Although historically few democracies have failed in their attempts to replace their constitutions, in the past decade, constituent processes have increasingly failed (Zulueta-Fülscher Reference Zulueta-Fülscher2023). The case of Chile is paradigmatic, as it failed twice consecutively in the attempt to establish a new constitution. While previous studies have analyzed the failure of the first process, this article examines both attempts (the 2021–2022 Constitutional Convention and the 2023 Constitutional Council) to identify the causal mechanisms underlying this double failure.

The case is particularly interesting because the actors involved in the second process apparently failed to learn from the first, repeating the same patterns of behavior. From a theoretical perspective, the literature has emphasized three dimensions that shape such dynamics: the rules of the game, political contingencies, and electoral contingencies. Although we agree with some premises of this literature, we argue that it does not fully address the causal mechanisms explaining why political actors replicate these patterns. For example, it is convincingly argued that one critical factor in both processes was the balance of power achieved. In the first case, the left dominated the convention; in the second, the right dominated the council. Because the majority did not require minority votes to approve a text, the final drafts reflected only the interests of these circumstantial majorities. However, it remains necessary to determine why the actors chose not to include the minority to secure a favorable outcome at the ballot box in both cases.

The central question we seek to answer is why the actors failed to include the minority despite knowing that the text would require broad public approval. In both cases, the citizenry was called on to approve or reject the text, so, in theory, the actors should have focused on drafting a constitution acceptable to most citizens (over 50 percent +1 vote).

We propose to analyze these dynamics by examining the two levels at which these processes unfolded. At the first level, we identify common patterns in decision-makers’ actions, shaped by their perception of representing much of the country (despite evidence to the contrary) and by a frenetic bureaucratic-organizational dynamic that obscured the political-electoral consequences of their decisions. Once the proposed constitutional text was approved by the drafting council, an electoral process sought citizens’ support. In both cases, social confidence in the process was very low, and the electoral campaign heightened public fears, ultimately leading to failure.

The rest of the article proceeds as follows: We first present the theoretical framework explaining constituent dynamics, which is followed by an analysis of the Chilean case and the arguments developed in this study. Then, the results are discussed in terms of intraelite negotiations within the assemblies and the political-electoral dynamics. Finally, we offer conclusions and broader theoretical and policy implications.

Constituent dynamics: Theoretical framework

In our theoretical framework, we first review the literature that explains the structural conditions for the opening of constitutional change processes and the main factors contributing to their failure. Next, we focus on the Chilean case—an experience of two unsuccessful reform attempts—and we systematize the explanatory factors organized in three: the rules of the game, internal political contingencies, and socio-electoral contingencies. Each block gathers determinants that together make it possible to analyze the dynamics that shaped these processes.

There is an extensive literature that has reflected on the dynamics of constitutional change. Regarding the opening of constituent moments, it has been pointed out that there are favorable structural conditions (e.g., transitions to democracy, significant sociopolitical crises) that energize debate on constitutional rules. According to Negretto (Reference Negretto2013), a constitutional replacement occurs when governance structures fail or when the constitutional design prevents emerging forces from effectively exercising power (see also Sanchez Reference Sanchez-Urribarri2023).

Beyond this debate, in this article, we are interested in exploring the conditions and causal mechanisms that could explain the failure to adopt a new constitution once a process has begun. Concerning this, the literature identifies factors related to the institutional design, the distribution of power within deliberative bodies, the level of fragmentation and polarization within the political bodies, and the lack of trust among negotiating parties (Ebrahim Reference Ebrahim, Ginsburg and Bisarya2022; Ginsburg and Bisarya Reference Ginsburg, Bisarya, Ginsburg and Bisarya2022; Zulueta-Fülscher Reference Zulueta-Fülscher2023). Zulueta-Fülscher (Reference Zulueta-Fülscher2023, 13) highlights two dimensions within the intraelite bargaining process that are relevant for our work: first, an agreement is more likely “if a significant number of conflict parties agree on and commit to the proposed changes”; second, trust among opposing parties at the constitutional negotiation table appears crucial to reaching an agreement. As we show here, neither of these conditions was met in the Chilean constituent process.

Chile’s constituent process is a dual failed attempt to establish a new constitutional framework. Existing analyses have primarily focused on the first process. However, from these arguments, we can establish a theoretical framework to explain both processes. In general terms, and following the same arguments provided by the comparative literature, authors have highlighted three dimensions: the institutional design of the rules of the game, political contingencies within deliberative bodies, and socio-electoral contingencies. Certainly, some authors have provided interpretations that integrate these dimensions, but for the sake of clarity, we analyze them separately.

Design of the rules of the game

Regarding the rules of the game, it has been pointed out that the first constituent process incorporated an entry plebiscite, the election of the first convention with voluntary voting, and an exit plebiscite with mandatory voting. This meant that the representatives of the first convention were elected by a more left-wing electorate, because, following the 2019 social unrest, this sector was predominantly mobilized. However, when the exit plebiscite with compulsory voting took place, a more moderate middle voter was mobilized, shifting the result toward rejection (Larraín et al. Reference Larraín, Negretto and Voigt2023; Fuentes Reference Fuentes and Fuentes2023; Heiss and Suárez Reference Heiss and Suárez-Cao2024).

Another factor concerns the election rules of the first convention, which allowed the incorporation of many independents (67 percent of the convention) and led to greater fragmentation across twelve political groups (Heiss and Suárez Reference Heiss and Suárez-Cao2024; Rozas-Bugueño Reference Rozas-Bugueño2024). In addition, the rule for electing representatives was by nominal vote, where representatives sought to directly appeal to their electorate. This discouraged agreements between groups and promoted a charismatic, personalistic style of politics (Larraín et al. Reference Larraín, Negretto and Voigt2023).

Political contingencies within deliberative bodies

Authors who have analyzed the Chilean constitutional process have highlighted three dimensions regarding the political dynamics within the deliberative bodies. First, the power distribution resulting from the election of the assembly significantly affects the incentives of the majority and minority to cooperate. It has been argued that, as the minority in both cases did not have enough votes to counterbalance the majority, the majority had no incentive to negotiate (Larraín et al. Reference Larraín, Negretto and Voigt2023). Second, it seems that the openness of deliberations encouraged representatives to respond more to their territorial audiences than to seek agreements within the convention (Larraín et al. Reference Larraín, Negretto and Voigt2023). Moreover, some authors have suggested that the vertical linkages between the convention’s deliberations and citizen participation were ineffective. Thus, representatives responded to the demands of the most mobilized groups without being able to organize concrete mechanisms to ensure massive citizen participation that would have an impact during the deliberation process (Díaz Reference Díaz and Fuentes2023; Heiss and Suárez Reference Heiss and Suárez-Cao2024; Welp Reference Welp2024). Finally, the contingency of holding a presidential election in the middle of the process of drafting a constitutional text disrupted the structure of coalitions within the convention, hindering the possibility of reaching broader agreements (Fuentes Reference Fuentes and Fuentes2023).

Socio-electoral contingencies

The third dimension refers to the social and electoral contingency, which had significant effects on the rejection of the text proposed by the convention. The high level of mediatization of the convention’s deliberations, with controversies aired publicly, generated an adverse effect on public opinion, leading to increased distancing and negative evaluations of the process (Sajuria and Saffirio Reference Sajuria, Saffirio and Fuentes2023; Alemán and Navia Reference Alemán and Navia2023; Piscopo and Siavelis Reference Piscopo and Siavelis2023). Second, the average electorate held a more moderate position than the proposal presented, which alienated many voters (Alemán and Navia Reference Alemán and Navia2023). Along the same lines, it has been suggested that voting patterns depend on certain social contexts, with voters acting on the basis of their evaluation of the proposal and its perceived effects (Keefer and Negretto Reference Keefer and Negretto2024).

Another argument indicates that the approval or rejection of the proposal correlates closely with presidential approval. Amid declining approval ratings for President Gabriel Boric, the population was inclined to reject the text proposed by the convention (Alemán and Navia Reference Alemán and Navia2023). Additionally, the plebiscite itself became an indicator of support or opposition to the government (Piscopo and Siavelis Reference Piscopo and Siavelis2023). Finally, some authors highlight the impact of disinformation and fake news during the electoral campaign, which likely influenced the result (Piscopo and Siavelis Reference Piscopo and Siavelis2023; Durán and Lawrence Reference Durán, Lawrence and Fuentes2023; Saldaña et al. Reference Saldaña, Luna, España and Peña2024).

Thus, both comparative literature and literature that has analyzed the case of Chile distinguish between factors specific to the design of rules and institutions and those related to the capacity and interest of political actors in promoting consensus (balance of power, polarization, fragmentation). However, a third group of factors associated with electoral dynamics and social perceptions regarding the proposed text is also mentioned in the literature (Sajuria and Saffirio Reference Sajuria, Saffirio and Fuentes2023, Alemán and Navia Reference Alemán and Navia2023).

The constituent process in Chile

The Chilean constituent process comprised three moments and four instances of drafting proposals for the new constitution. The first moment occurred between 2014 and 2018, when the leftist President Michelle Bachelet promoted a constituent process that included nonbinding citizen consultations, the establishment of the Council of Observers, and a final stage in which the government sent a proposal for a total reform to the National Congress. However, Congress did not discuss this proposal. In this case, the main right-wing parties refused to participate in the process. Upon winning the 2018 presidential elections, the new president, Sebastián Piñera, dismissed the idea of continuing the constitutional debate.

In 2019, an acute social crisis emerged, with demands for improvements in living conditions. In response, political actors promoted a new constituent process, this time calling for an entry plebiscite to ask the population if they wanted a new constitution. The plebiscite took place in October 2020, and the idea was accepted. A convention was subsequently convened to draft a proposed text. Finally, a plebiscite was held in September 2022, and citizens rejected the text by 62 percent of the vote (Fuentes and Díaz Reference Fuentes and Díaz2023).

Immediately, political parties called for a new process, but this time under a different set of rules: a Constitutional Council election was held with mandatory voting, lists of independents were prohibited, and the Committee of Experts appointed by Congress was tasked with drafting a proposal that the council would use as the basis for its deliberations. Finally, the council was elected by popular vote to deliberate and propose a text. For the second time, however, the proposal was rejected by the citizenry, this time by 55.7 percent in December 2023.

As we consider the set of conditions identified by the literature and apply them to both processes, we observe some contradictory results. For example, it has been argued that, in the first process, the assembly election rule was crucial because it allowed independents, enabling high fragmentation. However, in the second process, the participation of independents was eliminated, and political fragmentation in the council was considerably reduced. Nevertheless, the rejection vote was repeated.

Regarding the political contingency variables, while the first convention featured extremely open deliberations, in the second process, the council’s deliberations were more restricted, carefully managed, and less disseminated, suggesting that this factor does not consistently explain the rejection in both cases. Moreover, while the first process exhibited a more intense—though not well organized—participatory dynamic, the second process involved minimal citizen participation. Neither the degree of process openness or closure nor presidential disapproval fully explains the double failure (Table 1).

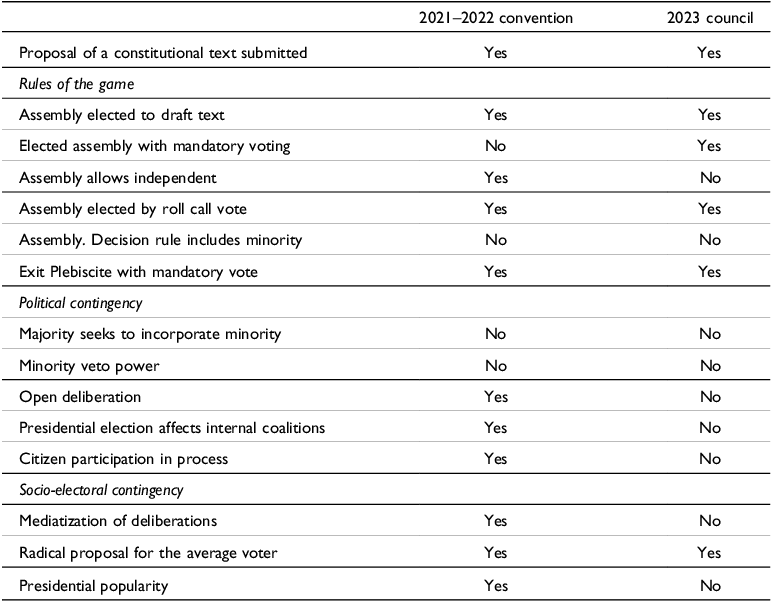

Table 1. Conditions present or absent at different stages of the constituent process

However, some conditions were constant in both processes. First, the decision rule for approving the constitutional text required a two-thirds majority in the convention and a three-fifths majority in the council. What is relevant here is that in neither case was a system devised to force the majority to negotiate with the minority (e.g., by establishing a unanimity rule). Since the electoral result allowed the left to dominate the convention with 71.5 percent of the seats in the first process and the right to dominate the council with 66.5 percent in the second process, there was no obligation to negotiate with the opposition.

Another element common to both processes was the plebiscite, which was conducted with mandatory voting and required a simple majority (50 percent + 1 vote) for approval or rejection. If, for example, a higher quorum for ratification had been established, the actors in the assemblies would probably have sought broader agreements. From the perspective of political contingency, the balance of power in the respective assemblies made the left dominant in the first process and the right dominant in the second. What is important to note here is that, in both processes, the political majority was explicitly uninterested in incorporating the minority into the agreements.

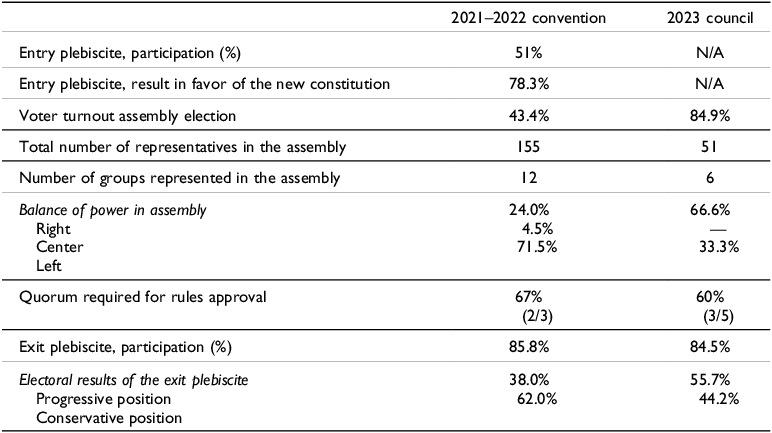

Finally, in terms of socio-electoral contingencies, the average voter perceived both proposals as extreme (Table 2). Examining electoral results, we observe that both the 2020 entry plebiscite and the convention election were conducted with low levels of electoral participation. In contrast, the council election and the exit plebiscites saw participation rates close to or above 85 percent of the eligible voting population. One could argue that the rejection of the first process influenced the second, establishing a general tendency to reject any formula proposed by the elites.

Table 2. Electoral results in the election of the convention and Constitutional Council

Source: Electoral Service www.servel.cl.

However, as we will show, during the second process, most citizens consistently maintained a favorable opinion toward changing the Constitution. What was rejected in both the first and second processes was the exclusive and unprofessional behavior of the elected representatives tasked with proposing the new Constitution.

In what follows, we refine the causal mechanisms relevant to explaining this double rejection. We concur with the literature that certain rules, combined with elements of political contingency, made it impossible to produce texts that were appealing to citizens. Specifically, in both cases, the rule designed to promote agreement between majorities and minorities (the two-thirds rule in the first process, and the three-fifths rule in the second process) proved ineffective. This was because, in both instances, the conventions were controlled by majorities that did not depend on minority votes.

The argument we develop below is inspired by Putnam’s (Reference Putnam1988) work on the logic of two-level games. Although Putnam applies this framework to analyze decision-making dynamics at the international and domestic levels, some of its premises are relevant to the case we are analyzing. First, each level or bargaining space operates in relative isolation, although at key moments, the domestic arena may significantly influence the actions of negotiators at the international level. Second, if the scope of win sets is broad among the parties negotiating at the international level, the likelihood of their approval at the domestic level increases. Third, the likelihood of achieving such broad agreements depends on the distribution of power and the preferences of the actors at the negotiating table.

We then analyze the constituent dynamics as a double game, comprising a level of intraelite negotiation within the assemblies (Level I) and a second electoral game in which political actors must seek ratification by the citizenry (Level II). Following Putnam’s premises, we must emphasize that these two arenas operate sequentially and are relatively isolated from each other, although we suggest some connections between the two spheres. In both processes, there was a “bubble effect,” with representatives in the assembly acting without significant linkages to public opinion, and the public remained highly sensitive to the behavior of both conventions. Second, in both constituent processes, the win sets in the respective assemblies were very narrow, substantially reducing the probability of their acceptance by the citizenry.

The article is qualitative, drawing on primary and secondary sources. Concerning intraelite dynamics, we analyze published articles, press reports, voting records, and transcripts from twenty-nine interviews with key actors, including advisers and convention representatives. Regarding electoral dynamics, we analyze electoral results, campaign ads, public interviews with campaign strategists, public opinion surveys, and focus groups conducted during the first and second processes.Footnote 1

Results

We present the results by comparing the first and second constitutional processes at each level, to analyze the causal mechanisms that explain the failure of both processes.

Level I: The intraelite game

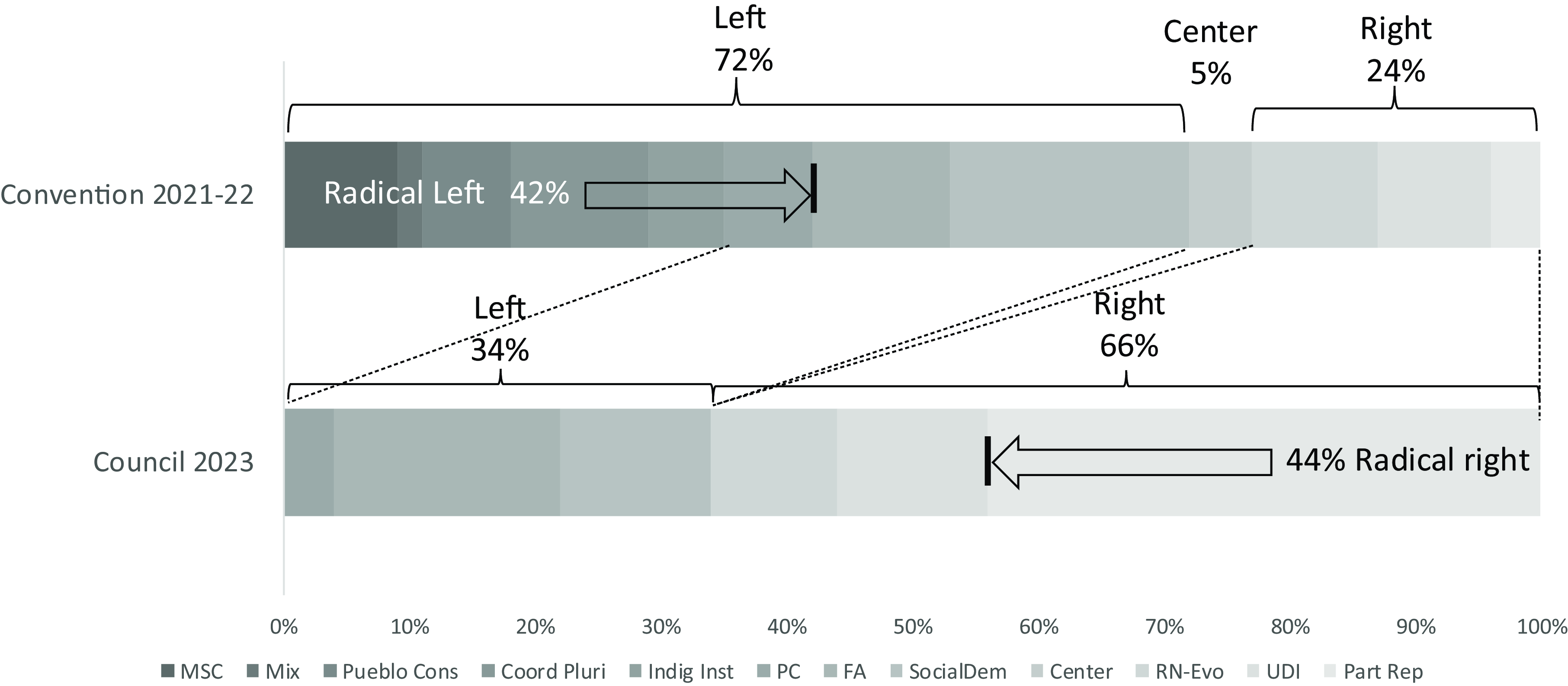

The literature highlights the importance of power distribution in deliberative bodies (Boesten Reference Boesten2017). In the first process, twelve collectives were organized, compared to six in the second. The first process required a two-thirds majority (66 percent), forcing radical left groups (42 percent of votes) to negotiate with moderate socialist sectors. This high level of fragmentation led to a dynamic of negotiations around different “causes” or issues that the groups sought to incorporate into the text, as we will analyze below.

In the 2023 Constitutional Council, the radical right-wing Republican Party held the largest number of votes within the council (44 percent), needing only 16 percent more to reach the 60 percent required to approve norms. Centrist parties were absent, and the left, though more coordinated, lacked the weight to influence decisions. The result was a text that reflected the ideas of the most conservative sector of the right (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of power in the 2021–2022 convention and the 2023 council.

Source: Electoral results and Fuentes (Reference Fuentes and Fuentes2023).

Hence, what the literature suggests for the first process can be extended to the second: The combination of a power distribution highly favorable to certain political holdings, together with the decision rule to approve norms, explains the production of a left-wing text in the first process and a right-wing text in the second. The question that arises is why the actors, despite knowing that the text had to be ratified by the citizens in a plebiscite, were not attentive to social perceptions.

One might argue that the negative outcome for a new constitution was the result of a consistent stance in public opinion rejecting the idea of constitutional change. However, various surveys conducted between 2013 and 2019 showed steady support (over 60 percent) for a new constitution (UDP 2013; PNUD 2015; COES 2018; COES 2019). Furthermore, a series of polls conducted in 2023 show that support for a new constitution ranged from 58 percent (August) to 64 percent (November) (UDP-Feedback 2023).

In both processes, public opinion criticized the lack of consensus and representatives’ conduct, not constitutional change itself. The key question then arises: Why did the actors in the second process, despite being aware of the first failure, fail to produce a text with a greater chance of being accepted by the population? We suggest two causal mechanisms that simultaneously explain why, in both processes, the representatives in these assemblies did not seek a transversal agreement: the “social majority bias” and the “bubble effect.”

The social majority bias

In both moments, representatives behaved as if they represented society as a whole. This bias was evident in their actions, as they acted “as if” they represented all of society when, in reality, they represented the demands of only particular groups. This majority bias meant that representatives did not feel the need to seek agreements with minority groups. Moreover, reaching agreements would imply betraying “the will of the people.” From the outset, this bias distorted the possibility of establishing agreements with minority groups.

In the first process, leftist groups insisted that they represented the 78 percent who supported a new constitution and the 70 percent who voted for a left-leaning convention. In the second process, the same discourse was repeated, but this time by the right wing, which saw no need to establish transversal agreements. As Daniel Stingo, a representative of the left-wing Frente Amplio, stated: “We, those of us who are not of the right, are going to set the big agreements, so let me be clear, and let us not start going around in circles. Here the right did not win … and now it is in minority.” And he continued, “those of us who won represent the people, then talk of course … you cannot impose anything on the rest of Chileans, because you lost” (TVN, 2023).

Once installed in the convention, the constituents themselves exhibited no willingness to collaborate with the right wing, because they did not need them, they perceived intolerance or class bias in the right-wing groups, or they feared being associated with them. This is how a representative explained the situation: “But we did not need it, that is, to have 103 votes you did not need the right wing. So no … for me going to talk to them was a waste of time” (Interview representative 4, 2022). Another representative argued: “As we were all intoxicated by the result [of the elections], I could not vote in favor of a right-wing proposal because everyone would immediately criticize me. They forced me to reject. Personally, I was talking to a right-wing person, and I even liked some proposals very much, but I could not vote in favor of them” (Interview representative 23, 2022).

For other convention members it was impossible to reach agreements because there was no predisposition on the right to establish agreements: “In the right wing there is a very entrenched group, which is directly trying to make the process fail…. It is impossible to have any kind of dialogue with them. They don’t talk to anyone, they don’t say hello” (Interview representative 9, 2022). A constituent adviser reinforced this perception: “There is a super important sector (of the right wing) that is in favor of boycotting it and seeking to broaden the rejection in the exit plebiscite” (Interview adviser 15, 2022).

The same dilemma arose in the second attempt to establish a new constitution. This time, it was the more extreme right that defended its right to make the tyranny of the majority prevail. Councilor Luis Silva (Republican Party) indicated that for the more moderate parties of the right, dialogue meant reaching agreements, but “not for me. In democracy the rule of the majority is to resolve disagreement. If one of the parties says, ‘This has to happen because these are my convictions,’ if I don’t agree, I say, ‘Let’s vote.’ And that’s democracy.” The voice of the majority then implies that it is not necessary to establish agreements with the minority voices: “Why the hell being the majority we have to reach agreements with the minority…. I don’t want to go over them, but here the openness to agreement is of those who are in the minority” (El Mostrador 2023).

These statements generated public controversy because they mirrored what had happened in the first convention. A few days later, Silva himself stated that “although you had the majorities you have to take care not to irritate the minorities, because your decision may be the one that ends up adapting … but the minorities have a responsibility which is to respect the decisions taken by the majority” (Emol 2023).

According to the president of the Constitutional Council, Beatriz Hevia (Republican Party), the majority party in the council tried to seek agreements, but in that attempt, the leftist sectors refused to open up: “We [Republicans] try to build bridges, but doing so means that both sectors or all sectors approach a common point. It is not that one sector expects that some of us must move to the other side of the bridge…. That was the situation in which we found ourselves many times” (The Clinic 2023).

The voting records of the first and second processes show the absence of agreements among the representatives in these decision-making spaces. Mascareño et al. (Reference Mascareño, Valdivieso, Parker and Torres2022) analyzed the voting universe of the first convention (4,511 votes), showing highly cohesive behavior among the more left-wing groups and a division on the right between a more conservative group that rejected much of the text and a more liberal right-wing segment that accepted some aspects of it. Analyzing the voting record (article by article) of the first draft of the constitution, Fuentes (Reference Fuentes and Fuentes2023) shows that while the leftist sectors voted favorably on 80 percent of the articles, the liberal right did so on 45 percent and the conservative right on only 25 percent of them.

The voting record in the second process reveals the opposite dynamic. The more liberal and conservative right exhibited an even higher level of cohesion than in the first process, while the left—now with low representation—also showed more cohesion but voted against the proposal (Lang Reference Lang2024).

The bubble effect

A second mechanism that contributed to clouding the vision of the decision-makers is the bubble effect: the internal dynamics of deliberations in which both resolution bodies became trapped, focusing on debating individual issues rather than considering the overall coherence of the emerging text. We argue that bureaucratic dynamics—intensive, partial debates on numerous issues within a very short time—reduced the likelihood that representatives would connect with the concerns of citizens.

The first process was organized into two stages. In the first stage, eleven commissions were established, which, during the first three months, addressed aspects related to the organic regulations of the convention, citizen participation, budget, indigenous consultation, among others. In the second stage, ten commissions were organized to work on thematic proposals for the new constitution between October 2021 and March 2022. Then, between March and July, the voting process took place in the plenary for each of the reports from the respective commissions, followed by a final harmonization process. If no text had been presented by July 4, 2022, the convention would be dissolved, and the current Constitution would remain in effect.

This design caused a high degree of compartmentalization and a heavy workload, given the presentation of amendments and voting in committee and on the floor. From October 2021, and for almost nine months, the main function of the representatives was to negotiate amendments one by one, which resulted in a significant waste of time. The workload was so intense that in January, it was decided to eliminate the district weeks, during which representatives would engage with their electorate. In the final stage of the process, over one thousand votes were cast for each of the articles to be incorporated into the new text (Fuentes Reference Fuentes and Fuentes2023).

This is how an adviser who participated in the first convention explains it: “The day started very early in the morning, sometimes we had a meeting at 7:30 a.m. to discuss different issues that would be discussed during the day or the week. After that we would arrive at the session at 9:30 a.m…. we would leave for the meeting at 1:00 p.m. or 1:30 p.m…. We rarely had a meeting for an hour, very rarely. We were usually at the convention until [6 or 7 p.m.]. After that we had meetings among the team until, for example, 11 p.m. when we finished working.” This adviser underlined the lack of time: “We had so little time to talk. It was impossible to talk before the votes, and we had to vote yes or no. Some did not even know how they had to vote. Some did not even know how they had to vote” (Interview adviser 4, 2022).

The compartmentalization of the work caused the actors to start negotiating on an issue-by-issue basis, creating a dynamic of compromise between the different causes represented in the Convention. One representative points out: “There was a moment when they [indigenous women] told us that they were not going to vote for abortion unless we voted, for example, for indigenous property … it was a moment when I was really upset” (Interview representative 5, 2022).

The experience of rejection in the first attempt led political actors to modify the work dynamics for the second process. Congress established an expert commission of twenty-four members (twelve from the center-left and twelve from the right) to present a draft constitutional text to the elected council. The text was delivered in early June and reflected significant and broad agreement. The Constitutional Council was tasked with working on the draft for four months, after which it would pass the text to the expert commission for comments. The council was then to approve the final text in plenary on November 6. It was assumed that what was approved by the expert commission would undergo minimal modifications, requiring less debate and discussion in the council.

The council replicated the logic of the previous process by creating thematic committees (four in total), which submitted their respective reports to the plenary for voting. Although there were fewer commissions, representatives submitted a total of 1,092 amendments, which were subjected to 897 votes by the plenary (CEP 2023).

A critical moment for the Constitutional Council came in mid-July, when representatives introduced amendments to the text. Against all odds, the Republican Party, representing the most conservative sector, alone submitted over four hundred amendments, marking a departure from the agreement reached by the crosscutting expert group convened by Congress. Crucial issues such as women’s right to choose abortion, gender parity, property rights, the role of international treaties, the right to strike, indigenous peoples, and water rights were among the most significant (ExAnte 2023a).

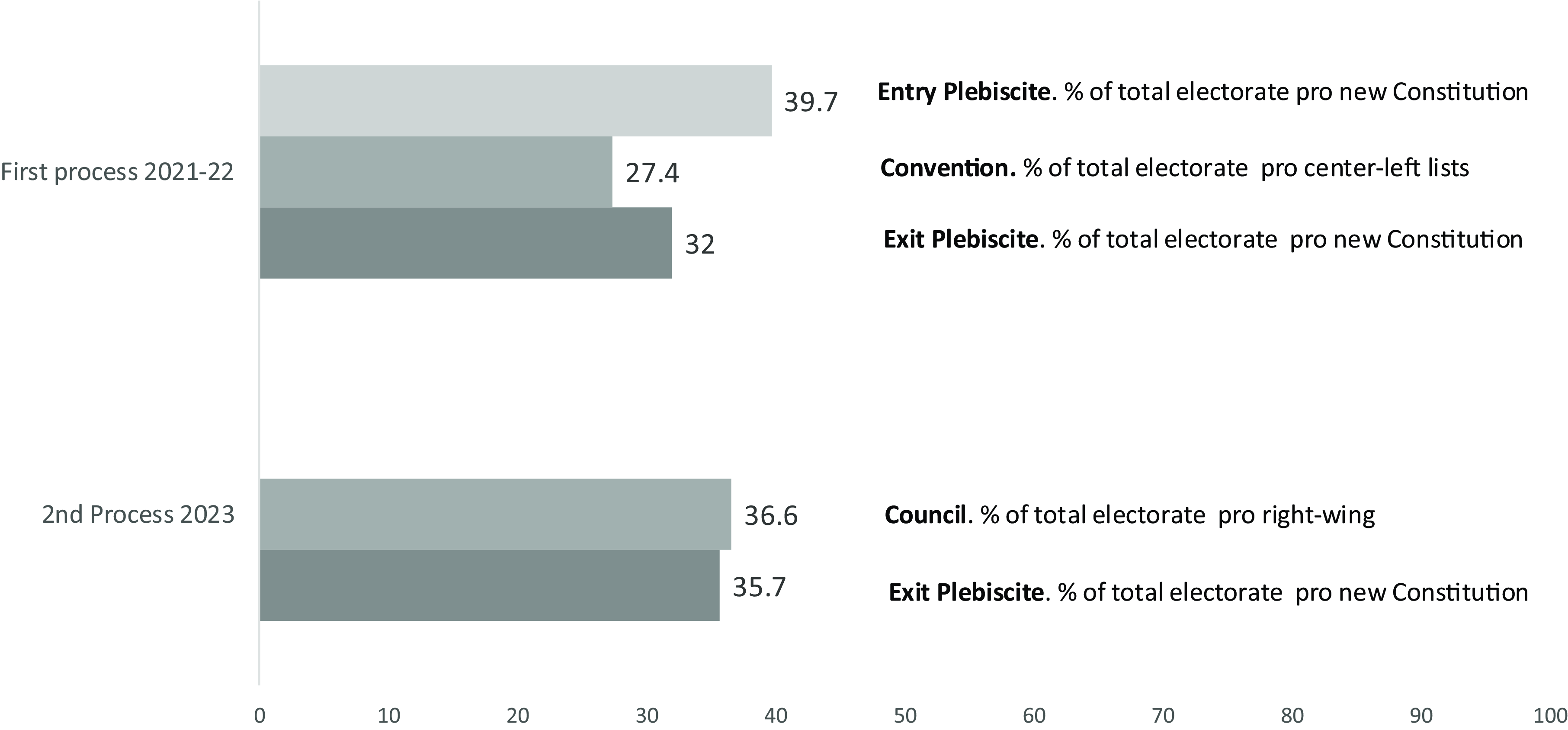

The social majority bias and the bubble effect reinforced each other, preventing representatives from visualizing the segment of the population they were representing. It is important to note that the 2020 entrance plebiscite and the election of the first convention were conducted with voluntary voting, creating a significant distortion relative to the total number of voters. Figure 2 illustrates all the results in relation to the total voter population.

Thus, in the 2020 plebiscite, only 39.7 percent voted for a new constitution, 27.4 percent voted for convention members identified with the center-left who reached the convention, and 32 percent voted for the new constitution proposed by that sector. This indicates that the representatives of the first convention, although they acted as if they represented a social majority, ultimately represented the interests of the segment that voted for them.

In the second process, something similar happened. The councilors elected by the right wing represented 37 percent of the electorate, and in the exit plebiscite, 35.7 percent voted for the option of a new constitution that they favored. This demonstrates that the logic of the first process was replicated, where the actors who held the majority in the council ultimately represented the interests of the segment that elected them. In both cases, the majority represented in the respective assemblies failed to reflect the broader social majorities.

The political representatives in both constitutional processes embodied the social majority bias and the bubble effect, but these characteristics are not exclusive to these assemblies. Luna and Rosenblatt (Reference Luna, Rosenblatt, Diíaz and Sierra2012) show that the party system in Chile is weakened and disconnected from civil society. According to these authors, this weakening stems from a social uprooting of parties: They lack solid ties to their territorial bases and effective mechanisms to channel citizen demands. That same disconnect manifested among the convention members: Believing themselves to be “spokespeople” for an imaginary social majority and immersed in day-to-day business, their negotiations reproduced self-referential dynamics and the promotion of particular interests rather than fostering broad consensus. In both processes, this weak connection to the citizenry amplified the social majority bias and the bubble effect, contributing to the distance between convention members and the electorate.

Level II: The electoral game

From the beginning of each process, representatives understood that majority citizen support was crucial. This section examines the strategies employed by campaigns based on quantitative and qualitative data. We argue that a key factor explaining the outcome is the way these campaigns were conducted. This mechanism, which has not been documented in previous analyses, is presented as an important complement to understanding the double rejection of the constitutional proposals.

Two dimensions are relevant to highlight. The first refers to the way public opinion evolved as each process developed. In this regard, we observe that citizens’ opinions were not immutable and, in fact, were influenced by the polarized deliberations that occurred in both cases. The second dimension concerns the strategy developed by the campaigns themselves. Here, the dilemma was whether to focus on defending or criticizing the text or to emphasize political issues outside the constitutional text (e.g., criticizing the government in power). Overall, successful campaigns were those that focused on criticizing the text itself.

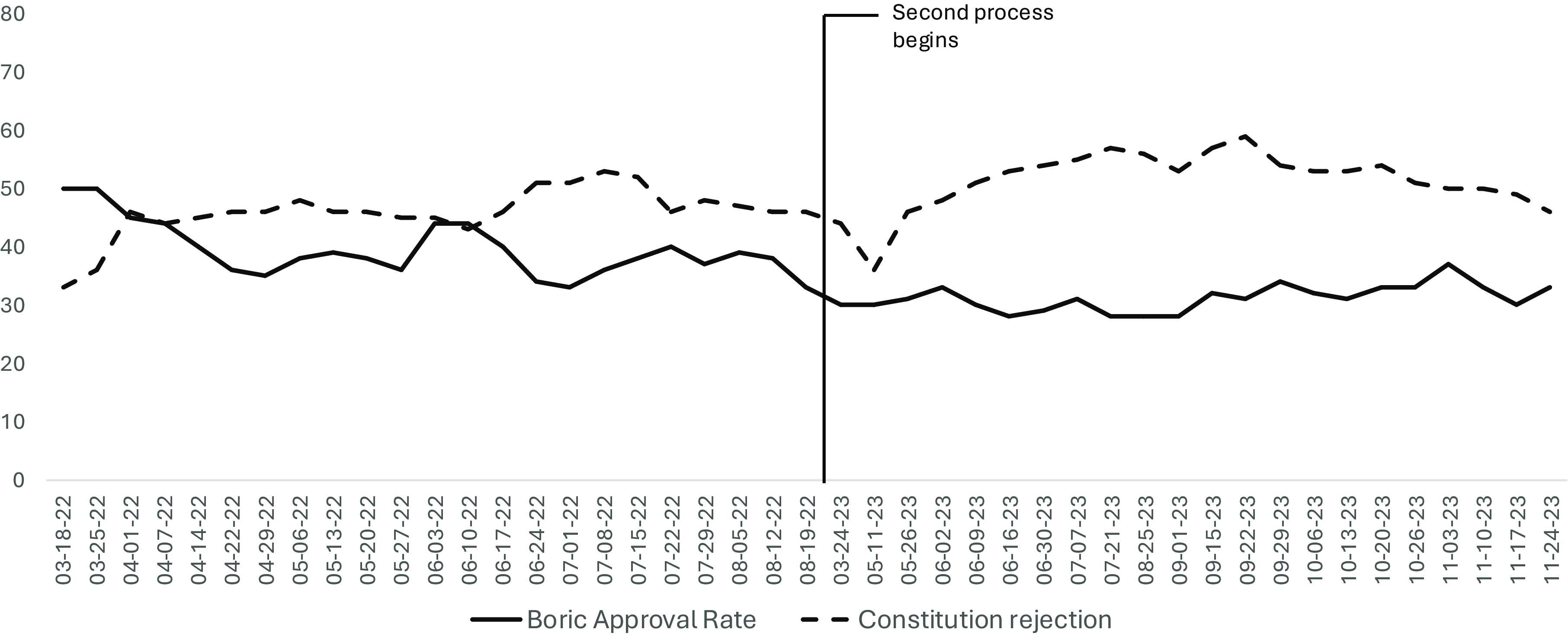

With respect to presidential approval, we note that this is not a sufficient explanation. In the first process, the drop in presidential approval—which declined between July and September 2022—correlated with the triumph of the rejection. This could lead us to think that voters rejected the text by associating it more with the government than with its content (Alemán and Navia Reference Alemán and Navia2023; Piscopo and Siavelis Reference Piscopo and Siavelis2023). However, if this condition were true, we would expect the population to have voted massively for approval in the second process, since the president and his left-wing coalition supported rejection—yet this did not happen. Figure 3 illustrates that while the rejection of the text experienced a sustained rise, reaching close to 60 percent in September 2023, presidential approval remained relatively constant at an average of 30 percent. This leads us to explore the prevailing climate of opinion, which in both cases leaned toward rejecting the text during the six months prior to the vote (Figure 4).Footnote 2

Figure 3. Rejection of the constitutional text vs. presidential approval.

Source: CADEM 2022–2023 survey.

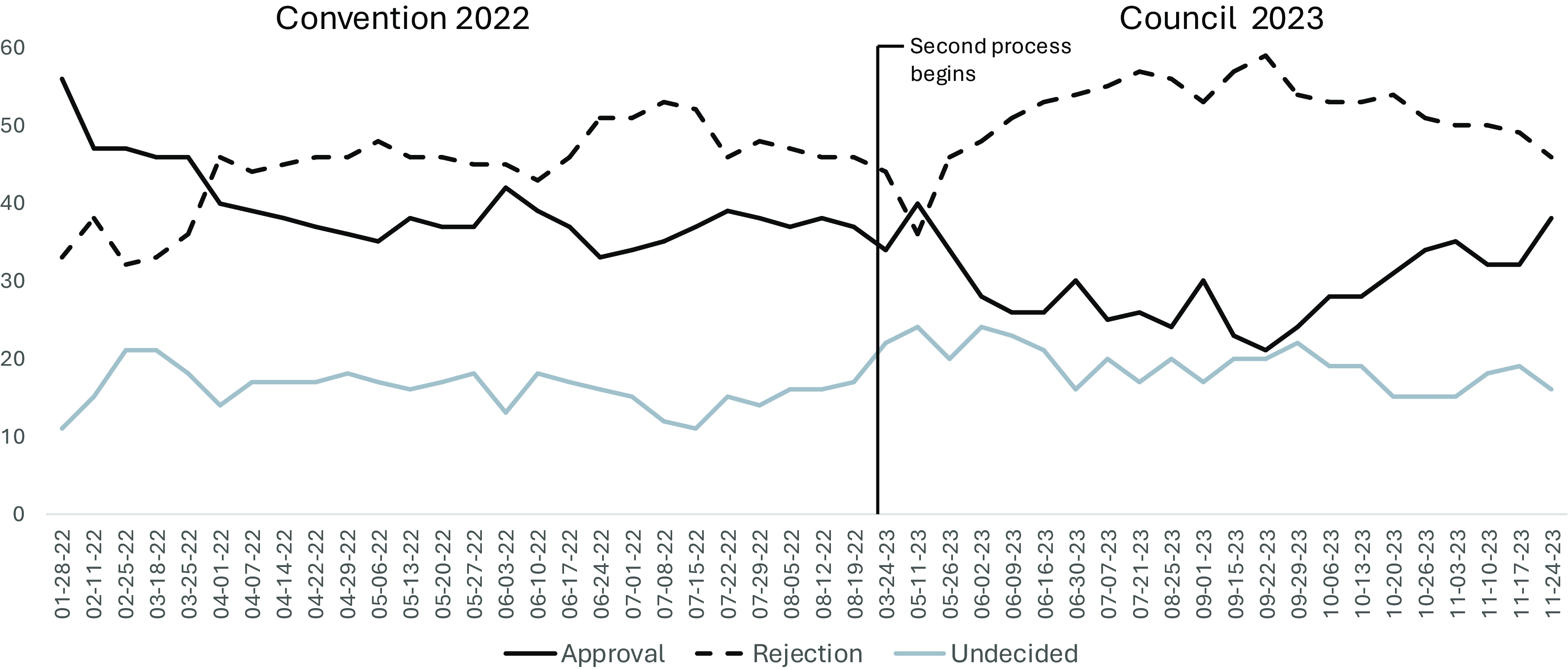

Figure 4. Public opinion on approval/rejection of the constitutional text.

Source: CADEM 2022–2023 surveys.

In the first case, as of April 2022, the citizenry leaned towards the rejection option. This shift occurred precisely between March and April, when the plenary of the convention began to generate intense public debate on specific issues such as the ownership of pension funds and the recognition of indigenous peoples, among others.

In the second case, there was a favorable inclination between March and May 2023, when the expert commission elaborated and proposed a consensus text. However, immediately after the Constitutional Council took office, public opinion steadily shifted toward rejection. In both instances, the months prior to ratification show a narrowing trend in the rejection-approval options, attributable to the development of the electoral campaigns leading up to the respective plebiscites.

Qualitative studies by Subjetiva reveal the dominant climate of opinion in both processes, tracking social narratives around key milestones. Initial meetings reflected optimism about resolving the tensions of October 2019 and expectations for the convention as an alternative to the delegitimized political system. However, once the convention was installed, negative perceptions began to dominate conversations about its work. The opening ceremony alone was enough for people to feel that the convention was highly polarized, with little room for dialogue. Many citizens felt betrayed, perceiving that the problems of traditional political spaces were being repeated. These bad practices led to widespread disillusionment.

One participant captures this sentiment: “My personal perception is that there was going to be order, that there was going to be loyalty, that there was going to be a word. My personal perception is that there [was] going to be order, that there [was] going to be loyalty, that there [was] going to be a word, that there [was] going to be a word. Mine is because of the hopelessness, of thinking that something was going to happen soon and that the people we would elect would be totally different from what was already there, and it is like the same thing, we are going back to the same thing” (in España y Fuentes Reference Fuentes and Fuentes2023, 125).

A series of scandals, such as the false information provided by a representative about his health condition and controversies surrounding the work of the convention, deepened citizens’ disillusionment, which ultimately turned into weariness. The initial expectations reported at the beginning gave way to frustration. In the perception of the people, the convention, far from generating agreements, ended up dividing the citizenry on important issues such as social rights, the political system, and the recognition of indigenous peoples.

For the second process, the same consultant, Subjetiva, conducted five focus groups in October 2023 to understand people’s perceptions of the work of the Constitutional Council. Once again, the negative perception of the council’s functioning was reiterated. People expressed concerns about the politicization of the process, which they perceived as a negative aspect undermining its representativeness and effectiveness. Citizens voiced frustration at the overideologization of the constituent space, where councilors prioritized their partisan agendas over the needs and concerns of the people.

This sentiment is reflected in the words of one focus group participant: “The political issue has a lot of influence, since the parties do not agree, and suddenly a good idea comes along and because it did not suit the right wing the left wing does not support it, and suddenly vice versa … many times they do not agree … many times they do not put themselves in the place of the citizens, but rather in what they believe and want to win as a party” (Subjetiva 2023).

Participants note worrying similarities with the previous process, where political dynamics prevail, and this perception is transmitted to the citizenry. As one voter points out, “The new Constitution is based only on political ideologies about their sector, they never gave their arm to twist and what the idea was that we as Chileans would unite and in the end we are more disunited” (Subjetiva 2023).

The generalized perception of distrust toward the constitutional process was exacerbated by emotional exhaustion accumulated from recent social upheavals and political challenges faced by the country. This fatigue has manifested in growing apathy and a sense of detachment from the political process. As we suggested in the introduction, this was a game characterized by greater isolation at the intraelite level (Level I) and heightened sensitivity at the citizen-electoral level (Level II). While the elites remained unreceptive to public opinion, citizens were highly sensitive to the behavior and debates of the representatives.

Campaign strategies: Text vs. context

Campaign strategies faced several challenges. First, both cases involved relatively short electoral campaigns—two months in the first case and a month and a half in the second. Second, in both cases, those advocating for approval of the text faced the challenge of overcoming a public opinion resistant to approving the proposed document. Third, they had to synthesize highly complex ideas into very brief and limited messages, despite the extensive nature of the texts (388 articles in the first case and 216 articles in the second). Finally, strategists had to decide whether to focus their campaigns on the virtues of the text or on issues related to the country’s social or political context.

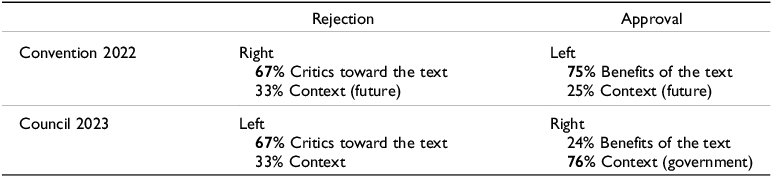

A good proxy for the campaigns’ emphases can be found in the messages delivered through the open television electoral slots. In Chile, each option had fifteen minutes of screen time to broadcast messages aligned with its positions. For this purpose, we systematized the content of the electoral slots from the 2022 and 2023 exit plebiscites. We focused on the last fifteen days of each process, as this period is usually reserved for delivering the most critical messages before the plebiscite. In total, we analyzed 23,374 seconds, categorizing the content thematically. We then calculated the percentage of each topic relative to the total effective time used per campaign. Table 3 summarizes the emphasis of each campaign across the two processes.

Table 3. Percentage of time of electoral campaigns in electoral slots

Source: Electoral slots available in CNTV 2023.

In the first process, both campaigns focused their attention on the problems or benefits of the text. For the campaign opposing the new constitution, 67 percent of time was used to highlight critical aspects of the text. Negative aspects emphasized included claims that the proposal would divide the country. Issues such as security, indigenous rights, health, pensions, children’s rights, and education were also mentioned. Regarding the context, much of this campaign’s time was devoted to affirming that, with the triumph of the rejection, it would be possible to start a new process. Emotions such as love and hope were prominently featured.

The strategists of the Rejection campaign explained that their strategy was based on two pillars: creating a citizen-focused campaign as far removed from traditional parties as possible and emphasizing the problems with the content of the text. According to Gonzalo Müller, one of the strategists: “The winning axis for the rejection is that it allows people who think differently on many things, but agree on only one: The draft proposed by the Convention is a bad text for Chile” (ExAnte 2022). Thus, the campaign was organized focusing on the problems with the procedure by which the text was approved (disparagingly referred to as “a circus”) and the negative impact the new constitution would have on people’s lives. The strategist Bernardo Fontaine stated: “We have arrived at a text that divides us, that disunites us, that is only made by a radical left sector for that radical left sector and that left out the popular initiatives of the citizenship, left out the center-left, left out the center-right” (Radio Universidad de Chile 2022).

An incident that occurred in Valparaíso at the closing of the Approval campaign contributed to reinforcing this idea. On that occasion, a group not affiliated with the official command staged a performance in which the Chilean flag was used with sexual content. This situation generated controversy over the use of patriotic symbols and reinforced the message of a text that divided the country and questioned the essential values of the nation-state.

In the case of the Approval campaign, 75 percent of the total time in the time slot was also related to aspects of the text itself. The remaining 25 percent was used to address the context in which the vote was framed. Within the portion addressing the text, multiple articles were highlighted that aimed to improve the lives of certain population groups and address historically marginalized issues, including indigenous peoples, the environment, control of abuses by large companies, and health.

Felipe Hausser, one of the leaders of the Approval campaign, argued that “I am convinced that the Apruebo will win on September 4 because it is an option that offers certainty, a concrete way out of the crisis that Chile has experienced, and also offers a future” (La Tercera 2022a).

Unlike the Rejection campaign, which sought to make the parties invisible, the Approval (Apruebo) campaign pursued the opposite approach: highlighting the identity of those supporting the proposal. As a result, two deputies led the command. When evaluating the work of the approval campaign, Cariola stated that she valued the unity of the campaign, adding that “a value of this campaign is that we have never stopped showing what we are or who we are, as political actors, Vlado and I, he from democratic socialism, I from Dignity Approval … we have not wanted to hide our characterization” (La Tercera 2022b).

The second process revealed partially different strategies. This time, the roles were reversed: left-wing sectors promoted the rejection of the text, while the right-wing advocated for its approval. For the rejection campaign, the left focused on the negative attributes of the proposal. Specifically, 67 percent of the time was devoted to issues related to the text, while 33 percent addressed the context surrounding the vote. The main emphasis was on the threats the proposal posed to acquired rights. For instance, it was argued that the proposed tax exemption would undermine the ability to obtain resources for financing public safety policies. Additionally, concerns were raised about how the proposal threatened women’s rights in sexual and reproductive health, could exacerbate corruption issues, and would generate division among Chileans.

Antonia Rivas, one of the leaders of the command, stated: “We want to explain to the citizens that this is a bad text, because this proposal was built only by some and for some. It is a proposal that is not representative, there are no right or wrong Chileans” (La Tercera 2023).

The right wing, on the other hand, adopted a different strategy from what it had previously employed, focusing instead on criticizing the government. In this slot, only 24 percent of the total time was devoted to constitutional issues, while 76 percent focused on the political and social context of the country. A significant portion of the time slot was used for spots directly criticizing the government, blaming it for the social outbreak and the problems it caused for the country.

From the point of view of the strategists of the campaign for the vote in favor, they sought to link the vote with a punishment of the government itself—a strategy that ultimately did not work. Müller stated during this second campaign: “It seems that President Boric has decided to lead the campaign for the vote Against … When he gets involved as he does, people begin to perceive that voting in favor implies punishing the President” (ExAnte 2023b).

The other line of argument focused on closing the constituent process, emphasizing that the 2023 exit plebiscite would be won by whoever could best conclude the cycle initiated four years earlier with the social outburst. Bernardo Fontaine, another coordinator of the command, stated: “To begin to end four years of violence, delinquency and economic and social decadence … it is the way to end this eternal constitutional discussion that has exhausted us all” (Radio Universidad de Chile 2023).

Just before the end of the campaign, the approval option launched a controversial spot titled “Que se jodan,” which argued that those who had burned the country demanding a new constitution were now calling to vote against it. The spot ends with a woman declaring: “I am going to vote in favor, and fuck them” (Biobio 2023).

Thus, we observed a citizenry that, while initially more hopeful during the first process, quickly became critical because of the way the process was conducted and the nature of the proposals. In both the first and second plebiscites, the strategies of the winning campaigns focused on criticizing the quality of the text and emphasizing that the proposals divided the country and harmed the interests of the great majorities.

Discussion

In this article, we propose a comprehensive explanation for the double failed attempt to establish a new Constitution in Chile. We offer a two-level game analysis, suggesting specific causal mechanisms to explain this unusual outcome.

At Level I, the majority actors in both cases decided not to reach agreements with the minority, despite knowing that the result depended on the electorate. Two causal mechanisms were documented in both processes: first, the incumbents’ conviction that they represented a social majority (social majority bias), and second, a bubble effect, which trapped assembly members in endless thematic or cause-based negotiations, leaving them without the capacity or time to observe the social effects produced by their decisions.

Once the proposals were presented to the citizens, a second moment began. Here again, we observed common patterns: a majority climate of opinion against the texts, reinforced by the citizens’ perception of a lack of political agreements. Moreover, successful electoral strategies emphasized the weaknesses of the text. As citizens perceived threats to their rights, the rejection of constitutional change prevailed. We argue that these two levels do not operate completely in isolation from each other. Indeed, in both processes, what happens at Level I affected public opinion at Level II, showing a unidirectional influence. However, these changes in public opinion failed to influence the behavior of legislators.

Chile’s double constitutional failure must be understood within a broader political context. At the intraelite level, the situation can be analyzed considering the country’s party system. In the case of Chile, a process of deinstitutionalization of the party system and weakening of vertical links between parties and citizens has been documented for at least two decades (Fuentes and Villar Reference Fuentes and Villar2006; Luna Reference Luna, Fontaine, Larroulet, Navarete and Walker2008, Reference Luna2010; Luna and Rosenblatt Reference Luna, Rosenblatt, Diíaz and Sierra2012; Belmar et al. Reference Belmar2023). In addition, a process of high fragmentation has taken place, with the number of parties increasing from ten in the mid-1990s to twenty-one legally constituted parties as of 2025. The inclusion of a high percentage of independents in the first process did not resolve the problems of representing social demands. In that case, these were ad hoc organizations with weak ties to the citizenry. In the second process, the traditional parties controlled the debate and the proposal, without connecting (again) with the concerns of the citizenry.

Thus, both versions of the constitutional process highlighted the serious problem of the crisis of representation of parties and social movements that has been documented in Chile since at least the early 2000s. This crisis of representation is common to other Latin American contexts and has been documented by numerous authors. This crisis of representation is common to other Latin American contexts and has been documented by numerous authors who have studied both party systems (Waddell Reference Waddell2015; Piñeiro and Rosenblatt 2016) and the emergence of new populisms that appeal to direct links between the leader and their followers (Wiesehomeier et al. Reference Wiesehomeier, Ruth-Lovell and Singer2025).

In both Chilean constitutional processes, the milestones that shaped the conventions and the behavior of their representatives—together with a citizenry highly sensitive to the course of events—generated a growing climate of distrust. This distrust was reflected in public opinion polls, which began to show a majority leaning toward rejection months before the conventions concluded their work. This created a highly unfavorable environment for any campaign strategy aimed at reversing that trend. From this perspective, the constitutional process in Chile illustrates the problems faced by contemporary democracies in contexts of crisis of representation. This unprecedented double constitutional rejection demonstrated the inability of both civil society and political parties to effectively connect with most citizens.

Some lessons from the Chilean case are as follows. First, in contexts of crisis of representation of parties and civil society movements, it is essential to organize appropriate mechanisms for citizen participation to ensure social ownership of such processes. Second, the design of the rules should consider mechanisms that favor dialogue and agreements that are as broad as possible. Third, it seems more advisable to define processes with an extended timeline that contribute to the generation of consensus. Finally, mechanisms should be created that contribute to reducing the risks of isolation on the part of those who are writing a constitution. If there is one thing that Chile’s case teaches us, it is that these two constitutional processes reflect political, institutional, and social conditions that are expressed in this double game within the elite and in the electoral arena.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out within the framework of the FONDECYT 1210058 project led by Claudio Fuentes. We would also like to thank the Center for Intercultural and Indigenous Studies (CIIR), where he works as an associate researcher, for its support, as well as the anonymous LARR reviewers for their comments.