Introduction

By and large, 2024 represented a continuation of 2023. The three-party right-of-centre government, relying on support from the Sweden Democrats (SD) through the 2022 Tidö agreement, continued to work without serious disturbances or internal divisions. A reshuffle took place in September, following the resignation of the Minister for Foreign Affairs and the elevation to the EU commission of the Minister for EU Affairs. As in 2023, the opposition parties were ahead of the government bloc in the polls, but it remained unclear whether they could provide a coherent government alternative. The EU election in June resulted in marginal changes, all main parties maintaining their representation in the EU Parliament. The big event of 2024 was that the Swedish membership of NATO was completed and confirmed. This manifested a transformation of Swedish security and defence policy, which until recently had been based on military non-alignment.

Election report

European parliamentary elections

Sweden's seventh election to the EU Parliament since 1995 took place on 9 June. The run-up to the election had dramatic elements. The Christian Democrats (KD) were struggling in the polls and were in danger of entirely losing their representation. In January, KD presented Alice Teodorescu Måwe as the front candidate. At the same time, the incumbent KD Member of the European Parliament Sara Skyttedal was de-selected when it emerged that she had investigated the possibilities of a move to SD. Teodorescu Måwe was a well-known conservative-leaning profile in the political debate, mainly as a newspaper editor and columnist, but had not previously represented a political party. Skyttedal promptly left KD, but kept her seat in the European Parliament as an independent. Together with the dissident Social Democrat and former reality show performer Jan Emanuel, she formed a new party called the People's List (Folklistan). This party got plenty of media attention but had no success in the election and was subsequently disbanded.

In March, Teodorescu Måwe made critical remarks against SD in an interview, which led to an acrimonious exchange between the SD and KD leaders (Björkman & Svensson Reference Björkman and Svensson2024). In May, the commercial channel TV4 exposed an alleged online ‘troll factory’ organised by SD. A number of anonymous social media accounts published sarcastic images, memes and deepfakes. The main targets were SD's political opponents but also included representatives of the governing parties with which SD co-operated through the Tidö agreement. An example was Alice Teodorescu Måwe, whose criticism of SD led to an intense campaign against her, apparently orchestrated by the SD-linked ‘troll factory’. An undercover TV4 journalist reported that several anonymous ‘troll’ accounts were linked to the SD communications unit (TV4 2024). The revelations led to a debate, in which SD somewhat unusually found itself on the defensive. On 14 May, SD leader Jimmie Åkesson launched a counterattack in a streamed ‘Speech to the Nation’. He claimed that there was an ongoing ‘domestic influence operation from the collected left-liberal establishment’, calling the reporting by TV4 ‘uninhibited campaign journalism’ (Zangana Reference Zangana2024). The tone of the speech was confrontational, its apparent purpose being to mobilise hardcore SD supporters rather than broaden the party's appeal. It led to further debate, and soured relations between SD and the government parties, which had been among the ‘troll factory’ targets.

In many ways, the election debate tended to focus on issues with, at most, indirect relevance to the EU Parliament, such as crime prevention, support for Ukraine and climate. The concluding TV debate contained a heated exchange about the situation in Gaza, between the pro-Israel Teodorescu Måwe and SD's Charlie Weimers, and the pro-Palestine Jonas Sjöstedt of the Left Party (V) and Alice Bah Kuhnke of the Greens (MP).

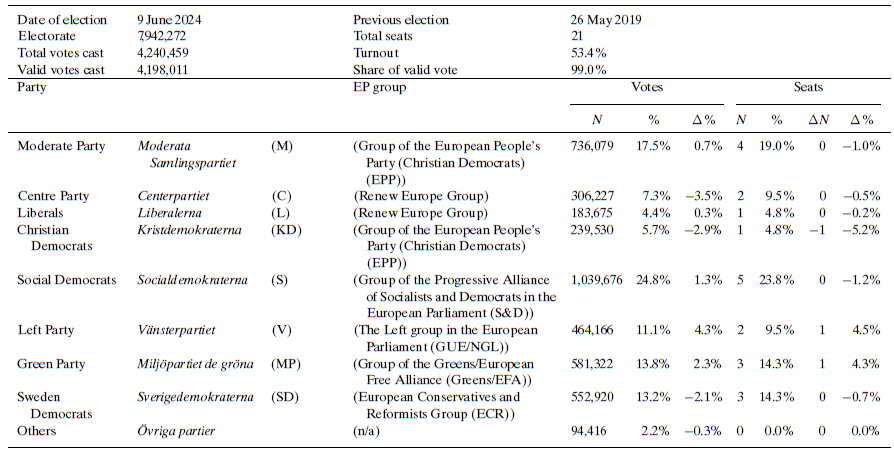

The result, reported in Table 1, can be summarised as close to status quo. Turnout was 53.4 per cent, a decline of 1.9 percentage points, compared to 2019. The same eight parties kept their representation, and no new party gained entry. The biggest gain in vote share was made by V, whose top candidate and former leader, Jonas Sjöstedt, broke the record number of personal preferences in an EU election. There were also gains for MP and S, the latter amassing over one million votes for the first time in an EU election, and more marginal increases for the Moderates (M) and Liberals (L). The biggest decline was suffered by SD, with a loss of 2.1 percentage points. It was the party's first-ever defeat in a nationwide election. One cited reason was the ‘troll factory’ debate, but support for the party had in the past been resilient against scandals and any impact of the ‘troll’ issue is difficult to prove. SD's ratings in polls about parliamentary vote intentions were largely unaffected, and a more plausible explanation was that the party failed to mobilise parts of its support base. KD and the Centre Party (C) also suffered losses but they had feared entirely losing their representation in the EU Parliament and the result was met with relief in both parties. In terms of seats the changes were marginal. V and MP gained one seat each, and KD lost one; all other parties kept the same number of seats (the total number of seats had increased from 20 to 21 following the UK exit in 2020).

Table 1. Elections to the European Parliament in Sweden in 2024

Note: The total number of Swedish seats in the EU Parliament increased from 20 to 21 on 31 January 2020 as a consequence of the UK exit. The extra Swedish seat went to the Green Party. Seat comparisons in the table are between the 2024 and 2019 election results.

Sources: European Parliament website (https://results.elections.europa.eu/en/breakdown-national-parties-political-group/2024-2029/); Swedish Election Authority (https://resultat.val.se/protokoll/protokoll_EU-val_2024_00_E.pdf).

Cabinet report

The Kristersson I Cabinet remained in office without serious problems throughout 2024. Relations between the three government parties M, KD and L and the support party SD became somewhat strained in connection with the disagreements between KD and SD, and the media revelations about an SD ‘troll factory’, during the EU election campaign (see Election Report). It never came close to a serious crisis, however, and the government continued the reform agenda agreed with SD in 2022. Halfway through the 2022–2026 election period, in September, the government announced that 96 per cent of the policy commitments in the Tidö agreement had either been completed (31 per cent) or were in progress (65 per cent) (Swedish Government 2024a). The remaining 4 per cent included a national ban on begging, and the introduction of charges for the use of interpreters in health care. In these cases, steps towards policy proposals were initiated later in 2024 and early 2025.

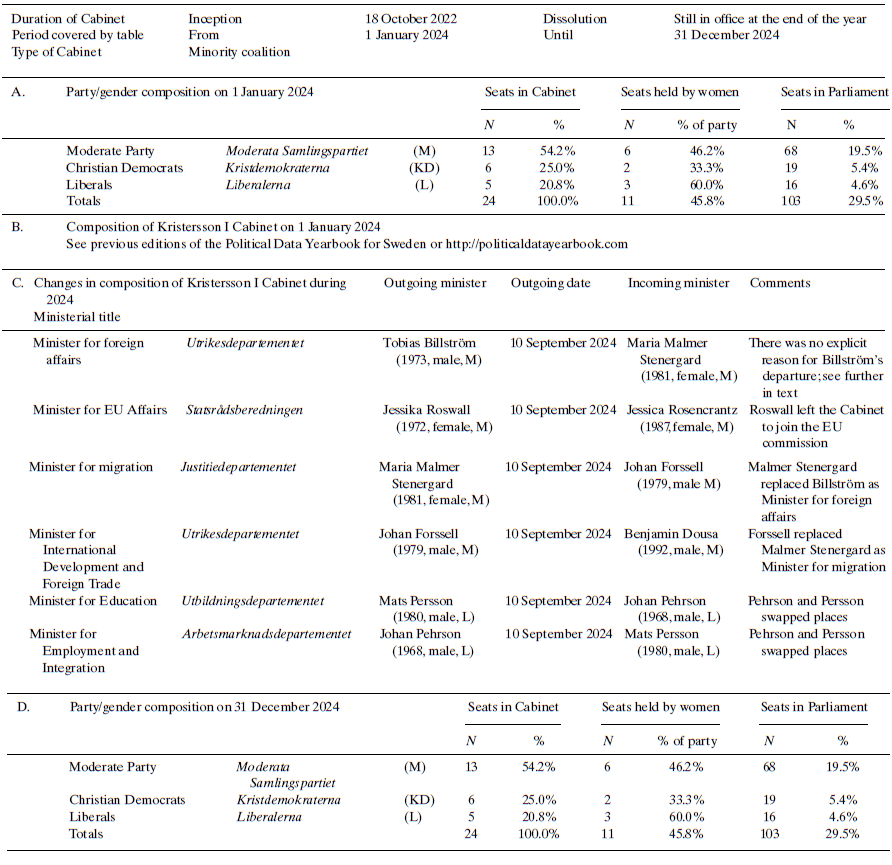

The first government reshuffle took place in September. In July, the government announced that it would nominate EU Minister Jessika Roswall to the new EU commission. She eventually assumed the portfolio of Environment, Water Resilience and a Competitive Circular Economy. A minor consequential reshuffle was expected, but on 4 September the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Tobias Billström, surprisingly announced his resignation. The reason was, and at the time of writing still is, not clear. Billström's own explanation, that he wanted to embark on a new career before it was too late, was somewhat unconvincing. Allegations of policy and organisational disagreements between Billström and Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson were dismissed by both sides. The reshuffle was announced in connection with the opening of the new parliamentary session on 10 September.

As seen in Table 2, there were six changes, all intra-party and in four cases within the government. Two new ministers were appointed. Billström's portfolio went to the Minister for Migration Maria Malmer Stenergard, whose post was given to the Minister for International Development and Foreign Trade Johan Forssell who, in turn, was replaced by the new appointment Benjamin Dousa. The latter had in the past chaired the M youth organisation and more recently held key positions in the market liberal think tank Timbro and the Swedish Federation of Business Owners. Roswall was replaced by the chair of the Parliamentary Committee on EU Affairs, Jessica Rosencrantz. All these changes were within M. In addition, two L ministers swapped places. Party leader Johan Pehrson moved from Employment and Integration to Education, and Mats Persson went the opposite way.

Table 2. Cabinet composition of Kristersson I in Sweden in 2024

Source: Swedish government website (2025) (www.regeringen.se/sveriges-regering/).

Parliament report

The parliamentary year passed without notable incidents in 2024. Party discipline remained intact, without significant intra-party rebellions (see, however, Issues in National Politics). In January, the tabloid Aftonbladet reported to have found traces of cocaine in the washrooms of four parliamentary party offices, namely, S, L, V and SD (Horn Reference Horn2024). It was embarrassing for the parties concerned and, arguably, for the Parliament as an institution, but had limited political consequences.

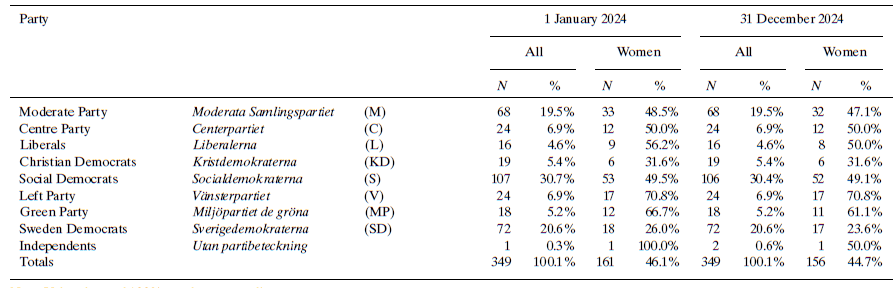

Pro-Palestine protests took place on several occasions, inside Parliament as well as in its near surroundings. In October, an activist threw vegetables aimed at the recently appointed Minister for Foreign Affairs, Maria Malmer Stenergard, during a debate. A net was subsequently placed between the public gallery and the chamber (Swedish Riksdag 2024). In February the Social Democrat Jamal El-Haj left his party but kept his seat as an independent. El-Haj had been criticised for participating in a conference with alleged links to Hamas in May 2023. He was also reported to have intervened in an asylum matter involving a conservative Imam (Sundberg Reference Sundberg2024). It meant that the number of independent members (in Swedish sometimes referred to as ‘savages’; vildar) increased from one to two (see Table 3), but the political impact was minimal.

Table 3. Party and gender composition of the Parliament (Riksdag) in Sweden in 2024

Note: Values beyond 100% are due to rounding up.

Sources: Swedish Election Authority website (2025) (www.val.se/valresultat/riksdag-region-och-kommun/2022/nuvarande-och-avgangna-ledamoter.html); Swedish Parliament website (2025) (www.riksdagen.se/sv/ledamoter-och-partier/).

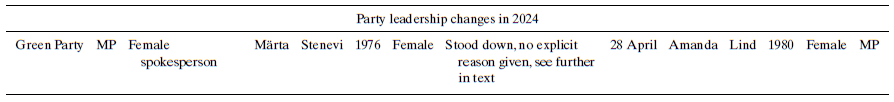

Political party report

One Swedish party changed leader in 2024. The Green Party had changed its male spokesperson from Per Bolund to Daniel Helldén in 2023 (Widfeldt Reference Widfeldt2024). On 12 February 2024, the female spokesperson since 2021, Märta Stenevi, announced her resignation. She had been on medical leave since January, and there were allegations of internal discontent with her leadership style, but no exact reason was given for her resignation. As shown in Table 4, she was replaced by Amanda Lind, who was unanimously appointed at a virtual party congress on 28 April (Olsson Reference Olsson2024). Lind was experienced, having served as party secretary from 2016 to 2019, and as Minister for Culture, Democracy and Sport in the Social Democratic-Green coalition government from 2019 to 2021. The Stenevi-Helldén leadership seemed to work well, with improved poll ratings for the party as well as the new spokespersons.

Institutional change report

There were no institutional changes in 2024.

Issues in national politics

The main event of 2024, with historical significance, was that the process to join NATO was finalised. The Swedish application had been submitted in 2022, but the ratification process proved difficult. The main obstacles were Hungary and Turkey, who had not yet ratified the Swedish application by the beginning of 2024 (Widfeldt Reference Widfeldt2024). Following a series of bilateral contacts, the Turkish ratification was completed with a presidential signature on 25 January 2024. In Hungary, the ratification was preceded by a visit to Budapest by Swedish Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson, during which the sale of Swedish-produced military equipment including SAAB Gripen planes was agreed. The ratification was concluded with a presidential signature on 5 March (Brooke-Holland Reference Brooke-Holland2024). The final step of the membership process took place on 7 March, when Kristersson handed over the accession documents to the US Secretary of State Antony Blinken at a ceremony in Washington (Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Gigova, Hanlsler and Knight2024). By this time, almost all Swedish opposition to the NATO membership had disappeared. The Left Party remained sceptical, but did not demand an immediate exit (Holmqvist Reference Holmqvist2024). Sweden had thus finally abandoned its traditional policy of military non-alignment.

A Defence Co-operation Agreement with the United States was subject to some debate but was accepted by a clear parliamentary majority on 18 June, taking effect on 15 August (Swedish Government 2024b).

Revised legislation regarding gender was adopted by Parliament on 17 April. The age limit for gender reassignment was lowered from 18 to 16, and the administrative process was simplified. After a six-hour debate, the reform was adopted with a comfortable 234–94 majority. The main opposition came from SD and KD, but there were individual dissenters in other parties (Guardian 2024).

Opinion polls indicated consistent, sometimes substantial, leads for the opposition parties. The polls were especially worrying for the governing parties L and KD. Particularly L was often below the 4 per cent representational threshold. The opposition could not, however, present a coherent government alternative; relations between and V and C being a particular source of uncertainty.

According to the National Institute of Economic Research (NIER), the economy showed signs of a ‘fragile recovery’. Gross domestic product (GDP) grew 1.0 per cent in 2024; a slight increase to 1.7 per cent being projected for 2025 (NIER 2025). Inflation, measured as 12-month changes in the Consumer Price Index, declined steadily throughout the year, from 5.4 per cent in January to 0.8 per cent in December (SCB 2025a). Possibly somewhat prematurely, Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson and Minister of Finance Elisabeth Svantesson claimed in June that the battle against inflation had been won (Kristersson & Svantesson Reference Kristersson and Svantesson2024). The central bank Riksbanken lowered the policy interest rate five times, reversing the trend from 2022 to 2023. At the beginning of 2024, it was 4.00 per cent; by the end of the year, it had sunk to 2.75 per cent (it was set to be reduced further, to 2.50 per cent, in January 2025) (Riksbanken 2025).

Unemployment continued to increase. In 2024, it was 8.4 per cent of the workforce aged 15–74, compared to 7.7 per cent in 2023 (SCB 2025b; exact estimates vary among different sources).

The public purse remained sound. The National Debt Office reported a fiscal deficit at the end of 2024 of Skr 104 billion. It was the first annual deficit since the pandemic year of 2020, but it had been expected due to the economic downturn in 2023. National debt grew from Skr 1028 billion to 1151, compared to 2023. Relative to GDP, this represented an increase of one percentage point to 18 per cent, which was still very low by international standards (National Debt Office 2025). In response to existing and future fiscal pressures, the budget framework was revised. The existing framework, introduced in the 1990s, prioritised keeping budget deficits and national debt at manageable levels. These regulations, which included a fiscal surplus target, had increasingly become regarded as out of date.

In late 2023, the government set up a Commission of Inquiry, with representation from all eight parliamentary parties, with the task to modernise the fiscal policy framework. The Commission presented a report with reform proposals on 15 November. The surplus target was replaced with a balance target, meaning that the budget must have a net balance of zero over the business cycle, starting from 1 January 2027. This would free up an extra annual Skr 25 billion for reforms and investment. A ‘debt anchor’ for the public sector, with a maximum 35 per cent of GDP, remained (Swedish Government 2024c). Six of the eight parliamentary parties were behind the Commission proposals. V and MP dissented, arguing that more room for investment should have been made available. There was also internal criticism in S, along similar lines to V and MP, but the party line was decided by the leadership, which supported the majority proposals.