As part of its collaborations with CARLA, in 2022 the anti-racist collective Identidad Marrón, made up of people who define themselves as descendants of Indigenous people, peasants and migrants, carried out an intervention at the Museo de la Cárcova, in Buenos Aires, aimed at making visible the persistence of structural racism in Argentine art.Footnote 1 The choice of museum was not accidental: exhibited in its rooms, among other plaster casts, are copies of works from the great European museums such as the Louvre and the Galleria dell’Accademia, brought to Buenos Aires to educate national artists in European aesthetic canons. The intervention of Identidad Marrón consisted of a series of performances by artists identifying as marrón (brown) in some of the rooms where these casts are exhibited.Footnote 2 The mere presence of their non-white bodies interrupted a space conceived according to Greco-Roman canons of beauty. They thus exposed the way in which racism and Eurocentrism defined the constituent artistic policies and discourses of Argentine art.

As in Argentina, in much of Latin America the classical European canon has functioned as a model when institutionalising a national art form. However, in most countries of the region there were attempts to hybridise these European ideas with elements that were perceived as more ‘autochthonous’, linked to mestizo, Indigenous or Afro-descendant peoples. Although it was a problematic and controversial matter, most Latin American nations recognised the mediation of non-European factors in the shaping of their cultural imaginary, albeit in a subordinate position. In the Argentine case, on the other hand, the national culture, as conceived by the ruling elites of the late nineteenth century, obliterated any possibility of heterogeneous visions of the nation. The narrative that these elites proposed deliberately rejected mestizaje and promoted, instead, the idea of Argentina as a white and European country (Geler Reference Geler2010; Quijada Reference Quijada, Quijada, Quijada and Schneider2000). According to the official discourses of the time, which persisted through the twentieth century, white and European Argentina was the result of two simultaneous and interrelated processes: the mass arrival of immigrants from Europe and the progressive ‘extinction’ of native peoples and Afro-descendants due to wars, diseases and their supposed racial ‘weakness’.

The whitening of Argentina in the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth was not merely an ideological construct. At a time of great transoceanic migrations, Argentina was the Latin American country that received the most immigrants as a proportion of its local inhabitants. But despite the transformative impact of overseas immigration, Argentina never experienced a total Europeanisation of the population. Afro-descendants, native peoples and so-called criollos remained very numerous, especially among the working classes and outside Buenos Aires and the centre of the country. The term criollo is an important one, as it became a common denomination for many people of mixed-race origin. Criollo is most often used in Hispanic America to mean someone of Iberian ancestry born in the Americas.Footnote 3 In Argentina, the term’s usage broadened following the onset of European immigration in the late nineteenth century, and as a reaction to it. It came to encompass people and cultures predating overseas immigration, yet not identified as Afro-descendant or Indigenous. The term maintained this ambiguity, signifying whiteness – because of the long-standing association of criollo with Spanishness – while also suggesting a certain presence of non-white, particularly Indigenous, elements (Chamosa Reference Chamosa2010). In some ways, criollo was analogous to ‘mestizo’, especially in a context where mestizaje was overtly rejected.

Because of the colonial heritage as well as the political and economic directions taken by Argentina after independence, these inhabitants were the ones who received the worst educational and labour opportunities and remained in a subaltern social position. In the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth, they were also forced to adopt a civic ideal of nationality that excluded any ethnic-racial difference and assumed the European character of the social formation, which implied for them a silent but systematic racism (Adamovsky Reference Adamovsky2012; Frigerio Reference Frigerio and Lechini2008; Geler Reference Geler2010, 2011; Lamborghini, Geler and Guzmán Reference Lamborghini, Geler and Guzmán2017). Non-white people were integrated into a lower class stripped of any racial reference (Adamovsky Reference Adamovsky2012; Ratier Reference Ratier2022). In other words, everyone was simply ‘Argentine’, without differences. But since the official narrative asserted that Argentines were descendants of Europeans, those who did not fit this national type because of their skin colour or because of their Indigenous, Afro-descendant or mestizo ancestry were forced, by the actions of the ideological state apparatus, to embrace a form of Argentineness that, in practice, condemned them to subaltern positions, socio-economically, politically and culturally (Briones Reference Briones2005; Geler Reference Geler2016). The Argentine nation-state project devised at the end of the nineteenth century was thus based on a double axis: if on the one hand the reproduction of social disparities maintained structural racism (among other forms of discrimination and marginalisation), on the other, it promoted what Michael Omi and Howard Winant (Reference Omi and Winant1994) call a form of ‘racial common sense’ that denied any racial inequality under the pretext of the supposedly homogeneously white and European character of the nation.

Although the pressure exerted on non-white people to accept their subaltern social position and forget their ethno-racial markers was intense, it is important not to assume that they had no agency at all. On the contrary, those who suffered from structural racism and the whitening mandate developed various forms of resistance. Sometimes this involved distancing themselves from ethno-racial identities to embrace other forms of identification (political, territorial or class) in order to improve their life chances and deal with a profoundly unjust social order. A head-on challenge against racism was not always possible, but these people continued in multiple ways to show the limits of Argentine whiteness as a project. In the 1930s, in the context of large migrations of peasants (mostly mestizos) to Buenos Aires and other central cities, these tensions became more acute – and especially with the coming to power of Peronism in the 1940s, which we will discuss later, and as the working classes became politically vocal.

Sergio Caggiano (Reference Caggiano2012) points out that the ‘visual common sense’ in Argentina trains the eye not to read as ‘racial’ differences in phenotype that are nevertheless clearly evident. As Alejandro Frigerio (Reference Frigerio2006) shows, only people with stereotypically and very pronounced African features are perceived as Afro-descendants in Argentina. Similarly, outside of rural or community settings, Indigenous people are often thought of simply as criollos. This explains, in part, the fact that the idea of a uniformly white and European country has coexisted with a demographic reality that, in the public arena and in daily interaction, constantly contradicts it, given the ethnic-racial heterogeneity of the population. But this ‘not seeing’ (what Caggiano calls ‘invisualisation’) is neither systematic nor constant: in certain contexts, differences in skin colour can quickly become very noticeable. A middle- or upper-class white person is likely to immediately notice the phenotype of someone they pass on a deserted street at night if they have a dark complexion. And, while this does not mean that he or she will encode that difference in terms of defined ethno-racial identities (white, Afro-descendant, Indigenous, etc.), this illustrates how phenotypic difference influences forms of social stratification and classification in Argentina, despite the constant affirmation that all Argentines are white and European.

This example also shows how fear and other negative affects can be mobilised by racial factors. In fact, the notion of a ‘civilisation’ besieged and sometimes invaded by ‘barbarism’ has been a constant trope in Argentine history, which has been deployed by the dominant sectors to interpret different political and class conflicts and conjunctures. And although these notions have changed over time, they have generally had racialised underpinnings (Gordillo Reference Gordillo2020). Thus the usual invisibility of racial diversity in dominant discourses has been punctuated by momentary hypervisibilisations of such differences, which activate visceral anxieties and fears and provide affective bases to justify repressive and/or reactionary political projects. As we shall see, the racialisation of Peronist sympathisers in the 1940s or, more recently, the alarm over a nonexistent ‘terrorist’ organisation of the Mapuche people in Patagonia are examples of this.

But beyond these moments of hypervisibilisation, whitening discourses have mean that racial difference is alluded to through other markers of difference, such as education, geographic origin and, above all, social class. In fact, the term negro in Argentina is used generically to refer to poor people (of whatever skin colour and ethnic origin, even if they are phenotypically white). In the colloquial language of Argentines, negro is used to talk about the poor much more frequently than to refer to people of African descent; it generally has a primarily classist, rather than racial, connotation. The term refers to what Lea Geler (Reference Geler2016) calls el negro popular (a Black person of the working classes) and Ezekiel Adamovsky (Reference Adamovsky2012) calls the ‘non-diasporic black’, to differentiate it from an Afro-descendant.Footnote 4 At the same time, although not always the case, the implicit stereotype that a poor person will have brown skin often works in practice. Class and race are intertwined.Footnote 5

Efforts to impose the idea of a white and European nation were quite successful in terms of public acceptance of the image, but this did not prevent what elites were trying to exclude – mestizo, Indigenous, brown and the Afro-descendant people and elements – from finding forms of expression outside dominant structures and discourses, and sometimes even within them. In the arts, the figure of the gaucho – typified as a brave, unruly, nomadic cowboy, often brown-skinned – is emblematic of this process, as we will show. The cultural sphere constituted a space of struggle in which some of the most fundamental criticisms of the idea of Argentina as a white and European nation took place. In this chapter we outline the relationship between the arts and the struggle against racism in Argentine history, with a focus on specific relevant examples. We will examine various anti-racist artistic experiences and the tensions (and sometimes hybridisations) they have had with a high culture that thought of itself, originally, in European terms, but that could never escape its relationship with the non-white (partly for reasons of guilty fascination).

Our account will include anti-racist artistic expressions articulated around racial subjectivities with a specific ethnic memory – particularly Afro-descendant and Indigenous – but it will go beyond that. This is due to the fact that, precisely because of the characteristics of Argentina’s racial formation and the power of the myth of the white and European nation, Afro-descendant and Indigenous artistic expressions have been less prominent than in other Latin American countries, for example Brazil and Colombia. But, on the other hand – and here it is possible to point out a specific characteristic of the Argentine case – the artistic production of working-class sectors has played a central role in the articulation of strategies that, despite not being explicitly anti-racist, have strongly contributed to challenging structural racism. Either directly or through the mediation of middle-class – or even upper-class – artists, the working-class or ‘non-diasporic’ negros mentioned here managed to have a considerable impact in formulating alternative ways of thinking about the nation and to reinstate the presence and value of non-white people as part of it.

In order to deal with the diversity of materials, we propose a typology in terms of how they position themselves in the face of racism, comprising three categories: visibilising, vindicatory and anti-racist.Footnote 6 The visibilising category includes practices that grant artistic presence to ethnic-racial groups that are invisible in the narratives of the nation, although they may do so with stereotypical, exoticising or inferiorising images (e.g. that infantilise or bestialise). In this sense, they cannot be considered anti-racist and, in fact, may contribute to racism. However, in the Argentine context, they take on a different weight due to the centrality of discourses that minimise the very existence of racial diversity. Vindicatory artistic practices present favourable images that contest the mostly negative valuation that Argentine society attributes to subaltern ethnic-racial identities, without fundamentally questioning racism or only doing so obliquely. These vindicatory cultural productions can be related to what Mónica Moreno Figueroa and Peter Wade (Reference Moreno Figueroa and Wade2022) call ‘alternative grammars of anti-racism’ – that is, those dynamics that do not explicitly focus on racism or anti-racism, but that address broader structural inequalities in which the role of racial difference is indirectly acknowledged. Not all vindicatory artistic practices are produced by non-white artists but, in the cases in which this happens, the affirmation generated by self-representation takes on a specific gravitational weight, as it implies taking control of symbolic and political representation and, ultimately, of subjectivity (Fanon Reference Fanon1986). Finally, anti-racist discourses stricto sensu denounce, with varying degrees of regularity and explicitness, the racism suffered by subaltern ethnic-racial groups.

Most of the anti-racist artistic practices stricto sensu have developed in recent years as a result of the impact of multiculturalism in Argentina. However, it is also important to consider the role that vindicatory cultural products have played in the national imaginary. A good part of the struggle against racism in Argentina has been expressed less as a head-on challenge than as a heterogeneous set of rather oblique, denotative, implicit initiatives that have revalued brownness, and its associated cultural forms and ways of life, and undermined the idea of a white and European nation (and therefore, the superiority of whiteness) without attacking it explicitly. Many of these initiatives were led by people – be they professional artists or just ordinary people expressing themselves artistically – who did not necessarily subscribe to any specific racial or ethnic identity, nor did they have distinctive ethnic memories or even a physical appearance that would make them victims of possible racist aggression. Rather than projecting our own expectations about what form anti-racist cultural expressions should take, we will attend instead to the ways in which the people who create cultural products relate to racism.

The Construction of the Nation-State

The beginning of Argentina’s independence process in 1810, and its formal declaration of independence in 1816, brought drastic changes in interethnic relations. In 1813 the so-called caste systemFootnote 7 was abolished, and an 1821 electoral law of the province of Buenos Aires – soon imitated by almost all provinces – established the right of suffrage for any free male, of whatever colour, social status or even literacy. For the free male population – which included a large number of Afro-descendants and Indigenous people living in white-controlled cities – this meant a horizon of equality before the law that was quite radical for the time. Racial discrimination continued, but no longer on a formal or legal basis. Those who had been enslaved had to wait much longer. In 1813, a ‘free womb’ law was decreed and there were later prohibitions on the slave trade, but the abolition of slavery would come only in 1853 (or 1860 for the province of Buenos Aires).Footnote 8 Moreover, the emergent state controlled only half of Argentina’s current territory during that time. Parts of the Pampas and the Chaco, and the entirety of Patagonia, were under the control of independent Indigenous communities, with whom the Argentine state maintained ties but on whom it also periodically visited military violence.

The triumph of the Buenos Aires liberals over the interior provinces in 1862, after decades of internal conflict over how to organise the new nation, was preceded and accompanied by strongly racist narratives and discourses, including in literature and essays, where Afro-descendants, Indigenous people and mestizos were demonised. Paradigmatic examples of this are ‘El matadero’ (The Slaughterhouse, 1838, published in 1871) by Esteban Echeverría and Amalia (1851) by José Mármol, widely considered in Argentina, respectively, to be the first national short story and novel. La cautiva (The Captive, 1837), an epic poem by Echeverría, recounted the capture of a white woman and her husband by Patagonian Indigenous people, symbols of the perceived threats to white society (Malosetti Costa Reference Malosetti Costa2022). In 1845, Domingo F. Sarmiento published his book Facundo, of enormous influence in Argentina and the rest of Latin America, in which he read the political conflicts and development possibilities of the time as an ongoing struggle between ‘civilisation’ and ‘barbarism’. In this view, the former was rooted, in part, in whiteness and Europeanness, while the latter flourished in the rural world of the gauchos and the Indigenous and mestizo lower classes.

From 1879 onwards, the national army quickly and violently occupied the territories of the Pampa and Patagonia (and eventually the Chaco in the northeast) that had been under the control of Indigenous peoples. This was part of a process of consolidation and modernisation of the state and the Argentine economy, which sought to insert itself definitively into the international system as an exporter of raw materials for industrialised countries, particularly the United Kingdom. With the rapid urbanisation of the Pampa region and the mass arrival of immigrants in the following decades, the advance of the project that the elites called ‘progress’ or ‘civilisation’ seemed assured. The narratives of Argentine modernisation that flourished at this time presented Indigenous cultures and the African presence (and soon also the gaucho world) as things of the past, of which only fast-disappearing relics remained. At the end of the century, the idea of a completely white and European nation seemed at first sight convincing.

At the intellectual, literary or academic art level, for the time being, there was little possibility of opposing the racism of official discourse or the idea of a white and European Argentina, which was in fact partly promoted in official cultural production. Between the 1850s and 1880s, on the other hand, the Afro-descendant community of Buenos Aires (known as afroporteños) maintained an appreciable presence in the public sphere, including via several newspapers of their own in which they defended themselves against racial prejudice. There were also Black poets, such as Horacio Mendizábal, Mateo Elejalde and Casildo Thompson, who published explicitly anti-racist works. After this period, however, due to the pressure for acculturation coming from the dominant sectors (and from part of the Afro-descendant community that sought integration into the national project), the Afroporteño community entered a long period of invisibility in the public domain (Geler Reference Geler2010; Lewis Reference Lewis1996).

In this period, Indigenous cultural production began to be classified within the incipient ethnographic collections of the Museo de la Plata and the Museo Etnográfico de Buenos Aires, both recently founded (Podgorny Reference Podgorny1999). These collections followed the criteria of European rescue anthropology that sought to generate archives of ‘cultures’ supposedly in imminent disappearance. They were organised by region and did not record the authorship of the objects collected. The collections were supplemented by raciological studies of Indigenous people who were taken prisoner in the military outposts and kept in captivity in the La Plata Museum (where many died), and by the examination of Indigenous skeletal remains exhumed without consent.

In popular culture at the turn of the century, especially in the cities, there were extraordinarily vivacious expressions of the heterogeneity of the lower classes, where immigrants from many nations, internal migrants, criollos, Indigenous people, mestizos and Afro-descendants coexisted. Although they did not have an explicit anti-racist message, unique cultural expressions emerged that highlighted ethnic diversity. Examples of this are carnival and tango (which at the time showed their African roots more clearly than would later be the case): they both reaffirmed the presence of the non-white as part of the nation and subtly undermined the official whitening messages.

In turn, the enormous success of José Hernández’s poem Martín Fierro, published as a cheap pamphlet in 1872, deeply marked Argentine culture, especially among the lower classes. This particular type of popular criollismo, produced mainly by white upper- and middle-class letrados (men of letters) but aimed at lower-class audiences, turned the gaucho – precisely the figure that official discourses had considered as belonging to the barbaric past – into a hero of the people and an emblem of the nation. The phenomenon points to a distinctive tension in Argentine cultural identity: even as official discourse promoted a white, European ideal, there persisted a widespread desire, cutting across social classes, for cultural authenticity rooted in more autochthonous traditions. For the working classes, criollismo provided a means to assert their presence in national culture. For white elites and middle classes, it offered a way to claim cultural legitimacy and connection to an imagined authentic national past, while maintaining their social position. This complex dynamic helps explain how criollismo could become a powerful national emblem while simultaneously challenging aspects of official racial narratives. In popular criollismo culture, the gaucho hero was frequently portrayed as a dark-skinned, often mestizo, individual who associated with Indigenous and Afro-descendant people and coexisted with them as part of the same criollo world that these stories exalted (Adamovsky Reference Adamovsky2019). And it is not a minor fact that some of the most famous creators in the criollo genre – such as Gabino Ezeiza, who was a famous criollo payador (wandering minstrel) – were themselves of African descent.

From the Centennial to the First Mass Culture (1910–1943)

Between 1880 and 1914, just over four million people, mostly Europeans, arrived in Argentina, of whom 70–75 per cent stayed permanently (Adamovsky Reference Adamovsky2020; Brown Reference Brown2011). The narrative of Argentina as a white and European country relied on the role that the enormous overseas immigration would have in ‘dissolving’ all remnants of the non-white population. But the elites expected migrants from northern Europe, home to the ‘race’ that was supposed to lead the world’s march towards progress. Those who arrived, instead, were mostly Italians and Spaniards of humble origin and, in many cases, with anarchist or socialist leanings.

The need to assert dominance over these foreign-born masses and to reaffirm the social order in the face of revolutionary ideas drove an intellectual movement of a nationalist bent that became more prominent after 1910, drawing on celebrations for the Centenary of the May Revolution. In this context, three voices stood out. Manuel Gálvez reaffirmed the Spanish and Catholic heritage of the cultural traditions of pre-immigration Argentina. Leopoldo Lugones promoted a cult of nationality centred on the gaucho, who as we have seen was already admired by the lower classes. But the gaucho he claimed was a mythical, almost Greco-Latin gaucho, who epitomised the supposedly superior values (nobility, patriotism, virility) that characterised, in his opinion, Argentina’s national type prior to immigration (Adamovsky Reference Adamovsky2019). Finally, Ricardo Rojas did criticise the idea of white and European Argentina by advocating for a mestizo national tradition that combined the European with the Indigenous, although he conceived of the latter as a spiritual legacy and an aesthetic substratum of Argentineness, rather than as a biological contribution to contemporary Argentines. However, none of these three authors was interested in recovering the Afro cultural legacy. These intellectuals, part of a trend known in Argentine intellectual history as ‘cultural nationalism’, opened a new scenario of revalorisation of the local vis-à-vis the European; but this did not mean the end of racist prejudices, which remained very present.

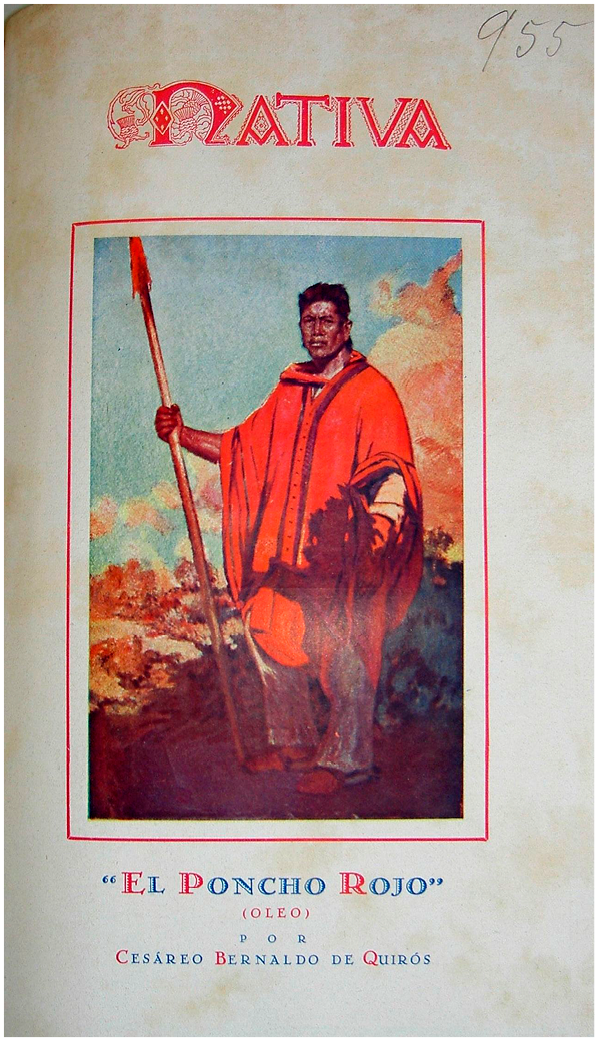

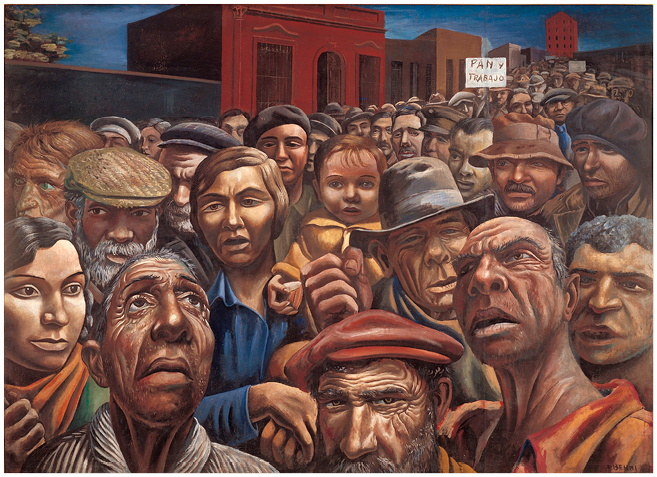

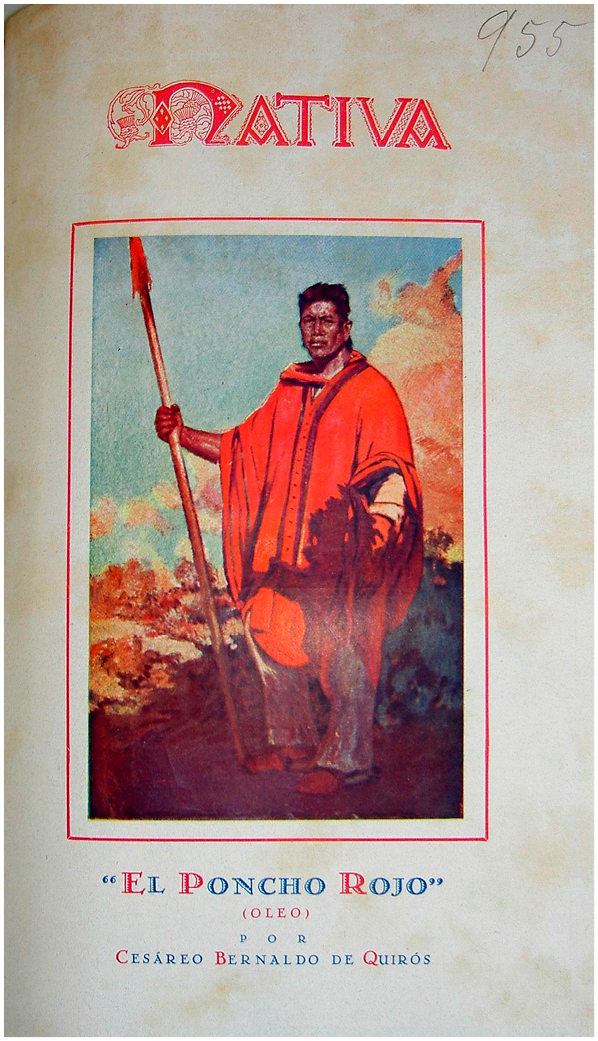

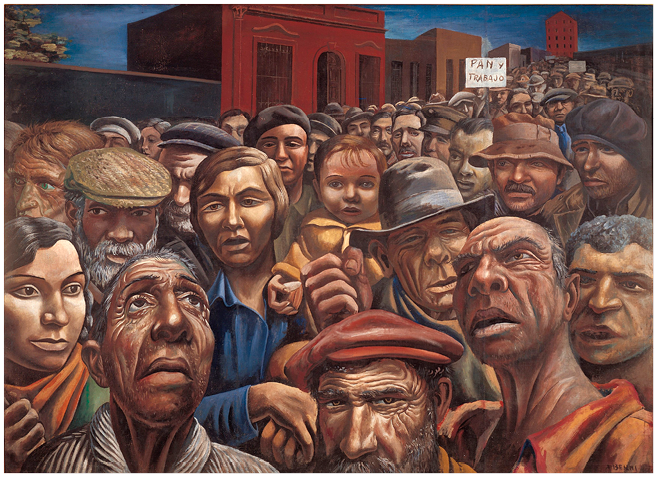

Despite its limitations, this debate paved the way for other, more profound challenges. The impact of the ideas of writers such as Rojas and Lugones was felt by visual artists, who from the 1920s onwards chose to paint Indigenous or mestizo characters set in scenes from the interior of the country and also gauchos and criollos from the Pampa region, in whom mestizo features or brownish skins could often be distinguished (Penhos Reference Penhos, Penhos and Wechsler1999). Cesáreo Bernaldo de Quirós stands out in this sense (see Figure 3.1). Also influenced by leftist ideas and anti-imperialism, Antonio Berni represented the Argentine working people as having racially diverse bodies (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.1 El lancero colorado/El poncho rojo by Cesáreo B. de Quirós, 1923, from the cover of Nativa, a nationalist magazine

Figure 3.2 Manifestación, painting by Antonio Berni, 1934

During this period, wherein Argentina exhibited a pace of modernisation and urbanisation exceeding the Latin American average, popular culture and mass culture (produced by middle-class creators but aimed at various audiences) contributed to rendering the heterogeneity of the nation visible. Popular criollismo deepened the connection which it had been making between the gaucho and non-whiteness. Although many of these images and representations relied problematically on stereotyped images (such as the famous illustrations of gauchos by the artist Florencio Molina Campos), they contributed to making diversity visible and, consequently, implicitly questioned the idea that the Argentine people were white and European. In the first decades of the twentieth century, two of the most famous Argentine comic strips emerged, both with non-white protagonists: Las aventuras del Negro Raúl (1916, by Arturo Lanteri), inspired by the Afro-descendant dandy Raúl Grigera, and Patoruzú (1928, by Dante Quinterno), about a Tehuelche Indigenous man of great fortune and superhuman strength (Alberto Reference Alberto2022; McAleer Reference McAleer2018). Although both reproduced grotesque images of Black and Indigenous people (both characters were presented as unintelligent), in Patoruzú this was combined with admirable characteristics such as heroism and altruism.

The only explicitly anti-racist approach in the arts at that time came from Martín Castro, an anarchist criollo payador, who in 1928 wrote a long gaucho narrative poem entitled Los gringos del país (The Country’s Gringos), published shortly after as part of the collections of cheap booklets of gaucho adventures made available for popular consumption. The poem was a veritable counter-history of Argentina, told from the point of view of the Indigenous people, dispossessed and oppressed by Europeans and their descendants for 400 years. The gauchos that Castro exalted were of trigueño complexion (literally, wheat-coloured, i.e. brown) and direct descendants of both Indigenous people and the ‘white’ Argentines in turn descended from Europeans, who were their enemies (Adamovsky Reference Adamovsky2019).

Also in the 1920s, the folk music of the northwest region acquired the status of a commercial genre and by the following decade there was already an established circuit of artists. The lyrics of some of its songs, especially those of Atahualpa Yupanqui and Buenaventura Luna, reinstated in the national imaginary the presence of mestizo and Indigenous populations. For musicians, having native lineage and brownish complexion even functioned as a mark of authenticity (Chamosa Reference Chamosa2010; Adamovsky Reference Adamovsky2019). In the 1930s and the beginning of the following decade, moreover, people in the world of tango recovered memories about the music’s Afro-descendant roots (made invisible in the previous years), while two Afro rhythms from the Rio de la Plata region were revalidated: milonga and candombe. Although less prominent, local jazz also gave rise to a revalorisation of Blackness. The world-renowned guitarist Oscar Alemán, who had a very dark complexion and presented himself as Afro-descendant, shone in this period (Karush Reference Karush, Alberto and Elena2016).

Thus, by the early 1940s, state and school messages, which affirmed that the nation was white and European, coexisted in tension with a powerful popular and mass culture, which produced images of the Argentine that reinstated the presence of non-whiteness and, at times, affectively revalued it. The fact that these cultural productions were largely created by members of the same middle class who, from other places, simultaneously promoted the image of a white Argentina, explains why the clash of visions remained latent. With the partial exception of Martín Castro, Argentine racism was not yet openly discussed by cultural creators, nor was the idea that the nation was or should aspire to be ‘white’ challenged head-on.

Peronism and the Emergence of the cabecita negra (1943–1955)

The emergence of Peronism in the mid 1940s caused an upheaval in the idea of Argentina as an extension of Europe. As a political movement, it served to unify and articulate different sectors of the population, including both white people of European descent and others of mestizo or even Indigenous descent. The latter were, in general, provincial migrants who, attracted by job opportunities in the cities from the 1930s onwards, had progressively settled in the urban peripheries, particularly in Buenos Aires (Ratier Reference Ratier1971). Although workers of all aspects and ethnic origins supported Juan Perón, it was the provincial migrants who became metonymic signifiers of the entire Peronist movement and the urban proletariat (Grimson Reference Grimson2017).

Faced with the growing unity and voice of the working classes, a powerful anti-Peronist movement was formed almost immediately among the middle and affluent sectors. They now had to share public spaces with dark-skinned internal migrants, who were derogatorily called cabecitas negras (little black heads), and who now ventured beyond the periphery and into traditionally white areas of the city. Among the white and European middle and upper classes, this produced affective reactions and intensities that were channelled into emotions of different kinds – in particular, fear and disgust – and that nourished moral and political discourses. The anti-Peronists aimed from the beginning to discredit their adversaries not only in political terms but also morally, aesthetically and racially. They branded their enemies as vulgar, dirty, irrational and unable to adapt to the conventions of urban modernity. But these differences were also essentialised and racialised: Peronists were also attacked using racial categories such as mestizo, negro and indio; they were accused of being ‘hard haired’ (i.e. with African-type hair) and, especially, of being cabecitas negras. Thus, from its genesis, anti-Peronism was not only structured around ideological issues but also had an affective substratum articulated around racial issues.

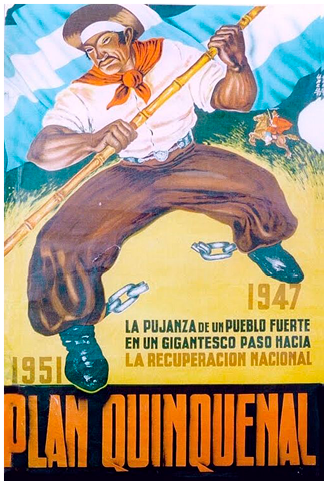

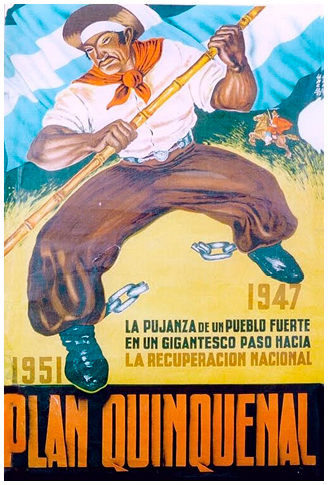

Peronism, meanwhile, remained strictly within a discourse of class and did not respond explicitly in the terms in which the opposition framed the discussion. Its rhetoric was expressed in a class language that posed the conflict as a struggle between the working people – without distinction of race – and the oligarchy (Garguin Reference Garguin2007; Milanesio Reference Milanesio, Karush and Chamosa2010). The problem of differences in skin colour was not a topic for Peronists, nor was there an explicit vindication of the brown-skinned Argentine. In fact, where racism was mentioned, it was rather to deny that it existed in Argentina. The denunciation of Argentine racism, the vindication of the cabecita negra and its transformation into an icon of Peronism and the deep roots of the nation would take place only after the overthrow of Perón in 1955 (Adamovsky Reference Adamovsky2019). As in previous periods, the idea of a white and European Argentina was discussed implicitly and indirectly in the sphere of mass culture and through a language of visuality and aurality. Although the propaganda apparatus of the Peronist state continued to represent the Argentine people through European-looking bodies, a greater presence of images that featured mestizos was evident in these years (Adamovsky Reference Adamovsky, Alberto and Elena2016). One example is the use of the mestizo figure ‘Juan Pueblo’ in a poster promoting Perón’s Five Year Plan (1947–1951) to modernise and industrialise the country (see Figure 3.3; the text reads ‘The vigour of a strong people is a giant step towards national recovery’).

Figure 3.3 A mestizo ‘Juan Pueblo’ in a promotional poster for the Five Year Plan, El Laborista, 10 June 1947, p. 8

Figure 3.3 long description.

Figure 3.3Long description

The man wears gaucho garb of bombachos or baggy trousers, a shirt, a pañuelo or silk scarf tied at the neck, a broad-brimmed hat and boots. The man has the remnants of a broken chain attached to each ankle. The text on the poster reads: The power of a strong people taking a gigantic step towards national recovery. 1947–1951, Five Year Plan.

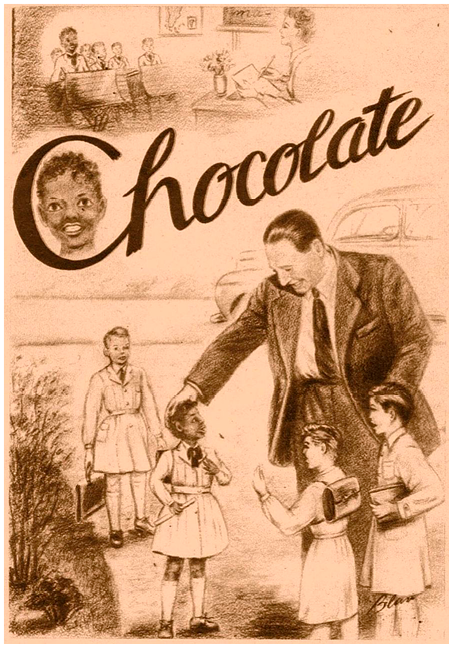

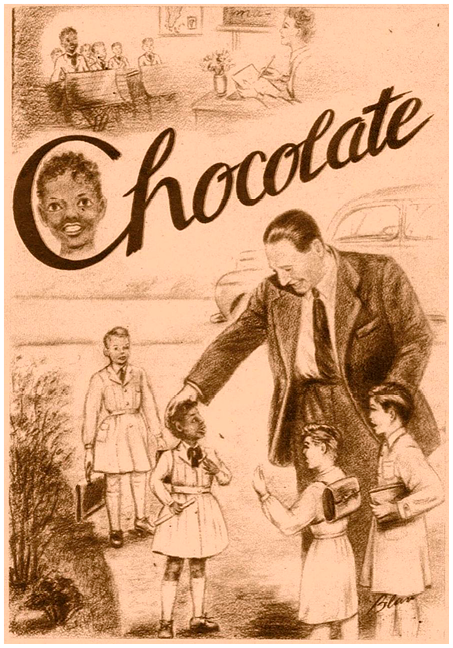

The representation of Black Argentines was much rarer, though notable examples exist. One such case shows Perón with an Afro-Argentine child in an illustration for a story titled ‘Chocolate’, about an Afro-Argentine boy who was bullied at school, published in the regime’s main propaganda magazine, Mundo Peronista (Peronist World) (see Figure 3.4). While this image could be interpreted as patronising and its title problematic, it nevertheless challenges local racism: the white state school uniform, the company of other (white) boys and Perón’s affection acknowledge the Black child as part of the nation at a time when dominant discourses denied the existence of Afro-Argentines.

Figure 3.4 Juan Perón with an Afro-Argentine child, illustration from Mundo Peronista 84, 15 April 1955, p. 32

Figure 3.4 long description.

Figure 3.4Long description

The page is divided by the title word Chocolate, which includes the face of the eponymous Afro-descendant child within the capital C. Above the title, a schoolroom scene shows one Afro-descendant boy among his Euro-descendant peers, facing a Euro-descendant teacher. Below the title, in an exterior scene with a car in the background, Perón interacts with four schoolchildren, including the boy Chocolate, the protagonist of the story for which the image is an illustration.

As before, popular criollismo continued to channel these debates. The same happened with music of mass consumption. To give just one example, the biggest hit record in Argentine history was a 1950 song, ‘El rancho’e la Cambicha’ (Cambicha’s House), performed by Antonio Tormo, strongly identified with the Peronist regime (Chamosa Reference Chamosa2010). The lyrics describe in the first person the preparations of a man who is about to go to a rural boliche (popular dance) run by a woman known as Cambicha. Without being expressly anti-racist, its celebration of popular festivities and of the positive affects related to the enjoyment of music and dance, conflicts, albeit indirectly, with the ideal of the white, European people. The lyrics contain words in Indigenous languages: cambicha, in fact, is the feminine diminutive of cambá, which in Guaraní designates people with dark or black skin.

While there were allusive and indirect ways of thematising ethnic-racial differences, during these years there was no specific militancy along these lines. Afro-Argentines did not have a public voice, as they had had in the nineteenth century, although they did have private spaces in which they maintained their own cultural practices, such as the dances of the Shimmy Club of Buenos Aires, which operated from the 1920s to the 1970s (Frigerio Reference Frigerio and Lechini2008). A development worth noting is that in 1946 the Kolla Indigenous people achieved unprecedented visibility in the national press when they organised the so-called Malón de la Paz (Peace Raid), a march on foot from Jujuy to Buenos Aires to reclaim their ancestral lands. It was the starting point of an indigenist movement in the country, which developed more strongly in the 1970s (Lenton Reference Lenton, Karush and Chamosa2010).

Conservative Reaction and Political Radicalisation (1955–1976)

In 1955, a coup d’état deposed the government of Perón, who went into exile until 1973. During this period, in which the Peronist Party was banned, military regimes alternated with civilian governments of weak legitimacy. The overthrow of Perón constituted an anti-plebeian reaction that sought to defuse the capacity for action of the working class and, given the veiled racial substratum of the political conflict, to restore the pre-eminence of what was seen as the true Argentina, rooted in middle-classness and Europeanness. In a scenario that combined the proscription of Peronism and the continuation of racism, the first explicit public debate on skin-colour discrimination in Argentina took place (racism had been openly discussed before, but only in reference to Jews). In the 1950s, authors such as Jorge Abelardo Ramos and Arturo Jauretche wrote widely circulated essays linking the anti-Peronist reaction to the interests of the oligarchy, to imperialism and to the racist views which, according to them, were held by a substantial part of the middle class. In the 1960s, authors of the ‘new left’ such as Juan José Sebreli also took up the topic of the oblique racism of those who identified themselves as being middle-class and of European descent. Reversing the negative charge that it had had among the anti-Peronists, sectors of Peronism now vindicated the idea of cabecitas negras as an emblem of plebeian Argentina and authentic nationality. The fact that Peronism was the party of the cabecitas negras was now proof of the popular roots that the party proudly claimed. To this scenario was added the transnational influence of the decolonisation process in Asia and Africa, the civil struggles of African Americans and, particularly, the proliferation of left-wing anti-imperialist movements in Latin America inspired by the success of the Cuban revolution. All of this gave greater resonance to the anti-racist struggle and projected the vindication of Black and Indigenous America.

In the arts, the affirmation of the non-white Argentina had numerous examples, of which we can mention only a handful. The well-known short story ‘Cabecita negra’ (1961) by Germán Rozenmacher, a writer of Peronist leanings, describes, from the perspective of a racist white, middle-class character named Lanari, the paranoid fears of the Buenos Aires petite bourgeoisie regarding immigrants from the interior. The story narrates, from Lanari’s point of view, an ambiguous and tense situation the protagonist experiences when two people he perceives as cabecitas negras momentarily occupy his apartment. The end of the story, in which Lanari is convinced of the need to use the army to ‘crush’ all the cabecitas negras and negros, anticipates the Argentine bourgeoisie’s support for the militaristic and repressive tactics used by the state in dealing with the working classes in the 1970s; it makes visible the role of racism as the affective basis of that coercive turn.

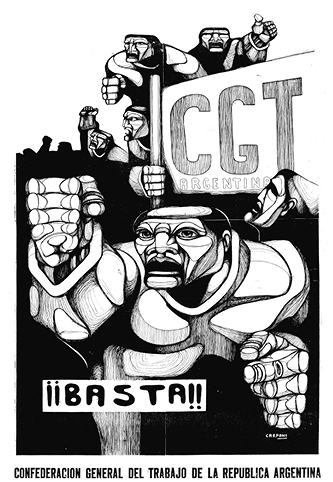

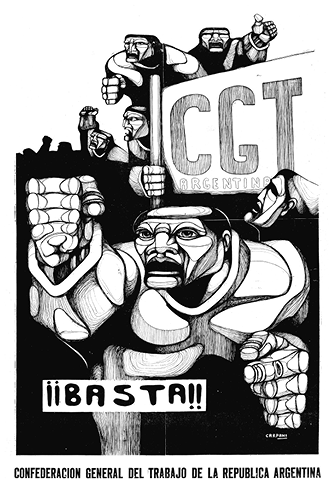

In the visual arts the most obvious example is the work of Ricardo Carpani, who devoted much of his work to the illustration of political pamphlets and posters that supported working-class causes. The bodies he chose to represent the Argentine people deliberately showed non-European features (see Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5 ¡¡Basta!! poster by Ricardo Carpani, 1963

Cinema also raised the issue of racism as an integral part of the narratives of Latin American emancipation of the time. For example, the pinnacle of Latin American political documentary, Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino’s La hora de los hornos (1968, The Hour of the Furnaces), denounces the structural racism suffered by native populations and chooses to show non-white bodies (and a soundtrack that includes Afro-derived rhythms) to represent the oppressed Latin American population. However, it relapses into patronising views of Indigenous people as backward, apolitical and in need of guidance and leadership from urban revolutionaries, reproducing some of the paternalistic attitudes it seeks to criticise.

Finally, popular music was rich in evocations of non-whiteness as part of the nation. In particular, folkloric music – which during this period achieved an unprecedented popularity – affirmed Indigenous legacies and the connection of things Argentine with the cultural spaces of mestizo Latin America. While songs often relied on problematic indigenist tropes that romanticised Indigenous people as noble savages or relegated them to a mythical past, they nevertheless helped challenge the idea of Argentina as exclusively white and European. The repertoires of singers Mercedes ‘La Negra’ Sosa and Daniel Toro are good examples.

In the early 1970s, the fervour of the working classes also reached Indigenous peoples, who started initiatives to coordinate the struggles of different peoples. Afro-Argentines, on the other hand, continued to have no public voice as such. The lower classes mobilised as never before, but there was no activism specifically focused on anti-racism in these years. However, as we have seen, cultural, trade union, social and political militancy did not completely avoid the issue.

Dictatorship, Neoliberalism and Democracy (1976–2003)

The military dictatorship that was installed after the 1976 coup d’état and remained until 1983 sought the total dismemberment of the working classes as political actors through a programme of terror and political repression, economic disciplining and the weakening of social ties and other notions of solidarity. It also attempted to reaffirm a vision of national identity anchored in whiteness and European origins. The repression dismantled incipient Indigenous efforts at coordination and also affected the cultural sphere. Many artists were murdered, disappeared, exiled or forced to keep a low profile to avoid reprisals. Among those mentioned here, Ricardo Carpani, Mercedes Sosa, Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino went into exile; Daniel Toro remained in the country, but his songs were banned.

The return of democracy in 1983, together with the impact of discourses of multiculturalism sponsored by international organisations, opened up new opportunities for Indigenous communities, which in the 1980s reorganised and presented claims in terms of human rights, in line with the international prominence such rights had acquired during the brutal military regime (Briones, Cañuqueo, Kropff and Leuman Reference Briones, Cañuqueo, Kropff and Leuman2007). Together with historical demands for ancestral land, this implied a greater emphasis on issues of ethnicity, identity and recognition, which was often expressed at the cultural level. Communities everywhere began to recover their languages, music and traditions. The Mapuche singer Aimé Painé was one of the most outstanding voices in this regard. Although she never managed to record an album, she performed in the country and abroad, working tirelessly as an artist and activist to make Mapuche people aware of their own history and culture and to make them visible among other non-white groups (Navarro Hartmann Reference Navarro Hartmann2015). The demands of native peoples attracted the attention of white artists. For example, Argentine cinema dedicated many films to Indigenous peoples during this period, among which stand out Gerónima (directed by Raúl Alberto Tosso, 1986) with the Mapuche actress Luisa Calcumil in the leading role, La deuda interna (The Internal Debt, directed by Miguel Pereira, 1988) and El largo viaje de Nahuel Pan (Nahuel Pan’s Long Journey, directed by Jorge Zuhair Jury, 1995). Only in the twenty-first century did an incipient movement of cinema made by Indigenous peoples themselves emerge, generated by their participation in training workshops for young communicators (Torres Agüero Reference Torres Agüero2013) and inspired by the boom in Indigenous audiovisual production in the rest of Latin America (Schiwy Reference Schiwy2009; Córdoba Reference Córdoba2011; Soler Reference Soler2017).

The first post-dictatorship government (under Raúl Alfonsín, 1983–1989) ended in hyperinflation and a deep economic crisis. His successor, the Peronist Carlos Menem, who governed until 1999, implemented one of the most drastic neoliberal adjustment programmes in the world, which raised poverty and unemployment levels to record highs and provoked a crisis of representation. The weakening of the state’s integrative capacity opened the door to a profound questioning of the myth of white and European Argentina and the emergence of alternative identities. The drastic impoverishment experienced by the middle sectors (supposedly ‘white and European’ people) during the 1990s – and intensified by an extreme economic crisis in 2001 – caused increasing anxieties. Rooted in the persistent affective substratum of racism in Argentina, these fears were often expressed through racial language and were codified in terms of a symbolic ‘darkening’ of the nation, given the historical association of mestizo, Indigenous and Afro elements with poverty (Aguiló Reference Aguiló2018). As Alejandro Frigerio (Reference Frigerio2006) demonstrates, references to the ‘Latin Americanisation’ and even the ‘Africanisation’ of Argentina were common in political and media discourse during the 2001 crisis. At the same time, the crisis led to Argentine racism being discussed more frequently in the media.

In the 1990s there was a marked process of re-ethnicisation, which included the reappearance of native groups such as the Rankulches, Huarpes or Selk’nam, which had been declared extinct (Gordillo and Hirsch Reference Gordillo and Hirsch2010). The 1994 reform of the National Constitution included, for the first time, the recognition of the pre-existence of native peoples in Argentina before colonisation, adding to international recognition (such as International Labour Organization treaty 169), and advancing on the provincial recognition that had been achieved in some regions (Carrasco Reference Carrasco2000; Briones Reference Briones2005). In 1995, the Instituto Nacional contra la Discriminación, la Xenofobia y el Racismo (National Institute Against Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism, INADI), was created with the principal objective of receiving complaints about discrimination and prosecuting citizens accused of acts of discrimination or hatred. Although both Indigenous recognition and the creation of INADI were propitiated by international contexts of expansion of multiculturalist policies as new forms of international governance (see Briones Reference Briones2005; Hale Reference Hale2005), these movements would have been impossible without the pressures of national organisations and activisms (Lenton Reference Lenton, Karush and Chamosa2010). At this time, associations of Afro-Argentines also began to reappear, aiming to make their presence visible and revalue their cultural legacy (Frigerio, Lamborghini and de Maffia Reference Frigerio, Lamborghini and de Maffia2011).

In popular culture, from the 1990s onwards, there was also an increase in the reaffirmation of native peoples, although mostly by non-Indigenous people. This was most noticeable in music. The fifth centenary of Columbus’s arrival prompted critical commemorative songs by two of the most important names in national rock, León Gieco and Los Fabulosos Cadillacs: respectively ‘Cinco siglos igual’ (Five Centuries Without Change) and ‘Quinto centenario’ (Fifth Centenary). Other rock bands produced similar content at the time, such as A.N.I.M.A.L. (acronym for Acosados Nuestros Indios Murieron Al Luchar, Our Indians Died Fighting), Almafuerte, La Renga and Malón. In the realm of folk music, the Mapuche singer Rubén Patagonia stands out. However, with the exception of Patagonia, none of these musicians identified as Indigenous, and most of their mentions of native peoples reinforced the idea of Indigenous peoples as located in the past.

The band Todos Tus Muertos, led by the Afro-descendant and Rastafarian Fidel Nadal – son of Enrique Nadal, a film director and early leader in the fight for the recognition of Afro-Argentines – had great commercial success with Dale aborígen (Go, Aborigine, 1994), an album that mixed Afro-Latin rhythms with rap, punk, reggae and ska. The album included several denunciations of racism, although focused on international figures such as the Zapatistas, Malcom X, Patrice Lumumba and Nelson Mandela.

In cuarteto music – a popular music from the province of Córdoba – Carlos ‘La Mona’ Jiménez, the genre’s top star and, aside from Nadal, the only artist among those we mention in this section who has a phenotype read by many Argentinians as Afro-descendant, praised the ‘skin of my race, Black race’ in his highly successful album Raza Negra (1994). In another of his compositions, ‘Por portación de rostro’ (2006, Because of the Face, i.e. racial profiling), he also alluded to the racism suffered by those with ‘dark skin’. The fact that Jiménez is considered an icon of the negro popular indicates that, despite their being usually differentiated, sometimes there is room for overlapping between plebeian Blackness and ethnic Afro identity.

The most pointed anti-racist approaches in the musical realm of this period were seen in so-called cumbia villera, in which also, for the first time in the twentieth century, signs appeared of ‘Blackness’ becoming an emblem of defiant pride among the working class. Cumbia villera is a subgenre of cumbia created by musicians coming from low-income and precarious neighbourhoods, called villas in Argentina (Cragnolini Reference Cragnolini2006; Semán and Vila Reference Semán and Vila2011, Reference Semán and Vila2012).Footnote 9 It became an unexpected success in the late 1990s and early 2000s, with lyrics that often narrated, in the first person, the alleged daily experiences of the pibes (young men) of the slums. Themes of alcohol and drug consumption, leisure time, delinquency and misogynist and heteronormative sexuality in villera lyrics, added to the poetic importance of ideas of marginalised territories and the preference for a look based on sportswear, earned the music comparisons with gangsta rap, by which it was in fact inspired (Martin Reference Martín2008).

One of the innovations of cumbia villera was to make visible the fact that the working class suffered not only a form of class violence but also racist violence. It contributed to an affirmation of the negro villero (heir of the cabecita negra), stigmatised from above, as a positive identification. The band Meta Guacha presented songs in which they identified themselves as negros, antagonistically opposed to those with ‘light skin’ and put forward visions of popular joyfulness related to Blackness. Pablo Lescano, one of the best-known artists of the genre, has the proud phrase 100% negro cumbiero tattooed on his chest and it is common for him to harangue his audience at concerts by shouting ‘Las palmas de todos los negros ¡arriba!’ (all the negros put their hands in the air!), eliciting enthusiastic responses from his followers. By exposing the racial dimensions of the material and symbolic violence systematically experienced by young people in poor neighbourhoods, and by proposing strategies for appropriating and reversing these forms of racialisation, cumbia villera, despite its other problematic aspects (e.g. its gender politics), constitutes an important phenomenon in the recent anti-racist cultural production of Argentina.

The Recent Scenario (since 2003)

The institutionalisation and recognition of ethnic-racial collectives that took place at the end of the 1990s and the turn of the century generated a context that allowed for the growth of ethnic-racial organisations, the expansion of rights and forms of recognition and the provision of certain resources. But it also generated new challenges. It is relevant to mention two. In relation to both Indigenous peoples and Afro-descendants there was a demand for ‘authenticity’, even when self-recognition was the fundamental criterion, used for example in the census. The registration of Indigenous communities, for instance, requires a socio-historical report proving that the collective has verifiable ties to an Indigenous nation and that it is a social unit. At the same time, very light-skinned people who identified as Afro-descendants encountered resistance to being recognised as such (Geler Reference Geler2016). Cultural representations thus became mediated by the demand to demonstrate ‘authentic’ difference in order to achieve recognition. Any aspect that was seen as ambiguous gave rise to doubts about authenticity (Briones Reference Briones2005; Vivaldi Reference Vivaldi2016).

With the arrival of Kirchnerism in 2003, the demands for more pluralistic visions of the nation coming from different spheres – Indigenous, Afro-descendant and migrant activists, the working classes and progressive sectors – found even more echoes in the state. The government developed ambitious cultural policies in this respect, especially after the inauguration of Cristina Kirchner as president in 2007. The clearest example was the organisation of the celebrations for the Bicentennial of the May Revolution in 2010, which included large-scale events by the experimental theatre company Fuerza Bruta. Kirchner’s government systematically emphasised the contrasts between these celebrations and those of the 1910 Centennial. The Secretary of Culture, Jorge Coscia, wrote:

In 1910, the ruling elite celebrated its supposed condition as a white, homogeneous, Europeanised nation, relegating everything that could have a local, criollo or Indigenous flavour to a second, third plane … (T)his Government does not consecrate just one way of being national, as was the case one hundred years ago … We celebrate diversity as our most valuable specificity.

One of the central moments was the Bicentennial Parade, which attracted two million people along its route through the avenues of Buenos Aires. Through nineteen tableaux, this parade of floats represented major milestones of Argentine history and popular culture, from a sensory and affective perspective rather than a narrative and chronological one. In other words, rather than promoting a particular interpretation of Argentine history and nationhood in line with the traditional official vision, the event sought to generate an emotional response in the public through audiovisual stimuli and the energy generated by the crowds of people in the public space.

The first scene of the parade symbolised the native peoples. It consisted of three floats carrying Indigenous performers from different native nations, with their traditional costumes, masks, paintings and tools.Footnote 10 The second, entitled ‘The Argentine Republic’, showed dancers dressed in the colours of the national flag, suspended in the air from a crane, representing the homeland.Footnote 11 The two female dancers selected to share this role had been deliberately chosen for their mixed-race features. Hanging from a harness, the young women danced to the rhythm of carnavalito (a northern folkloric genre with a strong Indigenous Kolla influence) and candombe – as well as electronic music – to emphasise the ethnically heterogeneous character of the nation. A group of dancers and musicians accompanied the float. Musical allusions to the quintessentially plebeian celebration (carnival), in its Andean and Afro-descendant manifestations, were combined with the young women’s constant encouragements to the people to join in the dancing in the street. All this accentuated the staging of the nation in a multicultural and subaltern key and the event as a popular festival, mobilising various emotions, particularly joy (Citro Reference Citro2017). Some of other floats in the parade showed different episodes of Argentine history, in some of which Afro-descendant actors participated. Alongside European immigrants, there was even room for the visibilisation of others, such as Bolivians and Chinese.

According to the official plan, the order of the first two floats should have been the reverse – first the Republic, then the Indigenous peoples – but a last-minute glitch forced the change to be improvised. President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner later admitted: ‘What had to happen happened, which was fairer and more historically rigorous, the originary peoples at the beginning’ (2019: 256). In this almost accidental way, the parade proposed a refoundation of the nation located in Indigenous cultures and not in the Revolution of 1810. And although the scene fell back on a conception of Indigeneity essentialised and located in the past – the public television narration systematically used the imperfect tense to refer to the originary peoples, while the costumes and scenery of the floats had almost no present-day references – the fact that the performers were, to a large extent, Indigenous distanced it from the indigenist nativism of cultural manifestations of other decades (see Ko Reference Ko2013).

Despite its positive elements, the opening by the Kirchnerist government to resignifications of Argentina in multicultural terms that had been introduced during Menemism sometimes came into conflict with Indigenous and Afro-descendant organisations, in part because of the attempted capture, by the state apparatus, of the discourses and affective energies of these associations and, in the case of native peoples, by the continuation of neo-extractivism, agribusiness and the conflict over land (Svampa Reference Svampa2019). However, in general, Kirchnerism marked an important contrast with previous official discourses and cultural policies by contributing to the distancing that society had already begun, on the way to the 2001 crisis, from the image of a homogeneously white nation. The impact it had on the field of artistic production was substantial: anti-racist messages and the vindication of the non-white as part of the nation seeped everywhere, from literature to cinema and TV, from music to popular celebrations (e.g. Citro and Torres Agüero Reference Citro and Agüero2015).

None of this means that the more traditional views have dissipated. Racism continued stubbornly and even acquired a more aggressive tone, as the voices questioning it multiplied. The coming to power of the liberal-conservative Mauricio Macri in 2015 implied, in part, an attempt to return to an idea of nation of European genealogy. The audiovisual production of the state under his presidency reversed the previous tendency to represent Argentina through varied bodies, with a strong presence of non-whites. Under his successor Alberto Fernández (2019–2023), by contrast, the state developed anti-racist policies through INADI and the Dirección Nacional de Equidad Racial, Personas Migrantes y Refugiadas (National Directorate of Racial Equity, Migrants and Refugees), created in 2020 and directed by Carlos Álvarez Nazareno, an Afro-descendant activist.

In the midst of these implicit struggles about the ethnic-racial profile of the nation, there have been interesting developments in the field of culture and activism, some of which became sites for collaboration for the CARLA project. One such is the Mapuche Theatre Group El Katango (see Chapter 6). Founded in 2002 in the Patagonian city of Bariloche by the Mapuche theatre maker, teacher and researcher Miriam Álvarez (co-author of Chapter 6), El Katango was formed in the space for political debate and theatrical creation called the Mapuche self-affirmation campaign Wefkvletuyiñ (‘We are Re-emerging’ in Mapuzugun). Another CARLA collaborator is the theatre company Teatro en Sepia (TES), founded in 2010 (again see Chapter 6, co-written by TES director Alejandra Egido). TES seeks to break the historical indifference and invisibility of the Afro presence in Argentina through the performing arts. Although TES and El Katango emerged in the context just described, in which legal recognition had allowed ethnic-racial collectives a way of working with the state while society as a whole was beginning to accept Argentina’s ethnic-racial plurality, both theatre groups still had to confront invisibilisation, racist stereotypes, the essentialisation of identity and racist structures of territorial dispossession and the criminalisation of Mapuche people, as well as marginalisation in the urban space and labour segregation for Afro women.

To the panorama of artistic initiatives that made visible the claims of Indigenous and Afro peoples, a new element was added in 2019 with the founding of Identidad Marrón, the anti-racist art collective with which we started this chapter, which in a very short time gained a place in public conversations. The novelty of their approach lies partly in the introduction of the term marrón, which they chose as a deliberate act of reclamation and political visibility. While negro has historically been wielded as a class-based slur, there has also been a tendency to resort to words such as trigueño (wheat-coloured), moreno or morocho when referring to people with darker skin tones – terms that have been used to sidestep explicit discussions of race. By embracing marrón as a new term for classifying people, the collective deliberately sidesteps the old familiar euphemisms, forcing a more direct conversation about race and identity in Argentine society.

The other novel aspect of Identidad Marrón’s approach is that they aspire to an anti-racist policy that relies not on discrete minority communities but on the majority that makes up the working classes, who have brownish skins and non-white features but who are often unaware of their precise ethnic origins. Identidad Marrón aspires to give voice to the marrones, who, according to its definition, are the numerous people of Indigenous, mestizo, migrant and peasant origins who live in the cities. Its activism is located in what they term an ‘anti-racism with class consciousness’ which aims to combat racism at all levels, especially in the world of culture, while recognising the imbrication of racism and classism. Their initiatives include artistic interventions such as the one mentioned in the introduction to this chapter, as well as street actions, workshops and media and social media campaigns. As part of their collaboration with CARLA, in addition to visual works produced for our virtual exhibition, a book compiling their texts and initiatives was published (Identidad Marrón 2021).Footnote 12

In sum, over the last two decades, although white and European Argentina persists for certain sectors as a horizon of nationality that is impossible to renounce, recent years have exposed even more than before the inability of this narrative to serve as a point of reference for large parts of society. The horizon of anti-racism and the affirmation of non-whiteness as part of the nation are moving forward in a very evident way. In 2020, the anti-racist protests that the assassination of George Floyd detonated in several parts of the world also impacted Argentina, and public debate about the existence of structural racism in Argentina increased further.

As a coda, it is important to note that the election of far-right libertarian Javier Milei as president in late 2023 marks a concerning change of direction for Argentina’s trajectory towards greater racial recognition. Milei’s rhetoric actively celebrates European heritage and Argentina’s supposed exceptional whiteness in the Latin American context. His praise of controversial historical figures such as Julio Argentino Roca – responsible for the military campaigns against Indigenous peoples in Patagonia – combined with his ultra-free-market ideology and commitment to intensifying extractive industries suggests that Indigenous peoples and other racially marginalised groups, as well as the working class, will be disproportionately affected by his policies. The cultural and political gains achieved by anti-racist and ethnic minority organisations and artists over the past decades, and the resilient networks of resistance that have emerged, will surely be tested by this reactionary turn. The coming years will likely see increased tension between official discourses that attempt to restore myths of white Argentina and grassroots movements and artistic expressions that insist on the nation’s racial diversity and demand concrete actions against racism.

Conclusion

In this chapter we traced a long history of artistic productions whose relationship with racism we described using three categories: visibilising, vindicatory and overtly anti-racist. Although, as we have pointed out, it is only in recent years that an anti-racist culture stricto sensu has been consolidated in Argentina, we have proposed seeing certain vindicatory expressions as implicitly anti-racist, even though they have not always been interpreted by others as such. The peculiar manifestation in Argentina of racial hierarchies combined with the persistent denial that they existed – and, thus, that racism was a problem – forced us to pay attention to the oblique, allusive, non-confrontational ways that local creators tried to deal with the reality of ethnic-racial discrimination. In particular, the phenomenon of generic ‘popular Blackness’, not diasporic or related to any specific ethnicity, drove us to go beyond more easily identified anti-racist dynamics, such as the affirmation of minority identities and the defence of their rights. If anti-racism in Argentina is now expressed in a verbal, direct and confrontational way that seems totally novel, it is also true that a much older genealogy can be traced, which we have outlined here.

Having concluded this overview, it should be noted that a majority of the intellectuals and creators who put forward vindicatory views in public were white, middle-class males. Only in the current, more actively anti-racist, context do we see Indigenous, Black and marrón people, including women and trans and non-binary people, at the forefront of the debate. Neither Ricardo Rojas, Martín Castro, Antonio Tormo, Jorge Abelardo Ramos, Ricardo Carpani nor León Gieco are perceived in Argentina as non-white, nor were they lower class. However, alongside them, often in the same artistic fields, other artists whose bodies did manifest racial differences added their creations of anti-racist tenor. Among others, we have mentioned Buenaventura Luna, Atahualpa Yupanqui, Aimé Painé, Daniel Toro, Fidel Nadal, ‘La Mona’ Jiménez and Meta Guacha. There is nothing strange in this confluence: for a long time white people were in the best position to mount a defence of the cabecitas negras without paying the cost of being seen as such. But, in addition, the struggles for the ethnic profile of the nation were intertwined with class differences and with national politics, in particular with the Peronism versus anti-Peronism cleavage. This scenario was conducive to some white people becoming involved in the vindication of non-whiteness. The outcome of this struggle affected them directly.

Certainly, some of the creations contributed by white artists are purely visibilising, and ambivalences and blind spots can be found in relation to racial hierarchy: for example, paternalism, the reproduction of certain stereotypes and a tendency to visualise the subject in reference to rural but not urban spaces, or in the past rather than the present. There was also a certain preference for Indigeneity, with little room for Afro-descendants. But there was also room for vindicatory discourses with anti-racist potential. All in all, there is no doubt that the debates, sounds and images produced by some cultural products generated by white people contributed powerfully to making racism visible in Argentina and were part of the same scene that fed the creations of non-white artists.