1. Introduction

This study examines the gender gap in the relationship between receiving a childhood allowance and later financial outcomes, including financial literacy, monetary attitudes, and time preferences, which together influence long-term financial decision-making.Footnote 1 Gender differences in financial literacy are well-documented worldwide, with women consistently scoring lower than men (Hasler and Lusardi Reference Hasler and Lusardi2017; Lusardi and Messy Reference Lusardi and Messy2023; Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Ha, Nguyen, Doan and Thanh Phan2022).Footnote 2 Enhancing women’s financial literacy is critical for improving retirement preparedness and overall financial well-being, particularly given their longer life expectancies, lower lifetime income, and career interruptions due to childcare and caregiving responsibilities (Hasler and Lusardi Reference Hasler and Lusardi2017; Bucher-Koenen et al. Reference Bucher-Koenen, Lusardi, Alessie and van Rooij2017).

Surprisingly, this gender gap is evident as early as age 15, according to the OECD (2017), suggesting that childhood experiences may play a critical role in shaping financial literacy and that these experiences might differ between boys and girls. This contributes to disparities that persist into adulthood.Footnote 3

Research on adult financial literacy has identified factors such as age, education level, income disparity, and the frequency of financial information access as contributors to the gender gap in financial literacy (Fonseca et al. Reference Fonseca, Mullen, Zamarro and Zissimopoulos2012; Bucher-Koenen et al. Reference Bucher-Koenen, Lusardi, Alessie and van Rooij2017; Chen and Volpe Reference Chen and Volpe2002); however, these factors do not fully account for the observed differences (Maruyama Reference Maruyama2022; Hasler and Lusardi Reference Hasler and Lusardi2017; Bucher-Koenen et al. Reference Bucher-Koenen, Lusardi, Alessie and van Rooij2017).Footnote 4 In Japan, financial literacy levels are particularly low among young women and individuals with lower education levels (Sticha and Sekita Reference Sticha and Sekita2023).

To understand this potential gender gap in financial literacy, research has increasingly focused on how financial literacy is formed. Childhood experiences – such as parental financial behavior, family discussions about money, exposure to financial education, and socioeconomic background – are recognized as significant influences on individuals’ adult financial literacy (LeBaron et al. Reference LeBaron, Holmes, Jorgensen and Bean2020; Grohmann, Kouwenberg, and Menkhoff Reference Grohmann, Kouwenberg and Menkhoff2015; Kaiser and Menkhoff Reference Kaiser and Menkhoff2017; Rudeloff, Brahm, and Pumptow Reference Rudeloff, Brahm and Pumptow2019). An early introduction to financial literacy has also been shown to foster healthy financial habits that persist into adulthood (Pramitasari et al. Reference Pramitasari, Syarah, Risnawati and Shofiyah Tanjung2023). Early financial socialization, including parental discussions about financial decisions, can enhance financial understanding even among young children, potentially laying the foundation for lifelong financial literacy (Fletcher and Wright Reference Fletcher and Wright2024). However, despite these insights, limited research exists examining how home education during childhood contributes to the gender gap in adult financial literacy (Agnew, Maras, and Moon Reference Agnew, Maras and Moon2018).

This study explores the role of receiving an allowance (or pocket money) as a component of early childhood financial education. Providing children with an allowance offers practical experience in money management, allowing them to make choices about spending and saving, and helping them to understand the value of money.

Some studies have used the method of receiving allowances as a proxy for financial education at home. For instance, Lewis and Scott (Reference Lewis and Scott2000) found that receiving regular allowances during childhood may enhance financial ability in adolescence, based on a study of a UK sample aged 16–18 in full-time education. Similarly, data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics on young adults in the United States revealed a negative association between receiving an allowance as a childhood socialization variable and financial worry in adulthood (Kim and Chatterjee Reference Kim and Chatterjee2013). Brotherson (Reference Brotherson2023) further emphasized the benefits of providing children with allowances and teaching them money management skills from an early age. By presenting five key guidelines for children’s allowances, the study highlighted that giving children a regular allowance to manage significantly contributes to developing financial management skills and behaviors for the future.Footnote 5

Based on these insights, this study investigates the potential gender gap in how children receive allowances in Japan. Specifically, it explores how different methods of receiving allowances, such as regular or as needed, contribute to the gap in financial literacy observed in adulthood, emphasizing the role of early childhood education.

Several studies in Japan (Maruyama Reference Maruyama2022; Matsukawa, Sekiguchi, and Akiyama Reference Matsukawa, Sekiguchi and Akiyama2018) have examined whether allowances, as a measure of home education, influence the gender gap in children’s financial literacy and self-efficacy but found no significant association. In contrast, this study focuses on the long-term relationship between childhood allowance and adult financial literacy, exploring how early financial education shapes gender disparities later in life.

Previous research has identified various factors influencing financial literacy, such as academic background, parental education, income, numeracy skills, confidence, time preference, risk aversion, monetary attitudes, gender, age, and marital status (Goyal and Kumar 2021; Bianchi Reference Bianchi2018; Böhm et al. Reference Böhm, Böhmová, Gazdíková and Šimková2023; Jappelli and Padula Reference Jappelli and Padula2015; Kawamura et al. Reference Kawamura, Mori, Motonishi and Ogawa2021; Lusardi et al. Reference Lusardi, Michaud and Mitchell2017; Yamane et al. Reference Yamane, Aman and Motonishi2021a, Reference Yamane, Aman and Motonishi2021b). Among these, time preference – the tendency to value present rewards over future benefits – and money ethics, which reflect attitudes and behaviors toward money, are of particular interest here. These factors are not only critical for shaping financial literacy but may also be influenced by early financial experiences, such as receiving an allowance.Footnote 6

This study examines various outcomes associated with childhood allowances in adulthood. These outcomes include financial literacy, monetary attitudes, and time-discounting preferences. Previous studies have shown that monetary attitudes and time-discounting preferences significantly influence financial literacy (Kawamura et al. Reference Kawamura, Mori, Motonishi and Ogawa2021; Yamane, Aman, and Motonishi Reference Yamane, Aman and Motonishi2021a; Reference Yamane, Aman and Motonishi2021b).Footnote 7 Additionally, some studies have explored how time preference affects participation in financial education programs, which, in turn, may improve individuals’ financial literacy (Meier and Sprenger Reference Meier and Sprenger2013). Therefore, it is essential to analyze these variables alongside financial literacy.

Given the scarcity of studies on this topic in Japan, this research provides new insights into the potential gender gap in how children receive allowances, addressing an important gap in the financial literacy literature.

While this study is based on questionnaire survey data and does not attempt to identify causality, we interpret the observed associations with care, considering a range of socioeconomic controls.Footnote 8

The rest of this study is organized as follows. The “Data and methods” section explains the data and methods employed. Specifically, we present the results of a factor analysis of survey data to gain insights into the underlying dimensions of monetary attitudes. We then report the results of regression analyses that examine the associations between childhood allowance and monetary attitudes, time preferences, and financial literacy. The following section discusses the innovation in our results and links them to those of previous studies. Finally, the Conclusion discusses our study’s limitations and reviews future research avenues.

2. Data and methods

In this section, we provide an overview of our survey and key variables, followed by the results of the factor analysis conducted on the survey data to gain insights into dimensions of monetary attitude.

2.1. Survey outline

This study used purpose-built survey data obtained from the Research Institute for Socio-Network Strategies (RISS) of Kansai University. The survey was conducted online by MyVoice Communications, Inc. from March 31 to April 6, 2020, using a stratified sampling method based on the 2019 Basic Resident Register. The sample was designed to approximate the national average distribution in terms of gender, prefecture, and age structure, resulting in 3,601 valid responses (male: 1,784, female: 1,871; mean age: 50.30 years, SD = 15.75). In addition to questions about how respondents received their allowance as children, financial literacy, and monetary attitudes, the survey included a wide range of questions about education, household income, time-discounting preferences, and parents’ education.

2.2. Monetary attitudes

Monetary attitudes are a critical aspect of individuals’ financial behavior and decision-making processes and have been extensively researched in psychology. Scales such as the Money Attitudes Scale, Money Beliefs and Behavior Scale, and Money Ethic Scale have been developed to measure these constructs (Furnham Reference Furnham1984; Tang Reference Tang1992; Yamauchi and Templer Reference Yamauchi and Templer1982).Footnote 9 These basic scales have allowed various other scales to be constructed. Although they are referred to by different names, they all measure the image of money, the use of money, and feelings toward money. Substantial overlap exists in their content (Furnham Reference Furnham2014; Watanabe and Sato Reference Watanabe and Sato2010). Furthermore, these attitudes vary according to gender, culture, education, and other sociodemographic factors that influence financial decision-making processes (Furnham Reference Furnham1984; Lim and Teo Reference Lim and Teo1997; T. L. Tang Reference Tang1993; Yamane, Aman, and Motonishi Reference Yamane, Aman and Motonishi2021a; Reference Yamane, Aman and Motonishi2021b; Aman, Motonishi, and Yamane Reference Aman, Motonishi and Yamane2024). Generally, men tend to view money as a cognitive element of achievement, freedom, and power more than women. Women tend to view money as an emotional element of anxiety more than men (Furnham et al. Reference Furnham, Wilson and Telford2012; Tang Reference Tang1992). Moreover, some studies suggest that monetary attitudes can have tangible associations with economic behaviors and outcomes, including investment experience and decisions (Keller and Siegrist Reference Keller and Siegrist2006a, Reference Keller and Siegrist2006b; Tang and Chiu Reference Tang and Chiu2003). Additionally, people with negative attitudes toward money have less investment experience and poor financial literacy (Yamane, Aman, and Motonishi Reference Yamane, Aman and Motonishi2021a; Reference Yamane, Aman and Motonishi2021b; Aman, Motonishi, and Yamane Reference Aman, Motonishi and Yamane2024).

2.3. Factor analysis

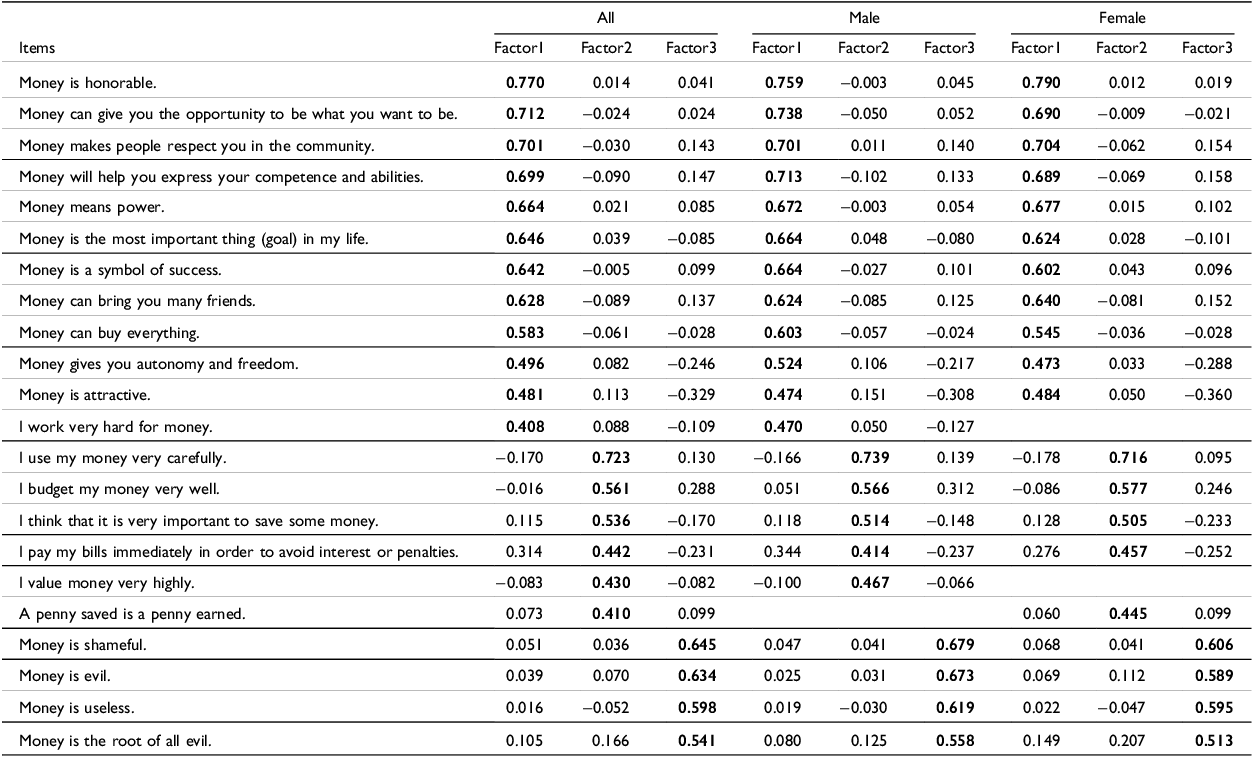

Thirty questions concerning monetary attitudes were included in the survey, designed with reference to Tang (Reference Tang1992, Reference Tang1993). We conducted factor analysis on three sets of 30 questions: one for the entire sample, one for male respondents, and one for female respondents. This approach was adopted because previous studies have suggested that men and women may perceive and internalize monetary attitudes differently, which could result in different factor structures (T. L. Tang Reference Tang1992; Yamauchi and Templer Reference Yamauchi and Templer1982; Furnham Reference Furnham1984). Moreover, several studies in psychology, psychiatry, and public health have conducted subgroup-specific factor analyses to account for potential heterogeneity in the factor structures (Everson, Millsap, and Rodriguez Reference Everson, Millsap and Rodriguez1991; Yamaguchi et al. Reference Yamaguchi, Murayama, Onda, Mitsuhashi, Yamazaki, Nakazawa and Koyama2009; Tomokawa et al. Reference Tomokawa, Asakura, Keosada, Bouasangthong, Souvanhxay, Kanyasan, Miyake, Soukhavong, Thalangsy and Moji2020). Initially, we conducted a factor analysis using principal component analysis with promax rotation to determine the number of factors, as indicated by the screen plot.Footnote 10 Subsequently, we eliminated items with factor loadings below 0.40 and performed another factor analysis for each group. The results suggested a three-factor structure appropriate for each group. Table 1 presents the results of the factor analysis for each group.

Table 1. Rotated factor loadings

Factor 1, Factor 2, and Factor 3 represent POSITIVE , BUDGET , and NEGATIVE monetary attitudes, respectively. Each response was measured on a 4-point Likert scale, where 4 = totally agree, 3 = slightly agree, 2 = slightly disagree, and 1 = totally disagree. Factor analysis with promax rotation and Kaiser normalization was applied to each group. Factor loadings of 0.4 or greater are presented in bold. The sample size was N = 3,085 for the entire sample, N = 1511 for males, and N = 1574 for females.

While Yamane et al. (Reference Yamane, Aman and Motonishi2021b) found four factors in their analysis, our study resulted in only three because of the difference in sample grouping. They conducted factor analysis on the entire sample, whereas we performed separate analyses for male and female respondents, resulting in distinct factor structures. We named these factors based on our interpretation of previous research (T. L. Tang 1992; Reference Tang1993; T. L. P. Tang Reference Tang1995; Yamane, Aman, and Motonishi Reference Yamane, Aman and Motonishi2021b; Aman, Motonishi, and Yamane Reference Aman, Motonishi and Yamane2024). We named the first factor POSITIVE, representing positive attitudes toward money such as perceived honor, opportunities, and social status. The second factor, BUDGET, signifies good budgeting habits related to responsible financial management, including budgeting, savings, and bill payments. Finally, the third factor, NEGATIVE, indicates negative attitudes toward money, such as associations with evil or shame.

2.4. Hypotheses

As mentioned in the introduction, some studies have found that receiving an allowance as a child – serving as a proxy variable for financial education at home – is positively associated with financial activities. Receiving an allowance during childhood serves as an early form of financial education, exposing children to money management, budgeting, and decision-making at a young age. This hands-on experience provides practical skills and an understanding of the value of savings and budgeting. These experiences may contribute to the development of stronger financial literacy skills in adulthood. Therefore, we initially hypothesized that receiving an allowance as a child would be associated with attitudes toward money. Accordingly, we proposed the following:

Hypothesis 1: Receiving an allowance during childhood is associated with enhanced positive monetary attitudes during adulthood.

Individuals who received an allowance during childhood are expected to have a more positive mindset toward money, which is characterized by fewer negative attitudes. Specifically, after controlling for parental education and demographic variables, we hypothesized that receiving an allowance would be positively associated with POSITIVE and negatively associated with NEGATIVE.

Hypothesis 2: Regular allowances during childhood are associated with better money management skills in adulthood.

Individuals who received a regular allowance on a consistent schedule during childhood were expected to have better money management skills in adulthood than those who did not receive a regular allowance. By controlling for parental education and demographic variables, it was expected that receiving an allowance would be positively associated with good budgeting habits (BUDGET), which are key components of overall money management skills.

Next, the association between receiving an allowance as a child and time-discounting preferences is complex and multifaceted. Receiving a regular allowance on a consistent schedule (e.g., monthly) may encourage children to practice delayed gratification, as they learn to save money for future goals rather than spending it immediately. This experience could potentially shape time-discounting preferences, leading to a preference for delayed rewards during adulthood. However, receiving an allowance on an as-needed basis may foster a mindset focusing on immediate needs and instant gratification. Children who receive money only when necessary may be more inclined to prioritize short-term desires over long-term goals, leading to a preference for immediate rewards in adulthood. This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: The method of receiving an allowance during childhood is associated with time-discounting preference in adulthood.

It is expected that how an allowance is received during childhood will influence time-discounting preferences in adulthood. Specifically, individuals who received a regular allowance on a consistent schedule during childhood are expected to have lower levels of time discounting, whereas those who received an allowance on an as-needed basis are expected to have higher levels. Thus, a regular allowance is negatively associated with the time-discounting preference, whereas an as-needed allowance is expected to be positively associated after controlling for parental education and demographic variables.

Finally, regarding the relationship between receiving an allowance and financial literacy, individuals who received a regular allowance on a consistent schedule during childhood were expected to have higher levels of adult financial literacy than those who did not. Therefore, we proposed the following:

Hypothesis 4: Regular allowances during childhood are associated with higher financial literacy.

2.5. Estimation models

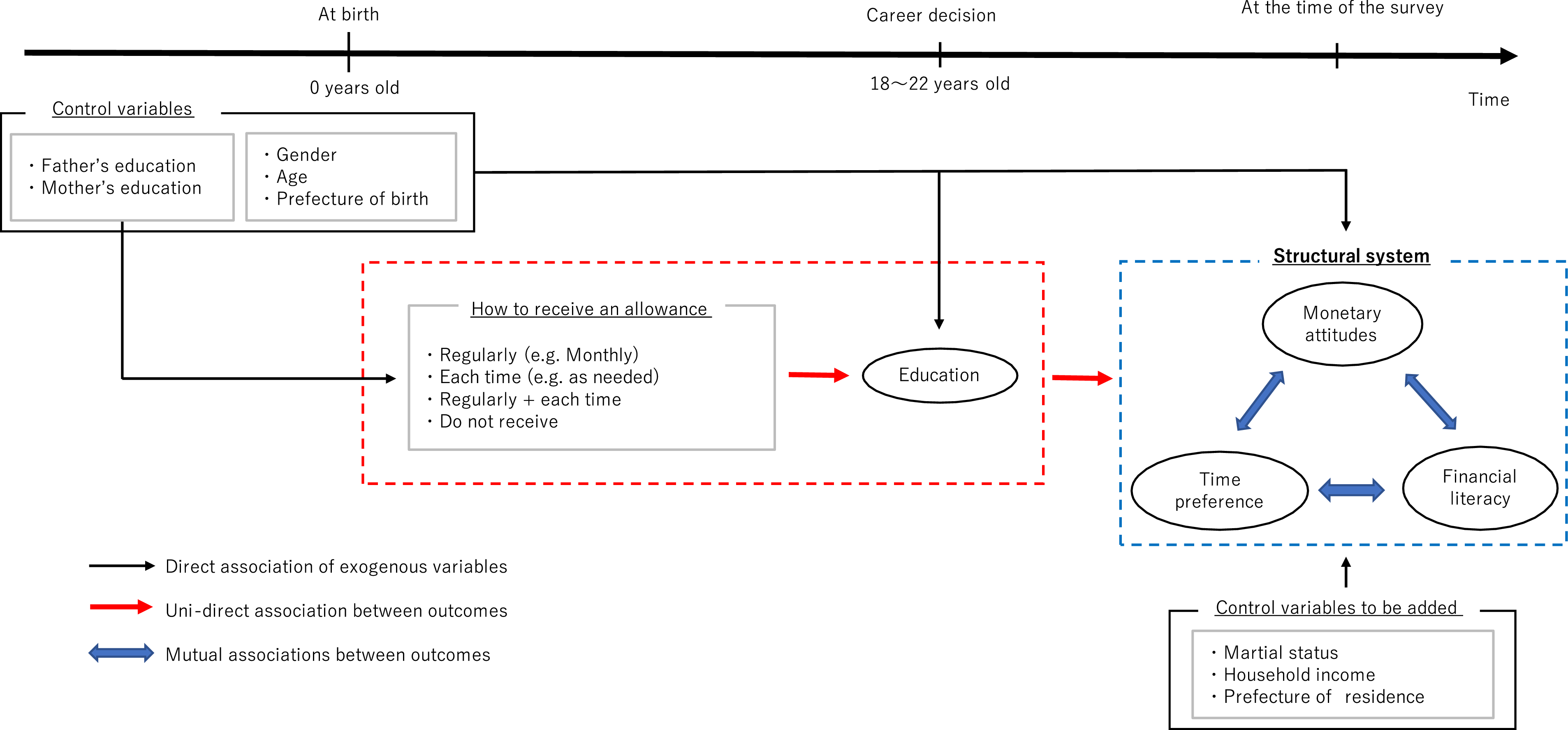

Figure 1 depicts the timeline from birth to the survey, illustrating the connection between receiving an allowance in childhood and each outcome related to financial activities.Footnote 11 Although the outcome variables such as monetary attitudes (POSITIVE, BUDGET, NEGATIVE), time-discounting preference, and financial literacy were assessed at the time of the survey and thus simultaneity cannot be completely ruled out, the allowance-giving style is a predetermined variable that occurred during childhood and precedes the development of these outcomes. This temporal ordering reduces concerns about reverse causality.

Figure 1. Path diagram illustrating the associations between childhood allowance and long-term outcomes. This figure depicts the timeline path from birth until the survey, illustrating how allowance is associated with each outcome related to financial activities.

Therefore, to test Hypotheses 1–4, we regressed each of the five outcome variables on receiving an allowance in childhood. We employed ordinary least squares (OLS) to estimate the associations between childhood allowance and each outcome variable. Thus, the equation is as follows:

$$\eqalign{ {Y_{ik}} = \alpha k +& 38; \sum\limits_m {{\beta _{k,m}}} ALLOWANCE_{im} + \gamma_{k}MAL{E_i} \cr & 38; + \sum\limits_m {{\delta _{k,m}}} \left( {ALLOWANCE_{im}\; \times MAL{E_i}} \right) + \theta_k{X_i} + e_{ik},\;\quad \;k = 1, \ldots, 5 \cr} $$

$$\eqalign{ {Y_{ik}} = \alpha k +& 38; \sum\limits_m {{\beta _{k,m}}} ALLOWANCE_{im} + \gamma_{k}MAL{E_i} \cr & 38; + \sum\limits_m {{\delta _{k,m}}} \left( {ALLOWANCE_{im}\; \times MAL{E_i}} \right) + \theta_k{X_i} + e_{ik},\;\quad \;k = 1, \ldots, 5 \cr} $$

Here,

![]() ${Y_{ik}}$

represents the k-th dependent variable (POSITIVE, BUDGET, NEGATIVE, time-discounting preference, and financial literacy) for the i-th individual.

${Y_{ik}}$

represents the k-th dependent variable (POSITIVE, BUDGET, NEGATIVE, time-discounting preference, and financial literacy) for the i-th individual.

![]() $ALLOWANC{E_{im}}$

is the m-th dummy variable indicating the receipt of an allowance during childhood (e.g., Regularly, Each time, Regularly + Each time).

$ALLOWANC{E_{im}}$

is the m-th dummy variable indicating the receipt of an allowance during childhood (e.g., Regularly, Each time, Regularly + Each time).

![]() $MAL{E_i}$

is a gender dummy variable equal to 1 if the respondent is male and 0 otherwise. The interaction terms capture gender differences in the associations between allowance and each outcome.

$MAL{E_i}$

is a gender dummy variable equal to 1 if the respondent is male and 0 otherwise. The interaction terms capture gender differences in the associations between allowance and each outcome.

![]() ${X_i}$

is a set of control variables, including age, marital status, household income, and educational attainment as individual attributes, as well as parents’ education and prefecture of birth as confounding factors.Footnote

12

All these variables are regarded as exogenous to the outcome variables.

${X_i}$

is a set of control variables, including age, marital status, household income, and educational attainment as individual attributes, as well as parents’ education and prefecture of birth as confounding factors.Footnote

12

All these variables are regarded as exogenous to the outcome variables.

![]() ${e_{ik}}$

denotes the disturbance term. The estimated coefficients represent conditional associations between childhood allowance and each outcome.

${e_{ik}}$

denotes the disturbance term. The estimated coefficients represent conditional associations between childhood allowance and each outcome.

If receiving an allowance during childhood is positively associated with stronger monetary attitudes (as measured by the POSITIVE factor) in adulthood among females (the reference group), the corresponding coefficient (

![]() $\beta $

) will be positive, consistent with Hypothesis 1. Conversely, if receiving an allowance is associated with a lower NEGATIVE factor, then the coefficient will be negative, which also supports Hypothesis 1. Additionally, a positive coefficient for the BUDGET factor would be consistent with Hypothesis 2, indicating better money management skills.

$\beta $

) will be positive, consistent with Hypothesis 1. Conversely, if receiving an allowance is associated with a lower NEGATIVE factor, then the coefficient will be negative, which also supports Hypothesis 1. Additionally, a positive coefficient for the BUDGET factor would be consistent with Hypothesis 2, indicating better money management skills.

Similarly, if receiving a regular allowance is positively associated with financial literacy, this supports Hypothesis 3. Furthermore, if a regular allowance is associated with lower time-discounting preferences, a negative coefficient would support Hypothesis 4. Conversely, if receiving an allowance on an as-needed basis is associated with higher time-discounting preferences, the coefficient will be positive, which is also consistent with Hypothesis 4.

In models with gender interaction terms, the main coefficients reflect the associations for females, while the interaction terms capture the deviations for males.

To complement this interaction analysis, we also estimate Eq. (1) separately by gender, excluding the interaction terms. This stratified approach allows for a more direct assessment of whether the associations between allowance patterns and financial outcomes differ between males and females.

It is also important to note that the associations identified in this study should not be interpreted as causal effects. Given the observational nature of the data, the results may be subject to unobserved variable bias – particularly due to parental characteristics such as financial values and parenting styles that were not captured in the survey. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings.

3. Estimation results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

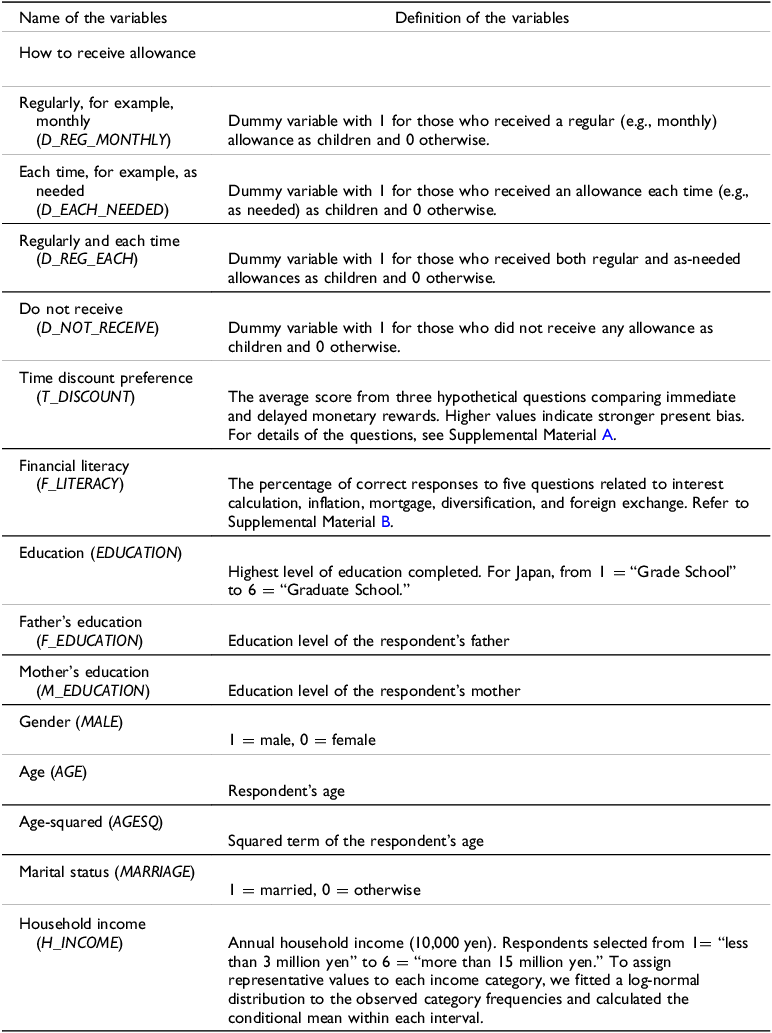

Table 2 summarizes the definitions of the variables used in the estimation, and Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics.

Table 2. Definition of the variables

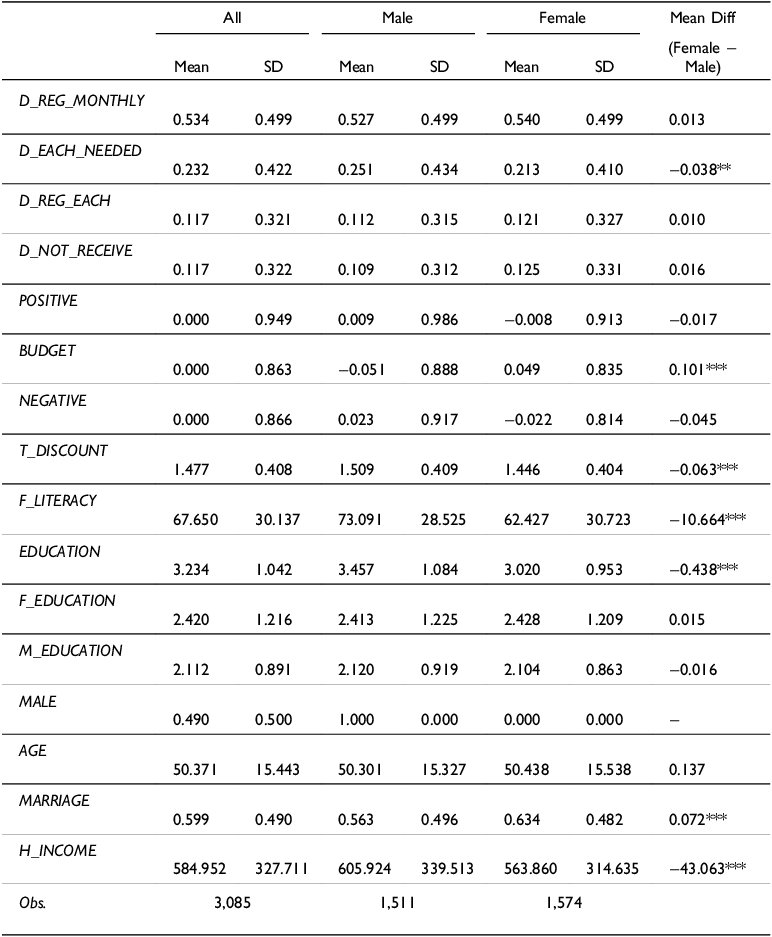

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of the variables

Obs. represents the number of observations, and SD represents standard deviation. “Mean Diff (Female − Male)” shows the differences in means between female and male respondents. Factor scores for POSITIVE, BUDGET, and NEGATIVE were standardized with a mean of zero and unit variance based on the pooled sample; therefore, gender differences in these scores reflect relative tendencies within the shared factor structure. Asterisks indicate statistical significance of the difference based on two-sample t-tests: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

In terms of childhood allowance experience, 53.4 percent of respondents reported receiving a regular monthly allowance (D_REG_MONTHLY), 23.2 percent received an allowance only when needed (D_EACH_NEEDED), and 11.7 percent received both regularly and on an as-needed basis (D_REG_EACH). Only 11.7 percent reported not receiving any allowance (D_NOT_RECEIVE). These distributions are broadly consistent with the 2023 Survey on Financial Literacy and Daily Life among 15-year-olds, which found that 61.2 percent received a regular monthly allowance and 25.9 percent received allowances only when needed. Although our respondents are adults recalling past experiences, the similarity in allowance patterns suggests that such practices have remained relatively stable over time, supporting the relevance and generalizability of our data.Footnote 13

We also conducted two-sample t-tests to examine gender differences in key variables. As shown in Table 3, the differences in F_LITERACY, T_DISCOUNT, and BUDGET, among others, are statistically significant. For example, the average financial literacy (F_LITERACY) score is approximately 73.09 for males and 62.43 for females. The difference of −10.66 is statistically significant at the 1 percent level, indicating that females have significantly lower financial literacy than males.

3.2. OLS estimates with gender interactions

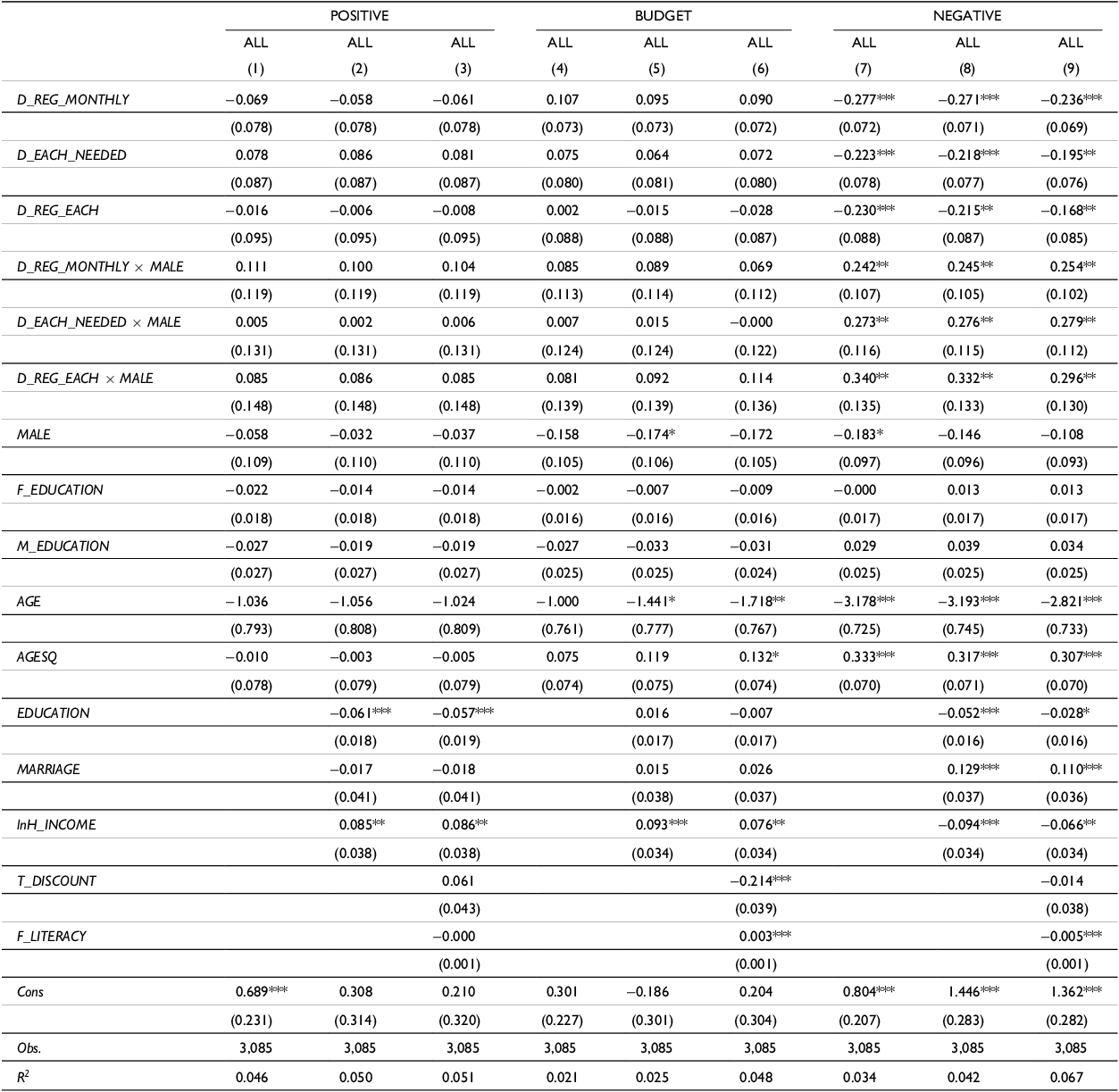

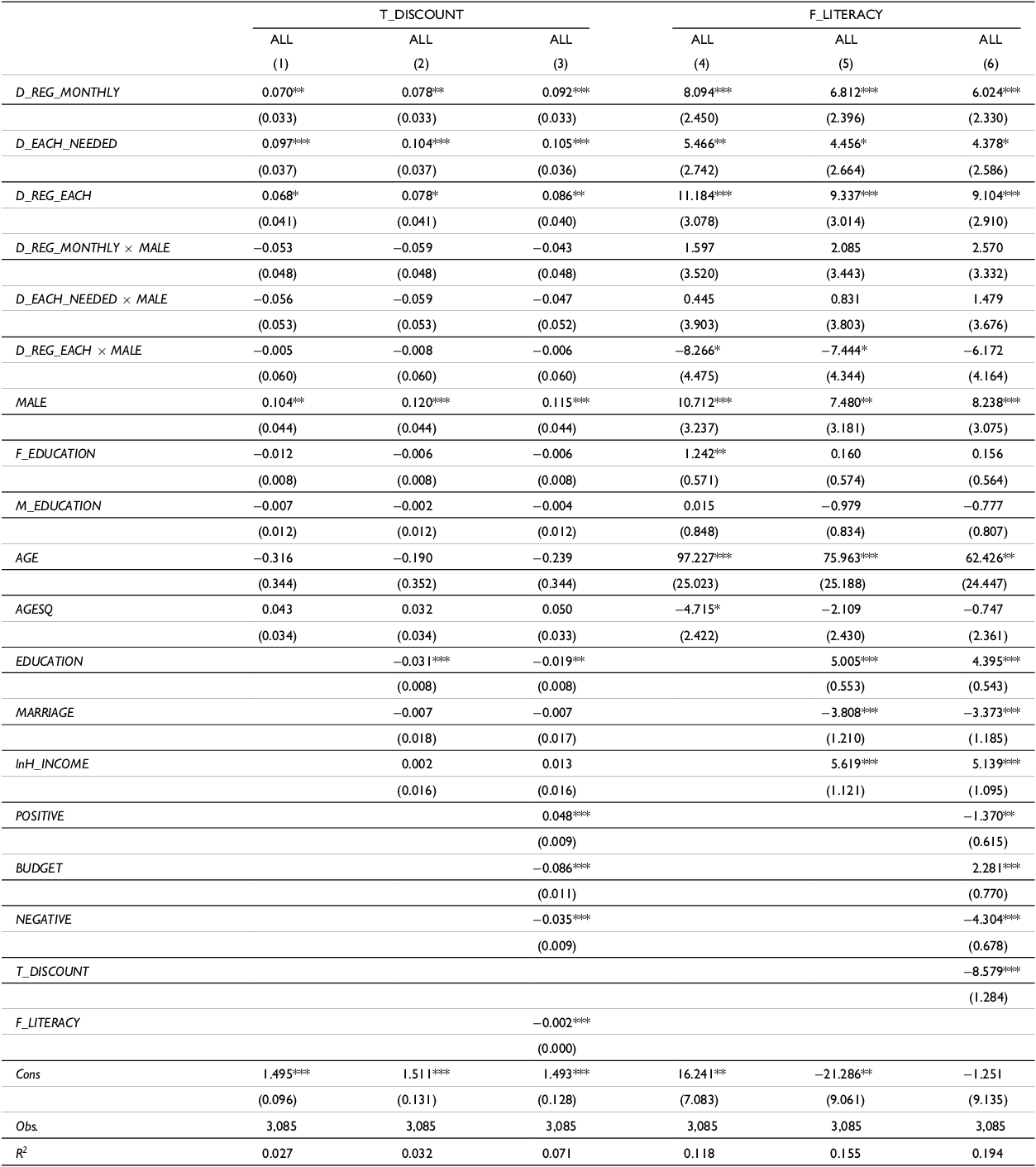

Tables 4 and 5 present the OLS estimation results for the three monetary attitude factors (POSITIVE, BUDGET, NEGATIVE), time discounting (T_DISCOUNT), and financial literacy (F_LITERACY), incorporating gender interaction terms with childhood allowance variables. Each outcome is estimated using three model specifications with progressively expanded sets of control variables.Footnote 14 The results are robust across specifications, showing consistent signs and levels of statistical significance for the childhood allowance variables.

Table 4. OLS results: allowance patterns and financial attitudes with gender interactions

The coefficients were estimated by OLS. Table 2 lists the definitions and units of each variable. The regression coefficients are presented in the upper rows. The prefecture dummies are included in the estimation but not shown here to save space. Robust standard errors are indicated in the parentheses. As the estimated coefficients are very small, the coefficients and standard errors for AGE are multiplied by 100 and AGESQ by 1000. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Table 5. OLS results: allowance patterns, time discounting, and financial literacy with gender interactions

The coefficients were estimated by OLS. Table 2 lists the definitions and units of each variable. The regression coefficients are presented in the upper rows. The prefecture dummies are included in the estimation but not shown here to save space. Robust standard errors are indicated in the parentheses. As the estimated coefficients are very small, the coefficients and standard errors for AGE are multiplied by 100 and AGESQ by 1000. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Regarding POSITIVE and BUDGET, neither the childhood allowance variables nor their interactions with the male dummy show statistically significant associations with these monetary attitudes. These results indicate that monetary attitudes are not substantially associated with childhood allowance experience, and no robust gender-specific patterns were observed.

In contrast, all three types of allowance are significantly and negatively associated with the NEGATIVE factor among females at the 5 percent significance level. This finding suggests that receiving any form of allowance during childhood is associated with less negative monetary attitudes in adulthood among women.

Although the interaction terms between the allowance variables and the male dummy are statistically significant in the NEGATIVE models, linear combination tests indicate that none of the total effects for males (i.e., the sum of the main and the interaction terms) are statistically significant (p > 0.1 in all cases).Footnote 15 This suggests that the significantly negative associations observed in the full sample are primarily driven by the female subsample.

These findings indicate that the relationship between receiving an allowance and monetary attitudes may differ by gender, partially supporting Hypothesis 1.

Next, we discuss the results for time discount preferences and financial literacy presented in Table 5. Regarding time discounting, all three types of allowance are positively and significantly associated with T_DISCOUNT. However, none of the interaction terms between allowance types and the male dummy are statistically significant. This suggests that the observed positive associations are primarily driven by females.

For financial literacy, all three types of allowance are also positively and significantly associated with F_LITERACY. Although the interaction term for D_REG_EACH×MALE shows a weakly significant and negative coefficient in Column (4) of Table 5, this association becomes statistically insignificant once additional controls are included. These findings suggest limited evidence for a gender difference in the association between childhood allowance and financial literacy.

When additional control variables are included, the signs and significance levels of the childhood allowance dummies remain consistent, confirming the robustness of the results.

Furthermore, several psychological and monetary attitudes are significantly associated with both time discounting and financial literacy. Specifically, T_DISCOUNT is negatively associated with BUDGET and positively associated with POSITIVE (Tables 4 and 5, Column (6)), suggesting that individuals with stronger present-oriented preferences tend to be less budget-conscious.

In addition, financial literacy is positively associated with BUDGET and negatively associated with both NEGATIVE and T_DISCOUNT (Tables 5, Columns (6) and (9)). These findings provide additional insights into how childhood allowance experiences relate to various financial attitudes and behaviors in adulthood.

3.3. Gender-specific factor structures and OLS results

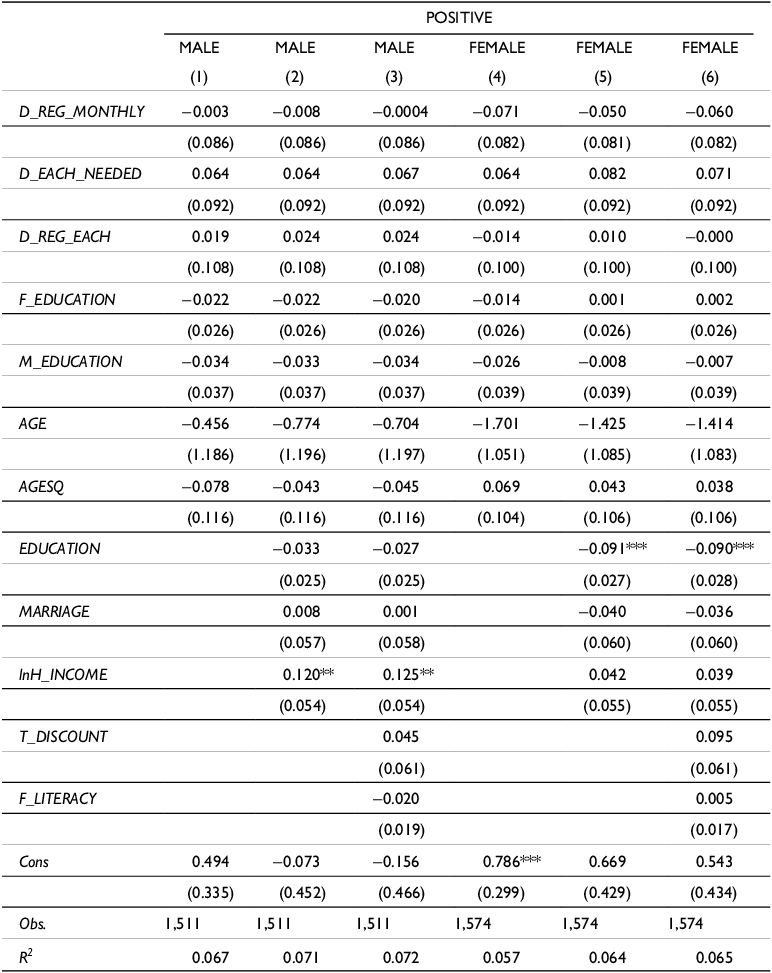

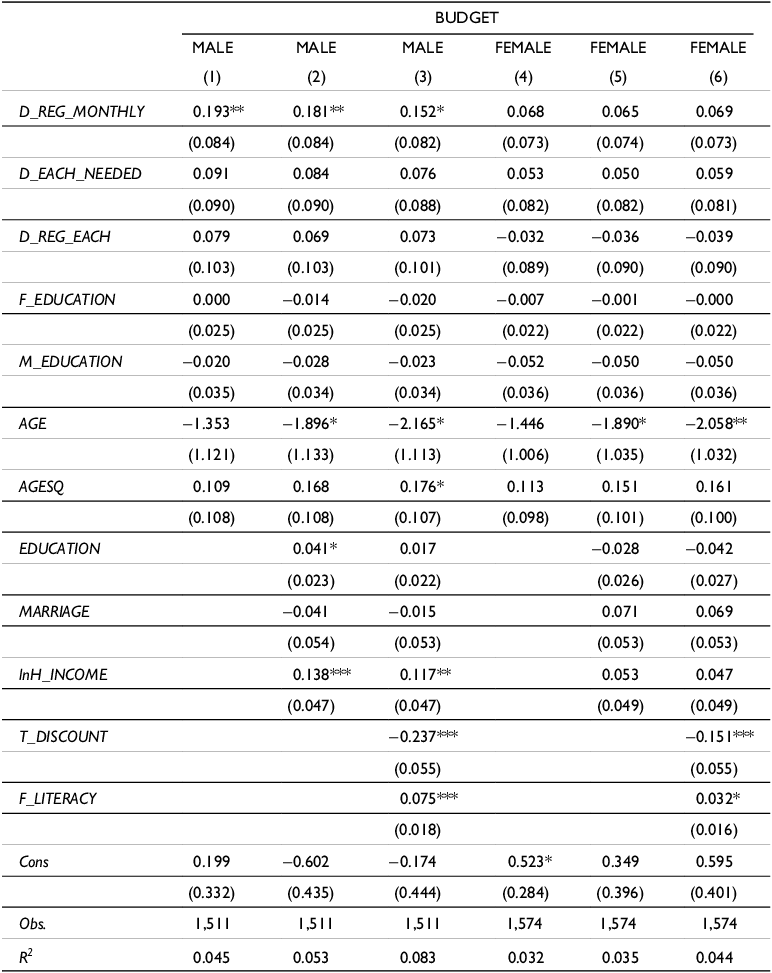

Building on the gender-specific factor structures presented in Table 1, we estimate separate OLS models for male and female respondents (Tables 6–10). These regressions examine the associations between childhood allowance types and each outcome variable – POSITIVE, BUDGET, NEGATIVE, T_DISCOUNT, and F_LITERACY – within each gender group. The estimation specifications include the same set of control variables as those used in the pooled models.

Table 6. OLS results: allowance patterns and POSITIVE monetary attitudes by gender

The coefficients were estimated by OLS. Table 2 lists the definitions and units of each variable. The regression coefficients are presented in the upper rows. The prefecture dummies are included in the estimation but not shown here to save space. Robust standard errors are indicated in the parentheses. As the estimated coefficients are very small, the coefficients and standard errors for AGE are multiplied by 100 and AGESQ by 1000. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Table 7. OLS results: allowance patterns and BUDGET monetary attitudes by gender

The coefficients were estimated by OLS. Table 2 lists the definitions and units of each variable. The regression coefficients are presented in the upper rows. The prefecture dummies are included in the estimation but not shown here to save space. Robust standard errors are indicated in the parentheses. As the estimated coefficients are very small, the coefficients and standard errors for AGE are multiplied by 100 and AGESQ by 1000. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

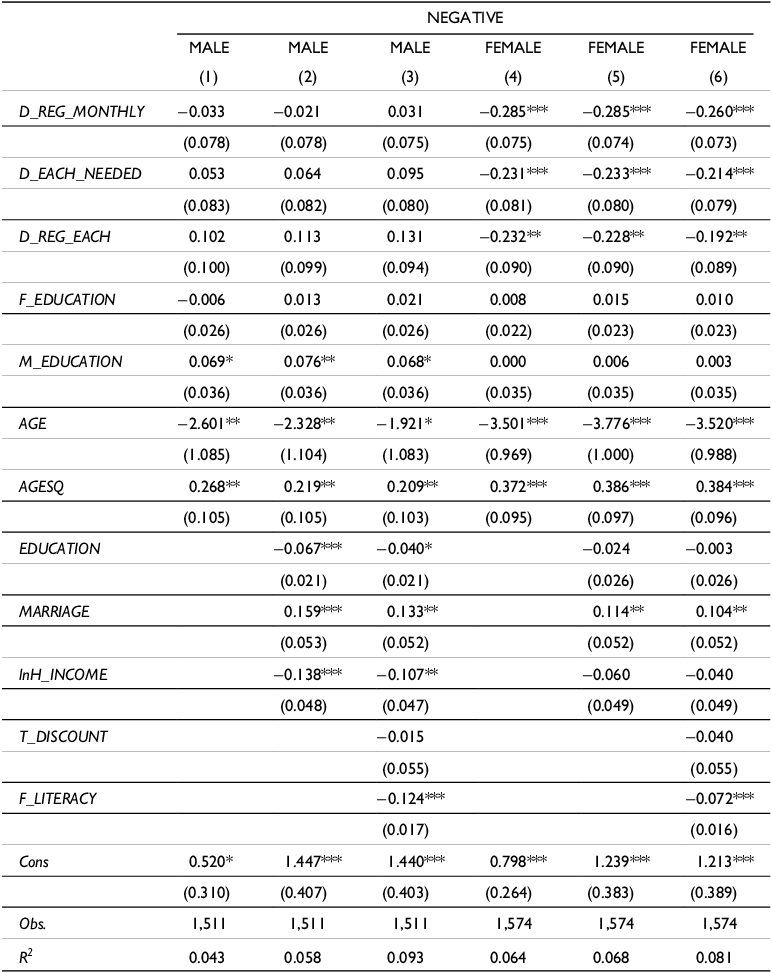

Table 8. OLS results: allowance patterns and NEGATIVE monetary attitudes by gender

The coefficients were estimated by OLS. Table 2 lists the definitions and units of each variable. The regression coefficients are presented in the upper rows. The prefecture dummies are included in the estimation but not shown here to save space. Robust standard errors are indicated in the parentheses. As the estimated coefficients are very small, the coefficients and standard errors for AGE are multiplied by 100 and AGESQ by 1000. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

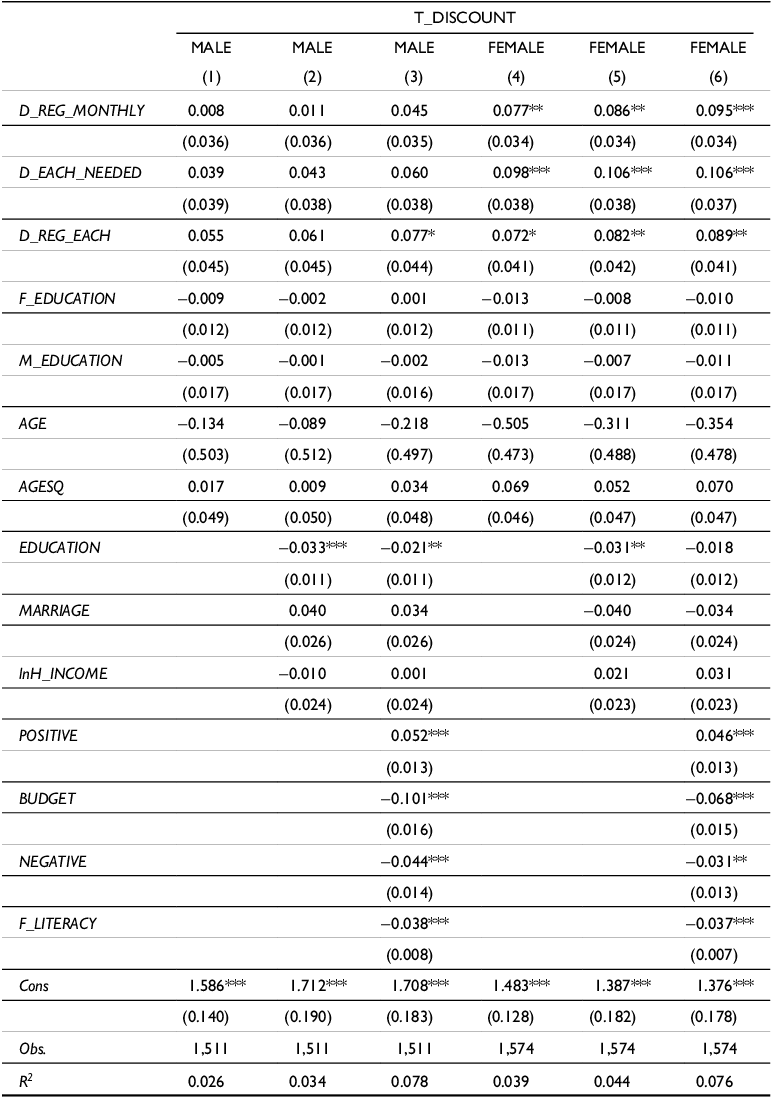

Table 9. OLS results: allowance patterns and time discounting by gender

The coefficients were estimated by OLS. Table 2 lists the definitions and units of each variable. The regression coefficients are presented in the upper rows. The prefecture dummies are included in the estimation but not shown here to save space. Robust standard errors are indicated in the parentheses. As the estimated coefficients are very small, the coefficients and standard errors for AGE are multiplied by 100 and AGESQ by 1000. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

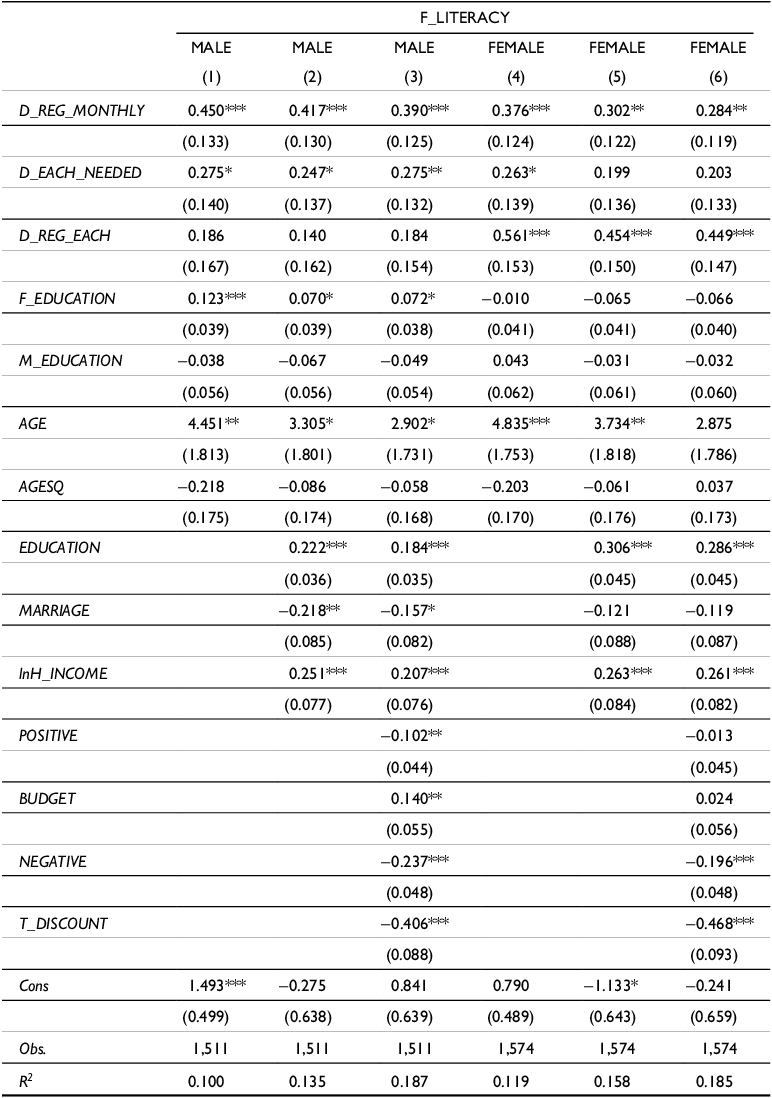

Table 10. OLS results: allowance patterns and financial literacy by gender

The coefficients were estimated by OLS. Table 2 lists the definitions and units of each variable. The regression coefficients are presented in the upper rows. The prefecture dummies are included in the estimation but not shown here to save space. Robust standard errors are indicated in the parentheses. As the estimated coefficients are very small, the coefficients and standard errors for AGE are multiplied by 100 and AGESQ by 1000. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

To highlight the most relevant patterns, we focus below on the statistically significant associations identified in the gender-specific OLS regressions. Full estimation results are presented in Tables 6–10.

Regarding BUDGET (Table 7), a positive and statistically significant association is observed between D_REG_MONTHLY and the BUDGET factor among male respondents, whereas no such association is found among females. These results suggest that Hypothesis 2 is supported for males but not for females.

In the case of NEGATIVE (Table 8), all three types of allowance are negatively and significantly associated with negative monetary attitudes among females. These findings are consistent with those from the pooled models and suggest that receiving any form of allowance in childhood is associated with lower levels of negative attitudes toward money in adulthood for women. No comparable associations are observed for males.

With respect to T_DISCOUNT (Table 9), all three types of allowance are positively and significantly associated with time-discounting preferences among female respondents. This suggests that the relationship between childhood allowance and time discounting differs by gender, with a clear and consistent association observed among females but not among males. However, contrary to Hypothesis 3, all types of childhood allowance were positively associated with time discounting among females, indicating a more present-oriented pattern rather than future-oriented behavior.

Turning to F_LITERACY (Table 10), D_REG_MONTHLY is positively and significantly associated with financial literacy scores for both males and females across all model specifications. For D_EACH_NEEDED, a significant positive association is observed among males, with the coefficient remaining significant at the 5 percent level in Column (3). In contrast, among females, the association is significant only in the baseline model and becomes statistically insignificant once additional controls are included.

Furthermore, for females, D_REG_EACH shows the strongest association with financial literacy, with large and statistically significant coefficients across all model specifications. This finding suggests that individuals who received an allowance both regularly and on an as-needed basis demonstrated the highest levels of financial literacy. Therefore, although these findings support Hypothesis 4 for males, the same hypothesis is not supported for females.Footnote 16

4. Discussion

Our analysis results offer valuable insights into the relationship between childhood allowance and financial outcomes in adulthood, with particular attention paid to gender differences. In addition to examining the overall associations between childhood allowance and financial attitudes, time-discounting preferences, and financial literacy in adulthood, it is important to explore the interactions of the independent variables. Therefore, in this section, we discuss our estimation results in the context of previous studies while also examining the interactions among the independent variables.

This study has three key findings. First, our results suggest that the relationship between childhood allowance and monetary attitudes varies by gender. While males receiving regular monthly allowances tended to have more disciplined budgeting habits, females receiving any form of allowance displayed enhanced positive monetary attitudes. This gender disparity in the association between childhood allowances and monetary attitudes underscores the importance of considering gender-specific factors in understanding financial behavior. Our study contributes to the existing literature on gender differences in monetary attitudes, which has been explored in previous studies (Furnham et al. Reference Furnham, Wilson and Telford2012; Gresham and Fontenot Reference Gresham and Fontenot1989; Tang Reference Tang1992). These studies have established that men and women often perceive money differently. Males tend to associate it more with cognitive factors such as achievement and power, while females view it as more emotionally charged and often experience more anxiety related to financial matters than males. This study extends this understanding by examining the specific influence of childhood allowance experiences on monetary attitudes. The observed gender disparity in the association of childhood allowances highlights the complex interplay between early financial experience and gender-specific attitudes toward money.

Second, our findings indicate a different relationship between childhood allowances and time-discounting preferences. Contrary to our expectations in Hypothesis 3, all types of childhood allowance were positively associated with time-discounting preferences among females. This finding suggests that receiving an allowance – regardless of its form – may have fostered more present-oriented financial habits rather than the ability to delay gratification. One possible interpretation is that receiving allowances during childhood, regardless of type, may have increased short-term consumption opportunities, which in turn shaped a stronger preference for immediate rewards in adulthood. Another possibility is that the presence of money during early years – without accompanying guidance on delayed consumption – might have weakened self-regulation over time. These findings imply that the mere act of receiving money may not be sufficient to cultivate future-oriented thinking unless it is accompanied by structured financial education or parental guidance, warranting further investigation.

Additionally, our regression results also indicate that negative attitudes toward money (NEGATIVE) are significantly and negatively associated with financial literacy for both males and females, while budgeting attitudes (BUDGET) are positively associated only among males (Table 10). Thus, childhood allowance may be indirectly associated with financial literacy through its relationship with time-discounting preferences, particularly among females. Understanding these potential pathways is crucial for designing effective interventions to promote financial literacy and responsible financial behavior from an early age.Footnote 17

Third, the association between childhood allowance and financial literacy differed between genders. While males who received a regular monthly allowance demonstrated the highest level of financial literacy, females who received both regular and as-needed allowances demonstrated the highest levels of financial literacy. We conducted tests to compare the allowance variables’ coefficients in Table 10. For the female group, among the three types of allowance patterns, only the difference between D_EACH_NEEDED and D_REG_EACH was statistically significant at the 10 percent level (F = 3.75, p = 0.0531). This suggests that receiving both regular and as-needed allowances may be differently associated with financial literacy compared to receiving only need-based allowances. No significant differences were observed between the other pairs. This difference implies that the combination of regular and need-based allowances may provide a more complementary financial learning environment, contributing more effectively to financial literacy than either form alone. Further research is required to fully understand the related implications. Exploring additional dimensions of childhood allowances, such as the amount received, duration of allowance provision, and allowance source (whether parents or grandparents), could provide a more comprehensive understanding of their influence on financial behaviors and attitudes in adulthood. Further investigation of these factors could uncover the underlying mechanisms by which childhood allowances shape financial literacy outcomes. This deeper understanding is crucial for developing targeted interventions to improve financial literacy skills among diverse demographic groups.

Taken together, these results underscore the pivotal role of early financial experiences such as childhood allowances in shaping individuals’ financial behaviors and attitudes throughout adulthood. Our findings suggest that receiving an allowance – without sufficient guidance – may foster present-oriented preferences, especially among females, which could partly explain the observed gender gap in financial literacy.

Understanding these mechanisms is essential for developing more effective financial education strategies that account for both early monetary experiences and gender-specific behavioral patterns.

5. Conclusions

This study examined how childhood allowance affects monetary attitudes, time-discounting preferences, and financial literacy in adulthood, with a specific focus on gender differences. Analyzing a survey from Japan, our study is unique in the following ways: First, it investigated the long-term association between childhood allowances and financial attitudes and behaviors in adulthood. Second, a separate factor analysis for male and female respondents uncovered potential gender-specific differences in financial attitudes and behaviors. Additionally, this study employed OLS models to estimate direct associations between key variables, without specifying structural mechanisms. This made it easier to estimate and interpret the model.

The OLS estimates revealed that receiving a regular monthly allowance was associated with good budgeting habits in males; for females, receiving any form of allowance was linked to less negative attitudes toward money.

The relationship between childhood allowances and time-discounting preferences varied by gender. While no significant association was observed for males, females who received any form of allowance tended to have higher time-discounting preferences than those who did not. Additionally, childhood allowance influenced financial literacy differently for males and females. For males, receiving a regular monthly allowance is associated with the highest increase in financial literacy. For females, receiving an allowance on a regular basis and each time as needed appears to be most strongly associated with financial literacy.

This study has limitations related to data quality. First, data regarding childhood allowance were self-reported, which introduces the possibility of memory bias. Additionally, our analysis focused solely on how individuals received their allowance during childhood without considering factors such as the amount or duration of the allowance. Future research could explore these additional dimensions to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between childhood allowance and financial attitudes and behaviors. Second, the survey data used here may have suffered from a sampling bias. This may limit our findings’ generalizability to a broader population.

There are also some methodological limitations. Despite efforts to control for confounding variables, such as parents’ education, there may still be omitted variables that influence the relationships under study. For example, other aspects of parental influence that were not captured here could affect both childhood allowance and financial outcomes in adulthood.

Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable insights into the long-term associations between childhood allowance and monetary attitudes and behaviors. Our findings emphasize the need for targeted interventions aimed at improving financial literacy skills among diverse demographic groups. Future research could explore additional dimensions of childhood allowances and investigate the complex interplay between financial literacy, time-discounting preference, and other socioeconomic factors to provide a more comprehensive understanding of individuals’ financial well-being.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/flw.2026.10007.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon request.

Acknowledgments

This study used microdata from the RISS at Kansai University. We would like to acknowledge RISS for providing the microdata and express our gratitude for the financial support from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Zengin Foundation for Studies on Economics and Finance, and ISHI Memorial Securities Research Promotion Foundation Research Fund for contributing to this research.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Chisako Yamane conducted literature searches, reviewed articles, analyzed data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Hiroyuki Aman and Taizo Motonishi commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by JSPSKAKENHI (grant number 23K01390, 21K01593), Zengin Foundation for Studies on Economics and Finance (1802), and ISHI Memorial Securities Research Promotion Foundation Research Fund (ISHI-2019-406).

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical standard

This study used anonymized microdata from RISS. The data were used in accordance with the ethical standards set by RISS and were anonymized to ensure participant privacy and confidentiality. All research activities complied with the relevant ethical guidelines and standards.