Introduction

Social protection is one of the core responsibilities of governments in contemporary Western democracies, but it is also one of its central areas of political contestation. Not only was the question of redistribution at the heart of the traditional class cleavage in politics (Lipset & Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967; Roller, Reference Roller, Borre and Scarbrough1995) but welfare politics also remain contested and electorally salient (Bonoli & Natali, Reference Bonoli and Natali2012; Green‐Pedersen & Jensen, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Jensen2019; Kumlin & Goerres, Reference Kumlin and Goerres2022). Yet, beyond the supply side of politics, welfare state issues are pivotal to voters as well. Citizens often gain insight into the functioning of political systems through their interaction with the welfare state, which makes its legitimacy tightly coupled to broader political trust (Haugsgjerd & Kumlin, Reference Haugsgjerd and Kumlin2020) and satisfaction with democracy (Sirovátka et al., Reference Sirovátka, Guzi and Saxonberg2019). A critical aspect of this legitimacy, as well as part of current political debates, concerns questions about the extent to which others abuse or cheat the system (Andersen, Reference Andersen, Svallfors and Taylor‐Gooby1997; Roosma et al., Reference Roosma, van Oorschot and Gelissen2016b). Besides being an integral part of the welfare populist agenda (De Koster et al., Reference de Koster, Achterberg and Van der Waal2013), perceptions of system abuse are essential for belief in a system that delivers a just distribution of burdens where everyone contributes their fair share (Rothstein, Reference Rothstein1998).

However, despite the clear political relevance of these perceptions of system abuse, they are ill‐understood and insight into their driving forces is lacking. While studies have highlighted the relevance of political narratives among, for instance, the radical right that pit hard‐working citizens against unproductive ‘Others’ who avoid paying taxes or abuse the welfare system (De Koster et al., Reference de Koster, Achterberg and Van der Waal2013; Kochuyt et al., Reference Kochuyt, Abts and Roosma2023), we know relatively little about what shapes citizens’ perceptions of system abuse beyond the supply side of politics. While some studies focus on how socio‐economic status and ideology relate to these types of perceptions (Edlund, Reference Edlund1999; Goossen et al., Reference Goossen, Johansson Sevä and Lundström2021; Marriott, Reference Marriott2017; McArthur, Reference McArthur2021; Roosma et al., Reference Roosma, van Oorschot and Gelissen2016b), other determinants are insufficiently explored. As a result, this paper puts forward an alternative explanatory framework for perceptions of system abuse that helps to understand how they arise and persist, namely: personal experiences. Although various scholars have turned to personal experiences in order to explain political sentiments and support for redistribution (Hacker et al., Reference Hacker, Rehm and Schlesinger2013; Kumlin, Reference Kumlin2004; Margalit, Reference Margalit2013; Naumann et al., Reference Naumann, Buss and Bähr2016), they have rarely been called upon to dissect how people think about social groups (Danckert, Reference Danckert2017).

It is crucial to understand whether formative personal experiences can shape these perceptions that are at the heart of debates on the legitimacy of the political system, as they tell us whether idiosyncratic experiences can lead citizens to update their views and attitudes or whether they are set in stone through social and political socialization (Mau, Reference Mau2004; Staerklé et al., Reference Staerklé, Likki, Scheidegger and Svallfors2012). Even though these experiences embody psychological, social, economic and administrative dimensions, understanding their collective effect provides the answer to whether such experiences can activate political learning and identification processes. This could incite enduring modifications in views that go beyond individuals’ immediate circumstances and could thus be determinative for people's perceptions of others’ behaviour (Margalit, Reference Margalit2019). In other words: can, beyond abstract representations or discourses, actual experiences and everyday realities of citizens be informative of their views (Patrick, Reference Patrick2016; Shildrick & MacDonald, Reference Shildrick and MacDonald2013)?

To study this in more detail, we look at how people's experiences that bring them closer to the groups often associated with fraud influence these individuals’ perceptions of system abuse conducted within these groups. As people undergo transforming conditions and experience a shift in their economic and social status, they could adjust their views on the system as well as on the behaviour of similar others. Based on theory, two different mechanisms could be at play in linking egotropic considerations to legitimacy views. On the one hand, individuals could start to identify more closely with the groups they approach, thereby reducing perceptions of system abuse through these formative personal experiences (Maassen & De Goede, Reference Maassen and De Goede1991; McArthur, Reference McArthur2019; Roosma et al., Reference Roosma, van Oorschot and Gelissen2016b). On the other hand, citizens could distance themselves from similar others who are deemed undeserving (i.e., ‘othering’), which could go hand in hand with increased perceptions of misconduct (McArthur, Reference McArthur2019; Patrick, Reference Patrick2016; Shildrick & MacDonald, Reference Shildrick and MacDonald2013). To analyse which of these opposing theoretical propositions is most accurate, we formulate the following primary research question: How do formative personal experiences inform perceptions of system abuse?

In studying this relationship, we extend available research in three ways. First, two dimensions of system abuse are studied: perceptions of benefit abuse and tax evasion. Current literature usually only focuses on the ‘recipiency side’ by diving into perceptions of welfare benefit over‐ and underuse (Andersen, Reference Andersen, Svallfors and Taylor‐Gooby1997; Goossen et al., Reference Goossen, Johansson Sevä and Lundström2021; McArthur, Reference McArthur2019; Roosma et al., Reference Roosma, van Oorschot and Gelissen2016b), while disregarding misconduct on the ‘contribution side’ (Edlund, Reference Edlund1999; Marriott, Reference Marriott2017). Yet, both are equally important for a perceived fair balance of burdens and benefits and thus the legitimacy of the political system (Rothstein, Reference Rothstein1998). Second, instead of following the dominant focus on disadvantageous experiences, positive changes are also included in our analysis of perceptions of system abuse (Gugushvili, Reference Gugushvili2016; Jaime‐Castillo & Marqués‐Perales, Reference Jaime‐Castillo and Marqués‐Perales2019). Positive and negative formative experiences could have distinctive impacts, and it is hence relevant to disentangle both. Last, the longitudinal nature of our panel survey data supplies an important contribution to the literature. In contrast to many existing studies that use cross‐sectional data to solely study differences between groups, our analytic approach uses repeated measures from individuals via fixed effects models to also approximate the causal impact of formative personal experiences on perceptions of system abuse (Heise, Reference Heise1970; Keele, Reference Keele2015).

For our empirical analysis, three‐wave panel data (2014–2017) from Norway are used (Kumlin et al., Reference Kumlin, Fladmoe, Karlsen, Steen‐Johnsen, Wollebæk, Bugge, Haakestad and Haugsgjerd2017), which directs attention to formative personal experiences in an encompassing and social democratic welfare state (Esping‐Andersen, Reference Esping‐Andersen1990). The role of experiences is usually tested in liberal states with a less encompassing social safety net, where they could hence have a larger influence (Jaeger, Reference Jaeger2006a; Margalit, Reference Margalit2013; Rehm et al., Reference Rehm, Hacker and Schlesinger2012). In this sense, testing their role in a country with stronger social protection and higher expenditure rates might provide a more stringent test of the role of changes in the life situation (Naumann et al., Reference Naumann, Buss and Bähr2016). Before elaborating on the data and methods, the theoretical framework is outlined in more detail.

Theoretical framework

Perceptions of system abuse: Benefit abuse and tax evasion

To study how formative personal experiences affect perceptions of system abuse, we look at two separate perceptions that cover the recipiency and contributory side of welfare, respectively. Our perceptions of interest represent dimensions that shed light on different aspects of how individuals or groups can cheat the system: welfare benefit abuse and tax evasion. Despite highlighting distinct characteristics, these two dimensions have in common that they are both financial crimes with similar victims, namely the state and society in general (Marriott, Reference Marriott2017). In addition, both perceptions are equally crucial in determining the legitimacy of the welfare state and political system more broadly (Roosma et al., Reference Roosma, van Oorschot and Gelissen2016a, Reference Roosma, van Oorschot and Gelissen2016b; Rothstein, Reference Rothstein1998). Besides believing in the capacity of welfare policies to implement benefits efficiently and effectively without abuse in order to consider them as just, citizens should also consider a just distribution of burdens, whereby everyone contributes their fair share. This perception that others are not free‐riding and contributing sufficiently is crucial for consenting to the tax system generally and for accepting one's own burden (Liebig & Mau, Reference Liebig, Mau, Mau and Veghte2007).

However, there are also a number of characteristics that are fundamentally different for the two types of perceptions of system abuse. To begin with, to study benefit abuse perceptions, we look particularly at perceptions of overuse, which imply that people take up benefits they do not deserve, instead of underuse, which encompasses the non‐take‐up of benefits (Roosma et al., Reference Roosma, van Oorschot and Gelissen2016b). Given this focus on overuse, benefit abuse here is especially oriented at the ‘demand’ or ‘recipiency’ side of the welfare state, whereby questions arise as to whether certain groups are taking out too much in relation to what they contribute to the system. In this sense, those who commit benefit abuse are seen as ‘takers’ and the gaze is often oriented towards the ‘receiving side’ in society that benefits from redistribution. In addition, despite the common denominator, perceptions of tax evasion also have several distinct characteristics. Tax evasion is more tied to the ‘supply’ or ‘contribution’ side of the welfare state, as it implies not giving the money that you owe to the state instead of actively taking resources out of the system (Marriott, Reference Marriott2017). While resources are still illegitimately denied from society and the social system, tax evasion can be more strongly perceived as keeping the assets citizens have earned or worked for themselves. This is also inextricably bound up with a perception of tax evasion as a ‘white‐collar crime’, which is seen as something that is mostly done by those who are on the contributing side of society (Croall, Reference Croall2001; Marriott, Reference Marriott2017).

In sum, both dimensions of system abuse shed light on different types of social groups (recipients vs. contributors) that are important in relation to abuse perceptions and welfare legitimacy.

Conceptualizing formative personal experiences

To understand these perceptions, we introduce the concept of formative personal experiences, which can be defined as personal events that trigger a series of psychological, social and economic processes which may change an individual's outlook on the world around them. These experiences can be layered in the sense that they, for instance, can both encompass an administrative change as well as a psychological or economic shift in one's personal situation. In the present analysis, we are interested in whether a holistic personal experience – regardless of the multitude of layers involved – results in a new outlook on perceptions of system abuse. Understanding the role of these formative personal experiences is crucial to gain knowledge on whether citizens can still update their views on political issues based on their own relevant events or whether socializations in political narratives set unchangeable precedents.

To study this, we mirror the divide in perceptions of system abuse between the demand and supply side of the welfare state in the operationalizations of formative personal experiences. Specifically, we argue that becoming a benefit recipient can alter perceptions of benefit abuse, and experiencing income change can affect views on tax evasion. Research has tried to disentangle how precariousness and experiences of disadvantage consolidate into various types of welfare and political attitudes (Danckert, Reference Danckert2017; Hacker et al., Reference Hacker, Rehm and Schlesinger2013; Naumann et al., Reference Naumann, Buss and Bähr2016; Rehm et al., Reference Rehm, Hacker and Schlesinger2012; Soss, Reference Soss1999). However, as an additional dimension of personal experiences, income increases are also examined as a positive formative personal experience that has the potential to shape perceptions of tax evasion. Although representing positive versus negative experiences that involve different ends of the welfare state – the recipiency versus contribution side – the two experiences also share certain characteristics. They both imply a change of material means and social status to varying degrees. However, they do differ in a number of points.

The experience of dependence on welfare benefits places individuals within society's lower social strata, highlighting how adverse experiences or possible grievances can shape perceptions of benefit abuse. Despite the relief provided by high replacement rates of income which cushion dramatic material blows, welfare beneficiaries endure a demoted social status and associated stigma compared to the working population. This is largely due to their reliance on redistributive state mechanisms financed by contributors, and the fact that their deservingness is continuously evaluated (Laenen & Roosma, Reference Laenen, Roosma, Yerkes and Bal2022; van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2000). Moreover, becoming a benefit claimant unfolds as a particularly layered personal experience (which is less so in the case of income changes). While this research cannot delve deeply into this division due to empirical constraints, it is essential to recognize that becoming a benefit claimant involves an interplay between personal and administrative experiences. First, a grievance occurs for which the benefit is sought, such as becoming unemployed, disabled or sick – an experience that can be dramatic and hence profoundly formative in itself. Second, the administrative experience of claiming and retaining benefits can influence attitude formation. This is true both in terms of explicitly categorizing the claimant into a specific social group with similar experiences and in terms of the potential fairness or lack thereof in the administrative procedure (Danckert, Reference Danckert2017; de Blok & Kumlin, Reference de Blok and Kumlin2022). Factors deemed impactful on procedural fairness outcomes, such as respectful treatment (Rothstein, Reference Rothstein2009) and the ability to voice input into the process (Hirschman, Reference Hirschman1970), may also sway how welfare beneficiaries see themselves or their group.

Naturally, an experience of a positive income change is directly associated with ascending towards the welfare contributors in society, especially in progressive tax systems where income increases imply higher tax rates and hence larger contributions. This is quite the opposite of descending into welfare dependency, which encompasses becoming part of the recipiency side of state support. Moreover, experiencing a financial upturn is not typically entwined with extensive administrative procedures or interactions with policy enforcement. Although income increases could potentially affect taxation, the requirement to pay taxes applies practically to everyone. Nevertheless, increasing material means may kindle a sense of boosted social status, possibly instigating a conscious shift into a new social group adherence – that of the contributors to society. However, the overarching experience of a positive income change is associated with a more diffuse social grouping compared to the starker demarcation connected with transitioning into welfare dependency.

The mechanisms of formative experiences: Identification or ‘othering’?

In the literature, the role of experiences is usually framed by self‐interest theory, which posits that citizens support the policies that maximize their personal benefits and material interests (Jaeger, Reference Jaeger2006b; Kangas, Reference Kangas1997). The argument is that support for redistribution and the political system is, for instance, higher among groups experiencing disadvantageous transitions, as they have a stronger interest in an encompassing state that protects them against social risks (Helgason & Rehm, Reference Helgason and Rehm2023; O'Grady, Reference O'Grady2019). However, the literature does not provide a suitable theoretical framework for the link between formative personal experiences and perceptions of system abuse. Moreover, the commonly applied rational choice arguments do not adequately address the dependent variable. As a result, a distinct theoretical framework is required that can explain how personal experiences might impact people's perceptions of system abuse. Although other mechanisms are certainly viable as well, we focus on theories that can help explain the psychological processes through which benefit recipiency and income increases link to perceptions of system abuse. In this regard, two distinct mechanisms are possible: formative experiences could lead to stronger identification with groups who may commit abuse or could instil a sense of ‘othering’.

First, the identification perspective predicts that the closer people move towards the situation of the concerned groups, the less they will perceive abuse due to an increased capacity to put themselves in their shoes (Maassen & De Goede, Reference Maassen and De Goede1991; McArthur, Reference McArthur2019; Roosma et al., Reference Roosma, van Oorschot and Gelissen2016b). When people's objective positions make them belong to certain groups or at least occupy a more similar status, they can start to identify with these groups as a type of self‐serving bias that gives their own situation more meaning and a sense of belonging. According to social identity theory, this identification then leads individuals to attribute more positive characteristics to the groups they belong to (Danckert, Reference Danckert2017; Tajfel, Reference Tajfel, Turner and Giles1981). The positive bias should lead to weaker perceptions of these groups cheating the system. This can be further strengthened by social learning processes, whereby the formative experience could help individuals understand more about the causes of their situation and recalibrate their own interests and ideas (Danckert, Reference Danckert2017; Margalit, Reference Margalit2013). In this sense, stereotypical images of groups who are believed to cheat the system could be challenged when people start to belong more strongly to these respective groups.

Alternatively, scholars have pointed to processes of ‘othering’ instead of identification. ‘Othering’, sometimes referred to as self‐group distancing, encompasses a process whereby individuals increasingly differentiate and demarcate between groups, and distance themselves (‘the deserving’) from those with a similar social status who are considered to be immoral and undeserving of acquiring public resources (Patrick, Reference Patrick2016). As opposed to the identification perspective which is applied to establish a positive self‐identity by praising one's group, ‘othering’ is exercised to do the same by introducing distance between oneself and the group one, on paper, belongs to (van Veelen et al., Reference van Veelen, Veldman, Van Laar and Derks2020). Derks et al. (Reference Derks, Van Laar and Ellemers2016) argue that ‘othering’ takes place in three main ways, being (1) physical or psychological distancing from in‐group members, (2) presenting oneself as someone not in their objective in‐group and (3) endorsing stereotypical criticism of their own group and thus legitimizing the current inter‐group hierarchy. Thus, in order to retain a positive self‐image, formative personal experiences could also lead to stronger ‘us’ versus ‘them’ divides even within the in‐group (Shildrick & MacDonald, Reference Shildrick and MacDonald2013) and hence to stronger perceptions of system abuse due to ‘I'm not like the others’ attitude.

Based on these two experiences that each relates to a different dimension of perceptions of system abuse and the opposing theoretical mechanisms, the following hypotheses are formulated:

-

Hypothesis 1a. Becoming dependent on welfare benefits decreases perceptions of benefit abuse [Identification hypothesis]

-

Hypothesis 1b. Becoming dependent on welfare benefits increases perceptions of benefit abuse [‘othering’ hypothesis]

-

Hypothesis 2a. Positive income changes decrease perceptions of tax evasion [Identification hypothesis]

-

Hypothesis 2b. Positive income changes increase perceptions of tax evasion [‘othering’ hypothesis]

While we expect these changes in perceptions of benefit abuse to occur across different groups experiencing benefit recipiency or income changes, it is possible that some of these relationships are more or less pronounced depending on the economic or social starting point of an individual. The net impact of formative experiences – whether arising from alterations in income itself or due to receiving benefits – does not uniformly hold the same weight across different socioeconomic strata (Bartels & Jackman, Reference Bartels and Jackman2014; Gerber & Green, Reference Gerber and Green1998). For instance, when individuals already have high incomes and have hence already for a long time belonged mainly among the contributors of the welfare state, a formative experience of having an income increase could be less influential in triggering identification or ‘othering’ with contributors in wealthier strata. As argued by Helgason and Rehm (Reference Helgason and Rehm2023, p. 268), ‘the relationship between income and attitudes is anchored by initial income but is incrementally updated as individuals learn more about their realized income group’. Thus, our inquiry into the four hypotheses outlined also delves into groups marked by differing initial income levels to uncover potential variations in the effects. Yet, as it is not entirely clear a priori how this would impact the mechanisms of identification or ‘othering’, this is treated as an exploratory empirical inquiry without formal hypotheses explicitly being spelled out.

The Norwegian context

Some fundamental components of the Norwegian context, in which our hypotheses are tested, may dampen the extent to which personal experiences generate substantial attitudinal change. To begin with, the welfare state design of our case can affect to what extent experiences shape perceptions of system abuse. In social democratic welfare states characterized by predominantly universal access to welfare services, there tends to be comparatively lower suspicion surrounding benefit uptake and reduced stigmatization compared to their liberal counterparts. This dynamic could generally make perceptions of abuse and changes thereof less likely (Roosma et al., Reference Roosma, van Oorschot and Gelissen2016b; Rothstein, Reference Rothstein1998). In addition, the benefit levels and taxation system of the Norwegian welfare state could also downplay the role of formative personal experiences on the perceptions of system abuse. For instance, sickness benefits are uniquely generous, and even during periods of unemployment individuals retain a considerable share of their earnings compared to other countries (OECD, 2022; Sørvoll, Reference Sørvoll2015). The tax system exhibits mild progressivity and quite extensive coverage, evident in Norway's status as one of Europe's countries with the highest tax‐to‐GDP ratio. Like in other Scandinavian countries, Norway operates a dual‐income tax system that consists of broad tax bases, progressive income taxation and a minor proportional tax on capital (Denk, Reference Denk2012). This relatively comprehensive taxation and redistribution structure presumably limits the disruptive impact of personal income changes or benefit recipiency.

However, beyond the welfare state design, there is a ‘culture of trust’ in Norway, which might decrease the potential for changes in perceptions of system abuse. Roosma et al. (Reference Roosma, van Oorschot and Gelissen2016b), for instance, illustrate that Norwegian perceptions of over‐ and underuse of welfare benefits are among the lowest in Europe, showing that people seem to have quite a lot of faith in claimants to be honest and fair (see also Kumlin & Goerres, Reference Kumlin and Goerres2022). Similarly, both social and political trust is well‐above average in Norway and even among the highest in Europe (Freitag & Bühlmann, Reference Freitag and Bühlmann2009; Marien, Reference Marien2011), pointing to more general trust in institutions and the fair intentions of generalized others. In this context, trust could be quite robust and there could be relatively high faith in the morality of both system recipients and contributors, which makes it less likely that large changes occur in these perceptions of system abuse as a consequence of personal experiences or changing life situations.

However, despite formative experiences potentially having a weaker impact relative to other contexts, certain contextual factors of the Norwegian case could still make formative personal experiences relevant in absolute terms and even make identification or ‘othering’ as underlying mechanisms more plausible. On the one hand, it is possible to argue that identification is the more likely mechanism to take place in the trusting, universal context at hand, as a prerequisite for ‘othering’ to occur would be that welfare recipients or certain income groups are socially stigmatized. On the other hand, while people in Norway are indeed relatively less suspicious of benefit claimants and tax evasion compared to other countries as previously explained, absolute levels of suspicion are still substantial – over half of the sample used in this study believes that benefit abuse and tax evasion are rather or very common in Norway (see below). Furthermore, welfare state issues are relatively strongly politicized in Norway (Kumlin & Goerres, Reference Kumlin and Goerres2022), which can make perceptions of abuse more salient and hence more viable to ‘othering’ mechanisms. In addition, while the Norwegian welfare state is relatively universal compared to other European welfare states, research shows that modern social democratic welfare states still combine universalism with low‐income targeting (Brady & Bostic, Reference Brady and Bostic2015; Kuivalainen & Nelson, Reference Kuivalainen, Nelson, Kvist, Fritzell, Hvinden and Kangas2011). This might accentuate concerns about abuse, potentially amplifying public apprehensions and ‘othering’ dynamics.

In sum, the Norwegian context stands as a more stringent test for the role of formative experiences compared to other contexts. However, the interplay of its targeting, politicization, and the overall perceptions of system abuse pave the way for the potential occurrence of both identification and ‘othering’ responses to formative experiences.

Data and methods

Data

To assess our hypotheses, we use the Norwegian panel survey ‘Support for the Affluent Welfare State (SuppA)’ (Kumlin et al., Reference Kumlin, Fladmoe, Karlsen, Steen‐Johnsen, Wollebæk, Bugge, Haakestad and Haugsgjerd2017). The survey was carried out by TNS Gallup among the members of its access panel who were recruited via a two‐stage sampling procedure of initially selecting 61 communities (27 municipalities and 34 urban districts in the four largest cities), which were divided into strata proportional to their size, and subsequently drawing a random sample of individuals from these strata of communities. Individuals completed a questionnaire on their demographics and social status as well as on their social and political beliefs, which was administered using Computer Assisted Web Interviewing (CAWI). To follow up on participants across time, three waves were executed (the first wave in 2014, the second wave in 2015 and the third wave in 2017). While 5420 individuals responded in the first wave, 5008 participated in the second wave.Footnote 1 The 2847 respondents who participated in both waves one and two (i.e., roughly 53 per cent of the wave 1 participants), were invited to the third wave, leading to 1,560 individuals who completed all three waves. The descriptive statistics are displayed in Tables S3 and S4 in the Online Appendix. Although no clear changes in descriptive statistics for the independent, dependent and control variables can be found, an increase in the average age across waves is observable. This increase partially stems from individuals aging during the survey's duration, which includes 1‐ or 2‐year intervals between waves. However, it could also indicate a potential attrition of younger respondents. Although we apply weights (as suggested by Gibbons et al., Reference Gibbons, Suárez Serrato and Urbancic2019) to account for selective non‐response and include age as a control variable, this potential attrition poses a limitation in the dataset.

Indicators

Dependent variables

We use two dimensions of perceptions of system abuse as the dependent variables – benefit abuse and tax evasion. First, on the ‘recipiency side’ of welfare, the analyses zoom in on perceptions of benefit abuse, which is measured by a single item probing to what extent people believe that there is abuse of sickness benefits. Specifically, individuals are asked to what extent they think it is common or uncommon that people living in Norway ‘remain at home and receive sick benefit, even though they could, in reality, have been working’.

Sickness benefits do not refer to absenteeism or use of employee sick days, but are formally administered by a medical doctor and paid out by the Norwegian welfare state after the first 2 weeks of sickness. As a result, the item wording goes beyond a mere misuse of employee sick days but is fundamentally connected to welfare overuse. Responses are administered on a four‐point scale (1 = Very uncommon; 4 = Very common).Footnote 2

As a separate second dimension, representing the ‘contribution side’ of welfare, we look into citizens’ perceptions of tax evasion as a form of system abuse. The employed measure asks respondents to what extent they think it is common that people ‘misreport information about their economic situation in order to avoid taxes or fees’. As with the benefit abuse item, individuals can choose from a four‐point scale (1 = Very uncommon; 4 = Very common).Footnote 3

Independent variables

To determine to what extent changes in one's life situation can influence these perceptions of abuse, we focus on two distinct types of formative personal experiences. First, becoming dependent on benefits is linked to perceptions of fraudulent behaviour with these types of welfare schemes. This is measured by asking respondents whether they themselves have received ‘sick pay/sickness benefits’, ‘unemployment benefits’, ‘disability benefits’ or ‘social assistance’ in the last 12 months. The resulting dummy is coded one for personally receiving at least one type of these benefits, while zero indicates the reference group, including those without such experience.Footnote 4 All types of benefits are pooled together, and they jointly cover the crucial welfare state domains – sickness and unemployment (Hacker & Rehm, Reference Hacker and Rehm2022).

Second, perceptions of tax evasion are examined in relation to income change. Respondents were asked to indicate their gross personal income in each wave by choosing from nine categories: Below 200.000 kroner, 200.000–299.999 kroner, 300.000–399.999 kroner, 400.000–499.999 kroner, 500.000–599.999 kroner, 600.000–699.999 kroner, 700.000–799.999 kroner, 800.000–999.999 kroner and 1.000.000 kroner or more. For the cross‐sectional between‐group analysis, operationalizing income change involves determining the difference in reported personal income categories between two subsequent survey waves, resulting in two dummies for increase and decrease, using no change as the reference for both groups. For the within‐individual analyses, tax evasion attitudes are regressed directly on the income group. The inclusion of two‐way fixed effects for individuals and time allows the coefficients to be interpretable as the effect of a one‐unit income increases over one period.

One type of conducted investigation examines between‐group differences via a cross‐sectional analysis. Given this methodological approach, the analysis assesses the robustness of the findings against potential confounding variables by including several control covariates: age, gender (female as the reference category), education, personal income and political ideology. Education is included as a metric variable on a five‐point scale, with the following categories: primary school, secondary education, vocational education, university (bachelor) and university (master or higher). The level of personal income (instead of only change) is also included as a metric variable on a one to nine scale (see categorization above). Political ideology is measured as left‐right self‐placement on an 11‐point scale (0 = left; 10 = right).

Statistical modelling

Two modelling approaches are used to investigate the role of formative experiences on perceptions of system abuse. First, cross‐sectional analyses are conducted to compare individuals with and without formative personal experiences. Two regression models are estimated per type of experience – benefit recipiency and income change. The first model includes solely the main variables of interest, while the second adds control covariates to assess the effects’ robustness against potential confounders. These models use a between estimator with pooled data from three waves, including survey wave fixed effects and individual‐level clustered‐robust standard errors to control for contextual and serial correlation variations. Estimated coefficients represent average scores on the dependent variable for a specific group while holding the control covariates constant (Petersen, Reference Petersen, Hardy and Bryman2004).

Second, the panel data structure is used to analyse within‐individual differences over time. Two‐wave fixed effects models are estimated – using individual and survey wave (period) fixed effects – to eliminate all time‐constant factors and control for individual‐specific heterogeneity. Hence, this approach concentrates on changes in perceptions of system abuse due to formative personal experiences (Andreß et al., Reference Andreß, Golsch and Schmidt2013). Two models are estimated: one linking changes in benefit recipiency to perceptions of benefit abuse and another linking income changes to perceptions of tax evasion. Coefficients represent the within‐individual difference in their perception of system abuse attributed to their formative personal experience relative to their perception before this experience (Mummolo & Peterson, Reference Mummolo and Peterson2018). Additionally, the analysis employs clustered standard errors at the individual level to account for serial correlation. Both analyses apply weights to manage selective non‐response (as suggested by Gibbons et al., Reference Gibbons, Suárez Serrato and Urbancic2019).

Results

Descriptive overview of perceptions of system abuse

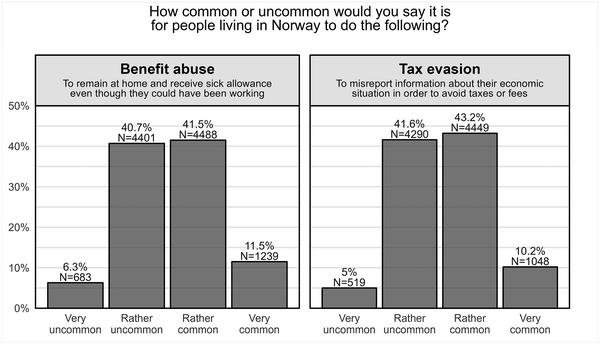

As a first step, Figure 1 is presented to provide a brief descriptive overview of the distribution of the two main dependent variables – perceptions of welfare abuse and tax evasion.Footnote 5 The frequencies reveal that perceptions concerning both the recipiency and contribution sides of welfare are relatively common. Regarding welfare benefit abuse, only 6.3 per cent of respondents indicated that it is very uncommon, while more than half (53.0 per cent) indicated that it is either rather common or very common. Despite Norway scoring relatively low on perceptions of welfare abuse in contrast to other European countries (Roosma et al., Reference Roosma, van Oorschot and Gelissen2016b), this highlights the widespread nature of these perceptions, even within a social democratic welfare regime.

Figure 1. Perceptions of benefit abuse and tax evasion in Norway: Distribution of survey responses. Based on descriptive statistics from Table S3 in the Online Appendix.

A similar pattern emerges for tax evasion, with 5.0 per cent indicating that it is very uncommon, 41.6 per cent stating that it is rather uncommon, yet more than half (53.4 per cent) perceiving it as rather or very common. Hence, these prevalent perceptions of abuse on both the input and output of the welfare state are relatively high, even in the highly trusting society of Norway (Freitag & Bühlmann, Reference Freitag and Bühlmann2009; Marien, Reference Marien2011). These two types of perceptions correlate at a level of approximately r = 0.58, indicating a close connection between both forms of abuse. However, it is still relevant to examine them separately, considering that both perceptions of system abuse are oriented towards different groups (contributors vs. recipients), which may exhibit different influences of the formative experiences based on different trends of identification or ‘othering’.

Within‐ and between‐individuals analyses on the impact of formative personal experiences

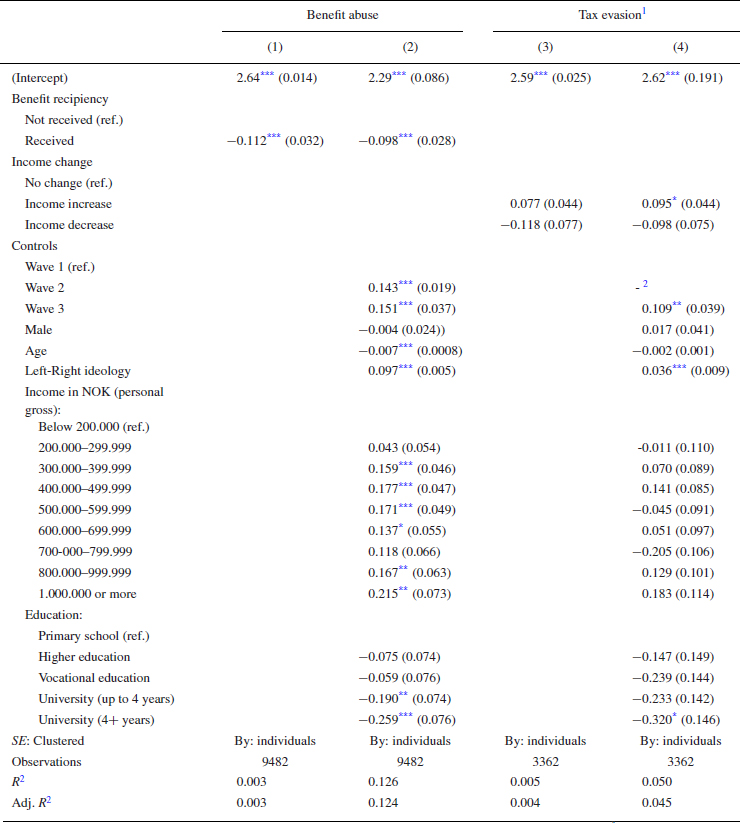

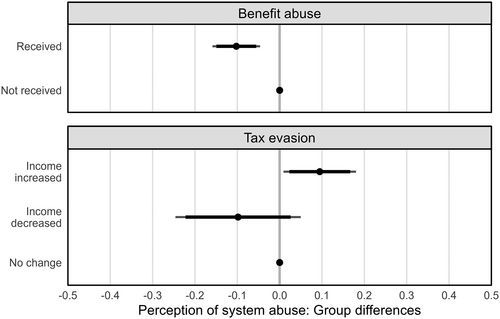

Following the modelling strategy, we first present a cross‐sectional analysis using the between estimator, of which the results are displayed in Table 1 and relevant coefficients are visualized in Figure 2.

Table 1. Between‐group analysis of formative experiences on perceptions of system abuse

Note: Coefficients are OLS regression estimates with individual cluster‐robust standard errors in parentheses. 1 Sample sizes for the tax evasion analysis are notably smaller. This limitation stems from the need for at least two subsequent waves to compute income changes, leading to the exclusion of many individuals from the analysis. Conversely, for benefit recipiency, a single wave suffices as it pertains to an experience within the last twelve months. Note that the absolute level of income is also included in these models to control for individuals’ initial income status before they experience an income change. 2 Since the ‘income change’ variable is based on two consecutive survey waves, a dummy for wave 2 is removed because of collinearity. Thresholds for statistical significance ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Figure 2. Cross‐sectional analyses: Between‐group group differences in formative experiences on perceptions of system abuse. The horizontal lines represent 90 per cent confidence intervals (black line) and 95 per cent confidence intervals (grey thinner edges).

To begin with, individuals who received a welfare benefit tend to perceive approximately 0.1 point lower levels of benefit abuse, which translates to about a 3.3 per cent effect on a 1‐to‐4 point, compared to those who did not receive any support (see models 1 and 2 in Table 1). This implies that reliance on the welfare state lessens the perception that similar peers abuse the system. Hence, such findings support hypothesis 1a, grounded in the identification with other recipients’ perspectives, and contradict hypothesis 1b, which suggests the ‘othering’ mechanism. The between‐group difference does not change much after control variables are added in model 2, suggesting that this trend is robust towards these potential confounders.

Moving on to perceptions of tax evasion, the income changes are modelled using two dummies to examine the effects of increase and decrease separately. While the coefficient is not significant in the base model including only the main variables of interest (3), the results from the multivariate model (4) reveal a significant influence of income increases on perceptions of tax evasion. Although the coefficients are of comparable magnitude to those observed in benefit abuse (approximately 0.1 points, translating to a roughly 3.3 per cent increase on the provided 1‐to‐4 point scale), individuals who have experienced an income increase exhibit higher rather than lower perceptions of tax evasion and financial misreporting compared to those with a stable income. These findings go against hypothesis 2a but are consistent with the ‘othering’ hypothesis (2b), proposing that these individuals increasingly adhere to the belief that similar individuals who are on the contributing side of welfare redistribution are more likely to cheat the system. Conversely, a decrease in income level seems to correlate with reduced perceptions of system abuse of roughly similar magnitude, although this effect is not statistically significant. As demonstrated in Figure 2, the group experiencing income decrease presents a substantially wider confidence interval due to its smaller size (comprising only one‐third of the respondents in the income increase group; N = 375 vs. N = 996, respectively; see Table S3 in the Online Appendix).

Shifting our attention to the control variables, we observe that older and highly educated individuals are generally less perceptive of benefit abuse, while individuals with higher incomes and right‐wing political affinities perceive higher levels of benefit misconduct. These findings largely align with previous research, illustrating that those in similar socio‐economic positions and left‐leaning political attitudes tend to be more sympathetic towards welfare claimants (Roosma et al., Reference Roosma, van Oorschot and Gelissen2016b). The influence of educational attainment is somewhat counter‐intuitive, but this has been attributed more to the socially liberal attitudes of highly educated individuals rather than their socio‐economic status (McArthur, Reference McArthur2021). Concerning perceptions of tax evasion, fewer predictors are significant: only education and political ideology correlate with these perceptions. Similar to the pattern observed with welfare abuse, right‐leaning and less‐educated individuals perceive higher levels of system abuse.

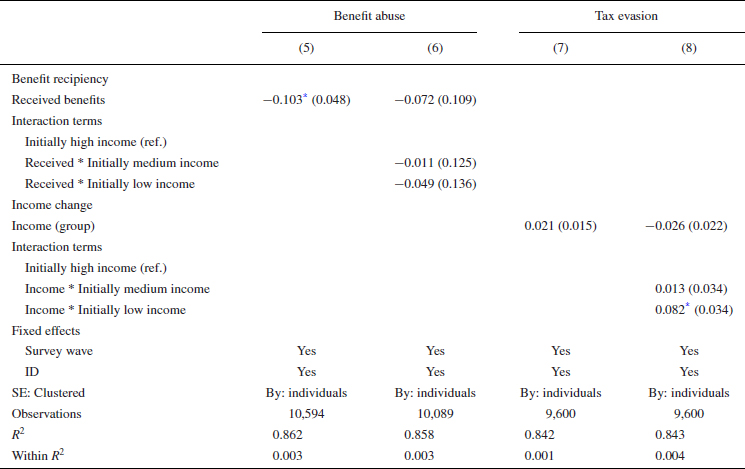

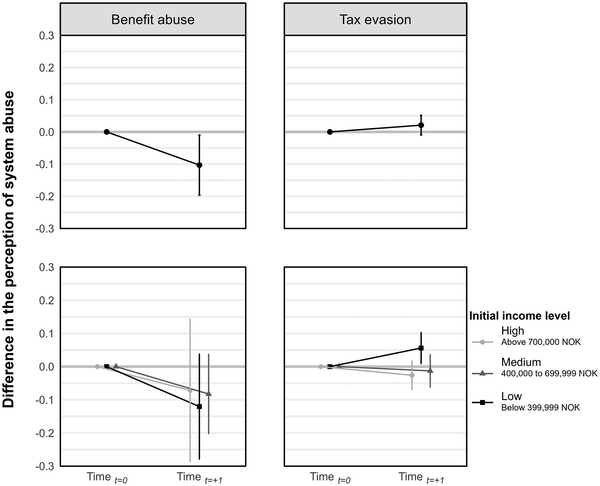

In the next stage, we use an advanced causal identification strategy by analysing the within‐individual differences over time. These differences are estimated using two‐way fixed effects models (incorporating individual and survey wave/period fixed effects), which hold both time‐invariant and individual‐specific factors constant.Footnote 6 This method allows for a more reliable causal analysis and offers a more nuanced understanding of how formative personal experiences influence individuals’ welfare abuse perceptions. In this part of the analysis, we also explicitly test for the starting point of individuals and include effect heterogeneity with income levels. The findings of the within‐individual analysis are presented in Table 2 and Figure 3.

Table 2. Two‐way fixed effects models: The effect of formative personal experiences on within‐individual differences in perceptions of system abuse.

Note: Coefficients are OLS regression estimates with individual cluster‐robust standard errors in parentheses.

Thresholds for statistical significance are ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Figure 3. Within‐individual marginal effects of formative experiences on perceptions of system abuse based on coefficients from Table 2. Vertical lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Models 5 and 7 in Table 2 regress abuse perceptions on benefit recipiency and income changes, respectively. The results reveal a pattern somewhat resembling the prior between‐group analysis. Those who begin to receive benefits exhibit a decrease in their perceptions of benefit abuse (see model 5 in Table 2). The coefficient, representing the average within‐individual difference among the group of new welfare beneficiaries, is approximately −0.1 (p < 0.05). This roughly translates to a 3.3 per cent effect on the provided 1‐to‐4 point scale. This effect magnitude strikingly parallels the between‐group difference observed in the previous part of the analysis. This relationship is again in line with hypothesis 1a and argues in favour of the identification perspective.

Shifting the focus to income changes, the general within‐individual analyses do not substantiate the findings from the cross‐sectional analysis related to income changes and corresponding perceptions of tax evasion. Although the coefficient suggests that a positive income change may marginally increase perceptions of tax evasion by around 0.02 points (translating to a negligible 0.7 per cent effect on the provided 1‐to‐4 point scale; see model 7 in Table 2), the coefficient lacks statistical significance.

Models 6 and 8 further investigate these effects by examining its heterogeneity across income groups prior to experiencing the formative personal experience. This is accomplished by introducing an interaction term between the benefit recipiency dummy variable or the income variable, and three income levels – low, medium and highFootnote 7 ‐ which were measured before the formative personal experience occurred. For benefit recipiency, none of the coefficients are statistically significant, suggesting that what is substantively important is the overall impact of benefit recipiency, irrespective of the economic starting point. However, in model 8, which explores the effect heterogeneity across the (prior) income groups for tax evasion, it is revealed that an income increase represents a substantially significant formative personal experience for the attitudes within the initially low‐income group. Individuals in this group tend to express higher perceptions of tax evasion by approximately 0.8 points, signifying about a 2.7 per cent effect on the provided 1‐to‐4 point scale. This finding supports the ‘othering’ hypothesis (2b) only for low‐income individuals, wherein members of this specific group adopt ‘I'm not like the others whose income increases, and they avoid taxes’ attitudes. There might be multiple reasons for this. First, the experience of an income increase among those with lower incomes might imply a stronger shift towards the contribution side of welfare, relative to those with higher incomes who have presumably been on the contributing side for longer and might hence change their opinions to a much lesser extent. In addition, as the income measure categorizes individuals into nine groups separated by 100,000 NOK gaps, those with the lowest initial income would have experienced the largest percentage change relative to their prior income (see Table S2 in the Online Appendix). This could also explain why the effect of income change is most substantial for this group.

Robustness check: Flipped models

As a robustness check, we also conduct the models with flipped dependent variables, examining how benefit recipiency influences tax evasion and how income changes affect perceptions of benefit abuse. As this test inspects the role of formative personal experiences in changing perceptions towards an out‐group instead of the individual's new in‐group, it does not directly test the theoretical mechanisms of identification and ‘othering,’ which are central to our theoretical framework. However, it does enable us to determine whether these experiences influence views on system abuse more broadly, or only towards one's ‘in‐group.’ The results of these flipped models are displayed in the Online Appendix, specifically Tables S6 and S7.

The cross‐sectional between‐group analysis in Table S6 shows that individuals who received benefits tend to have weaker perceptions of tax evasion, but these coefficients are statistically insignificant in both the bivariate and multivariate models (models S3 and S4, respectively). Regarding income changes, individuals experiencing an income increase have a significantly higher perception of welfare abuse in the baseline model (S5), but the coefficient becomes substantially weaker and statistically insignificant in the multivariate model (S6). This indicates that, at a cross‐sectional level, benefit recipency and income changes mainly explain perceptions related to the group individuals newly belong to, rather than perceptions about an out‐group.

However, the two‐way fixed effects models revealing within‐individual effects presented in Table S7 showcase a slightly different trend. It becomes apparent that individuals who start receiving a benefit tend to develop statistically significantly weaker perceptions of tax evasion. This suggests that not only do perceptions towards the group one start to belong to change but there might also be an influence on perceptions of system abuse more broadly. One possible explanation is that lower perceptions of benefit abuse may spill over to other groups or that there is an overall increase in trust in the social system after receiving some form of welfare benefits. Regarding income changes, we do not observe any significant relationship with perceptions of benefit abuse. The interactions with initial income levels also indicate that there is no substantial effect heterogeneity in these relationships based on prior income levels. Therefore, we can conclude that there is some evidence suggesting that individuals who start receiving benefits may become less perceptive of system abuse in general. However, the most consistent effects are observed when examining perceptions about the group (either recipients or contributors) one gets closer to, as we do in the main analysis included in this research.

Conclusion

Worries that others may be cheating the system and that burdens are unevenly distributed across the population are central to current political debates and can be erosive for state legitimacy (De Koster et al., Reference de Koster, Achterberg and Van der Waal2013; Ervasti, Reference Ervasti, Ervasti, Andersen, Fridberg and Ringdal2012; Roosma et al., Reference Roosma, van Oorschot and Gelissen2016b). Yet, despite their importance, it is unclear whether, beyond general long‐term socializations and political discourses, individual idiosyncratic events can form these perceptions of system abuse. Addressing these topics, this paper introduces formative personal experiences as a theoretical framework to elucidate how individuals perceive cheating within the welfare state among fellow group members. Specifically, the research examines two types of formative personal experiences: becoming dependent on welfare benefits and encountering income changes – both linked to two distinct dimensions of welfare abuse: perceptions of benefit abuse and tax evasion, respectively. According to the theoretical reasoning, these formative personal experiences might prompt individuals to identify more with the group that receives welfare benefits or with those who contribute to the system, both of which may engage in misconduct. Alternatively, an equally plausible mechanism is ‘othering,’ wherein individuals increasingly distance themselves from other similar group members who, however, are perceived as ‘the others who cheat the system’.

Based on an analysis of three‐wave panel data collected in Norway (2014–2017), the findings revealed that individuals becoming welfare benefit recipients tend to perceive less abuse in the welfare system. This aligns with the identification hypothesis, positing that as people assimilate into the status of a particular group, their increased identification with the in‐group may reduce common negative stereotypes associated with that group. Concerning welfare benefit abuse, personal experiences are found to improve people's perception of misconduct across all conducted empirical tests, including those employing enhanced causal identification strategies. Notably, at the within‐individual level, receiving a benefit also reduced perceptions of tax evasion, indicating that this experience fosters decreased perceptions of system abuse more broadly, extending beyond the specific group (the recipients of redistribution) they initially belonged to.

The between‐group analyses conducted on the second dimension – exploring the relationship between income changes and perceptions of tax evasion – revealed that individuals experiencing positive income changes become more perceptive of tax evasion. While the within‐individual effects appear overall insignificant, a more nuanced investigation into effect heterogeneity among different groups based on their initial income suggests that it is the lowest income group whose members typically increase their perceptions of tax evasion when experiencing an income increase. This aligns with the ‘othering’ logic, signifying an equally important psychological mechanism explaining perceptions of system abuse, albeit within more specific groups. This finding underscores the importance of initial income levels or starting points, highlighting how individuals gradually update their understanding of their group through their experiences (Helgason & Rehm, Reference Helgason and Rehm2023).

The discrepancy between identification among benefit recipients and ‘othering’ among those with income gains can be explained by the different attributions these groups make regarding their changing life situations. Those becoming dependent on welfare benefits tend to attribute their unfortunate circumstances, such as poverty or unemployment, to external factors rather than their individual actions (Furåker & Blomsterberg, Reference Furåker and Blomsterberg2003; Kallio & Niemelä, Reference Kallio and Niemelä2014). In this sense, benefit recipients may feel that they and similar others ended up in their precarious situation because of collective causes, thereby fostering a stronger sense of group belonging. Such a predisposition then consolidates in weakened perceptions that benefit abuse takes place in the system. In contrast, those who gain income often attribute this improvement to individualistic achievements and their own hard work, aligning closely with a meritocratic worldview (Mijs, Reference Mijs2019). Particularly among low‐income groups, the shift in their opinions regarding tax evasion when experiencing an income increase might reflect a narrative often perpetuated by populist parties. This narrative pits hard‐working individuals, deemed deserving due to their contributions, against others perceived as not contributing enough to the system and gaining income advantage thanks to their fraudulent behaviour (De Koster et al., Reference de Koster, Achterberg and Van der Waal2013; Kochuyt et al., Reference Kochuyt, Abts and Roosma2023).

All in all, this paper highlights the significance of formative personal experiences as an explanatory framework for understanding perceptions crucial to the legitimacy of the social and political system. While the most consistent evidence points to changes in perceptions regarding the group one starts to belong to, there is also evidence that the formative personal experiences can influence opinions beyond one's own immediate group. This suggests that apart from the influence of political narratives and general socializations, citizens can revise their views or knowledge when encountering relevant idiosyncratic experiences throughout their life course. Future research should explore and test this proposed explanatory framework in relation to other political attitudes.

The analysis was conducted in Norway, providing a suitable context for a relatively stringent test of the hypotheses. Norway's encompassing, universal welfare state and a prevalent ‘culture of trust’ might somewhat attenuate the effect of formative personal experiences compared to other contexts. However, it is important to note that both identification and ‘othering’ processes still occurred. Despite the higher trust level in recipients and contributors in Norway compared to many other countries, the absolute levels of perceptions of abuse are still substantial. These contextual characteristics could partially explain our results, emphasizing the need for future research to replicate these findings in diverse national contexts.

Beyond analysing a single country, the nature of our survey data presents an empirical constraint. While formative personal experiences undoubtedly encompass psychological, social, economic and administrative facets, our panel survey measurements are not refined enough to allow for a deeper exploration to untangle these processes. However, now that we have recognized these personal experiences as integral in shaping people's perceptions of benefit abuse, future research should aim to unravel their complex internal mechanisms more effectively. Moreover, our measurement of income changes was imperfect, merely indicating changes across income brackets instead of specific income changes. Therefore, future research should delve deeper into the role of income changes using more precise measurements. Despite these limitations, this research provides a relevant test of the role of formative experience, laying a foundation for further studies to build upon.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the WELTRUST project for their insightful comments on this paper. In addition, we are grateful to the participants of the ReNEW‐Nordic ESPAnet workshop at the University of Iceland for their constructive feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript. We also acknowledge funding from the Research Council of Norway for the WELTRUST project, reference number 301443. In addition, Arno Van Hootegem benefitted from funding from the Research Foundation Flanders and ReNEW network for a research stay in Oslo, during which this paper was first developed.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The data and are available upon request at https://doi.org/10.18712/NSD‐NSD2458‐V2. Replication materials for this article are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/91VA6O.

Ethics approval statement

We apply secondary data analysis on a survey that adheres to the ethical guidelines stipulated by the University of Oslo.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Online Appendix