Climate change is probably the most important challenge the world is facing today. Heat waves, deforestation, drinking water shortages, crop failures and floods are just some of the serious consequences that threaten life on the planet (IPCC, 2022). In Western European politics, the issue structures party competition to a considerable extent. Green parties as ‘owners’ of the issue are advocating far‐reaching measures to stop the emission of greenhouse gases but also centre‐right and centre‐left mainstream parties are pressured to develop a climate protection agenda. In this context, there is a growing body of scholarship analysing how the electoral strength of ‘niche parties’ – those advocating a particular issue such as green parties promoting environmental issues – influences the programmatic positions or discourses of established parties (Abou‐Chadi, Reference Abou‐Chadi2016; Meguid, Reference Meguid2005). Spatial theories of party competition and issue competition theory assume that mainstream parties respond to public opinion shifts, such as increasing electoral support for green parties, by copying their position and by engaging in the issue. As vote‐seekers, mainstream parties need to respond to voters' demands, and if global warming is what voters are worried about, then it may be electorally unwise to ignore it.

We know, for example, that mainstream parties become more sceptical of multiculturalism and immigration in the face of electoral successes of radical right parties promoting an anti‐immigration and nativist agenda (Akkerman, Reference Akkerman2015; Bale et al., Reference Bale, Green‐Pedersen, Krouwel, Luther and Sitter2010; Schumacher & van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and Van Kersbergen2016; Van Spanje, Reference Van Spanje2010). The impact of green parties as ‘niche’ competitors ‐ advocating an environmentalist agenda ‐ on mainstream parties is a more controversial issue (Abou‐Chadi, Reference Abou‐Chadi2016; Spoon et al., Reference Spoon, Hobolt and Vries2014). This is particularly true for positions on climate protection. While existing studies and datasets provide information on environmental orientation (Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022; Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2021), they offer little data on parties’ explicit climate agendas. Thus, we are still confronted with a lack of empirical knowledge on the conditions that lead mainstream parties to become more climate‐friendly. Furthermore, while existing studies on mainstream parties’ environmentalist agendas take green party success into account, they do not consider another variable that is expected to have a particularly strong impact on parties: public opinion on the issue (Fagerholm, Reference Fagerholm2016). In this sense, this study provides an elaborated test of existing theories of party behaviour by including new independent variables and a new empirical contribution by specifically measuring climate‐related references.

This article steps into the research gap of niche parties’ influence on mainstream parties’ positions and emphasis on global warming by conducting content analyses of 292 election manifestos from liberal, centre‐right and centre‐left parties in 10 Western European countries from 1990 to 2022. OLS regression analyses are used to estimate the impact of green parties’ electoral success, the public salience of environmental and climate issues, and other factors commonly associated with mainstream parties’ policy shifts.

The findings support the overarching assumption that mainstream parties respond to public opinion by increasingly adopting climate protection stances – but not to green parties’ electoral success. Besides the public salience of green issues, the findings are interpreted in the sense that the Fridays for Future (FFF) movement has made a very significant difference. It is particularly during the 2019–2022 period when climate became a dominant issue in election manifestos. Incumbent status has no effect on the emphasis on climate protection standpoints. The findings question the niche‐party thesis, as green parties only have a significant impact when we do not control for public opinion. The article further questions the current measurement of niche parties’ success as an independent variable in party research and offers an alternative.

Mainstream parties’ policy shifts and climate protection

Whether and why mainstream parties change their behaviour in the face of external pressure has been the subject of numerous debates and empirical studies in the last decades. For the purpose of this study, we need to reflect on mainstream parties’ positions on climate protection and the factors which may change them or trigger an increased engagement in the issue. While the classical Downsian spatial theory focused on party competition in two‐party systems (Downs, Reference Downs1957), more recent theoretical models take multiparty systems into account and – important for this study – political issues instead of the general left–right placement of parties (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005; Spoon et al., Reference Spoon, Hobolt and Vries2014). Election campaigns are often focused on specific issues, and parties consciously decide on which issues to compete on in elections (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005). This is also in line with issue competition theory (Carmines & Stimson, Reference Carmines and Stimson1986; Green‐Pedersen & Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2015; Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996; Walgrave & de Swert, Reference Walgrave and de Swert2007), which focuses on the question ‘which political conflicts will be translated into issues on the political agenda’ (Meijers, Reference Meijers2017). Issue competition literature, as well as Meguid's model, share the crucial assumption that mainstream parties react to new issues by shifting their positions and issue emphasis (Green‐Pedersen & Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2015; Meijers, Reference Meijers2017; Spoon et al., Reference Spoon, Hobolt and Vries2014; Van Spanje, Reference Van Spanje2010).

A determining factor that puts specific issues on the political agenda – for example, climate change – and thereby influences mainstream parties’ positional behaviour are considered so‐called niche‐parties which ‘own’ a specific issue. A popular example are populist radical right parties and their emphasis on (anti‐) multiculturalism and (anti‐) immigration but also green parties which are considered owners of environmentalist issues (Abou‐Chadi, Reference Abou‐Chadi2016). As soon as these parties experience electoral breakthroughs, mainstream parties need to react to their issues. Since mainstream parties are seen as rational vote‐ and office‐seekers, they respond to new issues in ways that are likely to strengthen, or at least not to weaken, their electoral performance. Meguid (Reference Meguid2005) mentions three respective strategies that mainstream parties can choose when dealing with new issues and the rise of niche parties. First, they can address the issue by copying the position of the niche party or moving in that direction. This is what Meguid calls ‘accommodative strategy’. Second, parties can address the issue – that leads to an increased issue emphasis (‘salience’) as in the first option – taking the oppositional stance questioning the standpoint of the niche party (‘adversarial strategy’). Last, mainstream parties can refuse to talk about the issue following a ‘dismissive’ strategy.

According to Meguid (Reference Meguid2005), the most promising strategy is the accommodative one, because it undermines the issue ownership of the niche party. Voters now have the choice between two options. When in doubt, voters would opt for the mainstream party since it can rely on ‘legislative experience and governmental effectiveness’ and is perceived as more competent to take action (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005, p. 349). Since mainstream parties have more access to the media and a larger voter base, they can publicly promote their position establishing ‘name‐brand recognition’ (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005, p. 349).

The theoretical expectation that mainstream parties adopt the issues and positions of niche parties has been tested increasingly within the last years. A large number of studies are engaged in identifying the impact of radical right niche parties on mainstream parties’ positions on multiculturalism and immigration and mostly find that established parties indeed become more nativist or nationalist (Abou‐Chadi, Reference Abou‐Chadi2016; Akkerman, Reference Akkerman2015; Bale et al., Reference Bale, Green‐Pedersen, Krouwel, Luther and Sitter2010; Schumacher & van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and Van Kersbergen2016; Van Spanje, Reference Van Spanje2010).

Regarding the effect of green niche parties on mainstream parties’ positions, we know rather little. Abou‐Chadi (Reference Abou‐Chadi2016) could not identify any link between green parties’ success and mainstream parties’ environmentalist agendas based on data from the Marpor project (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2021). Again, using Marpor data, Spoon et al. (Reference Spoon, Hobolt and Vries2014, p. 372) found, instead, that ‘parties raise the stakes of the green issue within their electoral manifestos when the green party was electorally successful in the previous election’.Footnote 1 Furthermore, the ideological closeness of non‐green to green parties was identified as an important factor. Left parties are more prone to adopt green issues than right‐wing parties. In contrast to the two articles cited above, some studies explicitly measure positions on climate protection of political parties (Båtstrand, Reference Båtstrand2015; Carter & Clements, Reference Carter and Clements2015; De Blasio & Sorice, Reference De Blasio and Sorice2013). Yet, they all focus on a specific period and on a restricted sample of parties. The so far most extensive measurement of parties’ climate positions comes from Carter et al. (Reference Carter, Ladrech, Little and Tsagkroni2018) using manual content analyses of party manifestos in Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy and the United Kingdom. However, even this study is restricted in its scope and number of cases and – more importantly – does not address the question of what influences climate positions of mainstream parties.

So why should we further investigate shifts in mainstream parties’ green agendas given the existing studies? Most scholars tested the impact of green parties on other parties’ environmentalist agendas but not on the salience of the climate issue and respective positions. This might be due to the simple reason that no existing dataset collects information on parties’ agendas on global warming for a large number of countries and years. The Marpor project, on the other hand, provides constantly updated data for all Western European countries but does not distinguish between climate protection demands and environmental positions (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2021). Similarly, the Chapel Hill group only provides information about parties’ positions and salience towards environmental sustainability (Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022). Unlike environmental protection – such as protecting rivers, forests and animals – climate change is sometimes considered a positional rather than a valence issue. Parties’ positions tend to vary and seem to be more polarised on climate change depending, for example, on left–right positioning (Lockwood, Reference Lockwood2018; Farstad, Reference Farstad2018). But even if we theoretically assume that mainstream parties behave similarly on climate and environmental issues, empirical research is needed to provide evidence for theoretical assumptions. This is particularly important, given the ambiguous findings of existing studies on parties’ environmental behaviour (Abou‐Chadi, Reference Abou‐Chadi2016; Spoon et al., Reference Spoon, Hobolt and Vries2014).

Last, existing studies on the determinants of mainstream parties’ environmental agendas have ignored a crucial factor associated with mainstream parties’ policy shifts: the public salience of environmental issues. As argued by a variety of scholars, it is not just the success of niche parties but also the salience of specific issues among the public that leads parties to emphasise certain issues (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006; Fagerholm, Reference Fagerholm2016). In this sense, this study is a first attempt to include public opinion as a variable in the study of mainstream parties’ environmental behaviour.

Hypotheses

But what exactly are the conditions that could lead mainstream parties to emphasise the climate issue (salience) and to adopt positions to fight global warming (position)? I distinguish between factors inside and outside the party system. Starting within the party system – and as elaborated above – the success of niche parties owning the climate issue (green parties) should be associated with issue engagement and demands for climate protection among the mainstream. Speaking with Meguid (Reference Meguid2005), this is the electorally more promising strategy than ignoring the issue. Yet, Abou‐Chadi (Reference Abou‐Chadi2016) is sceptical regarding this reasoning. He assumes that green parties are not only associated with environmental issues (associative dimension) by the public, but the latter perceives green parties also as able to handle environmentalist problems (competence dimension). For mainstream parties, this means that talking about environmental issues bears ‘the risk that politicization of the environment issue will cause partisan realignment in favor of green parties’ (Abou‐Chadi, Reference Abou‐Chadi2016, p. 422). Considering mainstream parties as vote‐seekers, they should refrain from addressing these issues so as not to contribute to the visibility and salience of environmental problems. However, this dismissive strategy should be difficult to conduct. As argued by Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen (Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2015), parties are often forced to address issues of niche parties since the media and institutionalised debates in parliaments pay attention to them and demand statements from politicians. Since ignoring the issue is almost impossible in practice, it may therefore be more successful for mainstream parties to portray themselves as the fighters against global warming and as a competent and experienced political force. H1 is therefore formulated as follows:

H1: The higher the success of green parties, the more mainstream parties emphasise the climate issue adopting protective positions.

Another party‐system related factor is ideological proximity. There is considerable empirical evidence that mainstream parties are more responsive to actors from the same ideological family as they compete for similar voter groups (Abou‐Chadi, Reference Abou‐Chadi2016; Adams & Somer‐Topcu, Reference Adams and Somer‐Topcu2009; Green‐Pedersen & Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2015; Spoon et al., Reference Spoon, Hobolt and Vries2014). A shift towards a radically different position may not only be less successful in attracting new voters, but may further cause vote losses from the core constituency (Green‐Pedersen & Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2015; Walgrave & de Swert, Reference Walgrave and de Swert2007). It could be argued that decelerating climate change is a less contested demand. However, especially centre‐right parties compete with the populist radical right, which often opposes measures to fight climate change representing a considerable share of climate‐sceptic voters (Huber, Reference Huber2020; Lockwood, Reference Lockwood2018). In order to not lose potential voters to the populist right, the centre‐right may refrain from loudly communicating a climate agenda, while centre‐left parties rather compete with green and leftist parties and could benefit from climate protection stances.

Furthermore, parties on the economic right – conservatives and liberals – may respond less positively toclimate protection than left‐wing parties, because the former are more sceptical towards economic regulations and state interventionism that climate measures often require (Farstad, Reference Farstad2018). In this sense, I expect that the centre‐left is more prone to adopt climate issues and to position itself in favour of respective measures than the centre‐right.

H2. Centre‐left mainstream parties are more prone to talk about climate change and to adopt pro‐climate positions than conservatives and liberals.

Another relevant factor on the party system dimension is government participation. Several scholars argue that parties in opposition are more prone to adopt new issues because they are less constrained by the legacy of previous governments, corporate interests, international commitments, economic and other external factors (Hutter & Vliegenthart, Reference Hutter and Vliegenthart2018; Van Spanje, Reference Van Spanje2010). Publicly promoting measures against global warming can therefore have a boomerang effect if these declarations are not supported by concrete action.

Others argue exactly the opposite. Incumbent parties’ policy shifts are more visible to the voters, and since they are in the spotlight of the media, they are almost forced to respond to external pressure and public opinion (Fagerholm, Reference Fagerholm2016; Green‐Pedersen & Mortensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Mortensen2015; Meyer, Reference Meyer2013). I argue that opposition parties can always accuse the government of doing too little against global warming – even if the former introduces climate policies (Farstad, Reference Farstad2018). The fact that opposition parties are less constrained by institutional factors to implement their climate‐proposals leads to the following hypothesis:

H3. Mainstream parties in opposition are more prone to talk about climate change and to adopt protective positions than incumbents.

Leaving the party system level, public opinion and the salience of specific issues among the public is considered a particularly important factor pressuring parties to behave in a certain way. According to Fagerholm (Reference Fagerholm2016, p. 505), ‘of all the factors that possibly affect party policy change, the most thoroughly examined is the expectation that changes in public opinion cause parties to change their positions’. The reason for this is again the vote‐seeking nature of mainstream parties. When certain issues and standpoints gain popularity among the public, decision makers are pressured to respond to it (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006; Stimson et al., Reference Stimson, Mackuen and Erikson1995). Schwörer (Reference Schwörer2021) found, for example, that the salience of the immigration issue among citizens strongly correlates with nativist discourses among mainstream parties. Yet, we so far know little about the link between public opinion and parties’ environmentalist/climate agendas. I formulate the following hypothesis:

H4. The higher the public salience of environmental/climate issues, the more mainstream parties emphasise the climate issue adopting protective positions.

Theories of social power resources emphasise the impact of political pressure groups on parties’ political behaviour. While different schools of thought exist in this respect, they all agree that policies and state action is influenced by the state of social power relations and respective organisations and movements (Esping‐Andersen, Reference Esping‐Andersen1990; Olson, Reference Olson1982; Rueschemeyer et al., Reference Rueschemeyer, Stevens and Stevens1992). That the strength of certain movements (and respective media coverage) influences party behaviour, has been shown empirically (Hutter & Vliegenthart, Reference Hutter and Vliegenthart2018). In the field of environmental studies, the public visibility of anti GMO‐movements has been associated with hostile policies towards GMOs among European governments and parties (Kurzer & Cooper, Reference Kurzer and Cooper2007; Schwörer et al., Reference Schwörer, Romero‐Vidal and Vallejo2022). Regarding the climate issue and compared to previous climate movements, it is particularly FFF that has gained extensive media attention and is expected to have influenced politics in Europe (De Moor et al., Reference De Moor, Vydt, Uba and Wahlström2021; Marquardt, Reference Marquardt2020).

As argued by environmental groups themselves, ‘Fridays for Future is certainly not the first or the last environmental movement, but it is arguably the most talked about’ (Igini, Reference Igini2022). According to De Moor et al. (Reference De Moor, Vydt, Uba and Wahlström2021), this may be due to several ‘new’ aspects of FFF distinguishing it from previous climate protests. People participating in the protests have often never protested before, making the movement open to non‐activists. Accordingly, the movement deviates ‘from the more oppositional framing of climate justice that has previously been used to depict a clear opposition between the movement and its “enemies”’ (De Moor et al., Reference De Moor, Vydt, Uba and Wahlström2021, p. 623). Unlike many previous movements, FFF directly addresses government actors rather than individuals, and demands that they listen to science and fight for the Paris climate agreement. In sum, the open character of the movement, together with widely accepted demands towards politicians and governments, leads to the unprecedented mass protests in Western Europe and is expected to impact political decision makers. We can therefore expect mainstream parties to emphasise climate protection stances more frequently after the establishment of FFF:

H5 After the establishment of Fridays for Future, mainstream parties increasingly address the climate issue and adopt protective positions.

Research design

This study aims to assess what influences mainstream parties’ policy agendas towards climate protection. I therefore focus on mainstream parties ‘as the electorally dominant actors in the centre‐left, centre, and centre‐right blocs on the Left–Right political spectrum’ (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005, p. 348) – namely liberal, social democratic, conservative and Christian democratic parties. These actors still structure party competition in Western Europe and usually lead national governments. Since the analysis requires some knowledge of the language in which the texts are written, I restrict the analysis to Western European party systems. The aim of the study is to make general statements about the triggers of mainstream parties’ climate agendas. For this purpose, I focus on an extensive sample of parties from a variety of countries, namely from Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Italy, France, Spain, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Sweden and Norway from 1990 to fall 2022. The longitudinal dimension further allows to assess trends regarding the salience of climate‐protection demands over time.

As sources I select election manifestos providing official and collective statements of parties on different political issues (Hansen, Reference Hansen2008) or, as Robertson (Reference Robertson2004, p. 295) puts it, ‘the official statements of intended policy issued by political parties at the beginning of election campaigns’. It can therefore be expected that references to global warming are most likely to be found in these documents. Election manifestos allow both, comparison across time and countries. In total, 292 election manifestos have been analysed.

Unfortunately, and as mentioned above, existing datasets like the Manifesto project and the Chapel Hill group (Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022; Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2021) do not provide data on parties’ positions on climate protection. The environmental protection indicator only considers climate as one among many other environmental issues in election manifestos. Farstad (Reference Farstad2018) has collected data for some parties in Western Europe but only at one point in time (mostly around 2010). Carter et al. (Reference Carter, Ladrech, Little and Tsagkroni2018) provide a methodological approach to analysing parties’ climate standpoints that is quite similar to the one used in this study (pro‐ and contra‐climate protection coding). However, they do not collect data for most countries and periods included in this study. Therefore, the salience and position towards global warming is collected through an extensive analysis conducted by the author.

The measurement shares the approach from Carter et al. (Reference Carter, Ladrech, Little and Tsagkroni2018) with two important differences. First, I opt for a combination of manual and dictionary‐based content analysis (Rooduijn & Pauwels, Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011). In a first step, a list of keywords related to the climate topic was created by theoretical reflections. Based on extensive explorative pre‐tests, the dictionary was adjusted until no obvious reference was overlooked. In a first step, I searched for the keywords (e.g., ‘warm*’, ‘temperature’, ‘climate’) in the manifesto corpus (for the multilingual dictionary see the Appendix in the Supporting Information). The keyword search has one important advantage: it is less time consuming and allows the analysis of a large number of texts. However, in line with Carter et al. (Reference Carter, Ladrech, Little and Tsagkroni2018), the text passages containing a respective keyword were analysed manually in order to trace the meaning of the reference. Sentences following the keyword were also considered until they no longer addressed the climate issue.

Second, unlike Carter et al. (Reference Carter, Ladrech, Little and Tsagkroni2018), I only code explicit references to global warming – that is, only if demands for better air quality or a reduction in emissions are justified with reference to climate protection (e.g., by being mentioned in a respective climate section in the manifesto). This is because not all environmental measures are motivated by climate protection – emissions from the transport sector, for example, are often criticised due to their impact on human health. In the field of energy policies, demands for renewable energy are not always justified by climate protection but by energy security. In these cases, such references were not coded.

In line with Carter et al. (Reference Carter, Ladrech, Little and Tsagkroni2018), the coding scheme consists of two (pro/contra) categories. The first and dominant category contains demands for climate protection, the recognition of human‐made climate change or descriptions of negative consequences of climate change. The second one consists of rejections of measures against global warming. With very few exceptions, almost no party officially questions measures or the necessity to act against climate change. Based on the standard from the Marpor project and in line with Carter et al. (Reference Carter, Ladrech, Little and Tsagkroni2018), the ‘quasi‐sentence’ constitutes the unit of measurement. The total share of political statements for each election manifesto is available at the website of the manifesto project within the original data files.Footnote 2

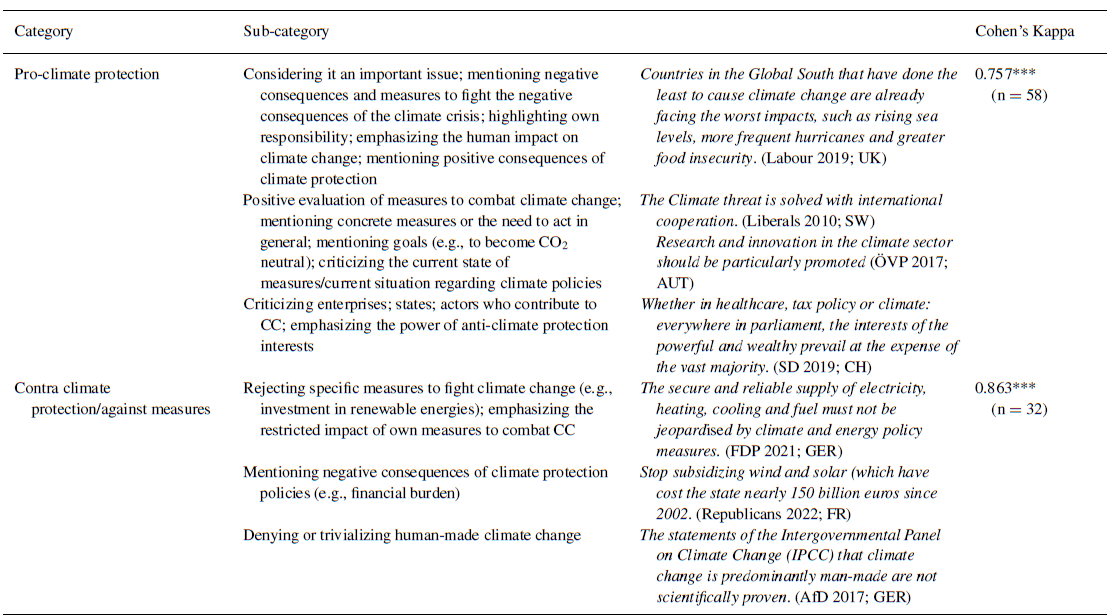

For the sake of inter‐coder reliability, I calculated Cohen's Kappa (Landis & Koch, Reference Landis and Koch1977). I prepared a list of text segments (10 different contexts, 58 quasi‐sentences for the pro‐category) from German and British manifestosFootnote 3 that talk about climate, as well as a similar amount of quasi‐sentences that occurred in the same climate‐related text passage but was not coded as a climate reference.Footnote 4 Another person coded these segments according to the rules of the codebook. Cohen's Kappa is substantially consistent for the pro‐category and almost perfectly consistent for the contra‐codings (Landis & Koch, Reference Landis and Koch1977).Footnote 5 Table 1 shows the category system including Cohen's Kappa. As the most important dependent variable I chose the salience of references towards global warming. The salience score reflects the share of all climate‐related quasi‐sentences on the total amount of quasi‐sentences in one election manifesto. I further constructed a net‐evaluation index (‘position’), representing the share of demands for climate protection after subtracting anti protective claims from the score. Since almost all references towards climate express protective standpoints, the net‐evaluation score is less emphasised in the analysis.

Table 1. Category system for measures of climate positions

Note: ***p < 0.001.

Regarding the independent variables, I rely on a variety of factors. First, the question arises how to measure green parties’ standing in the polls. The assumption is that mainstream parties are influenced by the current success of green parties, i.e. they will address climate‐related issues more frequently when green parties perform well in opinion polls. Scholars often use the past election result of niche parties for that purpose (Abou‐Chadi, Reference Abou‐Chadi2016; Spoon et al., Reference Spoon, Hobolt and Vries2014). However, past electoral performances tend to neglect electoral shifts between elections (Adams, Reference Adams2012; Fagerholm, Reference Fagerholm2016). If a green party failed in the last election but is a relevant actor in the actual campaign, mainstream parties will hardly consider the past performance. Accordingly, other scholars choose the actual election results of niche parties from the election for which the manifesto was produced, arguing that they are much closer to predictions in opinion polls (Schwörer et al., Reference Schwörer, Romero‐Vidal and Vallejo2022). To assess which data are more suitable, I calculated the difference between the past election results of green parties and the standing in the polls during election campaigns and compared this with the deviation of the results for the ‘current’ election from the poll prediction.Footnote 6 In 10 out of 14 cases, the ‘current’ election result was much closer to the predicted poll data than the past election result (at least ‘better’ than one percentage point). In five cases the past election results deviated very significantly from the poll data – from four (NL 2017) up to more than 10 per cent (AUT 2017) – while the biggest deviation among the ‘current’ election results was less than 4 per cent (GER 2021). In only one case the past election data were considerably closer to the poll estimation than the ‘current’ election results (three percentage points ‘better’ in Sweden 2014). On average, the past election forecast was 3.7 per cent (SD = 3.07), the ‘current’ election results only 1.7 per cent (SD = 1.17) off. Therefore, I use green parties’ vote shares from the actual election for which mainstream parties’ manifestos were created – since they are closer to estimations from opinion polls.

As a public opinion indicator, I rely on Eurobarometer (EB) data since 2002, regarding the two most important issues that the citizens’ country is facing at the moment. I collected the percentage of respondents per country and respective year that considers protecting the environment as one of the most important issues.Footnote 7 Data were used from EB‐waves conducted at least 4 months before the respective elections. For Switzerland and Norway (until 2021) and most periods before 2002, data are not available.Footnote 8 Unlike data from other surveys like the European Social Survey (ESS), EB conducts its interviews twice a year, providing data very close to elections (ESS conducts its surveys every 2 years). Although some countries are missing in the EB dataset (Norway; Switzerland), the same is true for the ESS (the country sample changes over time). Furthermore, and most importantly, ESS does not provide information about the salience of environmental/climate issues for the respondents.Footnote 9

I further control for incumbent status using data from Bergman et al. (Reference Bergman, Bäck and Hellström2021) and Hellström et al. (Reference Hellström, Bergman and Bäck2021). Parties supporting minority governments are treated as incumbents. Party family characterisations are used from Parlgov (Döring & Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2020). Unfortunately, the impact of FFF cannot be measured directly. Instead, and in line with existing research (Schwörer et al., Reference Schwörer, Romero‐Vidal and Vallejo2022), I opt for a longitudinal comparison by assessing the impact of different periods. For this purpose, I select short time sequences of 3 years since the start of the period of analysis. This further allows to control for other important events influencing party behaviour – in case that parties considerably increase their climate references during other periods. FFF started in late 2018 and reached large media attention in Western Europe in the following months (Marquardt, Reference Marquardt2020; De Moor et al., Reference De Moor, Vydt, Uba and Wahlström2021). I therefore expect that all manifestos published after the establishment of FFF (all after 2018) should emphasise climate protection.Footnote 10 A problem with this general time variable is that it does not account for differences regarding the strength of the movement in the individual countries. Yet, FFF is considered an international movement getting Europe‐wide media attention, not only in countries where activists operate (Brünker et al., Reference Brünker, Deitelhoff and Mirbabaie2019; De Moor et al., Reference De Moor, Uba, Wahlström, Wennerhag, Vydt, Almeida, Gardner, Kocyba, Neuber, Gubernat, Kołczyńska, Rammelt and Davies2020). Therefore, it can be assumed that the impact of the movement is not restricted to countries where FFF is particularly active. A summary of all dependent and independent variables is attached to the Appendix in the Supporting Information.

Results

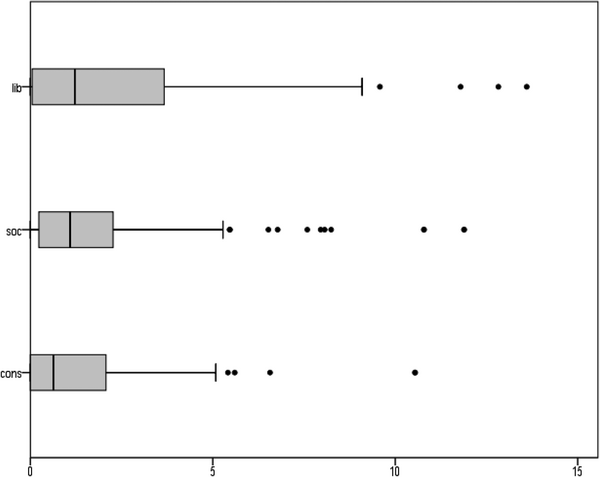

Let's start with a descriptive look at the salience of the climate issue by party group. Figure 1 shows box plots for liberal, social democratic and conservative (including Christian democratsFootnote 11) parties. Surprisingly, it is the liberal parties, which most often talk about climate change on average (2.39; SD = 3.02; n = 91), closely followed by the centre‐left (2.2; SD = 3.73; n = 86). The centre‐right refers less frequently to global warming in its election manifestos (1.4; SD = 1.83; n = 115). The difference between liberals and conservatives is statistically significant as an independent t‐test shows (t = 2.74; p = 0.007)Footnote 12 while the difference between social democrats and conservatives is just above the significance level (t = 1.83; p = 0.07). Hence, it is not necessarily the economic left–right distinction that determines the salience of the climate issue among mainstream parties since market‐liberal parties are far from ignoring the issue. Interestingly, no party group speaks out against climate protection. Only very few parties occasionally reject specific climate‐related measures. The salience index is therefore almost identical with the net‐evaluation (or positional) score, questioning the assumption that climate protection is a positional rather than a valence issue – at least regarding mainstream parties.

Figure 1. Salience of the climate issue by party group (ordered by mean). Note: Horizontal axis shows the percentage of climate references (quasi‐sentences) per party manifesto. Outliers not illustrated: SP (soc; CH), 27.05 per cent. Lib: mean = 2.39; SD = 3.02; Soc: 2.2; SD = 3.73; Cons: mean = 1.4; SD = 1.83.

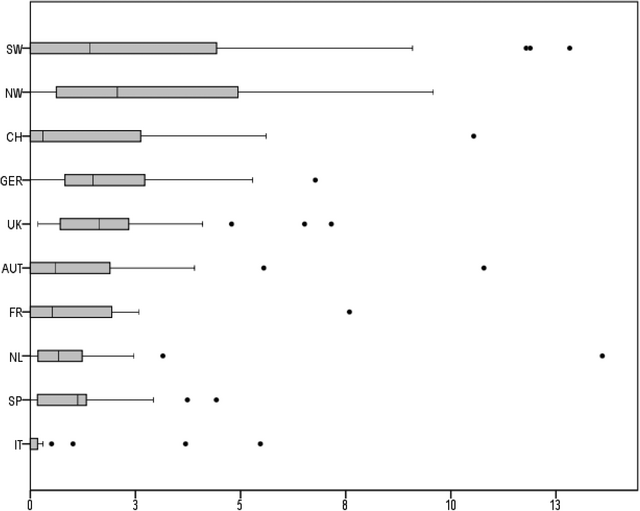

Figure 2 shows the salience of climate protection by country. It is primarily mainstream parties in northern Western Europe and, to a lower extent, in Germany and the UK, addressing the issue while it is less important for parties in Southern Europe.

Figure 2. Salience of the climate issue by country (ordered by mean). Note: Horizontal axis shows the percentage of climate references (quasi‐sentences) per party manifesto. SW: 3.04 (n = 45; SD = 3.56); NW: 2.99 (n = 40; SD = 2.63); CH: 2.58 (n = 24; SD = 5.78); GER: 2.1 (n = 27; SD = 1.83); UK: 2.07 (n = 24; SD = 1.9); AUT: 1.37 (n = 29; SD = 2.29); FR: 1.24 (n = 22; SD = 1.7); NL: 1.15 (n = 35; SD = 2.29); SP: 1.14 (n = 22; SD = 1.22); IT: 0.48 (n = 24; SD = 1.31). Outliers not illustrated: SP (soc; CH), 27.05 per cent.

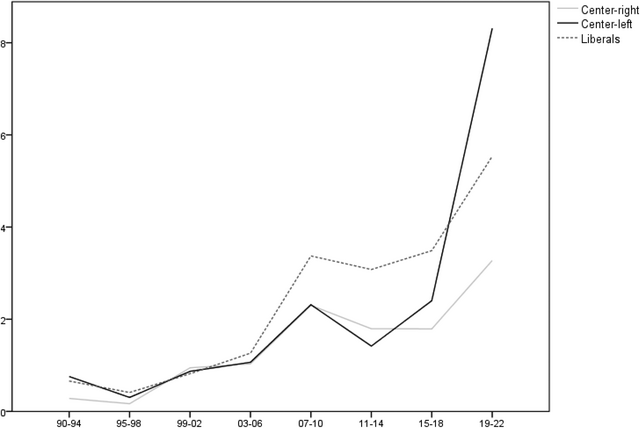

But how did the global warming issue develop over time? Can we observe an increased importance in mainstream parties’ election manifestos recently during FFF mass mobilisation? Figure 3 illustrates the development of the climate issue since the 1990s by different party families. It illustrates the average values for each party family and period. Climate change became more important in political competition after the turn of the century. In general, we see a steady increase over time. Except for the 2011–2014 period, there is no single time unit where the average share of climate references is lower than in the previous one. The graph shows that liberals emphasised the climate issue more frequently than others between 2003 and 2018 while social democratic and conservative parties addressed global warming to an almost equal extent in this period. After 2018, however, centre‐left parties are by far the party group most frequently speaking out for climate protection in line with H2.

Figure 3. Salience of the climate issue over time by mainstream parties. Note: Average scores per period and party family.

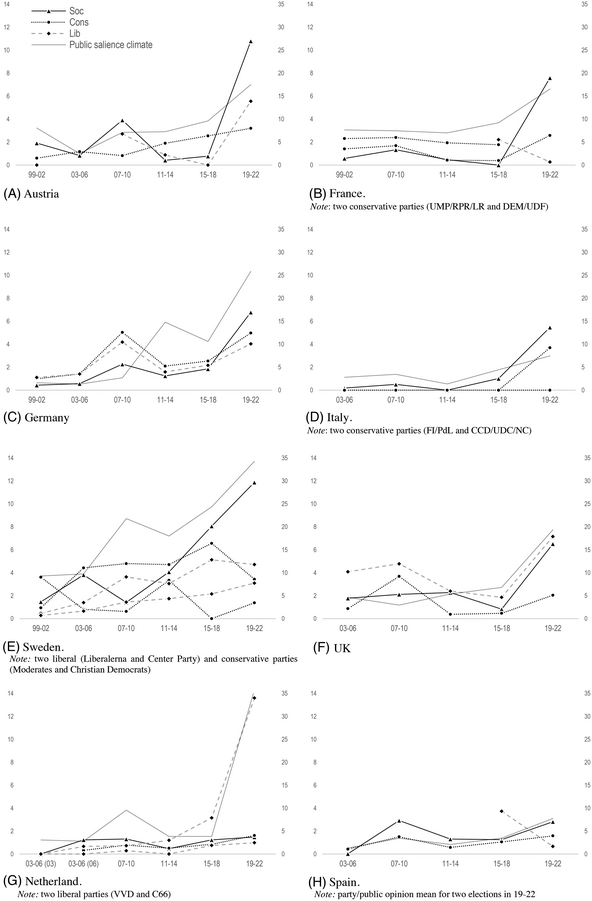

All party families have considerably increased their references to global warming since 2019 – although the liberal and centre‐right scores have not increased as much as those from centre‐left parties, which, on average, have devoted more than 8 per cent of their manifestos to climate protection since 2019. The increase since 2019 provides the first arguments for H5. We see another increase in climate references – although much less pronounced – between 2007 and 2010. As mentioned in Figure 6, this corresponds in some countries with a shift in public opinion – yet, in others not. Another explanation might be that 2007 was the hottest year on record in the northern hemisphere, with dozens of people dying under the heat in Europe (Borenstein, Reference Borenstein2008). Besides the notable but moderate increase in climate references in 2007–2010, we see no other remarkable development over time except for the outstanding 19–22 period. In this sense, no other event seems to have had substantial impact on parties’ climate agenda – this is confirmed by a look into the single countries (Figure 6).

Again, as almost all references towards the climate issue are statements in favour of climate protection (or at least recognise human‐made climate change as a threat), the data can further be interpreted in the sense that mainstream parties do not only talk more about the issue (salience) but further become more climate‐friendly over time (position).

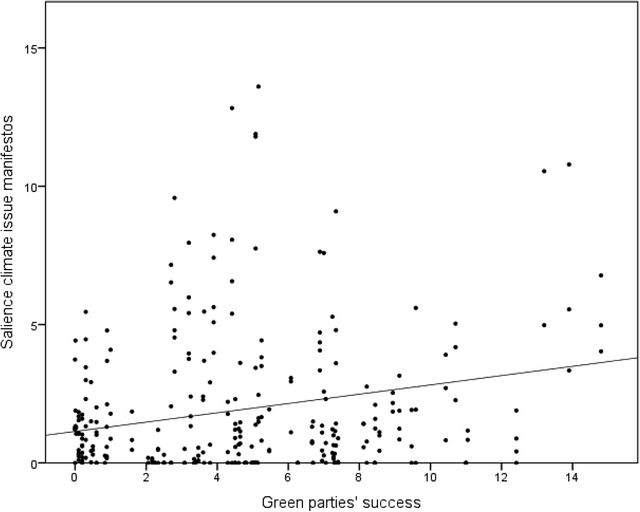

A crucial factor expected to lead mainstream parties to adopt climate protection demands is the success of green parties as issue owners. We should therefore expect a correlation between green parties’ electoral success and the frequency of mainstream parties’ climate references (H1). Figure 4 shows a statistically significant correlation between mainstream parties’ issue emphasis and green parties’ success.Footnote 13

Figure 4. Green parties’ electoral performance and mainstream parties emphasis on climate change. Note: r = 0.2; p < 0.001; n = 284. Not illustrate outlier: SP (CH) 2019 (27.05 per cent climate references).

Interestingly, the correlation between green parties’ performance and the salience of climate protection among mainstream parties is restricted to the centre‐left and conservative parties. The Pearson coefficient is almost the same for centre‐left (r = 0.3; p ≤ 0.01) and conservatives (r = 0.31; p ≤ 0.01) and statistically significant. Although liberals talk frequently about global warming, they do not do so in response to the rise of the green parties (r = 0.01; p > 0.05).

Regarding the last variable from the party system level, incumbent status does not contribute to a lower salience of the climate issue among mainstream parties (H3). On average, parties in government are even slightly more engaged in climate discourses (mean: 2.02; SD = 3.27) than opposition parties (mean: 1.87; SD = 2.45). However, these differences are not statistically significant, as shown by an independent t‐test.

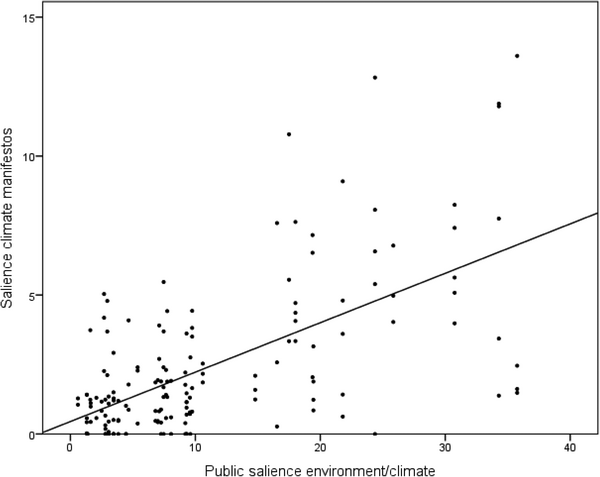

While green parties' electoral success correlates only weakly with mainstream parties' emphasis on climate protection, the public awareness of environmental and climate‐related issues may be an explanation for party behaviour (H4). Figure 5 shows the scatterplot for the salience of the climate issue for political parties and the percentage of citizens considering environmental protection as one of the two most important issues their country faces (EB data since 2002). The public's attitudes seem to have a much higher influence on parties than the success of green parties. The correlation is particular high and significant (r = 0.623; p < 0.001). Interestingly, even the liberal party family seems to be responsive to public attitudes (r = 0.717; p < 0.001). The correlation coefficient is considerably higher for the liberals than for the conservatives (r = 0.489; p < 0.001) and even slightly above the coefficient from the centre‐left (r = 0.67; p < 0.001).

Figure 5. Public salience of environmental/climate issues and mainstream parties’ emphasis on climate change. Note: r = 0.623; p<0.001; n = 162. Contains elections since 2002. Does not include Swiss and Norwegian parties (except the manifestos from Norway in 2021).

Figure 6 shows the development of parties’ climate references and the public salience of environmental issues for the single countries. In many cases, we see similar developments between the public opinion indicator and certain parties – in particular social democrats, but also liberals. Thus, even within the individual countries, public opinion seems to explain certain changes in parties’ emphasis on climate protection.

Figure 6. Public salience of environmental/climate issues and mainstream parties’ emphasis on climate change per country. Note: Left axis represents the share of climate references (salience). Right axis shows the percentage of respondents considering the environment as one of the two most important issues the country is facing.

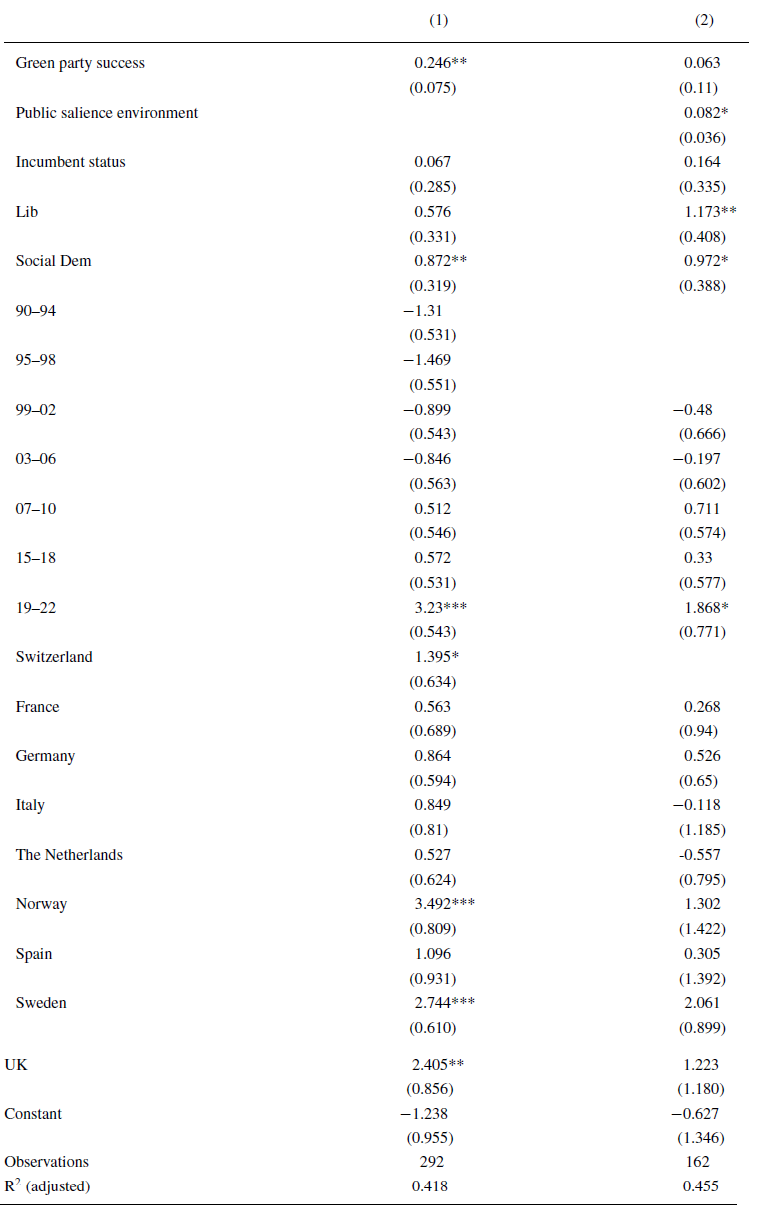

To systematically assess the effect of the independent variables on climate agendas of mainstream parties, Table 2 shows an OLS regression model including different variables. Besides the already mentioned variables (green party success, incumbent status), I control for party group effects using the centre‐right family as reference group. H5 assumes that especially the 2019–2022 period has a significant effect on emphasis on climate protection. Therefore, dummies for different periods are included using the 2011–2014 period as reference category, which is closest to the overall median (1.61) and mean (1.95). Besides the mentioned independent variables, further national factors may explain salience shifts – for example, the dependency on fossil energy or economic conditions that restrict investments in clean energy. To estimate national time‐constant unobserved variance, the model further controls for country effects using Austria (close to the overall median) as reference country.

Table 2. Multiple linear regression model estimating the causes for parties’ climate agenda

Note: Standard errors in brackets. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Two different models are illustrated in Table 2. The first one includes party system indicators (green party success; incumbent status; party group dummy with centre‐right as reference category) and shows a significant effect of green parties’ success on the salience of climate protection.Footnote 14 Furthermore, being a centre‐left party significantly increases the likelihood of talking about climate as expected by H2. As shown descriptively (Figure 3), it is particularly the 2019–2022 period that has a very significant effect on mainstream parties’ emphasis on climate issues (H5). Parties in Norway and Sweden talk particularly often about climate protection.Footnote 15

The second model adopts the party system indicators (green party success; party family; incumbent status) and adds the public opinion variable (importance of environmental/climate issues according to respondents). The number of observations decreases as several election years (1990–2001) and data for Switzerland (and Norway, except elections in 2021) are not covered by the EB data. As time dummy, the 11–14 period is chosen. Reference country is Austria.

Including the public opinion indicator (importance of environmental/climate protection) eliminates the effect of green parties and increases the overall explanatory power of the model (R2 (adjusted) = 0.46). The public salience of environmentalist issues seems to moderate the effect of green parties. Mainstream parties appear to be less concerned about niche parties’ success and party system dynamics but more about the general public mood. Again, centre‐left parties, but now also liberal parties, are more likely to speak out for climate protection compared to the conservatives. The effect of the 2019–2022 period remains significant. Interestingly, country‐specific effects disappear, possibly because national public moods capture many of the potential country‐specific factors (e.g., dependency on fossil fuel; economic aspects).Footnote 16 In sum, there is no support for H1 (green parties’ impact) but support for H4 (impact of public salience of environmental protection). Opposition status does not make any difference (H2) while being not conservative – including being liberal – increases climate‐related references in manifestos (H3). The recent period since the establishment of FFF (H5) significantly contributes to a stronger climate agenda among mainstream parties. The respective coefficient is also particularly high.

Discussion and conclusion

What influences the climate agenda of mainstream parties? While a number of studies have assessed the reasons for parties’ nationalist or nativist agendas, we so far know little about what drives mainstream parties’ positions on green issues, particularly climate protection. This study has attempted to fill this gap by identifying factors that influence mainstream parties’ emphasis and positions on global warming, including a variable on the importance of the issue to the public – a previously neglected factor. Conducting quantitative content analysis of 292 election manifestos of liberal, social democratic and conservative parties, I have provided the most comprehensive dataset on mainstream parties’ climate positions and issue emphasis. As argued in spatial theories of party competition, the success of green parties as issue owners and an increased public salience of environmental issues should lead mainstream parties to address climate protection demands. Moreover, incumbent status, a left‐wing ideological background and periods of public mass mobilisation are expected to change mainstream parties’ issue emphasis.

The OLS regression models support some of the theoretical expectations but reject others. The success of green parties is not associated with mainstream parties’ climate agendas if we control for the public salience of environmental issues. So far, existing research has only included the niche party variable, ignoring public opinion (Abou‐Chadi, Reference Abou‐Chadi2016; Spoon et al., Reference Spoon, Hobolt and Vries2014). Moreover, especially since 2019, mainstream parties emphasise climate protection in their manifestos. This could be interpreted as a result of the high visibility of the European FFF movement, exerting a particularly strong effect on mainstream parties. I should admit, however, that the time dummy is not a particularly strong indicator for the activity of FFF, as it may also cover other developments during the same years, such as the IPCC 1.5 degrees report (October 2018). One should consider, however, that other important events also took place in other years (e.g., Paris agreement), which are not associated with a particular strong increase of climate references among parties. The academic literature and activists alike seem to agree that it is especially FFF which is having an unprecedented effect on politics (Marquardt, Reference Marquardt2020; Igini, Reference Igini2022; De Moor et al., Reference De Moor, Vydt, Uba and Wahlström2021).

We see significant variations across countries regarding the salience of climate discourses. Climate change is particularly salient in election manifestos in Norway and Sweden and to some extent also in the UK and Switzerland. This can be explained by the public concernedness in these countries – while in Spain and Italy the climate plays no crucial role in electoral campaigns. This study did not assess the reasons for the differences in public opinion, but as previous studies have shown, it could be a result of economic conditions (Franzen & Vogl, Reference Franzen and Vogl2013). Whether mainstream parties are in government or opposition does not influence their climate discourses.

The findings of this study challenge Spoon et al.’s (Reference Spoon, Hobolt and Vries2014) argument that the success of Green parties makes a difference. In this sense, future studies may focus more on attitudes and issue salience among the public which seem to moderate effects from the party system level. Green parties’ success can be seen as another public opinion indicator since their performance expresses public popularity of environmental positions (Schwörer et al., Reference Schwörer, Romero‐Vidal and Vallejo2022). However, green parties are not exclusively voted for their climate agenda but also generally for their post‐materialist, left‐leaning and progressive standpoints towards individual and minority rights (Close & Delwit, Reference Close, Delwit and van Haute2016). In this sense, the success of green parties can be interpreted in different ways by mainstream parties and not exclusively as a consequence of public support for climate protection.

Yet, the relationship between green parties and public opinion may be more complex. As parties can set agendas, the existence of a green party may also influence public opinion to some extent. It can therefore not be ruled out that green parties may play a role in shaping the overall public attitudes towards climate protection. However, we should be more cautious in selecting the variable for green/niche parties’ success. Past election results are not a good choice because they deviate significantly from the actual standing in the polls of green parties during election campaigns. I therefore suggest to use the result from the election after the campaign which is much closer to the estimations from opinion polls.

The relationship between public opinion and protest movements is another aspect worth discussing. Both variables appear to have a significant impact on mainstream parties’ issue emphasis, but may also be related. The mass mobilisation of FFF could be described as the peak of public awareness of climate change. Yet, the general public opinion and the strength of protest movements still are found to be variables on their own, each of them having a specific impact on state actors, but they can also reinforce each other (Schwörer et al., Reference Schwörer, Romero‐Vidal and Vallejo2022; Weaver, Reference Weaver2008). A visible protest movement can have more impact if large parts of the public are in favour of its actions.

What are the implications of these findings? The results indicate that mainstream parties are responsive to external pressure. From a normative perspective, it should be evaluated positively that mainstream parties seem to be responsive to public opinion. In the face of public opinion shifts, and in particular since 2019, mainstream parties have dedicated considerable parts of their manifestos to the climate issue. Assuming that the FFF movement seems to trigger climate references among parties, this also means that public protest makes a difference and that climate activists are heard to some extent.

It should be noted, that this study did not go into the concrete policy proposals from mainstream parties. Neither does an increased awareness of the effects of global warming automatically lead to greener state policies. The fact that mainstream parties emphasise climate protection in the face of public opinion shifts does not automatically mean that they implement such policies. Yet, first empirical studies have shown that election manifestos matter in policy making and that parties cannot ignore their authoritative statements (Brouard et al., Reference Brouard, Grossman, Guinaudeau, Persico and Froio2018). Considering climate change as an important challenge is therefore a first necessary condition for meaningful climate policies.

Finally, the question arises whether the findings could also be applied to regions other than Western Europe. According to spatial theory, they can (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005). Mainstream parties in democratic party systems are generally considered as vote‐seekers responding to shifts in public opinion. The logic may be slightly different between interactions in two and multiparty systems (Adams, Reference Adams2012; Downs, Reference Downs1957; Schwörer, Reference Schwörer2021), but the general assumptions from spatial theory also seem to apply for political competition in non‐European democracies such as Latin America (León Ganatios, Reference León Ganatios2013). Future studies will have to show whether this theoretical assumption also holds empirically.

Acknowledgement

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data Availability Statement

Codebook and MAXQDA files (with all election manifestos) are available on request. All data and spv. files are attached.

Funding Information

The author does not report any funding.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The author does not report any conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval Statement

The research is in line with the journals’ ethical standards.

Permission to Reproduce Material from Other Sources

No permissions for other sources were needed.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

ONLINE APPENDIX

Supporting Information