1. Introduction

Since the 1980s, advanced democratic societies, particularly within the OECD, have experienced a sustained rise in economic inequality (Chancel and Piketty, Reference Chancel and Piketty2021; OECD, 2014). Because voting remains a central channel through which citizens express political preferences, understanding how widening inequality shapes electoral behaviour has become a core concern in contemporary political science. Existing research shows that material disparities often correspond to divergent voting patterns between affluent and economically disadvantaged groups (Gelman, Reference Gelman2009; Han, Reference Han2016; Oesch and Rennwald, Reference Oesch2018). Yet, persistent anomalies challenge conventional class-voting models. In the 2020 and 2024 United States presidential elections, for example, Republican candidates secured substantial support in some of the country’s poorest states, complicating expectations based on economic self-interest alone.

The present study advances the comparative study of class politics by incorporating subjective class consciousness into the analysis of political behaviour. Rather than treating class solely as an objective position defined by income or occupation, it conceptualises class as a relational and perceptual construct shaped by social comparison. The central claim is that inequality influences political alignment not only through material conditions but also by reshaping how individuals perceive their relative position within the social hierarchy. As inequality rises, symbolic boundaries between perceived upper and lower classes become more salient. These perceptions, in turn, structure partisan orientations by shaping how individuals interpret their place in society and their relationship to others.

This perspective helps explain a pattern that sits uneasily with conventional expectations. Both individuals who identify as subjectively upper class and those who identify as subjectively lower class exhibit higher levels of conservative alignment, albeit for different reasons. Among the subjectively upper class, conservatism reflects preferences for institutional stability and the preservation of existing advantages. Among the subjectively lower class, conservative alignment is more closely linked to concerns about social order, legitimacy, and belonging in contexts of limited mobility. By contrast, identification with a broad subjective middle class, more common under conditions of lower inequality, has been associated with progressive or reform-oriented political preferences.

South Korea (hereafter Korea) provides a useful setting in which to examine these dynamics in a non-Western democratic context. As a late industrialiser that democratised in the late twentieth century, Korea combines rapid economic transformation with enduring institutional and historical legacies. Following the 1997 Asian financial crisis, income and wealth inequality increased substantially (An and Bosworth, Reference An and Bosworth2013), even as democratic competition stabilised. At the same time, political behaviour remains shaped by the legacies of authoritarian rule, regional cleavages, and persistent security tensions with North Korea, producing an electorate in which class, region, and ideology intersect in complex ways (Steinberg and Shin, Reference Steinberg and Shin2006; Kang, Reference Kang2008; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Chu and Park2007; Hong et al., Reference Hong, Park and Yang2022; Lee, Reference Lee2023; Shin and Shyu, Reference Shin and Shyu1997; Thompson, Reference Thompson2007; Han, Reference Han2025a). Examining subjective class voting in this context contributes to a broader comparative understanding of how inequality and perception interact to structure political behaviour beyond Western cases.

The empirical analysis proceeds in two steps. The first examines the association between subjective class identification and individual vote choice using nationally representative survey data. The second assesses whether local economic inequality at the administrative-unit level is associated with aggregate electoral outcomes across presidential and legislative elections between 2012 and 2022. Together, the results indicate that both subjective class perceptions and contextual inequality are systematically associated with conservative alignment. These findings suggest that inequality shapes political behaviour not only through material divisions but also through perceptions of relative social position, underscoring the value of incorporating subjective dimensions into the study of class politics in diverse democratic settings.

This study proceeds as follows. The next section reviews the literature on class politics and situates the Korean case within it. The third section presents the theoretical framework and hypotheses. The fourth section describes the data, research design, and empirical results. The final section discusses the implications of the findings for understanding inequality and political behaviour.

2. Social stratification and class politics

The relationship between social class and political behaviour has long occupied a central place in the study of democratic development, particularly in Western Europe. A foundational contribution came from Lipset and Rokkan (Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967), who explained the formation of political parties through enduring social cleavages, especially those that emerged during the industrial revolution. Their cleavage theory posited that material conflicts divided citizens into politically salient groups, which in turn formed the social bases of partisan alignments. Building on this tradition, Lipset (Reference Lipset1960) argued that members of the working or lower classes were generally inclined toward progressive parties advocating redistribution and equality, whereas upper-class voters tended to support conservative parties defending established hierarchies and economic privilege. This framework profoundly shaped the study of party systems and voting behaviour across advanced democracies.

Subsequent scholarship has both reaffirmed and refined the role of class in political behaviour. Foundational studies by Evans (Reference Evans1999), Goldthorpe (Reference Goldthorpe and Evans1999), and Müller (Reference Müller and Evans1999) confirmed the continuing relevance of class cleavages in Western and post-communist societies, even as patterns of class-based alignment evolved. More recent research presents a more differentiated picture. Oesch and Rennwald (Reference Oesch2018) show that although Western Europe has moved from a bipolar to a tripolar political structure, class remains an important determinant of electoral behaviour. Emanuele (Reference Emanuele2024) further demonstrates that the strength and configuration of class-based alignments from 1871 to 2020 vary systematically across national party systems. Relatedly, Gugushvili et al. (Reference Gugushvili, Halikiopoulou and Vlandas2025) find that downward class mobility generates political discontent and support for far-right parties, underscoring the political relevance of perceived status decline. At the same time, Hooghe and Marks (Reference Hooghe and Marks2025) document the growing importance of educational cleavages, which in some contexts rival or surpass traditional class divisions. Taken together, this literature suggests that while the forms through which class is expressed in politics have changed, its material and symbolic significance remains.

The American case illustrates this transformation vividly. Frank (Reference Frank2004) argued that cultural and moral issues had displaced material interests among working-class voters, thereby facilitating conservative alignment. In contrast, Bartels (Reference Bartels2017) maintained that economic self-interest still matters, particularly when mediated by short-term policy incentives. Other scholars, including Stonecash (Reference Stonecash2005), highlight persistent anomalies such as conservative support among economically disadvantaged groups, patterns that defy simple economic or cultural explanations. Together, these debates reveal that class politics in advanced democracies has become multidimensional, shaped by intersecting material, cultural, and psychological factors.

More broadly, theorists such as Lipset (Reference Lipset1981) and Clark and Lipset (Reference Clark and Lipset2001) have questioned whether traditional class categories retain explanatory power in post-industrial societies, where occupational and income structures have diversified and party loyalties have weakened. Mair (Reference Mair1990) reinforced this scepticism by noting that political parties themselves have become less effective in mobilising class-based identities since the 1980s. These observations suggest that the once stable linkage between class position and partisan behaviour has been substantially reconfigured.

In response, alternative frameworks have emerged to explain political alignment under conditions of social and economic change. Economic voting theory, for instance, shifts attention from collective identity to individual evaluation of policy performance. Building on Downs (Reference Downs1957), scholars such as Anderson et al. (Reference Anderson, Mendes and Tverdova2004), Duch (Reference Duch, Boix and Stokes2007), Valdini and Lewis-Beck (Reference Valdini and Lewis-Beck2018), and Grecu et al. (Reference Grecu, Vranceanu and Chiriac2025) propose that voters act as rational evaluators of government performance and policy outcomes rather than as members of cohesive class blocs. These approaches capture the increasing fluidity of electoral choice in an era of economic volatility and ideological realignment.

Despite these transformations, how class continues to organise political behaviour remains an open question, particularly outside the advanced Western democracies in which most theories of class politics were developed. As Rokkan cautioned, models derived from Western experiences of industrialisation and democratisation cannot be applied uncritically to other settings (Flora et al., Reference Flora, Kuhnle and Urwin1999). Korea illustrates this limitation. As a late industrialiser that democratised only in the late twentieth century, it combines rapid economic growth with enduring legacies of regionalism, authoritarian rule, and ideological division. These conditions have produced a social structure in which inequality, political identity, and historical experience intersect in distinctive ways. Examining class politics in this context, therefore, provides an opportunity to reassess the scope of classical theories and to better understand how class-based alignments are reconfigured in non-Western democracies.

2.1 The Korean context

Korea’s political landscape has been deeply shaped by its turbulent modern history. The division of the Korean Peninsula after liberation from Japanese colonial rule in 1945, the devastation of the Korean War, and the subsequent geopolitical bifurcation between North and Korea entrenched a highly polarised ideological environment. As Steinberg and Shin (Reference Steinberg and Shin2006) and Kang (Reference Kang2008) observe, these historical ruptures constrained the formation of class-based political cleavages and left a lasting imprint on the nation’s political structure.

For much of the postwar period, particularly until the early 1980s, South Korea was governed by conservative authoritarian regimes that prioritised anti-communism and rapid economic development as core elements of state ideology (Im, Reference Im and Im2020; Lee, Reference Lee2009; Han, Reference Han2024a). Korea’s transition to democracy differed from that of many Western societies in that it was not driven primarily by established political parties, but by organised civil society movements. These movements, grounded in demands for political liberalisation and human rights, gradually dismantled authoritarian rule and reshaped the country’s political discourse by expanding participation and contestation.

Korean conservatism has remained deeply influenced by anti-communist ideology rooted in the perceived threat from North Korea (Kim, Reference Kim and Kang2014). This orientation has historically emphasised individual liberty, national security, and social order, often subordinating concerns about distributive equality. Although Korean conservatism has evolved over time, its foundational principles have remained largely intact. The rise of the New Right in the early 2000s incorporated market-oriented and neoliberal ideas into the conservative tradition, aligning it more closely with global trends while preserving its anti-communist core (Yang, Reference Yang2021; Yun, Reference Yun2012). As a result, contemporary conservatism in Korea places strong emphasis on economic growth, the protection of large conglomerates (chaebol), and national security (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Min and Seo2018; Lee and You, Reference Lee and You2019; Han, Reference Han2024a).

A second defining feature of Korean politics is the persistence of regionalism, which has long constrained the development of class-based political competition. Electoral alignments have historically been shaped more by regional loyalties than by socioeconomic divisions, with regional identities rooted in developmental disparities and historical grievances serving as durable bases of political mobilisation (Kwon Reference Kwon2010; Moon, Reference Moon2005). Even as Korea entered a post-industrial phase marked by rising educational attainment and occupational diversification, regional and generational cleavages continued to structure electoral behaviour (Kang, Reference Kang2008; Lee, Reference Lee2015; Lee and You, Reference Lee and You2019).

Empirical research further underscores the limited explanatory power of economic position in Korean voting behaviour. Although some studies identify class-related patterns in partisan support, these effects are consistently weaker than those associated with region, generation, and ideology (Kang, Reference Kang2008; Lee, Reference Lee2015). Analyses of electoral outcomes between 2004 and 2014 similarly find that income-based voting exists but remains secondary to regional and generational influences (Lee and You, Reference Lee and You2019). Taken together, these findings suggest that conventional class voting models alone are insufficient for explaining Korean electoral behaviour and point to the need for a framework that integrates historical legacies, regional identities, and ideological cleavages in understanding the evolution of class politics in Korea.

Overall, these features suggest that Korea’s class politics cannot be understood solely in terms of material position. Instead, they are mediated by historical experience, geopolitical division, and cultural identity. Against this backdrop, the following section develops a theoretical framework that situates subjective class consciousness at the centre of political behaviour, offering a way to explain how inequality, perception, and identity intersect to shape partisan alignment in contemporary Korea.

3. Subjective class consciousness, economic inequality, and voting

Building on the preceding discussion of Korea’s historical and institutional legacies, the relationship between inequality and political behaviour can be clarified by focusing on how citizens perceive their social position. Traditional indicators such as income, education, and occupation remain indispensable for mapping structural stratification, yet they do not capture how individuals interpret their standing in everyday life. Class is also a social identity formed through comparison, emotion, and shared meaning. Individuals evaluate their position relative to salient others in their immediate environment, and in doing so, they form subjective class consciousness, which shapes political attitudes and choices in ways that objective status alone cannot predict (Jackman and Jackman, Reference Jackman and Jackman1973, Reference Jackman and Jackman1983; Irwin, Reference Irwin2015).

The theoretical distinction between objective and subjective class is central here. Objective class refers to measurable characteristics such as income, education, occupation, and assets (Hollingshead, Reference Hollingshead1975). Subjective class captures individuals’ self-placement within a perceived hierarchy that is constructed through routine social interaction and relative comparison with neighbours, coworkers, and peers who supply the relevant standards of evaluation (Weakliem and Adams, Reference Weakliem and Adams2011; Sosnaud et al., Reference Sosnaud, Brady and Frenk2013). Objective and subjective locations often overlap, but they can diverge in systematic ways depending on local reference groups, neighbourhood composition, and informational environments, which means that people of similar means can arrive at different political conclusions because they experience status differently (Jackman and Jackman, Reference Jackman and Jackman1973; D’Hooge et al., Reference D’Hooge, Achterberg and Reeskens2018; Evans and Kelly, Reference Evans and Kelly2004; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Johnston and Lown2015; Han, Reference Han2025b).

These perceptual processes become increasingly significant as inequality intensifies. Because inequality is inherently relational, its political implications arise not only from the objective distribution of resources but from how individuals perceive differences between themselves and others (Merton and Rossi, Reference Merton, Rossi, Merton and Lazarsfeld1950; Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1981). As disparities grow more visible, people are more likely to evaluate their own social standing in comparative rather than absolute terms. This heightened sensitivity to relative position strengthens identification with either a higher or lower perceived class, reinforcing symbolic boundaries within the social hierarchy and shaping political attitudes accordingly.

Empirical research shows that perceived inequality and perceived status are powerful predictors of political attitudes, often rivalling or exceeding objective indicators in explanatory force (Fraile and Pardos-Prado, Reference Fraile and Pardos-Prado2014; Gimpelson and Treisman, Reference Gimpelson and Treisman2017; Hauser and Norton, Reference Hauser and Norton2017; Lee and Han, Reference Lee and Han2024). In the same vein, subjective class identity independently predicts partisanship and participation when objective status is held constant, which indicates that perceptual mechanisms channel the political consequences of structural inequality (Brown-Iannuzzi et al., Reference Brown-Iannuzzi, Lundberg, Kay and Payne2015; Han and Kwon, Reference Han and Kwon2023; Szewczyk and Crowder-Meyer, Reference Szewczyk and Crowder-Meyer2022; Marzinotto, Reference Marzinotto2025; Han, Reference Han2025c).

Comparative research situates these patterns within a broader transformation of class politics. In many advanced democracies, the tight coupling between occupational position and party choice has loosened, generating debates over class dealignment and class defection (Gingrich and Häusermann, Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015; Oesch and Rennwald, Reference Oesch2018). Yet, class has not disappeared from politics. Rather, it has been reconfigured around symbolic recognition, identity, and perceived status, which now mediate how material divisions become politically salient (Gidron and Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2017). In this reconfigured landscape, perceptions of social standing increasingly structure political alignment.

Korea provides a distinctive setting for examining these dynamics. Rapid industrialisation, developmental authoritarianism, and persistent regionalism have created a political environment in which inequality is both visible and normatively charged. Within this context, subjectively high and subjectively low identifiers tend to converge on conservative alignment for different mechanisms, while the subjective middle is more likely to support progressive positions centred on equality and inclusion.

First, the mechanism linking the subjectively high class to conservative alignment is primarily material and institutional in nature, reinforced by perceptual considerations of status and stability. Individuals who perceive themselves as relatively high in social standing have strong incentives to maintain existing hierarchies and to minimise redistributive pressures that could erode their advantages. Consistent with standard political economy models, greater inequality tends to raise the demand for redistribution among lower-income groups, thereby increasing the stakes for those who expect to be net contributors (Meltzer and Richard, Reference Meltzer and Richard1981). Under such conditions, conservative parties become appealing as defenders of property rights, regulatory restraint, and institutional continuity. The alignment is further sustained through institutional channels that allow resource-rich actors and organised interests to influence policymaking and constrain redistributive coalitions, making conservative leadership a rational strategy of institutional preservation for the privileged (Schlozman et al., Reference Schlozman, Brady and Verba2018).

In Korea, conservative parties have long identified themselves with economic growth, developmental success, administrative stability, and market-oriented ideas emphasising limited government (Han, Reference Han2024a). Voters who perceive themselves as belonging to the subjectively high class often view conservatism as a means of safeguarding market predictability and sustaining economic progress. The legacy of rapid industrialisation under authoritarian rule reinforces the belief that political stability and conservative leadership are essential for protecting the institutional foundations of their social and economic position. As a result, support for conservative parties among the subjectively high class reflects not only a defence of material interests but also a broader commitment to preserving the institutions and policy orientations associated with order, prosperity, and continuity.

Second, the mechanism linking the subjectively low class to conservative alignment is primarily symbolic and psychological, rooted in the search for stability, legitimacy, and belonging in an unequal social environment. Individuals who perceive themselves as lower in status may support the prevailing political order when it provides a sense of moral coherence and social recognition, even when such alignment yields little direct material benefit. System justification theory offers a useful framework for understanding this tendency. It posits that people, including those in disadvantaged positions, often rationalise and defend existing social arrangements because affirming their legitimacy reduces psychological discomfort and uncertainty (Sears et al., Reference Sears, Lau, Tyler and Allen1980; Jost and Hunyady, Reference Jost and Hunyady2005). Supporting conservative political forces can therefore serve as a form of symbolic reassurance, reaffirming the belief that stability and order are both necessary and morally justified. Related research demonstrates that symbolic values such as societal harmony and national strength often weigh more heavily than immediate economic interests in shaping political preferences, particularly in contexts where mobility opportunities are limited or where economic insecurity heightens perceptions of vulnerability (Citrin et al., Reference Citrin, Green and Sears1990; Franko and Witko, Reference Franko and Witko2022; Shayo, Reference Shayo2009; Han, Reference Han2025b). Conservative narratives that emphasise order, tradition, and collective identity thus resonate strongly with status-anxious citizens and can create durable patterns of attachment among groups that feel culturally or economically marginalised (Frank, Reference Frank2004; Gelman, Reference Gelman2009; Inglehart and Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2016).

In the Korean context, these symbolic mechanisms operate within a distinctive historical and institutional environment. Conservative parties have long presented themselves as defenders of economic growth, national security, and social order, drawing legitimacy from Korea’s developmental state legacy, which closely linked economic progress to political stability and collective discipline (Im, Reference Im and Im2020; Lee, Reference Lee2009). The experience of rapid industrialisation under authoritarian rule, coupled with the enduring division of the Korean Peninsula, cultivated a political culture that associates patriotism, order, and national resilience with conservative leadership. Even as Korea has democratised, the continuing security tension with North Korea and the persistence of developmentalist values sustain appeals that tie conservatism to moral strength and civic responsibility (Kim, Reference Kim and Kang2014; Han, Reference Han2024a, Reference Han2025a). For individuals who perceive themselves as socially or economically marginal, such narratives provide a way to affirm their value within a morally ordered community. By endorsing parties that champion stability, discipline, and national unity, these voters find a sense of dignity, respectability, and belonging that mitigates feelings of exclusion or decline. In this way, symbolic and psychological needs for legitimacy and identity interact with Korea’s historical legacies of security anxiety and developmental nationalism to produce a durable conservative orientation among those who feel disadvantaged or left behind.

Third, the subjective middle class is more likely to adopt liberal and progressive orientations under conditions of relative equality, and this process operates through social and relational mechanisms. When economic differences are modest, individuals are more likely to identify with a broad social middle and to interact frequently across narrow status boundaries. Such environments foster reciprocity, generalised trust, and civic engagement, which in turn encourage egalitarian and inclusive policy preferences (Putnam, Reference Putnam1995, Reference Putnam2000; Brehm and Rahn, Reference Brehm and Rahn1997; Almakaeva et al., Reference Almakaeva, Welzel and Ponarin2018). Social homophily and cohesive networks amplify these effects by strengthening cooperation and the diffusion of civic norms (McPherson et al., Reference McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook2001; Catterberg and Moreno, Reference Catterberg and Moreno2006; Fukuyama, Reference Fukuyama1995; Zmerli and Newton, Reference Zmerli and Newton2008).

In Korea, the subjective middle class has often been associated with reformist and redistributive orientations. During the democratic transition of the late twentieth century, middle-class professionals and urban salaried workers contributed to movements advocating political liberalisation and modest welfare expansion (Arita, Reference Arita2003; Koo, Reference Koo1991; Teichman, Reference Teichman2014; Shin, Reference Shin1999). Although subsequent socioeconomic transformation has complicated class boundaries (Nam, Reference Nam2013), survey evidence continues to indicate that middle-class respondents tend to express stronger support for redistribution and social equity than their counterparts (Yeo and Kim, Reference Yeo and Kim2017). Within this context, the subjective middle class serves as a symbolic anchor of social cohesion, showing a general preference for political actors who emphasise fairness, accountability, and inclusion over hierarchy or moral order.

Together, these mechanisms clarify how conservative support can persist among those who perceive themselves as either advantaged or disadvantaged in contexts marked by inequality, historical polarisation, and security tension. As inequality deepens, individuals evaluate their position less in absolute terms and more through social comparison, which reinforces identification with either the upper or lower ends of the hierarchy. For those who see themselves as high in status, conservatism serves as a means of maintaining material advantage and institutional continuity. This logic aligns with political economy models that link redistribution preferences to income position and with evidence that privileged groups use political influence to preserve favourable arrangements. By contrast, individuals who view themselves as lower in status often gravitate toward conservatism for symbolic and psychological reasons. When upward mobility seems unlikely, and status anxiety intensifies, conservatism offers a sense of legitimacy, order, and belonging. This pattern accords with theories of system justification and identity-based politics, which emphasise that disadvantaged groups may support the status quo to restore stability and moral coherence.

In contrast, more equal contexts encourage identification with a broad subjective middle class. Such environments reduce social distance and facilitate everyday interaction across relatively similar groups, fostering trust, reciprocity, and civic cooperation. These conditions tend to support liberal and participatory orientations grounded in inclusiveness and collective well-being.

This framework clarifies how perceptions of relative rank and social distance, formed within one’s immediate environment, mediate how inequality is perceived and expressed in political behaviour. The empirical analysis that follows tests this argument by combining individual-level survey data on subjective class identification and vote choice with local administrative–level electoral outcomes and localised measures of inequality, thereby examining how personal perceptions and contextual conditions jointly shape patterns of partisan alignment.

4. Empirical assessments

To evaluate the theoretical framework proposed in this study, two empirical analyses are conducted. The first examines the relationship between subjective class consciousness and voting behaviour at the individual level, while the second explores the association between economic inequality and electoral outcomes at the local administrative level (si-gun-gu). Although the units of analysis differ, both approaches employ the same dependent variable, which measures support for conservative parties, and incorporate comparable sets of control variables adapted to the specific context of each analysis.

4.1 Analysis of subjective class consciousness on voting individual-level analysis

The first empirical analysis examines how subjective class consciousness influences individual-level voting behaviour in Korea. It draws on data from the Korea General Social Survey (KGSS), a nationally representative survey administered annually through multi-stage area probability sampling and face-to-face interviews. The survey covers adults aged 18 and older and provides detailed information on political attitudes, socioeconomic characteristics, and social perceptions. The analytical sample includes all available survey years from 2003 to 2021, except 2013, 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018, for which the relevant measures of subjective class consciousness were not collected.

The dependent variable is a binary indicator of vote choice among voters, coded as one if the respondent reported voting for a conservative candidate from the People Power Party in the most recent national election and zero if the respondent voted for a non-conservative candidate. Respondents who reported not voting are excluded from the analysis in order to distinguish partisan choice from electoral participation.

Since the 1990s, Korea’s party system has been structured primarily around two major political blocs. Although party names and organisational forms have changed over time, the People Power Party and the Democratic Party of Korea have remained the principal representatives of conservative and progressive politics, respectively (Han, Reference Han2022a). While Korea formally operates under a multiparty system, electoral competition since democratisation has largely been organised around these two blocs rather than a fully fragmented party system (Hellmann, Reference Hellmann2014; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Lee and Hur2022). The conservative and progressive camps have served as the central poles of competition, particularly in presidential elections and processes of government formation (Lee and Repkine, Reference Lee and Repkine2020; Lee and You, Reference Lee and You2019).

At the same time, minor parties have periodically secured meaningful vote shares and parliamentary representation, especially in legislative elections, reflecting the fluid and weakly institutionalised nature of Korea’s party system (Moon, Reference Moon2005; Cho and Kruszewska, Reference Cho and Kruszewska2018). These minor-party dynamics often intersect with regional and generational cleavages, contributing to variation in vote distribution without displacing the broader conservative–progressive alignment that structures national electoral competition (Moon, Reference Moon2005; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Lee and Hur2022). Accordingly, although partisan competition in Korea cannot be characterised as a strict two-party system, bloc-level classification remains a commonly used and analytically useful approach for examining ideological alignment and electoral outcomes in a context of fluid party labels but persistent partisan structure (Hellmann, Reference Hellmann2014; Lee and Singer, Reference Lee and Singer2022).

The principal independent variable, subjective class consciousness, is derived from a survey question that asks respondents: ‘Compared to the average Korean household, do you subjectively consider your household’s economic status to be somewhat higher or lower than average?’ Responses were measured on a five-point scale, where values of 1–2 indicate that respondents perceive their household income as higher than average, 3 represents the average, and 4–5 indicate lower-than-average perceptions. For analytical clarity, these responses were recoded into the following three categories of perceived class position: high class (1–2), middle class (3), and low class (4–5). Three corresponding dummy variables were then created, with the subjective middle class serving as the reference category in all regression models. This measure reflects subjective rather than objective class position because it is based on individuals’ own evaluations of their household’s relative standing within society, incorporating not only material conditions but also personal and comparative perceptions of status. As such, it provides a meaningful indicator of how people locate themselves within the social hierarchy.

To account for objective socioeconomic status, the analysis includes three standard indicators: income, education, and occupation. Income is measured on a 22-point ordinal scale, capturing fine-grained variation in household earnings. Education is coded from 0 (no formal education) to 5 (university degree or higher). Occupation is represented by two binary variables: one identifying employers (individuals who operate a business with employees) and another identifying professionals or managers, following the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO). Together, these indicators capture key dimensions of Korea’s socioeconomic hierarchy.

Consistent with prior research on Korean electoral behaviour (Nam, Reference Nam2000; Lee and Brunn, Reference Lee and Brunn1996; Kang, Reference Kang2008; Lee and You, Reference Lee and You2019; Park and Chang, Reference Park and Chang2023), the models also include demographic and contextual controls. Sex is coded as one for female respondents, age is measured on a six-point scale, and residential context is categorised into four levels of urbanicity, ranging from rural to inner-metropolitan areas. Marital status is coded as one for respondents living with a spouse or partner. Year fixed effects are included in all models to account for temporal variation across survey waves (see Appendix A for variable details).

To minimise the risk of post-treatment bias, the models exclude political ideology as a covariate. As discussed in previous research, including attitudinal variables such as ideology may introduce endogeneity when they are influenced by the very political choices being modelled (Albertson and Guiler, Reference Albertson and Guiler2020; Berlinski et al., Reference Berlinski, Doyle, Guess, Levy, Lyons, Montgomery, Nyhan and Reifler2023). This modelling decision allows for a more conservative estimate of the relationship between class identification and vote choice. Given the binary nature of the dependent variable, Probit regression models are employed to estimate the probability of voting for a conservative candidate. Table 1 presents the results from three model specifications.

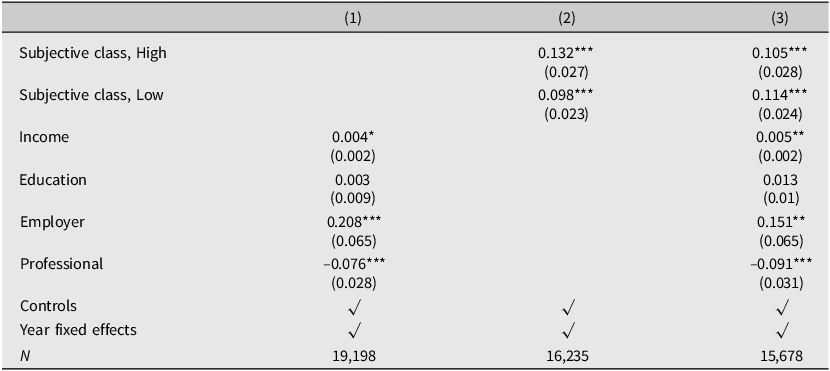

Table 1. Subjective class and voting for conservative parties, high and low classes

Note: See Appendix B for full results.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10.

Model 1 includes only objective socioeconomic variables. Income is positively associated with conservative voting (p < 0.10). Being an employer is positively and significantly related to supporting conservative candidates (β = 0.208, p < 0.01), suggesting that individuals engaged in business ownership are more inclined toward conservatism. In contrast, those in professional or managerial positions are significantly less likely to vote for conservative parties (β = –0.076, p < 0.01). Education does not exert a statistically significant effect.

Model 2 focuses exclusively on subjective class identification. Both high and low subjective class groups are significantly more likely to support conservative parties than the subjective middle class. Individuals identifying as subjectively high class show a stronger probability of conservative voting (β = 0.132, p < 0.01), while those identifying as subjectively low class also demonstrate elevated conservative support (β = 0.098, p < 0.01). These findings reveal a curvilinear relationship in which deviations from the subjective middle class, whether upward or downward, are associated with increased alignment toward conservative candidates.

Model 3 combines subjective and objective variables. Identification as either subjectively high or low class remains positive and statistically significant (β = 0.104 and 0.114, both p < 0.01), even after controlling for income, education, and occupation. This result indicates that subjective class consciousness exerts an independent influence on conservative voting beyond material conditions. The corresponding average marginal effects (AMEs) (reported in Appendix Table B3) show that identifying as high class increases the probability of voting conservative by 0.039 (p < 0.001), while identifying as low class increases it by 0.042 (p < 0.001). These marginal effects, equivalent to roughly a four-percentage-point increase in the probability of conservative voting relative to the subjective middle class, confirm that upward or downward deviations from the perceived middle are associated with stronger conservative alignment.

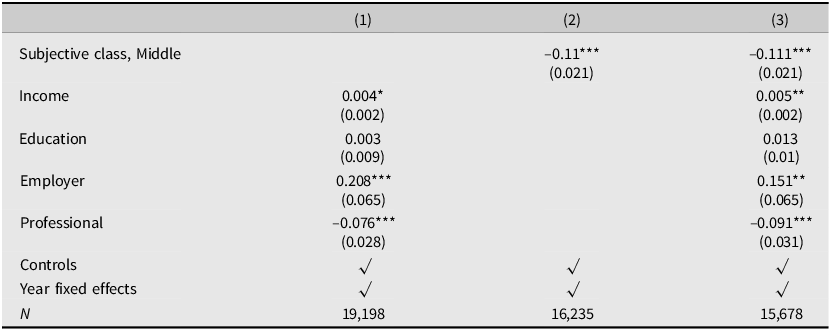

Table 2 presents a re-specification of the Probit regression models to examine the political significance of identifying with the subjective middle class. As in the preceding analysis, Model 2 includes only subjective class variables, while Model 3 incorporates both subjective and objective indicators of socioeconomic status. Model 1, which includes only objective variables, is identical to that reported in Table 1 and is reproduced here for reference.

Table 2. Subjective class and voting for conservative parties, middle class

Note: See Appendix B for full results.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10.

In Model 2, identification with the subjective middle class is negatively associated with the likelihood of voting for a conservative party candidate (β = –0.11, p < 0.01). This result indicates that individuals who perceive themselves as middle class are significantly less inclined to support conservative parties compared to those who identify as either subjectively upper or lower class. The finding complements the results from Table 1, confirming that deviations from the subjective middle, whether upward or downward, are associated with greater conservative alignment.

Model 3 confirms the robustness of this relationship. When objective socioeconomic indicators such as income, education, and occupation are added, the negative association between middle-class identification and conservative voting remains strong and statistically significant (β = –0.11, p < 0.01). The corresponding AMEs, reported in Appendix Table B4, are –0.041 (p < 0.001), indicating that individuals who perceive themselves as middle class are about four percentage points less likely to vote for a conservative candidate than those identifying as upper or lower class. This finding reinforces the conclusion that the subjective middle class is the least conservative group in the electorate and that perceptions of class position, rather than objective socioeconomic status alone, structure political alignment in Korea.

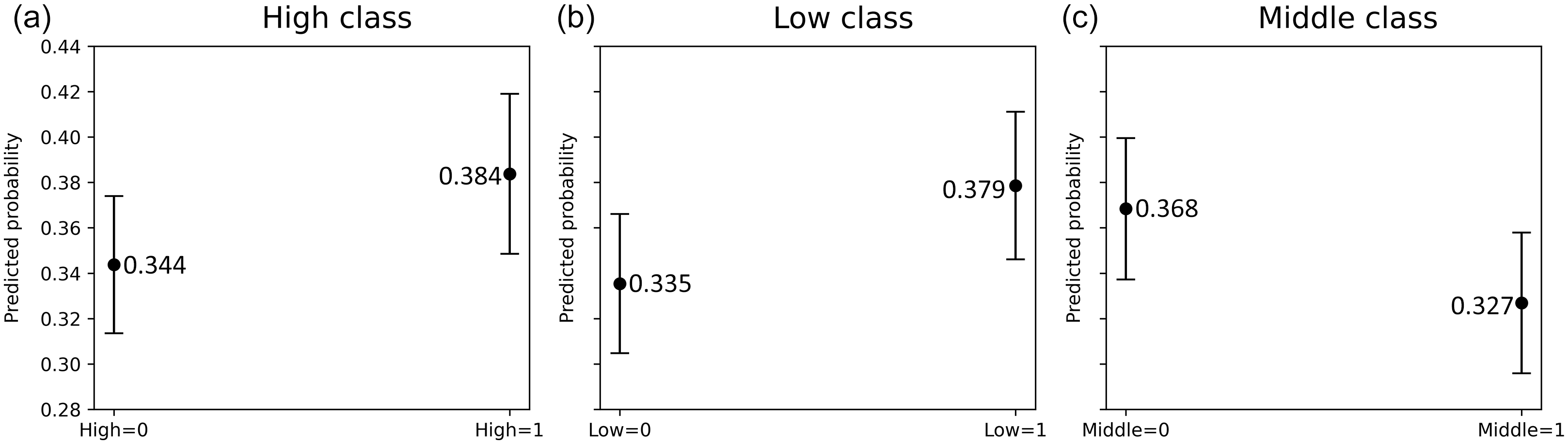

To assess the substantive impact of subjective class identification on voting behaviour, predicted probabilities were derived from the Probit estimates reported in Figure 1, with all other variables held at their mean values and 95 per cent confidence intervals used to reflect estimation uncertainty. The results display a consistent pattern that aligns with the AMEs. Identification with either the subjective upper or lower class is associated with a higher probability of supporting a conservative candidate, whereas identification with the subjective middle class corresponds to a lower probability of conservative support.

Figure 1. Predicted probabilities of subjective class on voting for conservative parties.

Among respondents who do not identify as high class, the predicted probability of voting for a conservative candidate is 0.344. This probability increases to 0.384 among those identifying as high class, a difference of approximately four percentage points. A similar pattern appears among respondents identifying as lower class, for whom the probability of conservative voting rises from 0.335 to 0.379. In contrast, identification with the subjective middle class is associated with lower conservative support. Individuals who perceive themselves as middle class have a predicted probability of 0.327 of voting conservative, compared with 0.368 among those who do not identify as middle class, a difference of roughly four percentage points.

These estimates are consistent with the AMEs, which show that identifying as either high or low class is associated with an increase of about four percentage points in the probability of conservative voting relative to the middle class (Appendix Tables B3 and B4). Together, the marginal effects and predicted probabilities indicate a curvilinear relationship in which deviations from the subjective middle class, whether upward or downward, are associated with stronger conservative alignment, while the middle class remains the least conservative group.

Additional analyses by demographic subgroup, reported in Figure B1, further support this pattern. Across age, gender, marital status, and urbanicity, respondents identifying as subjectively high or low class consistently show higher probabilities of conservative voting than those identifying as middle class. Although the size of the differences varies modestly across subgroups, the direction of the association is stable. This consistency suggests that the observed pattern is not confined to specific demographic or spatial contexts but reflects a more general relationship between perceived social position and political orientation in contemporary Korea.

4.2 Analysis of economic inequality and voting at the local administrative level

This section examines the association between localised economic inequality and conservative voting patterns across local administrative units (si-gun-gu) in Korea, situating the analysis within the broader framework of subjective class consciousness. The analysis rests on the premise that perceptions of social position are formed through comparison with proximate others and that these localised reference contexts condition how inequality is interpreted and politically expressed. Rather than assuming that perceptions derive solely from national-level conditions, the analysis treats the immediate administrative environment as a salient context in which relative economic standing becomes visible and socially meaningful. In the Korean case, the si-gun-gu administrative unit provides a relevant spatial setting for such comparative evaluations (Han and Kwon, Reference Han and Kwon2023; Park and Kim, Reference Park and Kim2024). These units structure everyday social interaction, local political engagement, and access to public resources, thereby shaping the environments in which political attitudes and partisan orientations are formed (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Johnston and Lown2015; Szewczyk and Crowder-Meyer, Reference Szewczyk and Crowder-Meyer2022).

The appropriate spatial scale for identifying contextual political effects remains contested in the literature (Velez and Wong, Reference Velez and Wong2017). The present analysis does not treat the si-gun-gu as a universally optimal unit of analysis, but rather as a substantively appropriate scale in the Korean context. Korea’s relatively high degree of ethnic and racial homogeneity reduces many of the demographic cleavages that complicate electoral geography in Western settings, increasing the salience of administrative and regional boundaries as organising features of political identity (Heikkila, Reference Heikkila2005). Survey evidence further suggests that local administrative units function as meaningful social reference points. According to the Korea Institute of Public Administration (2022), more than 70 per cent of Koreans report a strong sense of attachment to their si-gun-gu, reflecting dense patterns of social interaction and locally embedded political participation. Overall, these considerations indicate that the local administrative unit constitutes a plausible and sociologically grounded context for examining how economic inequality is perceived and reflected in electoral outcomes.

The local administrative–level analysis uses data from five national elections held between 2012 and 2022, including three presidential elections (2012, 2017, and 2022) and two National Assembly proportional representation elections (2016 and 2020). The analysis begins in 2012, the earliest year for which consistent local administrative data on economic inequality are available. The dependent variable is the percentage of votes received by the conservative People Power Party in each of Korea’s 252 si-gun-gu administrative units, allowing for consistent comparison of conservative support across election types and variation in partisan outcomes across local contexts.

The key explanatory variable, local economic inequality, is derived from administrative records produced by the Korean National Health Insurance System (NHIS). The NHIS publishes data on health insurance contributions aggregated at the si-gun-gu level, which corresponds exactly to the local administrative units used by the National Election Commission in reporting official election results. This correspondence ensures that measures of inequality and electoral outcomes are defined over the same geographic units, reducing potential inconsistencies arising from spatial mismatch. Because enrolment in the NHIS is mandatory and covers more than 97 per cent of the population (Heo et al., Reference Heo, Jeong, Lee and Seo2021; Han, Reference Han2024b), contribution data provide broad population coverage. Contributions are assessed based on a combination of wages, income, and asset ownership, which allows them to reflect local economic capacity more comprehensively than income measures alone. The NHIS reports these contributions in ten decile groups for each local administrative unit, making it possible to examine the distribution of economic resources within places rather than relying solely on average levels.

Local economic inequality is operationalised using the Palma ratio, which compares the share of total health insurance contributions made by the top ten per cent of contributors with that made by the bottom forty per cent within each local administrative unit. This measure captures concentration at the upper and lower ends of the local distribution and is less sensitive to variation around the middle. As such, it is particularly appropriate for analysing political contexts in which inequality at the extremes is expected to be salient. Recent research emphasises that local distributions of economic resources shape political attitudes and behaviour through relative comparison and contextual exposure rather than through individual income alone (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Johnston and Lown2015; Szewczyk and Crowder-Meyer, Reference Szewczyk and Crowder-Meyer2022). The Palma ratio is well suited to this perspective because it directly reflects the degree of top–bottom concentration that structures perceived advantage and disadvantage within communities (Cobham et al., Reference Cobham, Schlögl and Sumner2016). Consistent with the theoretical framework of this study, which highlights the role of subjective evaluations of social position, this distribution-based measure allows the analysis to examine whether localities characterised by greater economic dispersion are systematically associated with higher levels of conservative support.Footnote 1

The local administrative–level analysis includes a set of control variables designed to account for alternative explanations of voting behaviour. Several of these variables parallel those used in the individual-level models, but are aggregated to characterise each si-gun-gu. Local economic affluence is measured using the mean national health insurance premium per administrative unit, which reflects income and asset ownership and is log-transformed to reduce skewness.

Demographic structure is captured through measures of sex ratio, average age, education ratio, and urbanisation (Han, Reference Han2024c). These variables reflect population composition, educational attainment, and the degree of urban influence. Additional controls include the homeownership ratio, which captures the political relevance of property ownership and its link to asset-based conservatism (Han and Kwon, Reference Han and Kwon2024), and voter turnout, included because of its established association with partisan outcomes in Korea (Lee and Hwang, Reference Lee and Hwang2012).

The models also include an indicator distinguishing presidential from legislative elections to account for institutional differences between election types (Kim, Reference Kim, Poguntke and Hofmeister2024; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Lee and Hur2022), with election years modelled separately to capture year-specific contexts. Finally, regional dummy variables for the Seoul Metropolitan region, Honam, Yeongnam, Gangwon, and Chungcheong are included to account for Korea’s enduring political geography, with Sejong City as the reference category (Lee and Brunn, Reference Lee and Brunn1996; Moon, Reference Moon2005). Descriptive statistics are reported in Appendix A.

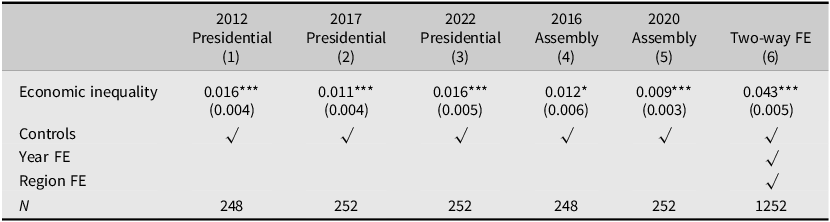

Table 3 reports the results of the local administrative–level analysis assessing the relationship between economic inequality and support for conservative parties. Models 1 through 5 present independent OLS estimations for three presidential elections (2012, 2017, and 2022) and two proportional representation elections for the National Assembly (2016 and 2020). Estimating the models separately allows for comparisons across different institutional and temporal contexts while maintaining a consistent model structure.

Table 3. Economic inequality and voting for the conservative party, proportional elections

Model 6 employs a two-way fixed effects specification that includes local administrative unit fixed effects and year fixed effects. This specification controls for unobserved, time-invariant characteristics of local administrative units as well as common temporal shocks affecting all units in a given election year. By accounting for these sources of heterogeneity, the model leverages within–local administrative unit variation in economic inequality to examine its association with changes in conservative vote share over time.

Across all six models, the coefficient for economic inequality is positive and statistically significant. Local administrative units with higher levels of inequality tend to exhibit higher levels of conservative vote share. This association is observed in both presidential and legislative elections and persists with the inclusion of local administrative unit and year fixed effects. The consistency of the estimated coefficients across specifications is broadly consistent with the theoretical expectation that higher levels of inequality are associated with stronger conservative alignment. Together, these results suggest that inequality is linked not only to material differentiation but also to localised political patterns, potentially through perceptions of relative advantage and disadvantage within communities.

Examination of the control variables (Appendix B, Table B5) provides further insight into the spatial and historical foundations of Korean voting behaviour. The regional dummy variables reaffirm the enduring influence of regionalism on electoral outcomes. Honam shows a strong and statistically significant negative association with conservative vote share, indicating its long-standing alignment with progressive parties, while Yeongnam displays a positive and significant association, consistent with its role as a conservative base. These relationships remain robust after accounting for local inequality, economic status, education, homeownership, and other demographic factors. The persistence of such patterns suggests that Korea’s electoral geography continues to embody historically grounded political identities and institutional legacies that interact with, but do not supplant, class- and inequality-based divisions.

Besides, although presidential and legislative elections differ in institutional structure, salience, and campaign dynamics, the inclusion of an election-type indicator and year-specific estimations helps account for these contextual distinctions. The results show that the positive association between inequality and conservative vote share persists across both electoral arenas. This consistency does not imply that presidential and legislative contests operate in identical ways; rather, it demonstrates that the broader mechanism linking local inequality to conservative alignment, grounded in perceptions of stability, growth, and order, operates within both institutional settings. The consistent results across different election types strengthen this study’s argument by showing that the observed relationship is not confined to a single electoral context but reflects a more general pattern in Korean political behaviour.

To assess whether spatial dependence affects the local administrative–level estimates, Moran’s I statistics were calculated for the residuals of the main models using a first-order queen contiguity matrix based on si-gun-gu boundaries. The test results do not indicate statistically significant spatial autocorrelation in the residuals (Moran’s I = 0.03, p = 0.27). This finding suggests that, after accounting for observed covariates and fixed effects, remaining unexplained variation in conservative vote share does not exhibit systematic spatial clustering across neighbouring local administrative units. Accordingly, the estimated association between local inequality and conservative vote share is unlikely to be driven primarily by unmodeled spatial dependence.

The fixed effects estimates indicate that the observed patterns are not driven solely by cross-sectional differences across local administrative units. Within-unit changes in economic inequality over time are associated with changes in conservative vote share, suggesting that localised disparities have persistent political associations beyond static regional characteristics. This pattern is observed across multiple election cycles and is consistent with the view that inequality operates through both spatial and temporal dimensions of electoral competition.

When considered alongside the individual-level analysis, the results point to a consistent set of associations between inequality, subjective class identification, and conservative alignment. At the individual level, subjective class identification is associated with vote choice, with respondents identifying as either the upper or lower class more likely to support conservative parties than those identifying as the middle class. At the local administrative level, higher levels of inequality are associated with greater aggregate conservative vote share. Taken together, these findings suggest that contexts characterised by higher inequality tend to coincide with weaker identification with the subjective middle and stronger alignment at the perceived ends of the class structure.

Overall, the local administrative–level results provide empirical support for the theoretical argument advanced in this study. They show that inequality functions not only as a structural condition but also as a contextual influence that shapes how voters interpret and respond to their social environment. In Korea, where historical cleavages remain powerful, the political effects of inequality manifest through both perception and place, reinforcing conservative stability within a formally competitive democratic system.

5. Conclusion

This study examined the relationship between economic inequality and voting behaviour by focusing on how subjective class consciousness mediates this relationship in Korea. In the context of widening inequality across democratic societies, the analysis proposed a framework that extends beyond conventional models of class voting. Rather than viewing class as a fixed and purely structural category defined by income or occupation, this study emphasised the importance of subjective class perceptions, understood as socially constructed evaluations shaped through relative comparison and social interaction.

The theoretical argument advanced in this study posits that inequality shapes political alignment through symbolic and perceptual processes rather than through objective position alone. As inequality increases, distinctions between perceived upper and lower classes become more salient, with class identity defined increasingly by relative self-placement within the social hierarchy. These perceptions are associated with different political orientations. Individuals who identify as subjectively upper class tend to support conservative parties linked to institutional continuity and the protection of established advantages. Those who identify as subjectively lower class may also align with conservatism, not primarily on economic grounds, but in response to concerns about social order, belonging, and stability in contexts of constrained mobility. By contrast, lower levels of inequality and narrower perceived social distance are more conducive to identification with a broad subjective middle class, an orientation commonly associated with social trust, civic engagement, and receptiveness to progressive political agendas.

Empirically, this study combines individual- and local administrative–level analyses to evaluate the proposed theoretical perspective. At the individual level, the results indicate that respondents who perceive themselves as either upper or lower class are more likely to support conservative parties, whereas those identifying as middle class are less inclined to do so. At the local administrative level, analysis of five national elections between 2012 and 2022 shows that units characterised by higher levels of economic inequality tend to exhibit stronger conservative vote shares. Overall, these findings are consistent with the argument that inequality shapes political alignment by altering how individuals perceive their relative social position and by structuring the local contexts in which such perceptions are formed.

Beyond its empirical findings, this study underscores the analytical value of incorporating subjective dimensions into the study of class politics. Objective indicators of socioeconomic position capture important structural differences but do not fully account for how inequality is experienced or translated into political behaviour. Subjective class identity introduces a relational perspective that helps explain how individuals interpret their position within a stratified social order and how these interpretations shape political preferences.

The Korean case illustrates the importance of situating theories of class and political behaviour within specific historical and institutional contexts. Korea’s trajectory of late industrialisation, authoritarian development, and persistent regional cleavages complicates assumptions derived from Western models of class politics. The findings suggest that the political consequences of inequality are mediated by country-specific social legacies, ideological divisions, and institutional arrangements rather than following a uniform pattern across democracies.

Recent research on asset-based inequality in Korea further indicates that property ownership and inheritance have become central to class differentiation, often rivalling income as markers of social position (Lee and Han, Reference Lee and Han2025; Song and Kang, Reference Song and Kang2025). As housing and real estate increasingly underpin economic security, intergenerational disparities have widened, making asset ownership a salient component of perceived class standing. Younger cohorts facing constrained mobility and limited access to property (Han, Reference Han2022b) may therefore interpret class position in more symbolic terms. Such orientations are consistent with research linking status anxiety and symbolic compensation to political identification when material advancement appears less attainable (de Botton, Reference de Botton2004; Pybus et al., Reference Pybus, Power, Pickett and Wilkinson2022; Parker and Lavine, Reference Parker and Lavine2025; Sears, Reference Sears, Lau, Tyler and Allen1980). In this sense, the Korean case suggests that, under conditions of sustained inequality, class politics may increasingly involve symbolic negotiation alongside material contestation.

Several limitations of this study point to directions for further research. First, although the analysis highlights systematic associations between inequality, subjective class identification, and political behaviour, it cannot establish causal ordering between these factors. The individual-level analysis relies on repeated cross-sectional survey data, which limits the ability to assess how changes in perceived class position unfold over time or how such changes translate into subsequent political attitudes and vote choice. Longitudinal or experimental designs would be better suited to disentangling the dynamic relationship between objective inequality, subjective interpretations, and political behaviour.

Second, the theoretical mechanisms proposed in this study are developed in the context of Korea’s specific historical and institutional setting. While the findings suggest that symbolic responses to inequality may operate differently among those who perceive themselves as advantaged and disadvantaged, it remains an open question whether similar patterns hold in other late-industrial or post-authoritarian democracies. Comparative analyses across institutional contexts would help assess the broader applicability of the mechanisms identified here.

Third, several measurement choices necessarily involve simplification. This study adopts a bloc-level approach to partisan alignment rather than modelling the full distribution of party competition. Classifying the People Power Party as conservative and the Democratic Party of Korea as progressive reflects the dominant structure of electoral competition in Korea, but it does not capture the full complexity of partisan alignments, particularly in legislative elections where minor parties play a more visible role. Similarly, subjective class identification is measured using a single self-placement item. This measure allows for comparability across survey waves but cannot fully represent the multidimensional and context-dependent character of class identity.

The measure of economic inequality based on health insurance contributions also has limitations. Although NHIS data offer comprehensive coverage and reflect multiple dimensions of economic capacity, contribution rules differ across employment categories, and certain groups, such as elderly or exempt households, may be measured imperfectly. Future research could strengthen measurement by incorporating alternative indicators of inequality, including wealth, housing prices, or asset distributions, as well as by exploring different definitions of local context, such as commuting zones or labour market areas.

Finally, the individual- and aggregate-level analyses cannot be directly linked because the KGSS does not provide identifiers for local administrative units. As a result, the local administrative–level findings should be interpreted as contextual associations rather than individual-level causal effects. To address potential ecological inference concerns, the aggregate models include extensive compositional controls, regional fixed effects, and diagnostic tests indicating no significant spatial autocorrelation. Future studies using geocoded survey data or multilevel designs would allow for a more direct examination of cross-level mechanisms connecting local inequality, subjective class perceptions, and individual vote choice.

Overall, the findings presented in this study highlight that class remains a relevant yet increasingly complex dimension of democratic politics. By centring subjective class consciousness in the analysis of inequality and voting behaviour, the present study provides a framework for understanding how perceptions of social position shape political preferences in an era marked by widening disparities and evolving political alignments.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1468109925100224

Data availability statement

All data used in this study are shared at Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WC1T6Q).

Funding statement

This study received no funding.

Competing interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.