Introduction

A leadership change in the Christian‐Democratic Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) in May brought a snap parliamentary election in October, in which the ÖVP become the largest party, overtaking its coalition partner, the Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ), which narrowly stayed ahead of the right populist Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ). The Greens/Green Alternative (GRÜNE) failed to achieve the entry threshold of 4 per cent, while a new party of a former Green MP got into Parliament. A rightist coalition government between the ÖVP and the FPÖ under Federal Chancellor Sebastian Kurz was concluded in December.

Election report

Parliamentary elections, 5 October 2017

After the leadership change in the ÖVP, from Reinhold Mitterlehner to Kurz, at the beginning of May (see the Political party report below) Kurz announced the end of the coalition with the SPÖ and called for premature elections to the National Council, the first chamber of Parliament, in the autumn. Its regular term would have ended in autumn 2018.

Since the previous year's leadership change in the SPÖ (Jenny Reference Jenny2017), the government parties had jockeyed for the best moment to end the coalition. The former party leaders Werner Feymann from the SPÖ and Mitterlehner from the ÖVP had trailed behind opposition party leader Heinz‐Christian Strache (FPÖ) in the polls. Christian Kern as new leader of the SPÖ then became the best rated party leader. When young and popular Foreign Minister Kurz became ÖVP party leader, the ranking changed again, but more decisively. Kurz was clearly ahead of Kern and Strache in the polls (Neuwal 2018). To increase his political leeway and signal a break with the past, Kurz did not assume the vice‐chancellorship in the government. The party's central campaign theme became taking a hard line on immigration issues. Kurz frequently reminded voters that he had opposed opening the borders during Europe's migration crisis in 2015 and managed to close the Balkan route shortly afterwards.

The Greens were caught on the wrong foot by snap elections. The election of former party leader Alexander Van der Bellen as Austria's president the year before had been the party's greatest success (Jenny Reference Jenny2017), but it depleted its financial reserves. The announcement of early elections spurred the retirement of party leader Eva Glawischnig‐Piesczek from politics shortly afterwards (see Political Party report below). The party's woes deepened after its longest serving, but contentious, MP Peter Pilz failed to win a safe seat nomination and announced his resignation. Apparently expecting a negative outcome he then quickly proceeded to set up a rival party. The liberal party, The New Austria (NEOS), benefited from the Greens’ turmoil and from Irmgard Griss, the surprising maverick candidate in last year's presidential elections, joining its list of candidates (Jenny Reference Jenny, Coller, Cordero and Jaime‐Castillo2018). The leadership changes in other parties put the FPÖ in the unusual position of campaigning with the longest serving party leader. Anticipating government membership, the party campaign stressed the experience and statesmanship of party leader Strache. The party's presidential candidate Norbert Hofer also featured prominently in the campaign. Team Stronach (TS), a rightwing populist party which won seats in the previous elections of 2013, did not contest the elections again.

Towards the end of a long election campaign, that set a new record for television candidate debates on public and private channels, the SPÖ was put on the defensive by reports of a criminal investigation against its campaign consultant, Tal Silberstein, in Israel, and revelations of ‘dirty campaigning’ experiments conducted against ÖVP party leader Kurz on Facebook (Addendum 2018). For an extended description of the electoral context and the party campaigns, see Bodlos & Plescia (Reference Bodlos and Plescia2018).

Table 1. Elections to the lower house of Parliament (Nationalrat) in Austria in 2017

Note: aNEOS had an electoral alliance with former presidential candidate Irmgard Griss and her movement ‘Female and Male Citizens for Freedom and Responsibility’.

Source: Federal Ministry of the Interior (2017).

The outcome of the election was a great success for the ÖVP, which increased its vote share from 26.8 per cent to 31.5 per cent (7.5 percentage points) and became the largest party with 62 seats. The SPÖ remained at 26.9 per cent and 52 seats and stayed narrowly ahead of the FPÖ, which also increased its vote share considerably (by 5.5 percentage points) to 26 per cent and 51 seats. NEOS obtained a slight increase to 5.3 per cent (10 seats). The new party List Pilz (PILZ) narrowly passed the 4 per cent threshold and obtained 4.4 per cent (eight seats), while the Greens spectacularly dropped from 12.4 per cent to 3.8 per cent and out of Parliament.

The formation of a coalition between the two winners of the election, the ÖVP and FPÖ, followed swiftly and a new rightist government headed by Federal Chancellor Kurz and Vice‐Chancellor Strache was sworn in on 18 December.

Cabinet report

In January, Federal Chancellor Kern presented an extensive policy programme called ‘Plan A’, whose similarity with an election programme irritated the coalition partner. Yet, at the end of the month the cabinet still managed to pass an updated government programme for the remainder of the term. After the resignation of vice‐chancellor and ÖVP party leader Mitterlehner, however, his successor, Kurz, declined the SPÖ offer to continue the coalition. He also did not assume the office of vice‐chancellor which was given instead to Minister of Justice Wolfgang Brandstetter.

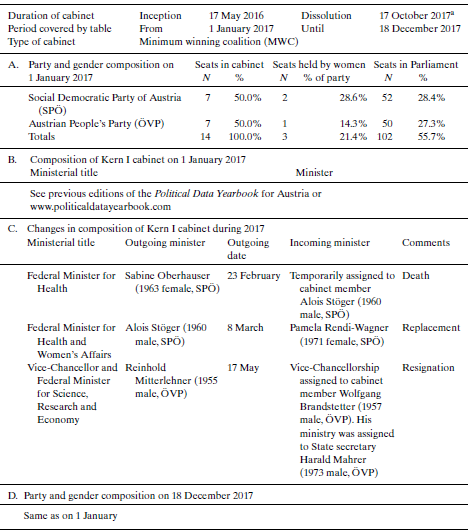

Table 2. Cabinet composition of Kern I in Austria in 2017

Note: aThe cabinet handed in its resignation two days after the legislative elections and was tasked by the president to serve provisionally until the swearing in of a new cabinet.

Sources: Federal Chancellery (2018); Österreichischer Amtskalender (2018); Austrian Parliament (2018); author's own calculations.

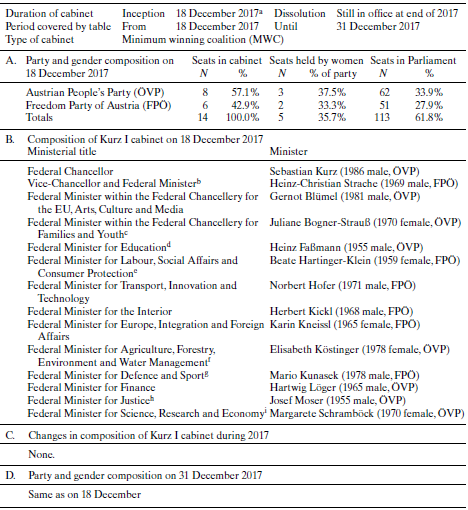

Table 3. Cabinet composition of Kurz I in Austria in 2017

Notes: aThe cabinet handed in its resignation two days after the legislative elections and was tasked by the president to serve provisionally until the swearing in of a new cabinet.

b The Federal Ministries Law amendment, passed on 20 December, came into effect on 8 January 2018. Since then renamed Vice‐Chancellor and Federal Minister for the Civil Service and Sport.

c Since 8 January Federal Ministry within the Federal Chancellery for Women, Families and Youth.

d Since 8 January Federal Ministry for Education, Science and Research.

e Since 8 January Federal Minister for Labour, Social Affairs, Health and Consumer Protection.

f Since 8 January Federal Minister for Sustainability and Tourism.

g Since 8 January Federal Minister for Defence.

h Since 8 January Federal Minister for Constitutional Affairs, Reforms, Deregulation and Justice.

i Since 8 January Federal Minister for Digital and Economic Affairs.

The number of ministers in the new government led by Kurz remained at 14 ministers. Eight ministers were nominated by the ÖVP, six by the FPÖ plus one state secretary per party. State secretaries are not members of the cabinet. The ÖVP has a state secretary Caroline Edtstadler (1981 female) in the Ministry for the Interior, with the FPÖ state secretary Hubert Fuchs (1969 male) in the Ministry for Finance. Endowed with much greater powers by the party congress (see Political party report below), Kurz recruited several ministers who were new to politics. Most of the ministerial portfolios were partly changed and ministries renamed. These changes came into effect in January 2018. Several ministers appointed a general secretary, which is a new top‐level post with line authority, to coordinate the ministry.

Parliament report

The party system in the lower house changed from six to five parties, halting the long‐term trend since the 1980s towards greater fractionalization. With the FPÖ moving into government and the other seasoned opposition party Greens gone, observers diagnosed a weaker opposition at the start of the new term. The SPÖ was slow to adapt to the role as an opposition party. PILZ got into Parliament owing much to its party leader's record as a tenacious opposition MP in committees of inquiry. However, after claims of sexual harassment of women became public, Pilz refrained from taking the parliamentary seat. Without him, the new party soon appeared rudderless. NEOS party leader Matthias Strolz became the most visible representative of the opposition in Parliament.

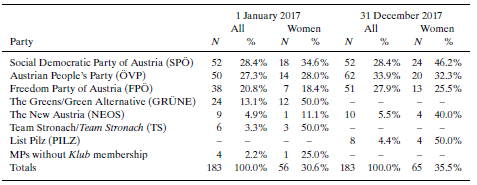

Table 4. Party and gender composition of the lower house of Parliament (Nationalrat) in Austria in 2017

Sources: Austrian Parliament (2017); author's own calculations.

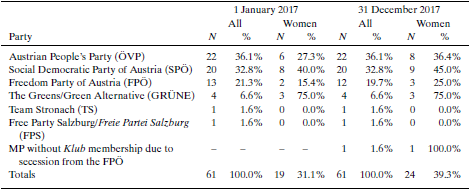

Table 5. Party and gender composition of the upper house of Parliament (Bundesrat) in Austria in 2017Footnote a

Note: aThe members of the Bundesrat are elected by the Land diets (Landtage) on the basis of the results of the Land elections.

Sources: Austrian Parliament (2017); author's own calculations.

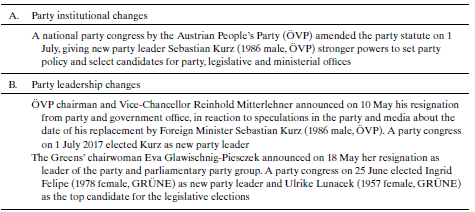

Political party report

ÖVP party leader Mitterlehner abruptly announced his resignation from all political offices on 10 May, citing the intense intra‐party and media speculation over the date of his replacement by Foreign Minister Kurz as reasons and a taunt on public television late‐night news (‘Django, the gravediggers are already waiting’) as the final straw prompting the decision. Django, a reference to an Italian western film figure, was Mitterlehner's fraternity nickname, which was widely used after he became party leader in 2016.

The party's desired successor, Kurz, demanded greater powers as a party leader, including control over party policy and candidate selection for central party, legislative offices and ministerial offices. A party statute revision granting these powers was formally passed by a party congress in July. Kurz put allies from the Young People's Party (Junge ÖVP), one of the six leagues that constitute the factionalized ÖVP, into central party positions and set out to build a ‘new People's Party’ with a visual rebranding and a policy shift. Prevention of immigration became a central plank of the election platform. Turquoise replaced the traditional black as new party colour.

Table 6. Political party changes in Austria in 2017

With parliamentary elections on the horizon, Green party leader Glawischnig‐Piesczek, announced on 18 May her resignation from all political offices, citing concerns for personal health and family. She was succeeded as party leader by Ingrid Felipe, previously regional party leader in Tyrol, and Ulrike Lunacek, an MEP, as the party's top candidate for the upcoming election. The election of former party chairman Van der Bellen to the presidency in December 2016 had been the greatest success in party history. The Greens’ annus horribilis opened with intra‐party feuds with MP Pilz and others advocating a left populist, restrictive stance on immigration, and a quarrel between the party leader and the leader of the party's youth organization. The split‐off founded by Pilz ahead of the elections contributed to the Greens losing all seats in the lower house of Parliament. The steep reduction in public party financing put the Greens into financial disarray.

Issues in national politics

Intra‐party politics played a large role in national politics in 2017 due to the abrupt resignations of the party leaders of the ÖVP and Greens. Leadership change in the ÖVP brought a major and fast revamping of the party in terms of policy focus and style, which was appreciated by the public and rearranged the starting conditions for the expected three‐party race between the ÖVP, SPÖ and FPÖ for the chancellorship. The next elections drawing nearer had, before new ÖVP leader Kurz announced the end of the coalition in May and snap elections in autumn, intensified discussions in the SPÖ and Greens on revising their respective policy positions. The SPÖ grappled with the issue of holding onto the position of no government cooperation at the national level with the FPÖ. The right wing of the party as well as the FPÖ argued that this benefited only the ÖVP. The SPÖ passed a ‘compass of values’ (Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ) 2018) in June as conditions for future cooperation with other parties, seen as a hesitant opening of the door to the FPÖ. The outcome of the elections, however, made clear that the next government would be a right‐wing coalition government. In spite of an immense interest from outside the country about the consequences of having a right‐wing party in government, the political atmosphere in Austria was rather relaxed.