What does democracy require? Government ‘by the people’ can be implemented in many ways. While some propose that democracy should be people-centred, with citizens having a direct say in specific decisions made by their government, others believe that citizens are best served by leaving political decisions to political elites, with less input from the broader population. Although there is a growing literature that studies citizens’ process preferences with regard to how democratic decisions are made, much less is known about how elected officials view democracy and their own role in it. John Hibbing and Elizabeth Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002: 47) argued that citizens perceive representatives as holding more ‘institutional’ conceptions of democracy, which are at odds with their own preference for more ‘direct’ democracy. However, we do not know whether this perception is a fair one. Moreover, the rise of populist parties and candidates across many liberal democracies is likely to be reflected in legislators’ views concerning the institutions of representative democracy.

This paper leverages data from two surveys of state and federal legislators in Germany and the United States fielded in 2022 and 2023, respectively, to explore legislators’ process preferences in both countries. In measuring process preferences, we follow Hibbing and Theiss-Morse’s one-dimensional approach, using a continuous scale ranging from maximally elite-centred institutional preferences at one end to maximally people-centred preferences at the other. While Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002) rely on citizens’ perceptions of process preferences among the elite to draw their conclusions about a gap existing between citizen and elite attitudes, we survey legislators directly. Given that the challenges of gathering data from elite samples means we have very limited information about this important group’s perspective on the process of democratic governance, our surveys thus help fill a significant research gap.

Existing comparative studies of process preferences among elites have focused largely on European countries and almost never include the United States (though see Bowler et al. Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2002). Many of them draw on comparative datasets from 2007 to 2012, thus focusing on an earlier political and social context (though see Mongrain et al. Reference Mongrain, Junius and Brack2024). While these foundational studies provide essential findings on which we draw, they leave many questions unanswered about how legislators view the proper functioning of democracy in the present context and about whether theories predicting these attitudes hold up across different democratic systems. Other studies consider the attitudes of political elites towards democracy in individual countries or regions, leaving the transatlantic perspective underexplored. In light of the rise of populism, growing polarization and tendencies towards autocratization in the United States, a comparison between US political elites and those in Germany, Europe’s largest democracy, seems overdue.

Institutionally, there are similarities (federalism, judicial review) as well as differences (electoral system, presidentialism versus parliamentarism) between the two countries. The most important difference, however, concerns expert ratings of regime quality. Whereas Germany’s 2025 snap elections resulted in a peaceful transition of power and a centrist ‘grand coalition’ government, the United States has, under Trump’s second presidency, come to be described as a regime of ‘competitive authoritarianism’ (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2002) and has been re-classified as a non-democracy by the prestigious POLITY index.Footnote 1 These developments seem to confirm concerns regarding the effects of growing societal and political polarization. V-Dem data show a steep increase of both indicators in both countries in the last decade. However, while Germany is classified as ‘somewhat’ politically and ‘moderately’ societally polarized, the United States has reached extreme values for both indicators since 2017 (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Angiolillo, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Fox, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Good God, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Krusell, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Medzihorsky, Natsika, Neundorf, Paxton, Pemstein, von Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Sundström, Tannenberg, Tzelgov, Wang, Wiebrecht, Wig, Wilson and Ziblatt2025). Our data enable us to consider whether and how these developments are reflected and how recent events were foreshadowed in the way political elites in both countries view the functioning of democracy.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section reviews the relevant literature and spells out our theoretical expectations and hypotheses. The subsequent section describes the legislator surveys we draw on and the methods used to study the data. Following this, we present our results. We find that while German legislators are distributed normally along the continuum from preferences for elite-centred democracy to people-centred democracy, US legislators lean towards the latter. Focusing on the determinants of legislators’ process preferences, we find that despite the different national contexts and different levels of support for elite- vs people-centred democracy, they are generally similar in both countries. Specifically, process preferences seem largely to be driven by instrumental motivations resulting from contextual conditions such as control of government, seniority and electoral security.

Theory and the state of the art

Hanna Pitkin famously defined representation as ‘acting in the interest of the represented, in a manner responsive to them’ (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967: 209). She argues that a representative’s actions should not be at odds with those of the represented, unless the representative has a good reason and explanation for it. Building on this argument, the literature on policy responsiveness establishes a high congruence between citizen preferences and government policies as a key indicator for democratic quality.

This claim is not limited to the policy space but can be extended to procedural concerns as well: citizens have various expectations regarding the institutionalization of democracy and they expect their leaders and representatives to mirror these preferences and to act accordingly. Therefore, when citizens prefer to be governed under one set of procedures (such as having access to referendums allowing direct policy-making by citizens) while the elites prefer a different system (such as one in which elected officials make policy based on party plans regardless of the level of citizen support) a procedural preference gap arises. Because day-to-day governance generally occurs without direct citizen involvement, procedural preference gaps can easily produce governance processes that are more in line with elite rather than citizen preferences. However, just as with a substantive gap in policy preferences, a gap in ‘process preferences’ between citizens and the political elites concerning decision-making procedures has the potential to decrease citizens’ satisfaction with democracy and therefore poses a threat to the political system (André and Depauw Reference André and Depauw2017).

The process preference gap was first and most prominently discussed by Hibbing and Theiss-Morse in their 2002 book on ‘Stealth Democracy’. In the book, they examine the difference between ‘institutional democrats’, who want to assign all political power to elected politicians, and ‘direct democrats’, who prefer ordinary citizens to be in charge. Treating these categories as two opposing poles of a continuous scale, they allow for more nuanced process preferences of both citizens and legislators (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002: 43). Their findings demonstrate that US citizens’ attitudes form a normal distribution, with most people preferring a balanced distribution of political power. However, respondents perceive both political parties and the functioning of the government in general to lean heavily towards the institutional side of the spectrum, creating a gap between citizens and elites in the process space (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002: 45–48).

It remains questionable whether these findings were only a snapshot of public opinion or more universally valid, especially considering trends in public opinion since the publication of Hibbing and Theiss-Morse’s book more than 20 years ago. On the one hand, a considerable share of citizens appears to be broadly supportive of elite-centred and technocratic ideas (e.g. Bloeser et al. Reference Bloeser, Williams, Crawford and Harward2022; Hibbing et al. Reference Hibbing, Theiss-Morse, Hibbing and Fortunato2023). On the other hand, citizens in the United States as well as in Europe seem to have become strongly people-centred when confronted with the aforementioned distinction between ordinary citizens and elected leaders. This can be observed with regard to various indicators, such as a clear preference for the voter delegate style of representation (e.g. Bengtsson and Wass Reference Bengtsson and Wass2011; Carman Reference Carman2006), or procedural preferences for direct democracy (e.g. Donovan and Karp Reference Donovan and Karp2006). To assess the size of the gap between citizen and elite preferences arising from these developments, it is necessary to get an updated view of where legislators stand on these issues and, more importantly, to look at the actual positions of legislators rather than citizens’ perceptions of them. Unfortunately, existing research rarely studies legislators’ process preferences in such a broad, comprehensive sense, and instead mostly focuses on specific aspects and indicators.

One big strand of research established by the seminal works of Heinz Eulau et al. (Reference Eulau, Wahlke, Buchanan and Ferguson1959) and Warren Miller and Donald Stokes (Reference Miller and Stokes1963) is centred around representational roles and styles of representation, usually distinguishing between elite-centred trustees, people-centred voter delegates, and party delegates. While a study by Åsa von Schoultz and Hannah Wass (Reference von Schoultz and Wass2016) comparing citizens and political candidates in Finland shows that their preferences are surprisingly well aligned in this regard, a more recent contribution by Philippe Mongrain et al. (Reference Mongrain, Junius and Brack2024) comparing citizens and legislators in 13 countries shows legislators to be much more elite-centred than citizens.

Other recent comparative studies give some insights into country differences and the effects of different institutional contexts. Multiple studies report that there are barely any voter delegates in Germany (Dudzińska et al. Reference Dudzińska, Depauw, Deschouwer and Depauw2014; Önnudóttir Reference Önnudóttir2016), indicating little people-centrism and a stronger leaning towards elite-centred democracy. The comparative analyses also suggest that national legislators are less people-centred than regional legislators (Dudzińska et al. Reference Dudzińska, Depauw, Deschouwer and Depauw2014), that control of government decreases people-centrism (Mongrain et al. Reference Mongrain, Junius and Brack2024; Önnudóttir Reference Önnudóttir2016), and that legislative experience increases a preference for elite-centred democracy (Önnudóttir and von Schoultz Reference Önnudóttir, von Schoultz, De Winter, Karlsen and Schmitt2021). Earlier studies also report a clear ideological split, with more conservative legislators being the least people-centred (Damgaard Reference Damgaard1997), although this is not confirmed by more recent contributions (e.g. Önnudóttir Reference Önnudóttir2016).

Arguably, the rise of right-wing populism in both the United States and Europe might have blurred this correlation. Generally, populist attitudes are empirically linked to a preference for direct democracy – and thus more people-centred procedures – among the citizenry (e.g. Mohrenberg et al. Reference Mohrenberg, Huber and Freyburg2021; Zaslove and Meijers Reference Zaslove and Meijers2024). In fact, feeling ‘left behind’ and not represented by political elites increases populist attitudes among citizens (Castanho Silva and Wratil Reference Castanho Silva and Wratil2023; Habersack and Wegscheider Reference Habersack and Wegscheider2024; Huber et al. Reference Huber, Jankowski and Wegscheider2023), which suggests that increasingly elite-centred process preferences among political elites could cause societal grievances and thus feed into the growth of populist attitudes observed in recent years. In terms of populist political elites’ support for direct democracy and people-centrism, a study comparing citizens’ and political candidates’ attitudes in Australia, Canada and New Zealand finds that right-wing candidates have a stronger preference for direct democracy compared to candidates of other parties, but supporters of right-wing populist parties are not more likely to favour referendums than supporters of other parties (Bowler et al. Reference Bowler, Denemark, Donovan and McDonnell2017). Furthermore, a study of support for citizen participation among local-level Flemish politicians shows both progressive and right-wing populist politicians to be more people-centred (Caluwaerts et al. Reference Caluwaerts, Kern, Reuchamps and Valcke2020).

Another strand of research focuses on the specific procedural preferences of legislators concerning direct democracy and democratic innovations more broadly. Shaun Bowler et al. (Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2002) show that US legislators have a quite favourable opinion of direct democracy in general but are not supportive of binding initiatives. In line with some of the studies mentioned above, their results also indicate that control of government and seniority increase the lean towards elite-centred democracy. Similarly, two studies focusing on Sweden show legislators in the parliamentary majority to be less supportive of referendums than other parties (Gilljam and Karlsson Reference Gilljam and Karlsson2015) and less supportive of citizen protests (Gilljam et al. Reference Gilljam, Persson and Karlsson2012). A recent comparative study of 14 European countries looks at support for referendums and deliberative events, finding that legislators from opposition parties are significantly more supportive of democratic innovations (Gherghina et al. Reference Gherghina, Close and Carman2023). Nino Junius et al. (Reference Junius, Matthieu, Caluwaerts and Erzeel2020) use the same dataset to show a similar effect within the opposition, as well as the effect of electoral security concerns decreasing support for referendums.

In sum, the literature on legislators’ understandings of democracy predominantly focuses either on their understandings of their own role or their support for specific democratic innovations. Moreover, existing studies on US legislators mostly date back over 20 years, while studies of German legislators are often based on small sample sizes, with US–German comparative studies so far absent. Our study can close these research gaps and expand on existing research by analysing legislators’ process preferences on the basis of new surveys of German and US legislators. Using a continuous scale between people-centred and elite-centred understandings of democracy, we can explore both the distribution of preferences and their determinants.

Contextual conditions and case selection

While most existing studies look at single countries or only compare European countries, we adopt a transatlantic comparative perspective and look at the United States and Germany. On the one hand, this enables us to compare two cases in which societal and political polarization have been increasing in recent years (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Angiolillo, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Fox, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Good God, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Krusell, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Medzihorsky, Natsika, Neundorf, Paxton, Pemstein, von Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Sundström, Tannenberg, Tzelgov, Wang, Wiebrecht, Wig, Wilson and Ziblatt2025) and assess whether this has resulted in similar orientations vis-à-vis democracy among legislators. On the other hand, because the United States and Germany differ in their institutionalization of democracy and their political culture along several lines, by comparing the two cases we can test our hypotheses concerning contextual effects and gain information about whether similar factors shape legislators’ process preferences in different contexts.

Our selection of the United States and Germany means we are covering two prime examples of what Gabriel A. Almond (Reference Almond1956) terms an Anglo-American political system and a Continental European system, respectively. This distinction reflects significant institutional differences between the two countries. The different electoral systems and their consequences for the party system stand out as particularly relevant for our analysis. Whereas the US system is plurality-based (first-past-the-post), Germany uses mixed-member proportional representation. The American electoral system has created a party system dominated by two major parties. Government at both the state and federal level is typically controlled by a single party. In Germany, proportional representation has resulted in a multi-party system that at present necessitates coalition governments in all but one state and at the federal level. This makes Germany a typical example of continental Western Europe with regard to both the electoral and party system (see Lane and Ersson Reference Lane and Ersson1999).

Another potentially relevant difference concerns the process for nominating candidates. In the United States, the introduction of open primaries has given party supporters a significant role in the nomination process, which has contributed to the rise of more extreme and polarizing candidates (see Rosenbluth and Shapiro Reference Rosenbluth and Shapiro2018). In Germany, by contrast, candidate selection processes are still largely controlled by party elites.

Theoretical expectations and hypotheses

If we do find differences in legislators’ process preferences both within and between the two countries, how can we explain these differences? This is the core research question behind our analyses. We define ‘process preferences’ broadly, seeking to capture attitudinal patterns that connect normative ideas about the role of citizens and their representatives in a democracy to support for the existing democratic institutions or democratic innovations. Generally, process preferences can be driven by instrumental or intrinsic motivations (see Landwehr and Harms Reference Landwehr and Harms2020). However, intrinsic motivations, such as ideological convictions or moral principles guiding design preferences, are relatively more idiosyncratic and difficult to isolate. Moreover, compared to citizens, legislators may be expected to have much stronger material interests in institutional design choices, given that their careers and economic security depend on them. We thus expect a tendency among legislators to prefer processes and institutions that benefit their own interests in terms of re-election or the control of power and resources and focus our hypotheses on measuring the effects of these instrumental interests rather than politicians’ intrinsic motivations.

With regard to our dependent variable, we therefore expect legislators from parties that have better access to power and resources to hold more elite-centred process preferences. At the individual level, we similarly expect legislators with more power and resources (such as seniority and electoral security) to hold more elite-centred preferences. Finally, we expect instrumental process preferences to be at least partially dependent on the different institutional contexts of the two countries. The exact causal pathways linking individual legislators’ values, experiences and expectations to their process preferences will be difficult to identify. However, it seems plausible that a combination of strategic considerations, socialization among peers and rationalization processes results in an alignment between instrumental motivations and process preferences.

From these general theoretical considerations and specific findings within the existing research, we derive a set of more specific hypotheses. First, consistent with most comparative studies of elite process preferences, we expect differences between Germany and the United States to yield different process preferences by country and by party. Government power in Germany is held more consistently by the same parties in coalitions over time and across levels of government. In the United States, shifts in which party controls both houses of Congress and the presidency occur regularly and divided party control of government is common.

Research indicates that control of government decreases people-centrism (Bowler et al. Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2002; Mongrain et al. Reference Mongrain, Junius and Brack2024; Önnudóttir Reference Önnudóttir2016), while legislators located outside power are more likely to support people-centred processes such as referendums (Gherghina et al. Reference Gherghina, Close and Carman2023). Legislators from both parties in the United States are likely to spend some time out of power due to shifts in legislative party control or divided control of the legislative and executive branches. Moreover, US legislators in minority parties have no hope of accessing power through coalition governments. Accordingly, we expect German legislators to be more inclined to protect institutional power by holding elite-centred orientations and US legislators to be more people-centred. This also corresponds to research on differences in representational roles, which shows that German legislators have more elite-centred styles of representation than those in many other European democracies (Dudzińska et al. Reference Dudzińska, Depauw, Deschouwer and Depauw2014; Önnudóttir Reference Önnudóttir2016).

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Legislators in Germany will favour elite-centred democracy more than legislators in the United States.

Looking beyond country-level differences, a legislator’s status is likely to affect their support for existing institutions and procedures. Longer-serving legislators who have been re-elected multiple times have extensively benefited from the procedural status quo. Their experience of exercising legislative power will contribute to a more elite-centred view of democracy. Legislators at the federal level generally derive a higher social status from their office and tend to exercise more power than state legislators. Accordingly, existing research has found both senior legislators (Bowler et al. Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2002; Önnudóttir and von Schoultz Reference Önnudóttir, von Schoultz, De Winter, Karlsen and Schmitt2021) and federal legislators (Dudzińska et al. Reference Dudzińska, Depauw, Deschouwer and Depauw2014) to be more elite-centred than their counterparts. In addition, previous research points to a socialization effect that should make legislators more supportive of the existing institutions and decision-making procedures the longer they take part in them (see e.g. Önnudóttir and von Schoultz Reference Önnudóttir, von Schoultz, De Winter, Karlsen and Schmitt2021). In line with these findings, legislators’ experience that law-making requires some degree of discussion and compromise within and across parties helps them consider factors other than the immediate demands of their voters and could therefore incline them away from people-centred democracy.

Hypothesis 2a (H2a): Longer-serving legislators will favour elite-centred democracy more than shorter-serving legislators.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b): Legislators at the federal level will favour elite-centred democracy more than legislators at the state level. Footnote 2

Additionally, legislators in control of government are instrumentally motivated to protect the institution’s power rather than distributing it to the public more broadly. Accordingly, multiple studies have found legislators in the legislative majority or government coalition to be more elite-centred than their opposition colleagues (Bowler et al. Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2002; Gherghina et al. Reference Gherghina, Close and Carman2023; Gilljam et al. Reference Gilljam, Persson and Karlsson2012; Gilljam and Karlsson Reference Gilljam and Karlsson2015; Junius et al. Reference Junius, Matthieu, Caluwaerts and Erzeel2020; Mongrain et al. Reference Mongrain, Junius and Brack2024; Önnudóttir Reference Önnudóttir2016). This mechanism could also have an anticipatory component: if legislators believe their position in an institution to be more secure and expect to serve for a longer time then they have an incentive to protect that institution’s power, and this too should promote a more elite-centred rather than people-centred view of democracy. While a legislator worried about losing power in the next election may need to focus more intensively on what voters want, a legislator who is very likely to maintain power can distance themselves more easily from the immediate whims of voters. Existing research on this is less clear, but there is some initial evidence that electoral vulnerability could play a role here (e.g. Junius et al. Reference Junius, Matthieu, Caluwaerts and Erzeel2020). Similarly, previous research has shown electoral winners to be more supportive of the institutional status quo (Bowler et al. Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2006). In sum, the closer legislators are to the centre of power and the more secure they feel in this position, the more supportive of elite-centred democracy rather than people-centred democracy we can expect them to be. This leads us to two more hypotheses regarding the structural political context of legislators.

Hypothesis 2c (H2c): Legislators who are part of the legislative majority or whose party controls government will favour elite-centred democracy more than legislators whose party is out of power.

Hypothesis 2d (H2d): Legislators who view their party as electorally secure in their area will favour elite-centred democracy more than legislators who perceive their party as less electorally secure. Footnote 3

Beyond instrumental motivations and structural factors, individual legislators’ experiences of interaction and co-operation under conditions of growing polarization are likely to affect their process preferences. Ideological polarization has been found to structure attitudes towards democracy in the United States (Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Kingzette et al. Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021) and Germany, as well as in other multi-party systems (e.g. Helbling and Jungkunz Reference Helbling and Jungkunz2020; Wagner Reference Wagner2021). Trust in members of other parties, whether it results from positive experiences or reflects a more general positive out-group affect, should have an influence on a legislator’s willingness to entrust power to the institutions of government rather than the public. Thus, we expect higher trust to be associated with more elite-centred orientations concerning democracy.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Legislators who have more trust in members of other parties will favour elite-centred democracy more than legislators with little trust in other parties.

Finally, although our theory focuses on how instrumental motivations shape politicians’ process preferences, we recognize that ideological convictions are likely to affect attitudes towards democracy and that policy and process preferences may be more systematically associated (see Landwehr Reference Landwehr2025). While ideological conservatism was historically associated with a more elite-centred view of democracy (Damgaard Reference Damgaard1997), more recent research shows both right-wing populist political candidates (Bowler et al. Reference Bowler, Denemark, Donovan and McDonnell2017) and more progressive and left-wing legislators (Caluwaerts et al. Reference Caluwaerts, Kern, Reuchamps and Valcke2020) to be more people-centred than members of other parties. Hence, we include variables measuring economic and cultural ideology in our models in order to update research on this relationship, but we have no explicit hypothesis regarding their effect.

Data and method

We explore legislators’ preferences using two online surveys conducted in 2022 among German legislators and in 2023 among US legislators. The two surveys were largely identical, although the US survey included some additional attitudinal items. We invited all German state and federal legislators as well as all state legislators in the United States to participate in the survey. The responses include 492 German state and federal legislators from all 16 German states (response rate: 20.4%) and 361 US state legislators from all US states except California and Louisiana (response rate: 5.6%). The German respondents are quite representative across the relevant socio-demographic and political variables such as party, gender and age, but federal representatives as well as certain states are underrepresented. We apply post-stratification weights based on party, gender and parliament for the German subsample. The US respondents deviate somewhat more from the population of all state legislators, particularly due to the tendency of Democrats and women to respond to surveys at higher rates than Republicans and men. The partisan deviation is also associated with regional distortions such as the under-representation of Southern legislators. To manage this, we apply post-stratification weights for this subsample based on party, chamber, region and gender. More detailed information about the representativeness of the two samples and the post-stratification weights is reported in Tables A1–A3 in the Supplementary Material online.

In contrast to Hibbing and Theiss-Morse’s early approach to capturing process preferences for either more ‘direct’ or more ‘institutional’ democracy using a single item asking whether ‘ordinary people like you and me’ or ‘elected officials’ should make political decisions (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002: 43), we seek to provide a more nuanced measurement by drawing on a scale composed of eight items (see Table 1). The items are intended to capture elite-centric preferences for responsible as opposed to responsive government (Donovan and Bowler Reference Donovan, Bowler, Bowler, Donovan and Tolbert1998) as well as people-centric preferences for majoritarian decision-making and the direct involvement of citizens in legislation. Given that existing representative institutions arguably have an elite-centric bias, we also include an item measuring status-quo preferences, asking whether respondents think that existing rules and procedures should not be contested. We expect response patterns to these items to reveal process preferences along a single dimension ranging from maximally people-centred (no elites, majoritarianism, legislation by citizens themselves) to maximally elite-centred (legislators as independent trustees, maintenance of status quo, no direct citizen participation). In our survey, respondents were asked to indicate their agreement with each of the eight items shown in Table 1 on a seven-point scale. Results from factor analyses and Cronbach’s alpha scores are presented in the analysis section.

Table 1. Overview of Items in Our Index Measuring People-centred versus Elite-centred Attitudes

To test Hypothesis 1 regarding differences between US and German legislators, we draw on descriptive results and t-tests for the two subsamples. To test the remaining hypotheses, we include several explanatory variables which are reported in Table 2. For Hypothesis 2a, we include a binary variable measuring whether the legislator was newly elected in 2021 or later to differentiate between shorter-serving and longer-serving legislators. Due to data constraints, Hypothesis 2b can only be tested for the German sample. We include a binary measure indicating whether legislators are serving at the state or federal level in the German models. For Hypothesis 2c, we include a binary measure of whether a legislator is a member of the majority party or coalition for both samples. Hypothesis 2d on the perceived seat safety of legislators can only be tested for the US sample due to data constraints. We measure perceived seat safety with the question ‘About what percentage of political offices in your area are considered “safe” or very certain your party will win?’ The answer categories are (1) 0–39%; (2) 40–60% and (3) 61–100%. Lastly, trust in other parties, the independent variable for Hypothesis 3, is measured for both German and US legislators using the question ‘How much of the time do you think you can trust members of the other party to do what is right for the country?’, with a seven-point answer scale from (1) Almost never to (7) Almost always.

Table 2. Overview of the Explanatory Variables

Source: Own data.

We include gender, age, education and self-reported ideology of the legislators on two dimensions as control variables. A detailed overview of the control variables and their question texts can be found in Table A4 in the Supplementary Material. For effect comparability, all continuous variables such as trust in other parties or the ideology measurements were standardized to range from 0 to 1.

To test our hypotheses, we calculate multiple ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models with our measurement of process preferences for people-centred or elite-centred democracy as the dependent variable. Since not all variables are available or applicable in both subsamples, and to capture any opposing effects of our measures across the distinct national contexts we study, we estimate separate models for the American and German data. For robustness, we present multiple specifications for the hypothesis tests. We estimate three OLS models per country: one including only the expected predictor variables; a second one adding control variables; and a third one adding party affiliation. Model diagnostics for all six models are reported in the Supplementary Material (Tables A5–A7).

Analysis: predictors of people-centred and elite-centred democracy preferences

To generate a measure of legislators’ positions on the continuum between preferences for people-centred and elite-centred democracy, we first ran an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) for eight individual items designed to capture process preferences. This results in a single factor with an eigenvalue above 1. As Table 3 shows, the four items expressing more elite-centred attitudes as well as the anti-elitism item and the items in support of citizen-centred democratic innovations have clear loadings above the common threshold of 0.4 in the expected directions. The item expressing a majoritarian sentiment also leans in the expected direction, albeit not as clearly.

Table 3. Results of the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Source: Own data.

Note: More detailed results of the EFA can be found in Table A10 in the Supplementary Material online. Only factors with a minimum eigenvalue of 1 were retained.

In order to increase comparability and reproducibility in future research, we proceed by using a simple index including all eight items, which reaches a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.65. We reverse the four items with negative loadings, calculate the mean agreement for each respondent across the eight items, and rescale the resulting index to range from 0 to 1.Footnote 4

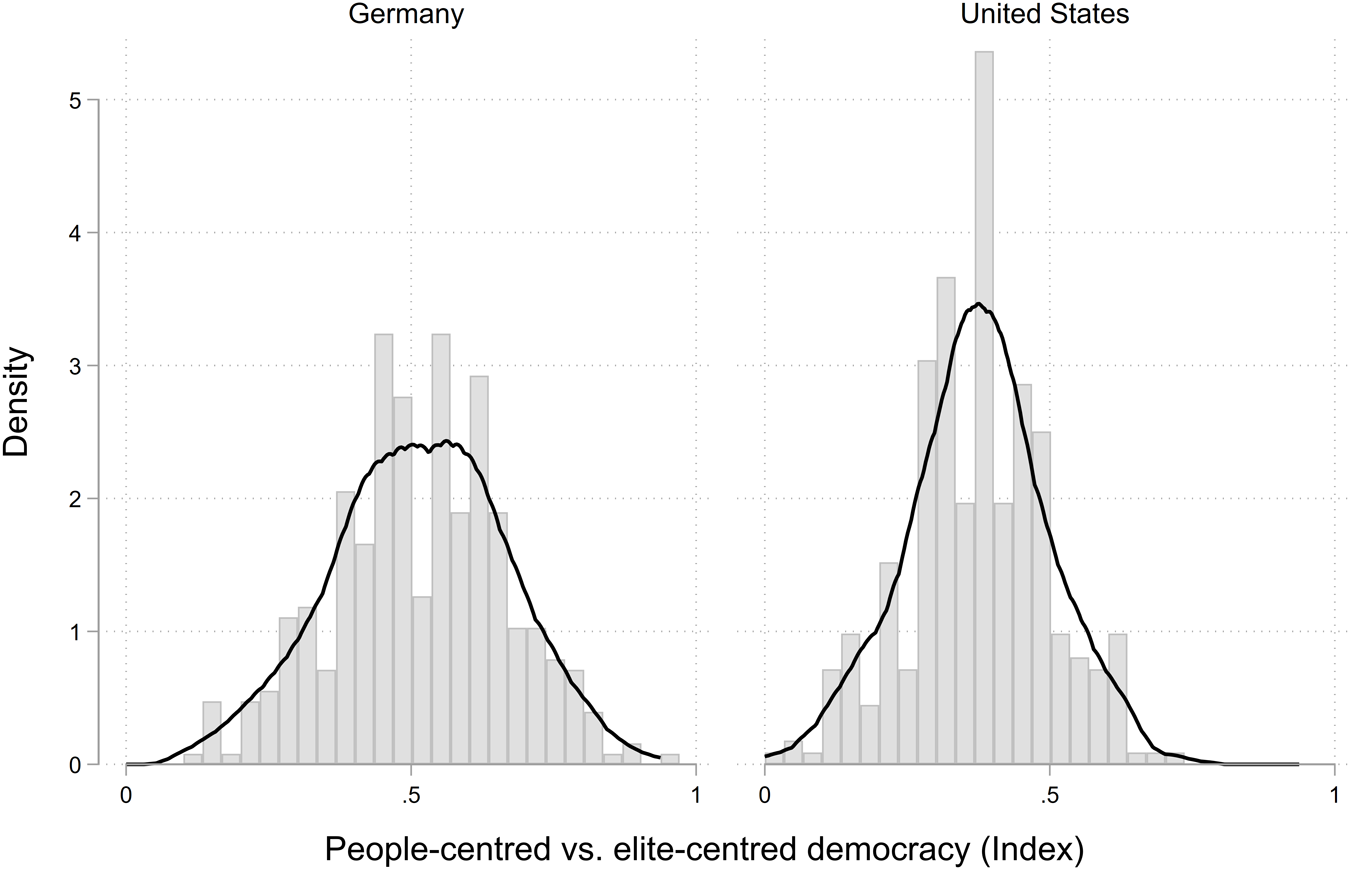

We begin by investigating the differences between US and German legislators as specified in the first hypothesis. We hypothesized that German legislators hold more elite-centred process preferences than legislators in the United States. The descriptive distribution of state legislators on this continuum in both countries, presented in Figure 1, provides evidence in favour of this. The difference in means between Germany (0.52) and the United States (0.37) is significant according to a Welch’s t-test (t(782.74) = 14.84, p < 0.001). Contrary to the citizen perception reported by Hibbing and Theiss-Morse back in 2002, in neither country do legislators show a strong leaning towards elite-centred democracy. While German state legislators show an almost normal distribution of preferences centred in the middle of the scale, we show that US legislators actually lean strongly towards the people-centred side of the index.

Figure 1. Distribution of State Legislators by Country

The difference in the distribution of preferences between German and US legislators is stark. While German legislators are centred around the mid-point of our scale, very few US legislators even approach that midpoint, and only a small percentage (12.5%) place themselves on the elite-centred side of the scale. Instead, US legislators seem to have established themselves as advocates for people-centred democracy. While the size of the difference revealed in our data is surprising, it is consistent with our argument that stronger polarization and arguably more intense power struggles between the parties in the United States would push US legislators away from supporting elite-centred democracy.

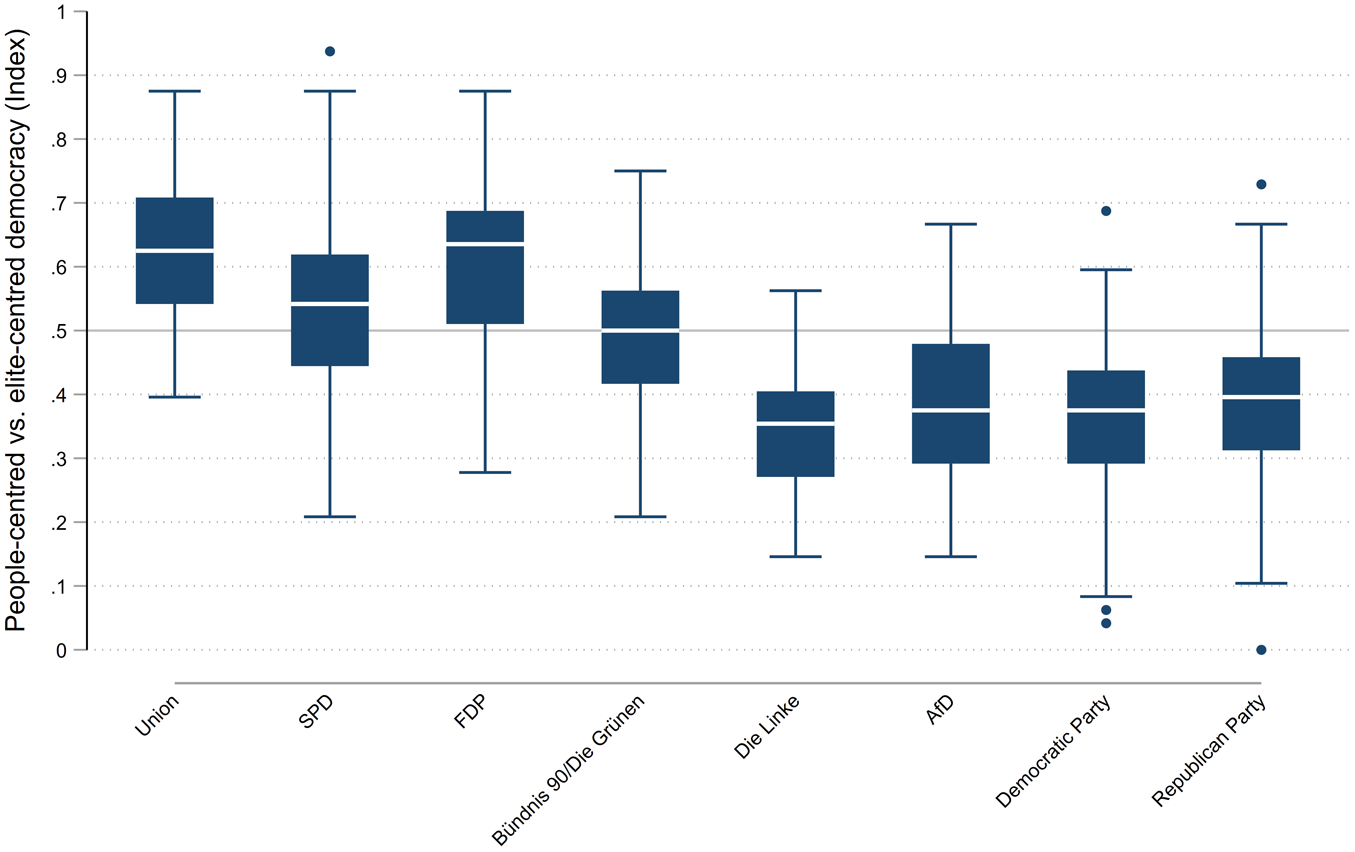

It is possible that these differences between Germany and the United States are caused by the dominant parties within each country. To determine if this is the case, we look at the distribution by party as shown in Figure 2. It demonstrates that there is a certain level of disagreement between the German parties with the centre-right parties CDU/CSU and FDP leaning clearly towards elite-centred democracy, the established centre-left parties SPD and the Greens centred around the midpoint of the index, and the ideologically extreme parties on the right (AfD) and on the left (Die Linke) of the political spectrum leaning strongly towards people-centred democracy. In the United States, on the other hand, there appears to be unity across the political spectrum, with both the Democratic and Republican parties established firmly on the people-centred side of our scale. Moreover, both the American parties are as people-centred in their orientation towards democracy as the parties on the two ends of the ideological spectrum in Germany. An analysis of variance confirmed these significant differences by party affiliation (F(7, 764) = 81.2, p < 0.001) and the post hoc pairwise comparisons underlined the particularly large difference between the German centre-right parties on one side and the US parties as well as the German challenger parties on the other side (see Table A11 in the Supplementary Material).

Figure 2. Distribution of Legislators by Party

Despite these clear tendencies for each party, there are wide and overlapping ranges of preferences, even for parties that are ideologically quite different from one another. This indicates that while party affiliation may partially explain the people-centred or elite-centred leanings of legislators, it is not the only factor that matters. To investigate what determines the elites’ process preferences, we ran separate OLS regression models for the United States testing Hypotheses 2a, 2c, 2d and 3, and for Germany testing Hypotheses 2a, 2b, 2c and 3.

Table 4 reports the results of three OLS regression models for the US subsample (Models 1–3). We estimate the effects of seniority (H2a), majority status and government control (H2c), electoral security (H2d), and trust in representatives from other parties (H3) on legislators’ orientations towards elite-centred (rather than people-centred) democracy in the United States. First, we find that being newly elected results in more people-centred views of democracy among legislators, providing support for the effect of seniority as formulated in Hypothesis 2a. Being in the legislative majority significantly increases a lean towards elite-centred democracy, thus confirming Hypothesis 2c. In line with Hypothesis 2d, perceiving most of the seats in the area to be safe for one’s party has an even larger and statistically significant effect on legislators’ preference for elite-centred democracy. Surprisingly, we do not find any effect of trust in the other party on process preferences and therefore have to reject Hypothesis 3 for the American case. Including the control variables barely impacts our core results (Model 2), and including party affiliation similarly has little impact (Model 3), which is in line with our descriptive findings for both US parties. Table A8 in the Supplementary Material reports models including a measure for legislative professionalism (Squire Reference Squire2024), showing that it has no effect on legislators’ process preferences, while the effects of our explanatory variables remain stable.

Table 4. Predictors of a Preference for Elite-centred Democracy in the United States

Source: Own data.

Notes: OLS models. Standard errors in parentheses.

+ p < 0.1,

* p < 0.05,

** p < 0.01,

*** p < 0.001. All variables range from 0 to 1; high values on the economic and cultural dimension indicate a right-wing/conservative position. Weighted by party, gender, house and region.

Table 5 presents the results for the German subsample in three similar models (Models 4–6), in which we estimate the effects of seniority (H2a), being a legislator at the federal level (H2b), majority status and government control (H2c), and trust in representatives from other parties (H3) on legislators’ process preferences. Here, we see a much bigger difference between the models and, looking at the adjusted R 2, a significant portion of the variance in legislators’ elite- or people-centred democratic attitudes appears to be explained by party affiliation. This is consistent with our descriptive results.

Table 5. Predictors of a Preference for Elite-centred Democracy in Germany

Source: Own data.

Notes: OLS models. Standard errors in parentheses.

+ p < 0.1,

* p < 0.05,

** p < 0.01,

*** p < 0.001. All variables range from 0 to 1; high values on the economic and cultural dimension indicate a right-wing/conservative position. Weighted by party, gender and parliament.

First, we see the expected effect of being newly elected on leaning towards a people-centred view of democracy, as stated in Hypothesis 2a. Furthermore, the results confirm Hypothesis 2b, showing that federal legislators in Germany lean more towards elite-centred democracy. However, both of these effects are only significant when controlling for party (Model 6). With regard to the effect of being in the majority coalition, as specified in Hypothesis 2c, Models 4 and 5 reveal a strong and highly significant effect of being part of the majority coalition towards a more elite-centred democracy preference, thus confirming the hypothesis. This coefficient is smaller in Model 6, which controls for legislators’ party affiliation, but it is remarkable that it remains significant at all, given the collinearity between being in opposition and party affiliation (since the AfD is the most people-centred party in Germany and sits exclusively in the opposition).

Turning to Hypothesis 3, trust in other parties – understood as an indicator of low affective polarization – has a strong and highly significant effect towards the elite-centred view in Models 4 and 5, but this effect disappears entirely when controlling for party affiliation (Model 6). Given that the effect seen in Models 4 and 5 seems to be mainly driven by the low trust of AfD legislators, we have to reject Hypothesis 3 for the German case. With regard to party affiliation, there are strong and highly significant effects confirming our descriptive results, with legislators from AfD and Die Linke being the most people-centred, while the legislators from the centre-right CDU/CSU and FDP have the highest preference for elite-centred democracy. Table A9 in the Supplementary Material presents results from a model including only German state legislators for comparability with our US sample, which contains only US state legislators, which confirm our primary findings.Footnote 5

Overall, our results show the role of instrumental motivations – particularly majority status and proximity to power – in shaping legislators’ attitudes to democracy. In regard to Hypothesis 2a, the results in Germany and the United States show that longer-serving legislators indeed favour elite-centred democracy more than newly elected legislators. Hypothesis 2b, which could only be tested for the German sample due to data constraints, is also confirmed in our analysis: federal legislators are more likely to support elite-centred democracy than state legislators. For Hypothesis 2c, belonging to the majority party or coalition leads legislators to favour elite-centred over people-centred democracy in both countries studied, confirming the hypothesis.

Moreover, we find support for Hypothesis 2d, as US legislators who perceive most of the seats in their area to be safe for their party have a higher preference for elite-centred democracy. This hypothesis could only be tested for the US sample. Contrary to our expectations, we do not find a significant effect of trust in other parties on legislators’ preferences in either Germany or the United States, leading us to reject Hypothesis 3. Thus, we find that instrumental motivations do play a role for the kind of democracy legislators prefer, even though we cannot observe an association between affective polarization and legislators’ process preferences.

Discussion and conclusion

How do political elites, and legislators in particular, view democracy? Do they prefer elite-centred or people-centred decision-making processes? Do legislators’ process preferences differ between countries, and what determines this? In this paper, we answer these questions by drawing on original data gathered in 2022 and 2023 from political elites in Germany and the United States. Our paper contributes to the debate about ‘process preferences’ that was sparked by Hibbing and Theiss-Morse’s seminal book in 2002. At the same time, we go beyond Hibbing and Theiss-Morse’s contribution by (1) studying legislators’ process preferences directly (whereas these authors only looked at citizens' perceptions of them), and (2) introducing a more nuanced and reliable measure, creating a scale derived from a set of survey items intended to capture elite- versus people-centred process preferences among legislators.

Our findings reveal that the factors which shape legislators’ process preferences are remarkably similar across different national contexts, electoral systems and party systems. However, we also find that the orientations legislators hold towards democracy – their leanings towards or away from people-centred democratic processes – differ cross-nationally because of the way the factors we examine vary in different national contexts. Even though legislators in Germany and the United States are facing similar trends such as the rise of populism and polarization, their beliefs about how democracy should function do not seem to respond to these trends in identical ways. Indeed, our findings can be helpful for predicting different outcomes across legislators who face different structural contexts. For example, we reveal that while people-centred democratic preferences are strong only among the most right- and left-leaning parties in Germany, and German legislators overall remain more balanced in their position on the elite- to people-centred democracy scale, US legislators from both major political parties express more people-centred than elite-centred process preferences.

What factors explain legislators’ elite- or people-centred process preferences? Recent research in several western democracies including Germany has found that legislators’ characteristics and ideology do not predict their preferences for citizen- versus elite-driven governance (Mongrain et al. Reference Mongrain, Junius and Brack2024). With our paper, we instead focused on instrumental motivations as determinants of legislators’ process preferences, hypothesizing that legislators with higher status and better access to power and resources benefit from existing power structures and institutions and will therefore be more likely to have a preference for maintaining them.

In accordance with our expectations, we found that legislators’ seniority, experience and majority party status are associated with more elite-centred process preferences. Specifically, legislators who were more recently elected are less likely to hold elite-centred preferences than legislators who have served a longer time in office. For Germany, our data also show that having ascended to the federal legislature promotes a more elite-centred view of democracy than serving only at the state level. Most importantly, we reveal that two indicators of legislative power – being in the majority party or government coalition and (in the United States) being in a context where the seats in one’s area are viewed as electorally secure for one’s party – inclines lawmakers towards a preference for elite-centred democracy.

These findings confirm the results of earlier studies by showing that holding power continues to generate a stronger preference for elite-centred democracy among legislators, even in systems as different as those of the United States and Germany (Bowler et al. Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2002; Gherghina et al. Reference Gherghina, Close and Carman2023; Gilljam et al. Reference Gilljam, Persson and Karlsson2012; Junius et al. Reference Junius, Matthieu, Caluwaerts and Erzeel2020; Önnudóttir Reference Önnudóttir2016). Consistent with our theory, when legislators hold majority power in a governing body and when they believe their position is more electorally secure and that they will continue to hold power, they have incentives to protect that institution’s power – promoting a more elite-centred orientation towards democracy – and have less need to worry about the immediate whims of voters in order to maintain their position.

How could the different contextual conditions in Germany and the United States moderate the effect of instrumental motivations on process preferences? To begin with, US legislators in both major parties face more instability in their access to and expected hold on power than do legislators in Germany’s most prominent parties. Shifts in power between the parties regularly occur in America’s governing bodies, and legislative and executive power is often divided between parties. Divided power can occur at the federal level in Germany (with the Bundesrat as the upper and the Bundestag as the lower house), but not at the state (Land) level. Moreover, coalition governments are essentially unheard of in US legislatures, where power is almost universally held by a single party after each election.

In sum, in the United States there is uncertainty regarding which party will hold institutional power from year to year, and certainty that when one’s party is in the minority, there will be minimal access to the levers of power. This should leave US legislators more wary of elite-centred democratic processes and potentially more likely to favour people-centred democracy in an effort to strengthen their electoral chances. By contrast, German legislatures demonstrate greater stability in terms of which parties hold institutional power over time, ensuring that the head of government will be affiliated with the legislative majority rather than operating externally to the governing coalition. Furthermore, the fact that governing majorities are generally coalition-based provides a larger number of parties with access to the governing coalition. These features seem to lay the groundwork for a more elite-centred view of democracy among many German legislators.

What implications could our findings have for future developments in democratic governance? To the extent that legislators holding people-centred process preferences face greater challenges in governing effectively than legislators with more elite-centred preferences do, our findings suggest some challenges ahead in satisfying the process preferences of citizens while also providing them with good governance. If people-centred legislators are unwilling to protect and use institutional power, they may have more difficulty governing effectively, which could produce citizen dissatisfaction and decrease trust in government. In particular, our findings suggest that legislative bodies undergoing substantial turnover and party power shifts would contain increasingly people-centred legislators who are more willing to contest existing democratic rules and procedures, less willing to engage in behind-closed-doors policy-making, and more likely to follow the swings of public opinion when governing. An examination of the US Congress in recent yearsFootnote 6 seems consistent with this prediction and consequential for democracy in the United States. By contrast, German legislators from the parties that regularly form governing coalitions tend to hold more elite-centred process preferences and may be better able to govern efficiently and effectively. Having said this, there are clearly a number of other relevant determinants of policy decisions and outcomes to consider besides legislators’ process preferences, and our reflections on the likely effects of the latter on democratic governance must remain speculative here.

Moreover, our surveys and findings have clear limitations. First, it would have been desirable to survey US legislators at the federal as well as the state level and to achieve a higher response rate in US states in order to be able to test differences in attitudes between the two levels. Second, we do not have data on the electoral security of legislators’ seats in Germany (which is more difficult to measure in this context), meaning that we could only test the respective hypothesis for the US case. In addition, longitudinal data would have been ideal for studying the development of legislators’ process preferences and the way they compare to citizens’ preferences over time. Regrettably, neither of these research desiderata are likely to be achieved in the near future, especially as US legislators are becoming increasingly difficult to survey – a trend that is exacerbated by the backlash against American universities. At the same time, and in light of recent backsliding processes in the United States and other democracies, understanding and comparing political elites’ attitudes vis-à-vis democratic institutions and procedures seems more important than ever. We therefore look forward to future work building on our findings to explore the extent to which the factors we reveal as shaping democratic process preferences among US state legislators and German legislators apply at other levels of government and in different national contexts.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2026.10033.

Data availability

The data used in this paper are published and freely available in the Harvard Dataverse. See the German Legislator Survey (2022) at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GUVA5P and the American Legislator Survey (2023) at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/3H1YYH.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank participants of panels at the DVPW conference 2024 and APSA 2024 as well as workshops at JGU Mainz and at the Ash Centre at Harvard University for comments and suggestions. Particular thanks go to Peter Enns, Christopher Ojeda, Kris-Stella Trump, Lars Vogel and three anonymous reviewers for Government and Opposition.

Financial support

This work was supported by the DFG as project number 462314147.

Disclosure statement

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.