Introduction

Noug (Guizotia abyssinica L.) is the most popular and native oilseed crop in Ethiopia, grown for its edible oil and seeds. It is mainly grown by smallholder farmers and contributes half of the Ethiopian oilseed production (Geleta and Ortiz Reference Geleta and Ortiz2013; Tsehay et al. Reference Tsehay, Ortiz, Geleta, Bekele, Tesfaye and Johansson2021; Gebeyehu et al. Reference Gebeyehu, Hammenhag, Tesfaye, Ortiz and Geleta2024). Roasted noug seeds are eaten mixed with pulses, roasted cereals and flour to make sweet cakes. The oil is used in cooking, painting, soap and as an illuminant. Ethiopian farmers prefer growing noug because it requires minimal management due to its low response to management inputs (Getinet and Sharma Reference Getinet and Sharma1996; Teklewold and Wakjira Reference Teklewold and Wakjira2004; Adarsh et al. Reference Adarsh, Poonam and Shilpa2014).

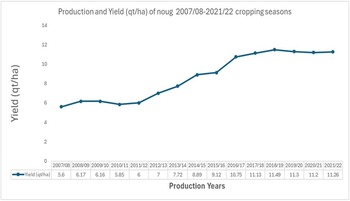

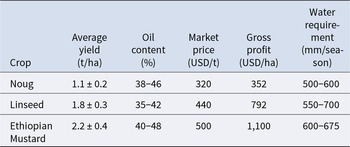

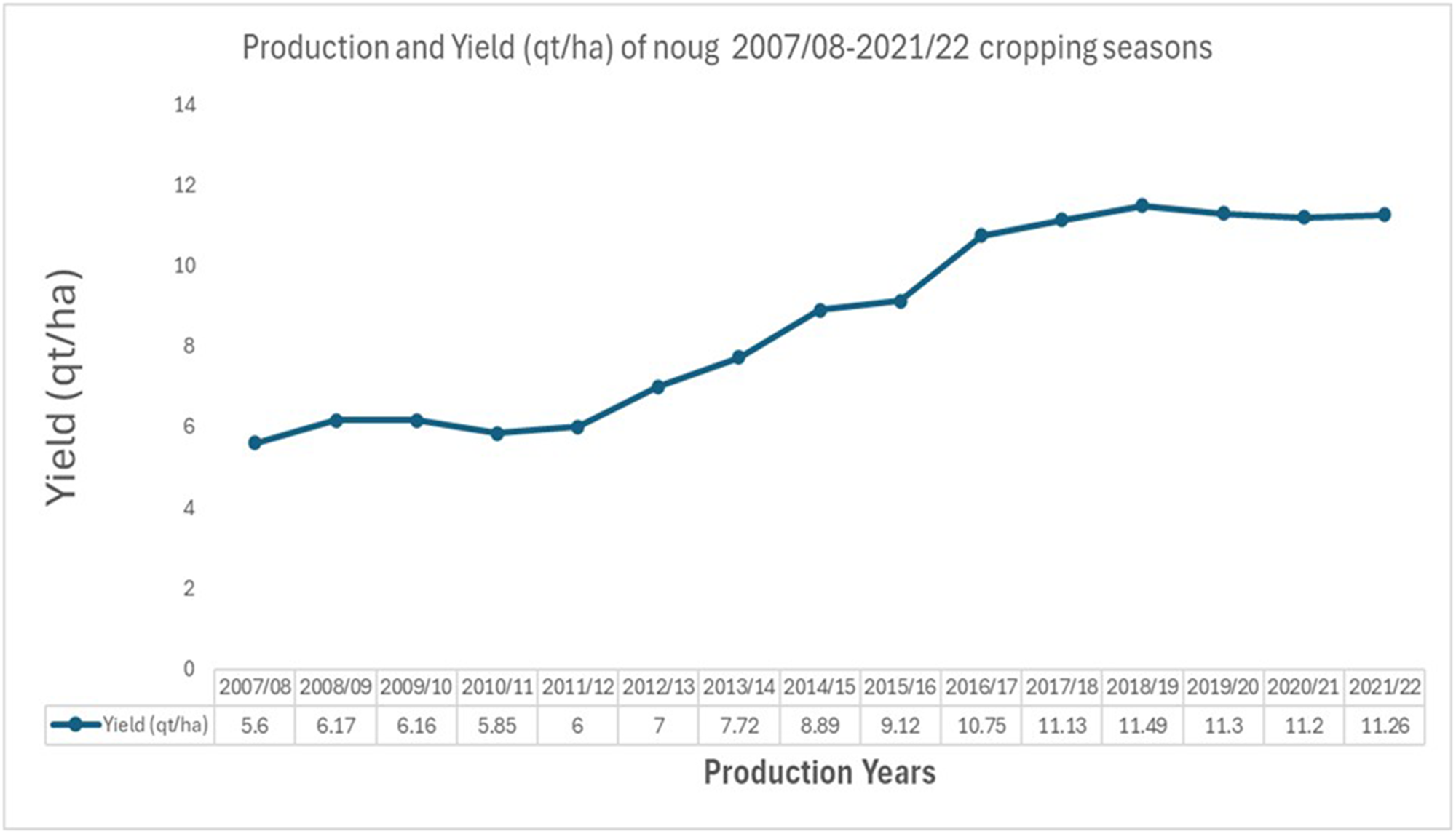

Noug’s national average productivity is about 1.1 tons (t) per hectare (CSA 2021). Recently, noug has been added to the list of Ethiopian Commodity Exchange (ECX) traded commodities, which is expected to create better market incentives for farmers to scale up seed production in the coming years. Furthermore, expansion in local edible oil processing facilities and new integrated agro-industries within the country also spur the demand to produce noug to meet the rapidly increasing local demand for cooking oils and animal feed (Ethiopian Investment Commission (EIC) 2023; Ethiopian Pulses, Oilseeds and Spices Processors-Exporters Association (EPOSPEA) 2023). The expansion of acreage (CSA 2021; USDA-GAIN Reference Bickford2021; Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) 2022) and improved yields due to good weather conditions (Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) 2022) were expected to increase noug production by nearly 2% (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Trends of an average yield increase of noug in the last 15 years in Ethiopia.

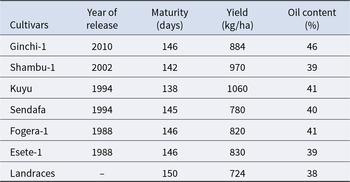

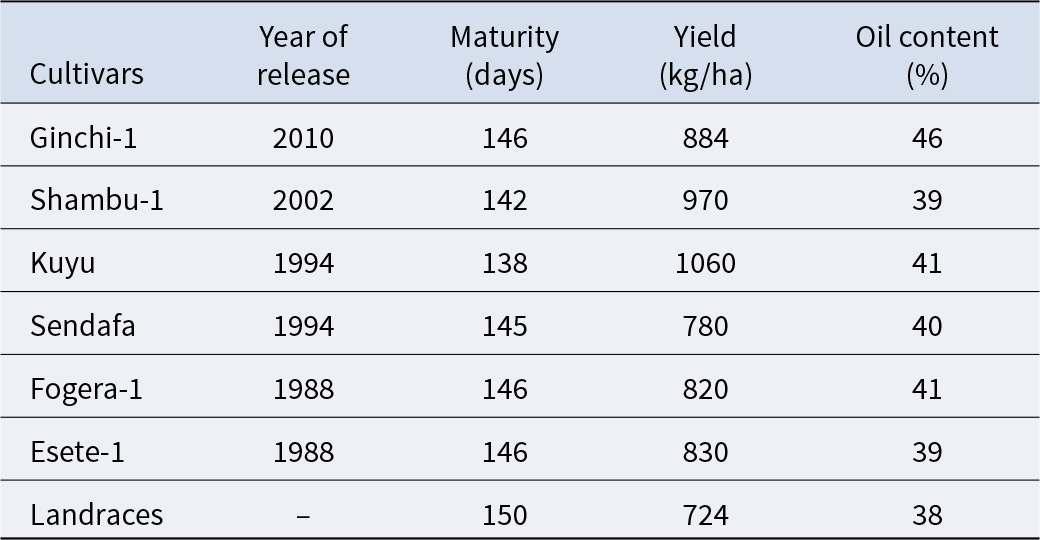

However, its cultivation is plagued by several critical problems (Geleta and Ortiz Reference Geleta and Ortiz2013; Tsehay et al. Reference Tsehay, Ortiz, Geleta, Bekele, Tesfaye and Johansson2021). The key factors include susceptibility to pests, diseases, parasitic weeds, pod shattering and low yields (Getinet and Sharma Reference Getinet and Sharma1996; Teklewold and Wakjira Reference Teklewold and Wakjira2004; Tesfaye Reference Tesfaye2007; Gebeyehu et al. Reference Gebeyehu, Hammenhag, Ortiz, Tesfaye and Geleta2021). This critical review is timely because, after a decade of extensive genomic progress, including the development of self-compatible (SC) lines, transcriptomic resources, and preliminary quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping, there have been no new improved cultivars released in Ethiopia since 2010 (Table 2). This indicates a significant translational gap. The novelty of this review is that it brings together these new developments and its proposal of a concrete, holistic route to overcome the key limitations of self-incompatibility, lodging and shattering and, therefore, positions noug as an adoptable and sustainable crop for Ethiopia.

Overview of noug as an oilseed crop

Taxonomy and botany

Noug is a diploid (2n = 30), dicotyledonous, herbaceous annual plant in the Compositae family. It is characterized by strict outcrossing and self-incompatibility. The domesticated crop, Guizotia abyssinica, is near and cross-compatible with its wild relative, Guizotia scabra, an abundant weed in Ethiopia (Dagne Reference Dagne1994, Reference Dagne1995; Geleta Reference Geleta2007). Comprehensive taxonomic treatments are given in detail (e.g., Getinet and Sharma Reference Getinet and Sharma1996; Geleta Reference Geleta2007).

Origin and distribution

Noug is native to the Ethiopian highlands, which is guaranteed as its origin and diversity pointer by the presence of wild relatives. It was domesticated from Guizotia scabra subsp. Schimperi was introduced to India centuries ago (Getinet and Sharma Reference Getinet and Sharma1996; Dempewolf et al. Reference Dempewolf, Tesfaye, Teshome, Bjorkman, Andrew, Scascitelli, Black, Bekele, Engels, Cronk and Rieseberg2015). In Ethiopia, it is grown mostly by small-scale farmers at mid-to-high altitudes (1600-2500 masl) in regions including Gojjam, Gondar, and Wellega. The Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute has conserved over 1170 germplasm accessions (Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute (EBI) 2025).

Economic values

Noug is an economically important oilseed crop for domestic consumption by households. It also generates income for farmers, foreign exchange earnings, and import substitution of about $50–60 million annually from edible oil imports (Abebe et al. Reference Abebe, Alemu and Tesfaye2022). Furthermore, the oilcake remaining after oil extraction serves as high-quality animal feed (Getinet and Sharma Reference Getinet and Sharma1996; Deme et al. Reference Deme, Haki, Retta, Woldegiorgis and Geleta2017). It is the main source of edible oil for the local consumption of millions of Ethiopians. Its seed is used as bird food in the United States and Europe, especially for finches (Petros et al. Reference Petros, Merker and Zeleke2008). It is also used in soap making and as a scent carrier in the perfume industry (Seegler, Reference Seegler1983; Kandel and Porter, Reference Kandel and Porter2002). Noug oil also protects against cardiovascular diseases and treats burns (Adarsh et al. Reference Adarsh, Poonam and Shilpa2014).

Nutritional profile

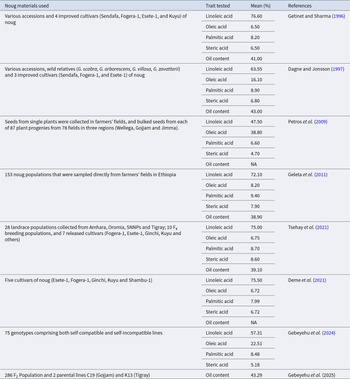

Noug oil is characterized by a high level of unsaturated fatty acids, with linoleic acid being the predominant component, followed by oleic acid. The primary saturated fatty acids are stearic and palmitic (Table 1). The Ethiopian noug materials exhibit significant oil content and quality variation depending on the seeds’ maturity level, the materials’ origin, and climatic conditions, especially temperature (Petros et al. Reference Petros, Carlsson, Stymne, Zeleke, Fält and Merker2009; Geleta et al. Reference Geleta, Stymne and Bryngelsson2011; Tsehay et al. Reference Tsehay, Ortiz, Geleta, Bekele, Tesfaye and Johansson2021; Gebeyehu et al. Reference Gebeyehu, Hammenhag, Tesfaye, Ortiz and Geleta2024). It is also a good source of protein (25–28%) and macro- and micro-minerals that can significantly combat malnutrition (Tsehay et al. Reference Tsehay, Ortiz, Geleta, Bekele, Tesfaye and Johansson2021). It contains mineral elements P, K, Ca, Mg, S, Na, B, Cu, Fe, Mn, Se and Zn (Deme et al. Reference Deme, Haki, Retta, Woldegiorgis and Geleta2017; Tsehay et al. Reference Tsehay, Ortiz, Geleta, Bekele, Tesfaye and Johansson2021). The mineral composition of noug suggests its possible contribution towards the mitigation of high levels of micronutrient malnutrition in Ethiopia. For example, its zinc and iron composition would be in support of controlling high rates of iron deficiency among lactating mothers (Roba et al. Reference Roba, O’Connor, Belachew and O’Brien2018) and stunting due to zinc deficiency in children (Harika et al. Reference Harika, Faber, Samuel, Kimiywe, Mulugeta and Eilander2017; Ayana et al. Reference Ayana, Moges, Samuel, Asefa, Eshetu and Kebede2018). Clinical trials confirm that noug oil taken daily improves lipid profiles by reducing cholesterol by 12–18% (Gebremariam et al. Reference Gebremariam, Alemu and Abay2024), and Fe (29.6 mg/100 g) and Zn (8.2 mg/100 g) present therein directly fight prevalent micronutrient deficiencies among Ethiopian populations (Ayana et al. Reference Ayana, Moges, Samuel, Asefa, Eshetu and Kebede2018; Berhanu et al. Reference Berhanu, Mekonnen and Sisay2018; Roba et al. Reference Roba, O’Connor, Belachew and O’Brien2018). This is in line with the Agricultural Transformation Plan of Ethiopia (2021–2030), which strongly focuses on nutrient-dense indigenous foods like noug towards improving food security (Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) 2021). Public health programs based on noug products can therefore enhance dietary diversity and help achieve national agricultural targets, as encouraged by FAO’s 2023 policy guidelines on underutilized crops for nutrition security (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO 2023). Hence, noug should be increasingly used as a food source for oil, protein, and minerals in Ethiopia and elsewhere to enhance human wellness.

Table 1. Composition (%) of major fatty acids and oil content in Ethiopian noug materials

NA = not available.

Noug genetic resources enhancement

Systematic genetic improvement of noug in Ethiopia was initiated in 1961, with preliminary breeding already underway in the Debrezeit and Holeta Agricultural Research Centres (Alemaw and Alemayehu Reference Alemaw and Alemayehu1992). Throughout the next three decades, the program resulted in the release of four principal cultivars: Sendafa, Fogera-1, Esete-1 and Kuyu by 1994 (Getinet and Sharma Reference Getinet and Sharma1996). Since 1995, only two improved cultivars of noug (Ginchi-1 and Shambu-1) have been released. However, only six improved cultivars are still being developed by selection (Table 2) and released in different years (Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) 2016). The absence of new cultivar releases since 2010 starkly illustrates the limitations of conventional breeding and underscores the urgent need for innovative approaches.

Table 2. Lists of improved cultivars, year of release, maturity, yield and oil content

Data Source: Getinet and Sharma (Reference Getinet and Sharma1996) and Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) (2016).

Conventional breeding in noug

In Ethiopia, conventional breeding of noug cultivars is mostly on-farm farmer selection of high-yielding plants with improved oilseed yield and quality (Geleta and Ortiz Reference Geleta and Ortiz2013). Farmers save seeds from top-performing plants and have achieved documented genetic advances. Studies show that this participatory breeding approach has raised seed oil content by 3–5% and yield stability by 15–20% in local landraces within a decade (Terefe et al. Reference Terefe, Birmeta, Girma, Geleta and Tesfaye2023). Similar success has been described in other indigenous oilseeds like sesame (Rauf et al. Reference Rauf, Basharat, Gebeyehu, Elsafy, Rahmatov, Ortiz and Kaya2024) and Ethiopian mustard (Ambaw et al. Reference Ambaw, Abitea, Olango and Molla2025), showing the relevance of combining traditional and conventional breeding practices.

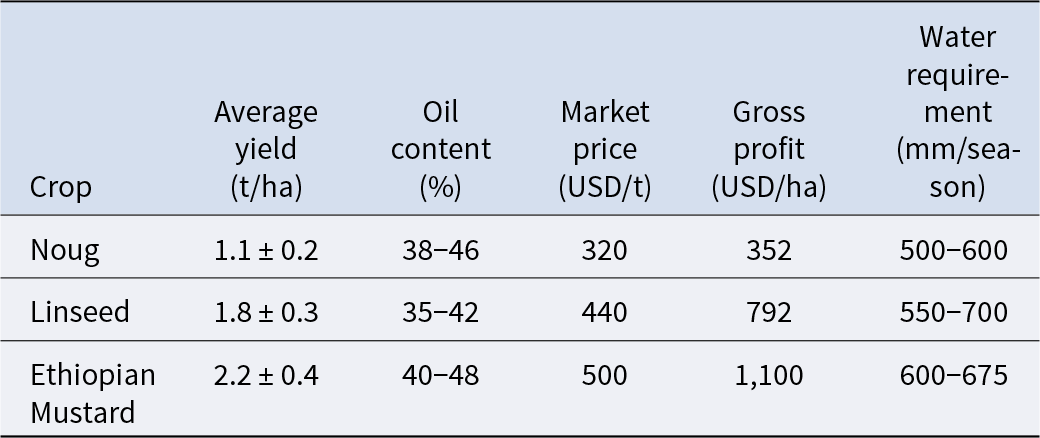

However, the yield of noug is economically uncompetitive with major oilseeds, necessitating further improvement (Table 3). The Ethiopian national averages present noug yields less than linseed and Ethiopian mustard under similar growing conditions (CSA 2021; Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) 2022). A yield gap of this size translates into a substantial profitability disadvantage, with noug grossing $440–748 less per hectare than linseed and Ethiopian mustard (ECX 2023; Abebe et al. Reference Abebe, Alemu and Tesfaye2022). One of the major issues hindering noug is its comparatively lower economic competitiveness compared to other oilseeds like linseed and Ethiopian mustard with higher average yield and gross profit per hectare under the same Ethiopian environmental conditions (Table 3; CSA 2021; Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) 2022). This yield gap gives a serious profitability disadvantage to farmers (ECX 2023; Abebe et al. Reference Abebe, Alemu and Tesfaye2022). One of the most crucial morphological restraints is the architecture of the plant; while additional branching can be associated with increased potential for yield, over-vegetative growth is likely to lead to lodging, hence effectively reducing seed yield (Getinet and Sharma Reference Getinet and Sharma1996; Tesfaye Reference Tesfaye2007). Modern breeding, therefore, not only aims to increase the yield and oil content (Tesfaye Reference Tesfaye2007) but also to modify plant architecture. Genetic selection for smaller, less-branched plants could also improve harvest index and lodging resistance (Belayneh Reference Belayneh1987), making yield advances more reliable and predictable.

Table 3. Agronomic and economic performance of major oilseed crops in Ethiopia (2019–2023)

Data source: (Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) 2022).

Seed oil content is another major trait in the noug breeding program. Fortunately, Ethiopian and Indian germplasm collections harbour considerable genetic variation for this trait, representing a valuable source of material for breeding programs looking to enhance oil content (Alemaw and Teklewold Reference Alemaw and Teklewold1995; Tesfaye Reference Tesfaye2007; Gebeyehu et al. Reference Gebeyehu, Hammenhag, Tesfaye, Ortiz and Geleta2024). Single-head and dwarf-type noug cultivars must be developed to reduce seed loss from shattering. Production of single-headed plants is more desirable than many heads per plant due to the variation among many heads (Tesfaye Reference Tesfaye2007; Gebeyehu et al. Reference Gebeyehu, Hammenhag, Ortiz, Tesfaye and Geleta2021). According to Gebeyehu et al. (Reference Gebeyehu, Hammenhag, Ortiz, Tesfaye and Geleta2021), tall cultivars with a plant height of 120–180 cm and with 3–5 heads per plant shatter 25–30%, which was observed in field trials conducted at Debrezeit research centre. In contrast, dwarf types (70–90 cm) with 1–2 heads per plant have 10–15% losses due to better resistance to lodging. Single-head cultivars with a plant height of 100–130 cm perform well in terms of shattering (8–12%) and maturity due to synchronization of maturation time (Gebeyehu et al. Reference Gebeyehu, Hammenhag, Ortiz, Tesfaye and Geleta2021). These cultivars performed the best, combined with limited shattering and synchronized maturity. Besides, dwarf plants may be more effective in fertilizer use than tall ones (Tesfaye Reference Tesfaye2007; Gebeyehu et al. Reference Gebeyehu, Hammenhag, Ortiz, Tesfaye and Geleta2021). Application of fertilizer may result in increased yields of seeds (Getinet and Sharma Reference Getinet and Sharma1996). Fertilizing the taller noug plants may, sometimes, result in a negative response since it stimulates vegetative growth, which causes lodging in the crop (Gebeyehu et al. Reference Gebeyehu, Hammenhag, Ortiz, Tesfaye and Geleta2021). Hence, breeding programs should focus on developing compact, single-headed genotypes to improve the noug yield potential.

Breeding programs in Ethiopia and India claim that breeders themselves began such population improvement methods, which is quite plausible. Simple mass selection had improved a few populations in Ethiopia (Riley and Belayneh, Reference Riley and Belayneh1989; Getinet and Sharma, Reference Getinet and Sharma1996), and recurrent selection with participatory breeding efforts on crops like sorghum, pearl millet and chickpea is reported from India (Rai and Witcombe, Reference Rai, Murty, Andrews and Bramel-Cox1999; Saxena et al. Reference Saxena, Thudi and Varshney2016). The two countries’ approaches to population improvement capture a larger trend.

Selection

Mass selection is a basic and effective breeding method, especially for highly heritable and largely additive gene-controlled traits such as plant height, days to maturity, lodging resistance and oilseed yield (Alemaw and Teklewold Reference Alemaw and Teklewold1995; Allard Reference Allard1999; Acquaah Reference Acquaah2012). Mass selection approaches have also been found to be used in the breeding of noug to create unique genotypes with superior agronomic traits (Dagne and Jonsson Reference Dagne and Jonsson1997).

Recurrent selection is a widespread breeding technique that has been applied in cross-pollinated species for the development of open-pollinating varieties (OPVs) or cultivars because it allows for the accumulation of beneficial alleles while keeping the diversity among them (Poehlman and Sleper Reference Poehlman and Sleper1995; Acquaah Reference Acquaah2012). The common practice is choosing elite plants for target traits, blending equal portions of their seeds, growing them in isolation to facilitate intercrossing, saving seed from chosen plants, and field-testing progeny rows in future breeding cycles (Hallauer et al. Reference Hallauer, Carena and Miranda Filho2010). This method is based on the fundamental principle of increasing allele frequency for quantitative inherited traits at each cycle, particularly for polygenic characters with significant additive genetic variance (Falconer Reference Falconer1996; Allard Reference Allard1999; Bernardo Reference Bernardo2002). In noug, both mass and half-sib recurrent selection were found to be very effective in creating significant genetic gains for yield, adaptation traits, and economic traits like early-to-medium maturity, larger head size and reduced plant height (Alemaw and Teklewold Reference Alemaw and Teklewold1995; Getinet and Sharma Reference Getinet and Sharma1996).

Crossing

Similar to sunflower, noug exhibits a high outcrossing pollination behaviour (Getinet and Sharma Reference Getinet and Sharma1996). Because of its floral biology and naturally high outcrossing rate (30–50%; Lavania, 2005), it is a good candidate for hybrid breeding, where heterosis was successfully exploited in related Asteraceae crops like sunflower (Rathod et al. Reference Rathod2013). Flowers of two parental lines can be rubbed with each other to obtain controlled crosses (Rilay and Belayneh, 1989), though it may result in self-pollination owing to incomplete emasculation. To achieve F1 hybridization, the researchers suggest that disc florets (male organs) should be removed at the bud stage and ray florets (female) kept whole, a technique adapted from sunflower breeding procedures (Getinet and Sharma Reference Getinet and Sharma1996).

Modern breeding in noug

One of the biggest challenges to noug improvement is its obligate outcrossing through self-incompatibility (Geleta and Ortiz Reference Geleta and Ortiz2013). This is because this makes breeding harder by preventing the establishment and maintenance of pure inbred lines, which is an important step in most contemporary breeding programs. This is due to the limited number and type of pollinating agents and self-incompatibility. The crop’s indeterminate nature makes it liable for shattering (Nemomissa et al. Reference Nemomissa, Bekele and Dagne1999). Modern breeding approaches are therefore essential to overcome these intrinsic constraints.

Tissue culture

Tissue culture techniques, namely anther or microspore culture, offer a way to rapidly generate homozygous lines (haploids) that can be doubled to create pure lines, thus avoiding the self-incompatibility barrier (Forster et al. Reference Forster, Heberle-Bors, Kasha and Touraev2007). While protocols for callus induction and shoot regeneration from hypocotyls, cotyledons (Tesfaye Reference Tesfaye2007) and anthers (Misteru Reference Misteru2008) in noug exist, an efficient and reliable doubled haploid production system is not yet available. Development of such a system is a critical step towards the realization of genetic gain acceleration in noug breeding.

Molecular markers and marker-assisted selection

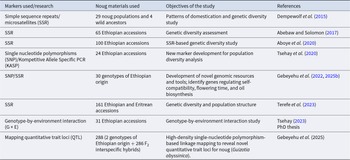

Molecular markers were important in the description of the vast genetic diversity of the noug germplasm (Table 4). The utilization, however, has been confined to diversity analysis via RAPD, AFLP, ISSR and SSR techniques. However, these markers have been restricted to such high-resolution genetic analysis and must be complemented with other high-throughput markers, which can be used for targeted marker-assisted selection (Collard and Mackill Reference Collard and Mackill2008). This is true and especially for the improvement of oilseed crops, as they proved their utility in marker-trait associations, which helped in accelerating genetic progress for yield and quality traits (Pandey et al. Reference Pandey, Pandey, Kumar, Nwosu, Guo, Wright and Zhuang2020). The recent SNP markers and transcriptomic resource development (Tsehay et al. Reference Tsehay, Ortiz, Johansson, Bekele, Tesfaye, Hammenhag and Geleta2020; Gebeyehu et al. Reference Gebeyehu, Hammenhag, Tesfaye, Vetukuri, Ortiz and Geleta2022) is a success. The grand challenge now is to move beyond diversity analysis to the application of such tools to marker-assisted selection (MAS). This requires the establishment of robust marker-trait relationships for key agronomic traits that are currently missing.

Table 4. Diversity study, genotype-by-environment interaction and mapping quantitative trait loci (QTL) in Ethiopian noug (Guizotia abyssinica) materials using different DNA markers

Linkage and QTL mapping

Noug is an outcrossing crop, and the production of inbred lines is consequently not feasible, though imperative as the foundation for linkage and QTL mapping (Dagne and Jonsson Reference Dagne and Jonsson1997). Development of SC lines (Geleta and Bryngelsson Reference Geleta and Bryngelsson2010) was an achievement, making the production of mapping populations possible. SC-genotypes were subsequently generated by cross- and selfing, which were used for RNA-seq-based sequencing (Gebeyehu et al. Reference Gebeyehu, Hammenhag, Tesfaye, Vetukuri, Ortiz and Geleta2022). To date, no study has established pure-line development with generational stability in noug. This limitation is in direct contrast to related oilseed crops, such as sunflower, for which pure lines have enabled significant advances in QTL mapping (Putt, 1997). Inability to develop stable pure lines is a main limitation for noug improvement (Tadele Reference Tadele2019). Linkage mapping in SC lines has recently identified the first QTL for oilseed yield and tolerance to stress (Gebeyehu et al. Reference Gebeyehu, Hammenhag, Tesfaye, Vetukuri, Ortiz and Geleta2025a). This is a first step, but the stability of these QTL over environments and genetic backgrounds needs to be established before they can be effectively applied in MAS.

Genome-wide association study

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are a potential alternative to linkage mapping in outcrossing species such as noug, as they can potentially make use of natural diversity without the need to develop inbred lines. GWAS would allow marker-trait associations to be detected by genotyping a diverse panel of germplasm together with high-density SNP markers. While no GWAS has been conducted in noug to date, it represents an enormous opportunity to unravel the genetic architecture of complex traits like yield, lodging and shattering with direct breeding implications.

Genome editing

Genome editing technologies, in particular CRISPR-Cas9, hold enormous potential for the precision improvement of orphan crops like noug. While no work has been reported in noug, its utility for removing undesirable traits (e.g., indeterminate growth genes or susceptibility to shattering) or enhancing desirable ones (e.g., oil quality genes) has been proven in very closely related oilseeds like sunflower and rapeseed. The two prerequisites for applying CRISPR in noug are a stable genetic transformation system and a sequenced genome. Initial transformation protocols exist (Murthy et al. Reference Murthy, Jeong, Choi and Paek2003), though genome sequencing needs to be prioritized in order to maximize the potential of genome editing.

Pathogens, weeds and pests in noug

Noug is economically relevant despite the fact that its productivity is still low due to biological and management issues. Severe limitations include low harvest index, seed lodging and shattering (Fig. 2), indeterminate growth type, self-incompatibility and weak sensitivity to inputs like fertilizer (Dagne and Jonsson Reference Dagne and Jonsson1997; Tesfaye Reference Tesfaye2007; Gebeyehu et al. Reference Gebeyehu, Hammenhag, Ortiz, Tesfaye and Geleta2021). The erect, branching growth habit of the plant and asynchronous head maturation of the flowers are the immediate causes of pre-harvest shattering and lodging losses, and one of the main yield losses (Getinet and Sharma Reference Getinet and Sharma1996; Gebeyehu et al. Reference Gebeyehu, Hammenhag, Ortiz, Tesfaye and Geleta2021).

Figure 2. A field of noug showing its typical tall, branched growth habit prone to lodging (A), and a close-up of the flower heads (B), illustrating the potential for shattering.

Although noug is reported to have relatively fewer biotic issues than other oilseeds like sunflower and sesame (Alemaw and Teklewold Reference Alemaw and Teklewold1995), its growth is also limited by some of the most significant pests and diseases. Some of the most widespread diseases are bacterial leaf spot (Xanthomonas spp.) and blight (Alternaria spp.), which have been reported to cause huge yield loss (Tadesse et al. Reference Tadesse2017). The crop’s productivity is also threatened by the insect pests, the noug fly (Dioynasorocula spp. and Eutretosoma spp.) and black pollen beetles (Meligethes spp.), that bring direct injury to flowers and reduce seed set (Tsehay et al. Reference Tsehay2023). Moreover, parasitic weeds are increasing. Dodder (Cuscuta campestris) is now becoming a serious concern in major noug-producing regions of Ethiopia (Terefe et al. Reference Terefe, Birmeta, Girma, Geleta and Tesfaye2023). But one more parasitic plant, Orobanche minor, is present, but so far has not been associated with widespread, serious damage (Getinet and Sharma Reference Getinet and Sharma1996; Tsehay et al. Reference Tsehay2023).

The most frequently observed diseases of noug include noug blight (Alternaria spp.), powdery mildew (Erysiphe spp.), bacterial leaf spots (Xanthomonas spp.) and shot holes (Getinet and Sharma Reference Getinet and Sharma1996; Tadesse et al. Reference Tadesse2017). Among these, shot hole disease (coryneum blight), caused by Wilsonomyces carpophilus, results in a 10% yield loss under severe infection conditions, as recorded at the Holeta Research Centre (Terefe et al. Reference Terefe, Birmeta, Girma, Geleta and Tesfaye2023). This disease is widespread in noug-growing areas with varying intensity across the Amhara and Oromia regions (Terefe et al. Reference Terefe, Birmeta, Girma, Geleta and Tesfaye2023).

Several species of noug insect pests have been reported, with noug flies (Dioynasorocula spp.), black pollen beetles (Meligethes spp.), aphids and thrips among the major ones requiring research priority in Ethiopia (Medhin and Mulatu, Reference Medhin and Mulatu1992). Noug flies alone reduce seed set by 15–20% (Medhin and Mulatu, Reference Medhin and Mulatu1992). Hence, noug improvement programs should emphasize the introduction and identification of pest and pathogen-resistant characters in improved cultivars to enhance yield stability and minimize yield losses. This can be achieved by: (i) systematically screening the extensive noug germplasm collections and wild relatives (G. scabra) for sources of resistance; (ii) employing marker-assisted selection to introgress identified resistance QTL into elite breeding lines; and (iii) exploring the possibilities of genetic engineering or genome editing to transfer resistance genes from other organisms if natural variation is found to be lacking.

Conclusions and future prospects

This review identifies a translational deficit of significance in noug improvement: whereas there has been the development of large genetic resources and genomic tools, their application to breeding programs has not been translated into new cultivars after over a decade. To bridge this gap and realize the potential of this strategic crop, there must be an integrated and combined effort. The future direction will need to target the development of dwarf, single-headed plant structures to address lodging and shattering head-on, and to speed up genetic advance by finishing doubled haploid systems to escape self-incompatibility. Application of proven QTL and conducting genome-wide association studies will be critical to evolve towards genomics-assisted breeding for significant traits. Moreover, exploration of the promise of genome editing technologies like CRISPR-Cas provides a frontier for precise genetic improvement. Lastly, the success of these efforts will lie in linking participatory variety selection with smallholder farmers so that new varieties are not only high-yielding but also suit local taste and agronomic conditions. Through this multi-modal route, Ethiopia stands to turn noug into a competitive, climate-tolerant staple of its oilseed sector, enhancing national food security and incomes for millions of smallholder farmers.