Introduction

The absence of an electoral connection at the European Union (EU) level is one of the most widely held assumptions in the scholarship on the European Parliament (EP) (Hix & Høyland, Reference Hix and Høyland2013; Ripoll Servent, Reference Ripoll Servent2018). While what is meant by electoral connection varies significantly (Carrubba, Reference Carrubba2001; Hix et al., Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2003, Reference Hix and Marsh2007; Lo, Reference Lo2013; Schäfer & Debus, Reference Schäfer and Debus2018), the common understanding would point to the weakness of congruence between public opinion and EU politics, the absence of electoral mandatingFootnote 1 and the limited electoral accountability (De Vries, Reference De Vries2018). In the words of Hix and Marsh: ‘citizens do not primarily use European Parliament elections to express their preferences on the policy issues on the EU agenda or to reward or punish the MEPs or the parties in the European Parliament for their performance in the EU’ (Reference Hix and Marsh2007, p. 507). This assumed absence of an electoral connection is a cause of serious normative concern, has been labelled a ‘failure of parliamentary representation’ (Farrell & Scully, Reference Farrell and Scully2007) and arguably contributes to the democratic deficit of the EU (Føllesdal & Hix, Reference Føllesdal and Hix2006).

Despite the widespread nature of this assumption and its clear individual accountability dimension, we still know very little about the extent to which legislative performance matters for EU citizens in their EP vote choices. Especially in member states allowing voters to cast a personal ballot in EP elections, preference votes could serve as a democratic accountability tool.

The article addresses this gap by investigating the extent to which differing levels of members of the European Parliament's (MEPs) parliamentary activity and visibility lead to personal vote gains and more success in the intra‐party competition in three EP elections that took place between 2004 and 2014. The central research question of this study is how does legislative performance influence the preference vote shares of MEPs? Legislative performance is defined here in terms of a MEP's ability to influence the policies of the European Parliament, which in turn depends on their productivity levels in drafting reports, asking parliamentary questions and delivering speeches. I argue that legislative performance is more likely to lead to electoral rewards for the candidates of parties assigning high salience to the EU and that co‐partisan incumbent competition can also play a moderating role in the electoral connection.

The fact that party competition provides more meaningful choice on European integration and that EU issue voting is more present in both national and EP elections than in the past (De Vries, Reference De Vries, Cramme and Hobolt2015) indicates that party–voter linkages at the EU level might not be as weak as previously considered. Similarly, institutional and societal developments suggest the need to reconsider the standard view regarding the weak or non‐existent EP electoral connection.

Thus, in some EU member states, the overall news coverage of individual MEPs has increased from one election to another (De Vreese et al., Reference De Vreese, Banducci, Semetko, Boomgaarden, Marsh, Schmitt and Mikhaylov2007, p. 36; Gattermann, Reference Gattermann2020, p. 100), while in recent years the media coverage of the quantitative legislative output of MEPs has also risen substantially (Sigalas, Reference Sigalas2011), favoured by the development of parliamentary monitoring websites such as VoteWatch.Footnote 2 The coverage often focuses on ranking MEPs in terms of their speeches, plenary voting attendance or participation in committee activities. Such information can make voters more interested in rewarding MEPs based on their activity, particularly in countries where preferential voting systems are used.

A favourable institutional development is the increase in the proportion of European deputies elected in this manner: the majority of EU member states draw on some form of preferential voting rules for EP elections, including 10 of the 13 countries which joined the EU since 2004 (Hix & Hagemann, Reference Hix and Hagemann2009, p. 44; Renwick & Pilet, Reference Renwick and Pilet2016, p. 177).

In these EP elections organized under open or flexible list Proportional Representation (PR), there is a significant cross‐country variation in the extent to which voters opt for a candidate as opposed to just voting for the party list. Thus, there are countries where around three out of four voters of a party regularly choose a candidate (e.g., Slovenia, Denmark, Slovakia and Croatia) while in others, like Bulgaria and Austria, typically only one out of four voters do so (Däubler et al., Reference Däubler, Chiru and Hermansen2022). Whereas electoral system incentives (e.g., thresholds in flexible list systems) probably play a key explanatory role in this outcome, I argue that individual legislative performance could also matter for vote choice, especially if voters are primed by parties, which assign high salience to the EU, to pay attention to these aspects. Moreover, while incumbent co‐partisan competition is likely to diminish the value of the incumbency cue for voters, it could make MEPs more likely to campaign on their performance in the EP to differentiate themselves from their MEP colleagues. Taken together, these aspects suggest that in a context in which low clarity of responsibility prevents European voters from rewarding or sanctioning parties for EU policy outcomes, individual legislator accountability might be a more viable alternative.

To test these expectations, I draw on an original dataset that combines candidate and electoral data from three rounds of EP elections held between 2004 and 2014, under open or flexible list rules with information on individual legislative activity (i.e., number of reports, parliamentary questions, and speeches), and on other aspects that facilitate productivity (e.g., acquiring EP or committee office).

The results show that parliamentary activities generally have no robust impact on electoral performance, except for report writing, which is associated with a higher share of preference votes, but only for incumbents of parties that assign high salience to the EU. While MEPs win a higher share of preference votes when they face no, or limited, co‐partisan incumbent competition, this factor does not moderate the electoral connection.

Considering how legislative performance affects MEPs’ vote gains contributes to moving the extant literature on voting behaviour in EP elections beyond the debate about the second‐order elections (SOE) model. This model claims that voters choose whom to vote for in EP elections based on preferences from the domestic arena and that because less is at stake in these elections, citizens will vote sincerely for small parties, strategically punish the government, or not bother to vote at all (Reif & Schmitt, Reference Reif and Schmitt1980). The SOE model remains the prevalent frame for analysing voting behaviour in EP elections despite the observational equivalence of some of its predictions (e.g., are governments punished in these elections because of bottom‐up protest voting or because of top‐down party mobilization choices? – see Weber, Reference Weber2007) or the fact that subsequent research has shown that in these elections at least some voters base their choices on EU‐related factors (e.g., the EU performance of national parties; Clark & Rohrschneider, Reference Clark and Rohrschneider2009) or on information about the parties’ EU positions (Hobolt & Wittrock, Reference Hobolt and Wittrock2011). The individual accountability dimension and the conditions under which certain voters might rely on information about incumbent MEPs in making their voting decisions is something missing from both approaches, which is directly addressed in this article. The research has also the potential to further elucidate the apparent trade‐off national parties face between nominating well‐known national politicians, such as former ministers who are more popular and can win votes, and nominating EP incumbents who have demonstrated they can achieve policy goals in Brussels (Gherghina & Chiru, Reference Gherghina and Chiru2010; Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Meserve and Bernhard2015). Moreover, it can give academics and policy‐makers a clearer understanding of the likely effects of further personalization of EP electoral rules on the electoral connection in member states that use closed list PR.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. The introduction is followed by a review of the relevant literature on electoral consequences of legislative behaviour in the EP and a presentation of the main hypotheses of the study. The next section offers an overview of the data and research design. I then discuss the results of the multivariate analyses and robustness tests. The conclusion discusses the implications of the main findings and points to further avenues of research.

Electoral rewards of EP activities and the moderating role of EU salience and incumbent competition

To date, no study has tested longitudinally whether the preference vote shares of incumbent MEPs vary with their degree of legislative effort or whether citizens reward or punish legislators for their achievements in the EP. This study follows this direction and tests whether levels of legislative productivity are rewarded by voters and whether this is moderated by parties’ EU salience and the degree of incumbent co‐partisan competition.

The scholarship on the determinants of preference vote usage, the candidate characteristics that attract preference votes and the intra‐party competition dynamics that preferential voting generates, has been expanding considerably in recent decades (André et al., Reference André, Depauw, Shugart and Chytilek2017; Dodeigne & Pilet, Reference Dodeigne and Pilet2021; Isotalo et al., Reference Isotalo, Mattila and von Schoultz2020; Put et al., Reference Put, von Schoultz and Isotalo2020; Schoultz & Papageorgiou, Reference Schoultz and Papageorgiou2021; Wauters et al., Reference Wauters, Verlet and Ackaert2012). However, research on preference voting in the context of EP elections has been extremely scarce. Däubler and Hix (Reference Däubler and Hix2018) have comprehensively mapped the electoral rules used in preferential list systems in these elections and the extent to which preference votes make a difference for who gets elected, that is, the empirical flexibility of lists.

Somewhat more attention has been devoted to the electoral consequences of EP list attributes and candidate characteristics and of EP legislative behaviour. Hobolt and Høyland (Reference Hobolt and Høyland2011) were the first to illustrate that who the candidates are matters for the vote share of party lists in European elections. Analysing data from six EP elections, the authors showed that parties which nominate highly experienced national politicians tend to be rewarded by voters. In a study focused on the Dutch 2014 EP elections, Gattermann and De Vreese (Reference Gattermann and De Vreese2017) showed that voters’ evaluation of the lead candidates influences their party choice.

Sigalas (Reference Sigalas2011) investigated how the parliamentary activities of MEPs in the sixth term influenced their re‐election in 2009 and concluded that the number of reports written and a higher percentage of attendance at plenary sessions are the most important predictors of winning a new mandate, but his analyses do not differentiate between MEPs who stood in the election and those who did not.

In a study that focused on a sample of German MEPs, Frech (Reference Frech2016, p. 71) showed that their re‐election probability is influenced by membership in powerful EP committees and, to a smaller extent, by the number of reports they have drafted. Van Thomme et al. (Reference van Thomme, Ringe, Victor, Kaeding and Switek2015) analysed how parliamentary activities and leadership positions in the EP influenced the re‐election of those MEPs who were re‐nominated at the 2014 elections. This study did not account for the salient mediating factor that is the list position of the MEPs. The authors found that MEPs who had drafted a larger number of reports and those who had been party group leaders or leaders of an intergroup are more likely to win a new mandate (van Thomme et al., Reference van Thomme, Ringe, Victor, Kaeding and Switek2015, p. 339).

A recent study has shown that productivity‐based retrospective voting is a feature of EP elections (Sorace, Reference Sorace2021). Analysing how MEPs’ legislative productivity influences retrospective voting in the 2019 EP elections, the author concluded that voters reward party lists that include MEPs with higher levels of plenary voting attendance and more rapporteurs and committee chairs, while the nomination of MEPs who have delivered many speeches seems to decrease party support. Moreover, the positive effect of legislative productivity appears higher in countries using electoral systems which encourage a personal vote and for voters who paid more attention to the election campaign.

Why would higher levels of legislative productivity be rewarded by voters in EP elections?

A growing body of research indicates that legislative productivity can help parliamentarians increase their personal vote, existing evidence pointing to the importance of sponsoring private member bills (Abel & Navarro, Reference Abel and Navarro2019; Box‐Steffensmeier et al., Reference Box‐Steffensmeier, Kimball, Meinke and Tate2003; Bowler, Reference Bowler2010; Däubler et al., Reference Däubler, Bräuninger and Brunner2016; Marangoni & Russo, Reference Marangoni and Russo2018), parliamentary questions and interpellations (Däubler et al., Reference Däubler, Christensen and Linek2018) and reports and speeches (Abel & Navarro, Reference Abel and Navarro2019; Marcinkiewicz & Stegmaier, Reference Marcinkiewicz and Stegmaier2019). This research, however, is mostly focused on national or state legislatures, and only very few studies have analysed how legislative productivity influences re‐election to the EP.

Based on a comprehensive analysis of the effect of legislative performance in the seventh (2009–2014) and eighth (2014–2019) terms of the EP on the legislators’ reselection and re‐election odds, De Connick (Reference De Connick2021, p. 182) concludes that MEPs elected from party‐centred systems have a higher chance of being re‐nominated and re‐elected the more reports they author. Her analyses indicate that in candidate‐centred systems, higher levels of legislative efforts do not increase the MEPs’ likelihood of re‐election. The importance of drafting reports for the re‐election probability of MEPs was also corroborated by other studies, taking either a single country focus, such as Frech's study (Reference Frech2016) of German MEPs, or a comparative perspective (van Geffen, Reference van Geffen2018).

The MEP that drafts the report has the opportunity to shape the position of the entire EP on the piece of legislation that is being considered. They meet with stakeholders, receive expert advice and negotiate with representatives of the Council and the Commission in trilogues (Ripoll Servent, Reference Ripoll Servent2018; Roederer‐Rynning & Greenwood, Reference Roederer‐Rynning and Greenwood2017). Especially for reports drafted under the ordinary legislative procedure, the influence of the rapporteur on European legislation is sizable, and this is also reflected in the way in which reports are allocated. Thus, the committee group coordinators of each European Party Group bid against each other and after winning the report the successful coordinator nominates as rapporteur an MEP from their delegation who has the loyalty, experience and expertise required (Yoshinaka et al., Reference Yoshinaka, McElroy and Bowler2010; Daniel, Reference Daniel2015; Chiou et al., Reference Chiou, Hermansen and Høyland2020). Therefore, MEPs who have drafted reports would be able to use them as a powerful argument for their re‐election in their campaigns. Not only does report writing indicate that they are competent, skilful politicians, trusted by other legislators, but during campaigns these MEPs will also be able to point to concrete policy outcomes resulting from their reports that benefit the lives of European citizens in general and their constituents in particular. Even the writing of own initiative reports that do not have immediate legislative consequences can be advertised by MEPs as a form of agenda setting in the same way as national legislators use the initiation of private member bills in their re‐election campaigns.

Previous research has shown that speech making in the EP has a strong national dimension. Thus, MEPs use speeches for position taking in line with national divisions over redistribution at the EU level to take stances on EU integration and to explain vote defections from their European Party Group position when such a defection is motivated by alignment with their national party preferences (Proksch & Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2010; Slapin & Proksch, Reference Slapin and Proksch2010). The latter is relevant for two aspects. First, it shows that unlike in most national legislatures, access to the floor in the EP is less constrained for rebels. Second, it indicates that MEPs appeal directly to their national party gatekeepers through speeches, as the discussed effect is stronger for those national parties which have centralized candidate selection for EP elections (Slapin & Proksch, Reference Slapin and Proksch2010).

Beyond party leaders, speeches in which MEPs grandstand about their allegiance to the national interest and the preferences of their national voters can also serve as a vote‐gaining mechanism if at least some voters learn about them via national media or the MEPs’ own communication efforts on social media or other platforms. Of course, the opportunity to make speeches is not equally distributed among MEPs, being dependent on the size of their European Party Group (EPG), whether they hold a leadership position and their degree of favour with the leaders of their EPG (Ripoll Servent, Reference Ripoll Servent2018).Footnote 3 The extant research indicates that how active MEPs are with respect to speech making does not seem to matter for their re‐election (Sigalas, Reference Sigalas2011; van Geffen, Reference van Geffen2018; De Connick, Reference De Connick2021).

While access to reports and speeches is constrained and costly, MEPs are much freer in their usage of parliamentary questions and oftentimes these are used for territorial representation purposes (Brack & Costa, Reference Brack, Costa and Costa2019). Thus, many of the questions submitted by MEPs deal with issues from their electoral districts or regions, including inquiries about European funding available for local infrastructure projects or for relief following natural disasters and questions about the problems of individual constituents or the impact of proposed EU legislation on local businesses (Chiru, Reference Chiru2022, p. 286). The varied beneficiaries of these questions illustrate a vote‐winning strategy that could be targeting different types of voters and organized interests and that it is easily transformable into content for electoral advertising in local or regional media. Even if these questions do not result in a positive outcome, they can still send voters the cue of a representative who works hard and looks after the welfare of their constituency. Similar to parliamentary speeches, the volume of submitted parliamentary questions does not seem to matter for MEPs’ re‐election in the few studies that have considered this indicator (Sigalas, Reference Sigalas2011; De Connick, Reference De Connick2021). Despite these mixed findings, I still hypothesize that legislative productivity would increase preference vote shares but test this hypothesis using three different indicators.

H.1: MEPs achieving higher levels of legislative productivity will receive higher shares of preference votes.

One caveat to H.1 is that higher levels of productivity in the EP are less likely to be rewarded by voters who do not care about the European Union and are not primed by their parties to pay attention to what happens in Brussels and Strasbourg. The overall level of politicization of the EU has increased dramatically in recent decades, marking the end of the ‘permissive consensus’ surrounding European integration (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009). The politicization has impacted the composition of the EP, with the arrival of more and more Eurosceptic MEPs, and has also affected the behaviour of mainstream MEPs (e.g., they become more disloyal towards their EPG principal in proximity to national elections – see Koop et al., Reference Koop, Reh and Bressanelli2018). Politicization could increase voter and media attention to EP politics and facilitate the development of a European electoral connection, but it is highly unlikely that such an effect would be homogeneous. First, the degree of politicization of the EU varies across countries, depending on the national benchmarking of citizens’ attitudes towards the EU (De Vries, Reference De Vries2018) and the extent to which the EU issue can be juxtaposed with a demarcation or identity cleavage (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012). Second, the effect is also likely to vary within countries depending on whether individual parties choose to mobilize or demobilize voters around domestic as opposed to European issues in EP election campaigns (Weber, Reference Weber2007). When it comes to individual preference votes, the choice of such mobilization strategies in EP elections could potentially limit the scope of a personal vote for MEPs by priming voters to pay attention to the incumbents’ domestic political records, as opposed to EP activity, or simply to endorse the list ranking proposed by the party.

While the ability to measure such strategies directly would require comprehensive, party‐level data about campaign topics and the intensity of campaigning for EP elections compared to national elections, I argue that the overall level of salience a party assigns to European integration is much more likely to condition the scope of a personal vote for MEPs. Thus, voters of parties which assign low salience to the EU are less likely to learn about legislative activities in Brussels and Strasbourg because such aspects will not be disseminated by their party between and during electoral campaigns. Moreover, it is more likely that these parties would attempt to mobilize voters based on domestic issues and would not prime their voters to consider the legislative performance of their MEPs in their vote decisions. A special case here is that of Eurosceptic parties, which naturally assign very high salience to the EU but whose MEPs rarely attempt to shape policy‐making in the EP. Nevertheless, Eurosceptic MEPs frequently engage in speech making to denounce the faults of the European integration project and they are some of the most avid users of parliamentary questions, frequently to address national and constituency topics or simply to obstruct the Commission (Brack & Costa, Reference Brack, Costa and Costa2019; Proksch & Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2011). Speeches and oral questions by Eurosceptic MEPs, like the exchange between Nigel Farage and Herman van Rompuy, the then president of the European Council, can become viral and be rewarded by Eurosceptic voters even if they disapprove overall of the EP.

H.2: MEPs achieving higher levels of legislative productivity will receive higher shares of preference votes if they run for parties which assign high salience to European integration.

Incumbent intra‐partisan competition is also likely to act as a moderating factor. When an MEP is the sole incumbent running on their party list in a district, they can singularly claim EP‐specific expertise and know‐how and attract a large share of the preference votes of those party supporters who value competence and seniority or are more interested in EU affairs. Moreover, in such a situation, the MEP would be the only candidate of their party who can personalize their campaign with legislative achievements inside the EP, such as videos of plenary speeches, records of reports drafted on highly significant policy matters or evidence of sustained scrutiny efforts via parliamentary questions. All of these could function as a cue for a high‐quality or hard‐working legislator that could be picked up even by party sympathizers who pay less attention to the campaign. Incumbent co‐partisan crowdedness would significantly reduce both types of competitive advantage. Nevertheless, even if voters have little knowledge about or interest in EP activity records, the higher visibility and associated better name recognition of an incumbent is likely to generate significantly more preference votes in the absence of other co‐partisan incumbents running on the same list. In other words, rewards for EP experience and activity are likely to be divided among the parties’ incumbents: where multiple MEP incumbents from the same party compete against each other in the same district, the value of the incumbency cue and of the record of legislative activity will diminish for voters and, with it, also the share of individual preference votes.

H.3: MEPs achieving higher levels of legislative productivity will receive higher shares of preference votes, the fewer co‐partisan incumbents running in the same district.

Apart from the hypothesized effects, I also control for MEPs’ acquiring EP or committee office, their list rank at the selection stage, ministerial experience, number of EP terms served, gender and age. Acquiring a mega‐seat, such as EP vice‐president or committee chair, can increase an individual legislator's impact on the internal politics of the EP or on specific sectoral policies. This is an achievement that MEPs can then advertise in their quest for preference votes. Leadership positions could also facilitate higher legislative productivity, given the privileged access of EP leaders to reports and speaking time (Yoshinaka et al., Reference Yoshinaka, McElroy and Bowler2010; Høyland et al., Reference Høyland, Hobolt and Hix2019). Holding an EP leadership position might also be an electoral asset given the media coverage that it generates. The lack of a positive effect of legislative productivity on MEPs’ re‐election odds could be driven by a lack of interest from national news media in covering such efforts. Indeed, in an analysis of the visibility of MEPs in the news in five member states over 25 months, Gattermann and Vasilopoulou (Reference Gattermann and Vasilopoulou2015) found a negative effect for MEPs investing a significant amount of time in asking parliamentary questions and attending plenary votes, while drafting a high number of reports did not increase coverage either. Unsurprisingly, the only activity associated with a (very small) positive effect was speech making. Instead, the study found considerably higher levels of media visibility for MEPs who served as committee chairs or were members of the EP bureau. Consistent with this finding, previous research has shown that MEPs serving as European party group leaders or inter‐group chairs have a higher probability of re‐election, which can presumably be attributed to their higher visibility (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Ringe and van Thomme2016).

The list rank position often functions as a cue of candidate quality: earlier studies have shown that candidates nominated higher up on the list do receive more preference votes (Däubler et al., Reference Däubler, Bräuninger and Brunner2016). Since this cue is usually stronger for the first placed candidate (Marcinkiewicz & Stegmaier, Reference Marcinkiewicz and Stegmaier2015), I also control for that position with a dummy variable. MEPs who have ministerial experience will probably attract a higher level of preference votes given their greater name recognition (Hobolt & Høyland, Reference Hobolt and Høyland2011). EP seniority was shown to increase the media visibility of MEPs (Gattermann & Vasilopoulou, Reference Gattermann and Vasilopoulou2015), and it could hence lead to a higher share of personal votes.

Data, operationalization of variables and methods

While, overall, EP elections can be considered a least likely case (Gerring, Reference Gerring2007) for finding evidence of an electoral connection due to the reasons discussed above, within them those elections organized under preferential voting systems should amount to a most likely case for discovering evidence of electoral consequences of EP legislative performance.

The dependent variable of this study is the percentage of preference votes received by an MEP relative to all preference votes cast for candidates of her party in the district.Footnote 4 Similar to previous research (Däubler et al., Reference Däubler, Bräuninger and Brunner2016), this operationalization assumes that voters first select a party and then choose among candidates within the party list to cast their preference vote(s).

Because the central focus of this paper is on how legislative performance influences the preference vote shares of MEPs, I control for the legislators’ preference vote shares at the previous election by using the lagged dependent variable (Wilkins, Reference Wilkins2018).Footnote 5 Adding this control results in the exclusion of the 2004 elections conducted under preferential voting rules in eight new member states as they did not participate in the 1999 contest and also in the exclusion of the data from the countries which used both closed list PR and preferential voting systems during the period analysed (Estonia and Greece).Footnote 6

The choice of legislative activities that are used to test the hypotheses was influenced not only by the findings of the previous literature but also by the desire to capture MEP performance through both policy‐making activities and more visible and mediatized roles. The weak correlation coefficients between the three types of activities indicate that they are indeed performed by different sets of MEPs (see Table A2 in the online Appendix for a correlation matrix of all variables). Instead of the raw counts of reports, speeches, and parliamentary questions, I include in the model the natural logarithms of the number of each such activity, since it is likely that the marginal effect of an additional unit of each of these activities is not constant but decreases with the number of reports drafted, questions submitted, and speeches made.Footnote 7

The operationalization of most independent variables and controls is straightforward, but I detail it here for four slightly more complex variables. The list rank at selection stage was standardized on a 0–100 scale to allow comparison between lists of different lengths, in which 0 indicates nomination on the first list position and 100 indicates nomination at the bottom of the list (Marcinkiewicz & Stegmaier, Reference Marcinkiewicz and Stegmaier2015). EP leadership position is a dichotomous variable indicating whether the MEP has been a member of the leadership bodies of the Parliament or European Party Group in the past term. EP committee leadership position is another dummy, coded 1 if the MEP has served as committee chair or vice‐chair in one of the EP's permanent committees in the past term. Ministerial experience is a dummy indicating whether the MEP has been a member of the national (or federal) cabinet in the past. EU salience, used to test H.2, is based on the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny and Vachudova2022) item that asks about ‘the relative salience of European integration in the party's public stance in the year’ of the survey using an 11‐point scale, where 0 stands for ‘European Integration is of no importance, never mentioned’ and 10 indicates that ‘European Integration is the most important issue’. For the operationalization of the other variables, see the online Appendix.

The information regarding the preference vote, (raw) list rank at the selection stage and number of incumbent co‐partisans in the district was retrieved from Däubler et al. (Reference Däubler, Chiru and Hermansen2022). The statistics regarding the MEPs’ speeches come from Høyland et al. (Reference Høyland, Hobolt and Hix2019), while the information on their reports, number of EP terms served, age and gender is based on Daniel (Reference Daniel2015), Michon and Wiest (Reference Michon and Wiest2021) and Salvati (Reference Salvati2022). The data on leadership positions in the EP and at the EP committee level were retrieved from Høyland et al. (Reference Høyland, Sircar and Hix2009). Finally, the ministerial experience variable is based on Yordanova (Reference Yordanova2009), Daniel (Reference Daniel2015), and Casal Bértoa and Enyedi (Reference Casal Bértoa and Enyedi2022). For a summary of descriptive statistics of the dependent, independent and control variables, see Table A1 in the online Appendix.

The analyses are conducted using a generalized least squares (GLS) random effects model (Cameron & Trivedi, Reference Cameron and Trivedi2009), chosen to take into account the different quality of non‐incumbents across lists. I report two sets of models for all analyses, the second model being one that always includes country fixed effects. The latter should account for the cross‐country differences in the likelihood of voters casting preference votes depending on the electoral rules in place (e.g., how high the threshold is for preference votes to make a difference – see Däubler & Hix, Reference Däubler and Hix2018) but also for how politicized the EU is in the member state, which might influence the strength of the electoral connection. All models are run with robust standard errors clustered by party list‐election year to account for the hierarchical nature of the data. For the sake of simplicity, the article presents the results of GLS with a list of random effects, but the results are substantively very similar if fractional logistic regression is used instead.

Analyses and findings

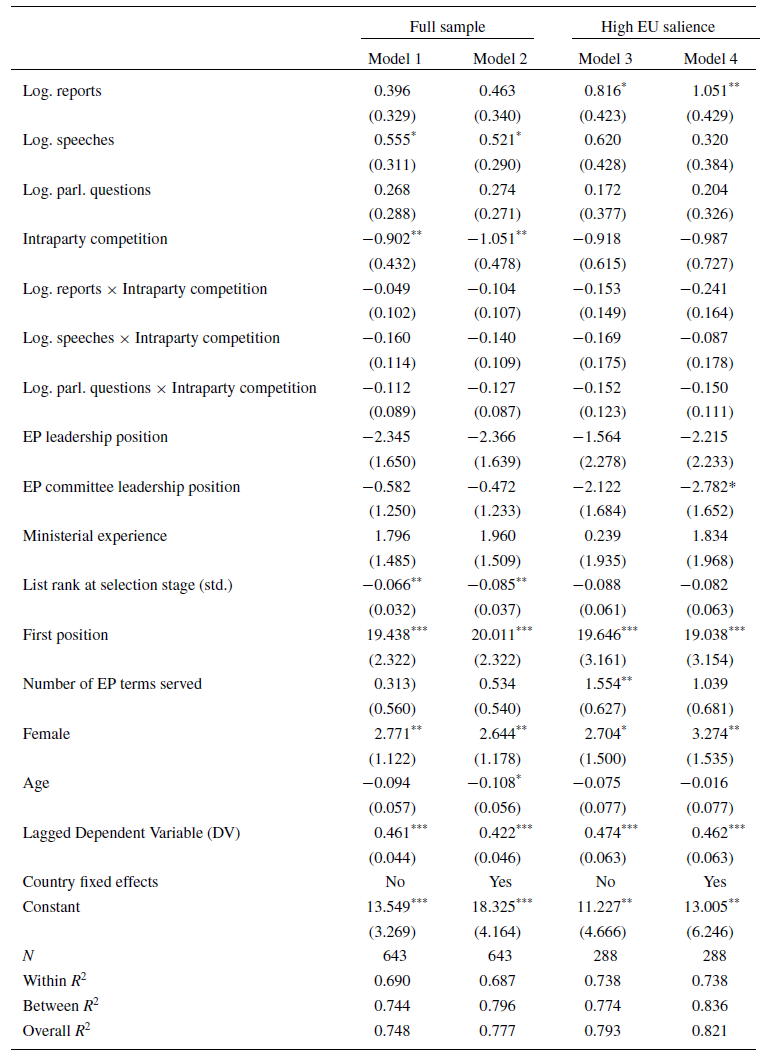

Table 1 reports the findings of the GLS with list random effects regressions run on panel data – incumbents nested into party lists observed at the 2004, 2009 and 2014 rounds of the EP elections. The full list of country elections included can be consulted in Table A3 in the online Appendix. Models 2 and 4 also include country fixed effects, but the main effects are robust to this additional control. Models 3 and 4 present the results of the analyses re‐run on a restricted sample to test H.2, which argued that the positive effect of legislative productivity on incumbents’ preference vote share will be registered only for the parties that assign high salience to EU integration, as they would prime their voters to pay more attention to what their MEPs are doing. This was operationalized based on the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny and Vachudova2022): only those parties that were assigned a mean score larger than 6 on the 11‐point scale measuring EU salience were included.

Table 1. Determinants of MEPs’ preference vote shares at the 2004–2014 elections (GLS random effects models)

Note: Significance at *0.1 ** 0.05 *** 0.01; models were run with robust standard errors clustered by party‐election year.

Abbreviations: EP, European Parliament; EU, European Union.

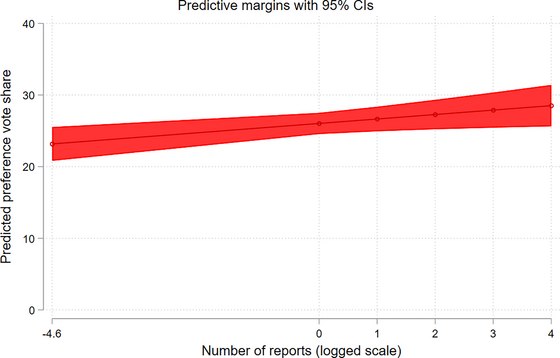

The results do not support hypothesis 1: models 1 and 2 analysing the full sample do not reveal consistent evidence for voters rewarding legislative productivity in the EP apart from the weak positive effect associated with parliamentary speeches, which might indicate that they are associated to some extent with a higher level of visibility for the voters. Instead, Models 3 and 4 corroborate hypothesis H.2 at least partially, showing a positive effect of the quantity of reports drafted on the share of preference votes. Computing predicted probabilities based on Model 4 in Table 1 showed that the effect of report writing is relatively small, but not irrelevant: writing one report as opposed to none increases the preference vote share by 3 per cent, whereas a full‐scale switch from writing no reports to writing 54 reports (i.e., the highest number of reports in this sample) increases the preference vote share by 5.3 per cent, from 23.2 per cent to 28.5 per cent. Figure 1 illustrates this effect.Footnote 8 An illustrative example of the electoral rewards of report writing for incumbents of parties assigning high salience to the EU is Danuta Maria Hübner, a Polish MEP representing the Civic Platform (PO). Hübner authored 17 reports in the seventh term of the EP and then received more than 73 per cent of the preference votes cast for her party in Warsaw, the district in which she ran.

Figure 1. Electoral rewards of report writing for incumbents of high EU salience parties. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

MEPs tend to win a considerably higher share of preference votes when they face no or limited co‐partisan incumbent competition (for an illustration of the magnitude of this effect, see Figure A1 in the online Appendix). Nevertheless, hypothesis H3 regarding the moderating impact of intra‐party incumbent competition in the district on voters rewarding legislative productivity cannot be corroborated: although the interaction terms have the expected negative signs, they fail to reach conventional levels of statistical significance.

The analyses fail to uncover a positive effect of holding a leadership position at EP or committee level irrespective of the sample used. On the contrary, the signs of the two variables are negative in all regressions. Thus, the alleged higher visibility in the national media brought by these positions does not appear to increase the name recognition and reputation among voters of the MEPs holding them.

As in national elections, the list rank at the selection stage and topping the party list make a huge difference for the share of preference votes. MEPs who have served as national ministers receive a considerably higher share of preference votes than incumbents lacking such experience, as shown by models that do not include the lagged DV (see Table A4 in the online Appendix). Nevertheless, the coefficients in Table 1 show that this attribute does not help to increase their electoral performance relative to previous elections. Female MEPs are also more likely to improve their share of preference votes, everything else being equal. This might be because of the relative rarity of this attribute leading to preference vote concentration, as most incumbent MEPs are male. Moreover, female MEPs might be perceived by voters who care about gender representation, or have more feminist convictions, as the female candidate with the highest chance of being elected.

Robustness checks

A first robustness check was to re‐run Models 3 and 4 in Table 1 using different thresholds for high EU salience. Table A5 in the online Appendix presents the results of the analyses run on the sample of parties whose average Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) EU salience score is higher than 5 (Models 9–10) and 6.5 (Models 11–12). In all four models, report writing results in a higher share of preference votes. Interestingly, the models run on the sample with a higher threshold for EU salience also provide some evidence in favour of H3, regarding a moderating impact of intra‐party competition. Thus, the electoral rewards for report writing diminish significantly when multiple co‐partisan incumbents are candidates in the same district.

Table A6 in the online Appendix replicates the regressions in Table 1 but uses the raw counts of the three types of parliamentary activities instead of the logarithmic‐transformed indicators. The positive effect associated with report writing is present for all these regressions not only for those on the restricted sample, although it is stronger for parties which assign high salience to the EU, as hypothesized by H.2. Once again, the electoral rewards of report writing seem to be moderated by the degree of intra‐party incumbent competition, as shown by the results of three of the four regressions. Nevertheless, these findings should be interpreted with caution given the possible distorting effects of the outliers present in the raw count data.

The electoral value of report writing does not seem to increase over time, as shown by the models in Table A7 in the online Appendix, which include an interaction between the EP term and the logged number of reports submitted by the MEP. The interaction term is statistically insignificant both in the models run on the entire sample and in the analyses restricted to the incumbents of the parties which assign high salience to EU integration.

Table A8 in the online Appendix presents a series of regressions that add the degree of usage of preference votes for the party in the district to the models in Table 1, which do not include country fixed effects. This variable is computed as the ratio of the sum of preference votes received by the candidates of the party in the district and the overall number of votes the party received in the district. The main findings hold, including regarding report writing for incumbents of parties displaying high EU salience. This additional control variable has a negative effect on the vote share of incumbents, indicating that preference vote uptake seems to favour newcomer candidates. The effect of this variable disappears in the models with country fixed effects, which is not surprising given that preference vote uptake is driven both by electoral rules (e.g., whether a preference vote is mandatory or whether voters are allowed multiple preferences) and by other country‐specific factors (e.g., voters’ perceptions about whether preference votes matter and the extent to which the party mobilizes supporters to use them).

Another robustness check was to control for the role of district magnitude (DM). DM influences the degree of sincere voting for parties (see Hix et al., Reference Hix, Hortala‐Vallve and Riambau‐Armet2017, for evidence based on experimental data) and could thus affect voters’ preference vote allocation calculations. DM could also be driving the incumbent co‐partisan effect.Footnote 9 The results in Table A9 in the online Appendix show that the DM does not drive the incumbent co‐partisan effect and that all the other main effects are robust to the inclusion of this variable. Last but not least, the main results are robust to using the share of co‐partisan incumbents among all party candidates in the district as a measure of incumbent co‐partisan crowdedness instead of the simple count of co‐partisan incumbent candidates (see Table A10 in the online Appendix). This variable does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance in any of the four regressions and their model fit is slightly poorer than those in Table 1. Together, these aspects indicate that intra‐party incumbent competition matters irrespective of the number of other co‐partisan candidates.

Conclusion

This study is the first to analyse how MEPs’ legislative performance influences the preference vote shares of incumbents running for re‐election, conditional on parties’ EU issue salience and co‐partisan legislator competition. Overall, there is little evidence of voters retrospectively rewarding or punishing individual legislators’ involvement in legislative activities. The only exception is the increased preference vote shares associated with report writing for MEPs of parties that assign high salience to the EU. While previous research has also indicated a potential positive role of reports, this study identifies the conditions under which they are more likely to matter and proposes a theoretical mechanism for them. Further research could gather comparative data on party communication and campaigning to test whether such parties indeed prime their voters to pay more attention to their MEPs’ legislative performance through their media efforts or whether the effect is the result of a decentralized personalization process in which individual incumbents cultivate a personal vote via their media appearances and social media presence (Balmas et al., Reference Balmas, Rahat, Sheafer and Shenhav2014). Alternatively, given the inter‐related nature of the politicization of EU integration in which voters and elites take cues from each other (Steenbergen et al., Reference Steenbergen, Edwards and De Vries2007), future studies could examine the extent to which the salience assigned by voters to the EU in general and the EP in particular (Clark, Reference Clark2014) drives these results as opposed to elite‐driven salience.

While there is some evidence in favour of a negative effect of incumbent intra‐party competition for preferential vote gains in general, this factor does not appear to moderate the extent to which legislators reap rewards for their legislative activity. This null finding would deserve further exploration to understand whether co‐partisan incumbent MEPs running in the same district deliberately choose not to emphasize their different levels of legislative productivity in EP election campaigns and attempt instead to differentiate themselves from their colleague MEPs through their ideological stances or by targeting different social constituencies (Isotalo et al., Reference Isotalo, Helimaeki, Mattila and con Schoultz2022).

The results discussed in this article are based on analyses of data from three rounds of EP elections: from 2004 to 2014. Expanding the scope to the 2019 EP elections is, nevertheless, unlikely to lead to substantively different findings regarding the electoral connection. If anything, even fewer incumbents were re‐elected in 2019: a legislative turnover rate of 60 per cent compared to around 50 per cent in the previous two rounds, while a high level of involvement in legislative activities appears not to have improved MEPs’ re‐election odds in candidate‐centred systems at the most recent elections (De Connick, Reference De Connick2021, p. 120).

Normatively, the fact that the legislative performance of MEPs is disconnected from preference vote shares in EP elections for most incumbents can be a cause of concern, especially for those scholars hoping that further personalization of EP electoral rules could spur a stronger electoral connection, more attention to what legislators do in Brussels and ultimately strengthen the EU's accountability and legitimacy. It could be argued, however, that this yardstick for judging the EU electoral connection is too demanding, as evidence for a personal vote rewarding legislative performance is extremely scarce even in the context of first‐order national elections in established democracies (Martin, Reference Martin2010). Nevertheless, if recently proposed changes to the ways EP elections are conducted come into existence, the potential for an electoral connection could increase. In May 2022, the EP adopted a proposal that endorses the creation of an EU‐wide constituency electing 28 MEPs in addition to those elected from national or subnational districts (European Parliament, 2022). The introduction of such a constituency would foster the creation of transnational party lists and, in the process, could also increase voters’ attention to the activity of incumbent MEPs.

One future direction of research could be to examine the extent to which past preference vote shares influence the likelihood of MEPs’ renomination and whether there is an interaction effect between electoral and legislative performance. Another avenue worth pursuing would be to expand the population of interest beyond incumbents and explore what determines preference voting and preference vote usage in EP elections more broadly in order to understand whether that differs from national elections and also what candidate attributes are more appealing to voters in EP elections.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Holly Bickerton, Matthias Dilling, Thomas Däubler and EJPR's five anonymous reviewers for insightful and constructive comments on previous versions of this article. The work on this paper was supported by a grant of the Romanian Ministry of Education and Research, CNCS ‐ UEFISCDI, project number PN‐III‐P4‐ID‐PCE‐2021‐233, within PNCDI III

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A1: Descriptive statistics

Table A2: Correlation matrix of variables

Table A3: European Parliament elections included in the analyses

Table A4: Determinants of MEPs’ preference vote share at the 2004‐2014 elections ‐ models without the lagged DV (GLS Random Effects models)

Table A5: Determinants of MEPs’ preference vote share at the 2004‐2014 elections for parties assigning high salience to European integration (GLS Random Effects models)

Table A6: Analyses with raw count activity variables (GLS Random Effects models)

Table A7: Does the effect of report writing change over time? (GLS Random Effects models)

Table A8: Determinants of MEPs’ preference vote share at the 2004‐2014 elections, controlling for preference vote usage (GLS Random Effects models)

Table A9: Determinants of MEPs’ preference vote share at the 2004‐2014 elections, controlling for district magnitude (GLS Random Effects models)

Table A10: Determinants of MEPs’ preference vote share at the 2004‐2014 elections, with share of incumbent co‐partisans in district as proxy for intraparty competition (GLS Random Effects models)

Figure A1: Incumbent co‐partisan crowdedness and preference vote share

Dataset