Making Cities Beautiful—And Even More So!

It was April 15, 2019, at 6:50 pm, when fire consumed the rooftop of Notre-Dame de Paris causing its spire to collapse in plain view of millions of people. France’s President Emmanuel Macron addressed the nation immediately: he promised to rebuild the Cathedral of Notre-Dame “even more beautiful than it wasFootnote 1.” Many supported Macron’s commitment to reconstruct the cathedral, but aesthetic visions varied. Some insisted on the necessity to follow “revolutionary attitudes of French culture” [Pinto Reference Pinto2019] and to search for “innovative” aesthetics. Others, to the contrary, demanded the spire to be reconstructed “as it was”—or, as chief architects of the Historical Monuments have put it, to “restore the monument to its last complete, coherent and known state” [Friends of Notre-Dame de Paris 2020]—its condition during the 19th century (Figure 1). The renowned French architect, Jean Nouvel, summarised this popular opinion: “I think we have to be more Gothic than ever” [Cigainero Reference Cigainero2019].

Figure 1 “Eternal” Notre-Dame de Paris after the fire. August 2019

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Everyone seemed to care about how the cathedral should and should not be reconstructed. And at first glance, there is nothing unusual about this fact. People care how buildings look for multiple reasons. First, the aesthetics of built environments—their colors, substances, and styles—are packed with meanings, which makes aesthetic choices paramount [De La Fuente Reference De La Fuente2000]. Second, in the “aesthetic economy” [Böhme Reference Böhme2003] of late capitalism, cities are forced to compete for resources, and that is why governments, developers, architects, and city inhabitants are all motivated to make cities as aesthetically appealing as possible [Gassner Reference Gassner2021; Summers Reference Summers2015]. As Monika Degen and Gillian Rose remind us, “cities increasingly sell themselves on the feelings that they claim to generate” [Degen and Rose Reference Degen and Rose2021: 4], and that is why “no paving-stone, no door-handle and no public place has been spared this aestheticization-boom” [Welsch Reference Welsch1997: 8].

It is no surprise, therefore, that the reconstruction of Notre-Dame sparked strong reactions. In the words of Nathalie Heinich [Reference Heinich2021], Notre-Dame is a “total axiological fact”—something widely recognised as valuable—and, for many, the building is an objectification of the very idea of beauty. That is why the work of architects and conservation specialists was discussed so intensely, as they were making essential decisions about the building’s aesthetic appeal. But let us imagine what happened next. Even if architects and conservation specialists had reached agreement on a general aesthetic vision for the restored cathedral, this consensus quickly gave way to a host of concrete material decisions. What kind of wood should be used for the spire or roof? Where should it come from, especially when the original sources were no longer available? How would this material age over time? Should it be covered with patina, left untouched, or stained a particular shade? Even these seemingly minor questions—how often to clean the timber, how to protect it from pollution, and what kind of finish to apply—became matters of serious consideration. Seen in this way, the reconstruction of Notre-Dame turned into a series of ongoing negotiations over how aesthetic value should be materially manifested and cared for into the future.

While this article is not about Notre-Dame, I refer to this case to ask the following question: how can we understand the aesthetic dilemmas described above? Despite being central to everyday urban aesthetic politics, such dilemmas often go overlooked within sociology. In particular, political economy approaches [Ghertner Reference Ghertner2015; Jones Reference Jones2009, Reference Jones2024; Kaika Reference Kaika2010, Reference Kaika2011; Sklair Reference Sklair2005] typically analyse urban aesthetics through the lens of how aesthetic forms serve the interests of political and economic elites [Degen and Rose Reference Degen and Rose2024; Kaika Reference Kaika2011]. Such perspectives reveal that urban aesthetics are a “battleground [for] urban spatial power struggles” [Lindner and Sandoval Reference Lindner and Sandoval2021: 9], but they tend to reduce aesthetic politics to ideals and preferences— stable attitudes toward aesthetics—understood as directly shaped by political ideologies. As a result, the question of aesthetic value is viewed as relatively straightforward, and the many negotiations that people undertake to realise and materialise the value of urban beauty are left unexplored.

However, such aesthetic negotiations are particularly salient in places shaped by violent histories. In such contexts, buildings, rather than standing for something most people (seem to) agree upon, are embedded in clashing values and uneasy emotions. What if, then, we examined urban aesthetic politics not from the perspective of a total axiological fact—a site of near-universal value—but from the settings where urban beauty is entangled with trauma, ambivalence, loss, and disagreement? Shifting our focus to places marked by war, colonisation, annexation or radical political regime change exposes a different image of urban aesthetic politics. In this image, the question of how to achieve the value of urban beauty is fraught with additional tensions—tensions that are of profound importance to those who inhabit these places.

This paper offers a sociological view on urban aesthetics that privileges these tensions rather than obscuring them. To this end, it moves away from the focus on aesthetic preferences towards an examination of valuations and care. To articulate this shift and to examine what is at stake, I use the concept of styles of valuation, which I define here as distinct sets of practices through which people negotiate and care for concrete manifestations of urban aesthetic value. With this concept, I highlight differences in how people articulate what counts as good and bad aesthetics, how they grapple with a building’s metabolic and material processes, how they navigate tensions among competing values, and how they develop different forms of material care for aesthetics. Importantly, these practices do not align neatly with either a person’s “taste” [Sezneva and Halauniova Reference Sezneva and Halauniova2021] or their professional skills [Jones and Yarrow Reference Jones and Yarrow2023].

But why care? First, because care highlights not only how urban aesthetic realities are made, but also how they are sustained as beautiful and aspirational over time. While buildings “look desperately static” [Latour and Yaneva Reference Latour and Yaneva2017: 108], they regularly undergo processes of aging and degradation that demand maintenance and repair [Denis and Pontille Reference Denis and Pontille2025]. Second, care also becomes visible in its absence—in the neglect or abandonment of certain aesthetic realities in contrast to others. As Fernando Dominguez Rubio [Reference Dominguez Rubio2020: 51] writes, “While demand for care is always infinite—everything requires care—our capacity to care is always hopelessly finite.” Finally, care helps us move beyond the idea that people passively follow aesthetic ideologies and ideals. As AnneMarie Mol [Reference Mol2008] puts it, care is unique precisely because it does not follow general rules and universal ideals but is always tailored to specific settings. In this light, valuation and care go hand in hand.

So, what better place to learn these lessons from than one where even the smallest aesthetic change carries significant stakes? In this article, I engage in a study of an extraordinary and telling place—Klaipėda in Lithuania (former Memel). After WWII, the city was annexed from Germany, and its population was forcibly relocated. Since then, Klaipėda has experienced waves of repairs, aesthetic makeovers, and architectural reconstructions. These processes turned appearances of built environments into matters of care [De la Bellacasa Reference De La Bellacasa2011] for almost everyone in the city. In addition, like other Eastern European cities, Klaipėda occupies an interstitial position between Global North and Global South [Müller 2020]. This positioning means that Klaipėda works toward appearing and feeling like a truly European city, and these efforts often involve spelling out implicit assumptions tied to aesthetics. Thus, by examining Klaipėda’s turbulent history and its in-between status, we gain a better understanding of the tensions that arise with caring for the value of urban beauty.

The article proceeds as follows. First, I outline how the aesthetics of built environments have been approached within sociology. I draw on a growing body of work in the sociology of architecture that foregrounds architecture’s entanglement with political and economic ideologies and places it in dialogue with more recent sociological studies on aesthetics that explore how people engage with material environments through vision, taste, touch, smell, and sound. Second, I incorporate insights from the sociology of valuation and science and technology studies to propose a different tool for studying aesthetic politics: styles of valuation. Third, I illustrate what this tool brings into view through an empirical case study of aesthetic politics in Klaipėda. Finally, I reflect on the broader insights that the lens of styles of valuation opens up for understanding urban aesthetics.

To start, let us ask the foundational question: why do architectural aesthetics matter sociologically?

Politics by Aesthetic Means

Sociologists have long been interested in architecture [Elias (1939) Reference Elias2012; Foucault (1975) Reference Foucault2000; Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1977] viewing buildings as “materialised structures of the social” [Steets Reference Steets2016: 95]. Some described architecture as a totem—an anchor—that captures and solidifies collective memories in material form [Halbwachs Reference Halbwachs1980]. Others conceptualized architecture as a space for negotiating and reflecting collective identities [Jones Reference Jones2006]. And still others built on these insights, arguing that architecture not only reflects identities but also intensifies or diminishes them over time [Patterson Reference Patterson2020]. Across these different sociologies, one common idea emerged: architecture is a powerful tool that constitutes and modifies social relationships.

The aesthetics of architecture are not peripheral in these processes. To the contrary, they often become a central concern for economic and political actors. One illustrative example is the work of Maria Kaika [Reference Kaika2006], who showed the relevance of architectural aesthetics in crafting national imaginaries during Greece’s modernisation at the beginning of the 20th century. She revealed how neoclassical ornamentation and the use of marble in water dams—major political and infrastructural projects—served a dual function: projecting Greece as part of a modern, industrial Western future, while simultaneously evoking its classical heritage as a foundation of European civilization. Paul Jones [Reference Jones2020] offers another beautiful illustration. He examined two architectural projects in mid-19th century London to show how states and architects used architectural style to construct different evocative narratives of nation and time. Some architects saw Gothic architecture, with its medieval ornamentation and towers, as essential to making Britain’s national identity tangible, while others promoted neoclassicism, with its symmetry and Enlightenment ideals, as more fitting.

But what makes aesthetics so powerful across different contexts? Why do people repeatedly turn to aesthetics, fight over them, and mobilise them for a wide range of purposes? The answer lies in the way aesthetics translate abstract ideas and ideologies into tangible sensations [Mukerji Reference Mukerji2012]—experiences that feel “really real” [Meyer and Van de Port Reference Meyer and van de Port2018: 4]. When individuals engage with things aesthetically—through sight, taste, smell, and touch—they experience visceral reactions sensed as undeniable and universal truths—facts of perception [Rancière Reference Rancière2022]. In this way, meanings and ideologies become “felt in the bones” [Meyer Reference Meyer and Meyer2009: 5] rather than simply imagined. Julie-Anne Boudreau and Joëlle Rondeau express this insight beautifully: “When we are faced with something that speaks to our senses, we cannot name it (recognize it as something we know). We can simply ‘admit’ that it is touching us” [Boudreau and Rondeau Reference Boudreau and Rondeau2021: 19]. Jeffrey Alexander and Dominik Bartmanski address that process as enchantment [Bartmanski and Alexander Reference Bartmanski, Alexander, Alexander and Bartmanski2012: 10], since aesthetic surfaces exert influence on us “without [us] knowing it, or without [us] knowing that [we] know” [Alexander Reference Alexander2008: 782].

Architects play a crucial role in shaping architectural aesthetics and the subtle influences they exert on us, often without our awareness [Yarrow Reference Yarrow2019a]. But they are by no means the only ones who matter. As Paul Jones [Reference Jones2009] has argued, architecture is a complex social field, influenced by clients, state regulations, construction technologies, design practices, and media representations. He compellingly showed that under conditions of aesthetic capitalism—where architectural work is highly aestheticised and architectural images are used to brand and market places—architects are often incentivised to design buildings that are visually consumable in order to attract commissions from developers and investors. Similarly, Leslie Sklair [Reference Sklair2017] highlights the role of the transnational capitalist class, whose material interests significantly influence which architectural and aesthetic forms are promoted and valorised within globalised capitalism. Both authors emphasise the point that architecture is shaped by the dynamics of commissioning and architects’ dependence on economic and political actors.

However, this does not mean that architects follow ideological messages blindly. On some occasions, they can exercise relative artistic and political autonomy, as well as critically reflect on their professional practices [Yarrow Reference Yarrow2019a]. As a result, architectural aesthetics can become subject to contestations and clashing aesthetic tastes. Virág Molnár [Reference Molnár2005] vividly demonstrated this point when she examined Hungary’s post-war “Tulip Debate”—a conflict among local architects over the status and aesthetic value of national symbols in modernist architecture under state socialism. While some architects adorned prefabricated housing blocks with tulip motifs, others dismissed the designs as “tasteless camouflage,” sparking a broader debate about the meanings of national culture in architecture and modernity. By following what she called interpretative struggles and contests, she could demonstrate that architecture and its aesthetics are shaped not only by local architectural power dynamics but also by transnational influences and political views.

To sum up, existing sociological scholarship on architectural aesthetics equips us with powerful tools to examine the broader contexts in which the aesthetic value of built environments is produced and valorised. By focusing on global capitalist dynamics, power relations within the architectural field, and the ways economic and political ideologies are translated into aesthetic forms, these studies explain structural conditions under which aesthetic value takes shape. However, they often assume that urban aesthetics are relatively stable, or that aesthetic value is more or less straightforward—architecture is imagined as enduring effortlessly, and individuals are seen as materialising their aesthetic preferences without much friction. Yet, as the example of Notre-Dame de Paris shows, bringing aesthetic value into being is not a one-time act, but a continuous process of value-negotiations and future-oriented care.

One striking example for this comes from Krisztina Fehérváry’s [Reference Fehérváry2013] study of socialist-era housing estates in Hungary. These estates, constructed from reinforced concrete, were initially intended to offer residents a good life but failed to deliver on this promise due to their aesthetic shortcomings. Materialities that were meant to radiate beauty were seen to age prematurely, and people perceived these changes as evidence of the state’s neglect. As a result, not only did it discredit socialist aesthetics, but it also prompted people to question the competency and care of the socialist state. They came to believe that it was not simply an incompetent designer who failed to fulfil their promise. Rather, it was the socialist state itself. In this example, weathering and ageing concrete was no less relevant and consequential than the socialist promise of a good life.

Building on these insights, in what follows, I propose a view of urban aesthetics that foregrounds these and other aesthetic tensions at the heart of urban aesthetic politics.

Styles of Valuation

My approach builds on the pragmatist understanding of valuation [Dewey Reference Dewey1969]. Rather than treating values as given, I examine “the operations by which actors actually manifest the value they assign to this object” [Heinich Reference Heinich2020: 77]. This involves tracing multiple activities: how people categorise, classify, and qualify objects, as well as how they substantiate and stabilise value across different contexts. To say that sociology should focus on valuation activities does not imply that valuation is divorced from broader cultural and structural conditions. On the contrary, as Michèle Lamont [Reference Lamont2012] has shown, evaluative practices are always shaped by existing cultural frameworks, institutional settings, and economic structures, and several studies have provided evidence for this [Chiapello Reference Chiapello2015; Lamont and Thevenot Reference Lamont and Thévenot2013; Kuipers Reference Kuipers2015].

But focusing only on those broader structures risks missing a vital dimension of the aesthetic valuation of architecture: its purpose is not merely to express one’s taste or expertise, but to “make things better.” Aesthetic valuation, in this sense, is not a passive judgment made from a distance but an active attempt to engage with the material and aesthetic world one inhabits. Recent scholarship on valuation has underscored exactly this idea, showing that valuation is a performative practice that brings value into being through actions and interventions [Jones and Yarrow Reference Jones and Yarrow2013; Muniesa Reference Muniesa2014]. Valuation often involves a deliberate desire to improve or fix things. As Annemarie Mol and Frank Heuts [Heuts and Mol Reference Heuts and Mol2013: 137] put it, “Valuing does not just have to do with the question how to appreciate reality as it is, but also with the question what is appropriate to do to improve things”—often through acts of care.

Building on this point, I propose to examine urban aesthetic politics through the lens of valuation and care. Particularly, I propose the concept of styles of valuation—collectively shared and distinct ways in which people negotiate how to enact and care for a given value, in this case, the aesthetic value of built environments. While I am not the first researcher to use the term—Francis Lee and Claes-Fredrik Helgesson [2020] previously introduced it in their study of bioscience to “highlight differences in the valuation of scientific work processes, methods, and their relation to different yardsticks for ‘good science’” [Lee and Helgesson Reference Lee and Helgesson2020: 664]—I theorise the term further. I use the concept of styles of valuation to emphasise multiple ways in which people navigate tensions involved in bringing aesthetic value into being.

Studying urban aesthetics through the lens of styles of valuation means paying attention to three main dimensions. First, it involves examining which urban aesthetics people consider good and bad. Certainly, how people define good and bad aesthetics may include classical concerns with beauty and ugliness [Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1979]. But the concept highlights the fact that aesthetic valuation also involves a range of other concerns, such as originality, innovation, quality, accessibility, comfort, or collective memory. In other words, valuing urban aesthetics may be tied to distinct professional, ethical, and political commitments and sensibilities. Second, the research through the lens of styles of valuation requires us to analyse how people reason about what makes aesthetics better or worse. This involves exploring the justifications that people use when arguing and seeking compromises around whether one aesthetics is worthier and more deserving than another. And, third, studying urban aesthetics this way involves investigating what material practices people find appropriate and desirable to care for urban aesthetics well. Because urban aesthetics are inevitably shaped by weathering and decay, which Fernando Dominguez Rubio aptly calls the “relentlessness of things” [Dominguez Rubio Reference Dominguez Rubio2016], bringing aesthetic value into being always entails questions of material care.

Here, a reader might wonder: but how do particular styles of valuation emerge and circulate? While this paper does not aim to answer these questions, I want to highlight one important point. How people value or devalue urban aesthetics can reflect trained ways of seeing and judging developed within particular communities of practice. This resonates with Pierre Bourdieu’s [Reference Bourdieu1979] view of cultural production as a social field, where individuals learn to evaluate cultural products in relation to their position within the field. However, as Thomas Yarrow [Reference Yarrow2019b] reminds us, professional training does not determine practice in a fixed way but involves ongoing negotiations of what constitutes “the good” in multiple ways. It also involves negotiations with the material properties of the world itself [Bortoluci Reference Bortoluci2020; McDonnell Reference McDonnell2023], rather than judging them from a distance [Hennion Reference Hennion2017]. For this reason, I do not treat styles of valuation as direct reflections of power dynamics within fields, but as practical modes of navigating value—especially in moments of change or uncertainty.

Using the concept of styles of valuation is beneficial in many ways. First, it allows us to resist the assumption that urban aesthetic politics is only a matter of competing aesthetic tastes and power struggles [for a critique of the notion of “taste” in relation to urban aesthetics, see Sezneva and Halauniova Reference Sezneva and Halauniova2021]. Instead, it emerges as a form of negotiation over the common good—something people may dispute, but around which they are also expected to justify their actions and seek compromises [Boltanski and Thévenot Reference Boltanski and Thévenot2006]. Second, the concept highlights the fact that enacting aesthetic value is rarely straightforward. It involves navigating complex tensions—not only among different values, but also with the material realities of buildings and how they should be cared for into the future. Rather than smoothing over these tensions, this approach brings them to the forefront. And, third, styles of valuation are empirically open and flexible. Unlike Boltanski and Thévenot’s [Reference Boltanski and Thévenot2006] “orders of worth” or Heinich’s [Reference Heinich2020] “registers of valuing,” they are not tied to fixed repertoires and values. This makes the concept especially useful for studying cases marked by historical complexity, ambiguity, or contestation, and for comparing urban aesthetic politics across different times and places.

(Extra)Ordinary Place

To illustrate my approach, I engage in a study of one (extra)ordinary and telling place—the western Lithuanian city of Klaipėda on the Baltic seashore. Before 1945, Klaipėda was a German city called Memel. It belonged to the German Eastern provinces which were subject to explicit colonial policies of Germanization known as “inner colonization” [Nelson Reference Nelson2010]. Under the motto of mission civilisatrice, ethnic Germans were relocated to the eastern frontiers of the empire, which included Klaipėda, in order to improve literacy among the locals, advance agricultural productivity, and strengthen the “Germanness” of the territory. During World War II, Klaipėda was captured by the Soviet army and, as a result, annexed from Germany to Lithuania which had become part of the Soviet Union and was governed by the Communist Party.

With the conclusion of the war, Germans were expelled, while new settlers from Lithuania and Russia arrived in the city marked by a lack of political belonging, vandalism, and economic stagnation [De Zayas Reference De Zayas2006; Ther and Siljak Reference Ther and Siljak2001]. The city was a wasteland of brick, glass, and metal. In Klaipėda, 60% of the housing stock was reported to be in need of repair—a fact that Klaipedians know by heart. Industrial enterprises, water pipes, roads, and bridges: nothing escaped destruction and vandalism. The city was short of construction workers, architects and engineers, and newly arrived settlers and prisoners of war had no other choice but to pour their energies into patching up the city’s ruined fabric.

State annexation brought aesthetic changes. Things deemed German—street names, buildings, and monuments—were dismantled or radically altered, because, in the opinion of socialist authorities, they stood for “foreign” and “imperial” “Germandom” [Safronovas Reference Safronovas, Hein-Kircher and Misāns2016]. Signs of unwanted political rule, certain designs and objects were removed—a phenomenon known as the post-war “exorcism” [Thum, Reference Thum2011: 391]—since architectural aesthetics was understood as “ideological instruction” [Humphrey Reference Humphrey2005: 43] as to what could and could not be displayed. Architecture was central to the socialist state [Molnár Reference Molnár2013], and buildings were required to be “Lithuanianised” in Klaipėda. So, reconstructions, restorations, and stylistic alterations were employed to that end. It was not until 1990— the year when Lithuania declared its independence from the Soviet Bloc—that all things German not only drew additional investments but became the objects of public affection in the city.

With Lithuania joining the European Union in 2004, buildings once criticised for their aesthetics attracted people as the remains of “amputated” German pasts [Thum Reference Thum2011: 382]. Once again, these structures underwent waves of selective renovations, but now under the slogan of a “return to Europe” [Czaplicka, Gelazis and Ruble: Reference Czaplicka, Gelazis and Ruble2009] taken up in the name of recovering the buildings’ “historicity,” “authenticity,” and “Europeanness.” Yet, Klaipėda’s past remains contested even after 2004. In 2014, local newspapers warned inhabitants about provocation by the Russian government, where anonymous authors published a petition to annex Klaipėda—a city where 25% of the population was Russian-speaking—to Russia. That petition, however, was not the first of its kind, and similar desires to annex Klaipėda to Russia were expressed by Mikhail Gorbachev during the Lithuanian Independence movement and by Putin in 2005 [Grigas Reference Grigas2014: 4]—a wound reopened with the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022.

Studying aesthetics from Klaipėda, and not from New York, Barcelona, and Amsterdam, is a strategic choice. The multiple historical twists and turns that Klaipėda underwent make this city a telling case. By studying urban aesthetics from Klaipėda, I uncover aspects of aesthetic city-making that take implicit and obscured forms when explored in other locations. But in Klaipėda, residents ask themselves what it means to care well for different kinds of urban aesthetics, especially those tied to fraught histories of Soviet imperialism, state annexation, and German occupation. Writing about Klaipėda is also a step towards “theoris[ing] from elsewhere” [Bonura Reference Bonura2013]. While in sociology much is being said about the need to rethink theoretical vocabularies from different regional contexts, particularly, from the Global South, researchers often neglect to mention places that do not easily fit into the divide between the Global North and the Global South, that is, the post-socialist Global East. Writing about cities like Klaipėda is crucial, therefore, because it shakes up theories through the lens of places that are “too powerful to be periphery, but too weak to be the centre” [Müller Reference Müller2020: 736]. By thinking about urban aesthetics from the European semi-periphery, I can uncover complex gradations of value that stand behind seemingly coherent aesthetic ideals of Europeanness [Oancă Reference Oancă, Kolar, Krivonos and Pascucci2025].

Measuring Styles of Valuation

This raises the next question: how can we study styles of valuation empirically? In this paper, I propose one way to do so: by using a mixed-method approach known as Q-sort, which combines elements of qualitative interviewing, visual photo-elicitation, and factor analysis. As Eden, Donaldson, and Walker [Reference Eden, Donaldson and Walker2005: 414] explain, Q-sort helps “identify shared views […] and individuals’ affinity with those views.” The main goal of this method is to map individuals’ patterns of valuation based on people’s explicit and implicit ideas about urban aesthetics. Given that aesthetic value is often not clearly defined but “asserted through associations” and visual comparisons [Harms Reference Harms2012: 743], the Q-method is helpful in capturing different emotional and non-conscious processes that guide people’s aesthetic choices.

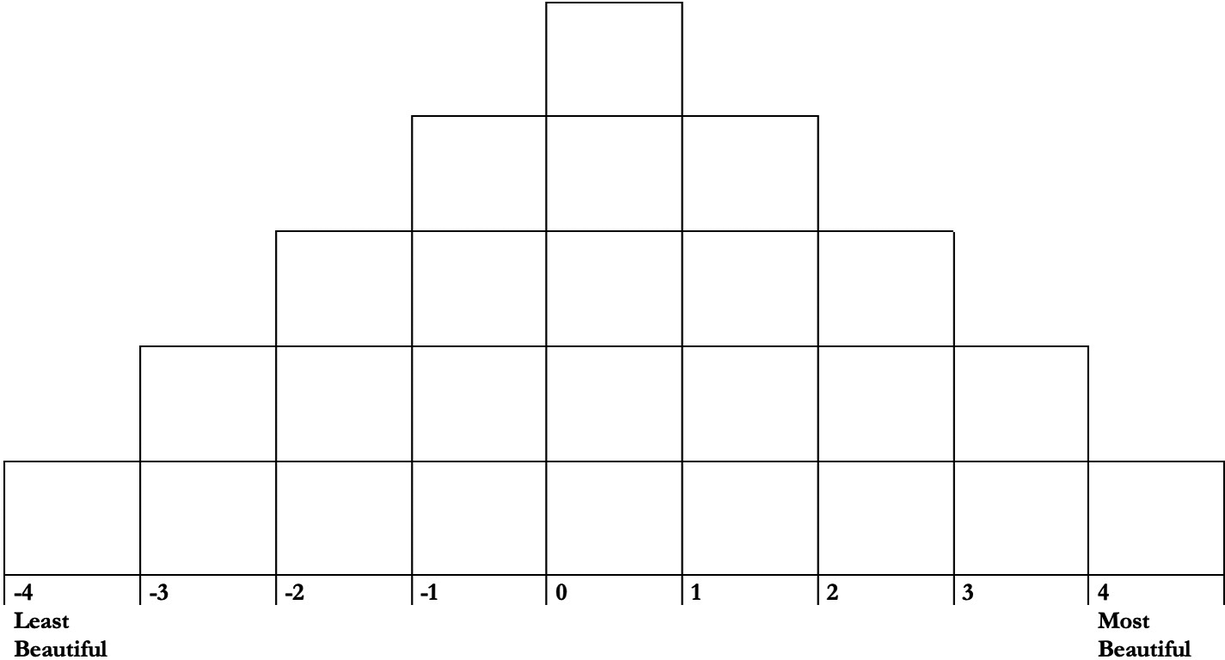

As I wanted to understand how people valuate urban aesthetics in practice, I met with urban professionals in the know—architects, urban planners, art historians, city officials, and activists concerned with urban aesthetics in their daily lives. To recruit participants, I contacted the city municipality and multiple architectural and urban planning offices, as well as reaching out to urban activists who participated in campaigns either in support of or against the city’s various architectural projects. In 2017 and 2018, before the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, I met with 30 people to ask one question: what architecture do you find most and least aesthetically attractive? People were asked to rank 25 pre-selected images of architectural sites on a bell-shaped grid from “-4” to “+4” regarding their aesthetics (Figure 2), and then explain their aesthetic choices in an oral interview, which was recorded, transcribed, and thematically coded.

Figure 2 Q-sort sorting scale

(Source: A. Halauniova, 2016)

Images for the Q-sort depicted architectural sites from various historical eras (German, socialist, and contemporary architecture), levels of maintenance and upkeep, functionality, and iconicity. They were selected on the basis of a preliminary analysis of media coverage, available historiographical descriptions, and expert interviews with local social scientists and tour guides. Using the varimax rotation procedure, I identified factors—or coherent logics—that defined how research participants sorted buildings, which I examined as distinct styles of valuation (Table 1). The intent of the factor-analysis was not to locate the most and least popular “tastes” that are representative of broader populations, but to capture distinct ways of valuing and devaluing architectural aesthetics.

Table 1 Overview of styles of valuation

Source: A. Halauniova, 2023

The method is helpful for a number of reasons. First, it enables the researcher to detect patterns of valuation that may not be explicitly articulated and are therefore difficult to capture through other techniques, such as interviews, since people’s valuation actions are often complex and inconsistent [Kuipers, Sezneva and Halauniova Reference Kuipers, Sezneva and Halauniova2022]. Second, the method allows us to conduct an in-depth analysis of commentaries that people give throughout the interview. That, for instance, reveals how individuals justify what makes for a beautiful or ugly building, and how biographical details, professional training, and personal memories matter in their aesthetic valuations. Third, the method allows individuals to describe their visceral reactions and hard-to-verbalise sensations, compare images that seem incomparable, and express doubts as to what should be counted as more or less attractive—aspects that conventional methods, such as interviews and surveys, access less successfully [Ibid.]. Finally, the method stages activities of valuation as a test in which individuals are their own researchers: they ask themselves questions, they change their minds in the course of an interview, and they critically examine their own ideas.

In what follows, I map and describe three styles of valuation that individuals in Klaipėda employed to value and care for urban aesthetics.

Different Beautiful(s) and Ugly(s)

Style of Valuation 1: Caring for the Prussian Character

In this style of valuation, city officials, architects, and activists valued German-period prewar architecture above everything else (Figure 3). They did not favour one architectural style, but preferred prewar buildings commonly recognised as cultural heritage. Research participants used different terms to describe valued buildings: “beautiful”, “the true identity” of the city, “the core of the city,” “the heart of the city,” and architecture that makes them “proud.” They deliberately focused on the architecture’s “Prussian character,” even if a building was constructed during the interwar period when Lithuania was independent and before Klaipėda was annexed by Nazi Germany in 1939 and then by the Soviet Union in 1945. In contrast, socialist-period modernist housing estates—especially those of the industrial functionalist style that flourished under Soviet rule—were consistently devalued. Participants reached for negative terms to describe them: “boring,” “standardised,” “deficient,” and “ugly.”

Figure 3 Highest ranked images in beautiful-as-Prussian style of valuation

(Photographs: Vilma Paulikaitė, 2017)

Nojus (Z-score: 0.5772)—an urban activist and trained philosopher in his early 50s—articulated this style of valuation most clearly. When sorting through the images, he commented, “The most important thing is respect towards the old objects in the city.” He picked up a photograph of the neo-Gothic Pedagogical Institute (Figure 3, Image 8) and said, “I like this building a lot. It is neo-Gothic. We don’t see that a lot in Klaipėda, but it is pretty typical. Red brick, everything is so harmonious. The shapes are exact, an example of the Northern style.” He explained that this “Northern style,” common across Northern Europe, including Lithuania, had largely vanished from Klaipėda due to wartime destruction. But even though scarce, these red-bricked constructions affect individuals on a deep, psychological level. According to Nojus and others, these buildings “bind” local inhabitants into one collective and make their “intimate” ties with the place real. “You cannot interpret it simply as a building,” he said. “These colors—you cannot imagine Klaipėda without these colors. It holds the whole city center together.”

All the same, urban beauty—at least in this style of valuation—does not exist without friction. As participants often reminded me, the German-period architecture they valued most for its beauty was also described as a “scarce” and “fragile” resource, something that demanded special protection—especially in light of the extensive material losses suffered during World War II. Jurgis (Z-score: 0.6427), an architect in his 60s who was born in Vilnius and moved to Klaipėda in 1980, commented on the German-period Pedagogical Institute, which he considered one of the most “beautiful” buildings in the city, in the following way.

This style has not disappeared, what was laid out in the 20th century, before the war, has not disappeared […] It is completely Prussian. You will find all the details here. You may not find anything similar in Kaliningrad anymore, but in other Prussian cities you will find lots of such buildings. Even in Gdansk.

Here, research participants saw as most threatening to the beauty of “Prussian” Klaipėda the perceived neglect of German-period architecture—both during the Soviet era and continuing into the present. They described this architecture as at risk of “disappearance”, and they expressed genuine concern for its future. The perceived fragility of these buildings, especially in relation to “neglect” and “improper” care, became even more evident in how participants spoke about changes to their appearance. Alterations were often described as “wounds,” “marks,” or even “invasions” that disrupted the “coherence” and “harmony” of “Prussian” Klaipėda. Aldona (Z-score: 0.7518), for example, a city official in her early 50s, spoke of the Bauhaus-style Vytautas Magnus Gymnasium (Figure 3, Image 24) as follows.

I loved it more before the reconstruction. The whole street was made of these red bricks, old buildings. It was a good ensemble. And now, after the renovation, it stands out.

Thus, caring for urban beauty in this style of valuation means committing to what is called “respectful” renovation. Research participants described such care as essential to preserving the integrity of “Prussian” Klaipėda. They framed respect for this architecture as a moral obligation of every citizen—something any “conscious” person should uphold. Ugnė (Z-score: 0.8155), a city official in her 40s, who moved to Klaipėda in the late 1990s and studied archeology, explained this as follows.

The preservation of old buildings means that… it says something about that society, not the building itself. When you cherish cultural heritage, and when you preserve it, and when you reconstruct it, you can accept your past well. You can live in the present, and you can make plans. You stand very stable on the ground then.

Here, Ugnė understands the preservation of German-period architecture not only as a personal ethical commitment, but also as a way of sustaining the vision of Klaipėda’s monumental time [Herzfeld Reference Herzfeld1991]—a grand and stable historical narrative that underpins a city which, until recently, had experienced annexation as well as both German and Soviet occupation.

For Ugnė and others, respecting German-period buildings means acting on them aesthetically—specifically, preventing them from being “spoiled.” But what does this mean in practice? Research participants described spoiled architecture as that which had undergone visible material changes that altered its “character” and disrupted their established sensory expectations of how “Prussian” Klaipėda should appear. But spoilage was not limited to renovations alone: the construction of new buildings that dramatically changed the visual landscape could also diminish the perceived beauty of historical structures. For instance, Janina (Z-score: 0.8168), an urban activist in her late 50s, who moved to Klaipėda in 1975 and identifies as Baltic and Lithuanian Prussian, expressed deep disappointment when evaluating the modern K and D towers (Figure 4), built in 2007 in the historic city centre.

With these two skyscrapers, they spoiled the whole city! Too close to the Old Town. The historical centre is there. I was a witness to the demolition of the old fire station. It was in the 1970s, and now again. The silhouette of the old Klaipėda is being damaged. Move it to the new neighbourhoods. Leave the Old Town alone!

In this sense, caring for German-period architecture well means caring for the “silhouette” of the Old Town as it was imagined to have looked before Soviet rule. This idealised vision of the past is what residents consider worth protecting. Within this style, even the proximity of an “ugly” or incongruent building is seen as contaminating the beauty of the “Prussian” city.

Figure 4 K and D Towers, 2018

(Photograph: Vilma Paulikaitė)

Yet, abandoned German-period buildings in a visibly deteriorated state were not considered spoiled. For instance, an urban activist Janina expressed her admiration for the German-period Prison and Court Building built in the 1870s in the following manner.

This is a typical Klaipėda. It must be rebuilt because it belonged to history, it was part of Prussian Germany. Red bricks, these windows… It must be preserved, it is a good house, nothing has been altered, nothing has been damaged, nothing has been spoiled.

In this sense, conserving, renovating and repairing German-period buildings is not always considered “proper” care for their beauty. Sometimes, participants regarded the absence of investment—and even the lack of alterations—as the truest way to preserve the architecture’s “Prussian” essence. Care, then, could mean leaving things untouched, allowing the buildings to remain as they were rather than risking change and “wounding”.

What did research participants devalue within this style of valuation? They contrasted the “beautiful” Prussian architecture with socialist-period modernist constructions, which they saw as a “threat” to the “cosy,” “Prussian,” and “European” character of the cityscape they admired. What participants sought to avoid was the architecture’s lingering socialist “nature” [Murawski Reference Murawski2019]. Socialist-era mass housing estates were regarded as spoiling Klaipėda’s aesthetic appeal and undermining its image as a “happy,” “prosperous” place. During an interview, city official Ugne described one such modernist housing estate (Figure 5, Images 15 and 25) this way: “There are lots of these buildings. They create the atmosphere of a poor life. Unhappy people might live in these houses.” Similarly, Petras, a city official in his 60s who works for the Klaipėda Department of Cultural Heritage, expressed his disappointment with the socialist modernist estates.

I think this is the ugliest architecture that was ever constructed, ever. In the whole world. It is made of concrete which will crumble if one does not renovate it. It is a mass architecture, typical everywhere, and it has no character. It creates a completely anonymous image of the city.

Figure 5 Lowest ranked images in beautiful-as-Prussian style of valuation

(Photographs: Vilma Paulikaitė, 2017)

When it came to “ugly” socialist-period mass housing estates, research participants insisted that the constructions require radical aesthetic changes. For example, this is how a city official named Egle described the housing estates built in the 1960s from reinforced concrete, structurally solid, and still inhabited today.

In photo 15, everything is already in a critical condition. It looks like the building might fall apart. In [photo] 19, you can see the quality is better. Here, you can live. We can see that all the pipes, all the electricity communications were replaced with new ones. It looks now more energy efficient.

Inspecting the building’s facades visually, Egle stated that the second building, which has been repainted in vivid colours, had been visibly “improved,” and she assumes that visual improvement carries “better” living conditions. While neither Egle nor Ugne drew on their personal experiences of living in identical housing estates, they were confident that their visual appearance stands for their physical “deficiency.” Here, a change in colour is the main means for “improvement.” Since the ugliness of socialist-period architecture stems from its “anonymous look,” repainting the facades in bright colours is seen as something that efficiently distinguishes the freshly repainted buildings from the “drab” eyesores of the socialist period.

However, sometimes changes to a building did not adhere to research participants’ visions of “orderly” and “decent” renovation. For example, in one case, residents updated their balconies and window frames in a non-concerted effort, and research participants qualified that building as “chaotic,” “disorderly,” and “less civilised.” Janina described a socialist-period housing estate as follows, “It looks horrible… Each person did things higgledy piggledy […] They live like gypsies.” Here, Janina draws a boundary between orderly and disorderly landscapes by invoking the figure of Romani people as a racialising generalisation for “less civilized” ways of being. As Giovanni Picker [Reference Picker2017] argues, the stigmatisation of “Gypsy urban areas” populated by Romani households persists across Europe, rooted in the continuity of racialised difference-making. This phenomenon is not accidental but signals the ongoing production of a racial and civilisational hierarchy within Europe, in which Romani people are cast as not-quite-European Others. Building on this racial and civilisational imaginary, Janina constructed a hierarchy between “proper” European urban space and a “disorderly” socialist period landscape. As a result, she recast socialist-era modernist built environments as inherently “non-European.”

Style of Valuation 2: Caring for Historical Truth

In this style, research participants—mostly architects—preferred architecture from any historical period and of any architectural style if it was deemed “credible” (Figure 6). These individuals valued German-period and socialist-period constructions alike, describing them as “original”, “authentic”, and “truthful”. The level of upkeep was a less significant factor for them. In contrast, research participants consistently devalued contemporary capitalist constructions and historical reconstructions and described them as “fake” and “inauthentic” (Figure 7).

Figure 6 Highest ranked images in beautiful-as-credible style of valuation

(Photographs: Vilma Paulikaitė, 2017)

Figure 7 Lowest ranked images in beautiful-as-credible style of valuation

(Photographs: Vilma Paulikaitė, 2017)

Rytask (Z-score: 0.8922)—a well-traveled architect in his early 30s who studied in the UK—offered a clear example of this style of valuation. He pointed to the socialist modernist Music Theater, built in 1964 and devalued in the previous style of valuation (Figure 8), and commented.

This is an old musical theater. I like it. I like all the materials, the rhythms, the top part, the old clock. As a building, it’s really nice. This upper part of the building became sort of an accent for the city, a landmark. This is why it’s nice. You can also see the ideas, the visions that were important for people at that time.

Figure 8 Renovated and repainted socialist modernist housing estate

(Source: A. Halauniova, 2017)

In this fragment, Rytas describes an otherwise widely disliked building as “nice” and as a credible representation of its historical context. He expects a “beautiful” building to be historically identifiable, and in this framing, Soviet-period architecture is not devoid of authenticity. Rytask “read” the history of architecture from the building’s appearance and stylistic features, which turned a stand-alone architectural construction into the “spokesperson” for its own historical settings.

Another architect named Danutė (Z-score: 0.8702)—also a young and well-travelled professional—echoed Rytask’s understanding of good aesthetics. She valued the socialist-period modernist summer estrade as the “most beautiful” building in the city, even though the construction was visibly dilapidated and abandoned.

I really like that this is open, that this is completely different, and it’s public, it’s open to everyone, it’s recreational. I love its construction, the beams, steep and, at the same time the room is really light, even though the constructions are very heavy. It looks very abandoned now, but it’s very poetic. It’s just nice to be there. It’s very huge. It has a historical past.

Danute highlighted the structure’s “poetic” appearance, and she narrated it as a “sculpture-like” object, downplaying what people employing other styles of valuation immediately saw as the construction’s repulsive socialist “character” and “deficiency.” Although Danutė acknowledged the building’s dilapidated appearance, this did not diminish its value in her eyes. For her, it remained “beautiful,” “authentic,” and “historical.”

This understanding of architecture draws from classical conservation theory, which treats a building’s “truth” as a core value to be preserved [Muñoz Viñas Reference Muñoz Viñas2005]. Here, “truth” is defined in terms of an object’s internal “integrity”—its coherence between form, structure, and origin. A similar logic runs through architectural history, where “truth” refers to a building’s ability to reflect its structural logic, the architect’s intent, and its historical moment [Forty Reference Forty2013]. It is no surprise, thus, that it was primarily architects who emphasised “truth” and “integrity” as virtues of urban aesthetics. Through their professional training and ‘skilled vision” [Grasseni Reference Grasseni2004], they are equipped to recognise the historical narratives embedded in buildings [Yarrow Reference Yarrow2019b]. In doing so, they attempt to detach architecture from accumulated social or political associations—such as dismissing modernist buildings as merely “Soviet”—and instead place them within a broader trajectory of architectural history.

And yet, the significance of “truth’ as a value in this style of valuation is deeply localised. Research participants emphasised that this particular form of beauty matters because it does not “betray,” “lie,” or “trick” local inhabitants in contrast to many architectural projects completed in Klaipėda during past decades. An architect named Paulius (Z-score: 0.5556), who studied in Lithuania and Germany, shared his understanding of “authentic” architecture as that which does not “imitate” the appearance of historic buildings.

Imitation is bad for the city: if we have lots of old objects, we should renovate them instead of trying to copy them. Otherwise, the building would be a huge lie.

As both Rytask and Paulius noted, Klaipėda’s urban development has not discouraged—but rather encouraged—the construction of historical imitations. This aesthetic and political trend deeply concerned them, as they recognised the powerful role architectural aesthetics plays in shaping historical narratives about a place. For them, architecture belonged to the realm of ethics and politics as much as aesthetics. Their aesthetic judgments were guided by a moral imperative: buildings should truthfully reveal their historical origins.

Caring for good aesthetics well in this style of valuation involves practices that assume “respect” for a building’s “originality.” For example, Rytask expressed his disappointment with the renovation of socialist modernist mass housing estates, which was celebrated as an aesthetic improvement in the previous section, since it involved plastering and repainting the building’s facades in bright colours (Figure 8).

It is a concrete construction, housing. Many people live here. So, the renovation should respect this original idea. If it is concrete, it should remain such. After renovation, it becomes weird and kitsch. They add all sorts of colours for the sake of colours.

Rytask and others highlighted that caring for urban beauty is a moral duty of local inhabitants, but it must be done properly by preserving each building’s “character”—an “honest” representation of its historical period and style. For them, maintaining “credible” and “truthful” architecture is crucial not only because buildings are material evidence of the past, but also because “‘respectful’ renovations enable them to retain their unique feelings, ‘personalities,’ and ‘auras”’ that must be preserved.

What did research participants devalue within this style of valuation? They contrasted the “beautiful” and “truthful” architecture with contemporary capitalist constructions of Klaipėda, which they described as “bad”, “less attractive”, and sometimes “ugly”. They devalued three buildings in particular: the reconstruction project for Klaipėda Castle (Figure 7, Image 22), a mass housing estate built in the 2010s (Figure 7, Image 11), and the reconstruction of the socialist modernist Music Theatre (Figure 7, Image 7) that was being completed at the time of study. All three buildings were described as “bad” or even “shit” architecture. For Rytask and others, the ugliness of contemporary capitalist constructions comes from them producing “false” and “untruthful” narratives about the city and its architectural history. But even more than that, these buildings lack the materiality that people consider “good craftsmanship.” This is how Rytask explains why the reconstructed Music Theatre “lost” its “‘original” material feeling.

Rytask: This is what happens when you do not want to hold a competition … And they end up with this shit architecture. OK, maybe it is not that shit […] I think that the tower will lose its materiality…

Interviewer: What kind of materiality?

Rytask: It will become some sort of flat, new, cheap … that will fall off after a couple of years. And it won’t be this sort of nice architecture. It will be cheap. This is what I am afraid of. But hopefully I am wrong.

Rytask contrasted the “truthful,” “authentic” version of the Music Theatre with “cheap” reconstruction. He stated that once the concrete facades of the building come to be resurfaced and plastered over, the building would lose what art historian Adrian Forty [Reference Forty2013: 289] calls its “expressive truth,” that is, its capacity to be “true” to its own “essence” and to its creators.

In this style of valuation, “ugly” buildings are morally and civically “bad,” because they manifest “bad” urban governance that is preoccupied with aesthetic spectacles and the invention of “fake” historical genealogies. This is in contrast to Paul Jones’s [Reference Jones2009] analysis of architectural practice as a Bourdieusian social field, in which architects downplay their connections to political and economic interests, reframing these concerns in architectural and aesthetic terms. The following highly emotional description of the K and D towers by Rytask is telling.

This represents greed, stupidity and flashiness in the city where you should not have it […] In Klaipėda, most churches were bombed, we do not have many towers. So, these towers sort of replace them […] But you just produce more empty space […] This does not make the city better. It’s just something flashy.

Rytask explicitly condemned urban governance that valorises architecture’s grandeur, symbolism, and iconicity. Like many others sharing this style of valuation, he labeled such buildings as “bad” or “ugly,” expressing feelings of anger, disappointment, and anxiety with respect to their designs. Yet, research participants in this style of valuation avoided further reflection on the subject. For them, “ugly” architecture is materially unfixable or it does not assume the necessity for political intervention.

Style of Valuation 3: Caring for Distinction

In this style of valuation, research participants—mostly activists and city officials—favoured buildings that they described as having “distinctive” character and that brought visual “difference” to the cityscape. They valued both German-period and contemporary buildings that indexed German-period architecture via timber frames, red clay brick, or red ceramic tiles (Figure 9). In contrast, they devalued Soviet-period architecture of any architectural style. They found modernist socialist mass housing estates particularly “ugly,” describing them as “serial,” “typical” and “standardized” (Figure 10).

Figure 9 Highest ranked images in beautiful-as-distinctive style of valuation

(Photographs: Vilma Paulikaitė, 2017)

Figure 10 Lowest ranked images in beautiful-as-distinctive style of valuation

(Photographs: Vilma Paulikaitė, 2017)

Roze (Z-score: 0.8530)—an activist in her early 30s, well-travelled and trained as an archeologist—exemplified this style of valuation. When looking at images of German-period architecture, such as the Pedagogical Institute, the Prison and Court Building, and the Drama Theater, she said the following.

I describe them together because they are among the few surviving authentic buildings. They are related to German culture, the culture of the lost city. They are really beautiful, even when unrenovated.

Similarly, Motina (Z-score: 0.5618), a historian employed by Klaipėda’s Office of Culture, described the architecture she valued most as follows: “I like that red brick architecture. It reminds me of Old Klaipėda, things that remained from the city, people who lived in the prewar city, and what used to be here.”

Both Roze and Motina had significant difficulty explaining why they find some buildings more “beautiful” than others. But time and again they pointed to buildings constructed from red brick or employing materials of the color red, regardless of the architectural style or historical period. Ona exemplified this shared fascination, describing “beauty” as something that the red clay brick “naturally” radiates.

It is beautiful because of the red bricks. If it would be renovated, it would be more beautiful. But I do not know why I like red bricks. They are beautiful, just beautiful. I do not want too many buildings made of red bricks, but while we have several such [buildings], they are not ordinary. Which makes them cozy and beautiful. Every time you see it [red brick]—you know for sure it belongs in the city.

Ona and others using this style of valuation elevated red clay brick from the status of an ordinary, unremarkable material to an aesthetically and culturally “distinctive” medium. They addressed red-brick architecture and architecture constructed out of red materials as something that materializes the city-that-no-longer-exists, but which is nevertheless of great interest to them.

That passion for red bricks was shared by everyone in this style of valuation, but a clear tension emerged. While participants celebrated red brick as a defining feature of Klaipėda, they emphasized that not all red bricks carried the same value. In the 1960s, some local architects chose red clay brick over grey concrete and white silicate bricks for mass housing estates. Initially, this aesthetic choice was praised for linking the German past with the Soviet present. Over time, however, these bricks began to show signs of wear. Residents came to distinguish between the “German” red brick and the “Soviet” red brick. The first, “German” brick was described as possessing the properties of endurance, weightiness, ageing in a desirable manner (patina), and more importantly—aura—which rendered it an object of admiration and delight. The second, “Soviet” brick was devalued because of its “standardisation,” signs of ageing in an undesirable manner, fragility, and the perceived lack of aura.

Based on this, research participants insisted that “Soviet” and “German” red bricks were different and required different treatment. Activist Janina contrasted the two materials, describing the “Soviet” red brick as “a complete disaster” and adding: “It looks ugly, of low quality. You can easily see the dilapidation—the brick crumbles. It looks truly horrible.” Another activist, Roze, provided a rational explanation for the difference between the two materials: “You can see that they [“German” bricks] are authentic, not of identical size, slightly protruding. This shows that they are handmade.” Roze specifically referred to architectural qualities such as texture (“slightly protruding bricks on facades”) and uneven size to justify her valuation of red “Soviet” bricks as “drab” and “grey”. While the bricks she described were not physically “grey,” the close association of Soviet-period architecture with “greyness” prevailed over the structure’s actual material qualities.

“How do bricks from the Soviet and the German period differ?” I asked an activist named Nojus. He laughed.

They differ in everything. Color. Quality. The architecture itself. “Soviet” bricks fall off every winter. They don’t have this deep, deep red color. When you touch the brick with your hands, the feeling is so different. In the neo-Gothic architecture, one can feel the quality: the brick is pleasant to touch. It affects a person psychologically. People [former residents of Memel] built the architecture differently. They knew what they were doing. They did it with love. Not with the ideological sham [butaforiya].

In addition to bricks, research participants also valued timber and the use of wood in architecture. Roze, for example, commented on an image of a hotel reconstructed in a timber-frame style as follows.

The hotel building has been reconstructed. It is newly built according to an authentic model. And to me it is beautiful because they used an authentic model, but it was adapted to a modern approach. This is an imitation of timber framing, which is typical of German architecture, but instead of bricks, they used glass […] In any case, this reminds us of Klaipėda, that German Klaipėda, and that changing Klaipėda.

Thus, in this style of valuation, research participants valued German-inflected architectural constructions as embodying good aesthetics, placing less importance on the age-value or material authenticity of the buildings. A similar dynamic was observed by Olga Sezneva [Reference Sezneva2012] in Kaliningrad, another post-German city, now in Russia. There, residents also expressed admiration for German-inflected architecture, which Sezneva interpreted as an effort to construct a “collective genealogy” that integrates the German past into the present. In Klaipėda, too, participants used their appreciation of German-inflected architecture to imagine a sense of historical continuity and to “repair” the collective sense of rupture caused by the Soviet era. In addition to that, they described Klaipėda as not-quite-typical Lithuania. They “extracted” the Klaipėda region from the rest of Lithuania—associated with Russian imperial rule before 1918—and magnified its socio-historical and aesthetic distinctiveness.

An interview with Tiesa (Z-score: 0.8120), an activist in her 20s who studied philosophy, illustrates this point very clearly. When describing the Old Mill Hotel—a contemporary building using the fachwerk technique that Rytask strongly disliked for its “fakeness” and “decorativeness”—she shared her affection for it.

This reminds me of German-style architecture. We have a few of such buildings in the city. Which makes Klaipėda a bit more special than other cities in Lithuania. I like that it looks really old, windows with wooden things on them make me want to open them […] I used to think that this is what makes Klaipėda special, but then I realized that other places in Europe have more of them. Maybe it is special in Lithuania.

In this fragment, Tiesa searches for visual signs that refer indexically to the pre-Soviet layer of history. Together with others, she acknowledges that her aesthetic likes are driven by her appreciation for Klaipėda’s distinctiveness in relation not only to the “East,” that is, Russia, but to the rest of Lithuania. This distinctiveness casts Klaipėda as more “European” than other Lithuanian cities due to its “special” regional history and material aesthetics.

The material care deemed desirable for maintaining urban beauty in this style of valuation requires more than minimal interventions. To the contrary, research participants considered radical changes “good” if they produced the feeling that the buildings “matched” the imagined and desired impression. These individuals were equally delighted by “original” German-period architecture, historicist reconstructions, and contemporary architecture certain architects called “fake” in the second style or “disturbing” in the first style, for example, the K and D towers. What people in this style of valuation found important was that buildings conformed to a visual grammar that mimics the Old Town and hence their desired image of Klaipėda.

In contrast to German-period and German-inflected architecture, research participants devalued Soviet-period architecture. They found modernist socialist mass housing estates particularly “ugly.” They deliberately focused on the architecture’s perceived lack of “expressiveness” and “character.” Tiesa, for example, described the State Music Theatre, which was valued as beautiful in the previous section, as follows.

The least beautiful is 21. As I mentioned before, it looks very ugly. Even the reconstruction project looks ugly… Not that ugly, they will change the windows. But the top part… it is made of blocks, in grey colour… has a different shade to it. Really ugly. They [the architects] do not have much imagination.

Roze and others emphasised that Soviet-period architecture was “aggressive” and “heavy” in contrast to the “cosy” and “fragile” German-period and German-inflected historicist buildings. Even buildings that employed aesthetic devices, such as the use of red brick instead of grey concrete block, disturbed people viscerally.

What kind of “care” did state officials and activists in this style of valuation propose for “ugly” architecture? How, in their view, should such structures be “fixed”? For many, architecture from the socialist period appeared beyond redemption, requiring massive investments and radical structural changes to make it desirable. They believed its lack of “character” and “poor” quality were too deeply ingrained to warrant preservation. As Ona bluntly put it, “I think it requires too much work. I would just destroy it. No need to keep it.” For her, demolition was the only viable option, given the significant material and emotional costs of attempting to “improve” these buildings.

To Conclude: Beauty, Care, and Difficult Pasts

How can we uncover the “far more complex aesthetic politics” that existing sociological analyses have yet to offer [Gastrow Reference Gastrow2017: 379]? This article offers one possible response. Departing from the dominant political economy framework, it introduces a view on urban aesthetics that moves away from focusing upon the broader social context in which aesthetic value is produced and valorised towards practices of valuation and devaluation themselves—practices through which aesthetic value is brought into being. This shift in perspective allows us to see how people practically resolve the tensions that are intrinsic to aesthetic politics: for example, tensions between different values and imperatives, or tensions between aesthetic aspirations and the material realities of urban environments. More importantly, focusing on valuation draws attention to the role of care in aesthetic politics. Urban aesthetics are not only produced but they must be sustained, which requires ongoing acts of maintenance and repair that ensure that aesthetic value endures. In this sense, urban aesthetic politics is inseparable from material care: from decisions about what to maintain or neglect, and how to care for it well.

I took this approach to Klaipėda to explore the aesthetic dilemmas faced by urban practitioners in a city shaped by a layered history—first subjected to Germany’s “inner colonisation,” and later annexed and occupied by the Soviet Union. There, professionals in the know valued urban aesthetics in three distinct ways—what I call styles of valuation. Some valued Klaipėda’s “Prussian” character and contrasted it with the Soviet-era housing estates that dominate much of the city. Others appreciated architecture from various periods, as long as it remained “truthful” to its historical context and the architect’s intent—while devaluing contemporary historicist reconstructions. Still others valued buildings that visually resembled the “German” style, regardless of their age, in opposition to socialist modernist forms more broadly. In each case, urban beauty was implicated in much more complex concerns and tensions: how to honour the “Prussian” essence without “wounding” it; how to respect the architect’s vision even when the architecture is unloved, particularly, in the context of the de-communisation of Lithuania; or how to admire German-inspired architecture while rejecting similar materials produced under the Soviet regime. To navigate these tensions, professionals proposed different forms of care—and, at times, neglect.

Seeing urban aesthetics in this light has several advantages. First, it helps us to resist the assumption that urban aesthetics are relatively stable, and that aesthetic value is straightforward—architecture is imagined as enduring effortlessly over time, and individuals are seen as materialising their aesthetic preferences without much friction. Questioning this assumption is especially important when we study places like Klaipėda that have been shaped by turbulent histories, such as war, annexation, or political regime change. Second, the approach provides tools to examine urban aesthetic politics as a site of public action and negotiation of the common good. Individuals do not only interpret aesthetics differently or struggle over who gets to define them—they are also expected to justify their actions and negotiate with others through different styles of valuation. Finally, this framework is open-ended. The list of styles of valuation is not fixed, which makes it possible to capture what is at stake in specific case studies and to support historical and geographical comparison.

I do not mean to suggest, however, that political or cultural political economy approaches are unhelpful. Rather, the lens of styles of valuation offers a valuable addition—one that helps us better understand the practical and often ambiguous processes through which urban aesthetic value is negotiated and cared for over time. But the reader must beware: care should not be romanticised within urban aesthetic politics. As this paper has shown, urban practitioners often speak of care as something reserved only for built environments that support the grand narratives of “monumental time.” In this story, “fragile” German-period architecture deserves care, while “deficient” socialist architecture often does not. As Michelle Murphy [Reference Murphy2015: 719] warns, we should not equate “care with affection, happiness, attachment, and positive feeling as political goods.” In Klaipėda, care is often reserved exclusively for the material remnants of the city’s imagined “European” past, framed as a form of a superior civilizational lineage.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to Olga Sezneva and Giselinde Kuipers for their guidance and for the careful readings of my multiple drafts; their work inspired me to think sociologically with beauty and ugliness. I am wholeheartedly thankful to Filippo Bertoni, who gave me the confidence to stay with the notion of care in my analysis. This article also benefited from the generosity of over thirty planners, architects, art historians, city officials, and activists who expressed interest in and engaged with the research project. I am additionally deeply thankful to Andželika Rimkuvien, who assisted me in conducting interviews in Lithuanian and in collecting archival materials; to Liutauras Kraniauskas, who kindly connected me with architectural professionals and activists in Klaipda; and to Vilma Paulikait, who took me on a photographic walk through the city. Finally, I would like to express my appreciation to the anonymous reviewers and the journal editors for their insightful comments, questions, and constructive recommendations, which made both the argument and the writing more evocative and clear.