Table A6.

Importantly, the specific amount of disclosed income plays a relatively minor role. MPs who report more modest sideline earnings, i.e., 20 percent of their parliamentary salary, are viewed somewhat more favorably than those earning 150 percent. However, these differences are not statistically significant. This suggests that voters primarily reward the act of disclosure itself rather than strongly differentiating based on the magnitude of outside earnings. Nevertheless, income transparency has the strongest positive effect when it reveals the absence of paid sideline jobs. MPs with only pro bono jobs have, on average, trustworthiness scores that are 1.36 units higher and electability scores that are 1.19 units higher than nontransparent ones. Overall, our evidence therefore indicates that voters distinguish between three types of politicians – those who are nontransparent, those who disclose any amount of side income, and those who have no side income to disclose – and evaluate them accordingly.

Voters do not always have access to information about the remuneration of MPs’ side jobs. In such cases, they must rely on alternative cues to assess an MP’s trustworthiness and electability. The top row of Figure 4 uses average marginal effects to illustrate whether respondents rely on the type of organization (i.e., company vs. public interest group) and the number of board seats as heuristics when income information is absent. The findings partially support the assumption that voters penalize nontransparent politicians more when they serve on more interest group boards or work for companies. The profile is arguably most suggestive of substantial undisclosed income – an MP holding five corporate board positions – receives the lowest ratings for both trustworthiness (3.71) and electability (3.27). However, the negative effect of multiple board roles appears limited to company affiliations. For more public interest group seats, in contrast, a weakly positive pattern emerges: MPs with five public interest group board seats are viewed slightly (non-significantly) more favorably than those with only one. The clearest contrast in voter perceptions hence occurs between MPs holding five company board roles and those with five public interest group seats, whereas there is little to no difference between MPs with a single board seat in either context. These results therefore suggest that a higher number of board seats shapes voter perceptions, but only through interaction with interest group type.

Figure 4. Voters’ use of interest group cues with and without income transparency.

Notes: Bars denote the predicted values, and error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals. The underlying models are reported in Table A6. They are based on the eight nontransparent and the eight 150% side income vignettes.

The bottom row of Figure 4 reveals how these cues function in the context of side income transparency. We focus on vignettes in which MPs disclose earnings amounting to 150% of their parliamentary salary, as each of these has a directly corresponding nontransparent version. This setup allows for a clean comparison based on a balanced design.Footnote 11 Our results show that once MPs disclose their side income, voters’ evaluations become largely independent of the number and type of board seats. The cues that previously shaped voters’ perceptions in the absence of transparency – most notably the pronounced negative effect of holding five company board seats – no longer affect assessments of trustworthiness and electability. This suggests that the cue effects observed in the nontransparent condition were primarily influenced by voters’ assumptions about undisclosed side income, and hence largely neutralized when MPs disclose their side income.

While our previous results showed patterns among all citizens, the final step is an exploratory analysis of how differences in citizens’ backgrounds affect their perceptions.Footnote 12 Figure 5 displays predicted values of trustworthiness and electability based on interaction effects between MPs’ disclosure status and respondents’ income (row 1), education level (row 2), and ideology (row 3). This exploratory inspection of different groups of respondents shows that, by and large, the previously established patterns – transparent MPs are more positively assessed than nontransparent ones and more side income is viewed more critically – hold. As the earlier results have already established, voters are less attuned to discrepancies between low and high side income-earning MPs than to differences between MPs with no and any side income. There are, moreover, nuances in how strongly different groups react to non-transparency and side income differences.

There is a tendency for respondents with higher socio-economic status to exhibit a more pronounced ability to differentiate between nontransparent and transparent MPs. The first two rows of Figure 5 highlight that the most highly educated and well-earning respondents hold the most favorable views of MPs who do only voluntary work. At the same time, they also dislike nontransparent MPs most strongly. For the other two transparent categories – MPs earning 150 percent and 20 percent of their parliamentary salary additionally – the patterns are less clear. There is the tendency that MPs with 20 percent side income, and to a weak extent also those with 150 percent additional earnings, are more positively assessed by better educated and higher earning respondents. These patterns suggest that nuanced perceptions of MPs’ (non-)transparency and side incomes depend on voters’ level of information, skills (education) – similar to Weitz-Shapiro and Winters Reference Weitz-Shapiro and Winters2017, and resources for civic engagement, such as income. This finding is in line with earlier work on government transparency, suggesting that low-educated citizens may be a bit ‘lost in transparency’ (Cicatiello, De Simone and Gaeta Reference Cicatiello, Simone and Lucio Gaeta2018; Piotrowski and Van Ryzin Reference Piotrowski and Van Ryzin2007). These patterns suggest that nuanced perceptions of MPs’ (non-)transparency and side incomes depend on voters’ level of information, skills (education), and resources for civic engagement, such as income.

Moreover, ideological orientation also impacts how attentive respondents are to MPs’ transparency status. Income disclosure as well as politicians’ earnings are traditionally more strongly associated with left-wing voters and parties (Campbell and Cowley Reference Campbell and Cowley2014; Guillamón, Bastida and Benito Reference Guillamón, Bastida and Benito2011; Piotrowski and Van Ryzin Reference Piotrowski and Van Ryzin2007). In line with these findings, Figure 5, bottom row, indicates that non-disclosure and differences in side income register more strongly with left-leaning respondents. Left-leaning respondents ‘punish’ nontransparent parliamentarians more than right-leaning respondents, and when income information is disclosed, they also reward MPs more for their transparency. This is again consistent with earlier research on government transparency, which suggests that transparency is more highly valued by voters from the left of the ideological spectrum (Tejedo-Romero and Ferraz Esteves Araujo Reference Tejedo-Romero and Araujo2023). At the same time, more right-leaning respondents are, in general, more trusting and more intent on voting for any MP in our vignettes – regardless of side income disclosure and amounts. Taken together, this implies that MPs appealing to a right-wing electorate have comparatively less to gain from income transparency. This entails important real-world implications, as politicians’ party affiliation will consequently affect the extent to which they benefit electorally from disclosing outside income.

Conclusion and discussion

This study investigated key questions about MPs’ side income disclosure: how voters assess the trustworthiness and electability of transparent and nontransparent parliamentarians, and what income cues voters use. Using data from a single-vignette experiment run in seven European countries, we demonstrated that, compared to parliamentarians who are unwilling to disclose their side income due to privacy concerns, disclosure of side job earnings significantly improves voters’ perception (trustworthiness and electability) of MPs. The positive effect of transparency holds regardless of whether income disclosure reveals no side income, 20 percent, or 150 percent of the parliamentary salary as additional income. When MPs do not disclose their side income, voters use information about their extra-parliamentary jobs as heuristics for assessing trustworthiness and electability. MPs holding five company board positions – an indicator of strong personal financial interests – are evaluated most negatively by voters.

Arguably, the strong positive effect of transparency has three main beneficiaries: voters, politicians, and, as a corollary, representative democracy. Voters increase their trust in their elected officials once side income is disclosed. Transparent MPs also benefit, as citizens are more likely to vote for them. In line with previous research on over-compliance with campaign financing transparency (Wood Reference Wood2023), our results suggest that voluntarily transparent MPs gain an advantage over non-transparent competitors in electoral contexts where income disclosure is not mandatory.

Our findings reinforce the established aversion of voters to high income (Pedersen, Hansen and Pedersen Reference Pedersen, Hansen and Pedersen2022; Pedersen and Pedersen Reference Pedersen and Holm Pedersen2020). At the same time, though, they go against the suggestion that concealing components of their earnings might be in parliamentarians’ own best interest (Pedersen, Dahlgaard and Pedersen Reference Pedersen, Dahlgaard and Pedersen2019). Despite voters disapproving of high(er) earnings, they still prefer a parliamentarian who earns an additional 150 percent of their parliamentary salary to one who does not disclose their income.

Our study established with an experimental design that voters’ preference for income disclosure is a robust pattern across seven different national parliaments in Europe. Nonetheless, it would be remiss to claim that the desire for side income transparency is universal. For example, different value systems, such as those in Asian democracies, may lead voters to see transparency in a different light, as we know from previous work (Grimmelikhuijsen et al. Reference Grimmelikhuijsen, Porumbescu, Hong and Im2013). And even within the same cultural context, voters’ expectations might vary depending on what type of elected office – local, regional, national, legislative, executive, judiciary, etc. – a politician holds. Future research should therefore explore in more detail in which contexts and under what conditions voters desire transparency.

Moreover, we advise caution in extrapolating the effect magnitudes of transparency from the experiment to real-world political behavior (see Barabas and Jerit Reference Barabas and Jerit2010). While our results suggest that politicians appealing to a more left-leaning electorate benefit more from transparency, we did not directly test for MPs’ party affiliation. Previous research indicates that voters are more likely to overlook or rationalize potential transgressions, such as corruption allegations, by politicians from their own party than those from the opposition (Anduiza, Gallego and Muñoz Reference Anduiza, Gallego and Muñoz2013). More research is therefore needed to determine how partisan in-group and out-group dynamics affect attitudes toward (non-)transparent politicians, especially in polarized political environments.

Finally, our findings also speak to practitioners and demonstrate that the recent development in several parliaments toward more transparency has been in accordance with public preferences. The clear result that voters are in favor of side income disclosure for MPs can also spur the debate on more transparency in other areas of politics. It should constitute a fruitful avenue to explore voters’ attitudes toward different types of side jobs more broadly. What rules and regulations for side jobs define an environment that is most trust-inducing for voters? For example, are they in favor of banning paid side jobs altogether (as is the case for example in France and Spain), banning certain types of paid and unpaid side jobs (as is the case in Slovenia), or allowing all side jobs with either very low (Switzerland) or high degrees of income transparency (Germany, United Kingdom etc.)? Moreover, what are the ramifications of transparency measures on the linkages between MPs and interest groups? While many follow-up questions remain, the implications of this study are clear: voters value MPs’ side income transparency, and this transparency can serve as a trust-inducing instrument in societies characterized by low trust in politicians.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1475676525100303

Data availability statement

The data and script required to recreate the tables and figures in both the article and online appendix are available on Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/I6VM9P.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants of the research seminar of the Department of Government at the University of Vienna, as well as Alexandra Federsen, Tom Louwerse, and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Funding statement

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding for this study from the Swiss National Science Foundation [grant number 183248].

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to disclose.

Ethics approval statement

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study received approval from the Ethics Commission of the Geneva School of Social Sciences at the University of Geneva (CER-SDS-30-2020).