20.1 Introduction

In contemporary liberal democracies, there is a tension between the democratic element, which demands that the sphere of political decision-making be as large as possible, and the liberal component, which sees some rights as inherent and some norms as inviolable and therefore not open to debate. The tension exists not only because the majority may use the democratic process in a way that infringes on the rights of an individual or a minority, but also because constitutional provisions designed to divide the power between the branches of government and to protect human rights regulate the political process and limit the scope and content of political decisions.Footnote 1 Thus, as Wiktor Osiatyński puts it, ‘the more there is in the constitution, the less room there remains for democracy and for compromises within society and, consequently, the less power for parliament and more power for those courts in which constitutional claims are settled’.Footnote 2 However, one may also argue that this conflict exists not between constitutionalism and democracy but internally within constitutionalism itself. According to Paul Blokker, contemporary constitutionalism is informed by two conflicting imaginaries. A dominant modernist one sees constitutions as regulatory instruments which impose stability and order and are closely related to ideas such as state sovereignty, rational social engineering and universal norms and values. On the other hand, democratic imaginary is connected to notions such as self-government, autonomy, creativity and indeterminacy.Footnote 3 While the former vision serves as a base of legal constitutionalism, the latter imaginary is closely connected to its political counterpart.

According to some interpretations, Polish constitutional crisis can be seen as yet another example of the tensions between legal and political constitutionalism. Between 2015 and 2023, the Law and Justice government significantly altered the composition of the Polish Constitutional CourtFootnote 4 (PCT), the Supreme Court (SC) and the National Council of Judiciary and expanded the power of the executive branch in relation to the courts. Even though many Polish legal scholars saw this period as a time of ‘anti-constitutional populist backsliding’Footnote 5 during which the multidimensional assault on the rule of law caused Poland to become a constitutional pariah,Footnote 6 alternative interpretations were also present. Adam Czarnota claimed that the actions of the previous government could be seen as a ‘necessary adjustment of the system implanted in this part of the world after 1989’:Footnote 7 a change aimed at curbing ‘an excess of legal constitutionalism which was definitely anti-democratic in its nature’.Footnote 8 Thus, for Czarnota the crisis had a ‘democratic, emancipatory potential’: it was a turn towards political constitutionalism and a search for an independent constitutional identity promoting the rule of ‘a political nation’ and ‘dejuridization’ of the public sphere.Footnote 9 Other authors, even if they also explained the crisis in terms of the clash between the liberal and the political component of a democratic system,Footnote 10 did not share this optimism. As Maciej Pichlak aptly observed, this so-called democratization was superficial in nature and boiled down to bolstering the role of the dominant political actor. The citizens remained excluded from the political process, as their role was restricted to legitimizing the government through the elections.Footnote 11

A unique feature of the Polish constitutional crisis was that it also had a transitional justice dimension. According to Marcin Matczak, the previous government deeply mistrusted the 1997 Polish Constitution,Footnote 12 seeing it as an impunity instrument enacted in bad faith to protect the beneficiaries of communism from substantive justice using procedural justice as an excuse.Footnote 13 This mistrust had been even deeper with regards to the pre-2015 Polish Constitutional Court, which interpreted constitutional provisions as imposing certain limits on transitional justice measures. Because of the PCT case law in transitional justice cases, the Law and Justice leader Jarosław Kaczyński had dubbed the Court a bastion defending the post-transitional system in which the communist elite allegedly maintained power and privileges. His political group also coined the term ‘legal impossibilism’ which was generally used to refer to strict constitutional constraints supposedly stopping the parliamentary majority from introducing reforms necessary for the proper functioning of the state, including those that seek to overcome the legacy of the communist past.Footnote 14 The Supreme Court transitional justice rulings were subject to similar criticism. This critique was used by the Law and Justice government to justify the provisions reshaping the judicial branch, some of which were presented by their supporters as decommunization measures.Footnote 15 Regardless of whether these claims were rational or sincere, this rhetoric shows that the Polish rule of law crisis also had a strong transitional justice dimension.Footnote 16

In 2023, the Law and Justice party lost parliamentary elections to the democratic opposition led by the Civic Platform. Nevertheless, until now the new government has been unable to reverse most of the changes in the judiciary introduced by their predecessors – and, with the President and the PCT loyal to their political affiliates, the crisis lingers on. What is more, a true challenge is to find an answer to the constitutional backsliding which will stand the test of time, including future political changes. Thus, studying the roots of the Polish crisis remains relevant both domestically and internationally, as it can help to provide such a long-term, sustainable solution to the problem of constitutional backsliding.

In this chapter, I further explore the relationship between the Polish constitutional crisis and transitional justice. I begin with the analysis of the normative transitional justice framework of Polish legal constitutionalism. This is a fact-checking enterprise, which aims to verify the claim that constitutional restrictions in this sphere were so strict that they amounted to legal impossibilism. Next, I identify possible inspirations which may have informed the transitional justice constitutional framework in order to assess whether, as some scholars state, Polish constitutionalism simply imitated Western ideas. Finally, in order to trace the origins of the Polish constitutional crisis, I examine the spectrum of alternative transitional justice responses, including the ones supported by the previous government. In the end I claim that the belief in legal impossibilism in the transitional justice domain is rooted in a specific understanding of the objectives of political transition. According to the Law and Justice government, such a transformation must involve a fundamental change in social hierarchy, including an exchange of elites. The belief that liberal constitutionalism prevented this change served as one of the pillars of Polish conservative counter-constitutionalism.

20.2 Polish Transitional Justice Framework and Legal Impossibilism

In Poland, constitutional provisions related to transitional justice are scarce. A 1989 amendmentFootnote 17 to the 1952 Polish Constitution introduced the principle of democratic state governed by the rule of law and the principle of social justice to the legal system (this regulation was later repeated in the 1997 Polish Constitution). While the law also repealed provisions burdened with communist ideology, changed the name of the State and altered the national coat of arms, additional past-oriented provisions were not implemented until the new Polish Constitution was enacted in 1997. Its preamble refers to 1989 as a year when Poland regained ‘the possibility of a sovereign and democratic determination of its fate’ and recalls ‘bitter experiences of the times when fundamental freedoms and human rights were violated’ in Poland. The Constitution bans political parties and other organizations whose programmes are based upon totalitarian methods and practices of Nazism, fascism or communism (Article 13). It also includes the nullum crimen sine lege principle, but it states that this principle does not prohibit punishing acts which, while domestically legal, were crimes under international law (Article 42(1)). Finally, the Constitution stipulates that there is no statute of limitations for war crimes and crimes against humanity (Article 43) and that the period of limitation does not run when a crime committed by a public official in the performance of their duties is not prosecuted for political reasons (Article 44).

Due to the lack of more extensive constitutional regulations, it was down to the PCT to establish a normative framework with regards to dealing with the past. This is not an exceptional case: in post-communist countries a normative shift towards liberal democracy was to a large extent carried out through constitutional court’s rulings, and especially through their interpretation of the rule of law principle. This principle was incorporated into constitutions of almost all post-communist countriesFootnote 18 but, due to its general character, its precise meaning in each of the states had to be determined through constitutional adjudication.Footnote 19

That this meaning was in no way fixed is most evident in two well-known rulings of Eastern European constitutional courts, both related to laws lifting or prolonging statutes of limitation for criminal acts committed during the communist era and not prosecuted for political reasons. In 1992 the Hungarian Constitutional Court (HCC) declared such a provision unconstitutional.Footnote 20 Drawing on a somewhat paradoxical notion of ‘the revolution of the rule of law’, the HCC stated that: ‘A State under the rule of law cannot be created by undermining the rule of law. The security of the law based on formal and objective principles is more important than the necessarily partial and subjective justice’.Footnote 21 According to the ruling, ‘if the statute of limitations had run its course, the offender acquires the right as a legal subject not to be punished’Footnote 22 – and the rule of law demands that this trust in one’s impunity be protected. Therefore, lifting or extending the statute of limitations violates the principle of legal certainty, a core part of the formal aspect of the rule of law which must be protected even in the unique historical circumstances of transition.Footnote 23

On the other hand, a year later, the Czech Constitutional Court (CzCC) upheld a similar provision.Footnote 24 The CzCC relied on a more substantive understanding of the rule of law. According to the Court, even though the principle of legality is an important constitutional virtue, it should not be understood only formally: its interpretation and application should follow its purpose and respect democratic values. The rule of law cannot protect the impunity of communist perpetrators against just demands for their prosecution, as such an immunity would threaten the legitimacy of a new political system.Footnote 25

These two paradigmatic understandings of the rule of law can serve as a background against which the rulings of the PCT will be examined. This section concentrates on the PCT cases regarding the most salient areas of Polish transitional justice: lustration, the reduction of pensions and the prosecution of communist crimes. As I discuss in Sections 20.2.1–20.2.3, this analysis does not support the claim that legal impossibilism existed in the transitional justice sphere.Footnote 26

20.2.1 Lustration

The first judgment in which the PCT dealt with lustration was related to the 1992 parliamentary resolution ordering the Minister of Internal Affairs to present a list of top government officials, including members of parliament, who between 1945 and 1990 collaborated with the communist secret service.Footnote 27 This unverified list, which included the names of sixty-six people, was leaked to the press. Its publication led to the downfall of the Jan Olszewski coalition government, part of which was Kaczyński’s Centre Agreement Party. The resolution itself was invalidated by the PCT on both formal and substantive grounds.Footnote 28 On the formal level, the act was found to be unconstitutional due to violations of parliamentary procedure, the lack of statutory form and the vagueness of its provisions. This last flaw – together with the absence of procedural guarantees for the accused – was also found to violate the rule of law due to its impact on individual rights. According to the PCT, the above defects meant the resolution itself, regardless of the way it was applied, ‘threatened to violate human dignity’ by not protecting personal rights.Footnote 29 Thus, formal aspects of the rule of law were seen as guarantees of the more substantive ones. Still, the requirements introduced in the ruling were very basic and rather easy to fulfil by law-makers.

In 1997, Polish Lustration LawFootnote 30 was passed with the votes of the agrarian Polish People’s Party, liberal Freedom Union and social-democratic Labour Union. In contrast to Czech or German regulations, which banned certain categories of people – such as top government officials, members of the communist party or those tied to communist secret police – from holding specific positions in democratic public life (‘decommunization’), Polish lustration has been devised as a historical clarification mechanism. Those subject to lustration are, therefore, required to submit a statement on whether they were officers or employees of the communist secret service or knowingly and secretly collaborated with it. Only if this declaration proves to be false, the lustration liar is banned from holding certain public positions. Even though in 2006 the Law and Justice government enacted new, broader lustration law,Footnote 31 the vetting model remained virtually unchanged.Footnote 32

In 1998 the PCT upheld the constitutionality of the 1997 Lustration Act, invalidating only two minor provisions.Footnote 33 The Court stated that lustration is generally consistent with both the rule of law and international standards, as long as its goal is to protect democracy and human rights and not to punish those with a communist past. However, in order to comply with the rule of law, lustration provisions must be precise and the procedure needs to protect the rights of an individual.Footnote 34 To ensure such protection, the Court formulated a binding definition of collaboration: it had to be, inter alia, secret, conscious and real.Footnote 35 Thus, merely signing a declaration of collaboration was not sufficient: there had to be proof of an actual cooperation, whether fruitful or not. This definition directly influenced the outcomes of many lustration cases. It protected those who, despite having been listed in the archives, had in fact never cooperated with the communist secret service. Yet, as many of the files had been destroyed in 1989, it also introduced an evidentiary threshold that may have been impossible to meet even in the case of some real collaborators.

In 2003, the PCT invalidated an amendment enacted by the government of the post-communist Democratic Left Alliance and the Labour Union which had altered the definition of collaboration in a way that it no longer covered, gathering or providing data as a part of intelligence, counterintelligence and border protection tasks. As the internal structure of the communist secret service was heavily complicated, it is notoriously difficult to distinguish those duties from the actions targeting democratic opposition. According to the PCT, this ambiguity violated the rule of law’s formal requirements, as the vetted had no straightforward way to assess whether their actions had fallen within the scope of the statutory exception: from their point of view, the outcome of lustration proceedings could not be foreseen. Thus, the PCT yet again invalidated a provision due to the possible infringement of the rights of the vetted; interestingly though, the ruling meant that the definition of collaboration expanded significantly.Footnote 36 Finally, in a manner similar to its Czech counterpart, the PCT claimed that the continuity of the Polish State after the democratic transition did not mean that the axiological basis of the State and its legal system remained unchanged. On the contrary, the 1989 constitutional amendment discussed above was direct proof of a clean break with the past on the axiological level.Footnote 37 Even if this part of the judgment seems rather detached from the rest of the arguments, it shows dedication to a more substantive understanding of the rule of law.

The PCT’s judgment on the 2006 Lustration Act (enacted by the Law and Justice government) is by far the most thorough review of the Polish lustration regulations up to date. In 2007, the PCT invalidated a large part of the law. The Court reiterated that lustration can be consistent with the rule of law, as long as its goal is to protect democratization and human rights, the restriction of individual rights is proportional and the procedural guarantees are met.Footnote 38 However, many provisions were found to breach exactly these principles, while other infringed on equality or the right to informational self-determination.Footnote 39 According to the PCT, the act also violated formal aspects of the rule of law. Many provisions were invalidated because their imprecision or arbitrary nature infringed on the principle of proper legislation.Footnote 40 The principle was also violated by regulations which gave no discretion to disciplinary courts in choosing how to punish lustration liars and ordered their removal from legal professions: the PCT argued that, without such discretion, the power of a disciplinary court is merely a façade.Footnote 41 Finally, an amendment to the 1998 Act on the Institute of National RemembranceFootnote 42 (IPN) was found to have breached the requirement for a law to be public. Its provisions ordered the publication of a catalogue of communist secret service agents and collaborators, but their categories could not be properly understood without using secret instructions of communist security agencies, which cannot be treated as a source of law.Footnote 43 The PCT’s extensive reasoning in this case became a core of Polish acquis constitutionnel with regards to lustration: while this framework was widely accepted among liberal and left-wing social actors, the ruling was heavily criticized by the Law and Justice politicians and their supporters. It was also after this judgment that the term ‘legal impossibilism’ started to be used in the public discourse by the political right. However, even though the PCT framework was indeed robust, lustration was still possible: for instance, although the Court restricted lustration to the public sphere, its scope was still broader compared to pre-2006 regulations.

Finally, in 2015 the PCT deemed the absence of a duty to waive judicial immunity before launching lustration proceedings unconstitutional. The Court claimed that the lustration of judges is an instrument of ensuring their high moral standards and judicial independence, both necessary for the rule of law and human rights protection. However, as launching lustration proceedings marks the vetted with a social stigma, judicial independence cannot be protected if these are instigated without due consideration – and the need to waive judicial immunity is a tool to ensure such restraint.Footnote 44

The PCT case law shows an ongoing tension between the demands for lustration, understandable in a young democracy, and the need to ensure that this process is carried out in line with the rule of law. While the PCT stressed in each ruling that lustration is fully compatible with the rule of law, it also used its judgments to create an acquis constitutionnel in this regard. This framework was often based on formal aspects of the rule of law, due to their direct impact on the protection of individual rights. The PCT also sought to ensure that lustration did not restrict these rights in a disproportionate way. While the framework created by the Court was comprehensive and detailed, it did not render lustration impossible. In fact, this framework was even more permissive regarding other transitional justice measures, to which I now turn.

20.2.2 Reduction of Pensions

On 1 January 2010, a statute enacted by the Civic Platform and the Law and Justice Party lowered retirement pensions of former communist security service officers and members of the Military Council of National Salvation (WRON), a military junta which ruled the country during the 1981–1983 martial law. In the case of the former group, the pensions were reduced for each year of service in the communist security forces, while the pensions of WRON members were decreased for each year of army service starting from 8 May 1945.Footnote 45

The reduction was challenged before the PCT, which in its 2010 judgment upheld the law, finding only one provision partly unconstitutional. According to the PCT, the actions of WRON and communist secret police were fundamentally inconsistent with current constitutional values and the lawmaker had a right to reduce unjust retirement privileges enjoyed by their former members.Footnote 46 As recalculated pensions were on average still higher than the average ordinary pension – and therefore (high) above the social minimum – the Court decided that the law was proportional and did not infringe on human dignity or the core of the right to social security.Footnote 47 The act did not impose collective responsibility either: it was not repressive, as it involved no sanctions, but merely revoked privileges.Footnote 48 It was also consistent with the equality principle, though with one exception: the PCT decided that the reduction of pensions of WRON members for the years of army service prior to the martial law was discriminatory and unconstitutional as, in those years, future junta members did not differ in any way from other professional Polish soldiers.Footnote 49

Finally, the law did not violate the doctrine of acquired rights. According to the PCT, even if an officer of the communist secret service passed the 1990 vetting and subsequently served in a similar agency in post-transitional Poland, this fact did not guarantee that the pensions for their service between 1944 and 1990 would remain intact. The retirement privileges were acquired unjustly and were, therefore, not protected: as the Court noted ‘guarantees of impunity and economic privileges granted by the dictatorship for service in institutions and bodies which used repressions cannot be treated as an element of justly acquired rights’.Footnote 50 Taking away those privileges did not violate the principle of legal certainty either: between 1989 and 2009 the parliament repeatedly condemned the crimes of martial law, the communist secret service and communism itself, and the 2010 reduction of pensions could hardly have been a surprise.Footnote 51 The constitutional principle of social justice warranted the reduction of pensions: the PCT stressed that, in a democratic state governed by the rule of law, service in pre-transitional state institutions which violated human rights cannot justify claims to maintain retirement privileges.Footnote 52 Therefore, according to the PCT, by reducing these unfairly acquired privileges in a proportionate manner, the lawgiver ‘acted justly’.Footnote 53

In contrast to the Hungarian Constitutional Court, which focused on the protection of legal certainty and acquired rights (regardless whether they were acquired justly), the PCT based its ruling on more substantive considerations, including a resort to justice itself, in a manner somewhat similar to its Czech counterpart.

20.2.3 Prosecution of Communist Crimes

Article 9(1) of the Transitional Provisions to the Polish Criminal CodeFootnote 54 stated that the statute of limitations for intentional offences against life, health, liberty or the administration of justice, punishable by prison sentences exceeding three years, which had been committed by public officers in the performance of their duties between 1944 and 1989, had started to run anew on 1 January 1990. Article 9(2) of the same act stipulated that any amnesties or indemnity acts enacted before 7 December 1989 did not apply to the perpetrators of these crimes. The latter provision was challenged before the PCT. Much like the Czech and Hungarian courts in the cases discussed earlier in this section, it had to assess the extent to which a democratic state can use legislation to overcome obstacles to punishing the perpetrators of pre-transitional crimes.

In 1999, the PCT upheld the provision. According to the Court, the lex retro non agit principle did not prohibit from revoking an amnesty. The principle demanded that a person be punished only for an act which constituted an offence at the time it was committed; anything that happened after this point, including repealing an amnesty, was outside its scope. Therefore, the culprit had no right to remain unpunished.Footnote 55 However, even if such a right had existed, the contested regulation would have constituted ‘a statutory provision necessary in a democratic state governed by the rule of law for the protection of its security, public order, and public morals, which demand ending the impunity of perpetrators of crimes protected by a totalitarian state’.Footnote 56 Just like its Czech counterpart, the PCT understood public morals as ‘a trust of citizens towards the state: towards its officials and towards the law it enacts, [the law] which binds both the citizens, regardless of their positions, and the State itself’.Footnote 57 Moreover, making the punishment of such perpetrators possible satisfied the constitutional principle of social justice, as it removed systematic injustice from the criminal law.Footnote 58 On a personal level, repealing such an amnesty also served human dignity, which demands that all people were treated equally and impartially. In a rather mysterious passage, the PCT claimed that ‘justice which is present while combating impunity should be free of biased interests and forms, and of random force; it should be a justice which punishes but does not avenge. In this sense, justice is stronger even than law’.Footnote 59

Even though both Hungarian and Polish constitutional courts based their rulings on the lex retro non agit principle, their interpretation could not differ more. The PCT rejected the wide understanding of the principle rooted in the struggle for legal certainty. Even though it did stress the importance of non-retroactivity of criminal law, the Court interpreted the principle in a narrow way. This allowed the PCT to refer directly to the principles of substantive justice: an approach somewhat similar to the one chosen by the Czech Constitutional Court.

20.2.4 The Question of Legal Impossibilism

In an op-ed published shortly after the 2007 PCT lustration ruling, Krystyna Pawłowicz – who four years later would become a Law and Justice member of parliament and in 2019 a PCT judge – criticized the judgment, calling it an example of the ‘judicial review of the ruling party’s political programme’. For Pawłowicz, invalidating a provision due to its conflict with a general clause (such as the rule of law) meant that the ruling was not based on strictly legal criteria but rather on an assessment of legislation’s goals, subjective and dependent on the ‘worldviews and sympathies’ of the judges. As most of them were appointed by the opposition, Pawłowicz believed that the PCT could be used to ‘overturn any important legislation enacted by a democratically elected majority’, thus preventing ‘the part of society that won the election from exercising power’ and undermining the democratic nature of the Polish political system.Footnote 60 This belief in legal impossibilism is echoed in a 2011 book Poland of Our Dreams, in which Kaczyński also accused the PCT of illegitimately expanding its authority through the abuse of general clauses.Footnote 61 For Kaczyński, this constitutional case law was an aspect of a deeper crisis, in which wide judicial interpretative powers transform the rule of law into the rule of lawyers, and an obligation to base government actions on an explicit statutory basis was a ‘specific type of legalism which ultimately leads to impossibilism’.Footnote 62 There was a popular belief that transitional justice is one of the spheres in which these limitations were especially strict.

The above analysis does not support this claim. Polish constitutional provisions did not generate any explicit transitional justice restrictions, save perhaps the prohibition of retroactive criminal sanctions. Even though the PCT rulings in lustration cases did create a robust constitutional framework which significantly restricted the scope of lustration, introduced procedural guarantees and created a high evidentiary threshold through the definition of collaboration, in no way did they make lustration impossible. On the contrary, the Court constantly reaffirmed that lustration itself was fully compatible with the rule of law. What is more, the judgments regarding the pre-2015 legislation on the reduction of pensions and the revoking of amnesties were highly permissive and resorted to substantive justice in order to justify these regulations. Thus, a relative leniency of Polish transitional justice and its general concentration on civil and political rights instead of economic ones – with minor and late exceptions regarding the reduction of retirement privileges and compensation for victims – had more to do with the lawmakers’ restraint (and some of the Supreme Court rulingsFootnote 63) than the judgments of the PCT.

Official statistics also confirm that transitional justice was possible. Up to 30 June 2021 nearly 125,000 out of circa 466,000 lustration statements were examined, out of which around 13,000 were questioned. Final rulings were announced in 2,144 court cases and in 1,446 of them the statement was proven to be false.Footnote 64 As for the 2010 reduction of pensions, 38,563 decisions on their recalculation were issued; in 7,227 cases the pensions remained unchanged.Footnote 65 In addition to some early high-profile criminal cases, between 2000 and 2020 exactly 370 criminal proceedings were initiated against 558 people accused of communist crimes, out of which 162 were found guilty.Footnote 66 While this last number is arguably low, this had less to do with constitutional limitations and more with the inefficiency of criminal trials in general. Other pre-2015 transitional justice initiatives included the dissolution of the communist secret service, granting the access to its files, rehabilitation of former political prisoners, compensation for victims and memorialization.Footnote 67 Thus, Polish reckoning with the communist past was in general rather broad, even if it was also quite lenient.

From this perspective, the popular claim that the transitional justice framework imposed by the PCT was so strict it amounted to legal impossibilism seems more like a myth than an honest and disinterested assessment of Polish acquis constitutionnel. In Section 20.4, I argue that the belief in legal impossibilism among the members and supporters of the Law and Justice party stems from a particular (and controversial) interpretation of transition’s major objectives. Before I move to this point, I first address another popular claim: that Polish transitional justice framework was simply a copy of standards developed in the West.

20.3 Transitional Rule of Law Framework: Inspirations

In this section, I use PCT judgments to identify potential inspirations which may have informed the transitional justice framework developed by the Court.Footnote 68 Contrary to popular beliefs, their minor role and increasingly adaptive use does not support the claim that Polish constitutionalism was a mere imitation of Western rule of law requirements.

20.3.1 Sources of Inspiration

In its transitional justice case law, the PCT referred to four kinds of documents which can be regarded as external sources of inspiration: (1) international soft law; (2) foreign legislation; (3) ECHR decisions, ECtHR judgments and rulings of other constitutional courts; and (4) literature on transitional justice and human rights.Footnote 69

In its 2010 ruling on the reduction of pensions, the PCT invoked international soft law – including resolutions and declarations of OSCE, the European Parliament and the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly (PACE) – to present a universal condemnation for the crimes of communism and common belief in the need to deal with its legacy in accordance with the rule of law.Footnote 70 Legislation of other CEE countries and non-domestic rulings (ECHR decisions, ECtHR and German Constitutional Court judgments) were used by the PCT to provide a wider context of the legislation.Footnote 71 In lustration cases, the PCT referred to the ECtHR case law to strengthen its arguments that lustration laws should meet a legislative threshold expected from penal regulations,Footnote 72 to argue that lustration of public figures does not violate their right to privacy,Footnote 73 to claim that publication of lustration statements without a prior court judgment does not breach the right to fair trialFootnote 74 and to comment on the temporary nature of lustration measures.Footnote 75 To prove this last point, the PCT also mentioned a Czech Constitutional Court judgment,Footnote 76 while a ruling of German Bundesverfassungsgericht was used to underline the importance of personal rights protection.Footnote 77 Finally, the PCT occasionally quoted transitional justice and human rights literature, mostly to remark on the nature of the implemented mechanisms and the position of victims and perpetrators.Footnote 78

These documents played relatively minor roles in the PCT reasonings and seem to have been used only as additional sources of argumentation. None of them were used in more than two rulings. In this regard, they differ significantly from a 1996 PACE resolution, to which the PCT routinely referred in lustration cases, and which I explore now.

20.3.2 PACE 1996 Resolution and Guidelines

On 27 June 1996 the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly adopted a resolution on transitional justice in post-communist states.Footnote 79 The resolution and the attached guidelinesFootnote 80 outlined the rule of law requirements that should be met by transitional justice measures, including criminal trials, lustration, restitution and reduction of pensions.

PACE soft law played an important role in the PCT lustration judgments. In 1998, the Court explicitly stated that ‘when it comes to lustration, constitutional requirements and, in particular, basic conditions of a democratic state governed by the rule of law, should be interpreted according to, inter alia, the aforementioned Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly resolution’.Footnote 81 In 2007, the PCT explained that, even though the resolution is not legally binding, the Court should take it into account while interpreting both the statutes and the Constitution.Footnote 82 The Tribunal also referred to these documents to argue that the goal of lustration measures is to protect democratic institutions and that lustration is therefore a temporary measure.Footnote 83 Finally, the PCT relied on the resolution and guidelines to articulate many of the requirements that lustration laws should fulfil: their individual application, protection against political misuse and providing the vetted with full procedural guarantees, such as the right to a fair trial, the right to defence and the presumption of the lustration statement’s truthfulness.Footnote 84 The PCT reasoning in the 2007 ruling – which, as it was mentioned, is now considered a core of Polish acquis constitutionnel with regards to lustration – begins with a list of such requirements. This list, which covers thirteen short paragraphs,Footnote 85 is in fact a translation, either direct or indirect, of fragments of PACE 1996 Resolution and Guidelines, although no footnote is provided by the Court.Footnote 86

However, the resort to these acts is not unproblematic. PACE 1996 Resolution defines lustration as a process which aims to ‘exclude persons from exercising governmental power if they cannot be trusted to exercise it in compliance with democratic principles’.Footnote 87 Thus, lustration is understood as a mechanism of banning certain groups of people from holding public offices because of their involvement with the previous regime. This is understandable, as in 1996 most lustration laws, including the Czech and German ones, did involve such a disqualification. However, Polish lustration was created a year later as an instrument of historical clarification and did not involve sanctions for work or collaboration with the communist secret service; sanctions were imposed only for a lustration lie. Thus, some parts of the resolution and guidelines quoted by the PCT seem rather ill-fitted when it comes to Polish lustration. For instance, when lustration belongs to a historical clarification model, it seems out of place to claim that a state governed by the rule of law ‘has sufficient means at its disposal to ensure that the cause of justice is served and the guilty are punished’, that ‘[p]ersons who ordered, perpetrated, or significantly aided in perpetrating serious human rights violations may be barred from office’ and that there is ‘a need for an individual, and not collective, application of lustration laws’.Footnote 88 On the other hand, these conditions fit perfectly if lustration involves a ban on holding public offices, as in the Czech Republic.

These differences may be the reason why the PCT consciously omitted or modified some of the PACE guidelines to adjust them to Polish circumstances. First, the guidelines suggest that lustration should be administered by a special independent commission, that it should be restricted to non-elective positions of high importance – such as top government offices, law enforcement, security agencies and the judiciary – and that it should not be imposed on people who acted under compulsion.Footnote 89 The PCT did not mention these recommendations and Polish lustration does not follow them either: it is conducted by courts (an arguably higher standard), it covers a wider array of public positions, including elective offices, and demands that even individuals who acted under compulsion confess to collaboration. Second, the guidelines recommend a rigorous lustration timeframe: vetting should take into account only acts conducted after 1 January 1980, the disqualification from office should not be longer than five years and lustration measures should end no later than 31 December 1999, as by that time new democratic systems should be consolidated.Footnote 90 In its 2007 ruling, the PCT acknowledged that lustration should end when a democratic system is firmly established and that sanctions imposed in the process should last only for a rational time, but no specific dates were given.Footnote 91 The court also ignored the 1980 threshold and, in fact, Polish lustration covers employment, service and collaboration dating back to 22 July 1944. Finally, the guidelines advise that conscious collaborators should be vetted only if their actions actually harmed others and if this result was predictable.Footnote 92 On the other hand, the PCT claimed that lustration is permissible if collaboration is clearly defined by a statute and is verified in a proper procedure.Footnote 93 While the collaboration definition was introduced by the PCT in its 1998 ruling, it did not demand that the information provided by the individual cause the others any actual harm. To establish that collaboration took place, its real, genuine character was sufficient.

While some may argue that these differences suggest that the PCT’s dedication to the rule of law was selective at best, another interpretation is possible. Restricting the number of those affected by lustration and introducing a rigorous vetting timeframe is arguably more important when lustration involves a ban on holding public offices – an important exception to otherwise equal rights to participate in democratic public life. Yet, these constraints are less crucial when lustration is not a decommunization measure but a transparency mechanism sanctioning only those who lack the integrity to speak openly about their past. Thus, one may argue that, while the PCT took the resolution and its guidelines genuinely into account, the recommendations were adapted to fit a local context: a specific model of Polish lustration.

20.3.3 Between Imitation and Adaptation

According to some authors, the lack of knowledge on how constitutionalism, democracy and the rule of law work in practice was the reason why Polish transitional constitutionalism did not create its own independent form based on a local identity, but rather concentrated on a ‘mindless imitation of the West’ using ‘solutions [known] from books’ and resulting in ‘careless’ constitutional transplants.Footnote 94 This criticism seems similar to claims made by Kaczyński himself, who believed that legal impossibilism was created inter alia by transplanting conceptions aimed at tempering the communist system to the democratic one,Footnote 95 and who scolded Polish academia for its alleged peripherality, lack of intellectual independence and willingness to reproduce foreign ideas.Footnote 96

In the field of transitional justice such an imitative approach would surely mean a strict application of all the formal rule of law requirements, in a manner similar to the 1992 Hungarian Constitutional Court ruling. As Wojciech Sadurski points out,

The universalistic liberal ideal was used as a yardstick to judge the preparedness of the new democracies to join first the Council of Europe, and then the European Union. Western European political elites developed a stake in the integration of the ex-Communist East into the overarching political structures of the continent, not least for the sake of stability and peace in Europe. The criteria of ‘normal’ democracy, untainted by any extraordinary measures related to its immediate non-democratic past, were instrumental in achieving these aims.Footnote 97

Nevertheless, many Polish scholars were well-aware of the problems faced when the rule of law is applied in a country undergoing a major political change. Suggestions that justice should have been done first, and that the introduction of the rule of law to the Polish legal system was, therefore, premature, were relatively rare.Footnote 98 Yet, even among those who believed that the transition (and transitional justice) had to be carried out in accordance with the rule of law, there were scholars who claimed that inconsistencies existing within the transitional legal system may deem fulfilling all the rule of law requirements impossible. This, however, did not release the lawmaker from an obligation to respect basic standards of the rule of law.Footnote 99 Apart from two radical solutions – to completely reject the rule of law for the time being or to strictly follow all its requirements – a more moderate response was also possible.

The PCT’s use of the PACE 1996 Resolution and Guidelines suggests that, in a similar manner, aside from a ‘mindless imitation’ of the Western constitutionalism and from creating a wholly independent one, there was also a third way: an adaptation of the rule of law framework to local circumstances. It is true that many constitutional ideas and practices were imported to Poland from the West. Yet, the way in which the PCT adapted the PACE resolution and guidelines to local conditions seems to indicate a certain dose of autonomy. It also suggests that, to a certain degree, the Polish transitional justice framework was increasingly adaptive over time instead of merely imitative. This conclusion is further supported by PCT rulings on revoking amnesties and reduction of pensions which have departed far from a formalistic understanding of the rule of law.

More research is needed to verify whether this adaptive technique was also used outside the transitional justice domain. However, if the rule of law requirements are understood as a part of (imported) legal tradition, it may be argued that some level of adaptation is always more probable than sole imitation. Even if an interpreter is dedicated to adhering to the tradition they received (as the PCT definitely was), the need to apply it to the case at hand is likely to cause modifications and their character may be the result of the local legal tradition.Footnote 100 While this process may happen unintentionally, it may also be a conscious one, as in the case of the Polish transitional justice framework.

20.4 Transitional Justice Alternatives: Political Transformation as an Exchange of Elites

Despite an array of implemented transitional justice measures, there is a widespread belief that reckoning with the past was not possible due to the restrictive constitutional framework created by the PCT through the transplantation of Western rule of law standards. In Sections 20.2 and 20.3, I have argued that legal impossibilism conceived in this way is a myth and that the use of the rule of law framework by the PCT was, to a certain degree, adaptive, instead of purely imitative. However, among the members and supporters of the former government the belief in legal impossibilism in the transitional justice context is based on a specific understanding of the core objectives of political transformation. According to this way of thinking, the process of democratization must also involve a significant change in social hierarchy, including an exchange of elites. To illustrate this way of thinking, I now turn to the alternatives to the Polish transitional justice model, which were possible both at the level of constitutional adjudication and constitutional provisions themselves.

20.4.1 Dissenting Opinions

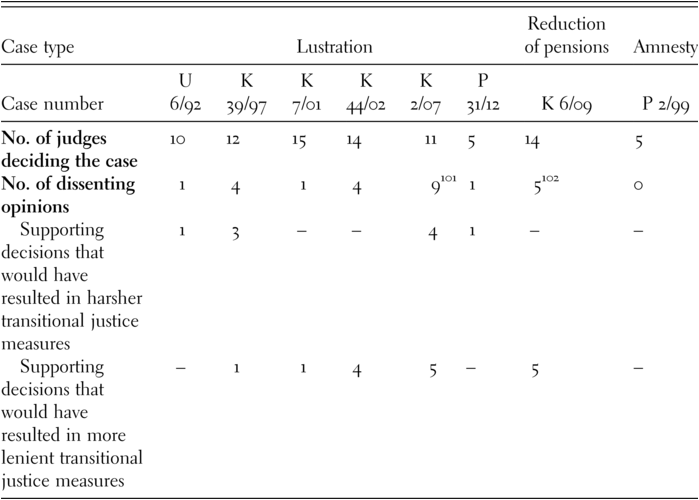

Transitional justice cases are as important, as they are notoriously hard. They involve dilemmas of not only a legal but also a moral and political nature. Therefore, one may expect that many of the constitutional judgments in transitional justice cases will not be unanimous. Table 20.1 proves that this is indeed the case when it comes to the PCT rulings.

Table 20.1 Dissenting opinions in the PCT transitional justice rulings

| Case type | Lustration | Reduction of pensions | Amnesty | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case number | U 6/92 | K 39/97 | K 7/01 | K 44/02 | K 2/07 | P 31/12 | K 6/09 | P 2/99 |

| No. of judges deciding the case | 10 | 12 | 15 | 14 | 11 | 5 | 14 | 5 |

| No. of dissenting opinions | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 9Footnote 101 | 1 | 5Footnote 102 | 0 |

| Supporting decisions that would have resulted in harsher transitional justice measures | 1 | 3 | – | – | 4 | 1 | – | – |

| Supporting decisions that would have resulted in more lenient transitional justice measures | – | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | – | 5 | – |

Some of the dissenting opinions indicate that, in the case of lustration, harsher reckoning with the communist past was possible. In these opinions judges often referred to substantive values, including justice itself. A separate opinion to the PCT judgment on the 1992 parliamentary resolution questioned the Court’s assumption that its application had to violate the personal rights of those included on the list of communist secret service collaborators. According to Judge Łączkowski, this conclusion could not be defended on ‘neither legal nor ethical grounds’: if information on past collaboration was accurate, it could not harm a good name of former agents – and, even if it would, ‘ethical reasons, as well as the principles of justice and equality, suggest that defending the rights of the repressed should be a priority’.Footnote 103 In the 1998 ruling three opinions defended the constitutionality of a provision ordering a removal of a lustration liar from the list of presidential candidates through an administrative act of an election committee. One of the judges argued that a lack of such sanction would violate public morality and the principle of the rule of law. Allowing a lustration liar to become the president would be fatal for the authority of state institutions – ‘a principal value in a state governed by the rule of law’. Thus, ‘rule of law procedural values’ cannot be contrasted with necessary personal virtues: honesty, integrity and respect for the law and fellow citizens. The first virtue is especially important as ‘the respect for the government and the law has always relied on truth’.Footnote 104

Four dissenting opinions defended constitutionality of the major part of the 2006 Lustration Law. Some of the judges claimed that the PCT was too eager to interfere with the relative autonomy of the legislator. Even when such an intervention was warranted, constitutionality of many provisions could easily be obtained through their binding interpretation.Footnote 105 What is more, two opinions demonstrated a more substantive understanding of the rule of law. According to them, a democratic state not only needs appropriate state institutions but it also ‘needs to be based on clear axiological and moral standards’.Footnote 106 Thus, in such a state, ‘the legislator has a duty to deal with a difficult past for the good of society’ and to ensure proper operation of state institutions: lustration laws can be instruments of this change, if they are based on virtues such as truth, memory, human dignity and freedom.Footnote 107 According to Judge Liszcz, these exceptional transitional circumstances ‘justify the need for a gradation and more liberal application of constitutional constraints’ designed for stable democracies. This is because, as the time passes, ‘dealing with the past in a manner that is fully consistent with all constitutional requirements will be more and more difficult, if at all possible’.Footnote 108

However, dissenting opinions also show that Polish transitional justice could have been much more restricted. A separate opinion to the 1998 PCT judgment claimed that, because of the social stigma associated with the ties to the communist secret service, the need to confess to such connections is equal with self-denunciation and therefore contrary to the rule of law.Footnote 109 If this opinion prevailed, the Polish model of lustration would not be possible. Subsequent dissenting opinions questioned overall constitutionality of lustrationFootnote 110 or that it also covered individuals who did not partake in core activities of the communist secret service.Footnote 111 Finally, five dissenting opinions claimed that the 2010 reduction of pensions was unconstitutional. According to the judges, officers who in democratic Poland passed the 1990 vetting and were re-employed in security agencies had a right to expect that their pensions would remain intact. Therefore, the law violated their vested rights, legal security and trust towards the state, which are all protected under the rule of law. The opinions also argued that the act lacked individualization, was disproportionate and infringed on the principle of proper legislation.Footnote 112

The authors of these opinions preferred an even stricter constitutional framework. According to Judge Zdziennicki, transitional justice regulations need to comply with all the rule of law requirements, as ‘there are no special constitutional provisions for dealing with people associated with the former system of government’.Footnote 113 His own list of acceptable solutions seems relatively short and does not include the politics of memory: in another ruling Zdziennicki claims that ‘the law, by its very nature, cannot impose a specific vision of the past and draw legal consequences from such an assessment’.Footnote 114 Whether this neutrality is observed or not, the rule of law requirements need to be fulfilled in order to safeguard individual rights. Thus, Judge Jamróz warns against pursuing justice at the expense of the rule of law:

I do not accept … adjudication which relies on ‘pure’ social justice and is inspired by political and moral convictions, but which disregards constitutional principles developed in the Court’s jurisprudence, [the principles] which reflect modern, well-established standards of a democratic state governed by the rule of law. This method creates a risk of turning the Tribunal from a court of law to a court of social justice.Footnote 115

Comparing the number of judges with the number of dissenting opinions suggests that, if the composition of the PCT’s adjudicating panels was partially different, some of the Court’s pivotal decisions (including the ones in transitional justice cases) may have gone in another direction. This trivial truth explains why altering the personal composition of judicial branch was such an important factor in the Polish rule of law crisis. If one ‘sees people rather than institutions’ then reshaping the judiciary ‘is not an attempt to repair and strengthen the institutions … but above all to change the cadres’.Footnote 116 As Jarosław Kaczyński himself explained: ‘To change Poland, one needs the right people’.Footnote 117

20.4.2 Alternative Constitutional Provisions

Transitional justice provisions are not abundant in the 1997 Polish Constitution, and they were similarly absent in its drafts prepared by political actors.Footnote 118 One significant exception was Article 29 of the constitutional draft submitted by Kaczyński’s Centre Agreement Party, which stipulated that a statute may provide an exemption from the nullum crimen sine lege principle with regards to acts which in a particularly severe way violated basic human rights and the rights of the Polish Nation.Footnote 119

On the other hand, the so-called civic draft of the constitutionFootnote 120 – prepared by experts, financed and managed by the Solidarity trade union and signed by over one million of peopleFootnote 121 – included many transitional justice provisions. Article 26(2) ordered lustration of public officials and candidates for office. Article 161(1) stated that the provisions enabling re-privatization should be enacted within a year after the Constitution came into force. The same deadline was set for passing a statute on the vetting of judges (Article 163). Article 164 provided for a transfer of communist secret service files to the IPN and ordered that a law regulating access to them be adopted within a six-month period. However, only one provision made its way to the final text of the 1997 Constitution: Article 22 of the draft stated that there would be no statute of limitations for war crimes and crimes against humanity and that the proscription period would not run when a crime was not prosecuted for political reasons (see Articles 43 and 44 of the Polish basic law).

The popular draft is fondly remembered by the Law and Justice party. In 2017, a conference celebrating the alternative constitutional draft was held in the Polish Senate. In an opening speech, Kaczyński criticized the 1997 Polish Constitution, calling it ‘post-communist’ and accusing it of petrifying the existing social structure. On the other hand, the Law and Justice leader praised the popular draft. According to Kaczyński, it included ‘an ingenious idea’ which made it ‘fundamentally different’ from the current Polish constitution: through its transitional justice provisions, the draft was effectively ‘abolishing post-communism’, in a way that ‘made it impossible to use the law for blocking such changes’.Footnote 122

In fact, two Law and Justice constitution drafts – prepared in 2005 and 2010 – included some similar provisions. They both proclaimed the right to obtain information about the communist regime and individuals involved in its actions, tasked the IPN with fostering this right and provided for lustration. Both drafts also banned individuals who eagerly fought against the democratic opposition from holding public offices, while the later one also explicitly introduced a ten-year period for vetting of judges. Finally, the 2005 draft ordered that a Truth and Justice Commission be created for a period of five years. The task of this commission was to investigate and disclose abuses of public positions occurring after 1989 in the interest of an individual or a group – a striking example of a mistrust towards the early years of the Polish democratic system.Footnote 123

20.4.3 Tuning the Piano: Transitional Justice and the Transformation of Social Hierarchies

The 2005 and 2010 Law and Justice drafts suggest that, for this party, ‘abolishing post-communism’ must involve removing the former elite from important positions in a democratic system. Without such a change, transitional justice is incomplete. Kaczyński makes this point in his 2011 book, describing four aspects of a successful transition: he states that, while Poland was able to build democracy and capitalism, the lack of decommunization meant that it failed to create ‘a new state’ and ‘a new social hierarchy’.Footnote 124 Kaczyński describes the Round Table Agreements as the birth of the new post-communist elite, composed of the former members of communist nomenklatura – who during the transition either acquired or remained in control of a large part of national property – and some members of the democratic opposition. According to the Law and Justice leader this meant that, after 1989, the old elite maintained much of their control over Polish political and economic life.Footnote 125 Kaczyński seems deeply convinced that the lack of decommunization slowed down crucial reforms: he claims that, if such a vetting would have taken place, ‘the GDP would be higher by circa 25 percent’, ‘more flats would have been built’ (he estimates the difference at two million!), the budget for higher education would be a couple of times bigger – and even that ‘more children would have been born’.Footnote 126 Therefore, for the Law and Justice leader, the lack of thorough screening is one of transition’s biggest mistakes and some kind of retrospective vetting is still necessary to reshape the social order.Footnote 127

In order to ensure their effective and fair operation, such a vetting should cover inter alia state offices, security agencies, mass-media, banks and courts.Footnote 128 While this does not necessary mean a total purge, in order to induce social change the vetting should be both broad and deep. According to Kaczyński:

Power is a system of relations between people. If these relations are disrupted and those below are from a different faction than the ones in charge, then it may be said that the keys of the piano cannot reach to the strings. One plays from a new music sheet, but hears an old melody. This is how many institutions, including the television, work today. … This is why until this day it is no difference who plays the piano, because whatever they would play – what we hear is The Internationale.Footnote 129

Thus, for the Law and Justice leader, ‘the replacement of personnel is necessary to restore the agency of the state, especially in the judiciary’.Footnote 130 For Kaczyński, decommunization is crucial for inducing a transformation of the whole social hierarchy: it is a tool for an essential exchange of the public elite. It is only after such an exchange that political, economic and social transformation is completed.Footnote 131

However, according to the former government, such a transformation was not possible under the 1997 Polish Constitution and the PCT case law. In 2011 Kaczyński claimed that, in order to vet the judges, a constitutional amendment would be necessaryFootnote 132 and that ‘an ostentatious screening’ conducted by the Truth and Justice Commission ‘could have been easily invalidated by the PCT’.Footnote 133 It is therefore no coincidence that the Polish constitutional crisis began with the conflict between the government and the PCT and that, during the same period, many decommunization provisions were also enacted.Footnote 134 This is because, under closer scrutiny, legal impossibilism turns out to have a very particular meaning: in the context of political transformation it is understood as a restriction on the fundamental rearrangement of the social hierarchy – an interpretation very much rooted in specific beliefs about the core objectives of democratic transition.

It is true that a widespread disqualification of former communist elites has never been implemented in Poland. However, is the belief that such a process was impossible under Polish transitional justice framework justified? Even though no definite answer can be given, one should note that, in 1990, vetting procedures were carried out with regards to the SC and to the former communist secret service, both resulting in significant personnel changes. While these regulations were not subject to constitutional review, there is no reason to believe the PCT would have held them contrary to the rule of law: in fact, the PACE 1996 Resolution and Guidelines explicitly allowed for such measures. Yet, as the years since the transition go by, it becomes more difficult for such provisions to pass the proportionality test. Thus, when the Law and Justice came to power in 2005 and 2015, it may have indeed been too late to introduce such a disqualification in a way consistent with constitutional requirements. Still, even if this proved to be true (which we shall never know), the lack of decommunization should still be considered mainly a result of the lawmakers inactivity, for which the PCT can hardly be blamed. From this perspective, legal impossibilism is, at best, unproven – and possibly a myth as well.

20.5 Conclusions: Legal Impossibilism and Polish Counter-Constitutionalism

In her chapter on constitutional sociology, Kim Lane Scheppele describes successful constitutions as ones which ‘manage to create their own social life’.Footnote 135 Such constitutions reach beyond legal domain and are able to dominate social imaginary: they ‘shape social expectations and understandings, and come to be taken for granted’.Footnote 136 Scheppele understands constitutions as ‘fields of naturalised ideas’:Footnote 137 as long as they seem obvious and are unquestioned, even a serious economic or political crisis does not threaten the constitutional order. It is when a constitution is ‘fundamentally challenged’ and its ‘reality becomes questionable’ that social actors need to adjust the rules ‘to rescue its normality’: ‘[i]f they fail – or if they fail to try – constitutions can crumble’.Footnote 138

Constitution can become denaturalized through ideological competition. This competition is caused by counter-constitutions, defined by Scheppele as ‘alternative visions of constitutional order, grounded in different understandings of what a constitution is and should be’ which ‘reject the taken-for-granted constitutional vision already in place’.Footnote 139 Scheppele attributes the collapse of Hungarian liberal constitutionalism to the emergence of such a counter-constitutional narrative. This narrative presented the 1989 constitution as foreign, offered an alternative constitutional symbol (the Holy Crown of St Stephen, allegedly a ‘true’ Hungarian constitution) and created its own politics of memory.Footnote 140 Scheppele explains that:

Had the counter-constitutional ideas not been around to provide a ready-to-hand alternative conceptual frame, the 1989 constitution might have been harder to topple. But once an alternative constitutional conception came to be seen as legitimate by segments of the Hungarian population, it became impossible for the 1989 constitution to naturalise the political space any longer. The dominant constitutionalism ceased to hold, and the post-1989 constitutional order became easy to destroy because it was no longer accepted as real.Footnote 141

In the vast literature on the Polish constitution crisis, theories as to what caused the decline of liberal constitutionalism in this country differ significantly. The answers given by Polish scholars are varied and include factors as different as the need for group identification, globalization and economic disparities, the fear of the migration crisis and the dominance of legal positivism.Footnote 142 Many authors agree, however, that the lack of an entrenched democratic culture is one of the reasons of the crisis.Footnote 143 While this may well be true, there is also an alternative explanation to consider: that a liberal vision of a political order was well-entrenched but became denaturalized when Polish counter-constitutionalism emerged.

Just like their Hungarian counterparts, Polish conservatives created an alternative constitutional imaginary. An alternate narrative on Polish democratization was formulated, in which the Round Table Agreements and ensuing peaceful transformation were presented not as a historical achievement, but as the original sin of the post-transitional social order: the birth of the new elite, composed of prominent members of the democratic opposition and the former communists. In this vision, the fact that the latter have been able to participate in democratic public life is not a liberal virtue, but proof that the transition was mainly superficial: a true transformation would have to include a fundamental change in social hierarchy, including an exchange of political and economic elites. According to counter-constitutionalists, this was unfortunately not possible, as the 1997 constitution (enacted by the new elite and infused with foreign ideas), the PCT and the rest of the judiciary guarded the post-transitional political, economic and social structure. One of the ways in which they allegedly defended the system was the abuse of general clauses, including the rule of law. In this narrative, the constitutional order was designed to create a state of legal impossibilism, in which social hierarchies would remain intact. Thus, the belief in legal impossibilism which prevented the vetting of public sphere (including the judiciary) is central for this understanding of Polish transition. This interpretation serves to delegitimize liberal constitutionalism and to simultaneously present an alternative, in which the cadres are more important than the institutions and the procedures, and the exchange of elites becomes a prerequisite of a just and efficient state. While the Law and Justice counter-constitutionalism looks for alternative constitutional tokens (such as Solidarity’s popular draft) and political symbols (such as the deposition from power of the Olszewski’s government), it is ultimately also forward-looking, and promises a new, fair social order.

The role which the PCT and the courts play in this counter-constitutional vision explains why the implementation of the Law and Justice project began with changes in the personal composition of the judicial branch. There is, however, another lesson to be drawn from the analysis of Eastern European counter-constitutionalism – and one especially important for the governments which seek to reinstate the rule of law. While it is tempting to look for straightforward, legal solutions to the constitutional crisis, these may not be sufficient in the long run. If Scheppele’s diagnosis is right, then, in order to respond to counter-constitutionalism in a permanent way, its narrative needs to be denaturalized and an alternative constitutional vision has to be present. While this vision may include a return to liberal constitutionalism, its imaginary has to be sufficiently deep to re-inspire and altered enough to make up for its previous deficits; it must also include its own politics of memory. This is a huge and daunting task but, from the perspective of constitutional sociology, a small-scale constitutional project may simply not be possible.