The accountability vision of democracy is for voters to ‘throw the rascals out’ by sanctioning governments that perform poorly (Barro, Reference Barro1973; Ferejohn, Reference Ferejohn1986) and selecting new governments that are likely to perform better (Duch & Stevenson, Reference Duch and Stevenson2008). In order for this to work, voters must have reasonably accurate perceptions of the distribution of policy responsibility among their electoral options. With this knowledge, they can remove incumbents that are responsible for bringing about undesirable policy outcomes and select new policymakers that are more likely to steer policy in a different direction. It is thus critical to understand whether voters attribute more policy outcome responsibility to parties that are more responsible for bringing policy outcomes about in order to understand whether and how accountability can work (Fortunato et al., Reference Fortunato, Lin, Stevenson and Tromborg2021).

Research in political psychology has so far mostly drawn pessimistic conclusions about voters’ ability to attribute responsibility in ways that are consistent with traditional visions of accountability (Bisgaard, Reference Bisgaard2015, Reference Bisgaard2019; Marsh & Tilley, Reference Marsh and Tilley2010; Tilley & Hobolt, Reference Tilley and Hobolt2011; Zell et al., Reference Zell, Stockus and Bernstein2021). The problem is that voters use partisan‐motivated reasoning when they form their perceptions of government responsibility. Specifically, voters base their attributions of responsibility to the government on whether their preferred party is in office and whether the policy conditions are desirable or undesirable. Government supporters attribute more responsibility to the government than opposition supporters do when conditions are good, and when conditions are bad, they blame external forces, such as banks or the global economy, instead of the government. These attributional patterns weaken any possible linkage between government performance and voting behaviour.

This paper offers a more sanguine view of voters. It redirects the question from asking whether partisan‐motivated reasoning influences the way voters attribute responsibility (which existing research demonstrates it clearly does), to asking whether voters meet the responsibility attribution requirement of accountability despite the presence of partisan‐motivated reasoning. Generating an answer to this question requires going beyond the dominant analytical approach of comparing how government supporters and opponents attribute responsibility to the government versus external forces.Footnote 1 The problem with this approach – for understanding the redirected question – is that external forces are not up for election. In order to understand whether voters’ responsibility attributions are consistent with traditional visions of accountability, it is necessary to compare responsibility attributions between all the political parties that voters are supposed to select from when they vote. If voters attribute more responsibility to government parties than opposition parties, despite their partisan biases, then they can use these attributions to hold government parties accountable for bad policy (by selecting a party in the opposition that is blamed less) and to reward government parties for good policy (by selecting a party in the more responsible government). Furthermore, it is necessary to make this comparison for the full electorate, and not just for those who identify with a party in the government or in the opposition, as independent voters constitute a sizeable segment of the electorate in parliamentary democracies (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Bankert and Davies2018).

In this paper, the perceived party distribution of responsibility is analyzed with original survey data from Denmark and the United Kingdom – two cases with varying degrees of institutionalized power‐sharing. The analyses of the data, which are presented in full in the next section, indicate that voters’ party preferences are related to their responsibility attributions, but also that voters (both partisans and independents) attribute systematically more responsibility to government parties than opposition parties, even when it means acknowledging that a preferred party has performed poorly. This is crucial to know because it means that many voters actually do attribute responsibility in ways that are consistent with the accountability vision of democracy, despite the presence of partisan‐motivated reasoning. In other words, partisan‐motivated responsibility attributions do not rule out accountability on their own.

There are, however, also some important caveats. First, the results suggest that while government supporters are willing to blame the government when they perceive that policy outcomes are desirable, opposition supporters are less willing to credit the government when they perceive that policy conditions are undesirable. This changes the nature of any possible accountability linkage between voters and their policymakers, although it does not rule out such a linkage. Rather, it may be a mechanism behind the empirical regularity that there is an electoral ‘cost of governing’ (Klüver & Spoon, Reference Klüver and Spoon2020; Rose & Mackie, Reference Rose, Mackie, Daalder and Mair1983). Second, the result that government identifiers and independents attribute responsibility in ways that can facilitate accountability does not necessarily mean that they will facilitate accountability. In order for that to happen, there are other accountability conditions that need to be met. For example, voters must incorporate their responsibility attributions when they vote, and their perceptions of policy outcome desirability must be reasonably objective and not entirely driven by party identification. These conditions are not tested in this paper because – like the literature it addresses – it focuses on partisan‐motivated reasoning in responsibility attributions. The concluding section reflects more on this and other important points and avenues for future research.

Do voters attribute more responsibility to the government than the opposition?

The empirical analysis is based on original mass survey data from Denmark and the United Kingdom.Footnote 2 The surveys were implemented in February 2019. All surveys were implemented online using panel respondents from the survey company Dynata (www.dynata.com). The panelists were contacted by email and received reward points for answering the survey to redeem for cash and prizes. In order to improve representativeness, the panel members were accepted (or not accepted) to take the survey in real time to meet demographic targets on age and gender that matched the census proportions for these demographics. The survey also appears to be fairly representative in terms of party preferences as these preferences are highly correlated with the subsequent election outcomes within each country (reported in more detail in Supporting Information Appendix A.1). The survey questions were designed to assess the relationship between party roles, party identification, and responsibility attributions for the state of the economy. The focus is on the economy because it is a normatively important policy area that has received much attention from both accountability research in general and the motivated reasoning literature specifically (Duch & Stevenson, Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Anderson, Reference Anderson1995; Anson, Reference Anson2017; Bisgaard, Reference Bisgaard2015). 1,790 respondents in Denmark and 1,987 respondents in the UK completed the survey.

The two country cases were chosen primarily because they have important variation on institutional clarity of responsibility (Powell & Whitten, Reference Powell and Whitten1993). Clarity of responsibility is relatively low in the proportional representation system of Demark and relatively high in the United Kingdom plurality system. There are two main reasons for this. First, the government in the United Kingdom was a single‐party government (the Conservatives relying on the support of the Democratic Unionist Party for a legislative majority) at the time of the survey, while the government in Denmark was a three‐party coalition (the Liberals held the prime ministry in a coalition with the Conservatives and the Liberal Alliance while relying on the support of the Danish People's Party for a legislative majority). Second, the opposition has more opportunity to provide inputs in the policymaking process in Denmark than in the United Kingdom through the committee system (Döring, Reference Döring1995; Fortunato et al., Reference Fortunato, Martin and Vanberg2017). The expectation from previous research is thus that the responsibility attribution gap should be larger in the UK than in Denmark, though other factors may, of course, determine this as well (e.g., the opposition's past performance).

Before turning to the data and analysis, it is important to note that it is not possible to know exactly what the true difference in responsibility between the government and the opposition is (indeed, this is what enables voters to use partisan‐motivated reasoning in the first place). We know from the extant literature that government parties are relatively more responsible for policy than the opposition because the government initiates the vast majority of legislative bills (Andeweg & Nijzink, Reference Andeweg, Nijzink and Döring1995; Döring, Reference Döring1995; Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011), and the laws that are enacted tend to be consistent with government party preferences (Allan & Scruggs, Reference Allan and Scruggs2004; Hartmann, Reference Hartmann2014; Naurin et al., Reference Naurin, Royed and Thomson2019). However, we do not know precisely how large the attributional gap should be, and this is further complicated by the fact that past actions by the opposition (e.g., when it was in government) could also influence present day outcomes. This means that while the substantive size of the attributional gap between the government and the opposition is interesting in and of itself, it is not possible to conclude that one attributional gap size is ‘better’ suited to facilitate accountability than another.

Methods and analysis

There are four key variables in the empirical analysis, namely (1) perceived party responsibility for the state of the economy, (2) the perceived state of the economy, (3) party identification, and (4) true party roles in the government versus opposition. The first three variables are measured with the survey questions and response options below, which were presented to the respondents in the same order as they are shown.Footnote 3 The full list of party options and more details about the survey are given in Supporting Information Appendix A.1.

Party identification: Many people consider themselves supporters of a particular party. There are also many people who do not support a particular party. Do you, for example, think of yourself as [COUNTRY‐SPECIFIC PARTY NAMES] or something else, or do you not think of yourself as a supporter of a particular party?

1) Yes, I consider myself a supporter of a particular political party 2) No, I do not consider myself a supporter of a particular political party, 3) Don't know.Footnote 4

Perceived state of the economy: Looking back over the last year, would you say that the state of the economy in the [COUNTRY NAME] has gotten much better, somewhat better, stayed the same, somewhat worse, or much worse?

1) Much worse, 2) Somewhat worse, 3) Stayed the same, 4) Somewhat better, 5) Much better.

Perceived responsibility: How much responsibility do you think each of the following parties has for the development of the economy in the [COUNTRY NAME] over the last year?

1) No responsibility, 2) A little bit of responsibility, 3) A moderate amount of responsibility, 4) A lot of responsibility, 5) Complete responsibility.

The baseline statistical model takes the following form, where i indexes each respondent and t indexes each party.

$$\begin{eqnarray}{{\rm{Y}}_{{\rm{ip\;}}}} &=& {{\alpha}} + {{{\beta}}_1}Econper{c_{\rm{i}}} + {{{\beta}}_2}Gv{t_{\rm{p}}} + {{{\beta}}_3}Partyi{d_{{\rm{ip}}}}\nonumber\\ &&+\; {{{\delta}}_1}[Econper{c_{\rm{i}}} \times Gv{t_{\rm{p}}}] + {{{\delta}}_2}[Econper{c_{\rm{i}}} \times Partyi{d_{{\rm{ip}}}}]\nonumber\\ &&+\; \mathop \sum \limits_{k\; = \;1}^3 {{{\theta}}_k}{{\rm{X}}_{ik}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{k\; = \;1}^3 {{{\lambda}}_k}\left[ {{{\rm{X}}_{ik}}{\rm{\;}} \times {\rm{\;}}Gv{t_{\rm{p}}}} \right] + \mathop \sum \limits_{c\; = \;1}^2 {{\rm{\varphi }}_c}{{\rm{X}}_{pc}} + {{\rm{\varepsilon }}_{{\rm{ip}}}}\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}{{\rm{Y}}_{{\rm{ip\;}}}} &=& {{\alpha}} + {{{\beta}}_1}Econper{c_{\rm{i}}} + {{{\beta}}_2}Gv{t_{\rm{p}}} + {{{\beta}}_3}Partyi{d_{{\rm{ip}}}}\nonumber\\ &&+\; {{{\delta}}_1}[Econper{c_{\rm{i}}} \times Gv{t_{\rm{p}}}] + {{{\delta}}_2}[Econper{c_{\rm{i}}} \times Partyi{d_{{\rm{ip}}}}]\nonumber\\ &&+\; \mathop \sum \limits_{k\; = \;1}^3 {{{\theta}}_k}{{\rm{X}}_{ik}} + \mathop \sum \limits_{k\; = \;1}^3 {{{\lambda}}_k}\left[ {{{\rm{X}}_{ik}}{\rm{\;}} \times {\rm{\;}}Gv{t_{\rm{p}}}} \right] + \mathop \sum \limits_{c\; = \;1}^2 {{\rm{\varphi }}_c}{{\rm{X}}_{pc}} + {{\rm{\varepsilon }}_{{\rm{ip}}}}\end{eqnarray}$$This baseline model is run three separate times within each country, one for each group of voters (government identifiers, independents, and opposition identifiers). This is because there are different expectations regarding the direction and size of the independent variable coefficients within each group. Running the analyses separately (as opposed to using three‐way interaction terms) ensures maximum flexibility in the parameter estimates and a more intuitive interpretation of the regression coefficients (reported in Appendix A.3).Footnote 5 The model is run separately for each country for the same reasons, and also because voters in the two countries assign responsibility to different parties in different sized party systems (resulting in unbalanced panels).Footnote 6 The unit of analysis for each group of voters is the respondent‐party such that the number of observations for each respondent is equal to the number of parties in the respondent's party system.

The dependent variable (perceived responsibility) and (the independent variable) Econperc (perceived state of the economy) are measured using the five‐point Likert scales from the response options. Gvt (party government status) and Partyid (party identification) are dummy variables that take the value 1 if the party being attributed responsibility is a party in government and if the respondent identified with the party, respectively (0 otherwise). Econperc is interacted with Gvt (with parameter δ1) to test whether each of the three groups of voters attribute more responsibility to government than opposition parties for the full range of beliefs about the state of the economy. Econperc is also interacted with partyid (with parameter δ2) in order to provide an estimate of responsibility attributed to the specific party within the governing coalition that government supporters identify with (in Denmark), and the specific party within the opposition that opposition supporters identify with (in both Denmark and the United Kingdom). δ2 thus enables an estimate of voters’ responsibility attributions to the government versus the opposition using the specific party they identify with as the baseline for that comparison. The second interaction term is excluded in the model analyzing responsibility attribution among government supporters in the United Kingdom because all respondents within this subset identify with the same party (meaning that the baseline for the comparison between the government and the opposition is still the government party the respondent identifies with). It is also excluded for the models analyzing independents because they do not identify with a party.

The model also controls for three individual level variables (X ik) and two‐party level variables (X pc). The individual level variables (gender, age and political interest) are interacted with the government variable in order to account for the possibility that these characteristics of an individual influence their responsibility attribution gap and the perceived state of the economy. The variables further have the useful feature that they are unlikely to result in post‐treatment bias because of their exogenous nature.Footnote 7 The two party level variables (a party's legislative seat share, and whether or not the party is an outside support party for a minority government) are controlled for because they are related to the probability of a party being in government (deterministically so for the support party variable), and they could simultaneously influence a party's perceived responsibility. To be sure, it would actually be quite reasonable for voters to attribute responsibility according to these party characteristics because they are also important in the policy‐making process (Fortunato et al., Reference Fortunato, Lin, Stevenson and Tromborg2021).Footnote 8 However, controlling for them enables a more accurate estimate of the effect of a party's government status. Summary statistics for all the variables used in the models are reported in Appendix A.2.

It is important that to note that, despite the inclusion of control variables, the model allows for the causal ordering of economic perceptions and responsibility attributions to flow in both directions. Specifically, it is possible that party identifiers use partisan‐motivated reasoning to attribute more responsibility to the party they identify with when they perceive the economy has improved, but they may also perceive a better economy because they believe that the party they identify with is responsible for the state of the economy. The crucial point, however, is that the model allows for an analysis of the relationship between a party's true government or opposition status and its perceived responsibility among a set of voters who have been able to resolve their cognitive dissonance using the various partisan‐motivated reasoning mechanisms they have available. This is not to say that the causal ordering of economic perceptions and responsibility attributions is unimportant, but it is beyond the scope of this paper to disentangle it (for an attempt see Tilley & Hobolt, Reference Tilley and Hobolt2011).Footnote 9

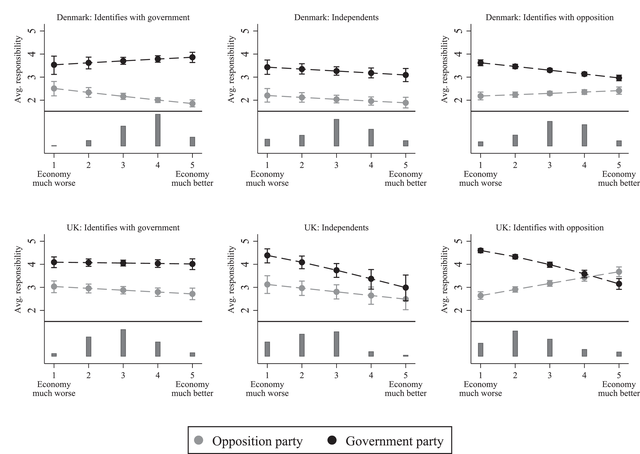

The model uses an ordered probit estimator given the ordered nature of the dependent variable.Footnote 10 Consequently, α refers to the cut points for the adjacent levels of the latent dependent variable. The multilevel structure of the dataset is addressed with the use of random effects that allow the intercepts to vary at the level of individual respondents.Footnote 11 This accounts for the possibility that individual respondents view the responsibility attribution scale differently and attribute systematically more or less responsibility to all parties. The parameter estimates from this model specification are reported in Appendix A.3, and the substantive effects are visualized in Figure 1. This figure graphs average responsibility attributions to government and opposition parties over the perceived state of the economy for each group of voters. For government and opposition supporters, respectively, the government and opposition party values represent responsibility attributions to the specific government and opposition parties that the respondent identified with.

Figure 1. Substantive responsibility attributions among different groups of voters. Note: The figure shows average responsibility attributed to government and opposition parties among three groups of voters: Government identifiers (n = 367; N = 3,154 in Denmark, n = 568; N = 4,259 in the United Kingdom), independents (n = 277; N = 2,299 in Denmark, n = 261; N = 1,807 in the UK), and opposition identifiers (n = 1,146; N = 9,719 in Denmark, n = 1,158; N = 8,595 in the United Kingdom). Vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals. Vertical bars at the bottom of the subfigures represent the distribution of economic perceptions within each voter group. The control variables are set to their median value in their country sample, except for the party size variable, which is set to the median value in the country's government to make the value representative for both the government and (large) opposition parties.

The main takeaway from Figure 1 is that both party identification and objective party roles are related to responsibility attributions. Government identifiers tend to attribute more responsibility to the party they identify with in the government, and less to the opposition, when they perceive the economy is doing better (except, surprisingly, in the United Kingdom). Likewise, those who identify with a party in the opposition attribute more responsibility to their preferred party when they perceive the economy is doing well and less to the government (in both Denmark and the United Kingdom). This pattern seems to be stronger for opposition identifiers than for government identifiers. In fact, opposition identifiers in the United Kingdom attribute more responsibility to their preferred party than to the government when they perceive a much better economy. These patterns are consistent with responsibility attributions being biased by partisan‐motivated reasoning, as demonstrated by previous research. However, despite this attributional bias, government parties are still attributed more responsibility than opposition parties on average. This is true both for government identifiers and independents regardless of the perceived state of the economy. To be sure, the attributional gap between the government and the opposition is much smaller when government identifiers perceive that the economy is in decline (in Denmark), but the government is nonetheless attributed more responsibility, even when the economy is perceived to be ‘much worse’ during the tenure of the preferred party.Footnote 12

Collectively, the results suggest that voters attribute responsibility in ways that are consistent with traditional visions of accountability.Footnote 13 Specifically, the attributional patterns in Figure 1 have the potential to enable a system of accountability where government parties are blamed by all types of voters when they are perceived to perform poorly, but credited by their own supporters and independents when they are perceived to perform well. This is interesting because it is consistent with another well‐established pattern in political science, namely the cost of governing (Klüver & Spoon, Reference Klüver and Spoon2020; Rose & Mackie, Reference Rose, Mackie, Daalder and Mair1983; Strom, Reference Strom1990). Specifically, governing tends to be ‘costly’ in the sense that government parties generally lose more votes than they gain between elections. The reason for this electoral cost of governing is not yet well established, but the results presented here may have revealed an important mechanism. They indicate that it is more difficult for governments to receive credit for desirable outcomes from opposition supporters than it is for governments to be blamed for undesirable outcomes by their own supporters.

Conclusion

This paper has demonstrated that voters tend to attribute policy responsibility in ways that are consistent with normative visions of accountability despite their partisan‐motivated reasoning. While party identification is related to voters’ attributions of responsibility, so are true party roles in the legislative process. Opposition identifiers do appear to be hesitant to attribute responsibility to the government for desirable outcomes (especially in the United Kingdom), but both independents and government supporters attribute systematically more responsibility to the government than to the opposition even when they perceive that the policy outcome is bad. This suggests that many voters attribute responsibility in ways that they can use to facilitate accountability by rewarding and sanctioning incumbent governments for their policy actions.

It is important to reiterate that the finding that voters’ responsibility attributions can facilitate accountability does not necessarily mean that they will facilitate accountability. This paper addresses existing research on partisan‐motivated reasoning in responsibility attributions, and thus focuses on perceptions of responsibility as the outcome. Yet, in order for sensible responsibility attributions to translate into accountability, voters also need to act on their assignments of responsibility when they vote, and their perceptions about policy outcomes must be reasonably accurate on average. One possible problem is that partisan‐motivated reasoning may bias the information that voters receive, and accept, about the policy conditions (Achen & Bartels, Reference Achen and Bartels2016; Flynn et al., Reference Flynn, Nyhan and Reifler2017; Jerit & Barabas, Reference Jerit and Barabas2012; Nyhan & Reifler, Reference Nyhan and Reifler2010). The analysis presented here provides some evidence in favour of this type of partisan bias occurring. Specifically, government supporters tend to perceive a better state of the economy, which is illustrated in the economic perceptions distributions in Figure 1. However, the figure also demonstrates that – despite this bias – many government supporters still perceive slight to severe economic decline, and many opposition supporters perceive economic improvement. This indicates that while partisan motivated reasoning almost certainly shapes voter perceptions about policy outcomes, many voters still receive, and accept, information about policy outcomes that does not reinforce their partisanship. This is consistent with other research demonstrating that there is a correspondence between true policy outcomes and voters’ perceptions of what those outcomes are (Duch & Stevenson, Reference Duch and Stevenson2008).

Given all of this, the results presented here send an optimistic message to the theoretical and normative literatures on representation. Despite long‐standing scepticism, the results suggest that voters hold perceptions about the party responsibility distribution that have the potential to facilitate accountability. This does not mean that studying partisan‐motivated reasoning is uninteresting or unimportant. On the contrary, the analysis suggests that partisan‐motivated reasoning likely weakens the accountability linkage between voters and their representatives. For example, government identifiers who perceive a bad economy attribute less responsibility for this outcome to the government than government identifiers who perceive a good economy (perhaps blaming external actors instead). Yet, the results also demonstrate that partisan‐motivated responsibility attributions do not rule out accountability on their own. Government identifiers who perceive a bad economy attribute more responsibility for this outcome to the government than to the opposition. This is not only important to know in order to understand whether and how accountability can work, but also in order to understand what the implications of partisan‐motivated reasoning are for democratic representation.

Acknowledgements

This article has benefitted greatly from comments made by Roman Senninger, Mathias Osmundsen, Martin Bisgaard, participants at the 2019 annual Danish Political Science Association (DPSA) meeting, and members of the behaviour and institutions section at Aarhus University. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. [817855]), and from the Aarhus University Research Foundation (Grant agreement No. [AUFF‐E‐201 7‐7‐14])

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Online Appendix